Abstract

Street vending is a prevalent feature of the informal economy in African societies. Despite its role in generating income opportunities and fostering affordability and accessibility to goods for impoverished urban residents, street vending is considered by many governments to be antithetic to modern urban planning or development and in violation of laws pertaining to the use of public spaces. Whereas there has been an increasing academic interest in informal street vending, this scoping review seeks to identify gaps in the academic literature with respect of how street vending is understood and how conflict between street vendors and public authorities is conceptualized. This review can identify pressing research needs and inform indigenous and sustainable approaches to social work practice at micro and macro levels. This scoping review maps empirical research reported in peer-reviewed literature over a period from 1 January 2010 to 31 May 2024. It addresses street vending in sub-Saharan Africa and seeks to explicate the nature of conflict observed between street vendors and public authorities, theoretical explanations of the problem of street vending and its potential solutions. Few concrete solutions are provided in the literature and there is a clear lack of social work perspective on this topic. We argue that more research from this perspective is needed to gain a better understanding of the lived experiences of conflict faced by women street vendors.

1. Introduction

Informal street vending has become an important form of labour and source of income (Al-Jundi et al. 2022; Mukamba et al. 2024) in contexts where rapid urbanization is leading to staggering increases in urban populations (Haule and Chille 2018). The UN estimates a global increase in urban residents from the current 2.9 billion to 5.0 billion by 2050, when almost 70% of world population will be urbanized (UN-Habitat 2022). At the same time, poverty is increasingly becoming an urban problem and sub-Saharan Africa has the highest incidence of urban poverty globally with 29 per cent of urban dwellers experiencing multidimensional poverty and more than 20 per cent living in extreme poverty (UN-Habitat 2022). Thus, whereas cities may be places where wealth—at least for some—is created, socioeconomic inequality and precarious living conditions are also increasing (Rains and Krishna 2021). Many socioeconomically vulnerable groups view the city as an opportunity to increase incomes and improve their living conditions by engaging in the informal economy (Mlambo 2021). Street vending is the most visible form of this. However, rapid urbanization leads to an increased concentration of people in limited physical spaces and may create severe problems from a lack of necessary infrastructure (housing, electricity, water) and communications to social unrest fuelled by competition over limited social and economic capital (Sakketa 2022).

In the face of social and economic inequalities, the informal economy has been associated with the concept of urban disorder. Urban disorder refers to issues including but not limited to crime, inadequate infrastructure, social inequality, and environmental degradation. It encompasses a lack of harmony in the physical, social, and economic aspects of cities, and is seen by policy makers as requiring comprehensive planning and development strategies to address these multifaceted problems. In urban planning, physical spaces are designed and their uses (economic or social) regulated as a means of mitigating the risks associated with rapid urbanization (Fainstein 2020). Mitigation of risks also includes judicial, economic and social political dimensions (Piffero 2017). Attempts to create order in the context of rapid urbanization is a complex undertaking, particularly since diverse urban populations may have conflicting views and more or less power to exercise in addressing these challenges (Indovina 2016). However, vulnerable groups participating in the informal economy—and those engaging in informal street trading—have been identified not only as at risk due to urbanization but as a risk in contributing to disorder (Young 2017). Street vendors have been a key target for municipal policy makers who have often responded to their informality via aggressive and restrictive policies, violent crackdowns and eviction from public spaces. These conflicts between public authorities and street vendors are the focus of this scoping review.

Following this introductory section, we describe the research process and methodological framework in Section 2. Section 3 presents the results, including the geographic distribution of studies, key themes, and theoretical frameworks. Section 4 discusses the findings in relation to broader debates on urban development, informality, and social work. Finally, Section 5 concludes with reflections on the implications for policy, practice, and future research.

1.1. Street Vending and Urban Disorder

In much of the world, street vendors form an integral part of the informal economy and labour market, providing goods and services to low-income urban residents in various easily accessible locations across cities. They may be self-employed or work as wage earners and can range from poorly organized to highly organized groups. Their vending stands may be fixed or mobile, and they may sell either legally sanctioned or black-market products. Despite their contributions to urban economies, street vendors are often denied the rights and protections afforded to workers in formal employment, as their activities are classified as informal or, in some cases, illegal (Crossa 2016).

The informality of street vendors lies in both the work they do and in the consequences their work has on urban spaces. Defined as “economic activities that do not contribute to the growth of national economies” (Crossa 2016), street vending is often considered a significant source of urban disorder, and a major contributor to plastic and other waste (Jerie et al. 2024). Moreover, the work itself is characterized by informality due to limitations imposed on street vendors’ access to regulated spaces, their unregistered status (rendering them invisible in official statistics), and the fact that they operate outside legal frameworks leaving them without social protection. Consequently, street vendors have very limited legal protections, and they work under precarious conditions (Sekhani et al. 2019).

Whether perceived as causing disorder or simply understood within the context of informality, the problems arising from street vending are cited as a justification for policy makers to enforce urban order (Indovina 2016). A broad review of the literature reveals a fundamental tension between city planners’ efforts to impose a reimagined neoliberal urban order and street vendors’ reliance on daily income-generating activities to sustain their livelihoods. These vendors’ attempts to engage in informal economic work often leads to spatial disputes, as access to certain areas is limited to specific groups and denied to others. This exclusion disproportionately impacts vulnerable populations, leading to conflict between marginalized individuals and authorities such as city planners, law enforcement, and public authorities. These tensions are often framed as necessary to overcome in order for policy directives, such as city improvements, beautification projects, or industrial and commercial development, to be achieved (de Vries 2021). At the same time, the nature of urban conflict and urban violence must be problematized especially in relation to conflict arising from urban planning. For example, Büscher (2018) argues that urbanization should not be automatically reduced to a negative force as the development of cities also encompasses a transformative power for vulnerable groups, including street vendors.

1.2. A Concern for Social Work Research

Urban conflict stemming from rapid urbanization has emerged as a critical area of research, particularly in the disciplines of social work and social development. Examining the vulnerabilities of marginalized groups and their potential for empowerment and transformative change is essential in addressing this issue. In the Global South, street vendors share a common experience of socioeconomic hardship, characterized by a “lack of access, lack of future, and lack of opportunity” (Bhila and Chiwenga 2022). These poverty-driven vulnerabilities align with the core mission of social work, a profession committed to fostering social change, guided by the principles of social justice. In the context of street vending in sub-Saharan Africa, vulnerability may refer to the heightened exposure of vendors—especially women and marginalized groups—to economic insecurity, social exclusion, and repeated threats such as violence, harassment, coercion, and structural abuse, often stemming from unequal power relations and lack of legal protection in urban governance systems. Street vending, as a survival strategy for marginalized populations, particularly in the sub-Saharan Africa, represents a significant site of vulnerability and resistance. Yet, the academic understanding of these conflicts remains fragmented across disciplines, with limited synthesis of how different fields conceptualize and respond to the issue.

Furthermore, little is known about how social work can contribute to the design and implementation of conflict resolution strategies in connection with vendor-authority conflicts. Despite the centrality of poverty, marginalization, and social justice to the profession of social work, the field has paid limited attention to the dynamics of urban conflict involving informal vendors. This omission is notable given social work’s mandate to engage with structural inequalities and advocate for inclusive and equitable social development. To inform socially just urban policies and strengthen social work’s relevance in urban development discourse, there is a need to map how the academic literature defines, theorizes, and addresses conflicts between street vendors and public authorities.

Therefore, the aim of this scoping review is to explicate how academic disciplines conceptualize conflict between informal street vendors and public authorities in sub-Saharan Africa. The review will identify how these conflicts are framed, the causes and consequences described, and the solutions proposed. By highlighting different disciplinary perspectives and gaps, the review seeks to lay the groundwork for a stronger engagement of social work with issues of urban justice and informal economies.

2. Research Process

This scoping review followed the five-stage review process (PRISMA-SCR) described by Arksey and O’Malley (2005). We first identified the review’s research questions. We then identified relevant inclusion and exclusion criteria to search for relevant studies. We carried out study selection, charted the data, and finally we collated, summarized and reported the results. A step-by-step process was documented to ensure the findings reliability.

2.1. Identify the Intial Research Questions

We were aware of the considerable literature on street vending generally and therefore used two different review frameworks to structure our research questions and to determine the key words that helped the authors to find relevant studies. The SPICE (Setting, Perspective, Intervention/Exposure, Comparison, and Evaluation/Outcome) framework served to analyze the research questions facets to delineate the scoping review to a geographical location, from whose perspective the review is examined, to decide what is being assessed and against who/what, and the final intended result. The PICO (population/problem, Intervention/Exposure, Comparison/Context, Outcome) framework was used to ensure the consistency of selected SPICE terms. In all the cases, all the suggested key words were coupled by their synonyms or alternative terms to ensure that the preliminary search was as inclusive as possible. This exercise helped the authors to ensure that the search would identify primary studies suitable for answering the central research questions (Arksey and O’Malley 2005). Synonyms were connected using OR, and different terms were separated by the word AND.

The following initial questions guided the search:

- How are informal street vendors, as a vulnerable group, characterized in the scientific literature?

- How does the literature describe and analyze the dynamics of conflict between street vendors and public authorities?

- What solutions or strategies are proposed for addressing conflict within the existing body of literature?

2.2. Identify Relevant Studies

We began with a clear and agreed-upon definition of “street vending” derived from existing academic literature. Street vending refers to small-scale, economic activity carried out in public urban spaces, typically with limited formal regulation and forming a visible part of the informal urban economy (see for example: Recchi 2021). We carried out a literature search from two electronic databases: Proquest Social Sciences, which includes several databases (most relevant for our subject: Social Science Database, Social Services Abstract, Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts) and Scopus. We note that these databases included social work journals and are also aware that this search may have some limitations as it did not include African Journals Online. We set time, language, setting and publication type restrictions on our search. The database search was supplemented by reviewing references and articles known to the research team. The search concluded on 31 May 2024. Search results were downloaded to EndNote software (2022), duplicates removed and then uploaded to Rayyan software 2021v (Ouzzani et al. 2016) for screening. The following key words drove our search and were organized as follows: “urban development” OR urbanization AND “Street vend*” AND woman OR women OR female AND conflict OR violen* OR repress* OR resist* OR struggle AND develop* OR plan* AND Africa* OR Sub-Sahara OR “Great Lakes Region” OR “Eastern Africa” OR Rwanda.

2.3. Study Selection

Two authors independently screened articles in the search results in step 2 and decisions were blinded using the inclusion and exclusion listed below. We first read records’ titles and abstracts, labelled them based on their geographical area of research, the population, whether they are peer reviewed or not, the language and date of publication. Records labelled “undecided” were decided upon together by the two authors. Included records were put under a second filter where the authors independently tabulated the included records to assess their research focus, the research objectives, the problem statement, the research design, population, the description of the conflict, and the research output.

The following criteria for inclusion and exclusion which were agreed upon by the authors:

Inclusion

- Study must focus on street vendors in Africa, conflict, policy development.

- Target group must be street vendors.

- Study must include experiences, viewpoints, opinion of street vendors.

- Study must have an empirical basis: research focused on investigating “experiences”.

- Study must be peer reviewed and available as a full-text study written in English.

- The publication date must be between 2010 and 2024.

Exclusion

- Wrong publication type (If it is immediately possible to see that the article is not a peer-reviewed source we excluded the source immediately without addressing the other criteria).

- Wrong outcome (Focus is not on conflict between street vendors and public authorities; focus is on gang violence, family violence, child abuse, “war”).

- Wrong population (study focuses on only policy makers viewpoints not on street vendors).

- Not an empirical study (study focuses on theorizing and does not describe empirical research).

- Review (article reviews other research or policy and does not present original research).

- Duplicates (additional duplicates found in the screening process are excluded).

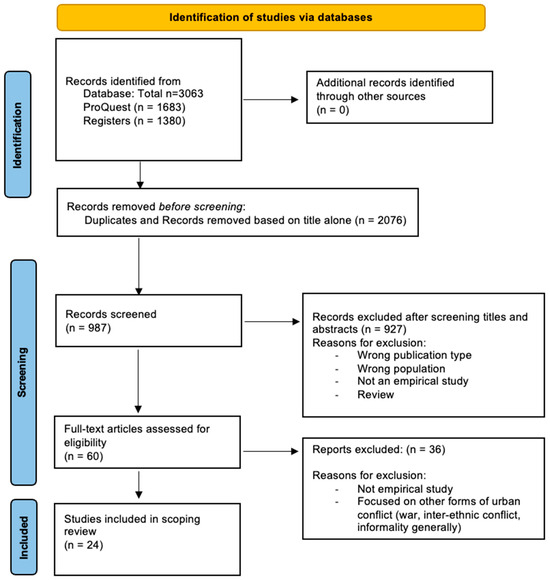

A total of 3063 articles were identified through the database searches. with 987 remaining after the removal of duplicates. Two authors independently carried out a title and abstract review leading to 60 articles remaining which needed to be screened according to our eligibility criteria. Both authors carried out the full text screening of these 60 remaining articles. Twenty-four articles remained that were used in the scoping review. See Figure 1 for the flow diagram of article selection.

Figure 1.

Prisma Flow Diagram of Search Process (Page et al. 2021).

2.4. Data Charting and Collation

At the data charting stage, we used an Excel charting form to guide data extraction from the articles chosen for the scoping review. We developed this form a priori based on categories to answer our research questions (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Charting Variables and definitions.

2.5. Summarizing and Reporting Results

Step five in this scoping review is sorting, organizing and reporting on results and was carried out by two authors while scrutinized by a third researcher. Themes and sub-themes related to each research question were extracted after a repeat reading of each article for familiarization with the data contained within; then, the charted data from all of the articles were sorted into thematic clusters. These themes are discussed in the results section below.

3. Results

3.1. General Description of Articles

In the 24 articles included in this review (see Table 2), ten countries of Sub-Saharan Africa were represented—namely Ethiopia: 2; Ghana: 6; Kenya: 1; Malawi: 2; Nigeria: 3; Rwanda: 2; South Africa: 5; Tanzania: 1; Uganda: 2 and Zimbabwe: 2 articles. No articles were found after 2021—and we consider whether the COVID pandemic could have impacted research and publication on the topic of street vending during the period 2022–2024.

Table 2.

Articles subjected to full text review.

3.2. Scientific Portrayals of Street Vendors in the Academic Literature

In academic literature investigated in this scoping review, we have observed two opposing views regarding informal street vending that often emerge, reflecting diverse perspectives on this phenomenon. These competing portrayals highlight notions of street vendors—as obstacles to urban development and/or as essential to urban economies. We further show theoretical perspectives dominating (or missing) in this research.

3.2.1. Street Vendors as Inimical to Urban Development

Street vendors are often characterized as individuals engaged in informal economic activities, typically with limited financial resources, living in poverty, and operating in unregulated and unauthorized public spaces within urban areas. According to city authorities, as discussed in all 24 reviewed articles, such activities are frequently perceived as creating disorder and posing challenges to the implementation of urban development policies. Furthermore, Young (2017) and Spire and Choplin (2018) highlight that street vending exists within a politically charged environment, requiring vendors to negotiate with governmental authorities for access to public spaces. Similarly, Hove et al. (2020) and Tonda and Kepe (2016) note that street vending is often associated with opposition political parties, with its challenges sometimes leveraged for electoral purposes. Sarpong and Nabubie (2015) describe street vending as a rapidly expanding but inherently unstable sector. Additionally, Mramba and Mhando (2020) and Solomon-Ayeh et al. (2011) argue that street vending is unsustainable, attributing its observed failures and lack of growth to vendors’ insufficient business skills and capacities.

3.2.2. Street Vending as an Important Urban Activity

All twenty-four articles reviewed confirm that urban street vendors make a group comprising both men and women, providing different kinds of services such as: food selling, fruits and vegetables, hair stylists, newsletter selling and other petty services to the local urban communities, with cheaper and accessible commodities. Whereas all authors reported public concerns about street vendors, researchers identified the positive socioeconomic contribution that they may make (Gamieldien and Van Niekerk 2017). A perspective highlights the significant role of informal street vending in providing livelihood opportunities, especially for marginalized or disadvantaged groups such as women, migrants, or those with limited formal education (Akuoko et al. 2013). The review found that researchers emphasized the economic empowerment aspect of street vending, portraying street vending as a means for individuals to earn income, support their families, and achieve financial independence (Adama 2021; Gumisiriza 2021). Street vending is also reported in the same articles to contribute to the local economy by providing jobs and sustain livelihoods.

3.2.3. Theoretical Perspectives

Theoretical frameworks were described in limited or varying detail and for different purposes within the sample of articles scrutinized. Only six articles out of twenty-four based their study design and analyses on clearly identified theories and theoretical constructs. Sarpong and Nabubie (2015) emphasized social constructionism and how the social phenomenon of street vending is created, institutionalized and made into tradition of humans. In addition, they explain how street vendors create friendship bonds for social integration and stabilization of their daily informal business. Tengeh and Lapah (2013) make use of the social network concept and theory of social capital in examining how street vendors engage in networking as a means of inserting themselves into the economic landscape of vending. Solomon-Ayeh et al. (2011) investigate street vending from an urban geography perspective documenting “public space meaning and use”. They discussed social and economic drivers of street vendors returning to sites from which they were evicted. Rights perspectives were also found in our investigation. Adama (2020, 2021) considered “rights to the city,” whereas Mramba and Mhando (2020) based their research on a theory of rights to livelihood and “decent work,” while Moyo (2018) analyzed a right to resistance in investigating “weapons of the weak”. The remaining articles did not explicitly approach their empirical research based on a specific theoretical standpoint.

This scoping review has found both divergences and convergences across disciplinary approaches to investigating street vending in sub-Saharan Africa. Urban planning and political science perspectives tend to frame street vending as a threat to urban order and modernization, emphasizing regulation, esthetics, and state authority. Sociological and anthropological perspectives on the other hand emphasize experiences of survival and resistance whereas economic approaches focus on the limited business acumen of street vendors and how vendors may also interfere with growth ambitions of states. Across the different disciplines, street vending was understood to be shaped by urban poverty, informality, and exclusion although different explicated causes and solutions were tied to academic disciplines. And, while street vendors were recognized as resilient as a group, their contributions to the economic and social contexts were not deeply discussed. Overall, this scoping review highlights gaps in theoretical integration and demonstrates the need for a social work perspective in research.

3.2.4. Gender Perspectives on Street Vending

Less than half of the articles analyzed (ten in total out of twenty-four) explicitly used the word “women” (or synonyms). Yet, even when “women” were mentioned in the description of street vendors, women’s lived experiences were not used in the framing of research problems, analytical discussions or policy recommendations (Adama 2020, 2021; Abebe 2017; Steel et al. 2014; Owusu-Sekyere et al. 2016; Mramba and Mhando 2020; Ndikubwimana 2020; Sarpong and Nabubie 2015; Solomon-Ayeh et al. 2011; Spire and Choplin 2018). This pattern suggests that gender is treated descriptively rather than analytically, reflecting a broader absence of gendered perspectives in the literature.

Only three articles explicitly discuss the situation of women. Even then, gender remains under-theorized. Khumalo and Ntini (2021) highlight that the work conditions are not fair to women vendors who may be parents and do not have access to childcare. Telila (2017) discussed women in a general way as they comprise most street vendors, but the author gave no recommendation to improve the conditions of women engaged in informal street vending. Abebe (2017) explained that most street vendors in Ethiopia are women, and that they work in unfavourable environments. None offered an analysis of the structural gender inequalities underpinning the work and life situations of women engaged in street vending.

This absence of gendered and intersectional analysis in the reviewed literature reflects a broader epistemic gap in urban research in Sub-Saharan Africa, where women’s experiences are acknowledged but rarely theorized. Our review does not reproduce this omission; rather, by identifying and problematizing it, we aim to reveal how the absence of gender analysis itself shapes the framing of urban conflict and informality.

3.3. Conflict Between Public Authorities and Street Vendors

The conflict experienced by street vendors are described as negative relational experience with other vendors, with customers and with city authorities. As the focus of the scoping review is on conflict with city authorities, we examine descriptions of the reasons for these negative relationships below.

3.3.1. Reasons for the Conflict and Why Street Vendors Need to Be Relocated

All conflict described as occurring between street vendors and public authorities involved forcible relocation or simple eviction from public spaces. This is because informal street vendors are identified as antithetic to the modernist clean and beautiful cities and operating in insecure areas. On a more practical level, city authorities and law enforcers are reported in the literature as describing the reasons for conflict in the following ways: conflict arising from littering (causing dirty environment; lack of infrastructure/toilets); creating urban congestion (disturb movements of the public), and creating risks to national security (street vendors as connected to terrorist groups or a part of gang criminality, e.g., facilitating pickpocketing) and causing political unrest (creating political insecurity as against ruling parties). We found one or all the reasons stipulated in articles reviewed. Mramba and Mhando (2020) added that street vendors are accused of favouring child labour resulting in school absenteeism or school dropouts which can no longer be tolerated as it goes against social development goals beyond the scope of urban development.

All articles report that city authorities or law enforcement agencies engage in definitive actions to stop street vendors from being able to carry out informal activities. Typically, where street vending is seen as violating city ordinances, forced relocation is variously termed eviction operations, decongestion exercises, or legal removals resulting conflict with police (Gamieldien and Van Niekerk 2017) in the seizure of goods, monies and sometimes beatings (Owusu-Sekyere et al. 2016). Evictions are sometimes described as ‘brutalization’ but are scrutinized more because of the increasing access to social media (Gumisiriza 2021). The absolute action aims to immediately stop street vendors from engaging informal trade either by direct and face-to-face encroachment or indirect action which marginalizes the activities of street vendors.

3.3.2. Direct Actions Leading to Conflict

Twenty-four out of twenty-four articles describe face to face conflict between street vendors and municipal authorities such as confiscation or destruction of wares to be sold, physical assaults, and forced eviction. Beyond this, cases of death threats on street vendors due to physical assaults are reported in four articles: Adama (2020); Ndikubwimana (2020); Shearer (2020); and Mramba and Mhando (2020).

One article (Mramba and Mhando 2020) mentioned sexual abuse and exploitation, or gender-biased violence. Four articles (Adama 2020, 2021; Gumisiriza 2021; Steel et al. 2014; Ndikubwimana 2020) reported prosecution and imprisonment of street vendors. Ten articles reported cases of coercive payments of fine and bribes by street vendors for space use: Adama (2020, 2021), Gumisiriza (2021), Hove et al. (2020), Mramba and Mhando (2020), Owusu-Sekyere et al. (2016), Solomon-Ayeh et al. (2011), Spire and Choplin (2018), Tengeh and Lapah (2013), and Abebe (2017).

3.3.3. Indirect Conflict Experiences

Where conflict is considered to be indirect, public authorities are described as using another strategy for the removal of street vendors. That is, street shops are demolished of without prior notification to street vendors (Ajala et al. 2018; Mramba and Mhando 2020; Steel et al. 2014).

Other indirect encounters are decisions made or deliberately not made but have negative impact on street vendors’ daily activities and which underlie conflict with public authorities. One of them is a weak legal structure: in some cities, there is no law governing street vending, while in some others the law is very old and is no longer applicable. This was mentioned in two articles: Adama (2021) and Owusu-Sekyere et al. (2016). Meanwhile four articles describe a lack of laws to protect street vendors mostly leading to marginalization and injustice, (Riley 2014; Mramba and Mhando 2020; Telila 2017; Solomon-Ayeh et al. 2011; Adama 2021). This lack of legal structures can lead to a broad mistreatment, marginalization and dehumanization of informal street vendors. A lack of inclusion or integration of street vendors in city activities and in urban planning was mentioned by Gamieldien and Nierkerk 2017; Ndikubwimana 2020; Solomon-Ayeh et al. 2011. One article described the problem of social and spatial exclusion as poor street vendors live in the city outskirts while rich dwellers live in the city centre, therefore making long distance travel to an informal job a necessity (Adama 2020).

3.3.4. Conditions After the Conflict

The effect of direct and indirect interventions by public authorities to stop street vending was discussed in ten articles. This section intends to reveal whether the evictions have been successful. In these ten articles, intervention of urban authorities to impose order and modernity through eviction of street vendors was described as failing because vendors who were temporarily removed came back to the same place sometimes later. This was because the targeted places are vibrant and favourable to street vending (visible places). This pull of attractive areas for street vending was described by Adama (2020, 2021); Tonda and Kepe (2016), Steel et al. (2014); Shearer (2020); Ndikubwimana (2020); Telila (2017); Sarpong and Nabubie (2015); Solomon-Ayeh et al. (2011); Spire and Choplin (2018). In the rest of the articles, it was not whether vendors returned to specific locations after evictions.

3.4. Proposed Solutions Based on Empirical Evidence

Given that this research was interested in empirical articles examining the experiences of street vendors, we anticipated that there would be proposed solutions to the conflict they experience based on the empirical evidence presented in the articles. This scoping review found very little evidence of direct connections between problem definition, empirical results and proposed solutions to the conflict experienced by street vendors.

In addition, given that some studies provided more specific descriptions of street vendors based on nationality, age, level of education, and gender, we expected that proposed solutions would account for these categories. Such findings may be important to know because it seems unlikely that one solution would be fitting for everybody regardless of common conflict themes found in the literature. Unfortunately, none of the articles recommended solutions for a specific group. Two articles envisaged solutions to the problems of street vending based on developed theories (Mramba and Mhando 2020; Solomon-Ayeh et al. 2011). Two studies made general recommendations based on approaches to law enforcement, rights of vendors to legal representation and anti-corruption (Adama 2021; Gumisiriza 2021). Three studies recommended education, human development and skills training as means of ending informal street vending (Ajakaiye et al. 2020; Akuoko et al. 2013; Ndikubwimana 2020). Eight articles proposed inclusion of street vendors in urban planning and conflict resolution based the premise that informality cannot be eradicated only through legal processes or various forms of potentially violent forced removal from urban spaces (Ajala et al. 2018; Hove et al. 2020; Khumalo and Ntini 2021; Mramba and Mhando 2020; Solomon-Ayeh et al. 2011; Steel et al. 2014; Tonda and Kepe 2016; Abebe 2017).

4. Discussion

To provide a comprehensive overview and understanding of the current research on conflict between street vendors and public authorities in sub-Saharan Africa, our scoping review mapped the empirical literature published across a twelve-and-a-half-year period between 2010 and 2024. This scoping review reveals that informal street vendors in sub-Saharan Africa are situated within a contested terrain of urban governance. Two dominant and conflicting portrayals emerge: vendors as obstructive agents undermining urban order, and vendors as vital economic actors navigating structural exclusion. These competing narratives reflect deeper tensions regarding power, legitimacy, and space. These tensions may be best understood through the lenses of both classical and contemporary conflict theories.

Our analysis showed several important academic perspectives, including sociology, economics, urban planning, and political science that social work may make use of. Informal street vending often arises as a response to limited formal employment opportunities, economic inequality, and poverty. Vendors often rely on this informal sector as a means of survival and income generation for themselves and their families. Economic vulnerability and lack of alternative livelihood options contribute to the persistence of informal street vending practices, leading to conflict with authorities attempting to regulate or eradicate them.

This review has shown that urban authorities view street vending as antithetical to urban development. The spatial distribution of informal street vendors can clash with urban planning objectives, public space utilization, and esthetic considerations in modernizing African cities. Informal vending activities may result in overcrowding and conflict over the use of public spaces. Public authorities seeking to regulate urban spaces often perceive street vendors as obstacles to planned development, leading to conflict over the allocation of space and control over urban landscapes. From a Weberian perspective, the state has a monopoly on punitive measures and can enforce authority through formal rules, ordinances, and spatial control. Street vendors, by operating outside of sanctioned systems, are framed as deviant subjects—disorderly, ungovernable, and therefore legitimate targets of enforcement. The state’s attempt to assert control over informal economies represents not merely a legal issue, but a symbolic struggle over the definition of modernity and legitimacy. Law enforcement becomes a tool through which the state performs its authority, often in ways that rely on moralistic or stigmatizing tropes.

Informal street vendors typically operate in a legal grey area or where there are restrictive regulatory frameworks. They are seen as nuisances rather than citizens engaged in informal entrepreneurship. Seen as threats to urban civility and cleanliness, street vendors are stigmatized (Goffman 1963) and are systematically excluded, allowing for the normalization of both direct and structural harms to be inflicted upon them. Added to this is the presence of a demand by the public for easy access to the goods and services provided in the informal economy. Yet they resist as it is a last option for survival. Street vendors may form alliances and mobilize to protect their interests and challenge regulatory measures they perceive as unfair. But as a socially marginalized group, these acts of resistance may compound their stigmatization and perpetuate negative perceptions of their role in the economic life of the community. This scoping review found that there is a repeated use of evictions and that punitive measures do not resolve the presence of street vendors; rather, it creates a cycle of removal and return, suggesting the futility and short-sightedness of enforcement-only approaches. This cyclical conflict reveals the limits of technocratic urban planning frameworks that view informality as a problem to be eradicated rather than a reality to be engaged. In this light, vendors’ persistence becomes a form of what Bayat (2013) termed “quiet encroachment”—a slow, collective appropriation of space that challenges dominant spatial regimes. The return of vendors to evicted sites can be read not merely as a pragmatic act, but as a symbolic and political one—a resistance to exclusion and a claim to the right to the city.

This scoping review has illustrated that the conflict between street vendors and authorities is not incidental, but structural. It is rooted in divergent claims to urban space and competing visions of who belongs in the city. Despite this, only a handful of studies in the review explored alternative governance approaches or community-based responses. The absence of sustained engagement with conflict resolution, participatory planning, or rights-based urban governance points to a significant empirical and conceptual gap—one with important implications for social work. The absence of theoretical engagement in much of the reviewed literature—only six articles applied explicit theoretical frameworks—limits our understanding of these deeper dynamics and underscores the need for more theory-informed analysis that includes social work amongst the dominant urban policy and development research currently undertaken. The near absence of gender analysis in the literature not only limits understanding of conflict dynamics but also reproduces the invisibility of women’s agency in urban economies. Recognizing this absence is thus part of our critical contribution—highlighting how research on informality continues to marginalize gendered and intersectional perspectives.

This review observed gaps in the representation of countries studied. Only 10 out of 49 Sub-Saharan countries are represented although street vending may occur in other countries as well. This gap could reflect our approach to carrying out this scoping review or may indicate an actual gap in studies in some countries. A gender perspective is not explicitly taken even though women dominate in some sectors and the conditions of conflict that they experience may be very different to those of men. The absence of a social work perspective in the articles is notable and discussed below.

Limitations

In carrying out this scoping review, we may have inadvertently omitted articles, despite two authors collaborating in obtaining the sample. A Google Scholar search using the same key words as in the scoping review did not increase the number of relevant articles. Our research questions were guided by an interest in peer-reviewed scholarly work; therefore, grey literature was omitted. We were surprised by the lack of social work research represented in the data we reviewed. However, we cannot assume that social work research is not being undertaken. Rather, our analysis was limited to fields ranging from anthropology to law and political science. We are also aware that articles may have been published in other languages, including French and Portuguese, but we were not able to carry out a review of these.

5. Conclusions

This scoping review found not only that the research points conflict between street vendors and public authorities but also that the conflicts stem from competing interests. Public authorities view street vending as a hindrance to urban modernization, and street vendors are motivated to find means of economic survival. This conflict is bound to continue despite the public authorities’ ability to use both direct and indirect power to temporarily cease the activities of street vendors. These actions may be physical and violent or structural, and street vendors continue to resist, making the conflict recurrent. To move beyond descriptive analyses, future studies should adopt interdisciplinary and gender-sensitive theoretical frameworks, drawing from conflict theory, intersectionality, feminist, and critical social theories. Broader theoretical underpinnings in research may help to uncover how gender, class, and power dynamics shape these conflicts. Research should also examine how women vendors in particular navigate and negotiate these power relations. By making explicit the analytical silence around gender in existing studies, this review models the kind of critical engagement needed to transform future research agendas, rather than replicating their limitations.

Our findings show a need to include a social work perspective in examining conflict arising between vulnerable populations such as female street vendors and those who create urban development policies. In promoting social development and cohesion, social work can bring principles of collective responsibility and social justice to investigations of conflict and to find means to address the complex challenges faced as governments try to raise the wellbeing of all groups. A social work perspective emphasizes the structural and contextual causes of conflict, focusing on poverty, inequality, and exclusion. Social workers advocate for inclusive policies, recognizing the vendors’ rights and livelihoods. They promote dialogue, mediation, and community engagement, aiming for sustainable solutions that address economic vulnerabilities and empower marginalized vendors. Additionally, social work emphasizes human rights perspectives, challenging stigmatization and advocating for equitable urban spaces where both the vendors and the broader community can coexist and thrive.

From a social work perspective, this scoping review highlights the need for more studies in order to improve policies. Such studies may include participatory research to include women and other marginalized vendors in urban policy design; investigations into resilience and capacity building based on the skills of street vendors; and investigations into how gender mainstreaming in social policy may impact informal workers.

Author Contributions

Both authors (M.C.U. and E.K.) made equal contributions to the conceptualization, methodology, investigation, formal analysis, data curation, writing, reviewing and editing of the manuscript. E.K. supervised the study. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Swedish International Development Agency (funding number: FP 1924-20).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This research was approved by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (Record number: 2022-02295-01, 7 June 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created for this scoping review.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abebe, Yohannes Mekonnen. 2017. Challenges and opportunities of women participating in informal sector in Ethiopia: A special focus on women street vendors in Arba Minch City. International Journal of Sociology and Anthropology 9: 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adama, Onyanta. 2020. Abuja is not for the poor: Street vending and the politics of public space. Geoforum 109: 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adama, Onyanta. 2021. Criminalizing Informal Workers: The Case of Street Vendors in Abuja, Nigeria. Journal of Asian and African Studies 56: 533–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajakaiye, Olabisi O., Jubril Zakariyau, Adedotun O. Akinola, Hilary I. Okagbue, and Adedeji O. Afolabi. 2020. Assessment of street trading activities in public spaces (Ikorodu Motor Garage), Ikorodu, Lagos. International Journal of Innovative Technology and Exploring Engineering 9: 1683–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajala, Muniru Alimi, Benjamin Adegboyega Olabimitan, Babatunde Michael Gandonu, and Kayode Onaolapo Taiwo. 2018. Perceived impact of relocation of the displaced street-shop owners on traders psychoeconomic wellbeing in Ibadan Metropolis. Ife Psychologia 26: 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Akuoko, Kofi Osei, Kwadwo Ofori-Dua, and John Boulard Forkuo. 2013. Women making ends meet: Street hawking in Kumasi, challenges and constraints. Michigan Sociological Review 27: 25–43. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Jundi, Salem A., Sarah Basahel, Abdullah S. Alsabban, Mohammad Asif Salam, and Saleh Bajaba. 2022. Driving forces of the pervasiveness of street vending: A data article. Frontiers in Psychology 13: 959493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, Hilary, and Lisa O’Malley. 2005. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology 8: 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayat, Asef. 2013. The Quiet Encroachment of the Ordinary. Chimurenga: Available online: https://chimurengachronic.co.za/quiet-encroachment-of-the-ordinary-2/ (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- Bhila, Ishmael, and Edson Chiwenga. 2022. Informal street vending in Harare: How postcolonial policies have confined the vendor in a precarious subaltern state. Interventions 25: 272–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büscher, Karen. 2018. African cities and violent conflict: The urban dimension of conflict and post conflict dynamics in Central and Eastern Africa. Journal of Eastern African Studies 12: 193–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crossa, Veronica. 2016. Reading for difference on the street: De-homogenising street vending in Mexico City. Urban Studies 53: 287–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vries, Walter Timo. 2021. Urban Greening for New Capital Cities. A Meta Review. Frontiers in Sustainable Cities 3: 670807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fainstein, Susan S. 2020. Urban Planning. In Encyclopedia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica: Available online: https://www.britannica.com/topic/urban-planning (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- Gamieldien, Fadia, and Lana Van Niekerk. 2017. Street vending in South Africa: An entrepreneurial occupation. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy 47: 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goffman, Erving. 1963. Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity. London: Penguin. [Google Scholar]

- Gumisiriza, Pius. 2021. Street Vending in Kampala: From Corruption to Crisis. African Studies Quarterly 20: 81–100. [Google Scholar]

- Haule, Michael John, and Felix Joseph Chille. 2018. Linking urbanization and the changing characteristics of street vending business in Dar es Salaam and coast regions of Tanzania. International Journal of Development and Sustainability 7: 1250–63. [Google Scholar]

- Hove, Mediel, Enock Ndawana, and Wonder S. Ndemera. 2020. Illegal street vending and national security in Harare, Zimbabwe. Africa Review 12: 71–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indovina, Francesco. 2016. Urban disorder and vitality. City, Territory and Architecture 3: 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerie, Steven, Amato Chireshe, Tapiwa Shabani, Takunda Shabani, Pure Maswoswere, Olivia C. Mudyazhezha, Chengetai Mashiringwani, and Lloyd Mangwandi. 2024. Environmental impacts of plastic waste management practices in urban suburbs areas of Zimbabwe. Discover Sustainability 5: 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khumalo, Nomcebo P., and Edmore Ntini. 2021. The Challenges Faced by Women Street Vendors in Warwick Junction, Durban. African Journal of Gender, Society and Development 10: 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mlambo, Courage. 2021. Vendor rights and violence: Challenges faced by female vendors in Zimbabwe. International Journal of Research in Business and Social Science 10: 233–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyo, Innocent. 2018. Resistance and Resilience by Informal Traders in Bulawayo, Zimbabwe: Beyond Weapons of the Weak. Urban Forum 29: 299–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mramba, Nasibu Rajabu, and Nandera Ernest Mhando. 2020. Moving Towards Decent Work for Street Vendors in Tanzania. Utafiti 15: 257–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukamba, Adonia, Florah Sewela Modiba, and David Bogopa. 2024. Women’s participation in street vending: Push and pull factors in South Africa’s Korsten’s informal economy. African Journal of Gender, Society and Development 13: 291–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndikubwimana, Jean Bosco. 2020. Analysis of the Factors Causing the Persistence of Street Vending in the City of Kigali, Rwanda. East African Journal of Science and Technology 10: 85–102. [Google Scholar]

- Ouzzani, Mourad, Hossam Hammady, Zbys Fedorowicz, and Ahmed Elmagarmid. 2016. Rayyan—A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews 5: 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owusu-Sekyere, Ebenezer, Samuel Twumasi Amoah, and Frank Teng-Zeng. 2016. Tug of war: Street trading and city governance in Kumasi, Ghana. Development in Practice 26: 906–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, Matthew J., Joanne E. McKenzie, Patrick M. Bossuyt, Isabelle Boutron, Tammy C. Hoffmann, Cynthia D. Mulrow, Larissa Shamseer, Jennifer M. Tetzlaff, Elie A. Akl, Sue E. Brennan, and et al. 2021. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372: n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piffero, Elena. 2017. Cairo unplanned: Informal areas and the politics of urban development. In Order and Disorder: Urban Governance and the Making of Middle Eastern Cities. Edited by Luna Khirfan and EBSCO Host. Montreal, Kingston and Chicago: McGill-Queen’s University Press, pp. 57–78. [Google Scholar]

- Rains, Emily, and Anirudh Krishna. 2021. Informalities, Volatility, and Precarious Social Mobility in Urban Slums. In Social Mobility in Developing Countries. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Recchi, Sara. 2021. Informal street vending: A comparative literature review. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy 41: 805–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, Liam. 2014. Operation Dongosolo and the geographies of urban poverty in Malawi. Journal of Southern African Studies 40: 443–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roever, Sally. 2016. Informal trade meets informal governance: Street vendors and legal reform in India, South Africa, and Peru. Cityscape 18: 27–46. [Google Scholar]

- Rogerson, Christian M. 2016. Progressive rhetoric, ambiguous policy pathways: Street trading in inner-city Johannesburg, South Africa. Local Economy 31: 204–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakketa, Tekalign Gutu. 2022. Urbanisation and rural development in sub-Saharan Africa: A review of pathways and impacts. Research in Globalization 6: 100133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarpong, Sam, and Ibrahim B. Nabubie. 2015. Nuisance or discerning? The social construction of street hawkers in Ghana. Society and Business Review 10: 102–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekhani, Richa, Deepanshu Mohan, and Sanjana Medipally. 2019. Street vending in urban ‘informal’ markets: Reflections from case-studies of street vendors in Delhi (India) and Phnom Penh City (Cambodia). Cities 89: 120–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shearer, Samuel. 2020. The City Is Burning! Street Economies and the Juxtacity of Kigali, Rwanda. Urban Forum 31: 351–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon-Ayeh, Bettie Emefa, Rudith Sylvana King, and Isaac Decardi-Nelson. 2011. Street vending and the use of urban public space in Kumasi, Ghana. The Ghana Surveyor, 20–31. [Google Scholar]

- Spire, Amandine, and Armelle Choplin. 2018. Street Vendors Facing Urban Beautification in Accra (Ghana): Eviction, Relocation and Formalization. Articulo 2018: 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Steel, William F., Torbi D. Ujoranyi, and George Owusu. 2014. Why evictions do not deter street traders: Case study in Accra, Ghana. Ghana Social Science Journal 11: 52–76. [Google Scholar]

- Telila, Shambel Tufa. 2017. Anthropological Perspective Women’s Street Vending to sustain their daily survival in Urban Life of Dire Dawa: Challenges and Prospects. International Journal of Social Relevance and Concern 5: 15–24. [Google Scholar]

- Tengeh, Robertson K., and Cyprian Y. Lapah. 2013. The socio-economic trajectories of migrant street vendors in Urban South Africa. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences 4: 109–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Tonda, Nanase, and Thembela Kepe. 2016. Spaces of Contention: Tension Around Street Vendors’ Struggle for Livelihoods and Spatial Justice in Lilongwe, Malawi. Urban Forum 27: 297–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN-Habitat. 2022. World Cities Report. Envisaging the Future of Cities. Available online: https://unhabitat.org/sites/default/files/2022/06/wcr_2022.pdf (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- Young, Graeme. 2017. From protection to repression: The politics of street vending in Kampala. Journal of Eastern African Studies 11: 714–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).