Abstract

This study systematically reviews the academic literature on unpaid care work during and after COVID-19, emphasizing gender dimensions. Using Web of Science (WOS) and SCOPUS, it analyzes 75 empirical articles published between 2020 and 2024 in English and Spanish. The selection focused on studies addressing unpaid care from multiple perspectives, particularly family dynamics. Quantitative analysis examined frequencies and percentages, while qualitative analysis explored content depth. Results reveal a dominant biomedical perspective on care, often neglecting emotional well-being and broader socioeconomic impacts. The present study also identifies a lack of critical reflection on care’s gendered nature and unequal caregiving responsibilities. Women, historically burdened with care duties, faced increased domestic demands during the pandemic, due to school closures and limited services, exacerbating gender inequality and reducing workforce participation. A bibliometric analysis of research on COVID-19, gender, and social care highlights limited collaboration, with studies fragmented across research groups and lacking international co-authorship. This study calls for governmental and international initiatives to foster cross-border collaboration, enabling a more comprehensive understanding of care that integrates emotional and socioeconomic aspects alongside health concerns. This would promote a more inclusive and reflective approach to unpaid caregiving research.

1. Introduction

Although framing care as a citizenship right suggests collective, rather than individual, responsibility (Tronto 2005), it does not ensure equitable distribution. Women still bear the main caregiving burden in welfare societies where the sexual division of labor persists (Carrasco and Domínguez 2011; Carrasco et al. 2011; Crompton 2006; Domínguez-Amorós et al. 2019).

Care work forms a significant part of—often migrant—women’s unpaid labor, including addressing family needs, volunteering in communities, or working as paid caregivers, a dynamic that exacerbates inequalities in gender, ethnicity, and class (Aulenbacher et al. 2018a, 2018b; Fraser 2016; Lyon and Glucksmann 2008; Lutz 2017). Hilary Graham (1993) defined care as both physical labor and emotional effort women invest in family well-being. This concept has since expanded to include public caregiving and paid “substitute services” provided in homes, often by women (Carrasquer 2013). Daly and Lewis (2000) introduced “social care” to describe activities and relationships, both material and symbolic, that address dependents’ needs, emphasizing well-being. “Social care” is the provision of personal and practical support to help people live their lives as independently as possible, especially those who require support due to age, disability, or other circumstances (Glasby 2017).

The International Labour Organization (ILO 2018) categorizes care work—paid or unpaid—into direct relational tasks (e.g., feeding a child) and indirect tasks (e.g., cooking). Gender perspectives have shaped debates on welfare states, exploring how state, market, family, and community intersect in caregiving responsibilities. Theoretical models such as Esping-Andersen’s welfare regimes (Esping-Andersen 1993) and Sainsbury’s gender regimes (Sainsbury 2016) highlight gender inequalities in care provision. Knijn and Verhagen (2007) outlined four care provision logics: public services, professional services, market-based institutions, and family caregiving. These highlight the diverse ways in which care is organized. Policies directly providing care services aim to recognize, reduce, and redistribute unpaid care through financial support, services, and flexible work arrangements (ILO 2018).

Spain’s welfare model is part of the Mediterranean regime, known not only for universalism in healthcare and education, but also for strong familism, weak public services, and reliance on informal care, often provided by migrant domestic workers (Bettio et al. 2006; Martínez Buján 2011). Since the 1990s, public, market, and third-sector collaboration in care services has increased, but the state often steps in only when families cannot (Leitner 2013; Saraceno 1995).

This review examines the impacts of COVID-19 on caregiving and gender disparities. It analyzes the academic literature addressing these issues from the pandemic’s onset to the present, using a multidisciplinary framework. To answer the primary research question—“What is documented on COVID-19, care work, and gender?”—a systematic review assessed the scope and focus of existing studies. A bibliometric analysis explored secondary questions about researcher collaboration and institutional partnerships in addressing the pandemic’s gendered caregiving challenges, highlighting research trends, gaps, and opportunities for collaboration1.

The article offers added value and innovation by employing a dual approach—combining systematic review and bibliometric analysis—to map the academic discourse on social care and gender throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. This integrated methodology allows for both a qualitative synthesis of content and a quantitative exploration of knowledge production patterns in this emerging field.

2. Materials and Methods

To achieve the first objective, this study conducted a systematic literature review (SLR), characterized by being systematic, comprehensive, explicit, and replicable (Hutton et al. 2016; Pardal-Refoyo and Pardal-Peláez 2020; Page et al. 2022). While the systematic review includes international literature, our analytical interest lies in understanding how the Spanish context fits within or diverges from broader trends.

This study followed the PRISMA-P (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Protocol), which ensures clarity, consistency, and integrity in reviews. This four-phase process involves identifying relevant literature, selecting sources based on predefined criteria, classifying articles using predetermined codes and themes, and determining the final articles for inclusion. Scopus and Web of Science (WOS) databases were used due to their extensive coverage, keyword search capabilities, and academic accessibility (Colares et al. 2020; de Souza et al. 2019). The WOS search focused on its core collection of journals, books, and conference proceedings in various disciplines.

In a systematic review, the selection of search terms is a fundamental element for its proper execution. To determine the keywords for this study, two distinct actions were undertaken prior to initiating the methodological process: a focus group with subject matter experts, and database searches using alternative keywords (such as unpaid care, domestic work, care work, and their respective permutations). The focus group was explicitly aimed at identifying the most appropriate and representative keywords for this study, while the second action resulted in an excessively broad, fragmented, and heterogeneous set of articles and references—a dataset with limited scope and low representativeness. The outcome of these two actions was the selection of the following keyword triplet: “social care”, “COVID”, and “gender”.

Search terms “social care + gender + COVID” were applied to both databases, filtering for articles and reviews. Searches, conducted in October 2024, yielded 54 references from Web of Science (TS = (COVID AND “social care” AND gender)) and 13 from Scopus. Following the PRISMA methodology, the following inclusion criteria were established to ensure the relevance and quality of the selected literature: (1) only publications dated between 2020 and 2024 were considered; (2) only peer-reviewed journal articles and systematic reviews were included, excluding books, book chapters, conference proceedings, and other grey literature; and (3) all selected publications had to be available in open access. After excluding duplicates and irrelevant or non-peer-reviewed items, 54 publications from the 2020–2024 period were retained for analysis.

For the bibliometric analysis, VOSviewer software (version 1.6.15) was used to generate relational maps among academic actors, such as authors, institutions, and research topics. Nodes represent scientific elements, while edges indicate interactions such as citations or co-authorships (Van Eck et al. 2010).

3. Results

A bibliometric analysis was conducted for each article, including the year of publication, keywords, number of citations, journal, and country of publication. Table 1 presents the 54 articles that meet the established criteria according to the systematic review analysis.

Table 1.

54 Articles selected for the systematic review (according to the PRISMA approach).

They present a similar bibliometric profile. Of the articles, 82.1% were scientific publications, primarily published between 2022 and 2023 (70.4%), almost all in English. The main countries of origin of the authors were Great Britain, Spain, Italy, Canada, and Ireland. It is noteworthy that nearly 80% of the articles focused on SDG 3 and 5, analyzing well-being and gender equality, with a strong biomedical perspective (Table 2).

Table 2.

Descriptive analysis of the articles.

In terms of the publication field, a very high percentage of articles were published in bioscience areas such as general medicine, psychology, geriatrics, etc., while the percentage of articles published in social sciences was significantly lower, suggesting a trend that was later confirmed.

Next, a bibliometric analysis of the selected articles was conducted to identify and evaluate research trends and patterns within this disciplinary field, addressing the second objective of this study. The first variable analyzed was the keywords. In total, there were 347 terms, with “COVID-19” and “gender” being the two most frequently repeated key terms in the studies. This seems logical, since these are two of the chosen search terms. However, the third search term (“social care”) does not appear until the eighth position in the keywords. In other words, many more works have been published on the relationship between COVID-19 and gender than those incorporating the concept of “social care”.

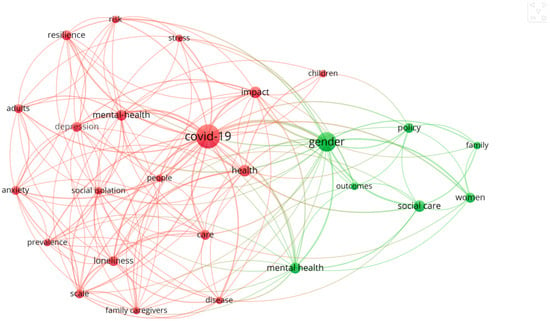

This idea is confirmed by the relationship maps. In these maps, each keyword is represented by a circle, and its size reflects the number of documents published with that keyword (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Relationship map of the keywords. Source: Map created using VOSviewer.

It is evident that two distinct clusters emerge, each formed around a central term that attracts the surrounding words and is visually represented by two different colors. The first cluster, comprising nineteen items (adults, anxiety, care, children, COVID-19, depression, disease, family caregivers, health, impact, loneliness, mental health, people, prevalence, resilience, risk, scale, social isolation, and stress), encompasses studies more closely related to health outcomes during or resulting from COVID-19. The second cluster, with seven items (family, gender, mental health, outcomes, policy, social care, and women), brings together articles focused on “gender”, the role of women in this context, and the outcomes, policies, and social care during the pandemic. The first cluster is more connected to biomedical studies—on both physical and mental health—while the second cluster pertains to articles related to gender and its stakeholders.

An individualized analysis of each search term used in the bibliographic review further confirms this assertion (Figure 2). The term “COVID-19” is linked to almost all the items in both clusters. The unprecedented situation led to a wide range of publications centered on this term across all levels of analysis. In contrast, the term “social care” stands apart. Despite the exceptional circumstances, there are relatively few studies that analyze the situation from the perspective of “social care”. Its analysis is more limited, and, consequently, there is less published work on this topic.

Figure 2.

Individual maps for each keyword in the search engine (the first is the map for “COVID-19”, the second for “gender”, and the third for “social care”). Source: Map created using VOSviewer.

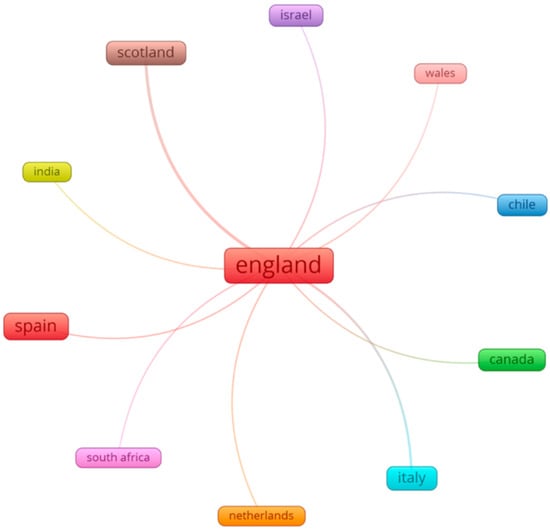

Figure 3 displays the co-authorship visualization among countries. Each circle represents a country, and its size reflects the number of published documents. The proximity or distance between countries indicates the strength of co-authorship ties. That is, the closer one country is to another, the stronger the co-authorship relationship between them. Conversely, countries that are farther apart have weaker co-authorship relationships. The colors represent clusters of countries that are relatively connected to each other.

Figure 3.

Map of a co-authorship network among countries whose authors published at least two documents. Source: Map created using VOSviewer.

England is the most productive territory, with twenty-five documents. It is followed by Spain and Scotland, with nine each, and Italy, with five, making England the nexus among all of them. The graph indicates a low level of co-authorship among the different countries. Analyzing the colors, England and Spain exhibit the highest collaboration in their co-authorship when it comes to publishing.

After conducting a cluster analysis of co-authorship arrangements, four groupings were identified. The first group consists of four countries (Canada, England, Spain, and Italy) that collaborate among themselves, followed by three isolated groups, each with one country: Scotland, Israel, and Chile. These relationships appear to stem more from personal connections or common projects among authors rather than from institutional or governmental policies.

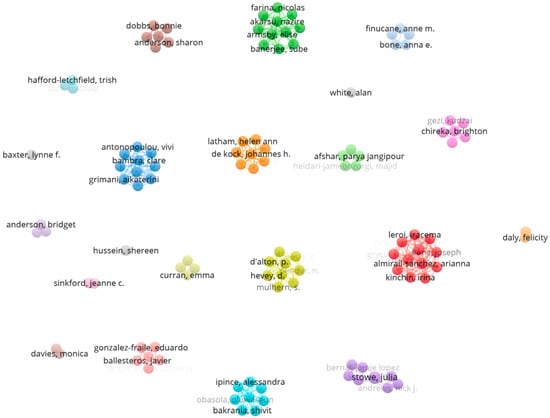

Finally, the analysis of authors in this study can be approached from various perspectives. It is important to highlight different aspects, such as productivity, collaboration (including co-authorship networks), and citation indices of authors and their works. To this end, a co-authorship study was conducted, analyzing the connections and awareness among authors (Newman 2001), identifying universities, research groups, and inter-institutional relationships. The threshold of two or more authors has been established as the criterion that indicates that works written in collaboration represent a co-authorship network.

The results of the map show a low degree of collaboration among the various research teams. Similarly to the patterns observed among countries and institutions, authors tend to publish with their research groups, but there is a lack of collaboration when it comes to publishing among them (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Co-authorship map. Source: Map created using VOSviewer.

They are grouped into twenty-one different clusters, with each cluster representing a research group focused on the topic. The groups are of similar sizes: the red cluster has the most members, comprising twelve members, followed by the green cluster, with eleven members, the blue cluster, with ten, and so forth. The most productive authors hold prominent positions in different groups, although their positions are not necessarily central. Furthermore, the number of co-authorships varies significantly.

The most cited article (489 citations among the selected articles, with a total of 934 citations) is by De Kock, JH; Latham, HA; Leslie, SJ; Grindle, M; Munoz, SA; Ellis, L; Polson, R; and O’Malley, CM. However, this does not indicate that the authors belong to the most prolific research group, as they only have one publication among those included in the systematic review. The size of their group is like that of others, consisting of eight researchers. Similarly, author Julia Stowe is the second most cited author, but, in this case, she has two publications within the selected articles, albeit still within her research group of eight researchers. Therefore, the size of a group does not appear to be a variable that affects its productivity.

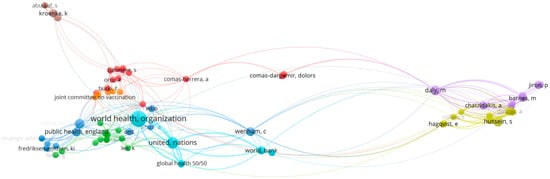

In contrast, when analyzing the references cited in each of the articles, a relationship map does emerge (Figure 5). In this case, there are government references that are included in a high percentage of the articles. Thus, citations from official organizations, such as the World Health Organization, Public Health England, the United Nations, and the World Bank, are widely utilized by the authors. Additionally, significant relationships exist among the citations of each article.

Figure 5.

Co-citation map. Source: Map created using VOSviewer.

4. Discussion

Regarding the systematic review, the application of the PRISMA methodology within the WOS and Scopus databases allowed for the selection of a total of 54 definitive articles for the corresponding review, of which 50 are in English and 4 are in Spanish. The review period spanned five years (2020–2024), which was necessary to establish the advancements in care management following the pandemic, identify any changes, and explore whether new interpretations have emerged concerning the central issue of care inequality. It should be noted that the systematic review was not geographically confined to any specific country or continent.

The results reveal the predominance of a biomedical perspective in understanding care, alongside a lack of reflective engagement concerning this understanding. Analyzing the keywords of the selected articles, they can be segmented into two distinct clusters: one more closely linked to the biomedical domain, and another more associated with the social domain. The first cluster encompasses studies, primarily related to health, that occurred during or as a result of COVID-19, consisting of nineteen items (adults, anxiety, care, children, COVID-19, depression, disease, family caregivers, health, impact, loneliness, mental health, people, prevalence, resilience, risk, scale, social isolation, and stress). Conversely, the second cluster comprises seven items (family, gender, mental health, outcomes, policy, social care, and women) that aggregate articles related to “gender”, the role of women in this context, and the resulting policies and social care during the pandemic.

From the analysis of the articles in the second cluster, a critical reflection on the nature of care itself emerges, particularly regarding how gender affects the distribution of this type of work. Historically, women have borne most caregiving responsibilities, a trend that intensified during the pandemic, when the closure of institutions such as schools and care centers compelled many women to assume increased responsibilities at home. This phenomenon has perpetuated gender inequalities, limiting women’s participation in the labor market and exacerbating wage and opportunity gaps.

The results indicate that the term “COVID-19” is associated with almost all keywords in both clusters. The context was so exceptional that it led to publications focused on this situation across various analytical levels. At the other end of the spectrum lies the term “social care”. Despite the exceptional nature of the circumstances, the number of studies analyzing the situation from the perspective of “social care” is minimal.

Examining the countries where the publications originate, the majority are European, with England being the most productive territory, followed by Spain, Scotland, and Italy. Outside of Europe, Canada, Israel, and Chile have contributed research on the topic. However, these relationships appear to be more personal or project-based, rather than stemming from institutional or governmental policies.

This assertion is further corroborated by the analysis of co-authorships. The results demonstrate a limited degree of collaboration among various research teams. Like the patterns observed with countries and institutions, authors publish with their respective research groups, but do not collaborate with one another when publishing. However, an analysis of the bibliographic references cited in each article reveals a network of relationships. Therefore, while researchers do not collaborate to publish, they are aware of the publications produced by colleagues at other universities and around the world.

Finally, it is important to note that some limitations of our systematic review correspond to what Dickersin (1994) refers to as “publication bias”. We can assume that a significant portion of the articles analyzed reflects the interests of the scientific community and the journals themselves, even if this means omitting relevant aspects of the research. This leads to a phenomenon wherein such articles tend to align with their initial assumptions and/or hypotheses, often neglecting their own limitations and aspects that do not conform to established views. Moreover, regarding the limitations inherent in the design of our review, we consider the sources utilized for article selection and their respective characteristics. The final limitation of this study concerns the process of keyword selection for the systematic review. Although significant efforts were undertaken to ensure a rigorous and representative choice—including a focus group with subject matter experts and exploratory searches using alternative terms, such as unpaid care, domestic work, and care work—the final selection of keywords inevitably influenced the scope of the literature reviewed. As a result, the present study relied on the keyword triplet “social care”, “COVID”, and “gender”, which, although conceptually coherent, may have excluded relevant studies indexed under different terminologies.

5. Conclusions

This study identifies the dissemination of literature and summarizes indexed journal publications on “COVID”, “gender”, and “social care” in a table. The results demonstrate the predominance of a biomedical perspective in understanding care, and the limited reflective engagement regarding this understanding. Much of the existing literature addresses care from a health and physical well-being perspective, overlooking other important dimensions such as emotional well-being and the social and economic implications of unpaid care. In the future, it will be essential to position care as a central element of human life, reorganizing and collectivizing it socially, which should be a line of research analyzing the feasibility of such initiatives.

The bibliometric analysis of these articles yields insights into the limited collaboration in publishing and researching the subject matter. Article publication appears to be fragmented within research groups, lacking co-authorship both among them and across countries. There is a need to promote governmental or supranational strategies that create networks or international projects on this topic and connect these groups to enhance the cross-sectional and international analysis of the subject. Furthermore, such collaborative efforts would not only enrich the research, but also facilitate a more coordinated global response to the issues surrounding caregiving, gender, and the pandemic. By connecting research groups, policymakers, and practitioners across different countries, it would be possible to enhance the cross-sectional and international analysis of the subject, leading to more comprehensive, nuanced, and globally relevant findings. Ultimately, this could drive more effective, evidence-based interventions and policies that address the complex, interconnected challenges in social care and gender equity, particularly in the aftermath of the COVID-19 crisis.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.D.-A., P.A.-C. and I.M.-Y.; Methodology, M.D.-A., P.A.-C. and I.M.-Y.; Software, P.A.-C.; Validation, M.D.-A., P.A.-C. and I.M.-Y.; Formal analysis, M.D.-A., P.A.-C. and I.M.-Y.; Investigation, M.D.-A., P.A.-C. and I.M.-Y.; Resources, M.D.-A., P.A.-C. and I.M.-Y.; Writing—original draft, P.A.-C. and I.M.-Y.; Writing—review & editing, M.D.-A., P.A.-C. and I.M.-Y.; Funding acquisition, M.D.-A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project was funded by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation under Grant PID2020-118801RB-I00. Moreover, this paper was elaborated in the context of the INCASI2 project that has received fundings from the European Union’s Horizon Europe research and innovation programme under the Marie Sklodowska-Curie grant agreement No. 101130456.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset for this study is based on the list of articles presented in Table 1; as such, the data are already published and directly included in the paper.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the members of the R&D project who have helped with their comments, reviews, and readings.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Note

| 1 | The bibliometric analysis helps identify clusters of collaboration and emerging topics, while the systematic review enables deeper exploration of content. This dual approach allows us to explore how care and gender have been framed in the academic literature during and after the pandemic. |

References

- Allard, Camille, and Grace J. Whitfield. 2024. Guilt, care, and the ideal worker: Comparing guilt among working carers and care workers. Gender, Work & Organization 31: 666–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, Bridget, Friedrich Poeschel, and Martin Ruhs. 2021. Rethinking labour migration: COVID-19, essential work, and systemic resilience. Comparative Migration Studies 9: 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, Sharon, Jasneet Parmar, Tanya L’Heureux, Bonnie Dobbs, Lesley Charles, and Peter George J. Tian. 2022. Family caregiving during the COVID-19 pandemic in Canada: A mediation analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19: 8636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrews, Nick J., Julia Stowe, Mary E. B. Ramsay, and Elizabeth Miller. 2022. Risk of venous thrombotic events and thrombocytopenia in sequential time periods after ChAdOx1 and BNT162b2 COVID-19 vaccines: A national cohort study in England. The Lancet Regional Health–Europe 13: 100260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aulenbacher, Brigitte, Fabienne Décieux, and Birgit Riegraf. 2018a. Capitalism goes care: Elder and child care between market, state, profession, and family and questions of justice and inequality. Equality, Diversity and Inclusion: An International Journal 37: 347–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aulenbacher, Brigitte, Fabienne Décieux, and Birgit Riegraf. 2018b. The economic shift and beyond: Care as a contested terrain in contemporary capitalism. Current Sociology 66: 517–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxter, Lynne F. 2020. A Hitchhiker’s Guide to caring for an older person before and during coronavirus-19. Gender, Work & Organization 27: 763–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benoit, Verena, and Eva-Maria Euchner. 2023. Contested social care—Is there a ’right’ way? How public investments diminish attitudinal differences towards social care in 34 European countries. European Journal of Politics and Gender 6: 183–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettio, Francesca, Annamaria Simonazzi, and Paola Villa. 2006. Change in care regimes and female migration: The ‘care drain’ in the Mediterranean. Journal of European Social Policy 16: 271–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bone, Anna E., Anne M. Finucane, Javiera Leniz, Irene J. Higginson, and Katherine E. Sleeman. 2020. Changing patterns of mortality during the COVID-19 pandemic: Population-based modelling to understand palliative care implications. Palliative Medicine 34: 1193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewin, Chris R., Michael A. Bloomfield, Jo Billings, Jasmine Harju-Seppänen, and Talya Greene. 2021. What symptoms best predict severe distress in an online survey of UK health and social care staff facing COVID-19: Development of the two-item Tipping Point Index. BMJ Open 11: e047345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brulin, Emma, Constanze Leineweber, and Paraskevi Peristera. 2022. Work–Life Enrichment and Interference Among Swedish Workers: Trends From 2016 Until the COVID-19 Pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology 13: 854119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasco, Cristina, and Màrius Domínguez. 2011. Family Strategies for meeting care and domestic work needs: Evidence from Spain. Feminist Economics 17: 159–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasco, Cristina, Cristina Borderías, and Teresa Torns, eds. 2011. El trabajo de cuidados. Historia, teoría y políticas. Madrid: Los Libros de la Catarata, pp. 13–96. [Google Scholar]

- Carrasquer, Pilar. 2013. El redescubrimiento del trabajo de cuidados: Algunas reflexiones desde la sociología. Cuadernos de Relaciones Laborales 31: 91–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chattoo, Sangeeta, Dipty Jain, Nidhi Nashine, and Rajan Singh. 2023. A social profile of deaths related to sickle cell disease in India: A case for an ethical policy response. Frontiers in Public Health 11: 1265313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cogan, Nicola, Lisa McInnes, Vanissia Lingg, Paul Flowers, Susan Rasmussen, and Lynn Williams. 2023. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among health and social care workers during mass vaccination in Scotland. Psychology, Health & Medicine 28: 2938–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colares, Gustavo S., Naira Dell’Osbel, Patrik G. Wiesel, Gislayne A. Oliveira, Pedro Henrique Z. Lemos, Fagner P. da Silva, Carlos A. Lutterbeck, Lourdes T. Kist, and Ênio L. Machado. 2020. Floating treatment wetlands: A review and bibliometric analysis. Science of the Total Environment 714: 136776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comas-d’Argemir, Dolors, and Silvia Bofill-Poch. 2022. Cuidados a la vejez en la pandemia. Una doble devaluación. Disparidades. Revista De Antropología 77: e001a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, Alison, Ruth Lewis, Micaela Gal, Natalie Joseph-Williams, Jane Greenwell, Angela Watkins, Alexandra Strong, Denitza Williams, Elizabeth Doe, Rebecca-Jane Law, and et al. 2024. Informing evidence-based policy during the COVID-19 pandemic and recovery period: Learning from a national evidence centre. Global Health Research and Policy 9: 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crompton, Rosemary. 2006. Employment and the Family: The Reconfiguration of Work and Family Life in Contemporary Societies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curran, Emma, Michael Rosato, Finola Ferry, and Gerard Leavey. 2023. Prevalence and risk factors of psychiatric symptoms among older people in England during the COVID-19 pandemic: A latent class analysis. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction 21: 3772–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, Paulo Roberto, Jr., Paloma Porto, Mariela Campos Rocha, Eduardo Ryô Tamaki, Marcela Garcia Corrêa, Michelle Fernandez, Gabriela Lotta, and Denise Nacif Pimenta. 2023. Women and working in healthcare during the COVID-19 pandemic in Brazil: Bullying of colleagues. Globalization and Health 19: 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daley, Stephanie, Nicolas Farina, Laura Hughes, Elise Armsby, Nazire Akarsu, Joanna Pooley, Georgia Towson, Yvonne Feeney, Naji Tabet, Bethany Fine, and et al. 2022. COVID-19 and the quality of life of people with dementia and their carers—The TFD-C19 study. PLoS ONE 17: e0262475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daly, Felicity, and Claire Edwards. 2022. Tracing State Accountability for COVID-19: Representing Care within Ireland’s Response to the Pandemic. Social Policy and Society, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, Mary, and Jane Lewis. 2000. The concept of social care and the analysis of contemporary welfare states. The British Journal of Sociology 51: 281–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, Monica, and Luke Hogarth. 2021. The effect of COVID-19 lockdown on psychiatric admissions: Role of gender. BJPsych Open 7: e112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Kock, Johannes H., Helen Ann Latham, Stephen J. Leslie, Mark Grindle, Sarah-Anne Munoz, Liz Ellis, Rob Polson, and Christopher M. O’Malley. 2021. A rapid review of the impact of COVID-19 on the mental health of healthcare workers: Implications for supporting psychological well-being. BMC Public Health 21: 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Laat, Kim, Andrea Doucet, and Alyssa Gerhardt. 2023. More than employment policies? Parental leaves, flexible work and fathers’ participation in unpaid care work. Community, Work & Family 26: 562–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, Rogério Ribeiro, de Vanessa Holanda Righetti Abreu, and Jaílson Santoss de Novais. 2019. Melissopalynology in Brazil: A map of pollen types and published productions between 2005 and 2017. Palynology 43: 690–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickersin, Kay. 1994. Sobre la existencia y los factores de riesgo del sesgo de publicación. Boletín de la Oficina Sanitaria Panamericana (OSP) 116: 435–46. Available online: https://iris.paho.org/handle/10665.2/15704 (accessed on 25 April 2025).

- Domínguez-Amorós, Màrius, Leticia Muñiz Terra, and María Gabriela Rubilar Donoso. 2019. El trabajo doméstico y de cuidados en las parejas de doble ingreso. Análisis comparativo entre España, Argentina y Chile. Papers 104: 337–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorado Barbé, Ana Isabel, Jesús Manuel Pérez Viejo, Juan Brea Iglesias, and Jorge López Pérez. 2023. Impact of Social and Personal Factors on Psychological Distress in the Spanish Population in the COVID-19 Crisis. The British Journal of Social Work 53: 977–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, Luis Miguel, and Ho Fai Lo. 2023. Motivations, career decisions, and decision-making processes of mid-aged Master of Social Work Students. Social Work Education 43: 2135–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, Fiona J., Ian W. Garner, Craig D. Murray, Cathal Doyle, and Jane Simpson. 2023. The joint impact of symptom deterioration and social factors on wellbeing for people with Parkinson’s during the COVID-19 pandemic in the UK. Journal of the Neurological Sciences 452: 120768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esping-Andersen, Gosta. 1993. Los tres mundos del estado del bienestar. Valencia: Edicions Alfons el Magnànim-IVEI. Available online: https://pps.secyt.unpa.edu.ar/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Esping-Andersen_Los-tres-mundos-del-Estado-del-bienestar_Cap_2.pdf (accessed on 25 April 2025).

- Estévez, Ana, Laura Macía, Gema Aonso-Diego, and Marta Herrero. 2024. Early maladaptive schemas and perceived impact of COVID-19: The moderating role of sex and gambling. Current Psychology 43: 17985–8000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, N. 2016. Contradictions of capital and care. New Left Review 100: 99–117. [Google Scholar]

- García-Basanta, Andrea, and Francesca Romagnoli. 2023. El origen de los comportamientos de cuidado: Higiene y cuidado social en Homo neanderthalensis. Una revisión crítica. Complutum 34: 283–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasby, Jon. 2017. Understanding Health and Social Care. Bristol: Policy Press. [Google Scholar]

- Goffe, Louis, Vivi Antonopoulou, Carly J. Meyer, Fiona Graham, Mei Yee Tang, Jan Lecouturier, Aikaterini Grimani, Clare Bambra, Michael P. Kelly, and Falko F. Sniehotta. 2021. Factors associated with vaccine intention in adults living in England who either did not want or had not yet decided to be vaccinated against COVID-19. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics 17: 5242–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Fraile, Eduardo, Javier Ballesteros, José-Ramon Rueda, Borja Santos-Zorrozúa, Ivan Solà, and Jenny McCleery. 2021. Remotely Delivered Information, Training and Support for Informal Caregivers of People with Dementia. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, Hillary. 1993. Social divisions in caring. Women’s Studies International Forum 16: 461–70. Available online: https://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/21063/ (accessed on 25 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Grycuk, Emilia, Yaohua Chen, Arianna Almirall-Sanchez, Dawn Higgins, Miriam Galvin, Joseph Kane, Irina Kinchin, Brian Lawlor, Carol Rogan, Gregor Rusell, and et al. 2022. Care burden, loneliness, and social isolation in caregivers of people with physical and brain health conditions in English-speaking regions: Before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 37: 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphrey, Harvey, Yvette Taylor, and Navan Govender. 2023. AS IS; Access and Inclusion in KE Events. In AS IS: A Play Based on Research about Trans, Intersex and LGBTI Activist Relationships. Glasgow: University of Strathclyde. [Google Scholar]

- Hussein, Shereen. 2022. Employment inequalities among British minority ethnic workers in health and social care at the time of COVID-19: A rapid review of the literature. Social Policy and Society 21: 316–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutton, Brian, Ferran Catalá-López, and David Moher. 2016. La extensión de la declaración PRISMA para revisiones sistemáticas que incorporan metaanálisis en red: PRISMA-NMA. Medicina Clínica 147: 262–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Labour Organization (ILO). 2018. Perspectivas sociales y del empleo en el mundo 2018: Sostenibilidad. Geneva: Organización Internacional del Trabajo. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/sites/default/files/wcmsp5/groups/public/@dgreports/@dcomm/@publ/documents/publication/wcms_638150.pdf (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- Jirón Martínez, P. A., M. I. Solar-Ortega, M. D. Rubio Rubio, S. R. Cortés Morales, B. E. Cid Aguayo, and J. A. Carrasco Montagna. 2022. La espacialización de los cuidados. Entretejiendo relaciones de cuidado a través de la movilidad. Revista INVI 37: 199–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirsebom, Freja C., Nick Andrews, Julia Stowe, Samuel Toffa, Ruchira Sachdeva, Elleen Gallagher, Natalie Groves, Anne-Marie O’Connell, Meera Chand, Mary Ramsay, and et al. 2022. COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness against the omicron (BA. 2) variant in England. The Lancet Infectious Diseases 22: 931–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knijn, Trudie, and Stijin Verhagen. 2007. Contested professionalism payments for care and the quality of home care. Administration & Society 39: 451–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitner, Sigrid. 2013. Varianten von Familialismus. Berlin: Duncker und Humblot, pp. 1–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liotta, Giusseppe, Leonardo Emberti Gialloreti, Maria Cristina Marazzi, Olga Madaro, Maria Chiara Inzerilli, Margherita D’Amico, Stefano Orlando, Paola Scarcella, Elisa Terracciano, Susanna Gentili, and et al. 2022. Pro-active monitoring and social interventions at community level mitigate the impact of Coronavirus (COVID-19) epidemic on older adults’ mortality in Italy: A retrospective cohort analysis. PLoS ONE 17: e0261523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowry, Damien, David Hevey, Charlotte Wilson, Veronica O’Doherty, S. O’Sullivan, Clodagh Finnerty, N. Pender, P. D’Alton, and Sinead Mulhern. 2023. Wellbeing and mental health outcomes amongst hospital healthcare workers during COVID-19. Irish Journal of Psychological Medicine 40: 402–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutz, Helma. 2017. Care as a fictitious commodity: Reflections on the intersections of migration, gender and care regimes. Migration Studies 5: 356–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyon, Dawn, and Miriam Glucksmann. 2008. Comparative configurations of care work across Europe. Sociology 42: 101–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madia, Joan E., Francesco Moscone, and Catia Nicodemo. 2023. Studying informal care during the pandemic: Mental health, gender and job status. Economics & Human Biology 50: 101245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez Buján, Raquel. 2011. La reorganización de los cuidados familiares en un contexto de migración internacional. Cuadernos de Relaciones Laborales 29: 93–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbiba, Beacon, Brighton Chireka, Edward Kunonga, Kudzai Gezi, Paul Matsvai, and Zeb Manatse. 2020. At the deep end: COVID-19 experiences of Zimbabwean health and care workers in the United Kingdom. Journal of Migration and Health 1: 100024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medina-Perucha, Laura, Constanza Jacques-Aviñó, Tomás López-Jiménez, Catuxa Maiz, and Anna Berenguera. 2023. Spanish residents’ experiences of care during the first wave of the COVID-19 syndemic: A photo-elicitation study. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being 18: 2172798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merenda, Aluette, and Maria Garro. 2022. Shielding families’ experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic: A review across the UK and Italy. Minerva Psychiatry 63: 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michie, Susan, Henry W. W. Potts, Robert West, R. Amlȏt, Louise E. Smith, Nicola T. Fear, and G. James Rubin. 2021. Factors associated with non-essential workplace attendance during the COVID-19 pandemic in the UK in early 2021: Evidence from cross-sectional surveys. Public Health 198: 106–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, Mark E. J. 2001. The structure of scientific collaboration networks. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 98: 404–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, Alexandra, Tor-Olav Naevestad, Kati Orru, Kristi Nero, Abriel Schieffelers, and Sunniva Frislid Meyer. 2023. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on socially marginalised women: Material and mental health outcomes. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 93: 103739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, Mattheww J., David Moher, and Joanne E. McKenzie. 2022. Introduction to PRISMA 2020 and implications for research synthesis methodologists. Research Synthesis Methods 13: 156–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagorek-Eshel, Shira, Haneen Elias, Raghda Alnabilsy, and Shulamit Grinapol. 2022. The association of social factors and COVID-19–related resource loss with depression and anxiety among Arabs in Israel. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy 14: 310–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmar-Santos, Ana M., Azucena Pedraz-Marcos, Laura A. Rubio-Casado, Montserrat Pulido-Fuentes, María Eva García-Perea, and María Victoria Navarta-Sanchez. 2023. Resilience among primary care professionals in a time of pandemic: A qualitative study in the Spanish context. BMJ Open 13: e069606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardal-Refoyo, José L., and Beatriz Pardal-Peláez. 2020. Anotaciones para estructurar una revisión sistemática. Revista ORL 11: 155–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, Camila, Shivit Bakrania, Alessandra Ipince, Zahrah Nesbitt-Ahmed, Oluwaseun Obasola, Dominic Richardson, Jorinde Van de Scheur, and Ruichuan Yu. 2022. Impact of social protection on gender equality in low-and middle-income countries: A systematic review of reviews. Campbell Systematic Reviews 18: e1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sainsbury, Diana. 2016. Gender, migration and social policy. In Handbook on Migration and Social Policy. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, pp. 419–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajir, Zakaria. 2021. Acuerdos comerciales, migratorios, de seguridad y de empleo centro-periferia. Un análisis de ecología-mundo. Relaciones Internacionales 47: 201–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraceno, Chiara. 1995. Familismo ambivalente y clientelismo categórico en el Estado del Bienestar italiano. In El Estado del Bienestar en la Europa del sur. Córdoba: Instituto de Estudios Sociales Avanzados, pp. 261–88. [Google Scholar]

- Sekeris, Athanasios, Thikra Algahtani, Daniyar Aldabergenov, Kirsten L. Rock, Fatima Auwal, Farah Aldewaissan, Bryn D. Williams, Nicola J. Kalk, and Caroline S. Copeland. 2023. Trends in deaths following drug use in England before, during, and after the COVID-19 lockdowns. Frontiers in Public Health 11: 1232593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikhbardsiri, Hojjat, Asghar Tavan, Parya J. Afshar, Sahar Salahi, and Majid Heidari-Jamebozorgi. 2022. Investigating the burden of disease dimensions (time-dependent, developmental, physical, social and emotional) among family caregivers with COVID-19 patients in Iran. BMC Primary Care 23: 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Sonya G., and Jeanne C. Sinkford. 2022. Gender equality in the 21st century: Overcoming barriers to women’s leadership in global health. Journal of Dental Education 86: 1144–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soronellas Masdeu, Montserrat, Carmen Gregorio Gil, and Marcela Jabbaz Churba. 2022. Sort it out as best you can! Moral dilemmas in family care for elderly and dependent people during the pandemic. Disparidades-Revista de Antropologia 77: 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomar, Aditi, and Mahbub Hossain. 2022. Health disparities among older women in India during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Health Research 36: 764–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toze, Michael, Sue Westwood, and Trish Hafford-Letchfield. 2023. Social support and unmet needs among older trans and gender non-conforming people during the COVID-19 ‘lockdown’in the UK. International Journal of Transgender Health 24: 305–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tronto, Joan. 2005. Care as the work of citizens: A Modest Proposal. In Women and Citizenship. New York: Oup Usa. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Undurraga, Rosario, and Natalia López-Hornickel. 2023. The Experience of Women Regarding Chilean Government Measures during the COVID‚Äê19 Pandemic. Bulletin of Latin American Research 42: 564–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Eck, Nees Jan, Ludo Waltman, Rommert Dekker, and Jan Van Den Berg. 2010. A comparison of two techniques for bibliometric mapping: Multidimensional scaling and VOS. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology 61: 2405–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, Alan. 2020. Men and COVID-19: The aftermath. Postgraduate Medicine 132 S4: 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yakubovich, Alexa R., Bridget Steele, Catherine Moses, Elizabeth Tremblay, Monique Arcenal, Patricia O’Campo, Robin Mason, Janice Du Mont, Maria Huijbregts, Lauren Hough, and et al. 2023. Recommendations for Canada’s National Action Plan to End Gender-Based Violence: Perspectives from leaders, service providers and survivors in Canada’s largest city during the COVID-19 pandemic. Promotion de la Santé et Prévention des Maladies Chroniques au Canada 43: 155–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuma, Thembelihle, Jacob Busang, Sphesihle Hlongwane, Glory Chidumwa, Dumsani Gumede, Manono Luthuli, Jaco Dreyer, Carina Herbst, Nonhlanhla Okesola, Natsayi Chimbindi, and et al. 2024. A mixed methods process evaluation: Understanding the implementation and delivery of HIV prevention services integrated within sexual reproductive health (SRH) with or without peer support amongst adolescents and young adults in rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Trials 25: 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).