Abstract

This article explores urban ‘societal resilience’ during the global pandemic of 2020–2021. This health crisis involved a complex interweaving of social, cultural, political, and economic processes which involved both top-down measures undertaken by nation-state governments and bottom-up actions by local residents. In a research study undertaken in two European cities—Stuttgart and London—we focussed on two migrant minorities and the involvement by ‘experts’ and ‘non-experts’ in the meso-level where these top-down measures and bottom-up actions met. Our study provided a grounded understanding of ‘layered resilience’ where resiliency develops through the disjunctive order of communication patterns, public service delivery, institutionalized dialogue, narratives, and values. Through distinguishing between resiliency and resilience, we seek to illustrate the ‘elastic’ character of urban modes of integration. Our study suggests the need for more empirically grounded investigations into the continuity and difference between adaptation and adjustment, normality and normalcy, and resilience and resiliency. It also highlights the importance of context-specific and path-dependent notions of resilience and resiliency.

1. Introduction: Conceptualizing Social Resilience

In their ambitious account ‘on society’, Elliott and Turner (2012) refuse to give in to a pre-emptive notion of ‘the end of society,’ preferring instead to describe contemporary society as ‘elastic’. Although the intertwined processes of globalization and individualization might have led to a corrosion of stable social structures developed during industrial modernity, and disruptive developments, such as global warming, might cause future instabilities, they claim that new forms of solidarity and creative social engagement tend to emerge. Elliott and Turner use the metaphor of ‘elasticity’ to describe where society’s social ties become ‘stretched’ but retain ‘resilience and versatility’ (p. x) and suggest that a multi-directional investigation could be undertaken into ‘society as structure, society as solidarity, society as creative process’ (p. 15). We not only agree with their argument but also with their suggestion that research needs ‘to enter, as it were, society at street level’ since ‘the three distinct senses of society […] are deeply embedded in the production of everyday social life’ (p. 21).

To further unravel the complexity of this resilience, we can draw on Bardhan’s analysis of ‘a world of insecurity’ (Bardhan 2022). He argues that the answer to the creeping anxiety and insecurity caused by such disruptive developments, such as the global financial crisis, global warming and, most notably, the COVID-19 pandemic, does not involve calling for a ‘strong state’ or retreating ‘back to the community’ but, rather, drawing on the potential of ‘state capacity’ (p. 125f.) At the local level, this potential shows itself through the routine ‘top-down’ delivery of public services to the entire resident population, including minority groups (pp. 72, 94). This encourages people to actively support or ‘own’ local state policies (p. 184): At the same time, ideally, state capacity is complemented by bottom up ‘community-level social solidarity’ (p. 127)—a highly valuable resource of resilience, which is expressed not just in the myriad occasions of mutual help during situations of immediate crisis, but also as the seedbed of sustainable trust, networks of reciprocity, and information flow (p. 7). Where state capacity and community level social solidarity meet, state capacity can be enhanced not only technically but also through fostering the sense of a ‘local social contract’, especially if this contract manages to embrace the various social and cultural groups that constitute local society (pp. 9, 39).

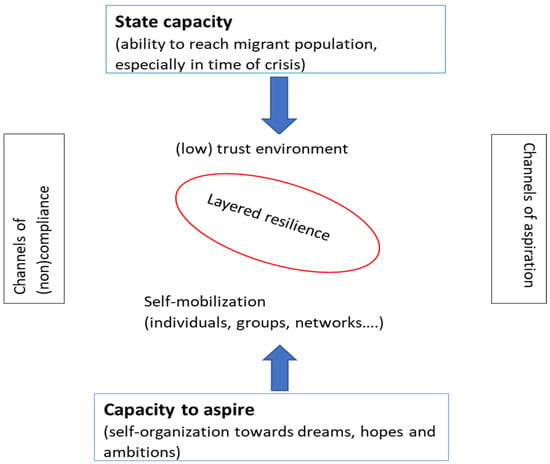

To give this approach a more thorough theoretical grounding, we draw on Fukuyama’s thinking concerning state capacity (Fukuyama 2013, 2004) and what Appadurai has described as the ‘capacity to aspire’ (Appadurai 2013, 2003). Fukuyama defines ‘state capacity’ as the capacity of governments to enforce legal rules and deliver public services across a variety of functions, institutional levels, and communities. State capacity relies less on the formal enforcement of a strict body of law, and more on assets of ‘good governance’, such as people’s trust in the professionalism of administrative staff, the reliability of public institutions, and convincing leadership. Essential in all this is the level of ‘discretion’ displayed by local bureaucrats since it is at the local level where citizen feedback and cooperation by local bureaucrats with civil society tend to enhance state capacity. However, it also means that state capacity is relational in character since it heavily relies on ‘the self-organizing capacity of the underlying society’ (Appadurai 2013, pp. 2f., 9f.; 2004, p. 67ff.). Hence, the ‘capacity to aspire,’ as described by Appadurai, is the necessary complement to ‘state capacity,’ since it describes people’s efforts to maintain their everyday routines and to approach the future in terms of a vision of a ‘good life’ worth pursuing. This capacity to aspire involves people’s everyday efforts to maintain a ‘sense of permanence in the face of the temporary,’ as well as the ‘collective ideas of what is possible’ that nurture individual dreams, hopes, and ambitions (Appadurai 2003, p. 46ff., p. 52). Finally, according to Appadurai, the capacity to aspire needs to be seen as contextually embedded. In terms of exploring the potential of societal resilience, we need to appreciate the importance of ‘local systems of value, meaning, communication and dissent’ (Appadurai 2013, p. 290).

The claim that ‘state capacity’ and the underlying societal ‘capacity to aspire’ become particularly evident during times of crisis, such as a pandemic, has become a truism. Indeed, at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, Fukuyama described it as a ‘global political stress test’ (Fukuyama 2020a, 2020b) and predicted that those countries, which turn out to be more resilient, would be those that were not only able to mobilize ‘adequate resources’ but also generate ‘a great deal of social consensus’ and produce ‘competent leaders who inspired trust’ (Fukuyama 2020a, p. 8). Moreover, these societies would be able ‘to provide solutions [by] drawing on collective resources in the process’, notably a lasting sense of ‘social solidarity’ (ib., p. 6). In other words, resilient countries would deal with the pandemic not merely as a question of ‘technocratic expertise’ but also as one of ‘social learning’ (ib., p. 8).

Early empirical evidence supported this claim by suggesting that those countries, which fared well during the initial stages of the pandemic, drew on a pre-existing public culture that supported governing structures based on non-linear information exchange, adaptive public services, and an integrative narrative for managing uncertainty (Hanson et al. 2021). In Germany, for example, ‘broad societal support’ for the initial governance measures was generated despite cultural diversity and social pluralism (ib., pp. 1, 7, 11f.). In turn, early empirical evidence also indicated that there was a low ‘response capacity’ where overall trust in government and public support for pandemic governance was lacking. In Hong Kong, for example, ‘community capacity’ was obliged to compensate ‘for the lack of formal state capacity’ (Hartley and Jarvis 2020, p. 403f.). Therefore, this process did not just involve complying to government measures, but was also expressed through bottom-up coordinating and funding structures, material support for the most vulnerable, collective measures of risk behaviour control, and information exchange via social media. In sum, ‘response capacity’ cannot be fully understood if it is primarily seen as a ‘government-centred capacity’. Furthermore, to understand ‘response capacity’ more fully, we need to look beyond measures of purely epidemiological management (ib., pp. 403f, 416).

Our approach to societal resilience draws, therefore, on a notion of ‘response capacity’ that is neither primarily focused on governance nor on community activity. We see it as a complex and open process shaped by the relationship between governance-related ‘state capacity’ and the community-based ‘capacity to aspire.’ It is an emerging capacity that involves both state and non-state actors, and is derived from institutional and interpersonal interaction, linking together people and institutions through values, narratives, and everyday practices operating at various levels of society.

Our approach relates to notions of ‘layered resilience’ that are deployed in various research fields, ranging from mitigation research and health system governance to child psychology and family coping (Obrist et al. 2010; Blanchet et al. 2017, p. 432f.; Maurović et al. 2020, p. 339f.). However, we feel closest to approaches that refrain from regarding resilience as an individual asset or a systemic attribution. Instead, we see it as emerging through a disjunctive interaction between different social units. To put it more abstractly, we regard it as the result of ‘social structuration’, defined here as the converging interplay between social structure and social agency (Obrist et al. 2010, p. 284; Mu 2020, p. 6; Maurović et al. 2020, p. 340).

This definition might be counterintuitive to everyday understanding, where resilience is often seen as an individual trait and resiliency as its social outcome. However, our approach overlaps with the ‘social constructivist perspective’ as outlined by Endress (2015). Here, social resilience is approached through a de-essentialized, non-linear, non-normative, and comparative perspective, where ‘resilience’ is distinguished from ’resiliency’ in a more substantive way (cf. Maurović et al. 2020, p. 340f.). Resiliency refers, therefore, to the continuous attempt of self-persevering and self-governance that a small social unit undertakes in order to maintain a pattern of situatedness or identity within a larger social unit. Resilience, on the other hand, refers to the additional effort that this social unit can mobilize in times of crisis. This distinction between resiliency and resilience ties in with the distinction between ‘normality’ and ‘normalcy’ that Giddens (1993) makes during his analysis of identity in modern society. While normality carries normative undertones and suggests the equation between the optimal and normativity, normalcy refers to the continuous working on the stability of a social milieu by linking together compatibility with the outside world and the maintenance of inner moral integrity (ib., p. 127f.).

2. Research Design and Methods: Forensic Sociology and Travelling Ethnography

In a research project between 2020 and 2022, funded by Volkswagen Stiftung, we compared three European cities (Stuttgart, Milan, and London) and their analytically most suggestive minority ethnic groups (cf. Caselli et al. 2024). We investigated the relationship between the ‘response capacity’ and social cohesion of a society, by exploring where those from a migrant background1 looked for help and orientation during the pandemic crisis. Given the ‘habitual indeterminacy’ of migrant social embeddedness (McGhee et al. 2017), their integration during such a crisis can be seen as a ‘litmus test’ of both societal resilience and social cohesion. Typically, those from a migrant background become acquainted with the dominant culture and institutions of the society where they settle, while maintaining at least some ties with their countries of origin. Under favourable conditions, this social positioning can foster the development of innovative hybrid identities but, under less favourable conditions, it could lead to marginalization. While a societal crisis, such as the pandemic, fostered a pragmatic sense of solidarity based on ‘effective membership’, it also highlighted the precarious residential or citizenship status of the migrant population (cf. Triandafyllidou 2022). We therefore wanted to explore whether people put their trust in public services or minority ethnic networks, in political leadership or advice from community leaders, and whether they supported government measures or set up ethnic community structures, listened to official information or relied on ethnic information flows. So, while the pandemic might not have been a game changer with regard to migrant integration, it did show the important role played by proactive mobilization, compliance, or perhaps even resistance among minority ethnic groups with regard to state capacity. Here, for the sake of analytical contrast and article length, we will draw on data collected in two of the three cities—Stuttgart and London.

There are at least three good reasons to investigate societal resilience emerging from the relationship between state capacity and the capacity to aspire at the municipal level. First, and drawing on Bardhan’s (2022, pp. 9, 72f.) point mentioned above, we assume that it is at this meso-level of governance where a great deal of public services is being offered to the resident population and that this offer makes the (non)reliability of the state and the ‘social contract’ between the state and its citizens transparent. Secondly, to further uncover the dynamics of this ‘local social contract’, we assume that administrative structure, migration history, civil society tradition, and urban leadership can make a difference in terms of local social cohesion (Vertovec 2020, p. 24). Finally, these two assumptions are neatly brought together in the claim made by Schönwälder that we need to contrast particular collaborative urban cultures in order to understand better ‘how localities and local actors shape the life chances of immigrants’ (Schönwälder 2020, p. 1932ff.). However, unlike other attempts to visualize ‘multilayered resilience’ (cf. Obrist et al. 2010, p. 289), in the graph below(Figure 1), we leave the middle ground of emerging meso-level resilience largely uncharted to indicate the open and contingent character of societal resilience.

Figure 1.

Locating ‘layered resilience’ (inspired by Penninx et al. [2004] 2020, p. 8; Obrist et al. 2010, p. 289).

Methodologically, then, we follow Inglis’ (2010) concept of ‘sociological forensics’, which seeks to illuminate ‘the whole from the particular’ by linking context-specific micro-observations to wider social structures and long-term processes of change. We also agree with his claim that an ‘in-depth analysis of a fragment of a particular case’ of urban culture of cooperation can ‘illuminate the social structure’ of emerging social resilience in urban society (ib., pp. 510, 514).

The ‘case studies’ we identified as units of analysis were not whole cities but localities where particular migrant communities were long established. Hence, in Stuttgart, we concentrated on the Turkish community that gravitated around the DITIB2 mosque located within the borough of Feuerbach, while in London we focused on the borough of Tower Hamlets and its Bangladeshi community. The case studies were illuminated by qualitative interviews with five ‘experts’ and eight ‘non-experts’ in Stuttgart and ten ‘experts’ and five ‘non-experts’ in London.3 The interviews were enriched by ethnographic observation of some of the developments affecting these communities as soon as restrictions on movement were lifted. The resulting ‘thick description’ follows the general assumption guiding qualitative research, namely that people’s narratives and everyday practice reveal (some of) the social structures and cultural frames through which their perception of fears and hopes, their conduct of routine and ambitions, and their performance of identity and social functions operate. More specifically, and with regard to qualitative interviewing as our main resource of data, we draw on ‘structural hermeneutics’ (cf. Alexander and Smith 2003).

3. Material and Discussion

When the pandemic struck in 2020, the question of state capacity with regard to migrant populations centred around ambivalence, nicely captured in the following question posed by Triandafyllidou: ‘What matters most: their effective residence or their immigrant status?’ (Triandafyllidou 2022, p. 6). From the outset, our empirical investigation of this issue was tied to two analytic questions in the field of integration policy. If there is indeed a ‘national turn on local integration policy’ as suggested by some observers (Emilsson 2015, p. 2), can this be equated with a homogenization of integration policy at the municipal level? Or does it need, despite some commonalities in the field of (im)migration policy across Europe, a renewed appreciation of the ‘variety of context- (and path-) dependent practices’ in this policy field (Ambrosini and Boccagni 2015)? In hindsight, we would say that these are questions are too general. Our research supports instead the assumption described above that administrative structure, migration history, civil society tradition, and urban leadership can make a considerable difference in terms of local social resilience during a crisis like a pandemic. It is to these local contextual differences that we will now turn.

3.1. Stuttgart: The Ambivalence of ‘Integrationism’

When delving into the Stuttgart interview material4, we immediately encountered the intense sense of de-bordering ‘civic solidarity’ based on ‘effective residence’ (cf. Triandafyllidou 2020, p. 263) that was especially dominant during the first phase of the pandemic in 2020. Our interlocutors spoke about the spontaneous support networks that helped to cater for people’s daily needs, such as shopping and organizing scarce goods, including toilet paper and sunflower oil, or were involved in the setting up of food banks for those in dire straits. However, sometimes the otherwise mostly silent fulfilment of civic responsibility in times of crisis appeared on the public stage. A 51-year-old member of the mosque community, who was a German citizen that worked in logistics for the car manufacturer Porsche, explained the following:

Yes, yes that [transethnic solidarity] was done, yes. There were also some actions within the Islamic community. Let’s see if I can think of one example right now… Well, I know that they brought roses and gifts to hospitals, to the nursing staff. It was with a little dedication and with logos attached. They kind of wanted to send a signal as a community that they would abide by the rules.(Stuttgart 1; 10/11, p. 33–2)

This quote can be read as an indication of the underlying capacity of society to organize itself on an inter-individual level in new modes of bridging solidarity during an exceptional situation. However, it can also be read, especially towards the end of the quote, as a soft articulation of a widespread fear about ‘passing’ as fully reliable members of society. It would seem that what has opened up next to residence-based solidarity is the contested field of ‘moral citizenship’ (van Campenhout and van Houtum 2021, pp. 1, 10).

The issue of ‘formal and moral deservedness’ has become a widely discussed issue in Germany since the debate started whether it has become a country of immigration, especially when the process of obtaining formal or legal German citizenship was made easier from 1990 onwards. The debate has particularly focused on migrants with Muslim roots and has led to questioning whether their acceptance of the country’s dominant norms and values was genuine (Lewicki 2018, p. 505f.; Schönwälder and Triadafilopoulos 2012, pp. 58f, 62). Thus, paradoxically, the pandemic made demands on its members based on effective residence or jus soli, while at the same time the distribution of social respect and everyday cultural recognition, which underpins societal resilience, still tends to work according to the principle of jus sanguinis or rights based on blood ties (Geißler 2004, p. 288; Schönwälder and Triadafilopoulos 2012).

Hence, at the meso-level of migrant self-organization, we encounter a keen concern with ‘normalcy,’ based on the everyday tactics of self-perseverance by a particular group amidst the changing normative requirements of the surrounding society (see Section 1 above for recalling this terminological differentiation). In the following quotes, the representative of the DITIB mosque community presents the ongoing organization of compliance with quarantine rules and lock down restrictions as a contribution to overcoming a situation of societal crisis:

Of course, with [distancing] provisions in place, … [we] were very happy that at least we could temporarily open our mosque and it wasn’t closed down completely. But, um, exactly during the times that there were curfews and so on, we discussed whether we, um, keep our mosques temporarily closed, just to make our contribution, um, to the betterment of the society or the pandemic, accordingly, to make our contribution to what will lead to normalization—this we discussed among one another especially also during Ramadan… Legally, let’s say, we did have the option [to open the mosque], but we didn’t make use of it, in order to contribute our share.(Stuttgart 2; 18: 22–33; our emphasis; cf. Caselli et al. 2024, p. 66)

The repeated reference to doing more than formally required by pandemic state regulations ‘in order to protect our community’ (e.g., Stuttgart 2; 1: 30–31) was not purely related to epidemic concerns. It also appeared to express a strategic over-compliance in the face of CRD (COVID-related discrimination), that was also faced by the Turkish community amongst other ethnic minority groups (cf. Dollmann and Kogan 2021).

However, it would be misleading to equate resilience in the urban culture with an overambitious transmission of government regulations by migrant associations in order to demonstrate moral deservingness. The core of the resilience pattern under investigation can instead be found in the fuzzy middle ground between ‘community capacity’ and ‘state capacity’, as envisaged in Section 1. The DITIB representative describes this as follows:

That is, um, a two-sided path that we walk again and again. We are open to any cooperation. Um, …we are always in contact with them [borough council leaders], and, um, also work together when we have problems, they are always available. And on the other hand, when we are able to help, we are accordingly always available insofar as we are able to do something.(Stuttgart 2; 7: 1–5; our emphasis)

The borough council leader implicitly agrees with this strategy and adds what she describes as her personal approach to the local DITIB mosque association:

I think it’s a bit of a pattern. Uh, people want to be addressed more directly and personally. So, a friendly invitation by email, for example, the way our life just works now [due to COVID restrictions] … so this direct, personal approach, uh, I think that is still, uh, more helpful at the moment. That is, if I … now, uh, went down to the mosque and asked the chairman and two or three others for a chat and had said: “Well, … I really want you to take part in this and that, and please do come up with something”—I think they would not have resisted it.(Stuttgart 3; 6: 24–31; our emphasis)

This mode of personalized communication by a member of the local state bureaucracy was made possible by ‘discretionary power’ wielded at street level. This official decided to show respect and social recognition towards those who were long-term partners in integration matters (cf. Dimitriadis et al. 2021, p. 257; Homberger et al. 2022, p. 107f.). The actions of the borough council leader testify to the horizontal leadership dimension of local governance within a multi-level governance regime:

I, in my role, or we as district heads in our role, we have a lot of leeway there. That’s how I see it too, through our, uh, sandwich function. … We are not so tightly integrated within the administrative hierarchy. … An essential part of our work is also community work and, uh, citizen participation and, and, and…. there is leeway and you have to, you can use it, yes.(Stuttgart 3; 16: 4–7, 16–17; our emphasis; cf. Caselli et al. 2024, p. 185)

We asked the leader of the council and the representative of the migrant association whether the trust and close coordination evident between their two organizations was based on institutional foundations or personal relationships. They both rejected this either/or proposal. The city council replied, ‘Because it is an area of sensitive change, you have to gain trust again and again, and having the flair for it’ (Stuttgart 3, 7: 29–30), while the DITIB representative responded, ‘That is, ehm, a two-sided path that we walk again and again. We are open to any cooperation’ (Stuttgart 2; 7: 1–2).

Their responses could be explained in terms of what the phenomenologist, Aaron Gurwitsch, describes as ‘patterned trust’, established through a multitude of routine practices, such as that performed by a local advisory committee holding regular meetings. This kind of trust is characterized by a ‘fiduciary attitude’ that, according to Vaitkus (quoted in Chriss 1992), operates through people’s readiness to ‘believe in the other.’ The attitude is based on the relationship between -(a) the consignment of milieu-specific, taken-for-granted assumptions in everyday life; (b) the commitment to a shared task; and (c) an element of faith in the future based on shared values rather than short-term interested’ (Chriss 1992, p. 284).

This type of trust, as described by our two interlocutors, provides us with a vivid illustration of resiliency as an open and emerging process that makes no clear distinction between agency and structure or between personal commitment and functional obligation. In other words, what we encounter here is, indeed, resiliency in the mode of ‘structuration’ (see Section 1 above). Out of it, all kinds of contingent results can emerge, be it a ‘long night of culture’ that represents the borough’s cultural diversity in ordinary times or a vaccination pop-up centre based at the mosque during the pandemic. The deputy borough leader nicely pinpoints the mosque association’s emergent and ‘structurated’ character in her description of the vaccination joint venture: ‘Well, we solved that in a very unbureaucratic way’ (Stuttgart 4; 3: 24, our emphasis).

Yet, resilience—and resiliency, for that matter—always contains an element of ambivalence. This is revealed quite clearly when the DITIB mosque representative describes the same issue, i.e., the vaccination and texts centre based at the mosque:

Of course, it’s easier in a trustful cooperation: it’s team work, nothing else. You can also compare it with sports, say driving in a rally. A co-pilot and a pilot, one who actually just steers (…). I don’t want to make light of it now [chuckles], and the co-pilot, um, he actually tells him what the route is, what kind of steering he is supposed to do. Um, and there you have this trust, that you have a blind trust. Roughly, that the trust is very big so that you … can work much better and more qualitatively and … faster together. And, we as mosques also have this bridge function, so that we are much better able to reach the individual communities, um, that the authorities are unable to reach, or that institutions are unable to reach.(Stuttgart 2; 9: 24–32, our emphasis; cf. Caselli et al. 2024, p. 192)

This quote shows a concern about not allowing the emergent pandemic resilience to look like a government-centred response capacity. One might even detect an outright challenge to local state power, even if it is presented in a light-hearted and metaphorical manner. In our view, the fact that power issues do not become more prominent has less to do with the pandemic emergency than with another crucial characteristic of the urban culture of cooperation under investigation here. Stuttgart could be seen as a clear case of ‘integrationism’—what Nieswand describes as a quasi-ideological ‘bridging frame’ (Nieswand 2021, p. 89). The ‘hypergood of integration’ gives legitimacy to policy coalitions of state and non-state actors (ib., p. 44). Essentially, it can generate vivid social resonances by supporting social cohesion with moral claims—who can seriously object to the ideal of ‘integration’? At the same time, it promises not to disrupt the real existing social order with its hierarchical distinction between insiders and outsiders (cf. ib., p. 85ff.).

The societal project of ‘integrationism’ can sustain this inner ambivalence by oscillating between two strategies. One involves a discourse of abstract and thereby inclusive ‘humanitarianism’, while the other translates prevailing social disparities in matters of ad hoc ‘administrative–technical’ action (cf. ib., pp. 78, 84, 86). In a condensed version, we can detect this dual strategy by listening one more time to the borough council leader’s words:

The vaccination campaign went really well, uh. So—sometimes I think we, maybe you too, worry too much about what separates us, even though we are all just humans. And uh, people with a migrant background are moved by exactly the same issues as we are. That is, how do I get my family through the pandemic?(Stuttgart 3; 17: 19–22, our emphasis)

Although ‘integrationism’ has contributed to resilience both in terms of ad hoc adaptation to a pandemic crisis and an urban culture of cooperation at the borough-level, the question remains: has it also facilitated resiliency in terms of ‘engineering transformational change’ (Mu 2020: 7) or ‘transforming adversity to opportunity’ (Obrist et al. 2010, p. 287)? To us, it seems that ‘integrationism’ encouraged a return to the status quo ante rather than supporting the reorganization of resources of layered resilience into new strategies. The concluding remarks from the representative of the German-Turkish Forum illustrates this impression:

And in terms integration work [laughs], at school or wherever, um, yes, I think those will be the most central questions … that have to be resolved, where I don’t have high hopes that something will change when everything goes back to normal again, but, um, maybe you can somehow learn more from it for the next natural disaster [chuckles].(Stuttgart 5; 26: 13–16)

Stuttgart’s discourse of ‘integrationism’ can be traced back to its industrial heyday during the 1970s and 1980s (cf. Meier-Braun 2009). As a rapidly developing centre of the German car industry, it was reliant on a steady influx of foreign labour, not least from Turkey. Manfred Rommel, who was mayor at that time, quickly realized that ‘gear box assembly line integration’—as the New York Times (Kimmelmann 2015) aptly branded the DNA behind Stuttgart’s economic success story—was not enough for maintaining an urban society characterized by growing cultural diversity. Accordingly, a dense web of organizations was launched under Rommel and later refined by his successor, Wolfgang Schuster. For instance, the German-Turkish Forum was set up during 1999 and its programme explicitly refers to the importance of exchange in the realm of art and culture in strengthening the social unity of urban society. There is also the Stuttgart Council of Religion, which was established in 2015 and seeks to maintain a continuous dialogue between religious communities in a world where religion has become a major feature of local identity formation. This cluster of organizations, geared towards urban dialogue, has contributed to the development of overlapping personal networks of patterned trust, based on the commitment to both the reality and ideology of ‘integration’.

3.2. London: Ethnic Community Organizations and the Local State

In many ways, London is very different from Stuttgart. It is a far larger geographically—Greater London extends across approximately 1572 square kilometres—and its population is more than 8,500,000 (https://www.cityoflondon.gov.uk/about-us/about-the-city-of-london-corporation/our-role-in-london, accessed on 4 September 2025). The metropolis is divided into 32 local boroughs and is highly diverse ethnically and racially. Unlike Stuttgart, its economy is largely non-industrial and is dominated by the service sector, where finance and business operations, the retail trade, leisure and tourism, health, welfare, and educational services are major employers,

Despite these contemporary differences, historically, the borough of Tower Hamlets where we decided to locate our London research was similar to Stuttgart. During the 19th century up until the 1980s, industrial production played a major role in the local economy, although this was based on small business rather than the large global companies, which are such a feature of Stuttgart’s economic structure. Migrants fuelled the demand for manual labour in the small garment and furniture factories across the borough’s northern wards and from the 1960s, this migration flow was dominated by young men from Bangladesh. They settled in neighbourhoods that contained pockets of deep poverty and where the Labour Party had long been a major political force, drawing not only on ‘working class’ solidarity and trade union organization but also ethnic and racial identities. Furthermore, the party was closely aligned to the ‘local state’ that administered public resources, such as subsidized housing, amenities, and medical services.

During the 1980s, the economic, social, and political landscape began to change rapidly. By the time the pandemic struck, the factories had closed, the southern wards in what was now called ‘Docklands’ were dominated by high rise blocks containing the offices of the highly globalized finance and business sector, while the northern wards had become heavily reliant on small commercial enterprises, with the retail trade and public services controlled by the local state. Politically, the Labour Party also faced a serious challenge from other parties such as the Liberal Democrats, Respect and Aspire. In the most recent borough election of 2022, the party was defeated by Aspire, a political organization led by the highly controversial Bangladeshi politician and former Labour Party representative, Lutfur Rahman (https://www.standard.co.uk/news/politics/lutfur-rahman-tower-hamlets-mayor-aspire-b1205024.html, accessed on 6 September/2025).

Bangladeshi residents played a key role in these political and economic developments since they constituted the largest ethnic group in the borough. According to the 2021 national census, Bangladeshis comprised 34.6% of the borough’s population https://www.towerhamlets.gov.uk/Documents/Borough_statistics/Tower-Hamlets-Borough-Profile-2024.pdf, p. 1, accessed on 6 September 2025). Family formation during the 1980s and 1990s saw the development of a settled, multi-generational population where substantial numbers from the second and third generation found jobs in the service sector after education in local schools and colleges. Linguistic and territorial ties with Bangladesh remained strong and religious identity was buttressed by the establishment of mosques and madrassahs and the global flow of information and images.

In 2020, when the pandemic struck, there existed a substantial number of representatives from non-religious and religious organizations and political parties, as well as those pursuing professional careers in the service sector. These representatives became key players at the meso-level where state capacity and the capacity to aspire met since they were involved in a variety of community activities. Our ten ‘experts’ were recruited not only from those based in two local mosques but also activists who were members of non-religious community organizations, including those working in the National Health Service (NHS), a journalist, and a ‘COVID Champion,’ who was paid by the borough council to help Bangladeshi residents in a variety of everyday practices including engaging with government initiatives, such as the 2021 vaccination programme.

Bangladeshis were building careers within the NHS (National Health Service) and they played an important role within this state institution at various levels, not least during the pandemic. In 2021, 30.5% of junior doctors were recorded as ‘Asian,’ while 32% of senior doctors were also placed within this category (Stockton and Warner 2024, p. 13) and although those of Indian heritage constituted the largest section of ‘Asian’ doctors, Bangladeshis were also entering the medical profession and occupying other positions within the NHS. For example, one of our interlocutors was a young hospital doctor, who had grown up in the locality. He saw the NHS as traditionally supportive of his community but was critical of the role it played during the pandemic:

…until the pandemic, the NHS has always been the… a friend of the community and that’s a positive thing. [However], as politicians started announcing science management and medical science programmes, it became part of the establishment. Because we always celebrated the NHS − it’s always been there for us ever since Bangladeshis came into this country − … but when everything started merging into government, people lost trust in the NHS.(London 3; 5: 41–46; our emphasis)

Additionally, this recent feeling of distrust towards the NHS strengthened the long-established lack of trust between British Bangladeshis and the government. Another interlocutor, who was trustee of a Bangladeshi heritage organization, commented the following:

… people from the East End don’t really look to the government to sort their lives out − they haven’t done historically and I don’t think they do anyway. But people are very enterprising and find ways to do things within our communities that do support each other through adversity … So we’re not really expecting the government to be able to make our lives better to be honest.(London 2; 8: 25–33; cf. Caselli et al. 2024, p. 200)

In sum, we have a situation here that differs considerably from the ‘integrationist’ urban culture of cooperation in Stuttgart that could be mobilized in a pandemic crisis. Instead, we find a ‘community capacity’ that is largely based on (ethnically) bonding rather than (socially) bridging networks, and a revamped NHS that enacts ‘state capacity’ in a rather technical and authoritarian mode. The doctor explained this situation in terms of different experience and cultural traditions:

No policymaker can explain overcrowding to me because they’ve read it in a book or they’ve read it in a paper—I’ve lived it… And so to say that we’ll send people to hotels or we’ll do this or that policy …it’s not that easy, mate… It’s not what you think it is because you’ve not lived it. It makes sense in your head that it’s just an overcrowded house, so we’ll just create more space but what about that family dynamic or that cultural dynamic or that cultural aspect of it that you don’t understand? … Like, if my dad got COVID and then if I had to live in a separate house or a hotel… that’s just not something I would do [as a Bangladeshi].(London 3; 5: 28–34; cf. Caselli et al. 2024, p. 198)

So how, then, is societal resilience in a pandemic to emerge amidst this yawning gap between ‘community capacity’ and ‘state capacity’? Our interviews suggest that this was the time of the charismatic ‘social broker’ (Blanchet et al. 2017, p. 435). The Bangladeshi doctor, for example, could act as an intermediary, drawing on his connections and professional training:

Yes, I felt like a middleman between the two… because a lot of the people that I care about or that I want to serve are my friends and family and people that I have personal connections with …and so when I go to these meetings with government and policy makers and people who make the big decisions, it’s a personal battle because I can see it from their point of view as well.(London 3; 5: 22–26; our emphasis)

Although he continues to see himself as part of the Bangladeshi community in London’s East End, who is able to ‘speak as a Bengali doctor to Bengali patients,’ he also leaves no doubt that due to his education at one of the UK’s more prestigious universities, ‘these white middle class people have accepted me into their space’ (London 3; 4: 9–10, 8: 40–41). Hence, the pandemic for him was a time of intense professional medical but also social cohesion work. Next to his shifts in his hospital department, he engaged in knowledge transfer through the East London Mosque and BBC Asian Network TV, as well as lobbying for better data survey and analysis via government-related bodies such as Public Health England. Consequently, he played a key role in the eventual success of the vaccination campaign within the local Bangladeshi community as a mediator between cultural and social cleavages.

Unlike in Stuttgart, the success of the vaccination campaign, in particular, and societal resilience towards a pandemic in Tower Hamlets, more generally, cannot be attributed to the patterned trust that emerges from continuous dialogue between state and non-state (migrant) stakeholders. In this area of London, it was partly the result of ad hoc and charismatic engagements by individuals drawing on their social networks. The key to the emergent societal resilience in this case, then, is aptly described by the doctor as borrowed trust:

I think I’d describe it as it’s borrowed trust and it’s facilitating trust rather than building trust… What I mean by that is that I haven’t made people trust the government… people trust me… People trusted me to take the vaccine or people trusted me or the Imam when we did the Q & A [questions and answers session] − those are the people they trusted… Building trust with the government’s not going to be something they watched on YouTube or watched on the BBC Asian Network… [Trust in government would much rather derive from] those other aspects of the public sector that people have to have a positive experience of, say the benefits system… the welfare system… social housing… the education system, those sorts of things.(London 3; 11: 29–36; our emphasis; cf. Caselli et al. 2024, p. 201)

As the last sentence of the above interview indicates, both here in Tower Hamlets and Feuerbach, successful pandemic resilience does not guarantee greater societal resiliency in the sense of social cohesion—social disparities would have to be addressed in order to foster (more than borrowed) trust in government and its policies. Makeshift efforts without structural adjustments in the relationship between (local) state and (migrant) communities, such as the one undertaken by the Bangladeshi doctor and his network, means that state capacity is temporarily supported in ‘strength’ but not ‘scope’ (cf. Fukuyama 2004, p. 7). The doctor commented the following:

It had a huge impact when we did the first [vaccination] clinic in the East London Mosque and when we did the Q & A session but I was able to do that because it was a Muslim Bengali doctor talking to a Muslim Bengali Imam …and we had that relationship. Whereas I felt, like, if I did that with the Sikh community, it wouldn’t be as authentic… I’d rather a Sikh doctor do that and if I could empower a Sikh doctor or empower a Black doctor to talk to the black Churches and people can have that relationship there … then that would be more meaningful and more authentic … because otherwise it would be pretty much the same as a white doctor [talking to them]. The authenticity would be fabricated.(London 3; 12: 6–13; cf. Caselli et al. 2024, p. 201)

4. Conclusions

In a review on the ‘margins of the state’, the cultural anthropologist, Lisa Stevenson, suggests that in order to observe the state ‘not as a transparent and rational bureaucratic form’ but as ‘state practices that run through everyday life at the margins’, the observer needs to be able ‘to hold open the space between law and its application long enough to glimpse the structures and forces which are at play’ (Stevenson 2007, pp. 140, 144). In line with this approach, we have attempted to use ‘sociological forensics’ in order to understand the last line or street-level unfolding of ‘state capacity’ in the sense of Fukuyama (2013) and Bardhan (2022), viz. the capacity to deliver public services to all sections of the population during a crisis in order to foster social cohesion. We have sought to ‘open the space’ between ‘state capacity’ and ‘community capacity‘ in order to show their complementary character and how the potential for societal resilience might emerge between these two.

We do not suggest, however, that this interplay is always cooperative. We have seen that where we find elements of a functioning ‘urban culture of cooperation’ (Schönwälder 2020), power relationships also operate together with competition about how to achieve social cohesion through the distribution of resources and how to define cohesion in the first place. We have also seen—and this was initially not our intention but indicates the open and exploratory character of qualitative social research—that ‘layered resilience’ is not just a question of different actors and their strategies at micro-, meso-, and macro-levels. It also involves overlapping, intersecting, and sometimes contradictory modes of resilience. In this respect, the crucial insight from our research might be that resilience in terms of a functioning ‘urban culture of cooperation’ will not necessarily foster resiliency as the capacity to address the future in a self-persevering mode with a transformative outlook. Where this culture of cooperation does not exist or exists only in rudimentary ways, social elasticity can be promoted by ’social brokers’ (Blanchet et al. 2017) and this keeps society from slipping into anomic disorder.

Our study suggests the need for more empirically grounded investigations into the continuity and difference between adaptation and adjustment, normality and normalcy, as well as resilience and resiliency, especially the latter distinction between ‘resiliency’ as ongoing social maintenance work and ‘resilience’ as additional effort in times of crisis, as it might turn out to be a crucial heuristic device to detect the patterns of ‘social elasticity’ in an age of catastrophe and disruption (cf. Elliott and Turner 2012, pp. 165f., 171).

The study also highlights the importance of context-specific and path-dependent notions of resilience and resiliency. The comparison between the ‘ordinary’ city and the ‘global’ city’ as well as the ‘post-migrant’ and the ‘post-industrial’ context through our research in Stuttgart and London has indicated a significant difference in the roles played by various stakeholders. It has also shown that their engagement with the migrant community and local council through a dense web of ‘structuration’ follows, in Stuttgart, the ideal of ‘integrationism’ while this engagement is forged in London through the relationship between an ethnic community and a strong institution (NHS).

Two modes of resilience-related trust, therefore, emerged during the pandemic: ‘patterned trust’ in the dense integrative structure of Stuttgart, as opposed to ‘borrowed trust’ based on the ad hoc mediation between local state and migrants via social brokers. This suggests that further research should pay close attention to the entities that define and claim ‘resilience’ or ‘resiliency’ for that matter (cf. Endress 2015, p. 540). It also needs to always carefully address the crucial empirical question—‘resilience to what?’ (Mu 2020, p. 4)—because resilience in times of crisis and even more so ‘resiliency’ in times of the ordinary is fundamentally based on the relationship of power between a larger (more powerful) and smaller (subordinate) social unit. To put it more simply, societal resilience is ultimately a question of functioning subsidiarity.

Author Contributions

Introduction: Conceptualizing Social Resilience, J.D. and J.E.; Research Design and Methods: Forensic Sociology and Travelling Ethnography, J.D. and J.E.; Material and Discussion, J.D. and J.E.; Conclusions, J.D. and J.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research draws on the research project funded by Volkswagen Stiftung—“VW A 134118—Corona and Beyond”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of University of Roehampton (protocol code SSC 21/039 on 16 August 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

The interviewees have been informed about aims and objectives of the research, have been asked to which extent they wish to be anonymized in latter texts using interview sequences, and have been handed over a complete transcript of the interview.

Data Availability Statement

Interview data are subject to individual (non-experts) and institutional (experts) requests for privacy/anonymity which are not available in a trusted repository. Selected interview material can be made available to interested researchers upon formal request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the useful comments made by the academic reviewers.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 | We prefer to use this term in order to acknowledge that many of those to whom everyday language conventionally refers to as ‘migrants’ do not have a personal migration experience. We occasionally also refer to ‘ethnic minority groups’ when contextually appropriate. In doing so, we are aware of the ‘tenacity’ of an ‘ethnic lens’ approach in terms of concealing some of ‘the diversity that lies within a population labelled as “ethnic group”’, while at the same time we believe that our argument gives sufficient space to indicate ‘the constructed nature of ethnic identities and ethnic group boundaries’, and especially to the importance of their embeddedness into ‘the heterogenous social fabric of [different] cities’ (Glick Schiller and Çağlar 2009, p. 184). Similarly, when referring to a resident population with migrant background, it is not our intention to reify cultural differences but to highlight differentiation in structural access to opportunity, notably access to crucial information and public services during a pandemic crisis. In other words, we use this term as a heuristic device rather than a means to invoke an ontological divide between a national ‘us’ and a migrant ‘them’ (cf. Yildiz 2022). |

| 2 | This is short for Turkish Islamic Union for Religious Affairs, one of the largest umbrella organizations of Turkish Islam in Germany. |

| 3 | The difference in balance between expert and non-expert interviews can be explained by two factors. One refers to the respective research strategies pursued in London and Stuttgart in terms of locating the interviews, i.e., starting with lay people or experts. The other reflects the ambivalences inherent to the definition of ‘expert’ and ‘expert knowledge’ in the method literature itself (e.g., Döringer 2021), and the difficulties that follow from it in terms of an ‘travelling ethnography’ between two cities embedded in two overlapping yet nevertheless not congruent scientific traditions of empirical research. So, for example, while the London research team viewed community activists as ‘experts’, the Stuttgart team considered civil society activists as ‘non-experts’ due to their lack of clear institutional function and related access to specific knowledge modes. |

| 4 | Some of the interview sequences used in Section 3.1 and Section 3.2 of this article are drawn from Chapter 2, 3, and 8 of our book. The interested reader will find them discussed in more depth and length there (cf. Caselli et al. 2024). For reasons of transparency, we shall give the respective page references after the interview quotes where this applies. We acknowledge the courtesy of Palgrave Publishers in allowing the reuse of those sections. The interview quotes themselves are referenced in the Text as follows: e.g., for the Stuttgart case study: (Stuttgart 2; 7: 1–5; our emphasis)—can be decoded as: second Stuttgart interview; p. 7: line 1–5; italics to highlight emphasis of meaning within the quote. |

References

- Alexander, Jeffrey C., and Philip Smith. 2003. The strong program in cultural sociology: Elements of a structural hermeneutics. In The Meanings of Social Life. Edited by Jeffrey C. Alexander. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 11–26. [Google Scholar]

- Ambrosini, Maurizio, and Paolo Boccagni. 2015. Urban Multiculturalism beyond the Backlash: New Discourses and Different Practices in Immigrant Policies across European Cities. Journal of Intercultural Studies 36: 35–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appadurai, Arjun. 2003. Illusion of Permanence: Interview with Arjun Appadurai. Perspecta 34: 44–52. [Google Scholar]

- Appadurai, Arjun. 2013. The Future as Cultural Fact: Essays on the Global Condition. London: Verso. [Google Scholar]

- Bardhan, Pranab. 2022. A World of Insecurity: Democratic Disenchantment in Rich and Poor Countries. Harvard: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Blanchet, Karl, Sara L. Nam, Ben Ramalingam, and Francisco Pozo-Martin. 2017. Governance and Capacity to Manage Resilience of Health Systems: Towards a New Conceptual Framework. International Journal of Health Policy and Management 6: 431–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caselli, Marco, Jörg Dürrschmidt, and John Eade, eds. 2024. Migrants (Im)Mobilities in Three European Contexts: Global Pandemic and Beyond. London: Palgrave. [Google Scholar]

- Chriss, James J. 1992. Review: How Is Society Possible? Intersubjectivity and the Fiduciary Attitude as Problems of the Social Group in Mead, Gurwitsch, and Schuetz by Steven Vaitkus. Contemporary Sociology 21: 283–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitriadis, Iraklis, Minke H. J. Hajer, Elena Fontanari, and Maurizio Ambrosini. 2021. Local “Battlegrounds”: Relocating Multi-Level and Multi-Actor Governance of Immigration. Revue Européenne des Migrations Internationales 37: 251–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dollmann, Jörg, and Irena Kogan. 2021. COVID-19–associated discrimination in Germany. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility 74: 100631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Döringer, Stefanie. 2021. The problem-centred expert interview. Combining qualitative interviewing approaches for investigating implicit expert knowledge. International Journal of Social Research Methodology 24: 265–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, Anthony, and Bryan S. Turner. 2012. On Society. Cambridge: Polity. [Google Scholar]

- Emilsson, Henrik. 2015. A national turn of local integration policy: Multi-level governance dynamics in Denmark and Sweden. Comparative Migration Studies 3: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endress, Martin. 2015. The Social Constructedness of Resilience. Social Science 4: 533–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuyama, Francis. 2004. State Building: Governance and World Order in the 21st Century. New Nork: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fukuyama, Francis. 2013. What is Governance? Centre for Global Development Working Paper 314: 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Fukuyama, Francis. 2020a. The Pandemic and Political Order: It Takes a State. Foreign Affairs. July/August, pp. 1–9. Available online: https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/world/2020-06-09/pandemic-and-political-order (accessed on 3 January 2022).

- Fukuyama, Francis. 2020b. The Thing that Determines a Country’s Resistance to the Coronavirus. The Atlantic. March 30. Available online: https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2020/03/thing-determines-how-well-countries-respond-coronavirus/609025/ (accessed on 17 June 2025).

- Geißler, Rainer. 2004. Einheit-in-Verschiedenheit: Die interkulturelle Integration von Migranten—Ein humaner Mittelweg zwischen Assimilation und Segregation. Berliner Journal für Soziologie 14: 287–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giddens, Anthony. 1993. Modernity and Self-Identity: Self and Society in the Late Modern Age. Cambridge: Polity. [Google Scholar]

- Glick Schiller, Nina, and Ayşe Çağlar. 2009. Towards a Comparative Theory of Locality in Migration Studies: Migrant Incorporation and City Scale. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 35: 177–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, Claudia, Susanne Luedtke, Neil Spicer, Jens Stilhoff Sörensen, Susannah Mayhew, and Sandra Mounier-Jack. 2021. National health governance, science and the media: Drivers of COVID-19 responses in Germany, Sweden and the UK in 2020. BMJ Global Health 2021: e006691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartley, Kris, and Darryl S. L. Jarvis. 2020. Policymaking in a Low-trust state: Legitimacy, State Capacity, and Responses to COVID-19 in Hong Kong. Policy and Society 39: 403–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Homberger, Adrienne, Maren Kirchhoff, Marie Mallet-Garcia, Ilker Ataç, Simon Güntner, and Sarah Spencer. 2022. Local Responses to Migrants with Precarious Legal Status: Negotiating Inclusive Practices in Cities Across Europe. Zeitschrift für Migrationsforschung—Journal of Migration Studies (ZMF) 2: 93–116. [Google Scholar]

- Inglis, Tom. 2010. Sociological Forensics: Illuminating the Whole from the Particular. Sociology 44: 507–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimmelmann, Michael. 2015. Stuttgart Struggles to House the Migrants it Embraces. New York Times, October 6. [Google Scholar]

- Lewicki, Aleksandra. 2018. Race, Islamophobia and the politics of citizenship in post-unification Germany. Patterns of Prejudice 52: 496–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurović, Ivana, Linda Liebenberg, and Martina Ferić. 2020. A Review of Family Resilience: Understanding the Concept and Operationalization Challenges to Inform Research and Practice. Child Care in Practice 26: 337–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGhee, Derek, Chris Moreh, and Athina Vlachantoni. 2017. An “undeliberate determinacy”? The changing migration strategies of Polish migrants in the UK in times of Brexit. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 43: 2109–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier-Braun, Karl-Heinz. 2009. Zuwanderung seit 30 Jahren als Chance und Bereicherung: Die Integrationspolitik der Landeshauptstadt Stuttgart gilt bundesweit als vorbildlich. In Lokale Integrationspolitik in der Einwanderungsgesellschaft: Migration und Integration als Herausforderung von Kommunen. Edited by Frank Gesemann and Roland Roth. Wiesbaden: VS, pp. 367–82. [Google Scholar]

- Mu, Guanglun M. 2020. Sociologising resilience through Bourdieus field analysis: Misconceptualisation, conceptualisation, and reconceptualization. British Journal of Sociology of Education 42: 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieswand, Boris. 2021. Konturen einer Moralsoziologie der Migrationsgesellschaft. Zeitschrift für Migrationsforschung/Journal of Migration Research 1: 75–95. [Google Scholar]

- Obrist, Brigit, Constanze Pfeiffer, and Robert Henley. 2010. Multi-layered social resilience: A new approach in mitigation research. Progress in Development Studies 10: 283–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penninx, Rinus, Karen Kraal, Marco Martinello, and Steven Vertovec. 2020. Citizenship in European Cities: Immigrants, Local Politics and Integration Policies. London: Routledge. First Published in 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Schönwälder, Karen. 2020. Diversity and political practice. Ethnic and Racial Studies 43: 1929–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schönwälder, Karen, and Triadafilos Triadafilopoulos. 2012. A Bridge or Barrier to Incorporation? Germanys 1999 Citizenship Reform in Critical Perspective. German Politics & Society 30: 52–70. [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson, Lisa. 2007. Review: Anthropology in the Margins of the State. PoLAR (Political and Legal Anthropology Review) 30: 140–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockton, Isabel, and Max Warner. 2024. IFS Report R294: Ethnic Diversity of NHS Doctors. The Institute for Fiscal Studies. Available online: https://ifs.org.uk/sites/default/files/2024-01/IFS-Report-R294-Ethnic-diversity-of-NHS-doctors%20%281%29.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Triandafyllidou, Anna. 2020. Spaces of Solidarity and Spaces of Exception at the Times of COVID-19. International Migration 58: 261–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triandafyllidou, Anna. 2022. Spaces of Solidarity and Spaces of Exception: Migration and Membership During Pandemic Times. In Migration and Pandemics. Edited by Anna Triandafyllidou. IMISCOE Research Series; Liège: IMISCOE, pp. 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Campenhout, Gijs, and Henk van Houtum. 2021. “I am German when we win, but I am an immigrant when we lose.” Theorising on the deservedness of migrants in international football, using the case of Mesut Özil. Sport in Society 24: 1924–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vertovec, Steven. 2020. Global Migration and the “Great Reshaping”. Max Planck Research 3: 20–25. [Google Scholar]

- Yildiz, Erol. 2022. RfM Debatte: Anstelle des Migrationshintergrundes—Eingewanderte Erfassen. Berlin: Rat für Migration. Available online: https://rat-fuer-migration.de/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/Kommentar-RfM-Debatte-2022-Erol-Yildiz-Die-Debatte-u%CC%88ber-den-Migrationshintergrund-aus-einer-postmigrantischen-Perspektive-weitergedacht.pdf (accessed on 23 May 2023).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.