Abstract

This paper reads coal as a metonym for London’s social fabric in the writings of police theorist Patrick Colquhoun, the archival reports on the Wapping Coal Riot, and the anti-carceral poetry of William Blake. In 1798, at the behest of the West India Committee, Colquhoun had developed the first modern police force, the Thames River Police, which predated Robert Peel’s metropolitan police by over 20 years. Colquhoun’s “Treatise on the Commerce and Police of the River Thames” (1800) centers on coal in his case for policing. In his argument, coal’s energy economies link domestic affairs with the entire metropolis, making policing a city-wide problem, one that merits public support (and public funding). In reading Colquhoun’s treatise as an example of the entanglement of policing and fossil fuel power, I discuss the relevant literature from the energy humanities that connects fossil energy to the larger extractive ideologies of empire. I also demonstrate how Colquhoun’s figuring of coal builds on but alters portrayals of coal in Jonathan Swift and Anna Barbauld. The final section of this discussion demonstrates how Blake’s Jerusalem (1820) indexes dispersed, atmospheric systems of carceral power and summons dynamic, unpoliceable crowds. Blake’s smoke poetics sketch a limit of generalization, one that recoups figures of pollution and waste to riot against the systems that produce them.

1. Introduction

Jails invent cities.(Bonney 2019)

It might have seemed a valley which nature had kept to herself for pensive thoughts and tender feelings, but that we were reminded at every turning of the road of something beyond by the coal-carts which were travelling towards us.(Wordsworth 1897)

When Dorothy Wordsworth observes that the “coal-carts” driving along the River Nith in Scotland reintegrate an otherwise-isolated valley into networks of commerce, trade, and consumption, she certainly has one of Romanticism’s dominant narratives in mind—here, as elsewhere in her work, traces of industry intrude onto and corrupt a serene natural landscape. However, this passing comment from Recollections of a Tour Made in Scotland also adopts the coal trade as shorthand for a larger system. Whether the “something beyond” is a village, a city, a factory, or a port remains unsaid, in part because coal suggests any and all of them. Coal allows Wordsworth to perceive “something beyond” the Romantic pastoral, while not requiring that she pinpoint it. In fact, her deliberately winding syntax—“reminded at every turning of the road of something beyond”—all-but-guarantees that a reader will misapply “of something beyond” as a modifier to “the road” or its turning before we connect the phrase back to “reminded.” Because Wordsworth elsewhere treats coal as a uniquely British commodity, her metonymic deployment of “coal-carts” here extends past vague gestures to industry. Coal becomes a way to link the abstraction of the nation to its material, commercial, spatial, and urban components; it carries with it an implicit networked quality that allows Wordsworth and her companions to glimpse larger systems from within a remote valley.

This article argues that Wordsworth is not alone in her experiments with energy infrastructure as a perceptual tool. In what follows, I assert a connection between the rapid development of police power in London during the early 1800s and the coal-fired British national economy. Coal supplies the police theorist Patrick Colquhoun with a narrative of Romantic urbanity that (conveniently for him) necessitates the establishment of police. Colquhoun was a Scottish linen merchant and armchair statistician who devoted the latter half of his life to the expansion of policing in London1. In 1798, with funding from the West India Committee, Colquhoun founded the Marine Police, a semi-private police force that predated Robert Peele’s Metropolitan Police by 21 years. Despite the swollen authority with which enforcers in modern British cities are vested, the institution of police is a relatively novel one, driven by the growth of high-density urban populations, the boom of speculative political projects—bids for efficiency, modernization, and optimization—, and the repressive central government of the 1790s. In less than a century, London saw the establishment of Henry Fielding’s Bow Street Runners, Colquhoun’s Marine Police and Thames River Police, and Peele’s bobbies. This new police infrastructure emerged from earlier carceral apparatuses, which it centralized and standardized. E. P. Thompson, Peter Linebaugh, and Nicolas Rogers, among others, have demonstrated how early-18th-century enclosure laws and the mid-to-late 18th-century “Vagrancy Act” laid the legal groundwork for the discretionary power to arrest that characterized Colquhoun’s police (Thompson 1977; Linebaugh 2014; Rogers 1991).

Colquhoun outlined the principles of his system and tracked its effectiveness in a series of books, including “Treatise on the Police of the Metropolis” (1796), which went through seven editions, “A General View of the National Police System” (1799), and “Treatise on the Commerce and Police of the River Thames” (1800), the last of which is the focus on this essay. While at 676 pages, the treatise on the Police of the Thames isn’t a focused undertaking, the early how-to manual on urban policing devotes special attention to the coal barges arriving in London from central and northern England, Wales, Scotland, and Ireland. Coal operates as a shorthand for the unified networks of circulation that allow Colquhoun to appeal to London as a singular entity. In this sense, coal has a narrative function: it participates in reshaping Romantic narratives around urban space and circulation, which in turn inform police narratives of riot.

By connecting the narratives surrounding police to narratives of trade and urban fuel supply, I take my cue from Lily Gurton-Wachter’s Watchwords, which tracks the forms of attention, literary and otherwise, that attend the rise of surveillance culture (Gurton-Wachter 2016). Her argument understands carcerality as a perceptual problem, one that alters received modes of reading space and people. This article continues this approach to the study of carceral culture by offering coal as another form of reading urban space, one that predates, inspires, and colludes with carceral forms of looking. In the first section, I argue that Colquhoun used networks of coal consumption not only as a justification for a modern police force but as a model for police, drawing on the rhetoric of energy infrastructure as he defined policeable urban collectives. Part two discusses early resistance to the Marine Police from coal heavers, who rioted outside the new Wapping police offices on 16 October 1798. The newspaper reports and legal documents surrounding the Wapping Coal Riot demonstrate how the establishment of police changes the narration of the riot through changes to collectivity, urban space, and causality. The final section of this article reads for smoke in William Blake’s Jerusalem, The Emanation of the Giant Albion (1820). I argue that Jerusalem indexes smoky, atmospheric systems of carceral power while adopting the haziness and unwieldiness of smoke to summon dynamic, unpoliceable crowds. Blake’s smoke poetics sketch a limit of generalization, one that recoups figures of pollution and waste to riot against the systems that produce them.

2. Coal as a Way of Looking

While coal had been used for millennia in Britain (and elsewhere), the primary fuel in English fires remained wood until the early 18th century, when the Little Ice Age, combined with the deforestation that Alexander Pope laments in “Windsor-Forest,” prompted the widespread mining of coal (Smil 2017). Vaclav Smil estimates that by the end of the 18th century, Britain derived 90% of its energy from coal, drawing heavily on domestic coalfields in Northumberland, Durham, Yorkshire, Lancashire, and Cheshire (Smil 2017, p. 233). By the time Colquhoun began to survey systems of marine commerce around the Thames, the port of London was liable to have “300 colliers…at one time” (Colquhoun 1800, p. 26). As Heidi Scott writes, this shift “transfigured landscapes…reshaping human settlement patterns and the kinds of work performed” (Scott 2018, p. 21). While neither Scott nor Smil discusses policing, the influence of the coal trade on Colquhoun’s treatise bears out Scott’s claim that a society’s primary fuel source influences “the ideas, ambitions, and progress” available to it (Scott 2018, p. 9).

Colquhoun’s treatise conceives of early police systems in Britain alongside modern energy networks because coal provides a useful figure for circulation, shared resources, and collective identity that links domestic spaces and metropolitan networks. Finding that “the plunder of Coals is excessive,” Colquhoun hawks police as a boon “not only to original Owners and Coal Merchants, but also to every consumer of this species of Fuel, whose supplies depend on the importation into the River Thames” (Colquhoun 1800, p. 241). Because a majority of Londoners relied on coal, “laws which relate to Coals, Fish, Watermen” are “immediately connected with the common and domestic affairs of every family,” and the establishment of a police to protect collier barges should be “interesting to almost all classes in the community” (p. xxxiii).

Colquhoun’s choice of “interest” to describe what he considers the universal appeal of policing takes on greater significance when viewed through the opening pages of the “Treatise,” which approach London as an enormous joint venture. Despite appeals to the “pre-eminence” of the Port of London, Colquhoun’s history of the port confines itself to a history of its charters and joint ventures from 1558 onward, when “the same extent of legal Quays was then authorized as exists at present” (p. 3). The next few pages list the speculative maritime ventures founded in London, from an “adventure” undertaken by Lord Robert Dudley in 1563 to the founding of the Hamburg, Russia, Eastland, and East-India companies (pp. 4–5). This excruciatingly limited history, coupled with Colquhoun’s invocation of shared “interest” and “the interest and welfare of the State,” presents the port as a joint venture, one in which all Londoners have some stake. Sal Nicolazzo’s indispensable Vagrant Figures elaborates on the speculative nature of this central carceral system, one built on “population management” and predictive policing, demonstrating how literary accounts of vagrancy legitimized the police (Nicolazzo 2021). Here, it becomes apparent that the Port of London, like the police project, is always speculative. Cass Turner has recently argued that a defining figure of early capitalism was “a theory of commercial society in which the welfare of individual persons cannot be separated from the larger entanglement of populations, systems, and materials that fuel and constitute global trade” (Turner 2022). Speculative commerce helped shape the terms and conditions that adjudicate between individual and collective interests, often along racialized lines.

Coal aids Colquhoun in conjuring this speculative London, one that moves from the private hearth to the city at large. Kent Linthicum summarizes the early 19th century he characterizes as “sovereign, stabilizing, powerful, progressive, and ready to be endlessly extracted and burned by humanity” (Linthicum 2020). By way of example, the scale of coal’s geological history and the vastness of its stores led 19th-century chemist Friedrich Christian Accum to collapse the massive with the infinite: “Pit-Coal exists in this island in strata, which, as far as concerns many hundred generations after us, may be pronounced inexhaustible” (Accum 1815). As a figure for spatializing time, collapsing eons into lumps, coal gestures to broad swaths of speculative possibility. Like the coal in the pit strata, the coal in the harbor waits, with passive availability, to be used. In part, Colquhoun attributes “Criminal Depredation” on the Thames to the layout of the port: by the 18th century, ships were no longer able to dock at the port. Instead, lightermen maneuvered small barges of cargo from the ships to the docks. This arrangement had loaded colliers waiting in the river like “floating Warehouses, until the Coals can be disposed of” (Colquhoun 1800, p. 27). Colquhoun returns to the “floating warehouse” repeatedly, elsewhere estimating “That 1170 of these Craft are frequently laden with Coals at one time, while nearly as many are used as Floating Warehouses, above and below Bridge, waiting the calls of the Consumers, who require a monthly supply of 300 Cargoes of 220 Chaldrons each” (p. 142). The decision to figure the “floating property” in the Thames as so many colliers awaiting discharge doesn’t only draw on the presumed “universal interest” of coal to all members of the public; it also draws on coal’s suspended futurity. This link between the passive vulnerability of “floating property” and stored potential energy is made more explicit when Colquhoun compares theft on the Thames to fire. The introduction to the Treatise harps on the “advantages [of Police] to the National Revenue, and to the Public Stores, whether floating or in his Majesty’s Arsenals… While, from the vigilance of the system, the evil designs of incendiaries, who meditate ruin and conflagration among the Shipping, will also be defeated” (p. xxxviii). Coal’s ability to wait for the “calls of the consumers” as demand fluctuates becomes shorthand for market futures on the river writ large. Coal’s static availability, its infinite existence in pit strata, gets applied to the “Floating Property” in the Thames, “floating” not just because suspended in water but suspended in indefinite availability (p. 42).

Coal’s ability to narrate across scales of space and time is handy for Colquhoun, who aims for an unironically totalizing vision. He approaches the project as a kind of map: “the author has endeavoured [sic] in this work to draw a circle round every object that can be considered in any degree useful to the Commerce and Navigation of the River Thames…all that can be considered important or necessary will be found within this Circle” (p. iv). The text is meant to be totalizing, to begin and end the conversation on policing; in this, Colquhoun’s circle recalls Blake’s “Ancient of Days,” in which Urizen, pitched over his compass, circumscribes the earth with the law of misapplied reason2. Urizen is Blake’s figure for tyranny, and specifically for religious and political authority sharpened on the iron edge of Enlightenment rationality. This totalizing vision relies on a structural shift in police organization: “it is also necessary to consider the Metropolis as a great Whole, and to combine the organs of Police which at present exist, in such a manner by a general superintendence [sic], as to…instil [sic] one principle of universal energy into all its parts” (Colquhoun 1796, p. 414 n. 118). In other words, coal is a way of seeing, and not seeing, the city.

By the same token, coal helps Colquhoun limit the scope of his “total” vision, allowing him to downplay the influence of less-universal interests on the police. The Marine Police were developed in concert with private West Indian merchants looking to protect imported plantation goods—the products of stolen lives and stolen labor—from theft. Yet Colquhoun is rhetorically anxious to present the establishment and maintenance of a police force as a city-wide problem, one that merits public support and public funding. While the theft of luxury goods like sugar or tea only affects private merchants, coal links “common and domestic affairs” with “the entire metropolis” and the “Public Revenue” (Colquhoun 1800, p. xxxiii). That is to say, transatlantic slavery and extractive energy networks exist in mutually reinforcing processes, and Colquhoun uses the implied collectivity of coal as a smoke-screen for the corporate interests of slavers3. But reading the relationship between coal and police in the context of sugar economies, we can see how certain forms of collectivity, like energy or urbanity, become a means of talking around racialized and imperial forms of oppression. In this sense, concepts like energy or the city develop under the auspices of white supremacy and colonial economic greed and cannot be adequately understood without reading them alongside racial capitalism.

Coal has been used as a figure for reading circulation since the early 18th century, as we can see in Jonathan Swift’s “A Description of the Morning” (1709) (Swift 1973). The operative feature of the poem is synecdoche, with the labor of the individual person is made to represent a body of workers—we have Betty, the master, the apprentice, the small-coal man, duns (debt-collectors), the turnkey, his flock, the bailiffs, and schoolboys, so that the city is populated exclusively by people who are busy or are trying to look busy. As William Wordsworth would write of London over a century later, “life and labour seem but one” (Wordsworth 2008). The poem’s circulation of order and mess, coupled with the carefully controlled rhyme, renders London as a closed ecosystem, one in which matter, including waste, is neither created nor disappeared, but rather shoveled around. We see the tightness of this circuit most clearly in Swift’s joint descriptions of carcerality and coal. Coal connects and permeates Swift’s London, moving from the supply of street vendors back into houses and out again: “The small-coal man was heard with cadence deep;/Till drown’d in shriller notes of ‘chimney-sweep’” (ll. 11–12). The contrast between the mature voice of the small-coal man and the voice of the chimney sweeps suggests that London’s self-perpetuating cycle of coal mirrors and inverts the human lifecycle, suggesting that fossil fuel has reshaped human life. The poem ends on three images of early carceral control—the turnkey, his “flock,” and the bailiffs:

The turnkey now his flock returning sees,Duly let out a-nights to steal for fees.The watchful bailiffs take their silent stands;And schoolboys lag with satchels in their hands.(15–18)

Having burned through the intimate and domestic, the poem closes with predecessors of the Marine Police, to which Swift applies the same closed-circuit logic: like the coal man’s wares become not waste but the labor of the chimney-sweeps, the jailor releases prisoners to steal and collects the profit. Notably, the tense of the poem changes between Moll and the turnkey, moving from the past-perfect “now had” to an immediate present (“the turnkey now…sees”). The glitchy tense dramatizes the organizing impulse of police vision, which fixes simultaneous actions into a list4. At stake here is the process by which the “City” (“the entire Metropolis”) comes to exist as a policeable whole.

Moreover, Swift demonstrates that the labor-and-resource-based view of human life succeeds only by carefully refusing to see certain byproducts. While other laborers are meticulously embodied in the poem, the chimney sweeps are not represented by a singular person (a Betty, a ‘prentice), but by an indefinite number of “shriller notes” that announce the presence of one or more child laborers without materializing them into a body. This non-embodiment happens grammatically, too. Most of the characters mentioned in this poem are the grammatical subjects of independent clauses, but the chimney sweeps are appended as a prepositional phrase in the “small-coal man’s” lines to clarify how his cadence was drowned. The disembodied child or children diffuse from what should be a self-contained one-or-two-line image (if we follow the established pattern of the poem) into the dominant sound on the right margin, since the next four lines adopt the sharp “ee” of “chimney-sweep”:

The small-coal man was heard with cadence deep;Till drown’d in shriller notes of “chimney-sweep.”Duns at his lordship’s gate began to meet;And brickdust Moll had scream’d through half a street.The turnkey now his flock returning sees,Duly let out a-nights to steal for fees.(11–16)

Later writers who describe the chimney sweeps of London, like Mary Robinson and William Blake, emphasize their humanity, but Swift demonstrates how coal, like police, has the power to erase individuals, to collapse them into waste. The chimney sweeps, by becoming sound, operate like smoke or soot, infiltrating the rest of the poem even as they are pushed beyond the poem’s margins. Pointedly, Swift locates this abstraction and disembodiment in the moment where energy systems become visible, in the power to decide who and what is wasted.

Shortly after their founding, the Marine Police moved to abolish a labor practice called “custom” or “sweepings,” the collection of fragments of coal (or sugar or tea) that had previously supplemented laborers’ wages. Under the new system, these “entitlements” became tantamount to theft. Colquhoun, and later Jeremey Bentham, argued that the practice incentivized workers to create “artificial waste” (for example, by deliberately spilling sugar), and without a way to distinguish between “artificial” and “real” waste, the Marine Police banned all sweepings (Bentham 2018, pp. 39–41, n. 82). Note that none of the logic of infinite resources applies here. Rather, police derive their authority from the power to demarcate the acceptable limits of waste, artificial or otherwise. As part of his justification for the abandonment of custom, Colquhoun presents “theft” as an inevitable tendency among the people he wants to police:

Indeed, it has clearly been ascertained, that the plunder of Coals is excessive, and committed in various ways.- First, in the Ships during the discharge, through the medium of the Coal-heavers, where the property of the Owners, and the Public Revenue, suffer very considerably: sometimes by the connivance, and even (as has appeared in evidence,) the consent of the Masters and Mates of Colliers, in order to procure the advantage of additional labour, which ought to have been paid for in money; but, more frequently, from the thieving disposition and audacious conduct of the Coal-heavers, who being more powerful than the Ship’s Crew, have been accustomed in many instances, to remove such Coals as remained on Deck by force.(Colquhoun 1800, p. 142, author’s emphasis in italics)

Although Colquhoun leads with a critique of custom and a note that labor “ought to have been paid for in money,” he tells his reader to prioritize the “thieving disposition” of the coal-heavers, who use their numbers and strength to intimidate sailors. The coal-heavers’ physical strength—a requirement of the job—here serves to emphasize the danger they pose to “the Owners and the Public Revenue.” Not only are the laborers collapsed into the work they do, but working with coal implicitly makes them more likely to have a thieving disposition. As in Swift’s poem, coal is given the ability to change the people who handle it, altering crowds and how they are perceived.

3. Gleaning Context: The Wapping Coal Riot

Colquhoun’s treatise demonstrates that coal, as a narrative trope, provided a referent to the Marine Police as they developed techniques for reading, organizing, and controlling urban space. Yet coal’s utility for police becomes more apparent in the face of early resistance to the police. The Wapping coal riot unfolds amid an energy infrastructure that shapes how the riot is narrated, how collectives are perceived, and how police involvement is justified or rationalized. On 16 October 1798, a few months after their establishment, the Marine Police convicted coal heaver George Eyres of collecting sweepings and fined him 40 shillings, the equivalent of several weeks’ work5. Eyres paid the fine at their office and left. Shortly thereafter, a crowd—consisting primarily of coal heavers—arrived at the new Wapping office, breaking its windows and throwing stones inside. Police fired on the crowd, killing coal heaver James Hanks. Later in the evening, gunfire fatally wounded master-lumper and police contractor Gabriel Franks. Newspaper accounts of the riot almost exclusively refer to a “mob,” and major contemporary newspapers recycle variants of the following text sourced from The Times on Wednesday, 17 October 1798:

About half after 8 o’clock yesterday evening, while the Magistrates were in the execution of their official duty, a most furious and outrageous mob assembled round the Marine Police Office, and after shouting, instantly attacked the windows, broke the outside shutters, threw in large stones, and did a great deal of damage. As soon as it was possible for the Magistrates and officers to force their way to the street, the Riot Act was instantly read; but before this was effected, while the mob were attempting to break into the house, the officers, who were by this time armed, fired one or two pistols, but the mob continued notwithstanding to be very outrageous, nor was it possible to make the least impression until one of the mob, a coal-heaver, was shot.(“Alarming Riot” 1798)

Mary Fairclough has previously argued that in the wake of the French Revolution, commentators on public protests adopted the concept of a contagious sympathy to explain protests, riots, and collective action. In this context, sympathy came to be “understood as a disruptive social phenomenon which functioned to spread disorder and unrest” (Fairclough 2013). In her accounts of the press surrounding the Spa Fields riots of 1816, Fairclough observes that mainstream papers treated this contagious sympathy as a threat to public safety, while homegrown pamphleteers found, in the same framework, the possibility for solidarity. Eighteen years earlier, newspaper coverage of the Wapping Coal Riot abided by the same formula. This fragmented account has the mob emerge out of thin air in that first sentence; only in the last two paragraphs do we learn that the riot begins with the conviction of George Eyres earlier in the evening. In their article “Lyrical Riots,” Nicolazzo engages more extensively with newspaper and archival accounts of the riot, and demonstrates how these records “collate multiple voices into a sense of collective intent that relies on ascribing a ‘voice’ to a crowd.” I direct readers back to their article for an analysis of the rhetorical strategies used to produce the crowd’s voice. Here, I only want to add that in fabricating the mob as a collective unit, one to which agency can be ascribed, newspapers resorted to manipulating the temporality of their narrative of the riot.

The temporality of the article leans heavily into the non-linear, and its sentences double back (“after shouting,” “but before this was effected,” “by this time armed”). In part, this fragmentation is part of a rhetorical sanitization campaign undertaken by these reports to defend the actions of the police, who fired on the crowd and killed Hanks before reading the Riot Act. The Riot Act, much like modern rules around the “unlawful assembly,” required magistrates to verbally declare a riot unlawful; after this speech act, participants were subject to arrest, and local officials were indemnified against prosecution for any harm (including killings) they might cause while suppressing the riot. The article side-steps this breach of protocol by rearranging clauses: “the Riot Act was instantly read; but before this was effected,” the two pistols were fired. This glitchy temporality hinges on the problem of “instantly” meaning (at the time) both “immediately” and “urgently.” The emphasis on explosive violence—the rioters are described as “furious and outrageous” and disperse only when confronted with police violence—presented the riot as excess spilling over. As the article concludes, “A more sudden attack, and a more furiated mob perhaps never was known” (“Alarming Riot” 1798).

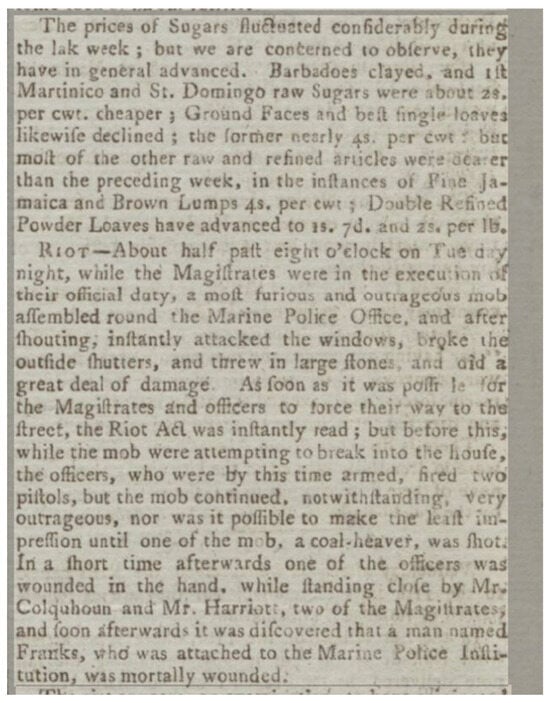

In the first third of Riot. Strike. Riot (2016), Joshua Clover attempts to isolate a stable definition of riot that does not reduce it to a mechanical reaction against price increases or send itself into raptures over the “emanation of a diaphanous structure of political feeling” (Clover 2016). Even the most straightforward definition, that a riot is an outbreak of violence, is handily dismissed as the “political reduction of the riot, its cordoning off from politics proper” (Clover 2016, p. 19). Riot, for Clover, concerns its material, political contexts: the riot “struggles to set prices in the market, is unified by shared dispossession, and unfolds in the context of consumption” (Clover 2016, p. 11). Clover’s definition must walk a line—without resorting to calls for peaceful protest, he understands that the riot’s surge of collective energies, particularly when they produce violence, are cheerfully slotted into narratives like the one in The Times, in which the collective action feels sudden and spontaneous. The article’s calculated fragmentation presents the riot as a glitch or exception, an unpredictable crisis to which the police respond, rather than a direct response to efforts on the part of police to control labor on the docks—including hiring and payment. This state of exception, of crisis without context, extends to the structure of several print versions of this story. In the Kentish Gazette, for instance, the title “RIOT” encourages readers to see the riot as an unexpected but instantly understandable situation. Pure violence, a riot needs no elaboration (“London” 1798). Yet if we look at the print column in which the article appears, we can see the Wapping Coal Riot in a much larger context, since the article follows on the heels of the recitation of sugar stock prices (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Detail of the section “London” in the Kentish Gazette, 19 October 1798. In the same column, a paragraph listing stock prices in sugar abuts a section entitled “RIOT—,” which details the events of the Wapping coal riot. Note, too, the overall cut-and-paste coverage of the event, which echoes the Times excerpt cited above with only minute variations. Accessed via the UK Newspaper archive, 17 October 2025.

This limited causality, which displaces riot onto the spontaneous violence of the crowd, works to quarantine riots from larger networks of racial capitalism by presenting riots as isolated pockets of crisis. The designation of the mob in these accounts is a political tool that likewise removes the riot from larger contexts and delegitimizes the rioters. When James Eyres, brother of George and another London coal heaver, was convicted of the murder of Franks in January 1799, no one believed that he had actually fired that gun (“James Eyres” 2020)6. Eyres was tried for inciting the riot, which, to the judge’s mind, made him “the wicked occasion of the loss to society of an innocent individual…because all persons who take an active part in a riot are answerable, by the sound policy of our law, for all the dreadful consequences which are most likely” (“JAMES EYRES. Killing; Murder. 9th January 1799” 2023). In order to legitimize this conviction, much of the trial of James Eyres attempts to prove definitively that Gabriel Franks was killed by a shot from the crowd and not by friendly fire; an eyewitness who claimed she heard only one shot and believed that Franks and the civilian protestor had been killed by the same police bullet had her character summarily attacked by a series of character witnesses called by the prosecution. The equivalence that makes Eyres answerable for any actions taken by any other protestors represents a new form of collectivity in British law, one that treats rioters as a uniform entity. This version of collectivity works backwards from the logic by which individual consumers of coal are told to take an interest in the global circulation of coal.

Crucially, and counterintuitively, energy infrastructure lays the groundwork for the equivalence that allowed Eyres to be prosecuted for the death of Franks. While Franks is named by newspaper accounts of the riot, the coal heaver James Hanks is only named in a handful of articles, including the Oracle’s October 18th account of Charles Eyres’ deposition (“Fatal Affray at the Marine Police Office, Wapping” 1798). Instead, most next-day reports on the riot argue “nor was it possible to make the least impression until one of the mob, a coal-heaver, was shot.” The almost-oxymoronic expression “one of the mob” emphasizes the fungibility of the individual and the collective in police views of the rioting public. Hanks does not die as an individual: the article’s syntax presents his death as a necessity for “making an impression” on the mob, while the addition of “a coal-heaver” effectively lifts Hanks from one collective and plops him into another. The addition of “a coal-heaver,” in particular, seems designed to mark Hanks as dangerous and implicitly justify his death. By being not just one of the mob, but a coal-heaver, Hanks is assigned to a dangerous public. Recall Colquhoun’s reference to their “thieving disposition and audacious conduct.” As a crucial aside, police assumptions about coal heavers draw on and reinforce the racializing assemblages of the early 19th century. Coal-heavers were one of several professions listed alongside racialized others in accounts of 19th-century London, as in an account of a public house in the London East End: “All was happiness!—… The group motley indeed;—Lascars, blacks, jack tars, coalheavers, dustmen, women of colour, old and young, and a sprinkling of the remnants of once fine girls, &c. were all jigging together” (Egan 1821, Cited in Linebaugh and Rediker). The context of the Wapping Coal Riot thus expands beyond early police interference with custom to position maritime labor within larger systems of imperial and plantation economies. Moreover, the use of ecological or geological activity to understand or control human activity remains a pattern in carceral thinking. In a glaring example, the snake-oil mathematics of LAPD’s PredPol misapplied seismology algorithms—designed to predict earthquakes and aftershocks—to forecast crime, operating on a broken-windows assumption that any crime makes nearby crimes more likely. Their recourse to geologic predictive technologies attempted to legitimize a racist and ineffective approach7.

The last two sections have shown how the establishment of police fashions new forms of Romantic urbanity that coincide with a push toward the standardization of the wage and the centralization of the police. Amidst changing urban and energy infrastructure, Colquhoun’s London emerges as, first and foremost, an economic venture in which coal is used to induce the public to protect behemoth charter companies. The narratives that Colquhoun and the press adopt around the riot reflect coal’s logics of consumption and circulation. Under this paradigm, generalization and collectivity operate as interchangeable forces of erasure and control, a means of crystallizing urban spaces into a sharp-edged and policeable metropolis. However, the final arc demonstrates how refocusing from shared networks of future consumption to shared networks of waste introduces queer and ambient approaches to urban spaces8. Reading Jerusalem, The Emanation of the Giant Albion, I make a case for William Blake’s romance with smoke, a desire that turns, queerly, toward figures of pollution as sites of anti-carceral reading.

4. Jerusalem’s Queer Urbanity

Jerusalem, Blake’s sprawling illuminated epic poem, is unique among his work in the scope and intensity of its engagement with carceral power (Blake 1982). Not coincidentally, Jerusalem is also one of Blake’s smokiest poems. The London that furnishes Los and his specter with their forge is catastrophically, almost comically, grimy, polluted not only by smoke but by the “high-decibel assault” that Stuart Peterfreund terms Blake’s “din of the city” (Peterfreund 1997). As we learn on plate 5, “The banks of the Thames are clouded! the ancient porches of Albion are/Darken’d! they are drawn thro’ unbounded space, scatter’d upon/The Void in incoherent despair!” (J 5.1-3, E 147). This expansive, shapeless mire is the world Blake calls “Ulro,” a living hell defined by the joint tyranny of state militarization and organized religion, by the endless accumulation of industry’s “Starry Wheels,” and by rabid imperial expansion. Albion, Blake’s figure for the universal man, shambles through the first chapter, licking his psychic wounds and imposing ill-calculated attempts at control onto other characters. Meanwhile, the eponymous Jerusalem (Albion’s emanation) “is scatter’d abroad like a cloud of smoke thro’ non-entity,” her smoky circulation positioned in networks of global commerce (5.14, E 147). Smoke points to obscurity and dissolution, a sense of scale without shape, of enlargement “without dimension.” It supplies a partial presence, a trace of “incoherent despair,” like the echoes of “chimney sweep” that litter Swift’s London. Yet while Blake presents smoke as a feature of the fallen world, the poem adopts its dispersals and irregularities as a response to the police.

Since Morton D. Paley’s assertion that the frontispiece of Jerusalem depicts Los in the garb of a night watchman, scholars have noted the subtle but unmistakable presence of carceral systems in Jerusalem and Milton (Paley 1991). The “Watch Fiends,” which Lily Gurton-Wachter links to “state-sanctioned surveillance and spying,” first emerge as antagonists in Milton, cataloging and criminalizing “Human loves/And graces” (M 23.40, E 119) (Gurton-Wachter 2016). They reappear in Jerusalem as timekeepers and cartographers who “search numbering every grain/Of sand on Earth every night” (J 35.2, E 181). Sinister and mindlessly bureaucratic, they share Colquhoun’s commitment to surveillance, data, and uniformity. Jake Elliott also treats the watch fiends as a figure for the nescient London police and contrasts their authoritarian tendencies with the night rambles of Jerusalem’s watchman, Los. Reading Jerusalem alongside early-19th-century debates about police replacing the parochial watch, Elliott suggests that the defunct figure of the watchman provided Blake with “a pre-existing alternative to the central power of ‘authority’” (Elliott 2024). Both Gurton-Wachter and Elliott ground Blake’s anti-carceral in his rejection of police modes of seeing. For Watchwords, Jerusalem models a bifurcated, dynamic attention at odds with the laser focus of carceral surveillance, while Elliott reads the watchman as not just a parochial holdover but as a way of inhabiting urban space.

Smoke, too, allows Blake to experiment with anti-carceral perception. Discussion of Blake’s engagement with industrial imagery tends to hew toward a party line in which the pastoral is corrupted by industry, even if Blake delights in the strangeness of this corruption. Michael Ferber offers an early foray into Blake’s repudiation of industrial and military production (Ferber 1985). Meanwhile, Jacob Henry Leveton notes the correspondence between the character Urizen and Boulton and Watt’s steam engine (Leveton 2022). In Fuel, Scott reads Blake’s furnace as an endorsement of “the dark energies of industry:“ “Luvah is, in effect, iron that is refined by the blast furnace, ‘cruel’ though necessary work” (Scott 2018, p. 100). She offers Blake as a brief but significant example of a Romantic artist who, rather than clinging to a halcyon past, took the coal-powered industry seriously as a model for revolutionary and creative forces. Elizabeth Effinger splits the different in William Blake: Modernity and Disaster, suggesting that Blake explores the queer potential of new scientific developments but ultimately discards them (Effinger 2020).

However, I argue that Blake gravitates toward smoke as an unsalvageable figure. Smoke marks the desire to sense, inhabit, or navigate larger systems of commerce and carcerality; it provides a material trace of otherwise-abstract systems, and Blake wields this trace to engage with and reject the forms of consolidated urbanity proposed by Colquhoun. Jerusalem’s smoke appeals to an increasingly abstract and equally oppressive government, scrambling for a figure with which to make the law visible. The result is the kind of atmospheric violence that defines Mary Favret’s War at a Distance, and yet Jerusalem closes that distance, such that “Albions [sic] mountains run with blood” (J 5.6-8, E 147). Both in and beyond Jerusalem, smoke recurs not only as a figure for material waste but also as a figure for misreading harm as impurity. After being raped by Bromion in Visions of the Daughters of Albion, Oothoon compares herself to the “new-washed lamb tinged with the village smoke,” hoping to convince her lover Theotormon to abandon his fixations on sin, impurity, and defilement, or at least to stop misapplying them to her (V 3.28, E 47). The character Jerusalem, too, is condemned as a “harlot” of “pollution” whose “cloud of smoke” recalls Oothoon’s smoky lamb. Blake effectively dares us to read smoke, in his poetry, not only as the real-world contaminant that he would have been breathing in Lambeth, but as a limit case for received modes of adjudicating between pollution and purity. Here, we should note that 19th-century understandings of air pollution differ greatly from our own. As Peter Thorsheim notes, the majority of Londoners in the 1800s would have considered coal smoke beneficial, a repellant for miasma (the disease-causing unwholesomeness believed to be produced by decaying matter) (Thorsheim 2006). The result is an unexpected turn toward smoke not only as a tool for sensing a diffuse harm but as a figure for expansive collectives. Rather than looking to a pastoral history polished beyond recognition, Blake uses smoke to suggest that, through the lens of carcerality, utopia (as Jerusalem) might look like soot.

If this figurative refashioning of smoke seems to be in bad taste, Blake’s attention to the metonymic drift between literal smoke and smokiness, his investment in a poetics of useless materials, works explicitly to disrupt the kind of seeing that Colquhoun would have us do. Max Liboiron has demonstrated that the dangers posed by individual contaminants should not be isolated from the larger systems that embed those contaminants in daily life. Neither the BPAs in Liboiron’s case study nor the hydrocarbons in soot pose a threat solely because of their chemical interactions with living cells. They become systematically dangerous through the larger processes of colonial consumption and circulation that facilitate large-scale pollution. To focus on eliminating BPAs from food cans while ignoring the foodways that force people to eat primarily canned food misses the larger issue (Liboiron 2021, pp. 81–83). Liboiron demonstrates how this limited environmentalism emphasizes “cleaning,” “purifying,” or “restoring” individual sites in order to ignore larger colonial land relations. If we extend Liboiron’s argument to coal, we might argue that air pollution from smoke—undeniably a health hazard—is only one facet of an imperial land relation that sees coal as infinitely available future energy. After all, Colquhoun’s emphasis on the household consumption of coal carefully sidesteps the fact that much of the coal imported to London was fed to the steam engines of modern factories. It is for this reason that Bernardo Jurema and Elias Konig define different empires by the carbon fuel that enabled them and observe that “coal powered the rise of the British Empire” (Jurema and Konig 2023).

By contrast, Blake’s shift toward smoke and pollution operates as an emphatic rejection of the temporality of empire. Jerusalem the cloud of smoke is not a barge of ancient vegetable matter hording potential energy, nor is she a beautiful but polluted city that can be scrubbed clean by an army of invisible child laborers; for much of the poem, she is pollution itself, a future that has already been consumed, and “The Cities of the Nations are the smoke of her consummation” (J 43.23, E 191). Nor does the poem’s conclusion resolve this identification of Jerusalem with diffuse pollution. Chapter 4 throws us into apocalyptic cycles of death and rebirth where “all Human Forms” “[go] forth & [return] wearied,” sleep and awake again, amidst which our speaker writes: “I heard the Name of their Emanations they are named Jerusalem” (J 99.1-5, E 258–259). Jerusalem effectively ends the poem not as one emanation (of Albion) but as the plural emanations of “all Human Forms,” a dissolution that Julia Wright sees as positively viral (Wright 2004). Here we might return to Colquhoun, and his account of “depredations” that spread both like religious indoctrination and to pollution—“New Converts to the System of Iniquity were rapidly made. The mass of Labourers on the River became gradually contaminated” (Colquhoun p. 41). In tracing the diffusion of Jerusalem, Blake adopts the airy expansion of smoke instead of the circulation of coal, staging the poem’s bid for a liberated imagination against a backdrop of urban harm and haze. If Colquhoun reads London as a closed circuit where fossil fuel economies and early carceral systems operate in tandem, smoke poetics shelters in the ecologically hazardous and, as I argue below, queer.

In one of Jerusalem’s more surprising asides, Albion “[finds] Jerusalem upon the River of his City soft repos’d/In the arms of Vala, assimilating in one with Vala” (J 19.41-42, E 164). Beyond being a more overt depiction of queer sex for the Romantic period, this moment is striking for its tenderness between two characters (Vala and Jerusalem) who spend most of the poem at odds. It is famously difficult to assign obvious labels or roles to different characters in Blake, but a quick-and-dirty summary might go like this—Jerusalem, who Blake elsewhere calls “Liberty,” represents a generous imagination and a psyche liberated from religious and political dogma, while Vala is loosely affiliated with the material world, which makes her by turns unpredictable, jealous, and authoritarian. Given these associations, we could read their relationship as a shorthand for runaway industrialization, especially because Blake repeatedly describes Jerusalem “[wandering] with Vala upon the mountains,/Attracted by the revolutions of those Wheels the Cloud of smoke/Immense” (J 5.61-63, E 148).

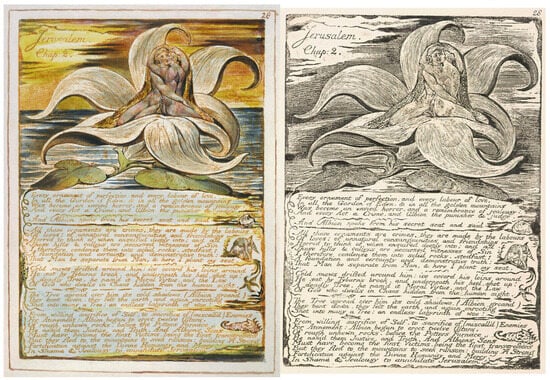

Blake situates the moment of repose between Jerusalem and Vala in the context of pollution and smoke. The image that most corresponds to this scene comes a few plates later, at the start of Chapter 2. Consumption and consummation exist side-by-side as the women rest under a dark haze thrown into relief by the same sunny backdrop that they obscure. Curling at the center of the image, the petals of the flower almost evoke flames. It helps that we have been primed to read the plate this way because when Jerusalem and Vala appear together, they are usually in a cloud of smoke, but the sky behind them seems calculated to evoke soot. The colors on this plate recycle the red, orange, yellow, and black of the engraving immediately preceding this one, which depicts a man in flames, and of other plates which explicitly illustrate fire and smoke, including Plate 69. Moreover, the engraving that underlies the watercolor on Plate 28 best resembles other plates where Blake intends to illustrate smoke or flames. Jerusalem utilizes a combination of relief etching (Blake’s infernal method) and white line engraving, the latter of which requires straighter, more uniform lines. In unpainted copies from earlier editions of Jerusalem, like copy A, it is easier to see that Blake favors the freehand curls of relief etching in his illustrations of clouds. However, the background of Plate 28 in Copy A uses the hash pattern of white-line etching, which he uses elsewhere in Jerusalem to illustrate flames, smoke, and haze10. Joseph Viscomi cautions us against investing the differences (or in this case, similarities) between editions with too much significance, since these variances often resulted from the print technologies available to Blake at the time (Viscomi 1993). However, Plate 28 in Copy A seems even more insistence on the murkiness of its background than Plate 28 in Copy E, abandoning either sky or water altogether. The result is a moment of intimacy floating on a backdrop of ambient, indeterminant harm.

In the style characteristic of “Blake’s composite art,” the image of Jerusalem and Vala on Plate 28 is not printed near the lines in the poem to which it seems to correspond. Instead, we see this image several plates later, at the start of a new chapter. On this page, Albion has begun his program of tyranny, where “every Act is become a Crime, and Albion the punisher & judge” (J 28.7, E 174). Albion’s mass criminalization reflects the intense political repression in England while Jerusalem was composed, and certainly reflects the gag acts, libel laws, and mass surveillance that defined British politics during the French and Haitian Revolutions and Napoleonic Wars. That said, Albion’s arbitrary designation of crimes also reflects Colquhoun’s arbitrary definitions of criminal activity on the banks of the Thames, since Colquhoun’s police not only enforced existing laws but also rewrote hiring and compensation practices. The arrangement of this plate implies a clash between the non-productive pleasure of the illustration and the tyranny in the text (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Plate 28 of Jerusalem, The Emanation of the Giant Albion in Copy E (printed c. 1821) and Copy A (printed before 1820). Vala and Jerusalem, nude, embrace at the center of a large lily which floats on murky water. As is characteristic of Blake’s “composite art,” the text of the poem extends and reflects the plate’s visual elements. Accessed via The William Blake Archive, 17 October 2025.

Blake’s depiction of queer sex and smoke shares with Colquhoun’s London an interest in identity, pollution, and commerce. First, as in the poem, the plate makes it very difficult to pick out where Vala ends, or Jerusalem begins, or even to decide which is which. Their arms join in a neat circle, and their limbs blur into each other and into the sky. The figure on the right would be indistinguishable from the clouds, save for the arm tracing her face. That blurriness is extended into Vala’s veil, typically Blake’s figure for shame, sin, and the material world. Here, the veil matches the colors of the smoky sky, and where it normally operates as a figure of repressive secrecy, on this plate, the atmospheric veil works more like a peaceful shelter. Rather than exposing the women to systems of the law, they disappear into atmospheric effects. The assimilation between the two women anticipates the visual blur that we find on the page, and this introduces another figure for what Blake calls “self-annihilation,” his term for creative liberation. Blake’s best definition of self-annihilation comes in Milton, A Prophecy, when Milton says of his material form, “This is a false Body: an Incrustation over my Immortal/Spirit; a Selfhood which must be put off & annihilated…I come in Self-annihilation & the grandeur of Inspiration” (M 41.35-42.2, E 142). The rejection of the “incrustation” of the self also entails, for Blake, the rejection of optimization and empirical fact: Milton resolves “To cast off Bacon, Locke & Newton from Albion’s covering,/To take off his filthy garments & clothe him with Imagination,/To cast aside from Poetry, all that is not Inspiration” (M 42.4-6, E 142).

Readers more familiar with a Blake who insists that “To Generalize is to be an Idiot” (E 641) and that “a Line is a Line in its Minutest Subdivision… It is Itself & Not Intermeasurable with or by any Thing Else” (E 783) may be surprised that he takes self-annihilation as his artistic and political ideal. Yet for Blake, the self is primarily a source of political legibility and sensory isolation. In the bleakest chapter of The Four Zoas, Night 6, Urizen’s imposition of law confines the “ruind spirits” of his children, such that “Beyond the bounds of their own self their senses cannot penetrate” (FZ 70.12, E 347). Saree Makdisi has argued that, in addition to material isolation, the self epitomizes the political and social isolation of a liberal subject. Blake’s insistence on the irreducibility of particulars to each other is not “the expression of bourgeois intellectual autonomy but rather as the expression of an alternative political and cultural position, one antithetical to the argument centered on the liberty of the individual subject” (Makdisi 2014, p. 145). Jade Hagan, too, reads Blake’s joint insistence on and skepticism around collectivity as constitutive of his larger project—Jerusalem, as she reads it, strains for and then against the “all” (Hagan 2020). Hagan’s account of the network in Jerusalem emphasizes the poem’s movement between the infinitesimal and the cosmic, the individual and the global. In this account, Blake circles the same questions of collectivity and urbanity as Colquhoun in Treatise. However, Blake’s vision of the city works backwards from Colquhoun’s. While Colquhoun develops police to protect a city that exists in the speculative tense from violence that exists in the speculative tense, Jerusalem misuses urban environments to demonstrate that those futures are inseparable from the police. The police remake the city, irreparably, and are inherent in every piece of its infrastructure. The metropolis that Colquhoun cites as the rationale for the creation of police does not preexist the police.

The awkwardness of “assimilating in one with” makes it difficult to say that either of the women really becomes the other. Rather, their assimilation highlights their shared convergence with urban space; sonically, “assimilating” even catches and recycles the short “i”s of “river” and “city.” The stack of prepositions (“upon,” “in,” “in on”) emphasizes spatialization while abstracting that spatialization beyond recognition. Even the syntax of “upon the river of his city soft reposd” suggests that it is the river of the city that is “soft reposd,” not the character. This emphasis on space without location—on unlocatable, floating, space—rejects the centralizing logic of Colquhoun. The river is a key site for this union because it raises the stakes of sex to the stakes of commerce, because it suggests that police will find their way into the most personal encounters. The absence of commerce on the river also suggests that in this scene of sweet “repose,” the trade along the Thames has been transposed onto two bodies whose coupling resembles equivalence or exchange. If there is a corollary to riot here, it is not queer sex; instead, it is the decision to replace the floating barges of to-be-consumed property at the site of imperial commerce with an awkwardly analogous moment of personal exchange or consumption.

Blake’s decision to superimpose two women and a flower over a space normally filled with barges of floating property interrupts the speculative temporality of the port with the immediacy of sex. The scene does not supply a perfect metonymic reimagining of commerce, but it is not as comfortably removed from commerce as we might like. By making us sensibly of this not-quite-analogy, of this trace of the port, with its networks of domestic and imperial commodities, Blake trains us to read the ambiance. He pushes “the metropolis,” the centralized city that Colquhoun understands as a joint venture, just out of frame. If we want to locate commerce or police in this scene, as Blake invites us to do, we have to look for it in the background. Queer, hazy sex is definitely on the table as a form of liberatory self-annihilation here, but the moment on the lily of Havilah does more than offer interpersonal love as a staging ground for political feeling or substitute pleasure for anti-police riot. It disrupts the spatial and temporal logic of the police.

The poem makes good on that implication when we learn, later in Chapter 2, how Jerusalem hides herself from Albion and the poem’s chief carceral forces, the Watch Fiends:

There is a Grain of Sand in Lambeth that Satan cannot findNor can his Watch Fiends find it: tis translucent & has many AnglesBut he who finds it will find Oothoons palace, for withinOpening into Beulah every angle is a lovely heavenBut should the Watch Fiends find it, they would call it SinAnd lay its Heavens & their inhabitants in blood of punishmentHere Jerusalem & Vala were hid in soft slumberous repose(37.15-21, E 183)

As stated, the Watch Fiends share with the Thames River Police a crushing standardization, “numbering every grain/Of sand on Earth every night.” The attempt to number every grain of sand reflects the rigid control of time that characterized industry and modernity, but the Watch Fiends also recall the end of custom and the Marine Police’s standardization of value vis-à-vis grains of sugar and fragments of coal. Meanwhile, Jerusalem and Vala’s “soft slumberous repose”—whose mushy sibilance resists the clean lines of this standardization and echoes the scene in which the two characters “assimilate into one”—grounds Blake’s resistance to carcerality in ambient, queer rest. Importantly, queerness here extends beyond the implied sex between two women, given the already-unstable nature of gender for Blake’s giant forms. The exchange between Jerusalem and Vala also sits queerly in relation to what I hesitate to call the poem’s plot, almost as a glitch in a larger arc that has them square off over Albion’s love and ends by pairing Jerusalem with Jesus and Vala with Albion. When the two characters repose together, Blake offers a moment of non-productive pleasure that hides its paradise on the smoky river of a policed city. Blake’s use of smoke as a trace of police presence and a source of resistance to surveillance paints a different portrait of Romantic urbanity. Rather than mining myths of an ideal past, his smoke poetics turns toward ecological catastrophe, and locates in the atmospheric and diffuse harm of pollution a figure for an urbanity that drifts and obscures without a clear structure.

5. Conclusions

When Sean Bonney writes in Our Death (2019) that “jails invent cities,” one jail that comes to mind is Newgate, a prison built into one of the old walls around which London expanded, and a prison about which Bonney writes extensively in Letters Against the Firmament (2015). Taking Bonney seriously, this paper has begun to consider how carceral culture shaped the limits of the city, its collectives, and its energy networks. Smoke poetics makes this collusion visible. It defamiliarizes and refashions the infrastructure of the city by docking a giant lily/queer crash pad/pocket of eternity alongside the merchant vessels and barges in the Thames. And Blake was not alone in turning the city against itself. During the trial of James Eyres, three witnesses testified that rioters broke the windows of the Marine police office with large stones, stones which the crowd seemed to have torn from the paved streets. Henry Lang, the police clerk, stated that “they destroyed the outside shutters, broke in the windows, and the stones came into the office, large paving-stones.” Richard Perry, a police officer, observed the windows destroyed by “large stones, I suppose twenty pounds weight, such stones as the streets were paved with,” and Gabriel Butterworth, a coal-heaver, testified that “I saw the prisoner at the bar throwing stones like pavement stones into the Police-office; by this time there were two or three of the windows broke open in the front of the street.” Though the Old Bailey records constitute a hostile archive, the image of paving stones, or stones like paving stones, conjures—and, indeed, seems calculated to conjure—the threat that the coal-heavers, by smashing the windows at the police office, were tearing the city apart. We would do well not only to study the poetic collectivities that emerge in the murky, discarded, or damaged, but to worry the edges of the abstraction that is “the city,” repurposing the urban against the police. I mean that Los Angeles is largely a concrete city, but there are paving stones on certain overpasses and on the medians of its boulevards. Whether these paving stones were twenty pounds or not, they cracked the windows of the police cruisers that had blocked anti-ICE protestors on the 101 freeway. Poems cannot riot, but they can offer test runs for unworking the spaces and collectives invented by jails, if we are willing to continue the experiment off the page.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created in this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 | For a larger history of police institutions in London, see (Harris 2004). |

| 2 | William Blake, Europe A Prophecy Copy K (c. 1821), Object 1. Accessed via The William Blake Archive. |

| 3 | Peter Fryer notes that the money went both ways, as wealth from the triangle trade funded the Welsh coal industry and the development of Boulton and Watt’s steam engine. (Fryer 2018). |

| 4 | For a discussion of linearity as a “civilizing” impulse in Romantic poems about London, see (Makdisi 2014), particularly chapter 1. |

| 5 | Colquhoun’s treatise supplies a useful account of wages and labor practices on the docks, and he notes that coal heavers earned 7–18 shillings a day (for 14 h of labor). He claims that this is a fair price, or at least that it sits above the average for workers on the docks, but he adds that due to the price-fixing of compulsory meals supplied by publicans (pub keepers) near the docks, coal heavers were coerced into spending extraordinary amounts of their pay on food and drink during work hours, such that their take-home dropped closer to 15 shillings a week. |

| 6 | Eyres was sentenced to death but ultimately transported to New South Wales, Australia. (“James Eyres” 2020). |

| 7 | (Short et al. 2010); “Can math and science help solve crimes? Scientists work with Los Angeles police to identify and analyze crime ‘hotspots,’” ScienceDaily, ScienceDaily, 27 February 2010; “Before the Bullet Hits the Body: Dismantling Predictive Policing in Los Angeles,” Stop LAPD Spying Coalition, 8 May 2018. |

| 8 | Several scholars have attended to queer elements in Blake. For elaboration on trans futurity and the body as “a site of transition” in Blake, see (Kim 2024); for analysis of “sexual categories” as a feature of fallen perception, see (Kroeber 1973). |

| 9 | See Copy E, Objects 6, 20, 26, 30, 35, 46, 50, 51, and 59, as well as Object 73, which directly inserts a setting sun onto the anvil in Los’ fiery forge. |

| 10 | For a view of the print without watercolor, I direct readers to Object 28 of Copy F (1827) of Jerusalem. For discussion of white-line etching in Jerusalem, see (Viscomi 2010). |

References

- Accum, Friedrich Christian. 1815. A Practical Treatise on Gas-Light, 2nd ed. London: Davies and Michael. [Google Scholar]

- “Alarming Riot”. 1798, Times, October 17, Accessed via the Burney archive.

- Bentham, Jeremy. 2018. Writings on Political Economy Volume III: Preventative Police. Edited by Michael Quinn. [Google Scholar]

- Blake, William. 1982. Jerusalem, the Emanation of the Giant Albion, the Complete Poetry and Prose of William Blake. Edited by Daniel V. Erdman. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bonney, Sean. 2019. Cancer: Poems after Katerina Gogou. In Our Death. Oakland: Commune Editions, p. 43. [Google Scholar]

- Clover, Joshua. 2016. Riot. Strike. Riot: The New Era of Uprisings. London: Verso. [Google Scholar]

- Colquhoun, Patrick. 1796. A Treatise on the Police of the Metropolis, Containing a Detail of the Various Crimes and Misdemeanors by Which Public and Private Property and Security Are, at Present, Injured and Endangered, and Suggesting Remedies for Their Prevention, 3rd ed. London: H. Fry, Publisher. [Google Scholar]

- Colquhoun, Patrick. 1800. A Treatise on the Commerce and Police of the River Thames: Containing an Historical View of the Trade of the Port of London; and Suggesting Means for Preventing the Depredations Thereon, by a Legislative System of River Police. London: Joseph Mawman, Publisher. [Google Scholar]

- Effinger, Elizabeth. 2020. Forgiving Blake’s Disaster: The Changing Face(s) of Science and ‘Govern-mentalized’ Bodies of Knowledge. In William Blake: Modernity and Disaster. Edited by Joel Faflak and Tilottama Rajan. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, pp. 172–93. [Google Scholar]

- Egan, Pierce. 1821. The True History of Tom and Jerry, or, Life in London. London: Charles Hindley. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott, Jake. 2024. Blake’s ‘Watchman’: Los and the London Police. European Romantic Review 35: 545–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairclough, Mary. 2013. The Romantic Crowd: Sympathy, Controversy and Print Culture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- “Fatal Affray at the Marine Police Office, Wapping”. 1798, Oracle, October 18, Accessed via the Burney archive.

- Ferber, Michael. 1985. The Social Vision of William Blake. Princeton: Princeton UP. [Google Scholar]

- Fryer, Peter. 2018. Staying Power: The History of Black People in Britain. London: Pluto Press, p. 16. [Google Scholar]

- Gurton-Wachter, Lily. 2016. Watchwords: Romanticism and the Poetics of Attention. Stanford: Stanford UP, p. 49. [Google Scholar]

- Hagan, Jade. 2020. Network Theory and Ecology in Blake’s Jerusalem. Blake Quarterly 53: 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, Andrew T. 2004. Policing the City Crime and Legal Authority in London, 1780–1840. Columbus: Ohio State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Joey S. 2024. ‘Humanity knows not of Sex’: William Blake’s Trans Futurity. Studies in Romanticism 63: 529–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- “James Eyres”. 2020, Digital Panopticon.

- “JAMES EYRES. Killing; Murder. 9th January 1799”. 2023, In The Proceedings of the Old Bailey. Sheffield: The Digital Humanities Institute.

- Jurema, Bernardo, and Elias Konig. 2023. Sketching a Theory of Fossil Imperialism. Hampton: The Hampton Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Kroeber, Karl. 1973. Delivering Jerusalem. In Blake’s Sublime Allegory: Essays on the Four Zoas, Milton, Jerusalem. Edited by Stuart Curran and Joseph Wittreich, Jr. Madison: U of Wisconsin P, pp. 360–61. [Google Scholar]

- Leveton, John Henry. 2022. Of ‘Combustion, blast, vapour, and cloud’: William Blake’s Urizen as Steam Engine, Albion Mill, & Notes Towards a Materialist Method for the Anthropocene. Essays in Romanticism 29: 131–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liboiron, Max. 2021. Pollution Is Colonialism. Durham: Duke UP. [Google Scholar]

- Linebaugh, Peter. 2014. Stop, Thief! The Commons, Enclosures, and Resistance. New York: PM Press. [Google Scholar]

- Linthicum, Kent. 2020. Rise of British Petroaesthetics in King Coal’s Levee. SEL Studies in English Literature 1500–1900 60: 739–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- “London”. 1798, Kentish Gazette, October 19, Accessed via the UK Newspaper archive.

- Makdisi, Saree. 2014. Making England Western: Occidentalism, Race, and Imperial Culture. Chicago: U. Chicago P. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolazzo, Sal. 2021. Vagrant Figures: Law, Literature, and the Origins of the Police. New Haven: Yale UP. [Google Scholar]

- Paley, Morton D., ed. 1991. William Blake’s Jerusalem: The Emanation of the Giant Albion. London: The Tate Gallery, pp. 130–31. [Google Scholar]

- Peterfreund, Stuart. 1997. The Din of the City in Blake’s Prophetic Books. English Literary History 64: 99–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, Nicolas. 1991. Policing the Poor in Eighteenth-Century London: The Vagrancy Laws and their Administration. Histoire Sociale/Social History 24: 127–47. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, Heidi C. M. 2018. Fuel: An Ecocritical History. London: Bloomsbury Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Short, Martin B., P. Jeffrey Brantingham, Andrea L. Bertozzi, and George E. Tita. 2010. Dissipation and displacement of hotspots in reaction-diffusion models of crime. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 107: 3961–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smil, Vaclav. 2017. Energy and Civilization: A History. Cambridge: MIT Press, pp. 229–33. [Google Scholar]

- Swift, Jonathan. 1973. A Description of the Morning. In The Writings of Jonathan Swift. Edited by Robert A Greenberg and William Bowman Piper. New York: W. W. Norton, p. 518. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, Edward P. 1977. Whigs and Hunters: The Origins of the Black Act. London: Penguin Books. [Google Scholar]

- Thorsheim, Peter. 2006. Inventing Pollution: Coal, Smoke, and Culture in Britain Since 1800. Athens: Ohio UP. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, Cass. 2022. Disposable World(s): Race and Commerce in Defoe’s Captain Singleton. The Eighteenth Century 63: 203–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viscomi, Joseph. 1993. “William Blake, Illuminated Books, and the Concept of Difference.”. Romantic Poetry: Recent Revisionary Criticism. [Google Scholar]

- Viscomi, Joseph. 2010. Blake’s Illuminated Word. In Art, Word and Image. Edited by John Dixon Hunt, David Lomas and Michael Corris. Chicago: U Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wordsworth, Dorothy. 1897. Recollections of a Tour Made in Scotland, A.D. 1803. In Journals of Dorothy Wordsworth, vol. 1. Edited by William Knight. New York: Macmillan, pp. 174–75. [Google Scholar]

- Wordsworth, William. 2008. Residence in London. In The Prelude. Edited by Stephen Gill. Oxford: Oxford UP, ll. 71. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, Julia. 2004. Blake Nationalism, and the Politics of Alienation. Athens: Ohio UP. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.