Abstract

Background: Dialogic Feminist Gatherings (DFGs) fostered gender violence prevention among adolescents and young women in diverse educational settings. However, little was known about their impact on adult and older women without higher education, particularly regarding their contributions to broader social change through family and community relationships. This study addressed that gap by analyzing a DFG held in an adult education school in Barcelona with women from diverse backgrounds, as part of the R + D + i ALL WOMEN research project, aligned with Sustainable Development Goal 5. Methods: Using a qualitative case study with communicative methodology, the research drew on communicative observations, life stories, and a focus group. Results: Findings revealed that DFGs empowered participants individually and had a ripple effect in their communities. Through intergenerational dialogues with children, grandchildren, nieces, and nephews, participants began to challenge and transform socialization patterns linked to gender violence risk factors. Conclusions: The study highlights the transformative potential of DFGs beyond formal education. It underscores the value of integrating dialogic and community-based approaches into adult education to promote gender equality and prevent violence across generations.

1. Introduction

Gender violence, also referred to as gender-based violence, encompasses any act of violence or abuse directed at women or individuals based on their gender, resulting in physical, sexual, psychological, or economic harm (World Health Organization 2021). Globally, gender violence remains a widespread and persistent problem. According to estimates from the World Health Organization (2021), about one in three women worldwide has experienced physical and/or sexual violence by an intimate partner, or sexual violence by someone else, at some point in their lives. The effects of gender violence are serious and complex, impacting survivors’ physical and mental health, social connections, economic security, and overall quality of life (United Nations General Assembly 2022). Beyond the harm to individuals, gender violence also weakened social cohesion and created barriers to achieving gender equality and sustainable development.

According to the 2019 Survey on Violence Against Women conducted by the Ministry of Equality, 57.3% of women aged 16 and over living in Spain had experienced some form of violence during their lives simply because they are women. This figure included various types of violence: physical, sexual, and psychological violence committed by current or former partners (32.4%), physical violence outside of intimate relationships (13.4%), sexual violence outside of intimate relationships (6.5%), as well as sexual harassment (40.4%) and stalking or repeated harassment (15.2%). Young women were especially affected, with 71.2% of those aged 16 to 24 reporting that they had experienced at least one form of violence, highlighting the persistence and pervasiveness of gender-based violence across different life stages and social contexts (Ministry of Equality 2020). Spain implemented the pioneering Organic Law 1/2004 on Integrated Protection Measures against Gender Violence, which introduced specialized courts, comprehensive victim support services, and educational initiatives aimed at prevention. This legal framework positioned Spain as a reference in Europe for its institutional commitment to combating gender violence. However, despite these advances, prevalence data indicated that significant challenges remained, and further efforts were needed to ensure effective prevention and protection for all women.

From a dual interdisciplinary social perspective that took into account both the structures of the system and the actions of individuals, gender violence is not only rooted in social and cultural structures that sustained unequal power relations, but also was reproduced or overcome through everyday socialization processes and interpersonal interactions in families, schools, peer groups, and media (Connell 2012; West and Zimmerman 1987). Gender socialization involves the transmission of norms and expectations about masculinity and femininity, which often reinforced inequality and normalized violence (Connell and Messerschmidt 2005; Jewkes et al. 2015). Both everyday interactions and institutional frameworks contribute to either reproducing or transforming gender violence, highlighting the importance of addressing relational dynamics and structural conditions to effectively understand and prevent this phenomenon (Connell 2012; Flood and Pease 2009).

This article built on these perspectives by examining how everyday socialization processes could contribute to the prevention of gender violence. It presented a case study focused on Dialogic Feminist Gatherings (DFGs), exploring their impact on women’s empowerment and community transformation among participants who had historically faced educational exclusion.

2. Evidence-Based Interventions for Gender Violence Prevention: Dialogues and Community Action

Feminist theory has long informed social work and community practices, yet its influence has often been uneven and contested, particularly in relation to women without academic backgrounds. Drawing on a wide-ranging analysis of feminist movements, Fawcett (2022) highlighted how different strands of feminism have shaped social work in complex and sometimes contradictory ways. She critiqued the exclusion of marginalized women from dominant feminist narratives and called for inclusive and context-sensitive approaches that recognized their lived experiences and contributions to social transformation. These insights were particularly relevant in the field of gender violence prevention, where a wide range of interventions have been developed across diverse contexts. These included legal reforms, policy initiatives (Marphatia and Moussié 2013), school and community programs (Pham 2015), and public awareness campaigns (Maber 2016). Although diverse professionals focused on the issue of gender violence, many emphasized the need for effective solutions aimed at its prevention (Matos et al. 2025). Recent reviews confirmed that multi-level interventions, those combining education, community mobilization, and support services, were among the most effective (Ullman et al. 2025; Gebo and Franklin 2023). Educational strategies that promoted critical reflection, egalitarian dialogue, and collective action have shown strong potential to transform attitudes and behaviors (Kumari et al. 2025; United Nations Women 2023).

In this line, an important contribution in recent years is the identification of the coercive dominant discourse, promoted by the most patriarchal and sexist sectors of society. This discourse imposed a dominant socialization pattern that linked sexual and affective attraction to violent behaviors, while portraying egalitarian and non-violent attitudes as less desirable (Puigvert et al. 2019). As a result, it contributed to the normalization of violent relationships. Scientific research has demonstrated that educational interventions based on evidence with proven social impact in the prevention of gender violence, especially those that explicitly addressed and challenged the coercive dominant discourse, help to overcome these patterns (Puigvert 2016).

Another relevant strategy in the prevention of gender violence was bystander intervention, which means that people who witness situations of violence do not remain passive, but instead took an active stance as upstanders (Banyard et al. 2025). Upstanders supported the victim, helped them seek assistance, and broke the silence that allowed violence to continue (American Psychological Association 2022; Park and Kim 2023). Scientific evidence shows that bystander intervention programs can increase people’s confidence and willingness to act, especially when they promoted empathy, addressed contextual factors, and provided practical tools for safe and supportive action (Mainwaring et al. 2023).

However, for this active positioning to be effective, and for bystanders not to be afraid to support the victim, it was essential that institutions and communities also implemented specific measures to prevent and address isolating gender violence, defined as any type of violence directed at those who support victims of gender violence, with the aim of leaving the victim isolated, including retaliation, defamation, threats, workplace or social harassment, which has serious consequences for the physical and mental health of those who experienced it (Aubert and Flecha 2021).

Despite these advances, challenges remained in reaching women without formal education, who were often excluded from mainstream prevention efforts. Community-based programs that fostered inclusive participation have shown promise in addressing this gap (Ullman et al. 2025).

In this context, DFGs emerged as a successful educational action aimed at preventing gender violence (Gómez 2015; Valls 2014). DFGs were grounded in egalitarian dialogue, where women of diverse ages and backgrounds engaged in critical reflection on scientific evidence of social impact that addressed gender violence and its victimization. These gatherings were based on the collective reading and analysis of such evidence, particularly that which focused on the over-coming coercive dominant discourse, with the aim of transforming beliefs and practices that perpetuated violence (Puigvert 2016).

Some studies have demonstrated the positive impact of DFGs on adolescents and young women in diverse educational settings. For instance, in secondary schools, participants identified and questioned the coercive dominant discourse, which associated attraction with developing tools to recognize and reject violent relationships (Ruiz-Eugenio et al. 2020). In special education schools, DFGs created safe and supportive environments that protected girls with disabilities from violent relationships (Rodrigues de Mello et al. 2021). In university settings, a decrease was observed in the perceived attractiveness of men showing attitudes associated with risk factors for perpetrating violence, following participation in DFGs (Puigvert 2016).

Despite these advances, a knowledge gap remains regarding the impact of DFGs on adult and older women without formal academic qualifications, an of-ten-overlooked group in both feminist public discourse and in the co-creation of educational actions for gender violence prevention (Oliver et al. 2009). Although DFGs emerged within the tradition of dialogic popular education, particularly among non-academic women, concrete evidence of their transformative impact on this specific population is still absent from scientific literature. Existing studies have documented the effects of other dialogic educational spaces, but not specifically of DFGs (Beck-Gernsheim et al. 2003; Valls 2014). This article addressed this gap through a qualitative case study conducted at an adult education school located in a working-class neighbourhood in the city of Barcelona, where DFGs were first created and developed in the late 1970s. Framed within the R + D + i ALL WOMEN research project, this case study addressed the following research question: What impact do DFGs have on participating women, their families, and their community, particularly in terms of preventing gender violence? The study aimed to contribute to the advancement of United Nations Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 5: “Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls,” specifically Target 5.2: “Eliminate all forms of violence against all women and girls”.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Design

This article presented one of the qualitative case studies developed within the framework of the R + D + i research project ALL WOMEN “The empowerment of all women through adult education for a sustainable development” (PID2020-113137RA-I00), funded by the State Research Agency of the Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities of Spain, conducted over four academic years (2021–2025). The overall aim of R + D + i ALL WOMEN research project, was to identify actions in adult learning, both in formal and non-formal education, that contributed to the empowerment of women in vulnerable situations, in alignment with the UN SDG 5 (United Nations 2015).

The case selection criteria included: (1) demonstrable impact on at least one of the targets of SDG 5 (United Nations 2015); (2) involvement in an adult learning or educational action in either formal or non-formal settings; and (3) active participation of women in vulnerable situations, in this case, being women without basic academic qualifications.

The study was embedded in an adult education school in Barcelona with a long-standing tradition of dialogic learning and democratic participation. This context provided a unique opportunity to examine the impact of DFGs among women without higher educational qualifications, thereby aligning the research design with the broader aims of the project. The long-term collaboration of the research team with the school, extending over three decades, further reinforced the trust and continuity necessary for the communicative approach.

The case study was conducted using communicative methodology, which emphasized egalitarian dialogue and the co-creation of knowledge between researchers and participants (Roca et al. 2022). Data collection involved communicative life stories, a communicative focus group, and communicative observations. Fieldwork aimed to gather evidence of the social impact of DFGs on participating women, their families, and their communities, with particular attention to the preventive socialization of gender violence. Prior to participation, the purpose of the study was presented to the school and the women involved, who were given the opportunity to ask questions. Written informed consent was obtained, which included agreement to participate in the study and permission for the dissemination and publication of the results.

This qualitative study did not aim to provide a representative sample. Instead, it sought to generate in-depth understanding of the experiences and contributions of participants within specific social and educational contexts. The evidence was drawn from a specific number of interviews with women without higher qualification participants in DFGs. No additional interviews were conducted due to saturation, understood as the point at which no new themes relevant to the research questions emerged. However, beyond saturation, decisions throughout the development of the project were taken dialogically, involving both researchers and participants, with the aim of generating deeper knowledge that contributes to advancing the inclusion and empowerment of women without academic qualifications through actions grounded in scientific evidence of social impact.

3.2. The Context of the Case Study

This case study was conducted at an adult education school located in a working-class neighbourhood in the city of Barcelona. Founded in 1978, the school emerged as a pioneering initiative in adult education, grounded in the principles of democratic participation and dialogic learning (Giner 2018). Since its inception, the school had been characterized by its strong commitment to dialogic and transformative education. It was internationally recognized as the birthplace of Dialogic Gatherings, a successful educational action that included the DFGs analyzed in this study. These gatherings were developed within the framework of dialogic learning and popular education, particularly with and for women without academic backgrounds, and had since become a key tool for both personal and social transformation.

This context provided a strong foundation for analyzing the impact of DFGs, particularly among women without academic qualifications. The school’s inclusive and dialogic approach offered the ideal conditions to understand how DFGs contributed to empowerment and the prevention of gender violence.

3.3. The Intervention: The Dialogic Feminist Gatherings

Since the creation of the school, DFGs had been implemented as part of its educational actions. From 2019 onwards, they were carried out more regularly, as the participating women expressed a growing concern with intensifying their work to contribute to the prevention of gender violence through their everyday lives. The present case study was conducted over four academic years: 2021–2022, 2022–2023, 2023–2024, and 2024–2025. During the first two years, the DFGs were held on a weekly basis, reflecting the participants’ strong initial engagement and interest. In the following years, the frequency was adjusted to once a month, based on the group’s shared decision to maintain a sustainable rhythm of participation while ensuring continuity and collective reflection. Each session of the DFGs lasted between one hour and one and a half hours, with the number of participants varying depending on their availability, typically ranging from 10 to 20 women. The participants came from diverse backgrounds but shared a common characteristic: they were women between the ages of 55 and 85, with little or no formal basic education, many of whom had migrated to Barcelona from other regions of Spain during the 1960s and 1970s.

The DFGs followed a structured format specifically designed to contribute to the prevention of gender violence. The readings discussed in each session included open-access scientific articles, rigorously written outreach materials, and books or book chapters that presented evidence-based actions, debates, or concepts with proven social impact in the preventive socialization of gender violence across diverse contexts. In cases where scientific articles or materials with very academic language were read, the research team made some adaptations, always without removing the academic terms related to the most important concepts and main contributions. This approach was designed to support participants in progressively acquiring new vocabulary and becoming familiar with academic language, thereby enhancing their understanding and engagement with the material.

The list of readings was prepared by the research and education team based on topics previously chosen by the participants. These topics included, for example, the prevention of gender violence from early childhood, effective programs for prevention, how to contribute to prevention from the community, how to promote non-violent models of masculinity among sons and grandsons, and overcoming the coercive dominant discourse that portrayed violent attitudes as desirable, among others. In the case of books or book chapters, the specific pages to be read for each session were agreed upon in advance.

Each participant read the selected text before the session and chose a paragraph that resonated with her, which she would later share and reflect upon during the gathering. On the day of the DFG, the session was moderated by a member of the re-search team. Moderation followed dialogic principles, ensuring respect for speaking turns and prioritizing the participation of those who had not yet spoken or had spoken less. The moderator invited participants to read their chosen paragraph and explain why they selected it, then facilitated the dialogue that emerged from each contribution.

All interventions were valued based on the strength of their arguments and within a framework of respect for human rights. The gatherings were not led by “experts”; rather, every participant contributed ideas, reflections, and knowledge from their own experiences and perspectives. The space was grounded in the principles of dialogic learning (Flecha 2000).

3.4. Participants

This study counted eight participants, all of whom were women without higher educational qualifications and all of whom participated in the DFGs focus of the research. Their ages ranged from 55 to 85 years. Six participants were involved in the communicative focus group (CFG), while four contributed through communicative life stories (CLS); two participants engaged in both of them. In accordance with the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED), six participants had completed primary education (L1), whereas two had attained lower secondary education (L2). To safeguard anonymity, pseudonyms were assigned to each participant. Table 1 provides a comprehensive overview of participants’ profiles, including pseudonym, technique, age range, gender, and educational level.

Table 1.

Participants’ profile.

3.5. Data Collection

To conduct the case study, communicative research techniques were employed. The communicative methodology was grounded in egalitarian dialogue between researchers and participants, ensuring that all voices were equally valued throughout the research process. Researchers contributed prior scientific evidence while participants brought their lived experiences. Through this dialogic interaction, interpretations were co-created, resulting in new scientific knowledge that emerged from the consensus between researchers and participants. This approach broke traditional hierarchies between those who research and those who are researched, fostering a collaborative environment in which knowledge was not only shared but jointly generated. The communicative data collection techniques used in this study included communicative observations during the DFG sessions, communicative life stories, and a communicative focus group with the participating women.

Communicative observations conducted during the DFGs were a key data collection technique in this study. These communicative observations took place over four academic years (2021–2025), within a context of sustained trust and collaboration between the research team and the participating women. Some of the researchers had both moderated and taken part in the DFGs during this period. This long-standing relationship contributed to the creation of a safe and dialogic environment. Unlike traditional participant observation, communicative observation involved not only active engagement in the sessions, but also informal conversations held afterwards between researchers and participants. These dialogues were essential for jointly interpreting the situations that were experienced during the gatherings, ensuring that the meanings and transformations observed were accurately understood and mutually agreed upon.

The communicative life story was a biographical narrative cocreated through egalitarian dialogue between the researcher and the participant. It was not a one-sided account, but a shared interpretative process that explores key aspects of the participant’s past and present, as well as future expectations. In the context of this study, the technique was used to understand how participation in DFGs had influenced women’s lives, particularly in relation to the prevention of gender violence. It allowed researchers to explore how the gatherings impacted not only the participants themselves, but also their families and community (shaping attitudes, relationships, and socialization patterns). The communicative life stories were conducted in a classroom at the adult education school, providing a familiar and comfortable setting that supported open and natural communication. While typically carried out in a single session, a follow-up conversation was sometimes held to confirm interpretations, expand on relevant aspects, and cocreate final conclusions.

A communicative focus group was conducted with the participating women to collectively reflect on their experiences in the DFGs and deepen the analysis of the impact on their personal lives, families, and community, particularly regarding the prevention of gender violence. Grounded in egalitarian dialogue, this technique fostered open and respectful exchanges between researchers and participants, where all voices were equally valued. Rather than merely collecting opinions, the communicative focus group aimed to collectively co-create interpretations of the transformative processes experienced by the women. Through this dialogic interaction, participants not only identified and articulated the changes they had undergone and observed but also engaged in new forms of reflection and awareness. In this way, the communicative focus group itself became a space of transformation, reinforcing the impact of the DFGs and further contributing to the participants’ social engagement.

3.6. Data Analysis

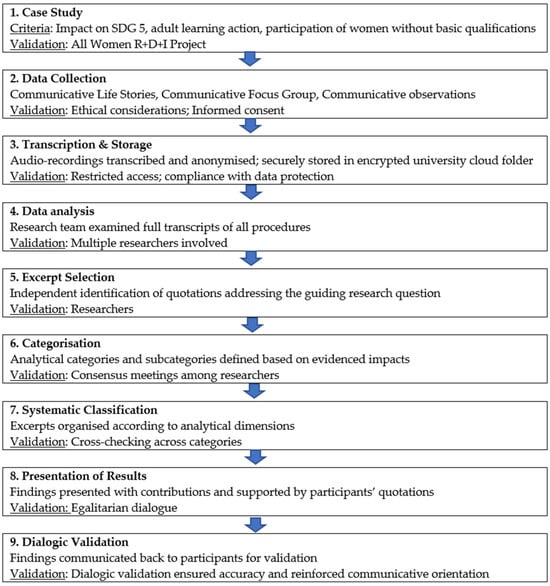

Communicative life stories and the communicative focus group were audio-recorded and subsequently transcribed. Both the audio files and the anonymized transcripts were securely stored in an encrypted cloud folder of the University of Barcelona, with access restricted exclusively to the research team members responsible for this task. The data were analyzed using a thematic analysis that combines both deductively (from the literature and research questions) and inductively (emerging from the data). The identification of themes was achieved through discussion and consensus among the research team. For analyzing the gathered information, the research team initially reviewed the complete transcripts of the data collection process. Afterwards, different researchers independently identified quotations that directly responded to the research question: What impact did DFGs have on participating women, their families, and their community, particularly in terms of preventing gender violence? After identifying the pertinent excerpts, the team defined analytical categories based on the impacts that were observed. The first category encompasses evidence of the impact of these DFGs on the participants themselves. From this category emerge the following subcategories: (1) Building Confidence, (2) Identifying Risk and Protective Factors, and (3) Naming Personal Experiences of Gender Violence as Breaking the Silence through Dialogue. The second category comprises evidence of the impact of these DFGs on the participants’ families. From this category arise the subcategories: (1) Promoting Empathy and Courage in Young Children, (2) Shifting Patterns of Behavior and Socialization in Adolescents, and (3) Recognizing and Responding to Isolating Gender Violence. The third category includes evidence of the impact of these DFGs on the wider community of the participants. This category gathers evidence related to fostering collective solidarity and prevention. Once the categories and subcategories had been defined, the chosen excerpts were methodically organized in line with the relevant analytical dimension. In the final stage, each finding was presented alongside its particular contribution and substantiated with participants’ quotations, thus guaranteeing that the results were firmly anchored in empirical evidence as well as dialogic interpretation. During the data analysis, the perspectives of participants were carefully taken into account to illuminate emerging themes and to guarantee their faithful representation in the results. After the findings had been consolidated, they were shared with the participants and underwent dialogic validation, thereby safeguarding accuracy and strengthening the communicative orientation of the research. Figure 1 summarizes the methodological steps and validation techniques employed in this study.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of Methodological Steps and Validation Techniques.

3.7. Ethical Considerations

The study is framed within the R + D + i research project ALL WOMEN “The empowerment of all women through adult education for a sustainable development” (PID2020-113137RA-I00), which was funded and received positive evaluation across all its dimensions, including ethics and data management, by the State Research Agency of the Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities of Spain (MICIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033). Additional funding and ethical supervision came from the predoctoral program AGAUR-FI Joan Oró, grant number 2024 FI-1 00909, promoted by the Secretariat of Universities and Research of the Generalitat de Catalunya, together with the European Social Fund Plus.

The study strictly complied with all ethical standards and the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Full anonymity and confidentiality of participants’ data were guaranteed throughout the research process. Personal identifiers were replaced with pseudonyms, which were consistently used for both data analysis and dissemination. All information was used exclusively for the purposes of the project and for scientific publications and presentations. Data were stored securely on password-protected devices within the University of Barcelona ’s cloud system, accessible only to members of the research team. From the outset, all information was anonymized and safeguarded in the designated secure system. Prior to participation, each individual received a written informed consent form detailing the project’s identification, objectives, expected involvement, data protection measures, and their right to withdraw at any time without consequences. In addition to the written document, this information was explained and discussed with participants to ensure understanding and address any questions. All participants provided signed informed consent before taking part in the study.

4. Results

The following section presents the main findings of the case study, highlighting the transformative impact of DFGs on the participating women, their families, and their community. The results were organized into thematic areas that emerged from the communicative observations, communicative life stories, and communicative focus group, illustrating how the DFGs fostered personal empowerment, intergenerational dialogue, and collective action for the prevention of gender violence.

4.1. Impact on Themselves: Transformative Effects of Participating in Dialogic Feminist Gatherings

4.1.1. Building Confidence

One of the most recurrent impacts described by the participants was the strengthening of self-confidence. Many of them entered the DFGs with a sense of insecurity or silence, and through the dialogic process, they began to speak, reflect, and feel valued. As Esperanza explained, her participation in the DFGs helped her overcome deep-seated fears and physical manifestations of anxiety:

I never imagined I had any capacity to communicate. I used to stay silent in the gatherings. I got so nervous that I ended up with neck pain from the tension. But now I don’t stop talking. It’s reciprocal; I don’t know if I give more than I receive.(Esperanza)

This transformation was echoed by Clara, who highlighted how the readings and dialogues opened new perspectives for women of her generation:

The gatherings have been very important for many reasons. The articles we’ve read have enriched us so much. I only have praise for these gatherings. All this has opened us up, especially those of us who weren’t prepared for it, particularly at my age.(Clara)

Similarly, Inés shared how participating in the DFGs allowed her to redefine her understanding of feminism and, for the first time, feel part of it. Before joining the gatherings, her only references to feminism came from academic or elitist spaces that had historically excluded women like her, women without formal education or university degrees. As a result, although she had always disagreed with gender inequalities and protested against injustices, she did not identify herself as a feminist:

I always had an idea of feminism, but I didn’t consider myself a feminist. I started to distinguish what feminism was and what it wasn’t, especially the kind that had excluded us for not being academics or for having basic levels of education.(Inés)

These testimonies illustrated how the DFGs became spaces of personal transformation, where women not only acquired new knowledge but also recognized and strengthened the actions they were already carrying out in their everyday lives to challenge inequality. They also questioned internalized limitations and reinforced their self-esteem. At the same time, these spaces validated values and knowledge that many of them already held, as well as their disagreement with the injustices they experienced as women, a reality they were fully aware of through lived experience, even if they did not identify as feminists.

4.1.2. Identifying Risk and Protective Factors

One of the most significant impacts of the DFGs was the way they enabled participants to identify both risk factors and protective factors related to gender violence. Through the collective reading and dialogic analysis of scientific evidence, women not only gained knowledge but also learned to apply it to real-life situations, both in their own lives and in their communities.

A particularly powerful example of this learning process was the impact of reading and discussing the Zero Violence Brave Club, an evidence-based educational action that promoted collective positioning against violence in schools and other social settings. This initiative encouraged children and adolescents to actively support peers who were victims of violence. The key mechanism was breaking the social admiration that often surrounded violent attitudes. Esperanza, after engaging with this evidence in the DFG, reflected on how this dynamic played out in real life. She described how children who previously held social status through violent behavior began to realize that their peers no longer admired or supported them. This shift, she explained, initially led to behavioral change out of self-preservation, but over time, it resulted in a genuine transformation:

I believe that these children, it’s just my impression, do not initially change out of genuine conviction, but notice that their friends no longer admire them. In other words, their world starts to shrink; if before they were at the centre with lots of people around them, now they are not. So, out of a kind of survival, they think: ‘I need to change my attitude.’ And then they switch sides, which I imagine isn’t easy for them, but I believe they gradually become influenced by the behaviour of their peers, and they come to realise that being good is actually better.(Esperanza)

What she described was not just a reduction in violent behavior, but a reorientation of values and social identity. These children do not merely stop bullying; they began to adopt protective roles, aligning themselves with those who defended others and contributed to a safer, more respectful environment. This shift was a clear example of how transformative socialization could occur when violence was no longer socially rewarded, and when non-violent, supportive behaviors were admired and reinforced. This transformation was closely linked to the concept of New Alternative Masculinities (NAM), which was also explored in the DFGs. NAM referred to men who rejected the coercive dominant discourse, which associated masculinity with violent behavior, and instead embodied equality and active opposition to violence. These men were not only non-violent; they were admirable and desirable precisely because they took a clear stand against violence and supported others in doing so.

By engaging with scientific evidence on NAM and the Zero Violence Brave Club, participants in the DFGs began to redefine what was attractive, admirable, and socially valuable, both in men and in interpersonal relationships more broadly. This had a direct impact on how they related to others, how they educated younger generations, and how they contributed to building communities where violence was not tolerated, and solidarity was celebrated.

4.1.3. Naming Personal Experiences of Gender Violence: Breaking the Silence Through Dialogue

One of the most profound impacts of the DFGs was the way they enabled women to recognize and name experiences of gender violence that they had previously normalized, silenced, or not fully understood. This process of recognition was not only cognitive, but also deeply emotional and social, as it occurred within a respectful and egalitarian space where all voices were valued and no one was judged. An example of this was the experience of Luz, who, during one of the DFG sessions, shared for the first time a story of stalking and sexual harassment by an ex-partner, a situation she had lived through years earlier but had never identified as gender violence. It was through the collective reading of scientific evidence and the dialogic reflection that followed that she was able to denormalize what had happened to her, connect it to broader patterns of violence, and finally give it a name:

It was the first time in my life that I opened up and actually said it. I spoke about something that had happened to me. I had never told anyone, because I had never seen it as that. So having done it, having verbalised it there… I don’t even know how I managed. To explain something so intimate, something you’ve been carrying in silence. But well, that’s how I felt. It’s true that it happened many years ago, but even so… because when you’re living through situations like that, you don’t perceive them as such, no one tells you. I’m talking about many years ago now… later on, things start to escalate, and you begin to realise it’s not normal and that it could get worse. But you still don’t name it. All you say is that the person is unstable, obsessed, won’t let you live… but you don’t say ‘I was a victim of…’ So I named it here. This was the place where I finally put a name to what really happened to me.(Luz)

This moment of verbalization and recognition was not an isolated act, but the result of a collective process of reflection and support. The DFGs created a space where women felt accompanied, not alone, and where the dialogue was grounded in mutual respect and shared purpose. The fact that all contributions were equally valued, regardless of academic background or personal history, fostered a climate of trust that allowed participants to go deeper into the issues that mattered most to them.

This environment also facilitated the development of solidarity and friendship among participants. In the case of Luz, her openness was met with support from others in the group. As Auroa shared, after experiencing a traumatic event herself, she found comfort in the presence of Luz: “Well, I just wanted to say that, when I was mugged in the entrance to my building, I came here, and she (Luz) gave me a hug.” These inter-actions illustrated how the DFGs functioned not only as educational spaces, but also as networks of solidarity. The dialogic approach of the DFGs, based on egalitarian dialogue, scientific evidence, and the recognition of lived experience, enabled participants to challenge silence, and build new meanings together.

4.2. Impact on Families: Intergenerational Dialogues and Preventive Socialization

One of the most significant outcomes reported by participants in the DFGs was the way in which the knowledge, reflections, and emotions shared during these sessions extended beyond the gatherings themselves and into their family environments. Through intergenerational dialogue, participants have become active agents in reshaping the socialization of children, grandchildren and other family members, fostering attitudes and behaviors that rejected violence and promoted solidarity, empathy, and equality.

4.2.1. Promoting Empathy and Courage in Young Children

The DFGs had proven to be a space for intergenerational learning, where women not only gained knowledge and critical awareness but also became active transmitters of values that challenged exclusion and promoted solidarity. One particularly illustrative case was that of Clara, who shared how the dialogues in the DFGs enabled her to engage in a transformative conversation with her four-year-old granddaughter. The situation arose when the granddaughter described a classmate with learning difficulties who was being mistreated by other children. Initially, the girl did not intervene to support him. However, Clara used this moment as an opportunity to connect the values discussed in the DFGs with her granddaughter’s everyday experiences. Drawing on the principles of mutual respect and zero violence, she explained the importance of standing up for others.

Rather than simply instructing her granddaughter, Clara highlighted the positive example of another child in the class, a girl who consistently defended the boy being excluded. She praised this child’s actions as courageous and admirable, framing her as a role model worth emulating:

What your friend is doing is wonderful. I think she has a heart of gold, and she’s managing to inspire many others to follow her lead. And you know what? It would give me the greatest joy to know that you’re the one standing by your friend and helping that boy.(Clara)

This conversation had a clear and meaningful impact. She later observed a noticeable shift in her granddaughter’s behavior, from passive observation to actively standing up for a classmate who was being excluded. This case exemplified how DFGs empowered women to become role models within their families. By translating scientific knowledge and dialogic reflections into everyday language and actionable guidance, participants like Clara contributed to a preventive socialization against violence among younger generations. The result was not only a change in the child’s individual behavior, but also a broader transformation in how families perceived and responded to situations involving violence, exclusion, and vulnerability.

4.2.2. Shifting Patterns of Behavior and Socialization in Adolescents

The DFGs had proven to be a powerful space for rethinking the socialization of adolescents, particularly through intergenerational dialogue grounded in scientific evidence. In the case of Luz, the knowledge and reflections shared in the gatherings became a catalyst for change in both her grandson and her son. The knowledge shared in the gatherings enabled her to engage in meaningful conversations with her grandson about the nature of true friendship, one that was free from any form of violence, and about alternative masculinities that were courageous precisely because they took a stand against violence. Previously, the boy had exhibited aggressive behavior toward his sister. These dialogues challenged dominant notions of masculinity and helped her grandson reflect on the importance of kindness, and standing by others, especially those who were vulnerable. As a result, he began to distance himself from aggressive behaviors and instead sought friendships with peers who embodied egalitarian values and respect, which he increasingly associated with courage. His teacher even acknowledged the change, sending a note to his father to express appreciation for the boy’s progress:

I’ve spoken with him (grandson) a little about what we discussed, about friendship and all of that, and my son told me that the teacher sent him a note to thank him. I was astonished. His relationship with his sister is beginning to change.(Luz)

Equally significant was the transformation observed in Luz’s son, the father of the child. While not overtly sexist, he had previously expressed attitudes shaped by dominant gender norms. Through sustained conversations with his mother, who drew on the scientific and dialogic content of the DFGs, he began to reflect more critically on these norms and to adopt more egalitarian practices in his daily life. This included redistributing household responsibilities and encouraging his children to participate in domestic tasks, as well as rethinking his assumptions about gender roles in social contexts:

Now, when they come over for lunch, the children are the ones who set the table, clear it, and load the dishwasher. And it’s not just that; it’s also about his mindset. In everyday things, for instance, when he tells me something about a colleague at work (an opinion about a woman) I’ll ask him, ‘And why do you see it that way?’ and he’ll say, ‘Oh, I hadn’t thought of that.(Luz)

The depth of this transformation was further revealed in the son’s growing curiosity about the source of his mother’s insights. He began to ask her who was advising her, to which she responded by highlighting the collective learning and dialogue that took place in the DFGs: He says to me, ‘Who advises you on all these things?’ And I say, ‘I talk a lot with my friends. (Luz)

This exchange illustrated how DFGs not only had a social impact on the women who participated but also positioned them as respected voices within their families, capable of fostering change through reasoned dialogue and shared reflection. The case of Luz demonstrated how DFGs contributed to the preventive socialization of gender violence by diminishing the appeal and perceived legitimacy of violent behaviors, while promoting relationships grounded in respect, solidarity, and equality. Within this transformed family environment, both adults and children began processes of change that delegitimized violence and reinforced models of coexistence that positioned themselves against violence as courageous, attractive, and therefore desirable attitudes.

4.2.3. Recognizing and Responding to Isolating Gender Violence

Another key impact of the DFGs was the participants’ increased ability to identify and respond to more complex forms of gender violence, such as isolating gender violence. This form of violence, discussed in the gatherings through scientific literature, refered to the retaliatory actions carried out by aggressors against individuals who supported victims of gender violence. Its purpose was to ensure that the victim remained socially isolated by discouraging solidarity and punishing those who broke the silence. This dynamic was clearly reflected in the experience shared by Auroa, whose daughter was bullied at school. Despite the suffering she endured, no one initially defended her, a silence likely rooted in fear of becoming the next target. It was only when a peer, a girl who had repeated the year, bravely chose to support her that the isolation began to break:

My younger daughter was bullied at school, and no one defended her. She had a hard time, until one day a girl who had repeated a year approached her and said, ‘Then come and play with me. I’m older than them.’ That girl is still my daughter’s friend to this day.”(Auroa)

Through the DFGs, Auroa was able to name this dynamic as isolating gender violence and, crucially, to recognize the role that bystanders played in breaking it. The support offered by the girl who stood by her daughter was a decisive factor in ending her isolation and restoring her confidence. This process of naming and understanding allowed her to reframe the experience, not only as a moment of suffering, but also as an example of how solidarity and courage could disrupt the mechanisms that sustained violence.

Sara offered a complementary perspective, describing how her grandson often felt distressed when he saw classmates being excluded. Despite his young age, he consistently tried to include and protect others, even though doing so sometimes led to his own social isolation. His grandmother, drawing on the values reinforced in the DFGs, supported and validated his actions: He said, ‘grandma, they won’t let that boy play with us,’ and he was crying. I told him, ‘You don’t need to cry, darling, just ask him to play with you.’ (Sara).

This exchange showed that the grandmother, guided by the DFGs’ values, encouraged her grandson to stand with excluded peers through inclusive actions, reinforcing solidarity.

4.3. Community Impact of the DFGs: Fostering Collective Solidarity and Prevention

Beyond the personal and familial transformations described by the participants, the DFGs have also fostered a deep sense of collective responsibility and solidarity toward their community. Motivated by the violence they observed in their surroundings, affecting individuals across generations and social contexts, the women took concrete steps to extend the impact of the gatherings beyond the educational setting. In response to these concerns, they decided to open the DFGs to the broader neighbourhood, aiming to build a shared commitment to the prevention of gender violence. As Esperanza emphasizes, this was a responsibility that must be collectively embraced, both in schools and within families: It is certainly important, both in schools and within the family environment. This is an educational responsibility we must all promote. (Esperanza)

Through the DFGs, participants developed the ability to identify how gender violence was normalized in their community, particularly among adolescents, and began to challenge these patterns. Clara, for example, expressed concern about the submissive attitudes she observed in some young girls toward boys who displayed controlling or aggressive behavior. Her reflections revealed a desire to intervene and raise awareness among young women in her neighbourhood:

Girls must be educated to ensure they never allow anyone to cross the line, not even slightly. […] I live near a secondary school and have sometimes overheard conversations on the bench that made me want to say, ‘Hang on a moment, love, do you really have to put up with that boy speaking to you like that?’(Clara)

This growing awareness was accompanied by concrete actions. Several participants have taken proactive steps to prevent violence in their community, particularly in situations involving children and adolescents. Violeta described how she acted to protect her daughter and nieces from a known perpetrator within the family, and how she warned her brother to ensure his daughters were never left alone with that person: I told my brother, ‘Look, this happened to me, please be careful.’ I also had a daughter myself, and I never, not for a single second, left her alone with that person. (Violeta)

These testimonies reflected a shift from individual concern to collective vigilance. The women are not only protecting their own families but also assuming a role of community care, sharing information and resources to support others. Clara, for instance, recalled how she distributed the emergency helpline number for women experiencing gender violence, a number that does not leave a trace on phone bills, to neighbours who were still trapped in situations of fear and isolation: A few years ago, there was the women’s helpline number, and I gave it to some people. That number had a real impact, for women who were still cornered. (Clara)

The participants also reflected on the broader social changes they have witnessed and contributed to. Auroa spoke about the generational shift she observed in her grandchildren, noting how the progress made by women in previous decades had laid the foundation for more egalitarian relationships in the future. As Celia reflected, “when women participate in women’s spaces, they feel capable of facing many other things in society.” These reflections demonstrated how the DFGs have not only empowered individual women but have also fostered a collective sense of solidarity and proactive engagement in the prevention of gender violence. Through DFGs, the participants became active agents in reshaping their community, identifying risks, supporting victims, and promoting a culture of solidarity to act collectively against gender violence.

This collective engagement also extended into institutional spaces. As Inés shared, “we participated in the national women’s council […] we made several proposals and two of them were accepted.” Her testimony illustrated how the DFGs equipped participants with the confidence and knowledge to contribute meaningfully to public policy.

5. Discussion

The findings of this study contribute to the growing body of evidence on the transformative potential of DFGs in preventing gender violence, particularly among adult and older women without academic qualifications. While previous research had demonstrated the impact of DFGs in formal educational settings with adolescents and university students (Puigvert 2016; Ruiz-Eugenio et al. 2020), this study expanded the scope by highlighting how these gatherings also foster empowerment, critical aware-ness, and collective action among women who have historically been excluded from academic and feminist discourses (Grau-del-Valle et al. 2025).

This case study was especially significant given its setting: the adult education school in Barcelona where DFGs were first created in the late 1970s. Despite the historical importance of this school in the development of dialogic feminist practices, no previous case study had systematically documented the impact of the DFGs. This research addressed that gap by focusing on the experiences of participants over the last four academic years, offering new insights into the intergenerational and community-level effects of DFGs.

The findings of this study resonate with international evidence on the transformative potential of dialogic educational actions (Soler 2015). Rita Levi-Montalcini, Nobel Prize laureate, demonstrated the lifelong plasticity of the human brain, showing that adults continue learning and have much to contribute throughout their lives (Levi-Montalcini 1998). In line with this evidence, our study provides evidence that women without academic qualifications, most of them over 65 years old, not only continue to learn but also lead their own learning processes and drove both their personal transformation and that of their communities towards the eradication of gender violence. The INCLUD-ED project identified Successful Educational Actions (SEAs) such as interactive groups, dialogic gatherings, and family participation, which demonstrated measurable social impact across diverse contexts (Flecha 2015). Our results align with this evidence, showing how DFGs contribute to empowerment and social cohesion. Furthermore, recent research emphasizes the importance of upstander intervention and breaking the silence in the face of gender violence. For instance, Banyard and colleagues highlighted how bystander engagement can shift dynamics from passive observation to active support, thereby challenging the law of silence that often surrounds gender violence (Banyard et al. 2025).

The results align with the principles of dialogic learning (Flecha 2000), which emphasize egalitarian dialogue, the co-creation of knowledge, and the transformative power of collective reflection. In the DFGs, participants not only engaged with scientific evidence on gender violence but also connected it to their lived experiences, enabling them to identify risk and protective factors, redefine social norms, and challenge normalized patterns of violence in their families and community. These processes reflect the core tenets of dialogic feminism, which recognizes the contributions of all women, regardless of their educational background or social status (Flecha and Puigvert 2010).

A key contribution of this study is the way it challenges the coercive dominant discourse, a socialization patterns that links attractiveness and social value to violent behaviors (Puigvert et al. 2019). Through dialogic reflection, participants were able to transform this discourse and promote alternative models based on respect, equality, and non-violence. This shift not only influenced their own affective relationships but also shaped how they educated younger generations, contributing to a broader cultural and social transformation.

Moreover, the study provides empirical support for the theoretical framework of the other women movement and dialogic feminism (Beck-Gernsheim et al. 2003), which calls attention to the voices and agency of non-academic women in the struggle for gender equality. Participants in this study, many of whom had never identified as feminists, found in the DFGs a space to reclaim their narratives, validate their knowledge, and engage in actions that contribute to the prevention of gender violence. As one participant noted, “we didn’t consider ourselves feminists, but we were already fighting in our own way.” This recognition challenges elitist conceptions of feminism and affirms the value of grassroots, community-based approaches to social transformation. The findings resonate with Fawcett’s (2022) critique of exclusionary feminist discourses that had historically marginalized non-academic women. By engaging in DFGs, participants not only reclaimed their narratives but also challenged the notion that feminist agency was reserved for those with formal education. This aligns with Fawcett’s argument that feminist theory has to embrace plurality, recognizing the transformative potential of diverse lived experiences in shaping community action.

The intergenerational impact observed in this study was particularly noteworthy. Through dialogic interactions with children, grandchildren, and other family members, participants became active agents of preventive socialization, promoting values of empathy, equality, and non-violence. These findings echo previous research on the ripple effects of DFGs in family contexts (Rodrigues de Mello et al. 2021) and underscore the importance of including adult education spaces in strategies to combat gender violence (Fawcett and Reynolds 2010).

Importantly, the study also reveals how DFGs foster a collective sense of solidarity committed to active engagement in prevention and support for victims. Participants not only protected their own families but also took proactive steps to support neighbours, intervened in risky situations, and advocated for institutional change. This shift from individual empowerment to collective responsibility illustrates the potential of DFGs to generate sustainable social impact at the community level.

Despite the relevance of these findings, this study has certain limitations. It was based on a single case study conducted in a unique educational context, an adult school with a long-standing tradition of dialogic pedagogy and feminist organizing. While this context offered rich insights, it may not be representative of other adult education settings. Future research should explore the implementation and impact of DFGs in more diverse environments, including rural areas, different cultural contexts, and among younger women. Further research is needed to explore how DFGs can be supported through public policy. Investigating the conditions that enable their sustainability and scalability could contribute to advancing gender equality and violence prevention in adult education and communities worldwide (Muafiah et al. 2025).

While this study provides valuable insights into the impact of DFGs, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the research was conducted within a single adult education school in Barcelona, which should be considered when assessing the transferability of the findings to other contexts and when comparing them with evidence from other existing studies. Second, the study relied on a specific group of participants, all of whom were women without higher educational qualifications. These limitations should be taken into account when interpreting the findings, and future research could address them by including additional contexts, broader participant profiles, comparative designs, and consideration of other studies to enhance applicability. To further clarify the relevance of the findings, Table 2 summarizes the key takeaways of the study and outlines their implications for policy, practice, and future research.

Table 2.

Key Takeaways and Implications.

6. Conclusions

This study examined the impact of DFGs within the framework of adult education and dialogic learning, focusing on women without higher educational qualifications. The findings demonstrated that participation in DFGs fostered empowerment at different levels: individually, by strengthening confidence and enabling the identification of risk and protective factors; within families, by promoting empathy in younger generations and reshaping behavioral and socialization patterns; and at the community level, by reinforcing collective solidarity and preventive attitudes towards gender violence. The study contributed to the literature on adult learning and gender equality by evidencing how dialogic educational actions generated transformative effects aligned with the targets of SDG 5, while the communicative methodology ensured the co-creation of knowledge and reinforced the validity of the results.

The implications of these findings can be summarized thematically: DFGs provide evidence to inform policy on adult education and gender equality strategies; they offer practical guidance for practice by integrating dialogic principles into educational and community programs; and they open avenues for research by encouraging comparative studies across diverse contexts and participant profiles to further explore their applicability.

The evidence underscores the potential of DFGs as a Successful Educational Action for the prevention of gender violence and the empowerment of women without higher educational qualifications, demonstrating that the integration of dialogic principles into adult learning fosters personal transformation and contributes to broader social change.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.R.-E., L.P. and A.C.-L.; methodology, L.R.-E. and A.C.-L.; formal analysis, L.R.-E., A.C.-L. and A.L.d.A.; data curation, L.R.-E., A.C.-L. and A.L.d.A.; writing—original draft preparation, L.R.-E. and A.C.-L.; writing—review and editing, L.R.-E., L.P. and A.L.d.A.; supervision, L.R.-E.; funding acquisition, L.R.-E. and A.C.-L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was co-funded by the State Research Agency of the Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities of Spain (MICIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033), grant number PID2020-113137RA-I00, and by the predoctoral program AGAUR-FI Joan Oró, grant number 2024 FI-1 00909, promoted by the Secretariat of Universities and Research of the Catalan Government (Generalitat de Catalunya), together with the European Social Fund Plus.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical considerations were detailed in both the initial and final project reports, which were reviewed within the evaluation process carried out by the State Research Agency of the Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities of Spain (MICIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033). The initial evaluation was issued on 20 June 2021. On 27 January 2025, the Spanish State Research Agency issued a favorable final evaluation following the review of the project’s final report, which included the results, ethical considerations, and the data management plan.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the participants to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets are not directly available online to ensure the necessary level of confidentiality and the legitimate utilization of the data. Researchers interested in accessing any of the datasets are kindly requested to make a formal request by sending an email to the corresponding author (lauraruizeugenio@ub.edu). This request should be accompanied by the following documents: a formal letter containing the researcher’s contact information, institutional affiliation, current position, the purpose of the research, details regarding the intended use of the data, and, if applicable, information about funding sources; an official letter from the researcher’s affiliated university or research institution confirming their association; and a confidentiality agreement, duly signed by the researcher, indicating their commitment to maintaining the confidentiality of the data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- American Psychological Association. 2022. Bystander Intervention Tip Sheet for Preventing Sexual and Interpersonal Violence. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. Available online: https://www.apa.org/pi/health-equity/bystander-intervention (accessed on 19 April 2024).

- Aubert, Adriana, and Ramon Flecha. 2021. Health and Well-Being Consequences for Gender Violence Survivors from Isolating Gender Violence. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18: 8626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banyard, Victoria, Kimberly J. Mitchell, Kimberly L. Goodman, and Michele L. Ybarra. 2025. Bystanders to sexual violence: Findings from a national sample of sexual and gender diverse adolescents. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 40: 1221–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck-Gernsheim, Elisabeth, Judith Butler, and Lidia Puigvert. 2003. Women and Social Transformation. Lausanne: Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Connell, Raewyn. 2012. Gender, health and theory: Conceptualizing the issue, in local and world perspective. Social Science & Medicine 74: 1675–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connell, Raewyn, and James W. Messerschmidt. 2005. Hegemonic masculinity: Rethinking the concept. Gender & Society: Official Publication of Sociologists for Women in Society 19: 829–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fawcett, Barbara. 2022. Feminisms: Controversy, contestation and challenge. In Re-Thinking Feminist Theories for Social Work Practice. Edited by Christine Cocker and Trish Hafford-Letchfield. London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 19–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fawcett, Barbara, and Jeynolds Reynolds. 2010. Mental health and older women: The challenges for social perspectives and community capacity building. The British Journal of Social Work 40: 1488–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flecha, Ainhoa, and Lidia Puigvert. 2010. Contributions to social theory from dialogic feminism. In Teaching Social Theory. Edited by Paul Chapman. Lausanne: Peter Lang, pp. 161–76. [Google Scholar]

- Flecha, Ramón. 2000. Sharing Words: Theory and Practice of Dialogic Learning. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. [Google Scholar]

- Flecha, Ramón. 2015. Successful Educational Action for Inclusion and Social Cohesion in Europe. New York: Springer Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Flood, Michael, and Bob Pease. 2009. Factors influencing attitudes to violence against women. Trauma, Violence & Abuse 10: 125–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebo, Erika, and Brianna Franklin. 2023. Exploring Responses to Community Violence Trauma Using a Neighborhood Network of Programs. Social Sciences 12: 518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giner, Elisenda. 2018. Creative Friendships. Barcelona: Hipatia Press. Available online: https://hipatiapress.com/index/en/2021/10/07/amistades-creadoras-en/ (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- Gómez, Jesús. 2015. Radical Love: A Revolution for the 21st Century. Lausanne: Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Grau-del-Valle, Carolina, Laura García-Raga, Mireia Barrachina-Sauri, and Esther Roca-Campos. 2025. Learning community and employability. Roma women’s voices. Multidisciplinary Journal of Gender Studies 14: 44–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jewkes, Rachel, Michael Flood, and James Lang. 2015. From work with men and boys to changes of social norms and reduction of inequities in gender relations: A conceptual shift in prevention of violence against women and girls. Lancet 385: 1580–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, S. Shantha, Anne-Beatrice Kihara, Rubina Sohail, Hadia Majid, Kristina Gemzell-Danielsson, and Giuseppe Benagiano. 2025. Preventing gender-based violence: A global imperative. International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics: The Official Organ of the International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics 169: 1133–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levi-Montalcini, Rita. 1998. The Aging Brain: The Paradox of Longevity. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Maber, Elizabeth. J. T. 2016. Finding feminism, finding voice? Mobilising community education to build women’s participation in Myanmar’s political transition. Gender and Education 28: 416–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mainwaring, Chelsea, Fiona Gabbert, and Adrian J. Scott. 2023. A systematic review exploring variables related to bystander intervention in sexual violence contexts. Trauma, Violence & Abuse 24: 1727–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marphatia, Akanksha A., and Rachel Moussié. 2013. A question of gender justice: Exploring the linkages between women’s unpaid care work, education, and gender equality. International Journal of Educational Development 33: 585–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos, Marlene, Jacinta Sousa, Sónia Caridade, and Isabel Dias. 2025. Sexual exploitation: Professionals’ and stakeholders’ perceptions of prevention, assistance, and protection for victims in Portugal. Social Sciences 14: 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Equality. 2020. 2019 Survey on Violence Against Women; Madrid: Ministry of Equality. Available online: https://violenciagenero.igualdad.gob.es/violenciaencifras/estudios/colecciones/macroencuesta-de-violencia-contra-la-mujer-2019/?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- Muafiah, Evi, Susanto Susanto, Idi Warsah, Desi Puspitasari, and Ayunda Riska Puspita. 2025. Implementation and problems of education based on gender equality, disability, and social inclusion at schools in Indonesia. International Journal of Sociology of Education 14: 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, Esther, Marta Soler, and Ramón Flecha. 2009. Opening schools to all (women): Efforts to overcome gender violence in Spain. British Journal of Sociology of Education 30: 207–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Sihyun, and Sin-Hyang Kim. 2023. A systematic review and meta-analysis of bystander intervention programs for intimate partner violence and sexual assault. Psychology of Violence 13: 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, Thi Thanh Giang. 2015. Using education-entertainment in breaking the silence about sexual violence against women in Vietnam. Asian Journal of Women’s Studies 21: 460–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puigvert, Lidia. 2016. Female university students respond to gender violence through Dialogic Feminist Gatherings. International and Multidisciplinary Journal of Social Sciences 5: 183–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puigvert, Lidia, Loraine Gelsthorpe, Marta Soler-Gallart, and Ramón Flecha. 2019. Girls’ perceptions of boys with violent attitudes and behaviours, and of sexual attraction. Palgrave Communications 5: 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roca, Esther, Giomar Merodio, Aitor Gomez, and Alfonso Rodriguez-Oramas. 2022. Egalitarian Dialogue Enriches Both Social Impact and Research Methodologies. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 21: 16094069221074442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues de Mello, Roseli, Marta Soler-Gallart, Fabiana M. Braga, and Laura Natividad-Sancho. 2021. Dialogic Feminist Gathering and the Prevention of Gender Violence in Girls with Intellectual Disabilities. Frontiers in Psychology 12: 662241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Eugenio, Laura, Lidia Puigvert, Oriol Ríos, and Rosa M. Cisneros. 2020. Communicative Daily Life Stories: Raising Awareness About the Link Between Desire and Violence. Qualitative Inquiry 26: 1003–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soler, Marta. 2015. Biographies of “Invisible” People Who Transform Their Lives and Enhance Social Transformations Through Dialogic Gatherings. Qualitative Inquiry 21: 839–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullman, Chelsea, Avni Amin, Angela Bourassa, Shikha Chandarana, Flávia Dutra, and Mary Ellsberg. 2025. Interventions to prevent violence against women and girls globally: A global systematic review of reviews to update the RESPECT women framework. BMJ Public Health 3: E001126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. 2015. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (A/RES/70/1). New York: United Nations. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/21252030%20Agenda%20for%20Sustainable%20Development%20web.pdf (accessed on 24 May 2024).

- United Nations General Assembly. 2022. Intensification of Efforts to Eliminate All Forms of Violence Against Women: Report of the Secretary-General (75/161). Available online: https://www.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/publications/2022/08/intensification-of-efforts-to-eliminate-all-forms-of-violence-against-women-report-of-the-secretary-general-2022 (accessed on 30 April 2024).

- United Nations Women. 2023. Final Synthesis Review of the Practice-Based Knowledge on the Prevention of Violence Against Women and Girls. Synthesis Review Series (Special Edition #2). United Nations Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women (UN Women). Available online: https://untf.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/publications/2023/11/learning-from-practice-final-synthesis-review-of-the-practice-based-knowledge-on-the-prevention-of-violence-against-women-and-girls (accessed on 30 April 2024).

- Valls, Rosa. 2014. Contributions for Eradicating Gender Violence: Female Empowerment and Egalitarian Dialogue in the Methodological Foundations of FACEPA Women’s Group. Qualitative Inquiry 20: 909–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, Candace, and Don H. Zimmerman. 1987. Doing gender. Gender and Society 1: 125–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. 2021. Violence Against Women Prevalence Estimates, 2018. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240022256 (accessed on 30 April 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.