From Africa Palace to AfricaMuseum

Abstract

1. Introduction: The Congo: A Belgian Invention

2. Leopold’s Museum

3. AfricaMuseum

How can we create a new exhibition with the same staff who have often been working on these objects for several decades? And what about the interpersonal or interprofessional power relationships that develop between independent experts from diasporas and scientific staff who enjoy a privileged status within the museum institution? Can we really replace the usual relationships of domination and submission with relationships of co-creation under these conditions?.(n.d. p. 7)

4. The Frame of the Museum

5. Counter Narratives

Leopold II as AfricaMuseum

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Lieutenant Théodore Masui was a key individual in the removal of objects from the Congo. He later organized the Congo Free State at the Brussel’s World Fair. |

| 2 | For other academic and critical reviews of the renovation of AfricaMuseum see, among others (Debrauwer 2018; Miller 2019; Wetsi Mpoma n.d.; Hassett 2020; Van Beurden 2021) and the dossier “Decoloniser l’espace publique,” coordinated by BAMKO, which contains a wealth of interviews and articles on the subject. |

| 3 | Leopold’s atrocities in the Congo have been well documented in Vangroenweghe (1986); Friedmann (1992); Hochschild (1998); and (Zana-Etambala 2020, pp. 71–72). |

| 4 | These include the Jubelpark/Park du Cinquantenaire and Memorial Arcade (1852–1880) that was commissioned for the 1880 National Exhibition to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the Belgian Revolution and independence. The complex contains the Royal Museum of the Armed Forces and Military History and the Art & History Museum (formerly the Cinquantenaire Museum). The Monument to the Belgian Pioneers in the Congo was added to the Belgian commemorative landscape to honor the Congo Free State and the Belgian pioneers—soldiers—who brought “civilization” to the Congo. Leopold also financed Antwerp Centraal Station (1895–1905) and the Basilica of the Sacred Heart (begun in 1905), which was established to commemorate the 75th anniversary of the Belgian Revolution. |

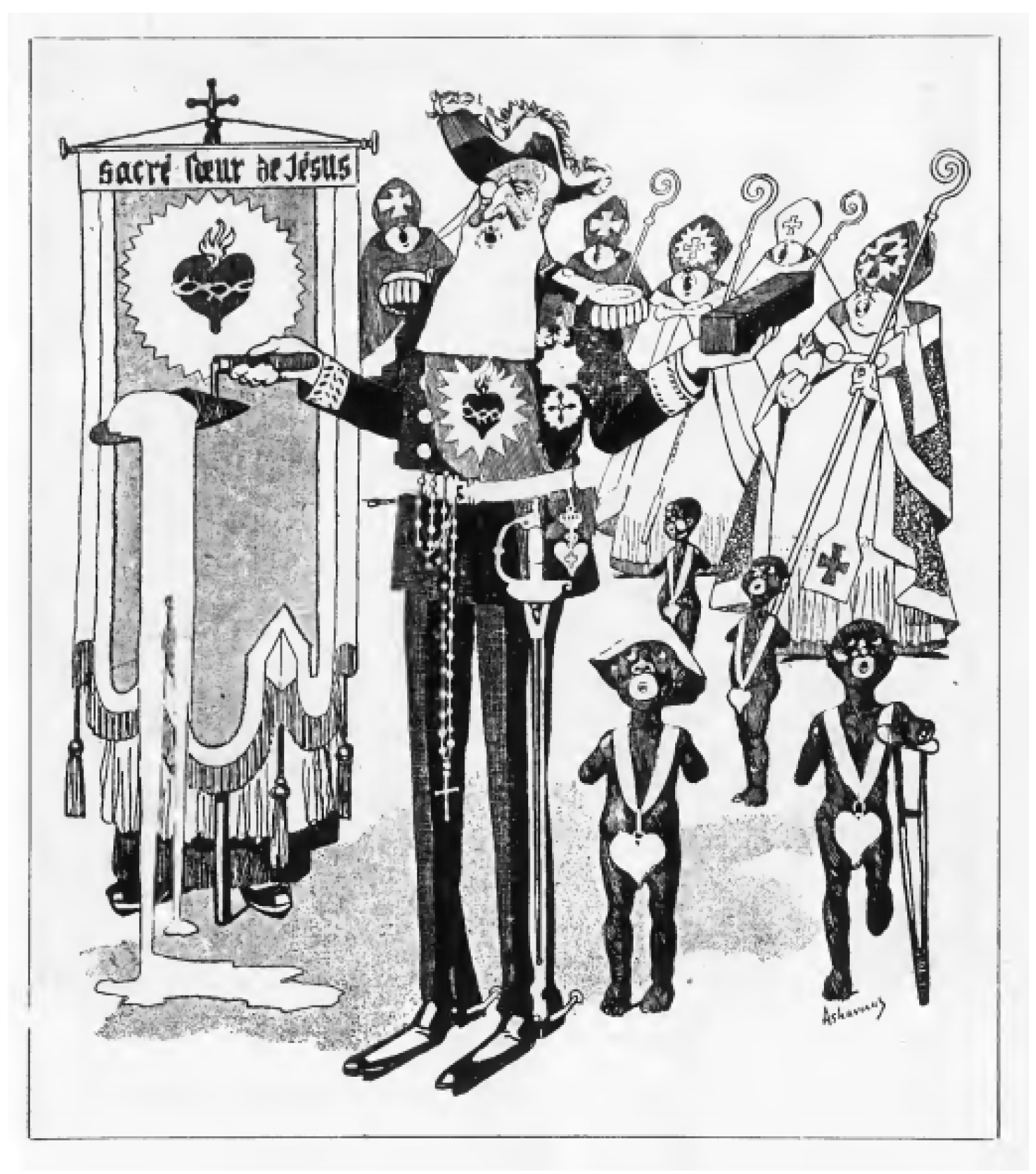

| 5 | Sambourne’s caricature was published the same year as E.D. Morel’s Red Rubber, that exposed the genocidal actions of Leopold II’s Congo Free. After Leopold was forced to sell the Congo Free State to Belgium, he burned the entire archive of the Congo Free State in order to hide his horrific practices. |

| 6 | The relationship between modern aesthetics and imperial power structures is not clear on whether modernism arose from a crisis in colonialism or was a sophisticated from of cultural imperialism itself (Jameson 2016). |

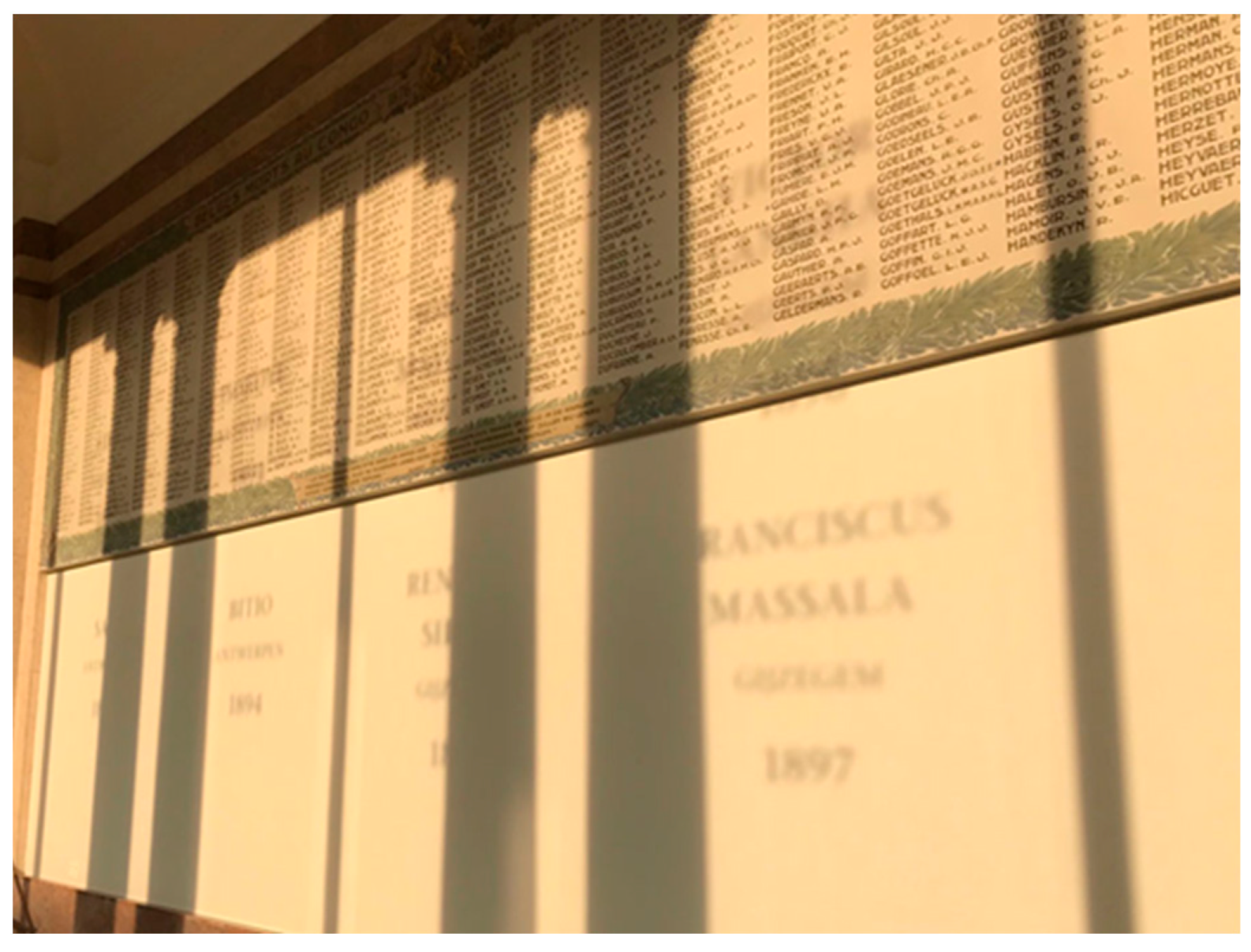

| 7 | Seven of the individuals died of from the cold and wet summer. They were buried in unconsecrated grounds reserved for adulterers and suicides. In 1953, their bodies were moved to St. John the Evangelist cemetery in Tervuren. A ceremony acknowledging their deaths was incorporated into the opening of the renovated AfricaMuseum. |

| 8 | Tony Bennett has addressed the emergence in the 19th century of institutions, such as large public exhibitions, arcaded buildings, art museum, natural history, as ways to mark and transmit message of power. They also serve to underscore the Western perception of disparities between Western nations and non-European civilizations with the former in a superior position and the latter positioned as “primitive peoples” outside history to occupy a zone between “nature and culture” (Bennett 1995). |

| 9 | Prior to 1962, French was the default language of Brussels. After 1962, the names of all institutions are in both French and Dutch. |

| 10 | For the full article see https://www.knack.be/nieuws/africamuseum-naast-een-renovatie-van-het-gebouw-is-er-ook-een-renovatie-van-de-geest-nodig-is/ (accessed 16 November 2025). |

| 11 | |

| 12 | Ciraj Rassool in conversation with Clémentine Deliss, January 2019. |

| 13 | Africamuseum.be. https://www.africamuseum.be/de/about_us/history_renovation (accessed 16 September 2025). |

| 14 | |

| 15 | In 1961, Jean-Baptiste Ntakiyica, the artist’s father, was accused of participating in the assassination of Crown Prince Louis Rwagasore who was recently elected Prime minister of Burundi. Rwagasore was supported by the UPRONA (Unité et progress national), which was opposed to Belgian rule. J-B Ntakiyica was a member of the Belgium supported Burundi Christian Democrat party (PDC), whose own Christian Democrats were in power at the time. J-B Ntakiyica’s execution was the event that prompted Ntakiyica’s family to fell Burundi (Poppe 2015, p. 158). |

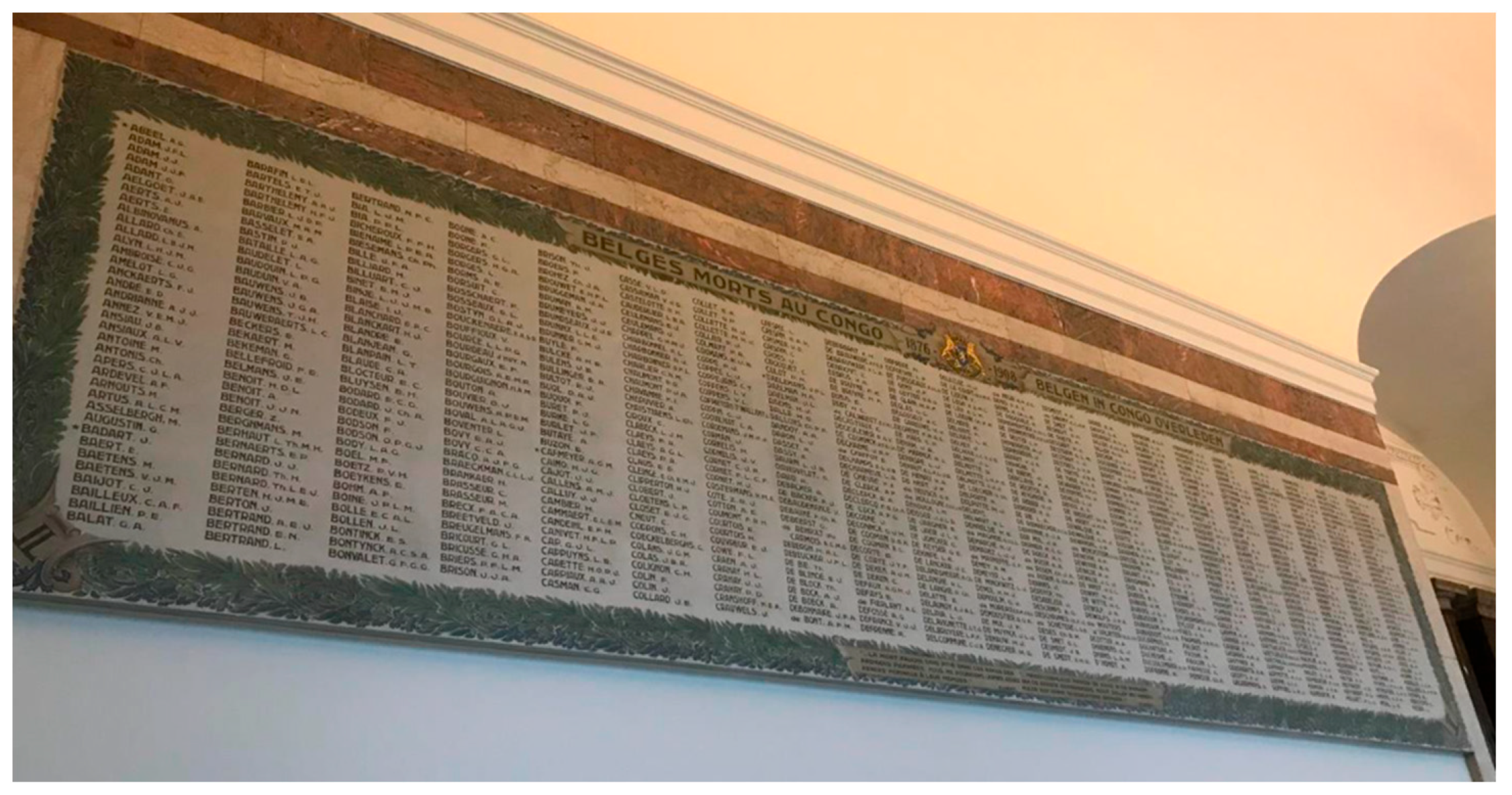

| 16 | The names were compiled by Mathieu Zana Etambala and Maarten Couttenier, two researchers at AfricaMuseum. They include Congolese who were brought to the Antwerp World Exposition in 1894; second, those who were brought to Tervuren during the Colonial Exposition of 1897; and third, those who were brought to the small village of Gijzigem (Sullivan 2020, p. 59). |

| 17 | Sullivan (2020, p. 80). The concept of “nkisi logic” was introduced by B. Jewsiewicki and A. Roberts (Jewsiewicki and Roberts 2023, p. 6). |

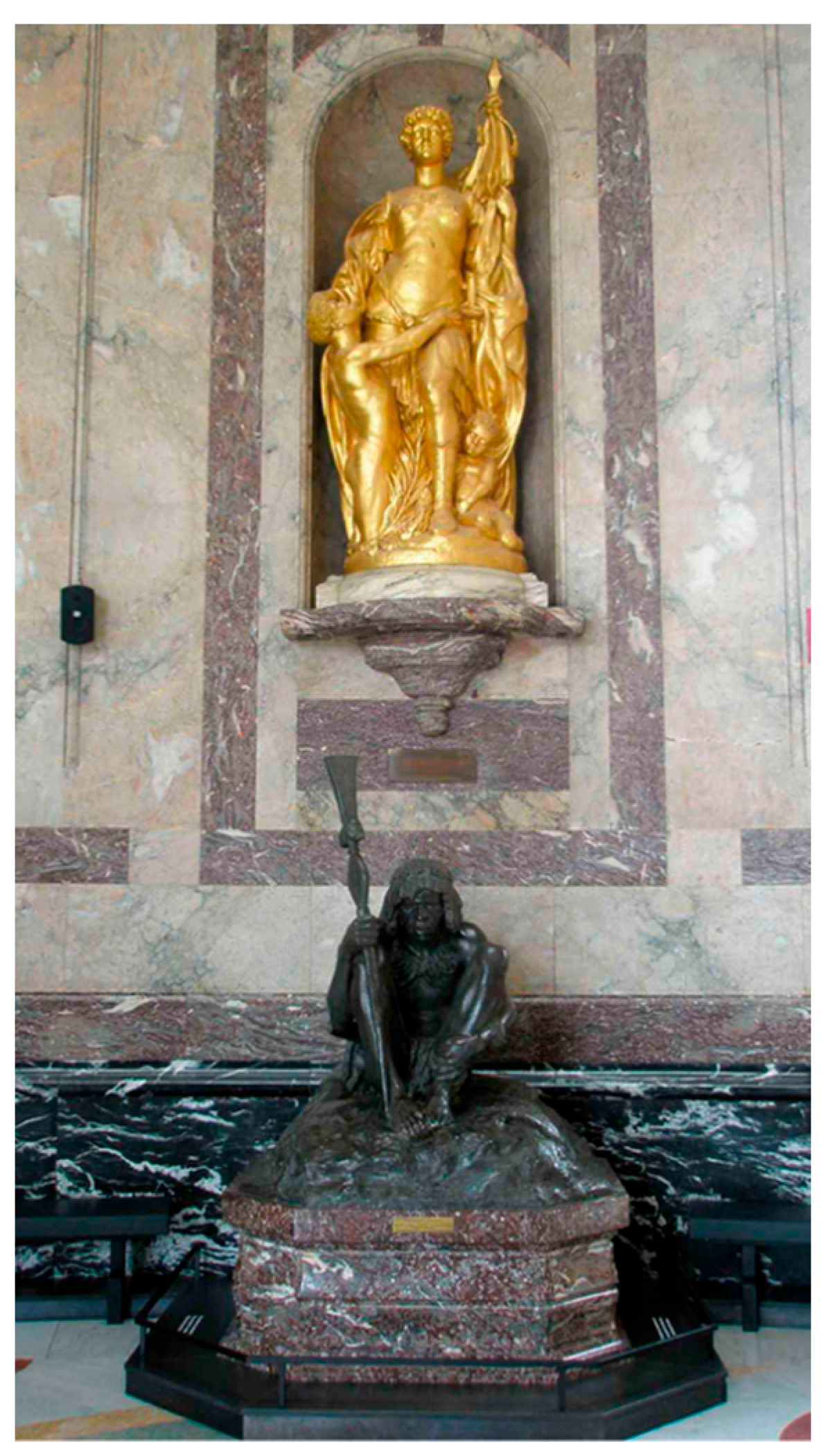

| 18 | Ward worked for the Congo Free State for two years. Many of his sketches and later sculptures were based upon his time in-country. He completed the statues in 1912. Sarita Sanford, Ward’s widow, donated them to the museum in 1930. It is telling when some of these statues were added to the infrastructure of the museum. While the museum was created to highlight Leopold’s Congo Free State, Ward’s statues were added well after The Congo Free State became the Belgian Congo during a period of rising interest in in the colonies. See Stanard (2011, p. 54). |

| 19 | Statement to the media by the United Nations Working Group of Experts on People of African Descent, on the conclusion of its official visit to Belgium, 4–11 February 2019. https://www.ohchr.org/en/statements-and-speeches/2019/02/statement-media-united-nations-working-group-experts-people-african (accessed on 17 July 2015). |

| 20 | The entirety of the project can be found on Müller’s website. https://www.jeanpierremuller.be/re-store (accessed 17 September 2025). |

| 21 | AfricaMuseum hosts HOME: a research project on human remains in Belgian collections on its website. The project addresses the issue of human remains in the collection, which were first raised in the Congo exhibition of 2001. https://www.africamuseum.be/de/research/discover/news/home1 (accessed 17 September 2025); The museum also explains the murder of Chief Lusinga. https://www.africamuseum.be/en/learn/provenance/storms (accessed 17 September 2025). |

| 22 | It is beyond the scope of the article to analyse the very complex juxtapositions between each statue and veil. For more details see Müller’s website. https://www.jeanpierremuller.be/re-store (accessed 20 September 2025). |

| 23 | For details on Mpane’s interest in this language word play, see Sullivan (2020, pp. 157–58). |

| 24 | |

| 25 | https://whitneyplantation.org/history/ (accessed 26 November 2025). |

| 26 | PeoPL was exhibited in Brussels on 6 October 2018 at Nuit Blanche. In Bruno Vergergt open letter [article] in Knack, it appears that Nsengiyumva’s unnamed museum official was Vergergt himself (Vergergt 2018). |

References

- Bennett, Tony. 1995. The Birth of the Museum. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Biney, Ama. 2016. Unveiling White Supremacy in the Academy. Africology: The Journal of Pan African Studies 9: 383–90. [Google Scholar]

- Boast, Robin. 2011. Neocolonial Collaboration: Museum as Contact Zone Revisited. Museum Anthropology 34: 56–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couttenier, Maarten. 2010. No Documents, No History’: The Moral, Political and Historical Sciences Section of the Museum of the Belgian Congo, Tervuren (1910–1948). Museum History Journal 3: 13. [Google Scholar]

- Debrauwer, Lotte. 2018. Ontervredenheid bij Afro[Belgen rond nieuw Africamusem: ‘De renovatie vergeet de essentie’. Knack. October 6. Available online: https://www.knack.be/nieuws/ontevredenheid-bij-afro-belgen-rond-nieuw-afrikamuseum-de-renovatie-vergeet-de-essentie/ (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Deliss, Clémentine. 2021. Walking Through: Thoughts on the Metabolic Practices of Museums. In Alles Vergeht ausser der vergangenheit/Everthing Passes Except the Past: Decolonizing Ethnograohic Museums, Film Archives, and Public Space. London: Geothe Institute, Sterberg Press. [Google Scholar]

- De Wachter, Ellen Mara. 2018. Has Belgium’s Newly Opened Africa Museum Exorcized the Ghosts of its Colonial Past? Frieze. December 11. Available online: https://www.frieze.com/article/has-belgiums-newly-reopened-africa-museum-exorcized-ghosts-its-colonial-past (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- Friedmann, K. Elkholm. 1992. Catastrophe and Creation: The transformation of an African culture. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Haeckel, Jana. 2021. Introduction. In Alles Vergeht ausser der vergangenheit/Everthing Passes Except the Past: Decolonizing Ethnograohic Museums, Film Archives, and Public Space. London: Geothe Institute, Sterberg Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hassett, Dónal. 2020. Acknowledging or Occluding “The System of Violence”?: The Representation of Colonial Pasts and Presents in Belgium’s AfricaMuseum. Journal of Genocide Research 22: 26–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochschild, Adam. 1998. King Leopold’s Ghost. New York: Houghton Mifflin. [Google Scholar]

- Huyse, Luc. 2006. Alles gaat voorbij, behalve het verleden. Amsterdam: van Gennep. Leuven: Van Halewyck. [Google Scholar]

- Jameson, Fredric. 2016. The Modernist Papers. London: Verso Books. [Google Scholar]

- Jewsiewicki, Bogumil, and Allen Roberts. 2023. Exploring Present Pasts: Popular Arts as Historical Studies. In Oxford Encyclopedia of African History. Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Limond-Mertes, Arnaud. 2019. Un espace de démonstration du “génie du colonialism. Interview with Elikia M’Bokolo. Ensemble! 99: 49–55. [Google Scholar]

- Lonetree, Amy. 2009. Museums as Sites of Decolonization; Truth Telling in National and Tribal Museums. In Contesting Knowledge: Museums and Indigenous Perspectives. Edited by Susan Sleeper-Smith. London: University of Nebraska Press, pp. 322–38. [Google Scholar]

- Luntumbue, Muteba T. 2015. Rénovation au Musée de Tervuren: Questions, défis et perspectives. L’Art Même 65: 15–17. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, Donata. 2019. ‘Everything passes, except the past’: Reviewing the renovated Royal Museum of Central Africa (RMCA). Science Museum Group Journal 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nora, Pierre. 1989. Between Memory and History: Les Lieux de Mémoire. Representations 26: 7–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nsengiyumva, Laura. n.d. The Day When I (Almost) Melted (Your Father). The challenged of the Working Group of Decolonisation. Eye-to-Eye. Available online: https://eye-to-eye.online/laura-nsengiyumva/ (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Okwunodu Ogbechi, S. 2014. Transcultural Interpretation and the Production of Alterity: Photography, Materiality, and Mediation in the Making of “African Art”. In Art History and Fetishism Abroad. Edited by Gabrielle Genge and Angela Stercken. Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag, pp. 71–90. [Google Scholar]

- Poppe, Guy. 2015. The murder of Burundi’s prime minister, Louis Rwagasore. Afrika Focus 28: 156–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, Barbara. 2005. Congo-Vision. In Science, Magic and Religion: The Ritual Processes of Museum Magic. Edited by Mary Bouquet and Nuno Porto. New York: Berghahn Books, pp. 75–115. [Google Scholar]

- Schouteden, H. 1942. Guide illustré du Musée du Congo belge. Tervuren: Museum of the Belgian Congo, pp. 33–34. [Google Scholar]

- Shelby, Karen. 2014. Flemish Nationalism and The Great War. New York: MacMillan. [Google Scholar]

- Shelby, Karen. 2017. Belgian Museums of the Great War: Politics, Memory, and Commerce. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman, Debra. 2011. Art Nouveau, Art of Darkness: African Lineages of Belgian Modernism, Part I. West 86th: A Journal of Decorative Arts, Design History, and Material Culture 18: 139–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanard, Matthew. 2011. Selling the Congo: A History of European Pro-Empire Propaganda and the Making of Belgian Imperialism. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stanard, Matthew. 2017. ‘Boom! Goes the Congo’: The rhetoric of control and Belgium’s late colonial state. In Rhetorics of Empire: Languages of Colonial Conflict after 1900. Edited by Martin Thomas and Richard Toye. Manchester: Manchester University Press, pp. 121–41. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan, Elaine. 2020. Petit á Petit: Contemporary Art in Decolonial Horizons in Belgian’s Africamuseum. Ph.D. dissertation, University of California, California, LA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Tansia, Tracy. 2019. Changing the narratives in renovating the AfricaMuseum. A conversation with Gillian Mathys, Margot Luyckfasseel, Sarah Van Beurden, Tracy Tansia. Africa Is a Country. April 29. Available online: https://africasacountry.com/2019/04/renovating-the-africamuseum (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Van Beurden, Sarah. 2021. Museums, Exhibitions, and Monuments: Congo in the Belgian Public Sphere. Brussels: UGent for the Chambre des représentants de Belgique. [Google Scholar]

- Vangroenweghe, Daniel. 1986. Du sang sure les lianes. Léopold II et son Congo. Paris: Didier Hautier Publisher. [Google Scholar]

- Vanhee, Hein. 2016. On Shared Heritage and Its (False) Promises. African Arts 49: 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergergt, B. 2018. AfricaMuseum: ‘Naast een renovatie het gebouw, is er ook een renovatie van de geest nodig is’. Knack. October 11. Available online: https://www.knack.be/nieuws/africamuseum-naast-een-renovatie-van-het-gebouw-is-er-ook-een-renovatie-van-de-geest-nodig-is/ (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Wastiau, Bruno. 2000. ExitCongoMuseum. Tervuren: Royal Museum for Central Africa. [Google Scholar]

- Wetsi Mpoma, Anne. n.d. Quand le temple dédié à la colonisation belge fait peau neuve. Bruxelles: BAMKO ASBL.

- Zana-Etambala, Mathieu. 2020. Veroverd, bezet, gekoloniseerd. Gorredijk: Sterk & De Vreese, pp. 71–72. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shelby, K. From Africa Palace to AfricaMuseum. Arts 2025, 14, 168. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts14060168

Shelby K. From Africa Palace to AfricaMuseum. Arts. 2025; 14(6):168. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts14060168

Chicago/Turabian StyleShelby, Karen. 2025. "From Africa Palace to AfricaMuseum" Arts 14, no. 6: 168. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts14060168

APA StyleShelby, K. (2025). From Africa Palace to AfricaMuseum. Arts, 14(6), 168. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts14060168