Abstract

Background: Adolescence is a key period of development characterized by emotional, cognitive, and social changes that impact positive mental health (PMH). While social support is a well-established protective factor, cognitive and emotional processes, such as cognitive fusion and regulation of distress, also play a critical role. Objective: This study aimed to examine the relationship among various cognitive (i.e., cognitive fusion), emotional (i.e., regulation of distress), and social determinants (i.e., social support) in adolescents’ PMH, as their interplay could reflect theoretical models highlighting how these factors jointly shape adolescents’ mental health. Methods. A cross-sectional study was conducted with 505 adolescents (aged 13–15 years) in Spain. Participants completed online questionnaires assessing sociodemographic variables, cognitive fusion, regulation of distress, PMH, and social support from friends. Descriptive statistics, correlation analyses, and mediation and moderated mediation models were conducted, adjusting for relevant covariates. Results: Cognitive fusion was negatively correlated with regulation of distress, PMH, and social support, whereas regulation of distress showed a positive association with both PMH and social support. Mediation analysis indicated that regulation of distress significantly mediated the relationship between cognitive fusion and PMH. Furthermore, peer support moderated this mediated relationship: higher levels of support mitigated the negative impact of regulation of distress on PMH. Sociodemographic analyses revealed that girls, non-national students, and those receiving educational support showed less favorable outcomes. Conclusions: Cognitive, emotional, and social variables jointly influence adolescents’ PMH. Emotional regulation serves as a mediator of cognitive fusion and PMH, while social support from peers mediates the impact of psychological distress. Targeted interventions should prioritize emotional regulation strategies and enhancing peer support, especially among more vulnerable groups.

1. Introduction

Adolescence represents a crucial developmental period marked by significant physical, cognitive, emotional, and social changes (Larsen and Luna 2018). These changes, including hormonal shifts, brain development, and evolving social relationships, make adolescents susceptible to both positive and negative influences on their mental well-being (Griffin 2017; Pfeifer and Allen 2021). Although adolescence has frequently been regarded as a particularly vulnerable stage of life, recent perspectives also emphasize its potential as a phase of growth and adaptability (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine et al. 2019).

From a salutogenic perspective, health is understood not only as the absence of illness but as the presence of personal and social resources that enhance individuals’ capacity to manage life’s challenges (Bauer et al. 2020; Hewis 2023; Mittelmark and Bauer 2022). Within this framework, positive mental health (PMH) emerges as a central construct. Originally conceptualized by Jahoda and developed by Lluch-Canut (1999), PMH offers a multidimensional model that includes self-esteem, emotional self-regulation, problem-solving abilities, and integration into the social and physical environment. Empirical studies have linked PMH to higher life satisfaction, improved academic outcomes, and better long-term well-being in adolescent populations (García-Moya and Morgan 2017; Renwick et al. 2022). These findings suggest that PMH serves both as a protective factor and as a critical target for early intervention and health promotion in youth populations. However, there are still few studies evaluating the effectiveness of PMH promoting programs (García-Sastre et al. 2024), so further research is needed in this area.

While PMH exhibits a broad set of strengths, certain intrapersonal processes, such as cognitive fusion, may hinder its development. Cognitive fusion refers to the tendency to become entangled with one’s thoughts, interpreting them as literal truths (Solé et al. 2015). This cognitive style can intensify emotional reactions and limit behavioral flexibility. As a core concept in Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, cognitive fusion has been linked to a range of mental health difficulties, such as anxiety, depression, and higher stress levels (Faustino et al. 2023; Krafft et al. 2019). Research has also shown that this construct predicts distress and other mental health concerns in adolescents and young adults (Bodenlos et al. 2020).

During adolescence, emotion regulation transforms from being primarily external and behaviorally driven—often supported by parents—toward more internally guided and cognitively mediated strategies. This transition is supported by the maturation of executive functions, metacognitive abilities, and abstract reasoning, which progressively enable adolescents to engage in self-regulation (Morris et al. 2017; Brinke et al. 2020; van den Heuvel et al. 2020). Moreover, recent evidence indicates that interventions aimed at improving emotion regulation during adolescence can be effective, with moderate effects on decreasing emotion dysregulation and small effects on improving emotion regulation capacity, leading to improvements in mental health outcomes (Engell et al. 2025).

Alongside cognitive and emotional processes, supportive social environments (i.e., high-quality interactions with peers and family members) not only help adolescents navigate the challenges of this stage but also contribute to the healthy formation of their personalities, including a stable sense of identity and self-esteem (Branje 2022; Ragelienė 2016; Telzer et al. 2018). However, access to social resources is not equally distributed. Research consistently demonstrates that variables such as gender, family structure, socioeconomic status, migration status, and school-related factors significantly impact adolescents’ psychological well-being (Afroz et al. 2023; Hermann et al. 2024; Kaman et al. 2020). For example, girls tend to have worse mental health outcomes than boys (Drosopoulou et al. 2023; Hadianfard et al. 2021), and this gender difference seems to be cross-cultural (Antia et al. 2023). On the other hand, factors such as not living with both parents, experiencing unfavorable living conditions (Sun and Yuan 2024), or frequently missing school and having academic difficulties are also associated with mental health problems, lower quality of life, and well-being (Mikkelsen et al. 2020; Zhou et al. 2025). Similarly, migrant adolescents or those living in less affluent families tend to fare worse than their native or more affluent peers (Amado-Rodríguez et al. 2025; Zaborskis et al. 2019). These disparities point to the importance of protective social conditions, such as family support, positive parenting practices, and access to educational and community resources, as key components in promoting adolescent mental health (Bauer et al. 2021; Benoit and Gabola 2021; Lanjekar et al. 2022; Viner et al. 2012).

Despite the importance of these individual and contextual factors, few studies have explored how they interact within integrative models of PMH. There is a particular lack of research examining moderated mediation processes in adolescence (i.e., how emotional regulation mediates the relationship between cognitive vulnerability and PMH and how this pathway may be buffered or intensified by peer support). Furthermore, sociodemographic differences in these pathways remain largely unexplored.

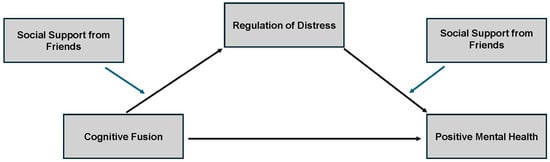

In light of these considerations, this study aimed to examine the relationship among various cognitive (i.e., cognitive fusion), emotional (i.e., regulation of distress), and social determinants (i.e., social support) in adolescents’ PMH. Accordingly, we present the proposed moderated mediation models (Figure 1), whose implications will be discussed in detail in the Results and Discussion sections.

Figure 1.

Moderated mediation models. The figure illustrates the proposed relationships among cognitive fusion, regulation of distress, and positive mental health (PMH). Regulation of distress is hypothesized to mediate the relationship between cognitive fusion and PMH, while social support from friends is expected to moderate both the link between cognitive fusion and regulation of distress and between regulation of distress and PMH.

Based on the existing literature, the following hypotheses were formulated:

H1.

Cognitive fusion will be negatively associated with PMH;

H2.

Regulation of distress will mediate the relationship between cognitive fusion and PMH;

H3.

Social support from friends will moderate the association between regulation of distress and PMH, with higher support weakening the negative impact of distress;

H4.

The strength of the moderated mediation model will vary depending on sociodemographic factors.

2. Materials and Methods

A cross-sectional study was performed among 505 adolescents in different school-based settings. This research received a positive evaluation from the Ethics Committee of the Principe de Asturias University Hospital with reference number OE 07/2023 and was authorized on 1 February 2023.

2.1. Participants

A total of 505 adolescents aged between 13 and 15 years (mean age, M = 13.62; standard deviation, SD = 0.70) filled out the survey (51.5% females) and were considered under study. All participants studied in a town northeast of Madrid (Spain). Practically all of them were Spanish nationals (88.1%). The most prevalent nationalities, different from the Spanish one, were from Venezuela (n = 14, 2.7%), Romania (n = 12, 2.4%), and Colombia (n = 8, 1.6%). In the case of the parents, 69.6% of one parent and 66.1% of the other parent were Spanish.

Regarding family situation, 69.7% (n = 352) were couples with children, while 22.8% (n = 115) were separated or divorced parents. The rest were single-parent families, same-parent families, or foster families, among others. Approximately a quarter of the students had repeated a grade (29.5%; n = 149). About half of the students (43.8%, n = 221) received some kind of educational support, the most frequent being private classes (26.7%, n = 135), diversification programs (7.5%, n = 38), or specific adaptations (2%, n = 10). See Table 1 for the sociodemographic and academic characteristics of the students participating in the study.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of participants.

Additionally, to be included in this study, participants had to meet the following criteria: (a) be officially enrolled in the third year of ESO (i.e., the Spanish acronym for compulsory secondary education) at the time of data collection and (b) possess adequate reading comprehension skills and the ability to complete the online questionnaire using digital devices. Exclusion criteria included (a) being on medical leave or temporarily expelled from school during the data collection period and (b) having a diagnosed disability that could compromise comprehension of the questionnaire items.

2.2. Instruments

An ad hoc online questionnaire was developed for this study. The first part of the questionnaire included self-reported data on sociodemographic variables such as age, gender, nationality, parental marital status, type of family, presence of educational support, and presence of student retention.

The second part of the questionnaire assessed psychological variables such as the following:

- The Positive Mental Health Questionnaire (PMHQ), which is a self-administered questionnaire with 39 items, was originally developed in Spanish by Lluch-Canut (1999), and it has also been validated for the Portuguese population by Sequeira et al. (2014). The form (PMHQ) contains 36 items loaded into six factors of the Multi-Model of Positive Mental Health—personal satisfaction (F1), prosocial attitude (F2), self-control (F3), autonomy (F4), problem solving and self-realization (F5), and interpersonal relationship skills (F6)—obtaining a very good global internal consistency of 0.92, with factors ranging from 0.60 to 0.82. This questionnaire has shown adequate psychometric properties in adolescent populations (from 11 to 20 years) in previous studies (Carbacas-Soleno et al. 2016);

- The Cognitive Fusion Questionnaire is a brief self-report measure of cognitive fusion with 7 items, originally developed by Gillanders et al. (2014). The questionnaire has been translated and validated in different languages, including Spanish, by Romero-Moreno et al. (2014). The range of internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) in the original scale was from 0.80 to 0.90, and the Spanish version had an internal consistency of 0.87. The Catalan version of this questionnaire has been validated in adolescents aged from 11 to 20 years, with evidence supporting its reliability and validity (Solé et al. 2015);

- The perception of distress, social, and family support was measured using single-item ad hoc questions rated on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (“never”) to 5 (“very frequently”): “To what extent do you feel capable of controlling your distress?”, “In the last month, have you felt supported by your friends when you needed it?”, and “In the last month, have you felt supported by your family when you needed it?”. These items were formulated based on relevant theoretical considerations. Previous research has shown that single-item measures can yield acceptable levels of reliability and validity, particularly when assessing unidimensional constructs and in contexts requiring brief assessments, such as large-scale or time-constrained studies (Eddy et al. 2019; Elo et al. 2003).

2.3. Procedure

Prior to data collection, the research objectives and procedures were presented to the school management, and formal permissions were obtained. Parental consent forms and detailed information sheets describing this study were distributed to the legal guardians of all potential participants. Only adolescents whose parents provided written informed consent and who themselves gave assent participated in this study. Both consent and assent could be withdrawn at any time.

The online questionnaire was administered during class time (integrated into the school’s daily routine) in sessions supervised by designated school staff in collaboration with members of the research team. The Google Forms questionnaire was configured so that each question required a response before participants could proceed. As a result, all submitted responses were fully completed, and no imputation or deletion methods were necessary to address missing values.

The estimated time required to complete the self-administered questionnaire was approximately 45 min. Researchers remained available to answer questions and provide clarification during the sessions. All responses were collected anonymously, and strict measures were taken to guarantee participants’ confidentiality.

Additionally, a formal pre-test was carried out with a small group of adolescents to ensure clarity and comprehensibility of the questionnaire items before the full data collection.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics version 27.0 (IBM Corp 2020). Descriptive statistics were computed for all variables, including frequencies and summary measures such as mean, standard deviation, minimum, and maximum values, to provide an initial overview of the data distribution and central tendencies. Specifically, the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to assess the normality of the variables. The data did not follow a normal distribution for either cognitive fusion (K-S = 0.049, p < 0.001) or PMH (K-S = 0.053, p < 0.001). Non-normal distributions are common in psychological research, as psychological variables and psychometric measures often deviate from normality due to their inherent characteristics (Bono et al. 2017). Despite the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test indicating non-normality, parametric tests were retained due to the large sample size (n = 505). According to the Central Limit Theorem, when sample sizes exceed approximately 30, the sampling distribution of the mean tends to approximate normality, even if the underlying data are not normally distributed. This makes parametric tests robust to violations of normality in large samples. Furthermore, as already mentioned, psychological variables frequently deviate from normality, and parametric methods are generally considered appropriate in such contexts (Field 2013; Tabachnick and Fidell 2019).

The covariate analysis aimed to examine the possible relationship of the variables involved in the model (cognitive fusion, regulation of distress, PMH, and social support from friends) with the sociodemographic variables considered. Sociodemographic variables that have been identified as variables of interest in relation to mental health in previous literature (i.e., age, gender, educational support, etc.) have been selected as possible covariates (Afroz et al. 2023; Antia et al. 2023; Amado-Rodríguez et al. 2025; Bauer et al. 2021; Benoit and Gabola 2021; Drosopoulou et al. 2023; Hadianfard et al. 2021; Hermann et al. 2024; Kaman et al. 2020; Lanjekar et al. 2022; Mikkelsen et al. 2020; Sun and Yuan 2024; Viner et al. 2012; Zaborskis et al. 2019; Zhou et al. 2025). To this end, a series of inferential statistical tests were performed. Independent samples t-tests were used to compare means between two groups, while one-way ANOVA was applied to assess differences among three or more groups. Additionally, Pearson’s correlation coefficients were calculated to explore potential covariates and to assess the relationships among variables within the proposed model, serving as a preliminary step for the mediation analysis (Christopher Westland 2010).

To explore more complex relationships among variables, mediation and moderated mediation analyses were carried out using the PROCESS macro for SPSS (Hayes 2021). A simple mediation model (Model 4) was employed to examine whether the relationship between the independent variable (i.e., cognitive fusion) and the dependent variable (i.e., PMH) was mediated by regulation of distress. The approach of this simple mediation model arises from the need to explore the mediating mechanisms (i.e., emotional regulation) between the well-known relationship between cognitive fusion and mental health (Faustino et al. 2023; Krafft et al. 2019; Solé et al. 2015).

In addition, two moderated mediation models (Model 7 and Model 14) were conducted to include support from friends as a moderating variable within the simple mediation model. Specifically, Model 7 was tested to examine whether social support from friends moderated the relationship between cognitive fusion and regulation of distress (path a), while Model 14 was used to test a moderated mediation model in which social support from friends moderated the relationship between regulation of distress and PMH (path b). The conceptualization of social support as a moderator is based on its role as a psychosocial resource in mental health (Bauer et al. 2021; Benoit and Gabola 2021; Lanjekar et al. 2022; Viner et al. 2012).

The significance of indirect effects in both models was assessed using bootstrapping, a non-parametric resampling technique that involves generating a large number of resamples (typically between 5000 and 10,000) to estimate the sampling distribution of the indirect effect. This method allows for the construction of confidence intervals, offering a robust evaluation of the indirect effects. Indirect effects were considered statistically significant if the 95% confidence intervals did not include zero. A significant threshold of p < 0.05 was applied to all statistical tests.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

Table 2 shows the descriptive statistics and correlations between the psychosocial variables studied. As can be seen in Table 2, there are significant negative correlations between cognitive fusion and regulation of distress (p < 0.001), PMH (p < 0.001), and social support from friends (p = 0.002). Regulation of distress maintains significant and positive correlations with PMH (p < 0.001), and social support from friends (p = 0.034). Finally, significant and positive correlations are also observed between PMH and social support from friends (p < 0.001).

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics and correlations between variables of interest.

3.2. Preliminary Analyses: Covariates

Age maintains significant relationships with social support from friends (F = 7.67; p = 0.001). Specifically, differences are observed between the 13-year-old group (M = 2.72; SD = 1.07) and the 15-year-old group (M = 2.11; SD = 1.33) (p = 0.001) and between the 14-year-old group (M = 2.66; SD = 1.14) and the 15-year-old group (p = 0.004).

With respect to gender, statistically significant differences are observed in cognitive fusion (women: M = 30.61, SD = 10.35; men: M = 24.07, SD = 10.12; t = −7.172; p < 0.001), in regulation of distress (women: M = 1.79, SD = 0.96; men: M = 2.42, SD = 1.04; t = 7.128; p < 0.001), and in PMH health (women: M = 114.64, SD = 15.27; men: M = 122.24, SD = 13.72; t = 5.871; p < 0.001).

Nationality (Spanish vs. non-Spanish) appears to be statistically significantly associated with PMH (Spanish: M = 119.17, SD = 14.88; non-Spanish: M = 111.62, SD = 15.43; t = 3.639; p < 0.001) and social support from friends (Spanish: M = 2.70, SD = 1.12; non-Spanish: M = 2.10, SD = 1.22; t = 3.770; p < 0.001). Similarly, significant trends are observed with respect to cognitive fusion (Spanish: M = 27.08, SD = 10.86; non-Spanish: M = 29.80, SD = 10.27; t = −1.896; p = 0.062).

School retention indicates a relationship with cognitive fusion (t = 2.619; p = 0.009), PMH (t = −2.311; p = 0.021), and social support from friends (t = −2.038; p = 0.042). Thus, students who have repeated grades present higher scores on cognitive fusion (M = 29.36, SD = 10.61) and lower scores on PMH (M = 115.95, SD = 14.88) and on social support from friends (M = 2.46, SD = 1.27) than those who have not repeated grades (M = 26.63, SD = 10.71; M = 119.32, SD = 14.98; M = 2.69, SD = 1.09, respectively).

Receiving additional educational support seems to be significantly related to cognitive fusion (M = 29.64, SD = 10.71; No M = 25.73, SD = 10.36; t = −4.025; p < 0.001) and PMH (M = 115.97, SD = 15.08; No M = 120.43, SD = 14.17; t = 3.311; p = 0.001). Table 3 shows the significant relationships found.

Table 3.

Analysis of covariates of interest.

3.3. Inferential Analyses: Theoretical Models

3.3.1. Simple Mediation Model (Cognitive Fusion, Regulation of Distress, and PMH)

Table 4 shows the results of the simple mediation analysis. According to the analysis of the possible covariates carried out in the previous section (see Table 3), gender, nationality, school retention, and educational support should be included as covariates.

Table 4.

Simple mediation model: Effects of cognitive fusion on positive mental health through regulation of distress (Model 4).

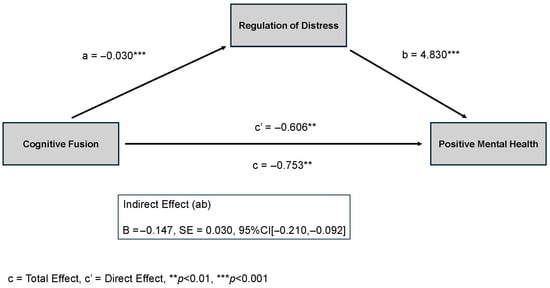

In particular, the model posits regulation of distress as a mediating variable between cognitive fusion and PMH. The results showed that cognitive fusion seems to be associated (in the proposed model) with PMH (total effect of X on Y: effect = −0.753, SE = 0.05, t = −13.78, p < 0.001, 95% CI = −0.861, −0.646). There is also a significant direct effect between cognitive fusion and PMH (effect = −0.607, SE = 0.05, t = −11.43, p < 0.001, 95% CI = −0.711, −0.502). The indirect effect of cognitive fusion on PMH through regulation of distress was statistically significant (effect = −0.147, SE = 0.03, 95% CI = −0.208, −0.091). Partially and completely standardized indirect effects were statistically significant (effect = −0.01, SE = 0.002, 95% CI = −0.014, −0.006; effect = −0.11, SE = 0.02, 95% CI = −0.148, −0.069).

The proposed model contributes to the explanation of 45% of the variance of PMH (F = 55.71, p < 0.001). Specifically, cognitive fusion is negatively related to regulation of distress (a = −0.030, SE = 0.004, t = −6.963, p < 0.001, 95% CI = −0.039, −0.021). On the other hand, regulation of distress influences PMH (b = 4.83, SE = 0.535, t = 9.029, p < 0.001, 95% CI = 3.779, 5.881). Regarding the role of covariates, significant effects of gender on regulation of distress (effect = −0.466, SE = 0.092, t = −5.048, p < 0.001, 95% CI = −0.648, −0.285) and of nationality on PMH (effect = −4.965, SE = 1.638, t = −3.030, p = 0.002, 95% CI = −8.186, −1.745) are observed. Figure 2 shows the coefficients of the relationships between the variables involved in the model.

Figure 2.

Coefficients of the proposed simple mediation model. The figure shows the significant indirect effect of cognitive fusion on positive mental health (PMH) through regulation of distress. Path a represents the negative association between cognitive fusion and regulation of distress, and path b represents the positive association between regulation of distress and PMH. The direct effect of cognitive fusion on PMH remains significant after accounting for the mediator.

3.3.2. Moderated Mediation Model (Social Support from Friends as a Moderating Variable)

The results show that only model 14 is statistically significant. Table 5 shows the results of the moderated mediation analysis. As can be seen in Table 5, cognitive fusion is negatively associated with regulation of distress (a = −0.030, SE = 0.004, t = −6.963, p < 0.001, 95% CI = −0.039, −0.021). In turn, regulation of distress suggests having positive effects on PMH (b = 7.501, SE = 1.197, t = 6.261, p < 0.001, 95% CI = 5.147, 9.855). Direct effects of cognitive fusion on PMH are also observed (c’ = −0.576, SE = 0.051, t = −11.145, p < 0.001, 95% CI = −0.678, −0.475). Regarding the moderating variable, social support from friends appears to have a direct positive effect on PMH (effect = 4.610, SE = 0.985, t = 4.680, p < 0.001, 95% CI = 2.674, 6.545). Similarly, a significant interaction effect of social support from friends on the relationship between regulation of distress and PMH is observed (effect = −1.097, SE = 0.413, t = −2.651, p = 0.008, 95% CI = −1.910, −0.283).

Table 5.

Moderated mediation model: cognitive fusion, regulation of distress, and positive mental health using support from friends (Model 14).

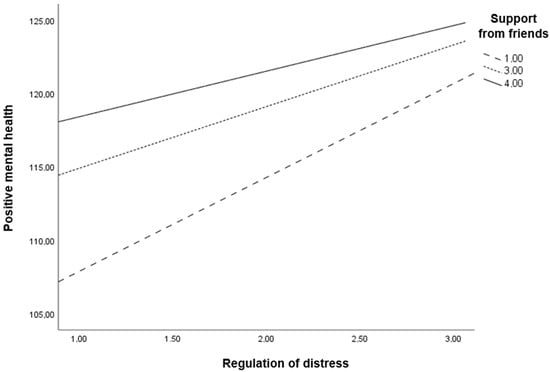

Table 6 shows the conditional effects of regulation of distress in PMH as a function of social support from friends. As can be seen, as scores on social support from friends become higher, the effects of regulation of distress on PMH seem to be minor (in all cases statistically significant). Figure 3 also shows these results.

Table 6.

Conditional effects of support from friends on the relationship between regulation of distress and positive mental health.

Figure 3.

Conditional effects of support from friends on the relationship between regulation of distress and positive mental health. The figure shows that the positive association between regulation of distress and positive mental health (PMH) is moderated by peer support. Specifically, the association is stronger when social support from friends is low and weaker when support from friends is high, suggesting that regulation of distress becomes especially relevant for maintaining PMH in contexts where social support is limited.

In terms of covariates, significant effects are observed for gender in regulation of distress (effect = −0.466, SE = 0.092, t = −5.048, p < 0.001, 95% CI = −0.648, −0.285) and nationality in PMH (effect = −3.890, SE = 1.601, t = −2.429, p = 0.015, 95% CI = −7.037, −0.743) (see Table 5). The proposed model contributes to the explanation of 49% of the variance of PMH (F = 49.89, p < 0.001).

3.3.3. Summary of Main Statistical Models

To provide a clearer and more integrated overview of the main findings, Table 7 summarizes the key statistical models tested in this study. The table includes the predictors, mediators, moderators, outcome variables, standardized beta coefficients, and significance levels for each model.

Table 7.

Summary of main statistical models tested.

4. Discussion

The present study aimed to explore how cognitive fusion, regulation of distress, social support from friends, and other social determinant factors interact in shaping PMH in adolescents. To the best of our knowledge, this is one of the few studies that have approached adolescent mental health from a salutogenic perspective. The concept of exploring and measuring PMH using an integrative model based on strengths has been rarely studied in the general population, especially among adolescents (Aguirre Velasco et al. 2020). Most studies have focused on risk factors and psychoeducation-based interventions, which cover general knowledge about mental health, suicide and self-harm, stigma, and depression. Promotion interventions have predominantly concentrated on enhancing mental health literacy and facilitating help-seeking behaviors (Gulliver et al. 2012; Xu et al. 2018). In contrast, other approaches emphasized promoting healthy lifestyle habits, such as physical activity, given its beneficial effects on psychological well-being (Andermo et al. 2020). Additionally, evidence indicates that school-based interventions involving parents and teachers and focusing on providing social support networks, such as peer mentoring, have certain positive effects (Troy et al. 2022). This is particularly relevant considering the ongoing neurodevelopmental changes during adolescence, which influence cognitive and emotional processes (Donati et al. 2021; Magar et al. 2010; Young et al. 2019).

Our results evidence that cognitive fusion negatively correlates with various important factors related to adolescent well-being, such as regulation of distress, PMH, and social support from friends. Specifically, cognitive fusion hinders regulation of distress by making children and adolescents more vulnerable to emotional dysregulation (Szemenyei et al. 2020). Additionally, cognitive fusion is a robust predictor of a range of psychological issues, including distress, depression, generalized anxiety, social anxiety, hostility, academic distress, and student role problems (Krafft et al. 2019).

Research on adolescents has identified positive reformulation, taking perspective, planning, and positive refocusing as the most used cognitive emotion regulation strategies, all of which are linked to indicators of PMH. In contrast, strategies such as rumination, catastrophizing, self-blame, and, to a lesser extent, acceptance are associated with negative affect and reflect cognitive patterns closely related to cognitive fusion, that is, entanglement with negative thoughts and difficulty in achieving psychological distancing (Cheng et al. 2022; Petrović et al. 2020). In this context, interventions specifically targeting cognitive fusion have shown effectiveness, particularly in reducing social anxiety and enhancing general well-being and social functioning (Bodenlos et al. 2020; Bramwell and Richardson 2018; Faustino et al. 2023; Krafft et al. 2019, 2020).

Adolescents are particularly sensitive to social influences as the brain regions involved in socio-emotional processing of information are still maturing (Donati et al. 2021; Magar et al. 2010; Young et al. 2019). Our findings indicate that social support from friends contributes to improved PMH and more effective regulation of distress. Research evidence shows that adolescents with strong peer support tend to experience lower psychological distress and improved mental health overall (Alsarrani et al. 2023; Ringdal et al. 2021). Specifically, receiving social support from friends helps them feel more connected and understood, regulates their emotions, reduces symptoms of depression and anxiety, improves self-esteem, and fosters resilience (Letkiewicz et al. 2023; Roach 2018; Surzykiewicz et al. 2022; Yin et al. 2017). Interestingly, the quality of peer relationships, rather than their quantity, plays a more critical role in predicting mental health outcomes, with high-quality peer support uniquely contributing to the reduction of depressive symptoms both in adolescence and adulthood (Letkiewicz et al. 2023). In other words, the subjective feeling of being supported (particularly among girls) appears to have a stronger association with PMH outcomes than objective measures, such as the size of an individual’s social network (Petersen et al. 2023). This highlights the importance of considering both the perception of support and the actual supportive behaviors when analyzing the moderating role of social support on regulation of distress and mental health.

In terms of protective factors, family type also predicts participants’ resilience and life satisfaction. The findings demonstrate a correlation between parental conflicts, feelings of loneliness and isolation within the family, the presence of supportive family members with whom one can share, and overall life satisfaction and mental well-being (Lin and Yi 2019; Proctor et al. 2009; Trong Dam et al. 2023). In fact, longitudinal studies have identified that perceived social support in adolescents was positively associated with all mental health indicators in early adulthood. Interestingly, and in line with previous research emphasizing the health relevance of social support, Millwood and Manczak (2023) explored how perceived emotional support during adolescence predicts inflammation in adulthood across different racial groups. Using longitudinal data from a large, racially diverse sample, the authors found that while greater adolescent social support was linked to lower inflammation in White participants (consistent with prior evidence), this association differed markedly in other racial groups. For individuals identifying as Asian, Latinx, Black, or Multiracial, higher perceived support during adolescence was unexpectedly associated with higher levels of adult inflammation. Moreover, the patterns of association varied depending on the type of relationship assessed. These findings underscore the importance of examining psychosocial predictors of health within specific racial and cultural contexts, rather than assuming uniform effects across populations.

Regarding the relationship between the variables involved in the model and several sociodemographic covariates such as age, gender, nationality, school retention, or receiving educational support, our results reveal a few relevant associations. For example, the analysis shows that the perception of social support from friends decreases as individuals age during adolescence. The diversification of support sources may explain this phenomenon. Older adolescents are more likely to look for social support from romantic partners and other non-family relationships. As these relationships gain prominence, adolescents may perceive a decline in the support received from friends (Spitz et al. 2020).

From the perspective of gender, adolescent girls exhibit a more severe psycho-emotional profile, which is defined by a higher degree of cognitive fusion, greater difficulties in regulating distress, and lower scores in PMH. One possible explanation is that girls tend to present more pronounced negative self-schemas, self-focused negative thoughts, and a stronger need for approval and success (Alloy et al. 2016; Ahmed et al. 2024; Calvete and Cardeñoso 2005). These characteristics are closely linked to higher emotional regulation difficulties, which are more evident in early adolescence (Sanchis-Sanchis et al. 2020) and, especially, when executive functioning is less developed to regulate this sensitivity (Davis et al. 2024). Moreover, the higher levels of psychological distress typically reported by girls are reflected in lower scores on key PMH components, such as life satisfaction, happiness, and self-esteem among others (Antia et al. 2023; Drosopoulou et al. 2023; Hadianfard et al. 2021; Hartas 2021; Hartas 2023). Similarly, another study conducted with Canadian adolescents exploring the concept of PMH revealed that being female, attending a school in an urban area, and exhibiting a greater number of prosocial behaviors were significantly associated with higher PMH. On the other hand, being in a higher grade; experiencing bullying; engaging in bullying behavior; exhibiting more behavioral problems; and using tobacco, alcohol, or cannabis were all significantly associated with lower PMH (Capaldi et al. 2021).

When considering nationality, in comparison with non-Spanish students, our results demonstrate that Spanish students have superior PMH, higher social support from friends, and a lower cognitive fusion (although this difference was not statistically significant). These outcomes are corroborated by a study who examined how perceived social support from different sources (i.e., family, friends, classmates, and teachers) contributed to substance use (i.e., alcohol and tobacco) and well-being (i.e., life satisfaction and health-related quality of life) among adolescents (aged 11 to 16 years) in Portugal and Spain. The results indicated that positive adolescent well-being was more strongly associated with social support than with substance use. In Portugal, higher life satisfaction was positively correlated with support from family, teachers, and classmates, whereas in Spain, support from family and friends was the most significant factor. Regarding health-related quality of life, all sources of support were significant in both countries, with family support being the most influential one overall (Jiménez-Iglesias et al. 2017). In the same vein, a study carried out by Amado-Rodríguez et al. (2025), which closely aligns with our research context, not only evidenced that female participants had higher emotional symptoms and behavioral difficulties than males but also found that foreign students exhibited higher scores on conduct problems and significantly greater difficulties in peer relationships than Spanish students.

In the context of school retention or receiving educational support, we have observed a negative impact on cognitive fusion, PMH, and social support from friends. While some studies highlight positive academic and cognitive outcomes when repeating a year in school (Marsh et al. 2017), others point to negative effects (i.e., lower executive and working memory functioning, diminished social skills, and perceived social support from teachers) related to stress and socio-emotional development (Fernandes et al. 2018; Mothes et al. 2017). Teachers and peers may sometimes contribute to the stigmatization and discrimination of students who repeat a grade (Faissol and Bastos 2014). As a result, these students often experience social isolation (either self-imposed or externally driven) and tend to disengage from classroom activities and show little motivation to participate in learning tasks (Almeida and Sartori 2012). In the same way, while educational support is generally intended to help adolescents in their academic and personal development (i.e., increase intrinsic motivation, behavioral engagement, etc.), it can lead to negative outcomes in emotional, behavioral and academic functioning, especially in those cases with learning disorders or a history of adverse childhood experiences, as they may have difficulty coping with the developmental and academic demands of adolescence (Abad Mas et al. 2022; Kelly 2008).

With respect to the proposed theoretical models, our results support a mediating effect of regulation of distress in the relationship between cognitive fusion and PMH. Strategies for regulation of distress may help explain how cognitive fusion influences PMH. For instance, techniques such as cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression have been found to mediate the impact of parental responses on adolescent distress, particularly in the relationship between maternal responses and adolescents’ emotional outcomes. These strategies partly explain how adolescents internalize and process emotional feedback received from their mothers. In this sense, positive maternal responses to emotions such as anger and happiness were found to be significant negative predictors of distress, suggesting, therefore, a protective effect. On the contrary, negative responses, especially those directed at expressions of happiness, were associated with increased distress. Interestingly, no mediating effects were observed for paternal responses, emphasizing the potentially more influential role that maternal emotion socialization may play during adolescence (Bujor and Turliuc 2023). Other regulation strategies like positive reformulation can predict greater well-being, and this effect has been shown to be partly mediated by positive affectivity (Petrović et al. 2020). Similarly, experiential avoidance, another form of regulation of distress, moderates the relationship between cognitive fusion and depression, helping to alleviate depressive symptoms among college students (Hekmati et al. 2023). Notably, the model’s significance persisted after adjusting for covariates, explaining 45% of the variance observed in PMH.

When including social support from friends within the simple mediation model (i.e., moderated mediation model), our results show that this variable has a significant moderating effect in the relationship between regulation of distress and PMH, contributing to the explanation of 49% of the variance. As already mentioned, social support from friends is linked to enhanced psychological well-being (Alshammari et al. 2021; Bauer et al. 2021; Benoit and Gabola 2021; Lanjekar et al. 2022; Petrović et al. 2020; Viner et al. 2012), since it facilitates connectedness, emotional regulation, increased self-worth, and resilience, all of them key indicators of PMH (Letkiewicz et al. 2023; Roach 2018; Surzykiewicz et al. 2022; Yin et al. 2017). In the same way, it has been found that adolescents with a more extroverted personality and, therefore, with a greater capacity to obtain social support, are positively associated with PMH, while adolescents with higher levels of neuroticism present lower levels of PMH. The same study observed that perceived school stress mediated the relationship between neuroticism (a factor that may be linked to cognitive fusion) and PMH (Tian et al. 2019). More precisely, our outcomes also manifest that as scores on peer support become higher, the effects of regulation of distress on PMH are minor. In other words, the ability to regulate distress is essential for maintaining good mental health, especially when social support is low. While high social support from friends may reduce the immediate dependence on strong emotion regulation skills, these abilities still offer significant benefits, but the support itself provides a substantial buffer against emotional distress (Fitzpatrick et al. 2024; Wang et al. 2024). These findings underscore the importance of considering the various sources and levels of social support during a particular vulnerability period, such as adolescence (Fitzpatrick et al. 2024). Research shows that the dynamic interplay between different types of support has a meaningful impact on adolescents’ daily lives and well-being. For example, on days when adolescents perceive greater support, whether from friends or parents, they report increased levels of happiness and stronger social connectedness. Furthermore, parental support can serve as a compensatory factor in situations where peer support is lacking (Schacter and Margolin 2019). Likewise, the school environment constitutes another fundamental space of social support. Recent investigations emphasize the significance of fostering positive relationships between adolescents and teachers, as well as addressing emotional concerns within the classroom context. These dimensions of school-based support may contribute to promoting emotional well-being, underscoring the relevance of integrating health and life skills programs as part of school efforts to strengthen mental health support mechanisms (Røsand and Johansen 2024; Schütz et al. 2025).

Limitations and Future Directions

This study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, regarding measurement, the instruments used to assess social support and emotional regulation were developed ad hoc for this study and based on theoretical considerations but not on previously validated scales. Although this choice aimed to ensure feasibility and brevity, it may affect the reliability and construct validity of the measures. Future research would benefit from using standardized, validated tools to assess these constructs.

Second, this study relied exclusively on self-report measures, which may introduce biases such as social desirability or recall bias, and limit the objectivity of the data collected. The inclusion of additional information sources (e.g., reports from parents, teachers, or observational methods) would enhance the robustness of the findings.

Third, the characteristics of the sample limit the generalizability of the findings. Although data were collected from a large group of adolescents, participants were exclusively aged 13–14 years and drawn from several schools in an urban region. Therefore, the results cannot be generalized to adolescents from other age groups or different geographic and sociocultural contexts. Future studies should include diverse cohorts to verify the consistency of these findings.

On the other hand, cross-sectional design limits the ability to examine how relationships and psychological processes evolve over time. Given that adolescence is a dynamic developmental period, future research should adopt longitudinal designs to explore the changing role of social relationships, emotional regulation, and cognitive processes throughout late adolescence and early adulthood. Additionally, intervention studies are needed to evaluate the effectiveness of programs aimed at reducing cognitive fusion, enhancing regulation of distress, and promoting high-quality peer relationships.

Finally, future research should give attention to adolescents’ own perspectives on mental health promotion, particularly in the school context. Qualitative evidence (Oliveira-Costa et al. 2022) shows that adolescents consider mental health training programs relevant and necessary. Incorporating adolescents’ voices into the design and evaluation of mental health literacy initiatives may increase the relevance, acceptability, and impact of such interventions. Future studies should further explore these participatory approaches as a means to empower adolescents and enhance the effectiveness of school-based mental health programs.

5. Conclusions

This study explores important determinant factors of adolescents’ mental and emotional health, highlighting mediating and moderating variables that exert a significant influence and may serve as targets for intervention from both promotion and prevention perspectives. The results evidence the negative impact of cognitive fusion on PMH, as well as the mediating role of regulation of distress in this relationship. Furthermore, social support from friends significantly moderates the link between regulation of distress and PMH, acting as a protective factor that can mitigate emotional difficulties.

The analysis also identifies specific risk profiles, including girls, non-national adolescents, students from dysfunctional family structures, and those receiving educational support, all of whom exhibit lower levels of PMH. These findings underscore the need to take into consideration gender, sociocultural context, and academic vulnerability in the design of mental health interventions.

Additionally, the combined effects of cognitive, emotional, and social factors point to the importance of adopting multifaceted approaches to promoting mental health in adolescence. Specifically, the development of emotional self-regulation skills and the strengthening of peer support networks should be central components of school-based programs. Moreover, the involvement of parents and teachers is essential, as evidence has shown that high-quality relationships with these figures are also beneficial for adolescents’ well-being. Therefore, efforts should also be made toward providing parents and educators with the appropriate skills to effectively support students.

Overall, these findings support a salutogenic approach to adolescent mental health, emphasizing protective psychological resources and social contexts rather than solely focusing on risk and pathology. Special attention should be paid to particularly vulnerable subgroups, such as girls, immigrant youth, and students with special educational needs, to ensure more equitable and effective mental health outcomes.

6. Practical Implications for Adolescents’ Mental Health

Considering the findings of our study together with the revised literature, several practical implications can be identified to guide the promotion of adolescents’ mental health. Addressing this issue adequately requires an integrated approach that takes into account the interplay between cognitive, emotional, social, and contextual factors. The following key areas highlight priority actions for fostering adolescent well-being:

- Development of emotional self-regulation skills. Enhancing adolescents’ capacity for emotional regulation and distress management is essential for promoting PMH;

- Strengthening social support networks. Social support, particularly from peers, parents, and teachers, acts as a significant protective factor. Efforts should aim to enhance both the availability of supportive relationships and adolescents’ subjective perception of being supported;

- Increasing the role of schools as protective contexts. Schools represent a strategic setting for mental health promotion. Reinforcing teacher–student relationships, promoting positive classroom environments, and implementing life skills and well-being programs can have a positive impact;

- Active collaboration/involvement of parents and educators. Providing parents and teachers with the necessary tools and training enhances their ability to offer effective support and guidance, consolidating a comprehensive support network around adolescents;

- Addressing individual and contextual vulnerabilities. Intervention strategies should be sensitive to gender, sociocultural background, family structure, and academic risk factors. Special attention to vulnerable groups is crucial to promoting equitable mental health outcomes;

- Promoting adolescent participation and mental health literacy. Adolescents themselves should play an active role in shaping mental health initiatives. Supporting mental health literacy and incorporating their perspectives into program design could increase their relevance, engagement, and effectiveness.

These implications reinforce the idea that promoting adolescents’ mental health extends beyond clinical interventions. It requires shared commitment from all professionals working with adolescents, framed within a broader public health strategy. By adopting coordinated, holistic, and context-sensitive approaches, mental health initiatives can better respond to the needs of diverse adolescent populations and contribute to fostering resilience, well-being, and social equity.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.G.-S. and P.G.-A.; methodology, C.P.-P.; software, C.P.-P.; validation, I.C.R.-R., R.L.-G. and M.G.-S.; formal analysis, C.P.-P.; investigation, D.C.-L. and P.B.-G.; resources, Á.A.-E.; data curation, I.C.R.-R.; writing—original draft preparation, I.C.R.-R.; writing—review and editing, R.L.-G., I.C.R.-R.; visualization, M.G.-S.; supervision, R.L.-G.; project administration, C.P.-P. and I.C.R.-R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive external funding for its development.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This research received a positive evaluation from the Ethics Committee of the Principe de Asturias University Hospital with reference number OE 07/2023.

Informed Consent Statement

Formal permission was initially obtained from the heads of the participating schools. Informed consent was then obtained from the parents or legal guardians of the participants. Finally, an informed assent was obtained from the adolescents who ultimately participated, as required by law regarding research involving minors.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the results presented can be requested from the corresponding author if necessary.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PMH | Positive Mental Health |

| PMHQ | Positive Mental Health Questionnaire |

References

- Abad Mas, Luis, Moreno Madrid Paqui, Peláez Marco Violeta, Huerta Pándura Denisse, Valls Monzó Alicia, Martínez Borondo Reyes, Ibáñez Orrico Amparo, and Paula Mengod Balbas. 2022. Problemas Escolares en la Adolescencia. Pediatría Integral 26: 222–28. Available online: http://www.pediatriaintegral.es/wp-content/uploads/2022/xxvi04/03/n4-222-228_LuisAbadMas.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Afroz, Nahida, Enamul Kabir, and Khorshed Alam. 2023. A Latent Class Analysis of the Socio-Demographic Factors and Associations with Mental and Behavioral Disorders among Australian Children and Adolescents. PLoS ONE 18: e0285940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguirre Velasco, Antonia, Ignacio Silva Santa Cruz, Jo Billings, Magdalena Jimenez, and Sarah Rowe. 2020. What Are the Barriers, Facilitators and Interventions Targeting Help-Seeking Behaviours for Common Mental Health Problems in Adolescents? A Systematic Review. BMC Psychiatry 20: 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, Saz P., Blanca Piera Pi-Sunyer, Madeleine E. Moses-Payne, Anne-Lise Goddings, Lydia G. Speyer, Willem Kuyken, Tim Dalgleish, and Sarah-Jayne Blakemore. 2024. The Role of Self-Referential and Social Processing in the Relationship between Pubertal Status and Difficulties in Mental Health and Emotion Regulation in Adolescent Girls in the UK. Developmental Science 27: e13503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alloy, Lauren B., Jessica L. Hamilton, Elissa J. Hamlat, and Lyn Y. Abramson. 2016. Pubertal Development, Emotion Regulatory Styles, and the Emergence of Sex Differences in Internalizing Disorders and Symptoms in Adolescence. Clinical Psychological Science 4: 867–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, Teresinha De Fátima Souto, and J. Sartori. 2012. A Relação Entre Desmotivação e o Processo de Ensino-Aprendizagem. Revista Monografias Ambientais 8: 1870–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsarrani, Abdullah, Ruth Hunter, Laura Dunne, and Leandro Garcia. 2023. Association between Friendship Quality and Subjective Wellbeing in Adolescents: A Cross-Sectional Observational Study. The Lancet 402 S1: S21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshammari, Abdullah S., Bettina F. Piko, and Kevin M. Fitzpatrick. 2021. Social Support and Adolescent Mental Health and Well-Being among Jordanian Students. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth 26: 211–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amado-Rodríguez, Isaac Daniel, Rocio Casañas, Jaume Juan-Parra, Juan Francisco Roldan-Merino, Lluís Lalucat-Jo, and Ma Isabel Fernandez-San-Martín. 2025. Impact of Mental Health Literacy on Improving Quality of Life among Adolescents in Barcelona. Children 12: 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andermo, Susanne, Mats Hallgren, Thi-Thuy-Dung Nguyen, Sofie Jonsson, Solveig Petersen, Marita Friberg, Anja Romqvist, Brendon Stubbs, and Liselotte Schäfer Elinder. 2020. School-Related Physical Activity Interventions and Mental Health among Children: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Medicine—Open 6: 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antia, Khatia, Justina Račaitė, Genė Šurkienė, and Volker Winkler. 2023. The Gender Gap in Adolescents’ Emotional and Behavioural Problems in Georgia: A Cross-Sectional Study Using Achenbach’s Youth Self Report. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health 17: 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauer, Annette, Madeleine Stevens, Daniel Purtscheller, Martin Knapp, Peter Fonagy, Sara Evans-Lacko, and Jean Paul. 2021. Mobilising Social Support to Improve Mental Health for Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review Using Principles of Realist Synthesis. PLoS ONE 16: e0251750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauer, Georg Friedrich, M. Roy, P. Bakibinga, P. Contu, S. Downe, Monica Eriksson, G. A. Espnes, B. B. Jensen, D. Juvinya Canal, Bengt Lindström, and et al. 2020. Future Directions for the Concept of Salutogenesis: A Position Article. Health Promotion International 35: 187–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benoit, Valérie, and Piera Gabola. 2021. Effects of Positive Psychology Interventions on the Well-Being of Young Children: A Systematic Literature Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18: 12065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bodenlos, Jamie S., Elizabeth S. Hawes, Sarah M. Burstein, and Kelsey M. Arroyo. 2020. Association of Cognitive Fusion with Domains of Health. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science 18: 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bono, Roser, M. J. Blanca, J. Arnau, and J. Gómez-Benito. 2017. Non-Normal Distributions Commonly Used in Health, Education, and Social Sciences: A Systematic Review. Frontiers in Psychology 8: 1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bramwell, Kate, and Thomas Richardson. 2018. Improvements in Depression and Mental Health after Acceptance and Commitment Therapy Are Related to Changes in Defusion and Values-Based Action. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy 48: 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branje, Susan. 2022. Adolescent Identity Development in Context. Current Opinion in Psychology 45: 101286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinke, Lysanne W., Ankie T. A. Menting, Hilde D. Schuiringa, Janice Zeman, and Maja Deković. 2020. The Structure of Emotion Regulation Strategies in Adolescence: Differential Links to Internalizing and Externalizing Problems. Social Development 30: 536–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bujor, Liliana, and Maria Nicoleta Turliuc. 2023. Do Emotion Regulation Strategies Mediate the Relationship of Parental Emotion Socialization with Adolescent and Emerging Adult Psychological Distress? Healthcare 11: 2620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calvete, Esther, and Olga Cardeñoso. 2005. Gender Differences in Cognitive Vulnerability to Depression and Behavior Problems in Adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology 33: 179–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capaldi, Colin A., Mélanie Varin, and Raelyne L. Dopko. 2021. Determinants of Psychological and Social Well-Being among Youth in Canada: Investigating Associations with Sociodemographic Factors, Psychosocial Context and Substance Use. Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention in Canada: Research, Policy and Practice 41: 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbacas-Soleno, Jhair, Lisey M. Mendoza-Bolaño, and David J. Fortich-Pérez. 2016. Validación del Cuestionario de Salud Mental Positiva de Lluch en Jóvenes Estudiantes en el Municipio de Carmen de Bolívar. Universidad Tecnológica de Bolívar. Available online: https://repositorio.utb.edu.co/entities/publication/1a73a1d0-ecd2-4561-8427-114778bbad2d (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Cheng, Qi, Congrong Shi, Chao Yan, Zhihong Ren, Sunny Ho-Wan Chan, Sijia Xiong, Tao Zhang, and Hong Zheng. 2022. Sequential Multiple Mediation of Cognitive Fusion and Experiential Avoidance in the Relationship between Rumination and Social Anxiety among Chinese Adolescents. Anxiety, Stress, and Coping 35: 354–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christopher Westland, James. 2010. Lower Bounds on Sample Size in Structural Equation Modeling. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications 9: 476–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, Megan M., Haina H. Modi, Haley V. Skymba, Katherine Haigler, Megan K. Finnegan, Eva H. Telzer, and Karen D. Rudolph. 2024. Neural Sensitivity to Peer Feedback and Depressive Symptoms: Moderation by Executive Function. Developmental Psychobiology 66: e22515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donati, Georgina, Emma Meaburn, and Iroise Dumontheil. 2021. Internalising and Externalising in Early Adolescence Predict Later Executive Function, Not the Other Way around: A Cross-Lagged Panel Analysis. Cognition & Emotion 35: 986–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drosopoulou, Georgia, Foteini Vlasopoulou, Eleni Panagouli, Androniki Stavridou, Alexia Papageorgiou, Theodora Psaltopoulou, Maria Tsolia, Chara Tzavara, Theodoros N. Sergentanis, and Artemis K. Tsitsika. 2023. Cross-National Comparisons of Internalizing Problems in a Cohort of 8952 Adolescents from Five European Countries: The EU NET ADB Survey”. Children 10: 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eddy, Colleen L., Keith C. Herman, and Wendy M. Reinke. 2019. Single-Item Teacher Stress and Coping Measures: Concurrent and Predictive Validity and Sensitivity to Change. Journal of School Psychology 76: 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elo, Anna-Liisa, Anneli Leppänen, and Antti Jahkola. 2003. Validity of a Single-Item Measure of Stress Symptoms. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health 29: 444–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engell, Thomas, Siri Saugestad Helland, Emily Gabriela Vira, Silje Berg, Line Solheim Kvamme, John Kjøbli, Josefine Bergseth, Inga Brenne, Ragnhild Bang Nes, Espen Røysamb, and et al. 2025. The Implementability and Proximal Effects of a Transdiagnostic Mental Health Intervention for Adolescents (Kort): Protocol for a Mixed-Methods Intensive Longitudinal Study. BMC Health Services Research 25: 639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faissol, Katia Regina Monte, and Maria Cristina Bastos. 2014. «Projecto Refazer: Uma reflexão Da reprovação a Partir Do Olhar Do Aluno». Revista De Psicologia Da Criança E Do Adolescente 5: 201–10. Available online: https://d1wqtxts1xzle7.cloudfront.net/113895175/rpca_v5_n1_12-libre.pdf?1714324523=&response-content-disposition=inline%3B+filename%3DProjecto_refazer_uma_reflexao_da_reprova.pdf&Expires=1753438178&Signature=SPIXoU3VNLLuttsp-ZxNpHE1UTpQYxxV-A9bOr3X3tEsU85xgi7SjLphKYaVWvD7SlWg4aoH6Y14V8stgnkZiihp1L67Do5Wnc6yjFekjHhQ3Vg11JlPEMqyRwF3TlfD0aC9sCOaqvTwD~Tchh2KqAQVHtCLN5zfBFp39qBPEJ~-cvWHFG1tTZEsgMpWdrMqOq1-MOyWJoQZyhkqJVLvpZRwVdTwxR~8qi~cO8jQTnAb-GhGP~yskL8yjDsnTDmHiGfHpiBSt4ya4jrUNC~ssIuaSg6VDA4-WlZcDsmSh-izYpuXLRbl70cOGMZ72O3ujUmkPGStK3Ylnu8RYJosQg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAJLOHF5GGSLRBV4ZA (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Faustino, Bruno, António Branco Vasco, António Farinha-Fernandes, and João Delgado. 2023. Psychological Inflexibility as a Transdiagnostic Construct: Relationships between Cognitive Fusion, Psychological Well-Being and Symptomatology. Current Psychology 42: 6056–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, Luana M., Vanessa Barbosa R. Leme, Luciana Carla S. Elias, and Adriana B. Soares. 2018. Predictors of academic achievement at the end of middle school: History of repetition, social skills and social support. Temas em Psicologia 26: 229–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, Andy. 2013. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics, 4th ed. London: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick, Margaret M., Avery M. Anderson, Christopher Browning, and Jodi L. Ford. 2024. Relationship between Family and Friend Support and Psychological Distress in Adolescents. Journal of Pediatric Health Care: Official Publication of National Association of Pediatric Nurse Associates & Practitioners 38: 804–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Moya, Irene, and Antony Morgan. 2017. The Utility of Salutogenesis for Guiding Health Promotion: The Case for Young People’s Well-Being. Health Promotion International 32: 723–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Sastre, María Montserrat, Patricia González-Alegre, Raquel Luengo-González, Daniel Cuesta-Lozano, Inmaculada Concepción Rodríguez-Rojo, Teresa Lluch-Canut, and Cecilia Peñacoba-Puente. 2024. Promoting Mental Health in Adolescents: ‘Teens Menta, a Nursing Intervention Program Based in the Positive Mental Health Model. Psychology International 6: 710–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillanders, David T., Helen Bolderston, Frank W. Bond, Maria Dempster, Paul E. Flaxman, Lindsey Campbell, Sian Kerr, Louise Tansey, Penelope Noel, Clive Ferenbach, and et al. 2014. The Development and Initial Validation of the Cognitive Fusion Questionnaire. Behavior Therapy 45: 83–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffin, Angela. 2017. Adolescent Neurological Development and Implications for Health and Well-Being. Healthcare 5: 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulliver, Amelia, Kathleen M. Griffiths, Helen Christensen, and Jacqueline L. Brewer. 2012. A Systematic Review of Help-Seeking Interventions for Depression, Anxiety and General Psychological Distress. BMC Psychiatry 12: 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadianfard, Habib, Behnaz Kiani, Mahla Azizzadeh Herozi, Fatemeh Mohajelin, and John T. Mitchell. 2021. Health-Related Quality of Life in Iranian Adolescents: A Psychometric Evaluation of the Self-Report Form of the PedsQL 4.0 and an Investigation of Gender and Age Differences. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 19: 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartas, Dimitra. 2021. The Social Context of Adolescent Mental Health and Wellbeing: Parents, Friends and Social Media. Research Papers in Education 36: 542–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartas, Dimitra. 2023. Wellbeing, Psychological Distress and Self-Harm in Late Adolescence in the UK: The Role of Gender and Personality Traits. European Journal of Special Needs Education 39: 201–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, Andrew F. 2021. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. Nueva York: Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Hekmati, Issa, Hamed Abdollahpour Ranjbar, Mehmet Eskin, Chad E. Drake, and Laura Jobson. 2023. The Moderating Role of Experiential Avoidance on the Relationship between Cognitive Fusion and Psychological Distress among Iranian Students. Current Psychology 42: 1394–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermann, Veronica, Fredrik Söderqvist, Ann-Christin Karlsson, Anna Sarkadi, and Natalie Durbeej. 2024. Mental Health Status According to the Dual-Factor Model in Swedish Adolescents: A Cross Sectional Study Highlighting Associations with Stress, Resilience, Social Status and Gender. PLoS ONE 19: e0299225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewis, Johnathan. 2023. A Salutogenic Approach: Changing the Paradigm. Journal of Medical Imaging and Radiation Sciences 54 S2: S17–S21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBM Corp. 2020. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, (Version 27.0). Armonk: IBM Corp. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez-Iglesias, Antonia, Inês Camacho, Francisco Rivera, Carmen Moreno, and Margarida Gaspar de Matos. 2017. Social Support from Developmental Contexts and Adolescent Substance Use and Well-Being: A Comparative Study of Spain and Portugal. The Spanish Journal of Psychology 20: E64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaman, Anne, Veronika Ottová-Jordan, Ludwig Bilz, Gorden Sudeck, Irene Moor, and Ulrike Ravens-Sieberer. 2020. Subjective Health and Well-Being of Children and Adolescents in Germany—Cross-Sectional Results of the 2017/18 HBSC Study. Journal of Health Monitoring 5: 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, Desmond P. 2008. Learning Disorders in Adolescence: The Role of the Primary Care Physician. Adolescent Medicine: State of the Art Reviews 19: 229–41, viii. [Google Scholar]

- Krafft, Jennifer, Jack A. Haeger, and Michael E. Levin. 2019. Comparing Cognitive Fusion and Cognitive Reappraisal as Predictors of College Student Mental Health. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy 48: 241–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krafft, Jennifer, Michael P. Twohig, and Michael E. Levin. 2020. A Randomized Trial of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy and Traditional Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy Self-Help Books for Social Anxiety. Cognitive Therapy and Research 44: 954–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanjekar, Purva D., Shiv H. Joshi, Puja D. Lanjekar, and Vasant Wagh. 2022. The Effect of Parenting and the Parent-Child Relationship on a Child’s Cognitive Development: A Literature Review. Cureus 14: e30574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, Bart, and Beatriz Luna. 2018. Adolescence as a Neurobiological Critical Period for the Development of Higher-Order Cognition. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews 94: 179–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letkiewicz, Allison M., Lilian Y. Li, Lija M. K. Hoffman, and Stewart A. Shankman. 2023. A Prospective Study of the Relative Contribution of Adolescent Peer Support Quantity and Quality to Depressive Symptoms. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines 64: 1314–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Wen-Hsu, and Chin-Chun Yi. 2019. The Effect of Family Cohesion and Life Satisfaction during Adolescence on Later Adolescent Outcomes: A Prospective Study. Youth & Society 51: 680–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lluch-Canut, María Teresa. 1999. Construcción de una Escala para Evaluar la Salud Mental Positiva. Doctoral thesis, University of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain. Available online: https://www.tdx.cat/handle/10803/2366 (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Magar, Emily C. E., Louise H. Phillips, and Judith A. Hosie. 2010. Brief Report: Cognitive-Regulation across the Adolescent Years. Journal of Adolescence 33: 779–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, Herbert W., Reinhard Pekrun, Philip D. Parker, Kou Murayama, Jiesi Guo, Theresa Dicke, and Stephanie Lichtenfeld. 2017. Long-Term Positive Effects of Repeating a Year in School: Six-Year Longitudinal Study of Self-Beliefs, Anxiety, Social Relations, School Grades, and Test Scores. Journal of Educational Psychology 109: 425–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikkelsen, Hilde Timenes, Kristin Haraldstad, Sølvi Helseth, Siv Skarstein, Milada Cvancarova Småstuen, and Gudrun Rohde. 2020. Health-Related Quality of Life Is Strongly Associated with Self-Efficacy, Self-Esteem, Loneliness, and Stress in 14-15-Year-Old Adolescents: A Cross-Sectional Study. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 18: 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Millwood, Summer N., and Erika M. Manczak. 2023. Patterns of Adolescent Perceived Social Support and Inflammation in Adulthood within Major Racial Groups: Findings from a Longitudinal, Nationally Representative Sample. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity 110: 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittelmark, Maurice B., and Georg F. Bauer. 2022. Salutogenesis as a Theory, as an Orientation and as the Sense of Coherence. In The Handbook of Salutogenesis, 2nd ed. Edited by Maurice B. Mittelmark, Georg F. Bauer, Lenneke Vaandrager, Jürgen M. Pelikan, Shifra Sagy, Monica Eriksson, Bengt Lindström and Claudia Meier Magistretti. Cham: Springer. Available online: https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-030-79515-3 (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Morris, Amanda S., Michael M. Criss, Jennifer S. Silk, and Benjamin J. Houltberg. 2017. The Impact of Parenting on Emotion Regulation during Childhood and Adolescence. Child Development Perspectives 11: 233–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mothes, Luiza, Haag Kristensen Christian, Grassi Oliveira Rodrigo, Iracema de Lima Argimon, Fonseca Paz, and Tatiana Quarti Irigaray. 2017. Stressful Events and Executive Functioning in Adolescents with and without History of Grade Repetition. Universitas Psychologica 16: 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Health and Medicine Division, Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education, Board on Children, Youth, and Families, and Committee on the Neurobiological and Socio-Behavioral Science of Adolescent Development and Its Applications. 2019. The Promise of Adolescence: Realizing Opportunity for All Youth. Edited by Emily P. Backes and Richard J. Bonnie. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira-Costa, Tiago Filipe, Francisco Miguel Correia Sampaio, Carlos Alberto da Cruz Sequeira, María Teresa Lluch Canut, and Antonio Rafael Moreno Poyato. 2022. A Qualitative Study Exploring Adolescents’ Perspective about Mental Health First Aid Training Programmes Promoted by Nurses in Upper Secondary Schools. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing 31: 326–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petersen, Kimberly J., Pamela Qualter, Neil Humphrey, Mogens Trab Damsgaard, and Katrine Rich Madsen. 2023. With a Little Help from My Friends: Profiles of Perceived Social Support and Their Associations with Adolescent Mental Health. Journal of Child and Family Studies 32: 3430–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrović, Jelica, Jovana Trbojević, and Dukai Emeše. 2020. Kognitivna Regulacija Emocija i Subjektivno Blagostanje kod Adolescenata: Postoji li Direktna Veza? Primenjena Psihologija 13: 371–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeifer, Jennifer H., and Nicholas B. Allen. 2021. Puberty Initiates Cascading Relationships between Neurodevelopmental, Social, and Internalizing Processes across Adolescence. Biological Psychiatry 89: 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Proctor, Carmel L., P. Alex Linley, and John Maltby. 2009. Youth Life Satisfaction: A Review of the Literature. Journal of Happiness Studies 10: 583–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragelienė, Tija. 2016. Links of Adolescents Identity Development and Relationship with Peers: A Systematic Literature Review. Journal de l’Academie Canadienne de Psychiatrie de l’enfant et de l’adolescent [Journal of the Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry] 25: 97–105. [Google Scholar]

- Renwick, Laoise, Rebecca Pedley, Isobel Johnson, Vicky Bell, Karina Lovell, Penny Bee, and Helen Brooks. 2022. Conceptualisations of Positive Mental Health and Wellbeing among Children and Adolescents in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review and Narrative Synthesis. Health Expectations: An International Journal of Public Participation in Health Care and Health Policy 25: 61–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringdal, Regine, Hanne Nissen Bjørnsen, Geir Arild Espnes, Mary-Elizabeth Bradley Eilertsen, and Unni Karin Moksnes. 2021. Bullying, Social Support and Adolescents’ Mental Health: Results from a Follow-up Study. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health 49: 309–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roach, Ashley. 2018. Supportive Peer Relationships and Mental Health in Adolescence: An Integrative Review. Issues in Mental Health Nursing 39: 723–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Moreno, Rosa, M. Márquez-González, A. Losada, David Gillanders, and Virginia Fernández-Fernández. 2014. Cognitive Fusion Questionnaire—Spanish Version (CFQ) [Database record]. APA PsycTests: Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/t65411-000 (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Røsand, Ingvild, and Vegard Johansen. 2024. Connections between the School Environment and Emotional Problems among Boys and Girls in Upper Secondary School. Cogent Education 11: 2307688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchis-Sanchis, Alejandro, Ma Dolores Grau, Adoración-Reyes Moliner, and Catalina Patricia Morales-Murillo. 2020. Effects of Age and Gender in Emotion Regulation of Children and Adolescents. Frontiers in Psychology 11: 946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schacter, Hannah L., and Gayla Margolin. 2019. The Interplay of Friends and Parents in Adolescents’ Daily Lives: Towards A Dynamic View of Social Support. Social Development 28: 708–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schütz, Raphael, Franziska Reiss, Irene Moor, Anne Kaman, Ludwig Bilz, and HBSC Study Group Germany. 2025. Lonely Children and Adolescents Are Less Healthy and Report Less Social Support: A Study on the Effect of Loneliness on Mental Health and the Moderating Role of Social Support. BMC Public Health 25: 2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sequeira, Carlos, Carvalho José Carlos, Sampaio Francisco, Sá Luís, Teresa Lluch-Canut, and Juan Roldán-Merino. 2014. Avaliação das Propriedades Psicométricas do Questionário de Saúde Mental Positiva em Estudantes Portugueses do Ensino Superior. Revista Portuguesa de Enfermagem de Saúde Mental 11: 45–53. [Google Scholar]

- Solé, Ester, Racine Mélanie, Castalernas Elena, de la Vega Rocío, Tomé-Pires Catarina, Jensen Mark, and Miró Jordi. 2015. The Psychometric Properties of the Cognitive Fusion Questionnaire in Adolescents. European Journal of Psychological Assessment 32: 181–86. Available online: https://econtent.hogrefe.com/doi/10.1027/1015-5759/a000244 (accessed on 1 June 2025). [CrossRef]

- Spitz, Andrea, Christa Winkler Metzke, and Hans-Christoph Steinhausen. 2020. Development of Perceived Familial and Non-Familial Support in Adolescence; Findings from a Community-Based Longitudinal Study. Frontiers in Psychology 11: 486915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Xiaoyue, and Yiqing Yuan. 2024. Associations between Parental Socioeconomic Status and Mental Health in Chinese Children: The Mediating Roles of Parenting Practices. Child and Adolescent Mental Health 29: 292–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surzykiewicz, Janusz, Sebastian Binyamin Skalski, Agnieszka Sołbut, Sebastian Rutkowski, and Karol Konaszewski. 2022. Resilience and Regulation of Emotions in Adolescents: Serial Mediation Analysis through Self-Esteem and the Perceived Social Support. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19: 8007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szemenyei, Eszter, Melinda Reinhardt, Edina Szabó, Krisztina-Gabriella Szabó, Róbert Urbán, Shane T. Harvey, Antony Morgan, Zsolt Demetrovics, and Gyöngyi Kökönyei. 2020. Measuring Psychological Inflexibility in Children and Adolescents: Evaluating the Avoidance and Fusion Questionnaire for Youth. Assessment 27: 1810–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabachnick, Barbara G., and Linda S. Fidell. 2019. Using Multivariate Statistics, 7th ed. Boston: Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Telzer, Eva H., Jorien van Hoorn, Christina R. Rogers, and Kathy T. Do. 2018. Social Influence on Positive Youth Development: A Developmental Neuroscience Perspective. Advances in Child Development and Behavior 54: 215–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]