Abstract

Opportunities for citizens to become prosumers have grown rapidly with renewable energy (RE) technologies reaching grid parity. The European Union’s ability to harness this potential depends on empowering energy citizens, fostering active engagement, and overcoming resistance to RE deployment. European energy law introduced “renewable self-consumers” and “active customers” with rights to consume, sell, store, and share RE, alongside rights for citizens collectively organised in energy communities. This article explores conditions for inclusive citizen engagement and empowerment within the RE system. Building on an ownership- and governance-oriented approach, we further develop the concept of energy citizenship, focusing on three elements: conditions for successful engagement, individual versus collective (financial) participation, and the role of public (co-)ownership in fostering inclusion. The analysis is supported by 82 semi-structured interviews, corroborating our theoretical lens. Findings show that participation, especially of vulnerable consumers, relies on an intact “engagement chain,” while energy communities remain an underused instrument for inclusion. Institutional environments enabling municipalities and public entities to act as pace-making (co-)owners are identified as key. Complementing the market and the State, civil society holds important potential to enhance engagement. Inspired by the 2017 European Pillar of Social Rights, we propose a corresponding “European Pillar of Energy Rights.”

1. Introduction

Renewable energy sources (RES) must achieve at least 63% share of the world energy system by 2040 to meet both the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and the Paris Agreement targets (UNFCCC 2015). As more and more renewable energy (RE) technologies reach grid parity, we observe a growing potential for citizens to become prosumers, that is, producers of the energy that they consume. Optimistic scenarios estimate, e.g., EU rooftop PV production at 680 TWh annually (Bódis et al. 2019). Moving past the current technical limit of 20 to 40% RES (EEA 2023) requires (i) a new energy system logic and architecture, particularly on the electricity distribution grid, but also (ii) measures to increase social acceptance of system changes and entice behavioural change to increase energy efficiency (EE) (IEA 2023), and (iii) a revised concept for the lawful control over and administration of (local) energy generation, supply and management (Martinot 2016; Seidl et al. 2019). Facilitating energy citizenship in the form of empowerment through engagement and (co-)ownership in renewables—individually or in energy communities (ECs)—is therefore one of the EU’s key policies to meet these challenges (European Commission 2019).

In a market historically dominated by large suppliers heavily invested in fossil fuels, citizens investing in RES have become a new category of actors. With energy provision opportunities, such as vertical supply-chain integration, going against the energy market logic of unbundling and competition, and a focus on the sustainable, affordable, and secure provision of services for the common good, a part of the required RE market expansion is expected to be carried by prosumership. However, the bulk of energy production is still owned by states or large multinational private companies, while the majority of citizens are not engaged (yet). A 2023 study estimates around two million citizens being active in 30 European countries, amounting to installed RE capacities ranging between 7.2 and 9.9 GW (Schwanitz et al. 2023). In light of the 592 GW of solar PV and 510 GW of wind required by 2030 to achieve the 69% share of renewable electricity modelled by the European Commission (European Commission 2022a), a vast financing gap (Pons-Seres de Brauwer and Cohen 2020) and massive problems of acceptance for new RE installations (Segreto et al. 2020), much more citizen engagement is needed. Moreover, existing citizen energy projects struggle with actor diversity and inclusion and largely retain homogeneous membership (Radtke and Ohlhorst 2021). Studies show that even cooperative RE projects—expected to be more inclusive and low-threshold—grapple with engaging a broad variety of people, leaving numerous groups either underrepresented if not excluded (Hanke et al. 2021).

Furthermore, the shift in incentive systems away from guaranteed feed-in tariffs (FITs) to market-based auction models is anticipated to tilt the playing field to the disadvantage of citizen-led grassroots projects, favouring large investor-led projects over energy communities (Grashof and Dröschel 2018; Dröschel et al. 2021; Toke 2015; Szabo 2020). Even in countries like Germany, where citizens had reached a share of about 40% in the ownership structure (trend:research 2011), this shift in incentive systems ushered in a decline to around 30% (trend:research 2020) over the last decade. Amongst others, sunk costs in cases of unsuccessful auction bids proved to be a challenge for ECs seeking risk capital from their constituency (Grashof 2019). Likewise, professional experience in bidding gives significant advantages to big companies (Hortaçsu and Puller 2008; Voss and Madlener 2017). In Germany, the share of ECs with successful bids in wind auctions decreased from about 8% (2010–2016) to 4% (2017) and 3% (2018) (Weiler et al. 2021). This observation correlates with the steep fall in the creation of new RE cooperatives in Germany from an all-time peak of 167 incorporations in 2011 to merely 29 in 2021 (Kahla et al. 2017; Wierling et al. 2018; DGRV 2013, 2021).

1.1. The Challenge

To facilitate energy citizenship, the recast of the Renewable Energy Directive (RED II) introduced “renewable self-consumers” having the right to consume, sell, or store RE generated on their premises alongside the guiding role model of the “active consumer” in the new Internal Electricity Market Directive (IEMD), both parts of the “Clean Energy for all Citizens Package” (CEP1, our emphasis). The new legal framework, alongside individual basic energy rights of European citizens, also introduces the above rights for citizens collectively organised in ECs with a distinct legal personality.2 At the same time, the successful implementation of the CEP will disrupt ownership patterns in electricity and thermal markets, including district heating. At least some fraction of the market share will be (re-)distributed amongst Energy Citizens, be it individually or organised collectively. This shift is a reorganisation of political control over energy systems, associated financial benefits, and resources essential for society. There is evidence that many incumbent generators and grid companies are aggressively resisting policies that open up energy markets to more decentralised and diverse ownership (Sovacool and Brisbois 2019; Brisbois 2019).

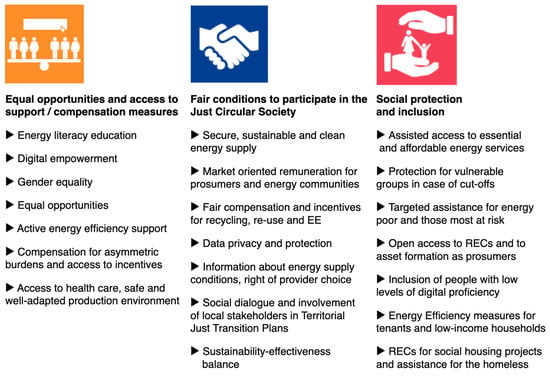

Moreover, factors beyond spatial proximity and equal opportunities affect citizens’ participation in energy projects. For example, communal energy actions often claim to be a strategy for tackling energy poverty, as also reflected in the programmatic title of the CEP. However, the word ‘community’ can be a cosmetic addition; these projects may not equally provide benefits or include social participation for everyone. Ignoring justice concerns can aggravate poverty and non-participation and entrench gender biases (Creamer et al. 2018; Berka and Creamer 2018; Jenkins 2019; van Bommel and Höffken 2021; Feenstra and Clancy 2020). Consequently, the European legislator postulates that impoverished households should be enabled to participate in and benefit from projects, rather than only those with higher socio-economic status. Prosumership, one of the foundations of energy citizenship, requires resources, knowledge, and motivation, and a certain willingness to take risks which are unevenly distributed across social groups (Hansen et al. 2022). Furthermore, presented in the framework of the EU Industrial Strategy, the European Commission has launched a new initiative to boost the social economy’s contribution to the green transition.3 Acknowledging the strong presence and pioneering role of social enterprises in climate change mitigation and adaptation, clean energy transition, circular economy, and related areas, this policy action directly contributes to developing the corresponding institutional environment of the “Proximity and Social Economy industrial ecosystem” (European Commission 2021a).

Notwithstanding, across the board, EU Member States’ social legislation creates a ‘welfare dilemma’ restraining social benefit recipients’ access to ownership of or income from RE assets as they conflict with eligibility for means-tested transfers (Lowitzsch and Hanke 2019), de facto disincentivising their participation in (co-)ownership of RE installations. Moreover, socio-cultural aspects of gender and race mediate benefits for particular social groups: On the one hand, the average 12.7% gender pay gap (Eurostat 2021) in the EU means that women have less income to invest as capital in RE; indeed, across Europe, women have invested significantly less in and own smaller shares of RE cooperatives than men (Fraune 2015). On the other hand, means for participation are often not as inclusive as they seem; many energy cooperatives recruit via informal networks and in similar social bubbles, leading to homogenous groups. Finally, energy poverty is shown to exacerbate existing gender inequalities, calling for empowerment and the reconfiguration of existing gender relations (Kumar 2018; Łapniewska 2019; Petrova and Simcock 2021). Finally, the energy transition contributes indirectly to energy poverty as retail prices increase along with system integration of RES (Śmiech et al. 2025).

1.2. Aim and Contribution

Against this background, pursuing a theoretical approach backed by interview data, this paper explores conditions for inclusive citizen engagement and empowerment within the RE system, concentrating on the following three research questions:

- Supposing that engaging citizens in RE is a complex and multifaceted process with strong interdependencies of its single steps, which is biassed against vulnerable consumers: What are barriers to, opportunities for, and key elements of inclusive engagement?

- To back our conceptual approach, refine the analysis of obstacles reported in the literature, and identify conducive conditions for inclusive participation/engagement, we analyze 82 semi-structured interviews conducted in eight European countries on energy citizenship. Against the background of this empirical interview data confirming said interdependencies, we can assume that low-income households (LIHs), if they could overcome the obstacles to engagement, would have the same or even a larger propensity to commit to EE, prosumership, and behavioural change than rich households.

- Taking into account the relationship between ownership, governance, and inclusive engagement and its embeddedness in institutional environments: What institutional and governance structures are best suited to support the different aspects of energy citizenship, and what role do energy communities have in this context?

- Collective prosumer action offers greater opportunities than individual engagement through economies of scale and diversity of sourcing. The collective action of prosumers allows for the aggregation of resources, leading to economies of scale in energy production and consumption, which can result in cost savings and increased efficiency (Horstink et al. 2020; Lavrijssen and Parra 2017). At the same time, the challenge of inclusive participation of underrepresented groups is not limited to commercially oriented initiatives but also pertains, e.g., to ECs. Against this background, the state as a citizenship-granting entity should not be acknowledged merely as the provider of network coverage but also as that of a guaranteed minimum supply indispensable for participation in our modern energy-based societies. Here, both state (co-)ownership and cooperation with private sector incumbents from the professional energy sector will have an important role to play. Therefore, we investigate how different ownership–governance settings relate to each other and which synergies are relevant for the success of meaningful inclusion, in particular with regard to ECs.

- In view of the governance trichotomy state/market/civil society and the functional context of different forms of energy ownership: What is the role of the public hand when fostering inclusive collective prosumership, and how can the state incentivise complementarities with individual private and collective civil society initiatives?

- As the CEP in various places calls on the MS to put into place concrete measures to facilitate inclusion, especially in the context of fighting energy poverty, we analyse how the new rules can respond to this policy objective. In the context of institutional environments and, again, with a focus on the deployment of ECs, we explore what policy recommendations can be made at the EU level both with regard to supporting individual citizens and ECs as organisations.

- We address these research questions by firstly presenting the regulatory background of the CEP and the status quo of citizens’ engagement (Section 2). Secondly, we provide theoretical foundations of energy citizenship and (co-)ownership under an institutional lens (Section 3). Thirdly, we present the interview data and the methods applied in the analysis (Section 4). We then discuss said barriers to and facilitatory factors for empowerment through engagement in light of the interview results (Section 5). Subsequently, we introduce a model of ownership vectors, linking their functional and their governance context to the interview results (Section 6). Our conclusions (Section 7) provide policy recommendations, again tailoring possible support measures to the institutional environments identified. As a more ambitious long-term measure, we propose a “European Pillar of Energy Rights” to be further explored and developed.

2. Regulatory Background of the CEP and the Status Quo of Citizen Engagement

2.1. Introducing Individual and Collective Energy Rights

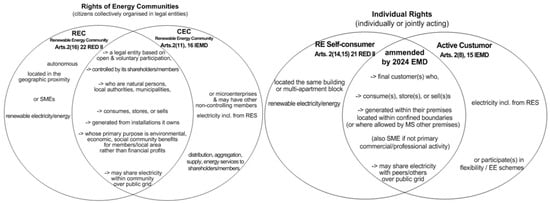

Launching the CEP, the European Commission postulated “consumer empowerment” as one of three mainstays of future consumer energy policy (see “Delivering a New Deal for Energy Consumers” (COM(2015) 339 final) and “On a New Energy Market Design” (COM(2015) 340 final)). In this context, one of the EC’s priorities was to put consumers “at the centre of the future energy system,” including the rights to self-consumption and to (co-)ownership in RE (COM(2015) 080 final). Correspondingly, at the European level, the CEP introduced basic energy rights to generate, self-consume, store, and sell electricity and energy both for individual citizens (including SMEs) and for citizens collectively organised in ECs with a separate and distinct legal personality. The legislator distinguishes between renewables, regulated by the RED II for the generation of both electricity and other forms of energy, and non-renewables, which cover electricity regulated in the IEMD only. In the former, “Renewables Self-Consumers” and “Renewable Energy Communities” (RECs) are introduced; in the latter, “Active Consumers” and “Citizen Energy Communities” (CECs), as shown in Figure 1. Members of both types of ECs have the privilege of sharing electricity (for RECs also other forms of energy) between members or shareholders, even when using the public grid; the updated Internal Electricity Market Directive (EU) 2024/1711 extends this privilege to individuals, independent of the establishment of an EC. According to Art. 15a ibid, MS shall “ensure that energy poor and vulnerable households can access energy sharing schemes”, that “energy sharing projects owned by public authorities make the shared electricity accessible to vulnerable or energy poor customers or citizens”, and that “[i]n doing so, MS will do their utmost to promote that the amount of this accessible energy is at least 10% on average of the energy shared.” In addition, it establishes the legal figure of the “Energy Sharing Organiser” with a corresponding business area, from which ECs can benefit both as providers and users of corresponding services.

Figure 1.

Basic energy rights of European Citizens; authors’ own elaboration.

2.2. Regulating Energy Communities

Concerning ECs, the differences between the RED II and IEMD pertain mainly to the governance model. CECs are open to all types of entities, while RECs limit their members or shareholders to physical persons, local authorities, including municipalities, and SMEs. Although Art 2 pt. 11 IEMD contains a similar definition to Art. 2 pt. 16 RED II, there are three key differences for CECs: (i) no requirement of geographic proximity for controlling shareholders as for RECs, (ii) the absence of the requisite for RECs to be autonomous, i.e., independent of single members or shareholders4, and (iii) a restriction for enterprises among the controlling shareholders or members of a CEC to small- and micro-sized firms. The latter restriction for CECs aims to establish a level playing field on which citizen-led initiatives can compete with incumbent commercial actors, as confirmed by recital (44) IEMD: “… decision-making powers within a citizen energy community should be limited to those members or shareholders that are not engaged in large scale commercial activity and for which the energy sector does not constitute a primary area of economic activity.” For RECs, this is ensured by the autonomy criterion (ii).

It is puzzling that no ancillary rights in the realm of energy production and consumption rights mentioned above have been enshrined in the CEP. While responsibility for the energy transition is often seen to be on the citizen in their function as consumer, stressing the need for behavioural changes, the question of citizens’ agency is rarely addressed, let alone that of empowerment (Lennon et al. 2019). This is in stark contrast to the attempt of incumbents in the fossil energy sector to shift responsibility away from themselves to individuals, as well-illustrated by the PR campaign of BP introducing a “carbon footprint calculator” in 2004 (Kaufmann 2020). Moreover, although energy citizenship requires collective efforts, access and participation may not be equally shared, and its benefits may not be actualised evenly. Indeed, as the shift from energy consumer to energy citizen relies on material innovation as well as consumers’ technical understanding and confidence in engaging with lower-carbon technologies, there is concern that the notion of energy citizenship may be exacerbating inequalities in socio-economic status, gender, and tenure (Radtke and Ohlhorst 2021). Therefore, participative rights and, of course, corresponding duties related to the energy transition should be accompanied by rights enabling citizens to make use of the former as a matter of enhancing their energy citizen capabilities (Sen 1995), as a matter of substantiating their rights.

3. Theory—Facilitating Empowerment Through Engagement and (Co-)Ownership

In this section, we introduce our understanding of five key concepts pivotal for the analysis of both the barriers in the engagement process of underrepresented groups in the energy transition and for support measures under what we call an ownership–governance-oriented approach. We first present a short overview of how we understand energy citizenship, and then reflect on how the potential of making use of such rights is impacted by an individual’s capabilities (or their absence thereof) and the institutional area they are active in. Subsequently, we back our ownership–governance-oriented approach with an overview of empirical survey data showing the crucial function of (co-)ownership in RE for energy citizenship. We then emphasise the interrelatedness of obstacles for individuals, stressing in particular how this phenomenon plays out negatively for the energy-poor. Against this background, we conclude that facilitating energy citizenship (e.g., by policy measures, private initiatives, etc.) needs to be embedded in the respective institutional environment if it is to be effective.

3.1. Energy Citizenship

The scope of energy citizenship is developed against the historical development of the concept. An important point of reference is Marshall’s (1950) description of citizenship as entailing social responsibilities the state has towards its members “from [granting] the right to a modicum of economic welfare and security to the right to share to the full in the social heritage and to live the life of a civilized being according to the standards prevailing in the society”. Devine-Wright (2007) considers energy citizenship as the social necessity of public engagement and participation, with a public seen as active stakeholders in the energy system, defined by notions of equitable rights and responsibilities. The expansion of the concept from the mere provision of general services towards political, economic, and social participation rights is reflected in modern human and fundamental rights as enshrined, for example, in the European Charter of Fundamental Rights. Such fundamental rights also embrace obligations (Hohfeld 1917); for citizens, these obligations are mostly of a negative kind, such as the obligation to tolerate others (as with fundamental civil rights), but for governments, they also include ensuring that those rights can, indeed, be exercised. Examples of the latter include the right to legal defence in penal law, the protection of religious freedom, bodily integrity, and abortion clinics; as political rights, those to vote, assemble, and demonstrate; as social rights, those to financial support for media pluralism and access to adequate health care and quality education. Under international law, Art. 2 of the 1966 UN International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR 1966) clearly stipulates state responsibilities with respect to creating conditions under which such rights may be enjoyed. In view of the principle of open access and voluntary participation in ECs, for example, this requires a proper institutional environment and opportunities for participatory/inclusive ownership–governance. This approach directly builds on the European Charter of Fundamental Rights to formulate energy citizens’ rights.

In its original understanding, “citizenship” refers to the legal rights, responsibilities, and privileges of a person vis-a-vis the state. The energy system notwithstanding, the state as a citizenship-granting entity is merely acknowledged, if at all, as the provider of network coverage, hence the highly regulated ownership of the public grid. However, as citizenship in general follows from arrangements of constitutional law on citizenship, often combined with nationality and, in liberal democracies, of course, based on the assumption of basic freedoms and inalienable natural rights, these require operationalisation (Thomassen 2007). Therefore, applied to energy citizenship, it should be acknowledged as a socio-legal concept that surpasses mere grid access and includes a minimum supply guaranteed by the state. Furthermore, the concept of citizenship in the energy context should imply an active engagement in the energy system and awareness regarding energy issues. A review of the state-of-the-art literature reveals several alternative overarching frameworks on which the term energy citizenship might be based. These include participation and engagement, collective action and responsibility, social acceptance in inclusive and transparent energy decision-making, political and civic activity, empowerment and gender equality, and energy justice. When embedding energy citizenship in the functional context of operationalisation of fundamental energy rights that ensure the actual exercise of these rights by the individual citizen, we can identify three institutional environments, each with a different specific function as regards energy citizenship, as depicted in Figure 2. Each environment, on which there is more later, accommodates such citizenship through its particular mode of channelling individual and collective behaviour, upon distinct sets of fundamental rights, respectively, (a) underpinning private ownership in the market, (b) equal access to public/state facilities, and (c) collective/civil self-regulatory capacity.

Figure 2.

Ensuring the exercise of fundamental energy rights in the functional context; authors’ own elaboration.

One of the most prevalent approaches to defining energy citizenship is through the active involvement and democratic engagement of individuals and communities within the energy system to meet decarbonisation targets for the sake of a sustainable energy transition (Mendes et al. 2020; Coy et al. 2021; Mang-Benza 2021; Caramizaru and Uihlein 2020; Nakamura 2017; Mori and Tasaki 2019; Parkins et al. 2018). Engagement is mainly observed at two particular levels: the individual level, where the citizen focuses on prosumership or energy conservation, and the collective level, where the citizen engages in local, national, or international activities related to ECs (Radtke 2014). Similarly, to the rights of the CEP, Moncecchi et al. (2020) describe energy citizenship as participation through ECs allowing citizens to “produce, consume and share energy within the community and share energy within the community but also to actively participate in the energy market”. In the context of participatory processes, this includes actors and regulatory institutions involved in the governance of the energy sector (Sanz-Hernández 2019; Walker et al. 2016). These participatory processes provide hybrid relationships between people and energy technologies, as in socio-technical systems, and the different roles people can take, such as “users, consumers, protesters, supporters and prosumers” (Ryghaug et al. 2018).

3.2. Empirical Evidence on the Positive Effects of (Co-)Ownership from Germany

Broad engagement is necessary for the success of the energy transition, as EE typically requires behavioural change, and empirical studies have shown important behavioural effects of (co-)ownership in RE. Two large surveys among German households (Roth et al. 2018, 2021, 2023) provide evidence that fully fledged prosumership, i.e., (co-)ownership in RE with the option either to self-consume or to sell to third parties, goes hand in hand not only with an increased propensity for demand flexibility and EE behaviour, but also for investments in EE. These findings are particularly clear for PV installations where engagement is usually direct and within proximity of households, which, contrary to the assumption that they will not include LIHs, also holds true for poor citizens provided that they have the opportunity to engage (O’Shaughnessy et al. 2021). At the same time, income is positively correlated with the purchase of EE technologies, while it is negatively related to engagement in EE behaviours aimed at reducing energy demand (Radtke et al. 2022; Umit et al. 2019).

Moreover, the findings from Germany show that LIHs (i) have a larger propensity for behavioural changes than richer households (and an equal if not greater propensity compared to middle-income households) and (ii) are also inclined to invest in RE and EE if they have the possibilities to do so (but due to the mentioned “welfare dilemma” and a lack of savings they cannot realise this potential). The potential to mitigate rebound effects and increase EE is thus even larger with this group than with middle- and upper-class households (although LIHs’ underconsumption is often mistaken for rebound (Hanke et al. 2023)). These findings are corroborated by a 2023 survey among German households (Magalhães et al. 2024) focusing on both individual and collective investments in EE, which stressed the engagement potential of LIHs if they are supplied with adequate information and financial assistance and supported in the process. Behaviour-related approaches to increase demand-side management should therefore include LIHs and other underrepresented groups, and inclusion is probably a prerequisite for the broad roll-out of both EE and RE production.

Positive effects of the engagement of citizens as (co-)owners and prosumers also extend to the realm of ECs. While ECs, of course, may also have homogenous constituencies, heterogeneity in membership is key to optimising the economies of ECs when matching the diverse RE production profiles with the consumption profiles of the different members (Belmar et al. 2023; Yang et al. 2024). Successful ECs also bring together participants with different motivations, resources, and backgrounds, ranging from low-income households to small- and medium-sized enterprises and public institutions. This diversity is a strength, promoting load complementarity, cooperation, and resilience (Lowitzsch et al. 2025), but also adds another layer of complexity.

In summary, tapping into the enormous potential, in particular with regard to the necessary decarbonisation of our energy systems, requires the involvement of energy citizens not engaged yet—that is, the vast majority of actors. Finally, it is estimated that as many as 83% of the EU’s households, i.e., 187 mln., could potentially become energy citizens contributing to RE production, demand flexibility, and/or energy storage, of which 113 mln. have the potential to produce RE (Kampman et al. 2016).

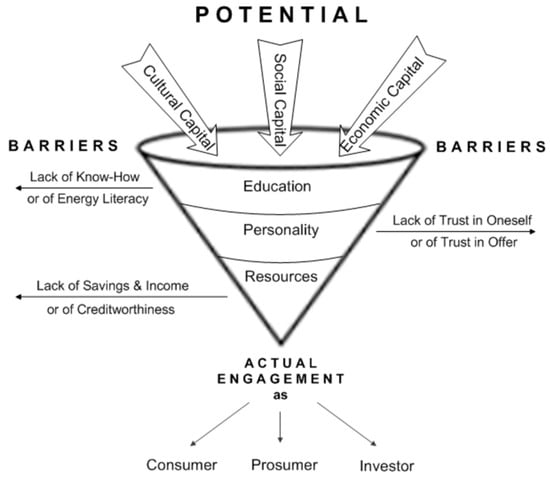

3.3. Capabilities and Their Link to Institutional Environments

Building on the notion that citizens can engage with the energy system in multiple ways, the conditions for creating individual pathways of energy citizenship are a key element in understanding barriers to engagement (Figure 3). Citizens have different forms of economic, social, and cultural capital, such as income, education, and networks, which determine their resources and opportunities for engagement (Bourdieu 1986). Following Bourdieu, the nexus between energy and civic engagement appears complex as individual pathways to energy citizenship depend on socio-economic status and socio-cultural relations. Economic capital enables citizens to invest in renewable energy plants, ECs, and corresponding investment funds. Social and cultural capital influence whether ‘I’ have heard of opportunities for engagement (e.g., social bubble) or overcome existing barriers to engagement (e.g., language). As ECs recruit new members, often via networks, citizens with high social capital are more likely to be asked to join the EC than citizens belonging to marginalised groups disadvantaged by language or other barriers (Campos and Marín-González 2020). Depending on individual resources and capabilities, citizens are more or less likely to assume different roles, spanning from mere consumers to prosumers or co-owners. Each citizen can take on different roles and therefore acts as an energy citizen in different areas. The output of these roles is actions that are not exclusively limited to one sphere but are interrelated. As the individual actions of each citizen are strongly related to that person’s capabilities, it is crucial to understand what barriers prevent citizens from taking on more roles in the energy system. The interplay between these capabilities and engagement and—in their absence—their possible role as barriers to engagement are summarised in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Conditions for individual engagement and their relation to capabilities; authors’ own elaboration.

Correspondingly, citizens’ radius of action may be limited in the three above-mentioned institutional environments. While “market” and “state” are well-established institutional environments in the energy world, that of “civil society” is emerging in the context of the CEP, acknowledging citizens’ and communities’ rights to engage directly in the energy sector. This action arena is reflected by the current political support of the social economy with regard to “the social economy business case for the green transition”5 as social enterprises have been present for decades, delivering innovative green solutions, for example, in the circular economy. In light of the above-described large differences pertaining to capabilities, this institutional environment is predestined to assist/support/compensate those who are facing barriers to engagement for various reasons. In practice, however, concrete examples of such approaches remain scarce; we refer to them where appropriate.

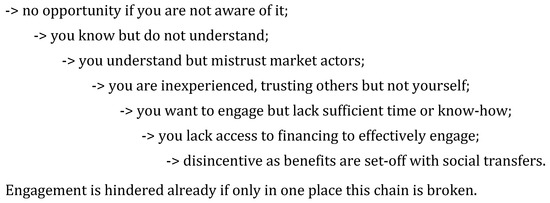

3.4. Interdependency of Obstacles—“The Engagement Chain”

To put the individual at the centre of analysis requires going beyond a market-based approach and an understanding of citizens as mere energy consumers. One needs to reach past the concept of “consuming”, employing a holistic human-centred approach, postulating a “homo ecologicus” (e.g., Huntjens and Kemp 2021; Dryzek 1996; Bosselmann 2004; Becker 2006; Cecchi 2013). Applying an intersectional approach, three dimensions need to be considered: (i) individual characteristics and living contexts; (ii) systemic variables and discriminating systems (e.g., the energy and housing market); and (iii) the political dimension and its rooted social policies (Hanke and Lowitzsch 2020). Each of these three dimensions brings specific hampering factors, determining the passivity of energy citizens. We observe that, while provision of more choices and information (a key pillar in EU consumer engagement strategy) is a necessary condition for consumer engagement, it does not suffice on its own (Lowitzsch and Hanke 2019). A rational approach solely relying on this logic incentivises agency but stays ignorant of the bounds of rationality, and with that, of the living reality of the majority of energy consumers. Engaging passive citizens depends on a good understanding of motives, restrictions, and derived incentives, all of which are shaped by local context. Lowitzsch and Hanke (2019) provide an overview of negative effects on economic decision-making and their relations. They show that behavioural effects of individual problems (often but not necessarily rooted in scarcity) of involvement, commitment, decision-making, etc., are interdependent and reinforce themselves reciprocally. They form an “Engagement Chain” (Figure 4), with engagement being hindered already if the chain is broken in only one place.

Figure 4.

The engagement chain; own elaboration.

These dynamics play a particular role for engagement in participation models as they determine to a large extent whether these models are perceived as an opportunity to improve households’ situation or are obstructed by the effect of tunnelling. In this sense, barriers to engagement are more prevalent in certain social milieus, like the precarious milieu (people with low household income and low education level) or the conservative-civic milieu (in which women take over more stereotypical roles like childcare duties). Multiple obstacles (financial, language, access to information, etc.) cumulate, amounting, when combined with systemic barriers, to almost insurmountable impediments that can only be overcome through combined and comprehensive policy solutions. Measures to address individual obstacles and systemic barriers therefore need to go hand in hand.

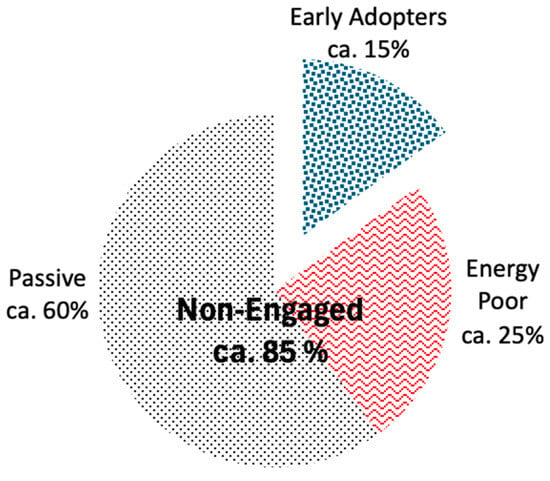

3.5. Implications for Inclusion and the Energy Poor

The extent to which the energy union will be able to tap into the potential of its energy citizenry will largely depend, on the one hand, on empowerment and active engagement, and on the other, on overcoming scepticism and, in particular, in the wind power sector, resistance to RE deployment. At the same time, a large majority of citizens are still excluded from any active participation, be it regarding prosumership, EE, or the governance of energy systems. Until now, it is mostly a small minority of citizens, i.e., early technology adopters with adequate financial means or environmental advocates, that actively participate in these areas (Łapniewska 2019; Yildiz et al. 2015). Policymakers have been struggling for a long time to raise awareness and activate the European citizenry; however, with very limited success, as the following findings illustrate. In 2016 an EU commissioned study found that, across the EU countries, on average, only 14% of energy consumers actively switched energy supply tariffs over the last three years (European Commission et al. 2016); according to diffusion of innovation theory, the combined share of innovators and early adopters of emerging technologies (including, e.g., prosumption) is estimated to be in the same bracket of around 15% (Rogers 1962; Kotilainen and Saari 2018). These sources are a strong indication that the number of already active energy citizens is very low and can be estimated in the range between 10 and 15% of the overall population. A contrario, it can be concluded that as much as 85 to 90% of the population is probably not engaging with the energy systems and can therefore be considered passive. Furthermore, it is safe to make this assumption for the estimated 50 to 125 million people—between 10 and 25% of the EU’s population—that are at risk of energy poverty, living in a situation marked by consumption restriction and passivity (Bertram and Primova 2018). But it is also likely the case for the remaining 60–75% (depending on the actual number of energy-poor individuals) ordinary citizens who remain passive. Figure 5 summarises the potential for engagement. These estimates are corroborated by national survey data, e.g., from Germany, dubbing participation in community energy as “elite clubs” (Radtke and Ohlhorst 2021; Bedggood et al. 2023).

Figure 5.

Estimates of engaged vs. non-engaged energy citizens; authors’ own elaboration.

Scarcity in particular leads to focusing on short-term and poverty-related issues, and the resulting “tunnelling” suppresses long-term thinking simply because the scarcity-induced mind is preoccupied with present challenges (Lowitzsch and Hanke 2019). Therefore, long-term investments in RE and EE will typically lie outside the individual’s scope of action or imagination. These negative effects, in turn, are reinforced by ’ego-depletion’, translating into less capacity for self-discipline and increased tendencies for short-sighted behaviour and decision making (George 2021). A comprehensive policy approach to facilitate energy citizenship and to promote (co-)ownership in RE and make investments in EE available to LIHs must therefore take into account these “soft” factors when designing specific instruments and measures (Anand and Lea 2011; Schilbach et al. 2016). A general vulnerability context further prohibits proactive participation of energy consumers in the energy market. Poverty dynamics impact cognitive processes and lead to short-sighted and poor economic decision-making. Poverty limits consideration of alternative options, ignores possible long-term benefits, depletes the willpower necessary to adhere to a long-term objective and in general makes it more difficult to choose between options or to calculate trade-offs. It narrows the time horizon and alters perceptions of risk. All these factors impair financial commitment to long-term investments in RE. Furthermore, cognitive capacity is a scarce resource necessary to understand the use of new technologies (e.g., smart meters) and their adaptation to local circumstances. The engagement of vulnerable households, among which are LIHs and women, to become active energy consumers, is a niche field in energy literature, with most work linked to energy poverty. Moving beyond this field, Hanke and Lowitzsch started early in exploring innovative ways to empower the most vulnerable to enable them to become prosumers (Lowitzsch and Hanke 2019), postulating a “Renewables Asset Formation Agenda for Low-Income Households”. The RED II, the IEMD, the Just Transition Fund, and the European Green Deal postulate the inclusion of vulnerable consumers in RECs as a form of consumer empowerment and a means to fight energy poverty, but remain silent of how to do so concretely.

3.6. Institutional Embeddedness—The Governance Trichotomy

To facilitate that energy citizenship rights can, indeed, be exercised, both by individuals and, perhaps more importantly, through collective prosumership within ECs, a proper institutional environment is required to provide a socio-legal underpinning for participatory/inclusive ownership—governance. Either way, the basic rules that underpin powers, rights, and obligations of energy citizens need to fit both desired interactions between them, and with other actors in the energy sector, such as energy companies, facilitators, grid operators, and relevant public bodies, upon rules that shape their powers, rights, and obligations. Together, these underpinning rules shape a socio-legal environment that creates institutional opportunities and likewise poses barriers conducive to subsequent patterns of collective behaviour as modes of governance that foster achieving an inclusive energy transition. Following the analysis of such modes of governance as institutional environments by Heldeweg and Saintier (2020), we argue that the imagery of active energy consumers and energy citizens perpetuates the traditional governance dichotomy of state versus market, as opposing institutional environments, and thus ignores the need to intrinsically accommodate the desired role of ECs and their members.

It is therefore necessary to advance the perspective of a governance trichotomy by including a third institutional environment, that of civil society networks, applied to the energy sector as that of ECs. This socio-legal environment is shaped by distinct key values, justice conceptualizations, and actor and relationship types, shaping the opportunities within an EC and vis-à-vis other actors, such as companies, facilitators, and public entities. An important difference from other energy market actors is that while market liberalisation required them to unbundle services, ECs are permitted vertical integration to facilitate their role in RE production in proximity to consumption and to compensate for their structural disadvantage (Jasiak 2018). Such a third institutional environment, next to that of the state and the market, allows us to formally embed ECs, as particular types of governance structures, within an accommodating socio-legal institutional environment—in line with Hirst’s associative democracy principles (Hirst 1994; Ostrom 2010). This environment reflects the relations within the social groups engaged, recognises their strengths and vulnerabilities as individuals and collectives, and empowers and facilitates a decentralised, democratised, and inclusive energy transition. Table 1 presents how ideal-type institutional environments come with favouring distinct key interests, relationship types, key actors, and the corresponding key owners.

Table 1.

Key characteristics of the institutional environments under the governance trichotomy; adapted from (Heldeweg 2017).

For energy citizenship to flourish, especially (but not only) in ECs, the broader participative and inclusive demands of “energy democracy” need to be enshrined in a civil society institutional environment. This implies equal and equitable access to an adequate supply of affordable green energy and democratic agenda-setting in production facilities. Again, the key question is what participation models relevant to the energy value chain, as part of a given institutional environment, are (more) successful in fostering the energy transition and, in particular, the decarbonization, while placing energy citizenship at its core. This functional view of institutional environments connects to ownership–governance structures of participation models that carry energy citizenship. Concerning governance and the respective (dominant) owner, other than ECs in the environment of civil networks, this comprises two environments, i.e., the state in the environment of the constitutional order and individual private parties in the environment of competitive markets. In each institutional environment, the key owner(s) act(s) under a different set of rules with different roles regarding energy citizenship, resulting from the functional context of the corresponding institutional environment (Heldeweg 2017). Better understanding these institutional environments and their functions without extending into a meta-governance discourse (Gjaltema et al. 2020) involves an analysis that looks at these models through the lens of how they mediate basic energy citizens’ rights, from the level of individual physical persons to the level of formalised energy networks, e.g., ECs. In this context, different “key owners” mediate different facets of rights and obligations that energy citizenship entails. The following Section 4 provides the details of our interview data and the methods applied. Section 5 discusses the results and reflects the afore-mentioned concepts against the data to facilitate the discussion on which institutional and governance structures are best suited to support energy citizenship in Section 6.

4. Materials and Methods

This paper uses a multi-method approach to conceptualise energy citizenship in light of the research questions posed, drawing on scientific literature and policy review, a regulatory screening, an empirical analysis in the form of semi-structured interviews (see Section 4.1 and Section 4.2), and expert discussion rounds. With respect to the latter, the collective brainstorm consisted of bi-weekly online meetings between the authors during the writing process. A limitation of our approach was that, regarding the interviews, we did not include citizens’ perspectives but focused on experts from their respective fields.

4.1. Semi-Structured Interviews and Sampling of Experts

To examine stakeholder perspectives and experiences relevant to energy citizenship in the energy transition, we conducted expert interviews between January and April 2022. The analysis draws on 82 semi-structured in-depth interviews with experts from eight countries, namely, Austria, Bulgaria, Germany, Greece, Italy, Norway, Switzerland, and Turkey. Expert interviews were chosen as a methodological approach to capture stakeholder perspectives and experiences relevant to energy citizenship in the energy transition. These interviews were conducted in the context of the Horizon 2020 project DIALOGUES6 in its consortium member countries.

The overall aim of the interviews was to explore the current understanding of how citizens can engage in the energy transition, why citizens do not engage, opportunities and barriers for inclusive participation, and the institutional embeddedness of energy citizenship. In each country, a purposive sampling strategy was employed to select interviewees with demonstrated knowledge of, and involvement in, national or local energy transition processes. Purposive sampling enables the identification and selection of individuals who are especially knowledgeable about, or experienced with, a phenomenon of interest (Kalu 2019; Palinkas et al. 2015). The sample comprised both certified experts—such as professionals holding formal roles in policy, industry, or research—and non-certified experts, including activists and practitioners with relevant experiential knowledge.

Experts were drawn from three main stakeholder groups: (i) public actors, including energy policymakers at local, regional, and national levels, as well as executives or officers in municipal or mayoral offices; (ii) energy suppliers, encompassing both public and private utility companies; and (iii) citizen organisations, such as non-governmental organisations, associations, activist groups, members of professional chambers, academics, and representatives of private companies. The diversity of perspectives enabled a comprehensive assessment of how these different actors understand and engage with the energy transition, and supported the synthesis of empirically grounded pathways toward energy citizenship. Further details on the composition of the sample are provided in Appendix A.

Purposeful sampling is widely used in expert interviews, but has limitations that should be explicitly acknowledged and addressed. The main issues can be grouped into sampling validity, bias, transparency, and generalisability: Firstly, the intentional selection of participants introduces the potential for selection bias, as inclusion is influenced by researcher judgement and access constraints (Palinkas et al. 2015). Secondly, the definition of “expertise” is inherently context-dependent and may privilege certain forms of institutional or professional knowledge over experiential perspectives (Maxwell 2013). To address this, we applied explicit inclusion criteria and incorporated multiple forms of expertise, including both formally accredited professionals and practitioners or activists with experiential knowledge.

As with purposive expert samples more generally, the findings are not statistically generalisable; instead, they support analytical generalisation by contributing to theory development and comparative interpretation (Yin 2018). The sampling process may also be subject to influence from gatekeeping dynamics and uneven access to high-level or marginalised actors, which may result in the shaping of the range of perspectives represented (Petintseva et al. 2020). To mitigate the afore-mentioned risks, a selection of experts from diverse sectors and institutional positions was made, and multiple recruitment channels were utilised wherever possible. Although a limitation of this approach is possible selection bias, the objective of the interviews was not the randomness of the sample but instead an explorative investigation with a sizable expert group that was, above all, representative of the various stakeholder groups. Finally, given the interpretive role of the researchers in sampling decisions, transparency was prioritised through detailed documentation of selection criteria and sample composition, provided in the main text.

Experts in each country were selected based on gender and expertise criteria, representing public actors, energy suppliers, and citizen organisations. While some experts focus on economic and political dimensions, others emphasise social justice and inclusion, providing a comprehensive understanding of the opportunities, challenges, and processes shaping energy transition in different national contexts. The selection of experts and the spheres they represented was congruent with the previously identified institutional environments under the governance trichotomy in Section 3.6. with a focus on experts’ knowledge concerning pathways to energy citizenship. The interviews with experts from the stakeholders in local energy systems were analysed to assess the reasons for local citizens’ engagement (or non-engagement) with the energy transition and to capture how energy citizenship is framed. The focus lay on current progress, the challenges involved, and which strata of society are included or excluded in corresponding discussions in each country. Following a dedicated guideline, the in-depth interviews with a duration of 45–90 min were conducted between January and April 2022. A total of 82 interviews were carried out in partner countries, with 42% of the interviewed experts from civil society, 27% from the public, and 26% from the private sector.

4.2. Operationalisation of Research Questions and of Result Analysis

The research questions were operationalized by asking for experts’ perspectives on energy citizenship in three interrelated knowledge dimensions (Bogner and Menz 2009): technical knowledge, concerning the experts’ roles and responsibilities in supporting the energy transition; process knowledge, relating to organisational structures, actor interactions, and social dynamics; and interpretative knowledge, focusing on challenges to citizen participation and inclusivity, including gender, socio-economic background, and age. Experts were asked to provide insights on strategies to enhance engagement, with particular attention to reaching underrepresented or hard-to-reach segments of society. Regarding technical knowledge, experts from various countries and roles provided insights into the conceptualisation and implementation of the energy transition and energy citizenship in diverse organisational and national contexts. Regarding the possession of process knowledge, interviewees reported experience at multiple levels, including municipal, regional, national, and international. Initiatives that were deemed successful were identified as those that exhibited extensive participation, the presence of ECs and cooperatives, and the active endorsement of local governments. Conversely, political and legislative barriers, frequent regulatory changes, bureaucratic hurdles, limited public awareness, and insufficient inclusivity—particularly regarding gender, migration, and socio-economic or cultural representation—were identified as key obstacles. Experts emphasised that social change is primarily driven by collaboration and knowledge dissemination, underscoring the importance of energy communities. In the context of interpretative knowledge, inclusivity emerged as the pivotal dimension of energy citizenship, encompassing the concepts of fair participation, gender equality, and social justice. Furthermore, experts indicated that economic incentives, financial considerations, environmental concerns, and health-related factors strongly influence citizens’ engagement in the energy transition.

The results were checked and analysed through triangulation (Denzin 1970), with the transcripts subsequently independently double-coded according to (O’Connor and Joffe 2020). A coding framework with themes and subthemes was introduced to extrapolate the data from the interviews to the research questions. Moreover, we looked for patterns, contrasts, and relationships across participants and countries, and we used illustrative quotes to ground interpretations in participants’ own words. While qualitative results are not statistically generalizable, they can support analytical or theoretical generalisation by linking patterns to broader concepts, frameworks, or previous studies.

5. Results

5.1. Opportunities for Broader Engagement

Based on the data from the expert interviews, we find a wide range of possibilities for civic engagement from the local to the regional and the national levels, from a political to an economic sphere, for consumers and producers. A total of 65% of the experts pointed to the multitude of crises, including climate change, the aftermath of COVID, and the current effects of the Ukraine war as catalysts for RE but also for social segregation and injustice. As a result, the advantages of investing in RE technologies and EE measures have increased, yet this window of opportunity has not been fully exploited. While policies have been implemented to incentivise a reduction in energy consumption, structural empowerment for citizens to invest in RE is missing (INBG1, INAT2, and INDE9).

As mentioned in the theoretical section, citizens may engage in the energy system on an individual level or collectively, in energy cooperatives, communities, or other types of initiatives. At the individual level, the concept of prosumership is well researched and was mentioned by 66% of the experts as a facet of energy citizenship. However, the CEO of a digital platform for citizen RE projects in Germany stated that prosumership is often associated with the classic image of a (male) homeowner installing a solar power plant on his roof and investing in a smart home with battery storage and electric cars (INDE1). At the same time, the experts saw opportunities for activating more people as energy citizens: Private investments by citizens in RE are needed to reach the climate targets—this was mentioned by 95% of the experts. The experts mentioned social justice (78%) and sustainability (67%) as pivotal aspects of engagement. Social justice includes support for energy-poor households and the empowerment of women and young people from diverse backgrounds to benefit from the energy transition. A total of 70% of the experts agreed that women and people with a migrant background, low education, or low income are commonly underrepresented in the energy transition or have limited possibilities for action.

On the consumption side, investment in efficient applications and sustainable products is an important aspect of energy citizenship. Both prosuming and sustainable consumption depend on knowledge about sustainable energy options and investment capital, e.g., to buy a solar panel or efficient applications. Experts in Greece stressed the need for people to have the financial capacity to benefit from the funding of tge Energy Saving Program “Exikonomo” to make energy improvements in their homes (INGR6, INGR10). For RE production, land or home ownership is reported to be a prerequisite (INNO2, INNO10, INDE6). While financial benefits in the long-term are affirmed, entry costs of sustainable technologies are considered high and not attainable for LIHs. Before households become energy poor, they are often ‘just’ poor, meaning they are under pressure due to social and economic issues, leaving them with little capacity to proactively think and act upon the energy system. At the collective level, ECs offer citizens a more affordable entry point for RE production and a joint search for local transformation pathways (INIT8, INTR4, INGR6). The installation costs for energy plants are shared by the members of the EC, and neighbours can benefit from lower energy consumption costs via energy sharing.

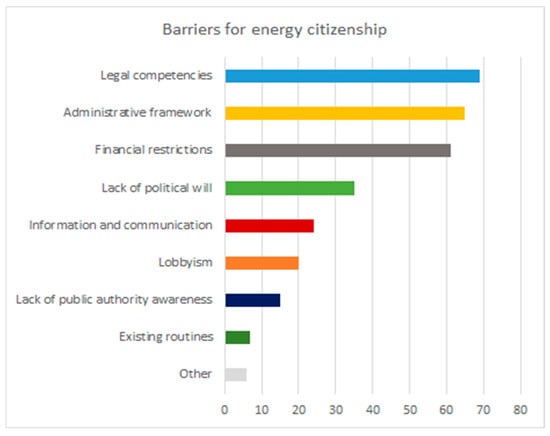

5.2. Barriers to Broader Engagement

Additional formats for citizen engagement in the energy system may be campaigns, networks, initiatives, research projects, and the workspace. However, at the individual and structural level, a variety of barriers to engagement exist. According to the interviews, these consist primarily of a lack of legal competency, the complexity of the administrative framework, a lack of political will, lobbyism, and a lack of public awareness. A total of 84% of the experts agreed that a multi-level governance system administering energy citizenship is too complex. Municipalities often do not have the legal power to encourage local RE production by citizens because it is regulated at a higher level (INBG2, INAT8). This assessment is linked to complicated administrative processes for energy citizen projects within the existing legal framework, e.g., the issue of tardy commissioning of citizen-owned power plants to the operating grid (INBG9, INDE10).

At the individual and to some extent also at the collective level, the financial situation of citizens is identified as a major barrier, because LIHs will not dispose of resources for investments, even if they lead to financial returns or cost savings in the long run. A total of 43% of the experts observed a lack of political willingness to incentivise the engagement of citizens in the energy system. Large energy projects like wind and solar parks are being realised by external investors in many regions of Europe without proper consultation and involvement of the local population (Devine-Wright 2011). Moreover, lobbying by the fossil energy industry leads to power struggles at the national and the local levels, such as the leasing of public land to private actors installing RE plants without citizen participation. In addition, 18% of the experts reported that public authorities and politicians are not aware of the benefits of engaging more citizens in the energy transition. Finally, barriers like social routines, cultural aspects, lack of time, and so on were reported in particular on the consumption side. On the other hand, the experts saw opportunities for activating more people as energy citizens: Private investments by citizens in RE are needed to reach the climate targets—this was mentioned by 95% of the experts. The experts mentioned social justice (78%) and sustainability (67%) as pivotal aspects of engagement. Social justice includes support for energy-poor households and the empowerment of women and young people from diverse backgrounds to ensure they benefit from the energy transition. A total of 70% of the experts agreed that women and people with a migrant background, low education, or low income are commonly underrepresented in the energy transition or have limited possibilities for action.

Even though it is often claimed that ECs (esp. cooperatives) will lead to greater social engagement in the energy system, they are not open and accessible per se to all citizens. Social networks play a crucial role in the recruitment of new members. An expert from an NGO for cultural diversity in sustainability transformation argued that, if certain social groups are never specifically targeted either through their language or at their places of cultural identity, they will not know about local ongoing ECs or will not feel welcome (INDE7). An interviewed gender expert added that the reasons for women not engaging in the energy system are manifold: from male dominance in technical-related issues from childhood onwards to the issue of unequal distribution of care-related work and the gender pay gap (INTR9). A recent study by Karl and Bode (2022) showed that women themselves state time restrictions due to care work as the number one barrier to joining energy projects. ECs must be specifically designed to engage underrepresented citizens and support them in overcoming engagement barriers such as cultural and linguistic burdens. While in theory ECs could contribute to the inclusive participation of citizens, they often lack the resources to develop appropriate measures to address people outside their social group. All interviewed experts pointed out the significant role of local authorities and municipalities in educating citizens about the energy transition and collaboratively and creatively working on issues of social justice, diversity, and inclusivity. Figure 6 provides an overview of the assessment of barriers by the interviewees.

Figure 6.

Barriers for energy citizenship; authors’ own elaboration.

The primary purpose of ECs was defined for both RECs and CECs as identical at the European level, “to provide environmental, economic or social community benefits for its members or the local areas where it operates rather than financial profits” (see Figure 1). This highlights the importance of tackling the barriers to energy citizenship beyond mere financial participation to enable inclusive citizen engagement. Referring to the tripartite institutional embeddedness of energy rights, one of the results of the interviews is that these environments seemingly are kept separate and distinct. While the market in principle enables citizens to become prosumers, it is biassed towards high-income groups with high education levels and land or home ownership. It is not able to efficiently integrate broader strata of society, for example, tenants or LIHs. At the same time the state in most EU countries fails to provide appropriate incentives for underrepresented groups and/or a legal framework containing preferential schemes that would allow more civic participation, if only by prosumership; rare exceptions are France, where social housing projects by law qualify as RECs (see also Section 7.3), and Germany, with its tenant energy programme that was suffering from being complicated (Inês et al. 2020) and failing to reach LIHs until it was overhauled (Bundesumweltministeriums 2023). Thus, despite corresponding postulates in both RED II (Art. 22 para 4 lit f) and IEMD (recitals 43 and 60 in connection with Art. 28)—which, however, do not contain any relevant measures (be they binding or not) or instructions of how to achieve inclusion—overall, the state is not addressing these issues either. It seems that the engagement challenge is left for civil society, a realm where cultural differences and social routines highly affect the inclusiveness of collective RE initiatives. All interviewed experts agree that there is a need for adjustment to activate more citizens in the energy transition, and that the state, as a public entity, has an outstanding responsibility to develop an institutional setting that would facilitate inclusive energy citizenship.

Last but not least, considering the identified barriers, we observe an interdependence both between the various individual obstacles and vis-à-vis structural barriers to energy citizenship, as described in most interviews (e.g., INAU10, INGB3, INTR9). While individual obstacles originating, e.g., in a lack of financial capital, cultural factors such as language, or the absence of capabilities, suffice to effectively hinder engagement, their interconnectedness further burdens mitigation measures. Interviewees report that vulnerable groups in particular are exposed to cumulative intersectional obstacles that need to be tackled jointly, if they are to be overcome (INGR8, INGR10, INNO7; for further details, see Section 5.1 and Section 5.2). For example, a migrant background may bring along deficiencies within the educational system, possibly resulting in a worse position on the labour market, which in turn involve a greater likelihood of lacking access to finance; when coupled with the characteristics of a single mother this poor starting position is further burdened by a lack of time, social capital and possibly the detrimental effects of focusing on short-term and poverty-related issues (“tunnelling”). At the structural level, prerequisites for the accessibility of financial and tax incentives (e.g., for installing RE installations and EE measures) designed to overcome individual obstacles further exclude the mentioned social groups. This is due to both the design of incentives (e.g., as they are frequently tied to matching contributions not available to the poor) and their perceived accessibility (e.g., trust in the offer but also trust in one’s own capability to take it up). The interviews (INAT6, INBG2, INNO9) confirm this, clearly showing how individual obstacles and systemic barriers are interconnected, corroborating the theoretical framework of the “engagement chain” (see Section 3.4).

6. Discussion—Institutional Environments, Ownership Vectors and Their Functional and Governance Context

In view of the following discussion of the above results, we would like to stress that the interview evidence we provide is limited to backing our conceptual approach. More empirical research is needed for each of the institutional environments we identify. The discussion and conclusion are restricted to conceptual implications. The discussion and conclusions are restricted to conceptual implications referring to institutional environments and the role of the public hand when fostering inclusive collective prosumership. The policy recommendations are then presented in the conclusions in Section 7.

Thus, this section seeks first to answer the second research question of which institutional and governance structures are best suited to support the different aspects of energy citizenship and where ECs are positioned. In the light of our results as well as the empirical findings of Section 3.2 and the governance trichotomy introduced in Section 3.6, we identify different forms of energy ownership as they relate to individual or collective engagement. We discuss their possible role to boost capabilities and overcome the interrelated obstacles, thus their potential for inclusiveness. Considering both potential and barriers for a large, so far underrepresented part of society, as described in Section 5, leads to the argument that there should be a supported realm of ownership for those still excluded who cannot compete in the realm of the market. We conclude this discussion postulating the need for a complementary institutional realm of (co-)ownership based on “solidarity” and open to those formerly excluded if the systemic obstacles enshrined in the “engagement chain” are to be overcome. To illustrate how such an institutional realm can be seen as a participation model, we provide examples.

6.1. “Ownership” Under a Governance-Oriented Approach

The notion of energy citizenship is gaining traction not only among civil society and academia, but also amongst policymakers (Radtke 2014; Ryghaug et al. 2018). Importantly, energy citizenship is not restricted to economic issues, but entails social, ethical and political aspects that transcend the mere role of citizens as market participants. Here, social and economic participation, including both decision making and rights of control and to fruits, is key, especially when looking at vulnerable and underrepresented groups. The participation—as well as the non-participation—of energy citizens in the energy transition is strongly reflected by their ownership of the newly emerging energy systems they are expected to adapt to. “Ownership”—not merely in the sense of civil law—implies pressing questions of (societal) responsibility, the willingness to change behaviour when executing said ownership rights, and an equitable distribution of benefits and burdens. It is thus a question of the scope of fundamental rights of citizens in the sense of constitutional law, closely linked to notions of equity across various social dimensions (Jenkins et al. 2016; Devine-Wright 2007).

To deduct implications for policy making from these complex relations, we depart from an ownership-oriented approach with a wide understanding of the term: As generally with regard to the ownership of productive property, the “society of owners” (a minority) simultaneously has to be understood as a “society of non-owners” (the majority); ownership in this context first and foremost is a social relationship between these two groups and the state, heavily influenced by the social function of ownership in a sector where the entire population relies on access to clean, affordable and secure energy. In this context, ownership furthermore implies an important responsibility the owner—public or private—has vis-à-vis the non-owner, i.e., that of setting the agenda of the things owned for society (Lowitzsch 2019; Katz 2012). This is of particular importance for the energy sector since a large part of the infrastructure is (still) at least partly state-owned, while most citizens are not engaged (yet).

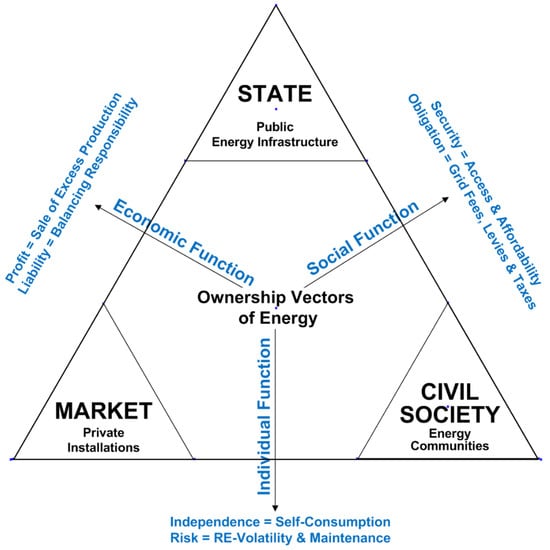

Based on the above analysis and depending on both the functional context and the political aim, we can identify different forms of energy ownership as they relate to individual or collective engagement and the extent of their potential for inclusiveness. These ownership types may—but do not necessarily—involve (co-)ownership of private individuals, and they may involve the cooperation of heterogeneous actors, including private enterprises, the state, or municipalities. The complex relations between these types of actors can be described on the one hand by the different functions of ownership acknowledged in research (Lowitzsch 2019), namely, the economic, the individual, and the social function and, on the other hand, by different forms of ownership derived from the types of owners, namely private ownership, that of the state and that of ECs (Roggemann 1997). This functional context, when transferred to the energy sector, results in a force field between the different ownership functions as vectors of “energy ownership” and the respective institutional environments (see Figure 7):

Figure 7.

Ownership functions as vectors of “energy ownership”; authors’ own elaboration.

- The right to receive the yield of the sale of energy produced, but also the obligation to assume corresponding liabilities and risks, e.g., the balancing responsibility—the “economic function”;

- The guarantee of the personal right of producing energy for self-consumption, facilitating independence but also the associated risks, e.g., the volatility of RE and the burden of maintenance—the “individual function”;

- The provision of access to energy infrastructure and of energy security, but also the related obligations like grid fees, levies, and taxes—the integrational or “social function”.

6.2. Energy Ownership Vectors Require Different Types of “Energy Ownership”

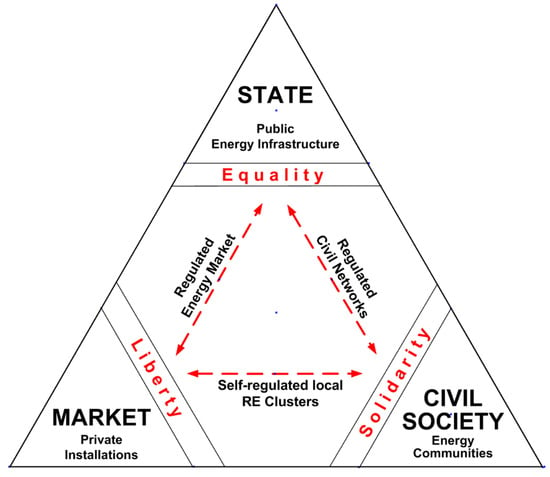

The identified energy ownership vectors, in turn, require different types of “energy ownership” which, in the functional context of their corresponding institutional environments, ensure a different part of the array of fundamental energy rights. Referring to Figure 3 (see Section 3.3), these fulfil different and distinct functions regarding ensuring that citizens can actually exercise and make tangible use of their energy citizenship rights. Corresponding to the institutional environments, we distinguish three types of “energy ownership”, namely,

- Private ownership of production installations guaranteeing the unfolding of personal freedom of the economic subject, both with regard to entrepreneurial and individual rights, branded here with the catchword “liberty”.

- Public energy infrastructure, indispensable to guarantee broad access to all members of society independently of their geographic location and ensure the affordability of a basic energy supply, ensures a minimum of parity of all citizens—hence branded as “equality”.

- Ownership of energy infrastructure conveyed by ECs with a separate and distinct legal personality, be they private, public, or mixed, first and foremost RECs, but also CECs and other forms of ECs. The economic power of these entities typically stems from the large number of contributing shareholders or members based on a solidarity mechanism; while their primary purpose are community benefits rather than profits ECs—provided that they receive targeted support and are credited for doing so—could ensure the right to inclusive participation, solidarity, and recognition; thus, they can be captured by the term “solidarity”).

Table 2 presents these ownership nexus/force-field types in more schematic detail, while suggesting, at the bottom, the institutional environments that are promoting the underlying values.

Table 2.

‘Force fields’—different function-ownership orientations; authors’ own elaboration.

All types of ownership can coexist next to each other, but—depending on their setting and purpose—follow different rules and need distinct incentives, as enshrined in their institutional environment. An example illustrating these differences is the (mis-)perception of prosumership as typically associated with homeowners (see Section 5.1), which neglects the fact that 31% of people in Europe live as tenants and cannot afford to own family homes (Eurostat 2023). The large group of tenants (next to other underrepresented groups) will, however, be unlikely to engage in the institutional realm of “competitive markets” and thus require a different realm. Thus, institutional environments find their legitimacy in socio-legal and political functions of (energy) ownership backed by constitutional principles. These are mostly acknowledged in constitutional case law, such as the provision of general services, freedom of entrepreneurship, and social integration. However, their concurrence gives rise to conflicting forces that need to be balanced against each other permanently, such as in the avoidance of how liberty (and the competitive market) can crowd out solidarity (and civil networks); e.g., when big utilities capture ECs. In the engagement context, this approach, with its functional distinction, allows for justifying and tailoring financial incentives and support for capability and capacity building. Considering the empirical findings on engagement presented earlier, the ambition of increasing RE production leads to specific challenges for each institutional environment: promoting prosumership in the market, achieving inclusiveness in civil society, and facilitating equitable access by the state. Below, we argue how these challenges can be addressed through complementarity.

6.3. Complementarity—The Three Institutional Environments Seen as Participation Models

At the same time, decarbonization goals are set at different levels of private and public networks, from a single EC, to regional energy networks, to Member States and the EU. We identify participation models that present distinct modes of such mediation in collective action, to be operationalised in and across institutional environments and geographies. In doing so, we apply the above socio-legal ownership concept as an analytical lens in determining how energy rights may be inclusive, supportive, incentivising, empowering, and enforceable within the institutional context. Taking up the institutional trichotomy discussed in Section 3.6, this representation, as shown in Figure 8, also reflects hybrid zones between ideal-type institutional environments that combine the related elements (Heldeweg 2017):

Figure 8.

Trichotomy of institutional embeddedness including hybrid ownership zones; authors’ own elaboration.

- (a)

- Those of state and market and thereby of liberty and equality—such as a ‘regulated energy market’ (to secure a level playing field, maintaining scope for profit-making and competition-driven innovation but also facilitating individual prosumership that is affordable and profitable);

- (b)

- Those of state and civil society and thereby of equality and solidarity—such as ‘regulated civil networks’ (to secure equal access to a minimum and reliable service, while enabling scope for collaboration on and sharing of common pool energy resources);

- (c)

- Those of market and civil society and thereby of liberty and solidarity—such as municipal ‘self-regulated local RE clusters’ (to allow ECs to enter B2B and B2C market transactions, while focusing on inclusive engagement that fits public entity involvement and enables citizen (co-)ownership).

The latter type of hybrid institutional environment is particularly suited for facilitating and supporting inclusive participation to avoid the risk that some potential participants do not engage due to intersectional inequities (see Section 5.2), of which the risk was clearly demonstrated in the abovementioned empirical findings. In summary, the pros and cons of these ideal-type institutional environments allow for and, in practice, often display hybrid approaches seeking to balance liberty and equality, equality and solidarity, or solidarity and liberty, or all three.