Abstract

Introduction: Eravacycline is a new fluorocycline antibiotic with a broad spectrum of antimicrobial activity approved for the treatment of patients with complicated intra-abdominal infections. This systematic review aimed to evaluate the published data on the resistance of Gram-negative bacterial isolates to eravacycline. Methods: We identified relevant publications by systematically searching Embase, PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science from their inception to 29 August 2025. Published antimicrobial resistance breakpoints of the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) and the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) were used. Results: Data on 59,922 Gram-negative bacterial clinical isolates were retrieved from 68 articles after the screening of 283 potentially relevant studies. The resistance of consecutive (non-selected) Escherichia coli ranged from 0.9% to 9.6%. The MIC50 values of eravacycline were ≤0.5 mg/L for Acinetobacter baumannii isolates, including carbapenem-resistant A. baumannii, in the majority of studies. The proportions of resistance were higher among other lactose non-fermenting Gram-negative bacterial isolates, especially Pseudomonas aeruginosa, as well as among selected E. coli with advanced patterns of antimicrobial resistance. Conclusions: The evaluated data support the adequate antimicrobial activity of eravacycline against most Gram-negative bacterial clinical isolates. However, in vitro antimicrobial susceptibility testing and modern molecular diagnostic tests, including those that examine mechanisms of resistance, are helpful for the appropriate use of eravacycline in clinical practice.

1. Introduction

Tetracyclines are a group of antibiotics, more specifically protein synthesis inhibitors, that have been used in clinical practice for many decades. They act by inhibiting the 30S ribosomal subunit, thereby preventing aminoacyl-tRNA from binding to the acceptor site of the ribosomal complex on the mRNA [1]. Their antimicrobial spectrum is broad, and they have been used by clinicians to treat patients with various types of infections for decades.

Eravacycline, formerly TP-434, is a new synthetic fluorocycline that belongs to the expanded family of tetracycline-type antibiotics [2,3]. It was developed to combat the growing issue of bacterial resistance to tetracyclines. It has a structure similar to that of tigecycline, a glycylcycline antibiotic, with two modifications to its tetracycline core [4]. These modifications were made to bypass common bacterial resistance mechanisms, such as efflux pumps [5].

Its spectrum is broad, covering several Gram-negative, Gram-positive, and anaerobic bacteria, as well as some atypical bacteria [2]. It has shown effectiveness against several species of Enterobacterales and lactose non-fermenting Gram-negative bacteria. Pseudomonas aeruginosa is an exception, as it has demonstrated high resistance to this drug [3]. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved it for use in 2018 for the treatment of complicated intra-abdominal infections (cIAI) in adult patients [4,5]. As the nature of these infections is commonly polymicrobial and caused by Gram-negative aerobic bacteria, Gram-positive aerobic bacteria, and anaerobic bacteria, eravacycline is a promising therapeutic option, including other types of infections, particularly those caused by multiresistant bacteria [6].

In this context, we sought to gather available data on the resistance of Gram-negative bacteria to this antimicrobial agent to evaluate its effectiveness against these pathogens. Our article aims to help clinicians understand how they can effectively incorporate this drug into their practice.

2. Methods

2.1. Sources and Eligibility Criteria

This systematic review was performed in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. The study protocol was not uploaded to a registry. We performed an extensive literature review across four databases, specifically Embase, PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science, from their inception to 29 August 2025. Eligible for assessment were studies of any primary research design that met the following inclusion criteria: (a) the terms “eravacycline” or “TP-434” included in the title/abstract/keywords, and (b) the study reported minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) or disk diffusion zone diameters susceptibility data.

The exclusion criteria were (in the order they were applied): (a) non-primary research articles; (b) articles using isolates from animal sources; (c) case reports of a single isolate or patient; (d) primary research articles that did not contain relevant data for this review; (e) conference abstracts; (f) studies evaluating <10 total isolates, for the eravacycline susceptibility testing, and (g) studies that used only disk diffusion method for in vitro susceptibility testing without use of the broth microdilution method.

2.2. Search Strategy

The detailed search strategy is presented in Supplementary File S1. Terms such as “eravacycline”, “resistance”, “non-susceptibility”, “Enterobacteriaceae”, “Enterobacterales”, “Pseudomonas”, “Acinetobacter”, “Stenotrophomonas”, “MIC”, and “disk diffusion” were used.

2.3. Screening of Studies

Using the Rayyan tool’s deduplication feature, we deduplicated studies across different databases using their digital object identifiers (DOIs). Two independent reviewers (L.T.R. and D.S.K.) screened all the retrieved records using the full text.

2.4. Breakpoints of Susceptibility Testing

At the time of this writing, only limited susceptibility breakpoints had been reported by the relevant committees. For Gram-negative bacteria, the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) has published the breakpoints for Escherichia coli specifically (susceptible at MIC ≤ 0.5 mg/L). While the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) has not yet established breakpoints for this antibiotic, the FDA has set the breakpoint of susceptibility for all Enterobacterales at MIC ≤ 0.5 mg/L.

2.5. Data Extraction and Tabulation

The data were grouped by bacterial species (Enterobacterales vs. lactose non-fermenting Gram-negative bacteria). Additionally, we separated the data into consecutive (non-selected) and non-consecutive (selected) isolates, as reported by the study authors. We included data on the total number of isolates studied, the number of isolates of specific species, and the presence of various β-lactamase genes (determined by phenotypic and/or genotypic methods). We also included data on the MIC range, MIC50, MIC90, and the percentage of resistant isolates. Whenever percentages were provided as the only measure of eravacycline resistance in a study, we calculated the corresponding number of resistant isolates based on the total number of isolates and the given percentage and vice versa. Any disagreements between reviewers were resolved by consensus with a senior author (M.E.F.)

3. Results

3.1. Selection of Relevant Articles

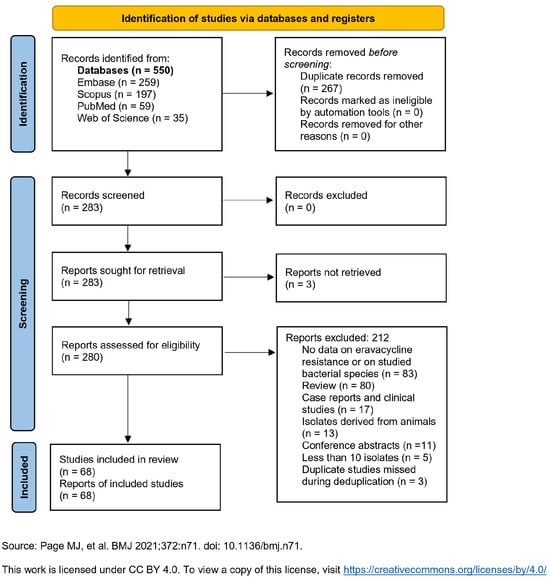

Figure 1 presents the “Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses” (PRISMA) flow diagram for evaluating, selecting, and including relevant articles. In total, 550 articles were identified and, after deduplication, 283 were screened. A full-text evaluation was conducted for all 283 articles; after excluding 212, 68 were eligible for inclusion (3 articles could not be retrieved) [7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74].

Figure 1.

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for new systematic reviews which included searches of databases and registers only [75].

3.2. Main Findings

The evaluated studies included data on 59,922 clinical isolates and were categorized into four groups: studies assessing resistance among (a) consecutive (non-selected) Enterobacterales isolates, (b) selected Enterobacterales isolates, (c) consecutive (non-selected) lactose non-fermenting Gram-negative isolates, and (d) selected lactose non-fermenting Gram-negative isolates.

3.3. Resistance of Consecutive Enterobacterales Clinical Isolates to Eravacycline

Table 1 presents data on consecutive (non-selected) Enterobacterales isolates [7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14]. Breakpoints definitions of resistance used by authors varied, with some using EUCAST breakpoints, some FDA breakpoints, and some defining their own breakpoints, based, for example, on the epidemiological cut-off values (ECOFF). Resistance percentages were 0.9% and 9.6% in the two studies that used breakpoints defined by EUCAST [9,11]. These figures involved E. coli isolates, as EUCAST breakpoints are only applicable for this species. The isolates in the three studies, which used FDA breakpoints, showed resistance of Enterobacterales to eravacycline ranging from 0.9% to 41.9% [9,10,11]. Specifically, among E. coli isolates, the resistance percentages were 0.9% and 9.6% in the two studies with relevant data, as EUCAST and FDA have adopted the same resistance breakpoint for E. coli [9,11]. In all five studies that presented specific relevant data for cumulatively 4671 E. coli isolates, the eravacycline MIC90 was 0.5 mg/L [9,11,12,13,14].

Table 1.

Resistance of consecutive (non-selected) clinical isolates of Enterobacterales to eravacycline.

Among Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates, resistance was 10% and 41.9% in the two studies with relevant data [9,11]. Among six studies that presented specific, applicable data and included a cumulative total of 2133 K. pneumoniae isolates, the MIC90 of eravacycline was 0.5 mg/L in one study [11] and >0.5 mg/L in the remaining five studies [7,9,12,13,14]. The MIC50 was ≤0.5 mg/L in all six studies.

The resistance of Enterobacter cloacae was 18.3% [11]. The MIC90 of eravacycline was >0.5 mg/L in all three studies that reported specific, relevant data, totaling 569 E. cloacae complex isolates [11,12,14]. The MIC50 was 0.5 mg/L in all three studies.

Additionally, in one study, Enterobacterales showed 16.7% resistance when the MIC > 0.5 resistance breakpoint was used, as defined by the authors [8]. In another study, the resistance to eravacycline of all the Enterobacterales species isolates evaluated was 14.3% [10]. The MIC90 was 1 mg/L in both studies, which included a total of 1424 isolates [8,10].

3.4. Resistance of Selected Enterobacterales Clinical Isolates to Eravacycline

Table 2 presents data on selected Enterobacterales isolates [15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47]. Breakpoint variability was also present in these studies, as previously mentioned. Resistance to eravacycline was 0% and 37.5% among E. coli isolates in the four studies that used the EUCAST breakpoints [15,16,18,20,28,29,31,33,35,39,40,43]. The authors of three other studies applied the EUCAST breakpoints for E. coli to the total number of Enterobacterales isolates. In these three studies, resistance ranged from 0% to 94.1% [20,28,43]. In studies that utilized the FDA breakpoints, resistance of Enterobacterales ranged from 0% to 100% [15,16,17,18,19,22,23,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,46,47]. Specifically, in E. coli isolates, resistance to eravacycline ranged from 0% to 29% [15,16,17,18,20,26,28,31,33,35,37,38,39,40,42,43,46]. In K. pneumoniae, resistance ranged from 0% to 100% [15,17,18,20,26,28,31,33,35,36,37,38,40,42,43,46]. In E. cloacae/E. cloacae complex, resistance ranged from 10.5% to 55.6% [18,20,26,28,31,33,40]. In one study in which the authors used MIC ≥ 1 mg/L as the breakpoint for resistance, 23.7% of the total Enterobacterales isolates were resistant. In another study, no resistant isolates were found when the authors used a MIC > 2 mg/L breakpoint for resistance.

Table 2.

Resistance of selected clinical isolates of Enterobacterales to eravacycline.

3.5. Resistance of Consecutive Lactose Non-Fermenting Gram-Negative Bacterial Clinical Isolates to Eravacycline

Table 3 presents data on consecutive lactose non-fermenting isolates [8,9,11,12,13,14,15,28,43,46,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58]. As there are no available resistance breakpoints for these bacteria, resistance data are reported according to the breakpoints defined by the authors of each article. In one article, where the authors used a resistance breakpoint of MIC > 0.25 mg/L, Acinetobacter baumannii isolates showed 43.4% resistance. In the same article, the authors also used a MIC breakpoint of >0.5 mg/L for the same isolates, and the resistance was 28.3% [8]. In another study, authors used the breakpoints for Enterobacterales as defined by EUCAST (MIC > 0.5 mg/L), and 38.6% of isolates were resistant to eravacycline [52].

Table 3.

Resistance of consecutive (non-selected) clinical isolates of lactose non-fermenting Gram-negative bacteria to eravacycline.

3.6. Resistance of Selected Lactose Non-Fermenting Gram-Negative Bacterial Clinical Isolates to Eravacycline

Table 4 presents data on selected lactose non-fermenting isolates [18,24,26,35,38,44,59,60,61,62,63,64,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,77]. Resistance breakpoints for these isolates were also defined by some authors. In one study, in which the authors used resistance breakpoints of MIC ≥ 8 mg/L, the resistance was 1.9% [59]. In another study, carbapenem-resistant A. baumannii isolates (CRAB) and carbapenem-susceptible A. baumannii (CSAB) isolates had resistance percentages of 2.4% and 1.3%, respectively, when the breakpoint for resistance was MIC > 4 mg/L [61]. In one study, a MIC breakpoint of >4 mg/L was used, and A. baumannii isolates showed 52.4% resistance [62]. One author used an intermediate resistance breakpoint of MIC 4 mg/L and a resistance breakpoint of MIC ≥ 8 mg/L. Intermediate resistance percentages for both CRAB and CSAB isolates were 1.4%, while resistance percentages were 2% and 0.7%, respectively [63]. In three studies in which the great majority, if not all, of the isolates were carbapenem-resistant, the authors used breakpoints from EUCAST or FDA, or those defined by other authors, which deemed all isolates with MIC > 0.5 mg/L as resistant. The resistance percentages for these studies were 8.9%, 24.1%, and 80.9% [26,38,64].

Table 4.

Resistance of selected clinical isolates of lactose non-fermenting Gram-negative bacteria to eravacycline.

3.7. Eravacycline MIC Distribution for Clinically Important Gram-Negative Bacteria

Among 21 studies that included specific relevant data (Table 1 and Table 2), the MIC90 of E. coli isolates to eravacycline was 0.5 mg/L or less in 16 studies [9,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,28,31,37,39,42,43,46], which included, cumulatively, 10,116 isolates. The MIC90 was 1 mg/L in four studies with cumulatively 376 selected isolates [20,35,38,40], and more than 1 mg/L in a single study with eight E. coli isolates [33]. The MIC50 was less than or equal to 0.5 mg/L in all 21 studies. More specifically, the MIC50 was 0.12 mg/L in two studies [12,13], 0.25 mg/L in five studies [9,13,14,35,40], and 0.5 mg/L in three studies (all with selected isolates) [20,33,38].

Among 29 studies that provided data for K. pneumoniae or Klebsiella spp. isolates, the MIC90 of eravacycline was 0.5 mg/L in four studies [11,30,34,43] with cumulatively 5430 isolates. The MIC90 was above 0.5 mg/L in the remaining 25 studies, which included a total of 6773 isolates [7,9,12,13,14,15,17,18,19,20,21,23,24,25,28,29,31,33,35,36,38,39,40,41,46]. The MIC50 was lower than or equal to 0.5 mg/L in all except for nine studies. The latter nine studies included a total of 945 isolates [17,18,19,29,33,35,38,39,41].

Regarding Enterobacter cloacae complex, MIC50 and MIC90 data were provided in 10 studies, totaling 2746 isolates [11,12,14,18,20,28,30,31,33,40]. The MIC90 of eravacycline was 0.5 mg/L or lower in one of these studies [30]. The MIC50 was 0.5 mg/L or lower in all but two of these studies [18,31]; the latter included 96 isolates.

Regarding non-fermenting Gram-negative bacteria, specifically Acinetobacter baumannii complex, MIC50 and MIC90 data were provided in 26 studies with, cumulatively, 8744 isolates [9,11,12,13,14,15,18,24,28,35,43,46,48,49,52,55,56,59,60,62,64,66,67,70,73,74]. The MIC90 was 0.5 mg/L in four studies [11,13,15,66], which included a total of 682 isolates. The MIC50 was 0.5 mg/L or lower in 21 of these studies [9,11,12,13,14,15,18,24,28,43,46,49,52,59,60,64,66,73,74], which included a total of 7832 isolates.

Seventeen studies reported MIC distributions for CRAB or carbapenemase-producing A. baumannii complex isolates [8,24,26,46,55,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,66,68,73,74]. These studies included 3231 isolates in total. The MIC90 was 0.5 mg/L or less in two studies [58,66], with 239 isolates. The MIC50 was 0.5 mg/L or less in 10 studies with 2378 isolates [24,46,58,59,60,61,63,66,73,74].

4. Discussion

4.1. Interpretation of Results

The data analyzed show that the resistance of Enterobacterales isolates to eravacycline varies by species. The drug appears to be effective against E. coli isolates (with resistance that ranged from 0.9% to 9.6% among consecutive isolates and from 0% to 29% among selected isolates). However, higher proportions of resistance to eravacycline are noted among isolates of other Enterobacterales species, specifically K. pneumoniae and E. cloacae complex. Additionally, the proportion of resistance to eravacycline among Morganellaceae, including Proteus, Morganella, and Providencia isolates, is very high. Although there are no specific data on the possible intrinsic resistance of these isolates to eravacycline, it is known that Morganellaceae exhibit intrinsic resistance to tetracyclines.

Considerable variability in resistance to the drug was observed among lactose non-fermenting Gram-negative bacterial isolates. This could be partially attributed to the fact that authors used different MIC resistance breakpoints, given the absence of published resistance breakpoints from the relevant organizations, resulting in non-uniform results. However, a meticulous evaluation of the data included in our tables reveals that the MIC90 values of eravacycline are rather low for A. baumannii complex isolates (i.e., not higher than 1 mg/L), including CRAB, in the majority of studies. The MIC90 values for eravacycline are also low for Burkholderia cepacia complex and Stenotrophomonas maltophilia isolates, although the published relevant information is limited. The data suggest that the MIC90 values for eravacycline in P. aeruginosa isolates are, as for other members or derivatives of the tetracycline class of antibiotics, higher than those for other lactose non-fermenting Gram-negative bacteria, especially A. baumannii isolates.

Previous studies have evaluated the use of tetracyclines and various tetracycline derivatives against A. baumannii [79]. It has been demonstrated that tetracyclines, often in combination with other antibiotics, exhibit promising effectiveness, particularly with minocycline and tigecycline [80,81]. In a systematic review of relevant published data, doxycycline or minocycline therapy was shown to be effective. In fact, it achieved clinical success in 77% of 156 patients with A. baumannii infections, including those involving the respiratory tract and bloodstream [82]. Additionally, TP-6076, another fluorocycline (like eravacycline), exhibited lower MIC values than tetracyclines and showed overall good antimicrobial activity against A. baumannii isolates. Specifically, the MIC50 and MIC90 values of TP-6076 for the studied 121 non-duplicate A. baumannii isolates were 0.03 mg/L and 0.06 mg/L, respectively [83].

Our evaluation of published data on resistance to eravacycline among Gram-negative bacterial isolates, including Enterobacterales and lactose non-fermenting isolates, suggests that in vitro antimicrobial susceptibility testing may help clinicians decide whether to initiate empirical therapy or continue targeted therapy with this drug. Additionally, the conduct of modern molecular microbiological diagnostic testing to detect resistance mechanisms can help clinicians make informed decisions.

4.2. Relevant Clinical Trial Data

Several Phase 3 clinical trials have been conducted to determine the effectiveness of eravacycline for the treatment of cIAIs and other infections. Three studies originate from China (ChiCTR2300078646, ChiCTR1900022060, ChiCTR2200055666) [84,85,86]. One clinical trial assessed the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of eravacycline versus ertapenem for the treatment of cIAI in hospitalized adults. Another study investigated the efficacy and safety of eravacycline for cIAI in ICU patients. A third study aimed to assess the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of eravacycline compared with moxifloxacin for the treatment of community-acquired bacterial pneumonia in adult patients. Neither of these studies have released results yet. Four other Phase 3 clinical trials were conducted by Tetraphase Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Two studies (NCT01844856, NCT02784704) evaluated the efficacy and safety of eravacycline in cIAIs compared to ertapenem and meropenem, respectively [87,88]. Two other studies (NCT01978938, NCT03032510) evaluated the efficacy and safety of eravacycline in complicated UTIs compared to levofloxacin and ertapenem, respectively [89,90]. The results of these studies highlighted its success in treating cIAIs relative to its comparators and its lack of success in treating cUTIs. As a result, it was approved for the sole indication of cIAIs.

An interventional, Phase 2 clinical study (NCT05537896) is currently underway to determine whether this antimicrobial agent can be used as a prophylactic treatment for patients with hematological malignancies who experience prolonged neutropenia [91]. As eravacycline has broad-spectrum activity but is not used for febrile neutropenia, it may be a good candidate for studies on prophylactic use in this patient population. Patients in this study will receive 1–1.5 mg/kg via 60 min intravenous infusion every 12 h. This treatment shall be continued until neutrophil recovery, febrile neutropenia, breakthrough infection, any grade 3–4 toxicity related to the medication, or completion of 21 days of therapy. As this study is still in the recruitment stage, no results have been published yet.

Concurrently, another Phase 2 clinical trial (NCT06794541) is evaluating the safety and tolerability of eravacycline in pediatric patients, specifically those aged 8 to 17 years with cIAI [92]. This Multicenter, Open-label trial has three patient cohorts. In one cohort (cohort 1), 1.5 mg/kg of the intravenous formulation of eravacycline will be administered as a single 60 min IV infusion to participants aged 12 to <18 years. In the second cohort (cohort 2a) and the third cohort (cohort 2b), 2 mg/kg will be administered in the same way for participants aged 10 to <12 years and 8 to <10 years, respectively. This study is currently in the recruitment stage, and therefore, no results are available yet.

4.3. Eravacycline Resistance Mechanisms

Eravacycline is not affected by classic tetracycline-specific efflux pumps including those encoded by the tet(A) and tet(B) genes. Also, its activity is not substantially affected by the ribosomal proteins such as those encoded by the tet(M) and tet(O) genes, that de-crease the binding of tetracyclines to the ribosomal target site. However, eravacycline resistance can occur by overexpression of other efflux pumps. Acinetobacter spp. and Enterobacterales produce the AdeABC and AcrAB-TolC pumps, respectively. Overexpression of such pumps can result in a rapid expulsion of the antibiotic from the bacterial cell [93]. Another resistance mechanism involves the enzymatic inactivation of eravacycline by the Tet(X) family of enzymes. These enzymes, especially Tet(X4), degrade eravacycline, rendering it ineffective. Bacteria can acquire genes encoding these enzymes via plasmids [94]. Resistance can also arise from other mutations which alter the target of eravacycline. For instance, mutations in 16S rRNA or other ribosomal proteins can alter the antibiotic’s binding site, thereby reducing its activity [95].

Additional research reveals that resistance mechanisms, often centered around mutations in key regulatory proteins, subsequently amplified the efflux activity, especially in carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae isolates. Specifically, in K. pneumoniae, resistance frequently develops due to mutations of the gene that encodes the Lon protease. These mutations reduce the functional expression or activity of the Lon protease, thereby increasing the level of the regulator RamA. This leads to the upregulation of the multidrug efflux system AcrA-AcrB-TolC and thereby reduces the intracellular accumulation of eravacycline. Additionally, eravacycline resistance in such isolates has also been associated with over-expression of OqxAB and MacAB efflux pumps. A frameshift mutation has also been identified in the DEAD/DEAH box helicase gene on a plasmid of an evolved resistant K. pneumoniae strain, which suggests that there can also be acquired resistance through altered ribosomal or RNA processing pathways [96]

4.4. Limitations

Our study is not without potential limitations. First, no universally accepted resistance breakpoints were available; therefore, many authors may have foregone reporting resistance percentages among the studied isolates and instead presented MIC ranges, MIC50, and MIC90. This casts some difficulty with the practical use of the evaluated data. However, the meticulous evaluation of published data on the resistance of various Gram-negative bacterial isolates to eravacycline that we present herein could help future researchers and clinicians appropriately use the antibiotic. Additionally, there is no universally accepted and validated risk-of-bias assessment tool for in vitro antimicrobial susceptibility studies; therefore, we did not use such a tool in our article. Finally, we had not registered the protocol of our study in a publicly available depository.

5. Conclusions

Eravacycline is a newer, fluorocycline-class antibiotic, approved for the treatment of patients with complicated intra-abdominal infections. The evaluation of the published evidence in our study suggests that this agent exhibits broad-spectrum antibacterial activity against most clinically important Gram-negative bacteria. It displayed high activity against E. coli isolates. However, notable levels of resistance were observed against K. pneumoniae and E. cloacae isolates. Lactose non-fermenting Gram-negative bacteria also had variable resistance against this drug. This could be attributed to the variability of the breakpoints used by the authors of the included studies, given the lack of established breakpoints of resistance. The aforementioned proportion of resistance, especially among selected Gram-negative bacterial isolates with advanced antimicrobial resistance patterns, suggests that in vitro antimicrobial susceptibility testing and modern molecular diagnostic tests for resistance mechanisms may aid optimal utilization of eravacycline in clinical practice.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/pathogens14121214/s1, Supplementary File S1: Detailed search strategies used in each resource as of 29 August 2025; Supplementary File S2: PRISMA 2020 abstract checklist [75]. Supplementary File S3: PRISMA 2020 checklist [75].

Author Contributions

M.E.F. had the idea for the article. All authors (M.E.F., L.T.R., D.S.K., C.F., and D.E.K.) contributed to the methodology used in the article. L.T.R. and D.S.K. did the literature search, data extraction, and tabulation. M.E.F., L.T.R., and D.S.K. contributed to the first version of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| A. baumannii | Acinetobacter baumannii |

| cIAI | complicated intra-abdominal infections |

| CLSI | Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute |

| CRAB | carbapenem-resistant A. baumannii isolates |

| CSAB | carbapenem-susceptible A. baumannii |

| DOIs | digital object identifiers |

| E. cloacae | Enterobacter cloacae |

| E. coli | Escherichia coli |

| EMA | European Medicines Agency |

| EUCAST | European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| K. pneumoniae | Klebsiella pneumoniae |

| MIC | minimum inhibitory concentration |

| P. aeruginosa | Pseudomonas aeruginosa |

References

- Shutter, M.C.; Akhondi, H. Tetracycline. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Zhanel, G.G.; Cheung, D.; Adam, H.; Zelenitsky, S.; Golden, A.; Schweizer, F.; Gorityala, B.; Lagacé-Wiens, P.R.S.; Walkty, A.; Gin, A.S.; et al. Review of Eravacycline, a Novel Fluorocycline Antibacterial Agent. Drugs 2016, 76, 567–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, R.; Guan, X.; Sun, L.; Fei, Z.; Li, Y.; Luo, M.; Ma, A.; Li, H. The Efficacy and Safety of Eravacycline Compared with Current Clinically Common Antibiotics in the Treatment of Adults with Complicated Intra-Abdominal Infections: A Bayesian Network Meta-Analysis. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 935343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. XERAVA (Eravacycline) for Injection: Prescribing Information; U.S. Food and Drug Administration: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2018. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2018/211109lbl.pdf (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- European Medicines Agency. Xerava (Eravacycline): EPAR Product Information (English); European Medicines Agency: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/xerava-epar-product-information_en.pdf (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Dupont, H. The Empiric Treatment of Nosocomial Intra-Abdominal Infections. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2007, 11, S1–S6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianco, G.; Boattini, M.; Lupo, L.; Ambretti, S.; Greco, R.; Degl’Innocenti, L.; Chiatamone Ranieri, S.; Fasciana, T.; Mazzariol, A.; Gibellini, D.; et al. In Vitro Activity and Genomic Characterization of KPC-Producing Klebsiella pneumoniae Clinical Blood Culture Isolates Resistant to Ceftazidime/Avibactam, Meropenem/Vaborbactam, Imipenem/Relebactam: An Italian Nationwide Multicentre Observational Study (2022–23). J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2025, 80, 583–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinet-Poleur, A.; Bogaerts, P.; Montesinos, I.; Huang, T.-D. Eravacycline: Evaluation of Susceptibility Testing Methods and Activity against Multidrug-Resistant Enterobacterales and Acinetobacter. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2025, 44, 2771–2778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, X.; Liang, Q.; Dai, X.; Wu, S.; Duan, C.; Luo, Z.; Xie, X. In Vitro Activities of Eravacycline against Clinical Bacterial Isolates: A Multicenter Study in Guangdong, China. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1504013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Liu, Y.; Jia, W.; Xu, X.; Sun, G.; Wang, T.; Li, J.; Zhang, G.; Jing, R.; Sun, H.; et al. In Vitro Activities of Aztreonam-Avibactam, Eravacycline, Cefoselis, and Other Comparators against Clinical Enterobacterales Isolates: A Multicenter Study in China, 2019. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e04873-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhanel, G.G.; Baxter, M.R.; Adam, H.J.; Sutcliffe, J.; Karlowsky, J.A. In Vitro Activity of Eravacycline against 2213 Gram-Negative and 2424 Gram-Positive Bacterial Pathogens Isolated in Canadian Hospital Laboratories: CANWARD Surveillance Study 2014–2015. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2018, 91, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdallah, M.; Olafisoye, O.; Cortes, C.; Urban, C.; Landman, D.; Quale, J. Activity of Eravacycline against Enterobacteriaceae and Acinetobacter baumannii, Including Multidrug-Resistant Isolates, from New York City. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015, 59, 1802–1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomkin, J.S.; Ramesh, M.K.; Cesnauskas, G.; Novikovs, N.; Stefanova, P.; Sutcliffe, J.A.; Walpole, S.M.; Horn, P.T. Phase 2, Randomized, Double-Blind Study of the Efficacy and Safety of Two Dose Regimens of Eravacycline versus Ertapenem for Adult Community-Acquired Complicated Intra-Abdominal Infections. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014, 58, 1847–1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutcliffe, J.A.; O’Brien, W.; Fyfe, C.; Grossman, T.H. Antibacterial Activity of Eravacycline (TP-434), a Novel Fluorocycline, against Hospital and Community Pathogens. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2013, 57, 5548–5558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, X.; Mak, W.Y.; Xue, F.; Yang, W.; Kuan, I.H.-S.; Xiang, X.; Li, Y.; Zhu, X. Population Pharmacokinetics and Pulmonary Modeling of Eravacycline and the Determination of Microbiological Breakpoint and Cutoff of PK/PD. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2025, 69, e01065-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Terrier, C.; Nordmann, P.; Delaval, A.; Poirel, L.; Lienhard, R.; Vonallmen, L.; Schilt, C.; Scherler, A.; Lucke, K.; Jutzi, M.; et al. Potent in Vitro Activity of Sulbactam-Durlobactam against NDM-Producing Escherichia Coli Including Cefiderocol and Aztreonam-Avibactam-Resistant Isolates. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2025, 31, 122–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-L.; Liu, C.-E.; Wang, W.-Y.; Tan, M.-C.; Chen, P.-J.; Shiau, Y.-R.; Wang, H.-Y.; Lai, J.-F.; Huang, I.-W.; Yang, Y.-S.; et al. Antimicrobial Resistance among Imipenem-Non-Susceptible Escherichia Coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae Isolates, with an Emphasis on Novel β-Lactam/β-Lactamase Inhibitor Combinations and Tetracycline Derivatives: The Taiwan Surveillance of Antimicrobial Resistance Program, 2020–2022. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2025, 58, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, P.; Guijarro-Sánchez, P.; Lasarte-Monterrubio, C.; Muras, A.; Alonso-García, I.; Outeda-García, M.; Maceiras, R.; Fernández-López, M.D.C.; Rodríguez-Coello, A.; García-Pose, A.; et al. Activity and Resistance Mechanisms of the Third Generation Tetracyclines Tigecycline, Eravacycline and Omadacycline against Nationwide Spanish Collections of Carbapenemase-Producing Enterobacterales and Acinetobacter baumannii. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 181, 117666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Xiong, Y.; Wang, M.; Wang, J.; Song, T.; Yu, J.; Hu, J.; Zhao, Z.; Li, M.; Li, Y.; et al. Small RNA-Regulated Expression of Efflux Pump Affects Tigecycline Resistance and Heteroresistance in Clinical Isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Microbiol. Res. 2024, 287, 127825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.-F.; Wang, J.-T.; Chuang, Y.-C.; Sheng, W.-H.; Chen, Y.-C. In Vitro Susceptibility of Common Enterobacterales to Eravacycline in Taiwan. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2023, 56, 358–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markovska, R.; Stankova, P.; Stoeva, T.; Keuleyan, E.; Mihova, K.; Boyanova, L. In Vitro Antimicrobial Activity of Five Newly Approved Antibiotics against Carbapenemase-Producing Enterobacteria—A Pilot Study in Bulgaria. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markovska, R.; Stankova, P.; Popivanov, G.; Gergova, I.; Mihova, K.; Mutafchiyski, V.; Boyanova, L. Emergence of blaNDM-5 and blaOXA-232 Positive Colistin- and Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in a Bulgarian Hospital. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Słabisz, N.; Leśnik, P.; Janc, J.; Fidut, M.; Bartoszewicz, M.; Dudek-Wicher, R.; Nawrot, U. Evaluation of the in Vitro Susceptibility of Clinical Isolates of NDM-Producing Klebsiella pneumoniae to New Antibiotics Included in a Treatment Regimen for Infections. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1331628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Chen, J.; Zhang, G.; Li, J.; Wang, T.; Kang, W.; Zhang, J.; Sun, H.; Liu, Y.; Xu, Y. In-Vitro Activities of Essential Antimicrobial Agents Including Aztreonam/Avibactam, Eravacycline, Colistin and Other Comparators against Carbapenem-Resistant Bacteria with Different Carbapenemase Genes: A Multi-Centre Study in China, 2021. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2024, 64, 107341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Yu, W.; Chu, X.; Zhang, J.; Jia, P.; Liu, X.; Zhu, Y.; Xu, Y.; Yang, Q. Effect of Ceftazidime-Avibactam Combined with Different Antimicrobials against Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. Microbiol. Spectr. 2024, 12, e00107-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, D.; Liu, Y.; Li, Q.; Liu, H.; Zhou, P.; Liu, Y.; Chen, L.; Yin, W.; Lu, Y. Detection and Characterization of Eravacycline Heteroresistance in Clinical Bacterial Isolates. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1332458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnin, R.A.; Bernabeu, S.; Emeraud, C.; Naas, T.; Girlich, D.; Jousset, A.B.; Dortet, L. In Vitro Activity of Imipenem-Relebactam, Meropenem-Vaborbactam, Ceftazidime-Avibactam and Comparators on Carbapenem-Resistant Non-Carbapenemase-Producing Enterobacterales. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawser, S.; Kothari, N.; Monti, F.; Morrissey, I.; Siegert, S.; Hodges, T. In Vitro Activity of Eravacycline and Comparators against Gram-Negative and Gram-Positive Bacterial Isolates Collected from Patients Globally between 2017 and 2020. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2023, 33, 304–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.-S.; Yang, J.-L.; Wang, J.-T.; Sheng, W.-H.; Yang, C.-J.; Chuang, Y.-C.; Chang, S.-C. Evaluation of the Synergistic Effect of Eravacycline and Tigecycline against Carbapenemase-Producing Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. J. Infect. Public Health 2024, 17, 929–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perez-Palacios, P.; Girlich, D.; Soraa, N.; Lamrani, A.; Maoulainine, F.M.R.; Bennaoui, F.; Amri, H.; El Idrissi, N.S.; Bouskraoui, M.; Birer, A.; et al. Multidrug-Resistant Enterobacterales Responsible for Septicaemia in a Neonatal Intensive Care Unit in Morocco. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2023, 33, 208–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, X.; Jin, S.; Chen, L.; Li, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, H.; Li, X.; Huang, H. Antibacterial Activity of Eravacycline Against Carbapenem-Resistant Gram-Negative Isolates in China: An in Vitro Study. Infect. Drug Resist. 2023, 16, 2271–2279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badran, S.; Malek, M.M.; Ateya, R.M.; Afifi, A.H.; Magdy, M.M.; Elgharabawy, E.S. Susceptibility of Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacterales Isolates to New Antibiotics from a Tertiary Care Hospital, Egypt: A Matter of Hope. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2022, 16, 1852–1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jurić, I.; Bošnjak, Z.; Ćorić, M.; Lešin, J.; Mareković, I. In Vitro Susceptibility of Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacterales to Eravacycline—The First Report from Croatia. J. Chemother. 2022, 34, 67–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koreň, J.; Andrezál, M.; Drahovská, H.; Hubenáková, Z.; Liptáková, A.; Maliar, T. Next-Generation Sequencing of Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae Strains Isolated from Patients Hospitalized in the University Hospital Facilities. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Cui, L.; Xue, F.; Wang, Q.; Zheng, B. Synergism of Eravacycline Combined with Other Antimicrobial Agents against Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae and Acinetobacter baumannii. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2022, 30, 56–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maraki, S.; Mavromanolaki, V.E.; Magkafouraki, E.; Moraitis, P.; Stafylaki, D.; Kasimati, A.; Scoulica, E. Epidemiology and in Vitro Activity of Ceftazidime–Avibactam, Meropenem–Vaborbactam, Imipenem–Relebactam, Eravacycline, Plazomicin, and Comparators against Greek Carbapenemase-Producing Klebsiella pneumoniae Isolates. Infection 2022, 50, 467–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, B.D.; Thuras, P.; Porter, S.B.; Clabots, C.; Johnsona, J.R. Activity of Cefiderocol, Ceftazidime-Avibactam, and Eravacycline against Extended-Spectrum Cephalosporin-Resistant Escherichia Coli Clinical Isolates (2012–2017) in Relation to Phylogenetic Background, Sequence Type 131 Subclones, blaCTX-M Genotype, and Coresistance. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2021, 100, 115314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, S.-C.; Wang, Y.-C.; Tan, M.-C.; Huang, W.-C.; Shiau, Y.-R.; Wang, H.-Y.; Lai, J.-F.; Huang, I.-W.; Lauderdale, T.-L. In Vitro Activity of Imipenem/Relebactam, Meropenem/Vaborbactam, Ceftazidime/Avibactam, Cefepime/Zidebactam and Other Novel Antibiotics against Imipenem-Non-Susceptible Gram-Negative Bacilli from Taiwan. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2021, 76, 2071–2078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-L.; Ko, W.-C.; Lee, W.-S.; Lu, P.-L.; Chen, Y.-H.; Cheng, S.-H.; Lu, M.-C.; Lin, C.-Y.; Wu, T.-S.; Yen, M.-Y.; et al. In-Vitro Activity of Cefiderocol, Cefepime/Zidebactam, Cefepime/Enmetazobactam, Omadacycline, Eravacycline and Other Comparative Agents against Carbapenem-Nonsusceptible Enterobacterales: Results from the Surveillance of Multicenter Antimicrobial Resistance in Taiwan (SMART) in 2017–2020. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2021, 58, 106377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalacain, M.; Lozano, C.; Llanos, A.; Sprynski, N.; Valmont, T.; Leiris, S.; Sable, C.; Ledoux, A.; Morrissey, I.; Lemonnier, M.; et al. Novel Specific Metallo-b-Lactamase Inhibitor ANT2681 Restores Meropenem Activity to Clinically Effective Levels against NDM—Positive Enterobacterales. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2021, 65, e00203-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, J.A.; Kulengowski, B.; Burgess, D.S. In Vitro Activity of Eravacycline Compared with Tigecycline against Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2020, 56, 106178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnston, B.D.; Thuras, P.; Porter, S.B.; Anacker, M.; VonBank, B.; Snippes Vagnone, P.; Witwer, M.; Castanheira, M.; Johnson, J.R. Activity of Cefiderocol, Ceftazidime-Avibactam, and Eravacycline against Carbapenem-Resistant Escherichia Coli Isolates from the United States and International Sites in Relation to Clonal Background, Resistance Genes, Coresistance, and Region. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2020, 64, e00797-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrissey, I.; Olesky, M.; Hawser, S.; Lob, S.H.; Karlowsky, J.A.; Corey, G.R.; Bassetti, M.; Fyfe, C. In Vitro Activity of Eravacycline against Gram-Negative Bacilli Isolated in Clinical Laboratories Worldwide from 2013 to 2017. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2020, 64, e01699-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, R.; Wang, Q.; Li, H.; Wang, H. In Vitro Activities of Eravacycline against 336 Isolates Collected from 2012 to 2016 from 11 Teaching Hospitals in China. BMC Infect. Dis. 2019, 19, 508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.R.; Porter, S.B.; Johnston, B.D.; Thuras, P. Activity of Eravacycline against Escherichia Coli Clinical Isolates Collected from U.S. Veterans in 2011 in Relation to Coresistance Phenotype and Sequence Type 131 Genotype. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2016, 60, 1888–1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livermore, D.M.; Mushtaq, S.; Warner, M.; Woodford, N. In Vitro Activity of Eravacycline against Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae and Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2016, 60, 3840–3844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Lin, X.; Bush, K. In Vitro Susceptibility of β-Lactamase-Producing Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) to Eravacycline. J. Antibiot. 2016, 69, 600–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ataman, M.; Çelik, B.Ö. Investigation of the in Vitro Antimicrobial Activity of Eravacycline Alone and in Combination with Various Antibiotics against MDR Acinetobacter Baumanni Strains. BMC Microbiol. 2025, 25, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buyukyanbolu, E.; Argotsinger, J.; Beck, E.T.; Chamberland, R.R.; Clark, A.E.; Daniels, A.R.; Liesman, R.; Fisher, M.; Gialanella, P.; Hand, J.; et al. Activity of Ampicillin-Sulbactam, Sulbactam-Durlobactam, and Comparators against Acinetobacter baumannii-calcoaceticus Complex Strains Isolated from Respiratory and Bloodstream Sources: Results from ACNBio Study. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2025, 69, e00379-25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, K.; Jia, H.; Gu, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Li, S.; Qu, Y.; Yang, Q. Species Distribution and Antimicrobial Susceptibility of Diverse Strains Within Burkholderia cepacia Complex. Microb. Drug Resist. 2025, 31, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mataracı-Kara, E.; Özer, B.; Yilmaz, M.; Özbek-Çelik, B. An Assessment of Cefiderocol’s Synergistic Effects with Eravacycline, Colistin, Meropenem, Levofloxacin, Ceftazidime/Avibactam, and Tobramycin against Carbapenem-Resistant and -Susceptible Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microb. Pathog. 2025, 204, 107560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, H.; Raza, S.; Biswas, J.; Mohapatra, S.; Sood, S.; Dhawan, B.; Kapil, A.; Das, B.K. Antimicrobial Efficacy of Eravacycline against Emerging Extensively Drug-Resistant (XDR) Acinetobacter baumannii Isolates. Indian J. Med. Microbiol. 2024, 48, 100565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, M.-H.; Chen, C.-L.; Chang, H.-J.; Chuang, T.-C.; Chiu, C.-H. Antimicrobial Activity of Eravacycline and Other Comparative Agents on Aerobic and Anaerobic Bacterial Pathogens in Taiwan: A Clinical Microbiological Study. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2024, 37, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunney, M.M.; Elborn, J.S.; McLaughlin, C.S.; Longshaw, C.M. In Vitro Activity of Cefiderocol against Gram-Negative Pathogens Isolated from People with Cystic Fibrosis and Bronchiectasis. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2024, 36, 407–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalacain, M.; Achard, P.; Llanos, A.; Morrissey, I.; Hawser, S.; Holden, K.; Toomey, E.; Davies, D.; Leiris, S.; Sable, C.; et al. Meropenem-ANT3310, a Unique β-Lactam-β-Lactamase Inhibitor Combination with Expanded Antibacterial Spectrum against Gram-Negative Pathogens Including Carbapenem-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2024, 68, e01120-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galani, I.; Papoutsaki, V.; Karaiskos, I.; Moustakas, N.; Galani, L.; Maraki, S.; Mavromanolaki, V.E.; Legga, O.; Fountoulis, K.; Platsouka, E.D.; et al. In Vitro Activities of Omadacycline, Eravacycline, Cefiderocol, Apramycin, and Comparator Antibiotics against Acinetobacter baumannii Causing Bloodstream Infections in Greece, 2020–2021: A Multicenter Study. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2023, 42, 843–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deolankar, M.S.; Carr, R.A.; Fliorent, R.; Roh, S.; Fraimow, H.; Carabetta, V.J. Evaluating the Efficacy of Eravacycline and Omadacycline against Extensively Drug-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii Patient Isolates. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.-T.; Chen, H.-Y.; Yang, Y.-S.; Chou, Y.-C.; Chang, T.-Y.; Hsu, W.-J.; Lin, I.-C.; Sun, J.-R. AdeABC Efflux Pump Controlled by AdeRS Two Component System Conferring Resistance to Tigecycline, Omadacycline and Eravacycline in Clinical Carbapenem Resistant Acinetobacter nosocomialis. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 584789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; Li, S.; Wang, X.; Lin, Y.; Jiang, H.; Li, N. Comparative Evaluation of Eravacycline Susceptibility Testing Methods in 587 Clinical Carbapenem-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii Isolates: Broth Microdilution, MIC Test Strip and Disc Diffusion. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2025, 80, 439–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Xu, N.; Wang, X. Activity of Cefiderocol in Combination with Tetracycline Analogues against Carbapenem-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. J. Antibiot. 2025, 78, 190–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Li, Y.; Lin, Y.; Guo, Y.; He, G.; Wang, X.; Wang, M.; Xu, J.; Song, M.; Tan, X.; et al. Comparison of Antimicrobial Activities and Resistance Mechanisms of Eravacycline and Tigecycline against Clinical Acinetobacter baumannii Isolates in China. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1417237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halim, J.; Carr, R.A.; Fliorent, R.; Jonnalagadda, K.; Kurbonnazarova, M.; Kaur, M.; Millstein, I.; Carabetta, V.J. Combinations of Antibiotics Effective against Extensively- and Pandrug-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii Patient Isolates. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chen, X.; Guo, Y.; Lin, S.; Wang, M.; Xu, J.; Wang, X.; He, G.; Tan, X.; Zhuo, C.; et al. Emergence of Eravacycline Heteroresistance in Carbapenem-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii Isolates in China. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1356353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Zhou, D.; He, J.; Liu, H.; Fu, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Leptihn, S.; Yu, Y.; Hua, X.; Xu, Q. A Panel of Genotypically and Phenotypically Diverse Clinical Acinetobacter baumannii Strains for Novel Antibiotic Development. Microbiol. Spectr. 2024, 12, e00086-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camargo, C.H.; Yamada, A.Y.; de Souza, A.R.; Cunha, M.P.V.; Ferraro, P.S.P.; Sacchi, C.T.; Dos Santos, M.B.; Campos, K.R.; Tiba-Casas, M.R.; Freire, M.P.; et al. Genomic Analysis and Antimicrobial Activity of β-Lactam/β-Lactamase Inhibitors and Other Agents against KPC-Producing Klebsiella pneumoniae Clinical Isolates from Brazilian Hospitals. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 14603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandran, S.; Manokaran, Y.; Vijayakumar, S.; Shankar, B.A.; Bakthavatchalam, Y.D.; Dwarakanathan, H.T.; Yesudason, B.L.; Veeraraghavan, B. Enhanced Bacterial Killing with a Combination of Sulbactam/Minocycline against Dual Carbapenemase-Producing Acinetobacter baumannii. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2023, 42, 645–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, K.L.; Cabang, J.C.; Teo, J. Limited in Vitro Susceptibility of Drug-Resistant Non-Fermenting Gram-Negative Organisms against Newer Generation Antibiotics. Pathology 2023, 55, 583–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopikrishnan, M.; Ramireddy, S.; Varghese, R.P.; Bakathavatchalam, Y.D.; D, T.K.; Manesh, A.; Walia, K.; Veeraraghavan, B.; C, G.P.D. Determination of Potential Combination of Non-β-lactam, Β-lactam, and Β-lactamase Inhibitors/Β-lactam Enhancer against Class D Oxacillinases Producing Acinetobacter baumannii: Evidence from In-vitro, Molecular Docking and Dynamics Simulation. J. Cell. Biochem. 2023, 124, 974–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Zhang, G.; Zhao, Q.; Wang, L.; Yang, J.; Cui, J. In Vitro Antimicrobial Activity and Dose Optimization of Eravacycline and Other Tetracycline Derivatives Against Levofloxacin-Non-Susceptible and/or Trimethoprim-Sulfamethoxazole-Resistant Stenotrophomonas Maltophilia. Infect. Drug Resist. 2023, 16, 6005–6015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.-Y.; Ko, W.-C.; Lee, W.-S.; Lu, P.-L.; Chen, Y.-H.; Cheng, S.-H.; Lu, M.-C.; Lin, C.-Y.; Wu, T.-S.; Yen, M.-Y.; et al. In Vitro Activity of Cefiderocol, Cefepime/Enmetazobactam, Cefepime/Zidebactam, Eravacycline, Omadacycline, and Other Comparative Agents against Carbapenem-Non-Susceptible Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Acinetobacter baumannii Isolates Associated from Bloodstream Infection in Taiwan between 2018–2020. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2022, 55, 888–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, T.; Lai, J.-J.; Huang, W.-C.; Kuo, S.-C.; Chiang, T.-T.; Yang, Y.-S.; The ACTION study group. In Vitro and in Vivo Comparison of Eravacycline- and Tigecycline-Based Combination Therapies for Tigecycline-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. J. Chemother. 2022, 34, 166–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biagi, M.; Tan, X.; Wu, T.; Jurkovic, M.; Vialichka, A.; Meyer, K.; Mendes, R.E.; Wenzler, E. Activity of Potential Alternative Treatment Agents for Stenotrophomonas Maltophilia Isolates Nonsusceptible to Levofloxacin and/or Trimethoprim-Sulfamethoxazole. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2020, 58, e01603-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifert, H.; Stefanik, D.; Olesky, M.; Higgins, P.G. In Vitro Activity of the Novel Fluorocycline TP-6076 against Carbapenem-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2020, 55, 105829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifert, H.; Stefanik, D.; Sutcliffe, J.A.; Higgins, P.G. In-Vitro Activity of the Novel Fluorocycline Eravacycline against Carbapenem Non-Susceptible Acinetobacter baumannii. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2018, 51, 62–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, R.; Yi, Q.L.; Zhuo, C.; Kang, W.; Yang, Q.W.; Yu, Y.S.; Zheng, B.; Li, Y.; Hu, F.-P.; Yang, Y.; et al. Establishment of epidemiological cut-off values for eravacycline, against Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Enterobacter cloacae, Acinetobacter baumannii and Staphylococcus aureus. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2024, 79, 2246–2250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camargo, C.H.; Yamada, A.Y.; de Souza, A.R.; Lima, M.D.J.D.C.; Cunha, M.P.V.; Ferraro, P.S.P.; Sacchi, C.T.; dos Santos, M.B.N.; Campos, K.R.; Tiba-Casas, M.R.; et al. Genomics and Antimicrobial Susceptibility of Clinical Pseudomonas aeruginosa Isolates from Hospitals in Brazil. Pathogens 2023, 12, 918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchaim, D.; Pogue, J.M.; Tzuman, O.; Hayakawa, K.; Lephart, P.R.; Salimnia, H.; Painter, T.; Zervos, M.J.; Johnson, L.E.; Perri, M.B.; et al. Major variation in MICs of tigecycline in Gram-negative bacilli as a function of testing method. J Clin Microbiol. 2014, 52, 2242–2249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karageorgopoulos, D.E.; Kelesidis, T.; Kelesidis, I.; Falagas, M.E. Tigecycline for the Treatment of Multidrug-Resistant (Including Carbapenem-Resistant) Acinetobacter Infections: A Review of the Scientific Evidence. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2008, 62, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kakoullis, L.; Papachristodoulou, E.; Chra, P.; Panos, G. Mechanisms of Antibiotic Resistance in Important Gram-Positive and Gram-Negative Pathogens and Novel Antibiotic Solutions. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karageorgopoulos, D.E.; Falagas, M.E. Current Control and Treatment of Multidrug-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii Infections. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2008, 8, 751–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falagas, M.E.; Vardakas, K.Z.; Kapaskelis, A.; Triarides, N.A.; Roussos, N.S. Tetracyclines for Multidrug-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii Infections. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2015, 45, 455–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falagas, M.E.; Skalidis, T.; Vardakas, K.Z.; Voulgaris, G.L.; Papanikolaou, G.; Legakis, N.; Hellenic TP-6076 Study Group. Activity of TP-6076 against Carbapenem-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii Isolates Collected from Inpatients in Greek Hospitals. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2018, 52, 269–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Phase 3, Randomized, Multicenter, Double-Blind, Double-Dummy, Parallel-Group, Comparative Study to Assess the Efficacy, Safety and Tolerability of Eravacycline Versus Ertapenem in the Treatment of Complicated Intra-Abdominal Infections (cIAI) in Hospitalized Adults. Available online: https://www.chictr.org.cn/showproj.html?proj=37134 (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- A Phase II/III, Randomized, Two-Stage Clinical Study to Assess the Efficacy, Safety and Tolerability of Eravacycline Versus Moxifloxacin in the Treatment of Community-Acquired Bacterial Pneumonia (CABP) in Adult Subjects. Available online: https://www.chictr.org.cn/showproj.html?proj=149425 (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Efficacy and Safety of Eravacycline for Complicated Intra-Abdominal Infections in the ICU: A Multicenter, Single-Blind, Parallel Randomized Controlled Trial Study. Available online: https://www.chictr.org.cn/showproj.html?proj=208164 (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Tetraphase Pharmaceuticals, Inc. A Phase 3, Randomized, Double-Blind, Double-Dummy, Multicenter, Prospective Study to Assess the Efficacy and Safety of Eravacycline Compared with Ertapenem in Complicated Intra-Abdominal Infections. 2021. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT01844856 (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Tetraphase Pharmaceuticals, Inc. A Phase 3, Randomized, Double-Blind, Double-Dummy, Multicenter, Prospective Study to Assess the Efficacy and Safety of Eravacycline Compared with Meropenem in Complicated Intra-Abdominal Infections. 2021. Available online: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT02784704 (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Tetraphase Pharmaceuticals, Inc. A Phase 3, Randomized, Double-Blind, Double-Dummy, Multicenter, Prospective Study to Assess the Efficacy and Safety of Eravacycline Compared with Levofloxacin in Complicated Urinary Tract Infections. 2021. Available online: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT01978938 (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Tetraphase Pharmaceuticals, Inc. A Phase 3, Randomized, Double-Blind, Double-Dummy, Multicenter, Prospective Study to Assess the Efficacy and Safety of IV Eravacycline Compared with Ertapenem in Complicated Urinary Tract Infections. 2021. Available online: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT030325 (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- Cumpston, A. Prospective Evaluation of XeravaTM (Eravacycline) Prophylaxis in Hematological Malignancy Patients with Prolonged Neutropenia. 2024. Available online: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05537896 (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- Tetraphase Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Multicenter, Open-Label Trial to Evaluate the Safety and Tolerability of Intravenous Eravacycline in Pediatric Patients from 8 Years to Less than 18 Years of Age with Complicated Intra-Abdominal Infections (cIAI). 2025. Available online: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT06794541 (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- Scott, L.J. Eravacycline: A Review in Complicated Intra-Abdominal Infections. Drugs 2019, 79, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haeili, M.; Aghajanzadeh, M.; Moghaddasi, K.; Omrani, M.; Ghodousi, A.; Cirillo, D.M. Emergence of Transferable Tigecycline and Eravacycline Resistance Gene tet(X4) in Escherichia Coli Isolates from Iran. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 16581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, X.; Zhang, B.; Xu, G.; Chen, J.; Shang, Y.; Lin, Z.; Yu, Z.; Zheng, J.; Bai, B. In Vitro Activity of the Novel Tetracyclines, Tigecycline, Eravacycline, and Omadacycline, Against Moraxella catarrhalis. Ann. Lab. Med. 2021, 41, 293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Wei, X.; Jin, Y.; Bai, F.; Cheng, Z.; Chen, S.; Pan, X.; Wu, W. Development of Resistance to Eravacycline by Klebsiella pneumoniae and Collateral Sensitivity-Guided Design of Combination Therapies. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e01390-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).