Abstract

Social work with families has developed in response to the needs of people in the community but has moved away from them over the years of specialisation. The neoliberalisation of social work, with its emphasis on efficiency and procedure, has eclipsed the processes of collaboration with people, which are a prerequisite for hearing their voices and establishing a partnership in which we can co-create desired outcomes. In Slovenia, over the last 10 years, we have been looking for ways to bring social work with families in complex problem situations back into the community and to prioritise the processes of co-creating the desired outcomes in national and international projects. The most important milestones of the development, identified by the thematic analysis of the project documentation (58 documents) of seven projects, are presented here. Several themes were interwoven in the development and implementation of change: knowledge development; relevance of the institutional context; (micro-)innovation in social care; development of projects with practitioners and family representatives; broader social context centred on family support. Ten years of development in the field confirms that complex questions require complex answers, which must be (co-)created in collaboration between families, practitioners, policymakers and researchers.

1. Introduction

Over the past ten years, national and international projects in Slovenia have been intensively searching for ways to further develop social work with families in complex problem situations in order to respond to the needs of families in the best possible way through knowledge and practice. Families who find themselves in these complex problem situations face a variety of complex, often intertwined problem situations, such as poverty, unemployment, health problems, educational powerlessness, children’s learning difficulties, domestic violence, addiction, etc. Often, many professionals are involved in solving a family’s complex problems, but they are not connected, so the family does not receive the help it really needs (e.g., Walsh 2006; Melo and Alarcão 2013; Madsen 2014; Mešl and Kodele 2016).

After ten years of development, we want to analyse the steps taken to understand what has helped development, what has hindered it and what we need to do in the future to integrate the best practices developed in individual projects into everyday social work practice.

Based on the data collected during decade-long research and development work, we aim to identify what the key development milestones are (have been) in developing knowledge for working with families in complex problem situations; how they have contributed to understanding the needs of families; and what forms of support and systemic changes are needed to adequately support families in social work.

We approached the changes gradually, unaware that the initial steps would, in the following years of development, be built upon to explore ways of (re)shaping social welfare systems to support collaborative work with families at a systemic level. In retrospect, we understand that we entered into a great complexity in at least two areas: in the field of help and support to families in complex problem situations tied to understanding the lifeworld of families and developing knowledge on appropriate support processes; and in the field of implementation of the developed knowledge within existing social welfare systems.

In this article, we present a collaboration spanning over ten years with different participants, who have broadened our perspectives from project to project on the development of the field and the necessity of complex social work responses that need to be co-created by researchers, practitioners, policymakers and service users, i.e., family members. The development of the field concerns the whole country, as Slovenia is a small state with only one faculty of social work. When we carry out national and international projects, we involve stakeholders from all over the state. We have been the only social work organisation in the country to develop the field of collaborative social work with families, to which the seven projects we have implemented over the years have made an important contribution. We have analysed project documentation from seven research projects to develop our understanding of the changes needed in knowledge, practice and institutional context for social workers to co-create desired outcomes with families in the community.1

We are interested in identifying what is required to implement the good practice of working with families in projects into everyday practice at the systemic level. Years of working in the field of social work with families, supported by findings from other researchers (e.g., Lynch et al. 2018; Engle et al. 2021), have confirmed that even compelling evidence that something works in practice is not enough to change practice on a daily basis and to improve the quality and effectiveness of services.

1.1. Families in Complex Problem Situations and the (in)Adequacy of Processes of Help and Support

Through research and collaboration with families in complex problem situations, labelled by different authors as, e.g., multi-problem families (Matos and Sousa 2004; Bodden and Deković 2016), vulnerable families (Sharlin and Shamai 2000), families facing multiple challenges (Melo and Alarcão 2013; Mešl and Kodele 2016), stresses (Madsen 2007) and problems (Walsh 2006), etc., we quickly realised that despite the different labels, these families struggle with similar family realities. These families face problems and challenges which are multiple, chronic, complex, transgenerational, entangled and affect various areas of their lives (Bodden and Deković 2016). They live in poverty and are confronted on a daily basis by internal and external stressors. They face circumstances that contribute to multiple crises. It is precisely because of these challenging circumstances in which families live, that we ourselves have begun to use new terminology in recent years to emphasise the diverse problem situations of families (according to Tausendfreund et al. 2015). These families struggle to adapt to a harsh environment that offers them unfavourable resources. This leads to an overburden and destabilisation of the families. They often lack opportunities and the necessary time and support to learn, develop and strengthen their skills and knowledge (Sharlin and Shamai 2000; Melo and Alarcão 2013; Madsen 2014). The narratives of these families are all too often dominant family narratives of failure that are passed down from generation to generation (Madsen 2007).

In social work, we assume that the language of social work is positive and respectful, and protects the uniqueness and dignity of the human being. It does not judge, stigmatise, condemn, lecture or devalue (Čačinovič Vogrinčič 2016). For this reason, we have been working for many years on the question of which term is best suited to families who face numerous, complex psychosocial difficulties and problems in their everyday lives. At the beginning of the projects presented in this article, we used the term “families with multiple challenges” (which is why the old term is still used in the project titles), but we have found that this is not the most appropriate term, as it tends to devalue the severity of the difficulties and problems faced by the families. Only in the last two projects have we switched to using the term “families in complex problem situations”, mainly because it emphasises that not all of the responsibility for a family’s hardships and difficulties can be attributed to the family alone, but that these are often also systemic and caused by systemic factors. In the future, our intention is to discuss this topic with families and work with them to develop an appropriate term. In social work, it is important to develop and use the language of the profession together with the people who come to us for support and help (Čačinovič Vogrinčič 2016).

Families in complex problem situations often receive a lot of specialised help. This involves help from different professionals who usually only work with the families in one specific area and the help is fragmented (Matos and Sousa 2004; Walsh 2006; Madsen 2007; Melo and Alarcão 2013). Thus, a family may be overloaded with different types of help, but the desired changes do not materialise because each professional worker is mainly focused on solving one part of the problem. Often, the help remains unsuccessful because it is mainly provided in instrumental areas (finances, food, medication, etc.) but does not target family relationships (Matos and Sousa 2004). The authors emphasise (Ibid.) that interventions focusing on this issue would be expected as families in complex problem situations struggle with issues such as instability, chaotic interactions, lack of rules, poor parenting skills, etc. It is unacceptable that despite the involvement of numerous professionals, families are left without the help they really need.

Through the projects of the last ten years, we have tried to respond to inadequate forms of support for families in complex problem situations. We have aimed to develop ways of providing support that would overcome the fragmentation of support and the overburdening of families, which does not lead to desired change. Most importantly, we wanted to support students and social workers to consistently apply contemporary concepts of social work with families in practice. One of the most important concepts we have developed in social work in Slovenia is the concept of the working relationship of co-creation (Čačinovič Vogrinčič and Mešl 2019). It is a new way of engaging as social workers with people who need support and help, enabling them to explore and co-create help. The concept of co-creation defines both the relationship and the process of helping. The relationship between users and social workers is the relationship between experts with experience and an appreciative and accountable ally (Madsen 2007), who establishes and protects the processes of exploration and participation in the desired outcomes. The focus is on the process, on each participant’s contribution to defining problems and finding solutions (Čačinovič Vogrinčič and Mešl 2019).

1.2. Challenges of Implementing Developed Knowledge in Existing Social Welfare Systems

With the intensive development of knowledge in the field of social work with families in complex problem situations and good results related to the desired changes in the families, supported in the projects (see e.g., Mešl 2018), we soon realised that new challenges were ahead. The initial expectations that the developed knowledge, supported by evidence from practice, would be sufficient to create pathways for existing family support systems to gradually start using this knowledge and for systemic change to happen organically did not materialise.

While it may sometimes seem that it is enough to care for and develop the area where we work and feel most competent (e.g., practitioners conducting excellent practice, researchers conducting research, politicians designing social policies, etc.), we need to look for ways to integrate all levels so that we can contribute to holistic development for the best outcomes for families. If we only link research and policies, we will not reach people directly. Linking research and practice brings individual gains for people, but without the necessary systemic changes. Linking policy and practice without research can be harmful if practice is not based on research findings. Linking research, policy and practice can benefit people most (Canavan et al. 2016; Churchill et al. 2024; Devaney et al. 2022). Social work practice needs to be informed by research and set within clear frameworks of relevant policies.

At the same time, it is important to plan change carefully, because we now know that new evidence of good practice alone is not enough. Implementing change is a complex process that involves the “new evidence” to be implemented, the “context” where the evidence will be introduced, the “agents or actors” who will use or apply the new evidence and the “mechanisms” or processes that actually bring about the changes (Lynch et al. 2018; Weiner et al. 2020).

However, the introduction of change in organisations is also linked to organisational readiness for change, which refers to the extent to which the target employees (in particular, practitioners) are psychologically and behaviourally prepared to make the changes in organisational policies and practices that are necessary to put the innovation into practice and to support the use of the innovation (Weiner et al. 2009).

1.3. Context of Social Work (with Families) in Slovenia

In the 1970s and 1980s, social work played an active role in Slovenian society. At that time, social workers dealt with relevant social issues and promoted new, action-orientated approaches and forms of work with people (social community work, social action, participation in social movements). However, from the 1990s onwards, a gradual decline in socially engaged social work could be observed, which can be seen in the context of the global paradigm shift towards neoliberalisation and individualisation of responsibilities, indicating a gradual depoliticisation of social work (Jordan 2001; Reisch and Jani 2012; Mattocks 2018). Slovenia, like other parts of the world (Ferguson 2004; Mongkol 2011; Spolander et al. 2014; Hyslop 2018; Zilberstein 2021), has uncritically adopted the neoliberal mentality, which led to the introduction of New Public Management (NPM) into the functioning of social care services. NPM was introduced in Slovenia in 2018 when the Social Work Centres (SWCs), the main public providers of social services (including for families in complex problem situations) established and founded by the state, were restructured. The main objectives of the reform were rationalisation, financial efficiency and control over the performance of social workers. In 2018, there were sixty-two independent SWCs in the country. The reorganisation created a pyramid structure, resulting in sixteen regional centres with additional units, making a total of sixty-three. Each regional SWC is headed by a director, and each regional unit has an assistant director. There is not much difference in terms of numbers, but there is a significant difference in terms of independence and hierarchy, as only sixteen SWCs are now considered legal entities. This also means less professional autonomy, more control over staff and service users and complicated, costly computerisation and recording of staff performance. The volume of work is increasing while staff are decreasing2; Harris (2003) would call this “the business of social work” and Ferguson (2004) “the managerialist approach”. SWC staff are civil servants, who are expected to go along with these changes and take on a gatekeeping or supervisory role, even assuming a role as soft police officers (Baines 2022). They have little power in shaping their own work lives and therefore find it difficult to empower their users (Cree 2013). In such a social climate, the emphasis on social justice and social action is weakening and being replaced by individualism and therapeutic interventions (Mattocks 2018). These processes can also be seen within social work in Slovenia.

The question therefore arises as to whether the SWC institutional framework offers opportunities for the implementation of contemporary social work knowledge and whether co-creation with users is even possible under neoliberalism. Since the establishment of the first SWC in the early 1960s, these institutions have undergone several reforms, including the specialisation of work, a number of regulations and extensive changes in legislation, where the notion of the controlling role of the state has been established (Rihter 2011), work overload, etc. This does not apply only in Slovenia; e.g., Parton and O’Byrne (2000), Munro (2011) and Madsen (2014) also express concern that social work has become overly procedural.

The institutional context, which raises legal and procedural issues, has contributed to dissatisfaction among users, professionals and the public in Slovenia. Fragmentation of services is also a problem: fragmentation encourages inconsistent and unreliable services, the development of superficial relationships with users and the loss of belonging and fragmented identities of social workers (Carey 2015).

2. Materials and Methods

The many good experiences in the individual projects we have carried out over the past ten years—the development of knowledge to help families in complex problem situations, the satisfaction of the families helped, the satisfaction of the professionals involved in the projects, the enthusiasm of the policymakers to whom we presented the results, etc.—have contributed to the motivation of the researchers to continue our research and development work in this field year after year. A look back over the past decade reflects many good practices and satisfaction with small yet significant progress. However, it also raises questions about whether we have done enough and what barriers are preventing these good practices from becoming an integral part of daily work with families at SWCs. All this led to the formulation of the objectives of the present study, which sought to answer the following research questions through a systematic analysis of past work:

- What (qualitative) developments in content have taken place over the ten years of research and project work in the field of social work with families in complex problem situations?

- How has each development contributed to the understanding of the needs of families and the development of social work with families?

- What is needed to implement the good practices of support and help for families in complex problem situations developed in the project into daily practice?

The findings are based on an analysis of the secondary material of the project documentation of seven international and national research projects that we have developed over the last ten years in the field of social work with families in Slovenia. We conducted a thematic analysis (Vaismoradi et al. 2013; Naeem et al. 2023). First, we reviewed the collected project documentation of seven projects in the field of social work with families from 2013 to 2024 and selected relevant documents for the analysis. We selected 58 documents (see Table 1). We then read the selected documents in their entirety and extracted the relevant parts of the text according to the research problem defined. We assigned codes to the selected relevant text passages. We grouped codes with a common meaning to define themes. We then went through the documentation again, project by project, and marked which codes were relevant to each project (see Table 2).

Table 1.

Information on projects and project documents included in the analysis.

Table 2.

Qualitative analysis of project documentation.

3. Results

Table 1 shows data on individual projects, so we do not present the projects in more detail below, as the results focus on the findings of the thematic analysis. With the start of project development, the focus has been on developing knowledge and narrowing the gap between theory and practice. The objectives were broadened from project to project (see Table 2), linked to the findings of previous projects and to the involvement of practitioners in projects that addressed issues related to the (in)appropriateness of institutional contexts. As collaboration has grown, so has awareness of the complexity of implementing innovation at the level of the whole organisation.

3.1. Bridging the Gap Between Theory and Practice and Developing New Knowledge

The objectives of the initial projects, which were developed with the aim of improving support for families in complex problem situations, were mainly aimed at reducing the (unfortunately still) existing gap between the theory and practice of social work with families and developing new knowledge to support families in the best possible way. This remained a central concern throughout the follow-up projects, while the objectives and activities of the projects were broadened (see Table 2).

Through collaboration with Master’s students and practitioners in small mentoring groups, we contributed to the development of the field with the following:

- -

- Testing the applicability of family social work concepts in practice: Students and practitioners were repeatedly invited to consistently apply contemporary family social work concepts in concrete practical situations with families. This was possible with intensive mentoring support in small mentoring groups with trained mentors who were researchers and teachers at the faculty. Having direct experience that the application of knowledge contributes to competent practice and to co-creating desired outcomes with families contributed to narrowing the gap between theory and practice, especially for students, which sometimes widens when they receive the message and experience on placement that theory cannot be applied in practice (see also Mešl and Kodele 2016; Kodele and Mešl 2024). By involving practitioners in projects, it became apparent that, in order to apply contemporary social work concepts, it was necessary to provide the appropriate institutional conditions to enable the knowledge developed to be applied in practice.

- -

- A reflective approach to learning: The intensive mentoring support in small groups with trained mentors was based on the reflective application of knowledge (see also Kodele and Mešl 2024), the continuous integration of theory and practical experience and the development of new skills on this basis. Reflective learning was also supported by the note-taking forms developed within the project, which were designed to reflect on practical action and knowledge acquired.

- -

- Developing knowledge to work with families in complex problem situations: Based on testing the applicability of the concepts in practice, a reflective approach to learning, interviews with families, focus groups with students and analysis of the collected forms for recording work processes, we have developed new understandings of the lifeworld of families and a model for helping families complex problem situations in the community (see e.g., Mešl and Kodele 2016).

- -

- Developing the skills to work with families in complex problem situations—interdisciplinary: Analysis of the project documentation shows the importance of the incorporation of interdisciplinary perspective for the development of the field (e.g., small mentoring groups with professionals from other fields (psychology, pedagogy, etc.) and the establishment of an interdisciplinary intervision group in the local community). This can provide new perspectives and jointly developed knowledge to support families.

Although in the first pilot, we already made a significant shift in understanding the needs of families and developed ways of working with families that contributed to progress towards the desired outcomes (see e.g., Mešl 2018), even today, after more than a decade of developing the work, we have not yet achieved the desired shifts in day-to-day practice. New projects have broadened our focus on understanding the different levels of action that co-shape the possibilities for implementing good practices in existing systems.

3.2. Understanding the Importance of the Institutional Context and Action at the Systemic Level

The analysis shows that institutional conditions have a significant impact on the possibility of applying contemporary concepts of social work with families in daily practice. This became apparent by involving practitioners in the project, whose feedback on the (in)applicability of contemporary concepts was often related to the institutional context of their work.

The importance of relevance of the institutional context for the work has emerged as an important aspect of developing support for families in complex problem situations. When the knowledge developed was tested in daily practice by social workers from SWCs, it was found that in the cases they had selected for project work, and where their involvement protected their ability to put contemporary concepts into practice (time to work, support in a small mentoring group, etc.), they were able to apply the knowledge developed and thus contribute to good family outcomes. The problem was their daily practice, in which they were overwhelmed by the number of cases, the different tasks, the demands placed on them by the procedural orientation of the SWC (entering data into different databases, writing reports, administrative procedures, etc.).

The challenge for a wider application of the knowledge developed in the practice of SWC remained linked to the constraints of the existing institutional context. A significant shift took place, when together with the director of one of the SWCs and the heads of the individual units of the centre, in intensive collaboration with practitioners, we started to develop new institutional frameworks that would allow for a more in-depth collaboration with families. Over the course of the three-year collaboration, it became clear which institutional changes were necessary in the area of work with families in complex problem situations: work with families in the community, a norm of up to 10 families living in complex problem situations for the full-time employment of a professional worker, a change in national legislation towards the definition of a new service (e.g., early support for families in the community) or the redefinition of an existing family support service for the home setting that would define the service in terms of the findings developed within projects (proactive collaborative social work with the families in the community, specific norm for this group of families). Similar conclusions about the need to change the institutional framework in SWCs were drawn in a project that was run concurrently at another SWC. The findings of the analysis of the records of the professional worker’s tasks revealed a low proportion of direct work with families, as the professional workers spend more time on other tasks (note-taking, meetings related to work in several areas at the same time, etc.).

An important lesson we learned from participating in projects with SWCs is to be prudent, gradual, flexible and patient when introducing change in the overall institutional context of a given organisation (see also Weiner et al. 2020). A new theme emerged, which meant broadening our focus: ways to introduce change in the SWC institutional context. Several years of gradual development of knowledge in the field, promotion of projects and positive results of collaboration with families have led to gradual initiatives from certain SWCs to implement the developed knowledge in daily practice. The enthusiasm and commitment of the directors and some of the practitioners to co-create change in daily practice with the staff did not, however, translate into a general enthusiasm on the part of the practitioners. In terms of how to implement change in the SWC institutional context, we have learnt that it is necessary to check the decisions to participate in projects and the motivation of individual participants, and to plan and implement the change with the practitioners involved in a co-creative manner, which is how we want to collaborate with the families. Changes in such an organisation take time to be implemented. It makes sense to start where professional workers are willing to cooperate, reflect on obstacles, explore new possibilities together and gradually create space for new project participants who are attracted by small positive shifts within the team. In this process, the support and commitment of leadership is crucial.

3.3. (Micro-)Innovation in Social Care

In recent years, innovation has also been increasingly used in the context of social activities related to society and psychosocial challenges. Social innovation aims to influence and solve social and societal problems at different levels, finding ways to respond to needs and consequently improving the situation of the target groups for which the innovation is intended. The institutional context, which often prevented us from being able to consistently apply contemporary concepts of social work with families in the social care system, in turn, led us to start thinking about what we can do to improve existing practices. Thus, within the framework of the analysed projects, practitioners in the field of social care started to develop micro-innovations.

One set of micro-innovations was carried out at the individual level, where professional workers selected families with whom they worked continuously, consistently and consciously applied contemporary concepts of social work with families. In doing so, each of them developed at least one micro-innovation to find solutions for adequate support for the families in the given institutional context (e.g., increased accessibility of the social worker in communication via personal emergency phone, mother and child living together in a foster family, greater focus on the social work doctrine and consistent application of knowledge in practice, moving away from a position of power, co-creation of support plans, intensive work with families at home and in the community, collaboration with all the institutions involved, etc.).

The second set of micro-innovations took place at the organisational level. The introduction of a mobile service for early family support at the SWC and the establishment of a learning and innovation lab in the local environment represented a major innovation in the organisation of work at the SWC. Within this framework, we wanted to contribute to the further development of direct, relationship-based social work with families in the community and to support the development of more integrated and family-centred services through innovation. This is not to ignore the fact that both micro-innovations and innovations in the organisation of work have been made possible (in particular) by the commitment of SWC managers, who have sought to ensure that families can receive the best possible support in the existing SWC institutional context.

3.4. Developing the Project with Practitioners and Family Representatives

During the course of the projects, we have also started to think more and more intensively about how to involve practitioners, who work with families in complex problem situations in their daily practice, as well as families, more actively in the development of the project itself. As previously written, when practitioners were involved as participants for the first time, they broadened our understanding of the changes needed to develop practices based on contemporary collaborative social work concepts. In order to apply these concepts more consistently in practice, appropriate institutional conditions need to be provided. Important milestones were achieved through the involvement of practitioners in the development of the project. Using the example of two projects, in the sixth project, practitioners were actively involved in the project planning. The director, together with practitioners, developed an idea of how she wanted to strengthen early support and help to families in a complex problem situations at the SWC. Their idea was based on what had been developed in previous projects at the Faculty of Social Work (support for families in the community, intensive support for practitioners in small mentoring groups with the aim of reflexive application of knowledge and continuous integration of theory and practical experience). They recognised the key insights and knowledge developed in previous projects as an important contribution to improving the practice of practitioners and to the development of quality services for families. Researchers of Faculty of Social Work thus helped SWC practitioners to implement their ideas by leading mentoring groups and reflecting with them on how to strengthen early support and help to families. Similar to various research studies (Munro 2011; Featherstone et al. 2014; Mešl and Kodele 2016), the experience of the project has shown that support for families, especially those with complex problems, is often focused on firefighting rather than prevention work.

The concept of a working relationship of co-creation (Čačinovič Vogrinčič and Mešl 2019) was also carried over into the work planning itself in the seventh project, thus taking a step forward in terms of involving practitioners in the development of the project itself. Our fundamental objective was to develop a so-called learning and innovation lab to be set up in each of the countries participating in the project. The labs were to be formed in such a way that they would be as much as possible based on the needs of practitioners and users. Therefore, in the initial part of the project, researchers of Faculty of Social Work and SWC practitioners held several one-day meetings and used different working methods (e.g., focus groups to review the situation, World Cafe Method, Consensus Building Activity) to shape the activities we want to develop in the project. In this way, we followed the principles of participatory research, which aims to use the research process as a vehicle for change and empowerment of research participants, better reflecting the voice of the service user and using it to influence policy and practice (Involve 2012). By involving practitioners, we were able to design activities that were meaningful to the practitioners and most responsive to their current needs (e.g., recording the time and tasks dedicated to working with families at the SWC, conducting research with families about their experiences of collaborating with the SWC, establishing an intervision group.)

We believe that we were successful in involving practitioners in the development of the project, as evidenced by the analysis of the documentation of these two projects. Practitioners were increasingly willing to participate in the shaping of certain activities and their intrinsic motivation to participate in the project increased.

As social work is a profession and a science that advocates for the involvement of service users not only in the processes of support and help, but also in the shaping of services in order to best respond to their needs, the question of how to involve families more actively in the process of project development has been a recurring one since the beginning of the implementation of the projects. After all, the fundamental aim of all the projects has been to support families in achieving the desired changes and to offer them the highest quality services. The analysis of the documentation shows that, in two projects, we have taken the first steps towards involving families in the co-design of services: through in-depth interviews and meetings with service users within the learning and innovation lab (LAB) and through the inclusion of children’s representatives in the national working group for the preparation of the National Report on family support in Slovenia, alongside practitioners and experts.

These were two steps in the desired direction, but there are further challenges. For example, the minutes of the LAB meetings show that the practitioners involved in the LAB are not yet comfortable with having representatives of the families they work with in practice present at the meetings when researchers and practitioners are planning the activities of the LAB.

3.5. Conceptualising Family Support

The analysis of the project documentation has also shown the importance of an integrated approach to the development of a European conceptual framework for family support (at international and national level). In this context, several objectives were pursued: the creation of a pan-European family support network that brings together policymakers, children and families, public and private organisations and society at large to pursue the overarching goal of ensuring the rights of the child and the well-being of families; a comprehensive national-level analysis of family support policy and practice across Europe; comprehensive catalogue of an agreed standardisation framework on family support workforce skills. In order to move towards the adoption of high-quality family support, it is necessary to ensure the adoption of agreed quality standards for professional practice in family support in Europe. The results obtained in the context of this wider European network confirmed the findings of previously conducted projects at the national and international level, such as the necessity for cooperation between different agents in the field of family support, the challenges posed by a poorly developed family support evidence system, the difficulty to achieve change in daily practice if the institutional context (workload, focus on procedural tasks) does not support in-depth work with families, the importance of supporting students in the transfer and application of theoretical knowledge in practice and the need for continuous and reflective training of professionals working in the field of family support (Kodele and Mešl 2024).

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations of the Study

The research carried out has some limitations. Firstly, the two researchers who carried out the analysis were also active members of the project team or even project leaders of the projects we analysed. On the one hand, this means that they may have more knowledge and a broader understanding of certain topics presented in the paper, but on the other hand, their active involvement in the project may give them a different perspective on certain topics than if the analysis had been carried out by someone who was not involved in the project. Secondly, it was also a challenge for the researchers to decide which project documents to include in the analysis, as there was a lot of material. In the end, they decided to include in the analysis documents where the objectives of the projects were evident and where it was possible to identify certain substantive shifts and changes in the project. Thirdly, the documents included in the analysis for the present study are secondary materials, primarily collected for the purpose of the individual projects. It would have been interesting to include direct empirical material (e.g., interviews with families, focus groups with the researchers, with members of the stakeholder forums after a few years of participation in the project, etc.), but this is beyond the scope of the present paper. Despite these limitations, we believe that the thematic analysis of the project documentation of the seven projects aimed at improving support to families has highlighted important aspects that need to be taken into account when implementing projects, and in particular, the complexity of implementing change.

4.2. We Need to Create Complex Answers to Complex Questions

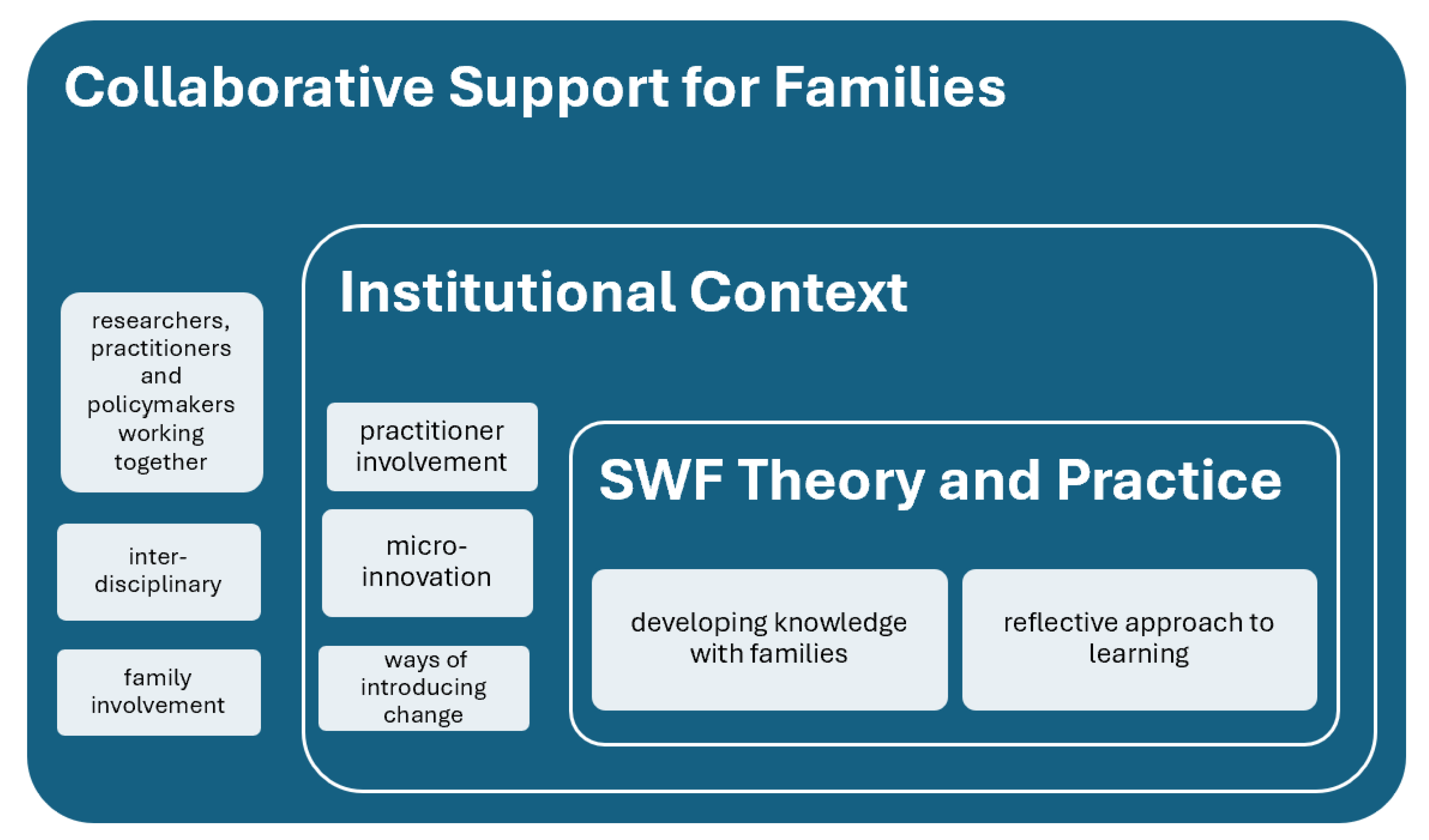

The analysis of the documentation of all the projects, which has helped us to develop our understanding of the complexity of the changes needed in the field of social work in Slovenia, has also contributed to our understanding of the interconnectedness of the themes (Figure 1). All the themes interact to form a complex interplay of several levels of action that should not be overlooked when we want to introduce changes in social work practice with the families in order to improve support and help.

Figure 1.

The complexity of implementing change to support families in complex problem situations—relational coding.

The development of theory and practice in the field of social work with families in complex problem situations is a necessary starting point for the provision of appropriate processes of support and help to families. Certainly, the initial knowledge development in the first projects was crucial to better understand the lifeworld and needs of families in complex problem situations and to develop a model of collaborative social work with families in the community (see Mešl and Kodele 2016). In order to develop the knowledge to support families, it was essential to work with families as experts on experiences, thus respecting their valuable competencies (Čačinovič Vogrinčič and Mešl 2019). Supporting the application of knowledge in practice, based on a reflexive approach to learning, was also key to linking theory and practice (see Mešl and Kodele 2016; Kodele and Mešl 2024). Evidence-based knowledge developed within projects is not sufficient to implement change in everyday practice, to make change systemic. This requires appropriate institutional contexts that support opportunities to work differently (Healy 2005). In part, social innovations can be developed within existing institutional contexts that contribute to creative responses to given challenges, but for larger systemic change, the institutional context also needs to be adapted. However, it is important to emphasise that neoliberalism (increasing inequalities, bureaucratisation, standardisation of services, individualisation of problems, erosion of social rights, etc.) has also had a significant impact on the institutional context itself. For social workers, it is also crucial to be critically engaged and in touch with senior management to discuss the organisational or procedural improvements necessary to provide quality services for everyone (Trappenburg et al. 2020).

The necessary changes in institutional contexts can best be understood in collaboration with practitioners. In doing so, all involved need to plan well how we will create the right conditions for change to take place at the organisational level. As Weiner et al. (2009) also point out, the introduction of complex innovations typically involves many interrelated changes in organisational structures and activities. Organisational readiness for such change is reflected in the level of commitment to change and the effectiveness of change. Collective determination is important, as the implementation of complex innovations involves the joint action of many people, each contributing something to the implementation effort. The importance of the leadership of individual organisations in implementing change cannot be overlooked either. Some claim that half of all implementation failures occur because organisational leaders do not sufficiently prepare organisational members for change (Kotter 1996). Thoughtful consideration and responsiveness are required to the specific circumstances tied to the change being implemented, the methods and people involved in its implementation and the environment in which it is to be implemented (Lynch et al. 2018).

The aim of all projects was to provide collaborative support to families. Today, after ten years of developing the field, we understand that this requires collaboration at the level of practice, research and social policy (see also Canavan et al. 2016; Churchill et al. 2024; Devaney et al. 2022). Integrated support requires interdisciplinary collaboration, in which it is essential to involve families. The analysis of the project documentation shows that the direct involvement of families (i.e., that families also participate as active collaborators in the planning, implementation and evaluation of project activities) only partially started in the fifth and seventh projects. We will need to pay even more attention to the latter in the future because, as various authors point out (see e.g., Beresford 2005; McLaughlin 2012; Panciroli and Corradini 2019), user involvement in research can contribute to increasing researchers’ awareness of users’ challenges and needs, as well as to improving services for them.

Another important factor for the development of the field of social work with families in complex problem situations is the European social policy context, which supports the development of Family Support as a broader framework for the field of support for families in complex problem situations in a number of documents that are important starting points for the development of social policies (e.g., the Council of Europe recommendation on policy to support positive parenting; on children’s rights and social services friendly to children and families; the Council of the European Union on establishing a European Child Guarantee). In the future, we must base our discussions with social policymakers in Slovenia even more on these documents, which explicitly support our efforts to develop family support.

In the course of our projects, we have found that integrating research, practice and policy can be quite a challenge. The analysis shows that we have made progress towards integrating research and practice, but not enough at the policy level. As a result, this means that changes associated with the systemic (macro) level were not implemented on a wider scale after the project was completed.

Finally, we would like to emphasise that while we focus on developing processes to support and help families in complex problem situations, we also want to point out that in social work, it is not enough to work at the micro level, i.e., to support and help families directly. If we really want to support families to achieve the desired changes, it is also necessary to bring about social change to ensure the conditions for a decent life for every person and every family. Gupta et al. (2018) write about “the politics of recognition and respect” that prioritises the voices, participation and life experiences of those living in complex problem situations, broadening the focus of social work from the relational to the political level. This is clearly a necessary direction for the development of social work with families in complex problem situations.

Author Contributions

Authors contributed equally to this work. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SWC | Social Work Centre |

| NPM | New Public Management |

| LAB | Learning and Innovation Lab |

Notes

| 1 | Supporting families within the community, as conceived in our projects, means working with families in their own homes, where they live, and sometimes, if it is not possible to work at home for various reasons, or the family expresses a desire to work outside the home, in another place in the family’s community, such as a library or park. Support within the community also means collaborating with the community and connecting important sources of support for the family (Mešl and Kodele 2016). |

| 2 | SWCs are staffed by a variety of profiles, mainly social workers, psychologists and lawyers. According to available data from the Ministry of Labour, Family, Social Affairs and Equal Opportunities, the number of SWC employees has been decreasing from 2013 to 2016. While the number of SWC staff has been increasing over the last three years, which is linked to the additional tasks SWCs have taken on, the family support services sector is still struggling with an understaffed workforce in relation to the number of families in need of help. |

| 3 | Families were directly or indirectly involved in all projects. It is difficult to ascertain the number of families involved as in some projects, professional workers implemented the changes in their daily practice and we do not know the exact number of families affected by the project activities. |

| 4 | The number in brackets indicates how many documents were included if more than one. |

| 5 | The group consisted of researchers, professional workers from the field of family support, social policymakers and two child advocates. They were all involved in the project as researchers and contributed to the development of the documents produced as part of the project. |

References

- Baines, Donna. 2022. Soft Cops or Social Justice Activists: Social Work’s Relationship to the state in the context of BLM and Neoliberalism. The British Journal of Social Work 52: 2984–3002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beresford, Peter. 2005. Developing the Theoretical Basis for Service User/Survivor-led Research and Equal Involvement in Research. Epidemiologia e Psichiatria Sociale 14: 4–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bodden, Denise H. M., and Maja Deković. 2016. Multiproblem Families Referred to Youth Mental Health: What’s in a Name? Family Process 55: 31–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canavan, John, John Pinkerton, and Pat Dolan. 2016. Understanding Family Support: Policy, Practice and Theory. London and Philadelphia: Jessica Kingsley Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Carey, Malcolm. 2015. The Fragmentation of Social Work and Social Care: Some Ramifications and a Critique. The British Journal of Social Work 45: 2406–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čačinovič Vogrinčič, Gabi. 2016. Social work with families: The theory and practice of co-creating processes of support and help. In Co-Creating Processes of Help: Collaboration with Families in the Community. Edited by Nina Mešl and Tadeja Kodele. Ljubljana: Faculty of Social Work, University of Ljubljana, pp. 19–41. [Google Scholar]

- Čačinovič Vogrinčič, Gabi, and Nina Mešl. 2019. Socialno delo z družino. Soustvarjanje želenih izidov in družinske razvidnosti [Social work with the families. Co-creation of desired outcomes and family transparency]. Ljubljana: Fakulteta za socialno delo. [Faculty of social work]. [Google Scholar]

- Churchill, Harriet, Devaney Carmel, and Angela Abela. 2024. Promoting child welfare and supporting families in Europe: Multi-dimensional conceptual and developmental frameworks for national family support systems. Children and Youth Services Review 161: 107679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cree, Viviene. 2013. New Practices of Empowerment. In The New Politics of Social Work. Edited by Mel Gray and Stephen A. Webb. Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan. [Google Scholar]

- Devaney, Carmel, Harriet Churchill, Angela Abela, and Rebecca Jackson. 2022. A Framework for Child and Family Support in Europe. Building Comprehensive Support Systems. Policy Brief. Madrid: EurofamNet. [Google Scholar]

- Engle, Ryann L., David C. Mohr, Sally K. Holmes, Marjorie Nealon Seibert, Melissa Afable, Jenniffer Leyson, and Mark Meterko. 2021. Evidence-based Practice and Patient-centered Care: Doing Both Well. Health Care Manage Review 46: 174–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Featherstone, Brid, Sue White, and Kate Morris. 2014. Re-Imagining Child Protection: Towards Humane Social Work with Families. Bristol: Policy Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, Iain. 2004. Neoliberalism, the Third Way and Social Work: The UK experience. Social Work and Society 2: 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, Anna, Hannah Blumhardt, and ATD Fourth World. 2018. Poverty, Exclusion and Child Protection Practice: The Contribution of “the Politics of Recognition & Respect”. European Journal of Social Work 21: 247–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, John. 2003. The Social Work Business, 1st ed. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Healy, Karen. 2005. Social Work Theories. In Context: Creating Frameworks for Practice. Houndmills: Palgrave MacMillan. [Google Scholar]

- Hyslop, Ian. 2018. Neoliberalism and Social Work Identity. European Journal of Social Work 21: 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Involve. 2012. Involve Strategy 2012–2015. Putting People First in Research. London: National Institute for Health Research. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan, Bill. 2001. Tough Love: Social Work, Social Exclusion and the Third Way. British Journal of Social Work 31: 527–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodele, Tadeja, and Nina Mešl. 2024. Reflexive Practice Learning as the Potential to Become a Competent Future Practitioner. CEPS Journal 14: 63–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotter, John. P. 1996. Leading Change. Boston, MA: Harvard Business Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, Elizabeth A., Alison Mudge, Sarah Knowles, Alison L. Kitson, Sarah C. Hunter, and Gill Harvey. 2018. “There is Nothing so Practical as a Good Theory”: A Pragmatic Guide for Selecting Theoretical Approaches for Implementation Projects. BMC Health Services Research 18: 857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madsen, William C. 2007. Collaborative Therapy with Multi-Stressed Families, 2nd ed. New York: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Madsen, William C. 2014. Taking It to the Streets: Family Therapy and Family-Centered Services. Family Process 53: 380–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matos, Ana R., and Liliana M. Sousa. 2004. How Multiproblem Families try to find Support in Social Services. Journal of Social Work Practice 18: 65–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattocks, Nicole Olivia. 2018. Social Action among Social Work Practitioners: Examining the Micro–Macro Divide. Social Work 63: 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, Hugh. 2012. Understanding Social Work Research. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Melo, Ana Teixeira, and Madalena Alarcão. 2013. Transforming Risks into Opportunities in Child Protection Cases: A Case Study with a Multisystemic, In-Home, Strength-Based Model. Journal of Family Psychotherapy 24: 17–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mešl, Nina. 2018. Collaborative social work in the community with families facing multiple challenges. Ljetopis socijalnog rada 25: 343–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mešl, Nina, and Tadeja Kodele. 2016. Collaborative Processes of Help and Development of New Knowledge in Social Work with Families. In Co-Creating Processes of Help: Collaborations with Families in the Community. Edited by Nina Mešl and Tadeja Kodele. Ljubljana: Faculty of Social Work, pp. 64–92. [Google Scholar]

- Mongkol, Kulachet. 2011. The Critical Review of New Public Management Model and its Criticisms. Research Journal of Business Management 5: 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munro, Eileen. 2011. The Munro Review of Child Protection: Final Report a Child-Centred System. London: United Kingdom. Department for Education. [Google Scholar]

- Naeem, Muhammad, Wilson Ozuem, Kerry Howell, and Silvia Ranfagni. 2023. A Step-by-Step Process of Thematic Analysis to Develop a Conceptual Model in Qualitative Research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 22: 16094069231205789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panciroli, Chiara, and Francesca Corradini. 2019. Doing Participatory Research with Families that Live in Poverty: The Process, Potential and Limitations. In Participatory Social Work: Research, Practice, Education. Edited by Mariusz Granosik, Anita Gulczyńska, Malgorzata Kostrzynska and Brian Littlechild. Lodz: Jagiellonian University Press, pp. 47–63. [Google Scholar]

- Parton, Nigel, and Patrick O’Byrne. 2000. Constructive Social Work: Towards a New Practice. New York: Palgrave. [Google Scholar]

- Reisch, Michael, and Jayshree Jani. 2012. The New Politics of Social Work Practice: Understanding Context to Promote Change. British Journal of Social Work 42: 1132–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rihter, Liljana. 2011. Slovenian social assistance legislation in the era of paradigmatic changes of social work concepts: Incentive or obstacle. In Soziale Arbeit Zwischen Kontrolle un Solidarität. Auf der Suche nach dem neuen Sozialen [Social Work Between Control and Solidarity. In Search for the New Social]. Edited by Piotr Salustowicz. Warszawa and Bielefeld: Societas Pars Mundi Publishing, pp. 171–92. [Google Scholar]

- Sharlin, Shlomo A., and Michal Shamai. 2000. Therapeutic Intervention with Poor, Unorganized Families: From Distress to Hope. New York: Haworth Press. [Google Scholar]

- Spolander, Gary, Lambert Engelbrecht, Linda Martin, Marianne Strydom, Irina Pervova, Päivi Marianen, Petri Tani, Alessandro Sicora, and Francis Adaikalam. 2014. The Implications of Neoliberalism for Social Work: Reflections from a Six-Country International Research Collaboration. International Social Work 57: 301–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tausendfreund, Tim, Jana Knot-Dickscheit, Gisela C. Schulze, Erik J. Knorth, and Hans Grietens. 2015. Families in multi-problem situations: Backgrounds, characteristics, and care services. Child & Youth Services 37: 4–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trappenburg, Margo, Thomas Kampen, and Evelin Tonkens. 2020. Social workers in a modernising welfare state: Professionals or street-level bureaucrats? The British Journal of Social Work 50: 1669–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaismoradi, Mojtaba, Hannele Turunen, and Terese Bondas. 2013. Content Analysis and Thematic Analysis: Implications for Conducting a Qualitative Descriptive Study. Nursing and Health Sciences 15: 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, Froma. 2006. Strengthening Family Resilience, 2nd ed. New York: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Weiner, Bryan J., Alecia S. Clary, Stacey L. Klaman, Kea Turner, and Amir Alishahi-Tabriz. 2020. Organizational Readiness for Change: What We Know, What We Think We Know, and What We Need to Know. In Implementation Science 3.0. Edited by Bianca Albers, Aron Shlonsky and Robyn Mildon. Cham: Springer, pp. 101–44. [Google Scholar]

- Weiner, Bryan J., Megan A. Lewis, and Laura A. Linnan. 2009. Using organization theory to understand the determinants of effective implementation of worksite health promotion programs. Health Education Research 24: 292–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zilberstein, Karen. 2021. Neoliberalism in Clinical Social Work Practice: The Benefits and Limitations of Embedded Ideals of Individualism and Resiliency. Critical and Radical Social Work 9: 339–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).