Abstract

The article focuses on demonstrating the connections between works of visual art and their musical representation—in the sense of a musical response to a work that served as a source of inspiration. The discussion focuses on works by outstanding composers: Zbigniew Bargielski (born 1937), Zygmunt Krauze (born 1938), and a younger composer, Bettina Skrzypczak (born 1961). Among the distinguished artists are also the authors of works of visual art that provided the “causative impulse” for musical compositions: Władysław Strzemiński (1893–1952), Tadeusz Mysłowski (born 1943), Alberto Giacometti (1901–1966). Their works, taken into account by the composers, belong to various genres of visual arts: Strzemiński’s unistic painting fascinated Z. Krauze (including Unistic Compositions for solo piano), Mysłowski’s multimedia objects inspired the musical imagination of Z. Bargielski (Shrine for Anonymous Victim, Light Cross, Towards Organic Geometry), while Giacometti’s sculptures prompted B. Skrzypczak to interpret them musically (Vier Figuren). The methodological basis for developing the topic was the concept of ekphrasis, introduced into the field of musical semiotics (as musical ekphrasis) by the German musicologist Siglind Bruhn, as well as the work by Jacek Szerszenowicz, Artistic Inspirations in Music (2008), whose author, in the Polish context, undertook research on capturing the nature of the relationship between the extra-musical source of inspiration (artistic works) and music.

1. Introduction. Methodological Inspirations

The subject of consideration in the present paper is the issue of the peculiar mediation of a musical work by a work representing a field of art other than music and acting as a source of inspiration—the causal impulse. The cases under discussion are works by eminent visual artists: Władysław Strzemiński (1893–1952)—unistic compositions which inspired Zygmunt Krauze (b. 1938); multimedia objects by Tadeusz Mysłowski (b. 1943), which inspired the musical imagination of Zbigniew Bargielski1 (b. 1937); and Alberto Giacometti’s (1901–1966) Four Sculptures, which find their musical interpretation in the composition Vier Figuren by Bettina Skrzypczak, a Polish–Swiss composer of a younger generation (b. 1961). Both the visual artists and the composers who responded to the works of visual artists with their musical work are among the outstanding representatives of the art scene of their time.

The methodological basis for the development of this topic is the concept of ekphrasis, introduced to musical semiotics (musical ekphrasis) by the German musicologist Siglind Bruhn, acting in America. According to Bruhn:

Like poets, […] composers can respond in different ways to visual representations. They can transpose aspects of both structure and content and/or extend their meaning […].(Bruhn 2001; quoted in Malecka 2006)

In Poland, research on capturing the nature of the relationship or, in other words, the nature of the mediation of music by an extra-musical source of inspiration, was undertaken by Jacek Szerszenowicz. In his book Visual Inspirations in Music, he explains:

The concept of inspiration—in terms [of] encompassing all the moments of this phenomenon from impulse to effect—presupposes the existence of a chain of cause-and-effect relationships linking three groups of factors:

- (1)

- the source of the impulse—its nature and mode of impact;

- (2)

- the characteristics of the subject being influenced—in particular their artistic and aesthetic attitude and individual psyche;

- (3)

- the characteristics of the artwork that can be considered as traces of the impact and transformation of the stimulus in the creative process (Szerszenowicz 2008).

Szerszenowicz’s insights can be adapted as methodological tools, especially to the extent set out by the first and third points, which focus the analyst’s attention primarily on the characterisation of sources of inspiration and on “tracking” the traces of their influence on the “shape” of music at different levels of its organisation and impact, i.e.,: structural features (style), aesthetics, expression. On the other hand, the suggestion in the second point mentioned by Szerszenowicz in this chain of cause-and-effect relationships between source of inspiration and musical outcome seems debatable. It is rather difficult to characterise or diagnose, without running the risk of oversimplification, the individual psychological type of the creator—and therefore the subject of influence, especially in the case of living composers. One can only conclude, on adequate grounds, that a particular work or works of art proved to be a source of fascination, while the composer’s sensitive personality, obviously remaining in a state of permanent preoccupation, usually articulates as more valuable all that is ambiguous, understated, veiled, ephemeral, all that carries some kind of mood, represents an impressionistic nature and at the same time stimulates the sphere of perception … These preferences resonate in their own way in the work of each of the composers considered in the present paper, which, let us note, constitutes important information about their artistic and aesthetic world-view. Let us start with Krauze, whose works are dominated by the concept of unism, with measures akin to minimal music; Bargielski’s works are characterised by a definitely Romanesque rhythm; while the works of Skrzypczak are part of post-avant-garde art.

Visual Arts as a Source of Inspiration in the Oeuvre of Zbigniew Bargielski, Zygmunt Krauze, Bettina Skrzypczak

The oeuvre of Zbigniew Bargielski, representing various genres, attracts our attention with compositions inspired by the works of visual artists—above all, representatives of the 20th century and present times: Wacław Szpakowski (1883–1973), Anna Szpakowska-Kujawska (b. 1932), Wojciech Krzywobłocki (b. 1938), Tadeusz Mysłowski (b. 1943). It is not a dominant trend if we measure it by the number of compositions, as there are only seven of them, created between 1992 and 2011: Music of the Infinite Lines (1992), Mutationen’92 (1992), Shrine for Anonymous Victim (1999), Light Cross (2000), Towards Organic Geometry (2001), A.S.K. Auto portrait (2004), Trans-sonans2 (2011)], but it is undoubtedly an important trend which proves the composer’s interest in interdisciplinary multimedia activities, and not in a strictly experimental sense or with a desire to be innovative, ‘en vogue’, but rather in the sense of a search for a means capable of realising the imperatives of the imagination.

In the case of Zygmunt Krauze, at the end of the 1950s, the unistic compositions assured him, as he was then entering the compositional scene, the status of a radical innovator. However, the perspective of the years that have passed creates a rather important distance that allows for reflections beyond viewing Krauze’s unism solely in terms of the avant-garde past. Thanks to the path taken at that time, he not only avoided unconditional submission to the dictates of the avant garde (with its dominant features of the time: dodecaphony, serialism, aleatorism, Polish sonorism) but also found his own form of expression (which, several years later, can be seen as an expression of opposition to the proposals brought in by the said avant garde) and “[….] delimited a separate and very individual area in the Polish post-war music […]” (Szczepańska 1997). Krauze’s fascination with the unistic painting compositions of Władysław Strzemiński gave him the courage to follow his own path, which determined the stylistic idiom of the composer’s entire oeuvre.

In the case of Bettina Skrzypczak, a Polish–Swiss composer, fascination with a work representing the visual arts—the sculptures of Alberto Giacometti—inspired only one composition presented in the present paper.

The mutual influence of works of visual art and music and attempts at their harmonisation and correspondence invariably focus the attention of creators, creating an interesting and important research space, the aim of which is the immeasurable artistic potential of human creativity.

2. Mysłowski—Bargielski

The result of Zbigniew Bargielski’s cooperation with visual artist Tadeusz Mysłowski (born 1943) are multimedia projects on various topics with the following titles: Shrine for Anonymous Victim, Light Cross, Towards Organic Geometry.

For many years, Mysłowski has been absorbing the heritage of modernist theories [as Szymon Bojko notices] and transforming them into his own linear-spatial system. Drawing on the legacy of the works and ideas of Kazimierz Malewicz, Piet Mondrian, Władysław Strzemiński, Katarzyna Kobro, Henryk Stażewski and, recently “discovered”, Wacław Szpakowski, he creates reality out of geometric and organic abstraction. He has also joined the non-figurative art movements of the Polish and American avant-garde of the 1960s. […]. Mysłowski begins his recording of spatial code at the point where his predecessors have finished.(Bojko 2011)

2.1. Shrine for Anonymous Victim (1999)

It is universally known that Majdanek in Lublin (Poland) is the location of the second greatest genocide after Oświęcim during World War II. A German concentration camp operated there, where about 235,000 people of 52 nationalities died. On the 50th anniversary of liberation (23 July 1994), some former prisoners of Majdanek published a testament—a kind of message or appeal—which reads as follows:

[…] we, the former prisoners of this camp who are still alive […], express a wish that at least a token roof be built over Majdanek, unconnected in any way to any religion or group, under which every man without exception could take shelter and where everyone could discover the true meaning of this place, the sense of existence and one’s own fate. We wish this roof to be called a Shrine of Peace, as this primeval name fully conveys its intended function.(Karkowski 1999)

The challenge was taken up by Tadeusz Mysłowski, an artist from the Lublin region who has lived in New York since 1970.

As far as he could, Mysłowski based his artistic expression on the abstract geometric language which he had been exploring for many years in his painting, graphic art, and sculpture. He claims only that this language is open, […] it does not affect our senses directly, but still it speaks to us with unusual power. Mysłowski chose an installation—a new form of artistic expression which had never been used at such places as a concentration camp.(Karkowski 1999)

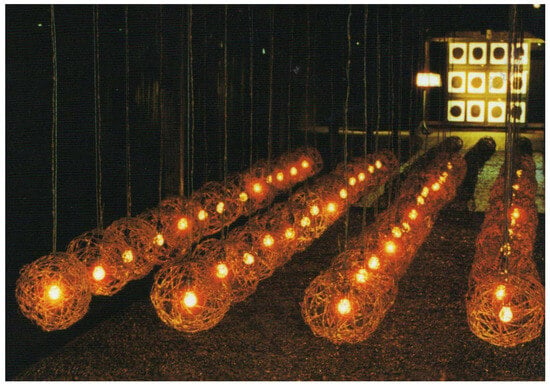

One of the barracks (no. 47) was chosen as the venue for the exposition (see Scheme 1):

Scheme 1.

Tadeusz Mysłowski, installation Shrine for Anonymous Victim (Lublin, The State Museum in Majdanek, a permanent exposition since 23 July 1999). Photo: Tadeusz Mysłowski [from the author’s collection].

[…] the entrance inevitably makes you think of the famous quote from Dante: lasciate ogni speranza (leave all hope behind). We are surrounded by a deep, almost tangible darkness. It is filled with quiet, but nerve-racking music and whispered prayer: with voices from the past, or even from the beyond. Two platforms sprinkled with small pebbles emerge from this darkness. Over the first one, 52 balls woven of barbed wire and filled with faint light have been hung. Some life still flickers here, but when we move a step further, where the second platform starts, we enter the sphere of death. The balls here are empty and dark, they do not sail in the air, but they lie on the pebbles filling the platform. There is dread and despair, death and emptiness. And then there is a secular altar which ends this way of the Cross, and a book of obituaries which commemorates each of the 52 nationalities of the Majdanek prisoners. Those simple symbols, understandable to everyone, regardless of nationality and religion, convey the essence of the shrine and the message of its authors.(Karkowski 1999)

Mysłowski invited Zbigniew Bargielski to contribute to the creation of this unique monument and the composer, inspired by Mysłowski’s spatial idea and its symbolism, created a musical “pendant” harmoniously complementing the whole work. Bargielski’s music contributes, above all, to the emotional sphere and intensifies expression. The means used by the composer are almost ascetic: gradually superimposed sound-tracks form a multi-tone chord (as if in a cluster), which engulfs the interior of the barrack in a quadraphonic projection. The music creates a serious but, at the same time, peculiarly tense, prayerful mood. Against the background of the music, we can hear the prayer Our Father recited in several languages: in Hebrew, Ukrainian, Polish, and in an undefined language created by the composer to symbolize all the remaining nationalities of the camp prisoners. Additionally, the level of expression is intensified by whispered accounts given by the surviving camp prisoners. The 29-min composition is cyclically repeated3.

2.2. Light Cross (2000)

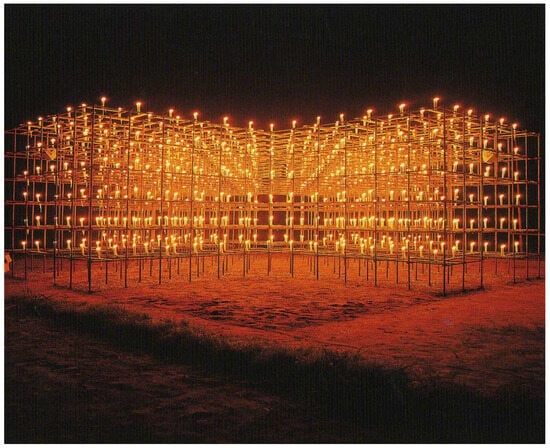

The source of inspiration and the point of reference for musical activity in this composition was the visual object connected with Tadeusz Mysłowski’s project that took the form of a monumental (multi-storey), even-armed cross structure made of metal, built in an open space, and illuminated by burning torches (see Scheme 2).

Scheme 2.

Tadeusz Mysłowski, Light Cross (Echigo–Tsumari Art Triennale 2000, Japan, September 2000). Photo: Tadeusz Mysłowski [from the author’s collection].

In his commentary, Zbigniew Bargielski describes the source of inspiration and reveals the means of the composer’s technique which shaped the musical material of the monument:

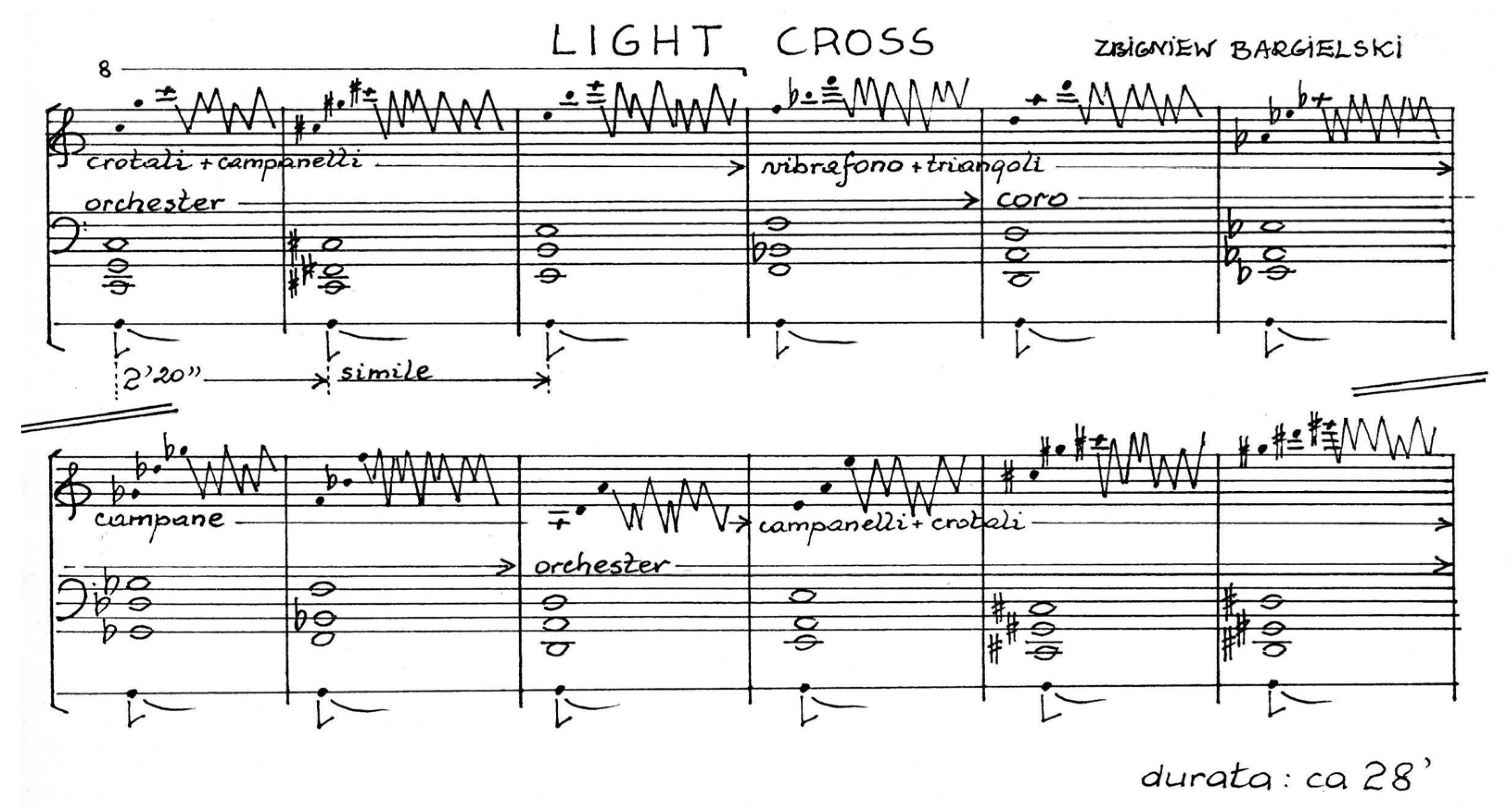

I composed Light Cross inspired by Tadeusz Mysłowski’s work. It seems that its construction includes two elements: a permanent one, which is the cross structure, partly framed by the stable “platform”, and a spherical one, rolling and twinkling with hundreds of lights. I have moved both elements to the world of music. The permanent element is represented by 12 simple chords in the lower register—each of them lasts for about 2′20′. The spherical element is represented by various, quite short, single tones of high-pitched instruments; this is the sound picture of twinkling lights.(Przech and Ledzińska 2012)

The expression “high-pitched instruments” refers to virtual instruments, as the musical layer of the composition was produced in studio conditions at Bruck an der Mur in Austria (see Figure 1). The multimedia composition Light Cross by Mysłowski and Bargielski was commissioned by the Echigo–Tsumari Art Triennale 2000 in Japan, where it was presented for the first time (2000).

Figure 1.

Zbigniew Bargielski, Light Cross (draft of the composition). Reproduced from composer’s manuscript [with the composer’s permission].

2.3. Towards Organic Geometry (2001)

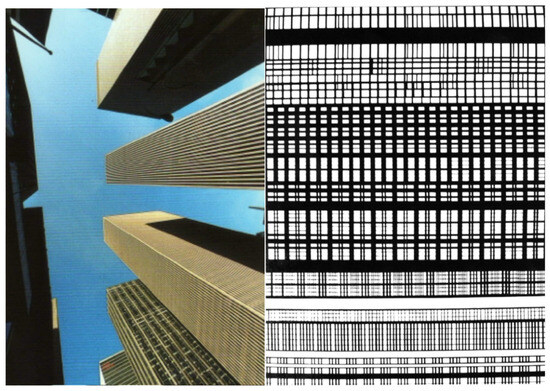

Mysłowski—as Andrzej Turowski comments:

looks at the city just like painters who used to paint great panoramas and unique cartographic landscapes. He does not single out any particular point of view, he forgets about the predominating perspective and invites the audience inside, […] he wants them to wander with the author around the limitless map of topographical spectacle, within the geometry of glass walls, soaring columns, broken cornices and light reflections. Rummaging around the city, they—the spectators and the artist—stop at every detail, look into every backstreet and try to understand the sense of the effort involved and to find the order in the city chaos. With modernistic faith, […] they seem to reach a point where it is possible to start everything anew—the geometric pre-shape of a square. […] A square—an elementary form of artistic practice, a rhetorical figure of contemporary time, a basis of an architectonic structure, a choreographic representation of a city […]. The spatial and planar geometry of a square is the rhythm of time. This rhythm accompanied the first constructivists—Katarzyna Kobro and Władysław Strzemiński—just like it accompanied Mysłowski.(Turowski 2011)

Zbigniew Bargielski interprets Mysłowski’s graphic art (see Scheme 3) as “[…] a metamorphosis of a finished ‘product’ (a pure architectonic structure), which by undergoing a series of ‘minimizing’ photographic procedures reveals its organic ultimate cause, a natural ‘atom’ out of which further synthetic patterns are born, more and more distant from their natural prototype” (Bargielski 2011).

Scheme 3.

Tadeusz Mysłowski, Towards Organic Geometry (compositions presenting transformed photographic depictions of New York, from a maximum, global view to optimal minimised images). Reproduced from Tadeusz Mysłowski, “New York City Crisscross”, [in] Towards Organic Geometry 1972–1994, New York 1994, Irena Hochman Fine Art Ltd., p. 15 and p. 82. [Reproduced with T. Mysłowski’s permission].

The composer explains:

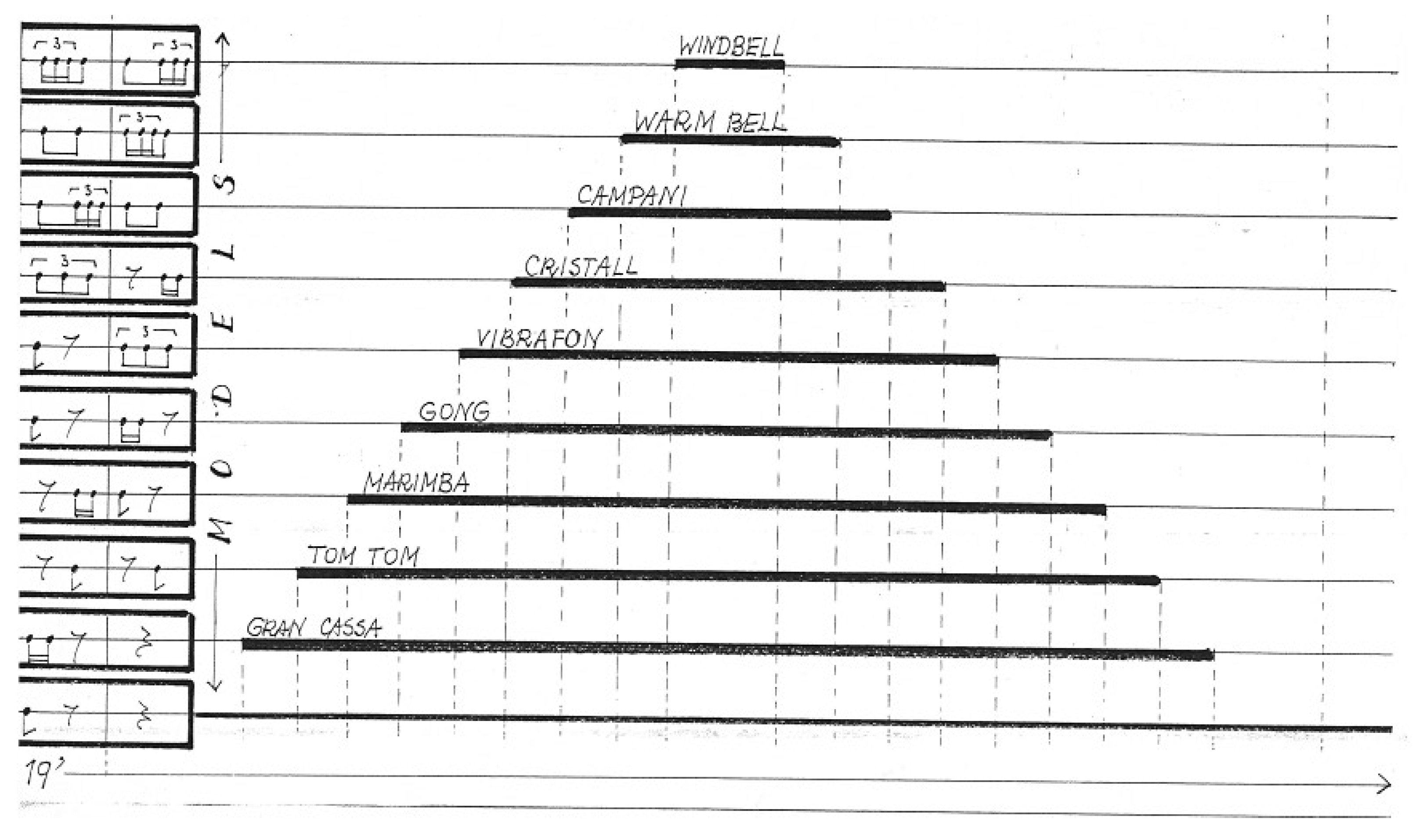

The same refers to my musical version of Towards Organic Geometry, in which, taking heartbeat as a natural source and point of departure, I create complicated rhythmical patterns, and then, by gradually thinning this network of rhythmical interrelationships I bring this sound construction back to the original point of departure, to “the ultimate cause” of all those events. And so, this is a metamorphosis: from the most basic, natural rhythm, to its almost “geometrical” breakup and structural culmination, to “a backward movement” that reduces the material complexity—this is how I finally reach again the simple, natural and obvious form that is human heartbeat.(Bargielski 2011)

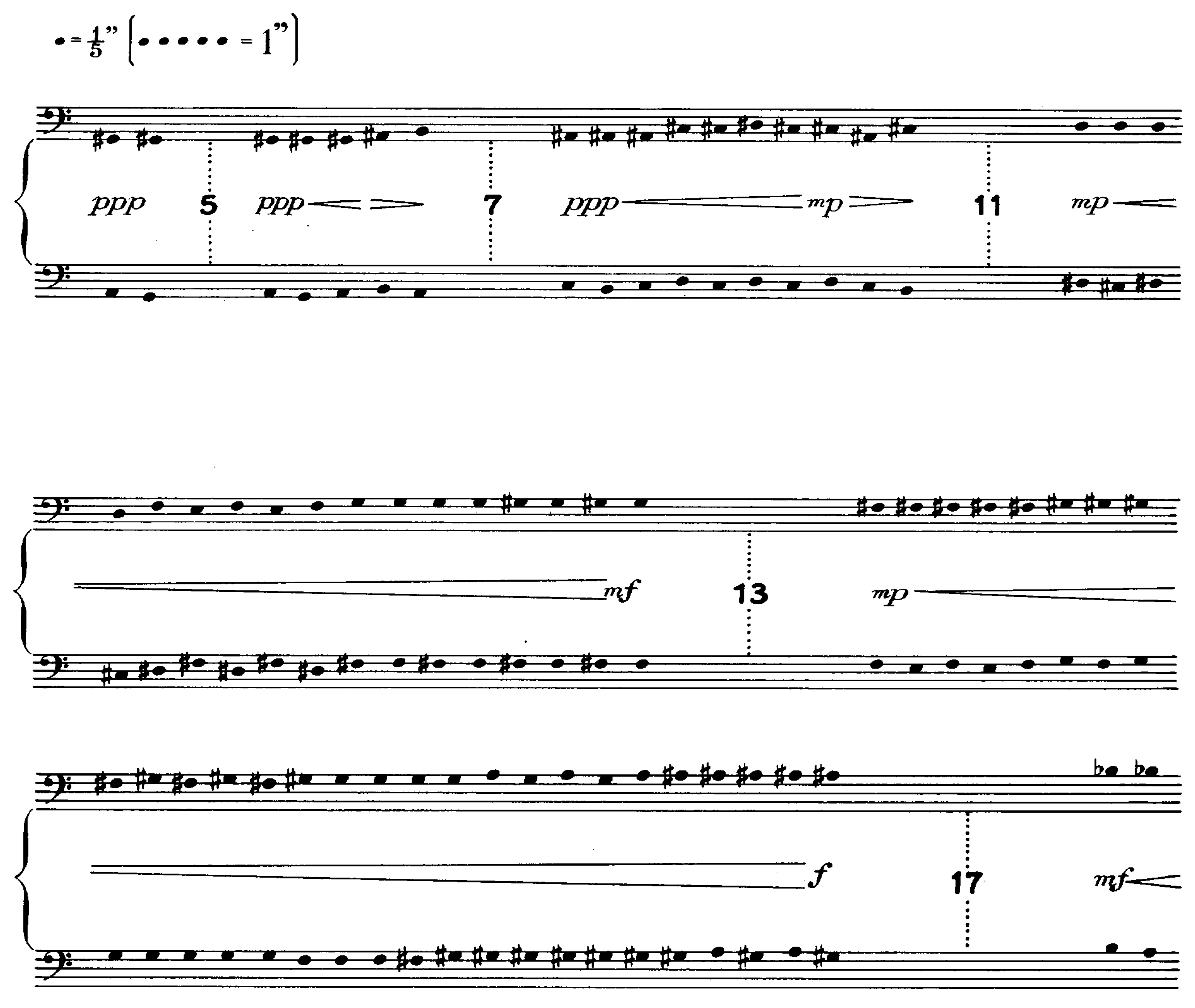

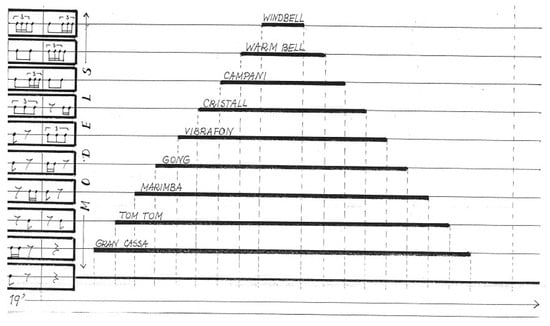

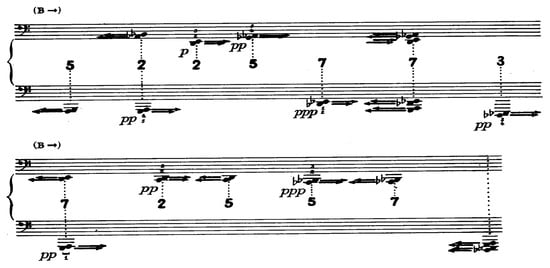

The shared expressive element of pulsating rhythm, which, in its changing intensity, spreads through time–space unidirectionally (back and forth), as it were, unites the ideas of the two artists into a coherent whole. The musical composition lasts about 19 min, and its outline is based on the principles of symmetry, parallelism, and exact proportions. Those ideas are reflected in the score layout, which the composer has described as “a musical Christmas tree”, as the lowest level (the fundamental layer) is defined by the heartbeat rhythm, while the subsequent layers become increasingly short and blur the effect of the fundamental layer to expose at the end the archetypal element, that is, the human heartbeat, again (see Figure 2)4.

Figure 2.

Zbigniew Bargielski, Towards Organic Geometry (draft of the composition). Reproduced from the composer’s manuscript [with the composer’s permission].

Towards Organic Geometry was presented many times in its multimedia form in Poland, for example, during the 1st “Codes” Festival of Traditional and Avant-Garde Music in Lublin (22 May 2009) or at the International Cultural Centre in Cracow (20 January 2011).

3. Strzemiński—Krauze

3.1. Unism in Painting5

The unistic concept was born in painting on the basis of the pre-war constructivist avant garde. Its founder and, in fact, its only orthodox representative was Władysław Strzemiński (1893–1952), a Polish painter, art theoretician, and engineer by education. Born in Minsk, he studied at the Moscow Military School of Civil Engineering, then, as an officer in the Tsar’s army, took part in World War I, from which he returned severely mutilated with the intention to devote himself entirely to art (Stopczyk 1988). According to Stanisław Krzysztof Stopczyk, the distinctive features of Strzemiński’s works were:

[…] the absence of a single, stable “style”, whose rationale could be justified by constant internal refinement. This apparent vacillation of conviction [as Stopczyk further states] represented by the inspired patron of the Polish avant-garde is strongly motivated by the assumption that:

[…] every work of art, in the permanent process of cognition through art, should bring new discoveries in the sphere of form, should be a new invention or even the beginning of a painting school.(Stopczyk 1988)

In this perspective, the emergence of the unistic concept can be seen in terms of a peculiar idea, an idea that made a significant contribution to the artist’s research process, that was all the more valuable—it seems—insofar as it brought new discoveries in the sphere of artistic cognition. Strzemiński was actually an advocate, or even a fanatical apologist, for the autonomous values of the painting:

[…] it is the content of the work of that define its perfection—not the reflection and recounting of another content, experienced elsewhere and then finding its trace and reflection in the form of a work of art.(Strzemiński 1924; quoted in Stopczyk 1988)

This view is fully reflected in the artist’s unist theory and works, which were directly influenced by the suprematism of Kazimir Malevich (the creator and leading representative of this abstract–geometric faction in painting, which appeared around 1915 based on cubism). For it was in the environment dominated by Malevich that the artistic personality of the creator of unism evolved. Open to Malevich’s suprematist abstraction, Strzemiński ultimately adopted from this movement the idea of pure feeling in art and, consequently, a contemplative way of experiencing the work, realised in a non-representational form, concentrated to the maximum, and reduced to the simplest elements (let us recall Malevich’s famous Black Square on White Background). These features of suprematism, combined with a critique of the Baroque formula in painting—which is dialectical in its very nature, exposing the central area of the painting—formed the doctrine of non-contrast painting, the so-called theory of unism.

In his writings, Strzemiński explains as follows:

In Baroque, line is understood as a sign of directional tension. Each baroque line is a dynamic sign. Each line, encountering another, closes as a result. Striking one line with another creates the closing of a painting. The form obtained this way is the result of the clash of forces, it has its centre produced by the pressure of the mutual directional tensions.(Strzemiński 1977; Szwajgier 1996)

According to Strzemiński, this formula has negatively affected the entire development of art up to the present day. He negated it and, at the same time, liberated thinking from this centuries-old hegemony, by proposing instead that

[…] [t]he dualist concept should be replaced by the unistic concept. Not the pathos of dramatic outbursts, not the grandeur of the forces, but a painting as organic as nature. […] Every square meter of the painting is equally valuable and participates to the same extent in the construction of the painting […]. The surface of the painting is uniform, so the intensity of the form should be distributed uniformly.(Strzemiński 1977)

In Strzemiński’s perspective, unistic painting is “the expression of the realised conviction that the fundamental law of absolute painting is the rejection of dynamism and the avoidance of the action of forms one on the other (i.e., the mutual neutrality of forms) […]” (Stopczyk 1988). In practice, this means eliminating the contrast of shapes against a background, reducing the principles of perspective, depriving the painted work of the impression of movement and thus the feeling of time in its horizontal dimension. Strzemiński pointed out that

[…] directional tension is a sign of movement and therefore contains an element of time. Instead of looking at the painting, we are forced to read it. The more directional tensions there are and the more collisions of one against the other, the greater the amount of time contained in the painting. […] The goal of our aspirations is a painting beyond time, a painting that operates solely on the concept of space.(Strzemiński 1977)

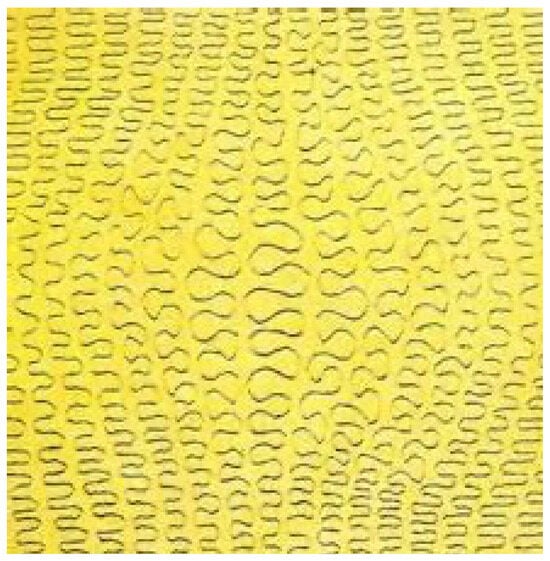

As a result, the unistic cues led to an optically homogeneous form made up of a collection of identical, small elements, quasi-grains or cells, slightly modified here and there, that fill the surface of the painting evenly (Scheme 4). Every bit of this surface is equally important; it acts on the viewer with the same level of intensity as the whole form. So, the fullness of the experience is provided by both the visual experience of the detail and the viewing of the textural whole. The universal idea of potential form, infinite in its essence, is thus inscribed in the work; the real, existing surface of the unistic painting is its fragment or perhaps a sample (Szwajgier 1996).

Scheme 4.

Władysław Strzemiński—Unistic Compositions No. 13 (1934). Access: https://share.google/images/hCYq0ak9sgNT0aceZ (accessed on 12 October 2025).

3.2. Alignment of Painting and Music

Krauze’s fascination with unism developed as much under the influence of Strzemiński’s unistic paintings as under the programme that formed the philosophical and ideological basis of this artistic movement.6 It is worth recalling that in the panorama of the European interwar avant garde, the theses propounded by Strzemiński were undoubtedly the most radical programme (Stopczyk 1988).

Having a sense of deep coupling with the achievements of Strzemiński7, Krauze formed his own compositional way of thinking, directing his experiments towards the search for equivalent technical and expressive means, the application of which would enable the transformation of visual impressions into the sonic (auditory) sphere of sensations. Due to the obvious separateness of the two artistic disciplines, however, a simple transfer of the principles of unistic painting to the field of music was not possible. That is why Krauze, in creating the musical formula of unism, treated Strzemiński’s assumptions as a kind of ideological support while treating the doctrine of non-contrasting form in a rather metaphorical sense, that is, he was confronted with the fact that it is impossible for a musical work to exist without containing some contrast. Contrast is inherent in the very essence of music considered as an acoustic phenomenon developing over time. The elements of the unistic painterly conception that proved particularly important and inspiring for musical artistic expression refer above all to an anti-dialectical understanding of form, which rejects all manifestations of the dynamisation of the course resulting from the internal oppositions of the elements. On this basis, we can identify a significant convergence of the works of both artists, visible at the level of their perception. This is because in both cases, we achieve an impression that is equal on the level of quality. Although the reception process engages different receptors, both the visual effect produced by Strzemiński and the sonic result of the musical construction, and even the purely visual view of Krauze’s scores, they are struck with the commonality of their form expressed by the homogeneous structure of the work.

3.3. Zygmunt Krauze’s Pieces for Solo Piano as Musical Representations of Unistic Painting

Distinct against the background of Polish piano music of the second half of the 20th century, Krauze’s original work for solo piano8 forms an important part of the composer’s oeuvre and is an expression of his fondness for this musical genre. In one of the published conversations conducted by Krystyna Tarnawska-Kaczorowska, the composer revealed a very personal, strongly emotional, approach to this instrument:

The piano is my love and actually a big part of my life. I simply cannot live without the piano […]. The piano is for me … it is so trivial, but I will say it… it is a source of strength, it is a source of energy and it is a support at times when I feel bad.(Tarnawska-Kaczorowska 1998b)

The extensive collection of compositions for solo piano consists of several dozen mostly small works (some included in collections) with individual textural and aural character (Tarnawska-Kaczorowska 2001). It is worth emphasising that all of the pieces were created at the instrument; and this is why they are closely integrated with its nature.

Krauze’s piano pieces are an excellent material to exemplify the stages of adaptation of painterly inspirations to the field of music: beginning with the period of searching for adequate means (Fünf Klavierstücke from a collection of around 20 unistic pieces composed between 1957 and 1958, cycle: Prelude, Intermezzo, Postlude from 1958, Sieben Interludien from 1958), through the stage of crystallisation of the unistic form (Ohne Kontraste from 1960, Five Unistic Compositions from 1963, Triptych from 1964), to the period of a less restrictive approach to the ideology of unism (Music Box Waltz from 1977, Nightmare Tango from 1987, La chanson du Mal-Aimé from 1990, Refrain from 1993). It is also worth noting that, apart from unism, which dominated the composer’s musical thinking and contributed significantly to linking Krauze’s work with the minimalist trend, in his piano works he undertook a certain polemic with the avant-garde tendencies engulfing the works of Polish composers after 1956. Thus, the presence of dodecaphonic principles for the organisation of sound material applies (only!) to the Ohne Kontraste miniatures; filiation with aleatorism (the idea of the open work) can be found in the Triptych; while the sonorist current acquired a highly individualised form (Przech 1998) in the piano miniatures Esquisse from 1967, Stone Music from 1972, and Gloves Music from 1972. However, it is difficult not to notice that this oeuvre is uninterruptedly pervaded by the same unistic idiom, present in both the sonoristic Stone Music and in the postmodern Refrain, whose aesthetic is shaped by the astonishing coexistence of unistic structural features with a lyrical–romantic type of expression. In an interview conducted by Beata Młynarczyk, the composer confirms this observation, saying the following:

[…] [A]lthough I have long since moved away from this [the unism], but certain elements of that aesthetic have remained, becoming, as it were, my alphabet in the use of sounds, in the treatment of form.(Młynarczyk 1998)

The essential components of this alphabet include the characteristic small-interval motivic cells, present in almost all his piano works. The essence of the functioning of these unistic-like motifs is explained by Krauze as follows:

I treat the use of similar motifs, similar elements as a building material. These are my bricks […]. I use them to make different pieces, to make different forms, to build different expressions, but this building material, this cell from which the piece is made, is one and homogeneous. […] Some of these motifs, of these building material, indeed constitute a kind of obsession […]. However, I feel a kind of need, which is also a limitation, to introduce this motif. […] I cannot give up that need. Even though I try. […] It is a kind of… simply a disease. A kind of a feature …, which the composer eventually concludes with the words: “I have my particular note”.(Tarnawska-Kaczorowska 1998a)

Krauze’s piano compositions, subordinated to the unistic concept, include examples of the manifestation of this concept which differ in quality.9 The overarching outcome, resulting from the assumption accepted in advance, implies specific workshop solutions that form a set of concrete and original compositional procedures that organise the structure of the work in both its micro and macro dimensions. The repetition of certain solutions, which in each case trigger the desired sound idiom, makes it possible to give them the status of referents of musical unism.

3.4. Microstructure Level

Strzemiński’s unistic painting is a peculiar concentrate of small, structurally identical or slightly modified elements, arranged in a specific pattern, densely filling the surface of the canvas. There seems to be a logical relationship here: the smaller the elements and the more direct their arrangement among themselves, the greater the impression of structural homogeneity. In the musical transformation, on the other hand, the surface of the painting transforms into a timeline. These are therefore the temporal aspect of the work’s projection and the different laws of perception associated with it that become important. Substantive homogeneity is evoked here through permanent fixation in the listener’s memory of the elements exposed at the beginning of the piece. On the one hand, the process of repetition and the continuity of this process—guaranteed by the return of the sound combinations given at the beginning of the piece, which uninterruptedly fill the time line—is of decisive significance, while, on the other hand, the frequency of these returns, determined by the size of the repetitive sound cells, seems to be important. Similarly to the unistic painting, there is a simple, yet logical relationship here: the shorter section of time the given cell fills, the greater the frequency of returns and therefore the stronger unification of the course. And, finally, another significant element is the structural aspect of the originally given sound cells, which, in Krauze’s works, similar to the cells that make up Strzemiński’s painting, acquire the rank of constitutive units. The composer ensures the structural legibility of the sound systems that form the cell, providing it with an easily perceptible structural specification that has a significant impact on the process of perceiving and fixing musical qualities in a composition directed by the unistic concept.

We can therefore finally state that the impact of unism in terms of structural microparticles was decisive for the following:

- limiting the size of the construction units to the size of the elementary cells of the form (motif or phrase),

- peculiarities of the structural image of the structural unit, which are usually characterised by a deliberate simplicity or even poverty of sound form (see the examples of music notation below).

3.5. Macrostructural Level

The creation of a model of musical unistic form, as homogeneous as possible, drew the composer’s attention to such means of construction that, without producing results contrary to the overarching idea, ensure the continuity of the musical process. In the course of penetrating the various technical possibilities, specific principles for the internal organisation of the work were established, among which the following seem to be crucial:

- reduction of the principle of diversity,

- repetition (albeit generally non-literal) and the resulting rule of the presence of the constans element of musical construction,

- the principle of non-contrasting, “unidirectional” composition of the form.

Reduction of the principle of varietas manifests itself in a quantitative reduction of construction ideas. Hence, the typically unistic piano compositions usually operate with a single sound idea that has a form of creative significance.

In Krauze’s works, the repetition of sound ideas provided at the beginning of the piece becomes the musical equivalent of the process of building up the surface of the unistic painting by identical graphic cells. However, the repetition of sound elements takes on a rather sophisticated form in the piano pieces. The composer generally avoids simple, literal repetitions of the pattern in favour of its modified versions. It should be noted, however, that this pattern is often a sound idea that is used to build only one plane of musical construction, while at the same time another plane exploits a different pattern. However, the two planes, coexisting invariably from the beginning to the end of the work, ultimately realise the idea of homogenetic form.

The rule of the presence of a fixed element, associated with repetition, is an important factor that unifies the sound structure of the entire work. It relates to many aspects of the organisation of the work, taking a variety of forms, including the following:

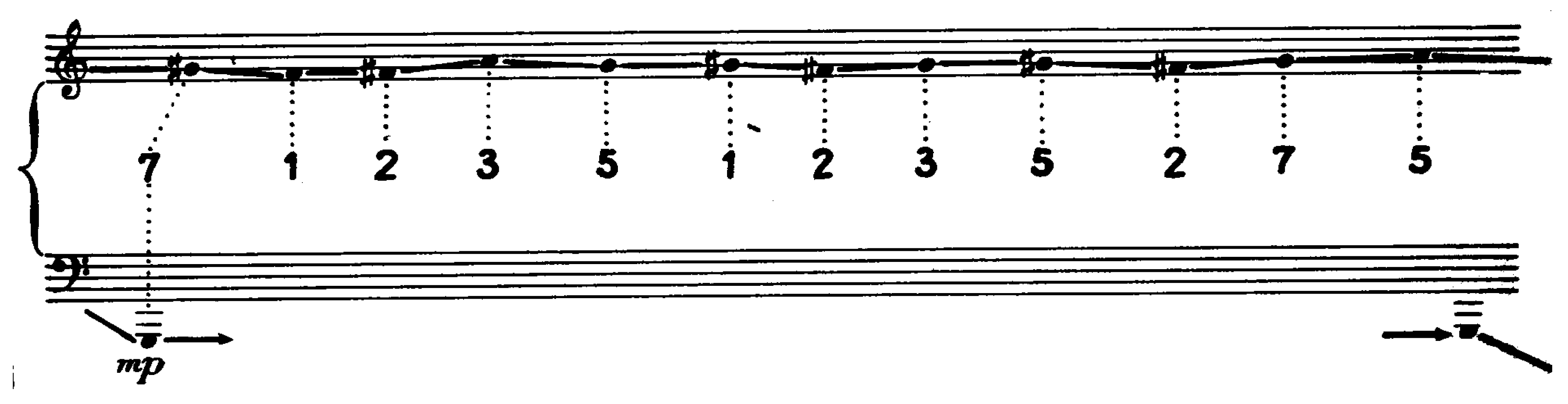

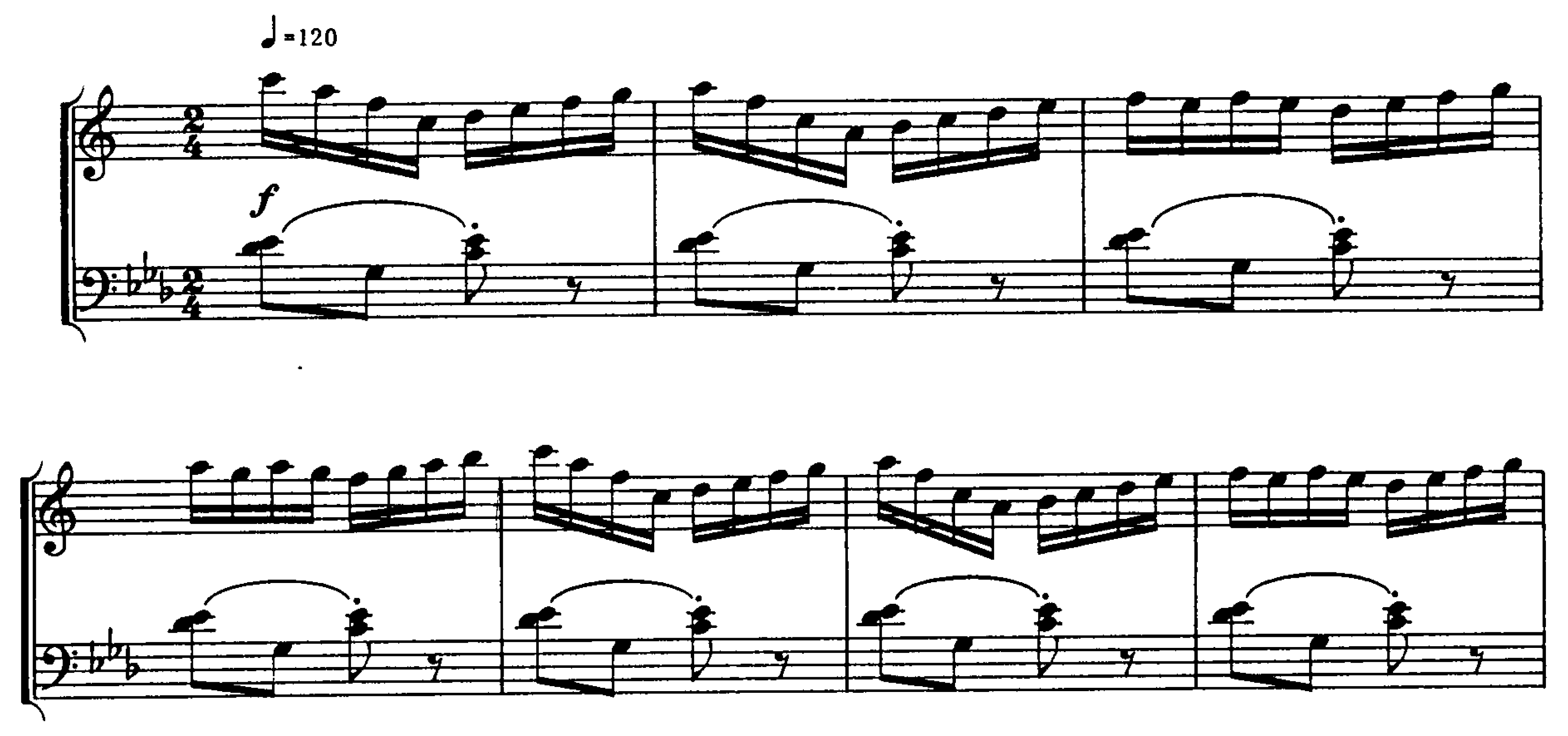

- fixed, absolute pitches that form a kind of mini-scale (as in the first of the Five Unistic Compositions, in which the composer in the right-hand plane does not go beyond a selected circle of several pitch classes in the major third F-a, forming a linear sequence of characteristic second motifs throughout the miniature (Figure 3),

Figure 3. Zygmunt Krauze, Five Unistic Compositions (1963), Composition I. Reproduced with permission of the PWM Kraków.

Figure 3. Zygmunt Krauze, Five Unistic Compositions (1963), Composition I. Reproduced with permission of the PWM Kraków. - fixed interval classes (having chosen specific intervals, the composer generally remains faithful to them throughout the work. It is significant that in many pieces the composer likes to use intervals: thirds and seconds of both sizes, arranged in horizontal or vertical constellations (Figure 4),

Figure 4. Zygmunt Krauze, Five Unistic Compositions (1963), Composition III. Reproduced with permission of the PWM Kraków.

Figure 4. Zygmunt Krauze, Five Unistic Compositions (1963), Composition III. Reproduced with permission of the PWM Kraków. - a fixed sound motif (Figure 5),

Figure 5. Zygmunt Krauze, Fünf Klavierstücke (1958), Klavierstück V. Reproduced with permission of the PWM Kraków.

Figure 5. Zygmunt Krauze, Fünf Klavierstücke (1958), Klavierstück V. Reproduced with permission of the PWM Kraków. - a fixed rhythmic pattern (with a variation in the form of the homogeneous rhythmic pattern that usually shapes the course of the entire work (Figure 5),

- permanent register (Figure 5),

- fixed articulation (Figure 5),

- constant dynamic level (Figure 5).

The aforementioned elements (which are often combined with one another) usually apply throughout the work, either relating to one of the planes of the musical course (as, for example, in the first of the Five Unistic Compositions) or taking part in the formation of the sound construction understood as a whole (as, for example, in Klavierstück V of the Fünf Klavierstücke).

From the point of view of the unistic conception of the work, the characteristic, non-contrastive and “unidirectional” (to use the composer’s term) manner of composing the form is a feature of fundamental importance. It can—as it seems—be seen as an expression of opposition to traditional contrastive juxtapositions and the musical tensions that they bring. The composer says, “[…] [a]ll the changes and movements necessary to maintain the continuity of the music are not contrasted. […] All that the listener will discovers in the first few seconds of the performance of the piece will last until the end. […] There will be no surprises” (Krauze 1993).

This non-contrastive “unidirectionality” of the musical process revealed at the level of the formans form, i.e., the emerging work, is expressed by the desire for gradual change, for discrete, unidirectional modification of the course. The composer pursues this intention through a variety of technical means, which, in the piano works, are dominated by the following:

- the unidirectional progression of sound figures (motifs) up or down the sound field (resulting in a progressively higher or lower register of the instrument (Figure 6 and Figure 7),

Figure 6. Zygmunt Krauze, Five Unistic Compositions (1963), Composition V, fragment. Reproduced with permission of the PWM Kraków.

Figure 6. Zygmunt Krauze, Five Unistic Compositions (1963), Composition V, fragment. Reproduced with permission of the PWM Kraków. Figure 7. Zygmunt Krauze, Preludium—Intermezzo—Postludium (1958), Preludium, b. 1–24. Reproduced with permission of the PWM Kraków.

Figure 7. Zygmunt Krauze, Preludium—Intermezzo—Postludium (1958), Preludium, b. 1–24. Reproduced with permission of the PWM Kraków. - the unidirectional expansion or reduction of a motif, phrase, or sentence resulting from the gradual addition or subtraction of the elements that make up a given sound cell (Figure 6, Figure 7 and Figure 8),

Figure 8. Zygmunt Krauze, Preludium—Intermezzo—Postludium (1958), Intermezzo, b. 1–13. Reproduced with permission of the PWM Kraków.

Figure 8. Zygmunt Krauze, Preludium—Intermezzo—Postludium (1958), Intermezzo, b. 1–13. Reproduced with permission of the PWM Kraków. - unidirectionality of dynamic changes (Figure 6, where the dynamics are shaped gradually from ppp to fff).

Textural operations played a significant role in the search for a unistic formula of sound; their linearity was the overriding category of instrumental texture in the Krauze’s work. The vertical aspect, on the other hand, conceived as a determinant of harmony, remains outside the composer’s focus and exists rather as a resultant of simultaneous linear constructions. However, striving for maximum unification of sound determined the strong integration of co-existing (horizontally conceived) sound planes, which is evident in, for example, the following:

- unison or quasi-unison courses (Figure 7),

- rhythmic unification of voices, which are, however, differentiated in terms of pitch (Figure 6),

- the close positioning of voices in the instrument’s sound field, which helps to reduce their timbral selectivity (Figure 6),

- the motivational dependence of voices (Figure 9),

Figure 9. Zygmunt Krauze, Fünf Klavierstücke (1958), Klavierstück II, whole. Reproduced with permission of the PWM Kraków.

Figure 9. Zygmunt Krauze, Fünf Klavierstücke (1958), Klavierstück II, whole. Reproduced with permission of the PWM Kraków. - the synthesis of the sonic components of a motif or an entire phrase into a sonic monolith by means of the “stopped” sounds technique (Figure 10).

Figure 10. Five Unistic Compositions (1963), Composition IV, fragment. Reproduced with permission of the PWM Kraków.

Figure 10. Five Unistic Compositions (1963), Composition IV, fragment. Reproduced with permission of the PWM Kraków.

By combining the aforementioned technical procedures on several occasions, the composer enhances the impression of a sonic homogeneity of a somewhat naturally simplified form. However, it is worth noting that

[…] the simple form of Krauze’s music does not hide simple music. Its hushing and asceticism, which do not entail expressive recession and are no example for the exuberance of life in the element of music, by no means deny this life10.(Droba 1973)

3.6. The Unistic Concept and the Problem of Form, Time, and Perception of the Work

Observations made at the level of the technology of the work seem to confirm that unistic theory gave rise to a rather radical break with the traditional model of musical form, which is dialectical in its essence.11 Aiming for a uniform “intensity” of the form, the composer avoids the juxtaposition of opposing qualities that, as in a painting of dualistic shapes, make the parameter of time in the work a finite element. The unistic form overcomes and even abolishes the impression of finitude, becoming a symbol of duration without beginning or end. The composer expresses that idea in a musical form devoid of an introduction and an ending. In his idea, what is currently resounding is a sonically marked particle of time (conceived as limitlessness and infinity) and a sample of the form that fills this time with an unchanging pattern. In Krauze’s terms, therefore, the work reaches the ontological category defined by the notion of eternity. There is some convergence here with Stockhausen’s concept of moment form. This convergence, however, reveals itself primarily on the basis of a related philosophy and an innovative vision of the understanding of the temporal aspect of musical form derived from it, which results in a different approach by the two composers to the problem of the perception of a musical work. As Stockhausen reveals, in the genesis of moment forms,

[…] I tried to compose states and processes in which each moment is […] something that can exist for itself, [….] in which all events do not begin their determined course from a fixed beginning to an inevitable end (the moment need not be the pure succession of something preceding and the cause of what will follow, and thus a particle of measured duration), but in which concentration on the Now—on each Now—makes, as it were, vertical cuts, penetrating across the horizontal imaginary of time until its abolition, which I call eternity: an eternity that does not begin at the end of time, but is attainable at every moment.(Skowron 1989)

According to Z. Skowron,

the idea of moment form is to abolish the determined, cause-and-effect succession of sounds, which creates a flow of closely related and mutually contingent events. The composer wants to achieve the independence of separate wholes—moments—and make them equally valid objects of perception. […] These moments [as a result of the specific proposal of reception], freed from interconnection, are suspended in time and stopped, as it were, in their continuance.(Skowron 1989)

At the same time, Stockhausen makes a peculiar distinction and a certain decoupling of the “two” inherently parallel co-existing times: the time marked by the artistic realisation of the work and the time of its auditory perception. For the piece can continue indefinitely, but the listener is free: they can break free from the music and return to it at any time. In Krauze’s approach, on the other hand, the “two times” overlap closely—one would like to say they coexist in parallel in a traditional way. Conceived as a particle of infinite being, the piece realistically lasts a short time, and it is necessary to enter into active contact with it because only at the moment of perception does the perceptor have the chance to experience the potentially infinite dimensions of time and form. What both composers have in common, however, is a focus on the present, on experiencing the moment, except that with Stockhausen, the moment is chosen by the listener, while with Krauze, in his unistic works, the “now” is what resounds in the given moment. In addition, the perceptual process is characterised by the considerable predictability of musical events assumed by the composer, resulting from the idea of unism. The composer does not intend to attack the listener with unexpected clashes of oppositional musical qualities; he allows the gradual formation of the work’s form to be traced, while at the same time ensuring that the listener’s expectations are met:

[…] I prefer to enable the viewer to listen to individual details and fragments of music. […] because getting to know this music is easy, so they know what they may encounter. They also know that if a passage has disappeared for a while, it is bound to return. This music involves the possibility of a different kind of reception. The ideal situation would be one in which the music would go on continuously and the listener would come at a time that was convenient for them and leave when they want12.(Krauze 1970; quoted in Szwajgier 1996)

3.7. Links to Minimal Music

At the same time, the idea of the unistic form of the musical work is to some extent related to the assumptions of minimal music, especially—as it seems—in the approach represented by Steve Reich, who, according to Grünzweig, advocates a way of shaping the musical process that, without exhibiting a state of stillness, follows a predetermined course. Reich’s approach is characterised not only by an innovative vision of the musical process but also by specific requirements for its perception. Similarly to Krauze’s compositions, in Reich’s work these two musical categories (the musical process and its perception) are largely dependent on each other. For the organisation of the work should enable acoustically hearing and easily perceiving the creation of the work in the reception process. To illustrate this a priori assumption, the composer has used the analogy of a swing (pendulum) which, once set in motion, moves automatically until it reaches a state of complete motionlessness (Grünzweig 1997). This concept undoubtedly determined Reich’s minimalist treatment of the means of artistic expression to a significant degree. Let us note, by the way, that the composer’s inherent understanding of the musical process as a gradational process, realised in a particularly expressive way in his Pendulum Music (1968), was preceded by Ligeti, who used 100 metronomes for his Symphonic Poem (1962) (Skowron 1995). They were regulated for different tempos, set in motion and left without further interference until what can be described as a state of rest (Grünzweig). Above all, however, if we compare the dates of composition of the works that are representative of the musical phenomena under discussion, Krauze’s concept—although not supported, as in the case of Reich, by a broad theoretical reflection, but by the musical work itself—seems to be the earliest (as his first unist compositions were written in 1957 and, interestingly, they were piano pieces). This observation seems to confirm the thesis of Krauze’s independence from the influence of the New York minimalist ideas. Moreover, Krauze’s unquestionable minimalist inclinations, so evident in his piano works, seem to be linked to the assumptions of unism derived from painting, which, from the perspective of seven decades, lend themselves to certain comparisons and allow them to be put into a broader context.

4. Giacometti—Skrzypczak

4.1. Four Sculptures by Alberto Giacometti Versus Four Figuren by Bettina Skrzypczak

The work representing the visual arts, which was a source of inspiration for Bettina Skrzypczak, turned out to be a constellation of four bronze sculptures by Alberto Giacometti exhibited at the Museum der Fondation Beyeler in Riehen, Switzerland (Scheme 5).

Scheme 5.

Installation view Northern Lights, Fondation Beyeler13, Riehen/Basel, 2025. Photo: Robert Bayer. Reproduced with permission of the Museum der Fondation Beyeler.

By undertaking a musical interpretation of Giacometti’s work, the composer initiated a process of transmedialisation, involving the transformation of a visual message into a musical one. The composer intended that the musical composition thus become a representation of the visual composition, reflecting the content of the visual object in the audio medium. This fully aligns with the concept of ekphrasis proposed by Siglind Bruhn, although, it should be noted, Bettina Skrzypczak does not confirm inspiration from such theories. However, she does not dismiss the possibility of the influence of the Romantic idea of correspondance des arts…

The photograph presented here shows four sculptures forming a compositional whole. They were created between 1958 and 196014.

The artist gave the sculptures, counterparts of human figures, verbal identifiers:

Attention is drawn to the ambivalent structural features of the sculptures. On the one hand, one is struck by the ascetic nakedness and fragility of the slender figures, on the other by the exaggerated, disproportionate size and massiveness of the feet firmly fixed to the ground, or the surreal height of the Tall Women. The expressive power of the sculptures is also encoded in the characteristics of their surfaces—rough, coarse, and in the duality of their contrasting states—a dynamic state exposing the element of movement (Walking) and a static one (Tall Women remaining majestically still). The way the sculptures are arranged in the space is also an element that has a significant impact on the perceptor19. It allows, among other things, an interpretation of the role of one of the sculptures—the bust (Large Head)—as a recipient/observer of the situation created by the other three sculptures: Walking Man II and two statues of Tall Women.

In B. Skrzypczak’s account concerning her reaction to Giacometti’s work we read:

In my direct perception of the work, I was particularly interested in the spatial solutions (the shape of the sculptures, their positioning in space), as well as the way in which the details were shaped, especially the surfaces of the sculptures. […] Strict in their expression like the statues of ancient Egypt, they spread around a mysterious aura and attract attention with their unique form. […] The man in motion symbolises the present, the figures of the two women, through their static character, emanate an aura of timelessness. The monumental Large Head—the observer—maintains a distance from the other figures and represents a dimension of human history. At the same time, as a group, as a composition, they create a network of connections in the space surrounding them that are extremely concentrated.20

The composer’s commentary, interpreting Giacometti’s work, is reflected in the musical organisation of Vier Figuren, translating (transforming) Giacometti’s sculptural composition into the language of musical composition. Let us trace these relationships—captured in the musical arrangement of the references to A. Giacometti’s work.

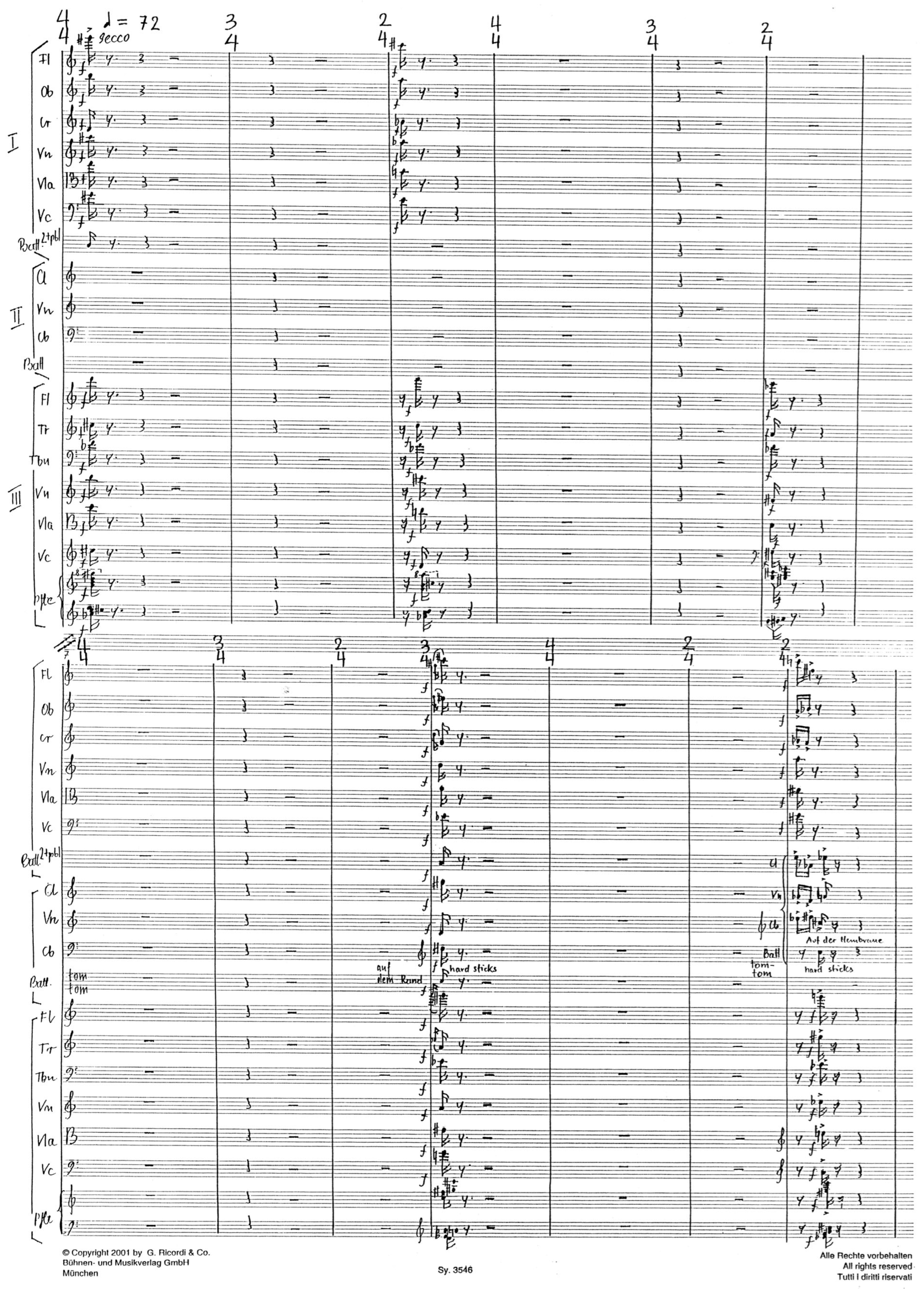

4.2. The Cast and Its Arrangement in the Performance Space

In Bettina Skrzypczak’s interpretation, the Large Head (the observer) assumes the role of the audience; therefore, only the three remaining sculptures by Giacometti are assigned three instrumental groups, appropriately arranged in the space made:

- Group I: Fl, Ob, Cr, Vn, Vla, Vc (equivalent to The Tall Woman III)

- Group II (middle): Cl in B, Vn, Cb, Batteria (equivalent to The Walking Man II)

- Group III: Fl, Tr, Tbn, Vn, Vla, Vc, Pfte (equivalent to The Tall Woman IV)

Please note that the outer groups (I and III) were “more strongly” staffed than group II (inner). However, this apparent weakness of the cast is compensated for by the addition of percussion instruments to group II (piatti, bongos, congas, tom-toms, tam tam-grande, glass chimes, triangle). The inclusion of batteries emphasises the dynamic movement inherent in the figure of The Walking Man II. According to the composer’s intention, the instrumental groups should remain at a certain distance on the stage, with the proviso, however, that in the places of the tutti, an effect of coherence of sound is possible—just as the arrangement of Giacometti’s figures in the architectural space of the Museum displays the characteristics of coherence, making it possible to capture the spatial compositional whole from different perspectives. Groups of instruments create a physical and musical space within which a network of different relationships is possible.

This means that the cast proposed by the composer, as well as the way in which the individual groups of instruments are arranged, makes it possible, on the one hand, to create spatial and timbre contrasts between the blocks/groups of instruments understood as a whole and, on the other hand makes it possible to create “coherent second-order casts”21, allowing the achievement of a different kind of spatial effect by operating only with homogenous instruments, common for particular groups: strings or winds selected from each group22. This is conducive to exposing the multidimensionality of the space. From this perspective, the presence of the violin in all the groups can be interpreted as a symbol of unifying communication between the sculptures. The fact that the extreme groups contain the most common instruments can be interpreted as a metaphor for defining the boundaries of space within which there is a flexible (“stretchable”) body, whose shape is subject to transformation over time.

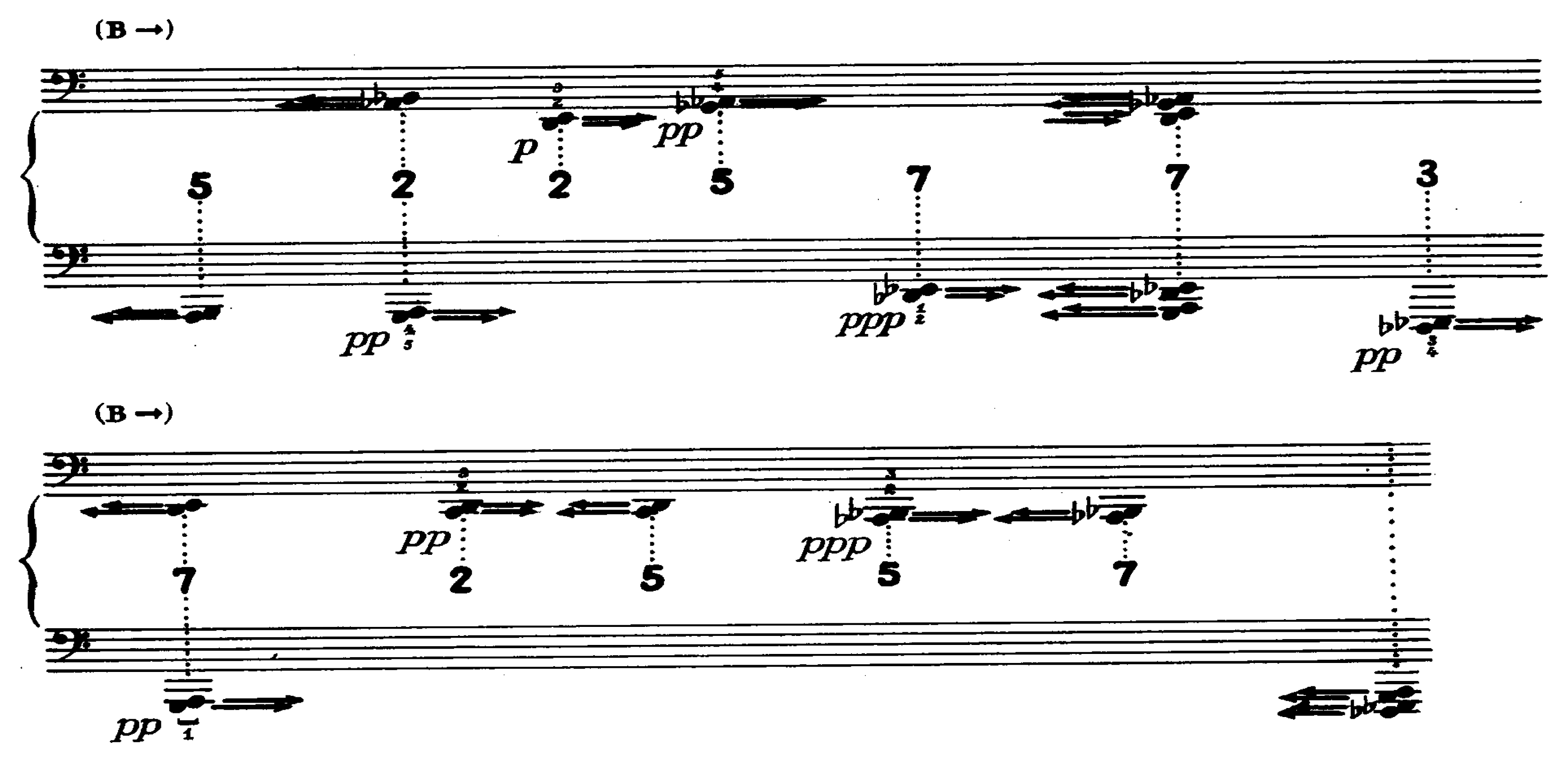

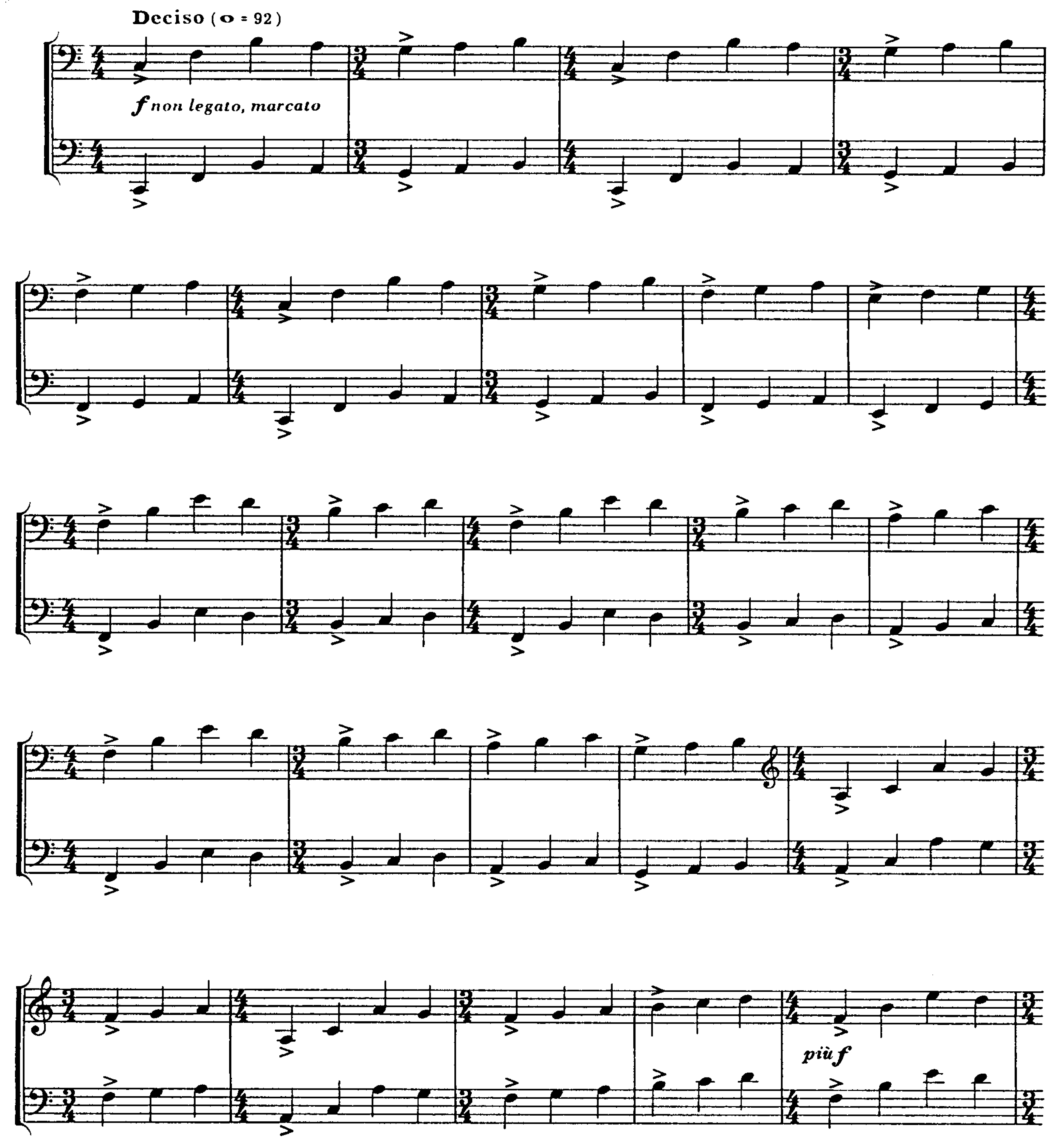

4.3. Textural Depictions of Instrumental Groups as a Musical Interpretation/Representation of the Relationships Between Sculptures

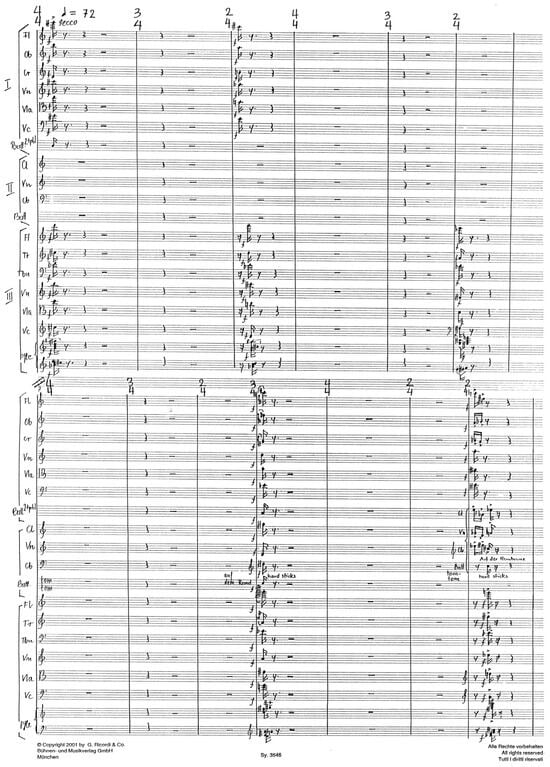

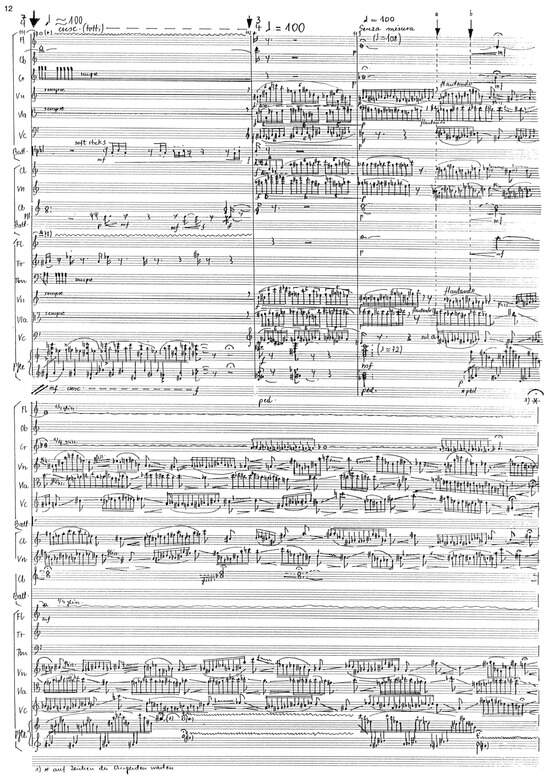

Variously shaped layered structures that are a synthesis of individual instrumental groups, each of which, while representing a distinct Giacometti figure, is simultaneously in relationship with the others. These relations, musically “enlivened” by B. Skrzypczak, can be perceived by the listener as a process of transformation taking place in the course of the piece, equivalent to the discovery of new points of view, new perspectives of viewing the sculptures, which give the relations between them ever new aspects, showing them in new light (see Figure 11, Figure 12, Figure 13 and Figure 14).

Figure 11.

Bettina Skrzypczak, Vier Figuren, the beginning of the work—the briefly articulated chords maintained in forte dynamics (score, p. 1). Reproduced from composer’s manuscript [with the composer’s permission].

Figure 12.

Bettina Skrzypczak, Vier Figuren—“Porous surface”, the so-called “moving cells” undergoing various transformations (score, p. 12). Reproduced from composer’s manuscript [with the composer’s permission].

Figure 13.

Bettina Skrzypczak, Vier Figuren, the ending of the work—the briefly articulated chords (score, p. 48). Reproduced from composer’s manuscript [with the composer’s permission].

Figure 14.

Bettina Skrzypczak, Vier Figuren—a quasi-“murmur” setting (score, p. 31). Reproduced from composer’s manuscript [with the composer’s permission].

4.4. Form of the Work: Elements of the Microform and Their Role in the Context of the Macroform

The form of the composition of Vier Figuren does not yield to the models and patterns known from tradition. On the one hand, its segmental nature, marked by fluctuating tensions and relaxations, draws attention; on the other hand is the clear coherence of the whole. One of the important means contributing to the impression of coherence of form are the briefly articulated chords, maintained in forte dynamics, which initiate the piece and later appear repeatedly but in different textural situations than at the beginning (see Figure 11 and Figure 13). Their main task is, on the one hand, to substantially integrate the form, and from the perspective of psychological strategies for controlling the listener’s perception, they are to mobilise and concentrate the listener’s attention at various stages of the musical progression.

The nature of Giacometti’s sculptures, which attract attention with detail and specific surface structure, also results from the composer’s ways of operating at the level of microform. The equivalent of this feature in Bettina Skrzypczak’s composition is the so-called “moving cells” undergoing various transformations. They influence the processual character of the transformation of the sound tissue, which can be read as an equivalent of the implied interactions between the figures of the sculptural composition (see Figure 12 ‘Porous surface’).

4.5. Dramaturgy

Giacometti’s sculptures weave a story—an individual, separate story, but also a group or social story. This narrative can be interpreted as the result of perception, both optical and acoustic, of a divided space, cut through, as it were, by sculptural objects (figures, sculptures) which, as a result of their constellation, trigger states of strong dramatic tension.

The very beginning of the work becomes an important expression of this. The impression of space being cut apart by the elongated figures of the sculptures led the composer to adequately design the first bars of the piece (which are the musical equivalent of the impression B. Skrzypczak had during her first contact with Giacometti’s sculptures). We hear the previously mentioned short-sounding chords separated by moments of silence (long pauses). This is an analogy to the way space is used in Giacometti’s composition—the pauses between chords are a musical representation of the distance between spaced figures. However, they are by no means an empty space. An attentive recipient will easily perceive the complex web of relationships between the characters manifesting their presence in specific ways (cf. in the score of the work bars 1–18, Figure 11, beginning of the work, score, p. 1).

Looking at the same arrangement of sculptures from a different perspective triggered in the composer’s imagination their variable sound forms in relation to the projection of the short/sharply articulated chords that initiated the piece. As hinted at earlier, the short chordal impulses that recur repeatedly in the piece gain a new context. With the successive returns of the chords, the composer filled the silence (pauses) between them with musical events that were not originally present, as a result of which the initial power sforzato of the chords, this time absorbed by a complex network of textural links, loses its suggestiveness and is gradually levelled. This technique suggests a musical representation of Giacometti’s figures/characters, whose contours gradually blur and lose their physical literalness—the sphere of externality is transformed in favour of a perception directed inwards (cf. e.g., t. 214–233 in the work’s score, where sharp-sounding chords appear in a quasi-“murmur” setting, see Figure 14, score, p. 31).

4.6. The Process of Creating Vier Figuren by Bettina Skrzypczak

The composer informs us that the creation of the “Four Figures” took place in several phases, with the composing–writing phase preceded by a rather long process that could be called “familiarisation” or voluntary “immersion” in the world of Alberto Giacometti’s vision. It was a period of fascination with the object of cognition—getting to know both his thoughts through the study of his writings, his statements, and also comments on the artist and his work (painting and sculpture).

This first phase was conducive to confronting Giacometti’s perception of the reality of the world and of art with the observations and views of B. Skrzypczak. Her particular attention was drawn to Giacometti’s statement revealing a perspective of seeing the relationship between the detail and the larger elements of a given whole:

Every day the world amazes me more and more. It’s getting bigger and bigger, it’s getting more wonderful, more incomprehensible, more beautiful. I am delighted with every single detail, Like an eye on someone’s face, or moss on a tree. But not more than (the world as) a whole; How can we tell the difference between the detail and the whole? It is the details that contribute to the creation of the whole, they influence the beauty of the form.(Giacometti 1999)23

Just consider the sculpture of the Large Head. It is the detail (the detailed dimension)—the porosity of its surface—that attracts the recipient’s attention in a particular way—and this characteristic, involuntarily, forces one to concentrate on the detail, while at the same time suggesting the complexity of the form understood as a whole.

The composer describes Phase II of the process of creating the work as the reflection phase. As she recalls, “it was a time of communing with the artist’s work”. In this statement by Bettina Skrzypczak, the phenomenological approach comes to the fore, with its fundamental rule “Zurück zu den Sachen”, which the composer meticulously fulfilled, “During the many hours spent in the hall of the Fondation Beyeler museum24 in <the company of Giacometti’s sculptures>, I had the impression of communing with living beings, which became increasingly close to me, and I felt the weight of the content they convey.” Phenomenological “one-on-one” contact with Giacometti’s work established the artist in the sphere of her own concept of interpreting the composition of sculptures using the means of musical language.

From this moment on, the composer marks Phase III of the process of creating the work Vier Figuren—the phase of transforming Giacometti’s message into the composer’s vision of the work. “At this stage”, the composer confesses, “I tackled the arrangement of instruments in space, their unconventional grouping, as well as the issue of the work’s form and micro-structural solutions.” At the same time, in this phase, the artist began to be intensely concerned with the problem of the perception of the work in a double sense: the perception of Giacometti’s sculptures and the reception by the recipient of the musical composition, which is a specific representation of Giacometti’s work.

Therefore, the fourth phase of the composition process is increased interest in the acoustic realisation of the composition during the premiere. There were also other questions that concerned the composer: To what extent is Giacometti’s vision made present in the sound–spatial form of the musical work? To what extent can the relationship between the source of inspiration and its musical imagery, its musical representation, be clear to a recipient familiar with Giacometti’s work? However, these questions remain unanswered…

Each medium of art expresses reality through its own point of view [recalls B. Skrzypczak]. What they have in common is what they refer to. I think that the period in which my thoughts revolved so intensely around the theme of Giacometti’s chosen four figures had an additional, broader dimension: while sympathising with Giacometti’s attitude, I also presented my own vision, the essence of which is to confront what, in fact, always remains inexpressible. With the mystery that lies within us.25

Bettina Skrzypczak’s composition Vier Figuren was dedicated to the well-known Swiss patron of contemporary art, founder of the Museum and Fondation Beyeler in Riehen Ernst Beyeler (1921–2010) in connection with the 80th anniversary of his birthday.

The premiere of the work took place at the Beyeler Foundation Museum in Riehen on 19 November 2001, performed by the Ensemble der Basler Orchestergesellschaft and conducted by Jürg Henneberger. The piece was also performed in 2005 at the “Warsaw Autumn” International Festival of Contemporary Music.

5. Conclusions

In creating the musical layer of the works presented, the composers concentrated on musically “capturing” the essential qualities of the source of inspiration, qualities that relate to the main idea, to the emotional sphere, the mood, or even the structural value of the visual object. Can it be assumed that the works presented are musical ekphrasis or, to adapt a term proposed by Siglind Bruhn (Malecka 2006), a transmedialisation of visual representation? It seems that we can fully endorse an affirmative answer—in the sense of each composer’s specific response to a source of inspiration, a response understood as an expression of a resonance experienced, a particular emotion, a fascination with a visual object. Through his own actions in the field of music, the composer strives for full fusion with the ideological–aesthetic “meaning” of the visual object; one could say that inspiration transforms into transmedialisation; this, in turn, presupposes the existence of a convergence of visual and auditory impressions, and here, such impressions undoubtedly occur (unambiguously in the case of Krauze and Bargielski’s compositions, and at a higher level of abstraction in the case of Bettina Skrzypczak’s work). Their verification could be fostered by the situation of functioning in a common space of reception—as a whole, equipped with a set of immanent features … On the other hand, music represents an intrinsic value and can also be perceived at the level of immanent stylistic and aesthetic, or even supra-aesthetic, features, which in the presented compositions are defined by a set of means belonging to the musical language of each of the creators.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Polish composer acting temporarily in Austria (1967–2002). Z. Bargielski has dual citizenship—Polish and Austrian. |

| 2 | This composition is a combination of recordings of two works composed nearly 25 years apart. The earlier piece Tal der bleichen Knochen (1977) refers in the sphere of inspiration to events described in the Old Testament and therefore to a source of inspiration other than that represented by the visual arts, while the correlated piece is Towards Organic Geometry—presented in this article and inspired by the graphic idea of Tadeusz Mysłowski. |

| 3 | There only exists an audio recording of the composition. |

| 4 | The sound of the instruments listed in the draft was produced electronically. |

| 5 | Taken into consideration how extensive is literature dedicated to this subject, only the basic designations of unism in painting will be recalled here—those that clearly correspond to Krauze’s music and are verified in its sonic organisation. |

| 6 | The composer says ‘[…] for many years, I was an adherent of the unistic form, inspired by the painting and theory of Władysław Strzemiński’ (quoted in Młynarczyk 1998, p. 4). |

| 7 | In an interview conducted by K. Tarnawska-Kaczorowska, the composer reports: ‘[…] My first significant experience was an encounter with the art of Władysław Strzemiński. In a sort of a way, he set the course for my actions, my thinking and my music’ (quoted in Tarnawska-Kaczorowska 1998a, p. 34). |

| 8 | Its importance is also indicated by the fact that many of his compositions were published and were repeatedly performed at significant festivals and concerts in Poland and around the world. Some of the works were also recorded. |

| 9 | The musical form of unism in the work of Zygmunt Krauze aroused quite lively interest among analysts of the 20th-century Polish music, which is proved by a relatively long list of dedicated publications. Several of them convey, often through the form of an interview, the reflections of the composer himself (for example: Tarnawska-Kaczorowska 1998a, 1998b; Młynarczyk 1998; Grzenkowicz 1987; Kaczyński 1977). Another important source of information about unism are the composer’s statements included in concert programmes in the form of self-commentaries to the works performed, in which Krauze often reveals the secrets of his own musical thinking, guiding the way the work should be experienced (e.g., Programme Book of the Warsaw Autumn Festival 1967, Programme Book of the Warsaw Autumn Festival 1991). Among the theoretical studies, we can point out a valuable introduction to the poetics of musical unism: Szwajgier’s (1996) study Unistyczna twórczość Z. Krauzego [Z. Krauze’s Unistic Works]. Its author attempted to exemplify the most essential assumptions of the unistic concept. The issue of unism as a differentia specifica of Krauze’s oeuvre, as well as his piano music considered as an area of composition that the artist particularly liked, is also highlighted in the encyclopaedic article by Szczepańska (1997). Another study worth attention is Nowak’s (1997), Współczesny koncert polski [Contemporary Polish Concert] (op. cit), in which the phenomenon of unism is raised in the context of the form of the contemporary Polish concert. Moreover, Krauze’s oeuvre was the subject of a monographic study by Tarnawska-Kaczorowska (2001): Zygmunt Krauze. Między intelektem, fantazją, powinnością i zabawą [Zygmunt Krauze. Between Intellect, Imagination, Duty and Fun]. Tarnawska-Kaczorowska’s presentation of unistic piano works does not focus on verifying the assumptions of unism in the sonic organisation of these works. Therefore, it seems that the analytical insights contained in this article complement K. Tarnawska-Kaczorowska’s perspective in their own way. The issue of Krauze’s unism (apart from his piano works) in the context of the Polish branch of the minimal music movement was also raised by J. Miklaszewska in her 2003 work Minimalizm w muzyce polskiej [Minimalism in the Polish Music]. |

| 10 | This view was formulated by Droba influenced by the Krauze’s unistic piece Aus aller Welt stammende. It seems that the remarkable accuracy and universality of the quoted formulation, in which the author captured the essence of the expressive qualities of musical unism, allows this view to be applied to all the unist compositions of Krauze, including his piano pieces. |

| 11 | It seems necessary here to note that the unistic character of the form is exhibited by the abstracted and autonomously perceived piano miniatures. Meanwhile, the composer combined many of these small works into collections, in which the manner of juxtaposing the compositions not only seems non-random, but reveals features of a traditionally conceived cyclicality, in which the principle of contrast and the distribution of tensions shape a conventional type of dramaturgy based on a directed pursuit of a goal (e.g., in the Five Unistic Compositions, there is a principle of contrast between the miniatures of the set, as if segments of a cycle, while the last miniature—of a clearly final nature—culminates the cycle). Some links to the traditional model of musical form in the work of Z. Krauze were also highlighted by T. Kaczyński. When characterising the form of the String Quartet No. 1, he wrote: ‘[…] If he was thinking about form it was certainly not one big course, but many small ones. This is because the entire piece is built up of short sections, which act here as a kind of formal unit. Each such section is filled with a specific directional movement, brought at the end of a given section to its end stage, which can no longer be continued. […] A pause follows, which is not, however, a closure of the section in question, but rather a sort of extension, a silent continuation […]. After the pause, the same movement is taken up in a different way; so different that we can actually call it the next section, the next formal unit […] nevertheless, the work as a whole has a reprise form […].’ (Kaczyński 1965, p. 10). |

| 12 | It is worth mentioning that the composer concretised this idea in his Spatial-Musical Composition No 1 (1968), ‘[…] which he realised in the specially constructed six rooms of the Contemporary Gallery in Warsaw. Twelve loudspeakers were placed there, from which music was continuously emitted; it was different in each room; the listener, choosing their own way through the “labyrinth” and staying in each room for any length of time, shaped the final piece themselves’ (Szczepańska 1997, p. 193). |

| 13 | Fondation Beyeler is the name of a foundation promoting contemporary art, founded by Ernst Beyeler, a well-known art connoisseur. |

| 14 | Including a period of ‘pre-composition’, from 1958, involving the creation of figures in the form of plaster miniatures. |

| 15 | Grande tête, 1960, Bronze, 94.6 × 30.9 × 34.7 cm. |

| 16 | L’homme qui marche II, 1960, Bronze, 188.5 × 29.1 × 111.2 cm. |

| 17 | Grande femme III, 1960, Bronze, 235.8 × 32.3 × 54.0 cm. |

| 18 | Grande femme IV, 1960, Bronze, 269.0 × 33.0 × 57.5 cm. |

| 19 | This is one of the versions of the composition/constellation of sculptures in space—the one seen by the composer at the Riehen Museum. |

| 20 | From the composer’s private notes made available to the author of the article. |

| 21 | Second-order casts—the composer’s term. |

| 22 | For example, 2 flutes in the extreme groups, Vn, Vla, Vc—in three, i.e., in all groups (e.g., in the score Senza misura strings—p. 7, winds—p. 3, t. 30). |

| 23 | Transl. to Polish by Bettina Skrzypczak. |

| 24 | Bettina Skrzypczak admired the four sculptures by A. Giacometti on display at the museum of contemporary art established by the Fondation Beyeler in Riehen, i.e., in the town of her residence in Switzerland near Basel. |

| 25 | Note by B. Skrzypczak from the period of the creation of the work. |

References

- Bargielski, Zbigniew. 2011. [Commentary in] Mysłowski [Brochure]. Lublin: Muzeum Narodowe w Lublinie, p. 27. [Google Scholar]

- Bojko, Szymon. 2011. [Commentary in] Mysłowski [Brochure]. Lublin: Muzeum Narodowe w Lublinie, p. 40. [Google Scholar]

- Bruhn, Siglind. 2001. Musical Ekphrasis. Paper presented at Session in Seventh International Congress on Musical Signification Music and Arts, Imatra, Finland, June 7–10; Abstract. p. 10. [Google Scholar]

- Droba, Krzysztof. 1973. Mieszane uczucia po XVII Warszawskiej Jesieni. Odra 12: 107–8. [Google Scholar]

- Giacometti, Alberto. 1999. Gestern, Flugsand Schriften. Zürich: Scheidegger & Spiess, p. 268. [Google Scholar]

- Grünzweig, Werner. 1997. Minimal music. In Die Musik in Geschichte und Gegenwart. Sachteil 6. Edited by Ludwig Finscher. Kasel and Basel: Barenreiter, pp. 294–301. [Google Scholar]

- Grzenkowicz, Izabella. 1987. Między Wschodem a Zachodem. Ruch Muzyczny 4: 3–4. [Google Scholar]

- Kaczyński, Tadeusz. 1965. Kwartet smyczkowy Zygmunta Krauze. Ruch Muzyczny 17: 10. [Google Scholar]

- Kaczyński, Tadeusz. 1977. Rozmowa z Zygmuntem Krauze. Ruch Muzyczny 19: 6–10. [Google Scholar]

- Karkowski, Czesław, ed. 1999. Pamięć ofiar. Nowy Dziennik, September 24, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Krauze, Zygmunt. 1970. [self-commentary on] Piece for Orchestra No 1. In Programme Book of the Warsaw Autumn Festival [Książka programowa MFMW ‘Warszawska Jesień’]. Warszawa: Warsaw Autumn International Festival of Contemporary Music, p. 13. [Google Scholar]

- Krauze, Zygmunt. 1993. [self-commentary on:] Voices. In Programme Book of the Warsaw Autumn Festival [Książka programowa MFMW ‘Warszawska Jesień’]. Warszawa: Warsaw Autumn International Festival of Contemporary Music, pp. 103–4. [Google Scholar]

- Malecka, Teresa. 2006. Zbigniew Bujarski. Twórczość i Osobowość. Kraków: Academy of Music in Kraków, pp. 165–77. [Google Scholar]

- Młynarczyk, Beata. 1998. Nie tylko o II Koncercie fortepianowym. Dysonanse 2: 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- Nowak, Anna. 1997. Współczesny Koncert Polski. Bydgoszcz: The Feliks Nowowiejski Academy of Music. [Google Scholar]

- Przech, Violetta. 1998. W Stronę Eksperymentu: Sonorystyczne Środki Wykonawcze w Polskiej Twórczości na Fortepian solo II Połowy XX Wieku. Science Notebooks no.10. Bydgoszcz: The Feliks Nowowiejski Academy of Music, pp. 7–23. [Google Scholar]

- Przech, Violetta, and Agnieszka Ledzińska. 2012. Zbigniew Bargielski. Katalog Tematyczny Utworów. Warszawa-Bydgoszcz: The Fryderyk Chopin University of Music, The Feliks Nowowiejski Academy of Music, p. 316. [Google Scholar]

- Skowron, Zbigniew. 1989. Teoria i Estetyka Awangardy Muzycznej Drugiej Połowy XX Wieku. Warszawa: Warsow University, pp. 150–51. [Google Scholar]

- Skowron, Zbigniew. 1995. Nowa Muzyka Amerykańska. Kraków: Musica Iagellonica, p. 365. [Google Scholar]

- Stopczyk, Stanisław Krzysztof. 1988. Malarstwo Polskie. Od Realizmu do Abstrakcjonizmu. Warszawa: Krajowa Agencja Wydawnicza, pp. 133–42. [Google Scholar]

- Strzemiński, Władysław. 1924. Teoretyczny wykład o nowym rozumieniu obrazu. Blok 2. [Google Scholar]

- Strzemiński, Władysław. 1977. Unizm w malarstwie. In Artyści o sztuce. Od van Gogha do Picassa. Edited by E. Grabska and H. Morawska. Warszawa: PWN, pp. 436–55. [Google Scholar]

- Szczepańska, Elżbieta. 1997. Krauze Z. In Encyklopedia Muzyczna PWM. Edited by Elżbieta Dziębowska. Kraków: PWM, vol. 5, [k l ł]. pp. 189–94. [Google Scholar]

- Szerszenowicz, Jacek. 2008. Inspiracje Plastyczne w Muzyce. Łódż: The Grażyna and Kiejstut Bacewicz Academy of Music, p. 25. [Google Scholar]