Abstract

This article offers the first systematic analytical methodology to understand distant play as a multidimensional, ludoliterary, critical, and philosophical practice of engaging with so-called idle or semi-idle games. It uses Anselm Pyta’s The Longing, a so far underexplored semi-idle, slow game that challenges traditional gameplay paradigms through its metareferential, bookish, philosophical, and contemplative structure, as a case study. Our central argument is that The Longing deploys antimimetic temporal mechanics, interpassive forms of bookish play, and ideas of existentialist resistance to explore themes of time, agency, and existential longing, thereby offering a reflective space for dealing with neo-liberal, post-pandemic, polycrisis-stricken angst. To come to terms with the multidisciplinary complexities of the game, our paper adopts a triadic analytical methodology interweaving insights from postclassical, medium-specific narratology, platform-comparative literary analysis, and existentialist philosophy. This combined approach transcends existing ludoliterary frameworks and accounts for divergent forms of play. Our first focus is the game’s multiscalar temporal layering and the strategies it requires from players to “ludify” antimimetic frictions bookish between those layers. This is followed by an examination of how the game constructs a bookish player by interweaving ludexical processes of reading, unreading, dis-reading, and writing (in) books and other printed documents. Finally, we turn to the game’s complex interpassive relationships between player, player-character, and game world, highlighting in particular the role of walking, collecting, building, and searching as acts of catharsis and rebellion, and examining failure as a valid ludic alternative to survival and happiness. Ultimately, our analysis renders distant play as a form of parasocial resistance, which in The Longing manifests as an affective and philosophically fine-grained combination of more-than-human relationality, care, and relief vis-a-vis the nothingness of lost hope. The game thus offers a new form of e-literary engagement, placing books and their “unnatural,” transmediated affordances front and center while questioning the capitalist undercurrents of contemporary literary media and critiquing a culture of acceleration.

1. Introduction

This article offers the first systematic analytical methodology to understand distant play (Fizek 2022) as a multidimensional, ludoliterary, critical, and philosophical practice of engaging with so-called idle or semi-idle games, which are a sub-genre of metaludic indie games (Ensslin 2014; Aksay et al. 2025). It uses Anselm Pyta’s The Longing (Studio Seufz 2020), a so far underexplored semi-idle, slow game that challenges traditional gameplay paradigms through its metareferential, bookish, philosophical, and contemplative structure, as a case study. Our central argument is that The Longing deploys antimimetic temporal mechanics, interpassive forms of bookish play (Aksay et al. 2024), and ideas of existentialist resistance to explore themes of time, agency, and existential longing, thereby offering a reflective space for dealing with neo-liberal, post-pandemic, polycrisis-stricken angst.

Released exclusively for PC during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, and later expanded to other platforms, including mobile devices, the game’s reception emerged within a temporality defined by isolation, interruption, and indeterminacy. Within this climate, reviews and early academic responses framed the game in terms of its somber, introspective, and reflective style (Bell 2020; Gordon 2020; Navarro-Remesal 2026). This reception context informs the game’s remediation of the Kyffhäuser myth (or “the king in the mountain” trope), generally understood as an allegory on collective hope for renewal and liberation from a time of uncertainty and suffering. This liberation, often framed in sacral terms, is expected to come when the slumbering king or emperor (Barbarossa, according to German legend) awakens and restores the lost equilibrium of “national unity and greatness” (Niven 2010, p. 401), for which reason the myth has lent itself conveniently to narratives of right-wing radicalism. Detached from any particular political symbolism, “longing” for liberation and freedom becomes the main raison d’être in the thus entitled game. It bridges the “deep time” (in the sense of a multilayered, multiscalar notion blending subjective and objective time, see Mazzola et al. 2021) of waiting in subjectively meaningful ways, thus evoking existentialist philosophical reflection (Csaba 2021).

In the game, the player-controlled humanoid “Shade”1 is tasked with waiting in a vast system of underground caves, in complete solitude, for 400 real-time days until the king awakens. This countdown is displayed constantly at the top of the screen and continues to progress even when the game is not running. By transforming waiting into a central mechanic, The Longing places players at literal and metaphorical crossroads between action and inaction, engagement and detachment, compliance and defiance. This dilemma is complicated by different layers of realistic and non-realistic spatio-temporal design as well as a range of everyday collectibles that assume diverse quantitative and qualitative values. The most evocative amongst them are elements of bookish culture that dominate the make-up of the gameworld and significantly impact the player’s character and the player’s experience of dwelling in the caves.

To come to terms with the multidisciplinary complexities of the game, our paper adopts a triadic analytical methodology interweaving insights from postclassical, medium-specific narratology, platform-comparative literary analysis, and existentialist philosophy. This combined approach transcends existing ludoliterary frameworks (Ensslin 2014; Richter et al. 2024) and accounts for diverse scholarly experiences. Our first focus is the game’s multiscalar temporal layering and the strategies it requires from players to “ludify” antimimetic frictions between those layers (see Ensslin and Bell 2021; Alvarez Igarzábal 2019). This is followed by an examination of how the game constructs a bookish player by interweaving ludexical processes of reading, unreading, dis-reading, and writing (in) books and other printed documents (see Aksay et al. 2024, 2025; Pressman 2020; Milligan 2019).2 Finally, we turn to the game’s complex interpassive relationships between player, player-character, and game world (Fizek 2022), highlighting in particular the role of walking, collecting, building, and searching as acts of catharsis and rebellion, and examining failure as a valid ludic alternative to survival and happiness. Ultimately, our analysis renders distant play as a form of parasocial resistance, which in The Longing manifests as an affective and philosophically fine-grained combination of more-than-human relationality, care, and relief vis-à-vis the nothingness of lost hope. The game thus offers a new form of e-literary engagement, placing books and their “unnatural”, transmediated affordances front and center while questioning the capitalist undercurrents of contemporary literary media and critiquing a culture of acceleration.

2. Distant Play

In her 2022 monograph, Playing at a Distance: Borderlands of Video Game Aesthetic, Sonia Fizek introduces the concept of distant play as an aesthetic effect of playing so-called (semi-)idle games, a quasi-ludic genre that encompasses media also known as incremental, passive, self-playing, and clicker games. Idle games like Progress Quest (2002), Cow Clicker (2010), Progress Wars (2010), Godville (2010), Cookie Clicker (2013), and A Dark Room (2013) satirize existing game genres by automating their key mechanics, which players have identified as monotonous, tedious, or unnecessarily laborious. Cow Clicker (2010), for example, is a parodical response to massively capitalized, casual browser games like Facebook’s FarmVille (2009), which reduce player action to a mere few clicks each time they visit their interface, essentially doing nothing but planting and harvesting crops. In this way, Cow Clicker “distil[s] the social game genre down to its essence,” accentuating the mindlessness of the target genre’s design (Bogost 2010).

Idle games (Pecorella 2015), the broader category within which we situate The Longing, unfold incrementally. They require and afford minimal player interaction and appear more or less automated. This oftentimes humorous exaggeration of machine autonomy and resultant player passivity is inspired not only by the monotony of clicker games like Farmville, but also by the repetitive mechanics of grinding, gold farming, and leveling up in stereotypical role-playing games (Nardi and Ming Kow 2010).

Fizek (2022) frames idle games as objects of posthuman play, in which players delegate maximum if not near-total agency to the game engine, reducing, as a result, player agency. This leads to a decentering of the human player, leading to effects of emersion (rather than immersion), i.e., to players developing a self-conscious or self-critical stance vis-à-vis their own expectations and habits of gameplay (see also Ensslin and Bell 2024). According to Fizek (2022, p. 22), the way in which idle games externalize gameplay emersively can be read as a response to or a critique of fast-paced, technopatriarchal, neoliberal game culture: the attention economy is subverted through extended periods of absence on the player’s part; the urge for or obsession with continual gratification is subverted by zero-effort rewards, calling into question the very notion of positive reinforcement as addictive glue; distant play with its ultra-slow progress and navigation counteracts compulsive media interaction and the urge to regularly check status updates; and it critiques—in good old Marxist fashion—the drudgery inherent in automated combat as well as the loss of and detachment to the products of real (p)laybour (Kücklich 2005).

Fizek analyzes idle games through the theoretical lens of interpassivity (introduced by Robert Pfaller (1996) and later expanded by Slavoj Žižek (1997)). In psychoanalytic theory, interpassivity is a condition where the subject’s activity is displaced onto another agent, animate or inanimate. An example of interpassivity in contemporary media is the canned laughter known from sitcoms, which is used as a substitute for real audience laughter. Canned laughter motivates a form of perverse pleasure in the viewer to laugh along and satisfies them interpassively, even when they do not participate actively in the remote laughter. The concept of delegating action to another mediated instance or media object becomes particularly relevant when examining idle games’ relationship to contemporary algorithmic game culture. Fizek notes that idling as a form of delegated machine action “leads to a momentary escape from the responsibility of active play and, as a result, a disidentification with the player’s primary role as an active agent” (Fizek 2018, p. 142). This disidentification functions as both refuge and critique, allowing players to adopt an existentialist stance interrogating the rationale of their play.

3. The Longing

The Longing places players in control of the Shade, a small, solitary, melancholic, cave-dwelling creature (who we read as a-gendered and for whom we therefore use the pronoun “they/them”), tasked with awakening a nameless slumbering king, after a waiting period of 400 real-time days. The game spaces Shade is ostensibly trapped within during this period are dark, empty, and lonely caves that offer no conventional gameplay challenges; there are, for example, no monsters to fight, no moving platforms to jump between, and no quests to accomplish. The ultra-extended countdown, as mentioned in the introduction, is always visible on the game screen and progresses even when the game is not running. In its most minimal form, completing the game requires only that players initiate a save file, wait for over a year, and return to witness the conclusion (Figure 1). As such, The Longing radically subverts conventional expectations of active gameplay and instant gratification.

Figure 1.

Screenshot of the Shade, protected by the risen king; “Awaken the King” ending (courtesy of AE).

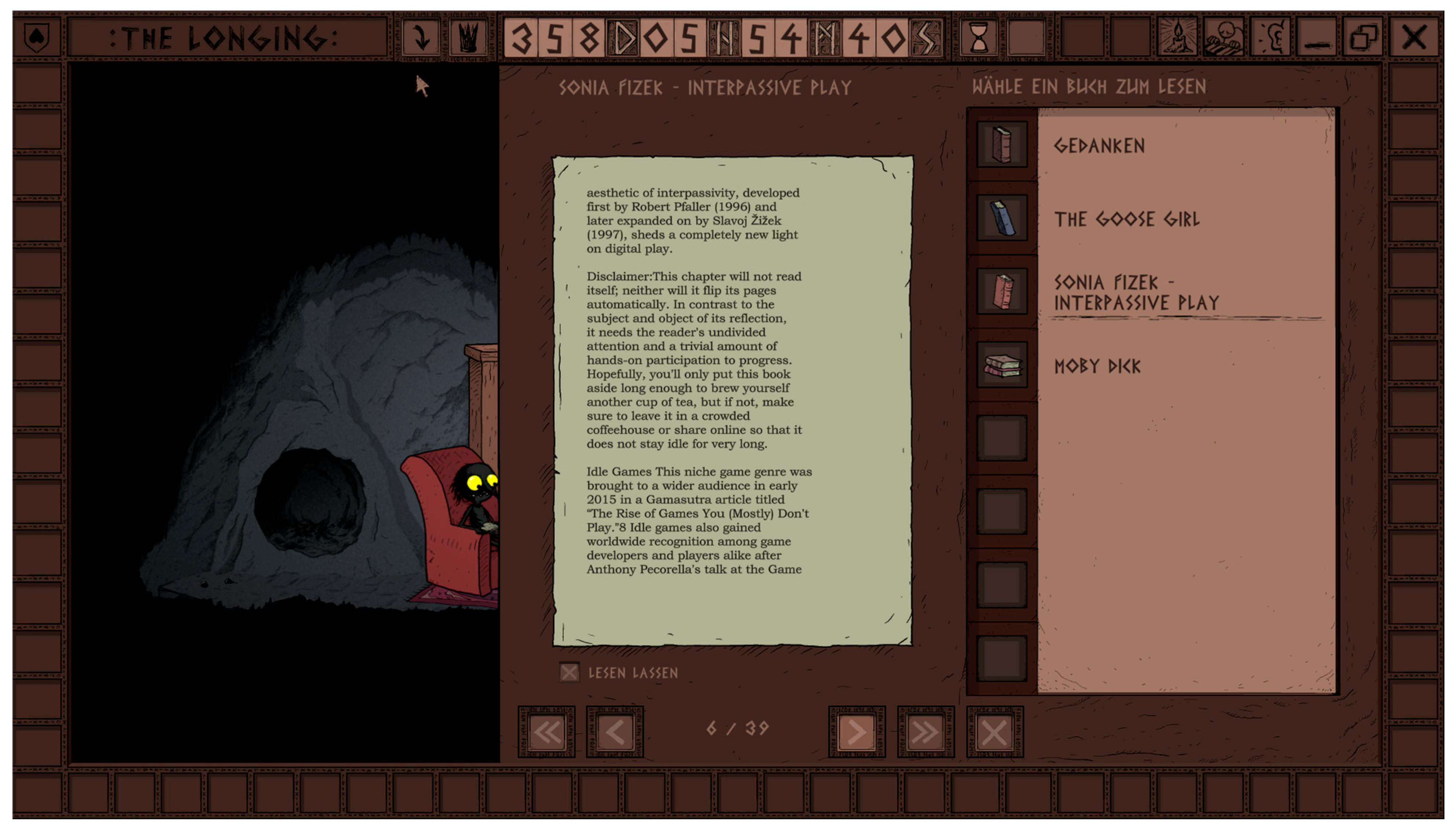

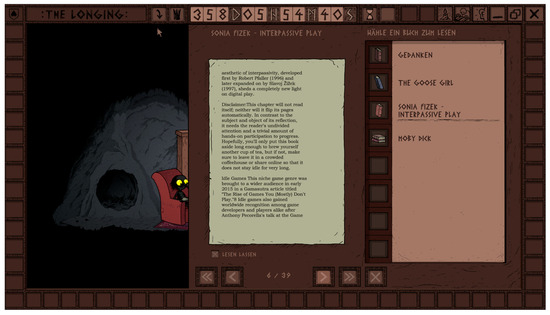

However, The Longing invites, and in many ways rewards, a more involved form of engagement than simply waiting for the 400 real-time days to pass. Throughout the game, players may explore a vast network of caverns that are revealed to hold secrets, read public domain texts (such as Moby-Dick (Melville [1851] 1997) and the four volumes of Friedrich Nietzsche’s (1883) Thus Spoke Zarathustra), gather resources to craft decorative items, and decorate the Shade’s living space with them (Figure 2). Many actions, including puzzles and exploration, utilize the passage of time as an obstacle. For example, opening a door may require waiting for two hours until it is unstuck, and a mushroom might need ten hours to grow before being big enough to be jumped on, thus enabling access to a higher ledge. The only exceptions to waiting and wandering are pleasurable or creative activities—such as playing music, drawing, or reading—which accelerate in-game time, subtly echoing the idea that “time flies when you’re having fun”, as the Shade tells us in one of their interior monologues. This intermittent misalignment between diegetic and non-diegetic time can make slow, time-dependent challenges, such as opening a heavy door or waiting for a pond to fill, progress much more quickly. The mechanics of time manipulation through these activities thus introduce both strategic depth and emotional resonance, positioning joy itself as a temporal agent in the game.

Figure 2.

Screenshot of the Shade’s home and a readable collection of books in The Longing (courtesy of KA).

Whether or not the player engages in these time-accelerating activities to gain a degree of control over both the game’s mazes of caves and the passage of its diegetic time also affects the multiple endings of the game they can reach. Specifically, the game offers five possible conclusions. The first and most straightforward ending involves awakening the king, which completes what the game prepares the player to wait for at the outset. Yet this is not the most rewarding ending, as upon awakening, the king is enraged and destroys the caves and all within them, sparing only the Shade and himself, who continue to rule the emptied “world without longing”.

All other endings require the player to subvert the game’s spatiotemporal obstacles in some way. In two endings, the Shade can escape the caves through secret paths leading outside before the 400 days are over. Their escape is only possible by reaching the surface via a well located near the uppermost cave levels, which requires completing several time-manipulation puzzles. Once the Shade enters the well, the outcome depends on player timing: the Shade may be rescued by an outsider or killed, leading to two different endings. In both cases, the game screen declares that “the longing has been ended.”

A fourth and more challenging ending allows the Shade to open a portal into a “wonderland,” resulting in a dreamlike sequence marked by the on-screen text, “the longing has ended.” Finally, the game includes a “suicide ending,” in which the player intentionally causes the Shade to jump from a cliff within the caves. Again, this refers to the end of the game and the Shade’s longing, accompanied by the feedback, “The longing has been wilfully ended”. As with all endings, this ending requires a deliberate choice rather than an accidental death; players are prompted to confirm their intention to conclude the game through this particular outcome. In all its routes, The Longing challenges the player not only to rethink the nature of gameplay but also to reflect on solitude, purpose, and the phenomenology of waiting. Therefore, we argue that the game is less about what one does than how one endures—or resists—the slow, inescapable march of time. The repeated invocation of “the longing has ended” across the game’s multiple ending sequences suggests a subversive way to play the game that diverges from the game’s prescribed path of waiting.

4. Analyzing Distant Play in The Longing: A Trialogic Approach

In this section, we will be introducing three different yet intersecting approaches to distant play-reading The Longing that we argue are needed to come to terms with the game’s ludological, aesthetic, and philosophical complexities. To showcase the interwovenness of these three approaches, we stage an imaginary yet academically authentic (in the sense of sincere and intentional), scholarly trialogue between three alter egos of ourselves. They each represent, in distributed parts, concepts and tools from medium-specific “unnatural” narratology (see Ensslin and Bell 2021), platform-comparative literary analysis of bookish play (see Aksay et al. 2024, 2025), and philosophical reflection and rebellion. To reflect the theoretical core of our approach (interpassive play) on a formal-logistical level, we developed the trialogue through several co-creative human-GenAI iterations, with initial assistance from Claude Sonnet 4. To begin with, we first hand-drafted a full-fledged scholarly analysis, distributed between the three human co-authors, following a conventional, three-pronged approach, with consecutive sections titled “Medium-Specific, Unnatural (Ludo-)Narratology”, “Ludexical Play”, and “Existential Waiting and Player Interpassivity”. These three subsections were uploaded to Claude with the following prompt:

Please turn Section 4 of the uploaded document into a scholarly dialogue between three academics. Hume’s “Dialogues about Natural Religion” could be a nice blueprint for the conversation. Frame the trialogue as a conversation between three academic scholars: a ludoliterary scholar (called Kübra), an existential media philosopher (Sebastian), and an unnatural narratologist (Astrid) who are discussing their individual approaches (distant playing analysis) to the videogame The Longing by Studio Seufz. Please leave sections 1 to 3 as they are. The word count of the trialogue should be about 2000 words. Each turn should be a maximum of 150 words.

We chose David Hume’s “Dialogues” (1779) as a template for several reasons: it is an important Enlightenment text that symptomizes a paradigm shift of similar gravity as our currently evolving age of AI. The text deals with Enlightenment uncertainty about the existence and nature of God, thus resonating with the core message of the game that the sleeping messianic savior king ultimately fails to provide the desired redemption and that there are other possible resolutions to the protagonist’s captivity. On a formal level, “Dialogues” is a rare example of a philosophical trialogue in the sense of three non-hierarchically orchestrated voices (Demea, Philo and Cleanthes). The trialogue is narrated by Pamphilus, a student of Cleanthes’, who assumes an ancillary, quasi-mediating role between the three speakers, comparable to the synthetic narratorial voice generated by Claude in our approach.

The task given to the chatbot was not to construct an argument from scratch but rather to adapt the genre to an imaginary dramatization of our ideas as a form of co-creative practice that might allow readers to conceptualize the three approaches as an entangled whole. The prompt generated an entertainingly written yet occasionally less-than-accurate (simplifying and/or hallucinating) dramatic dialogue impersonating our scholarly approaches, which then formed the basis of further manual rewrites and elaborations. We needed to ensure that our individual arguments were represented accurately while also responding to one another in meaningful, cooperative, conversationally appropriate, and thematically relevant ways (see Grice 1975). Whilst we ended up editing all our conversational turns (conceptually and formally, to make for a better flow of conversational turns), the prologue and epilogue stayed essentially as narrated by the chatbot. Together, our individual turns, as displayed in the following section “On Distant Play”, interlace into a multilayered analytical approach that we consider conducive to comprehending the complexity of a literary-philosophical idler like The Longing, thus setting the scene for future ludoliterary design and analysis. The change in tone reflects the conversational intent behind our approach. The trialogue is set in an autofictional world that is narrativized in the italicized prologue so as to emulate the reality of the historical authors whilst also representing a prompted and therefore fictional construct of the chatbot.

On Distant Play

In a quiet university seminar room, three scholars convene to discuss their research on Studio Seufz’s enigmatic game, The Longing. Astrid, a specialist in unnatural narratology, spreads out notes on temporal mechanics derived from her previous work on Digital Fiction and the Unnatural (Ensslin and Bell 2021). Kübra, whose work focuses on ludoliterary and intermedial analysis of games (see, e.g., Aksay 2025; Aksay and Bachmann 2024; Aksay et al. 2024, 2025), has brought notes on (and screenshots of) the game’s remediation of canonical texts and engagement with the acts of reading and writing. Sebastian, approaching from existentialist media philosophy (e.g., Richter 2025; Aksay et al. 2025; Richter 2022), contemplates the phenomenological implications of idle play. Their conversation unfolds over an afternoon, each bringing their distinct analytical lens to bear on this peculiar artifact of distant play.

Astrid: I find myself returning to the question of how The Longing fundamentally challenges our understanding of narrative time. The game presents us with what I’d call unnatural or, more specifically, antimimetic temporalities—mechanics that violate not only our real-world cognitive frames but also established video game conventions (see Ensslin and Bell 2021). Don’t get me wrong: unnatural in the sense of non-mimetic temporality in itself is nothing new or idiosyncratic to The Longing. We know it from temporal mechanics like bullet time in Max Payne or from rewind-and-undo scenes in Life Is Strange. However, unnatural time can also be designed so as to alienate players and protect them from the illusion of being in a controllable fictional world (Ensslin and Bell 2024).

I’d argue that The Longing follows such an antimimetic trajectory, and that there are essentially five temporal layers at work that are jointly conducive to this effect. First, there is play time, which is the chronometric time the player spends actually playing the game (Juul 2004). Play time in this game partially overlaps with event time, which is the time spent in the game world (Juul 2004). In The Longing, play time and event time overlap whenever the in-game clock conflates with the player’s chronometric time. These overlaps happen whenever the Shade wanders through the caves, which we may refer to as vagary time. Conversely, during episodes of domestic time, the Shade is at home following diverse activities like playing an instrument, drawing a picture, reading a book, or lighting a fire. These activities differentially speed up or even reverse time (in the case of blue fire, for which the Shade needs to have collected two pieces of flint and five lapis lazuli stones). On a more cognitive level, we may additionally single out a fifth layer, metaleptic time, which refers to the time spent by players thinking and talking about how best to integrate (slow) play time in interpassive daily routines, online and off. What happens here isn’t a mere naturalization of the unnatural, as Jan Alber (2016) would suggest, but something more complex: a form of operational adaptation to antimimetic constraints, a ludification of unnatural temporality in the sense of internalizing and optimizing temporal constraints for the purposes of ludic entertainment.

Kübra: That’s fascinating, Astrid, and it connects beautifully to how the game literalizes the relationship between physical action and cognitive attention through its bookish mechanics. When the Shade reads in the game—whether it is Moby-Dick, Thus Spoke Zarathustra, or their own diary—the game accelerates time based on page-turning, not comprehension. In effect, players must choose whether to align their cognition with the Shade’s experience to read the texts in the game in the conventional sense or use in-game reading strategically while attending to something else entirely. To be more specific, the game offers two modes of simulated reading: firstly, what the game calls “idle reading,” which automatically turns one page per real-time minute, and secondly, manual page-turning, which advances the in-game time one minute for each page turned (i.e., clicked). The second mode thus incentivizes not reading by encouraging players to skim or spam-click to strategically advance the in-game time. Aligning this second mode with Sonia Fizek’s notion of “dis-play” as a distanced, spectatorial relation to play, we can describe it as dis-reading, a mode that distances the player from attentive reading by instrumentalizing page-turning as strategic input (Fizek 2022, p. 130). In addition to these two modes of reading, the books in The Longing can also be “unread” as the game includes a reverse reading mechanic during the blue-fire sequence, where time runs backward, as you mentioned, and pages are marked as unread either through idle reading or page turning. What is striking here is that all types of engagement with the book can be considered a unique type of distant play, whether it is by allowing the book to read itself, just as idle games play themselves, by dis-reading, or by unreading. Each mode subverts the act of reading in a unique way and delegates the engagement with the intradiegetic text to the player character.

Sebastian: When I listen to you, I can’t help noticing that you both touch on something I see as fundamentally existentialist in nature. In game studies, there are some references to existential play (see Leino and Möring 2025; Gualeni and Vella 2020; Vella 2019), which is connected to Heidegger’s concept of Sein-zum-Tode—being-toward-death (see Heidegger [1927] 1962). I would argue that the game creates an encounter with this concept. It means that after death, no decision is possible anymore. In analogy, each decision means letting go of all other decisions. So, in deciding to make the Shade jump into the abyss, players decide to end their existence towards death. Furthermore, the absence of save points means that player choices carry irreversible weight as the paths taken cannot be undone without a complete restart. Against this backdrop, the Shade’s expressions of anxiety (“I am afraid of the dark,” “I feel the end is coming”) echo Heidegger’s concept of Angst as the mood revealing existence’s contingency. Due to the finality of death, Heidegger interprets Angst as a basic state of existence. On the one hand, it is a confrontation with nothingness; on the other, it is important for exploring the world. It is in freedom that one can develop oneself, but this possibility is also a challenge. That is the reason why Heidegger distinguishes between Furcht (fear), which is connected to specific objects in the external world, and Angst (anxiety), which is based on the potential of human existence.

What this aspect of the game also reminds me of is Plato’s Cave Allegory, which has been extensively analyzed in media studies contexts (see, e.g., Baudrillard 1981; Bolter and Grusin 1999). Players inhabit a cave-like environment. This scenario directly parallels Plato’s prisoners, whose reality is constrained by their spatial and temporal limitations. But unlike Plato’s allegory, The Longing emphasizes escape toward enlightenment and presents waiting as both imprisonment and potential liberation. This connects to what Pfaller and Žižek term “interpassivity”—the displacement of activity onto another agent. Players delegate their agency to the Shade, creating what Fizek (2022) identifies as a disidentification from the active player role. Yet the player isn’t merely passive. Rather, the game invites critical engagement with the popular assumption that there is a straightforward dichotomy between active and passive media consumption (Pérez-Latre 2026). It offers players multiple philosophical stances: accepting passivity in the sense of non-kinetic interaction by simply waiting; engaging in environmental modification through collecting and decorating; exploring rebellion through alternative endings, or choosing termination through the Shade’s death. All possibilities are a form of Sein-Zum-Tode, and you can choose only one. In this case, Angst is experienced interpassively. Although there is no ‘real’ anxiety as the game is simulated, it is a familiar existential state for the players, filtered through the avatar.

Astrid: Sebastian, I think your point about interpassivity is crucial, but I’d add that the temporal mechanics complicate agentic delegation in unique ways because players begin to care and engage far beyond the way they do in a classical idler. The Tamagotchi effect (Fizek 2022) you’re alluding to—where the Shade becomes a kind of imaginary cohabitant, almost like a family member of sorts, that needs caring and nurturing—emerges precisely because of these unnatural temporal layers. The Tamagotchi effect depends on the intensity of the player’s commitment to the game and its protagonist and can take a symbolically embodied form. For instance, players may identify with the Shade to such an extent that they decide to obtain an actual physical proxy of it (“Shade Plushie”), of which a limited number of 400 were temporarily available for sale in 2023 (Pyta 2023). Alternatively, when players report on the Steam wiki that they’re “in unconditional love with the little guy!” or that, “[w]henever I exit the game I try to make sure they are holed up nice and comfy at their home, preferably with the fire going” (Ashgames 2020), we can see how differential time mechanics alter lived temporality. What happens as a result of interpassive, metaleptic interlacing is a form of parasocial engagement between player and player-character that blends both ontological spheres (Bell and Alber 2012) and leads to bleed effects like ontological resonance, which Bell defines as aesthetic “play with the boundary between reality and fiction … that lead […]players to perceive bidirectional ontological transfers both during and after the narrative experience” (Bell 2021, p. 430). In other words, the game doesn’t just externalize play to the machine; it creates an imagined space that allows diegetic time to infiltrate everyday life. This temporal design transforms the Shade from a mere avatar into what feels like a persistent, parasocial companion whose rhythms and needs we as players learn to respect.

Kübra: Yes, and this is where the literary elements become particularly significant. The ludexical elements in the game are not just thematic decoration; they are procedural devices mediating this exact relationship between passivity and agency that you are both describing. When players unlock the Neverending Notebook after collecting twenty-five books within the game, they can add their own texts to the game through its file directory. These player-added pages function identically to the canonical texts, advancing time when read (or unread). As such, the Neverending Notebook can be considered a reward for the bibliophile player who managed to collect enough books and can now accelerate time without ever looking for another book.

However, the process of writing does not occur within the book interface or the game itself; instead, the player must locate the .txt file in the game’s folder on their computer and edit the file to integrate new text in the game. This interaction stresses once again that it’s not the player character who is writing these lines, but rather, the player. When the Shade can read these player-integrated texts, the character, of course, cannot react to them in a unique way. To put it another way, even as the player takes the role of the writer, and performs the role of the reader through the Shade, the relationship between the player and the player character remains non-mutual. Thus, the player-created content of the Neverending Notebook produces a form of metaleptic, or parasocial, as you call it, Astrid, communication between the player and the character. Along with this, writing in the game also has a metareferential dimension. In addition to the player adding new books to the game, the Shade also updates the game’s intradiegetic texts, either by updating their diary (titled Thoughts, which can be read just as the other books in the game) or by adding notes within other books, which by the way become visible to other players as well depending on where they are in the cave system and how much progress they have made.

Interestingly, also, the canonical texts on the in-game shelf often contain clues to alternate endings through the notes the Shade scribbled in their margins. This way, the game both self-reflexively comments on its own subversive modes of play and creates the impression that the character is engaging in some kind of analeptic dialogue with the player. Needless to say, scholarly texts can be brought into the game as well, adding a metareferential perspective. In Figure 3, you can see embedded parts of Fizek’s book (cc by-nc-nd 4.0) in the game and how with this re-positioning of the book, the disclaimer on self-reading she makes (Fizek 2022, pp. 17–18) becomes semiotically entangled with the bookishness of the game.

Figure 3.

Screenshot depicting a section of Playing at a Distance (Fizek 2022) integrated in The Longing’s virtual bookshelf (courtesy of SR).

Sebastian: Nice! This also shows that the game creates genuine liminal space—what Victor Turner (1969) would recognize as an environment where traditional structures of meaning can be questioned and transformed. Unlike Beckett’s (1953) Waiting for Godot, where waiting becomes a pure absurdity, The Longing offers the possibility of rebellion through exploration and modification. But here’s what strikes me as most significant: the emotional catharsis we undergo as players operates differently than in other idle games because of the existential stakes I mentioned earlier. And that makes the Tamagochi Effect so intriguing, Astrid. While players face no real consequences, the Shade’s vulnerability creates conditions for what Aristotle in his Poetics (Aristotle 1996) would recognize as tragic catharsis—pity and fear leading to emotional purification. Of course, a Tamagotchi only has one life, too. However, I would argue that the relationship is different. The relationship between a player and their Tamagotchi involves taking care not to let the avatar die (Möring 2019). In the case of The Longing, conversely, player imbues the avatar with an alternative meaning, a resistant stance, prompting them to take action against the meaning imposed on them by the king. So, while the player has a choice to give the avatar a new intentional meaning, they also experience the struggles and anxieties the Shades is exposed to as a result of their choices. According to existential psychoanalysis, meaningful activities are important for dealing with existential stress and anxiety (Yalom 1980). Therefore, the relationship between the player and their avatar is less one of concern and more one of cooperative meaning-making.

Astrid: Yes, it puts player and player-character in a productive dialogue about the Shade’s ultimate raison d’être. Linking back to narratological considerations, the existentialist undertones, i.e., that irreversibility you mention, could also be considered yet another unnatural temporal mechanic that forces players to confront finitude in ways that most digital narratives carefully avoid. Decisions carry forward through real time, mimicking how lived experience actually unfolds. This connects to your earlier point about Sein-zum-Tode, but also to how the game’s multiple temporal layers create different degrees of presence and absence. When players engage in metaleptic compensation strategies—doing housework, toggling to other apps on their computer, or sleeping while a mushroom grows in the caves—they’re not escaping the game but extending it into their lifeworld. Therefore, while the game’s idling mode prima facie externalizes play and delegates in-game action to the machine, it also engenders a process of internalization, in which relational bonds form and develop. These parasocial bonds represent a form of resistance to the urge to give in to “the culture of speed” (Tomlinson 2007; Rosa 2010) surrounding us, allowing players to slow down and reflect on the dictates of acceleration and deep time.

Kübra: You know, actually, this notion of parasocial resistance beautifully captures something I have been trying to articulate about distant play. The Shade’s marginal notes in books suggest a reading subject independent of player attention, creating what feels like genuine intersubjectivity. In other words, their annotations imply that reading continues even without the player’s direct involvement, positioning the Shade as an autonomous subject rather than a mere extension of the player. On the one hand, players are made to feel responsible for the Shade’s well-being and their loneliness. For instance, in her review of the game for Rock Paper Shotgun, deputy editor Alice Bell3 admits, “I’m not so much scared for myself, though, as I am scared of what might happen to the little soot creature in my guardianship” and refers to the game as a “sad tamagotchi” (2020). Bell’s comment shows that the relationship between the player and the character extends beyond typical player–avatar dynamics of role assumption or control. Instead, (as in Bell’s case) it might be structured around care, vulnerability, or responsibility. Based on my interpretation, this relationship is shaped by the game’s temporal mechanics, which create a shared duration of waiting through the alignment of diegetic and non-diegetic time. In-game reading further reinforces this bond by establishing a shared activity between the player and the Shade that sustains their co-presence across the digital threshold.

Sebastian: What you and Astrid are describing, Kübra, sounds like a critical nod to the commodification of attention that characterizes so much contemporary digital culture. Practices of resistance in The Longing criticize the attention economy through extended periods of deliberate absence, and yet paradoxically create a deeper investment through that very absence. This is connected to what Galloway (2006) identifies as “waiting” as a form of resistance to ideologies of constant productivity. It could also be interpreted as a form of resonance practice. According to Rosa (2019), this is a form of counterculture to the acceleration of a “culture of speed”. He suggests that resonance crises are not characterized by pure alienation (for example to a capitalistic logic, which alienates the connection between work or crafting and the meaning of this work) but rather by the linear progression of social acceleration, which fails to provide multifaceted perspectives on life’s meaning. The Longing goes further than simply suggesting a counterpoint to social acceleration—it makes waiting collaborative. The Shade can question the meaning of a life only based on waiting and continues to exist, growing mushrooms and aging while we’re away. This persistence creates genuine temporal intimacy. Players aren’t just consuming content; they’re participating in a shared duration that acknowledges the reality of time’s passage beyond shared decisions.

Astrid: I’m struck by how you both have used the phrase “shared duration”. It points to something unique about how The Longing handles what narratologists call “story time” versus “discourse time.” Most games collapse this distinction through player control over pacing, but The Longing introduces an additional temporal dimension—what we might call “existential time” or time as lived, durational experience (e.g., Wiemer 2014). The game’s temporal design makes this existential temporality operationally relevant while maintaining its phenomenological weight. Players can’t skip past the waiting, can’t reload to undo time’s passage, can’t accelerate beyond the constraints of the mechanics. Yet within these constraints, they may discover remarkable agency in how they inhabit duration.

Kübra: The literary dimension adds another layer to this temporal complexity. The public domain texts are not random—Moby-Dick, Thus Spoke Zarathustra—these are works explicitly concerned with quests, waiting, and existential searching. But they’re also long books that take significant real-world time to read, even within the game’s accelerated reading mechanics. This creates what I see as a mise en abyme effect: the Shade reads about long journeys and philosophical quests while engaged in their own extended waiting. Players who choose to read alongside the Shade enter into triple temporality—their own lived time, the game’s various temporal layers that you pointed out earlier, Astrid, and the narrative time of these canonical texts, or rather of the worlds they invoke. It is a uniquely literary form of temporal layering.

Just to add to my earlier comment on player-added books, further books can also be integrated to replace existing books, using the game’s “Book Converter” extension. The Book Converter creates a workshop item, which can be downloaded and installed like a mod. The player-inserted book replaces another book from the available selection; in our example, the replaced book was the first part of Thus Spoke Zarathustra. Examined in this context, players can disrupt the game’s metareferential frame through the replacement of its readable books with substantially different ones, either in length or in theme.

Sebastian: To be honest, that’s what piqued my philosophical interest in the game from the outset. The philosophical resonance of Pyta’s ludexical choices and the fact that the game allows further texts to be integrated is deliberate, Kübra. Thus Spoke Zarathustra explicitly grapples with eternal recurrence and the revaluation of values—themes that connect directly to the game’s multiple endings and the question of whether waiting or rebellion constitutes authentic existence. Moby-Dick explores obsession, searching, and the relationship between human will and cosmic forces. I would also interpret it as an early criticism of capitalism. Driven by pride and hubris, Ahab destroys himself and his entire crew by being responsible for the sinking of the ship. Similarly, after the waiting process, the King in The Longing destroys the whole world and only he and the Shade survive. These aren’t just time-passing mechanics but philosophical provocations embedded in the game’s temporal structure. The Shade encounters these texts during their own existential crisis, creating what I’d call “hermeneutic resonance” between textual interpretation and ludic experience.

Astrid: So we’re here facing yet another new facet of what contemporary literary gaming might look like, which we already explored in an earlier multiperspectival exchange at the Electronic Literature Conference 2024 (Richter et al. 2024). As well, what emerges from our discussion is a picture of The Longing as implementing a form of philosophical game mechanics—it introduces a system that makes abstract concepts like temporality, agency, and companionship operationally relevant to play experience. The unnatural temporal layers invite extensive reflection on time itself and its ludonarrative affordances. The bookish mechanics don’t just add literary content; they explore the relationship between reading, waiting, and meaning-making. The interpassive elements don’t just automate play; they invite us to investigate what it means to care for another consciousness across time and ontological space.

Kübra: Yes, and I’d add that the game’s treatment of dis-reading and unreading connects to broader questions about how literary gaming might resist the above-mentioned default mode of contemporary attention. The Shade’s aversion to rereading, marked by the tracking system that only counts first readings, suggests something about the phenomenology of repetition and familiarity. Yet the blue-fire unreading mechanic offers recursive temporality where players can literally undo their reading history. This creates possibilities for what we might refer to as “temporal editing” of experience in which memory and familiarity can be actively undone. Unlike save files or other extradiegetic mechanisms of temporal control in other games, unreading here is performed within the fiction itself and requires deliberate effort, which includes an advanced familiarity with the game’s environment and the accumulation of required resources for the blue fire.

Sebastian: This makes sense, and particularly so in a culture that commodifies every moment and treats attention as a scarce resource to be optimized. Against this backdrop The Longing creates space for what we might call “non-productive duration.” And isn’t that exactly what philosophy does? Sitting in a barrel and exercising a form of non-productive result? The Shade’s waiting isn’t efficient or goal-oriented in conventional terms, yet it generates genuine meaning and care. This connects to recent work on “temporal justice” (Tyssedal 2021) and the right to slowness. The game doesn’t just critique fast-paced digital culture; it offers an alternative temporal relationship that feels politically significant because it advocates downshifting, slow scholarship and sensitization to crip time (Chazan 2023).

Astrid: Nicely put, Sebastian, although my personal game space seems infinitely more appealing than Diogenes’ barrel. On a serious note, though, your mentioning of slow scholarship, downshifting and the like makes me think about how The Longing might represent a new form of what we could call “slow gaming”—not just in terms of pacing, but in terms of temporal consciousness. The game makes time visible, audible, felt in ways that most non-literary digital fictions carefully hide. Csikszentmihalyi (1975) concept of flow reflects this apparent human need to forget or ignore the course of time really well, and it is continually evoked by game scholarship and design almost as the ultimate goal of media development. Conversely, the constant countdown, the real-time progression, the differential temporal mechanics—these design elements in The Longing create what might be called “temporal literacy,” an advanced awareness of how different media construct and manipulate our experience of duration. This seems increasingly important as we navigate digital environments designed to capture and commodify our temporal attention.

Kübra: I think what we’ve discovered through this conversation is that The Longing operates as a kind of temporal laboratory where players can experiment with different relationships to duration, attention, and care. The bookish elements, the unnatural temporal mechanics, and the interpassive companionship are features that situate the game within the emerging aesthetic category of games as existential instruments: interactive media that we can read as fostering philosophical inquiry and affective reflection.

Sebastian: Indeed, and perhaps what makes The Longing philosophically significant is precisely its refusal to resolve the tensions it creates. The game doesn’t answer whether waiting or acting, solitude or companionship, acceptance or rebellion, constitutes authentic existence. Instead, it creates conditions where these questions can be lived and explored rather than simply thought. In a time of global uncertainty, social isolation, and environmental crisis, games like The Longing offer something very tangible and valuable: spaces for contemplation, serenity, care, and resonance that resist the extractive logic of accelerationism and attention capitalism.

As afternoon light fades through the seminar room windows, the three scholars gather their notes, each carrying forward new insights from their interdisciplinary dialogue. Their conversation has illuminated how The Longing creates unprecedented possibilities for philosophical gameplay, temporal intimacy, and resistant forms of digital engagement—opening new directions for both game analysis and design.

5. Conclusions

Switching back to a unidirectional scholarly voice, we have seen The Longing emerge from our co-created trialogue as a work that transcends traditional categorical boundaries, demanding new analytical frameworks adequate to its formal idiosyncrasies and philosophical depth. Through the intersection of unnatural narratology, ludoliterary analysis, and existential philosophy, we have identified distant play as a form of parasocial resistance, as a metaleptic bond between player and avatar that resists the urge to give in to the culture of speed and operates simultaneously across temporal, literary, and ontological dimensions. That idlers can be an ideal playground for conceptually deep philosophical and poetic interventions has been demonstrated by our trilectic distant play analysis of The Longing. The game’s unnatural temporal mechanics, such as real-time progression independent of player presence, differential time with its accelerating or decelerating effects, based on activity type, and recursive unreading capabilities—create conditions for metaleptic temporality, where diegetic duration infiltrates actual life in emersive ways that foreground boredom as a possibility to build (parasocial) resistance. This violation of conventional narrative and ludic temporal logic requires players to develop new cognitive strategies, transforming antimimetic constraints into opportunities for alternative relationships to duration and attention: it causes players to literally slow down, reflect, and reconsider the alleged importance of flow in gameplay and other day-to-day activities. Our analysis has thus added further insight into the possibilities of engaging with impossible temporality in narrative game design and opened up new theoretical dimensions to the ever-growing repository of transmedial unnatural narrative.

The ludexical dimensions of The Longing demonstrate how reading practices can become forms of digital companionship. Through shared textual engagement with works like Moby-Dick and Thus Spoke Zarathustra, and the embedding of other books and texts into the game, players develop parasocial relationships with the Shade that transcend traditional boundaries between human and digital experience. The mechanics of dis-reading, unreading, and delegated writing create new forms of literary intimacy grounded in temporal rather than interpretive sharing. Furthermore, they demonstrate the intricacies of medial reading, which again deepen our understanding of how literary games may shape and expand reading and a playful, transmedial activity.

Finally, the existential philosophical framework covered in this article reveals how the game creates genuine conditions for contemplative practice within digital media. By requiring players to inhabit constraint rather than pursue unlimited possibility (see Harrington 2020), The Longing offers alternative models for authentic digital existence and for immersive, self-reflexive engagement with affective categories like fear, angst, and companionship. The game’s multiple endings suggest different approaches to the ethics of waiting, from acceptance through rebellion to termination, each reflecting distinct relationships to finitude and meaning-making.

Most significantly, our analysis demonstrates that distant play functions as a form of cultural critique, using slowness itself to resist the attention economy’s demands for constant engagement and immediate gratification. The Longing creates what might be called “temporal sovereignty”—the reclamation of the right to determine one’s own relationship to duration and depth in digital contexts. By creating conditions for genuine reflection on fundamental questions about time, agency, and digital relationality, the game opens new possibilities for electronic literature and literary gaming that blend experimental art and existential depth and open up new forms of transdisciplinary dialogue and entangled interpretation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, all authors; methodology, all authors; investigation, all authors; writing—original draft preparation, all authors; writing—review and editing, all authors; supervision, A.E.; project administration, S.R.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data was created.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Both non-diegetic and diegetic text in the game refers to the player character as “a Shade.” |

| 2 | The term ludexical is derived from Chloe Milligan’s ludoliterary concept of the “ludex”, which refers to instances of the ludic codex, or the represented print object in “games that reference print culture metamedially” (Ensslin 2014, p. 49, quoted in Milligan 2019, p. 3). Ludexical games are games that afford player engagement with represented books and other print artefacts, i.e., ludexical play, in ways that are non-trivial to the game’s overarching goals. |

| 3 | Her name is identical with that of the above mentioned narratologist, which we consider a curious if not “unnatural” coincidence. |

References

- Aksay, Kübra. 2025. Recording Nature in Alba: A Wildlife Adventure and Season: A Letter to the Future. In Video Game Ecologies and Culture. Edited by Nathalie Aghoro. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter Oldenbourg, pp. 109–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksay, Kübra, and Christian Bachmann. 2024. Digital Games Featuring In-Game Books, Book-like Objects, Book-Ish Design Elements, and Paper Art: A Selective Annotated Ludography. Berlin: Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksay, Kübra, Simone Blessing, Astrid Ensslin, Sebastian R. Richter, and Fiona S. Schönberg. 2024. Zur Konstruktion des ‘Bookish Players’ in Pentiment. In Zeitenwende: Interdisziplinäre Zugänge zum Spiel Pentiment. Edited by Aurelia Brandenburg, Lucas Haasis and Alan van Beek. Berlin: Mittelalterblog. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksay, Kübra, Simone Blessing, Astrid Ensslin, Sebastian R. Richter, and Fiona S. Schönberg. 2025. ‘The Name of the Reader’: Constructing the Bookish Player in Pentiment. In Metareference in Videogames: Mapping the Margins of an Interdisciplinary Field. Edited by Theresa Krampe and Jan-Noël Thon. New York: Routledge, pp. 169–87. [Google Scholar]

- Alber, Jan. 2016. Unnatural Narrative: Impossible Worlds in Fiction and Drama. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez Igarzábal, F. 2019. Time and Space in Video Games. A Cognitive-Formalist Approach. Bielefeld: Transcript Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Aristotle. 1996. Poetics. Translated by Malcolm Heath. London: Penguin Classics. [Google Scholar]

- Ashgames. 2020. Your feelings for the Shade. Steam Community. March 6. Available online: https://steamcommunity.com/app/893850/discussions/0/1745646819956105859/ (accessed on 28 January 2026).

- Baudrillard, Jean. 1981. Simulacra and Simulation. Translated by Sheila Faria Glaser. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. [Google Scholar]

- Beckett, Samuel. 1953. Waiting for Godot. New York: Grove Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, Alice. 2020. I Have Finished the Sad Tamogotchi Game That Is The Longing: The Last, Long Wait. Rock Paper Shotgun. April 2. Available online: https://www.rockpapershotgun.com/i-have-finished-the-sad-tamogotchi-game-that-is-the-longing (accessed on 28 January 2026).

- Bell, Alice. 2021. ‘It all feels too real’: Digital Storyworlds and Ontological Resonance. Style 55: 430–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, Alice, and Jan Alber. 2012. Ontological Metalepsis and Unnatural Narratology. Journal of Narrative Theory 42: 166–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogost, Ian. 2010. Cow Clicker: The Making of Obsession. Bogost.com (blog). July 21. Available online: http://bogost.com/writing/blog/cow_clicker_1 (accessed on 28 January 2026).

- Bolter, Jay David, and Richard Grusin. 1999. Remediation: Understanding New Media. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chazan, May. 2023. Crip Time and Radical Care in/as Artful Politics. Social Sciences 12: 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csaba, András. 2021. Türelemjáték—A The Longing és az idő. Apertura 16. Available online: https://www.apertura.hu/2021/tavasz/andras-turelemjatek-a-the-longing-es-az-ido (accessed on 29 January 2026).

- Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly. 1975. Beyond Boredom and Anxiety: Experiencing Flow in Work and Play. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Ensslin, Astrid. 2014. Literary Gaming. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ensslin, Astrid, and Alice Bell. 2021. Digital Fiction and the Unnatural: Transmedial Narrative Theory, Method, and Analysis. Columbus: Ohio State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ensslin, Astrid, and Alice Bell. 2024. Postdigital Reading Strategies in Emersive VR Fiction: Empirical Insights. Anglica. An International Journal of English Studies 33: 51–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fizek, Sonia. 2018. Interpassivity and the joy of delegated play in idle games. Transactions of the Digital Games Research Association 3: 137–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fizek, Sonia. 2022. Playing at a Distance: Borderlands of Video Game Aesthetic. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galloway, Alexander R. 2006. Gaming: Essays on Algorithmic Culture. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, Lewis. 2020. ‘The Longing’ Is a Video Game of Transcendent Slowness. Wired. December 15. Available online: https://www.wired.com/story/the-longing-game-review/ (accessed on 27 January 2026).

- Grice, Paul. 1975. Logic and Conversation. In Syntax and Semantics 3: Speech Acts. Edited by Peter Cole and Jerry L. Morgan. New York: Academic Press, pp. 41–58. [Google Scholar]

- Gualeni, Stefano, and Daniel Vella. 2020. Virtual Existentialism. Meaning and Subjectivity in Virtual Worlds. Cham: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Harrington, Jonathan. 2020. Workshops of Our Own: Analysing Constraint Play in Digital Games. Ph.D. thesis, City University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China. [Google Scholar]

- Heidegger, Martin. 1962. Being and Time. Translated by John Macquarrie, and Edward Robinson. New York: Harper & Row. First published 1927. [Google Scholar]

- Juul, Jesper. 2004. Introduction to Game Time. Electronic Book Review. July 9. Available online: https://electronicbookreview.com/publications/introduction-to-game-time/ (accessed on 28 January 2026).

- Kücklich, J. 2005. Precarious Playbour: Modders and the Digital Games Industry. Fibreculture 5: 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Leino, Olli T., and Sebastian Möring. 2025. Existential Ludology. Computer Games as Worlds. In The Routledge Handbook of Philosophy of Games. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzola, Guerino, Alex Lubet, Yan Pang, Jordon Goebel, Christopher Rochester, and Sangeeta Dey. 2021. Time in Philosophy. In Making Musical Time. Cham: Springer, pp. 13–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melville, Herman. 1997. Moby Dick. New York: Acclaim Books. First published 1851. [Google Scholar]

- Milligan, Caleb Andrew (now Chloe). 2019. From Codex to Ludex: Paper Machines, Digital Games, and Haptic Subjectivities. Publije: e-Revue de critique littéraire. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möring, Sebastian. 2019. Aesthetics of Care and Caring for Aesthetics in the Game Play of Walden, A Game and Eastshade. Paper presented at the 13th International Philosophy of Computer Games Conference, St. Petersburg, Russia, October 7–9; Available online: https://www.gamephilosophy.org/wp-content/uploads/confmanuscripts/pcg2019/Sebastian%20Moering%20-%20Aesthetics%20of%20Care%20and%20Care%20for%20Aesthetics.pdf (accessed on 29 January 2026).

- Nardi, Bonnie, and Yong Ming Kow. 2010. Digital imaginaries: How we know what we (think we) know about Chinese gold farming. First Monday. Peer-Reviewed Journal on the Internet 15. Available online: https://firstmonday.org/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/3035/2566 (accessed on 28 January 2026). [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Remesal, Víctor. 2026. Zen and Slow Games. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nietzsche, Friedrich. 1883. Thus Spoke Zarathustra. Los Angeles: Simon & Brown. [Google Scholar]

- Niven, Bill. 2010. The Legacy of Second German Empire Memorials after 1945. In Memorialization in Germany Since 1945. Edited by Bill Niven and Chloe Paver. London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 399–408. [Google Scholar]

- Pecorella, Anthony. 2015. Idle Games: The Mechanics and Monetization of Self-Playing Games. Paper presented at the Game Developers Conference, San Francisco, CA, USA, March 2–6. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Latre, Francisco J. 2026. Rebuilding Trust and Fostering Loyalty: Navigating the Challenges of Audience Engagement. In Media Engagement: Connecting with Audiences in Media Markets. Edited by Mercedes Medina and David Kimber. New York: Routledge, pp. 32–44. [Google Scholar]

- Pfaller, Robert. 1996. Um Die Ecke Gelacht. Kuratoren nehmen uns die Kunstbetrachtung ab, Videorecorder schauen sich unsere Lieblingsfilme an: Anmerkungen zum Paradoxon der Interpassivität. Falter 41: 71. [Google Scholar]

- Pressman, Jessica. 2020. Bookishness: Loving Books in a Digital Age. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pyta, Anselm. 2023. A Shade Plushie. Steam. January 27. Available online: https://store.steampowered.com/news/app/893850/view/3683415686331038350 (accessed on 28 January 2026).

- Richter, Sebastian R. 2022. Scheitern und Unfall. Zur theoretischen Fundierung und Mimesis des Akzidentiellen. Navigationen—Zeitschrift für Medien- und Kulturwissenschaften 22: 153–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, Sebastian R. 2025. The Shock of Silence. An Approach to Philosophical Immersion in Media. In Silence, Sounds, Music. Acoustic Dimensions of Immersion. Edited by Florian Freitag, Laura Katharina Mücke and Peter Niedermüller. London: Routledge, pp. 145–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, Sebastian R., Astrid Ensslin, Fiona S. Schönberg, Kübra Aksay, and Miriam Scuderi. 2024. Literary Gaming Refigured. Paper presented at the ELO (Un)linked, Online Conference, July 18–21; Paper 30. Available online: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/elo2024/hypertextsandfictions/schedule/30 (accessed on 28 January 2026).

- Rosa, Hartmut. 2010. Alienation and Acceleration—Towards a Critical Theory of Late-Modern Temporality. Aarhus: Aarhus University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rosa, Hartmut. 2019. Resonanz. In Eine Soziologie der Weltbeziehung. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp. [Google Scholar]

- Studio Seufz. 2020. The Longing. Heidelberg: Studio Seufz. [Google Scholar]

- Tomlinson, John. 2007. The Culture of Speed. Los Angeles: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, Victor. 1969. The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-Structure. Chicago: Aldine. [Google Scholar]

- Tyssedal, Jens Jørund. 2021. The Value of Time Matters for Temporal Justice. Ethical Theory and Moral Practice 24: 183–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vella, Daniel. 2019. There’s No Place Like Home: Dwelling and Being at Home in Digital Games. In Ludotopia: Spaces, Places and Territories in Computer Games. Edited by Espen Aarseth and Stephan Günzel. Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag, pp. 141–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiemer, Serjoscha. 2014. Das Geöffnete Intervall. Medientheorie und Ästhetik des Videospiels. Paderborn: Fink. [Google Scholar]

- Yalom, Irvin D. 1980. Existential Psychotherapy. New York: HarperCollins. [Google Scholar]

- Žižek, Slavoj. 1997. The Plague of Fantasies. London: Verso. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.