Abstract

Background: Violence legitimization has been associated with the myths of romantic love. In the Portuguese context, there are no available standardized tools to assess it. This study aimed to develop the adaptation and validation of the Portuguese version of the Scale of Myths of Romantic Love (SMRL) in youth and emerging adults. Also, the acceptance of myths of romantic love was described. Methods: The sample comprised 165 individuals (83% female) aged from 18 to 30 (M = 23.01; SD = 3.33). Results: Confirmatory factor analysis supported the two-factor correlated structure found in the original validation: Idealized Love (IL) and Distorted Love (DL). The selected nested model obtained acceptable good-of-fit indices. Reliability analysis indicated acceptable internal consistency (α = 0.728; ω = 0.711) and the item-factor correlations were strong. Gender differences in the endorsement of romantic myths were found. Males obtained significantly greater acceptance of need for a couple and ambivalence myths. Females significantly endorsed the half orange myth. Conclusions: Our findings supported the two-factor related structure of the SMRL Portuguese version. Gender-based differences in romantic beliefs and their potential link to violence legitimization, gender stereotypes, and love perception are highlighted as in need of further studies. This research provides evidence regarding the psychometric properties of the Escala de Mitos do Amor Romântico (EMAR).

1. Introduction

In the past decade, the myths of romantic love have become an area of increasing interest in research involving young populations due to their association with violence.

Since the conceptualization of Sternberg’s (1986) triangular theory of love, the construct of love has evolved over time. New research trends have focused on understanding the mechanisms, ontogeny, functions, and phylogeny that explain romantic love (Bode and Kushnick 2021). In this regard, proximate explanations provide insight into the psychological processes and mechanisms that enable individuals to develop and experience romantic love (Bode and Kushnick 2021). Classical theoretical models of love, such as confluent love (Giddens 1992) and consummated love (Sternberg 1986), offer balanced and healthy views of love. Love perception in Portuguese culture is mainly passionate (eros—physical attraction and emotional intensity), committed (storge—companionship-driven love), and affectionate (agape—altruistic and selfless love) (Neto and Pinto 2025). Despite love being one of the most desirable emotions of human beings, the characteristics of romantic love promote believing in myths linked to this type of love (Jiménez-Picón et al. 2022). In this regard, the myths of romantic love are particularly relevant, as they represent how romantic love is perceived in intimate relationships, which is shaped by socio-cultural factors (Bonilla-Algovia and Rivas-Rivero 2018). From an anthropological point of view, myths are shared beliefs and narratives that form part of a culture’s collective consciousness (Bidney 1967). Understanding myths as a cultural phenomenon, they maintain a certain system of values and social norms (Shynkaruk et al. 2018). Specifically, the myths of romantic love were defined by Yela (2003) as a set of socially shared beliefs about the nature of love. Despite emerging theoretical models in recent years, there is a consensus in the scientific community regarding the following nine myths: omnipotence (love can overcome everything), half orange (there is a predestined partner for everyone), need for a couple (happiness cannot be achieved without a partner), eternal passion (the passion of infatuation must last over time), exclusiveness (one can only love one person), marriage (romantic love leads to marriage), abnegation (loving involves self-sacrifice for the partner), jealousy (jealousy is a sign of true love), and ambivalence (love and violence can coexist in a relationship) (Bonilla-Algovia and Rivas-Rivero 2020; Bosch et al. 2007; Cubells-Serra et al. 2021; Yela 2003). Previous research has suggested that some of these myths, such as jealousy and ambivalence, are associated with intimate partner violence (IPV) due to the negative influence these limiting beliefs have on the recognition of certain behaviors as forms of violence (Cava et al. 2020). In this way, the myths of romantic love contribute to the normalized perception of certain controlling behaviors (Linares et al. 2021) and are positively associated with the legitimization of IPV (Baldry and Pagliaro 2014; Hester et al. 2010; Lelaurain et al. 2021; Papp et al. 2017). Additionally, romantic love has been identified as a risk factor for gender-based violence (GbV) (Jiménez-Picón et al. 2022). Although several studies have analyzed romantic love myths in young populations across different countries and contexts (Cava et al. 2020; Fernández et al. 2023; Goenaga 2021; Rivas-Rivero and Bonilla-Algovia 2021; Standley 2022; Triano et al. 2021), it is noteworthy that there is a lack of empirical studies assessing romantic love myths in the Portuguese context.

According to the EU Gender-based Violence Survey (FRA et al. 2024), the prevalence of violence experienced by women aged 18–74 in the EU is 32%. The proportion is notably higher in the young (18–29 years) and young adult (30–44 years) populations, at 35% for both groups. In Portugal, the prevalence of physical and/or sexual gender-based violence is 10.3%. However, when psychological violence is included, this proportion rises to 22.5% (FRA et al. 2024). Regarding the legitimization of violence during dating, a recent national study (União de Mulheres Alternativa e Resposta [UMAR] 2024) demonstrated that young males legitimize certain types of violence more than females, including: control (64.1% vs. 46.8%), psychological violence (44.0% vs. 24.9%), stalking (39.9% vs. 24.0%), sexual violence (41.1% vs. 20.8%), social network violence (25.5% vs. 13.6%), and physical violence (13.9% vs. 6.3%). Also, several studies have obtained high rates of IPV in both adolescent (Neves 2016; Perista et al. 2012) and adult (Neves and Nogueira 2010) Portuguese populations.

Given the limited number of studies analyzing romantic love myths in young populations within the Portuguese context, as well as the alarming data on the legitimization of violence among the youth population in the country, there is a clear need for a valid and reliable psychometric instrument to assess the myths of romantic love in this context. In fact, the deconstruction of gendered narratives of romantic love has been emphasized as a necessity for over a decade in the Portuguese context (Neves and Nogueira 2010), but this gap still persists in terms of quantitative assessment. Tackling these research gaps requires a validated tool for evaluating romantic love myths. One of the most recent instruments for the assessment of the myths of romantic love is the Scale of Myths of Romantic Love (SMRL; Bonilla-Algovia and Rivas-Rivero 2020). This psychometric tool offers several advantages, as it enables the assessment of a wide range of romantic myths, including both idealized and distorted beliefs about love. Moreover, the SMRL allows for the assessment of the romantic myth of ambivalence, incorporating an implicit analysis of violence (Bonilla-Algovia et al. 2024). To the best of our knowledge, there is currently no validated instrument in Portuguese to assess the myths of romantic love.

Therefore, this study aimed to adapt and validate the Scale of Myths of Romantic Love (SMRL) into Portuguese. The hypothesis of this study was that the two-factor correlated structure of the original test would be confirmed in a sample of Portuguese youth and young adults.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

The sample consisted of 165 young people from Portugal, aged between 18 and 30 years (M = 23.01; SD = 3.33). Most participants were female (83.0%). It is noteworthy that both the age mean and the gender distribution were similar to those in the original validation (Bonilla-Algovia and Rivas-Rivero 2020). Participants were recruited using a non-probabilistic snowball sampling method (Goodman 1961) via social media. The sample comprised youth and young adults from the general population, including university students enrolled in Psychology, Communication Studies, Translation Studies, and Social Work programs. Inclusion criteria were as follows: aged between 18 and 30 years old, Portuguese nationality, and residence in Portugal. It is important to mention that the sample size and the proportion of male participants in this study represent a significant limitation.

2.2. Measurements

Myths of romantic love. The Scale of Myths of Romantic Love (SMRL; Bonilla-Algovia and Rivas-Rivero 2020) is a self-report questionnaire comprising 11 items rated on a five-point Likert scale (1 = Completely disagree, 2= Disagree, 3 = Neither agree nor disagree, 4 = Agree, 5 = Completely agree). The SMRL assesses the acceptance of the following myths of romantic love: omnipotence (item 1), half orange (items 2 and 3), need for a couple (item 4), eternal passion (item 5), exclusiveness (item 6), marriage (item 7), abnegation (items 8 and 9), jealousy (item 10), and ambivalence (item 11). In terms of construct validity, the SMRL is comprised of a two-factor correlated internal structure: Idealized Love (Factor 1. IL) and Distorted Love (Factor 2. DL). Moreover, according to the original authors, the SMRL also allows for the assessment through the total score on the scale. With regard to validity and reliability, the goodness of the fit indices tested (RMSEA, SRMR, GFI, AGFI, CFI, and AIC) were excellent. The internal consistency of SMRL is acceptable according to cutoff criteria (George and Mallery 2018), as Cronbach’s alpha (α = 0.73) is higher than 0.70.

Sociodemographic variables. Age, sex, and gender data were also collected.

2.3. Procedure

Data were self-reported and collected via the SurveyMonkey online platform (SurveyMonkey Inc. n.d.). Permission for translation and adaptation of the instrument into Portuguese was first obtained from the original authors. The SMRL adaptation process followed a back-translation procedure, consistent with established guidelines for the translation and adaptation of psychological assessments (Hambleton and De Jong 2003; International Test Commission [ITC] 2017). In the first step, a native Portuguese-speaking translator translated the original Spanish version of the SMRL into Portuguese. Subsequently, a second translator, fluent in both languages, back-translated the Portuguese version into Spanish. The research team then compared the original Spanish version with the back-translated version to ensure both semantic and conceptual equivalence.

2.4. Data Analysis

Data analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics v. 29 (IBM Corporation 2023a) and IBM SPSS AMOS v. 29 (IBM Corporation 2023b). SPSS Statistics was employed to assess the normality of the data distribution, examine descriptive statistics for the items, and conduct confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). The CFA was used to evaluate the two-factor correlated model proposed by the original authors. Based on the original validation of the SMRL, where the two factors were allowed to correlate (Bonilla-Algovia and Rivas-Rivero 2020), the CFA was performed using oblimin oblique rotation with Kaiser normalization, applying both maximum likelihood and robust estimation methods. To assess internal consistency, both Cronbach’s alpha and McDonald’s omega were computed, as McNeish (2018) highlighted the limitations of Cronbach’s alpha. Additionally, independent group comparisons were conducted using the Mann–Whitney U test to examine potential gender differences in both factors of SMRL. AMOS Statistics was used to determine the goodness-of-fit of the obtained model. Additionally, the one-factor and the two-factor uncorrelated models were also tested, in the same way as the original SMRL validation. The following goodness-of-fit indices were considered: the normed Chi-square statistic (CMIN/df), the Jöreskog–Sörbom Goodness of Fit Index (GFI), the Steiger–Lind Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), the Parsimonious Normed Fit Index (PNFI), the Parsimony ratio (PRATIO), and the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC). Values of the CMIN/df index between 2 and 3 are indicative of an acceptable model fit (Kline 2023). Values of the GFI higher than 0.90 imply acceptable fit (Bentler 1990; Hu and Bentler 1999). RMSEA values lower than 0.10 are considered indicative of acceptable fit (Marcoulides and Yuan 2017) and reasonable error (MacCallum et al. 1996). Values of PNFI and PRATIO higher than 0.50 are indicative of good parsimony of the model (Mulaik et al. 1989). Also, the AIC allows to select the best model in terms of both parsimony and fit adequacy of the data (Akaike 1974), as the model with the lowest AIC value is considered the best (Brown 2015).

2.5. Ethical Approval

This research obtained ethical approval from the Ramon Llull University Ethical Committee (Code 2122013D, 31 May 2022).

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Analysis of Items

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics for the items of the EMAR scale. As for the endorsement of myths of romantic love, the omnipotence (item 1, 58%), abnegation (item 9, 50%), exclusiveness (item 6, 44%), and half orange (item 3, 42%) myths were the most accepted by Portuguese youth and emerging adults. In contrast, item 11, which assesses the ambivalence love myth, presented the lowest endorsement. Similar mean values were observed across the rest of the items. Notably, items 4 and 11 exhibited higher levels of skewness compared to the other items within the same factor. Consistently, the kurtosis values for these two items were significantly lower than those for the remaining items. The sample-to-item ratio was 15:1, which is considered excellent (Kline 2023; Schumacker and Lomax 2015).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of EMAR items.

3.2. Internal Structure

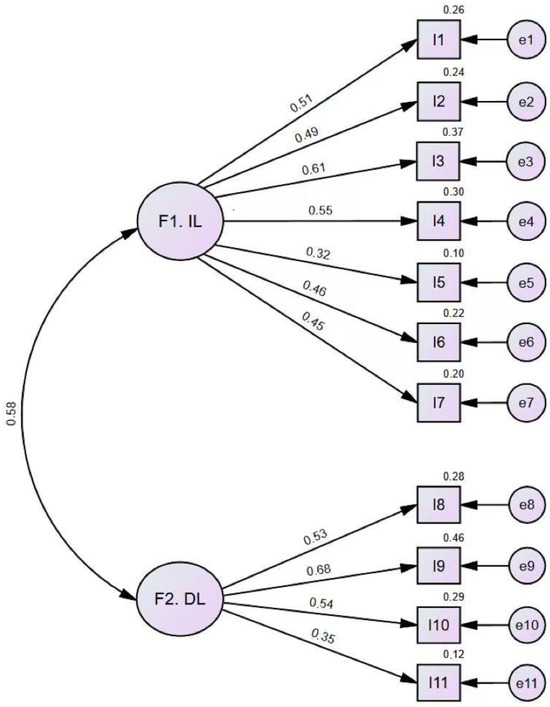

The factor loadings are presented in Table 2. Items 1 to 7 loaded onto the first factor, Idealized Love (IL), while items 8 to 11 loaded onto the second factor, Distorted Love (DL). The standardized factor loadings for the IL factor ranged from 0.330 to 0.742, and for the DL factor, they ranged from 0.318 to 0.665 (see Table 2). Communalities ranged from 0.170 to 0.682, indicating a moderate to strong level of variance explained by the factors for the majority of the items.

Table 2.

Factor loadings and communalities from the CFA of EMAR.

Thus, the CFA outcomes supported the two-factor correlated structure proposed by the original validation (Bonilla-Algovia and Rivas-Rivero 2020), with a 41.50% explained variance. The fit of three models was tested (see Table 3). Models 2 and 3 showed a poor fit, with unsatisfactory goodness-of-fit indices. Therefore, Model 1 (see Figure 1) obtained an adequate fit according to cutoff values (χ2(43) = 90.747, p < 0.001, χ2/df = 2.110, GFI = 0.907, RMSEA = 0.082, PNFI = 0.552, PRATIO = 0.782). Also, the AIC index suggested that Model 1 was the best (Δχ2 = −22.78; Δdf = −1; Δχ2/df = −0.47; ΔAIC = −20.78). The two EMAR factors correlated positively and statistically significantly (r = 0.383***; R2 = 0.147), which reinforced the maximum likelihood extraction method applied.

Table 3.

Goodness-of-fit indices of the tested models.

Figure 1.

Standardized estimates of the EMAR items obtained in the confirmatory factor model. Note. F1 = Idealized Love (IL); F2 = Distorted Love (DL).

3.3. Internal Consistency

Internal consistency was assessed using reliability coefficients and item-factor correlations (see Table 4). The results of the Cronbach’s alpha and McDonald’s omega analyses indicated acceptable internal consistency (α = 0.728; ω = 0.711) (George and Mallery 2018). Additionally, item analyses revealed that all items contributed to the internal consistency of both factors, as the removal of none of them resulted in an increase in reliability. Item-factor correlations were statistically significant, with values approaching 0.5, further supporting the adequacy of internal consistency based on both reliability coefficients and item-factor correlations.

Table 4.

Item-factor Spearman’s correlations.

3.4. Between-Group Gender Differences in Myths of Romantic Love

Regarding the comparison between females and males (see Table 5), the Mann–Whitney U test indicated no significant differences (p > 0.05) for the Idealized Love (IL) or Distorted Love (DL) factors. However, item-level analyses revealed statistically significant differences for items 2, 4, and 11 between females and males (p < 0.05). Specifically, item 2 had significantly higher results for the female group, indicating greater acceptance of the half orange myth (38% vs. 21%). In contrast, the need for a couple (15% vs. 21%) and ambivalence (7% vs. 14%) myths had significantly higher results for the male group. Rank-biserial correlation (Cohen 1992) indicated a medium effect size (rb ≈ 0.3) for the obtained between-group differences.

Table 5.

Between-group Mann–Whitney U test comparison by gender (N = 165).

4. Discussion

This research analyzed the psychometric properties of the Portuguese version of the Scale of Myths of Romantic Love (SMRL) in a Portuguese sample of youth and emerging adults. Moreover, it aimed to explore the endorsement of myths of romantic love.

First, our findings generally support our methodological research hypothesis, as confirmatory factor analyses supported the two-factor correlated structure of the original test (Bonilla-Algovia and Rivas-Rivero 2020). Thus, the EMAR is comprised of two factors: Idealized Love (F1. IL) and Distorted Love (F2. DL). The findings indicated adequate item properties and internal consistency.

Second, the results of this study have suggested that the myths of romantic love are quite frequent among the Portuguese youth population. Specifically, the omnipotence, half orange, exclusiveness, and abnegation myths presented scores above the middle point of the Likert Scale, indicating a tendency towards agreement and acceptance. These results are in line with recent studies obtained in the Spanish context (Bonilla-Algovia and Rivas-Rivero 2020; Bonilla-Algovia et al. 2024).

Third, as for gender differences, this research has suggested potential differences between males and females in the half orange (item 2), need for a couple (item 4), and ambivalence (item 11) myths. As can be seen in Table 5, a statistically significant greater acceptance of the half orange myth was reported by the female group, whereas the male group obtained significantly higher scores in the need for a couple and ambivalence romantic love myths (p < 0.05). These outcomes contradict previous research that has obtained similar perceptions between both genders (Cubells-Serra et al. 2021; Ferrer et al. 2010). This discrepancy may be attributed to several factors: sample size, age range (e.g., 18–70 y.o., Cubells-Serra et al. 2021; 18–93 y.o., Ferrer et al. 2010), and/or potential cultural differences in love interpretation (Karandashev 2017), as both studies included Hispanic samples. Along these lines, previous cross-cultural studies on romantic love found that love models vary more between cultures than between genders (De Munck et al. 2009; Nelson and Yon 2019). Nelson and Yon (2019) found some exceptions to this pattern, as they identified some gendered patterns in responses across different cultures, predominantly in the negative or irrational aspects of romantic love. A plausible hypothesis to explain this contradiction is that the adult population shows greater acceptance of romantic love myths compared to the young adult population. In this sense, a recent study conducted in Portugal (Cipriano et al. 2021) demonstrated that traditional gender stereotypes (such as the association of strength with men and nurturing and passivity with women) are more strongly accepted by older individuals and women. Therefore, it is hypothesized that certain stereotypes (e.g., the expectation of women being caring and passive) could be linked to the abnegation myth of romantic love, which involves prioritizing a partner’s needs over one’s own. Furthermore, the stereotypical view of men as strong and dominant can be associated with the myth of ambivalence, often reflected in aggressive behaviors like shouting or insults. Also, controlling behaviors are stereotypically linked to men, which could be related to the myth of jealousy. These hypotheses suggest an interrelation between gender stereotypes and myths of romantic love, implying that certain gendered expectations may influence the way love is perceived in the context of partner selection.

4.1. Strengths

It is noteworthy that the translation and back-translation process adhered to the guidelines of the International Test Commission [ITC] (2017). Moreover, the sample in the present study exhibited the same age range, mean age, and gender distribution as those in the original validation, ensuring the reproducibility of the original study and maintaining the same sample characteristics. Additionally, the reliability results and model fit indices for the bi-factorial model are similar to those obtained in the original study. For example, in this study, the obtained Cronbach’s alpha (α = 0.728) is nearly the same value as the original validation (α = 0.73; Bonilla-Algovia and Rivas-Rivero 2020). These similarities indicate consistency in our psychometric findings.

4.2. Limitations and Future Directions

This study is not without limitations. Despite the excellent person-to-item ratio (Schumacker and Lomax 2015), it is noteworthy that the sample size obtained is not large enough to generalize the gender between-group differences found in the population of young and young-adult people in Portugal. Thus, the sample size and gender distribution limit the generalizability of our between-group gender comparison findings. Additionally, the snowball sampling method involves a potential selection bias (Parker et al. 2019). Thus, to expand the generalizability of future studies, it is recommended to use randomly selected samples from a cross-section of Portuguese youth and young adults. On the other hand, based on the premise that romantic love exists across the human lifespan in both sexes (Bode and Kushnick 2021), as far as we know, there is no extensive literature on myths of romantic love across generations. Therefore, future research involving a broader age range is needed to analyze potential differences in the representation of love across adolescent, adult, and older age groups, while also further examining the intersectionality of age and gender in relation to gender stereotypes and myths of love. From a statistical perspective, a notable limitation is the absence of concurrent validity analysis, as there is no other validated psychometric measure in Portuguese that assesses the same construct nor another construct that could be considered a gold standard. However, the lack of validated instruments for concurrent validity is a common methodological issue in the field of psychometric instrument development and adaptation (DeVellis and Thorpe 2021).

Future research could benefit from the EMAR Portuguese validation and use it as a measure of concurrent or convergent external validity in the development of alternative psychometric tools for assessing perceptions of romantic love and related myths. Furthermore, to investigate the relationship between the acceptance of romantic love myths and violence, future studies could adopt a longitudinal design to explore the predictive capacity of romantic love myths on violence perpetrated and/or suffered in young populations. Also, this scale could be valuable for the assessment of myths of romantic love endorsement across different cultures. In this regard, it could be hypothesized that countries with less idealized and distorted attitudes towards love will present less interpersonal violence.

Additionally, given the significant impact and detrimental effects of gender stereotypes on women (Banchefsky and Park 2018), future research should focus on examining the connections between specific gender stereotypes and myths of romantic love. Finally, additional relevant variables, such as love perception and relationship quality (consensus, satisfaction, cohesion, and affective expression), could be analyzed in conjunction with myths of romantic love using Sternberg’s Triangular Love Scale (STLS; Cassepp-Borges and Pasquali 2012) or the Love Attitudes Scale, Short Form (LAS-SF; Neto and Pinto 2025) and the Dyadic Adjustment Scale (DAS; Gomez and Leal 2008).

5. Conclusions

Overall, the results show that the Portuguese version of the SMRL (Escala de Mitos do Amor Romântico, EMAR, see Appendix A) is an appropriate instrument for evaluating perceptions of love, demonstrating robust psychometric properties. One of the main benefits of offering the Portuguese-language version of the SMRL test is that it enhances the ability to make comparisons across different samples and ensures future reproducibility of these findings.

Also, from a primary prevention perspective, due to the beliefs that shape romantic love myths increasing the acceptance of behaviors that would typically be considered abusive in a relationship (Lelaurain et al. 2021), the EMAR can be very useful for early detection of myths that may lead to dating violence and IPV. In fact, a recent longitudinal study (Neves et al. 2021) has demonstrated that traditional marital beliefs in adolescence are predictors of dating violence in young adulthood. Therefore, the relationship between romantic love myths and violence appears to be an emerging field of study in the Portuguese context.

To sum up, the assessment of romantic love myths is crucial to recognizing their contribution to the dynamics, communication, and conflicts emerging in intimate relationships. We hope that this study will serve as a psychometric foundation for future research on the myths of romantic love within the Portuguese context, contributing to the generation of essential knowledge on this dyadic phenomenon.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.G.-M. and B.V.; data collection, S.C.-R. and J.G.-M.; methodology and validation, J.G.-M.; writing—original draft preparation: J.G.-M., S.C.-R., B.V. and C.P.-T.; writing—review and editing, J.G.-M., S.C.-R., B.V. and C.P.-T.; supervision: C.P.-T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the European Union and the Catalan Agency for Research (AGAUR) (Grant number: 2024FI-300920).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Ramon Llull University (Code 2122013D, 31 May 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study and all participants were informed about the study objectives, design, and publishing actions.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in the research are not available. Data cannot be publicly shared due to privacy and ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to Beatriz Gómez Gutiérrez and Gustavo Lobo Redondeiro for their invaluable involvement in the translation and back-translation process of the instrument.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| EMAR | Escala de Mitos do Amor Romântico |

| SMRL | Scale of Myths of Romantic Love |

| IL | Idealized Love |

| DL | Distorted Love |

| IPV | Intimate Partner Violence |

| GbV | Gender-based Violence |

| ITC | International Test Commission |

| CFA | Confirmatory Factor Analysis |

| GFI | Jöreskog–Sörbom Goodness of Fit Index |

| RMSEA | Steiger-Lind Root Mean Square Error of Approximation |

| PNFI | Parsimonious Normed Fit Index |

| PRATIO | Parsimony ratio |

| AIC | Akaike Information Criterion |

Appendix A

Escala de Mitos do Amor Romântico (EMAR, Grané-Morcillo et al. 2025)

A seguir vai encontrar uma série de afirmações sobre o amor. Indique até que ponto concorda ou discorda de cada uma das seguintes afirmações.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Note. Escala de Likert: 1 = Discordo totalmente, 2 = Discordo, 3 = Nem concordo nem discordo, 4 = Concordo, 5 = Concordo plenamente. |

References

- Akaike, Hirotugu. 1974. A new look at the statistical model identification. IEEE Transactions on Automatic Control 19: 716–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldry, Anna C., and Stefano Pagliaro. 2014. Helping victims of intimate partner violence: The influence of group norms among lay people and the police. Psychology of Violence 4: 334–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banchefsky, Sarah, and Bernadette Park. 2018. Negative gender ideologies and gender-science stereotypes are more pervasive in male-dominated academic disciplines. Social Sciences 7: 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentler, Peter M. 1990. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin 107: 238–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidney, David. 1967. Theoretical Anthropology. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bode, Adam, and Geoff Kushnick. 2021. Proximate and ultimate perspectives on romantic love. Frontiers in Psychology 12: 573123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonilla-Algovia, Enrique, and Esther Rivas-Rivero. 2018. Mitos del amor romántico en una muestra de futuros y futuras docentes [Myths of romantic love in a sample of future teachers]. Revista de Estudios e Investigación en Psicología y Educación 5: 113–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonilla-Algovia, Enrique, and Esther Rivas-Rivero. 2020. Diseño y validación de la escala de mitos del amor romántico [Design and validation of the scale of myths of romantic love]. Revista Iberoamericana de Diagnóstico y Evaluación-e Avaliação Psicológica 4: 119–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonilla-Algovia, Enrique, Concepción Carrasco, Esther Rivas-Rivero, and Eva Izquierdo-Sotorrío. 2024. The scale of myths of romantic love: Psychometric properties and gender differences in Spanish adolescents. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 41: 1533–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch, Esperanza, Victoria Ferrer, Esther García, María Ramis, María C. Mas, Capilla Navarro, and Gabrial Torrens. 2007. Del Mito del Amor Romántico a la Violencia Contra las Mujeres en la Pareja [From the Myth of Romantic Love to Violence Against Women]. Ministry of Equality. Available online: https://www.inmujeres.gob.es/publicacioneselectronicas/documentacion/Documentos/DE0055.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- Brown, Timothy A. 2015. Confirmatory Factor Analysis for Applied Research, 2nd ed. New York: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cassepp-Borges, Vicente, and Luiz Pasquali. 2012. Sternberg’s Triangular Love Scale national study of psychometric attributes. Paidéia (Ribeirão Preto) 22: 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cava, María J., Belén Martínez-Ferrer, Sofia Buelga, and Laura Carrascosa. 2020. Sexist attitudes, romantic myths, and offline dating violence as predictors of cyber dating violence perpetration in adolescents. Computers in Human Behavior 111: 106449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipriano, Margarida, André R. Vaz, Joan Rolho, Ana S. Santos, and Paula Carneiro. 2021. Behavior as a stereotype cue: An European Portuguese pretest on age and gender stereotypes. Análise Psicológica 39: 133–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Jacob. 1992. A power primer. Psychological Bulletin 112: 155–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cubells-Serra, Jenny, Alejandro Sánchez-Sicilia, Priscila Astudillo-Mendoza, Neli Escandón-Nagel, and María J. Baeza-Rivera. 2021. Assumption of the myths of romantic love: Its relationship with sex, type of sex-affective relationship, and sexual orientation. Frontiers in Sociology 6: 621646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Munck, Victor, Andrey Korotayev, and Darya Khaltourina. 2009. A comparative study of the structure of love in the US and Russia: Finding a common core of characteristics and national and gender differences. Ethnology: An International Journal of Cultural and Social Anthropology 48: 337–57. [Google Scholar]

- DeVellis, Robert F., and Carolyn T. Thorpe. 2021. Scale Development: Theory and Applications. New York: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández, Irene, José J. Navarro-Pérez, Ángela Carbonell, and Amparo Oliver. 2023. Psychometric properties on a romantic love myths scale: The case of the myths, fallacies, and erroneous beliefs about the ideal of romantic love scale. Current Psychology 42: 1665–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer, Victoria A., Esperanza Bosch, and Capilla Navarro. 2010. Los mitos románticos en España [Romantic myths in Spain]. Boletín de Psicología 99: 7–31. [Google Scholar]

- FRA, EIGE, and Eurostat. 2024. EU Gender-Based Violence Survey—Key Results. Experiences of Women in the EU-27. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. [Google Scholar]

- George, Darren, and Paul Mallery. 2018. Reliability analysis. In IBM SPSS Statistics 25 Step by Step. New York: Routledge, pp. 249–60. [Google Scholar]

- Giddens, Anthony. 1992. The transformation of intimacy: Sexuality, love and eroticism in modern societies. New York: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Goenaga, María. 2021. Creencias acerca de los mitos del amor romántico entre el alumnado de Comunicación Audiovisual de la Universidad Complutense de Madrid [Beliefs about the Myths of Romantic Love among Audiovisual Communication Students at the Complutense University of Madrid]. Madrid: Universidad Complutense de Madrid. [Google Scholar]

- Gomez, Rita, and Isabel Leal. 2008. Ajustamento conjugal: Características psicométricas da versão portuguesa da Dyadic Adjustment Scale. Análise Psicológica 26: 625–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Goodman, Leo A. 1961. Snowball sampling. The Annals of Mathematical Statistics 32: 148–70. [Google Scholar]

- Hambleton, Ronald K., and John H. De Jong. 2003. Advances in translating and adapting educational and psychological tests. Language Testing 20: 127–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hester, Marianne, Catherine Donovan, and Eldin Fahmy. 2010. Feminist epistemology and the politics of method: Surveying same sex domestic violence. International Journal of Social Research Methodology 13: 251–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Li-Tze, and Peter M. Bentler. 1999. Cutoff criteria for the indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling 6: 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBM Corporation. 2023a. IBM SPSS Statistics for Mac. Version 29.0.1.0. Armonk: IBM Corp. [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corporation. 2023b. IBM AMOS Statistics for Microsoft. Version 29.0.1.0. Armonk: IBM Corp. [Google Scholar]

- International Test Commission. 2017. The ITC Guidelines for Translating and Adapting Tests, 2nd ed. England: ITC. Available online: https://www.intestcom.org/files/guideline_test_adaptation_2ed.pdf (accessed on 11 December 2023).

- Jiménez-Picón, Nerea, Macarena Romero-Martín, Rocío Romero-Castillo, Juan C. Palomo-Lara, and Miriam Alonso-Ruíz. 2022. Internalization of the romantic love myths as a risk factor for gender violence: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sexuality Research and Social Policy 20: 837–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karandashev, Victor. 2017. Romantic Love in Cultural Contexts. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, Rex B. 2023. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 5th ed. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lelaurain, Solveig, David Fonte, Jean-Christophe Giger, Séverin Guignard, and Grégory Lo Monaco. 2021. Legitimizing intimate partner violence: The role of romantic love and the mediating effect of patriarchal ideologies. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 36: 6351–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linares, Rocío, María Aranda, Marta García-Domingo, Teresa Amezcua, Virginia Fuentes, and María Moreno-Padilla. 2021. Cyber-dating abuse in young adult couples: Relations with sexist attitudes and violence justification, smartphone usage, and impulsivity. PLoS ONE 16: e0253180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacCallum, Robert C., Michael W. Browne, and Hazuki M. Sugawara. 1996. Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychological Methods 1: 130–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcoulides, Katerina A., and Ke-Hai Yuan. 2017. New ways to evaluate goodness of fit: A note on using equivalence testing to assess structural equation models. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal 24: 148–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeish, Daniel. 2018. Thanks coefficient alpha, we’ll take it from here. Psychological Methods 23: 412–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulaik, Stanley A., Larry R. James, Judith Van Alstine, Nathan Bennett, Sherri Lind, and Charles D. Stilwell. 1989. Evaluation of goodness-of-fit indices for structural equation models. Psychological Bulletin 105: 430–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, Alex J., and Kyu Jin Yon. 2019. Core and peripheral features of the cross-cultural model of romantic love. Cross-Cultural Research 53: 447–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, Félix, and Maria da Conceição Pinto. 2025. Correlates of the Short Form Love Attitudes Scale among Portuguese People. Sexuality & Culture 29: 152–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, Dulce. 2016. Normas face ao género e à diversidade sexual. Mudanças inacabadas nos discursos juvenis [Gender and sexual diversity norms. Unfinished changes in youth discourses]. Sociologia, Problemas e Práticas 2: 89–102. [Google Scholar]

- Neves, Sofia, and Conceição Nogueira. 2010. Deconstructing gendered discourses of love, power, and violence in intimate relationships. In Silencing the Self Across Cultures: Depression and Gender in the Social World. Edited by Dana C. Jack and Ali A. Lisbon: University Press, pp. 241–61. [Google Scholar]

- Neves, Sofia, Miguel Cameira, and Sónia Caridade. 2021. Beliefs on marital violence among Portuguese adolescents: Monitoring their evolution and relationship with dating violence. Violence and Victims 36: 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papp, Leanna J., Miriam Liss, Mindy J. Erchull, Hester Godfrey, and Lauren Waaland-Kreutzer. 2017. The dark side of heterosexual romance: Endorsement of romantic beliefs relates to intimate partner violence. Sex Roles 76: 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, Charlie, Sam Scott, and Alistair Geddes. 2019. Snowball sampling. In SAGE Research Methods Foundations. Edited by Paul Atkinson, Sara Delamont, Alexandru Cernat, Joseph W. Sakshaug and Richard A. Williams. New York: Sage Publications, pp. 161–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perista, Heloísa, Ana Cardoso, Mário Silva, and Paula Carrilho. 2012. Delinquencia e Violencia Juvenil em Portugal. Tracando um Retrato a Diferentes Vozes [Juvenile Delinquency and Violence in Portugal: Drawing a Portrait at Different Voices]. São Domingos de Rana: Centro de Estudos para a Intervencao Social. Available online: http://www.youprev.eu/pdf/YouPrev_NationalReport_PT.pdf (accessed on 19 December 2024).

- Rivas-Rivero, Esther, and Enrique Bonilla-Algovia. 2021. Relación entre los mitos románticos y las actitudes hacia la igualdad de género en la adolescencia [Relationship between romantic myths and attitudes towards gender equality in adolescence]. Psychology, Society and Education 13: 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacker, Randall E., and Richard G. Lomax. 2015. A Beginner’s Guide to Structural Equation Modeling, 4th ed. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Shynkaruk, Vasyl, Halyna Salata, and Tetyana Danylova. 2018. Myth as a phenomenon of culture. Вісник Націoнальнoї академії керівних кадрів культури і мистецтв 1: 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Standley, Jeff. 2022. Lessons in love: Countering student belief in romantic love myths. Journal of Philosophy of Education 56: 739–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sternberg, Robert J. 1986. A triangular theory of love. Psychological Review 93: 119–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SurveyMonkey Inc. n.d. SurveyMonkey Platform; San Mateo: SurveyMonkey Inc. Available online: www.surveymonkey.com (accessed on 17 January 2024).

- Triano, Patricia, Elena Morales-Marente, and María S. Palacios-Gálvez. 2021. Tolerancia hacia el ciberacoso en el noviazgo: Analizando su relación con la violencia de género [Tolerance towards cyberbullying in dating: Analysing its relationship with gender-based violence]. Health and Addictions/Salud y Drogas 21: 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- União de Mulheres Alternativa e Resposta. 2024. ARTEMIS: Estudo Nacional Sobre Violência no Namoro [ARTEMIS: National Study on Dating Violence]. Lisbon: UMAR. [Google Scholar]

- Yela, Carlos. 2003. La otra cara del amor: Mitos, paradojas y problemas [The other face of love: Myths, paradoxes and problems]. Encuentros en Psicología Social 1: 263–67. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).