Abstract

This essay analyzes Chinese theater director Li Jianjun’s play The Metamorphosis (Bianxingji) under Pierre Bourdieu’s idea of cultural capital. Reimagining Kafka’s Gregor Samsa as a package delivery rider in contemporary China, the play stages a failed narrative of storytelling through live-feed video and informs the impossibility of representing the riders’ labor resulting from the fragmented realities of postsocialist China. It thus challenges the middle-class writers’ efforts to transform delivery riders’ labor into a form of cultural capital and confronts the audience with the exploitative potential of their spectating position. Ultimately, the impossibility of representation staged by the play articulates the inequality and stratification that structures China at the postsocialist moment. The play interweaves three layers of narratives: Geligaoer’s family’s various forms of labor, documentary clips of real-life delivery riders in contemporary China, and an interplay between an external voice and the performers’ bodily movements. This layered narrative foregrounds the artificiality of storytelling and can be situated within the ongoing discussions in the recent decade in China, in which scholars and journalists attempt to secure their middle-class identities by transforming the riders’ laboring condition into a form of cultural capital. In contrast, the play stages the failure of the narrative of storytelling through a projection screen and live-feed cameras to inform the impossibility of a transparent representation of the delivery riders. By excluding the audience from the riders’ subjectivity, the play blocks the audience’s identification with the latter. Through the heavy beauty filter projected on the screen as a metaphor, the play confronts the audience with their own middle-class identity and warns them of the violence inherent in their spectating position.

“How can one reconcile the hard line inherent in any politics and the questioning essential to any relation? Only by understanding that it is impossible to reduce anyone, no matter who, to a truth he would not have generated on his own. That is, within the opacity of his time and place.”(Édouard Glissant, “For Opacity” p. 194)

“Concrete analysis means then: the relation to society as a whole. For only when this relation is established does the consciousness of their existence that men here have at any given time emerge in all its essential characteristics.”(Georg Lukács, “Class Consciousness”, Lukács 1971, p. 50)

In November 2024, a debate on food delivery riders attracted much attention on the Chinese Internet. The debate happened between Renwu magazine, a renowned Chinese magazine run by People’s Publishing House, and sociologist Sun Ping, a professor at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, over the authorship of a viral exposé titled “Delivery Riders, Stuck in the System” (Lai 2020). The exposé was written by journalist Lai Youxuan, contributed by Sun Ping, and published by Renwu in 2020. In brief, the 2024 debate started with Renwu accusing Sun Ping of misleading readers into considering her as the original author of the exposé. Within hours, Sun Ping refuted the accusation by explaining she never claimed to be the original author, although the exposé undeniably cited extensive ideas from her research.1

The latter half of Sun Ping’s short response, which insinuates how Renwu’s exposé has brushed off her contribution, reveals the real focus underlying the disputation. Ironically, it has become a competition over the authority to imagine, research, and represent the delivery riders as a form of knowledge and to claim the material profits to recycle and reproduce the exposé as its legitimate author. In other words, what is at stake in representing the riders is the middle-class writers’ own cultural capital, a form of capital that individuals from different classes have accumulated in the academic market since childhood, as theorized by sociologist Pierre Bourdieu in “The Forms of Capital” (Bourdieu 1986). Such tension between labor and its representation invites the following questions: How, if possible, do we configure a responsible and ethical representation of the delivery riders in contemporary China, a so-called “underclass” group of laborers usually represented by middle-class writers and rendered silent themselves? How may such a representation challenge the widening “class divide” in China and foster “cross-class solidarity” under the “rampant economic inequality” (Hillenbrand 2023, pp. 4–7, 34; Ferrari 2025, p. 4)?

To answer these questions, my essay focuses on Chinese theater director Li Jianjun’s (b. 1972) play, Bianxingji (The Metamorphosis, Li 2024). An adaptation of Franz Kafka’s The Metamorphosis (1915), Bianxingji reimagines Gregor Samsa as a package delivery rider named Geligaoer in contemporary China. The play was premiered in 2021 at the Aranya Theatre Festival in Qinhuangdao, China, and restaged in Beijing, Shenzhen, Shanghai, and Chengdu with minor revisions. My essay takes the play’s most recent restaging in September 2024 at the CPAA Theatre in Chengdu as an example. I argue that, through the use of a projection screen and a live-feed camera, Bianxingji stages a failed narrative of storytelling and informs the impossibility of representing the delivery riders’ labor rooted in the fragmented realities of postsocialist China. It thus challenges the middle-class writers’ efforts to transform the riders’ labor into cultural capital and confronts the audience with the exploitative potential of their spectating position. This interplay between the play and the middle-class authors’ debate eventually articulates and responds to the inequality and stratification that structures China at the postsocialist moment.

When illustrating how the play’s aesthetic choices intervene in the fractured reality of postsocialist China, I draw on philosopher Georg Lukács’s idea of “society as a concrete totality” to bridge the aesthetic and the political (Lukács 1971, p. 50). As Lukács has argued in History and Class Consciousness (1971), society is a “concrete totality” that consists of “the system of production at a given point in history and the resulting division of society into classes” (p. 50). To understand any cultural phenomenon within a society thus requires situating this phenomenon in the “total outer and inner life of society” under the “structural consequences” of the specific production system and class division at this moment (Lukács 1971, p. 84). More specifically, Lukács’s argument directs us to connect the delivery riders’ conditions, Li Jianjun’s play, and the middle-class writers’ competition over the exposé, considering all as embedded in and responsive to the inequality and social stratification since the mid-1990s in China. As sociologist Xiaogang Wu has pointed out, such inequality and stratification are shaped by both the state’s transition to market economy and its subsequent economic growth and the structural changes in institutions such as the household registration system (hukou). Both have led to “societal polarization between the rich and poor” in China, resulting in the rise of China’s new middle classes possessing “more cultural and economic resources” and that of “a new working class” comprising rural migrants with less educational opportunities and social mobility (X. Wu 2019, pp. 371–73). It is within this macroscopic context that the three phenomena become legible as interconnected responses to the totality of the postsocialist moment.

Under this framework, I use three complementary theoretical lenses to ground my analysis. First, philosopher Édouard Glissant’s idea of “opacity” resists efforts to “reduce things to the Transparent” and instead subsists on the “irreducible singularity” as the “foundation of Relation” (Glissant 1994, pp. 189–90). The idea of opacity offers a vocabulary to identify the overarching problematic of this essay, namely the impossibility for middle-class writers to represent delivery riders resulting from the huge class divide in contemporary China. On a more specific level, Bourdieu’s theory of “cultural capital” brings to light what will happen when middle-class writers attempt to grasp and represent the riders’ laboring conditions. Although Bourdieu’s theory of “cultural capital” was theorized based on the realities of twentieth-century Europe, I apply it in my analysis of contemporary China because the postsocialist totality similarly witnesses how capital presents itself in the guise of individual achievement and “educational qualification” (Bourdieu 1986, p. 243). In particular, cultural capital serves as a useful theoretical tool to analyze how the debate between Renwu and Sun Ping became a competition over the authority to represent the riders and claim the material profits underlying the exposé’s authorship. To tie together the debate and Li’s play, I further borrow from playwright Bertolt Brecht’s theorization of the “alienation effect” when conducting textual analysis. By examining how the play repurposes the alienation effect to initiate a self-critique of the middle-class writers and audience, I address the play’s social intervention and artistic contribution underlying its highlighting of the impossibility of representation through the use of stage technologies. Together, these three theoretical lenses concretize Lukács’s idea of “society as a concrete totality,” grounding the essay’s intervention that stage technology operates as a central agent in the play’s response to the issue of labor, representation, and class divide in the postsocialist totality.

To structure my essay, I first examine how Bianxingji interweaves three layers of narratives and informs the artificiality of storytelling. Alongside the diegesis of how Geligaoer and his family perform multiple forms of labor, the play overlays a second layer of narrative constituted by documentary clips of real-life delivery riders and a third layer of narrative of storytelling itself. As the performers assume the external voice of a narrator, they simultaneously ventriloquize this narrator with their bodily movements. These arrangements achieve storytelling through the separation of voice and visualization and inform the artificiality of storytelling. Then, I contextualize the play’s layered narrative of storytelling into the ongoing discussions in the recent decade in China, in which scholars and journalists pay increasing attention to the food and package delivery riders. As the riders’ “transitional labor” reminds the middle-class writers of a similar possibility of class downfall and a sense of precarity, the latter attempts to secure their middle-class identities by understanding and grasping the riders as an Other (Sun 2024, p. 3). Against this context, I read the debate between Renwu and Sun Ping as a competition over cultural capital, which implicates both symbolic capital, namely the authority to represent the delivery riders as a form of knowledge, and economic capital, as the legitimate author can reproduce the exposé as a profitable cultural good to sustain their middle-class living conditions. The last part of my essay analyzes how the play employs a live-feed camera and stage-wide projection screen to challenge the middle-class writers’ efforts to represent and commodify the riders. Through Geligaoer’s soliloquy delivered in Shanxi dialect, the play excludes the audience from the riders’ subjectivity and blocks the audience’s identification with the latter. Further, through the heavy beauty filter projected on the projection screen as a metaphor, the play confronts the audience with their own middle-class identity and warns them of the violence inherent in their spectating position.

1. The Artificiality of Storytelling: The Multi-Layered Narrative in Bianxingji

Born in 1972, Li Jianjun started working as an independent theater director in 2007 and founded his own theater company called the New Youth Group in Beijing in 2011. Having worked as a set designer before his directing career, Li’s plays are marked by his use of digital technologies onstage, such as chroma key compositing and live-feed video. These unique configurations of scenography have established Li as a key figure of “the New Generation of Chinese Directors” dubbed by Xi Muliang and Annie Feng, a younger generation of theater directors mostly born after 1978. Under the maturing of Chinese theater market and the influence of the previous generation of directors, such as Meng Jinghui (b. 1964), Li and his cohort use “formal experimentation” to respond to “the contingency and complexity of a fragmented reality” in twenty-first-century China (Xi and Feng 2018, para 1–4, 9; Ferrari 2025, p. 31).

More specifically, these fragments of reality that the New Generation work with are embedded in the “historical condition and affective structure” of Chinese postsocialism. As scholars have theorized, this postsocialist era is marked by the coexistence of the specters of a totalizing socialist regime and “new globalised values and behaviours” dominated by the uneven logic of late capitalism (Ferrari 2025, p. 3). Such unnamed complexity requires Chinese postsocialism to be staged through an aesthetic style theorized by Rossella Ferrari as “postdramatic,” which challenges mimetic realism by presenting a lived reality that is observed and “experienced and expressed through the body” (Ferrari 2025, p. 32). Echoing this postdramatic style, Li Jianjun’s iconic scenography similarly “argues for a perception of reality as an agentive process of ‘becoming’ (real)” (Ferrari 2025, p. 32), as exemplified by his “posthuman trilogy.” The trilogy includes three plays produced during the COVID-19 pandemic: Shijie danxi zhijian (World on a Wire, 2021), Bianxingji (The Metamorphosis), Dashi yu magelite (The Master and Margarita, 2022), all localizing canonical texts in contemporary China through a surrealist lens. Among these three plays, I choose Bianxingji as the focus of my analysis because its “dramaturgy of precarity,” which pays attention to and deliberately intervenes in “underrepresented experiences of economic inequality and civic marginalisation affecting subaltern social groups” (Ferrari 2025, p. 33).

In particular, Bianxingji projects documentary clips and live-feed videos onstage via a stage-wide projection screen to interweave three layers of narratives. The play’s main diegesis follows Geligaoer (performed by Li Jialong) and his family, whose lives revolve around multiple forms of labor. Just as Gregor in Kafka’s The Metamorphosis, Geligaoer finds himself having turned into a huge insect on a random morning. As his family loses any financial support, they start considering getting rid of Geligaoer, who has now become a burden, while seeking jobs to earn money and make a living. As one attempt at survival, Geligaoer’s sister Meimei (performed by He Wenjun) becomes a TikTok live-streamer, assisted by their parents (performed by Cui Wei and Xia Xin).2 Just as their live-streaming career takes off, Geligaoer intrudes into one of their live-streamings. Despite Meimei and the parents’ panic, the grotesque spectacle attracts the audience and goes viral. Eventually, Geligaoer dies, and the family reanimates him as a digital avatar that supports their live-streaming career.

This diegesis is interwoven with documentary clips of real-life package delivery riders and other precarious laborers in contemporary China, layering another narrative to contextualize Geligaoer’s story. For example, in the play’s opening, multiple photos documenting a delivery rider’s daily routine are projected right after texts on the screen announce Geligaoer’s transformation (Figure 1). In the scene, the four performers featuring Geligaoer and his family stand still closely in front of the stage-wide projection screen, with three huge, documentary-style photos organized in a four-cell grid overshadowing their faces and bodies. In particular, the lower-left photo shows a delivery rider riding a motorcycle alone through a heavy smog in the middle of the street. Complementing this image, the lower-right photo captures the sun beaming and rising above the darkened urban landscape, whose contrast implies the strenuous working schedule of delivery riders that normally starts at six in the morning.3 Simultaneously, the upper-right photo shows the riders’ working place, namely, the distribution stations (zhandian) crowded with riders, motorcycles, and parcels. The large-sized photos placed alongside each other piece together the riders’ laboring conditions, directing the audience to the reality in which Geligaoer lives.

Figure 1.

The photos communicate details of a delivery rider’s everyday life. Bianxingji (2024). Performed by Li Jialong et al. at the CPAA Theatre, Chengdu, China. (Photo courtesy of Li Jianjun and the New Youth Group).

This “documentary” narrative collaged through the photos accompanies and complements the main diegesis. As the photos swiftly switch to other photos zooming in on the riders’ everyday lives, such as the bulk of packages carried on their narrow and wavering motorcycles, there is always one piece of the screen left blank. With its striking visibility in contrast to the photos, the blank space implies the incompleteness of the picture, which can only be finished by putting in the last piece of the jigsaw, namely, Geligaoer’s story that is being staged. As such, the scene interweaves Geligaoer’s story with a background narrative focusing on the laboring conditions of the delivery riders. On the one hand, such interweaving prompts the audience to understand and contextualize Geligaoer’s story within the riders’ laboring conditions. On the other hand, it invites the audience to understand the delivery riders’ everyday experiences by referencing the surreal, fantasy narratives borrowing from The Metamorphosis and implying the surrealness and absurdity of such experiences.

Further, the play communicates a narrative of storytelling itself through the performers’ configuration of an external voice and their bodily movements animated by this voice. In a sequence of scenes following the documentary-style photos, the performers take turns to deliver a long monolog after Geligaoer’s transformation:

Geligaoer: Should I keep sleeping?

Meimei: I am used to sleeping on my right side.

Mama (Geligaoer’s mother): How do I turn to the right side?

Baba (Geligaoer’s father): My back is no longer flat. It has become a beetle’s exoskeleton.

Geligaoer: When did my legs turn so tiny?

Meimei: One, two, three, four…

Mama: I can’t count how many legs I have.

Baba: I won’t see them if I close my eyes.

Geligaoer: There is nothing more exhausting than delivering packages. I wake up at six, head out at six twenty, ride for seven and a half miles, load the packages, and deliver them for the entire day until ten at night.

Meimei: I say the same thing to everyone I meet: Hi, your package has arrived; what is your name and the last four digits of your phone number?

Mama: Even though I know their names, addresses, and phone numbers, we are forever strangers.

Baba: My belly is itchy. It is covered by tiny white spots.

Meimei: Gross!4

Using “I” as the only pronoun to keep the speech flowing, the four performers assume Geligaoer’s perspective in the first segment of the monolog, where Geligaoer painfully adjusts to his new insect body. Then, from the line “there is nothing more exhausting than delivering packages,” this perspective shifts as Geligaoer’s performer Li Jialong assumes another identity, namely, that of a delivery rider living in contemporary China. This transitional line leads to the second segment of the monolog, which follows this delivery rider’s perspective and describes the dull and unmeaningful life he lives everyday. However, the perspective shifts back to Geligaoer as Baba’s performer Cui Wei directs the monolog back to the physical pain of living in an insect body with the line “my belly is itchy,” which marks the third segment of the monolog. As the voice switches freely back and forth between the perspectives of Geligaoer and a real-life delivery rider, it visualizes a montage-like sequence of cinematic shots that synthesize the documentary clips and the fantasy story. The voice thus resembles an external narrator that “floats” above the stage without being confined to a single perspective.

This external narrator animates the performers’ movements and transforms the performers into puppets ventriloquizing the voice. Accompanying the monolog, the performers move in front of the projection screen, issuing a series of gestures. First, they crawl and roll on the ground in distorted gestures that resemble the movements of insects. Then, with their backs leaning and rubbing on the projection screen, they slowly struggle to stand up. Under the same rhythm exteriorized by a loud soundtrack mimicking human heartbeats, the performers’ gestures again resemble each other, constituting a choreography that visualizes the pain and struggling communicated by the voice. The performers thus become puppet-like figures, each being wrapped in distinct costumes yet all ventriloquizing the external narrator’s voice. In this regard, they resemble the figures in Chinese shadow theater, which are manipulated through a “flexible central rod” by a shadow master, who also performs singing and the figures’ dialogs (Chen 2007, p. 7). Through the separation of voice and visualization, the scene refers to the shadow theater, implying the similar presence of a “puppet master,” namely, a narrator and manipulator behind the performance. The scene thus highlights both the framework of storytelling that seemingly totalizes the performance and the artificiality of this framework.

Such highlighting of the artificiality of storytelling could be befuddling: why would the play interweave a narrative of storytelling into those of Geligaoer and delivery riders in China? Is this narrative “redundant,” merely serving to “show off” the director’s sophisticated stage design and use of technology, as some reviews have criticized?5 In the following sections, I read this narrative of the artificiality of storytelling by situating it in the ongoing discussions in the recent decade in China, in which scholars, journalists, and filmmakers pay increasing attention to the delivery riders.6 As I would argue in the last section of this essay, it is precisely through the fractured relationship between this narrative of storytelling and the main diegesis about Geligaoer that Bianxingji intervenes in these debates in a critical tone.

2. Representing Delivery Riders: Competition over Cultural Capital

In the recent decade, the living and laboring conditions of food and package delivery riders have attracted much scholarly attention in China. For instance, Chris King-chi Chan et al. have identified multiple incidents of suicide of delivery riders and situated these tragic events in the “twenty-first-century platformisation of the Chinese economy” (Chan et al. 2021, p. 3). Huang Hui has specified issues the delivery riders encounter on a daily basis, such as “physical risks,” “work insecurity,” and “livelihood crisis” (Huang 2022, p. 351). Hong Yu Liu has connected these crises to the “labor regulatory framework that governs China’s platform economy” (Liu 2024, p. 55). Moreover, Sun Ping, one of the protagonists in the debate mentioned at this essay’s beginning, has conducted extensive research on the riders since 2017, when Chinese delivery platforms such as Meituan and Ele.me started proliferating.7 In particular, Sun characterizes the labor performed by delivery riders as a form of “transitional labor” (Sun 2024, p. 3).8 As Sun has observed, the burgeoning of the global and domestic “on-demand economy” has encouraged Chinese rural migrant laborers to join the food and package delivery industries to make a living in the face of an uncertain future (Sun 2019, p. 308). The delivery riders see the job as temporary, and their laboring and living conditions are marked by a sense of uncertainty.

This sense of uncertainty manifests in the delivery riders’ both laboring and living conditions. As the riders negotiate with the infiltration of algorithms that aim to control their labor, they inevitably participate in the “transitional mechanism” designed by platforms, which forces the laborers to secure their income through intensive competition and calculation. Paradoxically, such efforts to secure an income usually lead the riders to quit the job eventually because the competition is too consuming. Simultaneously, the riders’ everyday lives, which are intertwined with their labor, are also transient. For instance, the urban villages where the delivery riders usually gather are temporary residential spaces subjected to demolition. The state’s hukou system and the high living costs in urban areas further render the city a transient living space for the riders, who mostly migrate from rural areas (Sun 2024, pp. 12–17, 222–29).

Such transitional labor performed by delivery riders must be considered within an overall “ambient mood of civic jeopardy,” which Margaret Hillenbrand captures with the keyword “precarity.” According to Hillenbrand, precarity refers to both a laboring condition and “an ontological state” of unbelonging, dispossession, and disenfranchisement. In particular, it is a social group dubbed as diceng (underclass) that constitutes the “most precarious” people in contemporary China (Hillenbrand 2023, pp. xii–xv). “An artificial edifice” constructed by “governmental policy since the 1990s,” the Chinese underclass includes various social groups having fallen into indigence and abjection, such as migrant workers (including delivery riders), landless peasants, and “tuwei” (lowbrow and bawdy) live-streamers subjected to “abjection” (Hillenbrand 2023, pp. 7, 208), as exemplified by Meimei in Bianxingji. Although believed by many to be an “ugly word,” Hillenbrand adopts “underclass” deliberately to identify a “logic of expulsion” effected to segregate these populations, ranging from the government’s labeling as “low-end population” and the other social groups’ perception as lacking “suzhi” (“human quality”) (Hillenbrand 2023, p. 8). Yet, with their vast size and striking visibility, the underclass poses a disturbing question to the Chinese middle class attempting to un-see and expel: who is next to become absorbed into them? Such “fear of the cliff edge” has prompted the middle class, such as “cultural creatives, IT employees,” and “white-collar workers,” to both differentiate themselves from the “underclass,” designating the latter as an “Other,” and to imagine, understand, and consume them as a form of knowledge (Hillenbrand 2023, p. xvi).

Although I do not intend to brush off the efforts of middle-class authors to comprehend the delivery riders’ living and working conditions, nor do I dismiss their capacities for empathetic engagement, I propose to read the debate between Renwu and Sun Ping against the above context as a competition over the authority to represent the delivery riders. As Georg Lukács has noted, bourgeois thought can neither “grasp the contradictions inherent in its own social order” nor discover the “theoretical and practical solutions to the problems created by the capitalist system of production” due to their failure to “advance beyond the mere ‘individuality’ of the various epochs and their social and human representatives” (Lukács 1971, pp. 48, 62–63). A more productive reading of the debate thus requires us to understand how the middle-class authors emphasize and represent the delivery riders in order to grasp the latter as a form of knowledge, which can transform into cultural capital and serve to secure their own middle-class identities. In “The Forms of Capital” (Bourdieu 1986), Pierre Bourdieu defines cultural capital as a form of capital rooted in economic capital yet manifested in a “transformed, disguised” form (p. 252). More specifically, cultural capital refers to the profits that individuals from different classes have obtained in the academic market since childhood, which contribute to the “reproduction of the social structure.” In particular, the authorship of the 2020 exposé constitutes the “objective state” of cultural capital, namely, cultural capital objectified into material objects such as writing. What is at stake in owning cultural capital in its objective state, as Bourdieu notes, is the competence to produce, appropriate, and use the cultural products “in accordance with their specific purpose.” Such competence then “derives a scarcity value from its position in the distribution of cultural capital,” yielding symbolic and material “profits of distinction” for its owner (Bourdieu 1986, pp. 243–47). In this regard, the focus of Renwu and Sun Ping’s debate moves beyond the authorship of the exposé. It becomes a competition over cultural capital, which implicates both symbolic capital, namely, the authority to represent the delivery riders as a form of knowledge, and economic capital, as the legitimate author can recycle and reproduce the exposé as a profitable cultural good to sustain their middle-class living conditions.

This competition over the symbolic and economic capital runs through both parties’ discourses in the debate. In “Statements on ‘Delivery Riders, Stuck in the System (2024)’” (hereafter “Statements,” 2024), the trigger of the 2024 debate, Renwu asserts in bold font: “‘Delivery Riders, Stuck in the System (2024)’” is Renwu’s original topic. It was independently conducted by author Lai Youxuan and editor Zhang Yue through their labor over sixteen months.” Notably, the product of Lai and Zhang’s “independent labor” involves not only the exposé’s “original topic” on delivery riders’ laboring conditions but also the methods to research and represent the riders. As highlighted in the timeline attached to “Statements,” these methods include “to observe news reports,” “to interview the riders,” “to conclude that delivery riders are manipulated by algorithms,” and “to conduct the writing.” By choreographing a series of verbs in bullet points, “Statements” offers a linear narrative on how Lai and Zhang conceived of and enacted the project. It thus designates the exposé as a form of knowledge produced by Renwu and Lai Youxuan, who assume the role of knowledge producers and own the authority to represent the riders.

As the other party of the debate, Sun Ping similarly packages and appropriates the rider’s laboring conditions as a form of knowledge targeted at the middle-class audience. On Sun’s personal account at Xiaohongshu, one of the most popular Chinese social media and e-commerce platforms, a post titled “Sharing my research” is pinned to her profile. The post’s cover picture is a screenshot of Sun’s article on female delivery riders published by a Chinese academic journal in September 2024. Across the screenshot, a sentence highlighted in huge, pink fonts overshadows the article’s content and demands the viewers’ attention: “How female delivery riders became an article in a top academic journal.” The verb “become” frames female delivery riders as the material processed to contribute to an end, namely, “an article in a top academic journal.” It thus promotes Sun’s research as a form of middle-class knowledge that not only grasps the riders’ laboring conditions but also offers instructions to conduct publishable academic writing, revealing its potential audience as sociology students who have already possessed some cultural capital in its “institutionalized state,” namely, academic qualifications (Bourdieu 1986, p. 247). Addressing these future qualification holders, the post writes:

I was wondering, how does a woman survive in the delivery industry full of men? [...] After several interviews, I discovered that a woman must adjust her identity when becoming a delivery rider. [...] I thus developed a clearer research question: how do female delivery riders perform their gender at the intersection of the platform economy and gender?(Sheke Sun Ping 2024)

In an assertive and instructional tone, the post takes a first-person perspective to narrate how Sun transforms the female riders’ laboring conditions into an article step by step. These practical tips then attract sociology students, who address Sun as “Professor Sun” (Sun laoshi) in a respectful tone in the comment section. As such, the post pinpoints Sun as an authoritative knowledge producer owning the cultural capital to represent the riders and instruct the students.

Ultimately, such symbolic capital contested by both parties serves to produce economic capital, as evidenced by the other focus of the debate: the media sensation and industrial changes instigated by the exposé. When defending the exposé’s authorship against Sun Ping’s “act of plunder,” “Statement” argues: “What is at stake is that it was not until the exposé’s release that the issues of platform economy, algorithms, and the riders’ living conditions became a social hotspot. [...] It was the exposé that triggered heated discussions and industrial changes.” This emphasis on the exposé’s viral influence is reiterated at the end of “Statement”: “We ask all parties, whenever the exposé is mentioned again, especially in promotional and marketing activities, to cite its source honestly.” By situating the exposé as the catalyst of a chain of cultural and economic phenomena, ranging from media reports to industrial changes, “Statements” identifies the larger stake associated with the exposé’s authorship. Namely, it has become the right to claim the industrial impact and material benefits the exposé has generated, and recycle and reproduce these benefits as the exposé becomes a cultural commodity.

Such efforts to commodify the riders’ laboring conditions can be seen on Sun’s Xiaohongshu account, which monetizes the internet traffic attracted by Sun’s promotion of her research. The post analyzed above, for instance, has attracted over two thousand likes from Xiaohongshu, “a vast repository” of online users and traffic (Jamerson 2017, p. 121). Under the texts, the interface’s lower-left corner shows a thumbnail of the cover of Sun’s monograph, Transitional Labor (Guodu laodong, 2024), alongside an icon that says “Buy it.” With a click, the viewers are directed to the online shopping site embedded within Xiaohongshu, where they can purchase the book. As a marketing strategy, the post subtly transforms Sun’s research project into a commodity and the riders’ laboring condition as a form of lucrative information, both ready to be consumed by the academic and literary markets. It not only conforms to the logic through which Xiaohongshu markets the content and commodities but also reinforces Sun’s status as an “informational authority” (Jamerson 2017, p. 127). The debate on exposé’s authorship and its representation of the delivery riders thus reveals its goal as a competition over the economic capital converted from cultural capital.

3. Beyond Alienation: The Impossibility of Representation

Bianxingji challenges these efforts to represent and monetize the delivery riders and their labor by staging the failure of storytelling and informing the impossibility of representation. In particular, the play channels and expands the alienation effect in Bertolt Brecht’s epic theater. In a series of essays published from the 1920s to the 1940s, Brecht proposed a new form of theater, which he dubs “epic theater,” to challenge the bourgeois theater and to effect a social critique corresponding to “the whole radical transformation of the mentality” of his time (23). Whereas the bourgeois theater maintains the illusion of a universal human subject via techniques such as the fourth wall, the epic theater breaks this illusion through what Brecht calls the “alienation effect.” Through the breakdown of the fourth wall and the rearrangement of the music and the scenography, the alienation effect hinders the audience from “identifying itself with the characters in the play” and blocks their “automatic transfer of emotions” from the latter. The audience is thus expected to “come to grips with things” with reason (Brecht 1957, pp. 38–39, 91–94).

Whereas Brecht’s epic theater aims to exert a social function that instructs the audience to “observe” and “put morals and sentimentality on view” (Brecht 1957, p. 75), Li’s play replaces this goal of political critique with self-critique on the audience’s part. More specifically, Bianxingji complicates Brecht’s alienation effect by first inviting the audience’s identification yet making it fail. After Geligaoer’s metamorphosis, he loses everything: his body, job, mobility, and language. Such isolation is conveyed by the performers’ narration, as they take turns imitating the voice of the external narrator; it then reaches a climax in the following scene. Downstage, Geligaoer painfully rolls on the ground, with his body curled and wrapped in a pile of clothes that his family throws at him in abjection. On stage left, the other three family members sit together, avoiding looking at Geligaoer as if he were invisible. Simultaneously, the background music features a slow, melancholic piano song, and a documentary clip of a delivery rider riding a motorbike across the street alone plays on the projection screen. The coordination of the performance, music, and documentary clip submits the audience to a sentimental imagination of Geligaoer and the rider onscreen, evoking the audience’s identification with them.

However, the audience’s illusion of identification is disrupted as Geligaoer starts delivering a soliloquy in the Shanxi dialect, a dialect from northern China, that lasts for over three minutes. The soliloquy confuses the audience in Chengdu, who are mostly Southwestern Mandarin speakers.9 Mediated by the “unfathomable” Shanxi dialect, the soliloquy throws the audience into an awkward position. As “invited” by the previous sentimental ambiance, the audience is already halfway into a shared subjectivity of Geligaoer and the rider. However, as this shared subjectivity keeps formulating onstage, the audience suddenly finds themselves rejected from further entering it, as the Shanxi dialect renders Geligaoer’s soliloquy inaccessible. The scene thus blocks the audience from entering the shared subjectivity and identifying with Geligaoer and the riders. It also complicates the observer position Brecht assigns to the audience by forcing the latter to observe not only what happens onstage but also their own attempts to identify and emphasize. By confronting the audience with the failure of these attempts, the scene mocks them as middle-class theater-goers, whose fantasy of identifying with the “underclass” usually ends in vain.

Further, the play warns the audience of the potential cruelty of their attempts at identification, which can be consumptive and exploitative, merely serving to soothe their own fear of precarity. In the play’s latter half, Meimei becomes a TikTok livestreamer to support the family. Wearing a blue wig in front of a camera mounted on a tripod stand with a ring light, Meimei’s image is framed in TikTok’s 9:16 interface and projected on the stage-wide screen. A heavy beauty filter enlarges her eyes, slims her jawline, and smooths her skin, shaping her as a wanghong (internet celebrity) livestreamer on TikTok. As Meimei’s overly retouched image centered in vertical format on the projection screen takes the foreground, she also hails the audience as “families and friends,” a common usage to address the viewers in livestreaming. As such, the scene reassigns the audience of the play to that of the livestreaming.

This identity transition offers the audience an illusion of agency, which seems to align them with the play’s omniscient narrator but indeed choreographs them as actors within the diegesis. As livestreaming viewers, the audience is scripted to keep the performance flowing: they participate both onstage, moving their bodies to the rhythm of Meimei’s singing, and onscreen, posting comments and danmaku subtitling.10 Following their participation, however, the audience is then toggled back as the spectators of the play. During the livestreaming, Geligaoer, who fainted downstage, suddenly wakes up and approaches Meimei, who turns off the camera in panic. As the live-feed video disappears, the projection screen becomes dimmed and backgrounded, redirecting the audience’s attention back to the stage and pushing them back as the spectators of the play. As such, the audience’s agency is contingent on scripting and can be disrupted and revoked at any time, despite seemingly occupying a safe and flexible position accessible to various perspectives of seeing.

This position of seeing collapses at the moment when Geligaoer intrudes into the livestreaming camera. Directly staring into the camera, Geligaoer shouts in despair: “Stop entertaining them! They will give you nothing. They know nothing about what you are singing. They are consuming you!” By starting almost every segment of the sentence with the pronoun “they,” Geligaoer announces his awareness of the presence of the audience, whom he considers to be exploitative consumers instead of innocent observers. As Geligaoer gazes back at the audience, the audience’s illusion of occupying a safe spectating position is subjected to scrutiny. Crucially, this spectating position hinges on the audience’s cultural capital that authorizes them as qualified theater-goers to consume and appreciate the play as a cultural commodity. The play thus folds the audience into Renwu and Sun Ping’s competition over the cultural capital to represent and grasp the delivery riders. In other words, it identifies the audience as middle-class consumers whose empathy for the riders operates as a consumption of commodified knowledge and helps reproduce the cultural capital owned by the informational authority.

Indeed, the site of the play’s 2021 premiere, the Aranya Theatre Festival in Qinhuangdao, constitutes a middle-class carnival of consumption. Commenced in June 2021, the festival is located in the Aranya Resort, “an economic and cultural exclave” capitalizing on the trend of “cultural tourism real estate” in post-pandemic China. Namely, the resort not only sells real estate properties but also offers “a groundbreaking form of community organization” and “popular leisure options” such as beach sidewalks and the view of European-style architecture. Due to its close distance to Beijing, the resort has become “an oasis for the burgeoning neo-middle class of Beijing and its neighboring cities” (Cheng and Lu 2024, p. 47). The theater festival held here, specifically, features dozens of domestic and international theatrical productions every year. As of its 2023 appearance, the festival attracted “more than 40,000 theater-goers and 330,000 visitors” as potential homeowners and boosted hotel prices nearby to $400 per night (D. Wu 2023). In the long term, the resort’s housing prices have soared from roughly $1400/m2 as of 2020 to $3200/m2 as of 2025, with its development having expanded from Phase I to Phase IX (Aranya n.d.a and Aranya n.d.b).11 The Aranya resort can thus be considered as a market of both cultural goods and real estate properties, witnessing how the staging of theatrical productions circulates as a commodity and becomes accumulated as economic capital.

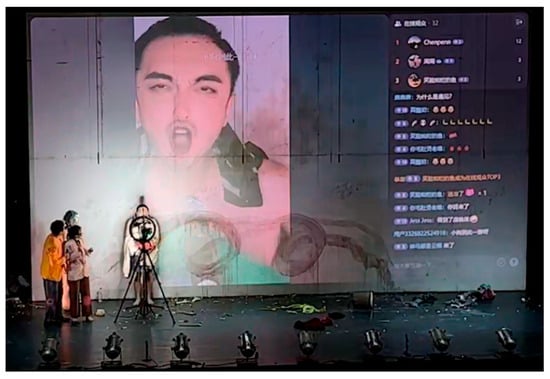

In this market, the audience assumes the role of consumers whose gaze at the delivery riders is subjected to multiple layers of mediation and rendered unreliable, as exemplified by the above scene. Centered on TikTok’s interface, Geligaoer’s face is retouched by the same beauty filter that airbrushed Meimei’s image, with exaggerated makeup effects distorting his furious facial expressions (Figure 2). The contrast between the filter and Geligaoer’s anger creates a sense of absurdity, eliciting the audience’s laughter yet serving as a metaphor for their middle-class position and their efforts to grasp Geligaoer and Meimei’s living conditions. Just like the beauty filter awkwardly following to fit in, mediate, and distort Geligaoer and Meimei’s images, the middle-class theater-goers fantasize and consume the living conditions of delivery riders and livestreamers as a commodity that reinforces their own cultural capital. These attempts at seeing not only end in inaccuracy instead of transparency but also constitute an exploitation of the latter. Ironically, what is unmediated by the filter is the comments and subtitling superimposed onto and juxtaposed alongside the image, which evidence the audience’s attempts to see and grasp Meimei and Geligaoer. By returning the trace of their acts of seeing, the scene warns the audience of the potential cruelty and exploitation underlying the previously evoked empathy.

Figure 2.

Geligaoer intrudes into the camera with his face being retouched by the beauty filter. Bianxingji (2024). Performed by Li Jialong et al. at the CPAA Theatre, Chengdu, China. (Photo courtesy of Li Jianjun and the New Youth Group).

4. Conclusions

In Poetics of Relation (Glissant 1994), Édouard Glissant writes, “We clamor for the right to opacity for everyone” (p. 194). Indeed, Glissant’s claim illuminates the social and political stakes of Li Jianjun’s Bianxingji, as the latter manages to maintain such opacity for delivery riders in contemporary China by staging the artificiality of storytelling, blocking the audience’s identification with the characters, and gazing back at the audience’s spectating positions. As such, I conclude that the play offers a playful yet critical comment on the middle-class writers’ competition over the authority of the delivery riders, proposing an alternative to such efforts. Paradoxically, the only way to deliver a representation of the latter without reducing them to transparency is to acknowledge the impossibility of fully understanding them, and it is precisely through such acknowledgments that the representation can start to be responsible.

A nexus of aesthetic production, cultural capital, and precarious labor, the impossibility of representation staged by the play ultimately operates as a key to accessing the fragmented realities of contemporary China. It connects the fragments under the totality of the postsocialist moment structured by inequality and stratification. In conclusion, the play’s insistence on the impossibility of representation should be considered not an arbitrary aesthetic choice but an intentional gesture responding to these fragmented realities and the totality in which they are embedded. As a representative of postsocialist postdramatic theater, the play makes a bold statement to theorize the impossibility of representing such fractured realities while trying to articulate the social and economic precarity undergirding this moment.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares not conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | See “Statements on “Delivery Riders, Stuck in the System (2024)” and “Response.” |

| 2 | Li Jialong, He Wenjun, Cui Wei, and Xia Xin are all performers in the New Youth Group. |

| 3 | Bianxingji, 00:05:19. |

| 4 | Bianxingji, 00:04:37–00:05:56. |

| 5 | For example, on Bianxingji’s homepage on Douban website, a platform where users can leave comments on books and films, a user comments: “Some movements of the performers are weird and redundant;” “The live-streaming section in the latter half of the play is between on-point and showing-off.” |

| 6 | Director Xu Zheng’s (b. 1972) film Nixing rensheng (Upstream, 2024) exemplifies that filmmakers are also paying attention to delivery riders. Other literary works centered on delivery riders include Hu Anyan’s (b. 1979) autobiography Wo zai Beijing songkuaidi (I delivered packages in Beijing, 2023) and Wang Jibing’s (b. 1969) collection of poems, Ganshijian de ren: yige waimaiyuan de shi (One who races the time: Poetry of a food delivery rider, 2023). |

| 7 | For more information on the Chinese delivery platforms, see (Sun 2019, p. 309). |

| 8 | Sun’s 2024 monograph is written in Mandarin, although she translates several important terms, such as “transitional labor,” into English. The passages cited in this essay are translated into English by myself. |

| 9 | This can be exemplified by a conversation between the crew member and the audience after the end of the play. As one audience asked what the monologue was about, the performer explained that it was about a delivery rider’s experience during the COVID-19 pandemic. |

| 10 | Danmaku subtitling refers to scenarios where online video viewers post “‘live’ comments overlaid on the screen” (Yang 2019, p. 2). |

| 11 | See Aranya (n.d.a) for statistics by real-estate site Anjuke for the resort’s housing prices as of 2025. See Aranya (n.d.b) for statistics by real-estate site Juhui shuju for the resort’s housing prices as of 2021. |

References

- Anaya Aranya 阿那亚 Aranya [Aranya] Anjuke. n.d.a. Available online: https://qhd.fang.anjuke.com/loupan/jiage-259934.html (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Anaya Aranya 阿那亚 Aranya [Aranya] Juhui shuju. n.d.b. Available online: https://fangjia.gotohui.com/info-136015.html (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1986. The Forms of Capital. In Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education. Edited by John. G. Richardson. New York: Greenwood Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brecht, Bertolt. 1957. Brecht on Theatre: The Development of an Aesthetic. Edited and Translated by John Willett. New Delhi: Radha Krishna Prakashan. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, Christ King-chi, Eric Florence, and Jack Linchuan Qiu. 2021. Precarity, Platforms, and Agency: The Multiplication of Chinese Labour. China Perspectives 1: 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Fan Pen Li. 2007. The Chinese Shadow Theatre: History, Popular Religion and Women Warriors. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Zhen, and Eason Lu. 2024. Avant-Garde Heterotopia. PAJ: A Journal of Performance and Art 46: 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delivery Riders, Stuck in the System. 2024. Guanyu ‘Waimai Qishou, Kunzai Xitongli’ de Jidian Shengming 关于《外卖骑手,困在系统里》的几点声明 [Statements on “Delivery Riders, Stuck in the System”]. Renwu, November 3. Available online: https://weibo.com/ttarticle/x/m/show/id/2309405096942299643909 (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- Ferrari, Rossella. 2025. Performance and Postsocialism in Postmillennial China. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Glissant, Edouard. 1994. Poetics of Relation. Translated by Betsy Wing. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hillenbrand, Margaret. 2023. On the Edge: Feeling Precarious in China. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Hui. 2022. Riders on the Storm: Amplified Platform Precarity and the Impact of COVID-19 on Online Food-delivery Drivers in China. Journal of Contemporary China 31: 351–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamerson, Trevor. 2017. Digital Orientalism: TripAdvisor and online travelers’ tales. In Digital Sociologies. Edited by Jessie Daniels, Karen Gregory and Tressie McMillan Cottom. Bristol: Bristol University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, Youxuan 赖祐萱. 2020. Waimai Qishou, Kunzai Xitongli 外卖骑手,困在系统里 [Delivery Riders, Stuck in the System]. In Renwu. Edited by Shi Jin. September 7, Available online: https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/Mes1RqIOdp48CMw4pXTwXw (accessed on 8 December 2024).

- Li, Jianjun 李建军. 2024. Bianxingji 变形记. [The Metamorphosis]. Directed by Li Jianjun. Performance, CPAA Theatre, Chengdu, 18 September 2024. (Video shared by Li Jianjun in private). [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Hong Yu. 2024. Law and Order: The Political Power and Constraints of Labor Governance in China’s Platform Economy. The China Review 24: 55–77. [Google Scholar]

- Lukács, Georg. 1971. History and Class Consciousness: Studies in Marxist Dialectics. Translated by Rodney Livingstone. Cambridge: The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ping, Sheke Sun. 2024. Yanjiu Fenxiang: Wo Yanjiu Nvqishoou de Zhexienian 研究分享|我研究女骑手的这些年. [Sharing My Research: During the Years I Research Female Delivery Riders]. Xiaohongshu. Available online: https://www.xiaohongshu.com/explore/65a20404000000001000c307?xsec_token=AB0uNSIvhRllnKWio6E6qhMVE_A8FgiK_F4wzeA35xcUA=&xsec_source=pc_user (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- Sun, Ping. 2019. Your order, their labor: An exploration of algorithms and laboring on food delivery platforms in China. Chinese Journal of Communication 12: 309–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Ping 孙萍. 2024. Guodu Laodong: Pingtai Jingji Xia de Waimai Qishou 过渡劳动:平台经济下的外卖骑手 [Transitional Labor: Food-Delivery Workers in the Platform Economy of China]. Shanghai: Huadongshida Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Dan 吴丹. 2023. Zuijin, 30 Duo Wan Ren Qu Anaya Kanxi 最近,30多万人去阿那亚看戏 [Recently, More Than 30,000 People Have Visited Aranya to Watch Theatre]. Diyi Caijing. July 16. Available online: https://www.yicai.com/news/101799495.html (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Wu, Xiaogang. 2019. Inequality and Social Stratification in Postsocialist China. Annual Review of Sociology 45: 363–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, Muliang, and Annie Feng. 2018. Chinese Directors: The New Generation. Critical Stages. Available online: https://www.critical-stages.org/18/chinese-directors-the-new-generation/ (accessed on 11 October 2025).

- Yang, Yuhong. 2019. Danmaku subtitling: An exploratory study of a new grassroots translation practice on Chinese video-sharing websites. Translation Studies 14: 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).