Abstract

The COVID crisis has disrupted routine patterns and practices across all spheres of everyday life, rupturing social relations and destabilising our capacity for building coherent selves and communities by recollecting the past and imagining potential futures. Education is a key domain in which these hopes for the future have been dashed for many young people and in which commitments to critical scholarship and pedagogies are being contested. In a world of stark socioeconomic inequality, racism, and other forms of dehumanising othering, the pandemic serves not to disrupt narratives of meritocracy and progress but to expose them as the myths they have always been. This paper will explore forms of political resistance and the (im)possibilities for experimental pedagogies in response to the broken promises and unrealised dreams of (higher) education in the context of the COVID crisis. Reflecting on my own everyday life as a scholar and educator in a South African university, and in dialogue with students’ narratives of experience, I will examine the ways in which the experience of the pandemic has released and mobilised new forms of resistance to historical institutional and pedagogical practices. However, these hopeful threads of alternative narratives are fragile, improvised in the weighty conditions of a status quo resistant to change, and in which the alienation and inequality of the terrain are being exacerbated and deepened through a proliferation of bureaucratic and technicist solutions.

Keywords:

narrative; hope; pandemic; higher education; South Africa; inequality; political protest; imagination 1. Introduction: The Rupture of the Pandemic

For every generation of children learning to read, write and do arithmetic, for every generation of students of physics, philosophy, or psychology, education is a domain of possibility oriented towards the future. These are Vygotsky’s (1978) “zones of proximal development”, zones of potential yet to be realized. The trajectories of education are typically framed as a process of growing up and into existing adult roles and culturally patterned practices of knowledge-making and work, through the progressive accumulation of cultural capital (Bourdieu 1986). These currents of the “narrative unconscious” (Freeman 2010) that join us to collective cultural history, enable creative development (or “progress”) but simultaneously carry traumatic historical effects into the present. However, as much as activities in classrooms, in families, and in the world of work are mediated by the past, the horizon of imagined futures provides the other fluctuating reference point for present action and thought. Psychosocial life, particularly the intersubjective processes of learning, oscillates back-and-forth in ways that make both past and future coalesce (or possibly collide) in the present. This capacity to “time-travel” (Andrews 2014) is constructed across the temporal and spatial distances opened-up by language and extended in text, and all teaching-learning entails these psychic journeys across time and space. Our present subjectivity is thus motile and mutable, infused simultaneously with memory and imagination. The articulation of the past and the future renders education ambivalently potentially oppressive and liberating. In the context of higher education in South Africa, these antithetical impulses are starkly racialised and intertwined with historical inequalities perpetuated in the present. Traversing this contested terrain, therefore, requires resilience, perseverance, and resistance enacted in multiple forms, in overt political action directed at systemic change, and in the micropolitics of interpersonal interaction in learning-teaching. This article is primarily focused on the everyday spaces of classrooms (virtual and ‘real’) and the ways in which the covid crisis reshapes possibilities for resistance and change, and for imagining futures different from the past.

The advent of the pandemic radically disrupted our taken-for-granted patterns of daily life and pedagogical practices and, in our initial shock at having landed in a science fiction future, there were tentative hopes that the global crisis might be a forceful impetus towards alternative forms of social life, leading us to take better care of the earth and one another. Some even ventured that the impossible (in the very best sense) might have “already happened” (Solnit 2020). Arundhati Roy wrote a remarkable piece that has already become a touchstone classic, framing the pandemic as a “portal, a gateway between one world and the next.” She captures the agitated, psychic activity that accompanied the slowing down of public social life, and the possibilities that the moment seemed to pose:

“Our minds are still racing back and forth, longing for a return to “normality”, trying to stitch our future to our past and refusing to acknowledge the rupture. … [The pandemic] is a portal, a gateway between one world and the next. We can choose to walk through it, dragging the carcasses of our prejudice and hatred, our avarice, our data banks, and dead ideas, our dead rivers and smoky skies behind us. Or we can walk through lightly, with little luggage, ready to imagine another world”.(Roy 2020)

However, these provocations of creativity and reimagination coalesced with anxious attempts to realign these strange and estranging conditions with the world as we knew it, and strategies of containment and control were quickly mobilised to sustain and reassert structural hierarchies. Little more than a year passed before Roy (2021) wrote another reflection on the devastating impact of the pandemic on her home country, India, where the scintillas of more hopeful alternatives were occluded. Across the world, it became clear that “[t]hose who benefit most from the shattered status quo are often more focused on preserving or re-establishing it than protecting human life” (Solnit 2020). On this rocky ground, the poor once again become collateral damage in the scramble to consolidate and shore up the dysfunctional asymmetrical frameworks of social life.

The specific context of higher education in South Africa mirrored these global developments with an initial surge of hope that the pandemic might offer the potential for remaking the practices of learning-teaching in more humane and equal ways and towards the construction of a more just world. However, even small cracks in the edifice of the status quo were met with institutional resistance to change and anxious, defensive strategies, despite the widespread recognition that higher education was already in deep trouble, struggling with epistemic tensions and ethical questions in a world of economic austerity and deepening inequality. My narrative as a teacher is told in dialogue with the stories of students, with the textual traditions of narrative and other psychosocial theories, in interdisciplinary creative conversation with colleagues, and with voices from remarkable real-time political and social commentary in the global media space. This approach instantiates one of the primary provocations of the pandemic to my pedagogical practice: to render the boundaries between sources of knowledge and forms of knowledge-making, between theory and practice, between learning and living, more porous. The macro-politics of the global crisis are here concentrated in a seemingly insignificant educational space, framing the (im)possibilities for resistance in the “multiple micropolitical practices of daily activism or interventions in and on the world we inhabit … in tune with the present but resisting its murderous tendencies” (Braidotti 2010, p. 423).

2. Resistance and Decolonization: The Crisis beyond the Pandemic

Higher education is a hopeful domain for collective change and individual social mobility, the time and space for the development of thinking and practice to prepare for individual working lives, and for collective enquiry into past and present realities in the construction of future worlds. In the extended years of study required for entry into the workplace, young people accumulate forms of “cultural capital” in its embodied, objectified, and institutional forms (Bourdieu 1986). However, access to this domain of education with its aspirational promise of social mobility is largely predetermined by prior forms of cultural capital acquired through the socialisation practices of schooling and families. The apartheid state understood the critical role of education in relation to participation in the economy and it was, therefore, an extremely important sector for the implementation of structural racism. With democratisation, increasing numbers of black students are enrolled for study, many first-generation students from families oppressed by the racist regime of the past. However, these transformational gains happen within more intransigent structural constraints as higher education is steeped in colonial history and implicated in contemporary unequal socioeconomic formations.

The uprising of the 2015/2016 Student Movement was a response to the disjuncture between the rhetoric of deracialised, open access to higher education, and the persistent exclusionary effects of socioeconomic inequality and epistemic violence. In a context of perpetual and deepening inequality, higher education becomes a conduit for perpetuating intergenerational privilege and the task of teaching becomes narrowly defined as ensuring the transmission of information and skills for participation in the higher echelons of the world of work. The possible forms of participation in knowledge production are pre-empted by the ways in which individual and collective imagination are channelled by the forces of history and the potentially emancipatory effects of learning are tamed and contained in a disciplinary and disciplining project that creates ‘docile bodies’ (Foucault 1988; Burman 2017). While this analysis applies to the linkages between education and the socio-economic organisation of all societies in the global order of late capitalism, in South Africa, class continues to be inflected by race and the flows of power in contemporary global and local dynamics.

The triumphant toppling of the Rhodes statue on the campus of the University of Cape Town early in 2015 was emblematic of long-standing demands for decolonisation, precipitating calls for another statue of Rhodes at Oriel College, Oxford to fall. Further acts of what Marvin Rees, the mayor of Bristol termed ‘historical poetry’ (Morris 2020) removed similar symbolic concretisations of colonialism and imperial conquest such as the statue of the slave-trader Edward Colston which was dumped into the Bristol canal. In addition to providing this impetus for resistance on the symbolic front elsewhere, the South African Student movement articulated the links between epistemic and material injustices, and between the colonial past and active currents of racism in the present (particularly as confronted by the resurgence of BLM in 2021 in the wake of George Floyd’s murder). #FeesMustFall followed hot on the heels of #RhodesMustFall and significant gains were made for poor and working-class students. Loans from the National Student Financial Aid Scheme (NSFAS) were converted to grants and eligibility was extended to include the so-called “missing middle”. Solidarity with and from workers (cleaners, gardeners, and service providers) on university campuses brought an end to the iniquitous practice of outsourcing labour on many campuses (Motimele 2019). However, this struggle is far from over. Access to universities remains financially prohibitive and the burden of debt created by long years of study remains high for most students and their families. At the postgraduate level, we continue to cling to antiquated mythical notions of merit defined by raw scores, distributing funding in unfair and inaccurate ways that affect the present and future scholarship.

Against this recent history, the pandemic had devastating effects on an already struggling economy, swelling the burgeoning unemployment figures (according to recent stats, 34.9% or 46.6% on the expanded definition, with a shocking figure of 66.5% of youth unemployed). Glimpses of possibility lay in the surfacing of more serious mainstream consideration being given to proposals for a wealth tax and a universal basic income grant that had long been dismissed as unrealistic. However, there were no signs of such economic recalibration in the recently delivered national budget speech of 2022. Economists from the Institute for Economic Justice (among others) have again questioned the political line that these measures are unaffordable on both ethical and rational grounds (Mncube 2022). The events of July 2021 in which more than 300 people were murdered in racist vigilante-style killings amidst widescale looting of shops and destruction of property make very clear that what we most certainly cannot afford is the perpetual failure of the state to address inequality and poverty. In higher education, these inequalities give lie to the myth of meritocracy and the crisis in student funding is a recurring nightmare exploding into consciousness at the start of each academic year. Writing before the pandemic, Motimele’s (2019) analysis of the student movement critiques the pervasive effects of ‘neoliberal time’ in the commodification of higher education.

“Yet, the true rupture presented by the unified activism of students and workers was in the critique they presented of a neoliberalized university, hierarchical bureaucratic structures, an institutional culture still defined by whiteness, and dominant epistemological paradigms that foreclosed the possibility for an indigenous intellectual project. … the universities’ insistence on the conclusion of the academic program (curriculum-time), the need to balance university financial books (capitalist-time), and the obsession with research output and student throughput (production-time) are all expressions of the dominance of neoliberal-time”.(Motimele 2019, p. 205)

The idea of the university as a public good, the equivalent of the democratic commons at the heart of society, is being eroded. The extensive privatisation of schooling in South Africa has widened the inequalities that were crudely racialised under apartheid. Universities, while still mostly ostensibly public, are in effect semi-privatised through fee structures. Despite the complex financial aid schemes that the state has established, primarily in response to the demands of #FMF, the effects of financial exclusion are extensive throughout the system, commodifying academic work (both research and teaching) in ‘business units’ that must perform competitively in the relentless march of neoliberal time (Motimele 2019). A recent newspaper article written by colleagues from the School of Education questions the university’s current slogan for its centenary year, “Wits for Good”, asking “For whose good, exactly?” (Ramoupi et al. 2021). Access to this ‘good’ is increasingly restricted the higher up the educational ladder one climbs. Higher education (particularly in highly select professional fields such as medicine, law, or psychology) resembles a giant pyramid scheme in which the investment of many delivers results for only a ‘lucky’ few. The myth of meritocracy generates what Lauren Berlant (2011, p. 1) describes as ‘cruel optimism’ in that what “you desire is actually an obstacle to your flourishing”. The forms of life that characterise late capitalism and are infused in the practices of education, promise possibilities for this flourishing, “by the incoherence with which alienation is lived as exhaustion plus saturating intensity” (Berlant 2011, p. 166). These dehumanising conditions of life and learning are resisted in the logics of rage and despair as expressions of hope that the world might be differently organised (Canham 2018; Bradbury 2020). In 2021, student protests against financial exclusion were displaced into the streets of Johannesburg by the convergence of covid regulations and the refusal of university management to grant permission for protest action on campus. A member of the public, Mthokozisi Ntumba, was shot dead by police who opened fire on protesting students.

3. Resistance, Resilience, and Retreats in the COVID Crisis

It is evident that the crisis of the pandemic has been played out on a historical landscape littered with crises. However, the particular form of this disruption to our taken-for-granted practices created an immediate imperative to loosen our fixation with the established content, form, and processes of higher education in urgent and accelerated ways. This primarily entailed an uneven and rapid rollout of online learning in what was self-deprecatingly termed ‘remote emergency’ mode. In addition to widely disparate institutional resources (both human and material) across the sector, even within the most privileged institutions, there are serious inequalities across the student body making this emergency far more disastrous for some than others. These differential impacts are embedded in precarious and crowded living conditions, uneven connectivity, excessively high data costs, for some, no computing devices, and for many, no reliable electricity supply.

In addition to these unequal parameters in the material and virtual worlds, there are moreover specific pedagogical problems that are our proper responsibility as teachers. There is little lost and perhaps something to be gained by transferring large class lectures to online asynchronous delivery, enabling students to watch and listen when they want with the added advantage of being able to fast forward through bits that are familiar or just boring or to replay sections that are unclear or difficult to grasp the first time around. Students have, in any case, long known this, asking friends or sometimes lecturers to record live lectures and it is an open secret that attendance at lectures was abysmally low before the pandemic terminated this particular form of mass communication. Nonetheless, writing before the pandemic, I expressed a prescient nervousness about the contradictory impact of the increasing range of the virtual world and the erosion of face-to-face interactions in education and other domains of social life:

“The explosion of information and the acceleration of communication across geographical, cultural, linguistic and other boundaries has empowering effects and, regardless, it is impossible for those of us in it to reimagine an existence without this dimension of the world. However, perhaps because I am not a digital native, I would argue that this virtual world can supplement but not supplant embodied face-to-face interaction in the space of the therapeutic room, in the classroom, in political gatherings or live performances, across family dining room tables and over coffee or wine with friends”.(Bradbury 2020, p. 168)

In its most hopeful articulations, the virtual world might serve to make the boundaries of universities porous, democratising access to knowledge and relational networks of meaning-making. However, it also extends new forms of imperialism and homogenising narratives, replicating the unequal architecture of the material world. The isolation of covid conditions was certainly mitigated by technology but these technical and technicist solutions to the ‘uncontrollability’ (Rosa 2020) of the situation, were not only unevenly available but also generated further anxious forms of alienation and loss.

Those of us who have been teaching for a long time know the experience of engaging with a new cohort of students with whom we may be reading and talking about texts that we have read many times before, alone or with other groups. Yet, something new emerges. Learning-teaching is a living process that emerges in the dialogical exchange between particular persons who bring their own life histories into the room and the dynamics between students are as important as between the lecturer and learners. Even when the virtual classroom allows for interactive exchange, this is typically dyadic between the teacher and a particular student who raises a question or poses a problem, atomising and further individuating learners. Masha Gessen (2020) says, “… we can’t look one another in the eye, we can’t read facial expressions, we are intensely and fruitlessly aware of performing, and we cannot reconcile our words, intentions, and environment.” By analogy, we all know that while a live musical performance may be less perfect than a recording, the atmospheric experience for both listeners and artists is different in kind, decentring us in relation both to the music and to the other members of the audience, enhancing the power of the work to reveal new senses of the world and ourselves. Embodied experience is always multi-modal, involving all our senses, living and breathing in relation to others and, where the purposes of the gathering in place are expressly didactic, the nuances of these multiple interactions are exponentially valuable. The best classrooms entail much more than unidirectional instruction or dyadic exchange and in contexts such as South Africa where classes are very diverse, learning from other students is as critical as learning from texts and teachers. Of course, such interaction between students is possible online and the prevalence of social media means that this mode of interaction, particularly for young people, predated the pandemic. There is much to be said for the promise of these spaces that escape the strictures of physical space and the imposition of teachers’ structuring. However, paradoxically these spaces have divisive effects too, not only because participation in them requires resources such as smartphones and data, but also because these spaces may often become little more than echo-chambers or, where contestation does occur, it is quick and dirty with a focus on closing down rather than opening up debates. In addition, the commodification of knowledge is intensified rather than reduced in virtual space, most notably in the proliferation of essay mills and similar sites offering shortcuts to credits.

In language that resonates with Levinas’s (1963) notion of “face”, Brabazon suggests that the humanising potential of education is lost or at least undermined by the loss of embodied encounters:

“Education is also a humanising experience “that involves questioning and altering one’s sense of self and one’s relationship to others. Humans learn through narrative, context, empathy, debate, and shared experiences. We are able to open ourselves up enough to ask difficult questions and allow ourselves to be challenged only when we are able to see the humanity in others and when our own humanity is recognised by others.”.(Brabazon 2021)

4. Everyday Academic Life: Learning-Teaching in the Pandemic

To illustrate the impact of the pandemic on the everyday worlds of teaching and learning in a more granular way, I will focus on tasks redesigned and engaged within the peculiarly accelerated and slow-motion zone when the pandemic first hit in March 2020. My honours course, “narratives of youth identities”, began on campus with face-to-face seminars where I confronted the usual challenges of working with a large, diverse group of students, all anxious right from the get-go about the competitive filtering of the year that would determine who would attain the extremely limited desired placement in psychology master’s programmes. It was a great group, highly engaged with one another, the texts, and with me, and I was experiencing my usual adrenal rush in meeting new young people on the cusp of their promising adult futures. Six weeks into the academic year, in a frenzied rush, students were evicted from university residences and all of us were barred from campus and sent home for the initial three-week strict lockdown period when we could not leave our houses at all. For some students, these homes were the places from which they had been on a daily commute to campus, but many departed to more distant places elsewhere across the country. This was a moment “full of both the best and worst possibilities. We [were] both becalmed and in a state of profound change” (Solnit 2020).

Home is usually understood as a place of retreat from the world for relaxation and rejuvenation, the place where we can let our defences down and be most freely ourselves. Those whom we trust to enter our most personal space are invited to “make yourselves at home.” By contrast, university space is experienced by many students, particularly black students, as alienating and inhospitable (Bradbury and Kiguwa 2012). However, the characterisation of these spaces in these contrasting binary terms is an oversimplification. University life also provides an escape from family life and, while the encounter with new ideas and practices may feel threatening, it also provokes possibilities for reimagining selves and worlds. Homes may also, for many people, particularly women, not be places of safety and support. To illustrate, like many women all over the world, psychology honours student, Zandile Ndongeni’s1 move back home meant that she had to juggle mothering and household responsibilities on a daily basis as she completed her tasks for the course.

I was in my room trying to study online during the day. My daughter was banging on my door because she and her cousin-brother were fighting about which cartoon channels to watch. … She was crying because her cousin-brother bit her hand for the TV remote control. I decided to put her on my back so that I can continue with my schoolwork as there was no one else in the house to calm her down. This lockdown has made me realise how difficult it is to balance being a student and a mother. This struggle has always been there, but it intensified even more since the lockdown.

Disorientated and without our usual physical and psychological bearings, it was simply unimaginable that this strange life would morph along with viral mutations in long, rolling waves for years to come, and initially, the academic programme was paused in an early, slightly extended first quarter break. However, our blank computer screens were soon flooded with instructions to get the academic year “back on track”. Increasing levels of surveillance over the previous few years subsequent to #Feesmustfall had been only weakly resisted by students and staff with fairly quick capitulation to mechanisms such as fingerprint access to the public space of the campus. With the move to online learning, the tentacles of bureaucratic control extended beyond the restricted zone of campus and into the private space of our homes and into the personal time of evenings and weekends. The effect was to automate the educational domain, undercutting decades of experience in classrooms and in academic fields of expertise. In relation to content, we were instructed to cut anything superfluous. This may have productive value and it was indeed remarkable to see how colleagues who have clung to ostensibly essential components found it possible to finally let some things go, things that were superfluous all along. Particularly for undergraduate students, content, which is, in any case, quickly forgotten (Miller et al. 1999), is far less important than learning the methods and forms of academic practice and so the need to pay greater attention to what it is that students need to know at different levels could be pedagogically productive and potentially challenge colonial disciplinary canons. With one caveat: this narrowing of focus is accompanied by stricter time frames and distance creates the need for increased specificity and clear instructions for independent activity. We do need to provide road maps for reading as we already know all too well that access to amassing piles of internet information does not translate into better thinking and writing. However, tightening the connections between reading and assessment funnels students down narrow pathways of material that is essential, not for life or for critical enquiry, but for examination to ensure that course metrics are unaffected by any disruptive alterations to pedagogy and curricula. Where answers are unknown not only to students but to teachers too, the world of university study and research is better navigated in more exploratory open-ended ways.

In the honours course, we continued to read and talk about narrative theory although I did reduce the amount of reading and cut some seminars altogether. These adjustments were not out of concern about remaining on track and I did not concede that the volume of reading that I had initially prescribed was excessive. However, I recognised both the difficulties with sustained concentration and the more pressing concerns of life that diverted our energies and attention—mine as much as those of students! Not all the effects of this devastating crisis were negative. One enormous benefit of the virtual zoom-room was that I was able to invite international scholars, Molly Andrews, Corinne Squire, and Ann Phoenix, whose work we were reading, to join the class for guest seminars. In 2021, my master’s class was able to attend a conference ‘in Finland’ at the invitation of Erica Burman who was delivering a keynote address. These generous exchanges were invigorating for students, enabling connections between research and teaching, and providing access to intellectual forums that would have been beyond reach in-person.

The key shift in my pedagogical approach was to foreground and enhance the creative and exploratory tasks that had always been part of the course: narrative interviewing and reflexive personal narratives. These tasks provided a forum for reflexivity and intergenerational work and were paradoxically creatively enhanced by the conditions of lockdown through proximity to family members and introspective time and space. Students interviewed their grandparents in person in multi-generational households or over the phone, or with their parents about their grandparents’ lives. Living at home and living only at home and working mainly online provided scope for creative and multi-modal reflexive narratives, with the class producing between them a largescale painting, dance performances, musical playlists, and video/photographic essays. While I have been incorporating visual methods in my research practice for a long while (see, for example, Bradbury 2017; Bradbury and Kiguwa 2012), facilitating the making of knowledge in this way had not been an explicit part of my teaching praxis. The objects produced were quite remarkable, creative, and innovative, playing to individual strengths and utilising forms of meaning-making that were unfamiliar to me both because they lie outside of my disciplinary expertise and because of generational leaps in technology. The tasks criss-cross the boundaries of theoretical study and life experience, private and public worlds, connecting the past and present. Responsive teaching of this kind, increasing the scope of tasks and the weighting of this kind of evaluation of learning, is typically discouraged in a context of increasing commodification of education, where rigid templates for content and form are required in advance and must be spelt out in detail. Institutional resistance to learning means that while the pandemic temporarily loosened such mechanisms of control and surveillance, these have congealed in enhanced bureaucratic systems that are perhaps even easier to enforce through the permanent traces of the virtual terrain than in the ephemeral happenings of real-world events.

5. Communities of Praxis

Alongside my virtual classrooms, I was participating in multiple online groups focused on socio-political questions, some specifically related to higher education such as perpetual battles with student funding, but others more general, engaging with PPE scandals, vaccination hoarding, austerity measures, poverty, and unemployment, violent policing, and Black Lives Matter. However, one forum that proved both therapeutic and creative for my educational praxis had a less explicitly political agenda. A colleague from anthropology invited me to join a loose collaborative group of academics across multiple disciplines (anthropology, history, law, psychology), and from three different South African universities, ranging from people in relatively senior academic management roles to young early-career scholars. We gathered virtually, sharing information about the virus, trying to make sense of fluid data that did not fit any of our existing frameworks, sometimes reflecting on wider socio-political issues affecting all of us, sometimes discussing specific teaching and learning issues but mostly, we just talked, often for a few rambling hours at the end of the day before or while making supper, almost like old friends despite the fact that we were mostly strangers who had never met in the flesh. We swapped stories about institutional struggles, of contraband cigarettes, or whined about the lack of wine in our fridges, we talked about food and music and growing things, about new or revived craft activities, and shared worries about students and family members who were vulnerable to both physical infection and the rampant contagion of mental health troubles. We laughed a lot.

The kind of support we provided each other was shaped by the particular combination of intimacy and distance, different from the personal circles of family and friendship but also quite different from institutional offers of helplines and online counselling or the multiple surveys we were enjoined to complete to assess the wellbeing of staff. I can only imagine that my wariness around these official channels and platforms was possibly more acute for students (who know that the same institutional structures will evaluate their success or failure) and can only hope that students were able to coalesce in similar protective and resistant forums. However, I also know that many colleagues and students were not so fortunate and had to develop individual resilience in isolation. This unstructured space provided essential support to resist the impact of frenetic and anxious virtual institutional meetings in which keeping the academic programme “on track” was the overriding concern. A WhatsApp exchange between three of us on a Sunday morning triggered nostalgic childhood memories and encouraged a more creative formulation of the reflexive narrative task for my students along the lines of the memory box project of the late 1990s/early 2000s at the height of the Aids pandemic (see, for example, Denis 2005).

- Zimitri:

- Morning friends. A beautiful morning here in Jozi. I’ve started a box into which I put objects of my Corona life.

- Pia:

- Did you make that box yourself? It’s beautiful 😊 if it is a memory-style box, I’ll crochet you a unicorn to add. To remind you of our conversation and space

- Zimitri:

- The box came to me last year from my Dan on Valentine’s Day. It was filled with lovely things…. I would love that, Pia! Thank you. Exactly… like a memory box.

- Pia:

- Great, I thought of making us each one, appropriating Charm’s totem and creating an object to remind us that we were able to make a magical space amidst this messiness.

- Zimitri:

- The plate you see is my neighbour’s. When either one of us cooks a delicious meal we prepare a generous plate for the other. Pass it through or over the fence. When I was a baby and my mother started working, she would wrap me up and pass me over the wood ‘n iron fence to our neighbour. She was Mrs Pearce. Will send you the chapter of my book…if you don’t have my book.3 I want to ask my neighbour if I can keep that plate? How else to make it part of my box? Just a picture?

- Pia:

- Plate is beautiful. Message is meaningful. I’m sure your neighbour will happily gift it. Passing food over the fence is a generous gift

- Zimitri:

- Wow! When we think together! The beauty that emerges!

- Jill:

- Thank you for this wonderful Sunday morning visual conversation!

- Pia:

- Jill, you should dry one of your pansies. Or more than one, and make us each a card.

- Jill:

- I have designed a task for my honours class (narratives of youth identities) to create a narrative diary of life under lockdown and have suggested they use whatever modality they wish … sound, visual, or written … could I send these images as an example?

- Zimitri:

- Of course!

- Jill:

- thanks! … Ah! Pressed dried flowers … I had forgotten. My Mom and I used to do this when I was a kid…

- Pia:

- Yes of course. I love pansies, and often grow them. But in future, they will remind me of you, what a lovely gift to have you in my garden

- Zimitri:

- Yes. I am going to find stuff on pansies and will share. Pensiere4… is that how you spell it, Pia?

- Jill:

- You have both soooooo cheered me up this morning! Have a beautiful day.

This conversation ranges across time and space, narrating childhood stories of mothers, incorporating our memories of the earlier pandemic and its devastation, but simultaneously alive to our active narration and memory-making in the present that we were experiencing as simultaneously exceptional and quotidian. These simple, meandering conversations may be read as forms of resistance to the pressure to conform to the shrinking space and time of digital meeting rooms, facilitating creativity and linking personal meaning-making with public forms of knowledge construction.

6. A Narrative of Three Generations of Women: Reflecting in the Mess

On the back of this conversation, I re-conceptualised the reflexive narrative task for my honours course. The individual story of Fezeka Hlophe in dialogue with her mother’s and grandmother’s stories as told through her own narrative version of the memory box or time-capsule illustrates how the task enabled her to make sense of the entangled threads of loss and hope in the experience of everyday life in the time of COVID. Fezeka records in her diary:

“Today the one thing I was dreading happened. We received news that my mom unfortunately got retrenched. … Today is Sunday so Ma made the typical Sunday dinner. Earlier we both took a walk to the local vendor get pumpkin. During the walk, Ma told me about how serious she was about her education. She studied extra hard when she was around my age so she could live a good life and she could not have imagined that her life would turn out the way it has. … It really pains me when she talks like this, and it wasn’t the first time I heard this from her. This makes me question life … How can someone who is a hard worker, someone who does everything by the book suffer like this? When will she get a steady income? A good reliable job so she can have peace.”

Unemployment statistics and large-scale job losses due to the pandemic are given a face in Fezeka’s story, and the despair about the lost promises of education in her mother’s life resonates anxiously in the context of her own studies. In this same week, the family lost their (grand)mother and she describes the mourning rituals happening in parallel with everyday life under lockdown.

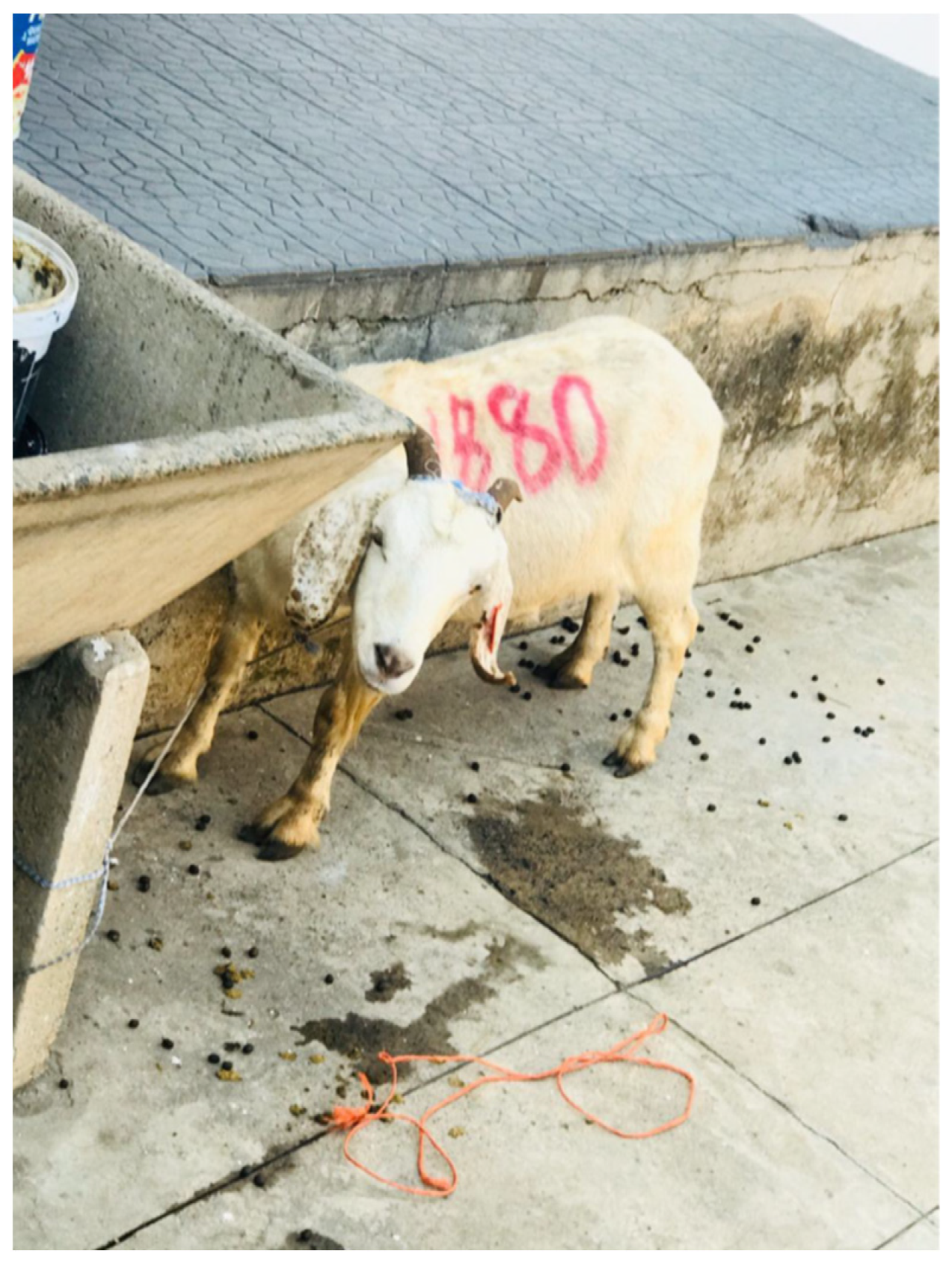

Today my uncle, brothers and I bought a goat that will be needed for the ceremony. This cleansing ritual strictly requires a white female goat. Me, not knowing anything about my culture and using this opportunity to learn more, I asked my mom why this was so and she replied that the goat needs to be female because the person we lost in our family is female. She then continued to explain that the coat of the goat has to be white because white symbolizes purity and cleanliness which is what we will need to wash away the darkness caused by death. This picture shows the goat that we bought.

The story of the goat tells of loss and connection across generations. Although she professes her ignorance, she is probably also explaining these cultural practices to me, opening a window into her world that would ordinarily lie outside of my experience and outside of classroom discussion. After the funeral, she writes an extraordinarily hopeful entry.

Today I felt hopeful for the future also considering that everything went well… so I wanted to express that by being yellow… I am not artistic at all lol but anyway to me bright yellow signifies happiness, joy, and of course brightness…. So, I wore a yellow top and made sure to include yellow when I did my makeup as shown by the picture below.

In a moving juxtaposition of hope and loss, of youth and old age, she photographs her grandmother’s sister (above) whom she calls ‘granny-aunt’ despite the fact that this irritates the older lady.

What saddens me is that while I was taking pictures of her one of my aunts and my mom encouraged me saying ‘we might need them one day’ which implies that we may need them for her obituary. She is old and during the funeral of my late gran she called all of us into the room and she pleaded with my aunts to help bury her when the time comes because she has three children and only one is currently working. … Well, typing this is making me go back to our conversations during the time of the funeral where she told me that she would wish to go, sleeping, when no one is in the house. Like how do you live knowing your death is near … even practically preparing for it? Ai, anyway I will enjoy her while I still have her and appreciate her and the guidance she gives us, ’cause she is the only elder we as a family have left.

7. Intergenerational Dialogues in a Landscape of Loss

The interviews provide poignant insight into intimate, tender exchanges between young people and their (grand) parents, telling quotidian stories of growing grapevines or roses, sailing boats or fixing cars, of beloved barking dogs, of walking to school along dusty pathways, sharing favourite recipes and foods, cooking on fires and studying by candlelight. In some cases, these everyday narratives were punctuated by more dramatic turning points, revealing family secrets of love affairs, the loss of babies, or violent child abuse. These family histories coincided with the conflictual decades of apartheid and the stories of black grandparents were often explicitly marked by forced removals and involuntary migration from rural to urban places, exiles, and family separations, truncated and interrupted schooling, and experiences of brutal political violence. Since these intergenerational stories end in the present, in the lives of the students who conducted the interviews, they are also stories of resistance and resilience. However, these more hopeful interpretations of family trajectories are tentative and provisional, challenged by current crises of inequality, austerity, and racism, exacerbated by the pandemic, which make it difficult to read these narratives only in terms of agency and overcoming.

Fezeka Hlophe, whose mother lost her job and her own mother (Fezeka’s grandmother) during the time of the interview, expresses her gratitude and awareness of the strain on her mother’s life. Mother and daughter collaborate on the task in the shared wish for her to “do well”.

- Fezeka:

- Mm Ok. Oh, okay thank you, thank you so much Ma for giving me your time to do this interview because I know that you are tired and you’ve just had a back and forth from Free State and you already said you are tired so thank you for umm giving me this time that I need to do my task.

- Mum:

- [laughs softly].

- Fezeka:

- Yeah, [laughing softly].

- Mum:

- Okay, I am tired, very tired but I’m happy to, to help you with this task of yours because I want so much for you to…

- Fezeka:

- To do well …

- Mum:

- To, to do well.

- Fezeka:

- Okay Ma thank you, thank you.

Robyn Brand’s grandfather expressed a similar investment in his granddaughter’s success. This conversation was the last time they spoke as he died shortly thereafter. In the interview, perhaps with unconscious urgency, he shared very traumatic childhood memories with her, leaving this precious record for her memory.

- Robyn:

- Ja, flip, Right Grandpa, I’m going it there for tonight if that’s ok with you.

- Grandpa:

- And I hope that was a bit of help, Robs. I don’t know.

- Robyn:

- Ja, thank you. Thank you so, so much Grandpa

- Grandpa:

- You, you probably failed the test anyway …

- Robyn:

- [laughs]

- Grandpa:

- … Talking, talking to an old fart like me.

- Robyn:

- No man. It’s so interesting getting to like know your life-story a bit better. … Ja, no, thank you so much for like letting me like … well, sharing your life with me if I could say that.

- Grandpa:

- Er, ja well, as I say, I don’t … I don’t often do it with anyone but if it can help you, then I’m happy with that.

- Robyn:

- [laughs] Thanks Grandpa.

- Grandpa:

- Ok then honey.

- Robyn:

- Sleep tight.

- Grandpa:

- Ok, we’ll keep in touch.

Redirecting the focus of academic tasks into the familial context of home enabled relational intergenerational learning in poignant intimate exchanges, emotionally concentrated by the context of collective grief and loss, expressing tender mutuality. The question is whether these fragile links between home and the academy can continue to be strengthened once we return to campus. Theoretical enquiry should enable students to reflect on their everyday lives and relationships in new ways and forms of meaning-making that are typically excluded from classrooms and have the potential to enliven and invigorate academic exchange.

Working with students in their homes from my own home created a strange new transparency between our personal lives that is typically mediated by the public space of the campus. The atomisation of distance and isolation paradoxically provoked greater attention to the worlds of students and altered the tone and texture of our engagements. To teach with an eye only on the hopeful future without attending to repetitive cycles of grief in the present became untenable under the conditions of the covid crisis and as a teacher, I was provoked by the challenge issued by the philosopher Agnes Callard:

“Now is an apt time to ponder the fact that the human condition means living under the shadow of death. It is an apt time to situate the present in the broad sweep of history. Deprived of the reality of human connection, we are at least in a position to appreciate the idea of it. And, given that many of us are teachers, we should also be able to communicate this to others—to offer them a way out of numbness and anxiety”.(Callard 2020)

In some cases, grief and loss were very close to home: one of the students lost her grandmother in the weeks before the interview and another lost her grandfather a few months after the interview. These were not covid losses, but many subsequently were, and the terrain of teaching-learning became wracked with loss and grief. In 2021, a student in my honours class lost five family members to covid in a matter of months. Several colleagues suffered similar inconceivable family losses; the academy lost several leading scholars, including my beloved friend and closest research partner, Bhekizizwe Peterson. While death is always a part of the natural flow of life, the pervasiveness of grief and loss during the pandemic has often meant that multiple people are suffering such losses simultaneously. These waves of collective loss in the strange isolation and disconnection of Covid deeply unsettled the ordinary world of teaching-learning. However, as Peterson himself was always conscious, the “individual and social presence of melancholia” (Peterson 2019, p. 360) is not a new aberration but rather, continues to rearticulate traumatic history in what he hauntingly referred to as “black spectrality”. Perhaps these are the conditions under which we were always working, but the pandemic surfaced these surging flows of black death and mourning (Canham 2021) in ways that made turning one’s face away in ignorance less possible5. In as much as the stark realities of my students were rendered more visible, I was also more conscious of my own positionality as an educator in the virtual classroom, teaching from the comfort of a middle-class (mostly) white suburb. In this landscape of inequality and loss, we need to generate a ‘cartography’ that accounts for our “locations in terms of both space (geo-political or ecological dimension) and time (historical and genealogical dimension) and [to] provide alternative figurations or schemes of representation for these locations, in terms of power as restrictive (potestas) but also empowering or affirmative (potential)” (Braidotti 2010, p. 410).

8. Risk, Serendipity, and Learning

In one of our zoom sessions under the strict lockdown conditions of the first wave of the covid crisis, another student in the honours class named Joshua Labuschagne exclaimed in exasperation, “I just want to go to a bar in the chance of meeting my husband!” I replied, “I just want to go to a bar in the chance of meeting someone other than my husband!” Despite both enjoying the relative ease and comfort of middle-class homes, being contained there in the loving familiarity of family felt like entrapment. As a young gay man, the lockdown robbed Joshua of social space in which “to be himself” in relation to others, creating a distorted temporality in which future possibilities are truncated and the horizon of adulthood seems infinitely deferred. While my response was somewhat flippant and intended to produce the laughter that it did, I too was missing the possibilities of the world outside of the known, keenly feeling the loss of serendipity and spontaneity of chance encounters. It took me a while to realise that in addition to missing my particular cohorts of masters and honours students and the frame of the seminar room in which to talk, I was also missing the things that happen on the edges of these scheduled events, where people settle in and talk to one another about anything and everything, the conversations that happen at the end of class, walking back to my office. Beyond this, the vibrancy of campus, a world of strangers and noise, the possibilities for glancing, accidental meetings and exchanges, the possibility for encountering someone or something new, for chancing upon a book on a library shelf while purposely searching for something else entirely. Education entails “the ‘beautiful risk’ of human interaction, the relational encounter where human beings come together to influence each other with words and interpretations that work to forge and sustain a common world” (Di Paolantonio 2016, p. 149).

Scholarly work also requires extended periods of withdrawal from these noisy, embodied exchanges to solitary spaces for reading, writing, and thinking. Working from home might seem like a gift for those of us who find the notion of office hours antithetical to creative, reflective intellectual work. However, the isolation of lockdown was not this. Following Hannah Arendt’s (1973) casting of the alienation of loneliness as a forceful tool of the totalitarian state, Masha Gessen (2020) puts it wonderfully bluntly: “Loneliness … makes me sad and stupid. Solitude—the opportunity to work alone while still being able to feed on human connection—makes me think.” The retreat into middle-class homes may ordinarily provide comfortable contexts for this kind of solitary intellectual work but, even without the strangely isolating effects of the pandemic, for many students, home is crowded, not only in terms of space but also in terms of demands on their time and by persistent implication in the entanglements of family relationships. In addition to the vibrant possibilities of human encounters and novelty, campus may provide the very best place for escaping into productive solitude. Although the world of reading and writing requires a retreat from social life, Njabulo Ndebele (1991, p. 139) resuscitates a positive perspective on the risks of learning. “[W]riting is essentially a subversive act. It has the powerful capability to invade in a very intimate manner, the world of the reader. Whenever you read, you risk being affected in a manner that can change the course of your life.” The trajectories of reading may be controlled by canonical histories and colonial curricula, but university students are able to roam with considerable personal and political freedom into textual territories of their own choosing.

In a society such as South Africa, university education provides exceptional opportunities to engage across historical fault-lines of race and class, bringing black and white, rich and poor students into the same space for learning. However, alongside these thrilling enticements to learn from others, there are dangers in these embodied encounters, entailing misrecognition and misunderstanding. Educational ‘contact zones’ (Mary Louise Pratt 1991) have to be carefully constructed to attend to these dynamics. As Braidotti (2010, p. 411) observes: “Dis-identification involves the loss of cherished habits of thoughts and representation, which can also produce fear, sense of insecurity and nostalgia. … Changes that affect one’s sense of identity are especially delicate.” For white students, secure in their dominant normative positionality, such challenges to identity may be defensively resisted. Such resistance may converge with institutional resistance to change, obstructing learning and imagination. Conversely, for black students, the university is often experienced as an alienating space, rendering the risk of learning and change, threatening rather than exciting. Chabani Manganyi’s (1973) analysis of ‘being black in the world’ highlights the condition of “freedom in security” (Manganyi 1973, p. 32) as essential for the realisation of human potential. The liberating possibilities of risk-taking in learning are paradoxically only fully released in the security of belonging, when one can “… inhabit a space to the extent that one can say, ‘This is my home. I am not a foreigner. I belong here’. This is not hospitality. It is not charity” (Mbembe 2016, p. 30). In addition to questions of structural power and the decolonisation of disciplinary canons, pedagogical praxis engages these power differentials at the interpersonal level, in the dynamics of classrooms, between students and teachers, and across the diverse student body. Education infused with “confrontational love” (Hooks 2000) has the potential to generate a radical openness to the world and to others, enabling the imagination of alternative hopeful futures. This is a form of political resistance that strengthens individual agency and collective relationality. “Careful curiosity opens up an appreciation of historical contingency: that things might have been and so might yet still be, otherwise” (van Dooren 2014, p. 293).

The educational task is not only to construct pathways for students to think, read and write themselves into traditions of (textual) knowledge, but also to work at meaning-making in the ‘borderlands’ (following Gloria Anzaldúa (Fine 2018)) between the personal and political, between generations, and between the everyday world of experience and the abstract worlds of theory. In some ways, the virtual classroom is, by definition, a kind of ‘borderland’, a zone that exists on the margins of our embodied worlds, in which, place and time are disrupted. The experiences that I have reflected on in this paper suggest that there may be exciting pedagogical and knowledge-making practices released in this terrain where no one is fully at home, particularly enhancing individual creativity and encouraging autodidactic reflexive attention to the everyday world. However, asynchronous disembodied online learning inevitably lends itself most easily to the unidirectional transmission of information with the teacher (and her texts, oral or visual) as the focal point. This is tendency is exacerbated when the people gathering in the zoom room have never met in-person before or have no opportunities to do so alongside these virtual learning sessions. The honours class whose narratives are woven into this article had navigated first encounters with each other and with me on campus at the start of the academic year and so were not entirely unknown to one another and had already started working together in small groups. By contrast, where meeting is exclusively virtual, barriers (particularly of class and race) between students may be reinscribed as they can quite literally avoid eye-contact with one another, avoid (mis)recognising one another, avoid confrontation and contestation. The risks of embodied encounters are high, particularly “in contexts of highly asymmetrical relations of power, such as colonialism, slavery or their aftermaths” (Pratt 1991, p. 34). However, these are the requisite risks for (un)learning the past, resisting the way things are in the present, and reimagining future possibilities. Whether learning is online or in-person, we need to resist the erosion of “contact zones” which are as vital to learning as “zones of proximal development”.

9. In Conclusion: Resistance and Hopeful Futures

Reflecting on the ways in which the pandemic brought death into everyday consciousness, the psychoanalyst, Jacqueline Rose, suggests that confronting our mortality may be politically productive.

“What on earth, we might then ask, does the future consist of once the awareness of death passes a certain threshold and breaks into our waking dreams? What, then, is the psychic time we are living? How can we prepare—can we prepare—for what is to come? If the uncertainty strikes at the core of inner life, it also has a political dimension. Every claim for justice relies on belief in a possible future, even when—or rather especially when—we feel the planet might be facing its demise”.(Rose 2021)

Living through these conditions of planetary and personal precarity, it has often felt difficult to prepare for the present let alone the unknown future. However, writing this article at a time that seems it might finally be the beginning-of-the-end, the threat of the pandemic is already mutating into the danger of forgetting. Although teaching and learning under the conditions of the pandemic were characterised by loss and grief, the disruption to established practices created cracks in the present through which to glimpse more hopeful futures (Eagleton 2016). However, the experimental possibilities of more equal and humanising praxis are frangible and already eroding. The technicist solutions of online learning are far more compatible with the commodification of higher education and metrics of success and perhaps the pandemic will retrospectively be identified as accelerating and extending this technological trajectory rather than changing the direction of human life in any fundamental way. In a way that can only be described as uncanny, Braidotti (2010) repeats the phrase, “we are in this together” as she traces humanity’s nomadic wanderings in space and time. This became the rallying cry of politicians (particularly but not only in the UK) to mobilise people to act en masse in unprecedented and peculiar ways to contain the pandemic. However, as the corona virus spawned new variants, the meaning of “being in this together” likewise mutated and it soon became clear we might be in the same storm, but we were riding the waves in very different boats.

In the strong version of what it means to be in the world ‘together’, we are called to

“…[a] double commitment, on the one hand to processes of change and on the other to a strong sense of community—of our being in this together. Our co-presence, that is to say the simultaneity of our being in the world together, sets the tune for the ethics of our interaction”.(Braidotti 2010, p. 408)

The COVID crisis disrupted routine patterns and practices across all spheres of everyday life, rupturing social relations and destabilising our capacity for building coherent selves and communities. However, despite the extraordinarily estranging impact of the pandemic, these conditions were continuous with catastrophic historical conditions before, and with the resurgent forms of dehumanising inequality and conflict in its immediate aftermath. Institutions and individuals alike are resistant to learning the lessons of fragility and fungibility of life. Learning to resist is therefore an unfinished process requiring critique and hope. In its best articulations, higher education is a space for intergenerational dialogue, connecting the past and future through memory and imagination to animate creative action in the present.

Funding

The intergenerational narratives included in this article form part of the NEST (Narrative Enquiry for Social Transformation) research project. NEST is funded by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation and the NIHSS (National Institute of Humanities and Social Sciences) of South Africa.

Acknowledgments

I am thankful to all the students who have taught me about learning to resist, particularly to my Honours class of 2020 and most especially to the students whose narratives are included here. I am grateful to the Poaching Covid Teaching and Learning Collaboration for collegial support through these strange and estranging times. Thanks to the two anonymous reviewers who offered generous readings of my work and whose feedback helped to strengthen the final version of this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | All students referred to in this article granted permission to present their stories, for which I am very thankful. Their choice to be identified by their real names rather than pseudonyms, suggests that these tasks were experienced as authentically connected to their lives rather than merely performed for credit. |

| 2 | Data extracts are presented verbatim with only very light editing for readability. |

| 3 | The story to which Zimitri refers is found in her book, “Race Otherwise”: “When I was a baby my mother wrapped and handed me to Mrs Pearce thought he gate in the zinc fence between out fomes. She minded me while my mother taught at Gelvandale Primary School. Twice daily, Mrs Pearce or a member of her family, often accompanied by one or two children, visited our back yard to fetch water from our newly plumbed, lit and lawned home. She cooked on a primus stove, the same one on which she heated the hot-comb used to style her hair. Her home was wrapped in the smell of paraffin and laced with the smell of starch, freshly solidifying under the iron which was also heated on the paraffin stove. During winter, when we used a paraffin heater to keep warm, our home smelt like hers. It also smelt of Lavender Cobra floor polish, Surf washing powder, Sunlight soap, Sheen hair straightener, police uniforms, home-baked bread, shoe polish used to spit-and-shine, the blue scribbles of my mother’s pupils and Goya Magnolia talcum powder—signs of a family steeped in working class respectability” (Erasmus 2017, p. 11). |

| 4 | Pia Bombardella’s mother tongue is Italian and, in an earlier conversation about pansy-growing, she mentioned that ‘pansy’ has the same route as ‘pensiere’ meaning to ‘to think’. Together with our conversation about the Afrikaans name, ‘gesiggies’ (literally translated as ‘faces’) these little flowers were imbued with meaning beyond their prettiness. |

| 5 | I have written more extensively about white ignorance, the implications for teaching, and possibilities for learning and change, elsewhere. See chapter four, (Mis)understandings and active ignorance, in (Bradbury 2020), Narrative Psychology and Vygotsky in dialogue: Changing subjects. |

References

- Andrews, Molly. 2014. Narrative Imagination and Everyday Life. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Arendt, Hannah. 1973. The Origins of Totalitarianism. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. [Google Scholar]

- Berlant, Lauren. 2011. Cruel Optimism. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1986. The Forms of Capital. In Handbook of Theory of Research for the Sociology of Education. Edited by John Richardson. Westport: Greenwood Press, pp. 46–58. [Google Scholar]

- Brabazon, Honor. 2021. The Academy’s Neoliberal Response to COVID-19: Why Faculty Should be Wary and How We Can Push Back. Academic Matters. Berlin/Heidelberg: Spring, Available online: https://academicmatters.ca/the-academys-neoliberal-response-to-covid-19-why-faculty-should-be-wary-and-how-we-can-push-back/ (accessed on 22 April 2021).

- Bradbury, Jill. 2017. Creative twists in the tale: Narrative and visual methodologies in action. Psychology in Society 55: 14–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradbury, Jill. 2020. Narrative Psychology and Vygotsky in Dialogue: Changing Subjects. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury, Jill, and Peace Kiguwa. 2012. Thinking Women’s worlds. Feminist Africa 17: 28–48. [Google Scholar]

- Braidotti, Rosi. 2010. Nomadism: Against methodological nationalism. Policy Futures in Education 8: 408–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Burman, Erica. 2017. Deconstructing Developmental Psychology, 3rd ed. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Callard, Agnes. 2020. What do the Humanities Do in a Crisis? The New Yorker. April 11. Available online: https://www.newyorker.com/culture/annals-of-inquiry/what-do-the-humanities-do-in-a-crisis (accessed on 30 April 2020).

- Canham, Hugo. 2018. Theorising community rage for decolonial action. South African Journal of Psychology 48: 319–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canham, Hugo. 2021. Black death and mourning as pandemic. Journal of Black Studies 52: 296–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denis, Philippe, ed. 2005. Never Too Small to Remember: Memory Work and Resilience in Times of AIDS. Pietermaritzburg: Cluster Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Di Paolantonio, Mario. 2016. The cruel optimism of education and education’s implication with ‘passing-on’. Journal of Philosophy of Education 50: 147–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagleton, Terry. 2016. Hope without Optimism. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Erasmus, Zimitri. 2017. Race Otherwise: Forging a New Humanism for South Africa. Johannesburg: Wits Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fine, Michelle. 2018. Just Research in Contentious Times: Widening the Methodological Imagination. New York: Teachers College Press. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault, Michel. 1988. Technologies of the Self. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, Mark. 2010. Hindsight. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gessen, Masha. 2020. The Political Consequences of Loneliness and Isolation During the Pandemic. The New Yorker. May 5. Available online: https://www.newyorker.com/news/our-columnists/the-political-consequences-of-loneliness-and-isolation-during-the-pandemic (accessed on 22 May 2020).

- Hooks, Bell. 2000. All about Love. New York: Harper Perennial. [Google Scholar]

- Levinas, Emmanuel. 1963. The Trace of the Other, (La Trace de l’Autre). Edited and Translated by Alphonso Lingis. pp. 345–59. Available online: https://jst.ufl.edu/pdf/dragan2001.pdf (accessed on 24 March 2019).

- Manganyi, N. Chabani. 1973. Being-Black-in-the-World. Johannesburg: Ravan Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mbembe, Achille. 2016. Decolonising the university: New directions. Arts and Humanities in Higher Education 15: 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, Ronald, Jill Bradbury, and Priya Dayaram. 1999. The half-life of semester-long learning. South African Journal of Higher Education 13: 149–54. [Google Scholar]

- Mncube, Zimbali. 2022. Only the State (Not the Private Sector) Can Prioritise Social, Environmental and Civic Wellbeing. Daily Maverick. Available online: https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/opinionista/2022-02-18-only-the-state-not-the-private-sector-can-prioritise-social-environmental-and-civic-wellbeing/ (accessed on 18 April 2022).

- Morris, Steven. 2020. Bristol Mayor: Removal of Colston status was act of ‘historical poetry’. The Guardian. June 13. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2020/jun/13/bristol-mayor-colston-statue-removal-was-act-of-historical-poetry (accessed on 28 February 2022).

- Motimele, Moshibudi. 2019. The rupture of neoliberal time as the foundation for emancipatory epistemologies. The South Atlantic Quarterly 118: 205–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndebele, Njabulo S. 1991. The Rediscovery of the Ordinary: Essays on South African Literature and Culture. Johannesburg: COSAW (Congress of South African Writers). [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, Bhekizizwe. 2019. Spectrality and inter-generational black narratives in South Africa. Social Dynamics 45: 327–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, Mary Louise. 1991. Arts of the contact zone. Profession, 33–40. [Google Scholar]

- Ramoupi, Neo L., Thokozani Mathebula, and Sarah Godsell. 2021. ‘Wits. For Good’–For Whose Good, Exactly? Daily Maverick. March 25. Available online: https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2021-03-25-wits-for-good-for-whose-good-exactly/ (accessed on 24 February 2022).

- Rosa, Hartmut. 2020. The Uncontrollability of the World. Cambridge: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, Jacqueline. 2021. Life after death: How the pandemic has transformed our psychic landscape. The Guardian. December 7. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/society/2021/dec/07/life-after-death-pandemic-transformed-psychic-landscape-jacqueline-rose (accessed on 13 December 2021).

- Roy, Arundhati. 2020. The Pandemic is a Portal. Financial Times. April 3. Available online: https://www.ft.com/content/10d8f5e8-74eb-11ea-95fe-fcd274e920ca (accessed on 4 April 2020).

- Roy, Arundhati. 2021. We are Witnessing a Crime Against Humanity. The Guardian. April 28. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/news/2021/apr/28/crime-against-humanity-arundhati-roy-india-covid-catastrophe (accessed on 24 February 2022).

- Solnit, Rebecca. 2020. ‘The Impossible has Already Happened’: What Coronavirus Can Teach Us about Hope. The Guardian. April 7. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/apr/07/what-coronavirus-can-teach-us-about-hope-rebecca-solnit (accessed on 27 April 2020).

- van Dooren, Thom. 2014. Care: Living lexicon for the environmental humanities. Environmental Humanities 5: 291–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vygotsky, Lev S. 1978. Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes. Edited and Translated by Michael Cole and Sylvia Scribner. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).