Abstract

This paper is an introduction to the Humanities Special Issue on ‘The Phenomenology of Travel and Tourism’. It is made up of four sections, the first two of which provide the main focus of discussion. We start by considering the idea of travel ‘in comfort’, which, as we show, has been historically bound up with cultures of the mobile virtual gaze. Comfort, by this reckoning, reflects a phenomenological disposition whereby the act of gazing at an object of spectacle is understood not in purely visual terms but as a spatial and somatic prefiguring of that object as an object of spectacle. A phenomenology of comfort, we argue, steers consideration towards the way forms of travel or tourism practice reflect embodied or disembodied modes of engagement with the world. This line of enquiry brings with it the need for more fine-grained analyses of questions of experience, which is picked up and developed in the second section. Here, we examine some of the important and foundational work that has helped push forward scholarship oriented towards the development of a phenomenological anthropology of travel and tourism experiences. Accordingly, a key aim of this paper, and of the Special Issue it provides the introduction to, is to push further and more resolutely towards these ends. The third section is an overview of the nine Special Issue contributions. The paper ends with Kay Ryan’s short poem, ‘The Niagara River’, a quietly foreboding meditation on the hazards of travelling in too much comfort and of reducing the world to little more than ‘changing scenes along the shore’, all the while remaining blind to what awaits downstream.

1. Travelling in Comfort

| Lisa Berndle: | When my father was alive we travelled a lot. We went nearly everywhere. We had a wonderful time. |

| Stefan Brand: | I didn’t know you travelled so much. |

| Lisa: | Oh, yes. |

| Stefan: | Perhaps we’ve been to some of the same places? |

| Lisa: | No, I don’t think so. |

| Stefan: | Where did you go? |

| Lisa: | Well, it was a long time ago. But, um… for instance there was Rio de Janeiro. Beautiful, exotic Rio with its botanical gardens, its avenue of palms, Sugarloaf Mountain, and… a harbour where you could look down and see the flying fish. [LOOKS OUT OF THE WINDOW] We’re in Venice! |

| Stefan: | Yes, we’ve arrived. Now, where would you like to go next? France, England, Russia? |

| Lisa: | Switzerland! |

| Stefan: | Switzerland! Excuse me one moment while I talk with the engineer… |

| (Scene from Letter from an Unknown Woman, Max Ophüls 1948) |

Figure 1.

Still from the film Letter from an Unknown Woman (Max Ophüls 1948).

For Lisa, the illusion of travel facilitates temporal journeys to her childhood: reminiscences of time spent with her father travelling to exotic destinations. What we in fact learn from these reflections is that Lisa’s childhood travels—to destinations such as Rio de Janeiro—were themselves no less virtual and imaginary. Her father would bring home pictures of foreign cultures and destinations from a friend he knew in the travel business. In the evening, he would put on his ‘travelling coat’ and ask ‘Where shall we go this evening?’. With the aid of the tourist images, they would consider the destinations to which they might next like to travel.

These reflections are presented within an overall narrative structure of the film that follows Lisa’s epistolary recollections of her doomed and unrequited love for Stefan. The pivotal role of the panorama scene thus not only mobilises the complex emotional geographies that come to define Lisa’s diegetic subjectivity, but it also alludes to the formal potentialities of ‘travel’ inscribed in the mobilised virtual gaze (), which itself represents an extension of more static modes of vicarious travel amongst nineteenth century leisure classes, in the form of Victorian travel photography (cf. ).

For the purposes of this introduction, the task of steering critical reflections on travel and tourism in an explicitly phenomenological direction is assisted in no small part by paying closer attention to what this scene from Letter from an Unknown Woman helps nudge into play.

If, as () has suggested, ‘[t]he gradual shift into postmodernity is marked… by the increased centrality of the mobilised and virtual gaze as a fundamental feature of everyday life’, then visual cultures of travel such as those depicted in fin de siècle Vienna become coextensive with those more latterly familiar to devotees of immersive cinema (e.g., IMAX or 4DX), virtual tourism (see Catherine Palmer’s paper in this Special Issue), or of augmented reality-enabled forms of locative media practice (; ; ). What these different technologies of the mobile virtual gaze share, a hundred-plus years apart, is not so much the spectacle of verisimilitude—the question of just how real or life-like the simulated experiences are—but of, on the one hand, the significance of the body in relation to the spectacle unfolding on the screen and, on the other, the production of a space of immersion and dwelling that is not limited to the representational space of the moving image projected on the screen. It is the importance of these two frames of reference, those of the body and of spaces of travel, that critically informs our introductory ruminations on the phenomenology of travel and tourism.

Of the many variations of panoramic and dioramic exhibition that were devised for public spectacle throughout the nineteenth century, the machine depicted in Letter from an Unknown Woman recalls a device invented in Germany in 1832 by Carl Wilhelm Gropius (1793–1870) called the Pleorama. This moving panorama was staged in an auditorium designed to resemble the form of a small ship holding approximately 30 people. An illusion of movement was created by slowly drawing a scenic back-cloth across the stage, taking the audience on an hour’s voyage in the Gulf of Naples, or on a journey down the Rhine (). A related device, the Padorama, exhibited at the Baker Street Bazaar in London in 1834, consisted of a 10,000-square-foot dioramic strip wound on drums which showed landscape scenery from the recently opened Liverpool to Manchester railway, the world’s first passenger line ().

In the 1900 Paris exposition, a Russian exhibit allowed visitors to take a virtual journey on the Trans-Siberian Railroad. The ‘passengers’ boarded seventy-five-foot-long carriages, including dining room, smoking room, and bedrooms, and took a forty-five minute trip between Moscow and Peking. Painted canvasses—scenic panoramas of the Caucasus and Siberia—rolled past the windows on an endless belt (). Clearly on a much greater scale than the more intimate version depicted in Ophüls’ film, this form of panoramic practice, like that of the diorama—in which changing light effects on giant, transparent paintings create the illusion of reality—were, as Altick contends, the ‘bourgeois public’s substitute for the Grand Tour, that seventeenth- and eighteenth-century cultural rite de passage of upper class society’ ().

If Ophüls’ fictional characters had left Vienna of 1900 and visited the Paris Exposition that took place in the same year, as well as travelling the Trans-Siberian Railroad, they could also have embarked on the Lumière Brothers’ Maréorama. Similarly to Gropius’ Pleorama, but with the heightened realism of moving imagery, spectators sat on a platform shaped like a ship’s hull and, with simulated rocking of the ship in the ocean, viewed actuality footage of a sea voyage to Nice, the Riviera, Naples, and Venice ().

A few years later in 1903, a cinema proprietor, George C. Hale of Kansas City, Missouri, introduced a simulated railroad experience in which the auditorium was designed to resemble a railway carriage, complete with a vibrating floor and sounds of a steam engine to make the trip more convincing. Exhibited widely in America and in London, these ‘Hale’s Tours’, as they were known, took the viewer/passenger on short train journeys through the Rocky Mountains, Wales, or Scotland, using film footage shot from a camera mounted on the front of a railway engine (). As the popularity of Hale’s Tours spread it created a demand for ever more diverse touristic scenery. Traveller-cameramen were dispatched throughout the globe to gather footage from destinations as far afield as Tokyo, Hanoi, Ceylon, Argentina and Borneo ().

The role of the train in the perceptual and experiential practices of the panorama and of early film viewing cannot be overstated (cf. , see also Michael Chanan’s paper in this Special Issue). For (), the impact of the railways effected a dramatic change in the way the spatial and temporal specificities of place and landscape were subsequently experienced by travellers. The hitherto more direct relationship between the traveller and the space travelled succumbed, with the advancement of the railways, to modernist celebrations of speed, the standardisation of time, and the projectile passage of the travelling-subject through space. A phrase commonly uttered in relation to the railways during the nineteenth century—‘the annihilation of time and space’—underscored the sense of social unease and general ambivalence generated by this new technological phenomenon ().

The ‘perceptual paradigm’ () instilled by this new mode of travel—described by Schivelbusch as ‘panoramic perception’—was shared by audiences of the panorama and diorama, and would later come to characterise the experience of the spectator in the cinema. The compression of time and space inaugurated by the railways also anticipated the radical discontinuities of space-time and the juxtaposition of disparate ‘mobile gazes’ that were to find their cinematic counterpart in editing techniques such as montage. ‘All distances in time and space are shrinking’, Heidegger noted; ‘Distant sites of the most ancient cultures are shown on film as if they stood this very moment amidst today’s street traffic’ (). At the turn of the twentieth century, communication in both its classical sense—referring to material transportation infrastructures and the actual movement of people and commodities at ever great speeds ()—quickly became co-extensive with new forms of electronic communication media such as film and radio. For Heidegger, writing in 1950, ‘[t]he peak of this abolition of remoteness [by time-space compression and communications technology] is reached by television, which will soon pervade and dominate the whole machinery of communication’ (). The virtualisation of travel—the collapse of spatio-temporal distance and the mobilisation of the gaze—reaches its apogee at a point where its apparent pervasiveness can only ever be historically contingent. For Heidegger, like Marshall McLuhan after him (), it was the daunting prospect of the television age. For us, it is from a vantage point where we look anxiously out towards a post-digital and posthuman landscape of travel where ‘hyperlinks make pathways disappear’, and ‘[e]lectronic mail does not need to conquer mountains and oceans’ ().

The deterritorialising effects of the railway were an historical by-product of the industrialisation of travel: a radical experiential shift in the collective consciousness of industrial nations. The more sedate travels of the Grand Tour, which, for Schivelbusch, constituted ‘an essential part of [bourgeois] education before the industrialisation of travel’ (), allowed, it has been suggested, ‘[an] assimilation of the spatial individuality of the places visited, by means of an effort that was both physical and intellectual’ (ibid, emphasis added). Altick’s contention that the panorama represented ‘the bourgeois public’s substitute for the Grand Tour’ thus raises the question as to what is lost—or gained—in this process of substitution from ‘actual’ to ‘virtual’ travel, or, more accurately, between travel practices which predated the perceptual paradigm associated with the panorama and the railways, and those which followed in its wake. A sense of prevailing cultural attitudes towards travel by train in the late 1800s, linking acceleration to intellectual decline and the disruption of the vita contemplativa (; ), can be found in Nietzsche’s observation that ‘[because of] the tremendous acceleration of life mind and eye have become accustomed to seeing and judging partially or inaccurately, and everyone is like the traveller who gets to know a land and its people from a railway carriage’ ().

Prato and Trivero describe trains, along with ships and airships, as ‘body containers’, associated with comfort, which entail ‘an implosive effect that “brackets out” the everyday world and recreates a smaller world with known and certain confines’ (). By contrast, ‘body expanders’, such as cars, aeroplanes, and motorcycles are argued to be based on the regulation of speed in an expansive everyday world, entailing ‘the modification of the body according to the laws of movement’ (ibid). This distinction is useful when applied to the bourgeois appropriation and consumption of space in corresponding practices of the mobile virtual gaze. The speed of spatio-temporal dislocation is considered not in terms of its abstract and isolated properties, but in its phenomenological correspondence between subject and world via specific technologies of travel, whereas the comfort of travel becomes a crucial factor in the objectification of the gaze in travel narratives and panoramic geographies, a factor arguably no less applicable to the structured and rarefied circuits of the Grand Tour as to the passive consumption of the tourist gaze in practices of the ‘spectator-passenger’ (). ‘The journey in comfort…’ argue Prato and Trivero, ‘exemplifies the bourgeois utopia of being able to move without ever risking your identity and always remaining completely independent of the places you travel through and the people you meet’ ().

Comfort, then, becomes not just a measure of design—i.e., responding to expectations of a functional standard of travel experience predicated on the removal of any shred of discomfort—but a phenomenological disposition whereby the act of gazing at an object of spectacle is understood not in purely visual terms but as a spatial and somatic prefiguring of that object as an object of spectacle. The distinction may seem slight but it is an important one. Comfort here speaks not of travel experiences one might typically expect to enjoy on the Orient Express, a luxury cruise, or those designed to ‘cater to the comfort of the well-to-do… [who are ferried around by] a fleet of five hundred sedan chairs circulating about the city’, to cite an example from Walter Benjamin’s ‘On Some Motifs in Baudelaire’ (). It can do, but what it more specifically points to is the embodying of comfort as a precognitive adjustment and orientation towards whatever is being framed as a site of spectacle. ‘Comfort isolates…’, notes Benjamin, ‘it brings those enjoying it closer to mechanization’ (ibid, p. 174).

Echoing this point, Prato and Trivero argue that ‘[w]ith comfort, the impact between the physical body and reality is softened through the delegation of a series of gestures and movements to the automatic mechanisms of the means of transport’ (). In the panorama scene from Letter to an Unknown Woman, Stefan and Lisa’s ‘travels in comfort’ are those of a bourgeois couple passively consuming an unfolding, mobile virtual gaze. The panorama operator, on the other hand, occupying the marginal spaces of this class-encoded mise en scène, is symbolically deprived of both comfort and perspective. Pedalling furiously away (yet remaining fixed to the spot), it is his own labour power upon which this touristic flight from the reality of here-and-now depends. The engineering and sociocultural production of panoramic perception is embodied in starkly different ways between consumer and producer. Comfort for one comes at the cost of discomfort for the other. Similarly, comfort and discomfort isolate in different ways: for the panorama operator it is alienation from the very thing his labour makes possible; for the spectator-passengers it is the ‘flesh of the world’ as Merleau-Ponty might put it (): sensory and haptic communication with social environments that pulse with the warmth and immediacy of lived experience. For Lisa and Stefan, comfort reduces the world to a panoramic backdrop that is there to be contemplated, ignored, or enjoyed aesthetically (but from a distance). Comfort becomes a means by which to divest oneself of the ‘infinitesimal discomforts that are the proof of existence of a weight, a dimension, nature’ ().

Comfort, by this reckoning at least, carries the symbolic weight of a habitus of travel experience that seems to tip perilously close to replicating the reductive binary of tourist and traveller. We have some sense of this in Prato and Trivero’s distinction between bourgeois travels in comfort—and ‘the mass diffusion’ (ibid, p. 30, emphasis added) that followed—and ‘the opposite case, which goes from the explorer in unknown lands to the summer “pilgrims” and their sleeping bags… [and a typology of traveller who] departs with the desire to return changed [thus refusing] the comfort that would conserve her or him as before’ (ibid, p. 39). The oft-raised distinction between (good/elite) travelling and (bad/populist) tourism is well illustrated by the American cultural historian Paul Fussell, for whom the ‘traveller’ represents an idea of displacement pitched historically and aesthetically between the heroic explorers of the age of the Enlightenment, who ‘[moved] towards the risks of the formless and the unknown’, and the present-day tourist, who ‘moves toward the security of the pure cliché’ ().

For Fussell, the vulgar, inauthentic travel of the tourist lies in the etymological roots of travel as work—travail. Nostalgic for a pedagogic idea of travel linked to self-cultivation and the pursuit of knowledge, he bewails not only the feckless tourist seduced by the ‘arts of mass publicity’ (), but also the proliferating ‘pseudo-places’ of tourism, such as airports, cruise ships, and the motel (against which he nostalgically evokes the days when, respectively, airports purportedly had character, and were not uniform and ‘placeless’; ships were romantic and bound for adventure and discovery; and the Grand Hotel still epitomised an idea of travel which the banal and transitory experience of the motel had yet to debase).

In an era when structuralism, semiotics and post-structuralism still held disproportionate sway in fields of cultural analysis the appeal of neatly lining up the idea of travel ‘in comfort’ in binary opposition to the travails and hard slog of travel ‘proper’ may have seemed enticing. But an equation such as this is far too simplistic. What is lacking in theoretical and methodological frameworks that push against these and similar concerns in studies of travel is a more full-throated phenomenological mode of critique. Prato and Trivero’s analysis goes some way towards addressing this but it does not go anywhere near far enough. The phenomenology of comfort—or a phenomenology of comfort—demands more fine-grained attention to questions of intentionality: how, for example, the tourist experience comes into being as an experience, not just as a discursively structured experience (or a disembodied ‘tourist gaze’ where comfort is homologous to the act of clinging securely to a frame through which—and only through which—the world of the other is rendered meaningful but otherwise out of reach). A phenomenology of comfort also requires significant consideration of the way it is embodied through forms of travel or tourism practice: that is, how the sensory and affective entanglements of self and other, and of body-subject and world, are written into ethnographic and autoethnographic forms of travel narrative. This, of course, means placing the travelling body more centrally within the frame and, in so doing, being attuned to the cadences and rhythms of the anthropological spaces (; ; ) that the traveller inhabits or is situated within. Comfort (or discomfort) is only registered as such by a traveller for whom the affordances of any given travel experience provide the means whereby that traveller is able to feel comfortable (or not) in their own skin. Anthropologically, the qualities of whatever it is that makes that experience comfortable and pleasurable can only be made sense of by securing a clearer understanding of the bodily habitus of which such qualities are a constituent part. A phenomenological anthropology of travel that is oriented around the affects of comfort seeks to glean insights into the existential and intersubjective grounding of the travel experience within a broader field of social and spatial practice.

In Letter to an Unknown Woman we are presented with a poetic illustration of this in the way Lisa relates the panoramic travel spectacle she has been enjoying with Stefan to her childhood memories of time spent virtually travelling with her father. A warm and comforting domestic image is provided of Lisa nestling down with her father to embark on voyages of the imagination. In the donning of his ‘travelling coat’ there is an element of performativity in the father’s playful initiation of a ritual that is marked out as special and sacred: an intimate moment between father and daughter in which the seeds of Lisa’s future wanderlust and curiosity about the world are sown. ‘Where shall we go this evening?’ is as much an invocation of the would-be traveller’s restless imagination as it is a question pitched to the young Lisa, as if calling upon the otherwise static images of foreign destinations to come alive and enchant their rapt beholders. Viewed in this way, the travelling coat is seen to function as a necessary adornment to the ritual process, as if without it the photographs would be unable to work their magic in quite the same way. In this homely and familial sharing of imaginary worlds we are also afforded a glimpse of the wider social ties that link Lisa, through her father, to middle-class networks of business and commerce that help facilitate the gradual accrual of social and cultural capital. Although these relationships appear at one step removed from the phenomenological immediacy of the elicitation ritual being playfully enacted with her father (or Lisa’s remembering of the ritual as prompted by the travel experience she is sharing with Stefan many years later), they are no less an important part of the enculturation process whereby the imaginaries and possibilities of travel are brought firmly into being.

By placing our focus on comfort (or the lack thereof) we are purposely steering our introductory frames of reference towards forms of affective comportment that determine the specific feel, kinaesthetic movement, ambience or rhythm that may underwrite any given travel experience. The word that carries by far the most weight here, and which might otherwise not be fully accounted for if read just in terms of its vernacular or prosaic application, is experience. In their different ways, all of the contributions to this Special Issue are coming at questions of travel through the lens of experience and the experiential. What might be clumsily referred to as the ‘non-representational’ (; ) modalities of travel and tourism—or ‘more-than-representational’ which is arguably even worse—are those that, by definition, slip through the net of mere description and interpretation, if by this we mean approaches that pay closer heed to questions of embodiment, affect and the grounding of experience in everyday forms of sociocultural practice. For the writer or ethnographer, experience is in effect translated from something that is otherwise very different and which is ‘located’ in the experiential flux of life as it is being lived in all its messiness and corporeality: in other words, the traveller or tourist experiencing the being-ness of being a traveller or tourist at a specific moment in time and space. How else, it might be wondered, can this translated experience be communicated outside of language and the mechanics of representation? Obviously it cannot. But we raise this more as a methodological question than a rhetorical one. Insofar as experience or an experience becomes something of note, in the sense that that experience becomes an object of analysis, we may think of this as an ecstasy of experience whereby, etymologically, ecstasy or ex-stasis points to an existential moment of being that becomes an experience by virtue of the fact that it extends beyond or outside of oneself. The experience is not one that is flat or inconsequential (and as such is not likely to even be noticed as an experience at all) but is in some way remarkable to the extent that it affords a very particular perception of and engagement with the world (which then becomes an experience to take note of or critically turn over as an object of analysis). As established through the writings of Benjamin and others, the distinction made in the German language between experience as erlebnis and experience as erfahrung offers a useful means by which to go some way towards unpicking the knotted hermeneutics of experience and the experiential in terms of having an experience and of subsequently documenting or making accountable that experience.

We will say more on erlebnis and erfahrung shortly, but on this precise point, it is interesting to note that in discussions that fed into the production of this Special Issue, an interlocutor was very dismissive of the idea that an experience can be experienced: ‘There is no such thing as an “experience of experience”, the critic (a philosopher) maintained, ‘just as there is no such thing as “seeing of seeing”, “hearing of hearing” or “touching of touching”’. Without wishing to get drawn too far down a wholly tangential byway of philosophical reasoning here, what we would say in response to this is that it is a view that appears to discount (or overlook) the possibility that what counts as ‘experience’ also comes in commoditised and packaged form, i.e., a product to be sold to consumers (such as travellers and tourists) on the promise that it can be enjoyed as an experience. Moreover, that a tourist may enjoy an ‘experience’—whether a Northern Lights Experience, Serengeti Safari Experience, Aussie Outback Experience, or Harry Potter Experience (all invariably prefixed by the word ‘authentic’)—does not presuppose what that experience is in terms of how an individual tourist may experience that experience. To come anywhere near understanding or ‘getting inside’ the phenomenology of the travel experience it becomes necessary to confront or embody experience from an ethnographic or autoethnographic standpoint. It is, then, the phenomenological anthropology of travel and tourism to which we now turn.

2. Travel, Tourism and the Anthropology of Experience

We have already noted Heidegger’s comments about time-space compression in his article ‘The Thing’. The technological changes Heidegger draws attention to, and the mass availability of images and faster modes of transport, brings us directly to travel and tourism; as Heidegger attests: ‘Man [sic] now reaches overnight, by plane, places, which formerly took weeks and months of travel’ (). Heidegger lived most of his life in his home region of south-west Germany and did not travel extensively himself. He also discouraged others to travel (). Of his limited travels, the most notable excursions outside of Germany were his visits to Greece, the first in 1962 and two subsequent trips. The trip in 1962, was, according to Sallis, the most influential on his thinking. His experience and reflections became the basis for the book Sojourns written during his travels and first published in English in 2005. This slim volume is a consideration of the notion of ‘truth’ on which he pondered during his travels to Greece.

A fundamental question for Heidegger was whether the Greece of 1962 would give any insight into the Greece of antiquity (Figure 2). According to (), although Heidegger does not use the terms globalisation and would not be aware of neo-liberalisation, Sojourns can be understood as prefiguring the neoliberal globalisation debates that would ensue in later decades. At the same time, complex interconnections between travel, phenomenology and ethics that Urie argues are brought together in the volume speaks of a phenomenological praxis which is not only about physically travelling but is also present in thought processes. What is meant by this is that there is movement through thinking that by going backwards in thought to antiquity in Heidegger’s search for truth—‘what is of necessity is to look back and reflect on that which an ancient memory has preserved for us’ ()—and then moving forward in thought to the present as he moved around modern-day Greece—‘the Greek element remained an expectation, something that I was sensing in the poetry of the ancients… something I was thinking on the long paths of my own thought’ (). The idea of thought as following a pathway connects with ideas of wayfinding in terms of not just simply navigating our way to some physical or geographical point but also, and more crucially, making the way as we go (). That is, the internal movement in thinking between ideas and across time periods produces, in effect, a thought, an idea, or a philosophical position that unfolds as the thinking occurs.

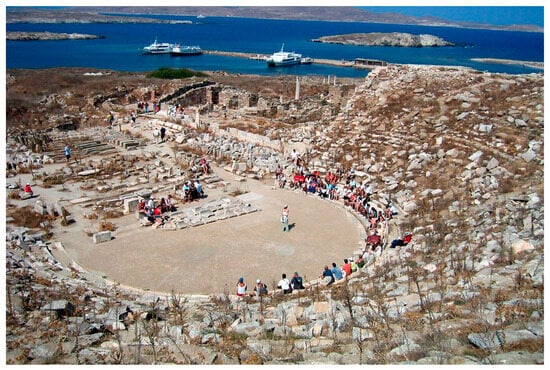

Figure 2.

Tourists at the Ancient Theatre on the Greek island of Delos. In 1954, prior to his subsequent travels to Greece, Martin Heidegger confided in a letter that ‘Delos has long been my dream’ (). ‘Only through the experience of Delos’, Heidegger went on to write in his travelogue Sojourns, ‘did the journey to Greece become a sojourn… [a] field of unconcealed hiddenness that accords sojourn’ (). The philosopher further remarks that the nearby island of Mykonos, ‘the fashionable spot of international tourism’, cloaks and protects—in other words, provided an expedient means of diversion from—the more ‘meaningful island of Delos’ (ibid, p. 36). Photograph by Wally Gobetz, www.flickr.com/photos/wallyg/143687139 (accessed 7 March 2025)—Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0).

The discussions of wayfinding, dwelling and truth in Sojourns are familiar themes in Heidegger’s writing. What the essay also does is give insights into Heidegger’s reflections on tourism. For Heidegger, both the presence of tourists and the tourism ‘product’ were a hindrance to his own endeavours to engage with ancient Greece. Further, the presentation of ancient Greece through the lens of tourism was, according to Heidegger, also a hindrance to the tourists’ own encounters with antiquity and notions of truth. In short, Heidegger is disparaging of tourism and tourists. He makes clear his annoyance with the crowds at the Acropolis as they are intent on recording their visit by taking photos and making films of what they see (). Of his visit to the theatre and Temple of Apollo at Delphi he opines, ‘during the hours we stayed at the holy place, the crowd of visitors increased significantly—everywhere people taking pictures. They throw their memories in the technically produced picture. They abandon without clue the feast of thinking that they ignore’ and ‘from the road, saturated with buses and cars, the sacred region looked like nothing more than a landscape that has become the possession of tourism’ (pp. 54–55). For Heidegger, tourism is an ‘unthoughtful assault’ that imposes an ‘alien power’ (p. 55) on ancient Greece. What Heidegger overlooks in his search for truth and in his criticism of tourists is that he too was a tourist; he too consumed the landscape before him by taking photographs (see examples on pages 14, 40, 47 of Sojourns) and using local resources; he too used the mechanics of tourism to facilitate his journey, for example, the ship Yugoslavia that transported him between the different places that are home to the sites he was keen to see, and the hotel in Venice he stayed in before joining the ship. For Heidegger, his travels around Greece were a search for something: in his case that something was Truth.

The notion that tourism is a search for something, or that the individual tourist is searching for something, has infused tourism literature since Dean MacCannell’s seminal work The Tourist. A New Theory of the Leisure Class (). For MacCannell, the alienation and fragmentation resulting from conditions of modernity could be countered in the seeking of a sense of wholeness and authenticity by the tourist and that this could be found in other people and places. His argument was formulated in part in response to () view that tourism is a pseudo-event, and, in addition, to counter anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss’s view that modernity had destroyed structure and that structuralist understandings of the world were, perforce, no longer possible (). Another influential approach to theoretical understanding of what tourists are looking for can be found in the work of sociologist John (). According to Urry, what underlays tourism activity is a desire to ‘gaze’ upon difference—whether landscapes, people, practices, traditions, and so on—and that, further, the way in which the gaze is directed (by tour guides for example) is a structuring device that speaks of the power relations between those who gaze and those being gazed upon.

Preceding Urry, and in criticism of MacCannell, () wrote ‘A Phenomenology of Tourist Experiences’. Published in the journal Sociology, Cohen sought to challenge both Boorstin’s assertion that tourism is a pseudo-event and MacCannell’s thesis that tourism is a search for authenticity by an alienated modern subject. Cohen, arguing that tourists should not be treated as a homogenous group in the way that MacCannell was seeming to suggest, proposed a five-part continuum of tourists’ experiences based on a typology of tourists for which questions of authenticity were linked to the type of tourist and her relationship to the home world from which she derived. Some tourists, he argued, were looking for and content to settle with an unserious recreational experience while others were more concerned with an outer, other-directed spiritual experience akin to religion, which Cohen described as a form of existential tourism ‘in which a tourist travels in search of a personal or spiritual centre located beyond their immediate place of residence’ (). Cohen later further expounded on his view that existential tourists were in search of a spiritual centre located outside of their home worlds in his use of the idea of tourism as play to try to understand the nature of liminality and ritual processes in contemporary western society (). Cohen concluded his 1979 paper by highlighting that at the time of writing his paper there had been few in-depth studies of tourist experiences and he called for more work in this area. We might note that Cohen’s own research had not engaged directly with tourists either. Indeed, Cohen himself highlights that, ‘the phenomenological analysis of tourist experiences in this paper has been highly speculative; contrary to other areas in the study of tourism, the in-depth study of tourist experience is not yet much developed’ ().

Despite this call, studies of what tourists were saying and doing, how they themselves practiced tourism, what they said about their experiences and what these experiences meant to them remained few and far between. A change occurred when sociologists () argued for a consideration of the centrality of the body and embodiment in the study of tourism experiences. In addition, they opined that the writing about tourists had too often been from a male-centric position in which ideas about breaks from the everyday and searches for sociocultural difference might be interpreted differently depending on gender. Their work emphasised the need to consider tourism as based as much in the somatic as in any cerebral pursuits. As they contended, ‘so far the tourist has lacked a body because the analyses have tended to concentrate on the gaze’ (, emphasis in original). Urry was later to acknowledge that an ‘emphasis on the visual reduces the body to surface and marginalises the sensuality of the body’ (). Cultural geographer David Crouch argued from the perspective of studying not only tourism but other types of leisure spaces that, ‘[t]he body tests its physical boundaries and fulfils its own desires in movement, orders and unsettles, relates and punctuates its space through motions, the way the body makes out space, places itself, incorporates its sensuality’ (). In later work, with fellow geographers Lars Aronsson and Lage Wahlström, Crouch contended that, ‘[b]eing a tourist is to practise. By practice we mean the actions, movements, ideas, dispositions, feelings, attitudes and subjectivities that the individual possesses’ (). In their focus on the practice of tourism and the bodies of tourists, Crouch, Aronsson and Wahlström were drawing attention to what Crouch described elsewhere as the ‘feeling of doing’ (). Anthropologist Edward Bruner also drew attention to the importance of practice in his 2005 monograph Culture on Tour in which he emphasised the significance of how meanings are generated in practice () and argues that there is a need to develop ‘understanding of…people’s own sense of travel, mobility, locality, and place’ (ibid, p. 252).

According to () the use of phenomenological approaches has grown in the study of tourism. They identify, however, a problem insofar as these studies have not, they suggest, considered the specific epistemological and philosophical underpinnings of different approaches. In particular, they highlight the differences between Edmund Husserl’s phenomenology and that of Heidegger, claiming that failure to situate research as clearly identifiable as one phenomenological approach rather than the other undermines its very usage. Pernecky and Jamal note that the hermeneutical phenomenology of Heidegger, which relates to ideas of being and experience, was not much used in the tourism literature at the time of their writing. They stress the value of adopting a Heideggerian approach, arguing that ‘hermeneutic phenomenology situates the human body in a network of relationships and practices, thus facilitating an embodied view of experiences, rather than the disembodied, Cartesian dualities that the Husserlian phenomenology which preceded it tended towards’ (). The authors conclude that the value of Heidegger’s phenomenology is that it ‘provides for situated and embodied accounts of tourism, and offers the opportunity to delve into the understanding of a tourist’s experience’ (ibid, pp. 1071–72).

More recently, others have taken a phenomenological approach to their study of travel and tourism. For example, Hazel Andrews has drawn on an existential anthropological approach to understand the performative and embodied world of tourists and the imagination as forms of embodied practice (, ). Catherine () monograph Being and Dwelling Through Tourism: An Anthropological Perspective takes a phenomenological approach to explore how tourism practices allow us to know and feel that we are human. Les Roberts’s work on deep mapping and spatial anthropology (, ) similarly approaches the study of everyday socio-spatial practices from a phenomenological standpoint that is premised on the divesting of an idea of space that is held above, apart, or at arm’s length from the warmth and fleshiness of space as it is lived. Others too have focussed on questions of experience, ideas of embodiment and the role of the body in touristic practice (see, for example, work by ; , ). In addition, Palmer’s and Andrews’s 2020 edited collection focuses on tourism and embodiment in a broad sense. It provides ‘an approach [which] is holistic, acknowledging the inseparable and interrelated relationship between the body, the senses and the lifeworld’ ().

The focus on the practice of tourism and the role of the body/embodiment begins to respond (although not necessarily directly) to () call for more research with tourists and brings a more phenomenological and experiential dimension to understanding people and how they live their lives. It moves away from the subject constructed in an overarching set of categories towards an understanding of the embodied body-subject. Further, by highlighting tourism as practice, we can begin to consider ideas relating to experience.

The commodification of experience is widely evident in tourism marketing materials (e.g., Experience Days offered by companies such as Virgin (www.virginexperiencedays.co.uk/ (accessed 7 March 2025)). The idea of having an experience, or packaging something as an experience, became so pervasive in sociocultural life that Pine and Gilmore discussed the ‘experience economy’ () as the next stage in economic development following on from ‘service economy’. This represented a shift away from economies based mainly on providing services—banking, catering, hospitality, and so on—to an economy in which events were developed, packaged and marketed to consumers that offered the promise of ‘a good time’ or ‘happy memories’, which, in turn, suggests that intangible qualities related to fun and memory become part of the product being promoted. We have already noted that tourism products are infused by the notion of buying an experience, as if experience is external to ourselves and in and of itself an object. In order to better understand the importance and pervasiveness of experience in travel and tourism it is necessary therefore to engage with anthropological approaches to experience; that is, to anchor experience and the experiential in embodied travel and tourism practices: to return back to tourists and travellers themselves, to rework Hussurl’s famous phenomenological dictum ‘back to things themselves’ (; ).

An anthropology of experience and a phenomenological approach to understanding the world was developed in the work of () in their edited collection The Anthropology of Experience. Influenced by German philosopher Wilhelm Dilthey, Bruner argues, ‘the anthropology of experience deals with how individuals actually experience their culture, that is how events are received by consciousness. By experience we mean not just sense data, cognition … but also feelings and expectations’ (). The work in Bruner’s and Turner’s volume focuses on understanding experience from a dramaturlurgical perspective of performance and narrative. It acknowledges the complexity of trying to define what experience means and acknowledges that experiences are mainly formed on individual terms in which ‘present experience always takes account of the past and anticipates the future’ (ibid, p. 8). Nevertheless, according to Clifford Geertz in his epilogue to the volume, experience remains an ‘elusive master concept’ (). Although we can only have our own experiences and what is meant by experience is not necessarily easy to define or represent, as Thomas J. Csordas contends, ‘it will not do to identify what we are getting at with a negative term, as something non-representational’ ().

In English there is one word, ‘experience’, whereas in German there are two: Erfahrung and Erlebnis. These, respectively, refer to that which stands out and that which is passively endured. Anthropologist Michael () draws on the distinction by relating Erfahrung to that which we encounter and Erlebnis to the senses, emotions, intuition and movement. Erlebnis is about process, it is not fixed. Rather there are several potentialities as we encounter and experience the world which, for Jackson, are interwoven with ‘being’ that ‘is (…) in continual flux, waxing and waning according to a person’s situation’ (). It is the world of the subjective; a world in which there are events, things that happen—in a word, experiences. It is important to recognise how people are experiencing such experiences: what is felt, thought, remembered; the way their beingness has bearing on what is being experienced. As Jackson says, ‘no event can be disentangled from one’s experience of it, from one’s retrospective descriptions and redescriptions’ (). This takes us again to the body and embodiment. Before continuing with the idea of experience per se, it is worth briefly outlining the theoretical lineage that has shaped some ideas about the body and embodiment in anthropology.

Merleau-Ponty’s Phenomenology of Perception has been influential in bringing to the fore the importance of thinking with bodies in relation to understanding how we experience. According to Merleau-Ponty, ‘[t]he world is not what I think, but what I live. I am open to the world’ (). Our bodies, then, are integral to our perceptual experience. For Merleau-Ponty, our bodies are always present to ourselves but cannot be simply objectively observed. Rather, our bodies are a meeting place of our pasts, presents and futures. That is, we have learned ways of doing things but because the body is present for us how it is in the present brings about our current experiences that in turn inform how we are in the future.

Thus, the world is not external to us but happens as it is perceived, as we make it. For Csordas, ‘the paradigm of embodiment has as a principal characteristic the collapse of dualities between mind and body, subject and object’ (). This approach moves away from semiotic and structuralist interpretations of the world to one that is more open to the contingencies of life as it is lived. To illustrate the point, in tourism, the embodied nature of the holiday experience has been explored by () based on her ethnography of British tourists holidaying in Spain. For example, although recognising that the acquisition of a suntan can have symbolic value for tourists, Andrews attests that the practice of sunbathing is an embodiment of some ideas relating to comfort associated with being on holiday, for example feelings of warmth, overall well-being and a sense of nourishment in a ‘recharging of the batteries’ that would see the tourist through the winter months. Andrews encountered one young tourist who described sunbathing as ‘totally veggin’ out; that is, being completely relaxed. The prone nature of lying on the sunbed was an embodiment of the idea of the holiday as relaxation. A further sense of well-being in the body-subject, Andrews argues, occurs with what she describes as ‘the unfettered, “unbuckled”’ bodies found in the holiday setting (). Public exposure of more flesh in the resorts compared to the home world, where a different climate and different demands on the person generally keep bodies more covered, along with public displays of parts of the body that would normally be considered taboo in the home, not only focuses attention on the importance of the largely neglected tourist body in studies of tourism but speaks also to the idea of the holiday as a time of freedom. As such, ideas of freedom are embodied by the minimal use of clothing that a hot, beach tourist experience facilitates and notions of freedom often associated with holidays in general ().

Through an experiential understanding of how we are in the world we can see how viewing experience as something that is exclusively marketed and discussed in economic terms (), reduces it, in effect, to a single, graspable entity with limited use for appreciating how life is lived. The use of the term ‘imaginaries’ that has taken purchase in recent tourism literature has a similar reductionist effect. The importance of people’s abilities to imagine what their holiday experiences might be like has long infused the tourism literature (see, for example, work by ; ; ; ). The packaging of peoples and places to appeal to ideas of what it is like elsewhere (or what an experience might be like) is another tool of tourism marketing. The images and descriptive narratives in guidebooks and travel brochures have been called by some ‘tourism imaginaries’ (, ). It has been argued that these so-called imaginaries ‘produce our sense of reality’ (). These imaginaries are seen in a rather static way, as existing outside of the person and as a priori to the practice of being a tourist. We do not dismiss the importance of representation to tantalise, enchant and entice potential tourists to a destination. We do, however, caution against an approach that would appear to do what Urbain warns should not be done if we wish to avoid seeing tourists ‘as passive characters without consciousness, like soft dough ready to mould’ (). Urbain draws attention to the trap of thinking in terms of the dichotomy associated with structure and agency. A focus on the idea of imaginaries as structuring devices () has echoes of early tourism literature that saw tourism as organised around ideas of difference () and gives little credence to the ability of tourists to make their experiences. Conceived of in such terms, tourism imaginaries do not adequately take into account the ways imaginaries may be embodied and worked through in practice.

Echoing this point, Tim Ingold has explored the way changes in thinking associated with rationalisation connected to the Enlightenment saw the imagination set loose ‘from its earthly moorings’ () and which thus separated it from life as lived. For Ingold, the rationalisation process he refers to made the imagination external to us, as something to be treated with scepticism. The Enlightenment heralded a general change to the sensual logic of travel, one that moved away from the importance of listening to a world in which the eye was privileged above the other senses. As Judith Adler notes, ‘in a convention of western tourism which has become so taken for granted that it risks passing without remark, it is often said that people travel to ‘see’ the world, and assumed that travel knowledge is substantially gained through observation’ (). We contend that travel knowledge is substantially gained through bodily experiences.

Not thinking of touristic practice in terms of what is imagined moves us towards a focus on touristic practices as a way of being that, to borrow again from Ingold, ‘grows from the very soil of an existential involvement in the sensible world’ (, emphasis in the original) in which ‘to imagine … is not so much to conjure up images of a reality ‘out there’, whether virtual or actual, true or false, as to participate from within, through perception and action, in the very becoming of things’ (ibid).

In terms of tourism, therefore, if we wish to understand tourists and how they practice tourism it is essential to understand what being a tourist is; how someone is as a tourist in the moments of its doing. As Jackson and Piette contend, life should not be reduced to ‘culturally or socially constructed representations’ (). Instead, we should be concerned with ‘the variability, mutability, and indeterminacy of that lived reality as it makes its appearance in real time, in specific moments, in actual situations, and in the interstices between interpretations, constructions, and rationalisations, continually shifting from certainty to uncertainty, fixity to fluidity, closure to openness, passivity to activity, body to mind, integration to fragmentation, feeling to thought, belief to doubt’ (). Moreover, although we might note that our thoughts, feelings and actions are historically shaped, ‘every person’s existence is characterized by projects, intentions, desires, and outcomes that outstrip and, in some sense, transform these prior conditions’ (). For the tourist and traveller, she or he might arrive somewhere with prior motives for being there and with preconceived notions of what to expect gained from any number of sources, but it is in practice that the imagination operates, and it is in practice that s/he experiences the world.

This collection of papers seeks to situate tourists not as static consumers of external a priori ideas or ideals, but as people who, through not only their embodied imaginations but also their ways of being in the world, are in and of the world, making their travel experiences as part of life as lived: full of emotions, reflections and changes in direction in the doing of the experience. Understanding touristic practice is about appreciating that the experience is made in the moment, as if unrolling a carpet, it reveals itself as it unfurls.

3. Contributions to the Special Issue

The contributions that make up this Humanities Special Issue on The Phenomenology of Travel and Tourism are introduced here in order of publication.

The concept of ‘songlines’ is invoked in Les Roberts’s paper (Songlines Are for Singing: Un/Mapping the Lived Spaces of Travelling Memory) as a means of navigating spatial stories woven from the autobiogeographical braiding of music and memory. Borrowing from Astrid Erll’s concept of ‘travelling memory’, the idea of songlines provides a performative framework with which to both travel with music memory and to map or unmap the travelling of music memory. Discussion is accordingly centred around the following questions: How should the songlines of memory be mapped in ways that remain true and resonant with those whose spatial stories they tell? How, phenomenologically, can memory be rendered as an energy that remains creatively vital without running the risk of dissipating that energy by seeking to fix it in space and time (to memorialise it)? And if, as is advocated in the paper, we should not be in the business of mapping songlines, how do we go about the task of singing them? Pursuing these and other lines of enquiry, Roberts’s paper explores a spatial anthropology of movement and travel in which the un/mapping of popular music memory mobilises phenomenological understandings of the entanglements of self, culture and embodied memory.

Drawing on spatial theories of intentionality, Edward Huijbens’s paper (The Spaces and Places of the Tourism Encounter: On Re-Centring the Human in a More-Than/Non-Human World) approaches phenomenological understandings of tourism and touristic practices by seeking to recentre human intentionality as the core of the tourism encounter as a means to better address its political nature and relevance. Critiquing some of the key propositions of relational ontologies in which the body and human actions are relationally enmeshed in networks of more-than/non-human entities, the paper is not advocating the wholesale rejection of these arguments. Instead, it seeks to augment them through a focus on the intention to care. In so doing, the paper explore the ways in which the tourism encounter can be re-storied as one for making spaces and places of conviviality through people relating to each other and their surroundings with particular intent imbued with care. Huijbens’s argues that valuing care and how it can be narrated helps to make space for a plurality of futures which can in turn break the deadlock of tourism being conceived either as mass/over- or alternative tourism.

In Questioning Walking Tourism from a Phenomenological Perspective: Epistemological and Methodological Innovations, Chiara Rabbiosi and Sabrina Meneghello examine the overlooked entanglement of space, material practices, affects, and cognitive work emplaced in walking tourism. As a tourism activity that is generally practised in the open air away from crowded locations, walking tourism finds itself particularly well-adapted to the sensibilities and demands of travel in a post-pandemic era. While walking is often represented as a relatively easy activity in common consumer discourse, Rabbiosi and Meneghello argue that it is in fact much more complex, pointing to a need to rethink and revise the notion of tourist place performance by focusing on walking both as a tourist practice and as a research method that questions multi-sensory and emotional walker engagement. The authors do this by drawing from a walking tourism experience undertaken as part of a student trip in order to explore how emotions that arise from walkers’ embodied encounters with living, as well as inanimate elements, extend beyond what might be included in a simple focus on landscape ‘sights’. Accordingly, the paper provides a cogent demonstration of the efficacy of phenomenological approaches to walking tourism and the study of tourism mobilities more broadly.

Michael Chanan’s contribution to the Special Issue (Tourist Trap: Cuba as a Microcosm) stems from experiences and reflections on the making of a film about ecology in Cuba in 2019, Cuba: Living Between Hurricanes. Informed by the perspectives of autoethnography and phenomenology, the author explores the cognitive dissonance of the filmmaker’s ambiguous relationship, as a professional tourist, to the contradictions of the tourist industry as refracted through the small coastal town of Caibarién on the north coast where Hurricane Irma made landfall in 2017. Noting that ‘tourism studies’ is not a stand-alone discipline, straddling, as it does, fields such as geography, economics, sociology, anthropology, cultural studies, and more, the author asks ‘Is there room under this umbrella for the phenomenological experience of the individual subject, the reflexivity of personal experience, of one’s own encounter with travel as part of the ecosystem of modern life?’ Writing from the standpoint of both tourist/traveller and as a filmmaker with a longstanding interest in the culture, history and politics of Cuba, Chanan shows how critical attentiveness to the autoethnographic and experiential underpinnings of travel and tourism practices can offer compelling insights into wider questions of political economy, globalisation and climate change.

In her article Co-Creating Nature: Tourist Photography as a Creative Performance, Katrin Lund examines tourism nature photography as a creative and sensual activity. Based on a collection of photographs gathered from tourists in the Strandir region in northwest Iceland, Lund demonstrates how photographing nature is a more-than-human practice in which nature has full agency. Building on critiques of perspectives that have prioritised the gaze of the tourist and, correspondingly, underplayed the importance of performance and embodiment in analyses of tourism, the paper explores the way photography can be considered a practice that is relational and sensual and one that cannot be reduced to the seeing eye. Lund addresses the complex, more-than-human relations that emerge in photographs collected in Strandir, arguing that the act of photographing, as a performative practice, is improvisational and co-creative, and the material surroundings have a direct and active agency. Communicating through lyrical expressiveness rather than the realist paradigm, tourist photography becomes a poetic practice of making, weaving together the sensing self and the vital surroundings in the moving moment that the photograph captures.

Catherine Palmer’s contribution provides an anthropologically derived philosophy of the nature of experience in relation to the lifeworld of virtual tourism. Framed around Martin Heidegger and Tim Ingold’s concept of dwelling, Virtual Dwelling and the Phenomenology of Experience: Museum Encounters between Self and World interrogates what the implications of a virtually derived experience of tourism might be for how we understand what experience means and by extension the experience of being human-in-the-world—in effect, what it means to ‘experience’ virtual tourism. Palmer illustrates her argument by focusing on extended reality (XR) technology within the context of three museums: Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle and the Louvre, both of which are in France, and the Kennedy Space Centre Visitor Complex in the United States. These examples provide a snapshot into the merging, blending or overlaying of the physical with the virtual. Drawing from Heidegger, Palmer argues that the significance of technology does not lie in its instrumentality as a resource or as a means to an end. Its significance comes from its capacity to un-conceal or reveal a ‘real’ world of relations and intentions through which humans take power over reality. Viewed thus, technologically modified experiences of a virtual-tourism-world reveal experience as virtual dwelling, and as experience of the embeddedness of being human in the world.

Hazel Andrew’s paper is an exploration of play in tourism. Mordaith in Mallorca: Playing with Toy Tourism is situated in an approach to play and toys informed by phenomenological perspectives and theoretical insights drawn from existential anthropology. It argues that tourism and play are intimately linked and outlines the ways in which connections between the two have been made. Using the notion of ‘toy tourism’, Andrews examines the ways in which touristic practices associated with play are brought into being in the moment of doing. The research is located in the resorts of Palmanova and Magaluf on the Mediterranean island of Mallorca. Using a doll from the Barbie Fashionista range, named Mordaith by the author, Andrews describes how and why Mordaith became her travel companion and the experience and events associated with time spent with her in the resorts. The paper follows an experimental approach that unfolds in the writing as much as in the gathering of information during fieldwork. Andrews argues that what play is and what a toy is, are neither fixed nor graspable objectivities. Rather, both toy and play, and, thus, toy tourism, emerge in the embodied imaginative understanding of what touristic and toy tourism practices are, as well as the actual embodied and emotional movements of employing a toy in practice.

In Jonathan Purkis and Patrick Laviolette’s contribution to the Special Issue, the authors follow a purposely non-linear trajectory to explore the haptic and corporeal dimensions of hitchhiking and the phenomenological facets involved in thumbing rides from strangers. Hitchhiking and the Production of Haptic Knowledge is grounded in a form of duo-auto-ethnography, drawing on the experiences of two seasoned hitchhikers well-versed in the practice. Noting how the cultural and artistic practices that continue to surround hitchhiking subcultures have remained largely untapped as a focus of serious scholastic research, Purkis and Laviolette use this mode of travel to make observations about our late-modern, or cosmopolitan age, as well as about some of the subcultures surrounding adventurous, competitive, and alternative transport. They argue that one of the main lessons to arise from the era of mass hitchhiking during the mid-twentieth century is that the types of sensory knowledge acquired and passed on by hitchhikers themselves are unique in their spatio-temporal potential for being imaginatively transformed into tools for shaping wider socio-political projects. Contributing new and hitherto under-explored insights into the phenomenology of hitchhiking, the paper unpacks the ways in which this very particular form of transportation is part of a haptic form of knowledge production.

The final paper in the Special Issue is Wendelin Küpers’s Phenomenology of Embodied Detouring. Using a phenomenological and interdisciplinary approach, Küpers explores the embodied dimensions of place and movement as they relate to travel and tourism. The paper draws on the phenomenology of Merleau-Ponty to examine how the living body intermediates experiences of place and performed mobility across various touring modalities. Introducing the concept of embodied ‘de-touring’ as a distinct form of relationally placed mobility, the paper goes on to explore the notion of ‘heterotouropia’ and its connection to de-touring, and ideas of ‘other-placing’ and ‘other-moving’ as ways for engaging in indirect pathways. The paper concludes by presenting the implications, open questions and perspectives related to de-touring and sustainable forms of tourism mobility.

4. The Niagara River

- As though

- the river were

- a floor, we position

- our table and chairs

- upon it, eat, and

- have conversation.

- As it moves along,

- we notice—as

- calmly as though

- dining room paintings

- were being replaced—

- the changing scenes

- along the shore. We

- do know, we do

- know this is the

- Niagara River, but

- it is hard to remember

- what that means.

Kay Ryan, ‘The Niagara River’ (copyright © 2005 by Kay Ryan)

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: H.A. and L.R.; methodology: H.A. and L.R.; Formal analysis: H.A. and L.R.; writing—original draft preparation, review and editing: H.A. and L.R.; investigation: H.A. and L.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the poet Kay Ryan and Nancy Walker from Grove/Atlantic, Inc. for kindly granting permission to reproduce the poem ‘The Niagara River’, from () collection, The Niagara River (copyright © 2005 by Kay Ryan).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Adler, Judith. 1989. The Origins of Sightseeing. Annals of Tourism Research 16: 7–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altick, Richard Daniel. 1978. Shows of London. London: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, Hazel. 2005. Feeling at home. Embodying Britishness in a Spanish charter tourist resort. Tourist Studies 5: 247–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, Hazel. 2009. Tourism as a Moment of Being. Suomen Antropologi 34: 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, Hazel. 2017. Becoming Through Tourism: Imagination in Practice. Suomen Antropologi 42: 31–44. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin, Walter. 1968. Illuminations. Translated by Harry Zorn. New York: Schocken Books. [Google Scholar]

- Boorstin, Daniel J. 1992. The Image: A Guide to Pseudo-Events in America. New York: Vintage Books. [Google Scholar]

- Bruner, Edward M. 1986. Introduction: Experience and Its Expressions. In The Anthropology of Experience. Edited by Victor W. Turner and Edward M. Bruner. Chicago: University of Illinois Press, pp. 3–30. [Google Scholar]

- Bruner, Edward M. 2005. Culture on Tour: Ethnographies of Travel. Chicago: Chicago University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Certeau, Michel de. 1984. The Practice of Everyday Life. Translated by Steven F. Rendall. London: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Christie, Ian. 1994. The Last Machine: Early Cinema and the Birth of the Modern World. London: BFI/BBC. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, Erik. 1979. A Phenomenology of Tourist Experiences. Sociology 13: 179–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Erik. 1985. Tourism as Play. Religion 15: 291–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crouch, David. 1999. The Intimacy and Expansion of Space. In Leisure/tourism Geographies Practices and Geographical Knowledge. Edited by David Crouch. London: Routledge, pp. 257–76. [Google Scholar]

- Crouch, David. 2001. Spatialities and the Feeling of Doing. Social and Cultural Geography 2: 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crouch, David, Lars Aronsson, and Lage Wahltström. 2001. Tourist Encounters. Tourist Studies 1: 253–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crouch, David, Rhona Jackson, and Felix Thompson, eds. 2005. The Media and the Tourist Imagination: Converging Cultures. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Csordas, Thomas J. 1990. Embodiment as a Paradigm for Anthropology. Ethnos 18: 5–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csordas, Thomas J. 1994. Introduction: The Body as Representation and Being-in-the-world. In Embodiment and Experience: The Existential Ground of Culture and Self. Edited by Thomas J. Csordas. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Farman, Jason. 2021. Mobile Interface Theory: Embodied Space and Locative Media, 2nd ed. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Fielding, Raymond. 1983. Hale’s Tours: Ultrarealism in the Pre-1910 Motion Picture. In Film Before Griffith. Edited by John L. Fell. Berkeley: University of California Press, pp. 116–30. [Google Scholar]

- Friedberg, Anne. 1993. Window Shopping: Cinema and the Postmodern. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Frith, Jordan. 2015. Smartphones as Locative Media. Cambridge: Polity. [Google Scholar]

- Fussell, Paul. 1980. Abroad: British Literary Traveling Between the Wars. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Geertz, Clifford. 1986. Making Experience, Authoring Selves. In The Anthropology of Experience. Edited by Victor W. Turner and Edward M. Bruner. Chicago: University of Illinois Press, pp. 373–80. [Google Scholar]

- Gernsheim, Helmut, and Alison Gernsheim. 1968. L.J.M. Daguerre: The History of the Diorama and the Daguerreotype. New York: Dover Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, David, and Claire Hancock. 2006. New York City and the Transatlantic Imagination French and English Tourism and the Spectacle of the Modern Metropolis, 1893–1939. Journal of Urban History 33: 77–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Byung-Chul. 2017. The Scent of Time: A Philosophical Essay on the Art of Lingering. Translated by Daniel Steuer. Cambridge: Polity. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Byung-Chul. 2024. Vita Contemplativa: In Praise of Inactivity. Translated by Daniel Steuer. Cambridge: Polity. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, Julia. 2003. Being a Tourist: Finding Meaning in Pleasure Travel. Vancouver: Univeristy of British Columbia Press. [Google Scholar]

- Heidegger, Martin. 1971. ‘The Thing’. In Poetry, Language, Thought. Translated by Albert Hofstadter. New York: Harper & Row. [Google Scholar]

- Heidegger, Martin. 2005. Sojourns: The Journey to Greece. Translated by John Panteleimon Manoussakis. New York: State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hjorth, Larissa, and Sarah Pink. 2014. New visualities and the digital wayfarer: Reconceptualizing camera phone photography and locative media. Mobile Media & Communication 2: 40–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, George. 1992. Tourism and the Geographical Imagination. Leisure Studies 11: 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingold, Tim. 2000. The Perception of the Environment: Essays in Livelihood: Dwelling and Skill. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Ingold, Tim. 2012. Introduction. In Imagining Landscapes: Past, Present and Future. Edited by Monica Janowski and Tim Ingold. Farnham: Ashgate, pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Ingold, Tim. 2013. Dreaming of dragons: On the imagination of real life. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 19: 734–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, Michael. 1996. Introduction: Phenomenology, Radical Empiricism, and Anthropological Critique. In Things As They Are: New Directions in Phenomenological Anthropology. Edited by Michael Jackson. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indianan University Press, pp. 1–50. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, Michael. 2005. Existential Anthropology: Events, Exigencies and Effects. Oxford: Berghahn. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, Michael, and Albert Piette. 2015. Anthropology and the Existential Turn. In What is Existential Anthropology? Edited by Michael Jackson and Albert Piette. Oxford: Berghahn, pp. 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Kirby, Lynne. 1997. Parallel Tracks: The Railroad and Silent Cinema. Durham and London: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- MacCannell, Dean. 1976. The Tourist: A New Theory of the Leisure Class. London: Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- McLuhan, Marshall. 1964. Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man. New York: McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Merleau-Ponty, Maurice. 1968. The Visible and the Invisible. Translated by Alphonso Lingis. Evanston: Northwestern University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Merleau-Ponty, Maurice. 2014. Phenomenology of Perception. Translated by Donald A. Landes. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, Andrew J. 2023. Travels in Greece: Heidegger and Henry Miller. In Heidegger and Literary Studies. Edited by Andrew Benjamin. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Morley, David. 2009. For a Materialist, Non-Media-centric Media Studies. Television and New Media 10: 114–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ness, Sally Ann. 2016. Choreographies of Landscape: Signs of Performance in Yosemite National Park. New York: Berghahn. [Google Scholar]

- Ness, Sally Ann. 2020. Never Just an any body: Tourist encounters with wild bears in Yosemite National Park. In Tourism and Embodiment. Edited by Catherine Palmer and Hazel Andrews. London: Routledge, pp. 23–40. [Google Scholar]

- Nietzsche, Friedrich. 1996. Human, All Too Human: A Book for Free Spirits. Translated by R. J. Hollingdale. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Osborne, Peter D. 2000. Travelling Light: Photography, Travel and Visual Culture. Manchester: Manchester University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer, Catherine. 2018. Being and Dwelling Through Tourism: An Anthropological Perspective. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer, Catherine, and Hazel Andrews. 2020. Tourism and Embodiment: Animating the Field. In Tourism and Embodiment. Edited by Catherine Palmer and Hazel Andrews. London: Routledge, pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Pernecky, Tomas, and Tazim Jamal. 2010. (Hermeneutic) Phenomenology in tourism studies. Annals of Tourism Research 37: 1055–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pine, Joseph B., and James H. Gilmore. 1999. The Experience Economy. Boston: Harvard Business School Press. [Google Scholar]

- Prato, Paolo, and Gianluca Trivero. 1985. The Spectacle of Travel. Australian Journal of Cultural Studies 3: 25–43. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, Les. 2016. Deep Mapping and Spatial Anthropology. Humanities 5: 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, Les. 2018. Spatial Anthropology: Excursions in Liminal Space. London: Rowman and Littlefield. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, Kay. 2005. The Niagara River. New York: Grove Press. [Google Scholar]

- Salazar, Noel. 2010. Envisioning Eden: Mobilizing Imaginaries in Tourism and Beyond. Oxford: Berghahn. [Google Scholar]

- Salazar, Noel. 2012. Tourism Imaginaries: A Conceptual Approach. Annals of Tourism Research 39: 863–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar, Noel, and Nelson Graburn. 2014. Introduction: Toward an Anthropology of Tourism Imaginaries. In Tourism Imaginaries: Anthropological Approaches. Edited by Noel Salazar and Nelson Graburn. Oxford: Berghahn, pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Sallis, John. 2005. Foreword: A Philosophical Travelbook. In Sojourns: The Journey to Greece. Authored by Martin Heidegger. Translated by John Panteleimon Manoussakis. New York: State University of New York Press, pp. vii–xviii. [Google Scholar]

- Schivelbusch, Wolfgang. 1986. The Railway Journey: The Industrialisation of Time and Space in the 19th Century. Leamington Spa: Berg. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Barry, and David Woodruff Smith. 1995. Introduction. In The Cambridge Companion to Husserl. Edited by Barry Smith and David Woodruff Smith. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 1–44. [Google Scholar]

- Thrift, Nigel. 2007. Non-Representational Theory: Space, Politics, Affect. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, Victor W., and Edward M. Bruner, eds. 1986. The Anthropology of Experience. Chicago: University of Illinois Press. [Google Scholar]

- Urbain, Jean-Didier. 1989. The Tourist Adventure and His Images. Annals of Tourism Research 16: 106–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urie, Andrew. 2019. The Solace of the Sojourn: Towards a Praxis-oriented Phenomenological Methodology and Ethics of Deep Travel in Martin Heidegger’s Sojourns. Fast Capitalism 16: 141–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urry, John. 1990. The Tourist Gaze: Leisure and Travel in Contemporary Societies. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Urry, John. 1999. Sensing Leisure Spaces. In Leisure/tourism Geographies: Practices and Geographical Knowledge. Edited by David Crouch. London: Routledge, pp. 34–45. [Google Scholar]

- Vannini, Phillip. 2015. ‘Non-representational ethnography: New ways of animating lifeworlds’. Cultural Geographies 22: 317–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veijola, Soile, and Eeva Jokinen. 1994. The Body in Tourism. Theory, Culture and Society 11: 125–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).