1. Introduction

Eating disorder recovery is a fraught and contested space/process, without a clear definition but with considerable social currency. People seeking to establish a sense of greater ease in their bodies after struggling with eating and body distress do so in relation to various discourses on what “recovery” is and should look like (

Churruca et al. 2019;

Holmes 2018;

Malson 1998;

Saukko 2008;

Shohet 2007,

2018). Recovery might be enabled by or performed within particularized, often white, cisgender, heterosexual, female, socioeconomically advantaged matrices (

LaMarre and Rice 2017;

Rinaldi et al. 2016). These matrices present narrow confines for what “health” might look like and in so doing only provide the conditions of possibility for some recoveries from eating distress—those that toe a fine line between so-called restriction and excess, fat and thin, disordered and healthy (

Hardin 2003;

LaMarre and Rice 2016;

Malson et al. 2011;

Musolino et al. 2016). Arguably, the selves recovered in dominant eating disorder recovery discourses align with healthy neoliberal subjects, leaving little room for the articulation of other ways of being. In a society where health has become shorthand for morality (

Crawford 1980,

2006) and self- and other-body surveillance is everywhere (

Jette et al. 2014;

Harwood 2009;

Mulderrig 2019;

Riley et al. 2016), we must consider how recoveries from eating distress converge with, break off from, reproduce, negotiate, and challenge dominant health norms.

Before we begin our exploration, we offer here a few comments on our terminology and approach. Throughout this piece, we pluralize “recoveries” intentionally to connote the changing, shifting, dynamic, and different experiences of “recovery” people may have. We use recovery in the singular when writing specifically about a piece or body of literature that uses the term in the singular. In this article, we delve into the tensions that arise as we surface differences—differences both in terms of processes we followed in our research and in terms of the stories and artistic renderings participants shared. We explicitly frame difference as affirmative, here, rather than “other” or negative—as something that opens new possibilities and ways of thinking and doing (

Braidotti 2013). This orientation aligns with that of others who consider the potential of creative methods “for making dialogue across social problems and uneven power relations possible, but do this in ways that do not erase power, collapse difference or ignore the psychic and material effects of systemic harms” (

Rice et al. 2021, p. 346).

2. Methodological Efforts toward Defining and Delineating Recovery

There is also qualitative recovery research using life-history approaches (e.g.,

Patching and Lawler 2009;

Redenbach and Lawler 2003) and case study analyses (e.g.,

Hsu et al. 1992;

Lea et al. 2015;

Matoff and Matoff 2001;

Shohet 2018), as well as grounded theory (e.g.,

D’Abundo and Chally 2004;

Krentz et al. 2005;

Lamoureux and Bottorff 2005;

Musolino et al. 2016;

Woods 2004) and phenomenological or phenomenographic (e.g.,

Björk et al. 2012;

Björk and Ahlström 2008;

Jenkins and Ogden 2012) approaches. These studies tell us about some pathways and experiences of people working through change/recovery, often from what has been diagnosed as anorexia nervosa, which is often the experience denoted by the term “eating disorder” despite the variability of distressed eating/embodiment. While the majority of studies noted here were conducted with people who had been diagnosed and/or received clinical treatment, there are also some examples of studies incorporating the recovery stories of those who have not been diagnosed or sought treatment (e.g.,

Musolino et al. 2016;

Shohet 2018;

Woods 2004). Nonetheless, efforts toward defining and delineating recovery are most often rooted in clinical practice, with the argument for a consensus definition tied to (in a somewhat circular fashion) the potential for such a definition to provide the foundation for clinical decision-making and research integrity (e.g.,

Bardone-Cone et al. 2010,

2018).

However, the proliferation of qualitative studies over the course of the past 30 years indicates movement toward incorporating the perspectives of people in recovery into research-based articulations about recovery. Some of this work explicitly integrates attention to how and why discourses around eating disorders and recovery might be resisted by people who would otherwise be labelled with an eating disorder diagnosis (e.g.,

Musolino et al. 2016;

Shohet 2018). The majority of messages proliferated in clinical and general society venues alike about recoveries still hinge on airing particular experiences—those of a largely white, female, thin, cisgender, diagnosed, and treated population. This reflects the significant barriers that continue to exist in diagnostic processes and accessibility to treatment for eating disorders (

Cachelin et al. 2001;

Gordon et al. 2006;

Sinha and Warfa 2013;

Thompson 1994), suggesting that large swaths of those experiencing distress may be excluded from such studies.

Further, very little co-designed, creative, and collaborative work provides space for recoveries beyond the confines of “typical” research practice. Those with eating disorders are not typically trusted to tell full or “true” accounts of their experiences (

Holmes 2016;

Malson et al. 2004;

Saukko 2008). Accordingly, what we know about recoveries remains tethered to the dominant discourses researchers, clinicians, and people with eating disorders themselves commonly use to delineate the boundaries between illness and wellness on either “side” of eating disorder and recovery. Further, researchers, and clinicians continue to struggle to find different ways of talking about and doing recovery work, despite years of knowing that (a) existing (particularly residential, hospital, and partial hospitalization) treatment for eating disorders is often ineffective at maintaining wellness in the longer term (

Steinhausen 2009;

Friedman et al. 2016;

Lock et al. 2013) and (b) existing understandings of recovery usually do not present a holistic picture of what recovery is and how to get there, nor an inclusive picture of lived recoveries.

3. Approaching Recoveries Differently

In order to understand, explore, depict, and live recoveries differently, there is a need to approach recoveries in novel ways—methodologically, theoretically, and substantively. Recently, some researchers have begun to employ creative methods to explore recoveries with people experiencing eating disorders, including digital storytelling (

LaMarre and Rice 2016) and Photovoice (

Saunders and Eaton 2018). However, it is still uncommon for arts-based research to be used to explore—and indeed create—new understandings of recoveries from eating distress. In order to step out of our taken-for-granted ways of knowing, we must look differently at research processes themselves (

Levy et al. 2016).

Burns (

2006) suggests that “attending to embodied subjectivity is both an important ethical consideration for our research activities and offers an exciting resource for enriching our analyses” (p. 4), advocating for an approach to research that conceptualizes “the body as simultaneously material and discursive”. As we will demonstrate in this article, creative methods offer an exciting way into engagement with, and analyses of, the constitution of bodies, matter, and discourse, allowing researchers and participants to engage with bodies and the worlds in which they are embedded and impactful. This work aligns with this Special Issue, which is oriented toward “(re)worlding in affective, cultural, imaginative, and justice-attuned (re)ordering ways” (Special Issue CFP) in the way that it pushes forward theorizing around eating disorders and embodied recoveries in entanglement with worlds. As researchers, we were drawn to engage in a deep exploration of how doing research differently and (re)conceptualizing recoveries differently might allow not only for different

theoretical attunement, but how theory can come to life and enable different ways of

doing and living recoveries.

Beyond the eating disorders field, creative and arts-based approaches have generated new meanings of disability and difference (e.g.,

Rice et al. 2017;

Rice et al. 2016), cancer (e.g.,

Frith and Harcourt 2007;

Gray et al. 2000,

2003), sexual health (e.g.,

Crath et al. 2019), HIV/AIDS (e.g.,

Pietrzyk 2009), and other health-related conditions. Arts-based approaches are particularly well-suited for thinking otherwise about health; as

Viscardis et al. (

2019) argue, artistic practices can “unsettle the mythical norm of liberal human embodiment—the rational, autonomous, invulnerable subject—that is foundational to health care and informs health care practice” (p. 1287). Arts-based research occurs across paradigms; feminist new materialist and posthuman-oriented arts-based methodologies in particular may offer up the opportunity to engage deeply and differently with embodied issues (

Crath et al. 2019;

Renold 2018). Such approaches enable researchers to establish “a more direct connection with, and responsibility for, how research practices come to matter (

Barad 2007, p. 89)” (

Renold 2018, p. 37). This is of particular interest in the eating disorders field where what we know and how we construct knowledge is so powerfully inflected with tenacious discourses that limit our ability to imagine otherwise. As

Levy et al. (

2016) note, if we wish to “find new insights” about eating distress, we must “disrupt habitual modes of hearing and seeing research data, with the accompanying biases and blinkers that these habits often entail” (p. 194). One way of engaging differently,

Renold (

2018) suggests, is to bring together “research creation assemblages” (

Manning and Massumi 2014) such that “arts-based research practice can summon new forms of voicing, thinking, feeling and being to emerge” (

Renold 2018, p. 40).

4. Our Research

In this paper, we reflect on our experiences of conducting creative, collaborative research with people with living experience of eating distress and eating disorders who spoke back to existing recovery discourses. Collectively, we re-wrote, re-designed, re-drew, and otherwise re-imagined recoveries. Through online sessions, participants engaged with creative modalities to explore “recovery”, the meaning(s) of recovery to them, and conditions, feelings, relationships, and experiences that make recovery im/possible. As we will discuss, engaging openly with participants about the idea of “creativity” pushed us to reconsider different ways of doing research. We offer our thoughts on the methodological possibilities of conducting creative eating disorders recovery research and reflect on the different aspects of recoveries made visible or possible through engagement with these methods.

5. Methodological Processes

Our work was designed to foreground new knowledges around recoveries and explore the conditions necessary for these recoveries to coalesce. We align with prior feminist new materialist and posthuman approaches to participatory art-making methodologies in and beyond research contexts, which emphasize the emergent and improvisational nature of all research processes, as well as the need to attend to

non-human agency and action in this coming-together (e.g.,

Fullagar and Small 2019;

Renold 2018). Accordingly, our focus was on moving toward the creation of “change-making assemblages” (

Renold 2018, p. 47). The work took place during a global pandemic; thus, we held all meetings with participants virtually. While this arguably meant a kind of

distance from participants and their embodied responses, we encouraged participants to turn their cameras off and work on poems or collages or drawings in a way that suited them before returning to the screen to discuss and explore recoveries. In some ways, this may have

facilitated accessibility in the context of the research, allowing us to do this work across time zones and cities, within spaces where participants could feel more at home (quite literally).

6. Research Team

Andrea LaMarre has been working on eating disorder recovery research for the past ten years, spurred into this work by her own experiences of having and moving through an eating disorder. She is a white, cisgender, heterosexual woman who has benefitted from able-bodied privilege. After receiving eating disorder treatment in her late teens/early twenties, she began to question how systems of privilege uphold certain versions of recovery that privilege some and exclude others. Her research has since been focused on exploring, through qualitative and arts-based approaches, different experiences of recovery in an effort to enliven change and open new possibilities for living recoveries.

Siobhán Healy-Cullen is a white, Irish, cisgender, heterosexual woman. She is a critical health and social psychologist, and so she uses a social justice lens to understand psychological issues as located in socio-political, historical contexts. She is interested in applying creative and critical research methodologies to explore alternative ways of understanding topics that are often discussed from a clinical lens—such as eating disorders—to learn how to better support recovery experiences. Particularly, she is interested in questioning how power shapes health policy/program development—including eating distress/disorder recoveries—and what this means for intersectional social identities.

Jessica Tappin is new to eating disorder recovery research but is completing her PhD on a topic within critical health psychology. She is a white, cisgender, queer woman. She does not have personal experiences but does have second-hand experiences with eating disorder treatment and similarly to the first author was drawn to this research through considerations of privilege in and complexities of this space (although from an outsider’s perspective).

Maree Burns describes herself as a Pākehā, cisgender, heterosexual woman, inconsistently “able-bodied”, who has lived experience of dis/ordered eating. Maree’s professional activities in the eating disorder space include academic research and publications focusing upon how ideas about gender and health shape (1) how disordered eating is understood, (2) peoples’ experiences of eating distress, and (3) options for support and treatment. She worked at the Auckland-based Eating Difficulties Education Network for 10 years and is currently counselling in private practice and in a tertiary setting.

7. Recruitment and Participants

We received ethics approval for this project through Massey University’s research ethics board (Northern) in November 2020. Following approval, we set out to recruit both international and Aotearoa New Zealand-based participants. We recruited participants through social media (Twitter, Facebook), email, and word of mouth. A major emphasis of the project was relationship-building; the first author was new to Aotearoa while conducting this research, and a significant aim of the work was to establish relationships in this setting to better understand the specific needs of those with eating disorders and seeking recovery

1 in this context. The project was designed with flexibility built in to foreground the possibility of interactions with participants to shift and change the aims of the project; difference was explicitly welcomed into research processes. After several months of outreach, we assembled an international workshop with four participants based in Canada and the United States. We ran this 3 h workshop in February 2021. In the workshop, we alternated between group discussions about recovery and the research aims and processes, and individual work to create creative outputs (e.g., collages and free writing).

We experienced significant challenges in our recruitment processes for group workshops.

Miller (

2017) describes recruitment as “unseen work”; recruitment can involve a “fine balance” between seeking people who want to tell difficult stories and being protective of these same people (

Gubrium et al. 2014). We found that some prospective participants in Aotearoa were more interested in individual sessions for personal, logistical and/or scheduling reasons and, at times. because they were telling stories they had not talked extensively about in group settings. Thus, following continued outreach in the Aotearoa context, we established that individual sessions would better suit prospective participants. We applied for and received ethics clearance for a change to the processes to enable one-on-one sessions. This change enabled ongoing outreach, and over the following months the first author held one-on-one sessions (online) with eight participants based in Aotearoa

2.

8. Analytical Approach/Processes

Following the workshop and individual sessions, the authors met to discuss next steps. The first author generated summaries of the workshop and individual sessions based on transcripts, which were created with the assistance of Otter.ai software, and sent these to participants for review. These summaries included narrative summaries of the sessions, as well as verbatim quotes and first-glance thematic observations. These thematic observations outlined key points in each session in relation to the question of what the interaction tells us about recovery. Three participants offered small edits to these summaries. Two research assistants (S.H.-C. and J.T.) reviewed the transcripts and noted observations about key moments of difference in each session. A.L. then re-read each session summary, noted further observations on each summary, and generated a “recovery rhizome

3” outlining various discursive, affective, and material nodes we read in participants’ stories and other creative representations. Throughout the analytic process, there was an emphasis on points of difference or divergence. We did not aim to perfectly “connect up” these differences but rather to look at how they move together—and along with our readings of them. The various “traits” within a rhizome are “semiotic chains of every nature [and] are connected to very diverse modes of coding (biological, political, economic, etc.) that bring into play not only different regimes of signs but also states of things of differing status” (

Deleuze and Guattari 1987, p. 7). Assembling recovery rhizomes was (and is) an unfinished process. Each return to the data and each engagement with it from our various vantage points caused connections to spark.

This difference-attuned approach is inspired by a Deleuzian theoretical orientation, attending to what recoveries might become, rather than a focus on “what they are”. It also foregrounds onto-epistemological entanglement, drawing on Baradian (

Barad 2007) insight that “matter and meaning are not separate elements. They are inextricably fused together, and no event, no matter how energetic, can tear them asunder” (p. 3). In what follows, we demonstrate what this approach can offer in analysis of eating distress/eating disorder research. We present methodological innovations in relation to substantive insights from participants around their eating distress/disorder recovering/recovery experiences. Overall, we argue that throwing away the interview guide and engaging specifically with what participants wanted to share—and how they wanted to say/draw/write/design it—generated new insights about recovery and recovery research including

how that research is conducted. Engaging differently with eating disorder recovery research, as well as with “creative research processes” offers exciting new avenues for this work—and pathways to more inclusive, variable recoveries.

Participant and researcher contributions to the work, and the processes of doing this work, offer up more questions than answers. Below, we discuss three of these questions in detail, namely (i) how participants might re-envision research prompts to generate new understanding, (ii) what it means to be creative in recovery and research, and (iii) how to account for different ways of telling distress and recovery. These questions invite us to consider and account for the importance of differences in recovery tethered to different recovery assemblages. By engaging with differences and questions, we align with

Braidotti’s (

2019) insistence that “instead of new generalizations about an engendered pan-humanity, we need sharper focus on the complex singularities that constitute our respective locations” (p. 53). We understand “complex singularities” as a way to engage with and present data in a way that does not seek to universalize or generalize, but rather to stick with difference, and to welcome disruption to taken-for-granted ways of thinking/doing. For us, these “complex singularities” are made visible through creative research assemblages.

9. How Might Participants Re-Envision Research Prompts to Generate New Understandings?

Given the emphasis of this project on creatively imagining eating disorder recoveries through creative research, prior to beginning sessions with participants, we considered a variety of methods that participants might try out. These included digital collage-making (using online software), drawing, free-writing, found-object stories (i.e., using items in their vicinity to prompt story telling), poetry, photovoice (using photos to tell their recovery journey), or short-form digital storytelling. We also designed a series of prompts which participants could select to explore using these methods. The opening prompt invited participants to consider their journey to the space—a prompt that could be interpreted in relation to their literal journey to the workshop space or to the research, including reflecting on their lived experiences of eating disorders/distress and recovery. Further prompts inviting reflection on recoveries were:

What makes recovery possible?

What is missing in talk about recovery?

How do you feel about the word “recovery”?

What representations of recovery do you want to see?

What does recovery mean to you?

What is needed to support recoveries?

As we discussed core prompts, participants’ responses invited a consideration of aspects of the prompts that the researchers had not previously anticipated but that shifted the lens on thinking through recoveries.

For instance, we spent 15 min free-writing about “What makes recovery possible?” in the group workshop. In our debrief, SS (group workshop participant, based in the United States; they pronouns) reflected on how “what makes recovery possible is kind of in opposition to how I feel recovery is not possible”. SS chose to write a poem in response to this prompt:

What makes recovery possible?

Community & safety

they say nobody can heal in isolation

they say “when you want to, don’t give into temptation”

what is it like to feel held? warm? seen?

I spend so much time worrying about causing harm

that the person who is being harmed is me—

a self-defeating prophecy

what if I am important? favored? free?

It’s hard to think of freedom

when I am both captor & captive

when keeping me oppressed is society’s prerogative

And how can I think of liberation

when others are suffering?

Do I deserve to be sick if I can’t fight for those living—

in poverty, fear, abuse, and silence—

sometimes I think AN

4 is the ultimate violence

To imagine a setting of access & care

is all well & good, but we’re just not there

Is recovery possible? For some, maybe

But I don’t dare think it is possible for me.

The group setting and debrief enabled reflection and analysis of what came up for SS while writing the poem. SS shared that the line that stood out to them in their poem was “it’s hard to think of freedom when I’m both captor and captive” and that “the idea of deserving to not be free. It’s very pervasive”. Their poem illustrates how ideas about what makes recovery possible bring up structural and ideological constraints that mean recovery is positioned as impossible for some. SS positions anorexia as “the ultimate violence” here and explores the ways in which their activism around eating disorder support entwines with their personal experiences. In fighting for systemic change, their own experiences are sidelined; they are called upon to use their energy to enact systemic change when systems do not themselves enable (via funding, resourcing, etc.) the conditions for more people, particularly people with multiple, intersecting, marginalized identities to recover. Their poem also brings to light the limitations of imagining caring and accessible care without the potential for its enactment. While freedom might be configured as a core aspect of recovery, we do not live in a world where freedom (e.g., from poverty, isolation, violence, discrimination, etc.) is equally available and accessible to all. SS later reflected how “community and safety” were necessary—together—for recovery to be possible.

Rhizomes are unpredictable; they branch off in different directions without necessarily following a pattern, but also generate connections across their complex root systems (

Masny 2013). Likewise, prior to engagement in the workshop, we did not anticipate how the prompt “what makes recovery possible” might offshoot into a discussion about the potential

impossibility of recoveries. In practice, conversations leading up to the creative activity in this workshop invited the first author to consider how this question lingers behind her work. This thinking came through in the poem she wrote during the workshop:

I don’t know what makes recovery possible

I spend a lot more time thinking about what makes recovery impossible

And maybe that’s deficit focused.

When I’m doing a project like this

I worry that I will dominate

That my own recovery will take up too much space

And at the same time that it isn’t enough.

I think about how and whether I eclipse

Rather than enabling

I think about pain

I think about what I allow myself

And what I don’t

How to say the things I want to say

While feeling like when I say things I’m never fully present

In this poem, Andrea (she/her) reflected on the potential dominance of her own perspective within the research space, as well as the potential for a deficit focus in the work. This latter comment relates to the ways in which critical research about eating disorders is often perceived as purely deconstructive rather than hopeful or constructive.

Rosi Braidotti (

2019) notes the comingling of “potestas and potentia”, or the dual negation–affirmation that together enable critical work that presents the possibility of forward motion. Both SS and Andrea’s poems illustrate the challenges inherent to doing work that tangles up these two forces—the deconstructive critique and forward, affirmative motion. Furthermore, it illustrates how, on a personal level, this work can lead to questions about one’s own role and recovery.

The inseparability of potestas and potentia mirror the inseparability of considering the possibility and impossibility of recovery—and illustrate “the multi-layered structure of power (as both potestas and potentia): it is not a question of either/or, but of ‘and…and’. Contiguity, however, is not the same as complicity, and qualitative differences can and must be made” (

Braidotti 2019, p. 44). Thinking through potestas and potentia as “and… and” invites us to consider how seemingly small movements for change may add up. It is unlikely that systems that constrain and delimit recoveries will be transformed overnight. However, it might be possible to make “qualitative differences” by deeply and thoughtfully engaging with creative representations of eating disorder and recovery, by taking such representations seriously—and putting those insights “to work” in the service of supporting shifts in research and clinical praxis.

10. What Does It Mean to Be Creative in Recovery and Research?

In individual sessions, participants engaged in various ways with the invitation for creativity. Crucially, participants’ engagement invited the researchers to reconsider the visual and written forms of creativity we had in mind while designing the project. While we may have “plugged in” to the research with a familiar idea of “creativity”, engagement with participants sparked rhizomatic reckoning with the de-familiarization of taken-for-granted ways of doing/being creative. Several participants elected to tell stories about their experiences rather than collage/draw/write/digital story them. In discussing creativity, Scout B (individual session participant, based in Aotearoa; they/them) shared that “I think not everyone does creativity in the same way. So, you know, for me coming up with a whole bunch of ideas. That is creativity. But you’d be hard pressed to get me drawing or painting”. Rather than drawing or painting, Scout B developed a metaphor around a marble run that was sitting next to them at the time. They described how recovery, for them, was not a singular choice but a series of days moving through life. The systems they were working with did not enable the kind of care that worked for their circumstances. The marble run, then, worked as a metaphor “in terms of the way that you get flung through the system. And once you get to the bottom, there’s nothing else, you have to go back to the top”. Scout B’s story of the recovery marble run evidenced how closed off, universalized, and financially, geographically, and ideologically inaccessible systems generated limited points of entry and engagement.

Diana (individual session participant, based in Aotearoa; she/her) similarly preferred to tell her story verbally, noting that this meant she would be less likely to be “overly perfectionistic” about it, but also that she “look[s] at [her] past as if it was a story”. As she noted “I kind of like the goal, like I get perfectionistic, which, I guess, can relate as well to my disordered eating past. But I think like, I just prefer to conceptualize it in story. Because I kind of look at my past as if it was a story”. Method and meaning come together in these words—Diana acknowledged how her desire to tell rather than draw/write/collage her experience may be related to her “perfectionistic tendencies”. Simultaneously, she invited the possibility that this may not be “problematic” or pathological, but rather a part of her preferred ways of making meaning. Throughout the session, Diana’s storytelling invited in perspectives on her recovery that wove together her experiences growing up in North America, surrounded by problematic ideals about bodies—and about womanhood—and her experiences moving to Aotearoa New Zealand and exploring Health at Every Size®

5 communities to support a greater sense of body peace.

Kare (individual session participant, based in Aotearoa; she/her) offered insight into the creative process of storying experiences verbally, reflecting on how “storying my memories, is often quite creative in itself”. The creativity of storying memories Kare spoke to carries significant weight when considering how and when to adopt creative methodologies in eating disorder recovery research. That is, rather than only focusing on content participants share as content or objective facts used to evaluate recoveries, we might spend more time with the ways in which people weave their stories and re-envision “interviews” to invite free-form sharing.

Through storying her memories in a free-form way, Kare, who has European and Māori ancestry, reflected on intergenerational experiences of food and body and the constraints of racism and colonization entwining with norms for womanhood. Echoes of her mother’s and grandmothers’ experiences clearly shaped Kare’s embodied experiences. For instance, she noted that “… food scarcity has played a big role in […] intergenerational suffering”. She reflected on food scarcity on both sides of her family: her European ancestors’ experiences of poverty and rationing in the context of wartime, and her Māori ancestors’ experiences of impoverishment and lack of welfare or other government support. Kare described “the kind of the horror of fetishizing small women when this can come from such oppressive circumstances”, and described how this fetishization was “carried on through generations and intersected with postfeminist discourses of sexuality and sexualization”. Playing out in her experiences of struggle around food and body, “people saw my, my physical appearance as being unattainable, but valorized”—something for which she was framed as a “bad role model”. Thinking back on how she did not receive much sympathy around her suspected eating disorder, Kare noted how this kind of (non-empathetic response)

“has been a theme in a lot of Indigenous women’s lives when it comes to whether it’s mental health issues, or trauma or things like that, often, it’s the woman’s responses that come under scrutiny, rather than the actual circumstances that led them there in the first place”.

As non-Indigenous researchers, we propose a

tentative analysis of the intergenerational interweaving of gender, colonization, and bodies we notice within Kare’s story by linking what we noticed to theory-work from Māori scholars.

Simmonds (

2011) described how “the intersection of being Māori and being a woman posits us in complex and tricky spaces that require careful negotiation” (p. 11). In Kare’s story, we might consider how gendered power intersects with colonizing discourses, constraining the possibilities for bodies, and how this might lead to a sense of being “trapped in a space between worlds” (

Simmonds 2011, p. 11). Problematizing individual responses rather than focusing on the circumstances that keep people small (physically and metaphorically) distracts from what Kare clearly illustrates is a fundamentally intergenerational story of embodiment. This story is interwoven with the ways in which Māori women’s experiences of and access to embodied power and agency has been disrupted (

Simmonds 2011) and fragmented (

Pihama 2001) through processes of colonization.

These insights came through Kare’s stories relatively unprompted; while the first author asked questions about her experiences, she had not anticipated the degree to which Kare’s story would return, time and again, to her embodied learning about bodies, food, eating, femininity, and resistance in relation to her ancestors. Working with story represented an opportunity to work through and tease out a recovery rhizome that moved through these various nodes in a non-linear way.

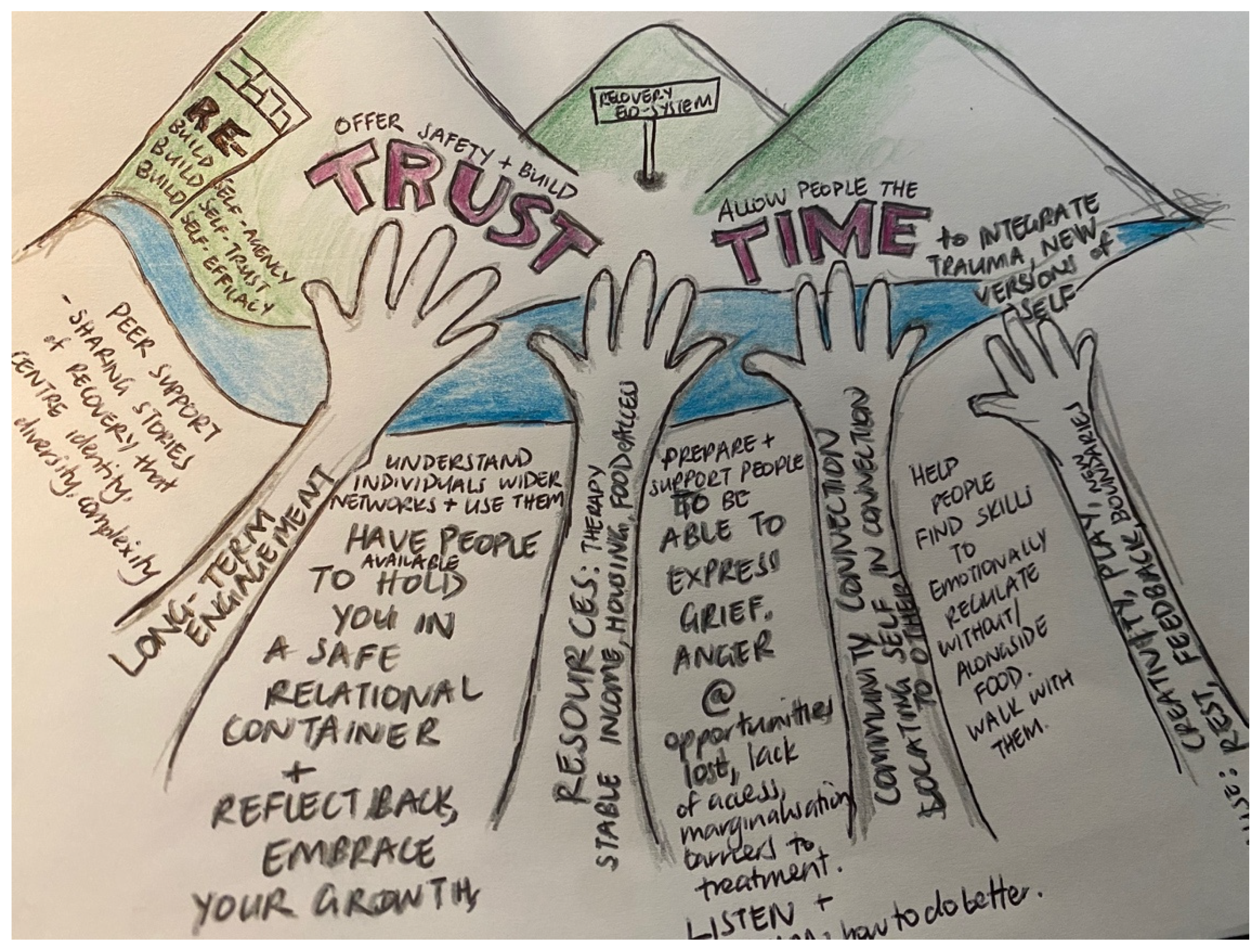

Other participants engaged with visual representations of their recoveries, which likewise added affective resonance and contextual depth to their stories. For instance, Lorraine (individual session participant, based in Aotearoa; she/her) shared “what makes recovery possible” in the form of a drawing with words embedded (

Figure 1):

Lorraine’s drawing shows several mountains bordered by a stream. She described the drawing as demonstrating the “recovery ecosystem”, built on twin cores of trust and time. Hands reaching up toward the mountains hold up the ecosystem, and are comprised of long-term engagement, resources, community connection, and creativity. Playing with the idea of “re” in recovery, Lorraine explored rebuilding in recovery: rebuilding self-agency, self-trust, and self-efficacy. In superimposing written thoughts on her recovery ecosystem, Lorraine’s drawing can be interpreted on practical and affective levels. On a practical level, the drawing points to the material “stuff” of the recovery ecosystem she imagines—how things such as “therapy stable income, housing [and] food access” are key aspects that prop up recoveries. The drawing also positions the development of trust as central—and evidences how the development of trust takes time—and is rhizomatically linked to the development of the material “stuff” named above. Trust is not a given in eating disorder treatment (

Holmes et al. 2021); Lorraine’s drawing, and her story, reaffirm how trust might not be easily built when treatments are oriented toward efficiencies and universalities, rather than collaboration and openness. While the insights Lorraine portrayed in her drawing also came through in her verbalized story, wherein she noted, for example, how she needed to “feel safe enough to keep moving through that process [of integrating theoretical knowing and insight about recovery], rather than just like running away screaming”, engaging in the creative activity branched into an opportunity to reflect together on what comprises Lorraine’s recovery ecosystem.

In summary, these brief reflections on creativity and openness in research encounters signal how our research practices shape who we engage with, how we engage, and what kind of research “outputs” are made possible by different ways of doing. Had we imposed a particular framework for creativity, we may have generated interesting outputs, but these may or may not have resonated with participants’ preferred ways of doing and being. This insight might be entangled with aspects of recovery processes themselves—what might be opened up if we moved toward more explicit centering of people’s preferred ways of being and doing? Thinking this through means considering the ways in which the voices and preferences of people with living experience are often sidelined within mainstream treatment settings (

Holmes et al. 2021). The telling authority of those with eating disorders is often undermined, with the suggestion that “the eating disorder voice” is all-encompassing, rendering the perspectives of people with eating disorders less trustworthy (

Holmes 2016;

Malson et al. 2004;

Saukko 2008).

11. How Do We Account for Different Ways of Telling Distress and Recovery?

Participants’ creative engagements offered up new ways of telling “told stories” of eating distress/disorders and recovery. The “complex singularities” (

Braidotti 2019, p. 53) of each story invites the question of how to account and make space for different ways of telling distress and recovery. Chun Li’s (individual session participant, based in Aotearoa; she/her) story offers an opportunity to engage with questions about what both eating disorders and recovery “are” and “are not”.

Chun Li moved to New Zealand from a country in Southeast Asia in her teens; she identifies with the label of “having some problems” around food rather than “eating disorder”. Chun Li shared that “this was in [country] in the late 80s and I don’t know it wasn’t really a thing, you know”. Subsequently, Chun Li makes sense of her problems around food as being related to moments of anxiety or depression in her life; she explicitly notes that she is not always aware of the link at the time, but on reflection can often see connections between what she describes as challenges with chewing, swallowing, and keeping down food, and other life stressors. She preferred the terminology of “living with, managing it well” rather than recovery, and likened managing these problems to managing other health problems such as asthma.

Chun Li wrote a short story about her experiences, writing from the perspective of herself as a child. An analysis of that story invites new ways of thinking about eating disorders themselves as well as what it means to “recover”. Close to the beginning of her story, Chun Li writes:

That’s what I’m trying to explain. Something is broken. That’s why I can’t eat. So let me tell you what eating is like for me. It’s a daily struggle. After breakfast, it’s a couple of hours before lunch, and I’m already feeling anxious and thinking about lunch. My thoughts go something like, ‘It’s almost lunchtime. Am I going to be able to eat? Or will I just throw up?’ My anxiety about lunch will keep increasing as lunchtime approaches. And now, it’s lunchtime. Today, lunch is spaghetti and meatballs. You will see a plate of spaghetti with tomato sauce, a few meatballs and cheese on top. Nothing out of the ordinary. I, on the other hand, will see a mountain of spaghetti, the meatballs are like boulders, and the cheese on top, like snow on a mountain top. This is a mountain that I will have to climb and overcome. If mum puts a big portion on the plate, I will freak out and think that this is a mountain that’s too high. I cannot climb it.

The “straightforward” read of this story is that Chun Li was anxious about the food in front of her, which made it difficult to eat. This explanation foregrounds a psychological reading of the situation—the idea that Chun Li’s cognitions or misread of the threat of food prevented her from eating. However, Chun Li went on to explicitly position the challenge as a physical, mechanical one, writing “It’s as if my muscles don’t work properly and my brain can’t make the muscles in my throat do the action of swallowing”. Throughout her narrative, Chun Li returned to a refrain around voluntary and involuntary actions. Reflecting on her experience, she wrote:

I am trying very hard to be better. I hope that one day, swallowing, eating and drinking, whether they are voluntary or involuntary actions, can one day be enjoyable actions. They don’t even have to be enjoyable; I would be fine with achievable actions. I feel I have many more spaghetti mountains and other food mountains to climb before I get there.

Throughout her interview and storytelling, Chun Li engaged in a great deal of self-analysis—again putting the lie to the assumption that people with or in recovery from eating disorders are not trustworthy tellers of their own stories (

Holmes 2016;

Saukko 2008). On the contrary, the insights Chun Li developed and shared about her experiences—like those of other participants—can be held as their own truths. Within these excerpts, Chun Li’s perspectives on her desires and goals, as well as her self-assessment, shine through. Moving through the frame she created around voluntary/involuntary actions, Chun Li wrote about a desire to

achieve the ability to eat. She edited her own assertion that this needs to be enjoyable, redressing her own recovery aspirations in relation to a perspective in alignment with her current and imagined reality.

Chun Li aligned in some ways with a progress-based perspective on doing better, expressing a desire to “get there” throughout her story. Chun Li emphasized how eating problems were rarely central in her life or top of mind—they materialized in relation to other stressors. The link between exacerbation of challenges with food and stressors is well-documented. However, taking a closer look at the recovery rhizomes Chun Li drew with her words, this might be connected to those stressors, as well as to her biochemistry; in her own words, “Now I know that it’s all connected with serotonin”. Her knowing forms another trait within the recovery rhizome and affectively generates a sense of comfort even in the absence of other pieces of the rhizome (such as the spaghetti mountain) actually moving.

12. Discussion

The stories shared in this article are only a small sample of the rich, complex, and situated stories and creations participants shared. Academic writing could never do justice to the full richness of these stories—and indeed, the full story is not the authors’ to share (

Limes-Taylor Henderson and Esposito 2019). We selected the excerpts of stories and artistic outputs illustrated here that “glowed” (

Maclure 2013) in their difference. Given unlimited space, we could work through many others, and offer these insights as a first step in demonstrating what becomes possible when we revision eating disorder recovery research. Using examples of participants shifting research prompts, doing creativity differently, and telling unanticipated recovery stories, we have illustrated how being flexible in our engagement with creative methods invited new ways of imagining recoveries.

13. The Creative Research Process

Fullagar and Small (

2019) explored the value of creative research for offering “different ways of engaging with personal stories as political and affective sites of social change” (p. 123). Similarly, our work invites a reconsideration of taken-for-granted ways of thinking and doing eating disorder, disordered eating, and eating problem “recoveries”. Had we not conducted this research in this way, we may have missed affective, material, and relational insights participants shared; indeed, participants’ engagement with our work

shifted the research processes themselves and challenged us to think differently about “doing creative research”. Creatively engaging with recoveries is a political act (

Fullagar and Small 2019), far from a frivolous exercise. Critically engaging with creative methods can help us “to go beyond taken-for-granted assumptions” (

Lupton and Watson 2021, p. 466) to offer something novel and innovative. Eating disorder recovery has been thoroughly explored in academic realms across disciplines and methodologies (see for example

Bardone-Cone et al. 2010,

2018;

Conti 2018;

de Vos et al. 2017;

Malson et al. 2011). By working differently, we found ourselves pushed in new directions, working closely and deeply with participants’ stories and creations to explore what these creative explorations enable. This represents a step toward prefiguring world making and (re)engaging with recoveries in their differences and pluralities.

We abandoned a desire for sameness across research encounters in this project, a move that could be deemed problematic within a system of knowledge that prizes replicability and universality. In this, we align with those who argue that “if method is pre-given and known in advance, it also suggests that data is an already pre-supposed entity that is waiting to be captured, extracted, and mined” (

Springgay and Truman 2018, p. 204). Methods are not neutral, as those working from Kaupapa Māori and other Indigenous methodologies (e.g.,

Jones and Jenkins 2008) have long shown. In working our creative methods

with rather than

for or

on participants, we opened up to that which we could not have anticipated prior to engaging with them—participants’ stories and ways of engaging fundamentally shaped and shifted the research assemblage itself. Our research practices came to matter (

Barad 2007) in the divergent, disparate, and different stories—and ways of showing and telling stories—that this research invited. Rather than gloss over the differences in participants’ stories and ways of engaging, we center them here (see also

Rice et al. 2021).

14. Key Insights

Substantively, participants’ stories invite several key insights about eating disorder recoveries. In poetry, participants and researchers in this study puzzled through how the possibility of recovery is entwined with the impossibility of recovery. Various facets of participants’ stories crystallized power relations that constrain access to services and align with desired ways of doing recovery and being recovered. Material and systemic factors such as secure food, income, and housing operated within the recoveries participants experienced or wanted to be made possible. These co-mingled with needs to acknowledge how intergenerational body and food experiences shape and shift what people know and feel in their bodies. Participants’ stories could be “read” on multiple levels; taking into account histories within treatment praxis and research literature of people with eating disorders as untrustworthy (

Holmes 2016;

Holmes et al. 2021;

Saukko 2008), it becomes particularly important to privilege participants’ own articulations of their stories. This is arguably particularly true when a disconnect between dominant “reads” of eating disorders and individual experiences had meant that they did not share their stories with anyone until they participated in this research.

15. Summary

Methodologically, our work invites several provocations for those seeking to dig deeply into the situated, contextualized experiences of people who live in relation to diagnosed or undiagnosed eating disorders and legitimized or delegitimized recoveries. Firstly, given that many of our participants were undiagnosed and/or had experiences with treatment systems that led to them seeking help and support outside of mainstream systems, this work invites questions about whose recoveries the mainstream academic literatures typically feature. Had we narrowed our selection criteria to those who were diagnosed and/or treated in mainstream systems, we would have missed engaging with those who did not fit this mold. Working closely with those who worked through recoveries alongside, in spite of, or outside of these systems invites new ways of storying and doing recovery. Secondly, remaining open to different ways of engaging with creativity taught us about the value in flexibility of method and how abandoning a desire for sameness invites unanticipated yet impactful differences. Together, our insights on content and method center around a call we issue to those seeking to explore eating recoveries in a richly nuanced way: invite and welcome difference. Doing so opens up opportunities to enable our research—as well as advocacy and treatment—to be driven by collaboration and openness, rather than manualized and universalized approaches.

16. Limitations and Considerations

While this kind of research can open up new ways of engaging with participants and with recoveries themselves, it does not always align with the research agendas, priorities, and practices embedded in neoliberal systems. Both treatment-as-usual and research-as-usual are strongly encouraged—if not enforced—in Western neoliberal systems. A deep dive into the reasons for this is beyond the scope of this paper; briefly, funding systems in private and “public” healthcare systems alike provide for only some forms of treatment, accessible only to those who fit narrow criteria for eating disorders. As several of our participants indicated, even when one does fit those criteria, existing modes of treatment do not always facilitate lasting “recoveries” that align with participants’ contexts. In a “managed care” system, evidence-based treatment is upheld as the way to engage with eating disorders (

Lester 2019). In its fullest realization, evidence-based practice should include not only research evidence, but also clinical and lived experience (

Peterson et al. 2016). As

Peterson et al. (

2016) note, however, in practice one or more of these “legs” of evidence-based practice may be sidelined. Others have noted the pervasive mistrust of people with eating disorders (e.g.,

Holmes et al. 2021); this mistrust may lead to the sidelining of lived experience in particular as a “valid form of expertise” in determining treatment approaches and orientations to recovery.

Likewise, in research, there is a strong pull toward delineating what recovery “is” and what it “is not”. In transparency, the first author has previously been involved in this kind of work to call a consensus definition of recovery into being. Such a definition—and guidance on how to reach it—has been deemed practically useful for clinical work, as well as to govern inclusion in research studies. There is merit in this view, and we do not wish to ignore the clinical and lived realities facing those working through eating disorders who may find such criteria useful. Indeed, getting on the same page about recovery can be incredibly helpful in facilitating healing (

Musolino et al. 2016). And, we cannot ignore the ways in which power flows through attempts to delineate what “recovery is”—nor can we ignore how any normalizing and universalizing definition stands to potentially exclude those who do not fit (

Davis 1995).

Even conducting qualitative research in eating disorders is often framed as a sideline consideration or something that will later require quantification in order to “count”. Quantitative research can (a) be critical and (b) be conducive to making large-scale decisions about ED treatment and recovery. What may be neglected in discussions of qualitative versus quantitative eating disorder research is that these approaches are fundamentally attempting to do something quite different. In an approach like ours, the priority is on exploring the nuances and needs of people working through relationships with food and body entangled in contexts that constrain opportunities for flourishing. It is not on elaborating a universal approach to either treatment or defining recovery—indeed, it invites resistance to the idea that such a universal approach is the way forward. Altering any aspect of the assemblage shifts the whole assemblage (

Deleuze and Guattari 1987).

We anticipate that there will be questions about how such work might make a difference while the broader systems described above continue to exert their universalizing pressures on eating disorder treatment and research. We propose that such an opening presents a crack in the foundations through which to begin to have conversations about the need for both in-the-moment, individual shifts in how recoveries are understood and conceptualized, and broader systemic changes to lead to later, larger, systemic changes. In all of this, we recognize that new is not necessarily better. However, as

Gail Weiss (

2008) suggests, “If social, political, and material transformation is to have a lasting impact on individuals and society, it must be integrated within ordinary experience” (p. 1). The experiences we have explored throughout this piece offer difference in these ordinary experiences that, in the long run, may help guide (albeit slowly) toward broader systemic change.