Abstract

This article reexamines the gold necklace excavated from the Sui-dynasty tomb of Li Jingxun (李静训, 600–608 CE), shifting attention from stylistic attribution to ritual function and funerary context. While previous studies have emphasized Persian, Byzantine, or Indian influences, this study situates the necklace more plausibly within the Iranian–steppe cultural sphere and the Turkic–Sogdian exchange networks active along the Silk Roads in the late sixth and early seventh centuries. Through analysis of its segmented structure, polyhedral gold beads, pearl rondelle, nicolo intaglio clasp, and gemstone arrangement, the article identifies close technical and visual parallels in Central Asia and the wider Iranian world. The necklace is interpreted as an apotropaic object likely worn in life and placed in the tomb to extend its protective and guiding functions after death. Attention to bodily use, clasp orientation, and associated grave goods—especially a stemmed cup with Eurasian ritual associations—clarifies how the necklace operated within a Buddhist burial setting timed to Lichun 立春 (Beginning of Spring). Situating the object within the Li family’s Xianbei 鲜卑 background and documented connections with Sogdian communities, this study demonstrates how foreign ornaments were actively understood and integrated into Sui aristocratic funerary practice, rather than adopted as passive luxuries.

1. Introduction

In 1957, archaeologists excavated a Sui-dynasty tomb near Xi’an (ancient Chang’an 长安), revealing the exceptionally lavish burial of Li Jingxun 李静训 (600–608 CE), a nine-year-old girl born into the highest ranks of the Sui aristocracy. Raised in the palace by her grandmother Yang Lihua 杨丽华, Li Jingxun died while accompanying the emperor on an imperial inspection tour. Her body was returned to the capital and buried within Wanshan Monastery 万善寺, a royal Buddhist nunnery near the palace, with a pagoda erected above the grave (Zhongguo Shehui Kexueyuan Kaogu Yanjiusuo 1980, pp. 3–28).

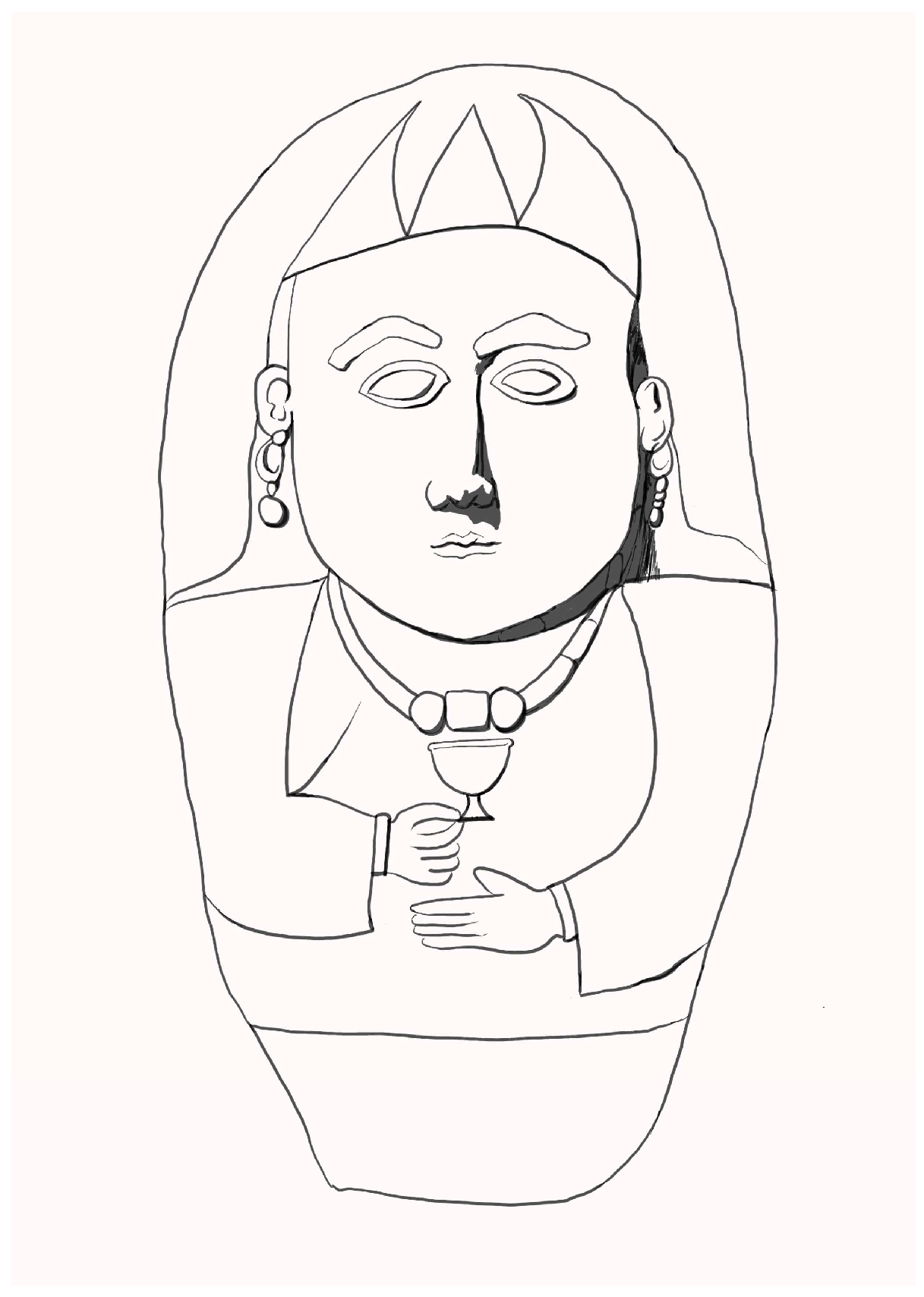

Among nearly two hundred grave goods, a gold necklace (Figure 1) stands out for its distinctly foreign form, materials, and imagery. Previous studies have concentrated on the necklace’s stylistic origins, proposing Persian, Byzantine, or Indian connections (Zhongguo Shehui Kexueyuan Kaogu Yanjiusuo 1980, pp. 16–17; Kiss 1984; Xiong and Laing 1991; Watt 2004, pp. 294–95). While these discussions establish its non-Chinese character, they largely treat the necklace as an isolated luxury object. This article instead examines how such a foreign ornament functioned within the funerary context of early medieval China.

Figure 1.

Gold necklace of Li Jingxun and line drawing, 6th–7th century CE, Xi’an, China. Photograph by the author; line drawing reproduced from the officially published archaeological report (Zhongguo Shehui Kexueyuan Kaogu Yanjiusuo 1980, p. 17).

This study argues that Li Jingxun’s necklace was an apotropaic object originally worn in life for protection, and later placed in the tomb to extend its protective and guiding role after death. Its design—combining a stag intaglio, large gold beads, pearl rondelles, and a central red stone—draws on symbolic traditions circulating across Eurasia, particularly within steppe and Iranian–Sogdian worlds. These meanings were not Buddhist in origin, yet the necklace was repositioned within a Buddhist burial environment concerned with rebirth and safe passage.

By situating the necklace within its archaeological, social, and ritual context, this article shows how a non-Buddhist amuletic object could be incorporated into a Buddhist mortuary framework, revealing the pragmatic and emotionally driven ways elite families in Sui-dynasty China combined different cultural traditions when confronting death.

2. Li Jingxun’s Aristocratic Lineage and Transcultural Context

Li Jingxun’s mother, Yuwen Eying 宇文娥英, was born into the highest echelon of Northern Zhou 北周 aristocracy as the daughter of Emperor Xuan 周宣帝 (r. 578–579) and Empress Yang Lihua 杨丽华. The Northern Zhou was a multiethnic empire dominated by Xianbei elites, whereas Yang Lihua herself came from a powerful Han aristocratic lineage—together reflecting the deeply hybrid political landscape of early medieval China. In 581, Yang Lihua’s father, Yang Jian 杨坚—who later became Emperor Wen 隋文帝 (r. 581–604)—overthrew the Northern Zhou, and she was accordingly reduced to the title of Princess of Leping 乐平公主.

Deeply resentful of her father’s usurpation and loyal to her deceased husband’s lineage, Yang Lihua steadfastly refused the emperor’s repeated attempts to compel her remarriage. Her widowed chastity, praised as exemplifying “loyalty” to her husband’s family, also left Emperor Wen with a deep sense of guilt toward her. Consequently, both she and her daughter Yuwen Eying received exceptional favor at the Sui court. Drawing on her political legacy as a former empress, the moral authority of her chaste reputation, and compensatory imperial patronage, Yang Lihua retained considerable influence within the Sui palace (Linghu 1971, p. 146; Wei 1973, p. 1124).

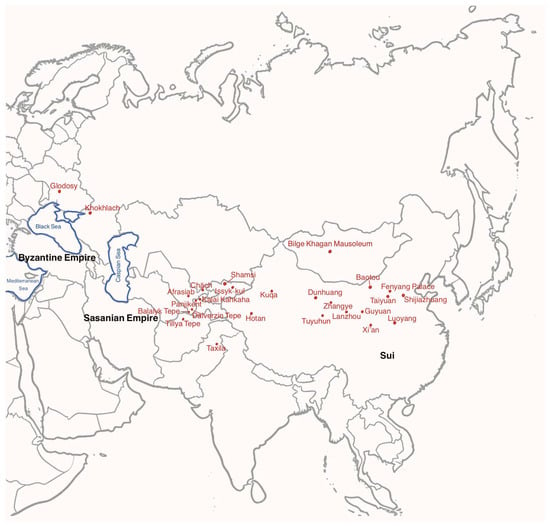

Li Jingxun’s paternal family, originally part of the Xianbei 鲜卑—an Inner Asian steppe people—migrated into northern China and adopted the Han surname Li. They settled in Yuanzhou 原州 (modern Guyuan), an important Silk Roads and military corridor (Figure 2). In the sixth century, her great-grandfather Li Xian 李贤, together with his brothers Li Mu 李穆 and Li Yuan 李远, rose to prominence through military achievements; all served as governors of Yuanzhou and joined the core of the ruling military aristocracy. Li Jingxun’s grandfather Li Chong 李崇 died in battle against the Göktürks, and her father Li Min 李敏 was subsequently raised in the palace.

Figure 2.

Map indicating sites and regions discussed in this article. Created by the author.

Admired for his noble lineage, graceful demeanor, and skill in riding, archery, song, and dance, Li Min was chosen by Yang Lihua as the husband of Yuwen Eying. They married with the full honors of a ceremony befitting a princess, and their family entered the highest echelon of Sui nobility, permitted to “reside permanently in the capital, attend palace entertainments, and receive rewards surpassing those granted to meritorious officials” (Linghu 1971, pp. 413–22, 527–30; Wei 1973, pp. 1115–24; Luo 1985; Li and Yu 2020).

Born in 600 CE, Li Jingxun was raised in the palace by her grandmother Yang Lihua, under whose influence she also embraced Buddhism. For Yang, who had endured dynastic upheaval, the loss of her husband, and the death of another daughter, the clever and gentle Jingxun became a profound source of emotional comfort and spiritual solace. Growing up in such privilege, she possessed both the right and the opportunity to acquire the empire’s most exquisite adornments.

In 608, Emperor Yang 隋炀帝 (r. 604–618 CE) launched a northern tour to meet the Turkic khan, and Yang Lihua brought Li Jingxun along. What began as an honorific journey ended in tragedy—the young girl fell ill and died in a temporary palace. Even the emperor mourned deeply: He suspended music, curtailed meals, repeatedly issued decrees for her ceremonial return to the capital, and provided generous burial gifts (Zhongguo Shehui Kexueyuan Kaogu Yanjiusuo 1980, p. 25). His actions both expressed his sympathy for his sister Yang Lihua and recognized the Li family’s distinguished service.

Li Jingxun’s remains were solemnly escorted back to Chang’an and interred six months later within Wanshan Monastery, a Buddhist nunnery near the imperial palace. She was dressed in fine silk garments and adorned with a floral gold headdress, a gold necklace, gold bracelets, jade ornaments, and other jewelry. Her body was placed in a stone coffin carved to resemble a miniature palace hall. Grave goods were arranged around her, including vessels for food, cosmetics, and daily use—many made of precious materials such as gold, silver, white jade, white porcelain, and glass. The coffin was encased by stone slabs and set within the tomb pit, with ceramic human and animal figurines arranged around the coffin in the space between it and the slabs. The underside of the epitaph stone and the surrounding area were covered with a continuous layer of charred black paper ash, suggesting that paper offerings—possibly including travel permits for the afterlife and spirit money—were burned during the burial ritual. After the tomb pit was filled, a Buddhist pagoda was erected above the grave, underscoring the burial’s distinctive religious context and its association with monastic space.

These intertwined elements of elite privilege, Xianbei and Han heritage, and Buddhist devotion shaped both the exceptional nature of Li Jingxun’s burial and the meanings embedded in its objects. Together, they provide the essential context for understanding the gold necklace’s transcultural design and symbolic authority.

3. Craft, Form, and Materials: Situating the Necklace Between the Steppe and the Iranian World

Despite the vast number of ancient tombs excavated in China, very few gold ornaments survive intact, as such items were primary targets of historical looting. Among the extant pieces, none resembles Li Jingxun’s necklace in structure or design. To date, it remains a unique example within the Chinese archaeological record, while many of its features find closer analogues in jewelry from the Western Regions. The following analysis examines each component of the necklace to demonstrate its entanglement with steppe and Iranian–Sogdian traditions and to clarify how it signified both elite status and sacralized identity.

3.1. Segmented Structure: A Shared Elite Form from the Steppe to Sogdiana

Li Jingxun’s necklace adopts a segmented construction consisting of three interconnected components: the chain, the central pectoral element, and the clasp. Segmented necklaces of this type appear to have originated in Hellenistic traditions around the Mediterranean and Black Sea (Treister 2004), and seem to have continued in use there into the early Middle Ages. A 6th–7th century CE gold necklace (Figure 3a) from Glodosy, Kirovograd, Ukraine, for example, may be understood as part of this tradition and is generally regarded as having been crafted for Pontic steppe elites (National Museum of History of Ukraine and Museum of Historical Treasures of Ukraine 2025).

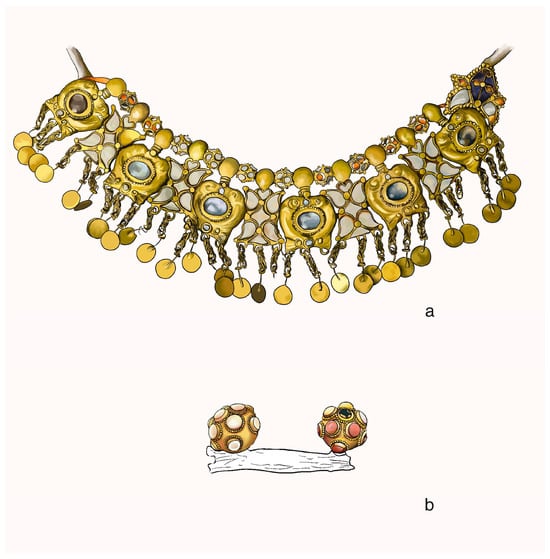

Figure 3.

Segmented necklaces from the 6th–8th centuries CE. (a) Schematic drawing of a gold necklace excavated at Glodosy, Ukraine; (b) Schematic drawing of a necklace worn by a Turkic ruler on coins issued in Chāch; (c) Necklace worn by a Central Asian noble figure in the Afrasiab murals, Uzbekistan; (d) Necklace worn by a Bodhisattva in the Ah-Ai Grottoes murals, Kuqa, China; (e) Necklace worn by a Bodhisattva in the Kumutula Grottoes murals, Kuqa, China. All images created by the author.

From the 6th to 8th centuries CE, segmented necklaces also appear to have been widespread across Central Asia and into China. In the 7th century CE “Hall of Ambassadors” at Afrasiab in Samarkand, Uzbekistan, several Sogdian and Turkic figures are shown wearing segmented gold necklaces whose central element typically consists of one square and two round bases set with blue stones and fitted with teardrop pendants—an ornament that scholars often interpret as a marker of noble status (Yatsenko 2004). Similar forms occur on contemporaneous Turkic balbal statues and on coins bearing portraits of Turkic rulers issued in Chāch, the region corresponding to modern Tashkent in Uzbekistan (Shagalov and Kuznetsov 2006, pp. 48–49). In 8th century CE murals from the Ah-Ai Grottoes in Kuqa, China, the Bodhisattva Mañjuśrī wears what appears to be a comparable Central Asian type (Zhou 2009, p. 237).

Additionally, 6th–8th century CE woodblock prints from the Hotan region of Xinjiang depict a deity adorned with a segmented necklace featuring three large circular bases and hanging pendants (British Museum, collection no. 1907,1111.71). Comparable necklaces recur in the murals of the Kumutula Grottoes in Kuqa, where the bases are often painted reddish-brown or blackish-brown, possibly to suggest garnet or other dark red stones (Figure 3e).

A notable feature of Li Jingxun’s necklace is the curved-square base at the center of the pectoral element. Its concave, arched edges align with the adjoining circular bases in a way that creates what seems to be a harmonious and integrated composition. Curved-square bases are also attested on the Glodosy necklace and on the Turkic ruler’s necklace (Figure 3b), while two curved-square bronze ornaments excavated at Panjikent in Tajikistan may represent further parallels. The conceptual pairing of square and circular forms might ultimately relate to earlier design principles, such as the X-shaped pendant of a gold necklace from Tillya Tepe in Afghanistan, as well as the “four-petal” pendant on a gold necklace from Taxila, Pakistan (Figure 4a).

Figure 4.

Jewelry employing polyhedral gold beads. (a) Schematic drawing of a gold necklace from Taxila, Pakistan; (b) Schematic drawing of a fragmentary ornament from the Shamsi, Kyrgyzstan. All images created by the author.

These convergences emerged within the broader historical context of the Turkic Khaganate’s rapid rise in the mid-6th century CE. Under Turkic hegemony, Sogdian merchants established an expansive commercial network that persisted into the 8th century CE and likely facilitated the movement of objects, techniques, and stylistic ideas across Eurasia (La Vaissière 2012, pp. 127–69). Within this interconnected milieu, the segmented necklace appears to have functioned as a widely recognized emblem of status and sacralized authority among elites from the Black Sea to Central Asia.

3.2. Large Gold Beads: Persian–Sogdian Techniques and Prestige Aesthetics

The necklace comprises twenty-eight gold beads, each constructed from twelve soldered rings with a central raised setting that holds a pearl. Polyhedral bead technology originated in the Western Mediterranean and gained wide circulation under the Roman Empire, with early examples attested in South Asia, Southeast Asia, and southern China. A 1st-century necklace (National Museum, New Delhi, Acc. no. 49.262/7) from Taxila, Pakistan, illustrates this fully developed technique (Figure 4a).

Concurrently, ancient Iranian workshops produced a wide repertoire of gold beads, including dodecahedral forms. Examples preserved in the Patty Burch collection and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, though dating to the Islamic period, likely perpetuate a considerably earlier craft tradition. The Greater Iranian cultural sphere also favored “pseudo-polyhedral” beads—spherical forms embellished with soldered rings or tubes to simulate facets—a practice well represented among the Burch holdings. Comparable pseudo-polyhedral beads (Figure 4b) appear in Central Asian contexts, notably on a fourth–fifth century ornament from Shamsi, Kyrgyzstan (Japarov et al. 2002, Part I, Illustrations).

Li Jingxun’s gold beads share their dodecahedral structure with the Taxila specimens, while their raised tubular settings, encircled by granulation, closely parallel the Kyrgyzstan examples. Taken together, these features imply a synthesis of South Asian and West Asian bead-making traditions mediated through Central Asia.

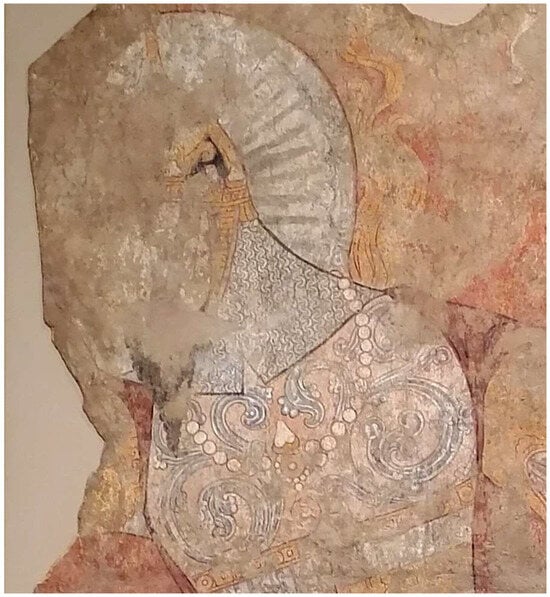

Large-bead necklaces appear to have been widely used across the ancient Iranian cultural sphere and can be traced back to the early first millennium CE, as suggested by several gold-bead necklaces from Tillya Tepe in Afghanistan. Their continued popularity into the Islamic period is indicated by examples in the Patty Burch collection and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. In Sasanian and Sogdian visual culture, both deities and aristocrats are often shown wearing such necklaces, with segmented forms particularly well attested in Sogdian wall painting.

In the Afrasiab “Hall of Ambassadors,” the west wall provides one of the most detailed depictions. One emissary holds in his right hand a segmented necklace composed of large white beads, a pectoral element consisting of one square flanked by two circles, and a teardrop-shaped blue pendant (Figure 5). In his left hand, he carries a pair of smaller ring-shaped objects with blue stones, which may represent gold bracelets. His attire suggests affiliation with a Persian–Sogdian cultural milieu. If so, bead necklaces, gold bracelets, and pearl-rondelle textiles (carried by another emissary) might have formed part of a recognizable repertoire of diplomatic gifts within this broader Iranian world.

Figure 5.

Ambassador holding a necklace, bracelets, and patterned textile in the Afrāsiāb murals, with an accompanying schematic drawing of the necklace. Mural photograph from Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain. Available online: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/5/5e/Ambassadors_from_Chaganian_%28central_figure%2C_inscription_of_the_neck%29%2C_and_Chach_%28modern_Tashkent%29_to_king_Varkhuman_of_Samarkand._648-651_CE%2C_Afrasiyab_Museum%2C_Samarkand%2C_Uzbekistan.jpg (accessed on 7 October 2025); schematic drawing of the necklace created by the author.

Similar segmented bead necklaces appear on the noblewomen depicted on the south and north walls of the same hall, and closely related forms are found in the wall paintings of the goddess Nana at Kalai Kahkaha I in Shahristan, Tajikistan, as well as in the “paradise” wall-painting scenes at Panjikent (Marshak and Raspopova 1991, fig. 6). Taken together, these examples suggest that such necklaces were favored by both divine and aristocratic women in Central Asia.

The beads in these representations are commonly painted white, which may allude to pearls or rock crystal. Given the strong Persian appreciation for bead necklaces and the high cultural value attached to pearls and crystal in Persian courtly traditions, it is plausible that this necklace type reflects a Persian ornamental heritage, even as it circulated across the wider Iranian cultural sphere.

3.3. Pearl Rondelle: Orderly Aesthetics and Steppe Technical Traditions

The focal point of Li Jingxun’s necklace is a vibrant red stone encircled by a lianzhu quan 联珠圈 (pearl rondelle), a feature that many Chinese scholars view as characteristic of Sasanian–Sogdian artistic production. Textiles decorated with pearl rondelles, which became widespread in China during the sixth to seventh centuries, are often referred to as hujin 胡锦 (Zhao and Qi 2011)—a term commonly used in Chinese scholarship to describe silk fabrics produced in, or stylistically influenced by, Persian or related Central Asian textile traditions (Figure 5, where the central envoy appears to hold hujin). In Sasanian–Sogdian art, elites and deities are frequently depicted wearing necklaces with a central pearl rondelle—for instance, the intricate piece worn by a deity at Panjikent (Figure 6). Related textile motifs may likewise represent stylized renderings of such necklaces.

Figure 6.

Large-bead necklace with a central pearl rondelle worn by a deity, mural from Panjikent, Tajikistan, 8th century. Source: Wikimedia Commons; photo by Netelo; CC BY-SA 4.0. Available online: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/2/2c/Hermitage_hall_341_-_03.jpg (accessed on 7 October 2025).

Although some earlier scholarship has proposed Byzantine parallels for these forms (Kiss 1984), the technical execution of the pearl rondelle in Li Jingxun’s necklace appears to differ from typical Byzantine craftsmanship. Rather than employing gold-wire stringing or claw settings—both of which are common in Byzantine jewelry and often used to intersperse pearls with other beads to create a more fluid composition, as seen on a pair of Byzantine bracelets in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (Figure 7)—each pearl in Li Jingxun’s necklace is tightly set within an individually crafted gold collet. This highly geometric and regular collet-setting technique may be associated with steppe goldsmithing practices. Comparable techniques appear in a range of finds, from first century gold discs near the Sea of Azov (Treister 2021, fig. 10), to fourth century “hedgehog” amulets from Dalverzin Tepe, Uzbekistan (Francfort 2022, no. 18, p. 43), and early medieval jewelry from the Black Sea region (Kasparova et al. 1989, cat. 89–92). As steppe groups moved south, such methods seem to have influenced jewelry production in the Northern Dynasties and became increasingly common during the Sui–Tang period (Ya Li 2020, pp. 516–21). Thus, the rondelle featuring pearls set in collets may exemplify a fusion of Persianate iconographic aesthetics and steppe technical craftsmanship.

Figure 7.

Jeweled bracelet (one of a pair), 500–700, Byzantine. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Public Domain. Available online: https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/464077 (accessed on 7 October 2025).

3.4. Intaglio Deer Nicolo: Steppe Animal Symbolism on a Sasanian Medium

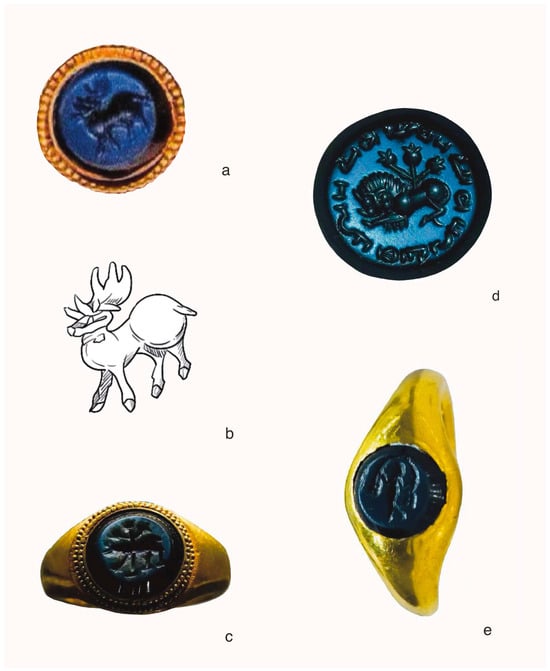

The clasp of Li Jingxun’s necklace is set with an intaglio gemstone carved with a deer motif (Figure 8a). The stone is cut into a truncated cone, with a deep-blue upper layer and a darker base, suggesting that it may be nicolo—a layered stone commonly used for intaglio carving because the contrast between layers enhances engraved imagery.

Figure 8.

Intaglio nicolos excavated in China. (a,b) Intaglio nicolo with a deer motif on Li Jingxun’s necklace; (c) Gold ring from the tomb of Li Xizong in Shijiazhuang; (d) Seal excavated from the joint tomb of Shi Hedan and his wife in Guyuan; (e) Gold ring excavated from the joint tomb of Li Xian and his wife in Guyuan. (a,b) Photograph and line drawing by the author; (c–e) photographs by the Weibo user Song Song Fa Wenwu Ziliao Jun 松松發文物资料君, used with permission. The image provider explicitly states that all images are open for reuse with attribution. Source: Weibo https://weibo.com/u/2041266127 (accessed on 10 December 2025).

Nicolo intaglios became widely popular in the Roman Empire, and a Roman-period example carved with Eros is mounted on the pendant of the gold necklace from Glodosy. By the time of Li Jingxun, however, deer motifs carved in nicolo appear to have been most closely associated with Sasanian seal production. The deer on her clasp is highly schematized (Figure 8b): its crescent-shaped antlers, tubular body, and rounded haunches closely recall Sasanian glyptic conventions (compare, for example, a seal in the Museum für Islamische Kunst, Berlin, Acc. no. VA 1198). Similar stylized deer also appear on contemporary hujin textiles from the Silk Roads (Zhao and Qi 2011, p. 126).

The choice of a deer motif, rather than other animal or figural imagery, may itself be significant. Deer play only a limited role in Sasanian religion and art, but on the Eurasian steppe—from the Scythian–Siberian world to the early Turks—they served as potent spiritual beings associated with protection, guidance, and fertility, and were among the most recurrent animals in steppe art (Aruz et al. 2006). A 4th–5th century agate intaglio with a deer motif, although stylistically Sasanian, belonged to an Alan prince. The Alans, originally a Central Asian nomadic group, later migrated westward to the northern Caucasus adjacent to Sasanian domains. The seal’s deer imagery appears to combine Sasanian craftsmanship with steppe artistic conventions and symbolism, and it may have been produced by an artisan influenced by Sasanian techniques for a nomadic elite patron (Lerner 2005). The seventh century pilgrim Xuanzang 玄奘 recorded sacred deer herds under the protection of the Turkic Khagan (Xuanzang and Bianji 2000, p. 76), while the eighth century Bilge Khagan was buried with two gilded silver deer featuring leaf-shaped wings denoting sanctity. Their presence on Turkic stelae further highlights their ritual importance. Chinese historical texts further suggest that some Turkic groups regarded the deer as a female ancestor or mother-spirit (Lin 2005).

Perhaps under the influence of Turkic and other steppe traditions, deer became increasingly common in Sogdian art of the sixth to eighth centuries (Kageyama 2006). Unlike in Sasanian royal iconography—where deer are more often presented as quarry—Sogdian depictions tend to render the animal in a dignified, serene manner. The gilt-silver deer from Bilgä Qaghan’s tomb might likewise be understood within a Turkic–Sogdian artistic milieu, especially given the well-documented presence of highly skilled Sogdian goldsmiths in the Turkic Khaganate (Chen 2013, pp. 132–35).

3.5. Stones and Color: Central Asian Preferences over Mediterranean Polychromy

The deep-blue square gemstone set at the end of Li Jingxun’s necklace is likely lapis lazuli or an imitation. Although lapis had been highly prized for millennia across Egypt, Mesopotamia, Iran, and Central Asia, its relative prominence appears to have declined after the fourth century BCE, when Alexander’s eastern campaigns facilitated the wider circulation of newly valued gemstones from South Asia (Thoresen 2017). From the Hellenistic period onward—and especially by the sixth and seventh centuries—sapphires, rubies, diamonds, amethysts, aquamarines, and garnets became increasingly favored in both Byzantine and Indian jewelry traditions. Lapis lazuli, while still traded along the Silk Roads and present in the Mediterranean, seems to have played a more modest role in elite ornamentation compared with these high-transparency gemstones.

Viewed as a whole, the necklace employs gemstones of relatively low transparency and modest monetary value, dominated by blue hues. Notably, all the stones are cut into regular shapes and are harmoniously matched in color and size. These features align closely with jewelry excavated in Central Asia and with the ornamentation depicted in Central Asian murals, where lapidary practices emphasize geometric clarity and chromatic coherence (Figure 3c,d). This aesthetic stands in marked contrast to the “polychrome style” prevalent in the Mediterranean and Black Sea regions, where a single piece of jewelry often combines stones of various origins, colors, and shapes to create a display-like, treasure-laden visual effect (Figure 3a and Figure 7).

Although the available comparanda differ from Li Jingxun’s necklace in both date and precise form, they remain the closest parallels currently known, particularly in light of the absence of comparable material within China. Taken together, these examples suggest that the necklace is more plausibly situated within the artistic traditions of the Iranian–steppe interface than within Byzantine or Indian contexts. Given the geopolitical dynamics of the 6th–8th centuries and Central Asia’s pivotal role in mediating exchanges between East and West, the cultural environments of Sogdiana and Bactria—where Iranian and nomadic traditions intersected—emerge as especially relevant. Several technical features further support this interpretation: a beaded ring formed by soldering a circle of gold granules to the clasp—likely intended to prevent accidental opening—may recall the fastening devices on the Eros-shaped earrings from Tillya Tepe, while the use of gem- or pearl-set collets to conceal structural junctions finds close parallels in 6th–7th century ornaments from Panjikent (Raspopova 1987, fig. 74, no. 1).

4. The Possible Context of Production and Circulation of Li Jingxun’s Gold Necklace

Beyond the formal and stylistic comparisons discussed above, the cultural character of Li Jingxun’s necklace must also be understood within a more specific social and historical context. This section approaches the issue from three interrelated perspectives. First, Li Jingxun’s family was long active in Yuanzhou, a key node on the eastern segment of the Silk Roads, where close ties between the family and local Sogdian communities can be demonstrated through both textual and archaeological evidence. Second, the operation of Sogdian–Turkic networks across Eurasia between the sixth and eighth centuries provides a broader framework for the production and circulation of gold ornaments of this type. Third, Emperor Yang of Sui’s systematic engagement with the Western Regions in the early seventh century further strengthened the practical functioning of these networks within China. Through these three perspectives, this section explores the possible context of production and circulation of Li Jingxun’s necklace.

4.1. Li Jingxun’s Family and Local Sogdian Networks

Li Jingxun’s ancestral home, Yuanzhou, was an important node on the eastern Silk Roads and a region where non-Chinese groups—especially Sogdians—were active and often settled. Recent archaeological discoveries in the area, including the Sui–Tang period cemeteries of the Shi Shewu 史射勿 and Shi Suoyan 史索岩 families and the Sui-dynasty tomb at Jiulongshan 九龙山, display clear Central Asian cultural elements, confirming the presence of local Sogdian communities (Luo 1996; Chen et al. 2012). The Li family’s ability to maintain firm control over Yuanzhou and to rise from local military power into the imperial aristocracy may have been connected to long-term interaction with these Sogdian groups who also settled in China.

Historical sources record that when Li Xian and his brothers seized Yuanzhou, they received support from Shi Ning 史宁, enabling them to defeat Shi Gui 史归, who had previously held the region. Both Shi Ning and Shi Gui were Sogdians settled in China, and the surname Shi is often regarded as a medieval Chinese transcription of a Sogdian ethnonym (Rong 2001). The epitaph of Shi Shewu further records his repeated participation in military campaigns alongside the Li family and his accumulation of merit, indicating a relatively stable cooperative relationship between the Li family of Yuanzhou and Sogdian military forces.

The Sogdian families of Yuanzhou functioned as cross-cultural intermediaries with skills spanning military service, translation, horse breeding, and commerce. Through military achievements they acquired local official positions, while their linguistic abilities and commercial networks enabled long-distance exchange, forming a significant presence in the region (J. Li 2008; Wertmann et al. 2017). This role is also reflected in material culture. Li Jingxun’s great-grandfather Li Xian and his wife died in Chang’an in 569 and were later reburied in Guyuan. Although their tomb was heavily looted, it still yielded glass bowls, a gilt silver ewer, and gold rings (Z. Han 1985). These objects display clear Persian and Central Asian stylistic features, indicating a relatively high level of acceptance among Yuanzhou elites of Western luxury goods and the aesthetic values associated with them.

At a deeper level, the appearance of such objects in Li Xian’s tomb may also point to exchanges of religious and symbolic systems. An intaglio nicolo seal excavated from the tomb of Shi Hedan 史诃耽 (d. 670), son of Shi Shewu, is cut in a truncated conical form with a deep blue upper layer and an almost black lower layer (Figure 8d). Its imagery and Middle Persian inscription have been identified by scholars as bearing typical Zoroastrian symbolism: the lion represents the sun or royal power, the three plants may be understood as a Tree of Life or pomegranates associated with fertility, and the inscription is often interpreted as an auspicious formula (Guo 2015). Taken together, the seal and the Iranian-derived names of both Shi Shewu and his son Shi Hedan provide strong evidence that elements of Iranian religious and symbolic traditions continued to be maintained within the family after their settlement in China.

At the same time, Li Xian’s wife wore a gold ring set with a nicolo gemstone carved with a nude female figure holding floating ribbons (Figure 8e). Similar figures appear on Sasanian metalwork and may relate to Iranian symbolic systems associated with fertility, abundance, and female divinities (Sangari et al. 2024). Given that traditional Chinese art generally avoided the public depiction of nudity, the choice of such an image may indicate that Li Xian’s wife and her family understood and, to some extent, accepted the protective or auspicious meanings embedded in its symbolism.

It may therefore be cautiously suggested that for local elites such as the Li family, these objects were not merely foreign luxuries but also served as mediating tools in their cooperation with Sogdian groups. Through gifting, wearing, shared appreciation of luxury goods, or even joint participation in certain religious or ritual activities, the Li family and the Sogdians could express mutual recognition and reinforce their alliance.

Li Jingxun herself grew up in the palace under the care of her grandmother, Yang Lihua. During her activities at the early Sui court, Yang Lihua may also have had relatively close contact with Sogdian circles. In 594, after the early death of her daughter Yuwen Xuan 宇文昡, Yang Lihua commissioned the Sogdian-descended scholar He Tuo 何妥 to compose the epitaph (Feng et al. 2024). Unlike conventional epitaphs that focus primarily on the life of the deceased, this inscription devotes substantial space to praising Yang Lihua’s identity, virtues, and conduct as empress of Northern Zhou, suggesting the author’s familiarity with and recognition of her.

While He Tuo participated in Sui court culture and ritual practice as a Sogdian-descended literatus, his family continued to preserve craft traditions in which Sogdians were particularly skilled. Historical sources record that He Tuo’s elder brother He Tong 何通 was renowned for jade carving, while his nephew He Chou 何稠 served at the Sui court, overseeing the design and manufacture of ritual vessels, luxury goods, and major architectural projects—responsibilities that overlapped in part with the official duties of Li Jingxun’s father. He Chou is especially known for reviving glassmaking techniques that had previously been lost in China, successfully producing green glass, and for imitating Western luxury items, including Persian gold-brocaded textiles (Wei 1973, p. 1596). The green glass bottle excavated from Li Jingxun’s tomb has now been widely identified, on the basis of form and technique, as a product of local manufacture. In light of He Chou’s revival of glass production, this vessel may be understood as one example of glassware produced and used within the Sui court’s craft system.

4.2. Sogdian–Turkic Networks and the Circulation of Luxury Goods

Central Asia long occupied a position at the intersection of multiple civilizations and political powers along the Silk Roads, and long-distance commerce formed one of the key economic foundations of local societies. By the late sixth and early seventh centuries, Sogdians were particularly well known for their active role in east–west exchange across Eurasia. Chinese sources describing the Sogdian states frequently emphasize their emphasis on commerce and long-distance travel. The Tang Huiyao 唐会要 (Essential Regulations of the Tang Dynasty), for example, notes Sogdian customs: “When a boy reaches twenty, he is sent to foreign lands and comes as far as the Central Plain. Wherever profit lies, they will go” (Wang 1960, p. 1774). Although such passages carry clear moral judgments, they nevertheless reflect Chinese perceptions of the high mobility of Central Asian mercantile societies. Xuanzang offers similar observations on local customs, which may be read as a traveler’s account of how these commercial societies operated (Xuanzang and Bianji 2000, p. 72).

The expansion of Sogdian trade was closely linked to shifts in the political landscape of Central Asia. In the 5th century, the Hephthalites took control of Transoxiana and emerged as a power capable of rivaling the Sasanian Empire; under their rule, Sogdian commercial activity along the Silk Roads intensified. In the mid-6th century, the rise of the Turkic Khaganate further transformed the region. At its greatest extent, Turkic power stretched roughly from the Sea of Azov to the Great Wall, and from the Siberian forest-steppe to Afghanistan. The Turks relied heavily on Sogdians to help administer and mediate this vast territory. Beginning with the embassy sent to Byzantium in 568 on behalf of the Turkic khagan, Sogdians acted as advisers and commercial agents in Turkic participation in long-distance trade, helping to establish an extensive network linking the Mediterranean with East Asia—a system that remained active into the 8th century.

Within this network, Central Asians were not only involved in intermediary trade but also directly participated in the production and imitation of goods, especially high-value items circulating along the Silk Roads. The imitations of Byzantine coins from the tombs of the Shi family, as well as the gilt silver ewer from Li Xian’s tomb—made in a Sasanian vessel form but decorated with Greek mythological imagery—may have been produced in Central Asia before reaching China (Luo 2000). Central Asians who entered China, such as the Sui court artisan He Chou, further introduced these practices of imitating high-value goods into the Chinese context.

As commerce and craft production expanded, a symbiotic relationship between Sogdians and nomadic groups became a characteristic feature of these exchange networks. The so-called “barbarian” assemblage from Malaya Pereshchepina in Ukraine, for example, combines Byzantine, Sasanian, and local elements, while objects such as sword scabbards, stemmed cups, vessels, and saddles display stylistic features often associated with Turkic–Sogdian artistic traditions (Kasparova et al. 2000, pp. 39–42). In this sense, Turkic military expansion and Sogdian commercial activity together facilitated long-distance and sustained cultural interaction, leading to material and visual transformations along the Silk Roads—processes that may, to some extent, be understood as a form of ancient globalization.

Such cross-regional circulation is also evident in the distribution of specific object types within China. The Sasanian-style intaglio nicolo gemstone on the clasp of Li Jingxun’s necklace is not an isolated case. Comparable stones have been found in the tomb of Lü Da 吕达 in Luoyang (d. 524), the tomb of Li Xizong 李希宗 in Shijiazhuang (d. 540) (Figure 8c), and the tomb of Xu Xianxiu 徐显秀 in Taiyuan (d. 571) (Cheng 2011; Li et al. 1977; Chang et al. 2003). Although these tombs are widely dispersed geographically, they cluster chronologically in the sixth century. Scholarship generally regards Sogdians as key intermediaries in the transmission of such seals and their associated decorative traditions into China (Iwamoto 2006; X. Han 2022).

Li Jingxun’s necklace itself also reflects the convergence of multiple material traditions. The gemstone used for the pendant may originally have been colorless rock crystal, given a pale blue appearance by applying blue pigment to its base. A similar technique appears on a teardrop-shaped pendant excavated from the tomb of the Sogdian Shi Suoyan (d. 656) in Guyuan, whose form closely resembles that of Li Jingxun’s pendant and was likely part of a piece of jewelry (Figure 9a). This treatment was probably intended to imitate the appearance of sapphire, and the teardrop shape itself is a common form for sapphires. In this way, Li Jingxun’s necklace combines segmented gold collars favored by Black Sea and Central Asian steppe elites, large-bead necklaces and intaglio gemstones popular among Sasanian elites, and the appreciation for transparent gemstones characteristic of Byzantine and Indian jewelry.

Figure 9.

Sogdian pendants. (a) Pendant excavated from the tomb of Shi Suoyan in Guyuan, image reproduced from the officially published archaeological report (Luo 1996, pl. 13); (b) pendant excavated from Balalyk Tepe, drawing by the author.

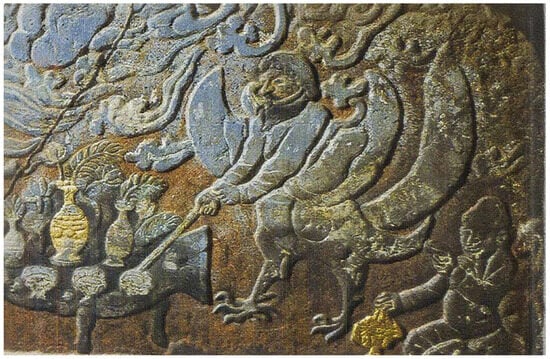

The gold stemmed cup excavated from Li Jingxun’s tomb can likewise be understood within this broader Eurasian context. The stemmed cup form originated in the West and appeared widely across Eurasia between the sixth and seventh centuries, often in connection with Turkic–Sogdian activity. In the Black Sea region, the gold stemmed cup from the Malaya Pereshchepina assemblage is generally regarded as locally made, yet its decoration incorporates Sogdian and Turkic–Sogdian artistic features (Tokyo National Museum 1985, cat. no. 145 caption). In Central Asia, murals at Balalyk Tepe in Uzbekistan depict Hephthalite elites holding stemmed cups by delicately pinching the base between thumb and forefinger—a gesture that may derive from Iranian and Central Asian elite etiquette and was later transmitted by Sogdians to the Turks, as reflected in Turkic stone statues (Hayashi 2003). In China, gold stemmed cups appear in banquet scenes carved on the stone funerary furnishings of An Jia 安伽 (d. 579), Shi Jun 史君 (d. 579), and Yu Hong 虞弘 (d. 592), officials serving as sabao 萨保—administrators of non-Chinese communities—in the latter half of the sixth century (Shaanxi Sheng Kaogu Yanjiusuo 2003, pl. 21, 64; Shanxi Sheng Kaogu Yanjiusuo 2005, fig. 159, pl. 37; Xi’an Shi Wenwu Baohu Kaogu Yanjiuyuan 2014, pl. 15, 27). On An Jia’s funerary couch, he is shown seated beneath a Chinese-style pavilion, holding a gold stemmed cup in this same elite manner and offering it to a Turkic guest, illustrating the continued circulation and reinterpretation of this vessel form and its associated gestures across different cultural settings.

4.3. Sui Engagement with the Western Regions and Elite Ornament

According to contemporary burial practice, grave goods can generally be divided into two categories: objects actually used by the deceased in life, such as clothing, ornaments, and food vessels; and mingqi 明器, items made specifically for funerary purposes, such as ceramic figurines. The gold necklace excavated from Li Jingxun’s tomb clearly belongs to the former category and was most likely worn during her lifetime. Gold jewelry was not a common type of mingqi; in elite Sui tombs, high-value ornaments were usually taken directly from personal possessions rather than specially produced for burial.

Although the necklace now preserved in the National Museum of China is damaged, photographs published in the archaeological report show that its overall structure was largely intact at the time of excavation, with only a few pearls having deteriorated due to long burial. There is no clear evidence of repeated repair or prolonged circulation, making it unlikely that the necklace was an heirloom passed down over generations. Li Jingxun died in 608 at the age of nine. Considering her young age and the necklace’s state of preservation, it is reasonable to suggest that the necklace was produced no earlier than the late sixth century and no later than the early seventh century.

This timeframe coincides with a period of particularly close relations between the Sui dynasty and the Turkic and Western Regions. The Sui dynasty (581–618) reunified China after centuries of political division. Following internal consolidation, the court directed substantial military and diplomatic resources toward the north and northwest. During Emperor Wen’s reign, the Sui gradually established superiority over the Eastern Turks in the late sixth century by exploiting internal divisions and conducting military campaigns. After ascending the throne, Emperor Yang twice conducted northern tours to the Turks, during which the Eastern Turkic khagan personally came to court, demonstrating Sui dominance at this stage.

At the same time, Emperor Yang showed sustained and explicit interest in Western Regions affairs. He stationed officials in key Hexi Corridor cities such as Zhangye and Dunhuang, actively encouraged foreign merchants, promoted long-distance trade, and secured the Hexi routes through military campaigns against the Tuyuhun. The Sui court also dispatched envoys to Persia, Sogdiana, and other regions, strengthening ties with Central Asia. These efforts culminated in 609, when Emperor Yang toured west to Zhangye and convened envoys from more than thirty Western Regions states, before returning to the eastern capital Luoyang for another grand assembly attended by representatives from across Central Asia (Wei 1973, pp. 68–71, 1578–81; Yanshou Li 1974, p. 3207). Notably, Li Jingxun and her grandmother Yang Lihua died while accompanying Emperor Yang on his northern and western tours, respectively.

Traditional historiography often interprets these activities as expressions of Emperor Yang’s extravagance and ambition. From a broader historical perspective, however, Sui engagement with the Western Regions can also be understood as an attempt to integrate China more fully into the Eurasian trade system driven by Turkic and Sogdian networks. Historical sources record that Sui envoys traveling to and from the Western Regions brought back exotic objects such as agate vessels, dancers, and lion skins, while multiple Central Asian polities sent tribute missions to the Sui court. This unprecedented intensity of exchange created favorable conditions for Western luxury goods and their associated aesthetic forms to enter the Chinese heartland. The appearance of Li Jingxun’s necklace may be understood as a product of this historical context.

The Hexi Corridor, which Emperor Yang worked actively to develop, was a key channel within this exchange system. Murals from the Dunhuang caves provide important visual evidence. In Sui-dynasty murals, representations of necklaces change noticeably: segmented gold necklaces begin to appear and later become common in the Tang period. A Bodhisattva figure in Mogao Cave 397 wears a segmented necklace composed of large beads, with a chest ornament arranged in a “one square and two circles” configuration that closely resembles necklace structures common in Central Asia (Figure 10). From the Afrasiab murals, through the Dunhuang caves, to excavated objects from tombs in the Chang’an region, one can trace the eastward transmission of segmented bead necklaces along the eastern Silk Roads.

Figure 10.

Bodhisattva wearing a large-bead necklace, Sui dynasty (581–618), Mogao Grotto 397, Dunhuang, China. Author’s schematic illustration, after Duan (Duan 1991, p. 184).

The beads depicted on Bodhisattva necklaces in these murals are relatively large, and in terms of material and visual effect, they are more likely to represent gold beads than pearls or gemstones. A large gold bead excavated from the tomb of Liu Yi and his wife (d. 592) in Lanzhou supports this interpretation (Xue 2023). The bead is soldered with twelve gold rings on its surface and perforated at both ends for stringing. Although the tomb was heavily looted, it is likely that more than one such bead was originally present. Notably, Liu Yi’s wife belonged to Li Jingxun’s family, and Lanzhou lies between Guyuan and Dunhuang, a region also known to have hosted Sogdian settlements. This geographical and familial context provides an important clue for understanding the circulation and use of similar gold bead ornaments in the Hexi Corridor.

In sum, this study argues that Li Jingxun’s necklace was closely connected to Central Asian Sogdian networks and that its appearance in China in the late sixth to early seventh century may be understood as a material outcome of the Sui dynasty’s attempt to engage with Turkic–Sogdian exchange systems. However, because the necklace remains a unique example within China and because Sogdians themselves were highly mobile, it is not yet possible to determine conclusively whether it was produced in the Western Regions, in the Hexi Corridor, or within the Sui court by Sogdian artisans.

5. Reading the Amulet: A Trans-Asian Symbolic System

Modern viewers often overlook the tiny stag on the clasp and the incisions on the pendant. These details are not meant for display: when worn, the deer sits at the nape of the neck, and the cuts interrupt the pendant’s smooth polish. This suggests that visibility was not the main priority. The necklace is carefully staged, with a bright red stone anchoring the center of the chest and engraved stones placed at the ends. Rather than a random mix of foreign motifs, the piece can be read as an object arranged to carry meaning. As a working hypothesis, it draws on steppe and Iranian–Sogdian ideas of protection, fertility, and seasonal renewal circulating along the Silk Roads. Taking this as a starting point, the following sections examine the stag intaglio, the gemstone scheme, and the pendant to explore how the necklace articulated guidance, cyclical time, and regeneration through comparison with Eurasian material and visual traditions.

5.1. Fertility and Life: Sacred Stag, Pearls, and Generative Numbers

The recurring deer motif in Eurasian steppe art is intrinsically linked to a “Great Goddess” complex—conceptually akin to the Mediterranean “Mistress of Animals”—associated with supreme power over life, death, and nature. The deer, tree (axis mundi), bird, and goddess formed a potent symbolic combination (Jacobson 1993, 2015). A Sarmatian gold diadem (Figure 11) from the Khokhlach Kurgan, Russia exemplifies this: it is centered on a figure of Artemis surmounted by a Tree of Life, flanked by deer, goats, and birds (Treister 2021, p. 382). Artemis, known as the Mistress of Animals and Mother of Mountains, was intrinsically linked to the deer as her sacred companion. She embodied supreme dominion over nature, bestowed and safeguarded life, nurtured animal young, and fostered human infants until marriageable age. She also awakened youthful sexuality and protected women during childbirth (Zolotnikova 2017). Her attributes resonated with the steppe Great Goddess concept, leading to iconographic borrowing and syncretism in the Hellenistic era.

Figure 11.

Gold diadem, 1st century, Khokhlach Barrow, Novocherkassk, Russia. Source: Wikimedia Commons; photo by Colonel Lobo; CC BY-SA 4.0. Available online: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/2/2d/%D0%94%D0%B8%D0%B0%D0%B4%D0%B5%D0%BC%D0%B02019.jpg (accessed on 7 October 2025).

Another pertinent example is the famous gold diadem from Tillya Tepe, featuring golden floral trees flanked by animals and birds (Qinghua Daxue Yishu Bowuguan 2022, pp. 118–20). Gold earrings from the same tomb confirm the Great Goddess’s presence: a Hellenistic-style semi-nude female figure flanked by animals, asserting her “Mistress of Animals” identity (Figure 12). The goddess and the blooming flower above her form an axis, with birds on either side. Such diadems became markers of steppe elite identity. Buyao (步摇, step-shake hair ornament) crowns in Han–Jin China likely resulted from the eastward movement of this steppe fashion (Sun 1991; Peterson 2022).

Figure 12.

Gold earring depicting goddess driving beasts, first century, Tillya Tepe, Afghanistan, photo by Author.

The deer motif and implicit vertical axis on Li Jingxun’s necklace likely invoke associations with the life-controlling Great Goddess. The necklace’s structure and materials reinforce this symbolic program. The number twenty-eight (gold beads) approximates the lunar synodic cycle. The symmetrical, circular structure of fourteen plus fourteen beads mirrors the waxing and waning phases. Lunar cyclical renewal symbolized regeneration. The average woman’s menstrual cycle is also approximately twenty-eight days, its onset marking sexual maturity and fertility potential.

Each gold bead holds ten pearls, totaling 280 pearls—closely matching the average human gestation period (280 days). This numerical correspondence strongly suggests intentional symbolism related to fertility and life generation. Pearls embody this metaphor across cultures: they are formed within an oyster around an intruding grain of sand—much like sperm entering the female body to conceive life. In Persian poetic tradition, pearls were imagined as raindrops (like seeds) entering the oyster’s heart, imbuing them with generative power. Fertility is the Great Goddess’s core domain, underscoring the deer gem’s associative power.

5.2. Celestial Bodies: Gems as Cosmic Emblems

Ancient deities, gems, and celestial bodies were frequently linked. Greek Artemis was associated with the moon; Persian Anāhitā was associated with Venus; Sogdian Nanā was identified by the crescent moons or depictions holding sun and moon; and Turkic Umay was also linked to sun or moon. The deep blue-black hue of the deer nicolo evokes the night sky, potentially symbolizing a celestial body linked to divine hunt or nocturnal passage.

The prominent red stone at the center of Li Jingxun’s necklace pectoral, together with the surrounding cluster of twenty-four pearls, may be understood as evoking the sun and its radiating light. The use of round red stones to represent the sun has a long history and recurs in jewelry traditions across the Mediterranean and West Asia. A Parthian-period necklace now in the British Museum (collection no. 19650215.1) offers a useful point of comparison: its pectoral centers on a large, round deep-red stone, encircled by gold granules arranged in a radiating geometric pattern that visually simulates the sun’s rays; symmetrical bird motifs flanking the pectoral further reinforce this solar-centered symbolic structure (Figure 13).

Figure 13.

Schematic drawing of a gold necklace from the Parthian period (ca. 3rd century BCE–3rd century CE), British Museum collection. Created by the author.

The number twenty-four holds significance: Sasanian kings wore necklaces of twenty-four pearls; hujin textiles show rondelles of twenty-four white dots (Akbarzadeh 2022, p. 42; Akbarzadeh 2023, p. 109). Crucially, in the Taq-e Bostan relief depicting Ardashir II’s investiture, the sun god Mithra radiates twenty-four rays. On a Sasanian seal (British Museum, Acc. no. OA 1932.5-17.1), Mithra radiates twenty-three rays, and the twenty-fourth ray could be behind the mountain (Callieri 1990). The sun, dispelling darkness, was essential for life. Mithra, as solar embodiment, was invoked for apotropaic blessings ensuring prosperity (Dustkhvāh 2005, pp. 164–210). If the red stone symbolizes the sun, the four settings flanking it may represent seasons, cardinal directions, or elements, mapping cosmic order onto the wearer.

5.3. Life-Giving Rain and the Cosmic Hunt: The Pendant

In Central Asian jewelry, specific pendant iconography often served amuletic functions. A fifth–sixth century teardrop pendant from Balalyk Tepe, featuring a green glass intaglio of a nude goddess nursing a child (Figure 9b) (Rempel 1987, p. 83), directly addresses fertility and protection.

These comparanda contextualize Li Jingxun’s pendant. Positioned at the axis bottom, the crystal material, pale blue color, and teardrop shape evoke rain. In arid West and Central Asia, the rain god Tištar (Tištrya) was highly venerated. The Avesta (Yasht 8) praises him for descending into the cosmic sea Vourukaṣa, battling the drought demon Apaoša, and releasing life-giving rains (Panaino 1982; Dustkhvāh 2005, pp. 144–63). Seeds from the “Tree of All Seeds” at the sea’s center descended with the rain, representing the origin of all plants. Tištar also bestowed healthy offspring and fat livestock upon devotees, functioning as a controller of water and a deity of fertility and abundance. Furthermore, his depiction alongside the Great Goddess Nanā on Sogdian ossuaries may suggest an association with resurrection themes.

The four concave incisions on Li Jingxun’s pendant are highly stylized. While its raised outline recalls a steppe tamga (a hereditary clan emblem in Turkic–Mongolic contexts), it may more compellingly represent a stylized dog—an interpretation strongly supported by the canine’s sacred status in Zoroastrianism. In this faith, widespread in ancient Western and Central Asia, dogs were revered as warders of evil and guardians of divine order, playing key roles in rituals such as the “Sagdid” (dog gaze) ceremony to protect the deceased during funerals.

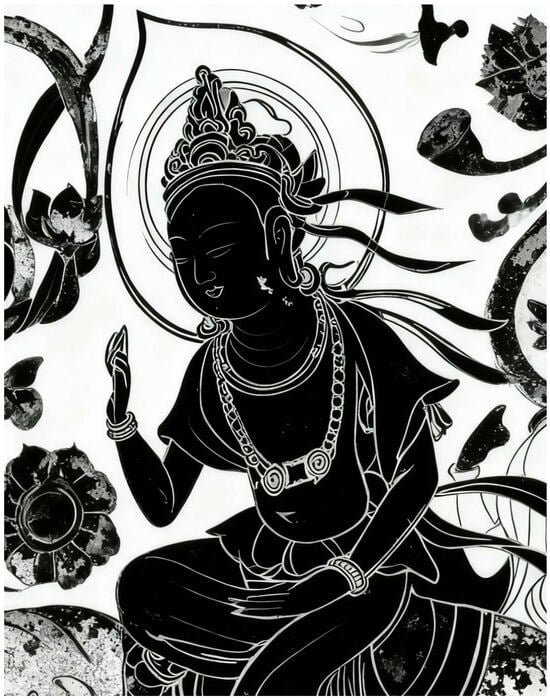

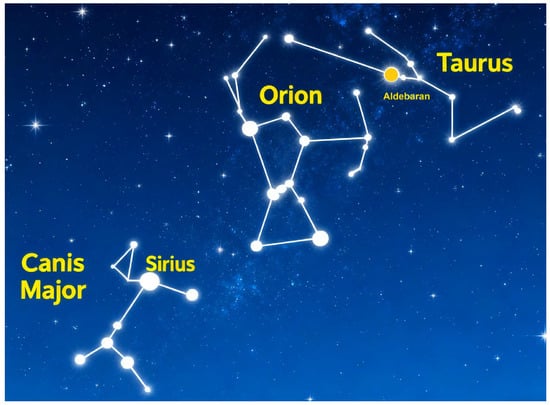

This profound cultural connection finds its celestial counterpart in the rain god Tištar, whose associated celestial body is Sirius—the “Dog Star” in the constellation Canis Major (Figure 14). This intrinsic link explains why dogs, along with bows, are emblematic of Tištar in Central Asian art (Compareti 2017, p. 3). The bow’s presence aligns with Avestan hymns that praise Tištar for streaking “across the sky like the finest arrow.” Ultimately, this potent imagery of the divine hunter may trace its origins back to the widespread “Cosmic Hunt” myth cycle.

Figure 14.

Schematic diagram of Sirius, Orion, and Aldebaran. Author’s diagram.

The core narratives of the widespread Eurasian “Cosmic Hunt” myth involve “a hunter pursuing a deer, both transformed into stars,” evolving into multiple regional variants (d’Huy 2013). In Siberian and Altai versions, a stag steals the sun in autumn; a hunter pursues the stag, recapturing the sun in spring, whereupon both become constellations (Lushnikova 2002, p. 255). This reflects observations of celestial movements, seasonal changes, and vegetative growth cycles, coupled with ritual intervention concepts—the hunting of the stag metaphorizes sacrificial rituals aimed at restoring cosmic order and facilitating seasonal transition. The stag serves as a ritual messenger bridging worlds and a symbol of prosperity.

In the Indian version, Prajāpati, the Lord of Creatures in the form of a stag, pursues his daughter Uṣas, the dawn goddess embodied as a red doe. Rudra shoots the stag with an arrow to prevent the incest (Forssman 1968, p. 58). The stag becomes Orion, the doe becomes Aldebaran (known in Indian tradition as Rohiṇī) in Taurus, Rudra becomes Sirius (known in Indian tradition as Mṛgavyādha, “Deer-Hunter”), and the arrow becomes Orion’s belt (Figure 14). While this version introduces ethical elements, core themes such as Rohiṇī (symbolizing fertility), the liberation of Uṣas (enabling the sun to rise unimpeded), and the constellation Taurus (which hosted the vernal equinox some four millennia ago) continue to serve as potent metaphors for seasonal transition and the renewal of all life.

In the Greek version, Orion is killed by Artemis’s arrows and becomes the constellation, with his dogs becoming Canis Major and Minor (Janda 2022). Scholars argue the original hunter figure represented a deity governing water and fecundity, with the core theme being abundance and renewal (Fontenrose 1981, pp. 259–60).

The Cosmic Hunt narrative enables an integrated interpretation of the Li Jingxun necklace: The onset of winter/darkness (symbolized by the blue-black stag gem) brings withering; the stag, as messenger or sacrifice, communicates with the divine; the deity releases the sun (red gem), enabling seasonal transition (four settings); simultaneously, rain (crystal pendant) and seeds descend; consequently, life is renewed (280 pearls). This process is cyclical (twenty-eight beads, ring structure), ensuring perpetual regeneration. This represents the perceived fundamental order of the cosmos and nature.

6. Using and Understanding Foreign Objects: Family Knowledge, Ritual Practice, and Burial Choice

This section turns from the necklace’s form and symbolic associations to its actual use and placement in Li Jingxun’s burial. It examines how the object was understood within the family, how it was worn and arranged in the funerary context, and how it participated in a broader set of expectations about life, death, and what might follow.

6.1. Choosing and Using the Necklace

Unlike public artworks, personal jewelry worn on the body must be accepted aesthetically by the wearer and her family. When such objects are further understood as possessing protective or apotropaic power, their use presupposes at least a basic recognition of their symbolic meanings. The Li family traced their origins to northern Xianbei traditions, and their early social standing was founded primarily on military achievement and aristocratic status rather than on classical learning or literary reputation. This background suggests that the family may have retained a sensitivity to steppe traditions and material symbolism, providing a basis for understanding and accepting a necklace with multiple cultural origins.

The deer motif featured on the necklace may have been one such key factor. In steppe cultures, the deer carried long-standing and stable symbolic meanings, and related imagery had already appeared in Xianbei and northern jewelry traditions. A gold buyao excavated at Baotou, Inner Mongolia, dated to the 4th–6th centuries, uses a deer’s head as its base, with antlers extending upward and adorned with numerous dangling gold leaves, forming a tree-like structure (Figure 15). This combination of deer and “tree” is not unique to the steppe but also appears in materials from Central Asia, including finds from the Khokhlach cemetery and the Tillya Tepe crowns. Such imagery is commonly understood as reflecting northern conceptions of natural order, life continuity, and sacred power. This symbolic language may also find an echo in the courtesy name of Li Min, whose courtesy name, Shusheng 树生, literally means “born from a tree.” Studies further indicate that shamanic beliefs and shamans played an important role in early Xianbei polities, and that against the backdrop of the successive rise of nomadic powers such as the Rouran and the Turks in the 6th–7th centuries, these symbolic systems continued to circulate among northern elites and may have been reactivated.

Figure 15.

Deer-antler-shaped gold buyao, 4th–6th century, Baotou, Inner Mongolia, China. Photograph by the Weibo user Song Song Fa Wenwu Ziliao Jun 松松發文物资料君, used with permission. The image provider explicitly states that all images are open for reuse with attribution. Source: Weibo https://weibo.com/u/2041266127 (accessed on 10 December 2025).

The strong atmosphere of Hu 胡—used in early medieval Chinese sources to denote peoples and cultural practices from Inner Asia and the Western Regions—together with sustained interaction with non-Chinese groups, formed an important context that enabled aristocratic and official families such as the Li clan to understand the symbolic language of foreign jewelry. Gold rings set with nicolo intaglios excavated from elite tombs of the Northern Dynasties and the Sui period provide clear evidence of this familiarity. For example, the nicolo gems on the rings worn by the wives of Li Xian and Li Xizong depict a nude dancing woman and a deer accompanied by three pomegranates, respectively—motifs commonly interpreted as symbols of fertility and abundance (Figure 8c,e). In contrast, the nicolo gems on the rings of the military figures Xu Xianxiu and Lü Da depict robust men wearing lion-head helmets, clearly signifying martial strength and divine power. These examples indicate that elite groups of the period did not treat such foreign jewelry merely as decorative objects, but were able to recognize their symbolic meanings and to select them accordingly. The necklace worn by Li Jingxun was likely chosen within this same framework of understanding, with its connotations of guidance, fertility, and protection aligning closely with family expectations for a young child.

The gilt silver ewer excavated from Li Xian’s tomb and the stemmed cup found in Li Jingxun’s burial were likely not merely luxurious foreign drinking vessels. Both types of objects recur in Turkic–Sogdian funerary and religious contexts and are closely associated with Zoroastrian-related ritual practices among Sogdian communities. On the stone sarcophagi of An Jia and Shi Jun, Sogdian-associated Zoroastrian ritual scenes are carved in relief, with offering tables prominently displaying stemmed cups and ewers (Figure 16). Moreover, Parsi communities (Zoroastrian groups who migrated to South Asia) continue to employ stemmed cups in haoma rituals, a central ritual involving the sacred drink haoma in Iranian religious traditions, to this day (Avesta.org 2025). Taken together, these materials suggest that stemmed cups and ewers fulfilled relatively stable ritual functions within Sogdian–Zoroastrian traditions. Given the long-standing and close interactions between the Li family and Sogdian groups, it is difficult to imagine that such objects were adopted without at least some awareness of their ritual use and cultural significance.

Figure 16.

Stemmed cups and ewer-shaped pitchers on an offering table, 6th century, tomb of An Jia, Xi’an, China. Reproduced from the officially published archaeological report (Yin et al. 2001, pl. 9).

On this basis, it is reasonable to suggest that the Li family’s acquisition and burial of these objects was not an accidental assemblage, but rather the result of a conscious combination of items understood to possess specific religious and ritual meanings in Central Asia. Notably, some female stone statues found within the sphere of Western Turkic influence depict figures wearing crowns, segmented necklaces, and bracelets, while holding stemmed cups (Figure 17). Although scholars differ in identifying these figures—as goddesses, shamans, or elite women imbued with sacred attributes—the overall assemblage consistently conveys dignity and sanctity. By comparison, the floral tree-shaped gold headdress, segmented necklace, gold bracelets, and stemmed cup found in Li Jingxun’s tomb closely correspond to these Central Asian configurations. In light of the frequent political and diplomatic contact between the Sui court and the Western Turks, such similarities may be understood as evidence of shared ritual aesthetics and religious sensibilities.

Figure 17.

Stone statue of a Turkic noblewoman, 6th–8th century, Issyk-Kul, Kyrgyzstan. Author’s line drawing after Zolotnikova (Zolotnikova 2017, fig. 6).

6.2. Living on, Rebirth, and Salvation: Multiple Afterlife Expectations in One Burial

When the necklace is reconsidered within its funerary context, Li Jingxun’s tomb reveals several coexisting conceptions of the afterlife: the continuation of life in the underworld, rebirth or renewal, and aspiration toward salvation in the Buddhist Pure Land. These ideas are not entirely consistent with one another, yet they were all incorporated into a single funerary arrangement by her family.

According to Sui funerary practice, the deceased’s body was washed, prepared, and redressed after death. The necklace, originally worn in life, was therefore put back onto Li Jingxun during the burial ritual. A notable structural feature of the necklace is that its clasp can be detached and reversed, allowing the deer motif to appear either upright or inverted. Archaeological line drawings record the state of the necklace at the time of excavation: when laid flat, the deer appears inverted, producing an awkward visual effect. In contrast, the National Museum of China displays the deer upright, which conforms more readily to modern visual expectations (Figure 1). The crucial issue, however, lies in the wearing of the necklace. When worn on the back of a standing body, the orientation of the deer changes with bodily posture: an inverted deer becomes upright when imagined on an upright, moving figure. In other words, when the family re-adorned Li Jingxun, they chose an orientation that appeared less visually pleasing to the living observer but was correct in a context of bodily use and movement. This suggests that the necklace was not treated as a static funerary display, but as an object meant to be worn and used in another world. For the family, Li Jingxun was not simply placed in the tomb; she was imagined as able to rise, walk, and continue living elsewhere.

This expectation of her continued existence in another world is also reflected in the overall arrangement of the burial. The stone coffin was carved in the form of a palace hall, surrounded by stone slabs that formed a courtyard. Inside the “palace,” objects needed for daily life were placed, while ceramic figurines were arranged outside, reproducing a familiar hierarchy of master and attendants. The same severe curse inscription, “May whoever opens this die,” was both carved on the coffin and on the surrounding slabs, emphasizing sealing, protection, and inviolability. The burning of travel documents and paper substitutes (paper clothing, money, or substitutes for valuables) at the time of placing the epitaph further prepared her for passage, use, and consumption in another world. This entire arrangement does not point toward transcendence from worldly life, but rather toward a deeply traditional Chinese wish: that she might live safely, comfortably, and with support in the afterlife—treating the dead as if still alive.

At the same time, key elements of the burial clearly diverge from conventional elite tombs and instead closely resemble practices associated with the deposition of Buddha relics. The tomb was located within a monastery; although the coffin resembled a palace externally, its opening and mode of use were closer to that of a sealed reliquary; the coffin was placed at the center of a vertical pit rather than against the tomb wall; and a pagoda was erected above the burial rather than a mound. These features form a coherent system, and all correspond to the Buddha relic deposition practices in the Sui period. Between 601 and 604, Emperor Wen of Sui carried out three large-scale distributions of the Buddha’s relics and oversaw the construction of numerous pagodas. Archaeological evidence shows that the Buddha’s relics were typically placed in stone caskets set at the center of vertical pits, enclosed by stone slabs, with a pagoda built above (Ran 2013, pp. 34–99). As a member of the imperial household, Yang Lihua almost certainly witnessed and participated in these events. It is therefore unsurprising that, several years later, she would draw upon this model when arranging Li Jingxun’s burial within a monastery.

The epitaph makes this intention explicit: “A multi-storied structure was built above the grave, echoing the jeweled pagoda, in the hope that she might resemble a lotus child; her body was forever stored in sacred ground, that she might remain close to the Dharma.” Here, burial in a monastery, imitation of relic deposition, and construction of a pagoda were not intended to extend life in the underworld, but to facilitate rebirth in the Buddhist Pure Land, allowing her to approach the Buddha as a lotus child. This stands in clear contrast to the palace-like, worldly arrangements of daily life, revealing two distinct orientations coexisting within the same burial.

The timing of the burial and the accompanying ornaments add yet another layer—that of renewal and rebirth. The six-month interval between death and burial may have allowed time for pagoda construction, but it also appears to have awaited an auspicious moment: Lichun 立春 (Beginning of Spring). The funeral was held one day before Lichun, and Li Jingxun’s headdress—shaped like a cluster of gold flowers, topped with a winged moth and flanked by spring banners—directly corresponds to Lichun customs of wearing spring banners to ward off evil and invite good fortune (Yang 2019). Lichun marks the return of yang energy 阳气 and the start of a new cosmic cycle. Burying a child at this moment carries a strong implication of renewal. Complementing this temporal symbolism is the guiding function attributed to the necklace: in shared steppe shamanic traditions, the deer serves as a messenger across boundaries, guiding souls between worlds. The combination of spring banners, Lichun, and the deer-motif necklace expresses a concrete hope—that at the moment when boundaries are redrawn and seasons renewed, the child’s soul might be guided and protected toward a new destination, whether rebirth, return, or salvation.

Thus, the burial does not commit to a single doctrinal vision of the afterlife. Instead, it represents an attempt to prepare for multiple possibilities: equipping her for continued life elsewhere, opening a path to the Pure Land through Buddhist forms, and invoking seasonal renewal as a means of restarting life itself. These elements may appear contradictory, but they point to a single emotional reality: the family could not accept her early death and therefore placed multiple possible routes into the burial, hoping that wherever she went, she would be helped. Such a combination should not be understood as exceptional. In early medieval China, shaped by nearly three centuries of multiethnic interaction and sustained exchange with Inner Asia and the western regions, religious life was rarely exclusive. Funerary practice in particular often integrated Buddhist, indigenous, and foreign ritual logics, reflecting a pragmatic and emotionally driven approach to belief rather than adherence to a single, unified doctrine.

Ultimately, this complex arrangement returns to a desire to keep her close. Li Jingxun was buried in Wanshan Nunnery, a site with particular historical significance: after the fall of the Northern Zhou, palace women were forced into collective monastic life there, meaning that many inhabitants of the nunnery remained closely connected to Yang Lihua’s former world. The monastery’s proximity to the palace also made it easy for Yang Lihua to visit and mourn her granddaughter. Li Jingxun’s death may have constituted yet another devastating blow to Yang Lihua; roughly half a year after the funeral, Yang herself died. In accordance with ritual regulations, she was buried beside Emperor Xuan of Northern Zhou, spatially separated from her beloved granddaughter. Yet in the family’s imagination, they may still have hoped for reunion in another world. For this grandmother, the monastery and pagoda, the palace and courtyard, the spring banners and Lichun, were not mutually exclusive belief systems, but different languages expressing the same emotion: a refusal to let the child disappear, and a desire that she be protected, guided, and carried to a better place.

7. Conclusions

This study has shown that Li Jingxun’s gold necklace cannot be explained adequately through stylistic attribution alone. Although often discussed in terms of Persian, Byzantine, or Indian influence, the necklace is better understood as a product of the Iranian–steppe cultural sphere and the Turkic–Sogdian exchange networks active in the late 6th and early 7th centuries. Within the Chinese archaeological record, it remains a unique object, but its segmented structure, large gold beads, nicolo intaglio, and gem-setting techniques find close parallels in Central Asia and the wider Iranian world, where such ornaments functioned as markers of elite status and sacralized authority.

At the same time, the necklace’s significance in Sui-dynasty China was not limited to its foreign origin. When examined as a whole, its design reveals a coherent symbolic logic. The stag on the clasp, the pearl rondelle surrounding the red central stone, the controlled use of blue and red gemstones, and the pendant positioned along the vertical axis work together as a system concerned with protection, fertility, and renewal. Rather than treating these elements as isolated motifs, this article has shown that they draw on shared Eurasian traditions—steppe ideas of the deer as a guiding and protective being, Iranian and Sogdian associations between gems, number, and cosmic order, and funerary uses of amuletic objects intended to secure safe passage and continued vitality after death. In this sense, the necklace functioned not simply as ornament but as an apotropaic object whose meaning depended on being worn on the body.

The ritual role of the necklace becomes clearest when it is placed back into the specific context of Li Jingxun’s burial. The palace-shaped stone coffin, the arrangement of daily use objects, the curse inscriptions, and the burning of paper offerings all express a wish that the child might continue to live in another world. At the same time, burial within a Buddhist monastery, the construction of a pagoda, and the imitation of relic-deposition practices point toward hopes for rebirth in the Pure Land. The timing of the burial around Lichun and the use of spring imagery add a further layer of meaning, linking death to seasonal renewal. These elements do not form a single, consistent doctrine, but they do form a consistent emotional response: the family prepared multiple paths—continued existence, rebirth, salvation—so that the child would not be left unprotected.

By following the necklace from its probable Central Asian cultural background to its use in a Sui aristocratic burial, this article highlights how foreign objects on the Silk Roads were not passively adopted. Instead, they were actively understood, selected, and integrated into local ritual practices. Li Jingxun’s necklace shows how transcultural material forms could be mobilized to address deeply personal concerns—grief, protection, and the hope for renewal—within early medieval China.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.Z.; methodology, Y.Z.; formal analysis, Y.Z. and Z.W.; investigation, Y.Z., Z.W. and X.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.Z.; writing—review and editing, Y.Z., Z.W. and X.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable. No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Akbarzadeh, Daryoosh. 2022. A Note on Sasanian Glassware and Zoroastrian Sacred Numbers. Iranian Journal of Archaeological Studies 12: 37–45. [Google Scholar]

- Akbarzadeh, Daryoosh. 2023. Sacred Beads of Pearl Necklaces of Sasanian Kings Based on Their Coins. Iranian Journal of Archaeological Studies 13: 103–16. [Google Scholar]

- Aruz, Joan, Ann Farkas, and Elisabetta Valtz Fino. 2006. The Golden Deer of Eurasia: Perspectives on the Steppe Nomads of the Ancient World. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. [Google Scholar]

- Avesta.org. 2025. Ritual Implements of Zoroastrianism (Alat). AVESTA—Zoroastrian Archives. Available online: https://www.avesta.org/ritual/alat.htm (accessed on 7 October 2025).

- Callieri, Pierfrancesco. 1990. On the Diffusion of the Mithra Images in Sasanian Iran: New Evidence from a Seal in the British Museum. East and West 40: 79–98. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Yimin 常一民, Jingrong Pei 裴静蓉, and Pujun Wang 王普军. 2003. Taiyuan Bei Qi Xu Xianxiu mu fajue jianbao 太原北齐徐显秀墓发掘简报 [Preliminary Excavation Report on the Northern Qi Tomb of Xu Xianxiu in Taiyuan]. Wenwu 文物 [Cultural Relics] 10: 4–40. [Google Scholar]