Abstract

The role of purified natural products in the prevention and treatment of countless diseases of bacterial, fungal, and viral origin cannot be overestimated. New antiviral drugs have been obtained from natural sources and transformed into preparations for prophylactic and therapeutic purposes. Flavonoids, polyphenols, saponins, proanthocyanins, polysaccharides, organic acids, proteins, polypeptides, and essential oils derived from plants, animals, or microorganisms can control and combat foodborne viral infections, including hepatitis A. The components of essential oils are characterized by numerous therapeutic and antioxidant properties and exhibit a broad spectrum of antimicrobial and antiviral activity. Due to these properties, they can be used to preserve meat, fruit, vegetables, and their products. Over the past two decades, much effort has been made to identify natural products, mostly of plant origin, to combat foodborne viruses. Natural plant extracts have several potential uses, not limited to increasing the safety of food products and improving their quality, but also as natural antiviral agents.

1. Introduction

Food contaminated with viruses can be a source of contamination for consumers, although foodborne viruses cannot multiply in food, unlike many microorganisms. Hepatitis A virus (HAV) has been associated with many recorded major outbreaks, while other human intestinal viruses such as human astrovirus (HAstV), human rotavirus (HRV), sapovirus (SaV), enterovirus (EV) and Aichi virus (AiV) have caused sporadic outbreaks around the world [1]. According to Yeargin et al., human intestinal viruses were detected in 13.1% and 45% of foodborne outbreaks in the EU and the USA, respectively [2].

The transmission of viruses to humans occurs through the consumption of contaminated food, through direct interpersonal contact, or through the environment, e.g., water [3]. Viruses can contaminate food at different stages of its production, from harvesting to post-harvest [4], and food ingredients can protect the virus during processing and human consumption. For example, fat, sugar, and protein in food can prevent viruses from deactivating [5,6]. The infectious dose of foodborne virus is generally low and a small quantity of virus particles can cause infection. Foodborne viruses can survive in food for long periods without losing infectivity [1]. Heat treatment is an effective means of deactivating foodborne viruses, but it can alter the organoleptic properties (e.g., color and texture) and reduce the nutrient content (e.g., protein and vitamins) of food [7]. Methods based on the use of heat as an effective method of pathogen deactivation are currently used in the food industry to combat bacteria and yeasts [8]. However, thermal deactivation of intestinal viruses, especially HAV in food, has not been fully understood [9,10,11,12]. Several studies have shown that heat treatment induces a conformational change in the capsid, leading to a reduction in initial viral titers, but the effect depends on the heat treatment conditions and the composition of the processed food [13,14]. A wide variety of food items, including drinks and juices, are usually preserved through heat treatment, which is characterized by a combination of two parameters: temperature and time. However, high-temperature treatment negatively affects food quality, ultimately reducing both the nutritional and sensory value of food [15,16].

Foodborne virus outbreaks are frequently associated with minimally processed and ready-to-eat foods, which is why alternative preservation methods are needed to inactivate viruses. It should also be noted that companies responsible for processing food should consider whether innovative non-thermal food processing technologies to deactivate viruses can also deactivate bacterial pathogens, such as Listeria monocytogenes, which may potentially survive in food during cold storage [17].

Gut viruses have received less attention than other foodborne pathogens, and strategies to combat them are necessary to ensure food safety and reduce the number of infections in humans.

Today, vegetables and berries are most commonly associated with intestinal virus outbreaks as they are generally eaten fresh or mildly processed (e.g., frozen or freeze-dried blueberries, blanched vegetables), increasing the risk of infection. These foods are prone to contamination due to the use of fecally contaminated water for irrigation or the lack of proper hygiene among food contact persons [18,19].

The consumption of fresh vegetables has increased significantly around the world with the advent of new technologies, and a wide range of products, from packaged salads to freshly cut fruit, makes the consumption of fresh fruit and vegetables affordable and convenient for consumers.

The consumption of fresh produce is part of a healthy diet, but pathogenic contamination has serious public health implications. Outbreaks of infections are often associated with tomatoes, spinach, lettuce, and seed sprouts. Vegetables can become contaminated with human pathogens at several points along the production chain [20].

Clear strategies for identifying sources of pathogens should be developed and steps taken to prevent contamination of vegetables along the entire production chain [21]. Sources of plant contamination have been broken down into pre-harvest (focused on improving soil quality, irrigation water, climate change, and geographic location) and post-harvest (harvesting, handling, and processing).

Potential sources of pathogen contamination prior to harvest include soil, wildlife feces, soil alteration, agricultural water, reconstituted fungicides and insecticides, dust, wild or domestic animals, field workers, and harvesting equipment [20,22,23]. Research shows that animal manure used to improve soil can contain viruses, parasites, or bacteria, which pose a risk to human health.

Irrigation is considered to be one of the most important ways of transmitting intestinal human intestinal pathogens to vegetables [24].

It is known that plants produce secondary metabolites with antimicrobial activity in response to pathogen attack as a defense mechanism. Today, there has been a significant increase in the interest of usage of natural products as effective antiviral therapeutic agents. This paper discusses the action of selected essential oils and natural products against hepatitis A virus. Recent in vitro study revealed that green tea extract (GTE) demonstrated excellent antiviral activity against hepatitis A virus under controlled conditions of concentration, pH, temperature, and also time exposure. It now appears that grape seed extract (GSE) exhibits rather greater antiviral activity by potentially blocking host cell receptors and consequently preventing virus entry, replication, and infection, while not causing any structural damage to the HAV viral capsid. In turn, proanthocyanidins from blueberries slightly reduce HAV replication in the host cells, but they interrupt HAV binding and penetration to a much greater extent. Research into natural anti-HAV products is promising as several have shown remarkable potential for controlling HAV infection and replication. These natural agents have been shown to exhibit significant antiviral activity against HAV and can act at different stages of the virus life cycle, replication, assembly, release, as well as targeting specific virus–host interactions.

The aim of the study was to evaluate, based on the available literature, the effect of essential oils and plant substances on the growth and survival of HAV.

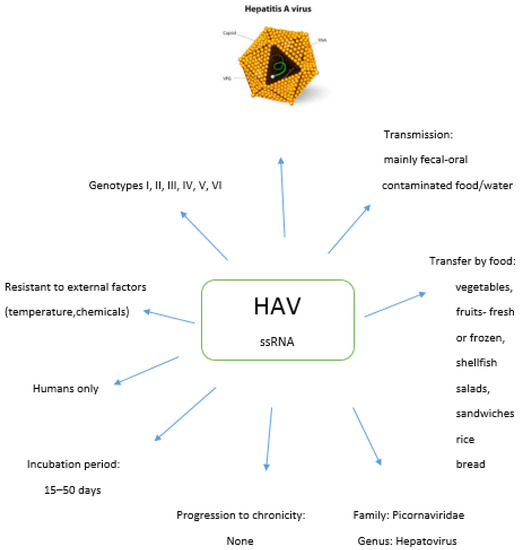

2. Hepatitis A Virus

Hepatitis A virus (HAV), the cause of hepatitis A, is responsible for approximately 1.5 million reported cases and tens of millions of infections each year. Although hepatitis A is a self-limiting disease of the liver, it sometimes progresses to a severe, life-threatening form. HAV is a non-enveloped, single-stranded, positive polarity RNA virus belonging to Enteroviruses, genus Hepatovirus, family Picornaviridae, and can survive for several weeks in water or sewage. The HAV virus is resistant to external factors (temperature, chemicals, e.g., acids). It is stable in an environment with a high degree of acidification (pH 3) for about 4 h, which makes it resistant to digestive enzymes, which helps to survive the passage through the stomach on the way to another replication site in the small intestine. It is deactivated by autoclaving, boiling, UV radiation, disinfectants containing chlorine, or formalin. The viral particle is spherical, non-enveloped, 27 nm in diameter [25,26].

2.1. Genotypes of HAV

The HAV genome is approximately 7500 nucleotides, consisting of untranslated regions and a coding region. The coding region encodes a large polyprotein and has been divided into P1, P2 and P3 segments. P1 is translated into the three major viral capsid proteins, VP1, VP2, VP3 and VP4, which plays a role in virion formation. Non-structural proteins are generated by cleavage of P2 and P3 by proteases. The genome is heterogeneous, which allows the classification of HAV into six genotypes and several sub-genotypes. Heterogeneity has a limited effect on antigen diversity and results in the existence of single serotypes. So far, six genotypes have been identified (I, II, III, IV, V and VI) [27]. The most frequently isolated genotypes in humans are I and III. On the other hand, three consecutive genotypes (IV, V and VI) occur in monkeys of the macaque family (Cercopithecidae). Within genotypes I, II and III, sub-genotypes A and B are distinguished. HAV genotypes and sub-types do not occur evenly all around the world, and genotype I is the most common. In areas characterized by low endemicity, such as North America and Europe, the most common is sub-genotype IA. Furthermore, other genotypes and sub-genotypes, such as IB and IIIA, are also isolated in Europe. The IA and IB subtypes are widespread in North and South America, Europe, China, Japan, and Thailand. Most of the human strains beyond genotype I belong to sub-genotype IIIA and are found in India, Kazakhstan, Europe, and the USA. The most common sub genotype in the USA is IA, followed by the IB and IIIA sub-genotypes [28].

Recent studies have shown that HAV is evolutionarily different from other picornaviruses, not only in the nucleotide sequence of its genome, but also in the structure of its capsid, which shares features with primitive insect viruses. Although for many years only humans and other primate species were susceptible to infection with hepatoviruses, numerous distinct species of hepatovirus closely related to human HAV have recently been identified in various species of small mammals and are now classified under the same genus. Unlike many other picornaviruses, including the well-studied poliovirus, HAV does not block cellular protein synthesis in infected cells and generally replicates without a cytopathic effect. One of the most interesting functions of the virus is its recently recognized non-lytic ability to be released from infected cells in a membrane-wrapped form as infectious quasi-enveloped virions (eHAVs). eHAV particles are similar in infectivity to the non-enveloped virion and represent the second form of infectious virus [29].

2.2. Food Sources of HAV

Hepatitis A is mainly infected by the fecal–oral route (“dirty hands” disease). Infection can occur through direct contact with an infected person, consumption of contaminated food, consumption of contaminated water (also in the form of ice cubes), washing hands in contaminated water or following sexual contact with an infected person. Foods involved in the transfer of HAV include vegetables, fruits (fresh or frozen, especially berries), reconstituted frozen orange juice, shellfish, salads, sandwiches, ice cream, cheese, rice pudding, frozen dough, pudding, milk, bread, biscuits, and other raw or undercooked foods. Food may become contaminated with HAV in several different ways: fruits and vegetables grown and/or irrigated with fecally contaminated materials, crustaceans grown in and harvested from dung waters, food processing and preparation using fecally contaminated equipment or machinery, and handling of ready-to-eat food products by infected persons with poor personal hygiene. Food establishments with poor sanitation and inadequate waste disposal systems, along with unsatisfactory manufacturing practices, can also contribute to food contamination [30,31]. Frozen fruit has been shown to be a major carrier of foodborne illness attributed to hepatitis A virus (HAV) infections. Fresh products can become infected with viruses through direct contact with a contaminated surface, water, or hands, and then frozen without proper sanitation. Due to their structural integrity, foodborne viruses are able to withstand hostile conditions such as drying out and freezing and survive for long periods without losing infectivity. In addition, these foods are often eaten raw or undercooked, increasing the risk of infection. The Nasheri results revealed that frozen fruit, especially blueberries and pomegranate shells, contributed to most of the outbreaks, with outbreaks frequently reported in industrialized countries [32]. Analyses of the persistence of HAV RNA in water, on non-porous surfaces, and on blueberries were performed. A study by Trudel-Ferland showed that RNA associated with deactivated HAV persists significantly over time on non-porous surfaces and on foods over a wide temperature range. Stability at above freezing temperatures is also a cause for concern, although less so [33].

2.3. Epidemiology of HAV

The time from infection to the onset of symptoms may be 15 to 50 days (average 30 days). An infected person sheds large amounts of the virus in their feces for up to several weeks, and shedding may begin 2 to 3 weeks before the onset of jaundice, that is, while the person appears to be healthy. The excretion of the virus in the feces may take up to 6 weeks following infection. Prolonged viral excretion via the feces occurs mainly in children, while in immunocompetent adults the amount of virus excreted in the feces drops sharply after the onset of jaundice. The virus is also found in the blood and saliva of an infected person. Household members and sexual partners of infected people, intravenous drug users, and those traveling to endemic areas of hepatitis A are at increased risk of infection [34].

HAV infection is asymptomatic or with mild symptoms or symptoms varying in intensity from flu-like symptoms (in the first stage) and gastrointestinal symptoms—belching, heartburn, nausea, flatulence, early satiety, dark urine—to jaundice (i.e., yellowing skin, whites of the eyes, or mucous membranes). Acute inflammation and damage to the liver parenchyma may occur. In adults, the disease has a sudden onset and is severe, requiring hospitalization, occurring in the form of jaundice in 70% of people. In children up to 5 years of age, illnesses are rare, and if they do occur, the disease is asymptomatic or very mild. Over 70% of children under 6 years of age and 20% of children over 6 years of age have asymptomatic HAV infections. The severity of the disease is higher in the older age groups [34]. HAV complications are dangerous and can even lead to death. Complications of hepatitis A include hyperacute hepatitis and bone marrow aplasia. Hepatitis A virus does not cause chronic hepatitis, and immunity after falling ill is life-long. The long incubation period of viruses such as HAV makes it difficult to accurately determine the food product that is the source of infection for the people infected.

In animal models, HAV antigens can be detected in the stomach, small intestine, and large intestine throughout the duration of the infection, suggesting that some degree of viral replication is present in the gut. HAV reaches the liver via systemic circulation and infects hepatocytes. On entry into a cell, HAV interacts with HAVCR1, with a receptor attachment present on the cell surface. Additionally, HAVCR2 and the asialoglycoprotein receptor have been reported to participate in HAV entry into the cell. After replication in the liver, the virus is released into the bile and eventually excreted in the feces [35].

It is believed that the course of viral hepatitis is genetically determined by the variability of the hosts, whilst infection with the same virus leads to different disease courses of individuals. The molecular mechanisms responsible for the wide range of disease severity caused by HAV infection are not well understood. It is widely accepted that virulence factors associated with specific viral lines and various host factors such as age, sex, and race play a role in the clinical outcomes of HAV infections [35].

It is estimated that almost 80% of the population aged 30–55 is non-immune. The elderly over 70 years of age are immunized after exposure to the virus, but only 6.5% of adults up to 40 years of age have HAV antibodies. Figure 1 shows the characteristics of HAV.

Figure 1.

Characteristics of HAV.

Annually, between 1.2 and 1.4 million cases of the disease are recorded, although there are actually many more cases, as it is estimated that only every tenth case of the disease is reported. Overall, the WHO estimated that 7134 people worldwide died from hepatitis A in 2016 (corresponding to 0.5% of the death rate from hepatitis). Among the sick, 20% require hospitalization, and mortality is low, at 0.6–2.1%. HAV infections most often occur in areas of poor sanitary conditions, among people who do not observe good personal hygiene. The countries with high endemic incidence of HAV include Bulgaria, Egypt, Tunisia, countries of the Mediterranean basin and Africa, countries of Eastern Europe, and Russia [25,26,36].

Foodborne HAV outbreaks have previously occurred concerning, for example, infections caused by the consumption of frozen or fresh blueberries and sun-dried tomatoes, as well as oysters and other crustaceans. Food contact can be another source of HAV, as HAV is environmentally stable and can remain contagious for long periods in the environment and on inanimate surfaces. An epidemic, recorded in Germany in 2017–2018, was caused by one of the HAV strains identified from those infected with an MSM group combined with a contact person working in a food store as the most likely source of the outbreak. Through contact tracing, two direct contacts were diagnosed by stool examinations, and over the next few weeks, seven of the store’s customers were identified as confirmed cases [34].

Based on data published by ECDC in 2018, a total of 42 atypical cases of hepatitis A were reported in six European Union (EU) countries. They were infected with one of two different strains of hepatitis A virus (HAV) genotype IA. The cases were classified as either indigenous, i.e., infected in the EU, or travel-related, i.e., travel history to Morocco. Both HAV strains have historically been found to be epidemiologically linked to Morocco. However, many of the 2018 cases have no history of travel to Morocco. These cases were identified by sequencing the viral RNA fragment in the VP1/P2A overlap region. HAV strains with one to two nucleotide differences in this RNA region are likely to have a common ancestry. Based on the molecular findings on returning Moroccan travelers and residents of Morocco, it is likely that these strains have been circulating in Morocco since at least 2011 and this transmission in Morocco continued until recently.

In EU countries in 2012–2014, strains associated with two foodborne disease outbreaks were related to the consumption of frozen strawberries and frozen mixed berries [26,36,37,38]. In 2016–2018 in the USA, the number of hepatitis A infections increased by 294% compared to 2013–2015; they were mainly associated with outbreaks related to contaminated foodstuffs, among MSM, and mainly among those reporting drug use or homelessness [39].

3. Composition and Biological Activity of Essential Oils

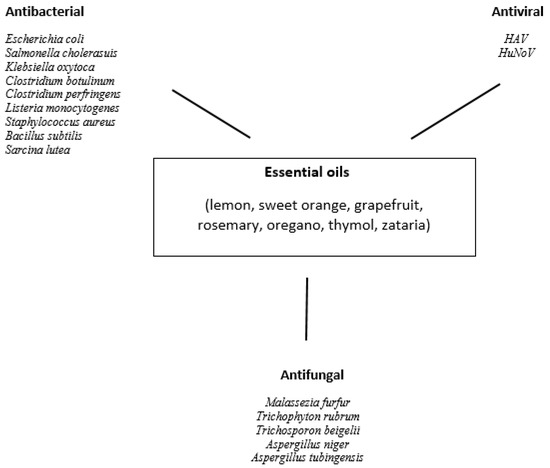

Essential oils (EOs) are liquid, volatile fragrances which are most often obtained by steam distillation from a suitable plant material. They are a mixture of various compounds, such as ketones, aldehydes, alcohols, esters, lactones, terpenes, and organic compounds. The components of essential oils are characterized by numerous therapeutic and antioxidant properties and exhibit a broad spectrum of antimicrobial and antiviral qualities. Due to these properties, they can be used to preserve meat, fruit, vegetables, and their preserves.

The available literature provides information on the use of various EOs against hepatitis A virus (HAV). These oils include oregano oil, thyme oil, Zataria multiflora oil, lemon oil, sweet orange oil, grapefruit oil, rosemary oil, C. indicum oil, and C. morifolium oil.

The main components of oregano EO extracted from Origanum vulgare are carvacrol (0.3–80.8%), belonging to the monoterpenes; and thymol (0.96–63.7%), belonging to the sesquiterpenes. The other ingredients present in lower proportions are gamma-terpinene (0.8–21.0%), P-cymene (<0.1–16.94%), alpha-terpineol (<0.09–12.0%), and limonene (0.3–0.7%) [40,41]. Numerous in vitro and in vivo studies have shown the antibacterial, antiviral, and antifungal effects of the oregano EO. This essential oil was shown to possess antibacterial activity against Gram-negative bacteria: Escherichia coli, Salmonella choleraesuis, Salmonella Typhimurium, Shigella sonnei, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Klebsiella oxytoca and Gram-positive bacteria: Clostridium botulinum, Clostridium perfringens, Listeria monocytogenes, Staphylococcus aureus, Bacillus subtilis, Sarcina lutea, and Mariniluteicoccus flavus [42]. The oregano essential oil was also shown to be effective against fungal pathogens—Candida albicans, Malassezia furfur, Trichophyton rubrum, Trichosporon beigelii, Aspergillus niger, and Aspergillus tubingensis [43,44,45,46]. Due to antimicrobial, antifungal, and antioxidative properties oregano essential oil can be used as a food preservative [47]. Studies have shown that these properties are related to the presence of carvacrol and thymol [48].

The main ingredient of the essential oil obtained from Thymus vulgaris is thymol belonging to sesquiterpenes (27.6–100%). The other ingredients of thyme oil are trans-sabinene hydrate (0.43–39.4%), menthol (1.3–39%), bornyl acetate (0.2–25.57%), limonene (0.4–24.2%), carvacrol (2.0–20.5%), and gamma-terpinene (0.6–14.9%) belonging to monoterpenes [40,49,50]. The research results presented by Borugă et al. 2014 showed the effectiveness of thyme EO against the food-related bacteria and fungus—S. aureus, P. aeruginosa, S. Typhimurium, E. coli, K. pneumoniae, E. faecalis, and C. albicans. This antimicrobial property of EO could be attributed to the presence of the major constituent—thymol. The antioxidant properties of the T. vulgaris EO allow it to be used as a food additive as a means of protecting it from spoilage [51].

The main active substances in the essential oil obtained from Zataria multiflora Boiss are thymol (40.8%), belonging to sesquiterpenes; and carvacrol (27.8%), belonging to monoterpenes. P-cymene—alkylbenzene related to a monoterpene (8.4%), sesquiterpene—beta-caryophyllene (2.0%), and monoterpenes: gamma-terpinene (4.0%), linalol (1.7%), and alpha-terpinolene (1.3%) are the remaining ingredients of the oil [40,52]. It was found that Z. multiflora EO has antimicrobial properties. The growth of P. aeruginosa, K. pneumoniae, methicillin-resistant and methicillin-sensitive S. aureus strains was inhibited in the presence of EO [52,53,54,55]. The key ingredients, carvacrol and thymol, are responsible for the antimicrobial and antioxidant properties of Z. multiflora EO [55]. This EO exhibits positive antioxidant, antibacterial, and antifungal properties, and can therefore function as an effective preservative in food—for example, in cookies or hamburgers [56,57].

Limonene, beta-pinene, and gamma-terpinene, belonging to monoterpenes, are the key components of the essential oil derived from lemon essential oil (Citrus limon). Their content is 61.09–71.18%, 10.03–13.41%, and 7.73–9.89%, respectively. In much smaller quantities are geranial (1.9–2.4%) and neral (1.39–1.77%), belonging to monoterpene aldehydes [40,58,59]. Lemon EO showed antibacterial properties against Gram-positive strains: MRSA, MSSA, E. faecalis, L. monocytogenes, B. subtilis and Gram-negative strains: E. coli, K. pneumoniae, and P. aeruginosa [58,60,61]. The antifungal activity of lemon oil against some food spoilage fungal species, especially Aspergillus and Penicillium species, was also described [62]. C. limon EO can be use in the prevention of contamination and growth of pathogenic bacteria during minced beef meat storage at 4 °C [58]. Ajayi-Moses et al. 2019 [63] noted that lemon EO exhibited pronounced inhibitory potential against microorganisms associated with fruits spoilage; therefore, it can be used as a preservative agent.

The main ingredients of sweet orange EO derived from Citrus sinensis are limonene (92.1–95.9%) and linalool (0–5.6%) [40,59,64]. Sweet orange EO was reported to inhibit the growth of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, including S. aureus, L. monocytogenes, Vibrio parahaemolyticus, S. Typhimurium, E. coli, and P. aeruginosa [65,66,67], as well as several fungal species, such as Aspergillus flavus, Aspergillus fumigatus, Aspergillus terreus, A. niger, Alternaria alternata, Cladosporium herbarum, Curvularia lunata, Fusarium oxysporum, Helminthosporium oryzae, Penicillium chrysogenum, Penicillium verrucosum, and Trichoderma viride [68,69,70]. Sweet orange EO exhibits antioxidant, antifungal, and antibacterial properties, which have important applications in food industries [71,72].

Limonene is the main ingredient in grapefruit EO (Citrus paradisi). Its content ranges from 84.8 to 93.45%. The remaining ingredients are present in small quantities: myrcene (6.9%) and alpha-pinene (1.7%), belonging to monoterpenes; and beta-caryophyllene (1.1%), belonging to sesquiterpenes [40,59,73]. C. paradisi EO inhibited the growth of E. coli, S. aureus, E. faecalis, S. Typhimurium, Lactococcus lactis, Leuconostoc mesenteroides, Lactobacillus plantarum, Staphylococcus epidermidis, Serratia marcescens, and Proteus vulgaris [73,74,75]. The effectiveness of C. paradisi EO against fungi: A. niger, A. flavus, C. albicans, Penicillium chrysogenum, Fusarium moniliforme and Saccharomyces cerevisiae has been confirmed [76]. According to Luciardi et al. 2019 [77], grapefruit essential oils could be used as a food preservative to control P. aeruginosa virulence.

The major constituents of essential oils from Rosmarinus officinalis are 1,8-cineole (16.0–58.6%), alpha-pinene (2.5–48.0%), and camphor (1.4–26.0%). Much smaller amounts of alpha-terpineol (0.7–12.8%), beta-caryophyllene (0.5–13.6%), borneol (1.0–9.0%), camphene (1.7–7.0%), limonene (1.8–5.4%), and beta-pinene (0.7–3.8%) are also present in the oil [40,59,78]. EO from R. officinalis has been demonstrated as having antibacterial properties against E. coli, P. aeruginosa, S. aureus, B. subtilis, Bacillus cereus, Bacillus pumilis, Clostridium perfringens, Aeromonas hydrophila, Salmonella choleraesuis, and Salmonella poona [79,80]. Rosemary EO exhibited fungitoxic activity against Penicillium spp., A. niger, and A. flavus [81,82,83]. Due to its antimicrobial and antioxidative properties, rosemary EO can be successfully used as a food preservative, especially in foods that contain animal or vegetable fats [84].

Chrysanthemum indicum essential oil contains camphor (7.75–36.69%), bornyl acetate (10.00–21.33%), and borneol (3.3–18.34%) as the major constituents followed by 1,8-cineole (0.12–10.4%), alpha-terpinene (5.73%), and caryophyllene oxide (0.13–5.46%) [85,86,87]. The essential oil of C. indicum exhibited stronger antibacterial activity against all oral bacteria: Streptococcus mutans, Streptococcus sanguinis, Streptococcus sobrinus, Streptococcus ratti, Fusobacterium nucleatum, Prevotella intermedia, and Porphylomonas gingivalis. E. coli and S. aureus strains appeared to be less sensitive to C. indicum EO [85]. Shunying et al. 2005 demonstrated the strong activity of the essential oil against clinical (E. coli, K. pneumoniae, Staphylococcus saprophyticus, Enterobacter cloacae) and reference (B. subtilis, S. aureus, Salmonella typhi) bacterial strains. Fungi: Candida spp. and Hansenula anomala were also sensitive to C. indicum EO [86]. The anti-infectious and antioxidant properties of C. indicum EO make it suitable for use as a food spice to preserve it and protect it from deterioration [87].

Chrysanthenone was also the predominant component of Chrysanthemum morifolium essential oil (9.71–48.96%). The other ingredients of the oil are verbenone (17.33%), camphor (14.56–44.6%), curcumene (10.50%), eudesmol (8.92%), pentacosane (8.65%), borneol (7.95%), and copaene (5.61%) [87,88,89]. The essential oil of C. morifolium exhibits significant inhibitory effects toward E. coli, S. aureus, S. epidermidis, S. Typhimurium, S. sonnei, Shigella flexneri, Citrobacter freundii, Streptococcus agalactiae, Streptococcus pyogenes, and Pseudomonas fluorescens [87,89]. Bacteria P. aeruginosa and K. pneumoniae were resistant to the essential oil [89]. Other research suggests that secondary metabolites of C. morifolium possess antifungal activity against F. oxysporum, Magnaporthe oryzae, and Verticillium dahlia [90]. C. morifolium EO, just like C. indicum EO, can be used as a food preservative due to its antimicrobial and antioxidative properties [87]. The effect of essential oils on microorganisms is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Effects of essential oils on microorganisms.

5. Conclusions

Viruses, including HAV, may cause foodborne diseases. As there is an increasing demand for food that does not contain synthetic chemicals as preservatives, it is imperative to research and identify alternative and safe methods for protecting food products. Even though many natural products are produced today to preserve and extend the shelf life of foodstuffs, there are still many unexplored sources. The natural compounds from the by-products of plants, algae, and fungi are now seen as possible compounds to use as new antimicrobial agents. More research is needed to determine the optimal concentrations of antimicrobials that can be safely used in food without unduly altering any sensory characteristics. The antiviral effect of essential oils, including HAV, as well as extracts and plant substances depends on the concentration of the active substance, its duration of action, and temperature.

Essential oils and extracts are safe and environmentally friendly, and many essential oils have anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, antifungal, antiviral, and antiseptic properties. EO plays an important role in food processing due to the myriad of characteristics mentioned above.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.J.-K., M.F.-M. and J.S.; formal analysis, A.J.-K.; writing—original draft preparation, A.J.-K. and M.F.-M.; writing review and editing, A.J.-K., D.W., I.C.-K. and M.F.-M.; supervision, A.J.-K. and M.F.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Sánchez, G.; Bosch, A. Survival of Enteric Viruses in the Environment and Food. Vir. Food. 2016, 26, 367–392. [Google Scholar]

- Yeargin, T.; Gibson, K.E. Key characteristics of foods with an elevated risk for viral enteropathogen contamination. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2018, 26, 996–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Koopmans, M.; Duizer, E. Foodborne viruses: An emerging problem. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2004, 90, 23–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, Z.; Shah, M.P.; Wikswo, M.E.; Barclay, L.; Kisselburgh, H.; Kambhampati, A.; Cannon, J.L.; Parashar, U.D.; Vinjé, J.; Hall, A.J. Epidemiology of foodborne norovirus outbreaks–United States, 2009–2015. Food Saf. 2018, 6, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Deboosere, N.; Legeay, O.; Caudrelier, Y.; Lange, M. Modelling effect of physical and chemical parameters on heat inactivation kinetics of hepatitis A virus in a fruit model system. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2004, 93, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirneisen, K.A.; Black, E.P.; Cascarino, J.L.; Fino, V.R.; Hoover, D.G.; Kniel, K.E. Viral inactivation in foods: A review of traditional and novel food-processing technologies. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2010, 9, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aadil, R.H.; Roobab, U.; Mann, A.A. Effect of heat on food properties. In Encyclopedia of Food Chemistry; Melton, L., Shahidi, F., Varelis, P., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 70–75. [Google Scholar]

- Stumbo, C.R. Thermobacteriology in Food Processing; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bartsch, C.; Plaza-Rodriguez, C.; Trojnar, E.; Filter, M.; Johne, R. Predictive models for thermal inactivation of human norovirus and surrogates in strawberry puree. Food Control. 2019, 96, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozkurt, H.; D’Souza, D.H.; Davidson, P.M. Thermal inactivation of foodborne enteric viruses and their viral surrogates in foods. J. Food Prot. 2015, 78, 1597–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Wu, X.; Sánchez, G.; Randazzo, W. Viability RT-qPCR to detect potentially infectious enteric viruses on heat-processed berries. Food Control. 2020, 107, 106818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, L.; Chen, H.; Hicks, D.; Wu, C. Thermal inactivation of human norovirus surrogates in oyster homogenate. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2018, 281, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deboosere, N.; Pinon, A.; Delobel, A.; Temmam, S.; Morin, T.; Merle, G.; Blaise-Boisseau, S.; Perelle, S.; Vialette, M. A predictive microbiology approach for thermal inactivation of Hepatitis A virus in acidified berries. Food Microbiol. 2010, 7, 962–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosch, A.; Gkogka, E.; Le Guyader, F.S.; Loisy-Hamon, F.; Lee, A.; van Lieshout, L.; Marthi, B.; Myrmel, M.; Sansom, A.; Schultz, A.C.; et al. Foodborne viruses: Detection, risk assesment, and control options in food processing. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2018, 285, 110–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koskiniemi, C.B.; Truong, V.D.; McFeeters, R.F.; Simunovic, J. Quality evaluation of packaged acidified vegetables subjected to continuous microwave pasteurization. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2013, 54, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, J.; Wang, D.; Zhao, G. Mechanism of discoloration in processed garlic and onion. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2013, 30, 162–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todd, E.C.D.; Greig, J.D. Viruses of foodborne origin: A review. Virus Adapt. Treat. 2015, 7, 25–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carter, M.J. Enterically infecting viruses: Pathogenicity, transmission and significance for food and waterborne infection. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2005, 98, 1354–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kokkinos, P.; Kozyra, I.; Lazic, S.; Söderberg, K.; Vasickova, P.; Bouwknegt, M.; Rutjes, S.; Willems, K. Virological quality of irrigation water in leafy green vegetables and berry fruits production chains food. Environ. Virol. 2017, 9, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matthews, K.R. Sources of enteric pathogen contamination of fruits and vegetables: Future directions of research. Stewart. Postharvest. Rev. 2013, 9, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, M.P.; Erickson, M.C. Opportunities for mitigating pathogen contamination during on-farm food production. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2012, 152, 54–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beuchat, L.R. Vectors and conditions for preharvest contamination of fruits and vegetables with pathogens capable of causing enteric diseases. Br. Food J. 2006, 108, 38–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, K.R. Leafy vegetables. In The Produce Contamination Problem. Causes and Solutions; Matthews, K.R., Sapers, G.M., Gerba, C.P., Eds.; Elsevier: Waltham, MA, USA, 2014; pp. 187–205. [Google Scholar]

- Park, S.; Szonyi, B.; Gautam, R.; Nightingale, K.; Anciso, J.; Ivanek, R. Risk factors for microbial contamination in fruits and vegetables at the preharvest level: A systematic review. J. Food Prot. 2012, 75, 2055–2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Global Hepatitis Report 2017; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Multi-Country Outbreak of Hepatitis A Virus Genotype IA Infections Affecting EU Countries in 2018—21 May 2018; European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control: Stockholm, Sweden, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Debing, Y.; Neyts, J.; Thibaut, H.J. Molecular biology and inhibitors of hepatitis A virus. Med. Res. Rev. 2014, 34, 895–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vaughan, G.; Xia, G.; Forbi, J.C.; Purdy, M.A.; Rossi, L.M.; Spradling, P.R.; Khudyakov, Y.E. Genetic relatedness among hepatitis A virus strains associated with food-borne outbreaks. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e74546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- McKnight, K.L.; Lemon, S.M. Hepatitis A Virus Genome Organization and Replication Strategy. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect Med. 2018, 8, a033480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sattar, S.A.; Jason, T.; Bidawid, S.; Farber, J. Foodborne spread of hepatitis A: Recent studies on virus survival, transfer and inactivation. Can. J. Infect. Dis. 2000, 11, 159–163. [Google Scholar]

- Bozkurt, H.; Phan-Thien, K.Y.; van Ogtrop, F.; Bell, T.; McConchie, R. Outbreaks, occurrence, and control of norovirus and hepatitis a virus contamination in berries: A review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 61, 116–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasheri, N.; Vester, A.; Petronella, N. Foodborne viral outbreaks associated with frozen produce. Epidemiol. Infect. 2019, 18, e291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trudel-Ferland, M.; Jubinville, E.; Jean, J. Persistence of Hepatitis A Virus RNA in water, on non-porous surfaces, and on blueberries. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 618352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marosevic, D.; Belting, A.; Schönberger, K.; Carl, A.; Wenzel, J.J.; Brey, R. Hepatitis A outbreak in the general population due to a MSM-associated HAV genotype linked to a food handler, November 2017–February 2018, Germany. Food Environ. Virol. 2019, 11, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaughan, G.; Goncalves Rossi, L.M.; Forbi, J.C.; de Paula, V.S.; Purdy, M.A.; Xia, G.; Khudyakov, Y.E. Hepatitis A virus: Host interactions, molecular epidemiology and evolution. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2014, 21, 227–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Epidemiology and Surveillance of Infectious Diseases. Laboratory of Monitoring and Epidemiological Analysis. NIZP-PZH-GIS. Warszawa, Poland. 2020. Available online: http://wwwold.pzh.gov.pl/oldpage/epimeld/2019/index_mp.html (accessed on 6 May 2021).

- Polański, P.; Sadkowska-Todys, M. Hepatitis A in Poland in 2016. Epidemiol. Rev. 2018, 72, 433–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polański, P.; Radziszewski, F.; Księżak, E.; Wiktor, A.; Sadkowska-Todys, M. Foodborne infections and intoxications in Poland in 2017. Przegl. Epidemiol. 2019, 7, 451–462. [Google Scholar]

- Foster, M.A.; Hofmeister, M.G.; Kupronis, B.A.; Lin, Y.; Xia, G.L.; Yin, S.; Teshale, E. Increase in Hepatitis A Virus Infections—United States, 2013–2018. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2019, 68, 413–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Essoil Database. Available online: http://www.nipgr.ac.in/Essoildb/ (accessed on 6 May 2021).

- Leyva-López, N.; Gutiérrez-Grijalva, E.P.; Vazquez-Olivo, G.; Heredia, J.B. Essential oils of oregano: Biological activity beyond their antimicrobial properties. Molecules. 2017, 22, 989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Swamy, M.K.; Akhtar, M.S.; Sinniah, U.R. Antimicrobial properties of plant essential oils against human pathogens and their mode of action: An updated review. Evid. Based Complementary Altern. Med. 2016, 2016, 3012462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adam, K.; Sivropoulou, A.; Kokkini, S.; Lanaras, T.; Arsenakis, M. Antifungal activities of Origanum vulgare subsp. hirtum, Mentha spicata, Lavandula angustifolia, and Salvia fruticosa essential oils against human pathogenic fungi. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1998, 46, 1739–1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleff, M.B.; Madrid, I.; Meinerz, A.R.; Meireles, M.C.A.; Braga de Mello, J.R.; Rodrigues, M.R.; Escareño, J.J.H. Essential oils against Candida spp.: In vitro antifungal activity of Origanum vulgare. Afr. J. Microbiol. Res. 2013, 7, 2245–2250. [Google Scholar]

- Císarová, M.; Tančinová, D.; Medo, J. Antifungal activity of lemon, eucalyptus, thyme, oregano, sage and lavender essential oils against Aspergillus niger and Aspergillus tubingensis isolated from grapes. Potravinarstvo 2016, 10, 83–88. [Google Scholar]

- Lakhrissi, B.; Boukhraz, A.; Barrahi, M.; Hartiti, H.E.; Ouhssine, M. Antifungal activity of essential oil of oregano (Origanum vulgare), marjoram (Origanum majorana) and synergy of two essential oils against Candida albicans. Int. J. Res. Stud. Sci. Eng. 2016, 3, 14–17. [Google Scholar]

- Tuttolomondo, T.; La Bella, S.; Licata, M.; Virga, G.; Leto, C.; Saija, A.; Trombetta, D.; Tomaino, A.; Speciale, A.; Napoli, E.M.; et al. Biomolecular characterization of wild sicilian oregano: Phytochemical screening of essential oils and extracts, and evaluation of their antioxidant activities. Chem. Biodivers. 2013, 10, 411–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martucci, J.F.; Gende, L.B.; Neira, L.M.; Ruseckaite, R.A. Oregano and lavender essential oils as antioxidant and antimicrobial additives of biogenic gelatin films. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2015, 71, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borugă, O.; Jianu, C.; Mişcă, C.; Goleţ, I.; Gruia, A.T.; Horhat, F.G. Thymus vulgaris essential oil: Chemical composition and antimicrobial activity. J. Med. Life 2014, 7, 56–60. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kryvtsova, M.V.; Salamon, I.; Koscova, J.; Bucko, D.; Spivak, M. Antimicrobial, antibiofilm and biochemichal properties of Thymus vulgaris essential oil against clinical isolates of opportunistic infections. Biosyst. Divers. 2019, 27, 270–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, Y.; Niu, Y.; Luo, Y.; Ge, M.; Yang, T.; Yu, L.L.; Wang, Q. Fabrication, characterization, and antimicrobial activity of thymol-loaded zein nanoparticles stabilized by sodium caseinate–chitosan hydrochloride double layers. Food Chem. 2014, 142, 269–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahboubi, M.; Heidarytabar, R.; Mahdizadeh, E. Antibacterial activity of Zataria multiflora essential oil and its main components against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Herba Pol. 2017, 63, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mahboubi, M.; Bidgoli, F.G. Antistaphylococcal activity of Zataria multiflora essential oil and its synergy with vancomycin. Phytomedicine 2010, 17, 548–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saei-Dehkordi, S.S.; Tajik, H.; Moradi, M.; Khalighi-Sigaroodi, F. Chemical composition of essential oils in Zataria multiflora Boiss. from different parts of Iran and their radical scavenging and antimicrobial activity. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2010, 48, 1562–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eftekhar, F.; Zamani, S.; Yusefzadi, M.; Hadian, J.; Ebrahimi, S.N. Antibacterial activity of Zataria multiflora Boiss essential oil against extended spectrum β lactamase produced by urinary isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Jundishapur J. Microbiol. 2011, 4, S43–S49. [Google Scholar]

- Samadi, N.; Sharifan, A.; Emam-Djomeh, Z.; Salehi Sormaghi, M.H. Biopreservation of hamburgers by essential oil of Zataria multiflora. Nat. Prod. Res. 2012, 26, 665–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kordsardouei, H.; Barzegar, M.; Sahari, M.A. Application of Zataria multiflora Boiss. and Cinnamon zeylanicum essential oils as two natural preservatives in cake. Avicenna J. Phytomed. 2013, 3, 238–247. [Google Scholar]

- Hsouna, A.B.; Halima, N.B.; Smaoui, S.; Hamdi, N. Citrus lemon essential oil: Chemical composition, antioxidant and antimicrobial activities with its preservative effect against Listeria monocytogenes inoculated in minced beef meat. Lipids Health Dis. 2017, 16, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Battistini, R.; Rossini, I.; Ercolini, C.; Goria, M.; Callipo, M.R.; Maurella, C.; Pavoni, E.; Serracca, L. Antiviral activity of essential oils against hepatitis A virus in soft fruits. Food Environ. Virol. 2019, 11, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saeb, S.; Amin, M.; Gooybari, R.S.; Aghe, N. Evaluation of antibacterial activities of Citrus limon, Citrus reticulata, and Citrus grandis against pathogenic bacteria. Int. J. Enteric Pathog. 2016, 4, e37103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Man, A.; Santacroce, L.; Jacob, R.; Mare, A.; Man, L. Antimicrobial activity of six essential oils against a group of human pathogens: A comparative study. Pathogens 2019, 8, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jing, L.; Lei, Z.; Li, L.; Xie, R.; Xi, W.; Guan, Y.; Sumner, L.W.; Zhou, Z. Antifungal activity of citrus essential oils: A review. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 3011–3033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajayi-Moses, O.B.; Ogidi, C.O.; Akinyele, B.J. Bioactivity of Citrus essential oils (CEOs) against microorganisms associated with spoilage of some fruits. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2019, 6, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dosoky, N.S.; Setzer, W.N. Biological activities and safety of Citrus spp. essential oils. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lin, C.M.; Sheu, S.R.; Hsu, S.C.; Tsai, Y.H. Determination of bactericidal efficacy of essential oil extracted from orange peel on the food contact surfaces. Food Control 2010, 21, 1710–1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourgou, S.; Zohra, F.; Ourghemmi, I.; Saidani, M. Changes of peel essential oil composition of four Tunisian citrus during fruit maturation. Sci. World J. 2012, 528593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Settani, L.; Palazzolo, E.; Guarrasi, V.; Aleo, A.; Mammina, C.; Moschetti, G.; Germaná, M. Inhibition of foodborne pathogen bacteria by essential oils extracted from citrus fruits cultivated in Sicily. Food Control 2012, 26, 326–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N.; Tripathi, A. Effects of Citrus sinensis (L.) Osbeck epicarp essential oil on growth and morphogenesis of Aspergillus niger (L.) Van Tieghem. Microbiol. Res. 2008, 163, 337–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viuda-Martos, M.; Ruiz-Navajas, Y.; Fernández-López, J.; Perez-Álvarez, J. Antifungal activity of lemon (Citrus limon L.), mandarin (Citrus reticulata L.), grapefruit (Citrus paradisi L.) and orange (Citrus sinensis L.) essential oils. Food Control 2008, 19, 1130–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Shukla, R.; Prakash, B.; Kumar, A.; Singh, S.; Mishra, P.K.; Dubey, N.K. Chemical profile, antifungal, antiaflatoxigenic and antioxidant activity of Citrus maxima Burm. and Citrus sinensis (L.) Osbeck essential oils and their cyclic monoterpene, dl-limonene. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2010, 48, 1734–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palazzolo, E.; Laudicina, V.A.; Germanà, M.A. Current and potential use of citrus essential oils. Curr. Org. Chem. 2013, 17, 3042–3049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolffenbüttel, A.N.; Zamboni, A.; Becker, G.; dos Santos, M.K.; Borille, B.T.; de Cássia Mariotti, K.; Fagundes, A.C.; de Oliveira Salomón, J.L.; Coelho, V.R.; Ruiz, L.V. Citrus essential oils inhalation by mice: Behavioral testing, GCMS plasma analysis, corticosterone, and melatonin levels evaluation. Phytother. Res. 2018, 32, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasek, O.M.; Cáceres, L.M.; Chamorro, E.R.; Velasco, G.A. Antibacterial activity of Citrus paradisi essential oil. J. Nat. Prod. 2015, 8, 16–26. [Google Scholar]

- Uysal, B.; Sozmen, F.; Aktas, O.; Oksal, B.S.; Kose, E.O. Essential oil composition and antibacterial activity of the grapefruit (Citrus paradisi L.) peel essential oils obtained by solvent-free microwave extraction: Comparison with hydrodistillation. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2011, 46, 1455–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, W.; Liu, K.; Cao, S.; Sun, J.; Zhong, B.; Chun, J. Chemical composition, antimicrobial, antioxidant, and antiproliferative properties of grapefruit essential oil prepared by molecular distillation. Molecules 2020, 25, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Denkova-Kostova, R.; Teneva, D.; Tomova, T.; Goranov, B.; Denkova, Z.; Shopska, V.; Slavchev, A.; Hristova-Ivanova, Y. Chemical composition, antioxidant and antimicrobial activity of essential oils from tangerine (Citrus reticulata L.), grapefruit (Citrus paradisi L.), lemon (Citrus lemon L.) and cinnamon (Cinnamomum zeylanicum Blume). Z. Naturforsch. 2021, 76, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luciardi, M.C.; Blázquez, M.A.; Alberto, M.R.; Cartagena, E.; Arena, M.E. Grapefruit essential oils inhibit quorum sensing of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Food Sci. Technol. Int. 2019, 26, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sienkiewicz, M.; Lysakowska, M.; Pastuszka, M.; Bienias, W.; Kowalczyk, E. The potential of use Basil and Rosemary essential oils as effective antibacterial agents. Molecules 2013, 18, 9334–9351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Burt, S. Essential oils: Their antibacterial properties and potential applications in foods—A review. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2004, 94, 223–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.I.; Anwar, F.; Chatha, S.A.S.; Jabbar, A.; Mahboob, S.; Nigam, P.S. Rosmarinus officinalis essential oil: Antiproliferative, antioxidant and antibacterial activities. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2010, 41, 1070–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baghloul, F.; Mansori, R.; Djahoudi, A. In vitro antifungal effect of Rosmarinus officinalis essential oil on Aspergillus niger. Natl. J. Physiol. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2017, 7, 285–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva Bomfim, N.; Kohiyama, C.Y.; Nakasugi, L.P.; Nerilo, S.B.; Mossini, S.A.G.; Romoli, J.C.Z.; Graton Mikcha, J.M.; Abreu Filho, B.A.; Machinski, M. Antifungal and antiaflatoxigenic activity of rosemary essential oil (Rosmarinus officinalis L.) against Aspergillus flavus. Food Addit. Contam. Part A Chem. Anal. Control Expo. Risk Assess. 2020, 37, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felšöciová, S.; Vukovic, N.; Jeżowski, P.; Kačániová, M. Antifungal activity of selected volatile essential oils against Penicillium sp. Open Life Sci. 2020, 15, 511–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto, G.; Ros, G.; Castillo, J. Antioxidant and antimicrobial properties of rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.): A review. Medicines 2018, 5, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jung, E.K. Chemical composition and antimicrobial activity of the essential oil of Chrysanthemum indicum against oral bacteria. J. Bacteriol. Virol. 2009, 39, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shunying, Z.; Yang, Y.; Huaidong, Y.; Yue, Y.; Guolin, Z. Chemical composition and antimicrobial activity of the essential oils of Chrysanthemum indicum. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2005, 96, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahrajabian, M.H.; Sun, W.; Zandi, P.; Cheng, Q. A review of chrysanthemum, the eastern queen in traditional chinese medicine with healing power in modern pharmaceutical sciences. Appl. Ecol. Environ. Res. 2019, 17, 13355–13369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodaei, M.; Rahimmalek, M.; Arzani, A. Variation in morphological characters, chemical composition, and anthocyanin content of different Chrysanthemum morifolium cultivars from Iran. Biochem. System. Ecol. 2017, 74, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boukhebti, H.; Demirtas, I.; Omar, L.; Chaker, A.N. Chemical composition, antibacterial activity of essential oil and anatomical study of Chrysanthemum morifolium. J. Drug Deliv. Ther. 2020, 10, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Jiang, Y.; Zhao, H.; Köllner, T.G.; Chen, S.; Chen, F.; Chen, F. Diverse terpenoids and their associated antifungal properties from roots of different cultivars of Chrysanthemum morifolium Ramat. Molecules 2020, 25, 2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.T.; Hsu, W.C.; Lin, C.C. Antiviral natural products and herbal medicines. J. Tradit. Complement. Med. 2014, 4, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Youssef, F.S.; Eid, S.Y.; Alshammari, E.; Ashour, M.L.; Wink, M.; El-Readi, M.Z. Chrysanthemum indicum and Chrysanthemum morifolium: Chemical composition of their essential oils and their potential use as natural preservatives with antimicrobial and antioxidant activities. Foods 2020, 9, 1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez, G.; Aznar, R. Evaluation of natural compounds of plant origin for inactivation of enteric viruses. Food Environ. Virol. 2015, 7, 183–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raut, J.S.; Karuppayil, S.M. A Status Review on the Medicinal Properties of Essential Oils. Ind. Crops Prod. 2014, 62, 250–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behl, T.; Rocchetti, G.; Chadha, S.; Zengin, G.; Bungau, S.; Kumar, A.; Mehta, V.; Uddin, M.S.; Khullar, G.; Setia, D.; et al. Phytochemicals from Plant Foods as Potential Source of Antiviral Agents: An Overview. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randazzo, W.; Falcó-Ferrando, I.; Aznar, R.; Sánchez, G. Effect of green tea extract on enteric viruses and its application as natural sanitizer. Food Microbiol. 2017, 66, 150–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, B.J.; Kwak, J.H.; Son, J.H.; Park, J.M.; Lee, J.Y.; Jo, C.; Byun, M.W. Biological and anti-microbial activity of irradiated green tea polyphenols. Food Chem. 2004, 88, 549–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadang, V.; Hettiarachchy, N.; Johnson, M.; Owens, C. Evaluation of antibacterial activity of whey protein isolate coating incorporated with nisin, grape seed extract, malic acid, and EDTA on a turkey frankfurter system. J. Food Sci. 2008, 73, 389–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, Y. Novel uses of catechins in foods. Trends Food Sci. 2006, 17, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcó, I.; Díaz-Reolid, A.; Randazzo, W.; Sánchez, G. Green tea extract assisted low-temperature pasteurization to inactivate enteric viruses in juices. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2020, 334, 108809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, P.J.; McIntosh, J.; Pearce, P.; Camden, B.; Jordan, B.R. Anthocyanin and antioxidant capacity in Roselle (Hibiscus sabdariffa L.) extract. Food Res. Int. 2002, 35, 351–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.S.; Wang, C.J.; Huang, C.N.; Chen, M.L.; Chen, M.J.; Peng, C.H. Polyphenols of Hibiscus sabdariffa improved diabetic nephropathy via attenuating renal epithelial mesenchymal transition. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013, 61, 7545–7551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKay, D.L.; Chen, C.Y.; Saltzman, E.; Blumberg, J.B. Hibiscus sabdariffa L. tea (tisane) lowers blood pressure in prehypertensive and mildly hypertensive adults. J. Nutr. 2010, 140, 298–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, K.S.; Tsao, S.M.; Yin, M.C. In vitro antibacterial activity of roselle calyx and protocatechuic acid. Phytother. Res. 2005, 19, 942–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, S.S.; Dice, L.; D’Souza, D.H. Aqueous Extracts of Hibiscus sabdariffa Calyces Decrease Hepatitis A Virus and Human Norovirus Surrogate Titers. Food Environ. Virol. 2015, 7, 366–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Shiekh, R.A.; Abdelmohsen, U.R.; Ashour, H.M.; Ashour, R.M. Novel Antiviral and Antibacterial Activities of Hibiscus schizopetalus. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joshi, S.S.; Howell, A.B.; D’Souza, D.H. Reduction of Enteric Viruses by Blueberry Juice and Blueberry Proanthocyanidins. Food Environ. Virol. 2016, 8, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Souza, D.H. Phytocompounds for the control of human enteric viruses. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2014, 4, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jayaprakasha, G.K.; Selvi, T.; Sakariah, K.K. Antibacterial and antioxidant activities of grape (Vitis vinifera) seed extracts. Food Res. Int. 2003, 36, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, S.S.; Su, X.; D’Souza, D.H. Antiviral effects of grape seed extract against feline calicivirus, murine norovirus, and hepatitis A virus in model food systems and under gastric conditions. Food Microbiol. 2015, 52, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X.; D’Souza, D.H. Grape seed extract for control of human enteric viruses. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 77, 3982–3987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fabra, M.J.; Castro-Mayorga, J.L.; Randazzo, W.; Lagarón, J.M.; López-Rubio, A.; Aznar, R.; Sánchez, G. Efficacy of cinnamaldehyde against enteric viruses and its activity after incorporation into biodegradable multilayer systems of interest in food packaging. Food Environ. Virol. 2016, 8, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, M.H.; Lee, B.H.; Jung, J.Y.; Cheon, D.S.; Kim, K.T.; Choi, C. Antiviral effect of korean red ginseng extract and ginsenosides on murine norovirus and feline calicivirus as surrogates for human norovirus. J. Ginseng Res. 2011, 35, 429–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, M.H.; Lee, B.H.; Lee, S.; Choi, C. Reduction of hepatitis A virus on FRhK-4 cells treated with Korean red ginseng extract and ginsenosides. J. Food Sci. 2013, 78, 1412–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.; Baert, L.; Uyttendaele, M. Inactivation of food-borne viruses using natural biochemical substances. Food Microbiol. 2013, 35, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamdy, A.H.; Mettwally, W.S.; El Fotouh, M.A.; Rodriguez, B.; El-Dewany, A.I.; El-Toumy, S.A.; Hussein, A.A. Bioactive phenolic compounds from the Egyptian Red Sea seagrass Thalassodendron ciliatum. Z. Nat. C 2012, 67, 291–296. [Google Scholar]

- Fiore, C.; Eisenhut, M.; Krausse, R.; Ragazzi, E.; Pellati, D.; Armanini, D.; Bielenberg, J. Antiviral effects of Glycyrrhiza species. Phytother. Res. 2008, 22, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).