The Culture of Romance as a Factor Associated with Gender Violence in Adolescence

Abstract

1. Introduction

The enduring nature of gender-based violence as the primary violation of women’s human rights compel public authorities to persistently advance the recognition of rights and the development of public policies aimed at eradicating this sexist violence in all its forms. The global feminist movement, as the principal driving force behind this social change, has historically generated successive waves of democratic progress with positive effects on the construction of a more egalitarian society. Particularly since the 1995 Beijing Conference, it has successfully placed the struggle against discrimination and gender-based violence on the international public agenda. The conceptualization of violence against women as an extreme manifestation of gender inequalities and as a violation of human rights has led to the enactment of legislation which, in the cases of Spain and Andalusia, has represented an undeniable step forward by reducing impunity in intimate partner and former partner relationships, as well as by bringing to light other forms of male violence encompassed within the evolving definition of gender-based violence. Nevertheless, these legislative advances remain insufficient, as underscored by the feminist movement, which has placed on the political agend not only the prioritization of victim protection, but also the need for a deeper examination into the structural causes of violence and those who perpetrate it.

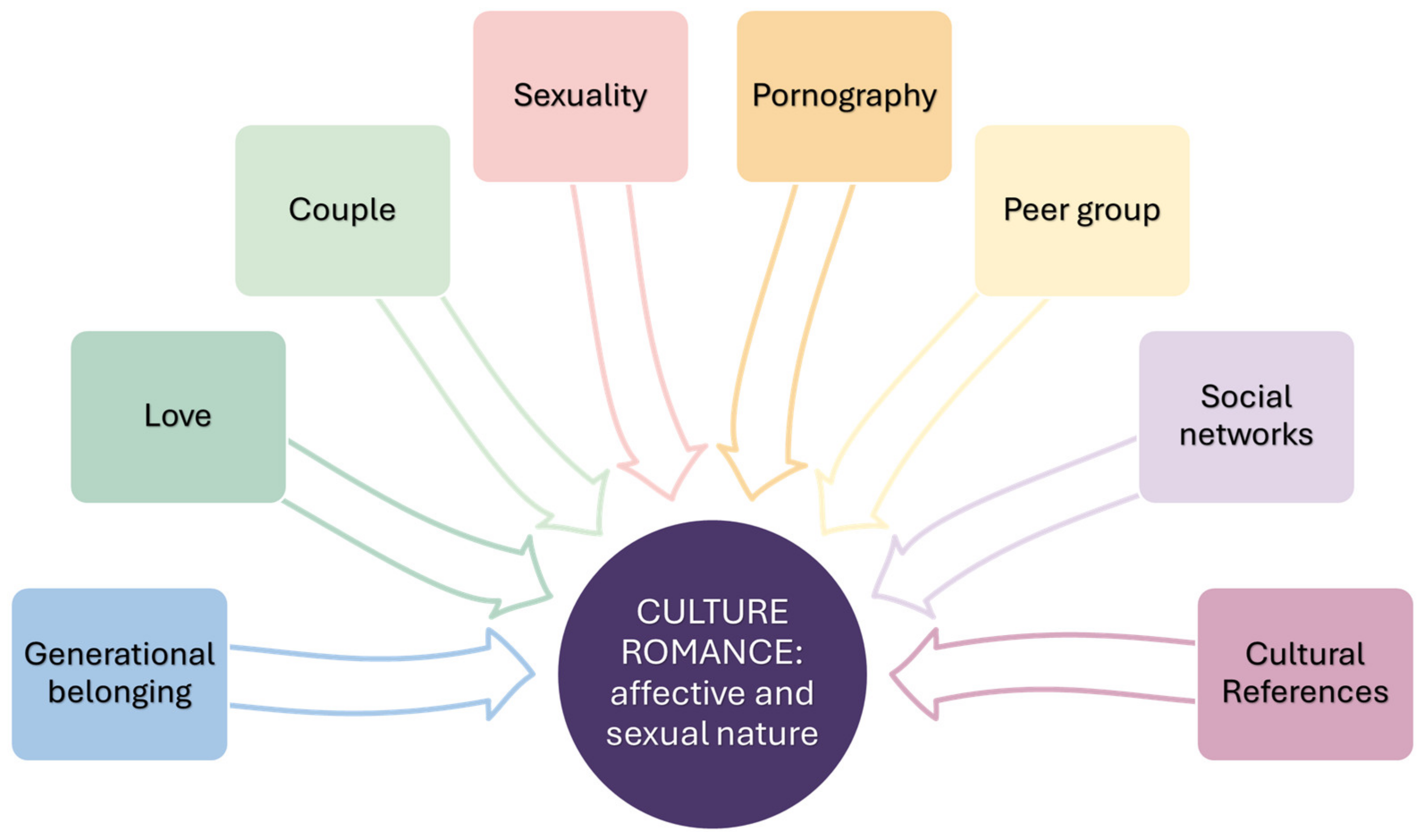

2. Theoretical Framework: The Culture of Romance

2.1. Dimensions of Adolescent Romance

2.1.1. Love

2.1.2. Partner

2.1.3. Sexuality

2.1.4. Pornography

2.1.5. Peer Group

2.1.6. Cultural References

2.1.7. Social Networks

3. Materials and Methods

- Romantic Partner:

- Psychological violence: control, jealousy, devaluation, and partner isolation.

- Physical violence: direct aggression and threats of harm.

- Sexual violence: coercion and control over the partner’s sexuality.

- Digital violence: cyberbullying, surveillance of personal devices, and non-consensual sharing of intimate content.

- Abusive relationship dynamics (commonly referred to as “toxic relationships” by adolescents): emotional dependence, manipulation, and instability.

- Sexuality:

- Homophobia and transphobia.

- Machismo and the reinforcement of patriarchal norms.

- Gender-differentiated socialisation processes that shape expectations and behaviours.

- Love:

- Idealisation of romantic love.

- Confusion between love and control, often expressed through possessive gestures.

- Abusive dynamics rooted in emotional manipulation.

- Emphasis on physical attractiveness aligned with dominant beauty standards.

- Peer Group:

- Central role of friendships in adolescents’ lives.

- Social pressure and peer influence, especially around sexual behaviour.

- Bullying and intra-group conflicts.

- Functioning as a support network during difficult experiences.

- Pornography:

- Age of first exposure.

- Uses, including practices like sexting.

- Discourses around its influence—ranging from denial to acknowledgment.

- Distortion of sexual reality and creation of unrealistic expectations.

- Reproduction of behaviours seen in pornographic content.

- Issues of consent.

- Recognition of potential positive effects when consumed critically.

- Cultural References:

- Types of media consumed: music, series, films, etc.

- Popular musical genres among youth.

- Lyrical content that often includes misogyny, machismo, and violence.

- Idealisation of love and reinforcement of traditional gender roles and stereotypes.

- Social Media:

- Daily usage time.

- Most frequently used platforms.

- Purposes of use: flirting, socialisation, harassment, etc.

- Predominant types of content: sexual, entertaining, and humorous, among others.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Love Dimension

ESEPUUHHE10: My prototype, my perfect prototype is blonde with blue eyes, but…

Researcher: Wow, you’re sure about that! But what?

3ESEPUUHHE10: But right now… They’re not kind, or they don’t have empathy and stuff, so honestly, no.

3ESEPUUHHE5: That they’re pretty.

Researcher: Pretty. What else?

3ESEPUUHHE5: That’s it. What do you need more for?

4.2. Sexuality Dimension

FPGMCO1PURHHE1: For sexuality, well… man and woman, basically gender, what a person is. I’m a man and there are… men and women, that’s it.

FPGMCO1PURMHE11: Sexuality, well, what defines us as men and women, (…) or the relationship between men and women, right?

3ECAPUUHHE7: Well, that stuff about gender identity and all that doesn’t really sit right with me, because I’m… Christian, so it would be like… God only made two sexes. Man and woman. But the world has gone… [in a different direction].

4EHPURHHO1: What’s politically correct is to be straight. What happens is, of course, since you have to fit into society somehow, you look for your own little things, right?

4EHPURHHO1: You know what the thing is? That we, my class, me… I’m gay. A classmate, she’s a lesbian… So she and I are giving visibility to this world in my class. That we’re not outsiders, we’re here, in this society. And every time we give a talk… well, not a talk, every time we do a presentation… (…) I’ve always done a presentation on homophobia, and she’s always done one on transphobia. Because it’s not just about giving visibility to gays and lesbians, no. (…) There are queers, there are people…

3ECAPUUMHE6: Right, isn’t it? Because you have to be clear about what you like, who you are, because if you’re not clear, you go through life blind, right? You don’t even know yourself, and you think you do, but you really don’t.

FPGMMCAPUUMHE4: I had a partner who, when I didn’t want to… do it, he’d hit me (…) He was fifteen and I was sixteen. And… I didn’t want to, and that went on for five or six months. And I got fed up, I told my mother and my sister and they really went for him. Anyway, when I broke up with this guy, I talked to him. Because I thought I had changed, but no way, in the end…

3ESEPUUMHE1: Like, the thing is, me, I haven’t… I haven’t done it, but once a boy was, we were in a parking lot and he forced me to… to suck him off.

4.3. Couple Dimension

4EMA2PUUHHO1: Well, a toxic relationship, a partner who controls you, controls your passwords, controls where you go, controls who you go with…

2EGR1PUUMHE6: He controlled absolutely everything. Where are you going, what are you doing, send me a photo of who you’re with, your WhatsApp conversations, your Instagram conversations, give me your password. (…) We lasted nine months. (…) Well, even so, I was, I don’t know, I was okay. (…) My mother is the one who saved me, honestly, from that. If not, he’d still be telling me he’s going to hit me.

3EAL1PUUMHE1: I start looking at the book and I don’t read… It’s that I miss a lot of class because I’ve also been mentally awful because of my boyfriend (…) Ugh, he messes everything up (…) That person takes so much away from me.

2EGR1PUUMHE1: I met a boy who ruined my life (…) he was my first love. But I don’t know if it was love, if it was obsession or something… emotional instability. (…) I had a really bad time (…) I didn’t go to school [I repeated a year] (…) what’s the point of going to school if it’s no use to me (…) I said: I prefer to stay like this [maintain the abusive relationship] rather than [be without him].

4.4. Cultural References Dimension

3EAL2PUUHBI1: I’ve been very much in love, and to me, love seems… I’m super thoughtful with details, I love things that are, like, passionate, I love romance movies and I like the concept of love, they paint it so beautifully.

3ECAPUUHHE2: For example, Pablo Escobar grabs the woman he wants, screws her over, and then shoots her and kills her.

FPGMCAPUUHHE19: It could be, yeah, in Toy Boy there’s quite a bit of machismo, to be honest. They hit women and all that.

4.5. Pornography Dimension

“It might be at 9 years old.”(2EGRA1PUUHHE3)

“When I was 12 years old I was taught it on a cell phone.”(3EGR3PRRHHE5)

“12 years old or so. So I kind of talked about it with my friends when I was older, this year, and we all talked about it because I thought about it and said ‘mother, I was too little’. And all my environment too…”(4EGR2PUUMHE7)

4ECO2PUUHHE6: “I’d say it’d be like… the videos that people record, so to speak, for other people to see.”

2EGR1PUUMHE12: “I’ve been told that, for example, one person sent a photo to another person, and that person then took it and sent it to everyone, and from that person, from other people, it went to even more people. But that didn’t happen to me. Come on, if they did that to me, I’d directly block them and say: don’t talk to me.”

3EJ1PURMHE12: “…well, I don’t know. I’d say… That I also don’t see it as influencing… Something negative, for example, watching videos of two people having sexual relations. Especially because it’s typical now for teenagers who have their hormones going crazy, so normally they always try to satisfy their hunger in some way, so to speak. So I also don’t see it as something negative to watch those things. It is true that it may have affected someone, in one way or another.”

2EGR1PUUHHE1: “Of course, well, it depends on the person. For example, it doesn’t influence me at all, like… Me… I can watch and I know perfectly well that maybe it’s not like that (…) they do that for themselves, to earn money first (…) sexual relations aren’t like that. But many people, it’s normal, it’s the most normal thing in the world, for them to think it’s like that. Because if you see something, that’s how it is, you see it and… Well, it’s normal to think it’s like that.”

3EAL1PUUHHE3: “It definitely affects some, because they see it and they think… They want to do the same as in the videos.”

3ECAPUUMHE2: “Yes, because maybe you watch a video and you can get ideas from that video. For example, for… for doing things, you can look at the videos and then do it in real life.”

3ECAPUUHHE2: “Well, actually yes, because the first time you see that is going to be in porn. So you take a reference from that and you say: damn, so that’s how I have to do it. But really that can, it can… you know? It can confuse you.”

3EAL1PUUMHE8: “There’s a power dynamic, I think. Normally, I think the man kind of dominates the woman.”

3AJ1PURMHE2: “Of course, it’s that they think, they think that porn is sex education, but no, it’s not sex education, mmm, and it doesn’t teach you anything, basically, uh… What they teach you is how to do it, how to devalue a woman, how not to take women into account in sexual relations, and most porn scenes are rape, because at no point is the woman or the treatment of the woman taken into account.”

2EGR1PUUHBI1: “I don’t think so, because I don’t know, it’s like women are always going to be on the bottom, because in pornography I’ve always seen women treated as if they were a sack with holes […].”

2GR1PUUMHE13: “For me, it’s really bad for kids. For me, it’s… something that shouldn’t exist, I’m telling you like this because… my god, you see… Things have happened to me… kids have even written to me saying: I’d get you on all fours, I want to hit you, I don’t know what. No, man, because… because they’ve seen that. And I think that’s wrong, because for me porn is a lot of violence, it’s… I think women have a bad time, women and… and maybe men, well, men… so-so, but… it’s just bang, bang, bang all the time, so for me it’s… something that shouldn’t, why? Because kids learn it, so they see that in terms of… of… when they go to do… the thing about sexuality and that, they’re going to want to do what… what they’ve seen, so really bad, why? Because it hurts girls and everything and it’s like… no. The same thing too, I don’t know. It depends on tastes.”

“That’s very important because…I don’t…I don’t see well if they tell you no, is that no, and no…you don’t have to force anyone or anything.”(2EGR1PUUHHE4)

“If you didn’t see that you would treat your partner better and not force her to do things she doesn’t want to do.”(2EGR1PUUHHE7)

2EGR1PUUMBI1: “If they need that, it’s because they need some answers. (…) I think that because in those families they don’t talk about it, it’s not… normalized. Well… I mean, there are parents who find it more logical that (…) their children see people killing each other, for example (…) than suddenly a series comes out that’s more sexual or whatever, right? So because it’s not discussed, because it’s still a very taboo subject.”

4EHPURHHO1: “I didn’t know how to hook up, and I also didn’t know what two guys did as a couple because I had no idea, so to find out. To find out what happens, how they do it, what you have to do, so… (…) I looked it up. Exactly, if my parents haven’t taught me…”

4.6. Social Networks Dimension

2ESEPUUMHE6: “I stop spending time with my family because of social media, I stop doing my homework because of social media… (…) Come on, the other day it popped up on my phone, because I have an iPhone too, and it said: your number of I don’t know what has increased by nine hours.”

3ESEPUUMBI1: “No, not on the internet. You… women are usually seen as inferior, so to speak.”

FPGMSEPUUMHE7: “Yes, it depends, because… maybe, yes, there are more women who are submissive, so to speak, it’s always, almost always men. Also, obviously, well, there are dominant women, but… it’s not as common as the other way around.”

FPGMHPURHHE1: “Man, let’s see, before the village idiot stayed in the village, now the village idiot has Instagram and talks to anyone, and I, for example, see it especially with girls that I talk to and stuff, that there are some who, there are certain people who end up harassing them while trying to flirt or who are net fishing, just randomly starting things…”

4.7. Peer Group Dimension

3ECAPUUMHE1: “Because, well, always… my cousin, for example, my cousin who’s in my class too… has been with her boyfriend for over a year, me… everything, I mean, when she started with her boyfriend, I had never been with any boy or anything, and… that’s when… she would tell me everything and I’d find out.”

3EAL2PUUHHE3: “We’re always talking about, well, this girl is hot or this girl is hot… anyway, yeah, we do talk about it from time to time.”

2EGR1PUUMHE1: “And I started hanging out with people I shouldn’t have. People who were a bad influence on me. Who messed with my head or… I had my typical group of friends, who I got along with, I wasn’t going down a bad path or anything, and after everything I went through, I started hanging out with people like that. I also got into a lot of things that messed me up badly too. I met a boy who ruined my life, so to speak, because he was my first love, so to speak. But I don’t know if it was love, if it was obsession or something… emotional instability. And… well, I… I had a very bad time, uh… I didn’t know what to do, what not to do. I didn’t want to; I didn’t go to school…”

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | In Spanish, Observatorio Estatal de Violencia contra la Mujer. See, in particular, the historical data broken down by Autonomous Community, website: https://violenciagenero.igualdad.gob.es/violenciaEnCifras/victimasMortales/fichaMujeres/home.htm (accessed on 3 May 2025). |

| 2 | In Spanish: Ley 7/2018, de 30 de julio, por la que se modifica la Ley 13/2007, de 26 de noviembre, de medidas de prevención y protección integral contra la violencia de género (Spain 2018). |

| 3 | Project title: “La caja negra del fracaso escolar. Análisis de las trayectorias de éxito/fracaso escolar en Secundaria Obligatoria desde la perspectiva de las relaciones afectivosexuales adolescentes en la actual sociedad andaluza digital” (“The Black Box of School Failure: An Analysis of Academic Success/Failure Trajectories in Compulsory Secondary Education from the Perspective of Adolescent Affective-Sexual Relationships in the Contemporary Digital Andalusian Society”). Acronym: ROMANCE SUCC-ED. Funded through a competitive call (Resolución de 5 de febrero de 2020) issued by the Rector of University of Granada, under the regulatory framework for R&D&I project grants of the Andalusia ERDF Operational Programme 2014–2020 (Programa Operativo FEDER Andalucía 2014–2020) (BOJA no. 30—Thursday, 13 February 2020). Reference: B-SEJ-332-UGR20. Participating institutions: University of Granada (Granada and Melilla campuses), University of Almería, University of Jaén, University of Valencia, University of Porto (Portugal), Nottingham Trent University (United Kingdom), and University of Sassari (Italy). Duration: 1 July 2021–30 June 2023. |

References

- Adán, Carme. 2019. Feminicidio: Un nuevo orden patriarcal en tiempos de sumisión [Feminicide: A New Patriarchal Order in Times of Submission]. Barcelona: Bellaterra. [Google Scholar]

- Alonso, Patricia, María Sande, and Bibiana Regueiro. 2022. Pornography and Adolescents: The Danger of Confusing Power and Pleasure. Sex Education as an Answer. Journal of Studies and Research in Psychology and Education 9: 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amurrio, Milagros, Ane Larriaga, Elisa Usategui, and Ana Irene del Valle. 2010. Gender Violence in the Couple Relationships of Adolescents and Young Adolescents in Bilbao. Zerbitzuan: Gizarte Zerbitzuetarako Aldizkaria = Social Services Journal 47: 121–34. [Google Scholar]

- Aran-Ramspott, Sue, Oihane Korres-Alonso, Iciar Elexpuru-Albizuri, Álvaro Moro-Inchaurtieta, and Ignacio Bergillos-García. 2024. Young users of social media: An analysis from a gender perspective. Frontiers in Psychology 15: 1375983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arriaga, Ximena B., and Vangie A. Foshee. 2004. Adolescent Dating Violence: Do Adolescents Follow in Their Friends’ or Their Parents’ Footsteps? Journal of Interpersonal Violence 19: 162–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arruzza, Cinzia, Tithi Bhattacharya, Nancy Fraser, and Clara Ramas. 2019. Manifesto of a Feminism for the 99%. Madrid: Editorial Traficantes de Sueños. [Google Scholar]

- Ballester, Lluís, Carmen Orte, and Carlos Rosón. 2022. A Survey Study on Pornography Consumption among Young Spaniards and Its Impact on Interpersonal Relationships. Net Journal of Social Sciences 10: 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballester, Lluís, María Dosil, Alejandro Villena, and Giulia Testa. 2023. La Nueva Pornografía ‘Online’ y los Procesos de Naturalización de la Violencia Sexual. In Una Mirada Interdisciplinar Hacia las Violencias Sexuales. Barcelona: Octaedro, pp. 233–50. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, Albert. 1977. Social Learning Theory. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Barragán-Medero, Fernando, and David Pérez-Jorge. 2020. Combating Homophobia, Lesbophobia, Biphobia and Transphobia: A Liberating and Subversive Educational Alternative for Desires. Heliyon 6: e05225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, Nancy. 2019. How to Make Things with Pornography. Norway: Chair. [Google Scholar]

- Bem, Sandra L. 1981. Gender schema theory: A cognitive account of sex typing. Psychological Review 88: 354–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, Bruce L. 2001. Qualitative Research Methods for the Social Sciences. Boston: Allyn and Bacon. [Google Scholar]

- Bisquert-Bover, Mar, Cristina Giménez-García, Beatriz Gil-Juliá, Naiarra Martínez-Gómez, and María Dolores Gil-Llario. 2019. Romantic love myths and self-esteem in adolescents. International Journal of Developmental and Educational Psychology: INFAD 5: 507–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonilla-Algovia, Enrique, Esther Rivas-Rivero, and Isabel Pascual. 2021. Myths of romantic love in adolescents: Relationship with sexism and variables from socialization. Education XX1: Journal of the Faculty of Education 24: 441–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bright, Susie. 1992. Susie Bright’s Sexual Reality: A Virtual Sex World Reader, 1st ed. San Francisco: Cleis Press. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, Judith. 2007. Gender in Dispute: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. Translated by Marta Cornu. Barcelona: Paidós. First published 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Casey, Erin A., and Taryn P. Lindhorst. 2009. Toward a Multi-Level, Ecological Approach to the Primary Prevention of Sexual Assault. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse 10: 91–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connell, Raewyn. 2005. Masculinities, 2nd ed. Cambridge: Polity Press. First published 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Connell, Raewyn, and James Messerschmidt. 2005. Hegemonic Masculinity: Rethinking the Concept. Gender & Society 19: 829–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowie, Celia, and Sue Lees. 1981. Slags or Drags. Feminist Review 9: 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Aguado, María José. 2005. La Violencia Entre Iguales En La Adolescencia Y Su Prevención Desde La Escuela. Psicothema 17: 549–58. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Aguado, María José, Rosario Martínez, Javier Martín, María Isabel Carvajal, and María Jesús Peyró. 2010. Igualdad y Prevención de la Violencia de Género en la Adolescencia: Principales resultados del estudio realizado en centros educativos de educación no universitaria en el marco de un convenio entre la Universidad Complutense y el Ministerio de Igualdad. Ministry of Equality. Available online: https://www.inmujeres.gob.es/publicacioneselectronicas/documentacion/Documentos/DE0138.pdf (accessed on 4 April 2025).

- Díez-Gutiérrez, Enrique-Javier, Eva Palomo-Cermeño, and Benjamín Mallo-Rodríguez. 2023. Education and the reggaetón genre: Does reggaetón socialize in traditional masculine stereotypes? Music Education Research 25: 136–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donoso, Trinidad, José Rubio, and Ruth Vilà. 2018. La Adolescencia Ante la Violencia de Género 2.0: Concepciones, Conductas y Experiencias. Education XX 1: 109–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyer, Richard. 2002. Coming to Terms: Gay Pornography. In Only Entertainment. Edited by Richard Dyer. London: Routledge, pp. 138–48. [Google Scholar]

- Eagly, Alice H., and Wendy Wood. 2012. Social role theory. In Handbook of Theories of Social Psychology. Edited by Paul A. M. Lange, Arie W. Kruglanski and Edward Tory Higgins. London: Sage, vol. 2, pp. 458–76. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, Katie M. 2015. Intimate Partner Violence and the Rural-Urban-Suburban Divide: Myth or Reality? A Critical Review of the Literature. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse 16: 359–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, Wendy E., Janet Chung-Hall, and Tara M. Dumas. 2012. The Role of Peer Group Aggression in Predicting Adolescent Dating Violence and Relationship Quality. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 42: 487–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Expert Group on Sexuality Education. 2016. Sexuality Education—What Is It? Sex Education 16: 427–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Parliament: Directorate-General for Internal Policies of the Union, Kristien Michielsen, and Olena Ivanova. 2022. Comprehensive Sexuality Education: Why Is It Important? Strasbourg: European Parliament. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer, Victoria A., and Esperanza Bosch. 2013. From Romantic Love to Gender Violence: For an Emotional Coeducation in the Educational Agenda. Profesorado. Journal of Curriculum and Teacher Education 17: 105–22. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer, Victoria A., Esperanza Bosch, Maria Carmen Ramis, Gema Torres, and Capilla Navarro. 2006. La Violencia Contra Las Mujeres En La Pareja: Creencias Y Attitudes En Estudiantes Universitarios/As. Psicothema 18: 359–66. Available online: https://reunido.uniovi.es/index.php/PST/article/view/8442 (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- Fine, Michelle, and Sara McClelland. 2006. Sexuality Education and Desire: Still Missing After All These Years. Harvard Educational Review 76: 297–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flood, Michael. 2011. Involving Men in Efforts to End Violence against Women. Men and Masculinities 14: 358–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frezzotti, Yanina. 2024. Adolescent experiences of digital gender violence in sex-affective relationships. Revista Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales, Niñez y Juventul 22: 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frezzotti, Yanina, and Raquel Tarullo. 2024. Digital dissemination of intimate content as a form of gender violence: A qualitative study with adolescents in Argentina. Revista Prisma Social, 219–39. Available online: https://revistaprismasocial.es/article/view/5532 (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Gallego, Claudia, and Liria Fernández-González. 2019. Is pornography consumption related to intimate partner violence? The moderating role of attitudes toward women and violence. Psicología Conductual = Behavioral Psychology: International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology 27: 431–54. [Google Scholar]

- Garaizábal, Cristina. 2021. Sex in dispute: Feminist accounts of sexuality. In Alianzas rebeldes: Un feminismo más allá de la identidad. Edited by Clara Serra, Cristina Garaizábal and Laura Macaya. Barcelona: Bellaterra, pp. 123–35. [Google Scholar]

- García, Andrea, Fannella Giusti, and Silvia Jiménez Mata. 2022. Adolescence and online gender violence: A comparative literature review between Costa Rica, Mexico and Spain. Sociedad e Infancias 6: 165–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, Antonio D., Irina Salcines, Natalia González, Antonia Ramírez, and Mª. Pilar Gutiérrez. 2023. Affective and Sexual Education in the Family. Huelva: Editorial Huelva. [Google Scholar]

- Gilmartin, Shannon K. 2005. The Centrality and Costs of Heterosexual Romantic Love among First-Year College Women. The Journal of Higher Education 76: 609–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilmartin, Shannon K. 2006. Changes in College Women’s Attitudes toward Sexual Intimacy. Journal of Research on Adolescence 16: 429–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilmartin, Shannon K. 2007. Crafting Heterosexual Masculine Identities on Campus: College Men Talk about Romantic Love. Men and Masculinities 9: 530–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, Peggy, Danielle Soto, Wendy Manning, and Monica Longmore. 2010. The Characteristics of Romantic Relationships Associated with Teen Dating Violence. Social Science Research 39: 863–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glenn, Norval, and Elizabeth Marquardt. 2001. Hooking Up, Hanging Out, and Hoping for Mr. Right: College Women on Dating and Mating Today. New York: Institute for American Values. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin, Christine. 1982. Cultures of Femininity: Romance Revisited. Birmingham: Center for Contemporary Cultural Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Hammersley, Martyn, and Paul Atkinson. 2004. Ethnography: Research Methods. Barcelona: Paidós. [Google Scholar]

- Heilman, Madeline E. 2012. Gender stereotypes and workplace bias. Research in Organizational Behavior 32: 113–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, Dorothy C., and Margaret A. Eisenhart. 1990. Educated in Romance. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hormigos-Ruiz, Jaime. 2023. Normalization of Gender Violence in Cultural Content Consumed by Youth: The Case of Reggaeton and Trap. Revista Prisma Social, 278–303. Available online: https://revistaprismasocial.es/article/view/5039 (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Illouz, Eva. 2012. Why Love Hurts. Una explicación sociológica. Madrid: Katz. [Google Scholar]

- Jaldo, Yolanda. 2022. Gender Violence in Adolescence: Types of Violence, Risk Factors and Implication of the Educational Context in its Prevention. REIF: Journal of Education, Innovation and Training 6: 53–76. [Google Scholar]

- Javier-Juárez, Sandra Paola, Carlos Alejandro Hidalgo-Rasmussen, and José Carlos Ramírez-Cruz. 2023. Patterns of Violence in Adolescent Dating Relationships: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Acta Colombiana de Psicología 26: 56–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, María Jesús, and Clara López, eds. 2022. Gender violence in youth. In Las mil caras de la violencia machista en la población joven. Madrid: Instituto de la Juventud (INJUVE). Available online: https://www.injuve.es/sites/default/files/adjuntos/2022/03/revista-estudios-juventud-125.pdf (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- Jones, Sue. 1985. Depth Interviewing in Applied Qualitative Research. Aldershot: Gower. [Google Scholar]

- Kawulich, Barbara B. 2005. Participant Observation As a Data Collection Method. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung Forum: Qualitative Social Research 6: 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larrañaga, Kepa P., Mónica Monguí, Patricia Núñez-Gómez, and Celia Rangel. 2022. Main factors of gender-specific violence towards adolescent girls in the digital environment. Sociedad e Infancias 6: 123–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leen, Eline, Emma Sorbring, Matt Mawer, Emma Holdsworth, Bo Helsing, and Erica Bowen. 2013. Prevalence, Dynamic Risk Factors and the Efficacy of Primary Interventions for Adolescent Dating Violence: An International Review. Aggression and Violent Behavior 18: 159–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malamuth, Neil M., and James V. P. Check. 1981. The effects of mass media exposure on acceptance of violence against women: A field experiment. Journal of Research in Personality 15: 436–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malamuth, Neil M., Tamara Addison, and Mary P. Koss. 2000. Pornography and Sexual Aggression: Are There Reliable Effects and Can We Understand Them? Annual Review of Sex Research 11: 26–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, Jennifer. 1996. Qualitative Researching. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- McBride, Ruari-Santiago, and Dirk Schubotz. 2017. Living a Fairy Tale: The Educational Experiences of Transgender and Gender Non-Conforming Youth in Northern Ireland. Child Care in Practice 23: 292–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McRobbie, Angela. 1978. Working Class Girls and the Culture of Femininity. In Women Take Issue: Aspects of Women’s Subordination. Edited by Women’s Studies Group and Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies. London: Hutchinson, pp. 96–108. [Google Scholar]

- McRobbie, Angela, and Jenny Garber. 2006. Girls and Subcultures. In Resistance Through Rituals: Youth Subcultures in Post-War Britain. Edited by Stuart Hall and Tony Jefferson. London: Hutchinson, pp. 177–88. First published 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz, Carolina. 2024. Consumo De Pornografía Y Normalización De Conductas Violentas En Las Relaciones Sexuales De Los Jóvenes. Atlánticas. International Journal of Feminist Studies 9: 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Mantas, Laura, and Alba Sáez-Lumbreras. 2025. Sexuality Construction, Pornography, and Gender Violence: A Qualitative Study with Spanish Adolescents. Sexuality & Culture 29: 1339–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra, Noemí. 2021. Is youth lost? Youth and sexuality: Between pleasure and danger. In Alianzas rebeldes: Un feminismo más allá de la identidad. Edited by Clara Serra, Cristina Garaizábal and Laura Macaya. Barcelona: Bellaterra, pp. 123–35. [Google Scholar]

- Peter, Jochen, and Patti M. Valkenburg. 2016. Adolescents and Pornography: A Review of 20 Years of Research. The Journal of Sex Research 53: 509–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platero, Lucas, ed. 2012. Intersections: Bodies and Sexualities at the Crossroads. Barcelona: Bellaterra. [Google Scholar]

- Reisner, Sari L., Lauren M. Sava, David D. Menino, Jeff Perroti, Tia N. Barnes, Debora Layne Humphrey, Ruslan V. Nikitin, and Valerie A. Earnshaw. 2020. Addressing LGBTQ Student Bullying in Massachusetts Schools: Perspectives of LGBTQ Students and School Health Professionals. Prevention Science 21: 408–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renold, Emma, and Jessica Ringrose. 2011. Schizoid Subjectivities? Re-theorizing Teen Girls’ Sexual Cultures in an Era of ‘Sexualisation’. Journal of Sociology 47: 389–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes, Patricia, Ana Amaro, Nazaret Martínez-Heredia, and Silvia Corral-Robles. 2024. Adolescentes ante la violencia y los mitos del amor en las relaciones de noviazgo. Pedagogía Social: Revista Interuniversitaria 45: 99–113. [Google Scholar]

- Ridgeway, Cecilia L., and Shelley J. Correll. 2004. Unpacking the gender system: A theoretical perspective on gender beliefs and social relations. Gender & Society 18: 510–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rincón, Rosa Lisette. 2023. Gender-Based Violence in Adolescent Couple Relationships: Una Revisión Integral. Revista Ciencias Humanas 16: 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringrose, Jessica, and Emma Renold. 2012. Teen Girls, Working-Class Femininity and Resistance: Retheorising Fantasy and Desire in Educational Contexts of Heterosexualised Violence. International Journal of Inclusive Education 16: 461–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringrose, Jessica, Rosalind Gill, Sonia Livingstone, and Laura Harvey. 2012. A Qualitative Study of Children, Young People and ‘Sexting’: A Report Prepared for the NSPCC. London: National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez, Pilar, Francisco Villegas, and Janara Sousa. 2024. Gender effects of social network use among secondary school adolescents in Spain: Extremist and pro-violence attitudes. Feminist Criminology 19: 329–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-García-de-Cortázar, Ainhoa, Inés González-Calo, and Carmuca Gómez-Bueno. 2024. What Is the Patriarchy Doing in Our Bed? Violent Sexual-Affective Experiences Among Youth. Sexuality Research and Social Policy 22: 424–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, Gayle. 1984. Thinking Sex: Notes for a Radical Theory of the Politics of Sexuality. In Pleasure and Danger: Exploring Female Sexuality. Edited by Carole Vance. London: Routledge, pp. 267–319. [Google Scholar]

- Sanday, Peggy. 1990. Fraternity Gang Rape: Sex, Brotherhood, and Privilege on Campus. New York: NYU Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sardinha, LynnMarie, Ilknur Yüksel-Kaptanoğlu, Mathieu Maheu-Giroux, and Claudia García-Moreno. 2024. Intimate Partner Violence Against Adolescent Girls: Regional and National Prevalence Estimates and Associated Country-Level Factors. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health 8: 636–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Save the Children. 2020. Sexual Misinformation, Pornography and Adolescence. Save the Children. Available online: https://www.savethechildren.es/informe-desinformacion-sexual-pornografia-y-adolescencia (accessed on 13 April 2025).

- Spain. 2018. Law 7/2018, of July 30, amending Law 13/2007, of November 26, on Measures for the Prevention and Comprehensive Protection Against Gender Violence. BOE No. 207, August 27, 2018, 84908–84930. Available online: https://www.boe.es/eli/es-an/l/2018/07/30/7 (accessed on 4 February 2025).

- Stanley, Nicky, Christine Barter, Marsha Wood, Nadia Aghtaie, Cath Larkins, Alba Lanau, and Carolina Överlien. 2018. Pornography, Sexual Coercion and Abuse and Sexting in Young People’s Intimate Relationships: A European Study. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 33: 2919–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swahn, Monica H., Thomas R. Simon, Marci F. Hertz, Ileana Arias, Robert M. Bossarte, James G. Ross, Lori A. Gross, Ronaldo Iachan, and Merle E. Hamburger. 2008. Linking Dating Violence, Peer Violence, and Suicidal Behaviors among High-Risk Youth. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 34: 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taormino, Tristan, Celine Parreñas, Constance Penley, and Mireille Miller-Young, eds. 2012. The Feminist Porn Book: The Politics of Producing Pleasure. New York: The Feminist Press at the City University of New York. [Google Scholar]

- Tarriño, Lorena, and Mª Ángeles García-Carpintero. 2014. Adolescents and gender violence in social networks. In I+G: Aportaciones a la Investigación sobre Mujeres y Género. Seville: University of Seville, pp. 426–439. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, Steven, and Robert Bogdan. 1986. The In-Depth Interview. In Introduction to Qualitative Research Methods. Barcelona: Paidós, pp. 100–32. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. 2021. The Journey Towards Comprehensive Sexuality Education: Global Status Report. Paris: UNESCO. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Commission on the Status of Women. 2023. Report on the Sixty-Seventh Session (25 March 2022 and 6–17 March 2023). (Official Records, 2023 Supplement No. 7; E/2023/27-E/CN.6/2023/14). New York: United Nations. [Google Scholar]

- Valls, Rosa, Lídia Puigvert, and Elena Duque. 2008. Gender Violence Among Teenagers: Socialization and Prevention. Violence Against Women 14: 759–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vance, Carole, ed. 1984. Pleasure and Danger: Exploring Female Sexuality. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- van Oosten, Johanna M. F., Jochen Peter, and Patii M. Valkenburg. 2015. The influence of sexual music videos on adolescents’ misogynistic beliefs: The role of video content, gender, and affective engagement. Communication Research 42: 986–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasquez, Mandy, Marie-Ève Daspe, Beáta Bőthe, Audrey Brassard, Yvan Lussier, and Marie-Pier Vaillancourt-Morel. 2024. Associations Between Pornography Use Frequency and Intimate Partner Violence Perpetration Among Young Adult Couples: A 2-Year Longitudinal Study. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 39: 4260–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venegas, Mar. 2017. Becoming subject. A sociological approach. Convergencia Revista de Ciencias Sociales 73: 13–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venegas, Mar. 2018. The Adolescent Romance. A Sociological Analysis of Affectivosexual Politics in Adolescence. Papers 103: 255–79. [Google Scholar]

- Venegas, Mar. 2020. Masculinity as Mask: Class, Gender and Sexuality in Adolescent Masculinities. Convergencia Revista de Ciencias Sociales 27: 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venegas, Mar. 2022. Relationships and Sex Education in the Age of Anti-Gender Movements: What Challenges for Democracy? Sex Education 22: 481–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venegas, Mar. 2024a. Anti-gender Movements, CSR, and Democracy in Europe. In The Palgrave Encyclopedia of Sexuality Education. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venegas, Mar. 2024b. Comprehensive Sexuality Education: Approaching Pornography from Equality and Social Justice. International Journal of Social Justice Education 13: 41–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venegas, Mar, and José Luis Paniza, eds. 2020. La caja negra del fracaso escolar: Análisis de las trayectorias de éxito/fracaso escolar en Secundaria Obligatoria desde la perspectiva de las relaciones afectivosexuales adolescentes en la actual sociedad andaluza digital. La Paz: Alternativas Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Vélez, María Teresa. 2022. The influence of pornography on sexual relationships among young people and adolescents: An analysis of pornography consumption in Cantabria. EHQUITY. International Journal of Welfare Policy and Social Work 17: 153–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villar, Milena, María José Méndez-Lois, and Felicidad Barreiro. 2021. Gender violence in virtual environments: An approach to adolescent reality. Electronic Journal of Research in Educational Psychology 19: 509–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, Candace, and Don H. Zimmerman. 1987. Doing gender. Gender & Society 1: 125–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, Paul. 1977. Learning to Labour: How Working Class Kids Get Working Class Jobs. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. 2022. Developing Sexual Health Programmes: A Framework for Action. Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, Paul J., Robert S. Tokunaga, and Ashley Kraus. 2016. A Meta-Analysis of Pornography Consumption and Actual Acts of Sexual Aggression in General Population Studies. Journal of Communication 66: 183–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Venegas, M.; Paniza-Prados, J.L.; Romero-Valiente, F.; Fernández-Langa, T. The Culture of Romance as a Factor Associated with Gender Violence in Adolescence. Soc. Sci. 2025, 14, 460. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14080460

Venegas M, Paniza-Prados JL, Romero-Valiente F, Fernández-Langa T. The Culture of Romance as a Factor Associated with Gender Violence in Adolescence. Social Sciences. 2025; 14(8):460. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14080460

Chicago/Turabian StyleVenegas, Mar, José Luis Paniza-Prados, Francisco Romero-Valiente, and Teresa Fernández-Langa. 2025. "The Culture of Romance as a Factor Associated with Gender Violence in Adolescence" Social Sciences 14, no. 8: 460. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14080460

APA StyleVenegas, M., Paniza-Prados, J. L., Romero-Valiente, F., & Fernández-Langa, T. (2025). The Culture of Romance as a Factor Associated with Gender Violence in Adolescence. Social Sciences, 14(8), 460. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14080460