Abstract

Similar to the Russian historical avant-garde of the 1910s, which predicted the war and the social revolution of 1917, the late avant-garde of the 1920s anticipated the advent of the totalitarian terror and the Stalinist repressions of the 1930s. In figurative painting, this manifested itself in a specific visual “lexicon” and modality (bodily violence and the fragmented body, frustration, motifs of loss, death and general catastrophe), as well as in the expressive style (that inherited but not duplicated the models of European expressionism). In addition to proposing an analytical classification of semantics and poetics of the painting of the 1920s, the present article discusses the issue of the representation of political power in visual art and the presence of archaic roots in the corpus patiens (lat.) motifs. It examines artefacts made by eminent as well as little-known painters of the late avant-garde, including Kazimir Malevich, Alexander Tyshler, Kliment Redko, Georgy Rublev, Aleksandr Drevin, Boris Golopolosov and others.

1. Introduction: Art as a Foreteller

Hegel’s formula according to which art reflects life was in a simplified and perverted way hammered into the consciousness of the Soviet mass viewer from the 1930s, yet, in the very same years, it was refuted by the practice of the fine arts or, more specifically, their alternative trends in relation to the mainstream ideology. As one knows, text extends the meanings that it originally contained as the space and time of its functioning in culture expands (Toporov 1983). The text’s functions expand as well. The prognostic function of art comes to the fore in crucial historical epochs and times of social bifurcation. Fortune tellers, predictors of the future, and prophets meet with great demand in a society that seeks to get rid of the disturbing feeling of uncertainty about the future or at least to reduce its frustration. Art also acquires the function of anticipation–no matter whether the artists themselves are aware of it or not. In the history of literature, cinema and painting, one finds many cases of the anticipation of future events, both at the global historical scale and at the level of the life of individuals. The most striking textbook example is the date of the 20th-century Russian revolution that was predicted by Velimir Khlebnikov (whom Mayakovsky did not believe and mistakenly corrected the date in one of his poems: “The sixteenth year is coming in the crown of thorns of revolutions”). Khlebnikov deliberately looked for numerical patterns in historical chronology. At the same time, in certain Hollywood movies (Armageddon, 1998, dir. Michael Bay; Escape from New York, 1993, dir. John Carpenter; and others), the events of 11 September 2001—the collapse of the Twin Towers in New York—are foreshadowed not as an established law of time or as a mystical coincidence but as a real prophecy. Trends in art are also endowed with a prophetic gift: Russian symbolism of the turn of the 20th century, both in literature and in the fine arts, is imbued with a premonition of a civilizational catastrophe, as if foreseeing the collapse of Russian pre-revolutionary culture. The texts of Andrey Bely and Aleksandr Blok are full of vague allusions and gloomy predictions. The avant-garde—not only the historical avant-garde in Russia, but also Italian futurism and the early German expressionism—foresaw the horrors of the First World War: a blown-up world appeared in painting as fragmented polyhedrons, deviant corporeality, the attack of machines on the living organs of the human body, and borderline mental states. The meanings of Kazimir Malevich’s famous “Black Square” are saturated with a general sense of catastrophe which lowered the curtain on the stage of European art history while outlining a broader context-a premonition of the decline of Russian culture. Thinking about the future, writers voluntarily or involuntarily surmised the outlines of the coming totalitarian era in anti-utopias—whether German Nazism in Karel Capek’s novel The War with the Newts written in 1936 or contemporary events in Russia in Vladimir Sorokin’s story “The Day of the Oprichnik” written in 2006. The exposure of a social project doomed to failure in Andrey Platonov’s story “Foundation Pit” (written in 1930, first published in 1968) can be regarded in the same line. Although the genre of dystopia itself is still a by-product of the prognostic function, it is not so much about a critical look at modernity and its near future as about a kind of registration using the special sensory sensitivity of art of the seismic vibrations of upcoming social earthquakes. At the same time George Orwell’s dystopic novel Nineteen Eighty-Four written in 1948 demonstrated amazing insight into the Eastern European regimes that were to be established after the Second World War. The features of the carnival of death sweeping the world—the recent pandemic—can also be seen in the prophetic movie Joker (2019, dir. Todd Phillips). I should also mention personal foreseeing: Mikhail Vrubel predicted the death of his son, and Van Gogh—his own death. These are just a few examples.

Let me now turn to a phenomenon of this kind that is less obvious yet all the more revealing—the way in which Soviet paintings of the late 1920s and the early 1930s manifested a premonition of the onset of the repressive Stalinist regime. This took place mainly in the unofficial art of this time, which came to the attention of the broad public only in recent decades: a lot of paintings gathered dust in the funds of museums or the attics of collectors, while many others were destroyed during the Stalinist period during mass arrests or the self-censorship of their authors. This period has been widely discussed in recent decades, and a lot has been written about its artistic atmosphere and paintings. The most important information is found in Olga Roytenberg’s book Did someone really remember that we had been … (Roytenberg 2004), which provides an essential introduction to the little-known aspects of the art of that era. Individual topics in the history of painting of the 1920s and the connection between semantics and formal stylistic practices are the subject of studies by the art historians Aleksandra Salienko (Salienko 2018), Sergey Fofanov (Fofanov 2019), Anatoly Morozov, me (Nataliya Zlydneva) and others. Significant issues of the historical avant-garde were raised by Boris Groys (Groys 1988) and in a book edited by Hans Guenther and Evgeny Dobrenko dedicated to the problems of socialist realism in a wide ideological and esthetic context (Guenther and Dobrenko 2000). The approach proposed in the present article to the late Soviet avant-garde as an art that was aloof from the main paths of development-industrial art, constructivism, etc.—has not been considered before and much remains to be clarified on this issue. The prognostic functions of painting of this period leads me to formulate some more general questions: the problem of the modality of the image, i.e., of the conveyance of emotions by non-verbal means, and the problem of identifying the level of visual “text” at which a social theme manifests itself in the form of the collective unconscious. A significant aspect of corpus patiens motifs deals with the proportions of subjectivity and objectivity in a visual communication. Bodily suffering can be presented as the object of a mimetic narrative, yet it can also have a subjective model which is wholly determined by the level/plane of expression (the motion of the pictorial mass, contrasting colour, swirling composition, etc.). Most often there is a correlation between the object and the subject of representation that increases the degree of semiotization of the visual text in which the social context and the ideological code of the epoque becomes more perceptible.

2. Radical Shift in the Late Russian Avant-Garde

The generation that entered the artistic arena at the end of the 1920s received an impulse from the artists of the historical avant-garde of the 1910s, from whom they learned in one form or another. Many of the younger artists began with non-objective painting and subsequently retained a commitment to the problems of pure form in their mature years; Sergey Luchishkin, Kliment Redko, Aleksandr Tyshler and others practiced non-objective painting in the beginning of the 1920s. However, these artists, along with many of their colleagues from different artistic associations (“OST” and the others), soon turned to figurative painting, narrative and symbolic compositions or genre scenes. Meanwhile, these figurative plots had little in common with the art of the pre-avant-garde period and even less with the mimetic tradition of the 19th century. While the art of the generation of the 1920s stood on the shoulders of the historical avant-garde and retained a taste for radical experiment, their radicalism shifted from form to motif, projecting the level/plane of expression onto the level/plane of content. This turn manifested itself, in particular, in the fact that the narratives of the paintings began to be saturated with negative topics. The motifs of bodily suffering and violence (hunger, disability, torture of the flesh) and physical withering (the themes of old age and death) swept over many of the new figurative works. Cases in point include The Invalids of War by Yury Pimenov (1926), the numerous images of dead birds in works by Vladimir Sokolov, the Makhnovshchina series of paintings by Aleksandr Tyshler (1920s), Eva Levina-Rosengolts’ Old Men, Sergey Luchishkin’s Famine on the Volga River (1925, destroyed), Pavel Korin’s The Beggar (1933) and many other paintings.

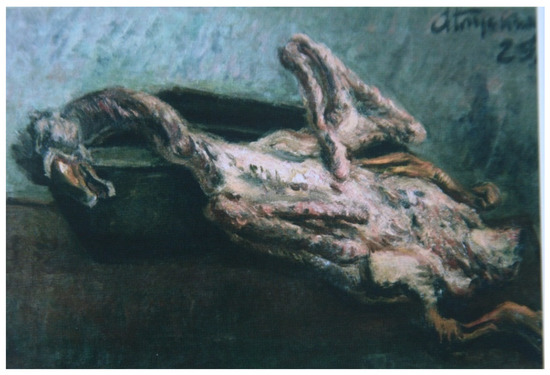

The emphasis shifted from the spatial and coloristic arrangement of the canvas to accentuated modality. Bodily suffering was often conveyed either in terms of the emotional state of the subject or as a representation of the appropriate object. For example, Aleksandr Gluskin’s painting The Tragedy of the Goose (1929, see Figure 1) tries less to expose the theme of a slain bird with a wide range of connotations that are verbally supported by the title (it is no coincidence that the motif coincides, also compositionally, with Goya’s late canvas) than to depict a state unfolded in time. Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin’s Death of the Commissar (1928), on the contrary, shows the physical death of a human being through a spherical perspective that transposes time into space, turning the psychological state into an object constituting a sort of epic mode of communication and eliminating the corpus patiens topic as such. The subjectivity of representation is also introduced with the help of predicates in the title (Boris Golopolosov’s A Man Beating his Head against the Wall, 1938, or S. Luchishkin’s The Balloon Flew Away, 1926).

Figure 1.

A. Gluskin. The Tragedy of the Goose. 1929.

The state of anxiety, fear, horror as well as the foreboding of catastrophe, which is especially important for our study, spread over the entire field of visual discourse in the late 1920s. To a certain extent, this turn in painting was due to the wave of interest in the heritage of symbolism that came into evidence during those years. Memories of symbolism served as a sort of antiphase with respect to the historical avant-garde of the 1910s. As the programmatic work of Russian symbolist painting, Leon Bakst’s Terror Antiquus (1907) contained the whole gamut of expectations of catastrophe, as brilliantly shown in the famous essay written in 1909 by Vyacheslav I. Ivanov ([1909] 1979). Many works of the late 1920s are in consonance with the theme of this painting. However, can this kind of emotional gamut be explained only by the turn to symbolism?

3. Fear in Literature and Art of the 1920–1930s

In the late 1920s, the atmosphere in Russia was largely saturated with a feeling of fear. In literature, the motif of fear is particularly evident. It suffices to mention Leonid Lipavsky and his book The Study of Horror, Daniil Kharms with his old women falling out of the window and Petrov disappearing into the forest, and the different phobias and horrors in the works of Yury Olesha, Mikhail Zoshchenko, Mikhail Bulgakov and Vsevolod Ivanov to evoke a whole cavalcade of forms and ways of representing the impending terrible in verbal artistic expression. We should also mention the tragicomic play Suicide by Nikolay Erdman (1928), which Meyerhold intended to stage but failed to do so on account of pressure from the authorities. Aleksandr Afinogenov’s play Fear (1931) directly asserted that the state indicated in the title was one of the determining factors of human life: the playwright said through one of his characters, “We live in an era of great fear.” As to painting, it reacted to the waves of fear in its own way (Zlydneva 2009).

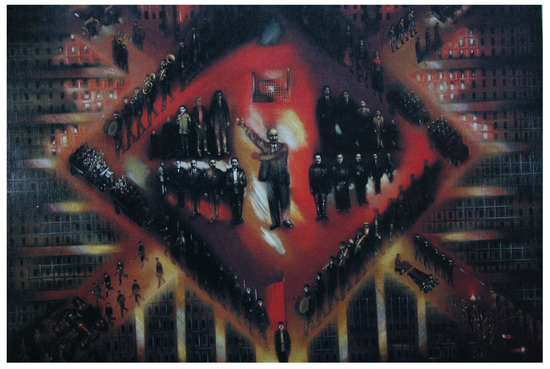

In 1925, Kliment Redko painted his picture Revolt (see Figure 2). The appearance of this work was extremely significant from the point of view of the overall artistic climate of the 1920s. It is strictly symmetrical, almost constructivist, composition that combines geometric conventionality and narrative plot is structured by the central division in the shape of a rhombus. A group of revolutionaries with the gesticulating figure of Lenin in the centre are depicted inside the rhombus. Numerous associates are located around the communist leader along the model of a group photograph: the viewer can easily recognize Trotsky, Stalin, Krupskaya, Mikoyan, and other leading figures of the communist revolution. Extended processions of rebellious masses stretch out along the edges of the rhombus, preparing for a battle: workers, militiamen, warriors and band members holding weapons, carrying wind instruments and dragging carts with provisions. Outside the rhombus, numerous dark walls are blazing with red flames and projecting rays of light. Covered by windows, these walls resemble either prison façades or apocalyptic honeycombs. A very gloomy feeling of catastrophe is conveyed by the ornament of these honeycomb windows immersed in the darkness. The motif of violence as a sort of order resonates with the ideas of Michel Foucault (Foucault 1977). The atmosphere is also enhanced by the unnatural exaltation of the leader’s posture (the iconographical canon of Lenin had not yet been standardized by 1925) and the intensity of the gloomy colouring. The feeling of horror is partly due to the memory of culture in the form of an appeal to traditional iconography: such diamond-shaped forms were used in the Saviour in Power composition in which Christ administers the Last Judgment. Having received an artistic education in the icon-painting workshops of Kyiv, K. Redko could not fail to realize this connection. However, it is impossible to assume that the artist deliberately used this Gospel motif in his composition to demonstrate a social catastrophe: the painting was not perceived by contemporaries in a tragic mode, as evidenced by the fact that it was successfully presented at an exhibition of revolutionary art in Moscow in 1926 without receiving negative assessments from official critics. Nevertheless, the present-day viewer who is aware of the onset of the repressive regime a few years later inevitably sees a prognostic element in this message, which vividly brings across the emotional state of the collective unconscious at the time.

Figure 2.

K. Redko. Revolt. 1925.

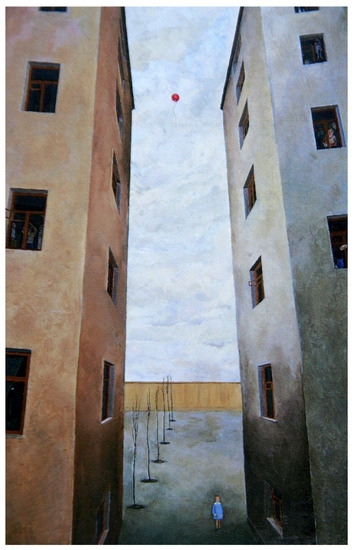

The motifs of loss and existential crisis are already quite consciously broadcast in the painting of S. Luchishkin The Balloon Flew Away (1926, see Figure 3). The anecdotal plot and its infantile intonation grow into a life tragedy thanks to the expressive composition: two towering walls of apartment buildings form a narrow well, spatially rushing upwards towards heaven; in the windows you can see the ant-like life of the inhabitants and, on one of the upper floors, a person who has hanged himself. The latter detail leads to a negative interpretation of the whole narrative, which becomes especially obvious when one considers that the painter almost literally duplicated the engraving of the German expressionist George Grosz (1917), borrowing its composition and even the person who committed suicide. The quotation of Luchishkin’s painting should hardly be interpreted as simple plagiary: the emotional density of the narrative is enhanced by eliciting a socially critical component of German expressionism. Considering how close the ties between Russia and Germany were at that time, there is no doubt that the artist was well acquainted with the work of George Grosz. We also find narrative and compositional echoes between B. Golopolosov’s painting Revolt (1927) and G. Grosz’s painting Metropolis (1917): the centre of the composition is accentuated by a sharp wedge that, as if in protest, cuts into a world immersed in chaos and excesses (observation made by Zaretskaya 2019).

Figure 3.

S. Luchishkin. The Balloon Flew Away. 1926.

4. Archaic Stereotypes

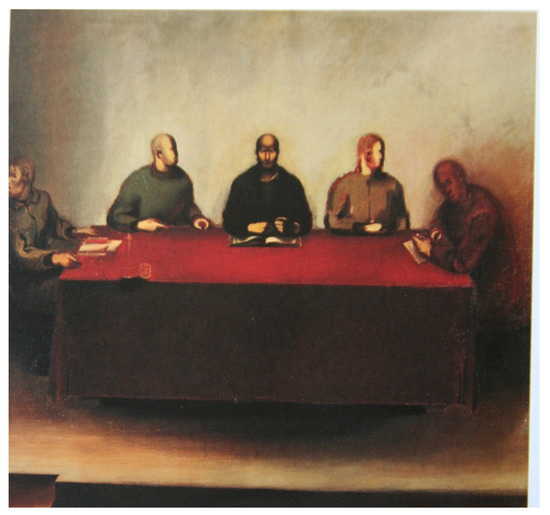

The ambivalence of K. Redko’s canvas Revolt, in which the heroics of the revolution are intertwined with apocalyptic foresight, and the existential motifs of loss and despair in Luchishkin’s painting The Balloon Flew Away can be considered as signs of direct alarm. Meanwhile, the discourse of power that becomes increasingly repressive manifested itself in a number of pictorial practices indirectly, as if on the sly, which made it sound only stronger. I am referring to archaic stereotypes that emerged in the compositional schemes of a number of works. Two of them are of particular significance. The first is a group of images showing various kinds of meetings—from work to Komsomol or party meetings. Compositions of this kind became widespread and can hardly be explained simply by the new realities of Soviet social life—ideological collective events or imitation of public control. Pictures of this kind represent people (bodily mass and/or side-by-side figures) gathered around a speaker or leader at a table parallel to the surface of the canvas. Such a scheme undoubtedly goes back to Leonardo’s fresco The Last Supper, which established the iconographic canon in European art for many centuries. The visual rhetoric of Leonardo’s work can be recognized in the poses and gestures of the characters in many works by Soviet artists: Samuil Adlivankin’s Liquidating the Breakthrough (1930), Vasiliy Tochilkin’s Meeting of the Industrial Party (1931), Nikolay Schneider’s Trial of the Truant (1932) and some others. The supposedly unconscious appeal to this visual stereotype has a deep and clear connotation—the premonition of impending catastrophe that was imprinted in the memory of culture. However, in the painting by Solomon Nikritin Judgment of the People (1934, see Figure 4) based on a similar compositional scheme (“comrades” sitting at a table), the allegory hardly appears in hidden form: the realistically presented scene of a repressive trial came true in a few years.

Figure 4.

S. Nikritin. Judgment of the People. 1934.

Other signs of hidden stereotypes are found in the widespread dual images of this period. In some cases, the paired compositions are motivated by the plot—for example, the paired portraits of a couple: Fiodor Bogorodsky’s In the Photo Studio (1932) and K. Petrov-Vodkin’s Spring (1935). However, quite often there is no motivation, such as in the paintings by Boris Ermolaev Red Navy sailors (1934), Ivan Mashkov The Lady in Blue (1927), and Pavel Filonov The Raider (1926–1928). Doubling is characteristic of the compositions of K. Petrov-Vodkin’s earlier period (Two Boys, 1916). The twin images link to the cult of sacred twins evoking the ancient cultural archetype of supreme power and highest social status; in archaic societies, twins served for predicting the future (Ivanov 2009). It is significant that this prefiguration of movement towards absolute power led a few years later to the emergence of the famous twin portrait by Aleksandr Gerasimov of Stalin and Voroshilov against the background of the Kremlin, which gave rise to the meme Two Leaders after the Rain (1938).

5. Discourse of Power: Gesture and Motion

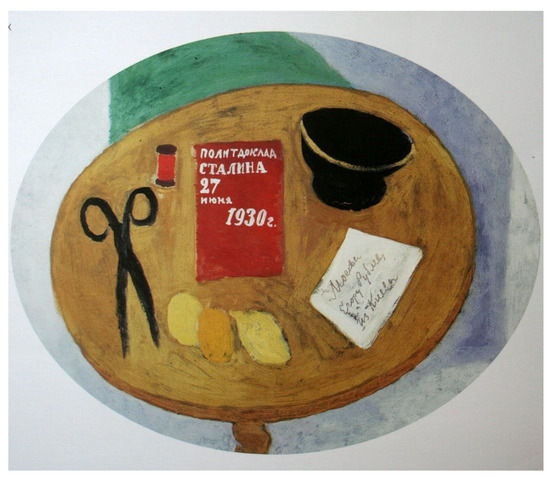

Hidden symbols of power such as the onset of an era of violence can also be discerned in Georgy Rublev’s still life The Letter from Kyiv (1929, see Figure 5). Painted in a primitive style the image shows a table viewed from above; there are a number of things on the table—a cup and saucer, a couple of lemons, a skein of thread, a brochure and an unopened envelope. From the inscriptions made in clumsy handwriting, one sees that the brochure contains Stalin’s speech at a party congress, while the letter was sent from Kyiv and addressed to the author of the picture himself—“Yegor Rublev”. If one takes into account that Kyiv was G. Rublev’s hometown, this detail resembles an index sign of an auto-referential message. However, there is one more item on the table—huge tailor’s scissors that stand out through their size and a thick black contour that visually resonates with the black letters of the inscriptions. This attribute of tailoring is a frequent “character” in Rublev’s paintings representing sewing workshops. However, on this canvas this detail is not motivated by the narrative in any way and looks more like an instrument of torture than a household appliance. The composition as a whole resembles a children’s puzzle where the combination of simple signs of everyday life, the brochure as an ideological resonator and the envelope as a sign of self-communication, as well as the scissors as a piercing and cutting tool (an unclearly articulated yet very formidable symbol of violence) add up to a single syntagma, a single vague dark message. It is worth noting that one year later the scissors reappeared on Rublev’s canvas in a transformed form—their shape can be distinguished in a portrait of Stalin, in the outlines of the leader’s eyebrows and nose, highlighted by the same thick, black and curved line (Stalin Reading the Newspaper ‘Pravda’, 1930). It is unlikely that the artist employed this cross-textual visual rhyme consciously in this case, it is clearly more appropriate to talk about a discourse of power and perceived threat spread over the entire field of artistic practices and manifested (regardless of the author’s intention) in the emphasis of details.

Figure 5.

G. Rublev. The Letter from Kyiv. 1929.

In a more explicit way, the discourse of power can be detected in the system of gestures of depicted characters. The waving arms, resembling the hands of a dial, of the figure of Lenin in Redko’s above-mentioned painting Revolt are symptomatic. Imaging gestures actively flooded into painting from the mid-1920s and performed a variety of functions. Gestures in paintings echo the speech of natural language and iconically convey a message, raising its semiotic status. There are gestures of indefinite meaning that represent homo loquens (narrator) or homo ambulans (walking man) and have a mimetic purpose, i.e., to expand and corroborate a narrative. There also exists an arbitrary group of gestures aimed at describing modality: they convey emotion in a wide range of psychological states. Codified gestures form a special group: the gesture of a traffic controller, the gesture of finger pointing and-especially interesting for us—the gesture of a speaker. During this period, the central model of gesticulating characters is the model of a speaking person—a tribune (homo loquens)—which goes back to the antique motif of the oratory emperor. A final chord in this series of images is a multi-figured canvas by Konstantin Yuon There is such a party! (1934), in which a figurine of Lenin with an outstretched arm, barely visible in the multi-figure group of characters, prefigures the canonical pose in the visual representation of the leader for many decades to come. This gesture of the leader of the revolution is symbolically strengthened verbally by means of the title that conveys the legitimating slogan of the Bolshevik coup.

By this time, the iconography of Lenin as a tribune addressing a crowd of adherents had already existed for more than 10 years in propaganda posters, paintings and sculptures of the post-revolutionary period. One should mention posters by Gustav Klutsis and Vladimir Shcherbakov, the painting by Isaak Brodsky Lenin’s Speech at the Putilov Factory in 1917 (1927), the monument to Lenin by Sergey Evseev and Vladimir Shchuko at the Finland Station (1925) and many others. During these years, a book entitled Gesture in Art was written by the famous art critic and staff member of the State Academy of Artistic Sciences Nikolai Tarabukin (Tarabukin 1929, still not published, the work exists in two typewritten manuscripts at the Russian State Library). According to Tarabukin, the gesture is “the external expression of an internal necessity” (p. 33), and its main property is its intentionality. The gesture acts as a function of the will (“strong-willed striving towards danger–gesture”, p. 358), which, obviously, goes back to German formalism, to Alois Riegl’s concept of Kunstwollen, as well as to Friedrich Nietzsche’s will, a motif that permeates all modernist art. Among Tarabukin’s colleagues at the State Academy of Artistic Sciences (GAKhN), A. Gabrichevsky also used the category of will in connection with the concepts of internal motion and formation, asserting that time is an integral property of artistic form and acts in tandem with space. Motion was an important subject of research at the State Academy of Artistic Sciences (Laboratory of Choreology, Section of Cinematography-Aleksey Sidorov) and the Central Institute of Labour (Aleksey Gastev). Nikolay Tarabukin also wrote the article “Motion” for the Dictionary of Artistic Terms that was prepared at the State Academy of Artistic Sciences (Tarabukin 2005). As a signifier whose signified is movement, the gesture for Tarabukin is charged with the tension of antinomy: “[Its] synthetic resolution is obtained in form <…> which by its nature is inevitably a form of becoming” (Tarabukin 1929, p. 123). In other words, “gesture <…> is a contradiction resolved in unity and <…> is considered by us as a category of becoming” (p. 125). According to Tarabukin, the function of the gesture is to make visible something that lies beyond the visible: “to make an invisible disturbance visible” (pp. 135–36).

Motion as a semantic category of artistic representation also occupied Tarabukin a few years earlier when he was writing his article on diagonal compositions in painting (published in: Tarabukin 1973). In the case of homo loquens discussed above, the diagonal composition of the speaker/leader’s outstretched hand gives dynamism to the figure. This dynamism semioticizes the concept of life as the will to what is beyond the visible, as an invisible excitement.

6. Running Man: Motion in Expressionism as Prediction

Motion as such was the basis of the poetics of futurism in the 1910s, especially in Italy. However, in the historical avant-garde, motion mainly consisted of mechanical dynamics as well as the dynamics of binocular vision that changes points of view (simultanism). Meanwhile, in line with the shift in poetic focus from radical form to radical topics in the late 1920s, there was an increased interest in depicting the body in motion. El Lissitzky’s photo collage Runner still fits into the early avant-garde paradigm yet the motif soon gives way to an ideologically loaded content. Thus, in the paintings of Aleksandr Deineka of the 1920s, the muscular male body, the body of an athlete and a warrior in motion, evoke the cult of strength and youth of the masculine world, unequivocally referring to the will to power and violence. The “invisible excitement” is hidden by the intentionality of the gesture of a running character despite all the positive ecstatic pathos perceived on the surface.

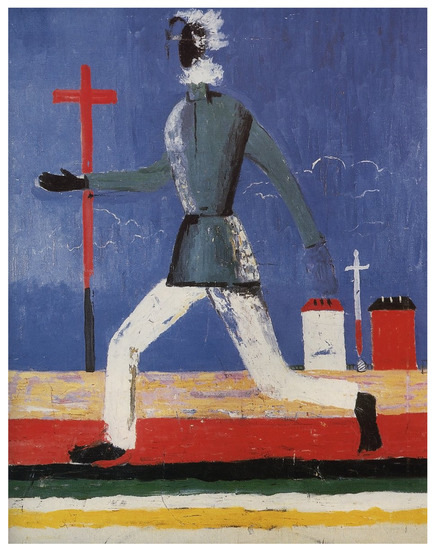

Far removed from official ideology, K. Malevich’s painting The Running Man (1934, see Figure 6) represents a completely different model of motion. The man is running along a schematic representation of land lined with “suprematist” stripes; he appears huge against the background of the low horizon. The intense colouring of the composition based on the archaic triad of black–white–red, the torn contours of the depicted character against the background of symbolic figures (a cross, a sword and isolated blank houses), and the blackened face and bare feet contrasting with the white pants and hair create an atmosphere of anxiety and impending disaster. The reverse direction of motion (from right to left) reveals the important symbolic level of this visual text: a rush to the origins of the painter’s poetics, an acknowledgment of the collapse of hope in the present and a desperate warning about the future. It is difficult to resist the temptation of seeing a socio-political subtext in this message by a dying artist, a message containing an insight into upcoming upheavals, which, in a sense, have already begun. It is no coincidence that one of the numerous interpretations asserts that the image is inspired by the dispossessed peasantry (on the various interpretations of the picture see: Zlydneva 2013).

Figure 6.

K. Malevich. The Running Man. 1934.

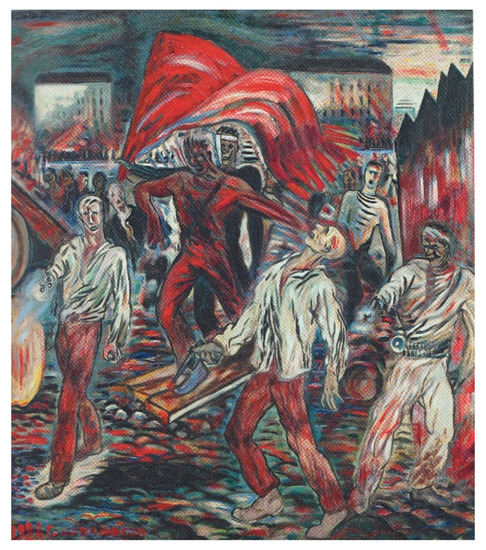

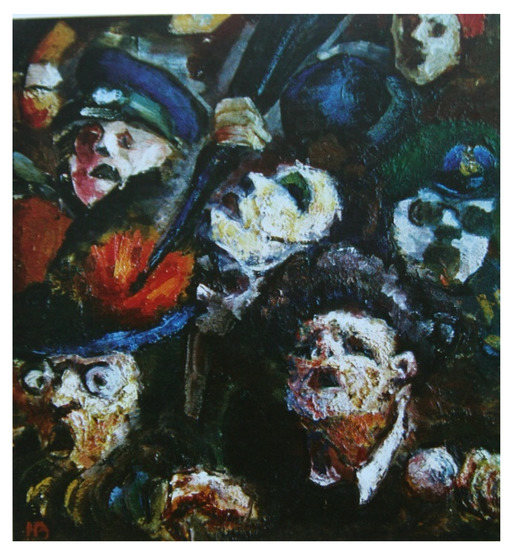

Malevich’s painting is the crowning achievement of the late figurative stage of the master’s work, yet at the same time it is embedded into the art of the time, albeit far removed from its main trends. I am referring to the Soviet expressionism of the late 1920s and the early 1930s, a phenomenon that appeared above the artistic landscape of the era like a bright comet that was unfortunately short-lived. The range of themes and stylistic practices of this episode of the history of Soviet art was quite broad—from conventional landscapes (Aleksandr Drevin, Roman Semashkevich, Boris Golopolosov) to genre compositions in a conventionally metaphoric interpretation such as A. Tyshler’s series “Makhnovshchina” with scenes of bodily violence (the painting Gulyay Pole1, 1927) and paintings on the theme of the revolutionary struggle (B. Golopolosov’s The Battle for the Red Banner, 1928), and direct illustrations of life in prison (see the aforementioned The Man Beating His Head Against the Wall by the same artist). A common feature of Russian/Soviet expressionism is its accentuated motion thanks to dynamic pasty brushstrokes, swirling compositions, and the corresponding motifs—running and rapid driving (from Tyshler’s Makhnovist gigs and Malevich’s galloping cavalry to turning car by R. Semashkevich, etc.). A. Drevin’s canvases, for example, do not contain social themes, yet the impulsive dynamics of the landscape scenes, the contrasting combinations of pastel and dark colours, and the individual psychologized details of nature express the hysterical exaltation of a subject on the verge of an emotional breakdown (Dry Birch, 1930, see Figure 7; Bulls, 1931). Other examples include the representations of ecstatic excitement that describe the psychological state of instability and aggression: bloody battles and wounded bodies (B. Golopolosov’s The Struggle for the Red Banner, 1928, see Figure 8), convulsive self-torment from extreme despair (B. Golopolosov’s The Man Beating His Head Against the Wall, 1936–1937), and the demoniac jubilation of a crowd at a demonstration (A. Gluskin’s To the Demonstration, 1932, see Figure 9). The latter work is especially significant as it refers (just as in the case of worker/party meetings) to the Christian iconography and, more precisely, the depiction of the Gospel episodes of the Mocking of Christ and the Carrying of the Cross. The similarity with the grotesque images of a saint’s tormentors on the canvases of Bosch and with the infernal characters in the later paintings of James Ensor, the forerunner of European expressionism, is quite unambiguous in the painting of the Soviet artist.

Figure 7.

A. Drevin. The Dry Birch. 1930.

Figure 8.

B. Golopolosov. The Struggle for the Red Banner. 1928.

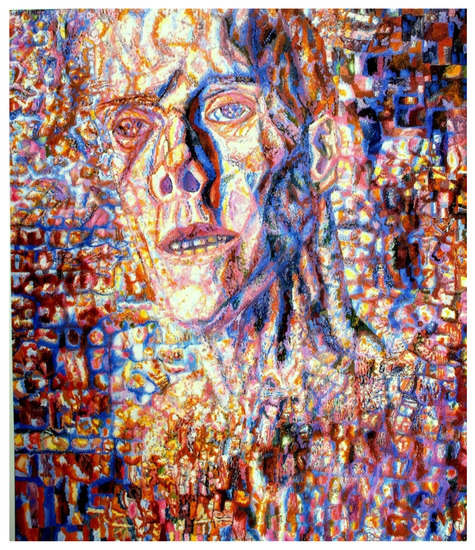

Figure 9.

A. Gluskin. To the Demonstration. 1932.

The pictorial mass in motion and the representation of the suffering body as an expression of approaching catastrophe are also found in P. Filonov’s paintings, which to a certain extent echoed the experiments of the expressionists. Already in the early work of the artist, the baroque vanitas was transformed into the motifs of death and decaying flesh, the world of the dead and witches (the watercolour Man and Woman, 1912–1913, the painting Feast of Kings, 1912). Later, in the 1920s and early 1930s, the painter turned to death masks (Head III, 1930, see Figure 10) and images of thinning bodily tissue–not of an individual figure but of the organic world as a whole. In the same years the artist began to decompose matter into atoms in motion. In the mosaic disintegration of a non-objective pictorial composition into elements and their subsequent reassembly into larger conglomerates, one can distinguish the influence of Vyacheslav I. Ivanov’s ideas on Russian Dionysianism and the latter’s links with ancient metamorphoses. The elemental forces of hidden, flickering mythology are at work here. Bidirectional metamorphoses of the descent and ascent of the bodily, its compression and decompression, its condensation and transparency refer to the mythopoetic complexes of Dionysus and Atlantis, which are so closely associated in Russia with the awareness of the metaphysical nature of social catastrophe.

Figure 10.

P. Filonov. The Head. III. 1930.

The emergence of expressionism painting in the late 1920s in Russia was due to many reasons, including the close familiarity of Soviet artists of the second generation of the avant-garde with contemporary German art (direct contacts between artists, exchange of exhibitions, a general climate of rapprochement in Germany, etc.) and the logic of development of the artistic process, in which the disappearance of the avant-garde of the late 1910s required the compensation of the “warmed up” form, which had already gained inertia. However, there was another reason: the generic features of expressionism such as internal conflict, the complex of psychotic experiences, the themes of violence and fear and the developing, continuously moving pictorial matter/mass responded (whether consciously or not) to the desire to stave off impending disaster in the form of political terror. The themes of death, which were the main referent of totalitarian art according to Igor Smirnov (Smirnov 2005), began to sound ever louder in the paintings of the 1920s.

7. Conclusions

In this article, I examined the motif of the suffering body (Lat. corpus patiens) as a marker of the premonition of the tragic developments of Soviet history. I studied this motif from the dual standpoint of what it depicts and how it depicts it, i.e., both as an object and as a modality of representation. In the paintings of the late 1920s and early 1930s, the suffering body is linked to bodily violence, maiming and bloody battles. It is also expressed through metaphors: a dead bird, a withered tree, a desert landscape, the motif of loss or even scissors as well as manifestations of terrible events such as famine, suicide and death. The state of detriment, angst and psychological conflict as an expression of the suffering body in its subjective incarnation found expression in different types of visualization of motion such as motifs of running, a fluid painterly medium, dynamic compositions and, last but not least, the theory of gesture as the expression of will in the artistic image. Finally, the premonition of the approaching age of totalitarianism is suggested by disguised archetypes that, frequently unperceived by the artists themselves, manifested themselves as the collective unconscious. Here, I am referring to the most tragic episodes of the Gospels (Saviour in Power, the Last Supper, the Passion of Christ) that connote sacrifice and catastrophe as well as the motif of twins as a symbol of the sacralization of power. This deep semantic level of paintings attests to the memory of culture and expands the semantic field of the visual communication.

Naturally, all the aforementioned themes and forms of the expression of human suffering were largely an artistic reflection of the difficult tribulations of generations that lived through war, revolution and devastation. At the same time, considered alongside prophecies contained in other media and studied together with all the other factors that determined the “discourse” of the image, these signs of premonition unambiguously point to the manifestation of social intuition in the fine arts.

This article mainly focuses on the paintings of the younger generation of artists influenced by the historical avant-garde. However, other artists who were distant from experiments of form and motif and were completely embedded in the ideological matrix of the time were also involved in reflecting the gloomy forebodings that hovered in the air. These premonitions manifested themselves in different ways—in a conscious appeal to certain topics, such as the memory of culture in the use of traditional and archaic iconographic schemes that bear the connotations of catastrophe or in the activation of formal pictorial means that convey the anxious, gloomy emotional state of the subject. At the same time, it is important to note that, regardless of the intentions of the artists themselves, the art of the 1920s and the early 1930s served the social demand for the prognostic function. The predictions of many artists came true just a few years later in the disaster of repressions: B. Golopolosov was expelled from the professional community for 40 years in 1937, A. Drevin was executed in 1938, and P. Filonov died in poverty in 1942. It remains an open question whether such art contributed to shaping the future. Be that as it may, it was more of a diagnosis whose formulation does not accelerate or retard the inevitable development of the disease but only warns against its consequences. While the alternative movement of early Soviet art fulfilled its social mission, this message was unfortunately not heeded by contemporaries.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Note

| 1 | Gulyaypole is the Ukrainian town where in time of the civil war of the 1919s the Ukrainian anarchist state under the leadership of Makhno was established. |

References

- Fofanov, Sergey. 2019. Golovoy ob Stenu. Boris Golopolosov. Katalog vystavki v Gosudarstvennoy Tretyakovskoy Galeree. Moskva: Gosudarstvennaya Trtyakovskaya Galereya. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault, Michel. 1977. Discipline and Punish. The Birth of the Prison. New York: Random House. [Google Scholar]

- Groys, Boris. 1988. Gesamtkunstwerk Stalin. München and Wien: Hanser Verlag (Edition Akzente). [Google Scholar]

- Guenther, Hans, and Evgeniy Dobrenko. 2000. Sotsialisticheskiy Kanon. Sankt-Peterburg: Akademicheskiy Proekt. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov, Vyacheslav I. 1979. Drevniy uhzas. In Ivanov, Vyacheslav I. Sobraniye Sochineniy Vv. 1-4. V. 4. Brussel: Satyi. First published 1909. Available online: https://rvb.ru/ivanov/1_critical/1_brussels/vol3/01text/02papers/3_077.htm (accessed on 17 October 2022).

- Ivanov, Vyacheslav Vs. 2009. Bliznechny kult i Dvoichnaya Simvolicheskaya Klassifikatsiya v Afrike. In Ivanov Vyacheslav Vs. Izbrannye Trudy po Semiotike i Istoriyi Kultury. V. V. Mifologiya i Folklor. Moskva: Yazyki slavyanskoy kul’tury, pp. 11–48. [Google Scholar]

- Roytenberg, Olga. 2004. “Neuzheli kto-to Vaspomnil, Chto My Byli”. Iz istoriyu Hudozhestvennoy Zhisni 1925–1935 godov. Moskva: Galart. [Google Scholar]

- Salienko, Aleksandra. 2018. Vystavka Proizvedeniy Revolyutsionnoy i Sovetskoy Tematiki v Gosudarstvennoy Tretyakovskoy Galeree 1930 Gods. Zabytyi Eksperiment. In Istoriya Iskusstva v Rossyi XX vek: Intentsiyi, Konteksty, Shkoly. XXVIII Alpatovskiye Chteniya. Mezhdunarodnaya Konferentsiya. Materialy. Moskva: Moskovskiy Gosudarstvennyi Universitet, pp. 171–89. [Google Scholar]

- Smirnov, Igor. 2005. O groteske i rodstvennyh emu kategoriyah. In Semiotika straha. Moskva: Nauka, pp. 204–21. [Google Scholar]

- Tarabukin, Nikolay. 1929. Zhest v Iskusstve. Manuscript. Moscow: Russia State Library, Fond 627. [Google Scholar]

- Tarabukin, Nikolay. 1973. Smyslovoye znachenie diagonalnyh kompozitsiy v zhivopisi. In Trudy po Znakovym Sistemam. Vol. VI. Tartu: Tartuskiy Gosudarstvennyi Universitet, pp. 472–81. [Google Scholar]

- Tarabukin, Nikolay. 2005. Dvizhenie. In Slovar’ Khudozhestvennyh Terminov. G. A. H. N. 1923–1929. Edited by Chubarov Igor. Moskva: Logos-Altera, Esse Homo, pp. 126–27. [Google Scholar]

- Toporov, Vladimir. 1983. Prostranstvo i tekst. In Tekst: Semantika i Struktura. Moskva: Nauka, pp. 227–84. [Google Scholar]

- Zaretskaya, Anastasiya. 2019. Golovoy ob stenu. Boris Golopolosov skoro v Tretyakovke. In ARTivestment. Available online: artinvestment.ru (accessed on 19 February 2019).

- Zlydneva, Nataliya. 2009. “Scaring” in the late avant-garde painting. In Avant-Garde i Ideologiya: Russkie Primery. Belgrad: Izdatel’stvo Belgradskogo Universiteta, pp. 521–31. [Google Scholar]

- Zlydneva, Nataliya. 2013. Kuda bezhit krestyanin: Zagadki pozdnego Malevicha. In Vizual’ny Narrative: Opyt Mifopoeticheskogo Prochteniya. Moskva: Indrik, pp. 179–94. Available online: https://inslav.ru/sites/default/files/editions/2013_zlydneva.pdf (accessed on 17 October 2022).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).