Abstract

Blackness, both as a racial identity and a marker of cultural difference, disrupts the hegemonic norms embedded in dominant forms of cultural capital. This article examines how first- and second-generation Haitian and Jamaican communities in Ontario and Quebec negotiate Blackness within a Canadian context. Drawing from international literature, it introduces distinctly Canadian concepts—such as polite racism, racial ignominy, and duplicity of consciousness—to illuminate local racial dynamics. Using Yosso’s (2005) framework of community cultural wealth, the study analyzes six forms of cultural capital—linguistic, aspirational, social, navigational, resistant, and familial—as employed by Afro-Caribbeans to navigate systemic exclusion. The article expands the limited Canadian discourse on Black identity and offers theoretical tools for understanding how cultural capital is shaped and constrained by race in multicultural democracies.

1. Introduction

This article explores the dynamic construction of Blackness in Canada through the lens of cultural capital, with a specific focus on first- and second-generation Afro-Caribbean communities. Drawing on both historical and theoretical frameworks, this work examines how Haitian and Jamaican Canadians negotiate their identities, mobilize cultural knowledge, and assert agency within systems shaped by colonial and racial hierarchies. The analysis reveals that Blackness, while always multifaceted in lived experience, is often constrained by institutional forces in Canada that selectively recognize or suppress cultural expressions. Prior scholarship on Black cultural capital has primarily emerged from U.S. and U.K. contexts. Studies such as Wallace (2017, 2019), Reynolds (2006), and Lamont and Molnár (2002) explore how Black communities develop and deploy cultural capital as forms of resistance, resilience, and identity construction in racially stratified societies. However, these studies often overlook the specificities of the Canadian context, where multiculturalism and bilingualism coexist with systemic anti-Blackness. There remains a need to examine how Black cultural capital operates in Canada, particularly across contrasting provincial contexts such as Ontario and Quebec. This study draws on qualitative interviews and focus groups to analyze how participants mobilize cultural capital while navigating systemic exclusion, offering a grounded perspective on Black identity formation in Ontario and Quebec.

Motivated by economic and political upheavals, many African Caribbean immigrants came to Canada seeking a “better life” (Gooden and Hackett 2020). Their presence has not only influenced the sociopolitical landscape but has also played a central role in the evolving meaning of Blackness in Canada. Afro-Caribbean migration intensified during the mid-20th century, particularly through programs such as the West Indian Domestic Scheme (1955–1967), and later expanded through Canada’s points-based immigration system (Coen-Sanchez 2025). Today, over 257,000 Jamaican Canadians reside primarily in Ontario, while 165,000 Haitian Canadians are concentrated in Quebec (Government of Canada, Statistics Canada 2023). Understanding the historical trajectories and spatial distribution of these communities is essential to examining how cultural capital operates within differing sociopolitical environments. These provinces offer contrasting sociopolitical environments—Ontario shaped by British colonial legacies and Quebec by French cultural nationalism—providing a comparative lens on Black identity formation and cultural capital.

In this article, the term Afro-Caribbean refers specifically to individuals of African descent from the Caribbean, with a focus on Jamaican and Haitian communities in Canada. Black is used as a broader racial category that encompasses diverse diasporic identities, including—but not limited to—Afro-Caribbeans. While these terms are sometimes used interchangeably in Canadian discourse, this article maintains their distinctiveness to acknowledge intra-group differences shaped by nationality, language, migration history, and cultural heritage. Blackness, in turn, is approached not as a fixed identity but as a dynamic and context-specific process of racialization and cultural negotiation.

The focus on Afro-Caribbean Blackness is deliberate. These communities embody a specific intersection of racialization, migration, and cultural resilience that challenges traditional notions of cultural capital. Using Yosso’s (2005) model of community cultural wealth, this article examines how Afro-Caribbean individuals deploy linguistic, familial, social, and navigational capital to navigate Canadian institutions. However, these cultural assets are often undermined or devalued by polite racism—a distinctly Canadian form of racial bias that masks exclusion under the guise of tolerance and civility.

This article argues that polite racism mediates cultural capital in Canada, shaping which expressions of Black identity are legitimized and which are marginalized. Through qualitative methods—semi-structured interviews and focus groups—the study reveals how participants experience what the author terms “racial ignominy” and “duplicity of consciousness,” two mechanisms by which polite racism operates. These processes both inform and constrain how Blackness is constructed, performed, and contested in Canada. Ultimately, the article positions Afro-Caribbean experiences as vital to understanding the intersections between race, culture, and systemic power in a multicultural yet racially stratified society.

This article builds upon prior work exploring Afro-Caribbean migration and Canadian multicultural policy (Coen-Sanchez 2025), particularly the published chapter titled “Navigating Identity and Policy: The Afro-Caribbean Experience in Canada” While that work analyzed the macro-level historical and institutional factors shaping Afro-Caribbean communities in Canada, the current article shifts focus to the micro-level sociocultural mechanisms through which Blackness is constructed, contested, and expressed. Together, these contributions form part of a broader doctoral research project on cultural capital and racialized identity formation among first- and second-generation Haitians and Jamaicans in Ontario and Quebec.

2. Theoretical Framework

In this article, Blackness is understood as both a lived experience and a socio-political construct that is shaped by historical, geographic, and cultural contexts. Globally, Blackness has been formed through colonialism, enslavement, migration, and resistance, giving rise to a multiplicity of identities and cultural expressions. In the Canadian context, Blackness is often situated within a multicultural discourse that obscures racial inequalities, making Afro-Caribbean identities particularly susceptible to polite racism and systemic exclusion. Here, Blackness is not monolithic but dynamic—negotiated through language, heritage, generational status, and resistance to normative frameworks. As such, Blackness is conceptualized as a dynamic and continually evolving construct, shaped through the interplay of community agency and structural forces.

The concept of cultural capital, as first introduced by French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu (1977), encompasses non-financial social assets that facilitate upward social mobility. These assets include knowledge, skills, education, and cultural tastes. Blackness, as a cultural identity, contributes to cultural capital in various ways, shaping experiences, representations, and resistances within societies. For example, Wallace (2017) explores how Blackness impacts the operationalization of cultural capital in local contexts, by highlighting the resistance against ethno-racial representation norms and the unique forms of cultural capital that emerge from Black communities. It is of utmost importance to recognize and respect the diversity of experiences within the Afro-Caribbean communities, as individuals may engage with their culture in unique and distinct ways.

Cultural capital is defined as “instruments for the appropriation of symbolic wealth socially designated as worthy of being sought and possessed” (Bourdieu 1977, p. 488), and has “the capacity to reproduce itself, produce profits, expand and contain the tendency to persist” (Bourdieu 1986, p. 241). In essence, it refers to the knowledge and skill sets that are (re)produced by privileged groups—typically within homes, schools, and institutional spaces—that shape dispositions and influence access to power (Vassenden and Jonvik 2019). Central to this framework is a relational view of social life, which emphasizes the empowering potential of acquiring and mobilizing cultural capital. To understand these dynamics, Bourdieu introduced two key concepts: (a) fields—the structured spaces where individuals occupy objective positions that guide perception and action, and (b) habitus—the internalized dispositions through which people interpret and respond to the world (Bourdieu and Wacquant 2013, p. 275).

Social practices and interactions unfold within structured environments often referred to as social fields—distinct arenas governed by specific values and norms (Bourdieu and Wacquant (2013). Within these fields, individuals accumulate and deploy various forms of symbolic resources—such as language, tastes, credentials, and behaviours—that align with the expectations of their social class. These resources, collectively understood as cultural capital, are not distributed equally; rather, they are reproduced through institutional mechanisms, particularly formal education. As Bennett et al. (2009) explain, educational systems often reinforce privilege by rewarding students who already possess the cultural competencies valued by dominant groups. Parents who are familiar with these expectations are able to prepare their children to excel in such environments, thereby transforming cultural knowledge into credentials that facilitate social mobility.

While foundational, these theories often lack racial specificity and fail to address the nuances of Canadian multiculturalism. This article builds on these frameworks by introducing the concepts of polite racism, racial ignominy, and duplicity of consciousness to better explain how Black cultural capital is uniquely shaped and constrained in the Canadian context. Though Bourdieu’s (1986) theories provide valuable insight into how culture intersects with social stratification, they offer limited explanatory power when it comes to racialized forms of exclusion

Cultural Capital and Community Cultural Wealth

As noted above, while the concept of cultural capital has significantly enriched our understanding of how privileged groups maintain social advantage through cultivated skills, knowledge, and dispositions, it remains theoretically limited in its engagement with race. This gap necessitates a critical interrogation of traditional Bourdieusian interpretations (Bourdieu and Passeron 1990) and invites the incorporation of alternative models—most notably Yosso’s (2005) framework of community cultural wealth—which foreground the lived experiences and cultural assets of racialized communities.

Yosso’s model provides a critical corrective by reframing marginalized groups not through a deficit lens, but through the recognition of their distinct forms of capital. Although originally situated within a Latinx context, this framework has been effectively adapted to Black communities across different national settings. For instance, Wallace (2017) illustrates how Black Caribbean youth in South London mobilize cultural capital to resist racialized institutional norms. Likewise, Rolón-Dow (2011) demonstrates how students of colour—including Black students—in the United States draw upon familial and resistant capital to contest structural inequalities in education. Building on these foundational insights, this study explores how Afro-Caribbean communities in Ontario and Quebec—particularly Haitian and Jamaican Canadians—activate forms of community cultural wealth to navigate systemic racism, especially in its more insidious manifestations such as polite racism and racial ignominy, while simultaneously constructing complex, multi-positional Black identities.

Afro-Caribbean identity, therefore, emerges not as a passive product of institutional forces, but as an actively negotiated process of resistance. Through intergenerational networks, spiritual and cultural communities, and everyday acts of cultural affirmation, these communities challenge the normative boundaries of dominant cultural capital and assert their legitimacy within Canadian society. Yet, as participants’ narratives reveal, these assets are frequently devalued, misrecognized, or erased by prevailing social norms—particularly through subtle mechanisms of exclusion that masquerade as multicultural tolerance.

Mainstream conceptualizations of cultural capital often implicitly equate middle-class status with whiteness, thereby excluding or marginalizing racialized groups. However, as Wallace (2017) contends, cultural capital remains a useful analytic for examining the performance and negotiation of Black identities. Existing research demonstrates that racialized communities employ cultural capital not solely as a means of consumption, but as a strategic resource to assert belonging, contest racial subordination, and foster collective identity (Lamont and Molnár 2002). Importantly, this includes forms of resistant capital—defined as knowledge, skills, and practices cultivated through oppositional engagement with systems of oppression (Freire 1970; Delgado Bernal 1997; Solórzano and Delgado Bernal 2001). Such resistance is historically grounded in the defiant legacies of racialized groups, including Indigenous communities (Deloria 1988), whose cultural persistence has long challenged colonial systems of domination.

This research adopts an intergenerational lens to examine the transmission and transformation of cultural capital within Afro-Caribbean communities, with particular attention to the enduring impact of colonial histories, linguistic heritage, and cultural traditions. Participants frequently described the strategic deployment of social networks to circumvent institutional exclusion—an illustration of navigational capital homed in response to systemic barriers.

This conceptual framework guided the study’s analytical approach. It enabled a nuanced investigation of the ways in which Blackness mediates access to dominant cultural capital and influences broader patterns of social reproduction. Cultural capital, as this study demonstrates, is neither static nor universal; its construction and utility are shaped by historical trajectories, racialized experiences, geographical contexts, and the positionality of those who hold it. A recurrent finding across the data was the pervasive experience of polite racism among both first- and second-generation Haitian and Jamaican participants, underscoring the subtle yet persistent nature of racial exclusion in the Canadian context.

3. Methodology

This study applies principles of grounded theory to examine how first- and second-generation Haitian and Jamaican participants experience and mobilize cultural capital within Canadian institutions. Grounded theory was chosen for its emphasis on deriving conceptual insights from participants’ narratives rather than imposing pre-existing theoretical frameworks (Brady and Loonam 2010). Although the goal was not to generate a formal theory in the Glaserian or Straussian sense, grounded theory principles guided the coding process and thematic development. This flexible approach enabled the emergence of nuanced concepts—such as polite racism, racial ignominy, and duplicity of consciousness—that authentically reflect participants’ lived realities.

Data were collected through twelve focus group discussions and analyzed iteratively until thematic saturation was reached—when no new themes or insights emerged. The analytical process began with line-by-line open coding to identify meaningful units and emergent concepts. This was followed by axial and selective coding to examine interrelationships among categories and refine core themes. The analysis was inductively driven, allowing theoretical insights to emerge directly from participant narratives. To ensure analytical rigor, the researcher engaged in memoing, reflective journaling, and multiple transcript reviews. Member checking was employed to validate interpretations with participants. As all coding was conducted by the researcher, intercoder reliability was not applicable.

This qualitative research employed semi-structured focus group interviews with first- and second-generation Haitian and Jamaican participants residing in the Ottawa-Gatineau region. Participants were selected based on self-identified Afro-Caribbean heritage and generational status to explore how cultural capital is enacted in everyday life. The sample included men and women aged 25 to 45. Focus groups were chosen over individual interviews to foster dynamic, collective discussions that revealed shared cultural meanings, intergenerational contrasts, and community-based understandings of Blackness and cultural capital (Guba and Lincoln 1994; Barbour 2007). This format allowed participants to build on each other’s narratives, facilitating the identification of communal strategies of resistance and institutional navigation. As Krueger and Casey (2015) note, focus groups are particularly effective in eliciting cultural insights that may remain unspoken in one-on-one settings.

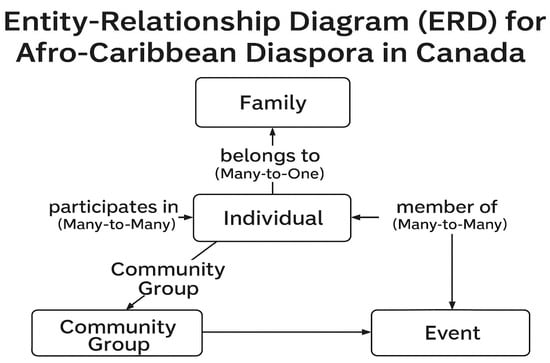

To complement the relational dimension of grounded theory, an entity-relationship diagram (ERD) was constructed to visualize how participants’ interactions with institutions, communities, and each other shaped their access to social and cultural capital. This tool proved instrumental in mapping intersections of generational status, regional context, and institutional engagement. These relational dynamics are visualized in Appendix A, which maps the connections between individuals, families, and institutions within Afro-Caribbean communities.

Theoretical sampling was used to refine emerging themes (Ligita et al. 2022). Eligible participants self-identified as Haitian or Jamaican and were either first-generation (born outside Canada) or second-generation (born in Canada to at least one immigrant parent). All participants completed informed consent forms and underwent pre-screening to confirm eligibility. Sessions were audio-recorded with participant permission and transcribed.

Twelve focus groups were conducted—six with Haitian participants and six with Jamaican participants. Each group included three to five individuals and was stratified by generation to examine intergenerational differences in the mobilization of cultural capital. Participants were recruited through snowball sampling, with outreach concentrated in Ontario and Quebec to reflect regional population distributions. Haitian participants were drawn from both provinces, while Jamaican participants were recruited exclusively from Ontario. Generational representation varied due to participant availability during recruitment.

Table 1 presents generational perspectives on cultural capital among Afro-Caribbean Canadians, illustrating how first- and second-generation participants draw on different forms of capital in navigating social, educational, and institutional contexts.

Table 1.

Generational Perspectives on Cultural Capital among Afro-Caribbean Canadians.

Participants responded to questions concerning how cultural identity shaped their navigation of Canadian institutions, including education, employment, and healthcare. Additional questions probed the role of cultural and social capital in shaping these experiences. Transcript analysis focused on participants’ perceptions of the advantages and disadvantages associated with identifying as Haitian or Jamaican, the influence of generational status, and the everyday significance of cultural heritage.

4. Key Findings

This section presents the primary findings derived from focus group discussions conducted with first- and second-generation Haitian and Jamaican participants. The analysis reveals that Afro-Caribbean communities possess rich and varied forms of cultural capital—including familial, linguistic, social/navigational, and resistant capital. However, these assets are frequently devalued or rendered invisible within Canadian institutional contexts. Participants consistently reported navigating systemic barriers through strategies such as code-switching, informal networking, and intergenerational resilience. At the same time, their narratives illuminate the pervasive influence of polite racism, particularly as expressed through mechanisms of racial ignominy and duplicity of consciousness, both of which shaped their identity formation and limited access to opportunities.

The findings are organized around the most salient forms of cultural capital identified in the data. Table 2 below outlines the key themes emerging from the focus group discussions, categorized by type of capital and perceived impact (advantage, disadvantage, or neutral) across generational and ethnonational lines. This thematic mapping reflects both shared and distinct experiences between first- and second-generation Haitian and Jamaican participants. By examining how cultural assets are activated, muted, or obstructed, the analysis captures how individuals negotiate institutional settings, community expectations, and racialized identity formation.

Table 2.

Thematic Summary of Social and Cultural Capital Impacts by Group and Generation.

Key Takeaways include:

- Linguistic Capital: Demonstrated minimal professional advantage, though socially beneficial within community contexts.

- Social/Navigational Capital: Crucial in overcoming institutional and systemic barriers, especially through code-switching and cultural adaptability.

- Familial Capital: Served as a foundational resource for community engagement and personal resilience.

- Code-Switching and Racial Ignominy: Emerged as critical adaptive strategies in navigating polite racism and exclusionary norms.

While multilingualism is often linked to cognitive and professional benefits—such as enhanced task-switching and divergent thinking (Abrar-ul-Hassan 2021)—participants did not perceive their linguistic capital (e.g., speaking both French and English) as advantageous in Canadian institutional settings. Echoing Bilecen et al.’s (2023) findings on the challenges faced by international students educated in a foreign language, Haitian participants in particular noted that language proficiency did not shield them from discrimination. Instead, participants emphasized how racial and ethnic markers, particularly accent and skin color, were dominant in shaping institutional interactions. One first-generation Haitian participant, who had immigrated to Quebec in her early twenties, recalled a particularly painful job interview experience that revealed the limits of her linguistic capital in formal institutions: “I didn’t get the job because they said they couldn’t understand my accent”. This narrative illustrates how Afro-Caribbean multilingualism—often viewed as a strength within community spaces—becomes a liability within dominant institutions shaped by linguistic nationalism and racial hierarchies. Although fluency in both French and English might theoretically signal strong cultural capital, it is devalued when filtered through racialized perceptions of accent and legitimacy. This experience exemplifies racial ignominy, where institutional rejection is cloaked in seemingly neutral standards like “comprehensibility,” but in practice, reflects a deeper discomfort with non-dominant forms of cultural expression. The participant’s account also reflects the everyday reality of polite racism in Quebec, where exclusion is expressed through civility and framed as a technical concern rather than a racialized judgment.

Geographical context was also considered in the analysis. While participants resided in both Ontario and Quebec, those in Quebec—particularly in smaller urban or rural settings—reported heightened isolation and fewer accessible community supports. This regional variation reflects differing provincial dynamics: Quebec’s emphasis on cultural preservation and language policy shapes multicultural and immigration experiences differently than Ontario’s more Anglophone and British-colonial framework. Regardless of region, however, all participants described encountering polite racism in various forms.

Age range was also examined (participants were between 25 and 45 years old), yet generational status—first-generation immigrant versus Canadian-born—proved more influential in shaping identity and perceptions of cultural capital. First-generation participants often emphasized the necessity of assimilation, sometimes at the cost of cultural retention, in pursuit of stability and opportunity. By contrast, second-generation participants tended to be more vocal in asserting their identities and critiquing systemic inequities. One second-generation participant explained: “My mental flexibility—due to my experiences—I am able to code-switch and navigate, and thus, survive in modern-day Canada.” This illustrates how code-switching functions both as a survival mechanism and a navigational tool in racially stratified spaces, aligning with Yosso’s (2005) concept of navigational capital as a skill developed to manage hostile or exclusionary environments.

Familial capital, passed down intergenerationally, played a critical role in shaping participants’ values and coping strategies. For example, one Jamaican participant stated: “I come from a long line of women who, in the face of being told ‘No,’ will continue to do their thing and succeed by any means necessary”. This testimony highlights the enduring influence of intergenerational resilience and cultural knowledge as key dimensions of familial capital.

Participants also noted that their cultural identities—whether Haitian or Jamaican—were publicly celebrated during cultural events and festivals (e.g., Toronto Caribbean Carnival, Afrofest), which served as vital affirmations of belonging. One participant commented, “Celebrating our cultural festivals keeps our heritage alive,” while another emphasized, “Having a close-knit community helps me feel connected to my roots.” These affirmations resist cultural erasure and foster a sense of joy and identity continuity. Still, participants expressed ambivalence about diversity and inclusion (EDI) initiatives, warning that such recognition often occurred within tokenizing frameworks.

Ultimately, this study reveals the diverse ways Afro-Caribbean communities mobilize various forms of cultural capital to confront and navigate structural inequalities in Canada. Despite persistent exposure to polite racism and other forms of systemic exclusion, participants exhibit resilience through strategies of cultural resistance and intergenerational strength. These findings underscore the importance of recognizing and validating non-dominant forms of cultural capital within institutional policies and practices. Crucially, the research suggests that the mobilization of cultural capital is shaped by social stratification and informed by hegemonic standards of value. The systemic marginalization of community-based forms of capital represents a significant barrier to genuine inclusivity in Canadian institutional life.

5. Discussion

This section analyzes how Afro-Caribbean cultural capital interacts with dominant Canadian social structures. Drawing from the study’s key findings, it explores the nuanced construction of Blackness in relation to dominant cultural capital, institutional power, and intergenerational identity. Emphasis is placed on familial and navigational capital, highlighting the tension between resistance and accommodation in the face of polite racism.

While this study foregrounds the shared experiences of Afro-Caribbean communities across Canada, important regional distinctions between Ontario and Quebec also shaped participants’ navigation of Blackness and cultural capital. In Ontario, participants described accessing larger diasporic networks and greater visibility of Afro-Caribbean cultures in public spaces, which facilitated the expression of familial and resistant capital. In contrast, Quebec’s emphasis on French language and cultural assimilation introduced additional barriers, particularly for Haitian participants, whose multilingualism was often undervalued or treated with suspicion. The province’s intercultural model—prioritizing integration into a dominant francophone culture—further constrained linguistic and navigational capital (Bouchard and Taylor 2008; Coen-Sanchez 2025). Participants in Quebec more frequently reported feelings of cultural isolation and institutional neglect, suggesting that the politics of recognition operate differently across provincial lines. These regional dynamics underscore that Blackness in Canada is not only shaped by national discourse but is also contextually negotiated within provincial frameworks that mediate access to cultural resources and institutional legitimacy.

To deepen this framework, the article introduces the concept of transferable racial confluence—defined as the intergenerational transmission of racialized knowledge, cultural memory, and survival strategies within the Afro-Caribbean diaspora. Drawing on Hall’s (1996) conception of cultural identity as fluid and continually produced, and Gilroy’s (1993) theorization of diasporic memory, this concept captures how racial consciousness is not only constructed but also shared across time and space. In the Canadian context, Afro-Caribbean communities carry forward ancestral legacies shaped by Haiti’s and Jamaica’s colonial histories—resistance, pride, trauma—and rework them in response to systemic exclusions such as polite racism and institutional erasure. This confluence is at once emotional, political, and strategic. It forms a collective racial literacy that evolves through dialogue with dominant cultural norms and institutional frameworks.

Unlike familial capital, which centers kinship and the preservation of cultural knowledge within households, transferable racial confluence emphasizes the dynamic, strategic, and often collective reproduction of racialized consciousness across generations and communities. It includes diasporic interactions, community organizing, and institutional encounters that cultivate a shared racial awareness. Here, racial identity is not a fixed inheritance but a living praxis—adapted and transmitted in response to exclusion, cultural affirmation, and political resistance. A first generation Hatian participant powerfully articulated this dynamic:

“I didn’t know what racism was in Haiti. But my mom always told me how to act around police, how to speak at work. It’s like she prepared me for a battle I didn’t even know I was going to fight.”

This quote exemplifies transferable racial confluence as a form of lived pedagogy—an embodied practice of racial preparedness and identity formation that bridges ancestral knowledge with contemporary realities. It is not merely cultural inheritance but a deliberate, strategic adaptation to racialized environments, shaped by the foresight of previous generations.

Building on Gillborn’s (2005) theory of institutional racism, this study conceptualizes polite racism as embedded in the expectations, discourses, and procedures of Canadian institutions. Practices such as race-neutral hiring, academic streaming, and healthcare dismissiveness are framed in the language of civility, yet function to reproduce systemic racial hierarchies. Polite racism is not merely interpersonal—it is a form of governance that determines whose cultural capital is recognized and whose is rendered invisible.

Though uniquely expressed in Canada, polite racism has parallels in other national contexts. Concepts such as racismo cordial in Brazil (Turra and Venturi 1995), Frankenberg’s (1993) color-evasive racism, and Goldberg’s (2008) work on the postracial state reflect similar patterns of racial evasion and structural exclusion. This study does not claim polite racism to be exclusive to Canada, but rather explores its particular articulation through institutional aesthetics of civility, procedural neutrality, and multicultural rhetoric that obscure exclusion while maintaining its effects.

Polite racism operates through two interrelated mechanisms explored further in this article: (1) racial ignominy, and (2) duplicity of consciousness. While polite racism may manifest as subtle interpersonal slights or questioning of one’s legitimacy, its most profound impacts are structural. It is embedded in policies that appear neutral but disproportionately disadvantage Black individuals—such as the devaluation of foreign credentials in employment, racialized streaming in education, or the dismissal of medical symptoms in healthcare. These practices uphold racial hierarchies under the guise of politeness and procedural fairness.

The sociohistorical contexts of Haiti and Jamaica provide essential foundations for understanding the intergenerational transmission of capital. Haiti’s 1804 revolution and Jamaica’s postcolonial affirmations remain vital to community narratives of strength, resistance, and pride, shaping how participants understand identity and belonging in Canada. Even more recent political events, such as Haiti’s defiance of UN sanctions through the port of Jacmel in the 1990s (Pushpalingam 2023), are seen as part of this legacy—more than historical facts, they represent pivotal chapters in Black migration history (C. J. Robinson 1983).

Participants brought various forms of capital to Canada, including economic resilience and social resistance. Many described maintaining stable households and supporting extended families abroad while navigating racial barriers in Canada—demonstrating high levels of financial literacy, adaptability, and familial responsibility. Both Jamaican and Haitian participants expressed intergenerational tenacity, often rooted in matrilineal traditions of care and leadership. The strength and perseverance passed down through generations of women were frequently cited as foundational to their ability to endure systemic challenges.

A second-generation Jamaican participant, reflecting on the legacy of her grandmother and mother, emphasized how this emotional and cultural inheritance shaped her worldview:

“It is that energy that has been passed down from generation.”

This seemingly simple statement encapsulates a powerful form of familial capital—one grounded in the emotional resilience, practical wisdom, and cultural pride transmitted through Black matrilineal lines. The participant’s invocation of “energy” speaks to an affective force that transcends material circumstances. It represents not just familial memory but also a political ethic of perseverance and collective survival.

Framed within Yosso’s (2005) model of community cultural wealth, this quote illustrates how second-generation Afro-Caribbean individuals actively draw on ancestral knowledge to navigate the racialized structures of Canadian society. It also points to the continuity of resistance between generations, challenging dominant narratives that frame immigrant families as starting from cultural or social deficits. Rather than being disconnected from their heritage, second-generation participants expressed a sense of rootedness—reclaiming and reactivating familial legacies as tools of empowerment in the face of polite racism and systemic exclusion.

This analysis challenges traditional notions of cultural capital as primarily related to elite tastes or consumption habits. Instead, it highlights how Afro-Caribbean cultural capital—familial, linguistic, navigational, and resistant—is rooted in struggle, survival, and strategic adaptation. These elements are deeply embedded in Afro-Caribbean histories. Haitians carry the legacy of the only successful enslaved revolt in the Western Hemisphere, grounding aspirational, familial, and resistant capital in national pride. Similarly, Jamaican participants draw on traditions of anti-colonial resistance and Pan-African pride (C. J. Robinson 1983). Jamaican Patois is more than a language—it is a symbol of cultural resistance and diasporic identity (Lamont and Molnár 2002).

Jamaican participants in particular drew on a rich legacy of resistance and cultural pride that informs their community cultural wealth. Jamaica’s history of rebellion, including the enduring influence of Pan-Africanism, has fostered values of autonomy, dignity, and collective identity. These histories generate forms of resistant capital, transmitted intergenerationally through self-reliance and sociopolitical awareness. Linguistic and familial capital are central, with Jamaican Patois serving as both a communicative tool and a marker of identity, solidarity, and resistance. These elements shape how Jamaican Canadians assert their identity in the face of racial marginalization, particularly through code-switching, cultural resilience, and strategic navigation of Canadian institutions (Yosso 2005). Code-switching—the strategic shifting of language, behavior, or expression across social contexts—was described by participants as a method of navigating white-dominated institutional spaces while maintaining their Afro-Caribbean identity in familial and community settings.

5.1. Polite Racism in Multicultural Canada

Polite racism refers to a subtle and socially sanctioned form of racial bias, often expressed through programmed emotional responses toward individuals based on their skin tone. It often operates unconsciously and is masked by civility, making it difficult to confront directly. In Canada, polite racism is challenging to identify and detect, as it hides behind smiles and welcoming gestures. Polite racism, as described by participants, refers to attitudes or behaviours that appear courteous or non-hostile on the surface but are deeply racialized in their implications and effects. It is often expressed through seemingly innocuous interactions that mask racialized assumptions about belonging, success, and legitimacy.

One second-generation Haitian participant recalled an unsettling dinner experience that exemplified this phenomenon. After her family moved into a predominantly white gated community, they were invited over by a neighbour under the guise of a warm welcome. However, the conversation soon took a different turn:

“They kept asking us, like—‘So where do you work? How did you afford this house? You must’ve worked really hard to get here!’ It felt like they were trying to figure out how we fit in… like we weren’t supposed to be there.”

To the uncritical eye, such questions may appear to be routine attempts to “get to know someone.” But for the participant, these inquiries carried racial undertones, framed by the presumption that Black success in affluent, white-dominated spaces requires explanation or justification. The implication wasn’t curiosity—it was surveillance. These micro-interrogations, delivered with a smile, were interpreted as racial boundary-marking, subtly signaling that the family was an exception to presumed norms about who belongs in such neighborhoods.

This vignette exemplifies the uniquely Canadian manifestation of polite racism, where racial exclusion is softened through civility and presented as politeness or concern. Unlike overt hostility, these exchanges rely on social scripts of friendliness and inclusivity, making them harder to challenge. In this sense, polite racism operates not only at the interpersonal level, but also structurally, reinforcing the conditional acceptance of racialized people in spaces coded as white and middle-class. By theorizing these moments through the lens of polite racism, we see how civility can serve as a mechanism for racial othering within the national mythos of multicultural tolerance.

Additionally, several participants described a subtler yet equally damaging dynamic: a deliberate ignoring or invalidating of their expertise and lived experience. This form of exclusion operates not through overt rejection, but through strategic silence or polite dismissal. A second-generation Jamaican participant, now a doctoral student in clinical psychology, recounted the persistent disregard she faces within healthcare systems:

“I’m ignored heavily within the mental health and physical health care system, despite being a doctoral student in clinical psychology. I’m often told that my pain is not real.”

This testimony illustrates how racialized individuals—even those with significant academic and professional credentials—can be rendered invisible in systems that claim neutrality. Her professional status did not shield her from assumptions about Black women’s bodies and emotions, revealing a deeper structure of disbelief rooted in anti-Blackness. Such dismissal exemplifies polite racism—it is cloaked in institutional language of professionalism and concern, but its effects are exclusionary and racialized.

From this foundation, I introduce the concept of racial ignominy as an extension of polite racism. Traditionally associated with disgrace or shame, racial ignominy refers here to the normalized, often socially sanctioned shaming of Afro-Caribbean identities through subtle mockery, invalidation, and cultural degradation. These processes are frequently couched in humor or curiosity but have harmful consequences.

For instance, participants described being told:

“OMG, you eat that? That food smells!”

“You guys eat with your hands?”

Such remarks, while presented as harmless, reinscribe whiteness as normative and cast Afro-Caribbean cultural practices as deviant. These microaggressions are not isolated incidents but part of a broader system of cultural devaluation. Another second-generation Jamaican participant described how even physical presence prompted assumptions:

“People would assume I grew up in a rough area because of my skin. It’s like, you’re never allowed to just be.”

Racial ignominy, then, operates at the intersection of social exclusion, cultural disrespect, and institutional invalidation. It not only imposes a burden of emotional self-regulation but contributes to the internalization of shame and cognitive distortion. This was reflected in yet another comment from a second-generation Jamaican participant, who recounted:

“White peers would say, ‘Y’all all smoke weed.’ And when I got offended, it was like—‘Relax, it’s just a joke!’”

Such gaslighting obscures the racialized nature of these interactions, shifting blame onto the person experiencing harm and reinforcing a broader system of dismissal. In theorizing racial ignominy as a culturally embedded and structurally supported mechanism of polite racism, this manuscript highlights how everyday exchanges reproduce racial hierarchies while evading critique through civility.

Building on W.E.B. Du Bois’s theory of double consciousness, the author introduces the concept of duplicity of consciousness to describe a uniquely diasporic psychological rupture. Subsequently, the duplicity of consciousness is relational and consequential to the false imagery associated with immigrating to Canada/the West. This concept draws partial inspiration from W.E.B. Du Bois’s theory of double consciousness, which describes the internal conflict of seeing oneself through the lens of a racially dominant society. However, duplicity of consciousness is distinct in that it reflects the tension Afro-Caribbean migrants experience between the internalized promise of social mobility through immigration and the lived realities of racial exclusion in Canada. Where Du Bois ([1903] 1994) articulated double consciousness as a dual awareness shaped by the tension between Black identity and white societal norms, duplicity of consciousness adds a temporal and migratory dimension. It captures the psychological dissonance experienced by immigrants whose imagined futures in the ‘Global North’ clash with the racialized structures they encounter upon arrival. This internal fracture—between aspiration and disillusionment—is a uniquely diasporic betrayal of inclusion. Unlike double consciousness, which emphasizes dual awareness, duplicity of consciousness underscores a sense of ontological ambush: the moment when the immigrant’s imagined Canada dissolves under the weight of polite racism and structural exclusion

Both concepts engage with internalized conflict in racialized subjects, but duplicity of consciousness does not refer to a dual social identity. Du Bois’ double consciousness is rooted in the simultaneous awareness of being both Black and American in a society that devalues Blackness. In contrast, duplicity of consciousness speaks to a temporal and psychological rupture—a betrayal of anticipated belonging. The disillusionment arises not from “twoness,” but from the collapse of a projected future. This concept captures the discrepancy between hope and experience, between promised inclusion and systemic exclusion, emphasizing the migratory and anticipatory dimensions of racialized disappointment in the Canadian context. For example, several first-generation participants described moments of internal conflict—feeling that the Canada they had imagined prior to immigration did not match their lived experience. They recounted needing to suppress frustration, modify their behavior, or remain silent in the face of exclusion in order to maintain employment or be accepted in professional settings. This emotional and psychological dissonance reflects what I conceptualize as a duplicity of consciousness—a rupture between the internalized promise of opportunity and the reality of systemic racial barriers. This dual awareness, shaped by both hope and betrayal, surfaced repeatedly as participants spoke about adjusting their identity, expectations, and self-presentation to navigate Canadian institutions.

While I acknowledge that the phenomena described by duplicity of consciousness and racial ignominy may have precedents in existing scholarship and lived experience, these terms are developed here as original conceptual tools within a distinct analytical framework. Duplicity of consciousness captures the rupture between aspirational migration and racialized disillusionment, while racial ignominy highlights the intergenerational psychic toll of subtle cultural degradation. By articulating and applying these concepts to Afro-Caribbean experiences in Canada, I aim to illuminate under-theorized dimensions of diasporic life. These terms are introduced with the understanding that conceptual development is iterative, and I anticipate their refinement through future research and scholarly dialogue

Consequently, there is a widely held belief among many first-generation Haitians and Jamaicans that the only viable path to a “better life” is through immigration. This perception—deeply rooted in structural inequalities and economic hardship—was a recurring theme in participants’ narratives. It reflects the aspirational hope that, through hard work and resilience, life circumstances will improve in the host country. Yosso (2005) defines aspirational capital as the “hopes and dreams” maintained even in the face of real and persistent barriers. She notes that despite ongoing social disparities in education, African American youth and their families often continue to hold high expectations for academic achievement (Yosso 2005, p. 77).

This aspect of hope is used as a means to lure people from the Caribbeans to immigrate to Canada in an attempt to either “solve” their current issues or provide more opportunities when in reality, it is a means to increase racial capitalism. Racial capitalism is a concept that highlights how racial hierarchies and economic exploitation are interlinked, suggesting that capitalism has historically thrived on racial discrimination to maximize profits (L. Robinson 2000). It argues that economic systems often maintain and exploit racial divisions to sustain wealth accumulation, reinforcing social and economic inequalities along racial lines (L. Robinson 2000). Furthermore, racial ignominy is the betrayal of a racial confluence and is used as a means to isolate people through deferential approaches.

A transferable racial confluence, a term the author uses to describe the transmission of racial experiences and perceptions from one generation to the next, is a key aspect of the formation of Black identity in Canada. The first generations often experience a duplicity of consciousness, an illusion of “living a better life” that is quickly overturned by social barriers. This experience conflicts with the advertised image of Canada being a “problem-solving country.” This betrayal integrates with the Western’s perception of Blackness and, in turn, influences the formation of the Black identity: How is Blackness constructed in Canada? It is through a process of encoding and decoding the prescribed racial barriers of a specific region in relation to time and space. Hence, attributing certain traits to one’s identity is a means of survival and social adaptability. This becomes the identity of Blackness. This relationship can highlight both the systemic barriers that Black individuals often face in accumulating social capital due to racial discrimination and biases, as well as the unique forms of community support, resilience, and cultural wealth found within Black communities. Understanding this dynamic is crucial for addressing inequalities and fostering inclusive environments where social capital is equitably accessible to all racial and ethnic groups.

Blackness, cultural capital, and polite racism are interrelated concepts that frame the lived experiences of Afro-Caribbean communities in Canada. Blackness is approached not as a fixed identity but as a dynamic, context-specific process shaped by both historical resistance and contemporary negotiations of belonging. Cultural capital—especially in the form of community cultural wealth—is central to how Black Canadians navigate systems designed to privilege dominant norms. However, in the Canadian context, cultural capital is filtered through the lens of polite racism, which subtly delegitimizes non-white forms of knowledge, behaviour, and identity. Polite racism operates by embracing surface-level multiculturalism while covertly reinforcing racial boundaries, influencing which cultural resources are validated and which are dismissed. By bringing these concepts together, this research explores how Blackness is constructed and contested through acts of cultural affirmation and institutional resistance, revealing the nuanced ways Afro-Caribbean Canadians assert agency within a racialized landscape.

While this study is grounded in a sociological analysis of cultural capital, it is also informed by foundational Black Canadian and diasporic thinkers such as Rinaldo Walcott (2003) and Stuart Hall (1996), whose work emphasizes the fluid, constructed, and contested nature of Black identity across space and time. Their insights into racialized belonging and cultural erasure inform this article’s focus on how Afro-Caribbean Canadians negotiate Blackness within institutional contexts shaped by polite racism.

This study also acknowledges the foundational contributions of Dionne Brand (2001), Katherine McKittrick (2006), Peter James Hudson (2017), Aaron Kamugisha (2019), and C.L.R. James ([1938] 1989), whose critical work in Black Canadian, Caribbean, and diasporic thought continues to inform contemporary understandings of Black identity, resistance, and epistemology.

These dynamics reveal how multiculturalism can serve as a façade that conceals structural inequities while subtly reinforcing dominant racial norms. Building on this, the concept of polite racism also resonates with international frameworks such as Eduardo Bonilla-Silva’s (2006) theory of colorblind racism, which highlights the systemic reproduction of racial inequality through seemingly race-neutral practices and discourse. Similarly, Prudence Carter’s (2005) concept of non-dominant cultural capital complements this study’s use of Yosso’s framework by showing how marginalized groups’ cultural knowledge and assets are often devalued within institutional contexts. While Carter focuses primarily on educational settings in the U.S., her argument reinforces the broader claim that cultural capital is shaped and constrained by dominant norms. Including these perspectives further situates polite racism as part of a broader spectrum of racialized misrecognition, while also highlighting the distinct ways such exclusion operates in Canada’s multicultural context.

5.2. Familial Capital and Zones of Cultural Safety

Participants noted that community hubs—such as cultural centres, churches, and food festivals—offered spaces where they could express their identities without fear of judgment. One Jamaican participant stated, “At Caribana, I feel like I’m allowed to be myself without code-switching. It’s the one time I don’t feel like I have to explain who I am.” These spaces operate as temporary zones of cultural affirmation—sites of resistance to the subtle but persistent pressures of polite racism.

Historically, Afro-Caribbean communities in Toronto have built such spaces to preserve cultural identity and foster solidarity (Toney 2010). These zones of familial capital are integral in sustaining traditions, intergenerational knowledge, and a sense of belonging. They operate not only as sites of cultural continuity but also as mechanisms of resistance against dominant forms of cultural erasure.

5.3. Dominant Cultural Capital and the Misrecognition of Blackness

The concept of dominant cultural capital elucidates how dominant groups and institutions set the norms that define legitimacy (Bourdieu 1986). Afro-Caribbeans in Canada navigate these social spaces while having their cultural identities stigmatized. This contributes to the need to renegotiate identity in a context that often invalidates their heritage.

Participants grappled with combining their Caribbean heritage and Canadian expectations. First-generation individuals often lacked a prior attachment to “Blackness” as a racial category; in contrast, second-generation participants internalized and adapted to this concept through both cultural ancestry and Canadian racial politics. Wallace (2019) describes this dynamic cultural capital as shaped by metropolitan norms yet rooted in Caribbean tradition. Blackness is thus not monolithic but adaptive—an “algorithm of thoughts” comprising multi-histories and practices. It becomes a tool for survival, rooted in linguistic, artistic, and spiritual expressions that resist assimilation. Yet dominant cultural norms continue to misrecognize these assets. In education, for example, curricula often fail to reflect Afro-Caribbean histories (Coen-Sanchez 2021), resulting in barriers to academic success and cultural alienation. In the workplace, professionalism is often equated with whiteness, and media representations of Blackness remain narrowly framed. As one Haitian participant recounted, “I had the degree, the language, but I was still told I didn’t ‘fit.’” This misrecognition is not a failure of credentials but of cultural translation—where Blackness is filtered through dominant norms and found lacking.

5.4. Navigational Capital and Intergenerational Resistance

Despite systemic exclusions, Afro-Caribbean communities exhibit a deep capacity for resilience rooted in intergenerational knowledge and adaptive strategies. Participants described developing context-specific tools—such as code-switching, cultural modulation, and informal support systems—to engage with institutions often unresponsive to their realities. These strategies reflect navigational capital: the ability to move through and around dominant structures while retaining a sense of self. What emerged clearly was that these forms of capital were not improvised individually but nurtured through familial guidance and community insight. First-generation participants often imparted unspoken rules of survival—how to behave in professional settings, when to stay silent, when to speak up—lessons shaped by their own encounters with polite racism. Second-generation participants extended these teachings, applying them within their workplaces, schools, and social environments. This intergenerational transfer of cultural navigation skills exemplifies how resistance is taught, internalized, and reimagined. Moreover, participants shared how they co-created spaces—festivals, churches, and peer circles—where Afro-Caribbean identity could be expressed without surveillance. These environments offered not just emotional safety but critical opportunities for exchanging institutional knowledge, cultivating belonging, and reclaiming cultural agency.

In this way, navigational capital operates at the intersection of personal adaptation and collective resilience. It equips individuals with the tools to engage with dominant systems on their own terms, while preserving cultural integrity and fostering intergenerational continuity.

6. Strengths and Limitations in Research

In qualitative research, both strengths and limitations are integral to the research process. A key strength of this study lies in its focus on the lived experiences of Afro-Caribbean communities in Canada—specifically Haitian and Jamaican individuals—through an intergenerational lens. By foregrounding race, migration, and cultural capital, the study offers critical insight into how systemic exclusion operates within Canadian institutions and how cultural knowledge is mobilized as resistance. The grounded theory approach allowed for the emergence of nuanced concepts, such as polite racism, racial ignominy, and duplicity of consciousness, directly from participants’ narratives.

Participants expressed how race intersects with other identities, including gender, class, and immigration status. However, while gender was acknowledged in the sample composition—ensuring the inclusion of both men and women—it was not prioritized as a central analytic category. This decision was methodological, guided by the study’s core aim to explore how Blackness and cultural capital are shaped intergenerationally and regionally across two specific diasporic communities. As such, while gendered dynamics were present in participant narratives, they were not systematically analyzed. Future research should more explicitly interrogate how gender mediates the expression and recognition of cultural capital, particularly as it relates to institutional navigation and identity construction.

Limitations include challenges in operationalizing social capital, which involves trust, norms, and cohesion—qualities difficult to quantify. However, the use of ERD diagrams minimized misinterpretation by systematically mapping the relationship between immigration and identity. Future studies could incorporate hybrid methods and longitudinal approaches to track the evolution of cultural capital over time and better understand its long-term impacts.

Additionally, this study is geographically limited to participants residing primarily in the Ottawa-Gatineau region, with Jamaican participants recruited exclusively from Ontario. As such, the findings may not fully reflect the diversity of Afro-Caribbean experiences across Canada—particularly in major urban centers like Toronto and Montreal, where community density, linguistic dynamics, and multicultural infrastructure may shape identity differently. For example, Toronto’s expansive Caribbean diaspora may offer more robust forms of institutional recognition, while Quebec’s distinct language policies may impose unique pressures on Haitian participants. These geographic distinctions suggest that while the core themes of polite racism, racial ignominy, and cultural capital are broadly relevant, their expressions may vary regionally. Future research should aim to include participants from a wider range of urban and provincial contexts to enhance the generalizability and depth of analysis.

Moreover, although the study included both men and women across focus groups, gender was not prioritized as a central analytic focus. This was a methodological decision aligned with the study’s primary aim: to examine the intergenerational and regional negotiation of Blackness and cultural capital among Afro-Caribbean communities. While gendered experiences likely shaped participants’ interactions with institutions, they were not systematically coded or theorized in this iteration. Future studies should explicitly engage gender as an intersecting dimension of identity to better understand how it mediates the recognition, expression, and mobilization of cultural capital within racialized contexts

7. Implications for Policy and Future Scholarship

The findings of this study underscore the limitations of Canada’s multicultural framework, which, while inclusive in discourse, often fails to substantively recognize the cultural wealth of Afro-Caribbean communities. Subtle forms of exclusion—conceptualized here as polite racism—undermine the legitimacy of assets like multilingualism, intergenerational knowledge, and communal solidarity

This study contributes to Canadian sociology by examining how Afro-Caribbean communities in Canada mobilize cultural assets to navigate and resist systemic exclusion. It foregrounds polite racism as a uniquely Canadian mechanism of marginalization, highlighting how Haitians and Jamaicans draw on inherited knowledge, intergenerational resilience, and community strength not only to survive, but to challenge, structures of inequality. Central to this resistance is what this study terms duplicity of consciousness: the tension between inherited hope and lived systemic exclusion.

These findings deepen our understanding of how systemic racism is negotiated through everyday practices. The concept of polite racism helps to explain how discrimination is often masked behind institutional civility, producing exclusion through silence, deflection, or tokenism. Meanwhile, duplicity of consciousness captures the internalized complexity many Black individuals face in reconciling their public and private identities. These concepts offer a nuanced lens for interpreting how Afro-Caribbean communities mobilize, adapt, and resist within the racialized structures of Canadian multiculturalism, even when their cultural capital remains undervalued or obstructed.

The implications are significant. Educational institutions must adopt culturally sustaining pedagogies, and employers should implement equity-informed hiring and promotion strategies that recognize the depth of Afro-Caribbean expertise. Most importantly, Black communities must be engaged as co-creators—not merely subjects—of structural reform. Future research should explore how different forms of cultural capital are racialized across regional, generational, and linguistic contexts in Canada, with particular attention to resistant capital as a community-driven tool for reshaping institutions and contesting monolithic constructions of Black Canadian identity.

For extended recommendations, comparative insights, and a forward-looking discussion of structural reforms, readers are encouraged to consult the Epilogue included in the Appendix B.

8. Conclusions

This article has examined how Afro-Caribbean communities in Canada—specifically first- and second-generation Haitians and Jamaicans—construct and negotiate Blackness through the mobilization of cultural capital within a sociopolitical landscape shaped by polite racism. Drawing on Yosso’s (2005) model of community cultural wealth, the study demonstrated how participants rely on familial, linguistic, social, and navigational capital to access opportunities, resist exclusion, and assert cultural pride. These forms of capital emerge not only through traditional resource exchange but also through culturally specific networks, community support systems, and intergenerational knowledge rooted in legacies of resistance. Despite their resilience and adaptability, these assets are frequently misrecognized or devalued within Canadian institutions governed by white normative frameworks. While Yosso’s (2005) framework remains a useful lens for examining the cultural assets of Afro-Caribbeans, our findings suggest that Canadian-specific racial dynamics necessitate theoretical expansion. “Racial ignominy” captures the affective labour required to manage the subtle shaming of Blackness, while “duplicity of consciousness” addresses the psychic strain of navigating inauthentic spaces under the guise of inclusion.

Polite racism, as theorized in this study, operates both interpersonally—through microaggressions and casual othering—and structurally, via institutional practices that appear neutral but perpetuate racial inequity. This includes the systemic devaluation of linguistic diversity, the erasure of Afro-Caribbean histories in education, and the social shaming enacted through mechanisms such as racial ignominy and duplicity of consciousness. Participants described being subtly questioned about their legitimacy, pressured to code-switch, and subjected to exclusion -illustrating how Blackness in Canada is simultaneously hyper-visible and invisible.

At the same time, participants expressed powerful forms of resistance capital—rooted in collective unity, cultural self-knowledge, and a refusal to conform to racialized expectations. Community festivals, faith-based networks, and intergenerational storytelling functioned not only as strategies of survival but also as acts of affirmation and defiance. These findings suggest that Afro-Caribbean cultural capital must be understood and valued on its own terms—outside of white-centric norms of legitimacy—and recognized as a vital force in shaping identity, belonging, and agency in Canada.

This study makes a dual contribution to both theory and Canadian race scholarship. Empirically, it foregrounds the lived experiences of Haitian and Jamaican Canadians navigating systemic inequities across distinct provincial contexts. Theoretically, it expands the cultural capital framework by introducing three original concepts—polite racism, racial ignominy, and duplicity of consciousness—that capture the uniquely Canadian dynamics of racial misrecognition. Together, these insights offer a distinctly Canadian lens for global conversations on race, identity, and cultural capital—and call for frameworks that better recognize and validate the cultural wealth of diasporic Black communities. These insights compel policymakers and educators to move beyond symbolic inclusion and embrace structurally informed approaches that center the lived cultural wealth of Afro-Caribbean communities.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Ottawa, Office of Research Ethics and Integrity (protocol code S-10-22-8465, approved on 14 October 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting the findings of this study are included within the article. This manuscript is part of the author’s doctoral thesis submitted to the University of Ottawa.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Relational Mapping of Cultural Capital and Racialized Barriers Among Afro-Caribbean Canadians

Figure A1.

Afro-Caribbean Diaspora in Canada.

The entity-relationship diagram (ERD) for the first- and second-generation Afro-Caribbean diaspora in Canada visualizes the social architecture through which community cultural wealth (Yosso 2005) is developed, shared, and mobilized. This model supports the manuscript’s core argument that Afro-Caribbean Canadians—particularly Haitians and Jamaicans—draw upon intergenerational relationships and institutional engagement to construct cultural capital that is often delegitimized through polite racism and systemic exclusion.

Developed using grounded theory-informed coding and thematic analysis, the ERD illustrates key entities in community life—Individuals, Families, Community Groups, Events, and Organizations—and the relational ties that sustain diasporic identity. These connections represent various forms of non-dominant capital, including:

- Familial Capital: Passed through intergenerational ties, especially within extended families. First-generation participants described their reliance on familial narratives, discipline, and spiritual grounding as core survival strategies.

- Social and Navigational Capital: Emerges through participation in community groups and cultural organizations, enabling individuals to build peer networks, gain knowledge of Canadian systems, and resist exclusionary practices.

- Resistant Capital: Reflected in collective advocacy, diasporic activism, and cultural pride sustained through organizations and events.

The diagram also highlights generational differences in how these resources are activated. First-generation participants often lean on familial and navigational capital to overcome institutional barriers, whereas second-generation participants engage more with resistant and linguistic capital in navigating identity within predominantly white educational and professional settings. By mapping these interactions, the ERD reinforces the manuscript’s broader claim: Afro-Caribbean communities in Canada do not passively absorb multicultural ideals. Rather, they strategically negotiate identity and belonging through community-based practices that respond to the duplicity of consciousness and the subtle racial exclusions embedded in Canadian institutions.

Appendix B

Building on the implications outlined in the final section of this study, this Epilogue extends the discussion by offering practical recommendations for fostering authentic inclusivity. It serves as a continuation of the core findings, translating them into actionable strategies rooted in the lived realities of Afro-Caribbean communities in Canada. The research reinforces that while these communities possess significant cultural capital, their contributions are often undervalued due to systemic biases, including polite racism. Addressing these challenges demands intentional, collaborative efforts across policy, education, and community spheres.

Appendix B.1. Recommendations for Policy Reforms

To advance authentic inclusivity, targeted policy interventions are essential. This section outlines several specific recommendations:

- Education Policy Reform:

Integrate Afro-Caribbean history and cultural contributions into the national and provincial curricula. This inclusion will provide students with a more comprehensive understanding of Canadian diversity and challenge prevailing stereotypes. Collaboration between educational institutions, community leaders, and cultural experts can develop robust curricula that reflect the experiences of Afro-Caribbean Canadians, fostering empathy and awareness among students.

- 2.

- Workplace Diversity Initiatives:

Strengthen policies that promote diversity and address subtle forms of exclusion in the workplace. This includes revising hiring practices to recognize diverse linguistic and cultural backgrounds as assets, rather than impediments, and developing training programs that address implicit biases. Employers should collaborate with Afro-Caribbean advocacy groups to create workplace environments that value and integrate cultural capital beyond token representation.

- 3.

- Community-Based Support Programs:

- Funding for Cultural and Social Programs: Increase financial support for community centers and cultural organizations to facilitate mentorship, language preservation, and educational workshops. Successful initiatives, such as the Black Youth Helpline, highlight the benefits of targeted programs.

- Youth Leadership Opportunities: Expand youth engagement through programs that emphasize leadership, community involvement, and cultural pride.

- 4.

- Addressing Systemic Barriers:

Implement policies that specifically target systemic inequalities in housing, healthcare, and employment, which disproportionately affect racialized communities. Data collection and analysis should be leveraged to identify disparities and guide policy changes that reduce the impact of polite racism. These policies should prioritize input from Afro-Caribbean voices to ensure solutions are contextually relevant and impactful.

Appendix B.2. Expanding on Policy Implications

To ensure that this research translates into meaningful change, it is essential to propose actionable strategies for educational institutions and workplaces. Addressing the nuanced forms of “polite racism” requires targeted interventions that promote cultural competency and inclusive practices. Schools and universities should incorporate curricula that reflect the diverse histories and contributions of Afro-Caribbean communities, emphasizing cultural assets beyond stereotypical representations. Training programs focused on recognizing and mitigating microaggressions, and polite racism should be mandatory for educators and administrators. In workplaces, policies that encourage diversity should go beyond recruitment, fostering an environment where Afro-Caribbean employees can express their cultural identities without fear of subtle biases. Leadership workshops and mentorship programs tailored to the unique challenges faced by racialized employees could help dismantle the implicit biases embedded in corporate culture.

Appendix B.3. Comparative Insights

Drawing parallels between the experiences of Afro-Caribbean communities in Canada and similar groups in other multicultural societies provides valuable context and reveals common challenges. For instance, examining the socio-cultural integration of Afro-Caribbeans in the UK or Afro-Latinx groups in the United States can offer insights into shared struggles, such as navigating racialized perceptions while mobilizing community cultural capital. These comparative studies highlight global patterns of subtle discrimination, allowing for the identification of best practices that can be adapted to Canadian contexts. Understanding how policies and community initiatives in different regions have succeeded or failed in addressing racialized barriers can inform more robust, context-sensitive approaches to fostering inclusivity and equity in Canada.

Appendix B.4. Towards a More Inclusive Future

The call for authentic inclusivity must go beyond surface-level diversity initiatives to embrace the inherent value and contributions of Afro-Caribbean communities. Acknowledging the challenges, such as resistance to policy changes and the need for comprehensive strategies, will be essential for sustainable progress. Policymakers, educators, and social institutions must work collaboratively with these communities to create frameworks that respect and promote cultural capital as a dynamic, positive force.

Appendix B.5. Overcoming Potential Challenges

Implementing these recommendations may encounter resistance due to entrenched systemic norms and biases. It is crucial to anticipate and address such challenges through transparent communication, continuous training, and community-led initiatives. Engaging stakeholders at all levels—government, private sector, and grassroots organizations—will help align efforts and mitigate pushback, fostering an environment where changes can be embedded effectively over time.

References

- Abrar-ul-Hassan, Syed. 2021. Linguistic capital in the university and the hegemony of English: Medieval origins and future directions. SAGE Open 11: 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbour, Rosaline S. 2007. Doing Focus Groups. London: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, Tony, Mike Savage, Elizabeth Silva, Alan Warde, Modesto Gayo-Cal, and David Wright. 2009. Culture, Class, Distinction. London: Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Bilecen, Banu, Inga Diekmann, and Thomas Faist. 2023. Loneliness among Chinese international and local students in Germany: The role of student status, gender, and emotional support. European Journal of Higher Education 14: 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonilla-Silva, Eduardo. 2006. Racism without Racists: Color-Blind Racism and the Persistence of Racial Inequality in the United States, 2nd ed. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Bouchard, Gérard, and Charles Taylor. 2008. Building the Future: A Time for Reconciliation (Report of the Consultation Commission on Accommodation Practices Related to Cultural Differences). Québec: Government of Québec. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1977. Outline of a Theory of Practice. Translated by Richard Nice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1986. The forms of capital. In Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education. Edited by John G. Richardson. New York: Greenwood Press, pp. 241–58. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, Pierre, and Jean-Claude Passeron. 1990. Reproduction in Education, Society and Culture, 2nd ed. London: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, Pierre, and Loïc Wacquant. 2013. Symbolic Capital and Social Classes. Journal of Classical Sociology 13: 292–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, Malcolm, and John Loonam. 2010. Exploring the use of entity-relationship diagramming as a technique to support grounded theory inquiry. Qualitative Research in Organizations and Management: An International Journal 5: 224–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, Dionne. 2001. A Map to the Door of No Return: Notes to Belonging. Toronto: Doubleday Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, Prudence L. 2005. Keepin’ It Real: School Success Beyond Black and White. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Coen-Sanchez, Karen. 2021. Systematically disenfranchised: Addressing anti-Black racism cannot happen without teaching about white privilege. The Sociological Review, September 7. Available online: https://thesociologicalreview.org/magazine/september-2021/new-solidarities/systematically-disenfranchised/ (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- Coen-Sanchez, Karen. 2025. Navigating identity and policy: The Afro-Caribbean experience in Canada. Social Sciences 14: 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]