Abstract

Although maintaining social cohesion between refugees and host communities is a major policy goal, due to protracted refugee situations, research on potential barriers is scant, particularly in low- and middle-income countries where a majority of the world’s refugees live. This article provides insights into food insecurity as a barrier to refugee–host community social cohesion in the wake of food aid cuts to refugees globally. We conducted 24 focus group discussions, 3 in-depth interviews, and 8 key informant interviews with refugee and host community members, local leaders, and staff of entities overseeing refugee affairs in two settlements in Southwestern Uganda. We found that refugees experiencing food insecurity and limited coping resources resort to negative and socially unacceptable means, such as theft and aggression, to obtain food. This causes social tensions and social fragmentation that directly contribute to the deterioration of social cohesion by undermining trust, inhibiting cooperation, and weakening the sense of shared purpose between refugees and their host communities. Food insecurity is a significant threat to the social integration of refugees, as it weakens their social connections in the host community. Measures to address food insecurity among refugees are imperative to mitigate its potential deleterious effects on the social integration of refugees in protracted situations.

1. Introduction

The global refugee population reached 36.4 million by mid-2023 (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) 2023). The majority of the world’s refugees live in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) (UNHCR 2023). Africa contributes approximately 19% of the global refugee population (Africa Centre for Strategic Studies 2024), with the majority being hosted in Uganda. As of May 2024, Uganda was home to over 1.6 million refugees and asylum seekers, mainly from South Sudan and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), and more recently Sudan (UNHCR 2024a). Like other LMICs, Uganda grapples with a protracted refugee situation (Dryden-Peterson and Hovil 2004; Kamugisha et al. 2024) due to its contiguity with fragile states such as South Sudan and the DRC. New arrivals continue to enter the country, while several resettled refugees have stayed in Uganda for lengthy periods of 20 years or more (UNHCR 2024a) because it is still unsafe for them to return home (De Berry and Roberts 2018).

Refugees in Uganda interact frequently with their host communities. Over 80% of refugees live in rural villages known as settlements alongside their hosts (UNHCR 2022). In addition, several refugees live in urban areas, particularly Kampala, which hosts around 106,143 (6%) of the total refugee population in Uganda (UNHCR 2024a). The progressive refugee policy that grants refugees in Uganda freedom of movement, a right to work, and unrestricted access to public resources and services (Betts et al. 2022; Nambuya et al. 2018; Khasalamwa-Mwandha 2021; d’Errico et al. 2024) further increases opportunities for social contact between refugee and host populations. Regular social contact between refugees and host communities can spark tensions between the two populations (Betts et al. 2022). In LMICs, the main sources of tensions usually include increased pressure on resources and basic services by refugees (Guay 2015; Jayakody et al. 2022), competition for scarce livelihood or natural resources (Ali et al. 2017; Smith et al. 2021; Emmanuel 2020), and fears of labor market competition (Guay 2015; Oucho and Williams 2019; Betts et al. 2022). Such tensions are inimical to the social integration and protection of refugees, necessitating proactive measures to foster social cohesion and peaceful co-existence between refugees and host communities (Seyidov 2021; Betts et al. 2022; International Organization for Migration (IOM) 2024). Successful promotion of social cohesion between refugee and host communities requires an in-depth understanding of possible barriers so that targeted interventions can be designed to mitigate them (Jayakody et al. 2022; Betts et al. 2022).

The extant literature identifies several barriers to social cohesion among refugee and host communities. A study among host communities in Turkey found that language barriers, cultural distance, and bias against refugees contributed to weakening social cohesion between the two populations (Seyidov 2021). In the United Kingdom, differences in culture and faith, prejudice, and limited opportunities for intergroup contact were identified as key barriers to social cohesion among refugee and host communities (Daley 2009). Limited opportunities for intergroup contact were also identified as a barrier to social cohesion among encamped refugees and the surrounding host communities in Tanzania (Sturridge et al. 2023). In Kenya, significant deterioration in social cohesion among refugee and host populations was attributed to increased criminal activity among refugees, which escalated stigma and intolerance towards them from the nationals (Oucho and Williams 2019).

In LMICs, such deleterious criminal activity among refugees could be exacerbated by food insecurity emanating from dwindling humanitarian aid and support at the international level (UNHCR 2024a). In most LMICs, refugees primarily depend on humanitarian aid for survival, even when in protracted situations (Manirambona et al. 2021; Gupta et al. 2024). For instance, until recently, all refugees in Uganda were receiving general food assistance in cash or in-kind from the World Food Program (WFP 2020). However, the WFP has had to prioritize food assistance to refugees in response to shortfalls in funding (WFP 2023a), leaving several households with little or no food rations. The prioritization of generalized food assistance for refugees in Uganda has been implemented in three phases. In the first phase, a geographical approach was used where refugees in the most food-insecure regions of Uganda (group 1) saw their rations reduced to 70%, and those in moderately vulnerable locations (group 2) received 60%, while the least vulnerable category (group 3) received 40% of the full ration. In phase 2 of the prioritization, 25% of the most vulnerable refugees living in the settlements in geographical category 3, described above, were identified, and their rations increased from 40% to 60% (Stein et al. 2022). In July 2023, the third phase of prioritization recategorized the refugees according to individual household vulnerability profiles. Refugees categorized as highly and moderately vulnerable received 60% and 30% of the full ration, respectively, while those considered least vulnerable were weaned off food assistance (WFP et al. 2023). The prioritization has complicated access to food and other basic necessities for several refugee households in Uganda (Brown and Torre 2024; Gupta et al. 2024; Guyson 2024). This increased vulnerability may heighten refugees’ risk of resorting to socially unacceptable measures such as engagement in criminal activity for survival, as it is not uncommon for economically distressed individuals to turn to crime as a desperate measure to obtain food and other basic necessities (Deschak et al. 2022).

In Jordan, poverty, pressures on public services, and negative media coverage of refugees were identified as key sources of tensions that were detrimental to social cohesion among nationals and Syrian refugees in the country (Guay 2015). In Uganda, Betts et al. (2022) reported strained host–refugee relationships emanating from refugees’ encroachment on land owned by the host community.

Maintaining social cohesion between refugees and host communities has become a major policy goal at global and national levels in the last decade (Guay 2015; Ozcurumez and Hoxha 2020; Sturridge et al. 2023), as millions of refugees live in protracted situations. However, research on the dynamics of social cohesion among refugees and host communities remains limited. This is particularly the case in LMICs such as Uganda (Fajth et al. 2019; Ozcurumez and Hoxha 2020), even though they host the largest number of refugees in the world.

This article provides insights into potential barriers to social cohesion among refugee and host communities in a low-resource setting. It highlights how food insecurity among refugees can contribute to deterioration in social cohesion between refugees and their host communities. Food insecurity is broadly defined as the limited or uncertain availability of nutritionally adequate, safe foods or the inability to acquire personally acceptable foods in socially acceptable ways (Normeén et al. 2005). The article addresses two research questions: the manifestations of food insecurity among refugee communities in Uganda, and how food insecurity among refugees affects social cohesion between refugees and their surrounding host communities. We argue that food insecurity is a significant threat to the social integration of refugees in protracted situations.

2. Social Cohesion in the Context of Refugees and Their Host Communities

Social cohesion is a contested construct with no universally agreed definition (De Berry and Roberts 2018; Sturridge et al. 2023). The term is broadly used to describe the nature and quality of social relations among members of a given group (intragroup), between members of different groups (intergroup), and between people and the state or other institutions that govern them (World Bank 2022; Holloway and Sturridge 2022; Sturridge et al. 2023). Analytically, social cohesion is described as horizontal when it pertains to relationships among individuals and groups—such as refugees and refugees and their hosts—or vertical, when the relationships of focus are between people and the institutions that govern them (Guay 2015). Overall, the notion of social cohesion is associated with various constitutive elements, including trust, cooperation, harmonious co-existence, tolerance, solidarity, sharing, and a sense of community (Zihnioğlu and Dalkıran 2022; World Bank 2022; Grimalda and Tänzler 2018; Jeannotte 2000).

In the context of forced displacement, the term social cohesion is usually applied to examine the nature and quality of social relations among displaced populations, such as refugees (intragroup social cohesion), and between the displaced and the host communities where they settle (intergroup social cohesion) (World Bank 2022). This article takes a horizontal view of social cohesion (Guay 2015; Holloway and Sturridge 2022), focusing on intergroup social relations between refugees and their host communities. Social cohesion is defined as constituting a sense of shared purpose, trust, and willingness to cooperate between refugee and host community members (World Bank 2022). Therefore, barriers to social cohesion in this case are factors, events, or situations that undermine trust, cooperation, and a sense of shared purpose—which denotes oneness, unity, or solidarity—between refugee and host communities. Accordingly, this article deconstructs the deleterious effects of food insecurity on the development and/or maintenance of trusting and cooperative relationships, as well as a sense of shared purpose between refugees and their hosts. We draw on the concepts of social tensions and social fragmentation to analyze the effects of food insecurity on social cohesion. Social tensions are conceived of as feelings of agitation, discontent, and frustration that often culminate in conflict between refugee and host populations (Artemov et al. 2017). Social fragmentation refers to divisions and weakened connections between refugees and host populations (Jeong and Seol 2022).

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Design, Population, and Setting

This article draws on primary data from a study conducted to examine the status of social cohesion among refugee and host communities participating in the Sustainable Market Inclusive Livelihood Pathways to Self-Reliance (SMILES) project in Uganda. The SMILES Project is a livelihood intervention implemented by a consortium of organizations led by the AVSI Foundation collaborating with the UNHCR, Direct Access Initiative Global LLC (DAI), Innovations for Poverty Action (IPA), Makerere University, Social Work and Social Administration Department, and Renewable Energy, Powering Agriculture and Rural Livelihoods Enhancement (REPARLE). The project targets extremely poor refugee and Ugandan households in the host communities with the aim of increasing their self-reliance and resilience.

An exploratory design was used to gain new insights into the status of social cohesion among targeted refugee and host communities. Exploratory research is used to investigate research questions that have not been studied in depth (Babbie 2010). In this case, the design enabled us to obtain deep insights into the nature and quality of social relationships between refugees and host communities participating in the SMILES project, which have hitherto not been systematically examined. Rooted in interpretivist epistemology and constructivism ontology (Creswell 2009), this study took a qualitative approach. This provided an in-depth appreciation of opportunities for social contact and the facilitators and barriers to social cohesion between refugees and their hosts.

The primary study participants were refugees and Ugandans targeted by the SMILES project. These were residents of Kyaka II and Kyangwali Refugee Settlements and their surrounding host communities. They included adult women and men aged 25 years and above, children and adolescents (aged 15–17 years), youth (aged 18–24 years), and persons with disability (PWDs). In addition, key informants were engaged to tap into their opinions and perspectives on the status of social cohesion between refugees and host communities. These included local leaders in both refugee and host communities and staff of the entities that oversee refugee affairs in the country, that is, the Office of the Prime Minister (OPM) and the UNHCR.

The study sites, Kyaka II and Kyangwali Settlements, are located in the rural districts of Kyegegwa and Kikuube, both of which are situated in Southwestern Uganda. As of May 2024, Kyaka II had a total population of 126,267 refugees and a host population of 551,900 people. On the other hand, the refugee population in Kyangwali Settlement was 137,179, while the host population was estimated at 414,000 (UNHCR 2024a). Both settlements predominantly host refugees of Congolese origin, primarily due to their proximity to the war-torn regions of Eastern DRC. Others include South Sudanese and Burundians. Like in the rest of the country, refugee and host community members in Kyaka II and Kyangwali Settlements interact regularly in schools, markets, churches, health facilities, and at social events—sometimes organized by the OPM and the UNHCR and its implementing partners to promote social cohesion between the two populations (Betts et al. 2022; International Labour Organization (ILO) 2023).

3.2. Sampling

The sample included 24 focus group discussions (FGDs), 3 PWDs, and 8 key informants. The FGDs were conducted in both refugee and host communities of the two settlements. We conducted equal numbers (4) of FGDs per age group and gender across the two sites. The key informants constituted 2 officers from the UNHCR and 2 from the OPM (1 from each settlement) and 4 local leaders, half of whom were from the refugee settlement. See Table 1 for details. The sample was generated on the basis of the principles of data saturation (Guest et al. 2006). All the study participants were purposively selected. The primary participants were selected on the basis of their status (refugee or hosts) and involvement in the SMILES project activities. The selection criterion was maximum variation in terms of gender, age, and disability. It was envisaged that all three variables could present unique dynamics that shape the nature of relationships forged by the respective refugee and host community participants. Therefore, inclusion of participants of different genders, age groups, and disability statuses was aimed at ensuring that any diversity in experiences and views of targeted refugee and host community members were captured. Key informants were selected on the basis of their knowledge of the intricacies of social interactions between refugee and host community members in the study sites. Eligible participants were identified and mobilized with the assistance of the SMILES project field implementation teams and local gatekeepers (Creswell 2009; Bryman 2016).

Table 1.

Details of the study sample.

3.3. Data Collection

Data were collected in May 2024, with the aid of 8 research assistants proficient in the local languages of the target population. Participants were engaged using a combination of three methods: FGDs, in-depth interviews (IDIs), and key informant interviews (KIIs). Primary participants were mainly engaged using FGDs. FGDs were complemented with IDIs to engage the minority population of PWDs that were too few to constitute into a FGD. We conducted FGDs with selected participants from both the settlement and host community. Separate FGDs were held for different age groups and male and female participants. Each FGD consisted of 7–10 participants and lasted an average of 2 h. The FGDs were conducted in the local languages of participants in each study site to enhance question comprehension. For the refugees, several local languages were used to accommodate the diverse ethnic groups. These included Kiswahili, Kinyabwisha, and Alur. The discussions were conducted with the aid of a guide consisting of open-ended questions to enable participants to express their views. Participants were asked to share their opinions about the status of social cohesion between refugee and host communities of Kyaka II and Kyangwali Settlements and associated barriers and facilitators. The discussions were conducted by a moderator assisted by a note taker to ensure that all views and emerging issues were captured. The interactions and debates between participants during the FGDs helped to generate deep insights and a wide range of viewpoints that would be less accessible in individual interviews (Wilkinson 1998). Cognizant that FGDs are particularly liable to social desirability bias, we incorporated several measures to minimize it. Firstly, we followed a clear consenting process to ensure that the participants understood the study purpose and why and how they were selected, as well as what was expected of them during the discussions. We also assured them of confidentiality and anonymity to make them comfortable to share their views freely. We specifically emphasized that their names would not be recorded anywhere and that they would be assigned numbers for identification. In addition, we asked open-ended questions about general trends regarding the nature and quality of their relationships and the associated barriers and facilitators to social cohesion, rather than individualized situations. Ground rules such as respecting each other’s opinions and keeping what is discussed confidential were set and agreed upon before discussions commenced. The research assistants went through a rigorous training on recognizing and managing socially desirable responses. They were encouraged to remain neutral and avoid leading questions throughout the discussions.

Face-to-face IDIs and KIIs were conducted with the 3 PWDs and selected key informants, respectively, using a guide consisting of open-ended questions. The interviews lasted an average of 1 hour. The IDIs were conducted in the local languages of the participants, while KIIs were conducted in a mixture of local languages and English, depending on the preferences of the participant. Both KIIs and IDIs provided us insights into the participants’ perspectives on the nature of social relationships between refugee and host community members and the barriers and facilitators to social cohesion between the two populations. In addition, KIIs provided broader contextual information on refugee–host community relations and barriers and facilitators of social cohesion, which helped to explain observed patterns, as well as triangulate the views of primary participants.

3.4. Data Management and Analysis

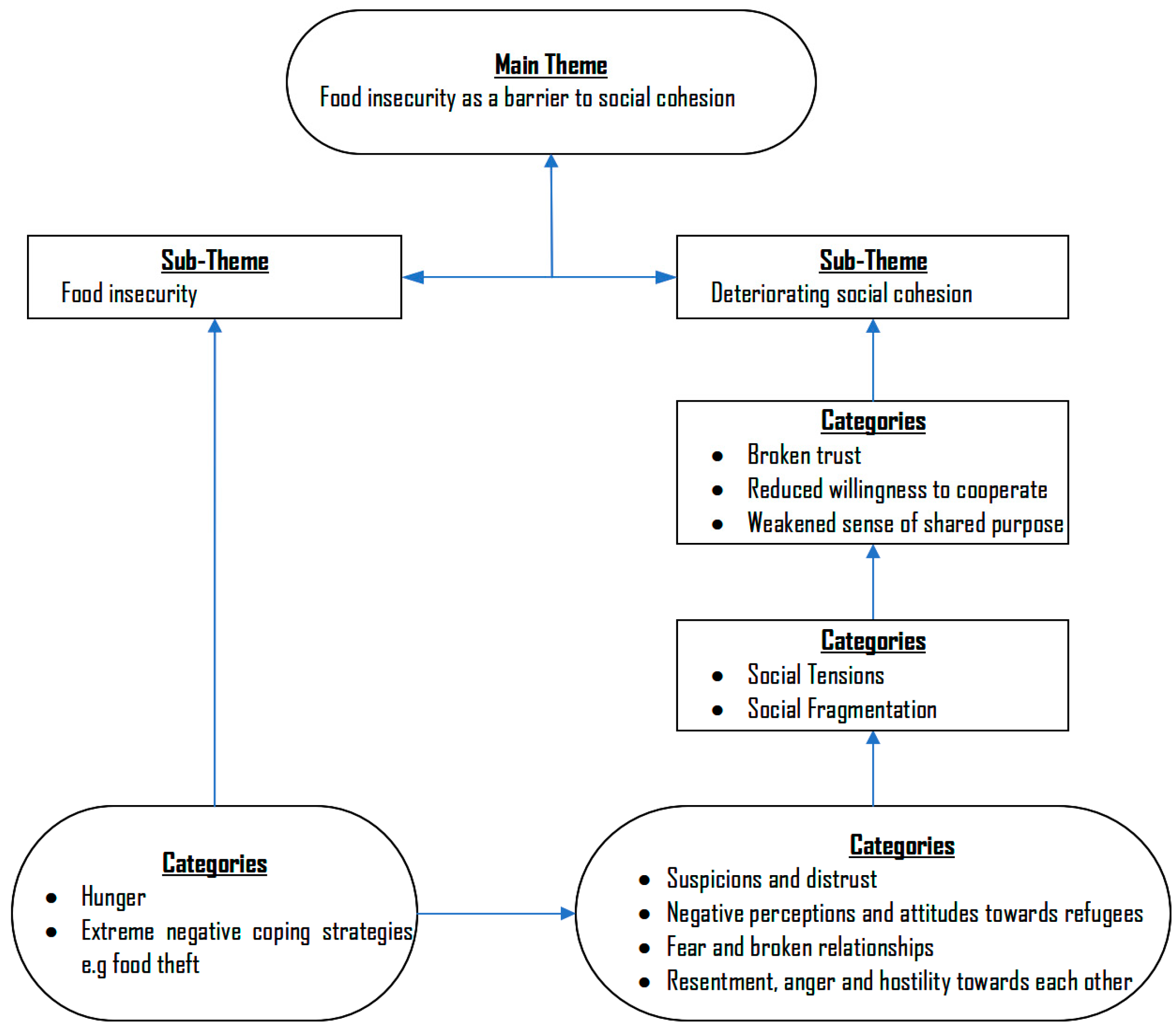

All the discussions and interviews were audio recorded. They were then transcribed verbatim into words and translated into English, where necessary. Transcripts were reviewed alongside the audio recordings to ensure consistency. Each FGD with multiple languages was transcribed by two transcriptionists who spoke all or at least two of the languages used. We checked the consistency of translations into English with the support of the research assistants who moderated the discussions and interpreters working with humanitarian agencies in the two settlements. The reviewed transcripts were imported into NVIVO.12, a Computer-Assisted Qualitative Data Analysis Software for further management. Data analysis was conducted thematically (Braun and Clarke 2006) using the inductive and deductive approach, where the themes and categories emerged from the data and were based on the study objectives and literature on social cohesion, respectively (Vaismoradi et al. 2013). For instance, the theme of food insecurity as a barrier to social cohesion emerged (inductively) from the data, while categories to analyze social cohesion such as trust, willingness to cooperate, and a sense of shared purpose were derived (deductively) from literature on definitions of the concept. The analysis process involved reading and rereading the data as sentences, and paragraphs and whole sections were coded according to the identified themes and categories. This article is based on data from one main theme and two sub-themes, as summarized in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1.

Themes and sub-themes.

Figure 1 shows that food insecurity contributes to deterioration in social cohesion by undermining initiation and maintenance of trusting relationships, discouraging cooperation, and causing divisions that weaken the sense of shared purpose between refugee and host communities. Food insecurity among refugees manifests in the form of hunger and the use of extreme and socially unacceptable coping mechanisms, such as stealing and aggression to access food (see categories under the sub-theme food insecurity; categories consist of groups of data with similar stories that support a theme). The negative coping mechanisms trigger a myriad of negative social and emotional responses that adversely affect refugee–host interactions and relationships. These include suspicions and distrust, fear and broken relationships, negative perceptions and attitudes—including prejudice and bias—toward refugees, and anger, resentment, and hostility towards each other. The negative social and emotional responses interplay to cause social tensions and social fragmentation that break the trust of host community members and reduce their willingness to cooperate with refugees, as well as create rifts that weaken the sense of shared purpose and solidarity between refugee and host community members (see categories under the sub-theme deteriorating social cohesion). The deterioration in social cohesion is likely to aggravate food insecurity among refugees given the centrality of social networks from the host community to their everyday survival.

3.5. Ethical Considerations

This study was granted ethical clearance by the Makerere University School of Social Sciences Research Ethics Committee (MUSSS-2023-326) and Uganda National Council for Science and Technology (SS2593ES). Written informed consent was obtained from all adult participants aged 18 years and above. In addition, written informed assent was obtained from minors aged 15–17 years, as well as informed consent from their caregivers. Participant consent was also sought before audio recording the interviews and discussions. Participants who could not write used a thumbprint. The consent process involved a detailed explanation of the study purpose, selection criteria, the potential benefits and risks of participation, their right to voluntary participation and to withdraw from the study at any point, and where they could address any complaints about the study. The fact that their refusal to participate or withdrawal from the study would not in any way affect access to benefits from the SMILES project was emphasized. Study participants were also assured of confidentiality and anonymity.

To ensure confidentiality, as a minimum, effort was made to ensure that the interview environment guaranteed privacy but at the same time did not make the study participants insecure in the presence of the researchers. During the FGDs, participants were assigned numbers. Each participant would first mention their number, then make a submission. Besides, participants were discouraged from mentioning specific names when they wanted to give examples from the community. In addition, interview and discussion transcripts were stored on computers with passwords to restrict access to only the members of the research team. The audio interviews were destroyed after transcription.

To ensure anonymity, this article excludes individual names and any identifying details of the participants. Utmost objectivity in the analysis and reporting of the findings was ensured. The authors are neither refugees nor host community members; the presented data are views of refugee and host community members who participated in the study. Overall, the research ethics principles of equity, beneficence, confidentiality, and justice were applied in the study.

4. Results

In the subsequent sections, we present data on the manifestations of food insecurity among refugees in the two settlements and their effects on the social relationships and social cohesion between refugees and their surrounding host communities.

4.1. Food Insecurity Among Refugees in Kyaka II and Kyangwali Settlements

Reports of study participants show that several refugees were experiencing food insecurity, defined as the limited or uncertain availability of nutritionally adequate, safe foods, or the inability to acquire personally acceptable foods in socially acceptable ways. Limited access to and uncertain availability of food was reflected in the reports of widespread hunger among refugees. Several refugee participants complained about experiencing hunger—going without food due to lack of what to eat. The limited availability of food among refugee populations was primarily associated with cuts in food rations, which had exacerbated their economic vulnerability. Youth and adult male and female refugee household heads who had either been removed from food rations or received only a proportion of the full ration complained about being unable to provide food and other basic necessities for themselves or their families.

This thing [prioritization of food aid] has really affected us. The money is not enough to get basic needs in the house. You cannot buy food, clothing, medicine, sanitary pads and other needs from the 12,000 Uganda shillings (USD 3.2) we receive. It is not enough; we are going through a hard situation. Hunger is too much. Before the reductions we used to afford 3 meals a day but now we have reduced to only one.(FGD with female refugee youth, Kyangwali Settlement)

About food, before [prioritization of food aid] I was okay. We used to receive rice and I also used to buy other things like cooking oil and they would take us for a month. When they changed us to cash, we started receiving 31,000 Uganda shillings (USD 8.4) but it has now been reduced. What I receive is not enough to provide for me and the children… Sometimes we sleep hungry. The children cry that they are hungry and even me the mother, I have nothing to do.(FGD with adult refugee women, Kyaka II Settlement)

I was removed from the food rations. I have suffered a lot since then, I live in deprivation, and hunger is too much. Getting school fees for my children became a problem, getting what to eat became a problem… when they used to give me that money of 31,000 Uganda shillings (USD 8.4) it used to help me survive but these days I am suffering a lot.(FGD with adult refugee males, Kyaka II Settlement)

Some participants also highlighted the role of reduced land for cultivation in compounding the food insecurity of refugee communities in the two settlements. It was reported that the land parcels allocated to refugee households in the two settlements have been reducing over the years due to the influx of new refugees, which had reduced the amount of own grown food to supplement the food aid.

Maybe just to mention, before 2017, Kyaka II [Settlement] had a small population of refugees and they had a big chunk of land. They would do cultivation and have enough food for themselves but from 2017 up to 2021, Kyaka II was in an emergency state receiving Congolese refugees … so, the population increased more than 5 times. Currently we have 125,000 refugees on a fixed land area. We had to reduce the plots [allocated to each refugee household] to accommodate all that number. …That also explains why hunger is a challenge this side.(KII with OPM Staff, Kyaka II Settlement)

The difference between the nationals and us the refugees is hunger [lack of food]. The refugees had somewhere to dig. They had a portion of land they were cultivating but now it [the settlement] is full. The land [portion allocated to each household] was reduced and the refugees have nowhere to cultivate because the land portion is small…(IDI with male refugee PWD, Kyangwali Settlement)

It was further reported that the limited availability of food had compelled several refugees to resort to socially unacceptable practices in a desperate attempt to meet their basic need for food. All participant groups reported incidences of food theft by both children and adult refugees, with the host community bearing the brunt, since they had more land and food compared with the refugee community. Their views show that these incidences are driven by hunger and despair amid limited options.

… the refugees go and steal from the host community, but majority are food thefts and this is attributed to reducing food aid to the refugees. Hunger is striking the refugee community, that is the cause of those food thefts. The most affected area is the host community because for them they have land and food.(KII with OPM Staff, Kyaka II Settlement)

…it is not that they [refugees] always have such bad habits [stealing food]; that anytime they come across your cat they might take it. But there are times they have no food. So, when they [refugee] are walking and maybe did not eat well the previous night, or food was not enough; they may pick your cassava, dog or cat to eat.(FGD with adult women host community, Kyangwali Settlement)

When we don’t have food at home and the children are hungry, they sometimes go and steal from the neighbor, or even go to the host community and steal a banana or climb a jack fruit tree and pick the fruits. In most cases you have no idea, until you see people coming from the host community to complain to you.(FGD with adult refugee men, Kyangwali Settlement)

Other socially unacceptable practices reportedly resorted to by desperate refugees to access food included taking food on credit without a clear repayment plan, which forces them to hide from the lenders; insisting on taking food from host community members even when permission is not granted; and among in-school refugee children, use of treachery to force children from the host community to throw away their packed food, and then they take it.

I realized that they [refugees] have dark hearts. You may find that one of us sells them produce say, 6 sacks [on credit] but they will not come back to pay you. You will find about 3 traders crying foul at the same issue. Remember we don’t know where they come from. They change location. This affects our relationship with them. They steal from us.(FGD with adult men host Community, Kyangwali Settlement)

Refugees are thieves, they steal our food. They go to our gardens at night and harvest our food, like cassava. Even when they come to your home and ask for cassava and you tell them that you have little, at night they will go to your garden and harvest it. They cannot sleep on empty stomachs when you have a garden of cassava near them.(FGD with male youth host community, Kyaka II Settlement)

…they [refugees] study with our children and our children pack food and the refugees’ children steal the food. These Congolese eat many things; so, these children can kill any kind of creature say the birds… and after killing these animals, they place them in our children’s packed food containers. When our children find such in their container, they pour the food, then the refugees [children] pick and eat it…(FGD with adult women host community, Kyaka II Settlement)

As shown in the above quotes, the theft of food and other unacceptable behaviors of desperate individuals contributed to stereotypes and prejudice against the entire refugee community, as explained later on in the article (see sections on broken trust and reduced willingness to cooperate).

It was indicated that the prevalence of socially unacceptable practices to access food, such as theft and borrowing without payment, had particularly surged following food ration cuts, which underscores the adverse effects of the prioritization of food and cash assistance policies on the food security of refugees. Participants revealed that more refugees were being compelled to steal food for survival and failed to pay debts due to reduced or withdrawn food aid.

What they have said is true, theft has increased because of the [food aid] prioritization [policies]. People are stealing because they don’t have food at home and they cannot die of hunger when they are seeing something [food] there. At first when people were getting some rations, they used not to steal. But now that some people are off rations, they have resorted to stealing…(FGD with adult refugee men, Kyangwali Settlement)

To me that [food aid cuts] is the only cause because when people were still getting full rations, cases of food theft were not as many as now. For the years I have been here [settlement], those problems escalated when people were put off food aid. People are now borrowing from people’s shops and not paying back because of that [food aid] prioritization [policy].(KII with Refugee Local Leader, Kyaka II Settlement)

The theft cases have increased as a result of food aid prioritization [policies]. We used to have like one or two cases in a day, but now we have about 5 to 10. Most of these are food thefts; now that people don’t have food, they go and steal food from the host community. But even here in the settlement, if you have a goat, you have to sleep with it or else it will be taken. So, it is a serious issue.(KII with Refugee Local Leader, Kyangwali Settlement)

Essentially, the reports of widespread hunger and increased recourse to socially unacceptable means such as theft in a desperate attempt to access food are evidence of food insecurity among refugees in the two settlements.

4.2. Quality of Relationships Between Refugee and Host Communities

Study participants were asked to describe the current status of relationships between refugee and host communities. Most participants from both refugee and host communities indicated that their relationships have been generally good. However, there were emerging social tensions and conflicts stemming from food insecurity among refugees. The dominant view was that the increasing thefts of particularly food items by refugees were a major threat to social cohesion among refugee and host community members. For instance, our interlocutors from the host community cited food thefts by some and mainly needy refugees as the major threat to their peaceful co-existence.

Here in Kyaka, the relationship is good to an extent. Because, first of all, we host these people. If the relationship was not good, we would have rejected them. …[laughs]. The problem are the increasing cases of theft. Some bad refugees go to the gardens of neighbouring host communities and steal food. I want to say that the relationship is fairly good, but those cases of food theft are spoiling it…(FGD with adult men, host community Kyaka II Settlement)

Yes, theft is the biggest issue [source of tensions between refugees and nationals]. What I have noticed, it is those needy ones [refugees] that come and steal food and other things from us. I see that they don’t receive enough facilitation because you can find a refugee stealing from you and when you look at their condition you realize that even if you take them to court or punish them, they will still return and steal from you because they don’t have anything to eat.(FGD with adult women host community, Kyangwali Settlement)

The views of host community members were echoed by several refugee participants, who reported that the increased vulnerability and despair among refugees due to cuts in food aid had forced many of them to start stealing from the host community at the detriment of their relationships.

…we were living in peace and harmony with the host community members. But the problem started when people stopped receiving UNHCR money [food assistance] and started stealing from the host community…(FGD with adult refugee women, Kyaka II Settlement)

For me, I will speak about the hosts. We have lived with the hosts and they don’t have any problem. It is us who are disturbing them, when we go there to steal; we go there to do bad things to them. They had no ill feelings towards us; we have lived with them in peace. But because of lacking some things, this is leading us refugees to steal from them.(FGD with adult refugee women, Kyangwali Settlement)

What causes tension between us and nationals is hunger; hunger leads people to go and steal food from the host community, and this disturbs the hosts [community members] so much.(FGD with female refugee youth, Kyaka II Settlement)

It was only participants from one host community in Kyangwali who rated their relationship with refugees as perfect. These participants identified no incidences of conflict over thefts as illustrated below, under the section on conflicts, resentment, and rifts between refugee and host communities.

While the participants at the community level generally identified food thefts by refugees as a major threat to the quality of relationships between refugees and nationals, staff of the UNHCR and OPM appeared to attribute little significance to these cases. All of them described refugee–host community relationships as good without any major threat. They cited only minor incidents of conflict, such as isolated cases of food theft or competition for scarce resources such as land, as shown below.

…Amongst the refugees and the hosts also, there is no outstanding conflict that has been, at least recorded from the time I have been here, from November last year up to now. What we know and the information we get is about the petty isolated incidences of criminal activities. For example, a refugee goes to the host community, maybe steals a banana from the garden of the host community member, comes back, that kind of thing.(KII with UNHCR Staff, Kyaka II Settlement)

For now, so far so good. In the past month, we had issues of land conflict and those around us [some nationals] would influence their neighbours, saying that you cannot do anything with refugees. Overall, the relationship between the host community and refugees is good.(KII with OPM Staff, Kyangwali Settlement)

In spite of differences in the significance attached to food thefts as a threat to refuge-host community relationships by authorities overseeing the refugee response in the country and community members, overall, the above results point to food insecurity as a major source of social tensions that can strain social cohesion between refugee and host communities in the study area, as illustrated in the following section.

4.3. Food Insecurity and Social Cohesion Between Refugee and Host Communities

We examined how food insecurity among refugees affected their social cohesion with surrounding host communities. We found that food insecurity had contributed to breaking trust, reducing willingness to cooperate, and sparking conflict, resentment, and rifts between refugee and host community members, as described in the subsequent subsections.

4.3.1. Broken Trust Due to Suspicion and Perception of Refugees as Thieves

Participants reported that the increased incidences of theft committed by desperate refugees due to hunger were breaking the trust of the host community. Data show that host community members had started perceiving refugees as thieves based on the unacceptable practices of several of them. Consequently, the host community members exercised caution, restraint, and sometimes animosity in their dealings with refugees. Several refugees reported that they were no longer allowed to work in the gardens of the host community unsupervised due to suspicions that they may steal their food or seeds for planting. Others reported being treated harshly.

The refugees go to the nationals and steal. For us who work for the hosts, they start being suspicious of us. They say, ‘you are stealing from us, before you arrived here, we were okay’. We used to go to work and they would welcome us, plus they would come to visit us here and we would welcome them. We lived happily. But when the boys here started sleeping hungry, in the morning they would rush to the nationals to steal. Since they started stealing, the hosts no longer welcome us or leave us in their gardens freely. They think that when they leave us [alone in their gardens] we shall [illicitly] harvest their matooke or steal something else.(FGD with adult refugee women, Kyaka II Settlement)

Trust between refugees and host community members is not much, because some refugees may not have food at some point… So, they go and steal from the hosts [nationals]. So, the hosts will not be happy about this and will start being harsh towards the refugees. When you get to the shamba (farm), to work, they become very strict and constantly supervise you because they don’t trust you.(FGD with adult refugee men, Kyaka II Settlement)

Before, the hosts trusted us. They would give you seeds to go and plant for them. But now, because of those who go there to steal due to hunger, you hear the host [community member] saying that, if I leave you in the garden, you will steal the seeds.(FGD with adult refugee women, Kyangwali Settlement)

Several host community members confirmed being suspicious of and not trusting the refugees with their gardens or any other property. Many of them reported fearing to leave refugees working in their gardens unsupervised, while others guarded their homes whenever refugees were in the vicinity because they thought that they could steal from them.

Theft also underlies the relationship between refugee and host community members. Most refugees are thieves to an extent that we fear to leave them in our gardens thinking that they can steal our matooke and cassava if at all we left them in the gardens alone.(FGD with male youth host community, Kyaka II Settlement)

You can be away from home and you see a refugee from a distance passing by your home and you get scared that they are going to steal your chicken or dog to eat them or he may even break into your house. However, we have some nationals who are also thieves. But even when a person from the host community steals your bunch of matooke, the first suspect is a Congolese (refugee).(FGD with female youth host community, Kyaka II Settlement)

When you see a refugee, you caution the children not to leave the home. That way the refugees can’t come in to steal. So, the children remain behind to guard. If you have no one to leave behind, you will find when they have broken in and taken whatever they want.(FGD with female youth host community, Kyangwali Settlement)

The broken trust cost some refugees job opportunities from the host community. Several refugee participants reported being denied jobs on suspicion that they could steal from host community members, while others deliberately avoided returning to communities from which they had stolen before for fear of reprisal.

They [nationals] give us work and tell us, ‘Don’t steal our things’. If you happen to steal, then you go back looking for work, they can refuse to give you. They can say, ‘You, the other day you stole my things, I don’t want anything to do with you; look for somewhere else to work’.(FGD with male refugee youth, Kyaka II Settlement)

I want to say that when a person goes to the host community, and gets a job to work, they should not steal, because when you steal it becomes a problem. You will not afford to go back there, but when you work as instructed, they will give you something to return home with and cook. Then the next day, you can afford to go back. But when you’re rude, you steal or you cause trouble, you will never go back there.(FGD with adolescent refugee boys Kyaka II Settlement)

Other host community members had stopped entertaining any refugees in their homes for fear that they would steal their property, which denied them (refugees) the opportunity to associate and potentially seek jobs or any other assistance. For instance, one participant reported not allowing any refugees close to their home.

They [refugees] also steal from us. But not from everyone; they choose who to steal from. They stole all the flour from my courtyard. When they come to us with their bad habits, we definitely cannot relate well with them. When I see them getting closer to my home, I chase them because I am sure they will steal my things.(FGD with female youth host community, Kyangwali Settlement)

We can see that not all refugees engage in theft, nor condone the bad actions of fellow refugees who are desperate for survival. However, the increased incidences of unacceptable behavior have fueled negative stereotypes and prejudice against the entire refugee community. The negative stereotypes and prejudice have contributed to breaking the trust of the host community in them.

4.3.2. Fear, Avoidance, and Reduced Willingness to Cooperate with Refugees

Several participants from the host community reported increasingly avoiding to relate or cooperate with refugees. This was because some refugees’ recourse to desperate and socially unacceptable measures to access food and survive in a precarious situation fueled stereotypes of refugees as thieves, difficult, and hostile. Consequently, host community members who had had altercations or negative encounters with desperate refugees reported fearing and avoiding to cooperate with refugees in general. For instance, some of the host community members who avoided relating with refugees because they perceived them as hostile reported being threatened by refugees who were caught stealing their food and other items. They indicated that such individuals were usually armed with machetes. While the threats were arguably a defense mechanism to enable desperate refugees to access food, they fed into stereotypes about the refugee community as habitual thieves and hostile.

We try to cooperate with refugees, say the Congolese, but they are difficult people. They are so uncooperative, they are naturally thieves; whatever you leave outside the house, they will steal. The Congolese do not ask for anything, they just use force because the moment they want something and you refuse to give it to them, the next moment you will not find it there. When they come back and you ask them for your lost property, they will threaten to kill you and tell you of how they have encountered a lot of difficulties. You really become confused; you end up fearing and not wanting to cooperate with them.(FGD with adult women host community, Kyaka II Settlement)

When these Congolese come to our gardens to steal our matooke, they do not come empty-handed. They will come with their sharp pangas and when you find that they have cut down your banana and ask them who gave it to them, they threaten to cut you down too; you have to run for your dear life.(FGD with adult women host community, Kyangwali Settlement)

It was further reported that hunger had emboldened refugees to attack and steal from host community members without any fear. Some of them insisted on stealing even when caught red-handed.

The current relationship we have with refugees is not good, they are constantly attacking us, breaking into our houses and stealing our things. They used not to steal before. They used to fear us and so did we. But right now, they no longer fear, whether you are around or not they do whatever they want with force. That’s the current relationship we have.(FGD with female youth host community, Kyangwali Settlement)

Some refugees come and find you home, but they forcefully go to your fruit trees. Even when you stop them, they still climb [to pick the fruits] without your permission.(FGD with male adolescents host community, Kyangwali Settlement)

In addition, some host community members reported avoiding to associate with refugees because they tended to be aggressive when they felt cheated by host community members engaging them in work, while others exhibited little understanding when host community members were unable to employ or assist them as expected. This aggressive behavior due to despair and frustration further contributed to stereotypes of refugees as difficult and hostile.

One thing I know about these refugees, when they come to work for you and at the end of it all you give them little food in terms of payment, they may end up beating you. They will refuse to take the food and even threaten you.(FGD with female youth host community, Kyangwali Settlement)

About conflict, you may find a refugee is looking for a job and fails to get one and they go to another place and also ask for a job and they tell them ‘no job’ and for them they don’t understand why. They think that they have been unfairly denied a job and the next time they go back to see if they will get a job and you tell them that there is no job again, they will get angry and abusive. They will angrily ask why you don’t want to give them a job and even hurl insults at you.(FGD with male youth host community, Kyaka II Settlement)

The reason why we conflict and don’t want to associate with the refugees is because, there are those who come to us and beg us to give them matooke and we give them. After a few days the same person comes back for beans and you give them. When they come say for the third time and ask for matooke and you tell them that you do not have anything to give them, as they have made it a habit to ask for free food, they will start insulting you, telling you that they did not become refugees by choice and that one day we may be refugees like them.(FGD with adult women host community, Kyaka II Settlement)

Refugee participants also attested to the aggression and force used by some refugees in accessing food and other benefits from host community members. While their views show that this bad behavior was not condoned by several refugees, it evoked negative stereotypes and prejudices against all of them.

We refugees are not the same. There are some refugees who will want to use force. They will want to go there [to the host community] and ask for work and after cut matooke, like two, and go with them. Even when the owner declines to give them, they cut them forcefully. So, you hear the owner complaining that they stole their food.(FGD with female refugee youth, Kyaka II Settlement)

If you are outside the settlement and you come across something you like, you’re supposed to find the owner and ask for permission to pick it. You should always ask and wait to see if they will allow you or not. But some of us don’t take it well when we are not given what we want. Some people decide to use force. They may take things from the host community forcefully, without permission. This usually causes conflict between nationals and refugees.(FGD with male refugee youth, Kyaka II Settlement)

Some host community members who were involved in trade reported unwillingness to cooperate with refugees because several of them tended to take food items on credit and disappear without paying back. Due to these negative encounters, these traders stereotyped refugees as uncreditworthy.

What may undermine cooperation between us the nationals and refugees is for example, he can come to me and I sell him part of my sack of sorghum which he will partly pay for, say 50,000Uganda shillings (USD 13.5). But after, he will shift and go to a location that I don’t know. This will bring about loss of cooperation.(FGD with adult men host community, Kyangwali Settlement)

In essence, hunger has compelled affected refugees to turn to desperate and socially unacceptable measures to access food. Due to despair and frustration, they are also less tolerant of disappointment and tend to respond with aggression. This behavior cultivates negative stereotypes, which spoil their reputation and consequently discourages several host community members from associating or cooperating with them.

4.3.3. Conflict, Resentment, and Rifts Between Refugee and Host Community Members

The increased incidences of theft sparked conflict and evoked feelings of anger and resentment that created rifts and weakened solidarity among refugee and host community members. Several participants from the host community told of breaking ties with refugees they considered friends because they stole from them.

Yes, what breaks our relationships [with refugees] is theft. Because they [refugees] come to visit you when you are sure that the person is your friend. They come to eat at your home and you also go and eat at their home, but when someone [the refugee] has other plans. They might come to visit; you see them seated and relaxed, but when they have not even come to visit but rather there is something they are targeting to steal. Basically, they have not come to visit but are on a mission [to steal from you]. They wait for you to leave and go ahead to accomplish their mission. When you catch them red-handed you automatically part ways…. If you have a high temper, you might also beat them badly and you part ways forever.(FGD with male youth host community Kyaka II Settlement)

Moreover, several host community members who had been victims of theft by refugees expressed resentment and anger towards the refugee community as a whole. Some of them wished for the refugees to return to their home countries, while others felt that they should be encamped to prevent them from crossing into the host community.

The challenge we face is that you plant your garden and the Congolese [refugees] come and steal your crops; you can’t fail to get angry. You find when they have taken the banana you planned to feed the children and you get confused and angry. Then people will tell you a Congolese man has passed here with a bunch of matooke on his shoulders but we didn’t know that you were not in the garden. You get angry and start wishing that they go back to their country.(IDI with female PWD, Kyaka II Settlement)

What I am suggesting is that their leaders in the settlement should establish movement restrictions stopping them [refugees] from crossing to the host community. That will help a lot; they will not steal from us again, because they will be restricted to the settlement.(FGD with female youth host community, Kyangwali Settlement)

The feelings of resentment and anger towards refugees tended to be exacerbated where affected host community members felt that the justice systems were lenient to refugees. Some of them even threatened that they would take matters into their own hands.

The biggest issue that makes us to hate them is their theft. Moreover, even when a refugee steals from you, you’re not supposed to punish them. This has made us hate the refugees because they come, destroy and you can’t complain about them; even when you complain, nothing happens.(FGD with female youth host community, Kyaka II Settlement)

There is nothing that can destroy our relationship apart from them [refugees] stealing our things. If they [authorities] don’t take measures [to bring refugees to book for their actions], some refugees will keep getting lost from here in the host community. They will look for them in vain. A person can’t steal the first time, the second time and the third and go scot-free. You think if the residents get him, they won’t kill him and remain silent?(FGD with female youth host community, Kyaka II Settlement)

Indeed, resentment and animosity toward refugees involved in theft were minimized where the dispute resolution mechanisms were considered fair, as one local leader from the host community explained.

We had issues of theft by refugees, but whenever we would report them to the police, no action would be taken. But now the government has accepted that what concerns the national is what concerns the refugees; the law handles us equally. If he [refugee] steals my banana and I take him to the police, the case that is opened against him is the same case they would charge a national. But because the Settlement Commandant intervenes early in such cases, we no longer have conflicts to divide us.(KII with Local Leader host community Kyaka II Settlement)

Perceptions and attitudes towards refugees were more positive among the few host community members who had not experienced incidences of theft from refugees, which further illustrates the detrimental effects of the vice on refugee–host relations. For example, members of the only host community that did not report any incidences of theft from refugees viewed them as critical to their livelihoods.

Our relationship with the refugees is at 100% [very good]. I will not say that they have bad manners. They don’t steal from us. They don’t steal our animals. It has never happened! Our produce like avocado and jack fruit all have a market as a result of those refugees. You can even sell your avocados at 10,000 Uganda shillings (USD 2.7). Secondly, all organizations that are coming to our place are doing so because of those refugees. At the moment we have very many organizations that are supporting us at school.(FGD with male youth Host Community Kyangwali Settlement)

On the other hand, refugees resented host community members for responding to incidences of theft with violence. It was reported that host community members commonly assaulted refugees caught stealing which did not go down well with them.

The nationals take care of refugees but then you find that some refugees … come and steal from the nationals; and when they are caught and beaten, they start saying that the nationals are bad people. We pick up fights and conflicts from there.(FGD with male youth host community, Kyaka II Settlement)

Moreover, needy refugees were reported to be agitated about host communities benefitting from support that they were both entitled to, as they perceived them as better off.

[Some of] these refugees are so discriminative to an extent that when there is distribution of items in the community, say distribution of soya-bean flour, they feel everything should be given to them. They consider themselves so poor [vulnerable] and thus do not want anyone who is not a refugee to benefit from any support.(FGD with female youth host community, Kyangwali Settlement)

5. Discussion

We have presented data on the manifestations of food insecurity among refugees and how they affect social cohesion between refugees and their host communities. The aim was to provide insights into food insecurity as a potential barrier to social cohesion between refugee and host populations in a low-resource context. This article also contributes to evidence on the broader social implications of the prioritization of generalized food and cash assistance policies being implemented by the WFP in refugee-hosting LMICs.

5.1. Food Insecurity Among Refugee Communities

We have seen that numerous refugee households are experiencing food insecurity because they grapple with limited and uncertain availability of food, and out of despair due to lack of options, resort to socially unacceptable means to access food—such as stealing and use of force—in the face of hunger. Drawing on the livelihood coping strategies indicator for food security, use of socially unacceptable measures to meet dietary needs constitutes a crisis or emergency coping strategy given its damaging and potentially irreversible effect on the survival mechanisms of affected refugees (WFP 2023b). As shown in our results, refugees primarily relied on job opportunities from and the benevolence of host community members to access food. The ability to secure employment outside settlements and camps is generally cited as a critical factor in access to food by refugees in Africa (Baer et al. 2021), particularly in the wake of food ration cuts (Vintar et al. 2022). However, increased incidences of undesirable practices as needy refugees attempt to survive have spoiled the reputation of refugees and consequently strained their relationships with potential benefactors from the host community. Indeed, several refugees were denied job opportunities on suspicions that they could steal from their prospective employers, while others could no longer leverage opportunities from where they had stolen for fear of being harmed. In this regard, the increasing use of socially unacceptable practices to obtain food by refugees indicates that several of their households are experiencing severe food insecurity (WFP 2023b). These findings affirm existing evidence, which points to a general deterioration in the food security of refugee households in Uganda (Bashaasha et al. 2021; UNICEF et al. 2023; Kamugisha et al. 2024). For instance, the 2023 food security and nutritional assessment in refugee settlements of Uganda found that almost 6 in 10 of refugee households were severely food insecure, up from 4 in 10 in 2022. Moreover, 7 in 10 refugee households could not meet their food needs (UNICEF et al. 2023). Another study estimates the prevalence of food insecurity among refugees in Uganda at catastrophic highs of 90%, with those in a protracted situation disproportionately affected (Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) et al. 2022). This shows that refugees in protracted situations are not necessarily less vulnerable to food insecurity than new arrivals.

The escalation of food insecurity in the refugee population of Uganda is generally associated with four intricately linked factors: poverty, climatic shocks, dwindling land for cultivation, and food ration cuts. These factors have been identified as the primary drivers of food insecurity among refugees living in rural settlements of Uganda (Stein et al. 2022; WFP 2023a; UNICEF et al. 2023). However, our data suggest that food ration cuts have contributed significantly to exacerbating the food insecurity situation of refugee households. As shown, participants reported that hunger and the associated surge in incidences of socially unacceptable measures to access food among refugees coincided with cuts in and withdrawal of some households from food aid. Similarly, Gupta et al. (2024) and Stein et al. (2022) found that food aid cuts by the WFP compounded food insecurity among refugees in Kiryandongo Settlement in Southwestern Uganda in the context of the COVID-19 lockdown. Prioritization of general food and cash assistance has also been associated with an escalation in food insecurity among refugees in settlements within northern Uganda (Brown and Torre 2024). The deleterious effects of cuts in food rations on food security are further reported in a study of food aid and coping strategies in Nakivale Settlement in Southwestern Uganda (Vintar et al. 2022). Vintar et al. (2022) found that the section of refugees subjected to food ration cuts in 2015 was more food insecure than their counterparts on full rations. This suggests that full rations are critical for cushioning refugee households against risks for food insecurity such as poverty, insufficient land for food production, and climatic shocks (WFP 2023a). This finding has implications for the implementation of plans to eventually transition refugees in protracted situations from generalized food and cash assistance to livelihood assistance and self-reliance (WFP and UNHCR 2023). Protecting such households from food insecurity during the transition from generalized food assistance to self-reliance requires complementary measures to bridge gaps in food rations in the short to medium term, considering that self-reliance may not be attained in the short run (Baer et al. 2021; Vintar et al. 2022). A key strategy to consider is the use of large one-off or monthly unconditional cash transfers, also known as consumption support, which have been shown to be protective against food insecurity among vulnerable refugee households in the short term, in Uganda and beyond (Hidrobo et al. 2014; Doocy and Tappis 2017; Schwab 2019; Stein et al. 2022; Nisbet et al. 2022; Gupta et al. 2024).

The use of socially unacceptable strategies to cope with hunger underscores the socio-economic vulnerability of several refugee households in Uganda. Extant evidence shows that food insecure populations typically rely on food consumption strategies such as reduced food intake; tapping social resources; and financial strategies such as liquidating material assets and accessing loans or credit to cope (Kisi et al. 2018; Cordero-Ahiman et al. 2018; Farzana et al. 2017; Deschak et al. 2022; Vintar et al. 2022; Dlamini et al. 2023; Elolu et al. 2023). The extreme socially unacceptable measures used by refugees as reported in this and other studies (see Brown and Torre 2024) point to deprivation of material, financial, and social resources among these populations, which essentially limits their coping options. This is in spite of several interventions to enhance self-reliance among refugees in Uganda in the long run. These include allocation of land portions to new arrivals and provision of farm inputs and tools to enable cultivation of own grown food to supplement food aid from the WFP (Gupta et al. 2024). Other livelihood interventions include skilling programs, financial support for income generating activities, and employment of refugees by humanitarian organizations working in the settlements (Kamugisha et al. 2024). In addition, the legal and policy framework of Uganda permits refugees to move out of the settlement to seek employment opportunities (Betts et al. 2022). However, these interventions have been insufficient to propel refugees in Uganda to self-reliance. For instance, studies have shown that the plots of land allocated to refugees are too small to enable commercial agriculture or cultivation of adequate food for household consumption (Betts et al. 2019; Gupta et al. 2024; Kamugisha et al. 2024). Moreover, despite the favorable policy environment, refugees face significant challenges in accessing employment, including limited job opportunities, job market discrimination, and the seasonality of casual labor, which most of them are limited to given their low levels of literacy (Betts et al. 2019; Gupta et al. 2024). Thus, several refugees in protracted situations in Uganda remain highly economically vulnerable, which underlines the continued need for food aid if they are to be protected from extreme hunger and starvation. Moreover, food aid is critical in accessing other essential services, including education and health, in the context of a stretched public social service system (Brown and Torre 2024). In the long run, preventing food insecurity and assuring refugees their right to adequate food (FAO 1996) calls for holistic interventions to increase their material, financial, and social resources. This integrated approach will build their resilience against the multiple shocks that cause food insecurity and economic vulnerability in a context of scarcity such as Uganda (UNICEF et al. 2023). Innovative use of socio-economic interventions such as village savings and cooperative associations may help to boost refugees’ material assets, social capital, and access to credit (Musinguzi 2016; Habumuremyi et al. 2019), all of which can be protective against the major causes of food insecurity, as earlier discussed. To enhance refugees’ accumulation of social capital, proactive creation of savings groups that combine refugee and host community members may be considered.

5.2. Food Insecurity as a Barrier to Social Cohesion

Data show that food insecurity is contributing to deterioration of social cohesion between refugee and host communities in the two settlements. Due to hunger and limited options, both adults and children in the refugee community have turned to desperate and morally unacceptable means to access food at the detriment of their relationships with the host community. These transgressions have broken the trust of host community members. They have also evoked negative stereotypes, prejudice, and bias against refugees by host community members. Refugees are increasingly viewed as habitual thieves, untrustworthy, difficult, dangerous, and aggressive. This spoilt reputation discourages several host community members from cooperating with them socially or economically. Refugees’ involvement in criminal activity such as theft for survival is generally shown to damage public perception of refugees and aggravate intolerance and discrimination against them (Oucho and Williams 2019; Fajth et al. 2019; Deschak et al. 2022). Such negative stereotypes and attitudes do not augur well for long-term host–refugee relations in protracted refugee situations such as in Uganda. Evidence shows that host community attitudes towards refugees tend to endure over generations, as they form at household and neighborhood levels (Betts et al. 2022). Indeed, both young and old host community participants in our study perceived refugees as thieves. This underlines the urgent need to address food insecurity among refugees to mitigate its overarching deleterious effects on social cohesion between refugee and host communities.

However, any dedicated efforts to address food insecurity among refugees will only be possible if the key actors in the refugee response system, the UNHCR and the government of Uganda, acknowledge the gravity of the problem and its overarching adverse social consequences. Our data show that the authorities overseeing the refugee response in the two settlements seemed to undermine the enormity of food thefts and attendant social tensions between refugee and host communities. This could be attributed to low levels of reporting, but it is also possible that they were downplaying the crisis. The latter would not be surprising, since other studies have shown that officials from the refugee response system in Uganda tend to be less open to criticism of the prioritization of food aid policies and interventions to build self-reliance of refugee households (see Kamugisha et al. 2024; Brown and Torre 2024). It is important that both the government of Uganda and the UNHCR and its partners acknowledge the severity of the negative consequences of food aid cuts and prioritization policies so as to institute measures to remedy the situation.

In addition, the increased despair and associated incidences of socially unacceptable behavior in the quest for food and survival among refugees have created rifts between refugee and host community members, thereby attenuating their sense of shared purpose and solidarity. This is evident in their increasing resentment and hostility toward each other. For instance, some host community members perceive refugees as a nuisance and burden and wish for them to return to their countries or be encamped, while others were hostile rather than empathetic towards those caught stealing. Deterioration in social cohesion due to host communities’ perception of refugees as a burden has also been reported elsewhere (Kreibaum 2016; Jayakody et al. 2022). Moreover, the anger and resentment toward refugees was often exacerbated by their hosts’ discontentment with the justice system. Research shows that resentment and negative attitudes towards refugees are not uncommon where host communities perceive injustice in the treatment of the two populations. While extant research primarily focuses on the distribution of services (Guay 2015; De Berry and Roberts 2018; Khasalamwa-Mwandha 2021; Jayakody et al. 2022; World Bank 2022), this study shows that the discontent may extend to justice systems. This highlights the significance of fair dispute resolution mechanisms in promoting peaceful co-existence and social cohesion between refugee and host populations.

On the other hand, some refugees were resentful and hostile toward host community members who reacted with hostility to their transgressions, declined to honor their requests for jobs or support, and those benefitting from any nutritional support because they felt that they were relatively better off. Some refugees essentially saw host community members as competitors for support that should belong to “vulnerable” refugees. This is in spite of the fact that some refugee hosting communities are also experiencing food insecurity (UNICEF et al. 2023). Humanitarian aid in Uganda is distributed between refugee and surrounding host communities on a 70:30 or 50:50 ratio, depending on the project design, as part of the strategies for promoting refugee–host social cohesion. Perceived competition for scarce resources is shown to trigger resentment for refugees and migrants the world over (Lancee and Pardos-Prado 2013; Billiet et al. 2014; De Berry and Roberts 2018; Betts et al. 2022). However, this study shows that negative attitudes due to the perception of competition for scarce resources may not always be from hosts towards refugees. In a context where refugee influxes attract large volumes of humanitarian aid (Ozcurumez and Hoxha 2020; Betts et al. 2022; Zihnioğlu and Dalkıran 2022), extremely needy refugees may perceive the surrounding host communities as competitors for these resources. The refugees’ behavior is consistent with the referent group theory, which postulates that economically strained individuals tend to develop resentment towards those they perceive to be better off (Andrews et al. 2014). Overall, the negative stereotypes, prejudice, hostility, and discriminative and exclusionary tendencies of host and refugee communities toward each other can be explained by the intergroup threat theory. Affected individuals from either community perceive the other group as a threat based on, in this case, realistic concerns about possible loss of material goods and/or economic opportunities and danger to personal security (Stephan et al. 2015).

By increasing incidences of intergroup (refugee–host) hostility, prejudice, negative stereotypes and attitudes, and discriminatory and exclusionary tendencies, food insecurity contributes to social tensions (Artemov et al. 2017) and social fragmentation (Jeong and Seol 2022) among refugee and host populations. Both social processes impede and are indicative of deteriorating social cohesion (Rohner 2011; Guay 2015), as they directly contribute to breaking and undermining trust, inhibiting cooperation, and weakening the sense of shared purpose between refugees and their hosts. Social connections in the host community are critical to the successful integration of refugees in their new host country and communities (Glorius et al. 2020; Strang and Quinn 2021; UNHCR 2024b). Such positive social relations are particularly important in low-resource contexts where refugees typically rely on host communities for livelihood opportunities and other survival resources such as food, land, and other natural resources (Ali et al. 2017; Baer et al. 2021; Smith et al. 2021). Beyond loss of livelihood opportunities, weakened refugee–host social cohesion and ties can contribute to deterioration of physical and mental health among members of the affected refugee and host communities through exposing them to chronic stress triggered by social tensions and conflicts (Kopp 2007). In this regard, deterioration in refugee–host social cohesion is not only inimical to the social integration and overall wellbeing of refugees but also the health and wellbeing of their hosts.

A key limitation of our study was the focus on only two settlements and refugee and host communities participating in the SMILES Project. Therefore, the findings may not reflect the experiences of refugee and host populations outside the SMILES Project area and other refugee settlements in Uganda. Nevertheless, this study provides insights into the manifestations and potential adverse effects of food insecurity on social cohesion between refugee and host communities in a low-resource context.

6. Conclusions

There are indications that food insecurity among refugees in protracted situations can profoundly weaken social cohesion between refugee and host populations in a low-resource setting. In a context of scarcity and limited options, refugees are likely to resort to extreme and socially unacceptable coping strategies, such as stealing and aggression, in a desperate attempt to access food. This damages public perception of refugees and evokes resentment, anger, and conflict that strains relationships between refugees and host community members. The resultant social tensions and social fragmentation contribute to deterioration in core prerequisites for social cohesion, including trust, willingness to cooperate, and a sense of shared purpose between refugee and host community members. There is an urgent need to invest in refugees’ food security not only as a right but also to prevent undesirable social consequences that are detrimental to refugee–host community social cohesion, peaceful co-existence, and ultimately refugee social integration and overall wellbeing.