Abstract

Ceremonial deployed with the aim of displaying and perpetuating power was a shared practice across the medieval Mediterranean. Processions, ceremonies, and ritual acts created solidarity and consensus, naturalized dominion, and conveyed legitimacy while minimizing dissent and threats to social and political hierarchies. Such ceremonial acts were carried out in the public spaces of Mediterranean cities, connecting people, objects, and places in multisensory displays. This paper will explore the relationship between urban spaces and ritual and focus on the architectural contexts where ceremonies and rituals were performed. Three cosmopolitan Mediterranean cities—Cairo, Constantinople, and Venice—will serve as case studies for analyzing how richly ornamented architectural structures were employed as the staging areas for spectacle. Their prominent placement and ornamentation highlighted the theatricality of ceremony and defined a multisensory cityscape that was meant to overwhelm the senses and impress participants and spectators alike.

1. Introduction

Civic ceremonial was a shared practice across the medieval Mediterranean, deployed with the aim of performing power and consolidating social order. Ceremonies were staged in the public spaces of Mediterranean cities to connect people, objects, and places. This study will explore the relationship between secular ritual, its multisensory effects, and urban spaces in three Mediterranean cities—Cairo, Constantinople, and Venice. The deployment of political, civic, and judicial ritual in a cityscape with richly ornamented architectural structures highlighted the theatricality of ceremony and defined a multisensory landscape that was meant to overwhelm the senses and impress participants and spectators alike. The nexus of space, ceremony, and the sensory deepened the meaning of ritual acts, created social solidarity and consensus, highlighted tradition, naturalized dominion, conveyed legitimacy, and activated public architecture in the service of political and social goals in these Mediterranean capitals.

Cairo, Constantinople, and Venice were all cosmopolitan, international cities, deeply integrated into the Mediterranean environment. Each city played a major role in economic and diplomatic networks, and representatives from these cities interacted with one another on a regular basis over centuries. Each city had a rich and diverse cityscape that had been shaped and embellished over time. History and tradition defined these urban settings, and the built environment was vital for bolstering civic identity and displaying political authority to inhabitants, visitors, and Mediterranean polities in general. All the political regimes addressed here were autocratic, though Venice maintained a fragile balance between an individual ruler (the doge) and a representative government (Muir 1981, p. 185). As such, in all three cases, the trappings of absolute power were significant for acquiring and maintaining authority. Lines of succession were not secure, and justification for an individual’s rule loomed large in the public display of power. And finally, documentary and visual evidence makes clear that ceremonials mattered in Venice, Cairo, and Constantinople. Texts dedicated to the description and codification of ritual, historical accounts of ritual activities, and the rich and multifaceted visual culture of ceremony demonstrate that these were ceremonial cities, places where the inhabitants understood the social, political, economic, and cultural importance of ritual activity staged in the city’s streets (Fenlon 2007).

This paper will address the nexus of ceremonial and cityscape through the lens of interdisciplinary ritual, material culture, and spatial studies (Veikou and Nilsson 2022; Veikou 2016; Manolopoulou 2016; Tally 2013; Elsner 2012). For each of these locales, various publications address the relationship between ritual and the cityscape (Rabbat 2014, 2023; Sayyid 2023; Bailey 2017; Kurtzman 2016; Van Steenbergen 2013; Macrides 2011, 2013b; Fenlon 2007, 2009; Glixon 2003; Berger 2001, 2002; Bauer 2001; Sanders 1994; Behrens-Abouseif 1989, 2007; Muir 1981). Scholarship on this topic acknowledges the mutually reinforcing nature of architecture and ritual—how architecture reflects and magnifies the import of ritual and ceremonial activities focus attention on particular spaces and structures in an urban center (Marinis 2012, 2014; Fenlon 2007). Scholars have also noted the role of people in defining this relationship. Individually and in groups, human actors articulate the ways that ceremonies and structures were used and understood by diverse audiences.

Another significant theme for this study is the connection of senses other than sight to the function and perception of architectural space. Scholarship on medieval and early modern soundscapes has become more prevalent as architectural specialists explore the multisensory effects of architecture (Illiano 2024; Boynton and Reilly 2015; Papalexandrou 2016; Currie 2014). The acoustic qualities of famous buildings like Hagia Sophia and the Basilica of San Marco, for example, influenced the reception of music and liturgy (Pentcheva 2021; Howard and Moretti 2009). Sound in the city is less well studied, but recent scholarship has addressed religious sound—church bells, Qur’anic recitation—and secular sound—military bands, musical performances, fireworks, cannon fire—in addition to the power of silence (Macaraig 2025; Frenkel 2018; Ergin 2015; Atkinson 2012; Ergin 2008).

Few of these studies are cross-cultural or comparative in nature, a notable exception being the individual and collective work of Leslie Brubaker and Chris Wickham (Brubaker and Wickham 2021; Brubaker 2018). Their interest lies in the unfolding of ceremony, its components, and participants from 500–1000, but they do not address in detail the spaces for ceremonial and spectacle. This study builds on their comparative approach to ritual by studying urban ceremonies with multisensory effects in three distinct but complementary Mediterranean urban spaces, highlighting the role that architecture and the cityscape play as active participants in the creation of meaning for ritual activities.

2. The Celebration of the Ruler in Urban Processions

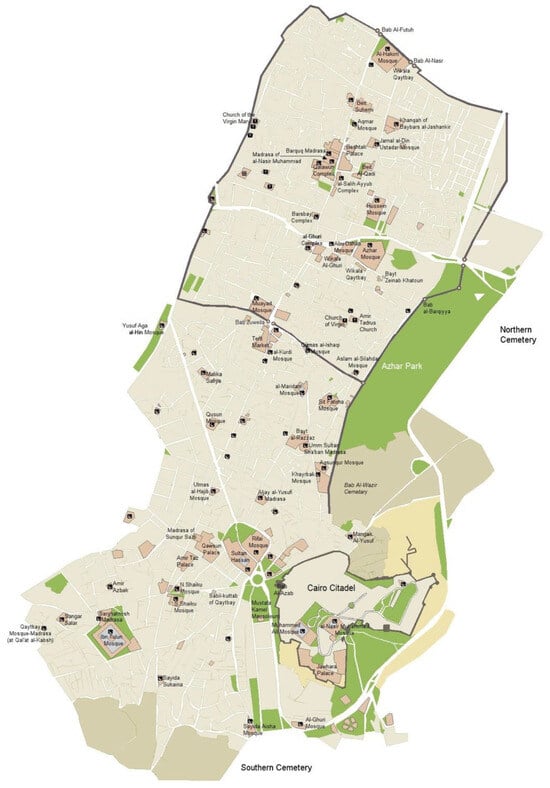

In these three Mediterranean locales, ruling elites performed power by presenting themselves to the people in magnificent processions. In Cairo, the investiture ceremony for the sultan was an event replete with political significance and symbolism, given the often-contested nature of Mamluk succession (Bresc 1993). The sultan designate would travel from the Citadel in the south to reach the northern gate, Bab al-Nasr (Figure 1). The ruler entered the city with all the Mamluk regalia, including a yellow silk parasol, decorated saddle cover, and lavish clothing (Shoshan 1993, p. 74; Bresc 1993, p. 88). He would then traverse Cairo with a massive retinue of amirs, dignitaries, and administrative officials to the acclaim of great crowds. The streets were lined with silk as music played and the new ruler distributed coins to the populace waiting along the route. The grand parade through the city was an important symbolic event as it constituted a key moment of interaction between the ruler and his subjects (Ghaly 2004, p. 165). The people decorated their shops and homes to celebrate the ruler’s accession and provided the audience necessary for a successful ritual. The investiture procession thus highlighted solidarity and consensus, as the new sultan bolstered his legitimacy through displays of royal symbols and power.

Figure 1.

Cairo, map of the city with main processional route. Map by Arab Hafez and Robert Prazeres. Wikimedia Commons.

Once the retinue reached the Citadel, the actual ceremony of investiture was a relatively simple, private affair. The sultan sat on the throne in the Iwan al-Kabir, or main reception hall, surrounded by high officials. He received the recognition of his peers, was given a regnal name, and the Abbasid caliph invested him with a black robe of honor (Bresc 1993, pp. 85–86; Behrens-Abouseif 1989, p. 32; Stowasser 1984, p. 16). The accession to the throne was then celebrated with a great banquet. The Mamluk investiture ceremony was an entirely secular affair that centered on political legitimacy and military might (Behrens-Abouseif 2007, pp. 26, 30; Bresc 1993, pp. 83, 89, 94). These were qualities deemed essential for a Mamluk sultan and there were no references to divine providence or God-given right to rule. Even the presence of the Abbasid caliph at the ceremony was more about legitimation and continuity than religious affirmation. The resonance of symbols of authority—regalia, lavish robes, a parade of political elites—was heightened by their extended presence in the city and the time it took to traverse Cairo from north to south. The royal investiture ceremony concretized political stability and permanence, qualities that were essential in a political culture characterized by an uncertain line of succession.

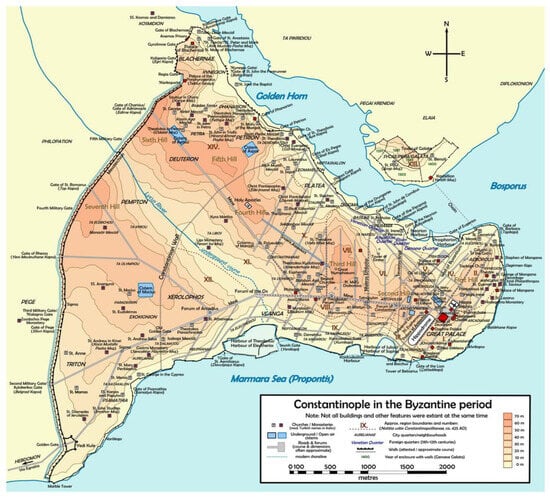

The most significant political ritual staged in the Byzantine capital was the coronation procession and ceremony, generally scheduled to coincide with major religious holidays (Brubaker and Wickham 2021, p. 141; Herrin 2021, p. 297; Shawcross 2012, p. 191; Dagron 2003, pp. 54, 61, 67, 78; Bauer 2001, p. 42; Majeska 1997, p. 2; McCormick 1985, p. 12). Many variations to the coronation ritual existed but the processional route for the new emperor remained fairly consistent over time and defined the main ceremonial path through the city for imperial entries, triumphs, and other civic celebrations in Constantinople (Brubaker and Wickham 2021, p. 140; Featherstone 2006, p. 59; Bauer 2001, p. 58; Berger 2001, p. 83). The route began outside the city at the Hebdomon (Figure 2). The new ruler then entered the city through the Golden Gate and proceeded north to reach the main road in the capital, the Mese. The procession might stop at various churches and monuments along the way, such as the church of the Holy Apostles, the Forum of Constantine, the Pantokrator Monastery, and the church of St. Polyeuktos, before heading to the Great Palace located at the southeastern tip of the city. The emperor-elect would spend the night before the coronation in the Great Palace and proceed to Hagia Sophia the next day. The coronation ritual was filled with symbolic gestures repeated over the centuries that visualized the legitimacy of the ruler and manifested continuity with the past (Brubaker and Wickham 2021, pp. 129–30; Herrin 2021, p. 306; Dagron 2003, p. 70; Cameron 1987, p. 131; McCormick 1985, pp. 18–20).

Figure 2.

Constantinople, map of city with main processional route. Map by Cplakidas. Wikimedia Commons.

On coronation day, the new ruler traveled the short distance from the palace to the church, where he was met by the patriarch. They entered the church together and the patriarch crowned and anointed the emperor seated on a throne in imperial robes. After the liturgy was celebrated, the emperor left Hagia Sophia, where he was acclaimed by the people—inhabitants of the city, representatives of the circus factions, court officials—who bowed before him and wished him a long reign. They physically raised the ruler on a shield or tribune as a symbol of his elevated status. The emperor distributed largesse to the people and then returned to the palace, where he celebrated his accession with a banquet.

Though no two coronations were identical, the main characteristics of the ceremony and its symbolic elements continued for centuries and were imitated by successor and rival states. When the crusaders captured the city of Constantinople in May 1204, they staged a similar ceremony for the Latin Emperor, Baldwin, replete with regalia like a crown, gems, lavish robes, and the imperial purple shoes (Burkhardt 2013, pp. 282–85; Shawcross 2012, pp. 184–90; Van Tricht 2011, pp. 82–83; Macrides 2002, p. 199). In Trebizond, where members of the Komnenos family established dominion after the fall of the Byzantine capital, rulers imitated the Byzantine coronation ceremony and processional route that included their own church of Hagia Sophia (Eastmond 2004, pp. 49, 55, 56). When the Latin occupation of Constantinople ended in 1261, Michael VIII Palaeologos orchestrated a triumphal entrance into the city. He took possession of the capital carrying an icon of the Virgin Hodegetria on the feast day of the Assumption of the Virgin Mary, crediting the Virgin for the victory and demonstrating the intertwined quality of religious and political ritual (Kiousopoulou 2022, pp. 359–60; Herrin 2021, p. 322; Burkhardt 2013, p. 290; Shawcross 2012, p. 214; Shepard 2012, p. 73; Eastmond 2004, p. 4; Berger 2001, p. 84).

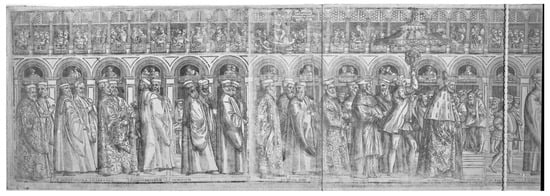

The ducal andata was Venice’s prototypical ceremonial display. This procession with the doge at the center combined religious and political motivations while reaffirming social hierarchies and a collective belief in the myth of Venice (Fenlon 2007, pp. 123, 133; 2009, p. 87; 2017, p. 133; Kurtzman 2016, pp. 50–51; Glixon 2003, p. 56; Muir 1981, pp. 190–211, 223, 305). The doge participated in numerous andate throughout the calendar year, perhaps as many as ninety. The processions often stayed within the confines of the ducal palace, San Marco, and its extensive piazza but could also visit other spaces in the city, creating a ritual topography that connected all the neighborhoods of Venice (Fenlon 2007, pp. 119, 125, 126; 2009, p. 92; 2017, p. 135; Kurtzman 2016, pp. 57, 58; Muir 1981, pp. 209, 211). The ducal andata was a powerful tool for asserting political control while highlighting social cohesion in a shared set of ritual acts and spaces.

The andata took the doge from the ducal palace to San Marco and from there out into Piazza San Marco (Figure 3). By the thirteenth century, strict protocol determined the order of participants in the procession, with the cittadini at the head, the patricians at the end, and the doge in the middle (Fenlon 2007, p. 124; 2009, pp. 89–91; 2017, p. 133; Kurtzman 2016, pp. 51–52; Muir 1981, pp. 187–89, 192, 193–96). Ceremonial books recorded the order of officials and dignitaries in the procession as well as the place of the clergy, patriarch, guilds, members of Venice’s confraternities or scuole, foreign visitors, and the city’s inhabitants. The most elaborate processions included special symbols of ducal authority called trionfi (Muir 1981, pp. 103–19; Fenlon 2007, p. 120; Fenlon 2009, p. 88; 2017, p. 135; Kurtzman 2016, p. 52). These ceremonial objects were given to the doge by the pope according to legend and demonstrated the doge’s parity with both popes and emperors. A candle, trumpets, sword, seal, etc., served as symbols of state and were carried in honor to manifest the elevated status of Venice’s leader.

Figure 3.

Matteo Pagani woodcut depicting andata, 1550–60. © The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence.

Other andate traveled beyond the confines of Piazza San Marco to honor saints or celebrate important historical events. The doge visited San Giorgio Maggiore to venerate the relics of Saint Stephen and also came to the church during Christmas celebrations (Kurtzman 2016, p. 63; Fenlon 2007, pp. 35, 287–89). The Battle of Lepanto against the Turks was won on the feast day of Santa Giustina in 1571 and the Venetian government instituted an annual procession to the church dedicated to that saint to commemorate this great victory (Fenlon 2007, pp. 173, 180–83, 273–85; 2017, pp. 140–41; Muir 1981, p. 204). In the aftermath of a devastating outbreak of the plague in 1575–77, a ducal procession went yearly to the church of Il Redentore to give thanks to God for deliverance from the plague (Kurtzman 2016, p. 63; Fenlon 2007, pp. 285–91; Muir 1981, pp. 214–16).

The feast day of Corpus Christi developed into one of the most spectacular civic and religious celebrations in Venice as the feast coincided with the departure of pilgrims to the Holy Land (Fenlon 2007, pp. 125–26; 2009, p. 123; 2017, p. 140; Muir 1981, pp. 223–30). The ducal procession expanded to include the many foreigners in Venice who were waiting for the annual fleets that sailed to Jerusalem. The massive procession around Piazza San Marco took hours to complete and the visitors to Venice were awestruck by the pomp and magnificence, the trionfi, luxurious garments, the sounds of the ducal trumpets, and choral music. This standard religious holiday was given a particularly Venetian significance in its connection to Holy Land pilgrimage (Fenlon 2017, p. 140; Muir 1981, pp. 228–30). Pilgrims would visit the holy sites and innumerable relics on display in Venice and the city itself was sanctified by the creation of its own sacred topography as well as its connection to the holy city of Jerusalem.

Rituals associated with public humiliation, punishment, and execution of criminals were remarkably similar across the Mediterranean as well. Such spectacles were perennially popular and attracted large crowds as they combined the administration of justice with a ritual cleansing of the body politic (Ruggiero 1994, pp. 176, 178, 189; Muir 1981, p. 247). In all three cities, perpetrators could be punished at the scene of the crime to demonstrate that the long arm of the law extended everywhere in the city (Behrens-Abouseif 2014, pp. 77–83; Ghaly 2004, p. 185). There were also spaces constructed especially for the execution of justice that served as end points for judicial ritual. Criminals were paraded through the city and subjected to ritual humiliation in an inversion of a triumphal procession (Messis 2022, pp. 48–62; Tirnanic 2021; Hillsdale 2021, p. 246; Heher 2015; Behrens-Abouseif 2007, p. 30; Cameron 1987, pp. 119–20). They wore rags or nothing at all and sat backwards on a donkey or camel. Once at the site of punishment, various tortures and bodily mutilations took place before offenders were decapitated, hanged, or quartered. Government officials had body parts put on display at key locations in the city to remind the populace of the dire consequences of committing crimes, particularly offenses against the state.

3. Multisensory Experiences of Urban Ceremonial

Ceremonies in Venice, Constantinople, and Cairo were multisensory affairs, engaging with participants and audiences through a combination of senses. Spectacle impacted the sense of sight with the greatest immediacy. Adorning the permanent physical structures that framed spectacle were a variety of decorations. Textiles—tapestries, banners, silks—in particular played a central role, clothing the participants in finery, covering vehicles and animals but also paving the streets and hanging from balconies, windows, and storefronts (Brubaker 2018, pp. 223, 226; 2022, p. 3; Mauder 2021, pp. 965, 969; Brubaker and Wickham 2021, pp. 149, 151; Frenkel 2018, pp. 7–9; 2019, p. 247; Moukarzel 2019, p. 690; Behrens-Abouseif 2007, pp. 26, 28, 29; 2014, p. 110; Macrides 2013c, p. 377; Van Tricht 2011, p. 82; Featherstone 2006, p. 50; Dagron 2003, p. 91; Berger 2001, pp. 77–78; 2002, p. 15; Bresc 1993, pp. 87, 89). The Mamluks had a predilection for yellow silk based on Ayyubid precedents and covered themselves, their horses, streets, and buildings with textiles on the occasion of a royal entry or coronation of a new ruler. In Venice, particular types of dress were required for those participating in civic ceremonies (Glixon 2003). Augmenting the textile decoration were candles and lanterns, displayed on buildings, carried in procession, or floating on the water (Manolopoulou 2022, p. 5; Brubaker and Wickham 2021, p. 132; Mauder 2021, p. 967; Frenkel 2018, p. 9; 2019, p. 241; Behrens-Abouseif 2007, pp. 30, 31; 2014, pp. 13, 75; Van Steenbergen 2013, pp. 236, 237; Macrides 2011, p. 234; 2013a, p. 442; Magdalino 2011, p. 132; Broadbridge 2008, p. 47; Ghaly 2004, pp. 174, 178; Shoshan 1993, p. 75; Muir 1981, pp. 218, 220). Garlands of flowers and aromatic plants adorned routes and structures, providing a sweet smell to complement their visual beauty. In the procession, participants carried liturgical objects, relics, and icons and rulers adorned themselves with regalia and other symbols of power. The Mamluk sultan had a silk parasol, distinctive headgear, and elaborate equestrian trappings, while the Venetian doge conducted his andata with trionfi, symbols of ducal authority (Mauder 2021, p. 965; Behrens-Abouseif 2007, p. 26; Muir 1981, pp. 103–18). Musical instruments helped define the soundscape but they were also impressive visually; the doge’s trumpets were massive objects, as were the Mamluk sultan’s kettledrums. The Byzantine emperor alone had the prerogative to be accompanied by a golden organ which was played in processions and within the palace (Brubaker and Wickham 2021, p. 150; Herrin 2021, p. 303; Currie 2014, pp. 427–28, 441, 445; Featherstone 2006, p. 50; Berger 2006, pp. 63–66; Dagron 2003, p. 91). Fireworks displays lit up the sky for spectators in their boats, celebrating festivals like the Plenitude of the Nile in Cairo or the Marriage to the Sea in Venice. And in a more gruesome spectacle, mutilated bodies and decapitated heads would be on display in judicial rituals and military victory parades (Heher 2015; Behrens-Abouseif 2014, p. 77; Barry 2010, pp. 37–38, 42).

Vision, then, was the sense that provided immediacy; audiences saw wondrous, awe-inspiring things when the procession or ritual was right in front of them. Sound (and to some degree smell), however, worked in a wider geographical range and extended the sensory effect of ceremony over space and time. The broad extension of sound made it an ideal communication tool, informing the population of events over a great distance (Brubaker and Wickham 2021, p. 143; Frenkel 2018, pp. 2, 7–8, 20; Kurtzman 2016, p. 67). The soundscape of these cities was defined by religious sound—the call to prayer, Qur’an recitation, bells ringing, the chanting and singing of hymns (Macaraig 2025, pp. 379, 384, 399–401; Brubaker 2018, pp. 223, 226; 2022, pp. 3, 10; Brubaker and Wickham 2021, pp. 132, 143, 150; Hillsdale 2021, p. 223; Frenkel 2018, pp. 12, 17, 20; Kurtzman 2016, pp. 50, 62; Currie 2014, p. 428; Macrides et al. 2013, p. 149; Macrides 2013a, pp. 440, 442; 2013b, p. 399; Magdalino 2011, p. 142; Liudprand of Cremona 2007, p. 244; Featherstone 2006, p. 50; Dagron 2003, p. 55; Bauer 2001, p. 56; Shoshan 1993, pp. 73, 75; Cameron 1987, pp. 115–16; Muir 1981, pp. 121, 220, 281). Instrumental musicians and choirs performed together or separately for religious celebrations like the departure of the pilgrimage caravan to Mecca, saints’ feast days, or rituals of propitiation or thanksgiving (Brubaker 2022, p. 10; Mauder 2021, pp. 965, 980; Brubaker and Wickham 2021, pp. 143, 150; Herrin 2021, pp. 302, 303, 306; Moukarzel 2019, p. 690; Frenkel 2018, pp. 5–12; Fenlon 2017, pp. 135, 136; Kurtzman 2016, pp. 51, 59, 60, 62, 65, 66; Behrens-Abouseif 1989, p. 42; 2007, pp. 25, 29, 30; 2014, pp. 13, 51, 75, 88; Currie 2014, pp. 428, 440, 441; Macrides et al. 2013, pp. 81, 145; Van Steenbergen 2013, p. 236; Macrides 2011, p. 234; 2013a, pp. 439, 440; 2013b, p. 399; Fenlon 2007, p. 124; Berger 2002, p. 16; 2006, pp. 65–66; Ghaly 2004, p. 178; Shoshan 1993, p. 75; Cameron 1987, p. 115; Stowasser 1984, p. 19). Secular or what might also be called political sound was equally important and far noisier, encompassing celebration, warning, and displays of authority. In ceremonies staged in urban settings, spectators would hear the musical instruments well before they saw them. The beating of drums reverberated through the city and the blare of trumpets from military bands and musical ensembles carried great distances. As the procession came closer, singing and acclaiming voices became clearer, as well as the music produced by the more subtle instruments. The sound of footfalls, horses’ hooves, chariots, and vehicles carrying floats and displays reached the spectators to complement the visual magnificence of the ceremony. Even louder than the drums and trumpets were the fireworks and the gun and cannon shots that marked great military victories or religious festivals (Frenkel 2018, p. 11; 2019, pp. 243, 244; Kurtzman 2016, pp. 62, 66; Behrens-Abouseif 2007, p. 30; 2014, p. 110; Fenlon 2007, p. 173).

The human voice may not have been the most impressive sound in the soundscape but it was omnipresent, with people talking, singing, laughing, crying, acclaiming the ruler, asking for assistance and largesse, and discussing the spectacle unfolding before them. However, the opposite, the sound of silence, was highly effective in the midst of this cacophony (Herrin 2021, p. 308; Haines-Eitzen 2016; Ergin 2015, pp. 126–29; Magdalino 2011, p. 132; El-Cheikh 2004, p. 156; Berger 2001, p. 78; Muir 1981, p. 218). During a ceremony, a specific sound would indicate that it was time to be silent and this silence was only to be broken at the ruler’s command. Emperors, sultans, and doges exercised power over sound and therefore control over the spectacle as a display of secular and religious authority (Herrin 2021, p. 308; Frenkel 2018, pp. 19–20; Currie 2014, pp. 428, 437).

Two other senses engaged in ceremonial, albeit in a more ancillary way, were taste and smell. Just about every ceremony ended with a banquet. This could be an exquisite feast at the table of the ruler, free food and drink provided by the sponsor of the event at the venue, or the enjoyment of street food at a festival (Brubaker 2022, p. 10; Frenkel 2019, p. 255; Harvey and Mullett 2016; Behrens-Abouseif 2014, pp. 12, 75; Van Steenbergen 2013, pp. 232, 236; Macrides et al. 2013, pp. 167, 237, 240–41; Broadbridge 2008, pp. 22, 112; Featherstone 2006, pp. 51, 57; Schreiner 2006, p. 107; Ghaly 2004, p. 167). In Christian religious ceremonies, the taking of the Eucharist during the Mass also engaged the sense of taste. Smell accompanied taste in the service of food and drink but extended beyond refreshments to the scent of flowers, herbs, incense and perfume, as well as the less pleasant smells of people and animals that these fragrances were meant to mask (Macaraig 2025, pp. 392–98; Manolopoulou 2022, p. 5; Brubaker 2022, pp. 3, 10; Brubaker and Wickham 2021, pp. 144, 150–51, 153; Mauder 2021, pp. 973, 976; Macrides et al. 2013, p. 171; Broadbridge 2008, p. 47; Ghaly 2004, p. 168; Berger 2001, p. 77).

4. Meanings and Perception of Political Ritual in Venice, Constantinople, and Cairo

The author of the Book of Ceremonies stated that “imperial rule, well ordered by praiseworthy ceremonial, strikes wonder in both foreigners and our own people,” while the Mamluk historian Ibn Taghribirdi noted that ceremonies “glorified kings and celebrated events” (Hillsdale 2021, p. 226; Behrens-Abouseif 2007, p. 25). Both authors clearly understood the fundamental role that ceremonial played in state building, where political rituals concretized and performed state power through tradition, display, and distinction. Rulers could legitimize their claim to authority by catalyzing time-honored rituals. As participants in ceremonies whose symbolism and ritual gestures had been established for centuries, new rulers manifested the permanence and legitimacy of their reign (Ousterhout 2022, pp. 53–54; Kurtzman 2016, p. 53; Van Steenbergen 2013, pp. 232, 243, 258; Shawcross 2012, pp. 193; Behrens-Abouseif 2007, p. 25; Fenlon 2007, pp. 83, 124; Dagron 2002, p. 34; Cameron 1987, p. 122). In the three political systems addressed here, there was no secure hereditary line of succession, so the individual who ascended to power bolstered his claim through connections to the past. Continuity with earlier rulers established a seemingly unassailable lineage in political contexts characterized by usurpation, violence, assassination, and political unrest. Ritual acts and potent symbols of power gave the impression of permanence and stability through their adherence to custom.

In addition to highlighting tradition, ceremonial legitimized power through awe-inspiring displays of magnificence and splendor. Ceremonies brought the court out of the palace and into the streets, providing an opportunity for the people to view and interact with their ruler (Ruggles 2020, p. 51; Behrens-Abouseif 2007, p. 33). This was a key moment to make an impression and display the trappings of legitimate rule. As the author of the Book of Ceremonies noted, a ceremony’s intent was to strike awe and wonder in all present. The sensory stimulation of a coronation or victory parade, with its pomp and wealth, staged empire in the here and now, complementing the allusions to the past in the traditional aspects of ceremonial. Various symbols of rule, the trionfi, regalia, weapons, headgear and clothing, the decoration of the streets and buildings with flowers, textiles, and lanterns, the showering of coins, all contributed to creating an unforgettable experience that elevated those present above the everyday, marking time in the context of a special event (Frenkel 2019, pp. 242, 256; Kurtzman 2016, p. 52; Shawcross 2012, pp. 182, 183; Fenlon 2007, pp. 82; Cameron 1987, p. 118; Muir 1981, p. 118).

A central manifestation of the social aspects of ceremonial was the creation of distinction. Ritualized activities united people in a common experience but also visualized the hierarchy of state, where there could only be one person at the top (Rabbat 2023, p. 79; Mauder 2021, pp. 978, 1003; Brubaker and Wickham 2021, 229; Magdalino 2011, p. 132; Eastmond 2004, p. 47; Cameron 1987, p. 136; Muir 1981, pp. 189, 211). Processions manifested social status through one’s physical place in the event—spectator or participant, front, middle, or end of the parade, proximity to the sovereign. They solidified social bonds while ensuring that everyone knew literally where they stood as they participated in ritual movements through the city.

Ceremonial has been characterized as the place where power and community met and these performances of power spoke to larger social issues (Brubaker and Wickham 2021, p. 145). Jeffrey Kurtzman has referred to civic processions as “societal glue”, creating community, strengthening bonds that already existed, or re-establishing connections that had been severed in times of unrest or strife (Kurtzman 2016, p. 66). The rituals associated with the prosecution of criminals, in particular, highlighted the repairing of the social fabric torn apart by offenses against the state. The wrongdoers were punished publicly in the streets and their dismembered bodies were removed from the city; these ritual acts constituted a ceremonial cleansing of urban space (Tirnanic 2021, pp. 38, 45–46, 50; Maleon 2017, p. 57; Heher 2015, p. 19; Ruggiero 1994, pp. 176–78, 189; Muir 1981, p. 245).

People of all levels of society participated in or were spectators at these ceremonies but all were witnesses, not just passively watching the proceedings but actively attesting to the truth of the claims made by the event’s organizers (Mullett 2025, p. 254). Processions activated society and gave all involved a kinetic, interactive role in fostering community and civic identity. The communal movement through the city communicated shared values, stories, and beliefs while solidifying social bonds. It also physically connected parts of the city that were geographically distant, providing a sense of social integration but also reaffirming the ruler’s control over every corner of the city (Kurtzman 2016, p. 66).

Participation in civic rituals was a visual affirmation of concord, unity, and consensus. It demonstrated the harmonious coexistence of the city’s inhabitants and their acceptance of societal order and hierarchy (Mauder 2021, p. 978; Brubaker 2018, p. 220; Fenlon 2007, p. 124; 2017, pp. 136, 147; Kurtzman 2016, p. 50; Dagron 2002, pp. 34, 35; Georgopoulou 2001, p. 224; Bauer 2001, p. 28; Muir 1981, p. 200). These public ceremonies had an internal audience, then, for whom the ritual events enacted the ideal image of the city. But there was also an external audience—allies, enemies, competitors—who were presented with a picture of a unified populace prepared to defend itself from outside threats (Muir 1981, p. 233). The movement of processions through the city created a living thread, connecting all levels of society but forging bonds between people and urban spaces, physically situating this ordered society in the streets and structures of these three cities.

Another salient characteristic of these urban political ceremonies is their theatricality (Rabbat 2023, p. 79; Manolopoulou 2022, p. 9; Dagron 2002, p. 36; 2011, p. 248; El-Cheikh 2004, p. 156). Rituals were orchestrated, staged, and performed. They required a stage, which in this case was the entire city and its built environment. They had their own material culture, props in the form of decoration, regalia, costumes, and architecture. Actors were essential as well, with everyone in the city playing a role (Brubaker and Wickham 2021, p. 152; Dagron 2002, p. 36). All these elements of performance were marshaled in the service of a story line provided by the ceremony’s organizers, celebrating a military victory, displaying political legitimacy, highlighting social harmony, and performing the administration of justice. The city was a venue of exhibition in which the architectural structures provided a backdrop for the ceremonies and the presentation of the ruler with potent symbols of power (Mullett 2025, pp. 256–57; Rabbat 2023, p. 79; Manolopoulou 2022, p. 9). The spectacle was meant to be awe-inspiring and dazzling, overwhelming the senses with the visual opulence of the people, the props and space, the sounds and smells. The pomp and splendor elevated all in attendance above the ordinary, engraving the event in the collective communal memory and in the structures and spaces that comprised this performative cityscape. These performances redefined the urban landscape and reconstituted meaning for both the ritual and space with each recurrence of the ceremony (Veikou 2016, p. 150).

Ritual and spectacle highlighted continuity through their regular reenactment over centuries, structuring both space and time (Manolopoulou 2019, p. 158; Brubaker 2018, p. 229; Ruggiero 1994, p. 176; Muir 1981, pp. 231, 241). The interplay of the spatial and temporal could imprint itself on the urban landscape in a temporary or permanent way. Ceremonial acts marked time throughout the calendar year as events that constituted stops in the movement of unvaried time. The numerous processions that took place in Cairo, Constantinople, and Venice provided moments of heightened significance in a rich cycle of events throughout the calendar year. The repetition of ceremonies over years, decades, and centuries ordered time diachronically, creating connections between past, present, and future (Manolopoulou 2019, p. 165). Ritual structured space by forming itineraries but also by demarcating specific locales in the city that were filled with symbolic power. Visiting these places on a regular basis deepened their significance and imbued them with their own site-specific history. In some sense, performances at these sites produced space and gave it form and meaning that could change with each new interaction (Veikou 2016, p. 150). Space and time were both mutable and ceremonial fixed them in a city’s collective memory.

Memory, of course, is an essential characteristic of ritual (Mullett 2025, p. 258; Manolopoulou 2019, pp. 156, 163; Van Steenbergen 2013, p. 261; Muir 1981, p. 212). It kept the meanings of ritual alive and passed down traditions over time. Continuity and custom provided the foundation for claims of political legitimacy by rulers, referencing the cumulative force of all those leaders who performed the rituals before them. An evocation of the past worked to reinforce claims of power in the present, making them seem natural and immutable (Dagron 2003, p. 113; Bauer 2001, p. 28; Cameron 1987, p. 122). Spaces could be the storehouses of this collective social memory where people gathered to commemorate past events, participate in key rituals of civic governance, or insert a new ruler into a lineage of great and powerful predecessors. Memory connected people to the past but also to one another in the present as they participated in time-honored ceremonies that celebrated political authority and bolstered social consensus and cohesion.

5. The Nexus of Ceremonial and Architectural Space in the City

All the ephemeral and multisensory qualities of ceremonial addressed in the previous section were reinforced and concretized by their physical and spatial setting. The structures that served as venues for ceremony and their elaborate decorative elements conveyed the same political, social, cultural messages that were also central to ritual performance. State ceremonial and urban architectural structures, particularly those decorated with spolia, complemented one another in their dichotomy of transience and permanence and their presentation of similar claims about social order, community, tradition, and political legitimacy.

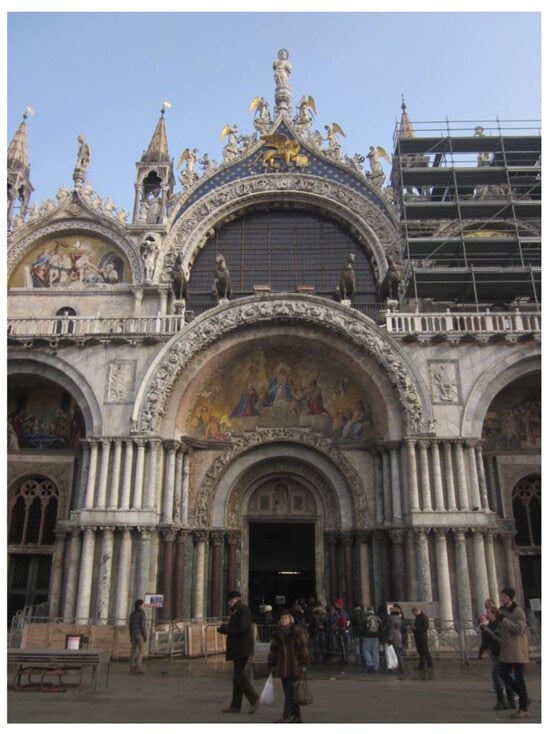

The Basilica of San Marco is a structure covered from top to bottom with spolia, both plunder of war and pseudo-spoils, that is, objects made to look like they originated from other cultures and time periods (Mathews 2017, pp. 87–90; Fenlon 2007, pp. 19–20) (Figure 4). San Marco and its piazza were the ceremonial nexus of Venice; the ducal andata and other processions wound around the square as the doge presented himself to the Venetian public in front of the basilica (Fenlon 2007, 2009). The church’s rich, colorful, and textural façade served as a dramatic stage for spectacle, like a Roman theater with its undulating, rich backdrop of multicolored columns. The façade of San Marco also resembled a triumphal arch that framed the doge as he appeared before the church. Above him on the façade, the four horses and quadriga furthered this triumphal significance, making references to Roman triumphal practices through the use of actual Roman spolia (Barry 2010, p. 19; Fenlon 2007, p. 22) (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Venice, Basilica of San Marco, west façade. Photograph by Zairon. Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 5.

Venice, Basilica of San Marco, main entrance. Photograph by author.

The Piazza San Marco in front of the church heightened the theatricality and impact of spectacle. The square itself was enlarged in the twelfth century to allow for grander processions with more observers and participants (Fenlon 2007, pp. 88–89). Places of ritual like Piazza San Marco were not just backdrops but auditoria, spaces that surrounded and enclosed ritual activities and included all present in the celebration (Figure 6). This idea of an auditorium is evoked in Sansovino’s renovations of the Piazzetta begun in the 1530s, where the library built facing the square had large windows that could serve as viewing areas, like boxes in a theater (Johnson 2000, p. 447). Elite members of society could watch the proceedings in the piazza below from a grand elevated space. But they too were on display, contributing to the visual spectacle unfolding in the square, whether it be an execution, an informal theatrical performance, or a solemn civic ritual.

Figure 6.

Venice, Piazzetta with two columns. Photograph by Wolfgang Moroder. Wikimedia Commons.

Mamluk buildings also framed ritual activities and provided a magnificent spatial context for the presentation of the ruler to the public. The Iwan al-Kabir, the main audience hall of the Mamluks located on the Citadel, served as the ending point of the coronation procession that passed through the city (Figure 7). The ruler al-Nasir Muhammad constructed the hall in the early fourteenth century centered around a set of massive ancient Egyptian columns. At the same time that he embellished the audience hall with spolia, he elaborated the ceremonial that took place there—increasing pageantry and codifying protocol in a space that alluded to the grandeur and longevity of a great ancient civilization (Behrens-Abouseif 1989, p. 69; 2007, p. 27; Rabbat 1995, p. 228).

Figure 7.

Cairo, Iwan al-Kabir at the Citadel. Description de l’Égypte, tome premier, 1809. Image courtesy of the New York Public Library Digital Collections.

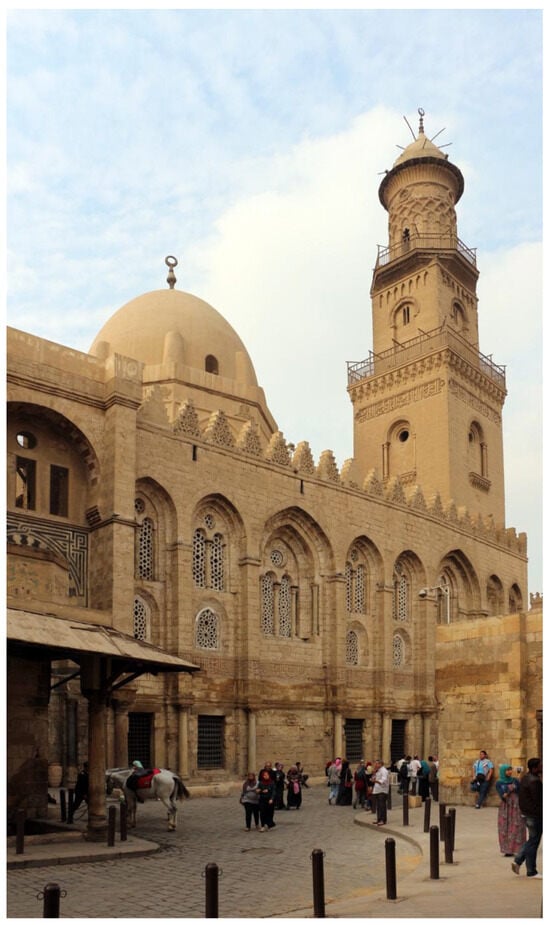

The Complex of Qalawun on Bayn al-Qasrayn was a significant stop on processional routes (Figure 8). It housed the tomb of one of the Mamluks’ most celebrated rulers and occupied a site of great visibility and prominence in the medieval city. Its exterior façade extended along the main ceremonial thoroughfare of Bayn al-Qasrayn and featured spolia columns and capitals from ancient Roman monuments. The tomb complex served as the site for regular administrative ceremonies but also was the destination for more impromptu but politically significant visits. Al-Ashraf Khalil visited his father’s grave in his grand tomb complex before he left for battle against the Franks in 1291 and another son, al-Nasir Muhammad, stopped at the complex after a successful campaign against the Mongols (Shoshan 1993, p. 74). Al-Nasir Muhammad regularly brought foreign visitors and dignitaries to his father’s tomb to impress them with its grandeur and rich ornamentation but also to remind them of his lineage (Van Steenbergen 2013, pp. 234, 236; Broadbridge 2008, pp. 111–12; Al-Harithy 2001, p. 83). Qalawun, for his part, placed his mausoleum across Bayn al-Qasrayn from the tomb of the Ayyubid ruler al-Salih Ayyub, his former master and the immediate predecessor to the Mamluks as rulers of Cairo (Van Steenbergen 2013, pp. 243, 259). Qalawun’s Complex on Bayn al-Qasrayn became a dynastic lieu de mémoire that highlighted family lineage but also established continuity through a succession of rulers that extended from antiquity to the present day (Van Steenbergen 2013, p. 262). This structure also framed vision through its long street-side facade that gave it maximum visibility (Behrens-Abouseif 2007, p. 33; Al-Harithy 2001, pp. 76, 79, 88). The uniformity and extent of the exterior decoration advertised the ruler’s power and his ability to build a monumental architectural complex in a key location in the heart of Cairo.

Figure 8.

Cairo, Funerary Complex of Sultan Qalawun, exterior façade. Photograph by Sailko. Wikimedia Commons.

References to antiquity were deployed to display power and forge connections to the past in Constantinople as well, where imperial fora constructed over the centuries framed stops along the way during imperial processions (Bauer 2001, p. 45). Like Qalawun’s juxtaposition of his tomb monument with that of al-Salih Ayyub on Bayn al-Qasrayn, Byzantine emperors pausing at the fora constructed by Arcadius, Theodosius, and Constantine highlighted continuity and presented themselves as successors to the great rulers responsible for commissioning grand public monuments in the capital (Kaldellis 2016, 2025; Yoncaci Arslan 2016; Bauer 2001, pp. 31–33, 37, 39–40, 45, 49–50). These fora were not simply stopping points but open throughways integrated into the urban fabric and the Mese itself. As an emperor entered the city to celebrate a coronation or triumph, he experienced the cumulative effect of imperial power visualized through the forum space but also through its monumental decoration. Each forum possessed victory monuments like columns and arches as well as imperial portraits. They were also ornamented with antiquities, connecting them to the Hippodrome which was the final destination for imperial processions.

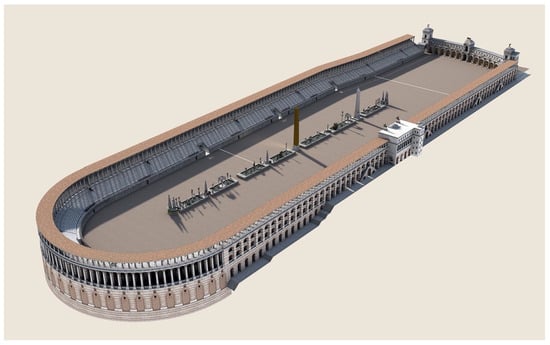

Like the imperial fora in Constantinople, the Hippodrome, too, made references to the imperial past through its decoration that included an extensive collection of antiquities and spoils of war (Akyürek 2021; Hillsdale 2021; Magdalino 2015, pp. 212–13; Bardill 2010; Bassett 2004; Guberti Bassett 1991) (Figure 9). The Hippodrome was the primary space for political display, entertainment, social interaction, and judicial punishment in the city (Akyürek 2021, pp. 22, 40–41; Brubaker and Wickham 2021, p. 130; Hillsdale 2021, pp. 223, 246; Magdalino 2011, pp. 133–34; Dagron 2003, pp. 66, 69; 2011). Military triumphal processions would wind through the city and end in the Hippodrome. The victorious emperor would display himself to the people on the kathisma or elevated platform there and perhaps even participate in the chariot races taking place. Up until the Crusader conquest of the city, the emperor would appear on the kathisma after coronations as well. The Hippodrome, then, was the key location in the city where the people could encounter and interact with their ruler (Rautman 2022, p. 280; Akyürek 2021, pp. 41, 46; Tirnanic 2021, p. 40; Hillsdale 2021, p. 223). It was a nexus of imperial power and its decoration provided a fitting backdrop for the display of majesty, legitimacy, and authority.

Figure 9.

Constantinople, Hippodrome reconstruction with ancient monuments. Image courtesy of Byzantium1200.

Antiquities that were spolia and in some cases spoils of war filled the Hippodrome like the decoration on Mamluk monuments and San Marco. Dozens of sculptures ornamented the spina/euripus of the racecourse, the entrances, and the imperial box. They included bronze and marble pieces from ancient Greece and Rome, brought from all over the empire by Constantine to embellish his new capital city. The collection included images of historical figures (especially emperors), gods, heroes, mythical creatures, and animals (Akyürek 2021; Bardill 2010; Guberti Bassett 1991). Most of the objects were looted or destroyed during the Fourth Crusade but three of these ancient objects are still in situ; in addition, the bronze horses now housed in the Basilica of San Marco in Venice are believed to have been part of the ancient spolia displayed in the Hippodrome.

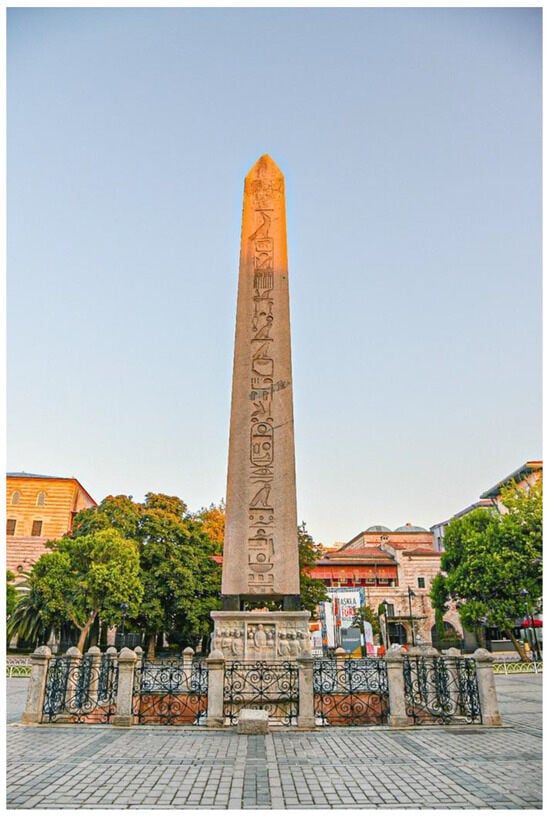

The three objects that still exist are the Obelisk of Theodosius, the masonry obelisk, and the Serpent Column. The granite obelisk that stands on the base made by Theodosius came from Karnak and was brought to Alexandria by Constantine (Akyürek 2021, pp. 22–26; Hillsdale 2021, p. 245; Bardill 2010, pp. 155–59; Guberti Bassett 1991, pp. 93–94) (Figure 10). The Emperor Julian had the monolith transported to Constantinople in the 360s but it was Theodosius who erected it in the Hippodrome, based on the model of Augustus’ obelisk in the Circus Maximus in Rome. The marble base possesses what Hillsdale calls a “tableaux of sovereignty,” depicting the emperor in his imperial box at the Hippodrome surrounded by officials, holding victory wreaths, accepting tribute from defeated enemies, and watching entertainments (Hillsdale 2021, p. 246; Akyürek 2021, pp. 26–29; Bardill 2010, pp. 161–63) (Figure 11). It also represents the erecting of the obelisk itself, an achievement that connected Theodosius with his ancient Roman counterparts.

Figure 10.

Istanbul, ancient Egyptian granite obelisk. Photograph by Apaleutos 25. Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 11.

Istanbul, Obelisk Base of Theodosius. Photograph by author.

A second obelisk graced the spina of the Hippodrome in the Middle Ages, though it is not known when it was created (Akyürek 2021, pp. 32–34; Bardill 2010, pp. 149–51). It is made of limestone blocks, not a monolithic piece of granite, and likely served as a pendant to the Egyptian obelisk put in place in the fourth century by Theodosius. The pair of obelisks in the Hippodrome would echo the two obelisks that adorned the Circus Maximus, erected by Augustus and Constantius II (Akyürek 2021, pp. 32, 34; Hillsdale 2021, p. 245; Bardill 2010, p. 153; Guberti Bassett 1991, p. 94). The final surviving object is the Serpent Column that stood between the obelisks on the spina (Akyürek 2021, pp. 30–32; Stephenson 2016; Bardill 2010, pp. 164–67; Guberti Bassett 1991, pp. 89–90, 94). It consists of a twisted bronze column surmounted by three serpent heads that originally held a golden tripod from the sanctuary of Apollo at Delphi (Figure 12). The column was an object of ancient Greek provenance presumably acquired by Constantine as a trophy. The monument would have had great significance because of its antiquity and provenance, like many of the other objects brought to the Hippodrome by Constantine and his successors.

Figure 12.

Istanbul, Serpent Column. Wikimedia Commons.

The antiquities in the Hippodrome conveyed meaning in a variety of ways—as vestiges of the past, as trophies, and as talismans or protective symbols. Ancient objects acquired throughout the empire, or more importantly taken from Rome, displayed continuity with the past (Kouneni 2025, pp. 25, 48; Rautman 2022, p. 281; Hillsdale 2021, pp. 228, 245; Guberti Bassett 1991, pp. 92–93, 95). Constantine wanted his new capital city to be a second Rome and he imitated salient monuments from the ancient capital, like the imperial fora and the Circus Maximus. Subsequent rulers made their mark on the city by adding their own fora ornamented with triumphal arches and columns, a repertoire of imagery once again borrowed from ancient Rome (Kaldellis 2016, p. 739; 2025, pp. 12, 16–17, 19–21; Yoncaci Arslan 2016, p. 127). This continuity extended back to antiquity to create a line of succession that connected Byzantine rulers to their predecessors, referencing the cumulative and accretive nature of imperial power. Some of the antiquities in the Hippodrome were spoils of war and the ones that were not took on a triumphal meaning by association with plundered objects (Hillsdale 2021, p. 245; Bardill 2010, pp. 157, 165; Guberti Bassett, 1991, pp. 89–90). The Hippodrome was the location for celebrating political and military triumphs in Constantinople, the culminating point of impressive and awe-inspiring processions through the city; as such, it was the appropriate venue for the display of plunder. The emperor presided over victory celebrations there that reinforced his legitimacy to rule and control a vast empire.

Finally, the collection of ancient sculptures in the Hippodrome affirmed the singularity of Constantinople and protected it from enemies. The supernatural power of sculpture, particularly ancient statuary, was well-acknowledged in Byzantium and this power could be harnessed to protect the city and its inhabitants from misfortune and calamity (Kouneni 2025, p. 28; Berger 2016, pp. 13–14, 22; Magdalino 2015, pp. 210, 213; Jeffreys 2014, p. 161; Saradi 2000, pp. 57–63; Guberti Bassett 1991, pp. 88–89; Mango 1963, pp. 61, 70). The fact that some of these objects served a similar function in antiquity further enhanced their power. The Hippodrome’s decoration, then, makes it a site of power that was otherworldly but not necessarily Christian, as the objects accumulated there had no religious iconography or significance. The Hippodrome was a place of history with Constantinople fashioned as the new Rome, given a patina of age and respectability through its collection of Roman spoils. It was also a locus of memory with the monuments housed there providing a concrete reminder of the temporary presence of the emperor, just as architectural structures in the city were physical vestiges of ephemeral ritual and ceremonial (Kouneni 2025, p. 32; Hillsdale 2021, p. 229; Bauer 2001, p. 49).

6. Judicial Punishment and Spoliate Architecture

Judicial venues also provided a concrete connection between elaborate spaces with spolia decoration and ritual activities. As a political space, the Hippodrome in Constantinople was the pre-eminent location for the display of defeated enemies and execution of criminals (Akyürek 2021, pp. 41, 47; Tirnanic 2021, pp. 40, 46; Hillsdale 2021, p. 246). There, the emperor affirmed his legitimate claim to power, so rebels and usurpers in particular were punished harshly to deter opposition and quell unrest. After a humiliating parade through the city, those who challenged imperial rule were brought to the Hippodrome where they were tortured and mutilated before large crowds (Messis 2022; Tirnanic 2021, pp. 38, 41, 46; Maleon 2017, pp. 48, 50–51, 55; Heher 2015, pp. 13–17). The horrific spectacle left an indelible impression, engraining the punishment in the memory of spectators as a deterrent against fomenting rebellion but also as a demonstration of rightful imperial order. The physical context of a space filled with antiquities and spoils of war enhanced the grandeur of the proceedings, underlined the current ruler’s authority, and affirmed his connection to great rulers and empires of the past (Tirnanic 2021, p. 50).

Like the Hippodrome in Constantinople, the area around San Marco and the doge’s palace served as the primary arena for enacting public executions, mutilations, and humiliations that provided forceful reminders of the power and reach of state justice. The two columns in the Piazzetta adjacent to San Marco were taken from Constantinople by Doge Sebastiano Ziani in the 1170s and marked the central space for judicial punishment in Venice (Barry 2010, p. 41; Fenlon 2007, pp. 13, 113; 2009, p. 115; Nelson 2007, pp. 147–48; Johnson 2000, pp. 444–45, 448; Muir 1981, p. 247) (Figure 6). Sculptures of the city’s patron saints, Mark and Theodore, stood on the columns and presided over the presentation of the condemned to the Venetian public before their torture and death. Criminal processions would cover the whole city, starting in the north at Santa Croce, but they always ended in the Piazzetta adjacent to San Marco (Bailey 2017, p. 271; Johnson 2000, pp. 445–46; Ruggiero 1994, pp. 177–78; Muir 1981, p. 247). A high scaffold was erected there so that the crowds could see the punishment meted out to criminals who had committed offenses against the state. The columns were important judicial markers, monuments in their own right, but they also served as a screen that spectators could look through out to the lagoon, evoking Venice’s source of wealth and power (Bailey 2017, p. 258; Fenlon 2007, p. 13; Johnson 2000, pp. 447, 449). From the sea, they provided a space like a city gate that led visitors coming to Venice by boat to the entrance of the Basilica of San Marco. Various viewpoints existed for the Piazzetta, then, from which one could see the sea, the Basilica of San Marco and its piazza, and the Ducal Palace. In this space, the doge and the Venetian government controlled the vision of spectators while devising an image of the state through the defining of public spaces and the architectural backdrops for political and civic ritual.

Spoils of war seized during the Fourth Crusade, like the pilastri acritani, pietra del bando, and the head of Carmagnola, were also related to bloody spectacles of execution (Barry 2010, pp. 42, 46, 48; Nelson 2007, pp. 148–51). The pilastri acritani were spoils from the Fourth Crusade and originally formed part of the church of St. Polyeuktos in Constantinople. They now stand immediately in front of the south entrance to San Marco. In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, they served a similar function to the two columns in the Piazzetta, framing the execution of doges (Nelson 2007, p. 148). The pietra del bando, a stump of a large porphyry column, was used to display the heads of Turks after the Battle of Lepanto in 1571 (Nelson 2007, p. 150) (Figure 13). And the porphyry head that sits on the balcony at the south-west corner of San Marco was identified with the condottiere Carmagnola, who was beheaded in 1432. The blood red color of porphyry objects made a clear visual allusion to the gruesome activities taking place in the Piazzetta, and the fragmentation of the ancient objects echoed the dismembered bodies on public display (Barry 2010, p. 48).

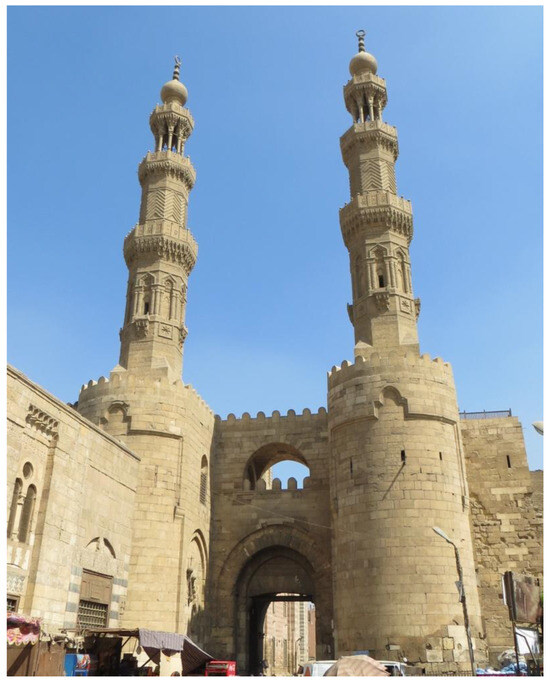

Figure 13.

Venice, Basilica di San Marco, pietra del bando. Photograph by author.

The city gates that defined the boundaries of Fatimid al-Qahira were also sites of public execution and display of criminals in Mamluk Cairo (Figure 14 and Figure 15). Their Fatimid origin made them objects of reuse in the Mamluk period; they were already old and venerable monuments that referenced an Islamic past. Bab Zuwayla, Bab al-Nasr, and Bab al-Futuh were all constructed with spolia, featuring ancient Roman columns at the street level and limestone blocks taken from ancient Egyptian monuments reused in the masonry walls (Al-Nabarawy et al. 2023, pp. 31–32; Williams 2018, pp. 190–91, 243–46). Like the other judicial venues in Venice and Constantinople, monuments that represented imperial authority, political continuity, and cultural accumulation defined places of punishment and execution. Both Bab al-Nasr and Bab Zuwayla were the main sites for displaying the tortured bodies or decapitated heads of traitors and foreign enemies. The heads of defeated adversaries and rebels were paraded through the city with great celebration and then mounted on the city gates; Bab Zuwayla was also used for the hanging of criminals (Williams 2018, pp. 189, 190; Behrens-Abouseif 2014, pp. 77, 81, 83; Stilt 2012, p. 31; Broadbridge 2008, p. 30; Ghaly 2004, pp. 169, 185–86). Bab al-Nasr stood at the northern entrance to the city and criminal bodies exhibited there warned anyone entering the city about committing crimes against the state. Bab Zuwayla is located in the middle of Cairo, marking the transition from the Fatimid royal city and the southern area leading to the Citadel, which was densely packed with Mamluk monuments. Its high visibility and prime location made it the most popular space for the execution of criminals and the display of their dismembered and tortured bodies in Cairo (Behrens-Abouseif 2014, pp. 77–83; Ghaly 2004, p. 185).

Figure 14.

Cairo, Bab al-Nasr. Photograph by Sailko. Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 15.

Cairo, Bab Zuwayla. Photograph by JMCC1. Wikimedia Commons.

Architecture, then, could play a static role as an anchor in the ceremonial cityscape. The permanence of the buildings contrasted with the ephemeral nature of the ceremonies performed in and around them. As such, they were important repositories of memory, marking places and commemorating events. They stood as witnesses to the repetition of ritual acts that recurred over centuries, accruing layers of meaning like the architectural spolia that adorned them. Their monumentality defined space and constructed vision, creating vistas and tableaux to heighten the visual sophistication of events. Buildings provided a rich ornamental backdrop for the theatrical performances that took place in these cities on a regular basis (Johnson 2000, p. 436). They augmented the pomp and magnificence of a royal procession or enhanced the gravity of a public execution through their grandiosity, longevity, and references to history and tradition embedded in their decoration.

Architectural structures called attention to themselves, then, as fixed elements in the urban landscape that you could not ignore. But they were also dynamic actors in the nexus of ceremonial and the built environment, manipulating the way that people interacted with them, the street, and the activities taking place in a city’s public spaces (Manolopoulou 2019, pp. 155–56; Rabbat 2014, p. 37). Their appearance could change as they were dressed up on ritual occasions with textiles, lanterns, and flowers. The function of a monument might shift over time but also according to the ceremony (Manolopoulou 2019, p. 165). The Hippodrome could be a space of triumph or humiliation, city gates could welcome victorious armies and display severed heads of enemies, and religious structures served as loci of both piety and power. Performances staged in and around public architecture transformed physical space as human actors negotiated their relationship with city streets and buildings. Changing sacred and secular itineraries forged new relationships between buildings and people and defined new ritual topographies (Fenlon 2007, pp. 119, 125, 126; 2009, p. 92; 2017, p. 135; Kurtzman 2016, pp. 57, 58, 66; Manolopoulou 2016, p. 211; Glixon 2003, p. 59; Muir 1981, pp. 209, 211). The potential of human interaction with architecture destabilized the permanence and monumentality of these massive stone structures, opening them up to new meanings and significations over time.

7. Conclusions

The nexus of multisensory ritual and spolia-ornamented architecture articulated relationships of power, producing, performing, and maintaining it. Through references to the past and a focus on continuity and tradition, both situated the ruler in a continuum of great empires and civilizations that extended back over centuries if not millennia (Hillsdale 2021, p. 232; Van Steenbergen 2013, p. 243). Time was marked by accretion, where the ruler participating in the ceremonies was the rightful successor to all that came before. Ritual acts performed correctly and mindfully ensured success, bolstered by traditions that highlighted continuity. Tradition was also connected to a sense of place and architectural structures provided a reassuringly concrete manifestation of continuity in their role as ceremonial nodes year after year. The ceremonies performed in a space elevated it above the everyday and the magnificent structures created to accommodate ritual visualized tradition in their longevity and accretive histories. Connections to the past conferred legitimacy, a political tool that could be catalyzed to counter external threats or internal opposition. The ruler appeared to control time and structure it to serve the political needs of the regime (Muir 1981, pp. 231, 241).

The awe-inspiring, wondrous qualities of ceremonial and its spatial setting provided the linchpin that connected people to one another and to the urban environment (Fenlon 2017, pp. 127, 147; Van Steenbergen 2013, p. 254; Georgopoulou 2001, p. 108). Ostentatious display, theatricality, and overwhelming sights, sounds, and smells bolstered the ruler’s status while forging social cohesion and consensus. The magnificent, dramatic structures with their rich ornamentation created an appropriate venue for rituals of state, while the music, pomp, and pageantry enveloped and included everyone, breaking down barriers between ruler and subject, spectator and participant. All the city’s inhabitants were activated in the service of preserving time-honored ceremonies and traditions that, in turn, supported and perpetuated the state. Architecture anchored ritual, giving an ephemeral activity a permanent presence and designating particular areas—Bayn al-Qasrayn, the Citadel, Piazza San Marco, the Hippodrome—as potent spaces of memory, memory that could be invoked by all the senses in the performative cityscapes of Venice, Cairo, and Constantinople (Hillsdale 2021, pp. 229, 230, 259).

Across the Mediterranean, urban performances constituted a shared practice. The confluence of architecture and multisensory ritual created a fertile environment for the exploration of political, social, and cultural concerns. The similarity of ceremonies and spectacles deployed by the Mamluks, Byzantines, and Venetians demonstrates the collective interest in visual and aural kinetic displays that legitimized rulers, concretized social hierarchies, and affirmed the effectiveness of legal systems. A shared Mediterranean repertoire of urban spaces, architectural structures and decoration, and ritual acts provided a common vocabulary from which to forge a distinctive urban ceremonial that supported political regimes and bolstered social consensus for these interconnected polities across the sea.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Akyürek, Engin. 2021. The Hippodrome of Constantinople. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Harithy, Howayda. 2001. The Concept of Space in Mamluk Architecture. Muqarnas 18: 73–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Nabarawy, Raafat Mohamed Mohamed, Shaaban Samir Abdel Razek, and Ahmed Zaki Hassan. 2023. The Fatimid Viziers’ Contributions to the Construction of Historic City Walls and Gates of Cairo (567–358 AH/969–1171 AD). Minia Journal of Tourism and Hospitality Research 15: 28–53. [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson, Niall. 2012. Sonic Armatures: Constructing an Acoustic Regime in Renaissance Florence. The Senses and Society 7: 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, Meryl. 2017. Carrying the Cross in Early Modern Venice. In Space, Place, and Motion: Locating Confraternities in the Late Medieval and Early Modern City. Edited by Diana Bullen Presciutti. Leiden: Brill, pp. 244–69. [Google Scholar]

- Bardill, Jonathan. 2010. Konstantinopolis Hippodromu’nun Anitlari ve Süslemeleri/The Monuments and Decoration of the Hippodrome in Constantinople. In Hippodrom/Atmeydani: Istanbul’un Tarih Sahnesi/Hippodrome/Atmeydani: A Stage for Istanbul’s History. Edited by Brigitte Pitarakis. Istanbul: Pera Müsezi Yayini/Pera Museum Publication, pp. 149–84. [Google Scholar]

- Barry, Fabio. 2010. Disiecta membra: Ranieri Zeno, the Imitation of Constantinople, the Spolia Style, and Justice at San Marco. In San Marco, Byzantium, and the Myths of Venice. Edited by Henry Maguire and Robert Nelson. Washington: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, pp. 7–62. [Google Scholar]

- Bassett, Sarah. 2004. The Urban Image of Late Antique Constantinople. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, Franz Alto. 2001. Urban Space and Ritual: Constantinople in Late Antiquity. Acta ad Archaeologiam et Artium Historiam Pertinentia 15: 27–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrens-Abouseif, Doris. 1989. The Citadel of Cairo: Stage for Mamluk Ceremonial. Annales Islamologiques 24: 25–79. [Google Scholar]

- Behrens-Abouseif, Doris. 2007. Cairo of the Mamluks: A History of the Architecture and its Culture. London: I.B. Tauris. [Google Scholar]

- Behrens-Abouseif, Doris. 2014. Practising Diplomacy in the Mamluk Sultanate: Gifts and Material Culture in the Medieval Islamic World. London: I.B. Tauris. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, Albrecht. 2001. Imperial and Ecclesiastical Processions in Constantinople. In Byzantine Constantinople: Monuments, Topography and Everyday Life. Edited by Nevra Necipoglu. Leiden: Brill, pp. 73–87. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, Albrecht. 2002. Straßen und Plätze in Konstantinopol als Schauplätze von Liturgie. In Bildlichkeit und Bildorte von Liturgie: Schauplätze in Spätantike, Byzanz und Mittelalter. Edited by Rainer Warland. Wiesbaden: Reichert, pp. 9–19. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, Albrecht. 2006. Die akustische Dimension des Kaiserzeremoniells: Gesang, Orgelspiel und Automaten. In Visualisierungen von Herrschaft: Frühmittelalterliche Residenzen Gestalt und Zeremoniell. Edited by Franz Alto Bauer. Istanbul: Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts Istanbul, pp. 63–77. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, Albrecht. 2016. Magical Constantinople: Statues, Legends, and the End of Time. Scandinavian Journal of Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies 2: 9–29. [Google Scholar]

- Boynton, Susan, and Diane Reilly. 2015. Resounding Images: Medieval Intersections of Art, Music, and Sound. Turnhout: Brepols. [Google Scholar]

- Bresc, Henri. 1993. Les entrées royales des Mamlûks: Essai d’approche comparative. In Genèse de l’Etat moderne en Méditerranée: Approches Historique et Anthropologique des Pratiques et des Representations. Rome: École française de Rome, pp. 81–96. [Google Scholar]

- Broadbridge, Anne. 2008. Kingship and Ideology in the Islamic and Mongol Worlds. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brubaker, Leslie. 2018. Space, Place and Culture: Processions across the Mediterranean. In Cross-Cultural Interaction Between Byzantium and the West, 1204–1669: Whose Mediterranean Is It Anyway? Edited by Angeliki Lymberopoulou. London: Routledge, pp. 219–35. [Google Scholar]

- Brubaker, Leslie. 2022. Dancing in the Streets of Byzantine Constantinople. Culture & History Digital Journal 11: e014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brubaker, Leslie, and Chris Wickham. 2021. Processions, Power, and Community Identity: East and West. In Empires and Communities in the Post-Roman and Islamic World, c. 400–1000 CE. Edited by Walter Pohl and Rutger Kramer. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 122–87. [Google Scholar]

- Burkhardt, Stefan. 2013. Court Ceremonies and Rituals of Power in the Latin Empire of Constantinople. In Court Ceremonies and Rituals of Power in Byzantium and the Medieval Mediterranean: Comparative Perspectives. Edited by Alexander Beihammer, Stavroula Constantinou and Maria Parani. Leiden: Brill, pp. 277–90. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron, Averil. 1987. The Construction of Court Ritual: The Byzantine Book of Ceremonies. In Rituals of Royalty: Power and Ceremonial in Traditional Societies. Edited by David Cannadine and Simon Price. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 106–36. [Google Scholar]

- Currie, Gabriela. 2014. Glorious Noise of Empire. In Medieval and Early Modern Performance in the Eastern Mediterranean. Edited by Arzu Öztürkmen and Evelyn Birge Vitz. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 425–49. [Google Scholar]

- Dagron, Gilbert. 2002. Réflexions sur le ceremonial byzantine. Palaeoslavica 10: 26–36. [Google Scholar]

- Dagron, Gilbert. 2003. Emperor and Priest: The Imperial Office in Byzantium. Translated by Jean Birrell. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dagron, Gilbert. 2011. L’Hippodrome de Constantinople: Jeux, peuple et politique. Paris: Gallimard. [Google Scholar]

- Eastmond, Antony. 2004. Art and Identity in Thirteenth-Century Byzantium: Hagia Sophia and the Empire of Trebizond. Aldershot: Ashgate. [Google Scholar]

- El-Cheikh, Nadia Maria. 2004. Byzantium Viewed by the Arabs. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Elsner, Jas. 2012. Material Culture and Ritual: State of the Question. In Architecture of the Sacred: Space, Ritual, and Experience from Classical Greece to Byzantium. Edited by Bonna Wescoat and Robert Ousterhout. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Ergin, Nina. 2008. The Soundscape of Sixteenth-Century Istanbul Mosques: Architecture and Qur’an Recital. Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 67: 204–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ergin, Nina. 2015. ‘Praiseworthy in that Great Multitude was the Silence’: Sound/Silence in the Topkapi Palace, Istanbul. In Resounding Images: Medieval Intersections of Art, Music, and Sound. Edited by Susan Boynton and Diane Reilly. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 109–33. [Google Scholar]

- Featherstone, Jeffrey Michael. 2006. The Great Palace as Reflected in the De Ceremoniis. In Visualisierungen von Herrschaft: Frühmittelalterliche Residenzen Gestalt und Zeremoniell. Edited by Franz Alto Bauer. Istanbul: Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts Istanbul, pp. 47–61. [Google Scholar]

- Fenlon, Iain. 2007. The Ceremonial City: History, Memory and Myth in Renaissance Venice. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fenlon, Iain. 2009. Piazza San Marco. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fenlon, Iain. 2017. Music, Ritual, and Festival: The Ceremonial Life of Venice. In A Companion to Music in Sixteenth-Century Venice. Edited by Katelijne Schiltz. Leiden: Brill, pp. 125–48. [Google Scholar]

- Frenkel, Yehoshua. 2018. Mamluk Soundscape: A Chapter in Sensory History. ASK Working Paper 31: 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Frenkel, Yehoshua. 2019. Embassies and Ambassadors in Mamluk Cairo. In Mamluk Cairo, A Crossroads for Embassies. Edited by Frédéric Bauden and Malika Dekkiche. Leiden: Brill, pp. 238–59. [Google Scholar]

- Georgopoulou, Maria. 2001. Venice’s Mediterranean Colonies: Architecture and Urbanism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ghaly, Dina. 2004. The Sharia al-Azam in Cairo: Its Topography and Architecture in the Mamluk Period. Ph.D. thesis, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Glixon, Jonathan. 2003. Honoring God and the City: Music at the Venetian Confraternities, 1260–1807. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Guberti Bassett, Sarah. 1991. The Antiquities in the Hippodrome of Constantinople. Dumbarton Oaks Papers 45: 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haines-Eitzen, Kim. 2016. Geographies of Silence in Late Antiquity. In Knowing Bodies, Passionate Souls: Sense Perceptions in Byzantium. Edited by Susan Harvey and Margaret Mullett. Washington: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, pp. 111–20. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, Susan, and Margaret Mullett, eds. 2016. Knowing Bodies, Passionate Souls: Sense Perceptions in Byzantium. Washington: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection. [Google Scholar]

- Heher, Dominik. 2015. Heads on Stakes and Rebels on Donkeys: The Use of Public Parades for the Punishment of Usurpers in Byzantium (c. 900–1200). Porphyra 23: 12–20. [Google Scholar]

- Herrin, Judith. 2021. Byzantium: Imperial Order, Constantinopolitan Ceremonial and Pyramids of Power. In Political Culture in the Latin West, Byzantium and the Islamic World, c. 700-c. 1500: A Framework for Comparing Three Spheres. Edited by Catherine Holmes, Jonathan Shepard, Jo van Steenbergen and Jörn Weiler. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 290–329. [Google Scholar]

- Hillsdale, Cecily. 2021. Imperial Monumentalism, Ceremony, and Forms of Pageantry: The Inter-Imperial Obelisk in Istanbul. In The Oxford World History of Empire. Edited by Peter Fibiger Bang, C.A. Bayly and Walter Scheidel. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 223–65. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, Deborah, and Laura Moretti. 2009. Sound and Space in Renaissance Venice: Architecture, Music, and Acoustics. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Illiano, Roberto, ed. 2024. Sound, Music, Architecture. Turnhout: Brepols. [Google Scholar]

- Jeffreys, Elizabeth. 2014. We Need to Talk about Byzantium: Or Byzantium, its reception of the classical world as discussed in current scholarship, and should classicists pay attention? Classical Receptions Journal 6: 158–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, Eugene. 2000. Jacopo Sansovino, Giacomo Torelli, and the Theatricality of the Piazzetta in Venice. Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 59: 436–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaldellis, Anthony. 2016. The Forum of Constantine in Constantinople: What do we know about its original architecture and adornment? Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies 56: 714–39. [Google Scholar]

- Kaldellis, Anthony. 2025. The Forum of Theodosius I in Constantinople: Symbolic Geography and Dynastic Propaganda. In Studies in Byzantine History and Culture: A Festschrift for Paul Magdalino. Edited by Shaun Tougher. Leiden: Brill, pp. 11–24. [Google Scholar]

- Kiousopoulou, Tonia. 2022. L’inscription du pouvoir imperial dans l’espace urbain constantinopolitain à l’époque des Paléologues. In Spatialities of Byzantine Culture from the Human Body to the Universe. Edited by Myrto Veikou and Ingela Nilsson. Leiden: Brill, pp. 358–68. [Google Scholar]

- Kouneni, Lenia. 2025. The Afterlife of a Pagan Hero in a Christian Capital: Antique Sculptures of Hercules in Constantinople. In Studies in Byzantine History and Culture: A Festschrift for Paul Magdalino. Edited by Shaun Tougher. Leiden: Brill, pp. 25–49. [Google Scholar]

- Kurtzman, Jeffrey. 2016. Civic Identity and Civic Glue: Venetian Processions and Ceremonies of the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries. Yale Journal of Music & Religion 2: 49–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liudprand of Cremona. 2007. The Complete Works of Liudprand of Cremona. Edited by Paolo Squatriti. Washington: Catholic University of America Press. [Google Scholar]

- Macaraig, Nina. 2025. Visions, Voices, and Fragrances of the Beyond: Sensory Aspects of Ottoman Tombs. In Studies in Byzantine History and Culture: A Festschrift for Paul Magdalino. Edited by Shaun Tougher. Leiden: Brill, pp. 378–403. [Google Scholar]

- Macrides, Ruth. 2002. Constantinople: The Crusaders’ Gaze. In Travel in the Byzantine World. Edited by Ruth Macrides. Aldershot: Ashgate, pp. 193–212. [Google Scholar]

- Macrides, Ruth. 2011. Ceremonies and the City: The Court in Fourteenth-century Constantinople. In Royal Courts in Dynastic States and Empires: A Global Perspective. Edited by Jeroen Duindam, Tülay Artan and Metin Kunt. Leiden: Brill, pp. 217–35. [Google Scholar]

- Macrides, Ruth. 2013a. Music, Acclamations, Lighting. In Pseudo-Kodinos and the Constantinopolitan Court: Offices and Ceremonies. Edited by Ruth Macrides, J. A. Munitiz and Dimiter Angelov. London: Routledge, pp. 439–44. [Google Scholar]

- Macrides, Ruth. 2013b. The Ceremonies. In Pseudo-Kodinos and the Constantinopolitan Court: Offices and Ceremonies. Edited by Ruth Macrides, J. A. Munitiz and Dimiter Angelov. London: Routledge, pp. 395–437. [Google Scholar]

- Macrides, Ruth. 2013c. The Palace of the Ceremonies. In Pseudo-Kodinos and the Constantinopolitan Court: Offices and Ceremonies. Edited by Ruth Macrides, J. A. Munitiz and Dimiter Angelov. London: Routledge, pp. 367–78. [Google Scholar]

- Macrides, Ruth, J. A. Munitiz, and Dimiter Angelov, eds. 2013. Pseudo-Kodinos and the Constantinopolitan Court: Offices and Ceremonies. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Magdalino, Paul. 2011. Court and Capital in Byzantium. In Royal Courts in Dynastic States and Empires: A Global Perspective. Edited by Jeroen Duindam, Tülay Artan and Metin Kunt. Leiden: Brill, pp. 131–44. [Google Scholar]

- Magdalino, Paul. 2015. The Myth in the Street: The Realities and Perceptions of Pagan Sculptures in Christian Constantinople. In Mythoplasies: Chrisi kai Proslipsi ton Archaion Mython apo tin Archaiotita mechri Simera. Edited by Stephanos Efthymiadis. Athens: Ekdosis, pp. 205–22. [Google Scholar]

- Majeska, George. 1997. The Emperor in His Church: Imperial Ritual in the Church of Hagia Sophia. In Byzantine Court Culture from 829 to 1204. Edited by Henry Maguire. Washington: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Maleon, Bogdan-Petru. 2017. The Torture of Bodies in Byzantium After the Riots (Sec. IV–VIII). In Killing and Being Killed: Bodies in Battle. Edited by Jörg Rogge. Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag, pp. 43–60. [Google Scholar]

- Mango, Cyril. 1963. Antique Statuary and the Byzantine Beholder. Dumbarton Oaks Papers 17: 55–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manolopoulou, Vasiliki. 2016. Processing Constantinople: Understanding the Role of lite in Creating the Sacred Character of the Landscape. Ph.D. dissertation, Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK. [Google Scholar]