Lobbyists in Spain: Professional and Academic Profiles

Abstract

1. Introduction

- The capacity to mobilise lobby supporters or members as a sign of social support in the context of public opinion has a relevant value in the democratic system. Thus, there are interest groups that mobilise their members through public demonstrations, support in the form of messages in various formats, explaining the number of followers or valuing the economic volume generated in the sector, among others (Branton et al. 2015; Rasmussen et al. 2018; Mergeai and Gilain 2020).

- The lobby’s financial capacity allows it to deploy a set of activities that cannot be carried out by lobbies with scarce economic resources. Hence, business or employers’ lobbies have greater resources than those that generate resources through the volume of their membership, such as NGOs, consumer associations, professional associations or trade unions. These resources, in turn, can be projected onto other capacities available to lobbies (Schnakenberg 2017; Dür 2008; Carty 2010; Galbraith 1956; Dempsey 2009; Sadi and Meneghetti 2019).

- Access to public authorities is essential to be able to engage in dialogue with decision-makers, as it is difficult to gain support for a proposal simply by handing over documentation or through grassroots campaigns. This capacity is part of the revolving door concept because those who have been part of the public authorities maintain a network of contacts that allows them to interact more easily. Likewise, having knowledge of the gatekeepers in the administration or the legislature is essential to know whom to act on, a responsibility that does not necessarily fall on the person with the highest hierarchical rank (Dür et al. 2015; McGrath et al. 2010).

- Advocacy helps when there is a fit with social values because it is easier for rulers to make decisions with social demands that are in line with what is acceptable to the population as a whole (Rasmussen et al. 2018; Biliouri 1999).

- Having a good social image facilitates the lobby’s work, as its proposals seem to have a higher level of legitimacy (Klüver et al. 2015; Marshall 2015; Rasmussen 2015; Lowery 2013).

- Occupying a strategic space in society or the economy also confers greater weight on dialogue processes. This would be the case of the role of the financial system in the economic system, which is concretised in an expression widely used in European institutions, such as that they are “systemic elements”, i.e., that they underpin the system.

- 26% are between 20–29 years old;

- 36% are between 30–39 years old;

- 19% are between 40–49 years old;

- 12% are between 50–59 years old;

- 7% more than 60 years old.

- 1% are between 20–29 years old;

- 8% are between 30–39 years old;

- 37% are between 40–49 years old;

- 34% are between 50–59 years old;

- 20% more than 60 years old.

1.1. Initiatives

- Require public institutions and representatives to proactively record and publish information on their interactions with lobbyists, including summaries of meetings, calendars, agendas and documentation received.

- Ensure that a “legislative footprint” is created for each proposal in order to ensure full transparency of decision-making processes.

- Ensure that records apply to both direct and indirect lobbying efforts, targeting all institutions and individuals who play a role in public decisions.

- Introduce a legal obligation for public authorities to strive for a balanced composition of advisory and expert bodies, representing a diversity of interests and views.

- Make open calls for the constitution of advisory/expert groups and ensure that common selection criteria are used to balance different interests.

- Publish legislative footprints to track, in a uniform manner, contacts and input received on draft policies, laws and amendments.

- Ensure greater transparency on the composition and activities of expert groups by publishing information on the selection process of members, as well as the publication of detailed minutes of meetings.

1.2. Lobbying and Communication

- Proactive strategy, in which the lobby takes the initiative in the definition, elaboration and approval of public policies, allowing it to raise situations and anticipate issues that may affect the interest group. Having the ability to be able to raise issues that may affect the lobby’s interests facilitates the structuring of the issue, delimits the conceptual boundaries of the discussion and influences the approach to the solution to the problem (Schnakenberg 2017; Carty 2010; De Bruycker 2016).

- Reactive strategy, which is delimited by a passive action of the lobby, which is only put into action when a decision affecting the lobby’s interests is being raised, discussed or approved. This action does not allow solutions to be put forward but starts from a defensive activity, which greatly reduces the scope for action (Chari and O’Donovan 2011; Rasmussen et al. 2018; Benítez 2018).

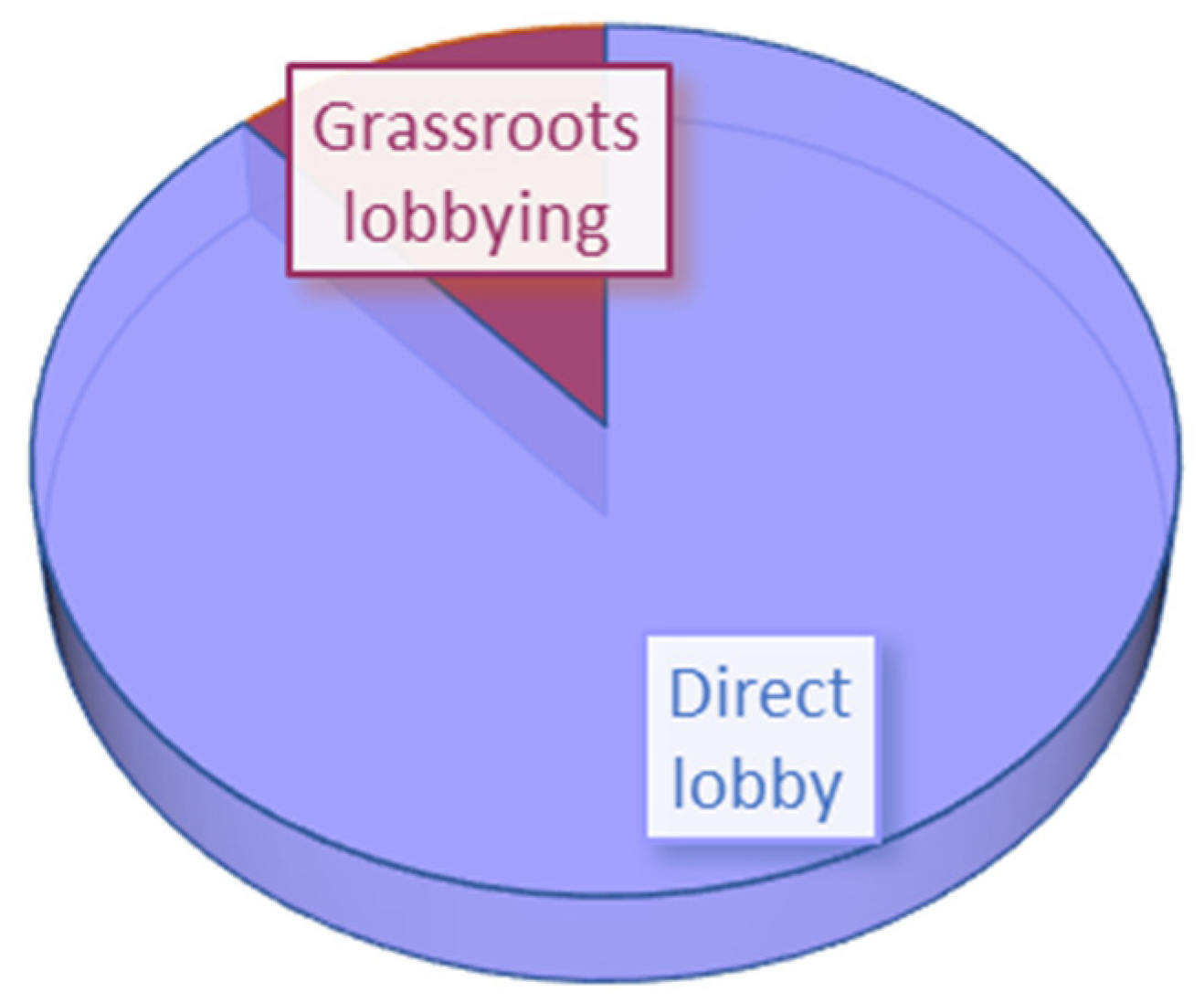

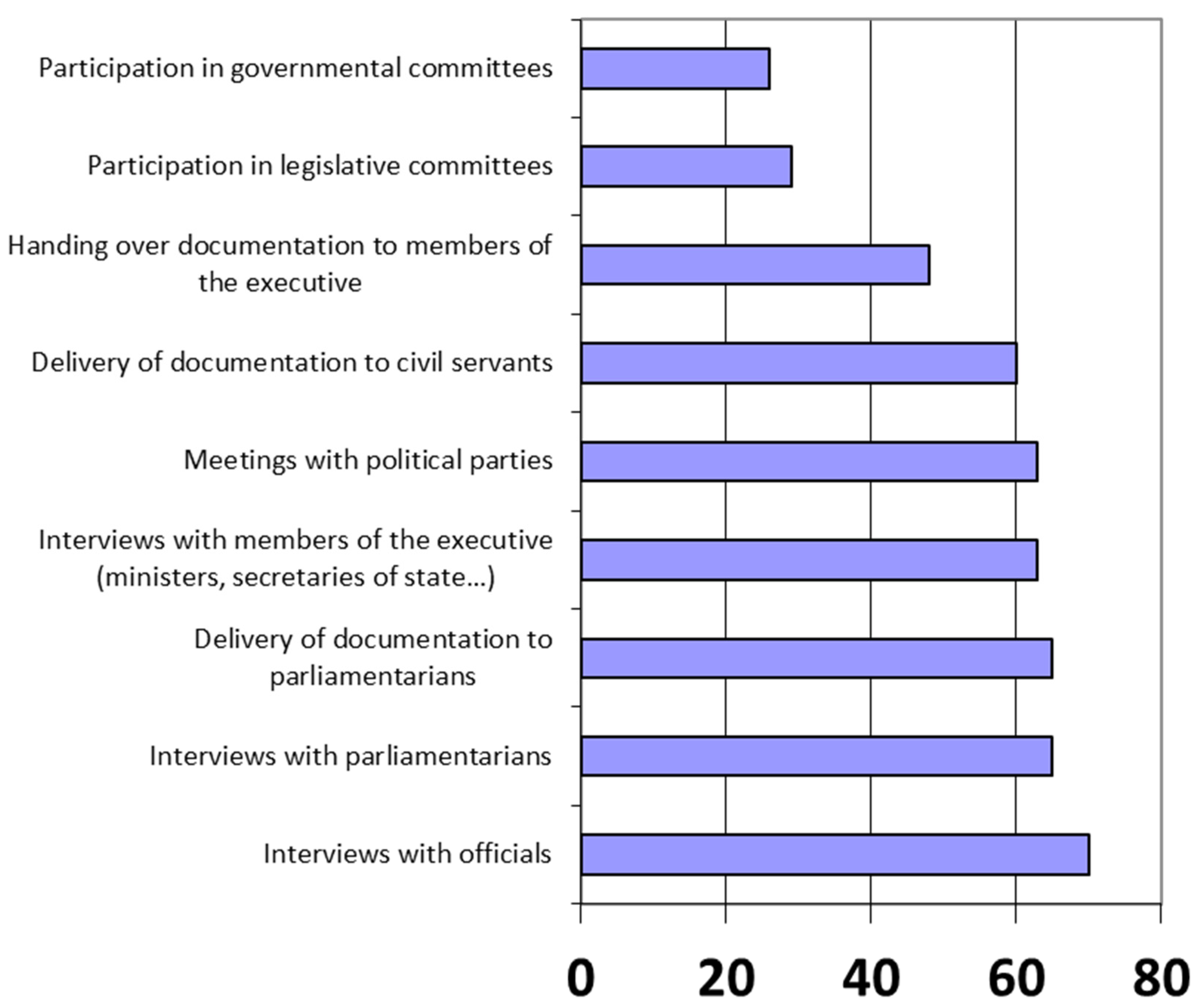

- Direct lobbying: organised as direct relations with the members of the institutions on which the lobbies act. These actions can be dialogic (conversations, interviews and reviews) with members of the legislature to the executive; delivery of specific or general documentation; and participation in advisory or expert commissions (Castillo-Esparcia et al. 2020; Castillo-Esparcia 2011).

- Grassroots lobbying: such as communication campaigns in support of the lobby’s demands through the media, campaigns on social networks or mobilisation of people (Arceneaux 2018; Dempsey 2009).

- 8.

- Direct online citizens’ petitions;

- 9.

- Letters to government or parliamentarians;

- 10.

- Public debates;

- 11.

- Leaflets and posters;

- 12.

- Demonstrations, among other activities, in order to put pressure on politicians to listen to them;

- 13.

- The use of related organisations such as advocacy associations;

- 14.

- The use of other entities such as think tanks;

- 15.

- Blogging;

- 16.

- Cyber activists writing on social media.

1.3. Media Appearances Functions

- They show and present themselves as determined subjects with the publicity (making public) of the interpellations of their members, because the existence of the express requests of a group is the prerequisite for social sustenance and legitimacy.

- In certain situations, they can advocate the mobilisation of the public in general, and of their members, in particular, in order to propose community support for a better implementation of the demands made to the public authorities.

- They present a psychic cohesion activity on the part of all their members, which makes them participate in a common grouping. This feeling of belonging is significant in societies with a high degree of individualism.

- One of the premises when carrying out certain actions in the media is the intention to educate the recipients about the association’s issues and its problems. This is a medium- and long-term function that aims to predispose collective behaviour to an acceptance, understanding and internalisation of the group’s objectives.

- Social conflict is also reflected in the struggles between information sources to influence the communicative system. Of all the events that have taken place, only a limited number are shown, which is why each organisation tries to ensure that its proposals are echoed in the media. In addition, by socially radiating its own objectives, it manages to restrict the access (qualitative and quantitative) of other groups that may appear to be rivals.

- As soon as one manages to penetrate the editorial content of the media, one should try to ensure that the image reflected is favourable. It is not so much important to have a high success rate, but rather that the appearances are qualitatively positive.

- Presenting and promoting itself as an organisation dedicated to a specific issue allows the interlocutors (individuals and the media) to frame the association within the aforementioned issue, which subsequently helps to obtain a certain monopolisation of the competing activity. Thus, we can observe the clear examples of Greenpeace (environment) and Amnesty International (human rights), which have achieved the identification between association and defended matter.

- The previous steps have the scatology of achieving the acquiescence of the media, individuals and public authorities that legitimise the actions implemented by the group. In this way, the lobby group becomes a subject to be consulted and listened to in its field of application.

- With regard to the political system, they convey an image of public opinion that offers support to the associative demands, thus achieving a much broader force than the real one. It should be noted that appearing in the media gives the possibility of offering a public image of the group’s representativeness, but it is also a key factor in assessing the degree of social support for the group’s demands.

2. Materials and Methods

- SO1: to understand the demographic profile of lobbyists in Spain.

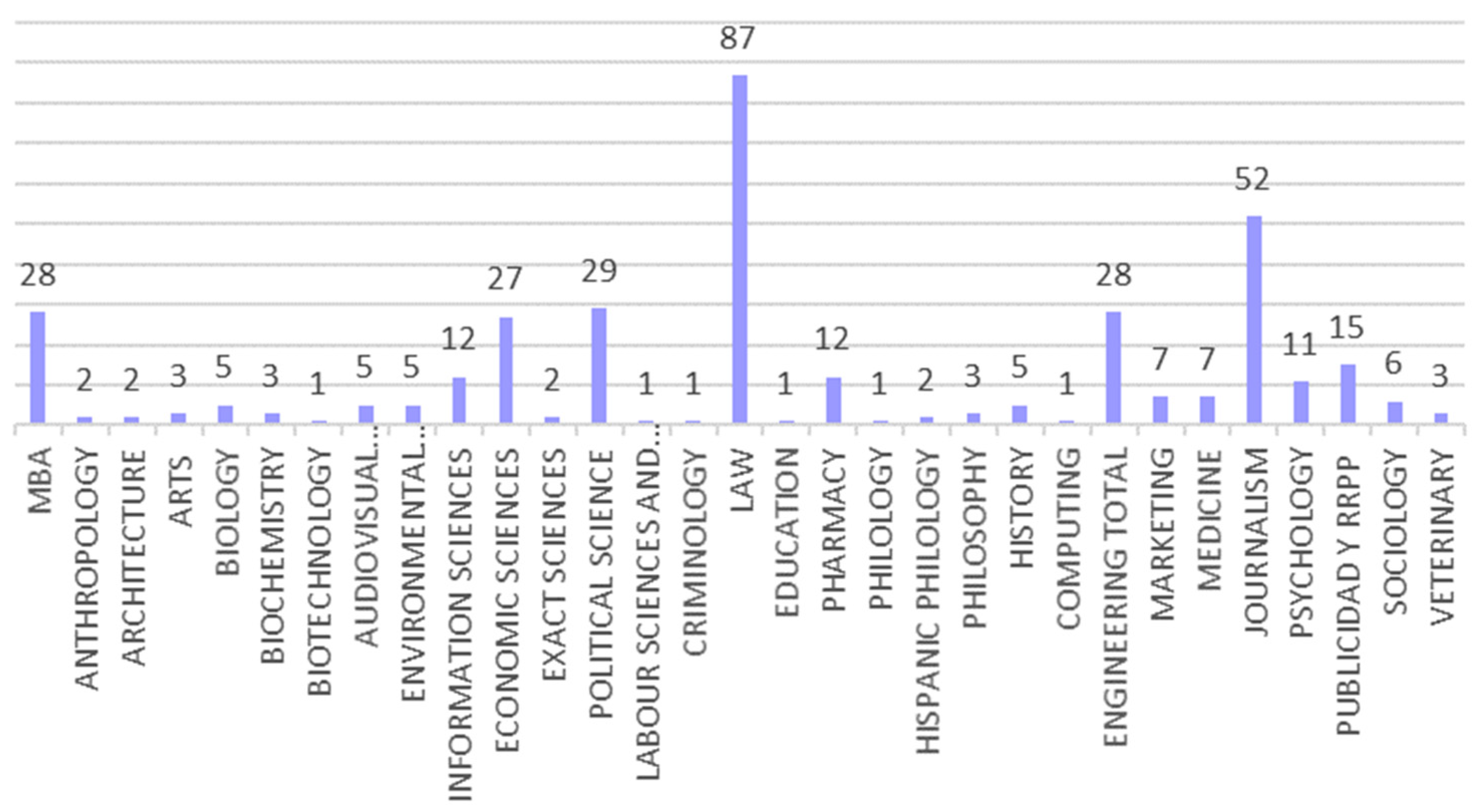

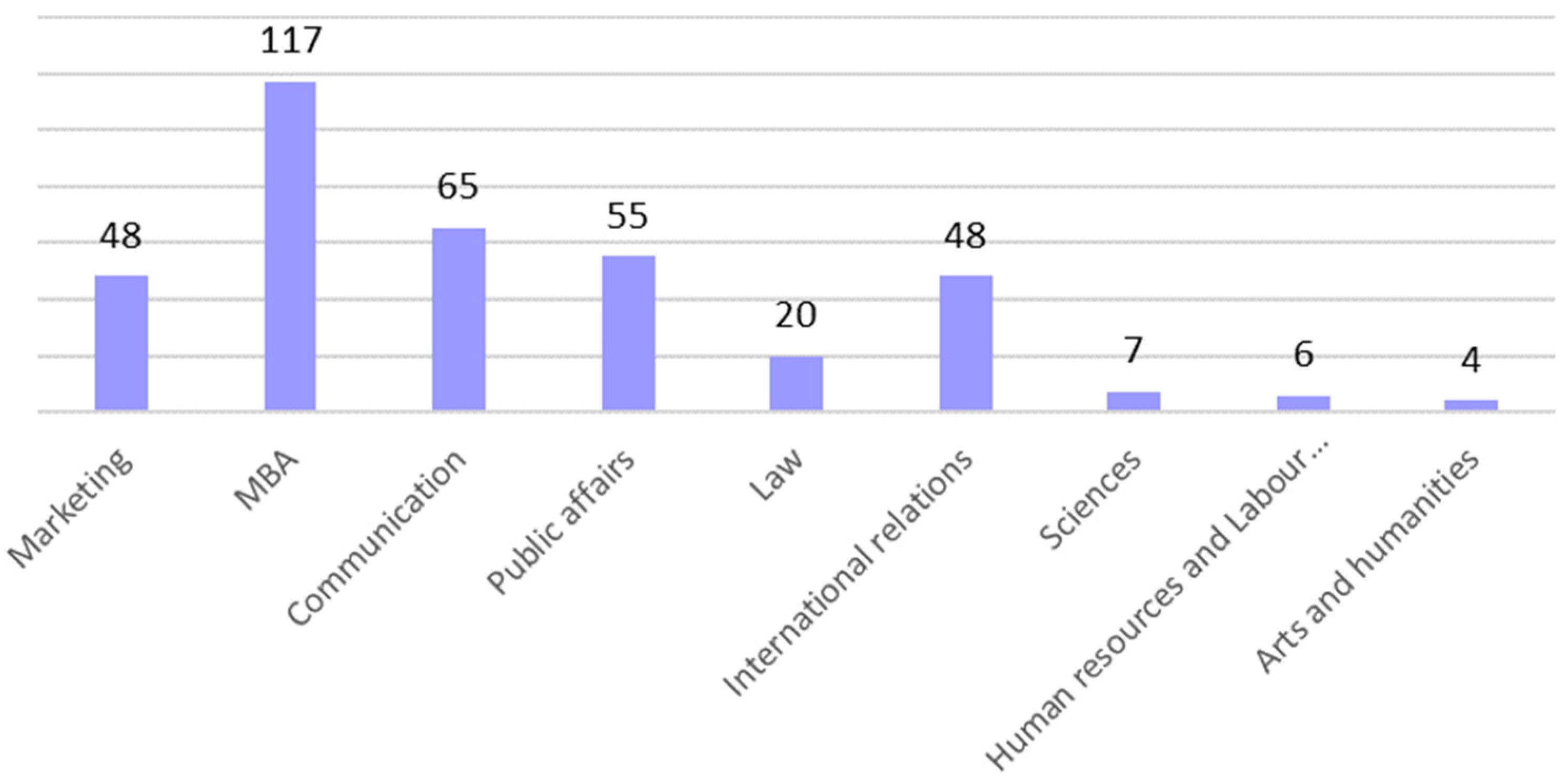

- SO2: to analyse the qualifications of lobbying professionals.

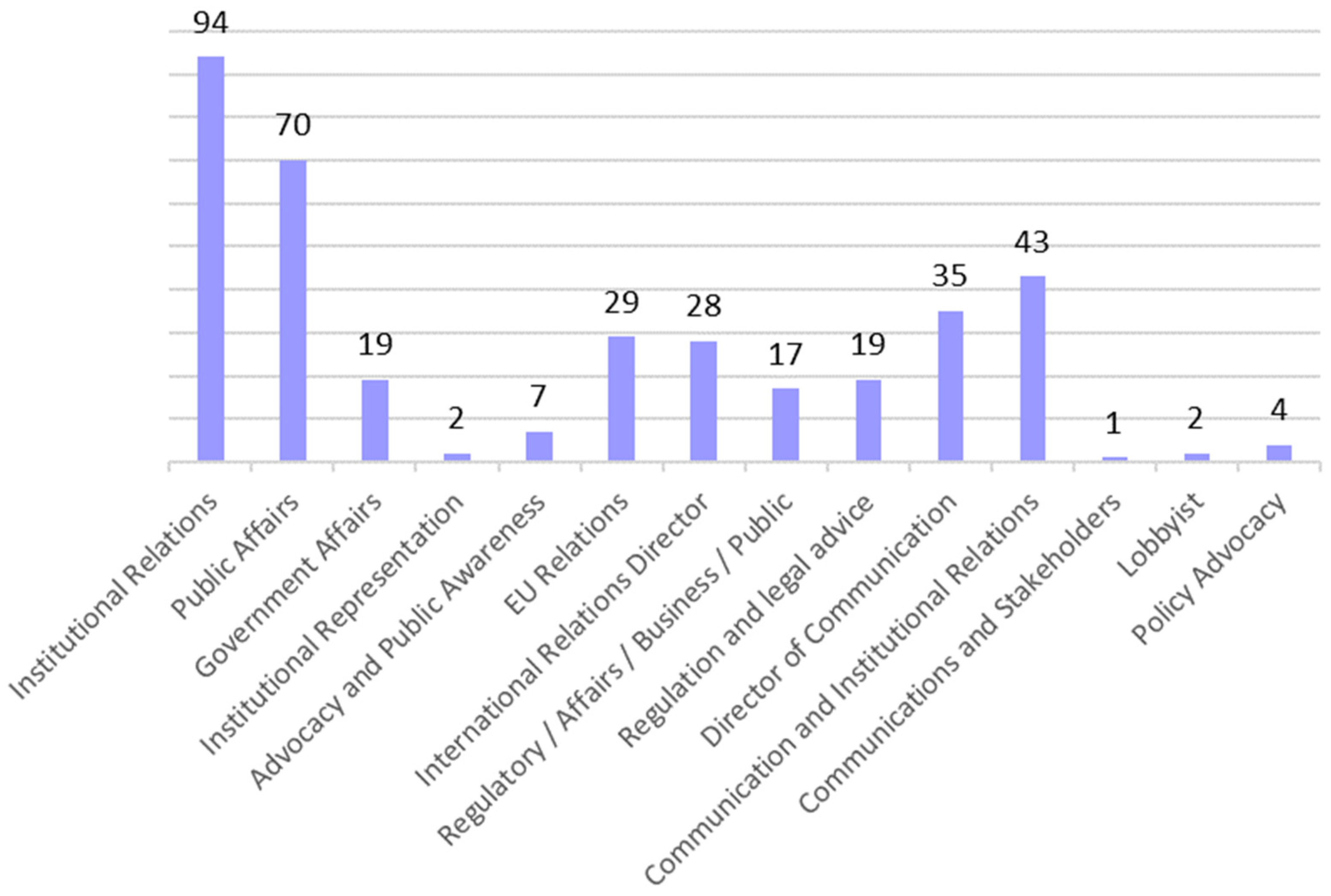

- SO3: to determine the job title of lobbyist and their years of experience in the field.

- SO4: to identify the techniques that are most commonly used in direct lobbying or grassroots lobbying.

3. Results

3.1. Socio-Demographic and Academic Data

3.2. Profiles of Experience and Professional Activity

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Almansa-Martínez, Ana, and Ana B. Fernández-Souto. 2020. Professional Public Relations (PR) trends and challenges. El Profesional de la Información 29: e290303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastasiadis, Stephanos, Moon Jeremy, and Humphreys Michael. 2018. Lobbying and the responsible firm: Agenda-setting for a freshly conceptualized field. Business Ethics. European Review 27: 207–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonucci, Maria C., and Nicola Scocchi. 2018. Codes of conduct and practical recommendations as tools for self-regulation and soft regulation in EU public affairs. Journal Public Affairs 18: 1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arceneaux, Philip. 2018. The public interest behind #JeSuisCharlie and#JeSuisAhmed: Social media and hashtag virality as mechanisms forWestern cultural imperialism. Journal of Public Interest Communication 2: 41–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barron, Andrew, and Lila Skountridaki. 2022. Toward a Professions-Based Understanding of Ethical and Responsible Lobbying. Business & Society 61: 340–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bath, Michael G., Jennifer Gayvert-Owen, and Anthony J. Nownes. 2005. Women Lobbyists: The Gender Gap and Issue Representation. Politics & Policy 33: 136–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benítez, Galia. J. 2018. Business Lobbying: Mapping Policy Networks in Brazil in Mercosur. Social Science 7: 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, Jeffrey. 1977. Lobbying for the People. The Political Behavior of Public Interest Groups. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand, Marianne, Matilde Bombardini, and Francesco Trebbi. 2014. Is It Whom You Know or What You Know? An Empirical Assessment of the Lobbying Process. American Economic Review 104: 3885–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biliouri, Daphne. 1999. Environmental Ngos in Brussels: How powerful are their lobbying activities? Environmental Politics 8: 173–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boucher, Maxime, and Christopher A. Cooper. 2019. Consultant Lobbyists and Public Officials: Selling Policy Expertise or Personal Connections in Canada? Political Studies Review 17: 340–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branton, Regina, Valerie Martínez-Ebers, Tony E. Carey, Jr., and Tetsuya Matsubayashi. 2015. Social Protest and Policy Attitudes: The Case of the 2006 Immigrant Rallies. American Journal of Political Science 59: 390–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bressanelli, Edoardo, Christel Koop, and Christine Reh. 2020. EU actors under pressure: Politicisation and depoliticisation as strategic responses. Journal of European Public Policy 27: 329–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carty, Victoria. 2010. New information communication technologies and grassroots mobilization. Information, Communication & Society 13: 155–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Esparcia, Antonio. 2011. Lobby y Comunicación. Sevilla: Comunicación Social. [Google Scholar]

- Castillo-Esparcia, Antonio. 2020. Asuntos públicos. El lobby como actor político y social. La Revista de ACOP 55: 41–44. Available online: https://cutt.ly/DnWpzO4 (accessed on 14 September 2022).

- Castillo-Esparcia, Antonio, Carmen Carretón-Ballester, and Paula Pineda-Martínez. 2020. Investigación en relaciones públicas en España. Profesional De La información 29: e290330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalmers, Adam W. 2013. Trading information for access: Informational lobbying strategies and interest group access to the European Union. Journal of European Public Policy 20: 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalmers, Adam W. 2020. Unity and Conflict: Explaining Financial Industry Lobbying Success in Shaping Financial Regulation. Regulation & Governance 14: 391–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalmers, Adam W., and Francisco S. Macedo. 2020. Does it pay to lobby? Examining the link between firm lobbying and firm profitability in the European Union. Journal of European Public Policy 28: 1994–2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chari, Raj, and Daniel Hillebrand O’Donovan. 2011. Lobbying the European Commission: Open or Secret? Socialism and Democracy 25: 104–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chari, Raj, Gary Murphy, and John Hogan. 2007. Regulating Lobbyists: A Comparative Analysis of the United States, Canada, Germany and the European Union. The Political Quarterly 78: 422–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crepaz, Michele. 2020. To inform, strategise, collaborate, or compete: What use do lobbyists make of lobby registers? European Political Science Review 12: 347–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, Scott, and Oliver Rowe. 2016. Emerging from the shadows? Perceptions, problems and potential consensus on the functional and civic roles of public affairs practice. Public Relations Inquiry 5: 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bruycker, Iskander. 2016. Pressure and expertise: Explaining the information supply of interest groups in EU legislative lobbying. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 54: 599–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bruycker, Iskander, and Jan Beyers. 2019. Lobbying strategies and success: Inside and outside lobbying in European Union legislative politics. European Political Science Review 11: 57–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dempsey, Sarah. 2009. NGOs, Communicative Labor, and the Work of Grassroots Representation. Communication and Critical/Cultural Studies 6: 328–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dür, Andreas, Patrick Bernhagen, and David Marshall. 2015. Interest Group Success in the European Union: When (and Why) Does Business Lose? Comparative Political Studies 48: 951–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dür, Andreas. 2008. Measuring Interest Group Influence in the EU: A Note on Methodology. European Union Politics 9: 559–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleisher, Craig, and Conor McGrath. 2020. Public Affairs: A field’s maturation from 2000+ to 2030. Journal Public Affairs 20: 2218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galbraith, Jonh K. 1956. American Capitalism—Concept of Countervailing Power. Boston: The Riverside Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher-Cunningham, Kathleen, Marianne Dahl, and Anne Frugé. 2017. Strategies of Resistance: Diversification and Diffusion. American Journal of Political Science 61: 591–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwood, Justin, and Joanna Dreger. 2013. The Transparency Register: A European Vanguard of Strong Lobby Regulation? Interest Groups & Advocacy 2: 139–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junk, Wiebke M., Jeroen Romeijn, and Anne Rasmussen. 2021. Is this a men’s world? On the need to study descriptive representation of women in lobbying and policy advocacy. Journal of European Public Policy 28: 943–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klüver, Heike. 2013. Lobbying in the European Union: Interest Groups, Lobbying Coalitions and Policy Change. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Klüver, Heike, Caelesta Braun, and Jan Beyers. 2015. Legislative lobbying in context: Towards a conceptual framework of interest group lobbying in the European Union. Journal of European Public Policy 22: 447–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korkea-aho, Emilia. 2022. Are lawyer-lobbyists answerable to ‘a higher authority’? Bar association rules as lobbying regulation in the EU and the USA. Interest Groups & Advocacy 11: 569–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labarca, Claudia, Phillip Arceneaux, and Guy J. Golan. 2020. The relationship management function of public affairs officers in Chile: Identifying opportunities and challenges in an emergent market. Journal Public Affairs 20: e2080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaPira, Timothy, Kathleen Marchetti, and Herschel F. Thomas. 2020. Gender Politics in the Lobbying Profession. Politics & Gender 16: 816–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowery, David. 2013. Lobbying Influence: Meaning, Measurement and Missing. Interest Groups & Advocacy 2: 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, Jennifer C., and Mark S. Hyde. 2012. Men and Women Lobbyists in the American States. Social Science Quarterly 93: 394–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, David. 2015. Explaining Interest Group Interactions with Party Group Members in the European Parliament: Dominant Party Groups and Coalition Formation. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 53: 311–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, Conor. 2005. Towards a lobbying profession: Developing the industry’s reputation, education and representation. Journal of Public Affairs 5: 124–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, Conor, Danny Moss, and Phil Harris. 2010. The evolving discipline of public affairs. Journal of Public Affairs 10: 335–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mergeai, Simon, and Henri Gilain. 2020. Analyse comparative des stratégies employées par le lobby pharmaceutique, gazier et automobile visant à influencer les réglementations de l’UE. Louvain: Louvain School of Management, Université Catholique de Louvain. [Google Scholar]

- Milbraith, Lester. 1963. The Washington Lobbyist. Chicago: Rand McNally. [Google Scholar]

- Năstase, Andreea. 2020. An ethics for the lobbying profession? The role of private associations in defining and codifying behavioural standards for lobbyists in the EU. Interest Groups & Advocacy 9: 495–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, Anne. 2015. Participation in Written Government Consultations in Denmark and the UK: System and Actor-level Effects. Government and Opposition 50: 271–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, Anne, Lars K. Mader, and Stefanie Reher. 2018. With a little help from the people? The role of public opinion in advocacy success. Comparative Political Studies 51: 139–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadi, Gabriel, and Marisa R. Meneghetti. 2019. A normative approach on lobbying: Public policies and representations of interests in Argentina. Journal of Public Affairs 20: e1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnakenberg, Keith E. 2017. Informational Lobbying and Legislative Voting. American Journal of Political Science 61: 129–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, Frederick, and Iskander De Bruycker. 2020. Influence, affluence and media salience: Economic resources and lobbying influence in the European Union. European Union Politics 21: 728–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strickland, James M., and Katelyn E. Stauffer. 2022. Legislative Diversity and the Rise of Women Lobbyists. Political Research Quarterly 75: 531–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taminiau, Yvette, and Arnold Wilts. 2006. Corporate lobbying in Europe, managing knowledge and information strategies. Journal of Public Affairs 6: 122–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmermans, Arco. 2020. Bringing science to practice: Designing an integrated academic education program for public affairs. Journal Public Affairs 20: 2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Transparency International. 2015. Lobbying in Europe: Hidden Influence, Privileged, International. Available online: https://www.transparency.org/en/publications/lobbying-in-europe (accessed on 8 June 2022).

- Tworzydło, Dariudz, Przemyslaw Szuba, and Norbert Życzyński. 2019. Profile of public relations practitioners in Poland: Research results. Central European Journal of Communication 12: 361–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyllström, Anna, and John Murray. 2021. Lobbying the client: The role of policy intermediaries in corporate political activity. Organization Studies 42: 971–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilts, Arnold. 2006. Identities and Preferences in Corporate Political Strategizing. Business & Society 45: 441–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woll, Cornelia. 2012. The brash and the soft-spoken: Lobbying styles in a transatlantic comparison. Interest Groups & Advocacy 1: 193–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeigler, Michael A., and Harmon A. Baer. 1969. Lobbying: Interaction and Influence in American State Legislatures. London: Wadsworth Publishing Co. [Google Scholar]

| Professional Activity | Original Job | Most Recent Job | Most Recent Job (Milbraith 1963, p. 68) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Law (private practice) | 16 | 11 | 8 |

| Business | 9 | 11 | 17 |

| Government | 26 | 26 | 57 |

| Journalism | 10 | 2 | 1 |

| Teaching | 6 | 4 | - |

| Religion | 5 | 4 | - |

| Lobbying | 7 | 14 | 2 |

| Arts | 9 | 14 | - |

| Other | 11 | 12 | 15 |

| Age Group | N. º of Lobbyists |

|---|---|

| 20–29 | 12 |

| 30–39 | 72 |

| 40–49 | 152 |

| 50–59 | 106 |

| +60 | 28 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Castillo Esparcia, A.; Moreno Cabanillas, A.; Almansa Martinez, A. Lobbyists in Spain: Professional and Academic Profiles. Soc. Sci. 2023, 12, 250. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12040250

Castillo Esparcia A, Moreno Cabanillas A, Almansa Martinez A. Lobbyists in Spain: Professional and Academic Profiles. Social Sciences. 2023; 12(4):250. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12040250

Chicago/Turabian StyleCastillo Esparcia, Antonio, Andrea Moreno Cabanillas, and Ana Almansa Martinez. 2023. "Lobbyists in Spain: Professional and Academic Profiles" Social Sciences 12, no. 4: 250. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12040250

APA StyleCastillo Esparcia, A., Moreno Cabanillas, A., & Almansa Martinez, A. (2023). Lobbyists in Spain: Professional and Academic Profiles. Social Sciences, 12(4), 250. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12040250