Abstract

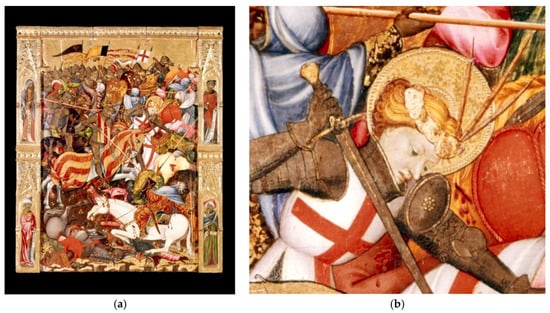

The cult of St George in the Eastern Mediterranean is one of the most extraordinary examples of cohabitation among different religious communities. For a long time, Greek Orthodox, Latins, and Muslims shared shrines dedicated to the Cappadocian warrior in very different places. This phenomenon touches on two aspects of the cult—the intercultural and the transcultural—that should be considered separately. My paper mainly focuses on the cross-cultural value of the cult and the iconography of St George in continental and insular Greece during the Latinokratia (13th–14th centuries). In this area, we face the same phenomenon with similar contradictions to those found in Turkey or Palestine, where George was shared by different communities, but could also serve to strengthen the identity of a particular ethnic group. Venetians, Franks, Genoese, Catalans, and Greeks (Ῥωμαῖοι) sought the protection of St George, and in this process, they tried to physically or figuratively appropriate his image. However, in order to gain a better understanding of the peculiar situation in Frankish-Palaiologian Greece, it is necessary first to analyze the use of images of St George by the Palaiologian dynasty (1261–1453). Later, we will consider this in relation to the cult and the depiction of the saint on a series of artworks and monuments in Frankish and Catalan Greece. The latter enables us to more precisely interrogate the significance of the former cult of St George in the Crown of Aragon and assess the consequences of the rulership of Greece for the flourishing of his iconography in Late Gothic art.

1. Saint George, a Saint for Cross-Cultural Studies

Parmi les saints de l’antiquité, nul n’a éclipsé la gloire de Saint Georges. Sa renommée s’est répandue dans toutes les parties du monde chrétien; l’Orient et l’Occident l’ont célébré avec enthousiasme.(Delehaye 1909, p. 45)

As is well known, the cult of St George in the Eastern Mediterranean is one of the most extraordinary examples of cohabitation among different religious communities (Hasluck 1929, pp. 47–54; Pancaroglu 2004; Albera and Fliche 2012, pp. 97–99; Bowman 2012, p. 13; Couroucli 2012a). For a long time, Greek Orthodox, Latins, or Muslims shared shrines dedicated to the Cappadocian warrior in very different places. This phenomenon touches on two aspects of the cult—the intercultural and the transcultural—that should be considered separately.

Although the use of these two terms can be puzzling, each has a precise meaning. When we say that the cult of St George is ‘intercultural’, we are referring to the capacity of the saint to blur religious and ethnic divisions within a particular area or society. As a result of this, celebrations of the saint became privileged spaces of interaction, in which different communities shared in his worship. That is therefore a phenomenon that is intercultural (or cross-cultural). It is common to multi-ethnic and multi-religious societies as are found in Palestine, Lebanon, Anatolia, or Latin Greece. However, the term ‘transcultural’ describes the specific ability of St George to cross religious and cultural borders and thereby acquire new features or annex to other figures. This metamorphosis or appropriation is usually linked to the movement of populations, particularly in campaigns of conquest, and occurs in frontier lands such as the Crusader States, Seljuk Anatolia, or Frankish Greece. As such, both terms relate to cross-cultural studies and can simultaneously apply to a single case. While the first—intercultural—stresses the idea of cultural convergence around worship, the second—transcultural—refers to the faculty of the saint to migrate across regions, ethnicities and religions and take on a new significance or new properties.

On the one hand, as an example of intercultural worship, I will single out the case the case of Lod (Israel), the former Lydda, close to Tel Aviv. According to legend (Greek Acta), having been born in Cappadocia, after the death of his father, George came during his childhood to Lydda—the ancient Diospolis—which was the birthplace of his mother. Subsequently, following his martyrdom in Nicomedia (Asia Minor), certain pilgrimage accounts indicate that his remains were moved to Lydda, the alleged place of his burial and even martyrdom (Theodosius, about 530), where numerous miracles occurred (Delehaye 1909, pp. 46–47; Hulst 1909, p. 7; Marco and Ángel 1987, pp. 29–31; Walter 1995, pp. 314–20; Sayrach 1996, pp. 30–31; MacGregor 2002, pp. 44–46; Walter 2003, pp. 112, 120; Marco and Ángel 1987, pp. 29–31; Riches 2015, p. 10). The current Greek Orthodox church in Lod, which was built in 1870 above an earlier church, shares space with an attached Muslim mosque that is also associated with the cult of St George.1 One of the most striking examples of a shared sanctuary is the festival of St George in the church of Aya Yorgi in the island of Büyükada, in Istanbul. Every 23rd of April the place receives a flood of pilgrims, both Christian and Muslim, who celebrate there the arrival of Spring (Couroucli 2012b, pp. 119–25).

On the other hand, the image of George as warrior and dragon-slayer possesses a special transcultural ability to cross religious and cultural borders where might then be annexed to other figures. Thus, in Anatolia, Lebanon, Syria, and Palestine, Saint George became the Muslim saint al-Khidr (Hasluck 1929, pp. 47–48, 319–34; Budge 1930, pp. 44–45; Pancaroglu 2004, pp. 58–59; Couroucli 2012b, pp. 132–33; Riches 2015, pp. 17–21; Hélou 2014). This Muslim saint is a divine character who is mentioned in the Koran (18, 60–82) accompanying Moses, and whose special day was celebrated on 23th April when he is invoked as the protector of travellers, navigation, and vegetation. Since the battle of Manzikert in 1071 and the subsequent Seljuk occupation of Anatolia, the image of the Muslim hero al-Khidr is assimilated to that of St George the Cappadocian, and decorated amulets, coins, and lamps.

Although the holy warrior of Cappadocia2 went on to be painted in Orthodox churches as before, there were occasions in which this depiction acquired a distinctive significance under the new Muslim rule. Thus, the new monastic cave-church dedicated to St George (Kirk Dam Alti Kilise or St. George at Belisirma), built between 1284 and 1295, in the Ihlara Valley. There, the Christian donors, the emir Basil Giagoupes, and his wife, the kyra Thamar, who were administrators of the region, are depicted flanking a standing and monumental St George (Figure 1). The Greek inscription informs us that this was made under the rule of the Seljuk Sultan Mesud II (1284–1297 and 1303–1307) and the Byzantine emperor, Andronikos II Palaiologos (1282–1328), who was no longer the ruler of this land but gave support to Mesud II to take the sultanate’s throne at Konya (Vryonis 1977; Teteriatnikov 1996, pp. 209–10; Cooper and Decker 2012, pp. 157, 186 and 260; Jolibert-Lévy 2002, pp. 111–13; Métivier 2012, p. 239; Preiser-Kapeller 2015, pp. 219–20; Kitapçi Bayri 2019, p. 107).3 So, it is very likely that in this particular case, the presence of St George and the invocation to the Byzantine emperor were, on the one hand, a way of expressing and strengthening the “Byzantine” identity of the Orthodox Greek community—who were here outside the Byzantine state and within the Muslim Sultanate of Rum. On the other hand, the dual mention of the Sultan of Rum and the emperor is also a way to reinforce the bond between Greeks and Muslims in the context of alliances between Andronico II and Mesud II.

Figure 1.

St George between Emir Basil Giagoupes and his wife, kyra Thamar. Kirk Dam Alti Kilise or St George at Belisirma, Ihlara Valley (Cappadocia, Turkey), 1284–1295. © Author.

Notwithstanding the above, my paper focuses on the cross-cultural value of the cult and iconography of St George in another geographical area, that of Greece during the Latinokratia (13th–14th centuries).4 Here we confront a similar phenomenon where the contradictions are the same as those found in Turkey or Palestine, in which George is not only shared by different communities but also serves to strengthen the identity of a particular ethnic group.5 However, in Frankish Greece we are faced with exclusively Christian communities—Latin and Greek—who are fighting or praying for the same saint in a very specific context of war or peace. In each case the military dimension prevails and the object of devotion remains the Cappadocian warrior in his role as protector of the armies. Nonetheless, it is true that in the turbulent context of the Latinokratia, every ‘nation’ or ‘ethnic group’ tried to appropriate the image of St George because of the talismanic and charismatic power of the saint. Thus, this particular ‘struggle for St George’ became a mirror of the hostilities that ravaged Greece from the 13th to 15th centuries, in which, as we will see, St George was the image par excellence of the two principal contenders: the Byzantines and the Crusaders.

Despite the enmity, nothing prevents the rise of the transcultural and intercultural aspect of the cult of St George in this area, in which the encounter between Latins and Greeks entails an exchange of motifs, a flow of relics, and the creation of shared sanctuaries. Furthermore, in some cases, a double-echo effect transformed perception of the saint both in the Crusader States in Greece and in the Latin metropolis. This is particularly interesting in lands ruled by the Crown of Aragon, in which it is possible to determine a cause-and-effect process running in both directions. This phenomenon precedes and announces what Natasha Eaton has defined for the art of colonialism as ‘mimesis in flux’ (Eaton 2013, pp. 2–4). The Crusading spirit that dominated the expansion of the Kingdom of Aragon in the 13th century resulted in an emerging cult, and the patronage of an exotic St George, in direct relation to the chivalric ideals of kingship. The 14th-century military feats of Catalan mercenaries in Anatolia and Greece fuelled this role of St George as protector of the armies and was accompanied by an increasing mythification of the saint as symbol of a collective identity of the communities that settled in newly conquered lands in both Iberia and Greece.

2. Saint George in Frankish-Palaiologan Greece

(…) let’s not forget that the whole Greece is, in many respects, a frontier.(Seferis 2010, p. 39)

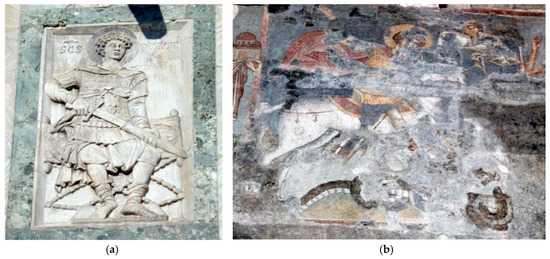

After the Crusader sack of Constantinople in 1204, and the establishment of the ephemeral Latin Empire, the former Byzantine lands of Greece were divided among Venetians, Franks, Genoese, and Greeks (Ῥωμαῖοι: Rhomaioi), to whom the Catalans were added in the 14th century (Lock 1995). All of these groups sought the protection of St George and in this process, they tried to physically or figuratively appropriate his image. For instance, a couple of reliefs depicting St Demetrios (Byzantine spolium) and St George (13th-century slab), in their role as patrons of the Venetian army and guardians of the Ducal Palace, were included in the 13th-century façade of the basilica of St Mark in Venice some decades after the looting of Constantinople (Figure 2a). According to David M. Perry, the display of these carvings shows how “eastern Mediterranean Christian militarism had been appropriated by Venice” in pursuit of the idea of translatio imperii (Perry 2014, p. 16). Likewise, the no less ambitious republic of Genoa, did not hesitate around 1312 to commission a painter from Constantinople (Marcus) to execute a monumental mural painting of the city patron, St George, in the renewed cathedral of Genoa (Nelson 1985) (Figure 2b). In both cases, the use of St George can be seen either as an appropriation or a self-identification with Byzantium. It should not be forgotten that these two maritime republics were flighting during this period, using different strategies, to play the role of Byzantium in the Eastern Mediterranean.

Figure 2.

(a) St George. Façade of the basilica of Saint Mark in Venice, 13th century. © Author “per gentile concessione della Procuratoria di San Marco”. (b) Marcus (?), St George horsing and slaying the Dragon. Cathedral of Genoa, north aisle, ca. 1312. © Author.

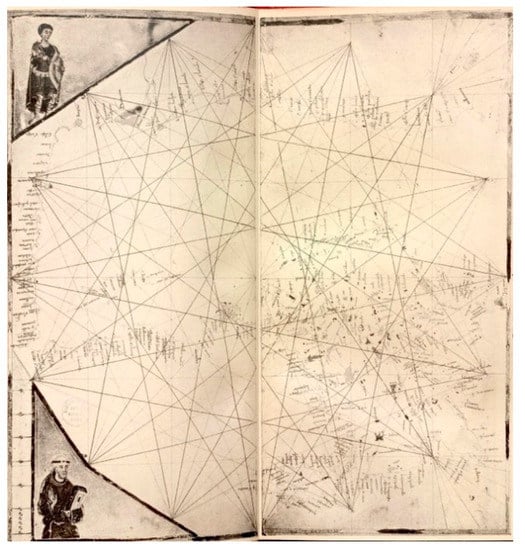

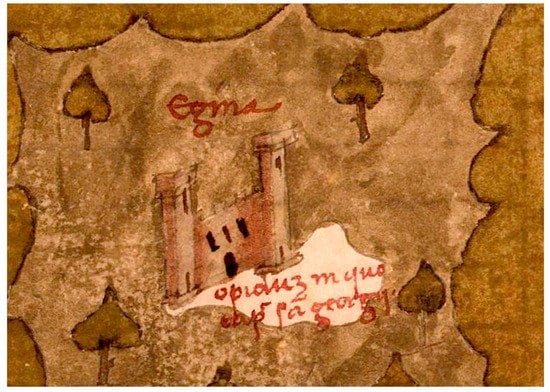

The most compelling example of this interaction between the two sides of the Mediterranean in relation to the cult of St George is the Atlas-Portolano made by Petrus Vesconte in Venice (Lyon, Ms. 175. F. 7–8) (De LaRoncière 1929, Table IV) (Figure 3). This map shows the new Latin perception of the sacred geography of the Mediterranean in the aftermath of the sack of Constantinople; the establishment of Crusader States in the former territories of the Byzantine Empire; and the expansion of the Mendicant Orders in the Levant. Here, saints are arranged across different areas of a map. It is no coincidence that St Francis and St George were depicted in the Eastern Mediterranean, at just the moment that the Franciscans were expanding in the Holy Land (Roncaglia 1954), Constantinople and Greece, and at a time when the cult of St George was increasingly diffused among Latins and Greeks (Gerstel 2001, pp. 267–78; Hirschbilchler 2005a, pp. 120–24). However, in a sense, the depiction of George standing, following the Byzantine iconography, should be interpreted as an attempt to geographically identify the Cappadocian saint with the heritage of the Eastern Roman Empire. This was an issue of permanent concern by the different leading trade powers in the Mediterranean.

Figure 3.

St George and St Francis in the Atlas-Portolano of Petrus Vesconte, Venice, 1319. Lyon, Ms. 175. F. 7–8. Source: (De LaRoncière 1929, Table IV).

2.1. Saint George in the Byzantine Empire: Komnenian and Palaiologan Uses

However, in order to gain a better understanding of the peculiar situation in Frankish-Palaiologian Greece, it is necessary first to analyze the use of images of St George by the Palaiologian dynasty (1261–1453). Although the Cappadocian warrior had enjoyed great success as a military saint in the art of frontier lands and had been identified as the protector of the upper ranks of the Byzantine army, with the reconquest of Constantinople by the Palaiologoi his figure becomes even more present. The precarious situation of the Late Byzantine Empire, surrounded and besieged by all on its borders, gave particular prominence to the iconography of George as a reference mark and keeper of Greek interests. Once we know this, we can cross-check it against the cult and depiction of the saint in the Frankish, Genoese and Catalan Greece.

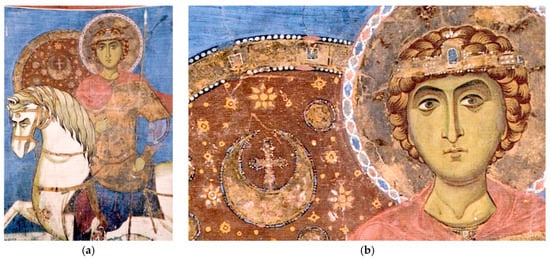

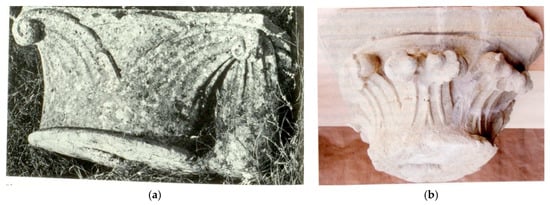

It is well known that the wide diffusion of the depiction of St George during the Palaiologan dynasty is related to his singular role as military saint. Since the 10th century George had been the patron saint of the army, generals, and powerful families around the emperor (Walter 2003, pp. 40–41; Grotowski 2010, p. 122). He was depicted either standing, wearing the lorica segmentata (segmented cuirass) as a Roman soldier, or riding a horse (Mark-Weiner [1977] 2003; Gerstel 2001, p. 270; Grotowski 2010, pp. 130–31, 232–35). This association is underscored by his depiction in the monastic church of Panagia Phorbiotissa at Asinou (Cyprus), in which George wears a luxury diadem (stemmatogyrion) characteristic of the Imperial Palace guard from the 11th century (Figure 4a,b). The inscription informs us that this is a votive image commissioned by Nicephoros, a horse-breeder, in honor of the megalomartyr Γεώργιος. The painting is in the narthex, between the East and West entrances to this space, in order to underline the apotropaic role of the saint as was common in Byzantine painted churches (Nicolaïdès 2012).

Figure 4.

St George horsing. Panagia Phorbiotissa at Asinou (Cyrpus), narthex, south conch, end of the 12th century. (a) Detail of St George. (b) Detail of the shield with the Crescent Moon crowned by a cross and encircled by three stars. © Used with permission of Ángel Bartolomé.

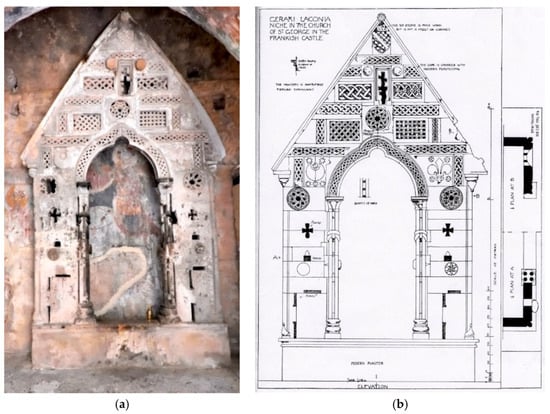

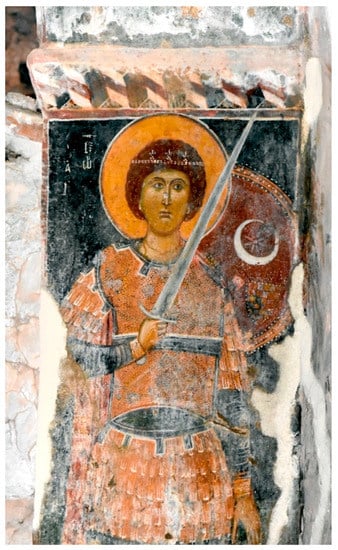

Having been made when the island was under Latin rule at the end of the 12th century (after 1191–1192), the image of St George at Asinou was intended to be seen as Byzantine and could be distinguished from other equestrian images of St George used by the Crusaders. This explains motifs such as the genuine diadem or the very peculiar heraldic shield with the Crescent Moon crowned by a cross and encircled by three stars. It is likely that the heraldic shield was a Byzantine invention in response to Latin heraldry (Stylianou 1982a). Although Byzantines had no tradition of a coat of arms, the appearance of Crusaders in their former lands encouraged the use of heraldry in certain images. Thus, in Asinou, George is wearing a bizarre blazon. It happens at other sites in the 13th-century Peloponnese, in lands such as the Despotate of Morea that had been recently reconquered by Byzantines from Latin hands, such as Hagios Ioannis Chrysostomos at Geraki, where the saint also protects the door (Figure 5a). As Andreas and Judith Stylianou highlighted, both shields are round ‘peltas’ as is characteristic of the Byzantine army. Latin shields are usually kite-shaped or triangular. However, the most striking motif is that of the Crescent Moon crowned by a cross and a star. This emblem was employed on Imperial coins, especially under Alexis Komnenos, and derives from Roman coins of the former city of Byzantium, as protected by the goddess Artemis (Moon) (Stylianou 1982a, p. 70; Stylianou 1982b, pp. 139–40; Grotowski 2010, pp. 236–37, n. 421, and 249). (Figure 5b)

Figure 5.

(a) St George. Hagios Ioannis Chrysostomos at Geraki, c.1300. © Used with permission of the Ephorate of Antiquities of Lakonia, Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports/Archaeological Resources Fund. (b) Roman coin of the former city of Byzantium, with bust of Artemis on the anverse and an eight-rayed star with a crescent in the reverse, 1st century. Source: Wikipedia commons (Star and Crescent).

Nevertheless, the use of this primitive emblem on St George’s shield can be connected with another tradition: That of the Roman legionary shield devices, which have been preserved in early modern copies of the Notitia Dignitatum. Illustrations in this text, originally composed in the middle of the 6th century, provide us with compelling comparisons to the blazons depicted in Asinou and Geraki. I am referring to the Insignia viri illustris militum per Thracia, in which Pannoniciai iunores and Tzaani have a shield with the crescent and the stars (Notitia Dignitatum VIII, pp. 16–17, Oxford, Bodleian Library, Canon Misc. 378, f. 94v; Luccheti 2014) (Figure 6). It is no coincidence that these ancient insignia with the crescent and the stars are attributed to the army in Thrace, the Roman province to which the city of Constantinople belongs. I therefore wonder if the choice of this blazon for equestrian depictions of St George in the Komnenian and Palaiologian period mirror an interest in bringing prestige to the Byzantine warrior by linking his shield to the ancient Roman army in Thrace.

Figure 6.

Notitia Dignitatum VIII, 16–17, Oxford, Bodleian Library, Canon Misc. 378, f. 94v, Basel, 1436. © Used with permission of the Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford.

The most eloquent demonstration of the importance of St George and the use of insignia related to him in the Palaiologan court is provided by the Book of Ceremonies of the Imperial Palace, known as Pseudo-Kodinos (1341–1353). During the celebration of the ceremony of the Prokypsis at Christmas, Epiphany, and Palm Sunday in the courtyard of the Blachernai Palace, the emperor mounted a wooden podium (πρόκυψις) to be acclaimed.6 During this performance, the emperor was accompanied by a procession consisting of the chiefs of the army (sebastokrator, podestás) and the Imperial Guard waving seven banners and standards, among which were an equestrian image of St George and the Octopus (the eight-pointed star of Manuel I Komnenos) as well as a banner featuring a metal dragon. It is not by chance that this ceremony in the courtyard was performed right in front of the chapel of the Theotokos Nikopoios, whose exterior was decorated with a monumental mural icon depicting St George (Macrides et al. 2013, IV, pp. 125–33, 172–75, 239, 342–43, 369; Magdalino 2007; Walter 2003, p. 41; Grotowski 2010, p. 247).

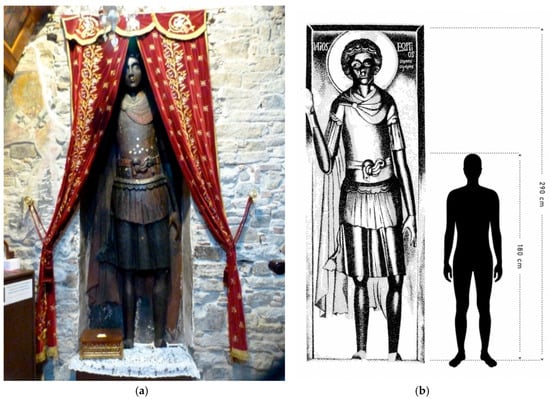

It is also worth mentioning that the cult of the saint was reactivated during the Palaiologan restoration of the Byzantine Empire in Constantinople. According to Nicephorus Gregoras (I, 303, 11–308, 22), the last Latin emperor, Baldwin II (1228–1261), heard St George’s horse neighing on the eve of the conquest of the city by Michel VIII Palaeologus (Macrides et al. 2013, p. 369, n. 22). It is very likely that this and other victories of Michel VIII over the Latins promoted the spread of the cult of St George, particularly in northwestern Greece after the battle of Pelagonia (1259).7 This should explain the unusual setting of a colossal wooden statue or xoanon of St George (almost 3 mts. high) in the church of Hagios Georgios in Omorfokklisia (ancient Kalista or Galista), close to Kastoria, in northwestern Macedonia (Figure 7a,b) Although this colossus has been dated to 1286–1287 after a painted dedicatory inscription in the church, its actual date is uncertain. Most scholars think that the epigraph was repainted and is later than the interior painted decoration. In the inscription are mentioned the brothers kyr Nichephoros, John, and Andronikos from the noble family of Netzades, along with the names of the family of Andronikos II (1282–1328). Paradoxically, the same members of Netzades family (with Jacob instead of John) along with the names of Andronikos II’s family are mentioned in another inscription with the date 1255 in the nearby church of Taxiarches in Tsouka (Kalopissi-Verti 1992, pp. 48–49, 103–4). Thus, it is likely that this represents a damnatio memorie, in which the original names of the rulers were replaced. As the paintings in Omorphoklisia seem to date from the period of Byzantine domination over the region after the battle of Pelagonia (1259), the name of the original ruler erased in the inscription might have been Michael VIII (1261–1282), who was responsible for the failed and therefore controversial Union of the Churches (Paisidou 2001; Bogevska 2012, pp. 54–155).

Figure 7.

Colossal wooden icon of St George, c.1261–1282. Hagios Georgios in Omorfokklisia ancient Galitsa), Kastoria (Macedonia, Greece). (a) General view of the wooden icon of St George. © Author (b) Drawing of the wooden icon of St George in relation to human scale © Used with permission of Iker Spozio.

This monumental wooden sculpture has been related to other examples of the same period located in the diocese of the archbishop of Ohrid (i.e., statue of St Clement from Ohrid) (Grabar 1976, p. 156; Δρακοπούλου 1997, pp. 69–71; Bogevska 2012, pp. 161–62; Τσιγαρίδας 2016, pp. 88–91; Κωσταντινίδη 2016, pp. 36–37), to which the bishop of Kastoria belonged. Notwithstanding this, the particular features of this colossus have led some scholars to consider Constantinople as the original place of production (Sotiriou 1930, p. 180). Both its monumental format and the use of round relief were probably intended as a reference to the ancient public statues of Constantinople, most of them related to the memory of Constantine in the Middle Ages (Mango 1963, pp. 53–56). It is no coincidence that Michael VIII, acclaimed in text and image as the New Constantine (Macrides 1980), also promoted this tradition of celebratory statues by erecting a statue on a bronze column in front of Hagioi Apostoli.8 This consisted of a monumental figure of St Michael with the emperor at his feet offering up the city of Constantinople. In my opinion, the colossal image of St George in Kastoria—and probably the now lost statue of George from the village of Nestorio (Kastoria) (2.15 m. tall) (Μουτσόπουλος 1993, p. 47; Τσιγαριδας, p. 92)—should be related to this revival of monumental statuary during the first Palaiologan period in Constantinople (cf. Melvani 2013) and the renewed cult of the saint in the capital, where the emperor restored the Orthodox rite in the famous sanctuary of the monastery of St George in Manganas (Janin 1969, pp. 71–72). Indeed, the face of the colossus is reminiscent of the Theodosian style, and indicates possible production in a Constantinopolitan workshop.

It is worth recalling that Kastoria occupied a strategic position in the period of Michael VIII. It acted as a stronghold to control a frontier area only recently recovered by the Byzantine Empire after the battle of Pelagonia. Besides, the city was an important artistic and trade center, where educated officials and army members lived. This would explain the numerous depictions of military saints in its churches, especially those of St George, in his role as patron saint of the army, in wall paintings, icons, and sculptures in the round. It is likely that these extraordinary and uncommon 13th-century Palaiologan colossal statues of St George were then perceived by both the local population and Byzantine host as talismans or protectors for this recently recovered area. These giants—in the role of Byzantine icons—might have been perceived by the viewer as types of living being who were able to act and perform wonders in favor of the faithful. Using C. Stephen Jaeger’s terminology, we are before genuine charismatic works of art, whose strength and potential to effect events exceed those of simple objects (Jaeger 2012, pp. 3, 98–99). Ultimately, these depictions of a huge standing St George may also be considered as a Byzantine response to the Latins, who were expelled from Constantinople in 1261 by Michael VIII Palaeologus but continued in their Greek lands to appropriate the image and relics of St George.

2.2. Saint George in the Frankokratia: Exchanges and Cultural Identities

In the Latin Peloponnesus (Principality of Achaea or Morea and the Duchy of Athens), the wide dissemination of the depiction of the saint in 13th- and 14th-century art favoured the equestrian type killing the dragon rather than George as a standing figure. In most of these, George bears an oblong shield, which is characteristic of Latin warriors. This is often decorated with a blazon consisting of the Cross of St George. This symbol was actually borrowed from the Latin iconography of St George developed by Crusaders following the apparition of the saint during the capture of Antioch in 1098.9 The paintings of the Frankish gatehouse at Nauplio, in the Duchy of Athens (1291–1311), provide a paradigmatic example of this: The common Byzantine round shield of St George is decorated inside by an oblong blazon depicting a red cross on a white background, that is the Cross of the Crusaders (Figure 8). Moreover, the saint is standing up on his spurs, as Crusader warriors did (Hirschbilchler 2005a, pp. 110–11; Hirschbilchler 2005b, p. 19, Figure 8).

Figure 8.

St George. Paintings in the Frankish gatehouse at Nauplio, ca. 1291–1311. Source: (Hirschbilchler 2005b).

The aim of this Latinization of the Byzantine iconography of St George in Greece was to distinguish the depictions produced for the Franks, especially when they were made by Greek painters, and strengthen the cohesion among the Frankish population in Morea. As heirs to the Crusaders, the Latins wanted to emphasize their divine role in the Peloponnesus by invoking the same saint that protected the Crusaders in the conquest of Antioch and Jerusalem.10 It is worth noting that defeat of Pelagonia was a blow to Frankish pride in Greece, as William of Villehardouin, prince of Achaea (1246–1278), was captured by the Byzantines and later released (1262) on condition that he handed over the strongholds of Monemvasia, Maina, and Mistra to Emperor Michael VIII (Runciman 2013, p. 34). However, one year after William’s liberation, in 1263, the Franks were able to defeat the Byzantine army in Prinitza (near ancient Olympia), and thereby preserve their possession of Andravida, the capital of the Principality of Achaea. It is not a coincidence that in a 14th-century account glorifying the family Villehardouin—the Greek version of the Chronicle of Morea (ca. 1320)—a white knight appears riding his horse during this battle to lead the Frankish host (“εἶδαν καὶ ἐμαρτύρησαν ὅτι εἶδαν καβαλλάρην ἀσπραλογᾶτον εἰς φαρί, γυμνὸν σπαθὶν ἐβάστα, καὶ πάντα ὑπήγαινεν ὀμπρὸς ἐκεῖ ποῦ ἦσαν οἱ Φράγκοι”), who was identified as Saint George (Egea 1996, 4788–91, p. 238–241). Thus, the very same saint who was widely celebrated by the Palaiologoi in Macedonia, was also acting as a reliable protector of the Latins in Morea—performing miraculous deeds in battle that reminded them of those carried out by George for the Crusader army in the Holy Land.

As Sharon Gerstel (2001, p. 267) and Monika Hirschbilchler (2005b) pointed out, this shared patronage of St George between foes provoked an exchange of iconographic and heraldic motifs in his imagery. Ultimately, Latin and Greeks shared the chivalric ideals embodied by St George. This explains, for example, the fact that in Hagios Ioannis Chrysostomos at Geraki, the saint was depicted around 1300 bearing a Latin oblong shield (Figure 5a). Although, from 1261 Geraki was under Byzantine rule, they chose the Crusader-like equestrian type of St George to invoke his role as protector. Notwithstanding this, they did not hesitate to include the above-mentioned motif of the crescent to mark his unquestionable Byzantine allegiance. As a result, most of the depictions of St George in Byzantine and Latin Greece during the Latinokratia period should be seen as a game or chain of responses: If colossal standing Georges challenged equestrian Crusader knights in Macedonia, Georges on horseback in a shared Peloponnese acted as a mirror-image for both communities. The goal of these exchanges was not only to highlight the military and apotropaic character of the saint but also create an identification between George and their respective audiences.

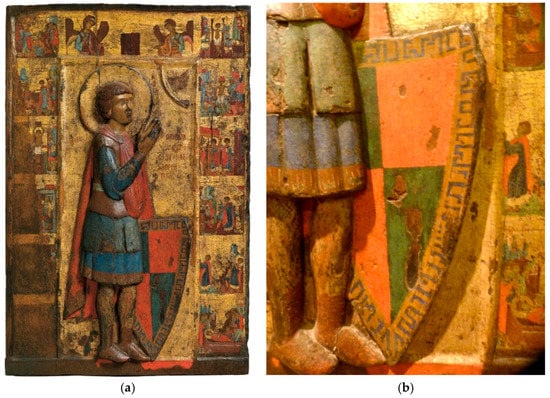

As previously noted, the practice of heraldry was alien to Byzantine culture, where arms were simply reduced to the Imperial Insignia. Thus, the display of arms by some of the Latins in the Eastern states was a genuine sign of appropriation. This gained special relevance when the coats of arms were associated with major transcultural saints such as Saint George, mega-martyr par excellence and patron of the Byzantine, Catalan, Venetian, and Genoese armies. For this reason, I am particularly intrigued by an object kept in the Byzantine and Christian Museum in Athens—a wooden-relief Vita icon of Saint George (107 cm × 72 cm), in which the saint displays what seems to be a Latin coat of arms (Figure 9a,b). This detail has been dismissed by scholarship as a mere imitation of the Frankish shields. Furthermore, in this depiction, the saint does not wear the common muscled or lamellar cuirass of Byzantine warriors but is dressed in Latin clothes and chlamys (Grotowski 2010, p. 235).

Figure 9.

Bilateral wooden-relief Vita icon of St George, Kastoria (Macedonia, Greece), second half of the 13th century. Byzantine and Christian Museum, Athens, BXM 1108. (a) General view of the side A of this bilateral icon: St George and his hagiographical cycle. Source: (Aχειμάστου-Ποταμιάνου 1998) (b) Detail of the side A of this bilateral icon: Shield of St George. © Author.

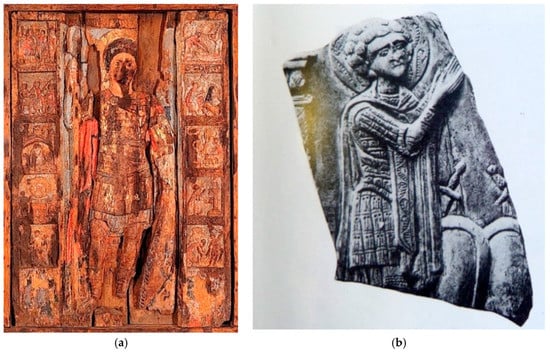

On the basis of comparisons with other icon-wooden reliefs, the piece has often been ascribed to the region of Kastoria, in Northern Greece (Grabar 1976, II, p. 156). In fact, the icon came from the church of Hagia Paraskevi in Kastoria and has been dated to the second half of the 13th century (Τσαμίσης 1949; Τσιγαρίδας 2016, pp. 92, 99). For some scholars, its hybrid character, which was defined as Byzantine-Gothic, had its sources in the Despotate of Epiros, in the sculpture of the impressive Panagia Paragoritissa (around 1290) (Marksimovi 1967, pp. 32–33; Xyngopoulos 1967, pp. 80–81; Aχειμάστου-Ποταμιάνου 1998). Notwithstanding this, in a pioneering study, G. A. Sotiriou did not hesitate to attribute the artwork to Constantinople, by invoking the high quality of the painted cycle of the passion of St George framing the high relief (Sotiriou 1930, pp. 178–80). The existence of another wooden Vita icon depicting a standing and beardless St. George in the National Art Museum of Kiev, which came from Kherson and dated to the 12th century, pointed to a similar origin (Grotowski 2010, p. 131; Mullins 2017, p. 98) (Figure 10a). Indeed, in both icons, a relief of a standing St George presides the panel and is surrounded by a rectangular frame depicting his passion.

Figure 10.

(a) Wooden Vita icon of St George, Constantinople, 12th c. (?). National Art Museum of Ukraine, Kiev. © With permission of the National Museum of Ukraine (Kyiv, Ukraine). (b) Fragmentary 12th-century steatite icon depicting St George praying, Constantinople (?), 12th c. Kiev, Museum of Western and Oriental Art. Source: (Kalavrezou-Maxeiner 1985).

Notwithstanding this, the Kastoria relief has the saint in a slightly different pose from that from Kiev. St George is now depicted in a three-quarter view, arising and folding his hands, in the act of praying to Christ. This gesture refers back to a specific group of 11th- and 12th-century icons made in steatite, which depict the standing warrior saints George and Theodore. As A. N. Tsigaridas pointed out the most convincing precedent for the St George from Kastoria is a fragmentary 12th-century steatite icon kept in Kiev (Museum of Western and Oriental Art) (Kalavrezou-Maxeiner 1985, n. 25, p. 1169), in which a very similar beardless and curly-haired saint is shown in the act of praying next to his shield (Τσιγαρίδας 2016, p. 97) (Figure 10b). Here, George raises his gaze towards the now-missing upper right section of the icon, in which there was probably a bust of Christ about to crown him. In Kastoria this part is occupied by Christ, who extends his arms to the praying saint from the arc of heaven. It is worth emphasizing that steatite icons were widespread across the Byzantine geography of private devotion (Kalavrezou-Maxeiner 1985, pp. 5, 63). From one perspective, it might be deduced that a piece like the the Kiev icon could have been used as a model by a local workshop to produce the wooden-relief kept in the Byzantine and Christian Museum in Athens. However, on the other hand, the monumental size and quality of the painted cycle point to production in Constantinople. Once again, this relief-icon could be a wooden representative of the renewal of sculpture associated with the Palaiologoi in the capital through the 13th century.

However, everything about this piece is puzzling, and for decades this extraordinary artwork has raised questions that led scholars to propose very different places for its production; Constantinople, Kastoria, the Latin Kingdom of Thessaloniki (1204–1223), Cyprus, and Epiros. Even the name of Irene Doukina Angelina Komnena, widow of the Bulgarian Tsar Ivan II Assen, has been related to the icon during her period of regency (1246–1253) by identifying her as the mourning woman depicted in proskynesis at the feet of St George.11 The icon also caught the attention of Hans Belting who considered it an outstanding product of the 13th-century art of the Mediterranean commonwealth, whose lingua franca was characterized by a hybridization of styles and forms in which the categories of Western and Eastern were blurred (Belting 1982).12 In an attempt to continue along this path, I have been wondering about the very specific coat of arms that decorates the triangular shield next to St George (Figure 9b,) and which has been usually disregarded by scholars. In an earlier publication (Castiñeiras 2016, pp. 44–45), I identified this blazon as belonging to the Genoese family of the Zaccaria, “écartelé d’argent et de gueules” (quartered in silver and red), who were Lords of Focea (1267?–1340) and Chios (1304–1329), and vassals of the Byzantine emperor (Miller 1921). More specifically, I felt emboldened to propose that this wooden icon could be a tribute to their most important member, Benedetto Zaccaria, Lord of Focea and Chios (+1307), who also was a celebrated admiral in the army of Michael VIII and Imperial ambassador in the West in 1282 (Miller 1921; López Sabatino 1933, pp. 63–73). What is more, it is very likely that to reinforce this bond with Byzantium and especially with Michael VIII, Benedetto married a member of the Imperial Family—a Paleologina—as we can deduce from the fact that he named his son and successor Paleologo (+1314) (Promis 1865, p. 8; López Sabatino 1933, pp. 10, 221). This hypothesis allowed me to suggest that the controversial wooden-relief icon had been made in Constantinople around 1307, the date of Benedetto’s death, by commission of his wife, who, kneeling, is depicted at the foot of Saint George. The pseudo-Kufic decoration of the edge of the shield seemed, at least in the first instance, to reinforce my thesis, because this kind of motif can be found in artworks that relate to the idea of victory over Islam. It worth noting that the fiefs of Focea and Chios were respectively given by Michael VIII and his son Andronico II to Zaccaria in order to protect the coast of Asia Minor from the threat of the Turks (López Sabatino 1933, pp. 224–25). Ultimately, the production and cult of such an icon might have helped to foster closer ties between the Genoese and Greek population—as a palladium for the protection of the island and its trade (Castiñeiras 2016, pp. 40–45).

However, the addition of Islamic motifs to a Byzantine artwork could be due to other reasons, especially if the icon is dated earlier, to the second half of the 13th century, in the context of fluid relations between the Byzantine rulers and the Seljuk states in Anatolia. In this case, as happened in other instances, the pseudo-Kufic decoration of its edge should be seen as no more than a symbol of high status that would evoke the luxury of the Seljuk carpets and precious objects so admired by the highest ranks of the Byzantine Empire (Redford 2004).

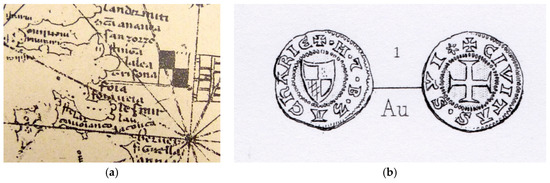

In fact, a more detailed analysis of the circumstances surrounding the piece has led me to discard my earlier hypothesis. First, there is no doubt about its provenance from Kastoria and liturgical function in the church of Hagia Paraskevi (Τσιγαρίδας 2016, p. 92, note 28). Second, the alleged Zaccaria shield seems to be a vague evocation of the Latin use of heraldry by the Byzantines. It is true that Martin and Benedetto II Zaccaria used a very similar coat of arms in the coins issued during their rulership in Chios (1319–1329) (Schlumberger 1878, p. 413, illustration XIV,1) (Figure 11b). However, the distribution of colors in the shield of the icon does not correspond exactly to coeval illustrations as shown in the in the portolan of Angelico Dalorto dated to 1325—Florence, Corsini Collection—in which the Zaccaria’s banner marking the port of Focea (Foca) shows a reversed setting of red and silver (Magnaghi 1898) (Figure 11a).

Figure 11.

Coat of arms of the Genoese family the Zaccaria in Chios. (a) Banner of the family Zaccaria marking the port of Focea (Foca), Angelico Dalorto’s Portolano, Genoa, 1325. Florence, Corsini Collection. Source: (Magnaghi 1898). (b) Coin of Martin and Benedetto II Zaccaria in Chios (1319–1329). Source: (Schlumberger 1878).

The icon from Kastoria provides an example of the Byzantine fascination for the use of coats of arms in Latin chivalry in the context of the turmoil of the 13th-century Greece (Grotowski 2010, pp. 246–48). As such, the artwork should be understood as a kind of appropriation of enemy fashion on the part of the Byzantines, just as the Latins had done with the Byzantine iconography of St Georges. Besides the attire and the blazon, everything in the icon is genuinely Byzantine. If the type and posture of the praying saint derives from the steatite icons, the inscription accompanying the figure on both sides -’O AΓΙOΣ ΓΕΩΡΓΙOΣ Ό ΚAΠΠAΔOΚHΣ- suggests that the iconographer (painter) was familiar with the Byzantine vitae of George. In fact, from the 7th-century George was recurrently named in the hagiographies with the gentilic: Γεώργιος ο Καππαδόκης (Walter 2003, p. 264; Krumbacher 1911, pp. 41, 60 and 297). Moreover, the inclusion in the cycle of two episodes related to Empress and Saint Alexandra, Diocletian’s wife, is worth highlighting: The conversion (Figure 12b) and the sentencing of the saint and Alexandra (Mark-Weiner [1977] 2003, p. 78). In my opinion, this conveys not only a knowledge of the 10th-century rhetorical vitae written by Theodore Daphnopates and Symeon Metaphrastes but also some familiarity with the Synaxarium Ecclesiae Constantinopolitanae, which celebrates her feast on 21 April (Delehaye 1902, cols. 619–20; Delehaye 1909, p. 76; Delahaye 1966, p. 285). Insistence on the prayer of St George, which was depicted twice, in the scene of the beheading on the right side and in the central image relief of the saint, should be also seen as a transposition into images of his last invocation to God before his death as is contained in the rhetorical version of Theodore Daphnopates: “Κύριε ό θεός μου, (…)” (Krumbacher 1911, p. 76).

Figure 12.

Bilateral wooden-relief Vita icon of St George, Kastoria, second half of the 13th century. Byzantine and Christian Museum, Athens, BXM 1108. (a) Kneeling widow at the feet of St George. (b) Conversion of Alexandra. © Author.

As Nancy Sevcenko pointed out it is very likely that the lady who is depicted at the feet on St George commissioned the icon on behalf of her dead husband (Figure 12a). This would explain the insistence of the composition on the idea of a double intercession before the saint (mourning widow) and God (warrior George) (Patterson-Sevcenko 1993–1994, p. 160).13 Thereby, the relief should be perceived as an allusion to the occupation of the deceased: Perhaps some high-ranking member of the Byzantine army, who was established in the stronghold of Kastoria in the years after the victory of Pelagonia. Local production of the icon seems confirmed by the formal composition that that can be perceived as a reference to the colossal and talismanic statues of George scattered in this area. However, we will never know why they decided to update the attire and shield of the saint warrior in order to convert it into a Byzantine solider disguised as a Latin. To show their fascination for Latin chivalry and its customs? Or perhaps to express support for the policy of Michael VIII in his approaching to the West after the Council of Lyon for the Union of the Churches in 1274?

2.3. Saint George under Catalan Rule

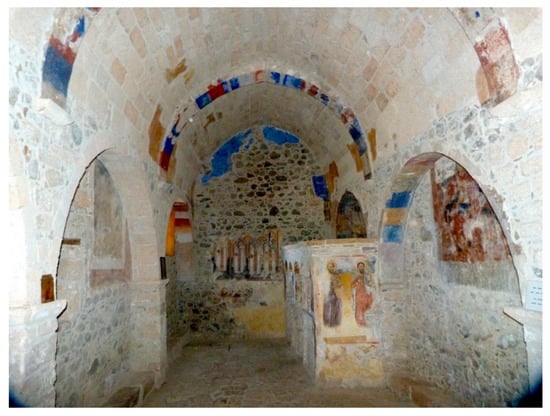

This paradoxical process of the affirmation of group identity and iconographic hybridity is equally seen in the 14th-century Catalan domains in Greece. By this, I am referring to the cases of Hagios Georgios in Afkraifnio (Karditsa, Thessaly) and the Castle of Livadia (Boeotia) in Central Greece, along with those of Hagios Georgios Katholikos (Paliachora) and Hagios Nikolaos Mavrikas, on the island of Aegina. In all of them, St George was a focus of expectation as the guarantor of community protection.

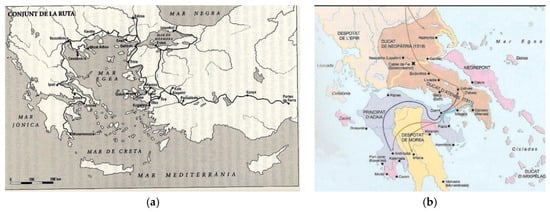

During the outstanding 14th-century expansion of the Kingdom of Aragon, the Catalans occupied extensive portions of Greece, namely the Duchies of Athens and Neopatria (1311–1388) and the island of Aegina (1317–1451) (Figure 13a,b).14 This brought significant numbers of people from Catalonia and Aragon into contact with Byzantium. As the Franks did it before, the Catalans, once settled in Greece, were also capable of developing a cross-cultural society. It should, however, be noted that there are significant differences between the social background of the Catalans who settled in Greece, usually referred to as ‘Almogàvers’, and that of the noble Frankish knights. First, they were predominantly an army of mercenaries whose origins can be traced back to the military campaigns of the Kingdom of Aragon in the 13th century which succeeded in conquering the Muslims realms of Mallorca and Valencia. Second, among them there were Muslim warriors (Fancy 2016, pp. 1, 53). They belonged thus to the multicultural society that characterized the Spanish kingdoms in the Middle Ages, in which shared sanctuaries and mixed marriages were tolerated (Remensnyder 2014, pp. 157–60). This meant that after the nomadic period of military campaigns and savage ravages in Anatolia and Greece (1303–1311), once they became settlers their modus operandi might be slightly more open than that of the Franks to the local population.15

Figure 13.

The Catalans in Greece and Anatolia. (a) Itinerary of the Grand Catalan Company (Almogàvers) (1303–1311). Source: (Nicolau d’Olwer 1974) (b) Catalan Greece in 14th century: Duchies of Athens and Neopatras. Source: (Hurtado et al. 1995).

This cross-cultural society especially developed in the countryside and peripherical areas, even though they promoted or attended the orthodox liturgy of the Greeks.16 In some cases, the monuments display inscriptions in Greek celebrating the Latin donor or ruler. These public texts along with the choice of images decorating the walls played a major role in the developing of this intercultural process, whose aim is to blur religious and ethnic frontiers and make churches space of interaction.17

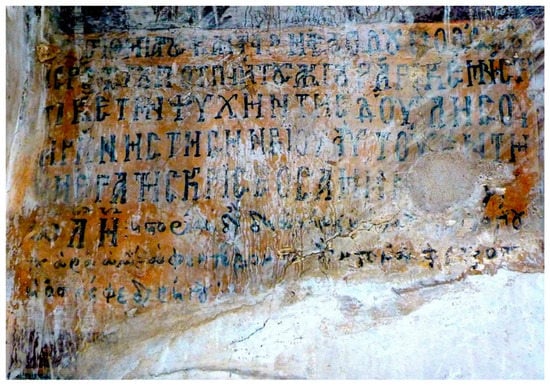

One of the most intriguing examples of this phenomenon is the church of Hagios Georgios in Akraifnio (Karditsa, Boeotia, Greece) (Figure 14a,b). This is a 12th-century cross-in-square building, which was probably renewed or simply repainted between 15 March and 31 August 1311, by the Frankish knight, Antoine le Flamenc, bailiff (bailo) of Thessaly.18 A puzzling and controversial dedicatory inscription painted above the keystone of an arcosolium to the south of the crossing provides this remarkable information (Figure 15). The inscription was firstly published by J. A. Buchon (1845) and W. Miller (1909), but new studies made by Alexandra Kostarelli offers a different and stimulating reading of the text (Kostarelli 2019; Kostarelli 2020). Miller holds that the inscription should be seen as a kind of memorial to Antoine le Flamenc as founder of the building (Miller 1909, p. 199). Having survived the Battle of Halmyros (15 March 1311), where the Catalans defeated the Frankish army and occupied the Duchy of Athens, he would not have hesitated to commission a church devoted to St George in order to thank him and be buried there (Miller 1908, p. 228; Miller 1909, p. 200).

Figure 14.

Hagios Georgios in Akraifnio (Karditsa, Boeotia, Greece). (a) Arcosolium with painted inscription (1311), south of the crossing; (b) angels blowing trumpets, right spandrel of the arcosolium. © Author with the permission of the Ephorate of Antiquities of Boeotia.

Figure 15.

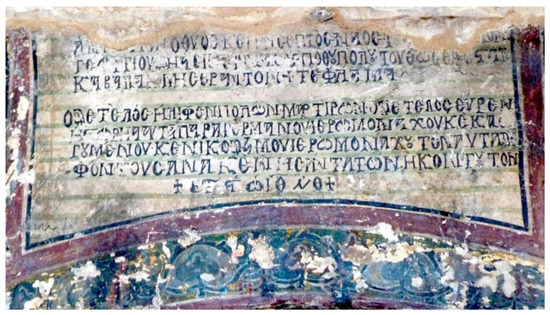

Dedicatory inscription painted above the keystone of the arcosolium (1311), Hagios Georgios in Akraifnio (Karditsa, Boeotia, Greece), south wall of the crossing. © Author with the permission of the Ephorate of Antiquities of Boeotia.

However, A. Kostarelli opposes this hypothesis on the basis of the architectural phases of the building and a new reading of the text. In her opinion, the arcosolium “was clearly not intended as a burial place for Lord Antoine Le Flamenc” (Kostarelli 2019, p. 11) and should be dated to the primary phase of the church before the time of the Frankish Lord.19 Secondly, it is very likely that the inscription was incomplete when Buchon published it in 1845 in a first attempt to read and reconstruct its content (Buchon 1845). Some decades later, in 1907, part of the plaster crackled and had to be restored as Miller explains in his 1909 publication (Miller 1909, p. 199). Indeed, the report of the analyses carried out in 2014 shows as the inscription was then partially repainted (Oikonomou/Karydis/Kostarelli 2014) probably following the first reading made by Buchon (Kostarelli 2019).

On the basis of a detailed critical analysis of the painted inscription, Alessandra Kostarelli offers a new interpretation, in which she corrects certain readings by Buchon and Miller. As can be seen below these amendments concern not only previous assumptions about Antoine le Flamenc as founder of the monument but also the hypothesis that he was buried there in recognition of the protection offered him by St George at the terrible Battle of Halmyros. Kostarelli proposes two main corrections. First, at the start of the first line—now almost lost—should be written AΝΙΣΤOΡΙΘH (“it was painted”) instead of AΝ[HΓΕΡ]ΘH (“it was raised”). Secondly, the fifth and sixth lines of the inscription, which are usually interpreted as OΔΕ ΤΕΛOC HΛΙΦΕΝ ΠOΛΩΝ ΜAΡΤΙΡΩΝ OΔΕ ΤΕΛOC ΕΥΡΕΝ (This is who received the end of many martyrs, this is the end that he found), should be rather spell OΔΕ ΤΕΛOC HΛΙΦΕΝ ΠOΛΩΝ ΜAΡΤΙΡ<I>ΩΝ ΩΔΕ ΤΕΛOC ΕΥΡΕN ἨCΤOΡHA (Such was the end of many toils. So, it came to an end this painted work…). Therefore, this would be the complete transcription of the painted text (Figure 15):

ĂΝΙCΤOΡΙΘH • OΘΥOC • ΚΕ ΠAΝCΕΠΤÒC • ΝAOC Τ[OΥ AΓΙOΥ ΜΕΓAΛOΜAΡΤΥΡOC]ΓΕΩΡΓΙOΥ • ΔHÄ CΙΝΕΡΓΙAC ℧ ΠOΘOΥ ΠOΛOΥ • ΤOΥ Θ<E>ΩCΕΒΕCΤAΤOΥΚAΒAΛAΡΙ ΜHCΕΡ AΝΤOΝH • ΤΕ ΦΛAΜA ~~~~~~OΔÈ ΤΕΛÓC•HΛΙΦÉΝ ΠOΛΩΝ ΜAΡΤΙΡ<Í>ΩΝ•OΔΕ ΤÉΛOC ΕÝΡΕΝἨCΤOΡHA AΥΤΕΙ ΠAΡA ΓΕΡΜAΝOΥ • ΙΕΡΩΜOΝAΧOΥ • ΚÈ ΚA[ΘH]ΓOΥΜÉΝOΥ • ΚΕ ΝΙΚOΔΕΙΜOΥ ΙΕΡΩΜOΝÁΧOΥ • ΤÒΝ AΥΤAΔÈλΦOΝ • ΤOΥC AΝAΚÈΝHCAΝΤA<C> ΤΩΝ HΚOΝ ΤOΥΤOΝ+ ΕΤOΥC, ČΤΏΙ͠Θ (ỈᵔΝΔΙΚΤΙΩΝOC) Θ +

Ἀνιστορήθη ὁ θεῖος καὶ πάνσεπτος ναός τοῦ ἁγίου μεγαλομάρτυροςΓεωργίου διὰ συνεργίας καὶ πόθου πολλοῦ τοῦ θεοσεβεστάτουκαβαλάρη μισὲρ Aντώνη τε Φλάμα ~~~~~~ὅδε/ὧδε τέλος εἴληφεν πολλῶν μαρτυρίων. ὅδε/ὧδε τέλος εὗρενἱστορία αὕτη παρὰ Γερμανοῦ ἱερομονάχου καὶ καθη-γουμένου καὶ Νικοδήμου ἱερομονάχου τῶν αὐταδέλ-φων τοὺς νακαινίσαντας τὸν οἶκον τοῦτονἔτους, ČΤΏΙ͠Θ ἰνδικτιῶνος Θ΄

(This godly and sacred church of the holy great martyr George was (re)painted with the assistance and great desire of the most God-respecting knight sir Antoni te Flama. Such was the end of many toils. So came to an end this painting, work by Germanus the priest-monk and monastery head and Nicodemus priest-monk, these two being brothers who renovated his church + year 6819 indiction 9th+).(source of transcription and translation: Kostarelli 2019, pp. 20–21)

Once this new reading of the painted inscription is accepted, I would like to review some of the Kostarelli’s conclusions. I agree that Antoine le Flamenc simply renewed an existing church devoted to Saint George with a cycle of paintings, but I am convinced that his main purpose was to shelter his own burial. According to the inscription, the Greek monks and brothers, Germanos and Nikodemos, carried out this renewal in order to fulfil Antoine’s commission. It consists of a pictorial embellishment of the earlier church that probably also entailed a place for the knight’s burial. This was located, under an arcosolium as happened in other contemporary Byzantine (Chora in Constantinople) and Latin churches (Cathedral of Our Lady of Athens sited in the Parthenon and now in the Byzantine and Christian Museum) (Ivison 1996, pp. 92–93; Lock 1995, p. 219; Kalopissi-Verti 2007, pp. 24–27). According to Kostarelli, the tomb predates Flamenc and was consequently reused for the burial of this Frankish knight (Kostarelli 2020).

The setting of the painted dedicatory tabula over an Apocalyptic cycle indeed points to a funerary and memorial intention. So, on the spandrels of the arcosolium, on both sides of the inscription, there are two angels blowing trumpets to announce the beginning of the Last Judgement (Figure 14b). Moreover, in the intrados of the arch there are two stirring angels related to the opening of the Sixth Seal. On the left, one angel is rolling up the heavens like a scroll (Rev 6, 14), with the Sun and the Moon becoming black and red (Rev 6, 12) and the stars falling (Rev 6, 13) (Figure 16a). On the right, another angel is removing the mountains (Rev 16, 14) (Figure 16b). A very similar apocalyptic depiction of the angel rolling up the heavens was included, only a few years later, as a central subject in the vault of the parekklesion of Chora (Kariye Camii, Istanbul, 1315–1321), over a funerary space full of arcosolia (Figure 17).

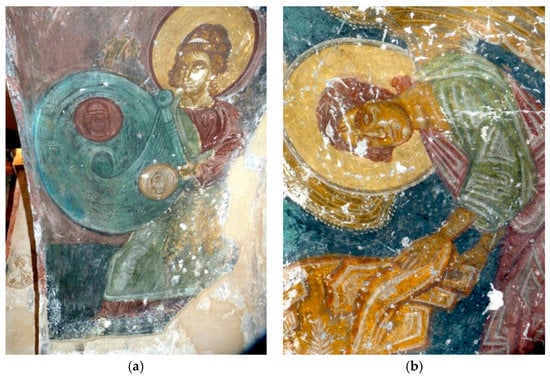

Figure 16.

Apocalyptic angels (Rev 6, 12–14) in the intrados of arcosolium (1311), Hagios Georgios in Akraifnio (Karditsa, Boeotia, Greece), south wall of the crossing. (a) Angel rolling up the heavens. (b) Angel removing the mountains. © Author with the permission of the Ephorate of Antiquities of Boeotia.

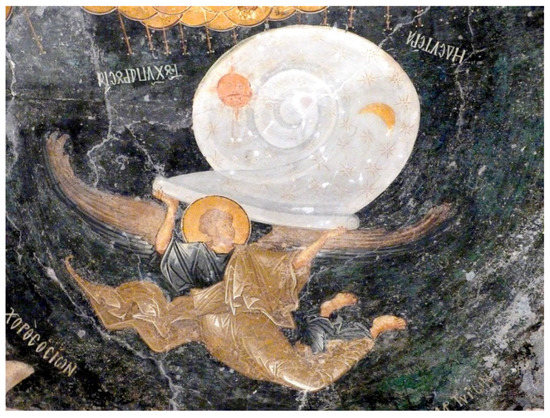

Figure 17.

Apocalyptic angel rolling up the heavens (Rev 6, 14), domical vault of the parekklesion of Chora (Kariye Camii, Istanbul) 1315–1321). © Author.

Unfortunately, the painting decorating the south wall under the arcosolium has faded. The only trace is an irregular blue layer. This colour also appears as background in the upper part of the arcosolium and in the endonarthex, both belonging to the renewal carried out by Antoine Le Flamenc. It is not possible to determine which was the subject, but it should have been related to the apocalyptic angels depicted on the inner arch. Thus, it seems likely there was a scene of the Last Judgement as in the domical vault in the parekklesion at Chora or perhaps a portrait of the donor(s) before a holy figure as in the tomb of Michael Torniakes in the same Constantinopolitan monument (Akşit 2010, pp. 178–79, 190–91). This last possibility would mean that in Akraifnio there could have been a depiction of Antoine le Flamenc together with Saint George. The formula of donor portrait together with his holy protector was had been common in this area since the 13th century, such as we can see in Porta Panagia (Thessaly, ca. 1283) (Kalopissi-Verti 1992, p. 99) (Figure 18a), the aforementioned arcosolium at the Chora in Istanbul (14th century), or at the church of the Archangel Michael at Kavalariana (Crete) (Lymberopoulou 2006, pp. 176–77). The omnipresence of late depictions of equestrian figures of St George in Akraifnio church, both on the north wall (16th c.?) (Figure 18b), just opposite to the tomb, and on the interior tympanum of the 19th-century addition, is worth noting. Hence, it seems reasonable to consider that the 14th century renewal of Antoine le Flamenc might have included a depiction of the saint as in many other churches devoted to the warrior from Cappadocia.

Figure 18.

(a) Funerary portrait of sebastokrator Ioannes Angelos Komnenos Doukas, arcosolium esonarthex, Church of Porta Panagia (Thessaly), ca. 1283; © Used with permission of Anastasios Papadopoulos. (b) St George slaying the dragon (16th c. (?), Hagios Georgios in Akraifnio (Karditsa, Boeotia, Greece), north wall of the crossing. © Author with the permission of the Ephorate of Antiquities of Boeotia.

Besides the painted inscription, there is some significant information collected in chronicles and records about our donor that allows us to draw up a brief biography. According to the Livre de la Conqueste, a French version of the Chronicle of Morea written between 1332 and 1346, Antoine le Flamenc was named bailiff and lieutenant in Thessaly by Guy II de la Roche, Duke of Athens (1287–1308) in 1303. The Frankish knight became Lord of Karditsa and was described in the same book as “un des plus sages hommes de Romanie” and “le plus sage dou duchame” (Miller 1908, p. 200; Miller 1909, p. 200). His name and that of his son, Jean, appeared later in some Frankish and Venetian documents, even after the battle of Halmyros (15 March 1311), where the Catalans defeated the Frankish army in order to occupy the Duchy of Athens (Miller 1909, p. 200). Indeed, the name of Ser Antonius Flamengo miles is mentioned still alive among the Greek dignitaries that have relations with Venice in a list dated to 1313 (Dynastiae Graeca; Hopf 1873, p. 178). This means that he did not perish in 1311 in the Battle of Halmyros, in which the Franks were massacred by the Catalans.

In this regard, there two main points that should be better discussed for a better understanding of the monument and its painted inscription. First, it is likely that after the Battle of Halmyros, Antoine agreed with the Catalan Company to continue as Lord of Karditsa (Lock 1995, p. 122). It is worth noting that the knight had a good relationship with the leaders of the Almogàvers. In a Venetian document of 1308, Antoine had been accused together with Guy II, Bernart de Rocafort—an ambitious chief of the Catalan Company (1307–1309), and Bonifacio da Verona, Lord of Karystos and the future father-in-law of Alfons Frederic, to plot to take over the entire island of Euboea (Marcos Hierro 2005, p. 310). Furthermore, in 1310 the Catalan Company had been hired by the Duke of Athens, Walter V de Brienne, to conquer some strongholds in the Despotate of Thessaly in order to protect the northern frontier of the Duchy, whose bailiff was then Antoine le Flamenc (Soldevilla et al. 2011, chapter 240, pp. 396–97; Marcos Hierro 2005, pp. 322–24). So, as a survivor of the Battle of Halmyros, Antoine was probably able to negotiate his continuation as Lord of Karditsa. It is not true that “the Catalan brothers Galceran and Francesch de Puigpardines succeeded Anthony in the lordship of Cardanica, that is, Karditsa” as Alessandra Kostarelli states (Kostarelli 2019, p. 15). The first mention of these members of the lineage of Puigpardines as Lords of Karditsa is very late, in 1381, within a list of ecclesiastical and laity authorities in the Catalan Greece under the kingdom of Peter the Ceremonious, in which we can read “Item Galceran de Puigpardines e Francesch germá seu, senyors de la Cadarniça e dela Talandi” (Rubió I Lluch 2001, p. 548, doc. n. CDLXXXIX).

Another important point to discuss is the original location of the battle between the Franks and the Catalans in 1311. According to Ramon Muntaner’s Chronicle, chapter 240 (Soldevilla et al. 2011, pp. 397–98) and Nicephoros Gregoras’ Byzantine History (VIII, vii, paragraph 5) (Morfakidis 1981, p. 177), the battle took place “on a beautiful plain near Thebes”, beyond the river Kephissos, wherein there was a marsh which the Catalans used as shield against the Franks (Morfakidis 1981, p. 177) (Marcos Hierro, pp. 326–27).20 This description has led scholars such as Carl Hopf and William Miller (Miller 1908, pp. 227–29) to identify the place with the plain of the Boeotic Kephissos and the marshes of Lake Copais (now drained), near Akraifnio. However, in 1974, David Jacoby wrote a compelling article that disputed this location. According to this scholar the fight was held in Halmyros (Almyros), in Thessaly, a town sited in the Gulf of Volos, as the earliest sources of the event report. Thus, the Greek version of the Chronicle of Morea (ca. 1320) says that Walter V of Brienne, Duke of Athens, was killed in Halmyros by the Catalan Company (“ἐκείνων που εσκοτώσασιν στον ‘Aλμυρό η Κομπάνια”) (Egea 1996, 8010, pp. 396–97). Likewise, the renowned Venetian statesman and writer, Marino Sanudo the Elder, who was a galley captain operating in the North Euboean Gulf on the day of the battle, both in Istoria di Romania (1326–1327) and in a letter dated to 1327 states that the fight place at Halmyros (Jacoby 1974, pp. 223–32).

In Jacoby’s view, when Muntaner mentions Thebes, he probably mistook the Phthiotic Thebes—close to Halmyros, in Thessaly—for Boeotian Thebes, which is further south (Jacoby 1974, p. 230). It is worth noting that Muntaner abandoned the Catalan Company in 1307 and therefore was not an eyewitness to these events. Besides, when he wrote his Chronicle some years later, in 1325–1328, his narrative is biased and manipulative (Cingolani 2015, p. 101–16). Gregoras, in his Byzantine History, which is still later, written in 1349–1351, furthered the misunderstanding by including a precise reference to the river Kephissos (Morfakidis 1981, p. 177); so that he would have been the first to identify the marshes of Lake Copais—now drained and very close to the Byzantine Akraifnio—with the place of the battle. As Jacoby pointed out in 1311 the Catalans were in Thessaly—in the area of Demetrias, Halmyros—and not in Boeotia. Besides, just some days before the battle, on 10th March 1311, the Duke of Athens had assembled his troops at Zetouni (modern Lamia), a perfect place to launch an attack on their northern opponents (Miller 1908, p. 226).

Although Muntaner states that all the knights of the Principality of Morea died in the battle and only two escaped—Boniface of Verone and Roger Deslaur—this must be an exaggeration (Soldevilla et al. 2011, p. 398). It is true that in the aforementioned list of Dinastiae Graeciae (1313) collecting the names of the lords of Romania, some of them are marked as “decessit” or “mortuus”, such as “Ser Albertus Paravicinus”, “Ser Giorgios Gisi”, or “Ser Thomas de la Sola”. Notwithstanding this, there are remarkable exceptions as “Ser Bonifacius of Verona”—who is also mentioned by Muntaner—and “Ser Antonius Flamengo miles” (Hopf 1873, p. 178). This means that Antoine le Flamenc, Lord of Karditsa, also survived the battle, and probably received the same privileges as his colleagues Boniface of Verone and Roger Deslaur. They not only kept their titles and lands but had the opportunity to increase their status. Roger Deslaur, who finally agreed to become chief of the Catalan in company (1311–1312), became the new Lord of Salona (Soldevilla et al. 2011, p. 398). It was therefore dealing with a policy of agreements that allows to create a Frankish-Catalan society based on the idea of continuity.

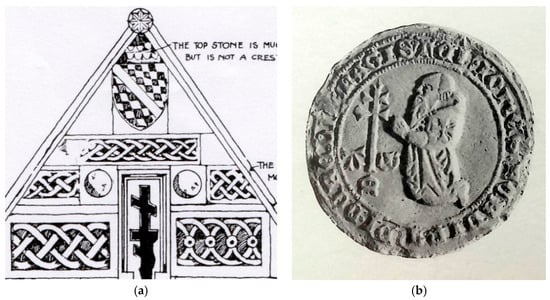

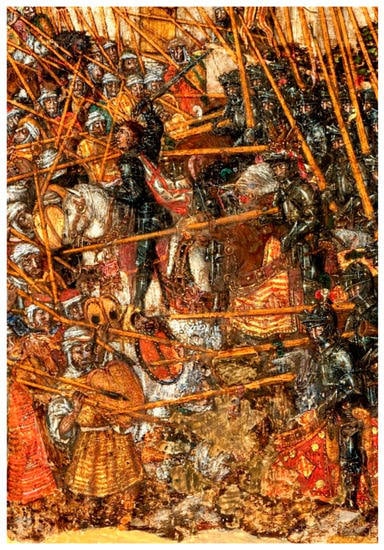

That is why the renewal carried out by Antoine le Flamenc in the church of Akraifnio should still be seen as proof of the devotion of the Lord of Karditsa, Antoine le Flamenc, to St George as patron saint, as well as to the fulfillment of a particular vow. Although, it is true that the inscription over the arcosolium only reports the year of the work, 1311, without any further specification. In my view, the best context for the works remains after the Battle of Halmyros. It is likely that before this fight, most Frankish knights will have made their wills or expressed their last wishes in preparation for possible death. Indeed, on 10th March 1311, just five days before the combat, the Duke of Athens, Walter V de Brienne (1278–1311), assembled his forces at Lamia and made his last will and testament, which included different amounts of money to the most important Latin churches in Greece; the cathedrals of Our Lady of Athens, Our Lady of Thebes, and Our Lady of Negroponte, the great churches at Argos and Corinth, the church of Daulia, the Athenean and Theban Minorities, the Theban Frères Prêcheurs, and the church of St George at Livadia (“à Saint Jourge de la Levadie, cent parares”), as well as recording his wish to be buried in the abbey of Daphni (Miller 1908, pp. 226–27; Setton 1973, p. 4).

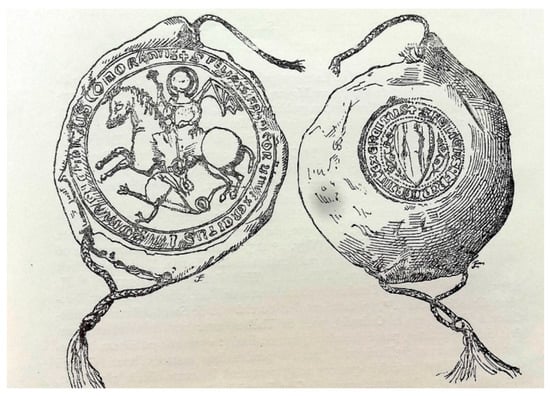

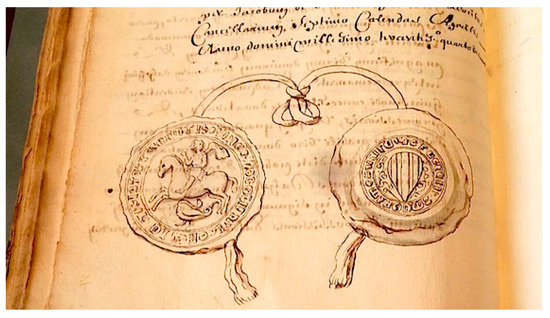

It is worth noting that the special gift of 100 hyperperi to the church of St George in Livadia is evidence of the apotropaic function of this saint in all Latin Greece. The Castle of Livadia, in Central Greece, had a special reputation in Latin Greece for keeping a fragment of the cranium of St George. This had probably been brought by the Franks from the Imperial Palace in Constantinople after the sack of the city in 1204. It is likely that Othon I de la Roche, first Duke of Athens (1204–1225) and Thebes (1211–1225), was the person responsible of this translation. Indeed, in 1214 he donated this castle to the Holy See and received it back from the Church, agreeing to pay for it a feudal fief of two marks a year. This was a way to restrict diocesan authority over the castle, its relics and the town, and to ensure some church revenues of the town for himself (Setton 1976, I, p. 214; Χαραμαντίδης 2002, pp. 83–85). Being St George the patron of knights and Crusaders, this relic of Livadia was considered a precious talisman for the Franks and later, for the Catalans, who even refused to send it to Barcelona despite repeated requests form by the Catalans kings who longed for it (Setton 1974, pp. 13–17; Ayensa i Prat 2013, pp. 153–56).

Thus, the gift of Walter V de Brienne in 1311 to Livadia must be seen as a vow to the warrior saint who had protected the Duchy of Athens since the time of Othon I. It is no coincidence that the date of the renewal works in Akraifnio was this same year. The most plausible explanation is that since Antoine survived the carnage of Halmyros and renewed his position as Lord of Karditsa, he embellished the orthodox church of St George in order to fulfill a vow made before the battle. This probably happened between March 15th, the battle day, and August 31st, the last day of the year according to the Byzantine calendar. As we have seen, the project probably also entailed Antoine’s potential burial the depiction of St George as patron saint. This makes most sense of the meaning of the sentence translated by Kostarelli as “Such was the end of many toils. So, it came to an end this painting work (….)”. This is not a reference to the warrior’s death, but rather a way of expressing that the work was done quickly, in just half a year.

Once again, the choice of an Orthodox church to celebrate the memory of a Latin Lord and the fact that two Greek monks and brothers, Germanos and Nikodemos, carried out this project is a sign of the multicultural society that characterized Greece under the Latinokratia, especially in the countryside, where Latin lords did not hesitate to attend Orthodox services or hire Greek artists. All this agency took place under the protection of St George. His cross-cultural character had the capacity to tie bonds among different communities. Local Greeks, Frankish Lords, and even Catalans could share this common space under the protection of “the holy great martyr George”. Ultimately, during the battle of Halmyros both sides, Franks and Catalans, entrusted their lives to St George.

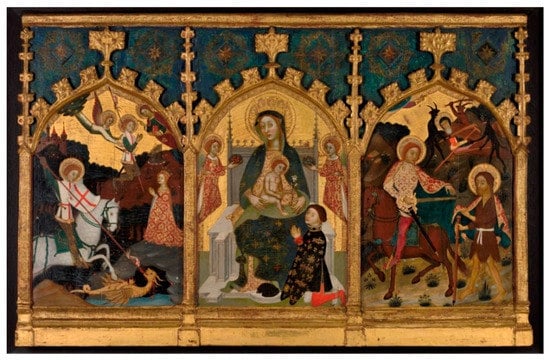

Notwithstanding perceptions of the rudeness of the Catalans who settled in Greece, it is likely that they were perfectly capable of developing a syncretic society as did their predecessors, the Franks. This seems to have been the case at Paliachora—today an abandoned city perched on a hill in the middle of the island of Aegina, in the Saronic Gulf—but which came under Catalan rule for almost a century and a half (1317–1451) (Figure 19a,b). The best buildings in Paliachora—a kind of humble Catalan Mystra—date to the 14th century when the island was under the rule of Alfons Frederic (1317–1338) and his descendants (1338–1394) (Nicolau D’Olwer 1935; Setton 1948, p. 108–12; Ayensa i Prat 2013, pp. 87–89). According to the art-historical study carried out by Ermioni Karachaliou, this seminal period saw the construction of the churches of Hagios Georgios Katholikos, Hagios Dionysios, Hagios Ioannis Prodromos, Hagios Euthymios, Hagios Nikolaos of the North, and Hagios Ioannis Theologos. Most are painted with frescoes of the same period (Karachaliou 2012, p. 42)

Figure 19.

(a) The island of Aegina in the Saronic Gulf. Source: (Pennas 2005); (b) city of Paliachora on the top of a hill, island of Aegina. © Author.

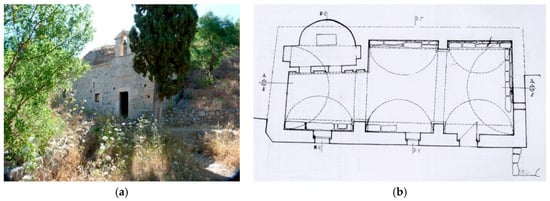

As I previously published, the plan of the village is arranged in a way that seems linked to Catalan tradition. The main churches—Hagios Georgios Katholikos, Hagios Ioannis Theologos—are surrounded by squares and enclosed by low stone walls designed to protect the holy ground around the sanctuary, as had been the case of the sagreres in Catalonia since the 11th century (Castiñeiras 2016, p. 16).21 Secondly, some of the churches—Hagios Georgios Katholikos, Hagios Ioannis Theologos—employ forms that are alien to Byzantine architecture—such as pointed vaults, heraldic crosses, and gabled bell-cotes—all of which can be found in rural parish churches belonging to the Military Orders in Catalonia, especially in the province of Tarragona (Castiñeiras 2016, pp. 32–33). Finally, in churches with predominantly Byzantine features (cross-in-square plan) and that were probably consecrated to the orthodox liturgy, the name of the Catalan ruler or patron is publicly displayed in a Greek votive inscription (Hagios Nikolaos Mavrikas, Hagios Ioannis Theologos) (Castiñeiras 2016, pp. 24, 33).

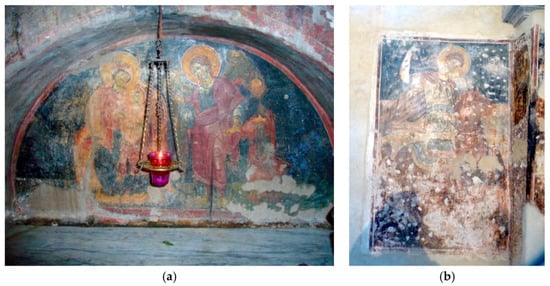

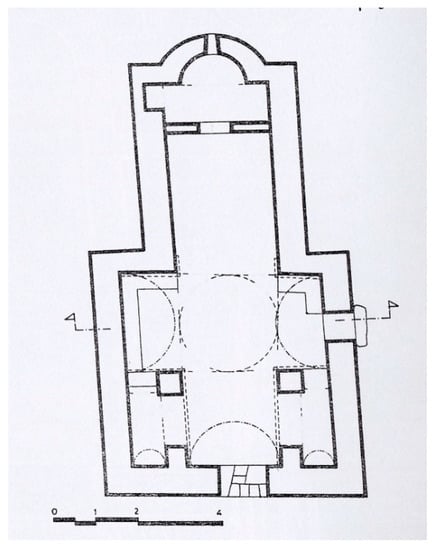

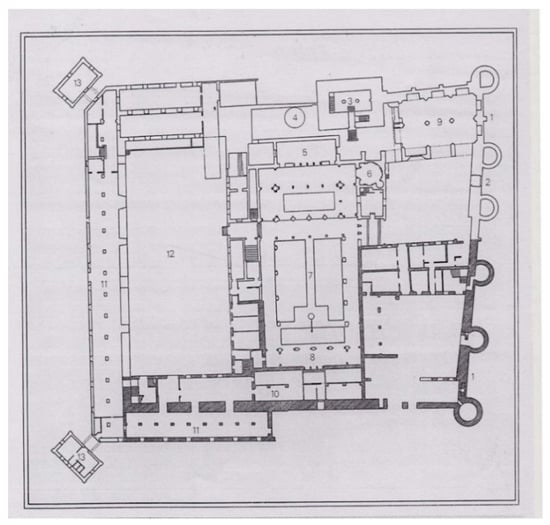

One of the orthodox churches, Hagios Nikolaos Mavrikas, deserves comment given the political implications of its inscriptions and its monumental depiction of St George. This is a 12th-century cross-in-square domed church, sited on the outskirts of the city, with an eastward extension made in the 16th century (Μουτσόπουλος 1962, p. 161) (Figure 20). The most remarkable feature of the building is the 14th-century cycle of paintings decorating the crossing, which includes two votive Greek inscriptions, both of them giving the date 1330. While that in the north arm adds the names of three lay donors—Sir Vasilissios Taratro (?), Michael, and Theodore Plakotianos—and their families, the other in the south arm mentions the priest Theodore, his wife Irene, the Catalan ruler, Alfons Frederic, and that of the painter, George of Aras (Δημητρακόπουλος 2009, pp. 350–51).

Figure 20.

Ground plan of the church of Hagios Nikolaos Mavrikas (Aegina). Source: (Μουτσόπουλος 1962).

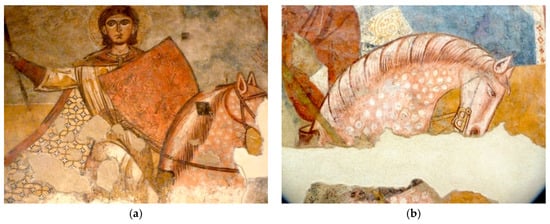

Some scholars consider the paintings to have been executed in two different phases on the basis of their stylistic features (Μητσάνη 2001; Pennas 2005, p. 75). The first would date to the 13th century, with impressive depictions of the Pantokrator and St George on horseback with spear and dragon, respectively sited on the north and east wall of the north arm of the crossing (Figure 21a,b). The second may correspond to the year 1330, as provided by the inscriptions, and encompass scenes of the Raising of Lazarus, the Birth of the Virgin, the Pentecostest, Saint Basil, and the Virgin Chalkoprateia, all of them depicted on the west wall of the crossing. However, it is more likely that the whole of the pictorial programme was carried out in one go by two different painters in 1330, during the Catalan period (Castiñeiras 2016, pp. 23–28).

Figure 21.

Mural paintings in the crossing of Hagios Nikolaos Mavrikas (Aegina), ca. 1330 (a) St George, east wall. (b) Pantokrator, north wall. © Author with the permission of the Ephorate of Antiquities of Western Attica, Piraeus, and Islands.

Given its exceptional importance for my research, I will first focus on the inscription that publicly displayed the name of the Catalan ruler in the south arm of the crossing (Figure 22 and Figure 23):

HCΤOΡΙΘH H ΠAΡOΥCA ΚAΜAΡA ΔHA ΕΞOΔOΥ ΘΕOΔΩΡOΥIEPEOC TOY ΠOΤ(Ε) ΠAΠA ΤOΥ CAΚΤOΥΡAΡΙ KE MNHCTHTI K(YPI)E THN ΨΥΧHΝ THC ΔOΥΛH(C) COYHPHNHC TH(C) CHNBIOY AYTOY EN THHMEPA THC KPICEΩC AMHN (ETOYC) ϚΩΛH: ηστορίθη δε δηά χηρ(ός) κ[αμού γεω]ργίου του αρά αμήν:Aφεντέβοντος δε ντον αλφ---οςηός ρέ φεδερήγουTHIS ARCH (chamber or vaulted space?) WAS PAINTED AT THE EXPENSE OF THEODOROS/THE PRIEST {SON?} OF THE FORMER PRIEST THE ACTUARIUS AND REME/MBER LORD THE SOUL OF YOUR SERVANT/EIRENE HIS WIFE IN THE/JUDGEMENT DAY AMEN (YEAR) 6/838: painted by the hand of myself George of Aras amen:/during the reign of don Alfonso/son of king Federick22

Figure 22.

Dedicatory inscription (1330), Hagios Nikolaos Mavrikas (Aegina), south arm of the crossing, west wall. © Author with the permission of the Ephorate of Antiquities of Western Attica, Piraeus, and Islands.

Figure 23.

Dedicatory inscription (1330), Hagios Nikolaos Mavrikas (Aegina), south arm of the crossing, west wall. © Author with the permission of the Ephorate of Antiquities of Western Attica, Piraeus, and Islands.

Firstly, it is notable that both inscriptions in the church are written in capital letters. This is common in monumental inscriptions and icons. The use of capital letters derives from Antique uncial writing and conveyed prestige and authority. However, the reason for the display of capital letters in these humble churches is also based on the fact that in Byzantium elementary education used capital letters (Cavallo 2017, pp. 60–63). Even a middle-trained man (spoudaios)—as many of the middle-class Greek society (administrators, priests)—learnt to read and write in capital letters. This meant that most villagers would have been semi-literate because they were not able to read in lower-case letters.

Hence, the significance of the addition of a final section in lower-case in the inscription. This only refers to the signature of the painter and to mention to the Catalan ruler. This means that the painter was capable of writing in lower-case letters, so that he was probably literate though as his spelling in the first part of the inscriptions is poor, it is likely that he was in the category of a spoudaios. Only genuine scholars—perittoi—had the capacity to write and read in perfect lower-case letters (Cavallo 2017, pp. 74–75). It could be concluded that the painter added this final formula in lower-case as proof of modesty as well as to record in writing that the island was “under the rule of the Catalans”.

The formula used to state that the paintings were undertaken “during the rule of Don Alfonso, son of king Frederick—αφεντέβοντος δε ντόν αλφ (…)ος/ηός ρέ φεδερήγου)—seems to be taken from a diploma. Don Alfons Frederic d’Aragó (Alfonso Fadrique in Spanish) (1290/94–1338), was a natural son of king Frederick II of Sicily, who became chief (presidens) of the Catalan Company (Societas Magna Romaniae) and Vicar General of the Duchy of Athens between 1317 and 1330. He was brought up in Barcelona, at the court of his uncle, King James II of Aragon, and in 1317 married Marulla, daughter of the aforementioned Boniface of Verona, Lord of Karystos and Aegina. After Boniface’s death in 1317/1318 Alfons became one of the most powerful men in Latin Greece by accumulating his wife’s dowry (Karystos and Aegina). This consolidated his position as military leader in the Duchy of Athens (1317), while some conquests in southern Thessaly—Neopatras, Zetounion, Loidoriki, Siderokastron, Vitrinitsa, Domokos, and Farsala—allowed him to incorporate the Duchy of Neopatras to the Catalan domain. From 1319 he was Vicar General of the Duchies of Athens and Neopatras and 1320 became Lord of Salona (Amphissa), the most important lordship in Catalan Greece. Finally, in 1330, Alfons was granted the title Count of Malta and Gozzo, though he remained in Greece until his death (Setton 1948, pp. 28–35; Ayensa i Prat 2013, pp. 319–20).

This reference to a Latin Lord and his royal lineage is quite exceptional in an Orthodox church, especially in Aegina, where some decades earlier (1289) in Omorphi Ekklesia, the Greek inscription only mentioned the emperor Andronikos II Palaiologos and the Patriarch of Constantinople, Athanasios I, and ignored the Frankish rulers of the island (Kalopissi-Verti 2014, pp. 396, 416)

As such, the inscription reflects a change in the self-perception of the Orthodox community in Aegina, which was probably looking to obtain protection from its new Latin and powerful Lord. Behind this shift of identity from Rhomaios to Catalan lies a recognition of the foreign authority. The year 1330 marked the onset of Turkish raids to capture slaves in the Aegean islands, which according to Marino Sanudo the Elder was especially aggressive in the years 1331–1332, when 25,000 Greeks were seized to be sold (Zachariadou 1983, pp. 160–61). This period was a turning point in relations between the Catalans and the Venetians, as in 1331 both parties signed an agreement in which “the Catalans should conclude no new alliances with the Turks and should not aid them in attacks upon the island of Negroponte or any of the lesser islands of the Archipelago” (Setton 1948, p. 35; Lemerle 1957, p. 88). However, it must be recalled that the Catalans also participated in this market for Greek slaves in their own raids in Epiros and Korinthos (Duran i Duelt 2018, p. 130). This particular context of fear would be the most auspicious time for the local population in Aegina to seek protection from the almighty don Alfons Frederic. The crowd-funding system, which is attested by both inscriptions probably involved the most important people in the village—Sir Vassilios Taratros (?), Michael and Theodore Plakotianos, and the priest Theodore—who were eager to be protected by their new Latin Lords. Furthermore, the church elected for this collective agency was devoted to St Nicholas, patron of sailors and shipping, an activity that was fundamental during the Catalan period given the island’s situation in the middle of the Saronic Gulf (Castiñeiras 2016, p. 25). This example of cultural fusion and mutual acceptance between the two ethnicities has a contemporary precedent in the Cretan church of Saint Michael in Kavalariana (Kandanos, Selinou) (1327–1328) (Figure 24), in which the Greek donors are depicted wearing Latin-like clothes—with heraldic motives—and accompanied by an inscription that states that the island was then ruled by “the great Venetians, our Lords” (Lymberopoulou 2006, pp. 176–77).23

Figure 24.

Lay donor under the protection of the Archangels Michael and Raphael, 1327–1328, church of the Archangel St Michael in Kavalariana (Kandanos, Selinou) (Crete), north wall. © Author.

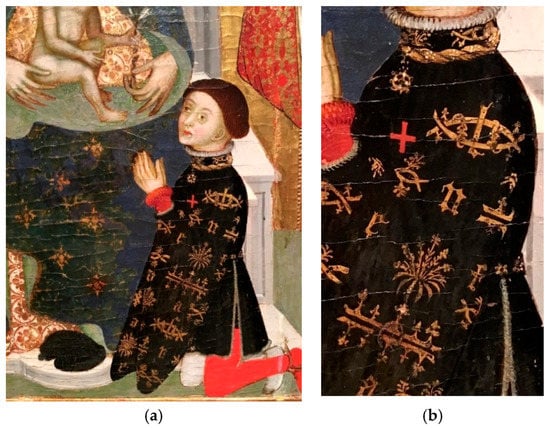

It is not by chance that the most conspicuous subject depicted in Hagios Nikolaos Mavritas is that of St George killing the Dragon. As stated above, this depiction along with that of the Panktokrator were dated to the 13th century on the basis of some stylistic similarities to the paintings of St. Peter at Kalyvia-Kouvara (Attica) (1232/33), such as the rendering of the eyes and the contours of the face.24 However, as far as the image of St George is concerned, the pictorial features and motifs are more akin to that of the Frankish gate house in the citadel of Nauplia. They have the same voluminous curly hair crowned by a diadem and he wears an oblong shield hanging over his back. The date that Monika Hirschbilder proposed for Nauplio, between 1291 and 1311 (Hirschbilchler 2005b), acts perfectly well as a terminus post quem for Hagios Nikolas Mavritas, and better fits the date of the painted inscriptions in Aegina (1330). Indeed, the dark shading along the profile of face and eyes and the aristocratic poise of St George in Aegina are generally characteristic of the Palaiologan art.