Abstract

This paper uses an empirical analysis of a water conflict in the German state of Brandenburg to explore diverse constructions of vulnerability to water scarcity by local stakeholders. It demonstrates how, in the absence of effective formal institutions, these constructions are getting translated into conflictual resilience strategies practiced by these stakeholders, creating situations in which “your resilience is my vulnerability”. The novel contribution of the paper to resilience research is threefold. Firstly, it illustrates how the vulnerability and resilience of a socio-ecological system—such as small catchment—are socially constructed; that is, how they are not given but rather the product of stakeholders’ perceptions of threats and suitable responses to them. Secondly, the paper emphasizes the role of institutions—both formal and informal—in framing these vulnerability constructions and resilience strategies. Particular attention is paid to the importance of informal ‘rules in use’ emerging in the wake of (formal) ‘institutional voids’ and how they work against collective solutions. Thirdly, by choosing a small-scale, commonplace dispute to study vulnerability and resilience, the paper seeks to redress the imbalance of resilience research (and policy) on dramatic disaster events by revealing the relevance of everyday vulnerabilities, which may be less eye-catching but are far more widespread.

1. Introduction

In recent years resilience has morphed from a term used primarily to describe ecological processes into a boundary concept applied to a gamut of societal phenomena taking an array of disciplinary approaches [1]. It is today used widely, but often without critical reflection of what the term means, how it can be interpreted differently and what impact these diverse meanings can have. For these and further reasons, the concept of resilience has recently become the subject of criticism [2]. Within the field of social-ecological systems (SES) resilience research is today branching out to address the interplay of physical, social, environmental and economic dimensions to vulnerability and resilience [3,4], different forms of resilience—from resistance and bounce-back to adaptation—at different scales [5] and the role of institutions in promoting more resilient SES [6]. Even if relational aspects—i.e., the “resilience of what to what” [7]—have been acknowledged for more than a decade, this SES literature generally lacks an appreciation of how resilience and vulnerability are socially constructed, in the sense that vulnerability is a product of socially constructed risk perceptions and resilience the ability to minimize potential harm in response to these vulnerability constructions. [8,9]. Accordingly, actors can have very divergent perceptions of even common threats and develop, in consequence, conflicting coping strategies. This perspective complements the widespread notion that an entity’s vulnerability is merely a function of one or more negative factors or that resilience is a value-free coping strategy. It asserts, rather, that vulnerability is first and foremost about how threats are perceived by (diverse) actors and resilience about (often competing) constructions of how best to respond to perceived threats.

This paper uses empirical analysis of a water conflict in the German state of Brandenburg to explore diverse constructions of vulnerability to water scarcity by local stakeholders and how these are influencing their respective, competing resilience strategies, such that “your resilience is my vulnerability”. In doing so, the paper focuses on the one hand on the stakeholders’ constructions of vulnerability, shaped by geographical position and the perception of its causes. On the other hand we emphasize the role of institutions—both formal and informal—in providing avenues for responding to vulnerabilities with actor-specific resilience strategies. More specifically, the paper explores how the absence, or inadequacy, of formal institutional arrangements to regulate water shortages, i.e., institutional voids [10], creates openings for diverse subjective vulnerability constructions and self-motivated ‘rules in use’—to the detriment of collective solutions.

The core research question is what the conflict surrounding water scarcity in the Fredersdorf Mill Stream catchment can tell us, in essence, about the role of institutions in constructions of vulnerability and resilience 1. The paper begins by conceptualizing the institutional in the vulnerability and resilience of social-ecological systems (SES). This is done by acknowledging recent advances, but also critiquing some basic assumptions, of resilience research on SES, before introducing helpful, discursive strands of research on institutions. The following, empirical section presents the case of the water conflict along the Fredersdorf Mill Stream. It describes first the institutional context of the conflict, then the diverse constructions of vulnerability by the stakeholders and then the various resilience strategies applied in practice. In the subsequent section we interpret the empirical findings in terms of informal ‘rules in use’ emerging in the institutional void to guide the actions of the stakeholders and how these ‘rules in use’ draw on, and are themselves framed by, context-specific spatial and material conditions. The paper concludes with observations on how a constructivist approach can enrich resilience research on SES—empirically, analytically and conceptually—and how, conversely, research on institutions can enrich constructivist approaches to resilience.

2. Conceptualizing the Institutional in the Vulnerability and Resilience of Social-Ecological Systems

In recent years research on the vulnerability and resilience of social-ecological systems (SES) has made significant advances beyond the simple, linear causalities and essentialist assumptions about restoring environmental functions which underpinned many of the early generation contributions. SES research is branching out today to encompass a wider range of factors and phenomena than previously considered. Three research trends are particularly noteworthy. The first is work which addresses the interplay of physical, social, environmental and economic dimensions, such as the multi- und inter-disciplinary approaches to vulnerability and resilience of the SES literature [1,4,11,12,13]. The value of this research lies in overcoming simplistic notions of one-dimensional causes of vulnerability and considering instead the cumulative effects of overlapping (or conflicting) vulnerabilities and what this means for resilience strategies in response. A second trend is to consider resilience not merely in terms of resistance to change or the capacity to bounce-back to some previous state, but also adaptation to maintain system-specific functions or—more radically—a general state of adaptability of SES in the face of disruption and change [5,14,15,16,17,18]. Resilience, in this latter sense, encompasses potentially radical change to SES if this is deemed necessary to maintain its social-ecological functions. The third research trend is to explore the role of institutions in promoting more resilient SES [5,6,19,20,21,22]. Here, the benefit lies in exploring the rule systems of legal frameworks, organizational structures, cultural norms, etc., which frame responses to vulnerability and the governance mechanisms promoting adaptive action.

From a social science perspective there remain, however, a number of deficits to this research. Firstly, inadequate consideration is given to the social construction of vulnerability and resilience in research on SES in general and on institutions in particular. The well-established scientific approaches to institutions of SES, such as the Institutional Analysis and Development (IAD) framework [23] or the Institutional Dimensions of Global Environmental Change (IDGEC) project [24], take a largely instrumental approach to institutions. The prime interest here lies in (re-)designing institutions to redress what are regarded as factual deficiencies in SES regimes determined by, for instance, spatial misfits between a bioregion and political jurisdictions. The SES literature has, however, paid little attention to the ways in which both the vulnerability of social-ecological systems and their resilience are perceived and given meaning by actors, resulting in often diverse interpretations and responses. A social-constructivist approach, as advanced by Christmann and Ibert [8], which takes vulnerability perceptions and resilience strategies as mutually related components can help identify and explain the deeply political nature of many vulnerability discourses and resilience strategies. This applies in particular to the institutional arrangements regulating SES. Secondly, current research on SES institutions is generally biased in favor of formal institutions and how they can be redesigned to perform better. Much less consideration is given to informal institutions, such as value systems, cultural norms or routine procedures, and how they—in interaction with formal institutions—frame collective action, although occasional references to their importance are made [25]. It follows, thirdly, that there is a lack of research on the relationship between institutions (both formal and informal) and social or political constructions of vulnerability and resilience. This issue lies at the core of our paper. We are interested in exploring the ways in which the vulnerability of a SES, as constructed by stakeholders, translates into institutional arrangements and, conversely, how formal and informal institutions themselves influence these vulnerability constructions and resilience strategies in response.

These gaps in research on SES in general are echoed in the literature on water and water management, the thematic focus of this paper. Water is a common theme of SES research (e.g., [26,27,28]). Studies on the resilience of water as a SES commonly regard resilience as a system attribute (e.g., [29,30]). Following mainstream SES research, resilience here is about: (a) how much disturbance the system can absorb and remain functional; (b) the degree to which it is capable of self-organization; and (c) how far it can build and increase adaptability [11]. Besides resistance against disturbances like floods and droughts, this latter point of adaptive capacity for the SES water has attracted particular attention in recent research, especially in the context of climate change adaptation [31,32,33]. Ways of coping with uncertainties, relating in particular to water availability, have provided an important thematic link between water and resilience research, as reflected in the discursive shift from Integrated River Basin Management (IRBM) to adaptive water management. Furthermore research on the impacts of climate change has generated additional interest in the vulnerability of both water resources and humans to extreme water-related events [4,34,35]. Within the debate on different types of uncertainties, resilience has increasingly been applied as a guiding concept for the development of strategies to cope with long-term environmental changes and uncertainties [36]. Here, too, interest has emerged in questioning the role of institutions in dealing with global, or climate change (cf. [32,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44]). Within this debate the role of institutions in framing adaptive (or resilient) water management under conditions of uncertainty and change has gained in importance. Nevertheless, institutional contexts remain under-researched, as the “missing link” in the study of SES resilience [19].

Significantly, in all these strands of water-related research the process of social construction of vulnerability and resilience is rarely acknowledged [9]. The attributes of water and water management regimes are largely taken as given (a notable exception is Kraisoraphong [45]). Even if the importance of the local and regional context is emphasized and the reduction of resilience is addressed as a challenge to enable a desirable transformation [15], research on the social construction processes of vulnerability and resilience strategies in their institutional context are largely beyond the frame of reference.

If research on the vulnerability and resilience of SES and on the institutions which shape them is generally blind to processes of social and political construction, which conceptual approaches exist that can reorientate research in this direction? Within the broad church of neo-institutionalism two strands of recent research are particularly relevant. The first is Discursive Institutionalism [46,47], also known as Constructivist Institutionalism [48,49]. According to Vivien Schmidt, discursive institutionalism “lends insight into the role of ideas and discourse in politics while providing a more dynamic approach to institutional change than the older three new institutionalisms” ([46], p. 303). In this way it is better equipped than the other approaches of rational choice, sociological and historical institutionalism to explain how institutions emerge and change. This understanding of institutions as products and medium of processes of social and political construction provides conceptual guidance for our paper.

Empirical guidance is drawn from the second strand of institutionalist research, the work by Maarten Hajer on “institutional voids” [10]. His term “institutional void”—it should be emphasized from the start—does not refer to some kind of institution-free zone where formal and/or informal rule systems do not, or have ceased to, exist. It refers instead to situations where “there are no generally accepted rules and norms according to which policy making and politics is [sic] to be conducted” ([10], p. 175). In an institutional void, according to Hajer, “actors not only deliberate to get to favorable solutions for particular problems but while deliberating they also negotiate new institutional rules, develop new norms of appropriate behavior and devise new conceptions of legitimate political intervention” (ibid.). In other words, in an institutional void policy and polity are dependent on the outcome of discursive interactions. These two understandings of institutions provide us with the conceptual and methodological purchase to explore discursive constructions of vulnerability and resilience in practice within an exemplary case which focusses on typical problems of small catchments affected by water shortages.

3. Research Methodology

The research for this paper was mainly conducted between 2009 and 2012 in the context of an interdisciplinary research consortium funded by the German Ministry of Education and Research and entitled “Innovation Network for Adaptations to Climate Change in the Berlin-Brandenburg Region” (INKA BB). On the initiative of the mayors of the five riparian municipalities of the Fredersdorfer Mill Stream catchment (see Section 4 below) one work package within a sub-project on low-water management was designed to explore options for resolving problems of temporary water shortages and the conflict surrounding them. The following paper is based on the social science component of this sub-project.

An initial stakeholder analysis was conducted in 2009 to identify the constellation of actors involved and their various perspectives on the water shortage issue. This comprised primarily a systematic media analysis (newspapers and internet) and face-to-face semi-structured interviews with 18 stakeholders. These included representatives from local authorities, public agencies of water and nature protection, local water boards and local NGOs. The initial findings were validated in a SWOT workshop with selected administrative stakeholders, an excursion with the responsible water board and an initial stakeholder workshop. Subsequently, the empirical base of the stakeholder analysis was continuously refined following participatory observation and documentation of ten stakeholder meetings and annual workshops organized by the research project between 2009 and 2013.

Following the stakeholder analysis an institutional analysis was conducted to explore the ways in which water shortages and their social construction were framed by formal and informal institutional arrangements. This step involved initial text analysis of, in all, 32 relevant laws and documents from European, Federal and state levels covering the fields of water management, nature conservation, spatial planning and climate change adaptation. Explicit references to the prevention and management of low-water situations and water conflicts (e.g., §33 of the Federal Water Law (WHG) on “minimum water flow”) were identified, as well as implicit references (e.g., to maintain and strengthen the functionality and efficiency of waters as an integral part of the ecosystem and to use water with respect to the well-being of the community and to particular interests (§6 (1) No. 1 and 5 WHG [50]). Interpretation of this data revealed that the analysis of the formal institutional framework, and the institutional voids identified (see Section 4 below), were not sufficient to explain the emergence and trajectory of the observed water conflict in the Fredersdorf Mill Stream catchment, requiring additional analysis of informal institutions at play in the region. To this end, local authority reports, minutes and correspondence, especially between the responsible water authorities, the water board and local NGOs, were analyzed and the interview transcripts reappraised for evidence of informal rule systems. Due to the often intangible character of informal institutions [51] we focused our analysis on identifying ‘rules in use’, as applied expressions of the interplay between formal and informal institutions. By combining our conclusions on institutional voids from the formal institutional framework with the empirical data on stakeholders’ own social norms, we identified actor-specific ‘rules in use’ and the vulnerability perceptions and resilience strategies on which they were based. Working hypotheses on these ‘rules in use’ were presented to the research partners, at stakeholder workshops and in academic conferences, resulting in continuously refined versions of the analysis.

From the beginning of the project the authors were highly aware of the challenges of researching this process whilst themselves—as members of the research consortium—being party to the conflict resolution initiative. This required careful and continuous clarification of the dual roles as observer and (indirect) participant in all activities undertaken. Impartiality in dealings with all stakeholders was paramount. We kept our research reports strictly internal and confidential in order to build confidence and avoid provocation. We defined—and explained—our role not as mediators or coordinators, but as observers of a process relying on scientifically tested methods. Our purpose was not to predetermine any future decisions for the catchment but rather to offer explanations for the status quo, encourage a broader perspective on the conflict and to proffer a variety of ways forward for the stakeholders to decide for themselves. Reflecting on the different roles of social scientists in an inter- and transdisciplinary research project of this kind was a core element of our work. It was the topic of a working group formed within the research consortium and of several presentations at national and international research workshops.

4. Institutions, Vulnerabilities and Resilience Strategies in a Water Scarcity Conflict

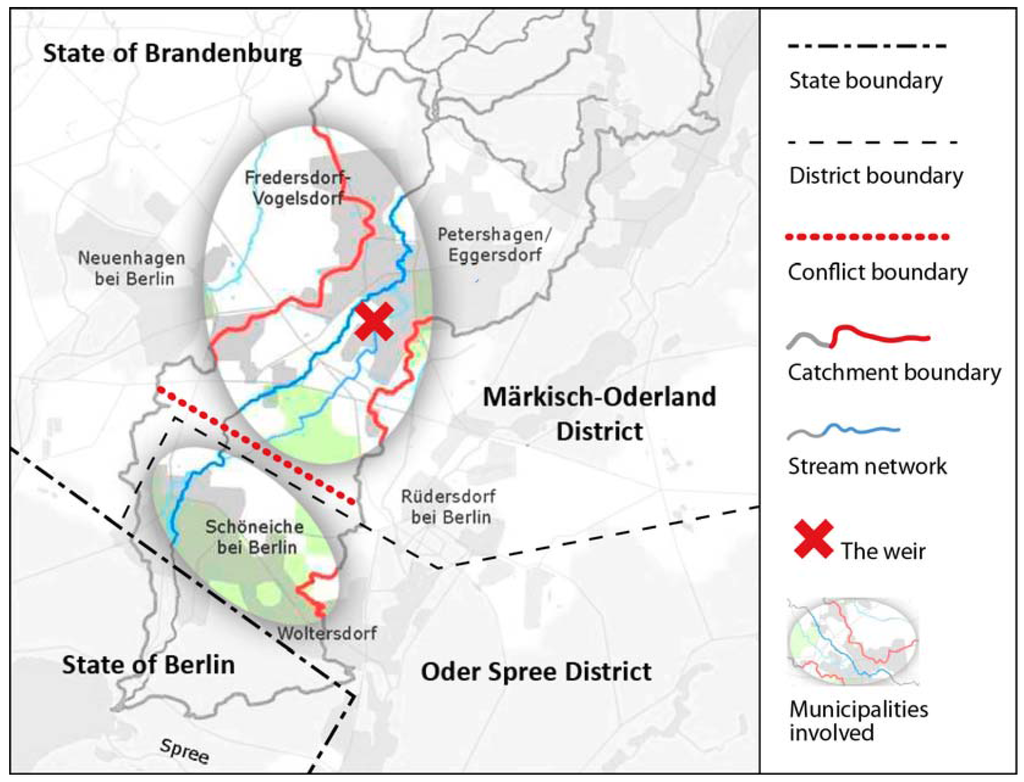

Our empirical research on social constructions of vulnerability and resilience was conducted on the Fredersdorf Mill Stream, a small but interesting watercourse on the outskirts of Berlin (see Figure 1). With a catchment of just 230 km2, flowing from its source in Brandenburg to the Müggel Lake in Berlin, it is in many ways typical of other small river basins in the North-German Plain. The Fredersdorf Mill Stream catchment belongs to the Barnim Plateau, a glacially formed ground moraine landscape. In the upper reaches the stream flows in a glacial melt-water channel (the Gamengrund). After passing two lakes the stream flows into the broad glacial valley termed the Berliner Urstomtal and from there into the Müggel Lake in Berlin, thus draining into the River Spree. Especially in the middle and lower courses the stream passes leaching sections of permeable material. Given its length of only 33 km and the low relief of the catchment the potential to retain water is relatively small [52]. The catchment experiences the sporadic problems of water shortage familiar to others in this dry region with only around 550mm annual precipitation, but in a more extreme form than most and in a way which is expected to become more common in northeast Germany in the wake of climate change [53]. What makes the catchment distinctive is the unusual level of conflict surrounding water uses.

Figure 1.

The location of the Berlin-Brandenburg region in Germany and of the Fredersdorf Mill Stream catchment in the region.

In times of drought the stream suffers from a water scarcity problem. In most dry years the stream dries out in its lower reaches, whilst the upper reaches still have run-off. Historically temporary water shortages have affected the stream since the early 20th century and have occurred several times since 2000 [54]. The precise causes of these low flows are still not clear and are disputed. Explanations vary between the stakeholder groups and include excessive groundwater abstractions from boreholes supplying the water utility in the upper and lower catchment, natural run-off infiltration within the streambed, water retention practices at the lakes, decreasing precipitation due to climate change and water abstractions regulated by a weir.

The main conflict involves stakeholders of two adjacent villages in Brandenburg: Schöneiche bei Berlin (downstream) and Fredersdorf-Vogelsdorf (upstream). The downstream village is dependent on the Mill Stream for water for an artificial riverine channel landscape, which is maintained as a biotope and recreation area by a local environment NGO. The upstream village relies on water from the stream to serve a ditch which supplies water to several biotopes and a lake leased by an anglers’ association since 2004. A dispute over the allocation of the river’s water resources has lasted for several decades. Only since the mid-1990s, however, has it developed into an open conflict, following population growth in both villages, an increase in water uses and shifts in the water regulation regime in the wake of German reunification. After a prolonged period of drought in 2006 the conflict became particularly bitter, prompting the headline of “The Fredersdorf water war” in a Berlin newspaper [55].

Between 2002 and 2007 the upstream water authority did attempt to regulate water flows at the disputed weir which separates the upstream from the downstream communities. However, the stipulations set down in a permit regulating water flows were not implemented or respected in practice and violations were not punished, or even pursued. In the absence of clear and determined regulation by the state the upstream stakeholders regulated the weir themselves according to their own interests. This prompted bitter protests from the downstream community. Since the permit expired in 2007 no new permit for regulating the weir has been issued. Following a short-spelled period of intervention in 2002 the water authorities responsible for the catchment have been reluctant to use their available powers to resolve the conflict.

How, though, did this fairly common dispute between upstream and downstream users in well-regulated Germany become so virulent and persistent in the case of the Fredersdorf Mill Stream? Before we focus on the contrasting vulnerability constructions and resilience strategies of the local stakeholders, we need to set the case in the broader institutional context of water scarcity.

Our institutional analysis (see Section 3 above) revealed that formal institutional frameworks for managing water resources—whether at EU, federal or state level—are all biased towards addressing problems of water quality. Water quantity—at least relating to surface water—is subject to less stringent regulation. The EU Water Framework Directive (WFD)—the flagship regulation for water resources management in Europe—focuses on the ecological quality of surface water. Water quantity issues relating to surface water bodies, in contrast to the good quantity status of groundwater, are mentioned in the Directive only indirectly or with imprecise targets, for instance with regard to conditions consistent with achieving biological quality objectives [56] as the European Commission itself acknowledges today [57]. Up until 2010 the Federal Water Act in Germany made no explicit reference to water scarcity in surface waters, even if the principles of water management in Germany implicitly require adequate management and prevention of extreme low flows [58,59]. The State Water Act of Brandenburg also included no binding requirement to consider low flows in rivers prior to 2011. Although further institutional instruments for coping and preventing anthropogenic water scarcity and water conflicts existed at the federal level (§22 WHG [60]) and the state level in Brandenburg (§77 BbgWG [61]), these instruments were, and still are, not binding and exerted no pressure for intervention by the responsible authorities.

Since 2007, however, in the wake of growing political concern over the impacts of climate change on water availability and in the context of the implementation of the WFD’s Management Plans and the Programs of Measures, adaptations have been made to these institutional arrangements to take greater account of water scarcity problems. These include the EU’s Communication on Water Scarcity and Drought [62] and the EU’s Report on European Water Scarcity and Droughts Policy [57]. In Germany the (non-binding) Guidelines for Sustainable Low Water Management, developed by the German Inter-State Working Group for Water (LAWA) [63], were published and, as a formal institutional reform, a new paragraph on minimum flows was included in the revised Federal Water Act of 2010 (§ 33 WHG [50]) 2. This paragraph permits the storage or abstraction of surface water only when an ecologic minimum flow is guaranteed.

However, being very recent and in many cases non-binding (e.g., the LAWA Guidelines, the EU Communication on Water Scarcity), this institutional turn has, as yet, had little impact on water management and the conflict at the Fredersdorf Mill Stream in practice, with the authorities remaining as reluctant to intervene as before. There is a gap, in other words, between the new formal institutional arrangements to address water scarcity and the persistent informal institutions for dealing with the problem as applied by local and regional stakeholders. This institutional void [10] is, we argue, being filled by stakeholders’ own ‘rules in use’ and is thereby contributing to the conflict. Before we look at these ‘rules in use’ we need to identify the various social constructions of vulnerabilities and related resilience strategies to reduce these vulnerabilities.

The diverse constructions of vulnerability related to low water flows are primarily framed by the different interests in water use. Due to the different water uses, vulnerability means different things to different stakeholder groups. For local anglers it is their fish stock that is vulnerable to water scarcity; for riparian users it is their private gardens that cannot be watered; for environmental groups it is the water-based biotopes along the stream they maintain. The local water utilities have a vested interest in protecting their sources of water supply, the environmental regulator is concerned about the vulnerability of water stocks to pollution, whilst local residents highlight the negative effects on landscape aesthetics and recreational value.

Besides the individual interests in use, the vulnerability perceptions are also shaped by geographical position. Indeed, in the case of the Fredersdorf Mill Stream geographical location often overrides potential synergies between water use interests as a determinant of vulnerability constructions. A clear division of problem perception has emerged between upstream and downstream communities. Thus an informal upstream alliance of the local angling club, the municipality, the local environmental NGO and lake riparians has developed over the last decade, partially sharing a common vulnerability construction around the need to retain water in the upstream community. Illustrative of the dominant logic of geography is the way in which the environmental NGO of the upstream community has recently been infiltrated by local anglers to strengthen the case for retaining water upstream by arguing in the name of nature conservation. This has resulted in members of the anglers’ club demanding, as representatives of the local environmental NGO, more intensive river maintenance within a nature protection zone in order to secure minimum water levels to maintain the fish stock in the lake introduced for angling purposes. Due to administrative borders in the catchment, this geographical divide is also reflected in the perception of the water authorities. The upstream district water authority is largely content with the status quo, which favors the upstream communities. For both the downstream district water authority and state water authority the conflict has a low priority as the catchment is geographically peripheral for the district and so small in scale. Interestingly, different temporal terms of reference also come into play in the competing vulnerability constructions. The upstream community interprets its vulnerability in terms of future extreme events, such as drought conditions and climate change as well as potential institutional changes to the regulation of the disputed weir. For the downstream community, by contrast, it is not the future but the current and past situation—characterized by over-abstraction at the weir, the inactivity of the authorities and their own political weakness—which they see as a making them vulnerable.

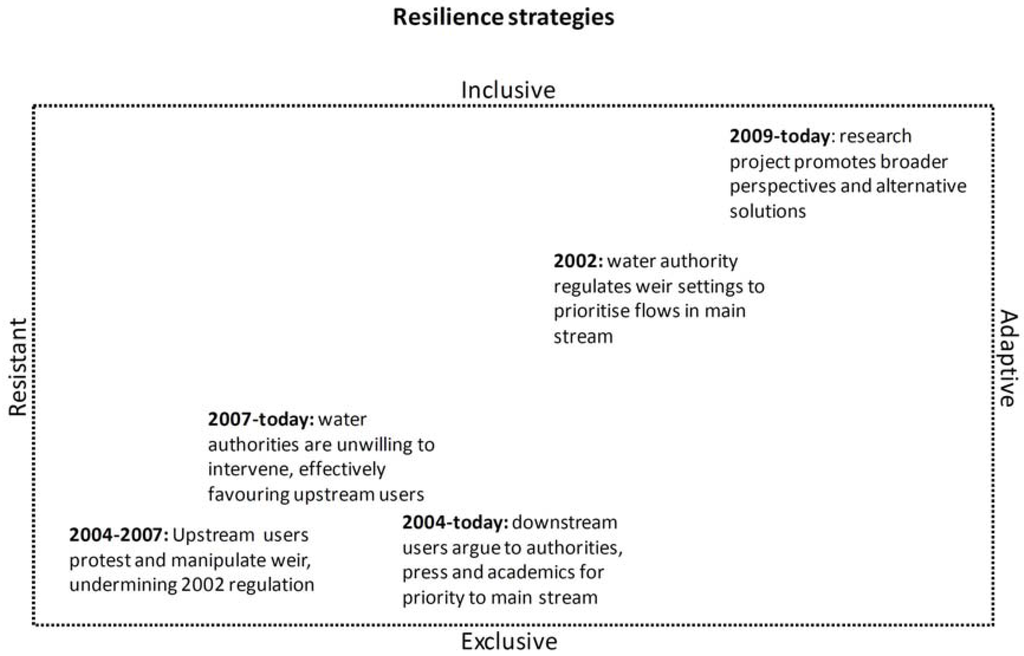

How have these constructions of vulnerability, in the absence of effective regulation, translated into strategies of the stakeholders to reduce their perceived vulnerability in practice? What do these strategies say about the kinds of resilience pursued? Figure 2 presents these rival resilience strategies mapped between two scales of attributes. The horizontal scale represents the type of resilience pursued, on a scale from resistant to adaptive. The vertical one represents the degree of openness of the strategy, ranging from exclusive to inclusive. The first strategy mapped is the decision of the (upstream) water authority in 2002 to regulate the weir settings so as to prioritize flows in the main stream in low-flow phases, and thus accommodating even downstream interests that are not related to the subsidiary ditch which mainly serves the upstream community and its lake. This step marked a form of limited adaptation of the flow regime in recognition of multiple water uses and water-based ecosystems both up- and downstream. However, it was not accompanied by an attempt to change water uses to accommodate potential scarcity. Finally, it failed to be implemented effectively, due primarily to the counter strategy of upstream stakeholders. This second strategy was pursued between 2004 and 2007 and focused on maintaining water supply for upstream water uses by controlling the weir. It found expression in the protests of upstream users (e.g., in local council debates) against the regulation of the weir settings and in their illegal manipulation, for instance by breaking the padlock securing the winch. Significantly, a resident alongside of the ditch acquired the key to regulate the weir without any official control. Since no measures were taken by the authorities to intervene or sanction this behaviour, the regulation of 2002 was thereby effectively undermined. Resilience here relates to the resilience of existing upstream water uses and is characterized by a strategy of bounce-back to the status quo ante. The third action taken was the response by the downstream users. The resilience strategy here is recourse to authority and the broader public. Downstream users from 2004 to today have been making their case for prioritizing the main stream to the water authorities, the municipalities, the press and even academics in order to reveal perceived inequalities and gain official recognition of their own water use rights. The fourth action, prominent from around 2007, is the practice of withdrawal by the district and state water authorities. The aim of this strategy is to minimize the vulnerability of their organization to criticism from all sides of the conflict. It is the resilience of their own organizational integrity that is at stake for the water authorities here, not the resilience of water resources or water uses. Given their perceived lack of influence they are unwilling to intervene, thereby effectively favoring the status quo and the user interests of the upstream community. The fifth action, finally, was an indirect consequence of the downstream stakeholders’ strategy and was initiated by an appeal for help from all the local authorities of the catchment to the research community. The research project within which this paper was written was launched in 2009 to explore alternative technical and organizational solutions and to formulate specific recommendations for resolving the conflict. This strategy is inclusive in that it addresses water resources and uses from across the whole catchment, rather than isolated reaches of the stream, and adaptive in the sense that it advocates the adaptation of current water uses to future climate change impacts. Whether this research project can break the deadlock is highly debatable, however. The period of research (2009–2013) has been accompanied by consecutive years of relatively high rainfall, continuous flows in the whole stream and without acute water shortages—a phenomenon which has weakened the pressure to act and reach agreements on water scarcity. The solutions submitted to the project by the NGOs do not indicate any willingness to broaden their local perspectives and to consider alternatives to their long-standing demands to find ways to cope with phases of water scarcity. Even the equipment set up by the researchers to monitor water flows at the disputed weir has been repeatedly subject to manipulation, just like the weir in the past. Certain stakeholders clearly perceive their position as vulnerable to the findings and options emerging from the research. At the same time the local authorities have proved reluctant to engage in a debate on these options, demonstrating a pattern of behavior which can be termed purposeful ignorance. The research project has provided them with an alibi to remain passive, pending the research results, and then to disengage with the debate when they deem the findings to threaten their own interests. Given this response, the most likely outcome of the research project is that it will alleviate the water scarcity problem to a minimal extent—by publishing a catalogue of recommended options and creating a new retention basin—but will not be able to challenge the predominant perception that “your resilience is my vulnerability”.

Figure 2.

Resilience strategies of different groups of stakeholders.

5. Interpreting the Case: Institutional, Spatial and Material Dimensions to the Resilience Strategies

In this interpretative section we return to the core research question about what frames or shapes vulnerability constructions and resilience strategies. More specifically, we ask how constructions of vulnerability and resilience were related to institutions, space and materiality in the case of the Fredersdorf Mill Stream water conflict. We begin by explaining how—in the institutional void for dealing effectively with water scarcity problems—‘rules in use’ developed by local stakeholders became vehicles for the above resilience strategies and expressions of their particular vulnerability constructions. We then draw out the spatial and material specificities of the case and show how these nurtured and reinforced the contrasting resilience strategies.

5.1. The Emergence of Rules in Use in an Institutional Void

How institutions frame the vulnerability constructions, ‘rules in use’ and resilience strategies of local stakeholders is central to this paper. In contrast to common institutionalist approaches to water management the case studied here is not about how institutions can promote more resilient SES, but rather about what can happen in institutional ‘voids’. We reiterate that ‘institutional voids’ do not mean a situation where institutions do not exist but—in line with Hajer’s [10] subtler definition—one where the institutional arrangements are proving inadequate to regulate a problem at all effectively. In the case of the Fredersdorf Mill Stream this is evident in the imprecise, indirect, incomplete and therefore largely ineffective formal regulation of water scarcity in current laws and directives at EU, federal and state levels. It is also visible in the degree to which existing regulations are not well implemented by the water authorities or not respected by certain stakeholders. The fact that illegal tampering of the weir and its settings are reported to the upstream authority by downstream stakeholders but not sanctioned, or even investigated, by the authority is further indicative of this institutional void. In its wake local stakeholders devise and practice their own ‘rules in use’ according to their own vulnerability constructions, for instance manipulating the weir, complaining about manipulation, purposefully ignoring the conflict and passing the buck to other authorities. An important informal institution framing the construction and legitimation of even illegal rules in use is the water users’ individual sense of justice. Even the social construction of the catchment’s geology, such as the influence of possible leaching areas between the upstream and downstream village, is uncertain and strongly shaped by stakeholders’ perceptions of the just—or unjust—distribution of water resources, which, in turn, give rise to contradictory rules in use.

The second point to make here is that this case study is not about linear processes of institutional regulation of human agency, but rather about complex assemblages of institutions and actors in a specific social-technical-ecological context (cf. [64]). We have observed how formal and informal institutions get socially translated into resilience strategies framed by ‘rules in use’ and that these resilience strategies are often selective and exclusive. Within these strategies the different water users create argumentative certainties in order to ignore unwelcome uncertainties of a complex SES, to justify illegal acts or to undermine collective action based on their own ‘rules in use’. The water authorities, by contrast, use uncertainties to justify their withdrawal. Why the emergent institutional void was filled in this way with asymmetric local ‘rules in use’ and not by greater collaboration to overcome a common problem is a moot point. We argue here that it is fruitful to look beyond mere institutional factors in seeking explanations. In the remainder of this section we illustrate how, in the Fredersdorfer Mill Stream case, spatial and material factors framed the stakeholders’ diverse constructions of water scarcity, its causes and potential solutions.

5.2. The Importance of Spatiality

There are several ways in which spatial aspects are influencing the rules in use within the water conflict studied. Firstly, as we have already noted, spatial identity to either the upstream or downstream community tends to override common sectoral interests—a familiar phenomenon termed “institutionalized localism” [65]. For instance, environmental NGOs in the two communities do not seek common ground around water protection or biodiversity issues, but argue the ecological value of ‘their’ respective local environments. This upstream-downstream divide is complicated by power asymmetries between the two communities. The stakeholders’ viewpoints, practices and alliances are powerfully framed by perceptions of spatially conditioned justice and injustice. Secondly, the conflict is compounded by problems of spatial fit [24] due to the fact that the boundary between the upstream and downstream communities coincides largely with the district boundary (see Figure 3). This means that besides the local municipalities neither of the two district water authorities or their administrative districts is inclined to adopt a catchment-wide perspective on the conflict and thereby incur the wrath of its local electorate, as the upstream district authority experienced when it attempted to regulate the weir in 2002. Thirdly, problems of spatial scale are significant in the sense that the Fredersdorf Mill Stream case is simply “too small to care” for the competent water authorities at the state level. The catchment is only one of 161 small catchments in Brandenburg for which river development concepts are planned as a key instrument to implement the Water Framework Directive. In this process, the Fredersdorf catchment is classified as a low priority, due to its good water quality, and therefore relatively insignificant for the state water authority. The problem of being “too small to care” is the same for the district authority downstream, for which the affected municipality of Schöneiche represents only one, peripheral municipality of the 38 for which it is responsible. Finally, a spatially broader, catchment-wide perspective is largely absent in the institutional arrangements. Despite the river basin orientation of water protection under the Water Framework Directive, there exist no effective regulations or organizations for managing the whole of the Fredersdorf catchment (see Figure 3). The only organization with a spatial remit for the catchment, the water and soil association, is responsible only for river maintenance and the implementation of technical measures, not for the implementation of integrated or adaptive water management or the allocation of water. Moreover, its remit stops at the border to Berlin and thereby excludes the lowest part of the catchment. Consequently, it too is playing a largely passive role, trying to minimize its vulnerability to criticism from all sides of the conflict.

5.3. The Importance of Materiality

The materiality of water flows, water infrastructures and the catchment’s geology is also influencing the vulnerability constructions and resilience strategies in the conflict. One of the major points of contestation is over how much water is available where and why. The lack of reliable data on water flows, both at different points in the stream and in the groundwater aquifers, and on leaching-rates in the streambed and related lakes, are exacerbating the conflict. This has helped to generate an argumentative deadlock, in which each community uses data uncertainty to construct its own hydro-geological realities and causalities, each justifying its own ‘rules in use’. Thus the downstream stakeholders argue from their perspective of vulnerability that abstractions upstream are the main problem, whilst upstream stakeholders claim the low flow rates in the downstream village are, rather, the result of water leaching in the sandy stream-bed downstream. The district water authorities are reluctant to intervene without reliable data on water flows, whilst the state water authority, due to its current focus on flood prevention, is reluctant to fund more extensive data collection for a scarcity problem in such a small catchment. Here we can observe how the lack of knowledge about the attributes of material artefacts, and therefore the crucial origins of the presence or absence of water in the catchment, is both a product of institutional void (the unwillingness of authorities to intervene) and a medium for diverse resilience strategies.

Figure 3.

The conflict area and boundaries in the lower catchment.

A second example of the importance of material agency is the role of the weir as a key factor in the conflict. The weir is significant because it determines how much water is allowed to pass into the main stream (i.e., downstream) and how much is diverted to a ditch, the Zehnbuschgraben, which serves a lake located in the upstream village (see Figure 3). It is thus the principal physical regulator of water flows between the upstream and downstream communities. Significantly, the technical design of the weir was altered in the mid-1990s by the local water board, with the permission of the local water authority, to meet various upstream user interests, including better ecological passability in anticipation of the WFD. Formerly it had been operated as an overflow weir, only allowing water to enter the ditch (and the upstream lake) when the water level was higher than the weir. The technical redesign created, by contrast, an underflow baffle ensuring water flow to the ditch even at times of low water levels. The settings of this underflow baffle are, significantly, not visible to observers, adding to the lack of transparency in regulating the water flows. With this new weir the benefits for the upstream community have, therefore, become materialized in infrastructure and thus more robust. Through its physical significance in directing water flows it has become central to the contrasting vulnerability constructions and the conflicting resilience strategies—at the expense of broader perspectives addressing the whole catchment.

6. Final Remarks

What lessons can we learn from this case on how constructivist and (discursive) institutionalist perspectives on vulnerability and resilience can enrich one another? If we look first at what a constructivist approach can bring to resilience research on SES, we can observe that, empirically, it can raise our understanding of how the material world—in our case, water, fish, the weir, the riverine landscape—is perceived and relationally linked in different ways, and to different ends. The vulnerability of water resources in the Fredersdorf Mill Stream is not simply a function of low precipitation, excessive abstraction practices, the unfavorable geology of the catchment, or a combination of any other physical factors. It is rather a product of social perception by diverse actors, resulting in the enrolment of components in particular constructions of vulnerability. Analytically, the constructivist approach can help identify divergent resilience strategies, addressing different components of a SES with different implications, such that—in this case—“your resilience is my vulnerability”. The resilience strategies of stakeholders along the Fredersdorfer Mill Stream are powerfully informed by their own problem perceptions and vulnerability constructions, resulting in highly varied responses to the common problem, which focus on the distribution of limited local water resources and demonstrate only a very limited willingness to negotiate between these competing resilience strategies. Conceptually, social construction provides a useful link between institution theory and discourse theory. The nascent field of discursive, or constructivist, institutionalism provides a valuable point of entry for advancing this exchange between the two bodies of scholarly debate.

Conversely, we have illustrated with the Fredersdorf Mill Stream case how research on institutions can contribute to emergent constructivist approaches to resilience. Institutions—whether formal or informal—are both product and medium of social constructions. That is, they are not only subject to the meanings given to them by actors; they can also be instrumental in guiding social constructions of vulnerability and resilience, for instance by generating a sense of powerlessness or injustice in the face of existing institutional arrangements. Viewing institutions, both formal and informal, as manifestations of power provides a further advantage for constructivist approaches. The case investigated illustrates well that the various constructions of vulnerability do not simply co-exist in some notional equilibrium, but are highly asymmetrical in terms of the power and rivalry they express. Here, the spatial conditions and material objects proved highly important in reinforcing these political asymmetries between the upstream and downstream communities. Conceptually, research on institutions offers the potential to sensitize constructivist approaches to the inherently political and instrumental nature of regulation, governance and resilience. Here, it is not sufficient to restrict analysis to formal—i.e., codified—institutions alone, but to encompass the less visible, but equally influential informal institutions that shaped the ‘rules in use’ developed by the stakeholders in our case study to meet the ‘institutional void’ emerging from a combination of non-binding formal regulations and authorities unwilling to implement them.

Finally, we have sought to demonstrate the value of addressing the ordinary and the mundane in research on vulnerability and resilience [66]. The Fredersdorf Mill Stream case is not about a high-profile disaster, nor does it have direct repercussions on other neighboring catchments. Indeed, its public invisibility is part of the reason why the conflict has proved so persistent. What makes the case so significant is, rather, that it is typical of a multiplicity of disputes over water allocations that are very widespread but too small-scale to attract the attention or to galvanize the resolve needed to find solutions. Here lies a promising field of future research on the vulnerability and resilience of SES in general, and water regimes in particular.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their thanks to the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research for funding the research project on which this paper is based, as well as to the guest editors of the special issue for their thoughtful comments to the initial presentation. We are very grateful to the two anonymous reviewers for improving the stringency and coherence of the paper. We would like to take this opportunity to thank the stakeholders of the Fredersdorf catchment for their openness in the interviews.

Author Contributions

Frank Sondershaus introduced the constructivist resilience perspective to the paper, was responsible for the literature review on resilience within the SES and water literature (in Section 2), contributed the research methodology (Section 3), conducted the empirical research and wrote most of Section 4. Timothy Moss devised the paper structure, contributed the introduction (Section 1), was responsible for the literature review on institutions and resilience (in Section 2) and wrote the final remarks (Section 6). The interpretation of the case (Section 5) was written by both authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Fridolin S. Brand, and Kurt Jax. “Focusing the Meaning(s) of Resilience: Resilience as a Descriptive Concept and a Boundary Object.” Ecology and Society 12 (2007): 23. http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol12/iss1/art23/. [Google Scholar]

- Simin Davoudi. “A Bridging Concept or a Dead End? ” Planning Theory & Practice 13 (2012): 299–308. [Google Scholar]

- Jörn Birkmann. “Globaler Umweltwandel, Naturgefahren, Vulnerabilität und Katastrophenresilienz: Notwendigkeit der Perspektivenerweiterung in der Raumplanung.” Raumforschung und Raumordnung 66 (2008): 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jörn Birkmann, Claudia Bach, and Maike Vollmer. “Tools for Resilience Building and Adaptive Spatial Governance.” Raumforschung und Raumordnung 70 (2012): 293–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John M. Anderies, Marco A. Janssen, and Elinor Ostrom. “A Framework to Analyze the Robustness of Social-ecological Systems from an Institutional Perspective.” Ecology and Society 9 (2004): 18. http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol9/iss1/art18/. [Google Scholar]

- Marco A. Janssen, and Elinor Ostrom. “Resilience, vulnerability, and adaptation: A cross-cutting theme of the International Human Dimensions Programme on Global Environmental Change.” Global Environmental Change 16 (2006): 237–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steve Carpenter, Brian Walker, John M. Anderies, and Nick Abel. “From Metaphor to Measurement: Resilience of What to What? ” Ecosystems 4 (2001): 765–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriela B. Christmann, and Oliver Ibert. “Vulnerability and Resilience in a Socio-Spatial Perspective.” Raumforschung und Raumordnung 70 (2012): 259–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriela Christmann, Oliver Ibert, Heiderose Kilper, Timothy Moss, Karsten Balgar, Frank Hüesker, Manfred Kühn, Kai Pflanz, Tobias Schmidt, Hanna Sommer, and et al. “Vulnerability and Resilience from a Socio-Spatial Perspective, towards a Theoretical Framework.” IRS Working Paper 45, Erkner, Leibniz Institute for Regional Development and Structural Planning; 2012, www.irs-net.de/download/wp_vulnerability.pdf.

- Maarten Hajer. “Policy without polity? Policy analysis and the institutional void.” Policy Science 36 (2003): 175–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carl Folke. “Resilience: The emergence of a perspective for social-ecological systems analyses.” Global Environmental Change 16 (2006): 253–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- W. Neil Adger. “Social and ecological resilience: are they related? ” Progress in Human Geography 24 (2000): 347–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiona Miller, Henny Osbahr, Emily Boyd, Frank Thomalla, Sukaina Bharwani, Gina Ziervogel, Brian Walker, Jörn Birkmann, Sander van der Leeuw, Johan Rockström, Jochen Hinkel, and et al. “Resilience and Vulnerability: Complementary or Conflicting Concepts? ” Ecology and Society 15 (2010): 11. http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol15/iss3/art11/. [Google Scholar]

- Carl Folke, Steve Carpenter, Elmqvist Thomas, Lance H. Gunderson, Crawford S. Holling, and Brian Walker. “Resilience and Sustainable Development: Building Adaptive Capacity in a World of Transformation.” Ambio 31 (2002): 437–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brian Walker, Crawford S. Holling, Stephen Carpenter, and Ann Kinzig. “Resilience, Adaptability and Transformability in Social–ecological Systems.” Ecology and Society 9 (2004): 5. http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol9/iss2/art5/. [Google Scholar]

- Jeroen Aerts, Wouter Botzen, Anne Veen, Joerg Krywkow, and Saskia Werners. “Dealing with Uncertainty in Flood Management Through Diversification.” Ecology and Society 13 (2008): 41. http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol13/iss1/art41/. [Google Scholar]

- Hallie Eakin, Emma L. Tompkins, Donald R. Nelson, and John M. Anderies. “Hidden costs and disperate uncertainties: Trade-offs in approaches to climate policy.” In Adapting to Climate Change: Thresholds, Values, Governance. Edited by Neil W. Adger, Irene Lorenzoni and Karen L. O’Brien. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2009, pp. 212–26. [Google Scholar]

- Carl Folke, Stephen R. Carpenter, Brian W. Marten, Terry C. Scheffer, and Johan Rockström. “Resilience Thinking: Integrating Resilience, Adaptability and Transformability.” Ecology and Society 15 (2010): 20. http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol15/iss4/art20/. [Google Scholar]

- Victor Galaz. “Social-ecological Resilience and Social Conflict: Institutions and Strategic Adaptation in Swedish Water Management.” Ambio 34 (2005): 567–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oran R. Young. “Institutional dynamics: Resilience, vulnerability and adaptation in environmental and resource regimes.” Global Environmental Change 20 (2009): 378–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elke Herrfahrdt-Pähle, and Claudia Pahl-Wostl. “Continuity and Change in Social-Ecological Systems: The Role of Institutional Resilience.” Ecology and Society 17 (2012): 8. http://dx.doi.org/10.5751/ES-04565-170208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John Handmer, and Strephen Dovers. “A Typology of Resilience: Rethinking Institutions for Sustainable Development (1996).” In The Earthscan Reader on Adaptation to Climate Change. Edited by Emma L.F. Schipper and Ian Burton. London: Earthscan, 2008, pp. 187–212. [Google Scholar]

- Elinor Ostrom. “Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action.” Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Oran R. Young. The Institutional Dimensions of Environmental Change: Fit, Interplay, and Scale. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Lance H. Gunderson, Ann P. Kinzig, Allyson E. Quinlan, Brian Walker, Georgina Cundhill, Colin Beier, Beatrice Crona, and Örjan Boden. “Assessing Resilience in Social-Ecological Systems: Workbook for Practitioners.” Version 2.0. https://portals.iucn.org/2012forum/sites/2012forum/files/resilienceassessment2.pdf.

- Crawford S. Holling, Lance H. Gunderson, and D. Ludwig. “In Search of a Theory of Adaptive Change.” In Panarchy: Understanding Transformations in Human and Natural Systems. Edited by Lance H. Gunderson and Crawford S. Holling. Washington, DC: Island Press, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Lance H. Gunderson, Steve R. Carpenter, and Garry P. Olsson. “Water RATs (Resilience, Adaptability, and Transformability) in Lake and Wetland Social-Ecological Systems.” Ecology and Society 11 (2006): 16. http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol11/iss1/art16/. [Google Scholar]

- Oran R. Young, Frans Berkhout, Gilberto C. Gallopin, Marco A. Janssen, Elinor Ostrom, and Sander van der Leeuw. “The globalization of socio-ecological systems: An agenda for scientific research.” Global Environmental Change 16 (2006): 304–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruth Langridge, Juliet Christian-Smith, and Kathleen A. Lohse. “Access and Resilience: Analyzing the Construction of Social Resilience to the Threat of Water Scarcity.” Ecology and Society 11 (2006): 18. http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol11/iss2/art18/. [Google Scholar]

- Aleix Serrat-Capdevila, Anne Browning-Aiken, Kevin Lansey, Tim Finan, and Juan B. Valdés. “Increasing Social-Ecological Resilience by Placing Science at the Decision Table: The Role of the San Pedro Basin (Arizona) Decision-Support System Model.” Ecology and Society 14 (2009): 37. http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol14/iss1/art37/. [Google Scholar]

- Maja Schlüter, and Claudia Pahl-Wostl. “Mechanisms of Resilience in Common-pool Resource Management Systems: An Agent-based Model of Water Use in a River Basin.” Ecology and Society 12 (2007): 4. http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol12/iss2/art4/. [Google Scholar]

- Dave Huitema, Erik Mostert, Wouter Egas, Sabine Moellenkamp, Claudia Pahl-Wostl, and Resul Yalcin. “Adaptive Water Governance: Assessing the Institutional Prescriptions of Adaptive (Co-) Management from a Governance Perspective and Defining a Research Agenda.” Ecology and Society 14 (2009): 26. http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol14/iss1/art26/. [Google Scholar]

- Jaroslav Mysiak, Hans J. Henrikson, Caroline Sullivan, John Bromley, and Claudia Pahl-Wostl, eds. The Adaptive Water Resource Management Handbook. London: Earthscan, 2009.

- Eelco van Beek. “Managing water under current climate variability.” In Climate Change Adaptation in the Water Sector. Edited by Fulco Ludwig, Pavel Kabat, Henk van Schaik and Michael van der Valk. London: Earthscan, 2009, pp. 51–79. [Google Scholar]

- Rebecca Whittle, William Medd, Hugh Deeming, Elham Kashefi, Margaret Mort, Claire Twigger-Ross, Gordon Walker, and Nigel Watson. “After the rain—Learning the lessons from flood recovery in hull.” Final project report for ‘flood, vulnerability and urban resilience: A real-time study of local recovery following the floods of June 2007 in Hull’; UK: Lancaster University, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Pavel Kabat, Ronald Schulze, Molly E. Hellmuth, and Jeroen A. Veraart. Coping with Impacts of Climate Variability and Climate Change in Water Management: A Scoping Paper. Wageningen: Wageningen International Secretariat of the Dialogue on Water and Climate, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Suraje Dessai, and Jeroen van der Sluijs. Uncertainty and Climate Change Adaptation—A Scoping Study. Utrecht, Netherlands: Copernicus Institute for Sustainable Development and Innovation, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Jeroen Aerts, and Peter Droogers. “Adapting to Climate Change in the Water Sector.” In Climate Change Adaptation in the Water Sector. Edited by Fulco Ludwig, Pavel Kabat, Henk van Schaik and Michael van der Valk. London: Earthscan, 2009, pp. 87–108. [Google Scholar]

- Arun Agrawal, and Nicolas Perrin. “Climate Adaptation, local institutions and rural livelihoods.” In Adapting to Climate Change: Thresholds, Values, Governance. Edited by Neil W. Adger, Irene Lorenzoni and Karen L. O’Brien. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2009, pp. 350–67. [Google Scholar]

- Sabine Möllenkamp, and Britta Kastens. “Institutional Adaptation to Climate Change: Current Status and Future Strategies in the Elbe Basin, Germany.” In Climate Change Adaptation in the Water Sector. Edited by Fulco Ludwig, Pavel Kabat, Henk van Schaik and Michael van der Valk. London: Earthscan, 2009, pp. 227–48. [Google Scholar]

- Håkor T. Inderberg, and Per O. Eikeland. “Limits to adaptation: Analysing institutional constraints.” In Adapting to Climate Change: Thresholds, Values, Governance. Edited by Neil W. Adger, Irene Lorenzoni and Karen L. O’Brien. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2009, pp. 433–48. [Google Scholar]

- Lauren S. Urgenson, Keala R. Hagmann, Amanda C. Henck, Stevan Harrell, Thomas M. Hinckley, Sara J. Shepler, Barbara L. Grub, and Philip M. Chi. “Social-ecological Resilience of a Nuosu Community-linked Watershed, Southwest Sichuan, China.” Ecology and Society 15 (2010): 2. http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol15/iss4/art2/. [Google Scholar]

- Barbara A. Cosens, and Mark K. Williams. “Resilience and Water Governance: Adaptive Governance in the Columbia River Basin.” Ecology and Society 17 (2012): 3. http://dx.doi.org/10.5751/ES-04986-170403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmut Fünfgeld, and Darryn McEvoy. “Resilience as a Useful Concept for Climate Change Adaptation? ” Planning Theory & Practice 13 (2012): 324–28. [Google Scholar]

- Keokam Kraisoraphong. “Water Regime Resilience and Community Rights to Ressource Access in the Face of Climate Change.” In Human Security and Climate Change in Southeast Asia. Managing Risk and Resilience. Edited by Lorraine Elliot and Caballero-Anthony. Abingdon, Oxon, UK: Routledge, 2013, pp. 62–80. [Google Scholar]

- Vivien A. Schmidt. “Discursive Institutionalism: The Explanatory Power of Ideas and Discourse.” Annual Review of Political Science 11 (2008): 303–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivien A. Schmidt. “Taking ideas and discourse seriously: Explaining change through discursive institutionalism as the fourth ‘new institutionalism’.” European Political Science Review 2 (2010): 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arild Vatn. Institutions and the Environment. Northampton, MA; Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Colin Hay. “Constructivist institutionalism.” In Oxford Handbook of Political Institutions. Edited by Sarah Binder, Roderick A.W. Rodes and Bert A. Rockman. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2006, pp. 56–74. [Google Scholar]

- Water Act of 31 July 2009 (Bundesgesetzblatt I, p. 2585), most recently revised in Article 2 of the Act of 7 August 2013 (Bundesgesetzblatt I, p. 734). www.gesetze-im-internet.de/bundesrecht/whg_2009/gesamt.pdf.

- Gretchen Helmke, and Steven Levitsky. “Informal Institutions and Comparative Politics: A Research Agenda.” Perspectives on Politics 2 (2004): 725–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mike Ramelow, Stefan Kaden, Christoph Merz, Ralf Dannowski, Timothy Moss, and Frank Sondershaus. “Maßnahmen und Methoden für ein nachhaltiges Wassermanagement zur Stabilisierung des Wasserhaushaltes kleiner Einzugsgebiete vor dem Hintergrund des Klimawandels am Beispiel des Fredersdorfer Mühlenfließes (Brandenburg).” In Aktuelle Probleme im Wasserhaushalt von Nordostdeutschland: Trends, Ursachen, Lösungen. Scientific Technical Report 10/10; Edited by Knut Kaiser, Judy Libra, Bruno Merz, Oliver Bens and Reinhard F. Hüttl. Potsdam: German Research Center for Geosciences GFZ, 2010, pp. 185–91. [Google Scholar]

- Die Bundesregierung. “Aktionsplan Anpassung der Deutschen Anpassungsstrategie an den Klimawandel.” Passed by Federal Cabinet on 31 August 2011.

- Marc Hermel. “Dokumentation zur Geschichte des Fredersdorfer Mühlenfließes unter besonderer Berücksichtigung seines Wasserhaushaltes.” Berlin: Umweltamt Köpenick, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Richard Rother. “Der Fredersdorfer Wasserkrieg.” Tageszeitung TAZ. 20 April 2007. http://www.taz.de/1/archiv/archiv/?dig=2007/04/20/a0223.

- European Commission. “Water Framework Directive.” Directive 2000/60/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 October 2000 establishing a framework for Community action in the field of water policy.

- European Commission. “Report on the Review of the European Water Scarcity and Droughts Policy.” http://ec.europa.eu/environment/water/quantity/pdf/COM-2012-672final-EN.pdf.

- Andreas Vetter, Ludger Gailing, Frank Sondershaus, Nadine Lechner, and Christian Besendörfer. “Flusslandschaften: Wechselbeziehungen zwischen regionaler Kulturlandschaftsgestaltung, vorbeugendem Hochwasserschutz und Niedrigwasservorsorge.” Berlin: BMVBS, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Andreas Vetter, and Frank Sondershaus. “River Landscapes—Reference Areas for Regionally Specific Adaptation Strategies to Climate Change.” German Annual of Spatial Research and Policy 2010 (2011): 137–42. [Google Scholar]

- Water Act in the version dated 19 August 2002 (Bundesgesetzblatt I, p. 3245), most recently revised in Article 2 of the Act of 10 May 2007 (Bundesgesetzblatt I, p. 666).

- State Water Law of the State of Brandenburg in the version dated 08 December 2004.

- European Commission. “Addressing the challenge of water scarcity and droughts in the European Union.” In Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council. Brussels: European Commission, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bund/Länder Arbeitsgemeinschaft Wasser. Leitlinien für ein nachhaltiges Niedrigwassermanagement. Berlin, Kulturbuch-Verlag: Mainz, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Frances Cleaver. “Reinventing Institutions: Bricolage and the Social Embeddedness of Natural Resource Management.” The European Journal of Development Research 14 (2002): 11–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jörg Knieling, Dietrich Fürst, and Rainer Danielzyk. “Warum «kooperative Regionalplanung» leicht zu fordern, aber schwer zu praktizieren ist.” disP—The Planning Review 37 (2001): 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ash Amin. “Surviving the turbulent future.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 31 (2013): 140–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 1The paper is based on research conducted within the sub-project “Methods and instruments for the sustainable management of water in a small catchment in the context of climate change” funded by the German Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) as part of the interdisciplinary project “Innovation networks for adaptation to climate change in Berlin-Brandenburg region” (INKA-BB).

- 2Since 2010 §33 of the revised Federal Water Act explicitly prohibits storage or abstraction of water if low flow threatens to undermine the legally binding ecological requirements for a watercourse.

© 2014 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).