Abstract

The issue of environmental protection and nature conservation has gained global importance, and its solution requires not only scientific and technological efforts but also the education of an environmentally conscious and active young generation. Children’s literature serves as an effective means for this task. The article analyzes the eco-pedagogical potential of contemporary Ukrainian children’s literature through the prism of young eco-rebels. These characters inspire readers with their emotional power, eco-centric worldview, and bold resistance to environmental injustice. They contribute to the formation of ecological values in readers through emotional impact. Based on the ecocritical interpretation and typological comparison of Ghosts of Black Oak Wood by Bachynskyi and Taming of Kychera by Polyanko, we observe that the components of representation of the ecological topic are problematic eco-situation; behavior models, young eco-rebels’ actions and deeds; and eco-initiatives. The article further presents the results of ecocritical dialogues on environmental topics with 26 readers aged 14–15 (Ukraine). The methodology included interactive tools (e.g., Padlet) and surveys, which revealed that literary engagement promoted critical thinking, empathy, and personal eco-involvement. The findings confirm that children’s literature, when integrated with dialogic and participatory teaching methods, can serve as a powerful tool for shaping environmental literacy and civic responsibility in youth.

1. Introduction

The modern world faces various environmental challenges, crises, and disasters. The issue of environmental protection and nature conservation has gained global importance, and its solution requires not only scientific and technological efforts but also the education of an environmentally conscious and active young generation. As noted by N. Goga, L. Guanio-Uluru, B. O. Hallås, S. M. Høisæter, A. Nyrnes, and H. E. Rimmereide, “working to reconfigure the cultural and social environment remains important, since the cultural and social environment holds our potential collective respond-ability” (2023, p. 1430). Particular attention is given to family education, the education system, social culture, and other tools of influence on cognition, development, and personality formation of the child. Children’s literature, which has always responded to the child’s requests and needs, reflecting public views and problems, is also considered to be such a means: “These environmental texts for children can contribute to the ecopedagogical project and provide children with the information and the language that are necessary to become conscious ecocitizens” (van der Beek and Lehmann 2022, p. 141).

This study highlights the significant eco-pedagogical potential of children’s literature through the analysis of the novels Ghosts of Black Oak Wood (2022) by Andrii Bachynskyi and Taming of Kychera (2022) by Viktor Polyanko. By employing ecocritical, narrative, and receptive–aesthetic approaches, we define key components of ecological representation in these texts. We analyze the impact of reading and discussing literature on environmental topics on the development of readers’ environmental awareness and evaluate the effectiveness of ecocritical dialogues as a pedagogical method for developing empathy and active eco-engagement.

Ukrainian children’s environmental literature has its own tradition of development: “the discourse of nature in the literature for children of the 20th century demonstrates the path from the theme of nature to environmental issues” (Kumanska 2021, p. 11). This is illustrated, for example, by works about the Chernobyl disaster and its consequences for man and nature, which occurred after 1986 and became the object of an ecocritical interpretation (Vardanian 2022). In the 21st century, the depiction of eco-disasters and the promotion of the need to raise the level of environmental culture and awareness, as well as social responsibility, has deepened (the dystopia novels MOX NOX by T. Malyarchuk, the trilogy Through the Forest. By the sky, by the water by S. Oksenyk).

Goga et al., referring to the works of Garrard and Gifford, writes about two concepts of the image of nature (idyllic and problematic) and the need to identify them in the analysis “Nature might be considered a pure and harmonious place, as in the pastoral tradition”, or it can be “considered as problematic, a place where ecological imbalance, climate change, and the loss of species and plants reveal crises” (Goga et al. 2023, p. 1433). In contemporary Ukrainian children’s literature, the second concept of the image of nature prevails. Eco-situations related to the consumer attitude of man to nature or the consequences of political influence have become urgent plot-creating elements. Writers raise real environmental issues of modern Ukraine—cutting down forests, clogging rivers, building up mountains, and air, water, and soil pollution. The readers are urged to fight for the preservation of nature, to imitate the behavior of the main characters, who are often eco-rebels, and to encourage children to take responsible actions.

With the beginning of the Russian war in Ukraine, due to constant bombing and shelling of populated areas, environmental problems took on a significant scale, because a large number of toxic chemicals constantly enter the environment. The land is mined, fires in the forests and steppes, war crimes, such as the destruction of the Kakhovka Dam and the Kinburn Spit, etc., destroy the natural environment and cause terrible consequences for the ecosystem. The Ecodia Center for Environmental Initiatives monitors and records all ecocides, describes the impact of war on the climate of the planet (The Impact of the Russian War in Ukraine on the Climate 2024), and prepares interactive maps with cases of environmental damage (Cases of Potential Environmental Damage Caused by Russian Aggression. Interactive Map 2022). Environmental problems are briefly mentioned by writers who published works for children about the war during 2022–2024: My Forced Vacation by K. Yegorushkina, Oak Tree from War by H. Osadko, Saved Pets by N. Muzychenko, and Gerard the Partisan by I. Andrusyak, etc. (Kachak and Blyznyuk 2024).

The UGCC Bureau for Ecology, established in 2007, has published a series of illustrated prose and verse eco-tales for children aged 3–9, aiming at the formation of children’s responsible attitude towards the environment and its preservation, promotion of ecological–ecumenical dialogue, and initiation and development of environmental activities. Among them are O. Kobel’s stories about the hedgehog Gachok (Saved Forest, Defender of Purity (2023), Primroses (2020), Hedgehog-Rescuer (2019)), K. Yegorushkina’s Archie (2019), O. Skuldovatov’s Firefly and Windmill (2024), O. Rublyova’s Old Forest (2021), and I. Dzul’s Blue Treasure (2018).

Depending on the content emphasis and genre of the work and the recipients’ age, the authors highlight problematic eco-situations in different ways, demonstrate models of behavior of the heroes, and offer eco-initiatives and eco-perspectives. The ecological problem of saving nature is reinterpreted in the fairy tale Escape of Animals, or New Bestiary (2006) by Galyna Pagutyak. Ghosts of Black Oak Wood and Taming of Kychera are outlined against the background of the aforementioned eco-fairy tales and realistic adventure stories on environmental themes for children and teenagers. Here, the actions of the main characters, their ecological position, and eco-initiative are more clearly depicted, and the plots reveal environmental problems more deeply.

In this study, we analyze the eco-pedagogical potential of modern Ukrainian children’s literature through the prism of images of young eco-rebels. Similar to the experience of scientists who choose children’s literature on environmental topics of different countries as the object of analysis, justifying the specificity of the object by various geographical and geopolitical factors of influence on ecosituations (Aslam and Ashfaq 2023; Doughty et al. 2025; Gaard 2009; Goga 2018), we find it important to ensure the presence of the Ukrainian voice in the context of global research on children’s literature on environmental topics. Through our contribution, we hope to overcome the marginalization of the Ukrainian experience in the context of “recent post-colonial turn—in children’s literature studies as well as in Slavic studies”. As “if Ukraine has been long missing in the terrain of children’s literature studies, this is in part because its rich literary outpourings have been conventionally regarded as expressions of a ‘minor’ or ‘post Soviet’ nation of little relevance to Western scholarship” (Świetlicki and Ulanowicz 2025, p. 4)

The two novels in question, Ghosts of Black Oak Wood and Taming of Kychera, were selected based on their prominence and widespread recognition within Ukrainian literature for their exploration of ecological topics. In particular, they address such issues as deforestation, consumerist attitudes towards nature, and the overexploitation of natural resources. They reveal ecological problems in different ways, and more importantly, demonstrate vivid images of eco-rebels, and despite their popularity, have not yet been considered in the scientific discourse.

2. Theoretical Background: Ecocriticism and Environmental Literacy

The analysis of children’s literature, in which ecological themes and problems are raised, is usually carried out by scholars with the involvement of an ecocritical approach based on the research on “the study of the relationship between literature and the physical environment” (Glotfelty 1996, p. XXXVII). Ecocriticism, as “a wide range of interdisciplinary literary and cultural research methods to study the global environmental crisis through the intersection of literature, culture, and the physical environment” (Gladwin 2017), is actively used in theoretical and practical studies of children’s literature. This is testified in the collections Wild Things: Children’s Culture and Ecocriticism (Dobrin and Kidd 2004); Ecocritical Perspectives on Children’s Texts and Cultures (Goga et al. 2018); and Children’s Literatures, Cultures, and Pedagogies in the Anthropocene: Multidisciplinary Entanglements (Doughty et al. 2025). Together, the three books offer conceptual, pedagogical, and theoretical frameworks that help interpret Ukrainian eco-rebel characters not only as agents of resistance but as catalysts for readers’ eco-activity and as symbols of new, ethical modes of coexistence with the environment.

Key tasks of ecocriticism include rereading works from an eco-centric position. Particular attention is paid to writers in whose work nature plays the main role, to advocacy of eco-centric values, and to determining the significance of ecologically oriented text (Barry 1995). Ecocriticism is used as an ethical criticism and pedagogy that explores and finds the connection between the individual, society, nature, and the text. “Ecocriticism is the critical and pedagogical broadening of literary studies to include texts that deal with the nonhuman world and our relationship to it” (Cocinos 1994). Increasingly, the ecocritical approach is associated with consideration of children’s literature from the point of view of eco-pedagogical potential (Gaard 2009; Massey and Bradford 2011; Goga et al. 2023; Moriarty 2021; van der Beek and Lehmann 2022).

The results of studies of fiction and non-fiction books for children on environmental topics, published in different countries of the world, give an idea of “inclusion” and “exclusion” (van der Beek and Lehmann 2022, p. 145) of young readers into or from environmental situations and problems. These studies examine the influence of textual and visual representations of nature, as well as models of human interaction with it, on the development of eco-oriented values. They also explore how such literature fosters love and care for nature and motivates children to act in its preservation. Gaard, defining the functions of socially conscious ecological children’s literature, singles out three levels of the interaction model: unity and inclusion, hierarchy, and dominance (Gaard 2009). Van der Beek and Lehmann also consider this model. Their work provides valuable insights into how children’s environmental literature can shape young readers’ understanding of self and others in relation to ecological issues. In their analysis of children’s non-fiction books of the Netherlands, they “take into account depictions of the perceived self and the other in environmental texts for children and explore the representation of hierarchies between these categories” (van der Beek and Lehmann 2022, p. 145). The researchers discover that in “the selected books contrasting methods that push the reader away from the already abstract concept of climate change are used. They encourage the reader to see themselves as possible ‘eco-heroes’ and offer different strategies to help the immediate victims of climate change” (van der Beek and Lehmann 2022, p. 141). This approach not only fosters critical reflection but also empowers children by positioning them as active agents capable of making a difference, even within a global and often overwhelming environmental crisis.

Researchers Hints and Ostry (Hintz and Ostry 2003) emphasize the special impact on readers of utopian and dystopian works, which are considered political in nature. Such works, on the one hand, describe and problematize the ecological crisis, and on the other hand, popularize the images of “eco-rebels”.

Given this, children’s literature is a means of forming the young readers’ environmental literacy. In this context, we define the concept of environmental literacy as “a broad understanding of how people and societies relate to each other and to natural systems, and how they might do so sustainably” (Orr 1992, p. 92). Such a perspective emphasizes not only the interconnectedness between humans and nature but also the moral responsibility to preserve ecological balance, cultivate sustainable habits from an early age, and recognize one’s role as a participant in shaping the planet’s future. Furthermore, Orr expands the notion of ecological literacy by highlighting the importance of understanding the immediacy and scale of environmental challenges. As he asserts, another aspect of ecological literacy is “to know something of the speed of the crisis that is upon us. It is to know magnitudes, rates, and trends of population growth, species extinction, soil loss, deforestation, desertification, climate change, ozone depletion, resource exhaustion, air and water pollution, toxic and radioactive contamination, resource and energy use—in short, the vital signs of the planet and its ecosystems” (1992, p. 93). From this perspective, ecological literacy becomes not merely a matter of factual knowledge but a critical awareness that enables responsible action in the face of global environmental collapse.

3. Ghosts of Black Oak Wood and Taming of Kychera: Eco-Rebels and Eco-Pedagogical Potential

Andrii Bachynskyi and Viktor Polyanko are contemporary Ukrainian writers who write for children mainly in the adventure genre. Bachynskyi’s literary output includes more than ten books, among them The Incredible Adventures of Ostap and Darynka (2010), 140 Decibels of Silence (2015), Detectives from Artek. Secrets of the Stone Graves (2017), A Bunch of Cheerful Tramps (2014), With Einstein in a Backpack (2019), Triangle of Zeus (2020), and Ghosts of Black Oak Wood (2022). His works are informative, in which reality is often intertwined with fiction, fairy tales, myths, and legends. The author uses motifs of travel in time and space as well as historical ones (Kachak and Blyznyuk 2025, p. 186), raises the question of usefulness of sciences (physics, geometry), and actualizes the problems of modern Ukrainian society in realistic adventure stories (ecological, social, moral, and ethical). Ghosts of Black Oak Wood is an adventure story on an environmental theme, which won the BBC Book of the Year 2022 literary award in the “Children’s Book of the Year category BBC”.

Polyanko is a mathematician by education and an IT specialist who travels around Ukraine, goes on mountain hikes with his family, takes photos, and writes about it on his blog. He is the author of adventure books for children such as Taming of Kychera (2022), Slobozhansk Atlantis (2024), and the short story collection Hrytsko Trabljuk’ trouble (2024). He raised the environmental theme in the story Taming of Kychera, which was awarded the prize for the competition “Children’s Coronation of the Word”.

The adventure stories Ghosts of Black Oak Wood and Taming of Kychera (Figure 1) engage the reader with a dynamic plot full of danger, mysteries, and brave actions of the heroes. The environmental theme here is naturally combined with the elements of the adventure genre. The characters join in the fight for the preservation of nature, facing challenges that force them to show ingenuity, courage, and perseverance. However, if the plot of the first work is built on the solution of the environmental issue by the young heroes, then in the second work, the environmental problem is not the basis of the adventure quest, but is just slightly unfolded.

Figure 1.

Ghosts of Black Oak Wood by A. Bachynskyi and Taming of Kychera by V. Polyanko.

3.1. Ecological Topics and Images of Eco-Rebels in the Adventure Novels Ghosts of Black Oak Wood by Andrii Bachynskyi and Taming of Kychera by Viktor Polyanko

The ecological problem of deforestation and the destruction of nature is the basis of Ghosts of Black Oak Wood. The traditional “summer holidays” story, which should have been about rural recreation and Roman’s vacation, turns into a real struggle of teenagers against the cutting down of the Black Oak Wood. Foreigners want to cut down the forest near the village and destroy the river, promising the local residents swimming pools and water parks. In order to realize their plans, they use political leverage and intimidation and offer material benefits to those who will facilitate illegal logging. Local residents keep silent because they do not believe that they have enough power to resist this. Only Roman and his friends show the courage to stand up and begin to act in order to stop the big felling. They are supported by Roman’s grandfather, who returned to his native land after many years of travelling around the world. He talks about Sun Tzu’s art of war strategy and teaches children how to act correctly to defeat a stronger enemy.

Roman is an eco-rebel who fights for the preservation of nature and demonstrates responsibility for the environment. He does not immediately believe that “some bandits decided to cut down the forest, and the whole village is silent and cannot give them advice” (Bachynskyi 2022, p. 30). He seeks to change society’s attitude towards nature, often acts contrary to established norms, and, together with his friends, even breaks the rules for the sake of saving the environment. The boy has a strong sense of justice, seeks to protect nature, even if it means confronting adults who are indifferent to environmental pollution (“If we don’t at least try, then who will save the forest?” (Bachynskyi 2022, p. 57)). He perceives the protection of nature as a personal mission and is ready to act radically in order to draw attention to the environmental problem and solve it.

His beliefs, life position, and behavior form the role-model type of character—an eco-rebel who is characterized by the following traits:

- Plays an active role in solving environmental problems.

- Opposition to the established social order and rebellion against environmental crimes.

- Willingness to risk one’s own well-being for the sake of nature.

- Formation of one’s own worldview and value system based on eco-centrism.

Roman’s eco-centric ideas fascinate his friends. The protagonist talks about school eco-camps and eco-initiatives. The activities of eco-rebels are manifested in organizing protests, using methods available to them (scaring loggers with ghosts, spoiling their tools, and digging up the road so that trees cannot be removed). They try to draw attention to the problem of the destruction of the Black Oak Wood to other members of the community and to convince them that the preservation of nature is far more important than the promised short-term material benefits. They rebel against the illegal actions of loggers and the clogging of the river, and independently (without the permission of adults) send an official request to the Ministry of Environmental Protection and Natural Resources to check the legality of this felling. The children understand that it is dangerous to deal with criminals, but they do not give up their struggle.

Bachynskyi raises the topic of environmental awareness, civic activity, and responsibility for the environment. It shows how the young generation, through its activity, can be an example for others to stand up for the protection of nature, teach them to appreciate what they have, and fight for their future. For the inhabitants of the village, Black Oak Wood is not only nature, but also culture and historical memory, a connection to the past and ecological security in the future.

However, the author admitted that he was surprised by the success of his book (BBC-2022 award) in the midst of the war, and said that he would write it differently now, because the war brought devastating harm to nature. He claimed: “... but after the victory, when there is an assessment of everything lost and damaged, I think that the consequences for the ecology—we will simply be scared to count all that. And what is happening in the sea, how thousands of Black Sea dolphins are dying, and what is being done to forests and fields that are mined. It is unknown how many of them need demining, and in general, with this ecosystem, fauna, flora of Ukraine—this is for decades … ” (Petsa 2022).

Another example of eco-activity is Polyanko’s story Taming of Kychera (Kychera is the name of a mountain peak). Its plot unfolds on the basis of a series of adventures of a young family that goes to the mountains for the tenth birthday of their son Myroslav. As N. Marchenko rightly noted, the adventurous character of the work ensures the dynamic development of the plot, where an everyday journey “turns into a real cinematic quest in which history and mysticism, political and personal secrets, ecology of the environment and spirit are intertwined” (Marchenko 2023). The story is told by Myroslav himself. He responds negatively to the news about going on a camping trip, but when his dad provides him with a map and a compass, he becomes interested.

Even more appealing for readers is the USSR underground city—Uzhhorod 61, built in the mountain as a secret military base and evacuated in 1991, when Ukraine regained its independence. During the campaign, the family also discovers the hiding place of UPA (Ukrainian Partisan Army, which fought for independence). The author touches on historical issues related to the totalitarian regime, a country in which ecology was neglected, chemical and nuclear weapons were manufactured, aimed at the destruction of man and nature. It is Kateryna, a descendant of a Russian KGB agent (Committee for State Security—the main security agency of the Soviet Union from 1954 to 1991), who hires loggers to illegally cut down the forest and destroy the Carpathians. She is trying to take revenge on the Ukrainians for taking the Carpathians from the Russians. She is sure that soon everyone will read “Obituary of the Carpathian Forests” (Polyanko 2022, p. 191) because local residents are ready to carry out criminal orders for a penny, destroying the nature in which they live. This indicates a low level of ecological culture; the author tries to show this against the background of the lack of material goods and financial opportunities in the community.

Myroslav does not reveal his own eco-initiatives, but together with his father, they support the mother’s position to investigate illegal logging. The work describes the ecological disaster caused by cutting down forests in the mountains: “a wasteland that at first seemed small, opened up on the mountainside in all its glory: it seemed as if a large sloping stadium had been erected in the middle of the forest, and it was filled with immeasurably already dried long trees” (Polyanko 2022, p. 109); “these sawmill maniacs bare the slopes and then the rains wash away the unprotected soil and part of the surrounding forest dies” (Polyanko 2022, p. 109). Thus, Myroslav becomes worried, as on a hike, he realizes not only the beauty, but the importance of preserving nature.

With the image of Myroslav, the writer shows the change in the child’s attitude towards the surrounding world, nature, and value priorities. During the hike, the boy begins to admire the beauty of the mountains and states, “It is here where I received the greatest gift. Not even that I received it, but exchanged—a piece of my heart remained in the Carpathians, and a tiny piece of the mountains settled deeply inside of me” (Polyanko 2022, p. 224).

The two novels follow the tradition of children’s literature in being “optimistic, with happy endings” (Nodelman 2000, p. 1). Although such positive finals are now less prevalent in contemporary children’s fiction than they once were (Meek 2004, p. 8), they retain the same structure. In Bachynskyi’s narrative, the local community takes responsibility for environmental restoration: “The Black Oak Wood was preserved. At the community meeting in the cultural center, the residents agreed that immediately after the harvest they would gather in the forest to clear it up after those poachers, and later plant young trees in the place of the felled ones” (Bachynskyi 2022, p. 168). Eventually, “The Black Oak Wood was declared a nature reserve and from now on it is under the protection of the state” (Bachynskyi 2022, p. 171). This resolution emphasizes the affirmation of ecological values and conveys a hopeful message of change and renewal.

A similar solution to the ecoproblem is also found in Polyanko’s story. Kateryna’s sister, who works in a state organization for reforestation, promises to plant new trees at the site of felled trees on Mount Kychera in the Carpathians. However, all these do not happen as quickly in reality, because not only are trees cut down, but the entire ecosystem is destroyed. It is in the happy ending that Bradford (2003) sees the problem and the impossibility of truthfully covering certain environmental issues in children’s fiction books, for example, telling a story about climate change that ends happily. Fiction books are good at describing environmental crises, but “weak on promoting political agendas or collective action” (Bradford 2003, p. 116). The researcher argues that, in fact, as evidenced by the metanarratives circulating in Western culture, environmental themes very rarely have happy endings and are often apocalyptic in their depictions of environmental consequences (Bradford 2003). Van der Beek and Lehmann also doubt the ideality of fictitious narratives as a means of ecological progress (van der Beek and Lehmann 2022, p. 146).

Comparing these two adventure stories, we note that in the work by Bachynskyi, the eco-initiative comes from children. It is supported and completed by adults, while in the work by Polyanko, the eco-initiative comes from adults—parents—who then involve their own children. These are two models of eco-rebellion and the involvement of children in eco-activities. Considering the fact that adults are involved in both stories, we conclude that children can be involved in solving environmental problems. They are eco-active, but at this stage of their lives, they are not independent. However, using the example of the actions of the eco-rebel Roman and his friends in Bachynskyi’s novel, we can see that not all eco-activities of children are “too marginal to be effective”, as stated by van der Beek and Lehmann (2022). However, we agree that children are involved in eco-initiatives, but the main agents of change are still adults because “a child needs the mediation of an adult so that other adults can hear him” (van der Beek and Lehmann 2022, p. 159). Such narratives are a reflection of social reality. A realistic type of plot cannot ignore this fact, even if the work is written in the adventure genre using elements of fiction, while in the works of the fantasy genre, dystopias, young heroes can be left alone with an eco-problem or fight together with their peers without adults’ involvement.

3.2. Works on Ecological Topics as an Eco-Pedagogical Means

The images of eco-rebels become one of the key receptive codes through which the eco-pedagogical potential of ecological children’s literature, in particular adventure and dystopian novels, is realized. Protagonists who are imagined and identified with by different types of readers, including hero readers and critical thinkers (according to Appleyard’s theory) (Appleyard 1991), are a source of new ecological experiences of the child, emotionally affect ideas about eco-activity, and often become a motivational factor for environmental behavior.

Through analysis of the works by Bachynskyi and Polyanko, we highlight other plot elements, techniques, and expressive means of receptive poetics, which help the author to not only transform into the consciousness of the recipient artistic meanings that generate certain aesthetic emotions and call for eco-activity, but also form children-readers’ ecological literacy.

The text components have an eco-pedagogical impact on the reader. Firstly, this information forms knowledge about environmental problems (situations, crises, disasters) and their consequences. Despite the fact that this component is much stronger and more widely represented in non-fiction texts (van der Beek and Lehmann 2022), in adventure and dystopian works, it has no less impact on readers, and perhaps even more, because it often encourages them to find more information on their own. These are those logical arguments, “factual knowledge about the world” (van der Beek and Lehmann 2022, p. 146) that are reinforced in works of art by emotional arguments (figurative language, an example of eco-activity of others, stories about ecoculture in other nations, “arguments to fear” in dystopias) and become a powerful tool of persuasion (according to the laws of rhetoric) in the communication between the writer and the reader through the text. “Stimulating stories in fiction books”—whose eco-pedagogical potential has not received significant attention from R. Monhard and L. Monhard (Monhardt and Monhardt 2000) and van der Beek and Lehmann (2022)—should be an integral part of the educational model for developing children’s ecological literacy, alongside the common knowledge about the world provided in non-fiction books. Moreover, as the analysis of the works proves, there is a lot of scientifically confirmed, factual information about nature, ecosystems, eco-crises, their causes, and consequences, etc., in adventure stories and in dystopian novels.

Bachynskyi writes about the harmfulness of burning grass, the consequences of the destruction of the ecosystem as a result of the felling of timber, and about environmental problems as a result of corruption schemes. Polyanko raises the issue of the destruction of nature by poachers. Under the guise of sanitary cleaning of the forest, a large number of healthy trees are destroyed. Myroslav’s mother calls loggers poachers, “cold-blooded killers of the lungs of the planet” (Polyanko 2022, p. 112). She ignores their words about the availability of all permits, and is going to call the police, demonstrating not tolerance, but a conscious environmental and civil position.

In Bachynskyi’s story, grandfather Andrii talks about the eco-culture of other peoples: “The Chinese don’t have such forests, that’s why they respect every tree” (Bachynskyi 2022, p. 34). Grandfather shares with his grandson the knowledge that “one mature oak produces oxygen for eight people in a year (Bachynskyi 2022, p. 35)”. He speaks about the growth of the tree and the formation of the rings, emphasizing that the oaks from the Black Oak Wood are 300 years old, and various family memories are also associated with them (Bachynskyi 2022, p. 35).

Polyanko delves into history, uses political subtext, and writes about the town “Uzhhorod 61”. In the underground city, Myroslav is interested in the lighting and ventilation system, the effect of psychotropic substances that were injected into the ventilation system “to block the emotions of people who had to live in the underground city” (Polyanko 2022, p. 139). Myroslav knows that the totalitarian system made these people the “living dead”, real zombies, and perceives the creation of chemical weapons as a threat to the entire planet. He explains this on the example of a virtual game: “If our planet is a giant toy, then a cheat virus was made in this laboratory” (Polyanko 2022, p. 100).

Therefore, it is worth highlighting eco-initiatives and examples of eco-active behavior, values of the main characters, eco-rebels, which can be both a role model for readers of the same age, and factors for the development of their own eco-ideas and eco-initiatives. Writers show that children can also influence the ecological situation and be drivers of progress in the development of social ecological culture.

Roman is involved in an environmental group, whose members, under the influence of volunteer activists of the environmental movement from Austria, organize an ecocamp to clean the banks of mountain rivers of garbage and show local residents a good example (Bachynskyi 2022, p. 24). He urges friends to resist the loggers and prevent them from using the tractor for digging the road on which the lumber trucks transport wood (Bachynskyi 2022, p. 59).

Involving children in collecting cones for seeds to plant a new forest is mentioned in the story (Bachynskyi 2022, p. 65). Children collected fruits to get money, cleaned up the river to make it suitable for swimming, and built a sports ground next to it (Bachynskyi 2022, p. 169).

The impact of the images of eco-rebels on readers occurs through the possibility of self-identification of the recipient, involvement in solving eco-situations similar to those described in the texts, awareness of the importance of active interaction with nature, and practicing eco-centric behavior. The level of eco-activity and involvement of the reader in the problem described in children’s literature depends not only on the content, genre parameters of the work, images of characters, “on the inner textual projection, the author’s intentions, ability to predict the model reader and ‘create competence’” (Kachak et al. 2022, p. 81), but also on the type of the narrative. It is believed that the child narrator helps children-readers to better position themselves in relation to the text, because the reader is on the same level as the peer-hero (Skjønsberg 1985). Moriarty (2021) writes about the effectiveness of the form of the hero’s story as an eco-pedagogical tool. This theory also works with regard to the reading of Polyanko’s work. Myroslav is the narrator. He does not show eco-rebellious behavior, but changes his attitude towards nature, supports the eco-initiatives of adults, and realizes the importance of eco-centric behavior. He is fascinated by adventure. Similarly, readers identifying themselves with narrators of the same age are more concerned with their adventure quests, while environmental issues appear secondary and do not actually receive the dynamics of development. This indicates that both the type of narrative and the position and model of the hero’s behavior are criteria for attracting readers. Bachynskyi tells the story in the third person, but the eco-activism and eco-rebellious behavior of Roman and his friends are, in our opinion, the best means of engaging readers in environmental issues and contributing to their self-identification in this context as eco-conscious citizens ready to actively act to preserve nature and prevent an eco-crisis. In addition, Bachynskyi’s story emphasizes the importance of collective actions in this process, changes in public thinking, and attitudes towards ecology.

As evidenced, although children do not act as narrators, the reader’s level of interest and trust in these texts is determined by the narrator’s position and point of view (the way of speaking about the subject), from which the events and situations in the artistic work are presented. Readers see the events that are happening with Roman and his friends precisely from their perspective. The dialogues and thoughts of the characters reinforce this point of view. Reflecting on the narrative, M. Nikolajeva (2004) claims that a text for children is built in a dialogic tension between two unequal subjectivities: an adult author and a child character. Narratology distinguishes between narrative voice and point of view. In children’s literature, they rarely coincide, even if the narrator is a child and the story is told in the first person. The voice, as a rule, belongs to the adult, and the perspective to the child. After all, “reading the content, imagining and emotionally experiencing the depicted events, the child-reader takes a special position in relation to the hero of the work” (Kachak 2018); characters become authoritative in the text.

4. Methodology

We proposed reading the adventure novels Ghosts of Black Oak Wood and Taming of Kychera to school children to assess how these texts impact the development of students’ environmental competence and eco-activity. To discuss the works with readers, we chose the method of ecocritical dialogues proposed by Goga et al. “Ecocritical dialogues respond to the calls of educationally oriented political documents and combine the theoretical concepts of ecocriticism and dialogic teaching for the development of ecocritical dialogue within the framework of pedagogical education” (Goga et al. 2023, p. 1432). We also tried to use the Nature in Culture Matrix, which works as a schematic overview of main positions within ecocritical discourses (Goga et al. 2018).

In order to determine the eco-pedagogical potential of literature and its influence on the formation of children’s ecological literacy through the transmission of facts about nature, human interaction with the environment, knowledge about ecological problems, eco-crises, eco-catastrophes, their causes and consequences, as well as the description of eco-initiatives and eco-active behavior of the heroes, a survey was conducted and books on environmental topics were read and discussed with readers. The survey was conducted in Google Forms, and prior approval for using the data in generalizations of the research and publication of the results was received from parents and the students themselves.

A total of 26 student readers aged 14–15 from schools in Ivano-Frankivsk city, who attend the local library, took part in the book discussion. Before the beginning of the process, the children were given a survey “Books and the environmental topic”. Two meetings were arranged, each of which was devoted to discussing a book by a particular author, and eventually, the final survey “Eco-rebels, environmental literature and my eco-position” was conducted. The surveys were specifically designed for this project to explore students’ attitudes toward environmental literature and their personal ecological views.

The first survey contained questions that allowed us to determine how often school children come across environmental topics in the literature, which eco-situations interest them, and how these affect their behaviors.

- Have you ever read books that deal with environmental issues?

- What eco-situations have you encountered in the books you read?

- How do texts and conversations on environmental topics affect you?

- Do you discuss environmental issues as part of studying school subjects?

- Name the books you have read which raised environmental problems.

The questions included in the initial survey were carefully selected to align with the study’s objectives, which aimed to explore students’ engagement with environmental themes in the literature, their emotional and behavioral responses, and the integration of ecological issues in the educational process.

In conclusion, reading and discussion of works on ecological themes were carried out using ecocritical dialogues (Goga et al. 2023). Young readers were invited to discuss the novels they had read before Ghosts of Black Oak Wood and Taming of Kychera, and guiding questions were provided for this purpose (Appendix A). Building up a conversation about each novel, we created a chain of dialogues, at first working in three microgroups, and then collectively; in this way, we provided the “dialogic space of experience that includes different perspectives and voices” envisioned by Goga et al. Together, using interactive methods of brainstorming and critical, associative, and creative thinking, we created a dialogic space for reflection on the read piece of work, studied the actions and deeds of eco-heroes, and projected them onto our own life experiences.

The analysis focused on the depiction of environmental disasters in the selected texts, the protagonists’ responses to these events, and their relevance to real-world ecological issues. During the ecocritical dialogues, participants were encouraged to reflect on these topics, propose potential eco-initiatives, and voice their views on the importance of active environmental engagement and personal responsibility. They continued to think about solving environmental problems in order to understand which position in the ecological discourse is taken by everyone. In the process of critical understanding of the read text, readers not only acquire new eco-knowledge and search for their own eco-initiatives, but also realize individual and collective eco-responsibility that is formed, and thus, the level of eco-awareness increases.

A particular emphasis of such a dialogical understanding of texts is the implementation of an activity approach, which provides for the involvement of students in active participation in the learning process through practical tasks and projects. This contributes to the development of critical thinking, cooperation skills, and the ability to apply knowledge in practice. Therefore, at the end of the meetings devoted to the discussion of each book, the readers jointly came up with ideas for a project aimed at solving or preventing eco-crises similar to the ones described at the local level, taking into account the specifics of the region and current times.

Recommendations proposed by Goga et al. related to the place of ecocritical dialogues, participants, approaches, and topics were taken into account. The meetings were held in the library, where students from different schools had memberships. Before the beginning of each discussion, the readers were reminded that “the dialogic form presupposes that participants’ utterances are linked together in chains of answers and new utterances” (Goga et al. 2023, p. 1438). To capture the participants’ opinions, we used a tool, Padlet, in which each microgroup recorded the key components of their communication chains.

At the last meeting with the readers, we surveyed them to find out how the books they read influenced them and whether the actions of eco-rebels motivated them to get involved in eco-activities. The survey “Eco-rebels, environmental literature and my eco-position” contained several closed and open-ended questions:

- Which eco-situations have you encountered in the books you read?

- Name the books you have read which raised environmental problems.

- Are you aware of the consequences of ecosystem destruction caused by human activities?

- Do you approve of the eco-rebellious behavior of the characters in the books you have read?

- Which eco-rebel character’s behavior appeals to you the most? Do you identify yourself with any of them?

- Do you have any ideas for eco-initiatives inspired by the characters in environmental fiction?

- If so, write down these ideas.

- Have the books and the eco-dialogues you read changed your attitude towards nature?

- What is your position on the environment?

- Was the experience of the ecodialogues positive for you?

Closed-ended questions 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 9, and 10 offered predefined response options (including multiple-choice and Likert-type scales), enabling the identification of trends in students’ awareness, attitudes, and behavioral intentions regarding environmental issues. Questions 2 and 7 were open-ended, allowing students to list environmental books they have read and suggest eco-initiatives inspired by fictional characters. The open responses provided deeper insights into readers’ literary experiences and personal reflections on ecological engagement.

5. Results and Discussion

The images of young eco-rebels are fascinating, with eco-initiatives and models of active eco-positioning, examples of manifestations of eco-awareness. These are real stories about growing up, responsibility, and protecting the environment, which, although they contain fictional elements, clearly convey the importance of people’s eco-awareness and eco-activity. Such stories not only captivate but also make you think about current environmental issues, combining entertaining reading with critical reading and awareness of an important social message.

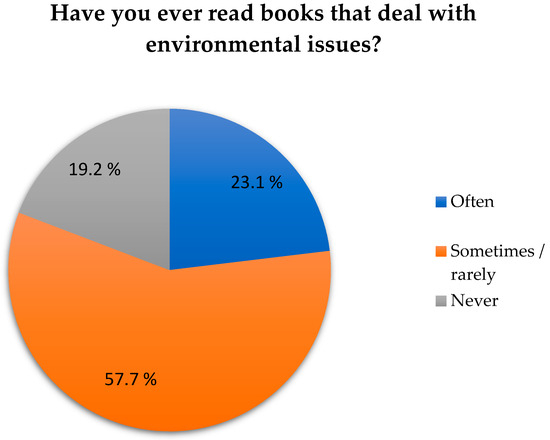

In the first survey “Books and the environmental topic”, 15 of the 26 respondents (57.7%) said they did not often encounter such books, 5 (19.2%) mentioned that they did not find these topics in the books they read, and 6 (23.1%) answered that they often encountered environmental issues in the literature. This indicates a low level of inclusion of environmental topics in the works that students learn in the course of their studies (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Inclusion of environmental themes in students’ study materials.

Among the most common environmental situations students read about in books were climate change and its consequences for nature and people (17; 65.4%), rivers, seas and ocean pollution (18; 69.2%), deforestation and destruction of natural resources (13; 50%), eco-catastrophes due to social actions, such as war (10; 38.5%), and apocalypse due to environmental problems (mainly in fantastic, dystopian texts) (8; 30.8%).

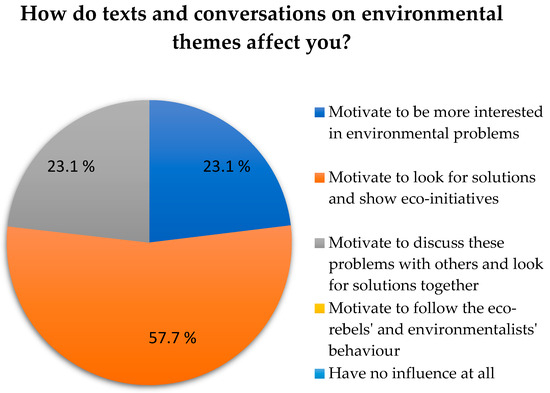

Analyzing the results on the influence of environmental literature on children, 14 respondents (53.8%) noted that environmental issues motivate them to find solutions and to show eco-initiatives, particularly in the context of the need to preserve nature and actively search for solutions to eliminate environmental issues; six respondents (23.1%) claimed that environmental topics inspire them to talk with others and make mutual efforts to find solutions; and six students (23.1%) mentioned that works on environmental topics raise their interest in environmental issues. However, no one chose the option for motivation to emulate the behaviors of eco-rebels (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Influence of environmental literature on children.

The answers showed that environmental issues are often discussed in various school subjects. A total of 22 respondents (84.6%) confirmed that such discussions take place on a regular basis, especially during natural science and geography lessons; 4 respondents (15.4%) answered that topics are not often raised during the study of school subjects.

Many respondents could not list the exact names of books in which environmental issues were raised, but claimed they often noticed those topics in the literature, such as fairy tales and short stories. Some respondents mentioned specific works that were important to them in the context of ecology. For instance, Ghosts of Black Oak Wood by Bachynskyi and Real Monsters—Threat to the Planet by G. Rode. Others mentioned titles such as How to help a hedgehog and protect a polar bear by J. French and A. Kogan, and Kosia the Bunny’s Adventures by L. Kravchenko. These books use natural images to foster compassion for animals and nature in children. Mentions of the books Oak from War by H. Osadko and Tiny Creatures by E. Barzotti also testify to the presence of fiction and non-fiction for children on the topics of ecology and human interaction with nature. Such books can be useful for expanding children’s horizons and developing responsibility for the future of the planet.

Overall, it can be concluded that environmental topics are important and interesting for most students, which is confirmed not only by the high frequency of their mention in the literature but also by their influence on children’s behavior. At the same time, there remains potential for in-depth discussion of environmental issues in lessons and activation of eco-initiatives among students, which will contribute to the development of environmental literacy and social responsibility in the younger generation. As stated in UNESCO’s “Education for Sustainable Development Goals: Learning Objectives”, “education for sustainable development aims to “empower learners to take informed decisions and responsible actions for environmental integrity, economic viability and a just society, for present and future generations “(Education for Sustainable Development Goals: Learning Objectives 2017, p. 7).

Ecodialogues based on the suggested books allowed the participants to understand the impact of human actions on the environment and to think about how attitudes towards nature reflect the inner beliefs of the individual. The discussion focused on the analysis of the actions of the heroes, who demonstrate a responsible or irresponsible attitude towards nature. Children were asked how they themselves would act in similar situations. Special attention was paid to environmental problems, ecocatastrophes depicted in the works, and the main characters’ reactions to them. Points related to nature conservation and saving the environment were discussed, and parallels with current environmental problems in the modern world were drawn. The readers reflected on possible eco-initiatives and measures to solve such problems, emphasizing the need for action and environmental awareness.

The discussion included the issue of eco-rebellion as a form of active environmental position. The participants shared their opinions about which of the heroes could be called an eco-rebel, and which actions and motives distinguished such behavior from the usual attitude towards nature. Questions were raised about the willingness of people to go against the usual norms for the sake of protecting the environment. This helped them to think more deeply about the possibilities of active actions in one’s own life and to find examples of such manifestations in the community. The final parts of the discussion touched on the personal views of the participants regarding nature protection and the inspiration that the works might provide for specific eco-initiatives. Some of the ecocritical dialogues generated during the discussion of the books were posted on Padlet boards (Ecodialogues 1. 2024; Ecodialogues 2. 2024).

Analysis of the responses of the 26 readers on the survey “Eco-rebels, environmental literature and my eco-position” shows a significant interest in and understanding of environmental issues, as well as an increase in environmental awareness among the survey participants. All the respondents mentioned that they encountered various environmental situations in the books, including climate change, deforestation, water pollution, biodiversity loss, and other environmental disasters caused by human activities. In particular, such works as Taming of Kychera, Ghosts of Black Oak Wood, and Through the Forest. By the Sky, by the Water were mentioned as raising important environmental issues and showing the impact of human activity on the environment.

The respondents stated that they were familiar with the consequences of the destruction of ecosystems due to human activities. The answers showed support for the eco-rebellious behavior of the characters in the books; they approved of the main characters’ actions in Taming of Kychera, as well as those in Ghosts of Black Oak Wood. This suggests that heroes fighting for the preservation of nature are sympathetic and provide role models for readers.

As for identification with eco-rebel heroes, many respondents noted that they associated themselves with those characters who actively protected nature. Roman, who fights injustice and protects nature, has become a model of eco-activism for many. Moreover, characters in Ghosts of Black Oak Wood have been named as those whose behavior reflects a desire to change the situation for the better.

Regarding the idea of eco-initiatives, the respondents named several directions in which they would like to focus, following examples from the works they read. Responses included organizing actions to clean up forests and water bodies, planting trees, landscaping, reducing pollution, and recycling waste.

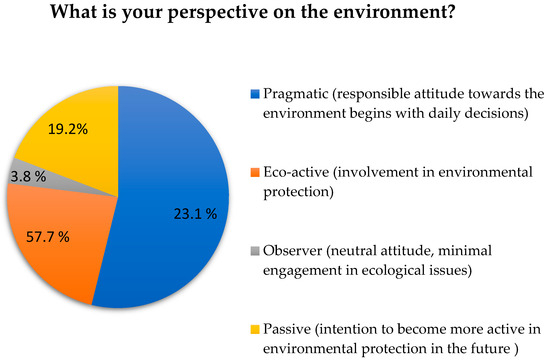

The students were asked to determine their position on the environment. The following answer options were offered: eco-active (I do everything possible to preserve the environment); pragmatic-ecological (A responsible attitude towards the environment begins with daily decisions, there is a balance between comfort and ecology); observer position (I understand the need for change and take interest in ecological situations, but I am not yet involved in preventing or solving them); eco-passive (Although I do not make big difference here yet, I consider the possibility of doing something more to preserve nature in the future); eco-skeptical (I believe that large corporations bear more responsibility for changes than separate individuals); other.

According to the analysis of the answers about the participants’ position regarding the environment, the majority (14; 53.8%) took a pragmatic environmental vision, which indicates a tendency to combine ecological principles with comfort in everyday life; six respondents (23.1%) were ready to demonstrate eco-activity by caring for the environment. However, five students (19.2%) were considering the possibility of impacting environmental issues in the future. Only one person (3.8%) showed a passive view or was an observer (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Participants’ attitude regarding the environment.

Reading books and participating in ecodialogues significantly expanded the participants’ ecological knowledge, helping them to better understand current environmental problems and form new attitudes toward nature. The answers indicate that most respondents felt more responsible for the environment and are ready for changes in everyday life. Students also noted that their views have become more pragmatic and balanced, particularly regarding small but important steps towards a caring attitude towards the environment.

Concerning the evaluation of ecodialogues as a method of discussing environmental issues based on books read on ecological topics, the majority of respondents gave the highest rating. This indicates that ecodialogues have become an effective tool for the participants to gain a deeper understanding of environmental topics and discuss problems and initiatives. Overall, the experiences from such discussions were positive, as they helped the participants to raise environmental awareness and get involved in eco-activism.

The study showed that the environmental theme, which unfolds in contemporary Ukrainian children’s literature, not only diversifies the content of the works but also has a significant potential for education on socially significant values; in particular, readers’ awareness of the need to preserve nature and protect the environment. An important role is played by the heroes of eco-rebel children, who catch readers’ attention with their behavior and life position, and encourage eco-activity.

Ecocritical analysis of the novels Ghosts of Black Oak Wood and Taming of Kychera demonstrates how Ukrainian authors, through the prism of the adventure genre, illuminate problematic eco-situations, the consumer attitudes of man toward nature, create models of behavior of young eco-rebels, and involve children-readers in understanding environmental problems, supporting eco-initiatives. A typological comparison of these works indicates that the eco-pedagogical potential of the text depends on many factors: which hero is central in the story, how the plot unfolds, whether it is built on solving an ecological problem or whether the ecological issue is secondary, who the narrator is, what narrative view the author chooses, which eco-initiatives are shown by the heroes and how relevant they are in the modern world.

In accordance with previous studies (Goga et al. 2023; Massey and Bradford 2011; van der Beek and Lehmann 2022), the results of this study proved that works on environmental topics are effective pedagogical tools for the formation of children’s eco-activity and environmental literacy. The overview of plot development and the analysis of the characters’ behavior demonstrate that these works offer environmental knowledge, are a source of new ecological experience for children, and help form eco-activity and ecoculture skills necessary to respond to environmental challenges and prevent eco-crises.

The method of ecocritical dialogues proposed by Goga et al. was efficient when discussing books on environmental topics with young readers. This is confirmed by the results of the survey.

Considering the obvious advantages of using literature in general and the image of eco-rebels in particular as an eco-pedagogical tool, and taking into account the results of the study, we emphasize the need to include other methods of developing environmental literacy and forming eco-activity among young readers. We consider the methods such as role-playing games, storytelling, and project activities based on reading to be highly promising.

6. Conclusions

Contemporary Ukrainian children’s literature on environmental topics employs various content and genre-based approaches to depicting eco-situations and eco-crises, as well as models of eco-rebel behavior and eco-initiatives. This research emphasizes the eco-pedagogical value of children’s literature by examining the novels Ghosts of Black Oak Wood and Taming of Kychera, which efficiently depict young protagonists who take on active roles as environmental changemakers They embody the ideals of an eco-centric worldview, an active position in solving eco-problems, opposition to the established social order and rebellion against environmental crimes, a responsible attitude towards nature, and contribute to the formation of ecological values in readers through emotional influence.

The key components of ecological representation in these texts are problematic eco-situations, behavioral models of young eco-heroes, eco-initiatives, and eco-perspectives, which together contribute to shaping readers’ environmental awareness and ethical stance. In line with the global trend of studying children’s literature within the framework of eco-criticism and the postcolonial turn, this research amplifies the Ukrainian voice, often marginalized in international discourse.

This research demonstrates the efficiency of ecocritical dialogues as a pedagogical method that fosters not only readers’ in-depth literary analysis but also their personal reflection and ecological engagement. The dialogues were offered to students aged 14–15, using Ghosts of Black Oak Wood by Bachynskyi and Taming of Kychera by Polyanko as core texts. The issues were related to interaction between a person and the environment, perception of nature, understanding of environmental problems and human activity that can prevent or solve them, eco-rebellion as manifestations of environmental awareness, and positioning oneself in the environment.

Particular attention was paid to environmental disasters portrayed in the texts, the characters’ responses, and parallels with real-world ecological challenges. The participants shared possible eco-initiatives and emphasized the need for active engagement and environmental responsibility.

The interactive discussions and ecocritical dialogues enabled teenagers to analyze environmental literature through reflection, creative thinking, and personal engagement. The process, supported by surveys and collaborative tools like Padlet, encouraged the participants to connect the actions of eco-heroes to their own eco-conscious perspectives and behaviors.

This approach encourages participants to think about their own views on nature and ways of preserving it. It also helps them to understand the connection between literature and the real environmental challenges of today. In addition, ecocritical dialogues contribute to fostering empathy and responsibility for the environment, which is an important step towards changes in behavior and attitudes towards the surrounding world.

Thus, the research confirms that children’s literature, when thoughtfully integrated into dialogic and interactive educational practices, becomes a powerful means for forming environmental literacy and civic responsibility among young readers.

It would be of particular significance to focus on integrating literary works with other forms of eco-pedagogy in future research, as well as examining their impact on the long-term environmental beliefs and behaviors of young recipients.

Author Contributions

Idea, Conceptualization, and methodology, T.K. and T.B.; Original draft preparation, T.K. and T.B.; Analyses, T.K.; Defining eco-pedagogical potential of the texts, T.B.; Experiment preparation and conducting surveys, T.K.; Analyses, description, and visualization of the experiment results, T.K.; References and technical edition, T.K.; Translation and review, T.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Pedagogy of Vasyl Stefanyk Precarpathian National University (protocol code 1, 27 August 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article and are openly available: Ecodialogues 1. Ghosts of Black Oak Wood by A. Bachynskyi. 2024. Padlet. Available online: https://padlet.com/tetianakachak1/padlet-jemwiq771hcy5d0n (accessed on 25 January 2025). Ecodialogues 2. Taming of Kychera by V. Polyanko. (2024). Padlet. Available online: https://padlet.com/tetianakachak1/padlet-iaksxh27i8jr9u6e (accessed on 25 January 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Ecodialogues 1. Ghosts of Black Oak Wood by A. Bachynskyi

1. Human Interaction with the Environment

- How do the protagonists perceive the Black Oak Wood and its inhabitants? What does their interaction with nature reveal about their character and values?

- Which actions of the protagonists, in your opinion, demonstrate a responsible or irresponsible attitude towards nature? How would you act in a similar situation?

- What does the Black Oak Wood symbolize for you in this novel? Can it be considered an integral part of the protagonists’ lives?

2. Perception of Nature

- What emotions did the depiction of nature in the book evoke in you? Has your attitude towards nature changed after reading it?

- In your opinion, how does the author convey the significance of nature? What influences our perception of the environment—the description, the characters’ emotions, or their actions?

- Do you agree that nature in the novel serves as a character rather than merely a backdrop for events? How does this influence your perception of the forest?

3. Understanding Environmental Issues and the Impact of Human Activity

- What environmental issues are depicted in the novel? How do the characters respond to them, and what does this reveal about their attitude towards the environment?

- Are there any references in the novel to nature conservation or environmental protection? How do these moments reflect real-world ecological problems we face today?

- How can we prevent or address similar issues in our own lives? In your opinion, what measures should be prioritized?

4. Eco-Rebellion as an Expression of Environmental Awareness

- Can any of the characters be considered an “eco-rebel”? What actions and motivations distinguish eco-rebellion from ordinary attitudes toward nature?

- How do you evaluate acts of environmental resistance or activism both in real life and in the novel? Should people be willing to challenge established norms to protect nature?

- What factors can motivate individuals to take responsibility for the environment and adopt an active stance? Do you observe similar behaviors in your own community?

5. Positioning Oneself in the Environment

- What role would you take in the situation described in the novel? How would you position yourself in relation to nature and its protection?

- Has the novel helped you better understand your role in the environment? How would you describe your contribution to nature conservation?

- How can you demonstrate eco-activism in your daily life? Has the novel inspired you to take specific actions or initiatives?

- Think of ideas for a project aimed at addressing or preventing environmental crises similar to those described in the novel at the local level. Consider the regional specifics and contemporary environmental challenges.

Ecodialogues 2. Taming of Kychera by V. Polyanko

1. Human Interaction with the Environment

- How is the interaction between humans and nature depicted in the story? How do the characters’ actions impact the environment, and how are the characters themselves transformed in response to nature?

- In your opinion, why does the forest hold such significance for the protagonists? How does their attitude toward the forest reflect the general state of ecological awareness?

2. Perception of Nature

- Through what colors and descriptions does the author portray the natural environment of Kychera? How does this influence your perception of the environment and the value of natural resources?

- In your view, how should society perceive natural treasures like Kychera? Can this perception influence our actions in everyday life?

3. Understanding Environmental Issues and the Impact of Human Activity

- What environmental problems are highlighted in the novel? Do you agree that the main causes of these issues stem from human activity? In what ways?

- Are there any suggestions in the novel for preserving nature? If you were in the characters’ place, how would you act to prevent environmental damage?

4. Eco-Rebellion as a Manifestation of Environmental Awareness and Responsibility

- Do any of the characters exhibit an eco-rebellious stance? Through which actions or words is this demonstrated?

- Do you believe that contemporary society needs eco-rebels? How can such individuals contribute to solving environmental problems? Are you ready to take an active position?

5. Positioning Oneself in the Environment

- What is your position regarding nature after reading this story? Has your perspective changed, and if so, why?

- How can your personal actions contribute to environmental protection? Do you plan to implement any changes in your daily life?

- What eco-initiatives could be beneficial in your school or community? Do you see yourself as part of these changes?

- Think of ideas for a project aimed at addressing or preventing ecological crises similar to those described in the novel, at the local level. Be sure to take into account the specific characteristics of your region and the challenges of the present time.

References

- Appleyard, Joseph Albert. 1991. Becoming a Reader. The Experience of Fiction from Childhood to Adulthood. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Aslam, Mamoona, and Maryam Ashfaq. 2023. Raising Eco-Consciousness in Children through Picture Books: A Comparative Analysis of English and Pakistani Children’s Fiction. Kashmir Journal of Language Research 26: 91–105. [Google Scholar]

- Bachynskyi, Andriy. 2022. Prymary Chornoi Dibrovy. [Ghosts of Black Oak Wood]. Lviv: Vydavnytstvo Staroho Leva. [Google Scholar]

- Barry, Peter. 1995. Ecocriticism. In Beginning Theory. An Introduction to Literary and Cultural Theory, 3rd ed. Manchester and New York: Manchester University Press, pp. 239–61. [Google Scholar]

- Bradford, Clare. 2003. The Sky is Falling: Children as Environmental Subjects in Contemporary Picture Books. In Children’s Literature and the Fin de Siecle. Edited by Roderick McGillis. Westport: Praeger, pp. 111–20. [Google Scholar]

- 2022. Cases of Potential Environmental Damage Caused by Russian Aggression. Interactive Map. Ecoaction. Available online: https://ecoaction.org.ua/warmap.html (accessed on 25 January 2025).

- Cocinos, Christopher. 1994. What is Ecocriticism? In Definition Ecocritical Theory and Practice. Sixteen Position Papers from the 1994 Western Literature Association Meeting, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 6 October 1994. Available online: https://www.asle.org/wp-content/uploads/ASLE_Primer_DefiningEcocrit.pdf (accessed on 25 January 2025).

- Dobrin, Sidney I., and Kenneth B. Kidd, eds. 2004. Wild Things: Children’s Culture and Ecocriticism. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Doughty, Terri, Justyna Deszcz-Tryhubczak, and Janet Grafton, eds. 2025. Children’s Literatures, Cultures, and Pedagogies in the Anthropocene: Multidisciplinary Entanglements. London: Bloomsbury Academic. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ecodialogues 1. Ghosts of Black Oak Wood by A. Bachynskyi. 2024. Padlet. Available online: https://padlet.com/tetianakachak1/padlet-jemwiq771hcy5d0n (accessed on 25 January 2025).

- Ecodialogues 2. Taming of Kychera by V. Polyanko. 2024. Padlet. Available online: https://padlet.com/tetianakachak1/padlet-iaksxh27i8jr9u6e (accessed on 25 January 2025).

- 2017. Education for Sustainable Development Goals: Learning Objectives; France: UNESCO. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000247444 (accessed on 25 January 2025). [CrossRef]

- Gaard, Greta. 2009. Children’s Environmental Literature: From Ecocriticism to Ecopedagogy. Neohelicon 36: 321–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gladwin, Derek. 2017. Ecocriticism. Oxford Bibliographies. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1093/OBO/9780190221911-0014 (accessed on 25 January 2025).

- Glotfelty, Cheryll. 1996. Introduction: Literary Studies in an Age of Environmental Crisis. In The Ecocriticism Reader: Landmarks in Literary Ecology. Athens and London: University of Georgia Press, pp. XV–XXXVII. Available online: https://www.amazon.de/Ecocriticism-ReaderLandmarks-Literary-Ecology/dp/0820317810 (accessed on 25 January 2025).

- Goga, Nina. 2018. Children’s Literature as an Exercise in Ecological Thinking. In Ecocritical Perspectives on Children’s Texts and Cultures. Critical Approaches to Children’s Literature. Edited by Nina Goga, Lykke Guanio-Uluru, Bjørg Oddrun Hallås and Aslaug Nyrnes. Basingstoke and Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goga, Nina, Lykke Guanio-Uluru, Bjørg Oddrun Hallås, and Aslaug Nyrnes, eds. 2018. Ecocritical Perspectives on Children’s Texts and Cultures: Nordic Dialogues. Critical Approaches to Children’s Literature Series; Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. 299p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goga, Nina, Lykke Guanio-Uluru, Bjørg Oddrun Hallås, Sissel M. Høisæter, Aslaug Nyrnes, and Hege Emma Rimmereide. 2023. Ecocritical dialogues in teacher education. Environmental Education Research 29: 1430–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hintz, Carrie, and Elaine Ostry, eds. 2003. Utopian and Dystopian Writing for Children and Young Adults. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kachak, Tetiana. 2018. Trends in the Development of Ukrainian Prose for Children and Youth at the Beginning of the 21st Century. Kyiv: Akademvydav. [Google Scholar]

- Kachak, Tetiana, and Tetyana Blyznyuk. 2024. War in Contemporary Ukrainian Literature for Children and Youth. Research Bulletin. Series: Philological Sciences 209: 151–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kachak, Tetiana, and Tetyana Blyznyuk. 2025. Contemporary Ukrainian Children’s Poetry and Prose. In Fieldwork in Ukrainian Children’s Literature. Edited by Mateusz Świetlicki and Anastasia Ulanowicz. New York and London: Routledge, pp. 169–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kachak, Tetiana, Tetyana Blyznyuk, Larysa Krul, Halyna Voloshchuk, and Nataliia Lytvyn. 2022. Children’s literature research: Receptive-aesthetic aspect. Apuntes Universitarios 12: 76–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumanska, Ju O. 2021. Ecological Aspects of Modern Literature for Children (on the Material of Prose by Z. Menzatiuk, O. Ilchenko, I. Andrusiak). Ph.D. thesis, Ternopil Volodymyr Hnatiuk National Pedagogical University, Ternopil, Ukraine. Available online: https://tnpu.edu.ua/naukova-robota/docaments-download/k58-053-02/Dis_Kumanska.pdf (accessed on 25 January 2025).

- Marchenko, Nataliia. 2023. Viktor Polyanko. Taming of the Kychera. Key. Available online: https://chl.kiev.ua/KEY/Books/ShowBook/811 (accessed on 25 January 2025).

- Massey, Geraldine, and Clare Bradford. 2011. Children as Ecocitizens: Ecocriticism and Environmental Texts. In Contemporary Children’s Literature and Film: Engaging with Theory. Edited by Kerry Mallan and Clare Bradford. London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 109–26. [Google Scholar]

- Meek, Margaret. 2004. Introduction Definitions, themes, changes, attitudes. In International Companion Encyclopedia of Children’s Literature, 2nd ed. Edited by Peter Hunt. London and New York: Routledge, vol. I, pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Monhardt, Rebecca, and Leigh Monhardt. 2000. Children’s Literature and Environmental Issues: Heart Over Mind? Reading Horizons 40: 175–84. Available online: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1218&context=reading_horizons (accessed on 25 January 2025).

- Moriarty, Sinéad. 2021. Modeling Environmental Heroes in Literature for Children: Stories of Youth Climate activist Greta Thunberg. The Lion and the Unicorn 45: 192–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolajeva, Maria. 2004. Narrative theory and children literature. In International Companion Encyclopedia of Children’s Literature, 2nd ed. Edited by Peter Hunt. London and New York: Routledge, vol. 1, pp. 166–78. [Google Scholar]

- Nodelman, Perry. 2000. Pleasure and Genre: Speculations on the Characteristics of Children’s Fiction. Children’s Literature 28: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orr, David W. 1992. Ecological Literacy: Education and the Transition to a Postmodern World. Albany: SUNY Press. [Google Scholar]

- Petsa, M. 2022. Literatura dlia ditei teper sylno zminytsia—Peremozhets Dytiachoi knyhy roku VVS Andrii Bachynskyi [Children’s literature will now change significantly—BBC Children’s Book of the Year winner Andrii Bachynskyi]. BBC News. Ukraine. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/ukrainian/news-64047860 (accessed on 25 January 2025).

- Polyanko, Viktor. 2022. Pryborkannia Kychery [Taming of Kychera]. Kyiv: Lira-K. [Google Scholar]

- Skjønsberg, Kari. 1985. The adult in the role of a child: The uses of the 1st person as a story-teller in books for children and young people. In The Portrayal of the Child in Children’s Literature: Bordeaux, Univ. of Gascony (Bordeaux III): 15–18 September, 1983. Edited by Denise Escarpit. Berlin and New York: K. G. Saur, pp. 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Świetlicki, Mateusz, and Anastasia Ulanowicz. 2025. Introduction to Ukrainian Children’s Literature. In Fieldwork in Ukrainian Children’s Literature. Edited by Mateusz Świetlicki and Anastasia Ulanowicz. New York and London: Routledge, pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Impact of the Russian War in Ukraine on the Climate. 2024. Ecoaction. Available online: https://ecoaction.org.ua/vplyv-ros-vijny-na-klimat2024.html (accessed on 25 January 2025).

- van der Beek, Suzanne, and Charlotte Lehmann. 2022. What Can You Do as an Eco-hero? A Study on the Ecopedagogical Potential of Dutch Non-fictional Environmental Texts for Children. Children’s Literature Education 55: 141–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vardanian, Maryna. 2022. Reading Chornobyl Catastrophe Within Ecofiction. Children’s Literature in Education 1: 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).