Abstract

Krystyna Miłobędzka (born 1932) is one of the most interesting and unique phenomena of the Polish poetry scene of the 20th and 21st centuries. Two characteristics of her poetry, the visual character of her many poems and her preoccupation with the concept of the garden-world, are worth a closer look. Miłobędzka’s poetry refers to the topoï of the garden-world in single poems and cycles of poetic texts. Her hortus mirabilis, inserts itself into the sphere of the metaphysical reflection of nature, giving Miłobędzka’s poetry a specific dynamic in which the “I”—the gardener—has a significant role as an observer, and as a creator of entities. The activity of looking, which happens, in fact, in all types of verbs and aspects, is in this specific sphere (look, watch, see), fundamental to defining oneself in the world and the world’s relationship to oneself. In this perspective, the image of the garden from childhood, is confronted by a necessary new visualization. The temporal aspect of the garden is at the center of existence, in the cyclical return of nature’s laws of rebirth and death, which are relevant to the personal, singular perspective of the end in many of Miłobędzka’s volumes. In Anaglify (Anaglyphs), some poems particularly fit the issue of visuality in poetry, not only at the conceptual level, the place granted to observation, the poet-particular observer, but the poem itself. They are conceived as graphic and pictorial realizations. Poems from the volume dwanaście wierszy w kolorze (twelve poems in color) or wszystkowiersze (omnipoems) are special cases of these. The selected words are conceived in color, and their arrangement on the space of the page has meaning. The parallel between looking and writing, which Miłobędzka consistently uses in her writing method and poetically admits, is also very important. Although her poetic diction alludes to historical avant-garde and linguistic poetry achievements, her lyrical savoir-faire is characterized by a certain new minimalist construction and a separate, recognizable style. Miłobędzka’s innovativeness lies in combining seemingly distant and sometimes poetically opposite categories: full, ambiguous image-in-poem and asceticism by means of expression, such as a minimal number of words. Her poetry is deeply rooted in perceiving, seeing, watching, and contemplating the world—faithful to its physicality but also open to the most essential questions of philosophy asking about existence and its limits. This new visibility of elements is reflected in authentic poetic delight and in the “visualizing” form, where the poem also becomes an image on the plane of a sheet of paper or becoming one side of the house wall as a mural poem.

1. Introduction

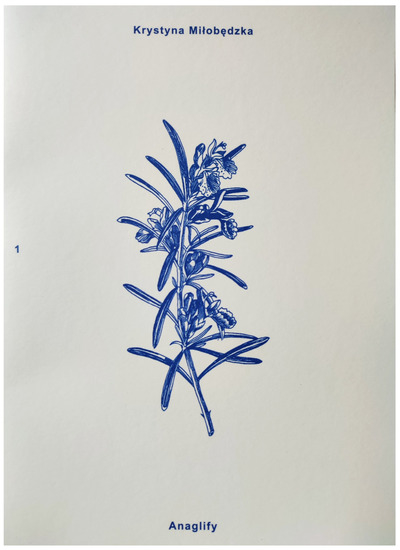

Krystyna Miłobędzka was born in Margonin in 1932 and is one of the most interesting and unique phenomena of the Polish poetry scene of the 20th and 21st centuries. Although her debut in 1960 with the volume Anaglyphs (Miłobędzka [1960] 2019)1 places her near the generation of “Współczesność”2, the period of fascination with her work falls toward the end of the 20th and the beginning of the 21st centuries.

The author currently lives in Puszczykowo near Poznań, Poland. She remains an inspiration for many Polish poets from different movements despite not identifying with any fixed poetic group (Borowiec 2012). Krystyna Miłobędzka’s published volumes following her first Anaglyphs are still consistently rich in meaning and formal, inseparable linguistic solutions, appropriate and recognizable to her style3. It is also worth recalling that Miłobędzka, who holds a doctorate in literary studies and is a theatre scholar, also worked as a theatre director, pedagogue, and lecturer in theatre classes at Adam Mickiewicz University. She is also the author and co-author of scripts, rehearsals, written dialogues and published letters4. Miłobędzka’s work has also received numerous awards5.

Much has been written about Miłobędzka’s poetry, emphasizing the character of her poems, such as their minimalism of form and consolidation (Nyczek 2008, pp. 173–77; Żurek [2017] 2022), wordiness (Maliszewski 2020, pp. 74–75), a strong childlike imagination (Orska 2018, pp. 255–85), predilection for concreteness (Kałuża 2008, pp.199–215), incomprehensibility, avant-garde, and linguistic inspirations (Bogalecki 2011; Grądziel-Wójcik 2008, pp. 21–34), diversity of her poetical world (Borowiec 2012) or her references to the poetry of Tymoteusz Karpowicz (Górniak-Prasnal 2017, pp. 253–69) and Miron Białoszewski (Suszek 2020).

There is now also a group of critics who try to read Krystyna Miłobędzka’s poetry in the context of the discourse of ecocriticism or interpret it with the tools appropriate for reading ecopoetry (Lekowska 2020; Jarzyna 2017; Skurtys 2017). This is entirely possible: in her attentiveness to nature, Miłobędzka becomes one of the pioneers of such a poetical world view. I also think that it is possible to outline many, compatible common parts between recent works in the field of reading ecopoetry and ecocriticism (Fiedorczuk and Beltrán 2020; Koza 2020; Małecki and Woźniak 2020) and Krystyna Miłobędzka’s poetry. However, I find the best definition (in fact, rather a kind of “non-definition”) in the fragment by Julia Fiedorczuk:

I talk about the “ecological turn”, trying to avoid the terms “ecological poetry” or “ecopoetry”. These terms do function, of course, but mostly they involve attempts at some new genre or subgenre of “ecological” poetry. I am skeptical of such attempts for two reasons. First, more than human, nature has always been one of the most important subjects of poetry, and it is indeed difficult to imagine a poem that does not in any way refer to the natural world or shed light on the question of the relationship between humans and the environment. Thus, there is a risk that “ecopoetry” is just a label, artificially generated to describe phenomena that have always existed. Secondly, attempts to describe “ecopoetry” as a new kind of poetry are often prescriptive, in other words, they propose a list of criteria that a “correct” ecological poem should meet (consequently, the others would have to be considered “non-ecological”). This approach seems uninteresting also because its proponents often lose sight of the literary qualities of the text, focusing almost on the content.(Fiedorczuk 2019, pp. 14–15)

In other words, I think that Krystyna Miłobędzka’s poetry escapes clear-cut categorizations, even the most fashionable and handy ones, even if they are “eco”. In thinking about the world-garden, language-poetry, inspiration and creation, this poetry retains a separate, inherent, thoroughly original character.

That is why the hortus mirabilis motif discussed here, goes beyond the obvious conundrum, reaching out to poetic texts other than the important but already analyzed and repeatedly cited by critics6. Also because “spoken” here is primarily associated with what is “seen”, “articulated” with what is “made visible”, and “lost” with “found”. In such a lecture the very known (and widely interpreted) poem drzewo jak drzewo (the three as the three) becomes a kind of primary symbol of hortus mirabilis—mirabilis and lost Eden but it also concretely guides our gaze vertically along the tree trunk upward toward the unreachable the tree crown:

| drzewo tak drzewo | the three yes the three |

| że drzewa już nie ma | that the three is no more |

| chmury (chmury) | clouds (clouds) |

| (Miłobędzka 2013b, pp. 132–33) |

Krystyna Miłobędzka is still not known enough outside of Poland “because of its rootedness in the peculiarities of the Polish language” (Wójcik-Leese 2006, p. 44) although some of her poems have been translated into English7. Two characteristics of her poetry, hitherto not assembled by scholars, are worth a closer look today, especially in poem examples that combine both simultaneously. The first characteristic relates to the visual character of her many poems, and the second is her preoccupation with the world garden, which she perceived as a kind of “fair of wonders” (Szymborska 1986, p. 42). Miłobędzka’s poetry, which can be boldly described as modern and avant-garde, refers to the topoï of the garden-world in single poems and cycles of poetic texts. This important cultural trope stems from the primordial role of the poet-gardener because, as we read in one of Mateusz Salwa’s many works devoted to gardens, entitled Antyogród w ogrodzie (Antigarden in the Garden):

The garden is one of the more enduring topoï present in Western culture. At the same time, it must be remembered that it is a topoï in a double sense of the word. For the garden is as much a real place as it is a figure of thought. These two orders cannot be separated, as every real garden, i.e. a separate space where plants are cultivated for utilitarian or aesthetic purposes, is in its own way the realization of an imaginary garden.(Salwa 2020, p.112)

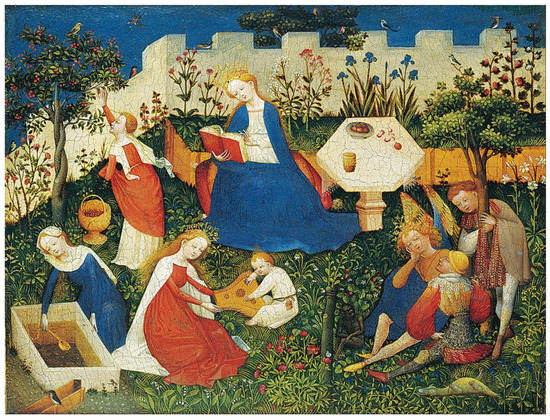

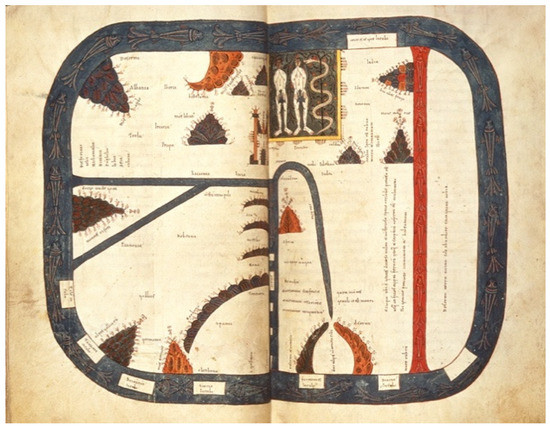

However, with hortus mirabilis, regardless of the history and theory of the garden, the current concept and the practice of implementation of the times stimulates the imagination of the creator. The meaning of the word “mirabilis”—also changes over the centuries. The signification can be understood as:—marvelous, miraculous, wonderful, supernatural, extraordinary. Some examples include the hanging gardens of Semiramis (Figure 1), the Garden of Eden imagined in the form of a painting by the Upper Rhenish Master (Figure 2) or a map (Figure 3), or even the image of a man who is a garden himself by Arcimboldo (Figure 4).

Figure 1.

The Vision of Babylon Garden. 1912. https://pl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plik:Ogrody_semiramidy.jpgimage (accessed on 16 July 2022). From book published in 1912 (Petit Larousse).

Figure 2.

Upper Rhenish Master. c.a. 1410–1420. The Little Garden of Paradise. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/5/5f/Upper_Rhenish_Master_-_The_little_Garden_of_Paradise_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg (accessed on 16 July 2022).

Figure 3.

The Map of the Garden of Eden. c.a. 1009. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/18757/18757-h/images/map06.jpg (accessed on 18 July 2022).

Figure 4.

Arcimboldo, Giuseppe. 1573. Automne. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/9/90/Giuseppe_Arcimboldo_-_Autumn_-_WGA00812.jpg (accessed on 18 July 2022).

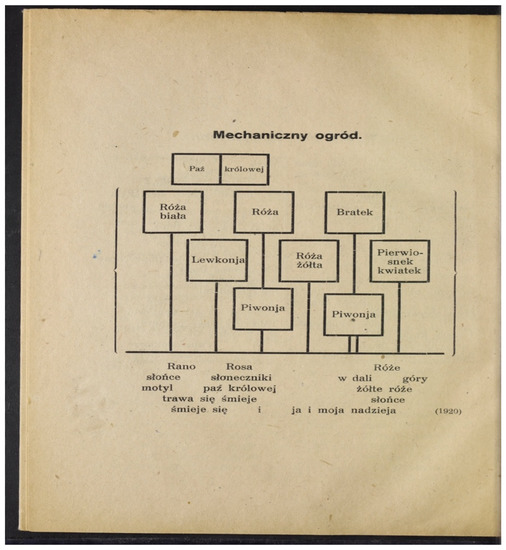

Between the literary gardens of past centuries, we find additional examples from Garden of Epigrams by Wacław Potocki (Potocki [1648] 1907) and Tytus Czyżewski’s The Mechanical Garden (Czyżewski [1920] 1922, p. 24) (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Czyżewski, Tytus. [1920] 1922. https://polona.pl/item/noc-dzien-mechaniczny-instynkt-elektryczny,NzIxMzg5NDQ/31/#info:metadata (accessed on 22 March 2022).

The history of gardens (Majdecki 1972; Szafrańska 1998) and literary research on the vision of the literary gardens (Rymkiewicz 1968), there is a special place in the imagination, meeting with what is seen by the poet. The meeting space for these gardens is as varied as they are. This is also partly because of a lack of a clear concept and definition in the description of gardens history, and thus of specific interpretation tools. As Jan Birksted writes: “Garden history, unlike the history of painting, sculpture, and architecture, has no conceptual foundations. It lacks the elements of scholarly and critical consensus: a conventional set of interpretive methods, agreed-upon leading terms, ruling metaphors, and descriptive protocols.” (Birksted 2003, pp. 4–5).

However, the concept of hortus mirabilis stimulating the imaginary and scientific approach is still interesting for the authors of literary works and scholars of different branches of sciences, as we can observe it in the recent publications. The fascination in the peculiar is because poetic garden has also been well described in an extremely interesting work by Dimitrij Sergeevič Lihačev (Lihačev 1991).

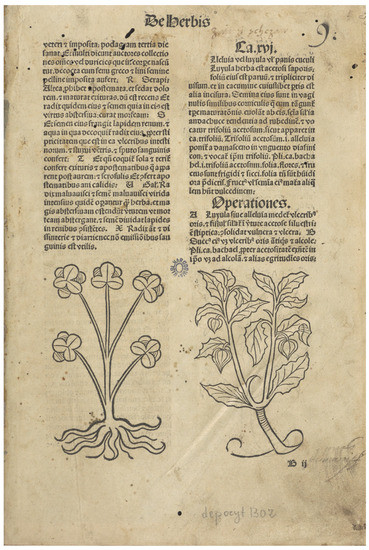

Similarly, Miłobędzka’s poetry, even if some scholars have already written about the presence of plants in her poetry (Górniak-Prasnal and Kuchowicz 2015, pp. 117–26; Lekowska 2020, pp. 262–71), has an as-yet-undefined world, a rediscovered hortus mirabilis. It spreads its secrets before the onlookers, amazing them and conveying a certain knowledge. Its image is meticulously created in the individual poems, which comprise a specific personal poetic “herbarium”. Thus, we find in this poetry in the space of the various specific volumes: seeds, leaves, flowers, trees and branches, their general symbolism, and species names. The most important thing, however, is beyond the botanical description—activated in the image are new meanings conveyed through the medium of the poem. First, careful observation of the world is made with a poetic eye (Figure 6 and Figure 7):

Figure 6.

Meydenbach, Iacobus (1491). https://polona.pl/item/Eadem,hortus-sanitatis,MTExNzkwOTEx/28/#info:metadata (accessed on 17 July 2022).

Figure 7.

Cover by Marcin Markowski In: (Miłobędzka [1960] 2019).

2. Observation

Entering the marvelous garden first involves, in Miłobędzka’s case, a very insightful view of oneself and the world in which this poetic “I” finds itself. It also marks an act of courage to step outside one’s own comfort zone. The boundary-gate-wicket to the garden is an attempt to understand what is different from the “I”, which is necessary to define the “I” itself. While encountering the world and the garden, crossing a hitherto impassable boundary is important, which may be the very ritual of sensual, visual initiation. Finally, it turns out that it is the world garden that invites itself and enters the thresholds of our private existence, discovering in ourselves the space where the viewed elements exist “from within” (Foucault and Miskowiec 1986, pp. 22–27):

Na szybie pokrytej parą rysujemy dwa kółka dodając uszy, wąsy i ogon.W ten sposób powstaje kot. Można także narysować świerk, kwiatalbo człowieka.

Dopóki różnica temperatur po obu stronach szyby utrzymuje się –ludzie, zwierzęta i rośliny istnieją w sposób nie budzący wątpliwości.Istnieją z zewnątrz i od środka.(Miłobędzka [1960] 2020a, p. 9)

Draw two circles on the steam-coated glass, adding ears, whiskers and a tail. In this way, a cat is created. One can also draw a spruce, a floweror a person.

As long as the temperature difference on both sides of the glass remains—humans, animals and plants exist in a way that is not—doubt.They exist from outside and from within.

It is brought into being by very careful looking, or, in Miłobędzka’s case, by its constant “drawing”, here on a pane of glass as on a sheet of paper, and in some works, in the very space of the poem by its graphic location.

The verb “patrzę”, like the neologism “jestnienie”, balances between “jest” (is) and “nie” ((there is) not), indicating the paradox of being enchanted and dazzled by the world as a kind of compliment, sending us back to the reflection of an image, in the flash of an eye, in a pane of glass, or water, as in this poem by Miłobędzka:

Co ja robię, patrzę w jestw to samo jest mnie i to samo jest wodyw to olśnienieto jestnieniejest nie nie

które scalamktóre skracam do istnienia(Miłobędzka [2000] 2020b, p. 233)

What I do, I look in isinto this same is me and this same is the waterinto this dazzleit’s a beknowingknow being is not

which I mergewhich I shorten into existence

In this way, hortus mirabilis, inserts itself into the sphere of the metaphysical reflection of nature, giving Miłobędzka’s poetic garden a specific dynamic in which the “I”—the gardener—has a significant role as an observer (as we read in the poem’s climax), and as a creator of entities. The activity of looking, which happens in fact in all types of verbs and aspects, is in this specific sphere (look, watch, see, perceive), fundamental to defining oneself in the world and the world’s relationship to oneself. This visualizing reflection, in addition to careful observation, is accompanied by weighty optical discourses and statements reminiscent of the laws of physics and related to the perception of the dimensions of reality:

Oczy nie widzą głęboko, widzą daleko albo blisko, dlatego tyle brzegów,tyle zgniecionych mórz—czy myśleniu wystarczy oczu na zatopienie świata?Za dużo razy poznane przez siebie, żeby mogło zapuścić korzenie.Przesuwane przez wszystkie pory roku. Zbliżało się do siebienieustannie zbyt lekkie, aż zmieniło się w wiatr.(Miłobędzka [1970] 2020c, p. 62)

Eyes don’t see deep, they see far or near, that’s why so many shores,so many squashed seas—is there enough eyes for thinking to sink the world?Too many times met by itself to be able to put down roots.Shifted through all the seasons. Approached constantly tooLight, until it turned into wind.

Kinetic and optical laws complement one other here, creating the credibility of the individual garden. What is too close becomes invisible to the eyes. Jestem że widzę że widzę że mijam (I am that I can see that I can see that I go by) (Miłobędzka [1975] 2020d, p. 113), says one of Miłobędzka’s titles, bringing another important note a few lines further on: “less and less of me”. Here, there is some kind of correspondence between the enlargement of the external garden and the diminution of one’s own self. The parallel between looking and writing, which Miłobędzka consistently uses in her writing method and poetically admits, is also very important: “(…) pisz pisz aż w pisaniu znikniesz/ patrz patrz aż znikniesz w patrzeniu (Miłobędzka [2004] 2020e, p. 314)”. (write write on till you vanish in writing/ look look on till you vanish in looking) (Miłobędzka 2013c, p. 127). An attentive reading of Miłobędzka’s poetry and that of her life partner, Andrzej Falkiewicz, draws attention to an interesting aspect of sensory perception, admitting something that, for the poet, is also an answer to the loaded question of which of the senses she considers most important; he replies: “As a man of our civilization—the Western civilization—I have to put sight at the forefront. It is the sense that captures to some extent the functions of all the other senses. But as a universal man, I would say touch. It is the elemental sense —the sense that enables people to conceive new life.” (Borowiec et al. 2009, p. 32).

3. To Touch by the Colors

For Miłobędzka, part of whose life was spent exploring nature (the forest park in Margonin, the Tatra Mountains, the forests near Poznań), childhood is also an important reminder of the world—a mysterious garden that preserves the colors and vitality of entities in memory. In this perspective, the image of the garden from childhood, is confronted by a necessary new visualization:

Kolory w dzieciństwie układają się same na powierzchniach miękkichi delikatnych. Nie wiedząc nic o sobie, nie znając swojej wartości, niepotrzebują się dopełniać tworzyć tęczy.(Miłobędzka [1960] 2020f, p. 18)

In childhood, colors arrange themselves on the soft and delicatesurfaces. Not knowing anything about themselves, not knowing their own value, they do not need to complement each other to form a rainbow.

The poet defines child gazing in an interesting way: “It is spontaneous, self-generated thinking, not taught by others. We are born with it, and then we learn to look at the world already with someone else’s eyes, to speak in someone else’s words, the words of adults” (Borowiec et al. 2009, p. 86). Referring to the bearing of Jean Piaget’s theory (Piaget 1923, [1926] 2003), she also draws attention to the artistic realizations of children, where images and words are treated interchangeably. The poet finds a name-combination for them: “słoworysunki”, “word-drawings” (Borowiec et al. 2009, p. 142). The poetic tricks of animation and personification are also embedded in the children’s world and the power of children’s imagination. Here, plants and fruits exist in an important space because they significantly focalize the seemingly inanimate world. It is as if the magic of an enchanted garden, or the unique memory of colors, was transferred to everyday objects, as in her painterly poem from the volume Anaglyphs:

Ta butelka z sokiem pomarańczowym ma niebieski korek. Niebieskiekorki zastępują wyduszonym pomarańczom niebo.

Jeszcze nigdy pomarańcze nie były tak blisko nieba jak w butelce -nigdy go nie dotykały. Zresztą nie muszą już dojrzewać, więc zetknięciez niebem ma dla nich inne znaczenie—to jest albo inny przymusalbo inna przyjemność.(Miłobędzka [1960] 2020g, p. 10)

This bottle of orange juice has a blue cork. The bluecorks replace heaven to squeezed oranges.

Never before have the oranges been as close to the sky as they are in the bottle –never touched it. Besides, they don’t have to ripen any more so their contactwith the sky has a different meaning for them—it is either a different compulsionor a different pleasure.

The author also tells us another story from her time at the Institute of Wood Technology in Poznań, giving us the pictorial birth of the Anaglyph cycle and spatial vision that her poems preserve: “The most important thing I took away from the Institute were these wonderful glasses with one glass turquoise and the other red, which made it possible to receive spatial images. This, among other things, gave rise to the name for my first texts—anaglyphs” (Borowiec et al. 2009, p. 26). Commenting on this first series, the author also says: “It is there to see each thing at once from the outside and from the inside—and this is written clearly in the first anaglyph, but it is also repeated in the subsequent ones. In the s u b s t a n c e t h e i n t e r v e n t i o n is a seeing that is at once objective and personal, private. That is how I would read these records today” (Borowiec et al. 2009, p. 50).

4. The Garden Itself

In Miłobędzka’s volume entitled Pokrewne (Related), in addition to poems with significant titles for our considerations, such as Roślinne (Vegetal) (Miłobędzka [1970] 2020h, p. 57) or Chlorofil (Chlorophyll) (Miłobędzka [1970] 2020i, p. 58), there are also two poems of great importance to Miłobędzka’s imagery and to our considerations, entitled Ogród (Garden) (Miłobędzka [1970] 2020j, p. 66) and Narodzenie z oczu (Birth from the Eyes) (Miłobędzka [1970] 2020k, p. 59). The first contains a visualization (to which the reader succumbs) of the thicket, entanglement, and green elements of the garden climbing towards the sun. As we read the subsequent verses, we realize that the gardens are personified and that the thicket, the growing, and searching for paths also belong to the sphere of human communication. The visualization of the garden, here, acts as a costume and, as it were, a diagnosis of the lyrical situation, the passion, and the danger involved in “tissue penetration”:

Kto tu oddzieli, komu potrzebne nazywanie, splecione kryją się w sobie,owijające, owijane, dławione jednych oddechem, podają sobie pokarmwielkimi przełykami. Nie ma żadnych ścieżek, nie ma dojścia, jesttylko kawałek uległego podłoża, na ogrody w tobie, zawsze ten sampowrót, ten sam cień wysyłany spod najniższych roślin, wyrastaniepowoli od stóp, uderzenie ciepła w ciasne objęcia tkanek. Tu ogień,kiedy się otworzą.(Miłobędzka [1970] 2020j, p. 66)

Who here will separate, who needs naming, entwined they hide into each other, wrapping, wrapped, choked by one breath, they feed each otherwith great gulps. There are no paths, there is no access, there isonly a piece of submissive ground, to the gardens within you, always the samereturn, the same shadow sent from under the lowest plants, growingslowly from the feet, the throb of heat in the tight embrace of tissue. Here the fire,when they open.

The second poem, demonstrates in its very fabric the close relationship between the one watching and the one watched, who/which simultaneously becomes a registration of life processes, as in the following extract from the poem: “Spojrzenie po spojrzeniu/rozgina wejścia coraz głębsze: trawa dzieli się trawą/liść łamie się liściem, gną się i strzępią, wplątane w ziemię biją powietrze drzewami.” (Miłobędzka [1970] 2020k, p. 59). (Gaze after gaze bifurcates the entrances deeper and deeper: grass/shares grass, leaf breaks leaf, bend and fray, entangled/in the earth beat the air with trees).

The temporal aspect of the garden is at the center of existence, in the cyclical return of nature’s laws of rebirth and death, which are relevant to the personal, singular perspective of the end:

jeszcze do wnukajeszcze do ogrodujeszcze do żalu nad sobą(Miłobędzka [1970] 2020l, p. 225)

yet to the grandsonyet to the gardenyet to self-pity

The dynamics of change interact with the dynamics of the image seen and processed. Miłobędzka aptly describes this creative process:

Actually, none of the images we have in ourselves should be immobilized, that is, become something unchangeable, something absolutely permanent. Because, after all, these images even in memories do not freeze—“they are not a music box and not a photograph”. They are important when they come to life, when something disappears and something arrives in them, no matter how far back in time they are. In fact, they are deprived of time, and in this deprivation, they are changing and touching the one who owns them. They do not speak back to us in the same way every moment, neither with the same voice nor with the same gesture; and even if there were the same image, for me, having a different experience and being in a different time, the gesture and word from there are already something completely different. As long as it is alive, changing and moving, it has some meaning…—it repeals itself, as long as it is alive”.(Borowiec et al. 2009, p. 26)

5. Living Garden of Poems

Among the poems by Miłobędzka, some particularly fit the issue of visuality in poetry, not only at the conceptual level, the place granted to observation, the poet-particular observer, but the poem itself. They are conceived as graphic and pictorial realizations. Poems from the volume dwanaście wierszy w kolorze (twelve poems in color) (Miłobędzka 2012) are the special cases of these. The selected words are conceived in color, and their arrangement on the space of the page has meaning. Here, they meet in the minimalist form of the poem “I” and “tree” and respond to each other in a congruent symmetry: two questions, two text fragments highlighted in green, a twice-referenced word: “I see”:

(i mówiące mnie drzewo?)z ilu drzew t o j e d n o widzę?wreszcie raz powiedziećw i d z ę(Miłobędzka [2012] 2020m, p. 366)

(and tree speaking me?)Of how many trees this one can I see?finally say it onceI see

Behold, “I see” also means here as much as “I know”—read with the color codes and symbolism of nature (hope for green), it also means the selectivity of this knowledge if we read the green: “this one/I see” (as “this one I know” and “I am”). The minimalist form, when the poem fits at the top of the page and within empty space, is also impressive and helps to balance this ambivalence of meaning: a sense of pride in the joy of looking and seeing and the singularity of the experience. Intertextually, we are close to other texts such as the wywód jestem’u (discourse of I am) by Miron Białoszewski (Białoszewski 1961, p. 7), Eimi (I am) by E.E. Cummings (Cummings 1933), Je suis comme je suis (I am as I am) by Jacques Prévert (Prévert [1946] 1949, p. 100), but also the Socratic, “I know that I know nothing”.

The poem of Miłobędzka can also be a kind of enigma or a clever riddle hidden in the answer to the question: What does not see deeply? Because the eye cannot see itself. With its blue color, the poem adopts the issue previously suggested by Miłobędzka—the impossibility of seeing deeply.

The author’s decision here seems to be in a line with the conviction of the philosophical thought of Ludwig Wittgenstein, who in his Remarks on Color, notes: “If all the colors became whitish the picture would lose more and more depth”. (Wittgenstein 1977, p. 44) Interestingly, Miłobędzka launches the rhyme deep in the process: deep—eye; and, let us say it one more time: it is important because in Polish the word “eye” (oko) is part of the word “deep” (głęboko). The eye, repeated in the poem, grows huge and intense simultaneously:

co nie widzi głęboko…? what does not see deeply…?oko an eyeOKO AN EYE(Miłobędzka [2012] 2020n, p. 364)

We find an equally interesting notation in another poem, in which, repeating the word “only” in a specific arrangement relates it, both to the poem and to the hidden addressee “you”. The addressee is the most important, for to him/her (but also to the poem as well) refers the imperative, underlined “be” and enlarged ochre “shine”. This potential shining is implicitly introduced by the sun; in the space of Miłobędzka’s “colorful” poems, it is also coherent on the whole, precisely above the line image of the garden where the eye looks at the tree in the sun:

tylko bądź only betylko onlyŚWIEĆ SHINE(Miłobędzka [1970] 2020o, p. 368)

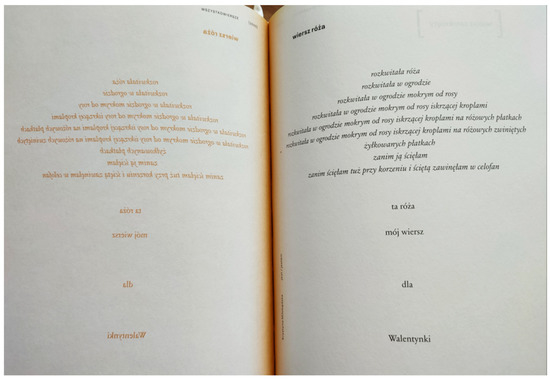

The poem Rose, from the volume omnipoems (Miłobędzka [2000] 2020p, pp. 256–57) belongs to Miłobędzka’s visual and garden poems. However, it is also something more: it is a full calligram enriched by its reflection. The individual words are arranged verse by verse to form a graphic rose: “rose bloomed/ bloomed in the garden/ bloomed in the garden wet with dew/ bloomed in the garden wet with dew sparkling drops/ bloomed in the garden wet with dew sparkling drops on pink petals/ bloomed in a garden wet with dew sparkling drops on pink curled/ veined petals/ before I cut it down/ before I cut it right at the root and wrapped the cut in cellophane/ this rose/ my poem/ for Valentine”. Miłobędzka inscribes herself with her poem by developing it with the symmetry and meaning of the rose in bloom. She creates a poem-picture, in a certain rhythm, thus referring to Tadeusz Peiper’s concept of a blooming poem (Peiper [1926] 1972) and the love symbolism of the rose, thus inscribing herself in the rich history of poems dedicated to roses. The reverse image is similar to a flower, imprinted in the herbarium, a memento of the queen of the garden—the rose (Figure 8):

Figure 8.

Miłobędzka’s poem rose—wiersz róża is composed by calligram and its reflected image in color on the left in: Krystyna Miłobędzka (2020), jest/jestem (is/I am), Lusowo: Wydawnictwo Wolno, pp. 256–57. (Miłobędzka [2000] 2020p, pp. 256–57).

Two more poems deserve attention. The first poem asks the question of “having”, “possession”, belonging, and one’s place in the world. Underlined and “colored”, “there is no”, contradicts the invisible “is”. In Polish, it is this cluster of “nie ma” that is the answer to the question, “is there?” Here, the lyric subject has and does not have this small world; it is also reflected consistently in other poems because the following reading is also possible otherwise: it is the world that has me.

M A M( MN I E MA )WŁASNYb a r d z o m a ł y ś w i a t(Miłobędzka [2012] 2020q, p. 360)

I HAVE

( HAS ME )

OWN

v e r y l i t t l e w o r l d

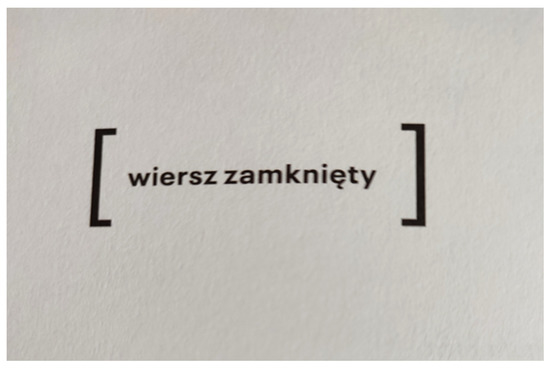

The last example shows a poem literally closed in a large square bracket. If we recall what the poem is about, for example, a rose or a tree, we can also interpret the poem as a kind of garden with a gate (Figure 9):

Figure 9.

Krystyna Miłobędzka.2020. wiersz zamknięty (closed poem) jest/jestem (is/I am), Lusowo: Wydawnictwo Wolno, p. 258. (Miłobędzka [2000] 2020r, p. 258).

Gutorow, writing about Miłobędzka’s poetry-creating power, draws attention to her desire to reach such a point of speech, which is the absolutization of speech or ultimate point (Gutorow 2011, p. 290). It seems that the “closed poem” is an example of just such attainment of speech, although even here, through the play of graphic (visual) closure, one may be tempted to make ambiguous interpretations for the reason that in the vertical line, there is an opening —light and space above the poem and below the poem. If the poem is a key, and we turn it from horizontal to vertical in the likeness of a key, we open the closure.

6. Hortus Mirabilis by Krystyna Miłobędzka—Conclusion

What is the character of the world-garden and hortus mirabilis in the poetry of Krystyna Miłobędzka?

The weight and admiration of the universe of the garden and its wonders are present all the time in Miłobędzka’s work. We also find traces of this importance in the poet’s correspondence with another poet important to her, the aforementioned Tymoteusz Karpowicz. Both poets and their life partners often change their opinions on gardening, on new plants, their development and illnesses, seasons, vegetables, flowers, trees and bushes. However, let us draw attention, once again, to the essence of the garden’s appearance, to the importance of its visual character which appears in these words of Tymoteusz Karpowicz in a letter addressed to Andrzej Falkiewicz:

“And how does your garden sing (in colors and shapes) under the magical baton of Ms. Krystyna? How wide the Newcomers have already opened the greenery?”.(Miłobędzka et al. 2021b, pp. 738–39)

After all, Krystyna Miłobędzka—the gardener and observer continuously shares her experience with Krystyna Miłobędzka—the poet, that is, a careful observer of the world.

On the one hand, the poet in her poems, refers to the topoï of the tender observer, the poet-gardener, and the garden-world. On the other hand, she introduces a new verbal articulation to her poetic pictures. Although her poetic diction alludes to historical avant-garde and linguistic poetry achievements, her lyrical savoir-faire is characterized by a certain minimalist construction and a separate, recognizable style. Miłobędzka’s innovativeness lies in combining seemingly distant and sometimes poetically opposite categories: full, ambiguous image-in-poem and asceticism by means of expression, such as a minimal number of words. Her poetry is deeply rooted in perceiving, seeing, watching, and contemplating the world—faithful to its physicality but also open to the most essential questions of philosophy asking about existence and its limits. Among Miłobędzka’s poems, a special category is formed by texts that introduce elements of the plant world and simultaneously strongly present interest in their visual side. This new visibility of elements is reflected in authentic poetic delight and in the “visualizing” form, where the poem also becomes an image on the plane of a sheet of paper. Poems by Miłobędzka are also understood and seen in their visual dimension by others, for example, in graphic realization by Jan Berdyszak in collaboration with Krystyna Miłobędzka (Berdyszak and Miłobędzka 2015).

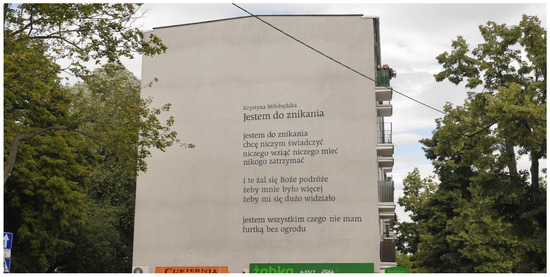

The visuality of Miłobędzka’s poems, is also evidenced by two of them becoming the poems of public space, watched and read by everyone on the route of poetic murals in Poznań or in Puszczykowo. Here, as one can see at the photography of mural at Lodowa street, the two last lines really attest the poet’s attachment to the garden’s metaphysic architecture: jestem wszystkim czego nie mam furtką bez ogrodu (I am all what I have not/ the gate without the garden (Figure 10). The poem in Puszczykowo show the colors play and one more time, the importance of the verb “to be” and its possible senses (Figure 11).

Figure 10.

© photography by Paweł Jędrzejczak. Mural of a poem by Krystyna Miłobędzka, jestem do znikania (I am to disappear) in Lodowa street in Poznań, made in a frame of project by Joanna Pańczak and Tomasza Genowa.

Figure 11.

© photography by Paweł Jędrzejczak. Mural of a poem by Krystyna Miłobędzka, wróć i bądź jeszcze dalej (come back and be still more) on the wall of library in Puszczykowo. The mural was made in a frame of project “Młodzież w działaniu” (Youth in Action), coordinated by Magda Nowicka Chomsk.

Finally, we have a kind of double illustration because the murals on the walls between the trees seems to show us the visual, that is concrete, character of her poetry, like in the example:

| dróżki w ogrodzie | paths in garden |

| (czarne wgłąb) | (black deep inside) |

| (przeskoki, zgłębienia) | (leaps, deep insights) |

| dom przed zniknięciem w drzewach | the house before it vanishes among the trees |

| dom znikający w drzewach | the house vanishing among the trees |

| (Miłobędzka 2013d, pp. 136–37) |

The power of this poetry also lies in its ability to co-create a space viewed and experienced, in many ways, placing the multiplicity (repetitiveness) and singularity (uniqueness) of existence at the center of its interest. Miłobędzka is convincing in her poetic creations and their minimalistic form. She speaks of it with amazement: “I don’t know by what miracle I became interesting to young people. Maybe somewhere in the poems, I managed to—bagatelle! —capture the essence of life” (Borowiec et al. 2009, p. 141). In her original way of composing the visual hortus poems (e.g., Rose), she inscribes herself as a relative in the family of poets, including so ancient poetic garden as these by Johann Wolfgang Goethe (von Goethe 1789), William Blake (Blake 1794), and Emily Dickinson (Dickinson 1856, 1858) and their memorable poetic gardens and at the same time convincing today’s young people.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | All quotes and titles are translated by the author of this paper unless otherwise indicated. Anaglify (Anaglyphs) are the cycle of poems which were first published in periodicals such as: “Ziemia Kaliska”, “Nowa Kultura” and “Twórczość” in the years 1960–1962. |

| 2 | “Współczesność” (Contemporaneity) was the name of the generation of artists and writers making their debut in Poland around 1956 and dominating literary life for the next 10 years. Their work was a reference point for all subsequent generations of writers and literary groups. To this formation belonged, among others: Andrzej Bursa, Stanisław Grochowiak, Miron Białoszewski, Jerzy Harasymowicz, Marek Hłasko, Halina Poświatowska and Edward Stachura. |

| 3 | These are: Spis z natury (Inventory of Nature) (Miłobędzka [1960] 2019), Pokrewne (Related) (Miłobędzka 1970); Dom, pokarmy (Home, Foods) (Miłobędzka 1975), Wykaz treści (Register of Contents) (Miłobędzka 1984), Pamiętam (zapisy stanu wojennego) (I rembember (Martial Law Notes)) (Miłobędzka 1992), Imiesłowy (Participels) (Miłobędzka 2000a), wszystkowiersze (omnipoems) (Miłobędzka 2000b), Przesuwanka (Shiftness) (Miłobędzka 2003), Po krzyku (After Shout) (Miłobędzka 2004), Zbierane 1960–2005 (Gathered 1960–2005) (Miłobędzka 2006), gubione (lost) (Miłobędzka 2008a), zbierane, gubione 1960–2010 (gathered, lost 1960–2010) (Miłobędzka 2010a) dwanaście wierszy w kolorze (twelve poems in color) (Miłobędzka 2012), and poems from multiple volumes of is/am (selected poems 1960/2020) jest/jestem (wiersze wybrane 1960/2020) (Miłobędzka 2020). All quotes and references to Krystyna Miłobędzka’s will refer to the collective edition of poems from 2020 entitled jest/jestem; the first editions are quoted also in the bibliography. |

| 4 | These are: Teatr Jana Dormana (Jan Dorman’s Theater) (Miłobędzka 1990), Przed wierszem. Zapisy dawne i nowe (Before a Poem. Old and New Notes) (Miłobędzka 1994), Siała baba mak. Gry słowne dla teatru (Old Woman Sowed Poppy Seeds. Word Games for Theater). (Miłobędzka 1995), Na wysokiej górze (On the High Mountains) (Miłobędzka and Chmielewska 2014); szare światło. Rozmowy z Krystyną Miłobędzką i Andrzejem Falkiewiczem (grey light. Conversations with Krystyna Miłobędzka and Andrzej Falkiewicz) (Borowiec et al. 2009), W widnokręgu Odmieńca. Teatr, dziecko, kosmogonia. (In the Horizon of Different. Theater, Child, Cosmogonia) (Miłobędzka 2008b), znikam, jestem, (I disappear, I am) (Miłobędzka 2010b), Dwie rozmowy. Oak Park—Puszczykowo—Oak Park (Two Conversations. Oak Park-Puszczykowo-Oak Park) (Falkiewicz et al. 2011), Blisko z Daleka. Listy 1970–2003 (Close from Afar. Letters 1970–2003) (Miłobędzka et al. 2021a). |

| 5 | Among others, the author has received the following awards: the Barbara Sadowska Award (1992), the Culture Foundation Award (1993), the Minister of Culture Award (2001), the Four Columns Literary Award (2003), the Artistic Award of the City of Poznań and the President of the City of Poznań (2009), the Silesius Poetry Award (2013), and the Adam Mickiewicz Poznań Literary Award (2020). |

| 6 | Especially the poem drzewo tak drzewo (the tree yes the three) is an often-interpreted poem (cf. papers on Miłobędzka poetry quoted in this article). |

| 7 | I mean especially two publications: Poezje-Poetry in “2B” in 1999, n° 14 translated by F. Kujawski and A. Sułkowska (Miłobędzka 1999) and a volume Nothing More translated by E. Wójcik-Leese in 2013 (Miłobędzka 2013a). |

References

Primary Source

Figure 1.The Vision of Babylon Garden. 1912. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ogrody_semiramidy.jpg (accessed on 16 July 2022) from book published in 1912 (Petit Larousse).Figure 2. Upper Rhenish Master. c.a. 1410–1420. The Little Garden of Paradise. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Upper_Rhenish_Master_-_The_little_Garden_of_Paradise_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg (accessed on 16 July 2022).Figure 3.The Map of the Garden of Eden. c.a. 1009. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/18757/18757-h/images/map06.jpg (accessed on 18 July 2022).Figure 4. Arcimboldo, Giuseppe. 1573. Autom. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/9/90/Giuseppe_Arcimboldo_-_Autumn_-_WGA00812.jpg (accessed on 18 July 2022).Figure 5. Czyżewski, Tytus. [1920] 1922. Mechaniczny Ogród. Mechaniczny ogród. In Idem, Noc-dzień. Mechaniczny instynkt elektryczny. Kraków: Geberthner i Wolf, p. 24. https://polona.pl/item/noc-dzien-mechaniczny-instynkt-elektryczny,NzIxMzg5NDQ/31/#info:metadata (accessed on 22 March 2022).Figure 6. Iacobus Meydenbach. 1491. Hortus sanitates, Mainz: Meidenbach, p. 9. https://polona.pl/item/hortus-sanitatis,MTExNzkwOTEx/28/#info:metadata (accessed on 17 July 2022).Figure 7. Cover by Markowski, Marcin In: Krystyna Miłobędzka. 2019. Anaglify. In Eadem, Spis z natury. Lusowo: Wydawnictwo Wolno.Figure 8. Miłobędzka, Krystyna. 2020. wiersz róża (poem rose) In Eadem, jest/jestem (is/I am), Lusowo: Wydawnictwo Wolno, pp. 256–57.Figure 9. Miłobędzka, Krystyna. 2020. wiersz zamknięty (closed poem) In Eadem, jest/jestem (is/I am), Lusowo: Wydawnictwo Wolno, p. 258.Figure 10. photography by Jędrzejczak, Paweł. Mural of a poem by Krystyna Miłobędzka, jestem do znikania (I am to desappeare) in Lodowa street in Poznań, made in a frame of project by Joanna Pańczak and Tomasza Genowa.Figure 11. photography by Jędrzejczak, Paweł. Mural of a poem by Krystyna Miłobędzka, wróć i bądź jeszcze dalej (come back and be still more) on the wall of library in Puszczykowo. The mural was made in a frame of project “Młodzież w działaniu” (Youth in Action), coordinated by Magda Nowicka Chomsk.Secondary Source

- Berdyszak, Jan, and Krystyna Miłobędzka. 2015. Jan Berdyszak/Krystyna Miłobędzka. Ostatni Notatnik Malarski/Czytania Notatnika. Edited by Waldemar Andzelm. Lublin: Galeria Sztuki Współczesnej Waldemar Andzelm. [Google Scholar]

- Białoszewski, Miron. 1961. Wywód jestem’u. In Idem, Mylne Wzruszenia. Warszawa: PIW. [Google Scholar]

- Birksted, Jan K. 2003. Landscape History and Theory: From Subject Matter to Analytic Tool. Landscape Review 8: 4–28. [Google Scholar]

- Blake, William. 1794. The Sick Rose. Songs of Innocence and Experiences. Available online: http://erdman.blakearchive.org/#23 (accessed on 30 May 2022).

- Bogalecki, Piotr. 2011. Niedorozmowy. Kategoria niezrozumiałości w poezji Krystyny Miłobędzkiej. Warszawa: Narodowe Centrum Kultury. [Google Scholar]

- Borowiec, Jarosław, ed. 2012. Wielogłos. Krystyna Miłobędzka w recenzjach, szkicach i rozmowach. Wrocław: Biuro Literackie. [Google Scholar]

- Borowiec, Jarosław, Falkiewicz Andrzej, and Miłobędzka Krystyna, eds. 2009. szare światło. Rozmowy z Krystyną Miłobędzką i Andrzejem Falkiewiczem. Wrocław: Biuro Literackie. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings, E. E. 1933. Eimi (I Am). New York: Covici Fried. [Google Scholar]

- Czyżewski, Tytus. 1922. Mechaniczny ogród. In Idem, Noc-dzień. Mechaniczny Instynkt Elektryczny. Kraków: Geberthner i Wolf. First published 1920. [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson, Emily. 1856. When Roses Cease to Bloom, Sir. Available online: https://www.edickinson.org/ (accessed on 23 April 2022).

- Dickinson, Emily. 1858. Nobody Knows this Little Rose. Available online: https://www.edickinson.org/ (accessed on 23 February 2022).

- Falkiewicz, Andrzej, Karpowicz Tymoteusz, and Miłobędzka Krystyna. 2011. Dwie rozmowy. Oak Park—Puszczykowo—Oak Park. (Two Conversations. Oak Park—Puszczykowo—Oak Park). Wrocław: Biuro Literackie. [Google Scholar]

- Fiedorczuk, Julia. 2019. Inne możliwości. O poezji ekologii i polityce. Rozmowy z amerykańskimi poetami. Gdańsk: Wydawnictwo Naukowe Katedra. [Google Scholar]

- Fiedorczuk, Julia, and Gerardo Beltrán. 2020. Ekopoetyka/ Ecopoética/Ecopoetics Ekologiczna obrona poezji/ Una defensa ecológica de la poesía/ An ecological “defence of poetry”. Warszawa: Muzeum Historii Polskiego Ruchu Ludowego. Biblioteka Iberyjska. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault, Michel, and Jay Miskowiec. 1986. Of Other Spaces. Diactrics 16: 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Górniak-Prasnal, Karolina. 2017. Impossible Poetry: Reading Polish Postwar Avant-Garde: Tymoteusz Karpowicz and Krystyna Miłobędzka. Aktuālas Problēmas Literatūras Un Kultūras Pētniecībā 22: 253–69. [Google Scholar]

- Górniak-Prasnal, Karolina, and Katarzyna Kuchowicz. 2015. Motywy roślinne w Anaglifach Krystyny Miłobędzkiej. Maska 27: 117–26. [Google Scholar]

- Grądziel-Wójcik, Joanna. 2008. “Spróbuj zbudować dom ze słów”. O wierszach “niezamieszkanych” Krystyny Miłobędzkiej. In Miłobędzka wielokrotnie. Edited by Piotr Śliwiński. Poznań: WBPiCAK, pp. 21–34. [Google Scholar]

- Gutorow, Jacek. 2011. Księga Zakładek. Wrocław: Biuro Literackie. [Google Scholar]

- Jarzyna, Anita. 2017. Wprowadzenie do post-koiné: Nieantropocentryczne języki poezji. Poznańskie Studia Polonistyczne. Seria Literacka 30: 107–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kałuża, Anna. 2008. Poezja konkretna w sporze z poezją hermetyczną. In Eadem Wola Odróżnienia. O modernistycznej Poezji Jarosława Marka Rymkiewicza, Julii Hartwig i Krystyny Miłobędzkiej. Kraków: Universitas, pp. 199–215. [Google Scholar]

- Koza, Katarzyna. 2020. Rola drzew w poezji Urszuli Zajączkowskiej. Annales Universitas Paedagogicae Cracoviensis. Studia Poetica 8: 286–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lekowska, Daria. 2020. “Wyłaniam kraje kory pękate”. (Współ)drzewna poetyka Krystyny Miłobędzkiej. Annales Universitas Paedagogicae Cracoviensis. Studia Poetica 8: 262–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lihačev, Dimitrij Sergeevič (Lichaczow, Dymitr). 1991. Poezja ogrodów. O semantyce stylów ogrodowo-parkowych. Translated by Budu Russe, and Kaja Sakowicz. Wrocław: Ossolineum. [Google Scholar]

- Majdecki, Longin. 1972. Historia ogrodów. Warszawa: PWN. [Google Scholar]

- Maliszewski, Karol. 2020. Bez zaszeregowania. O nowej poezji kobiet. Kraków: Universitas, pp. 74–75. [Google Scholar]

- Małecki, Wojciech P., and Jarosław Woźniak. 2020. Ecocriticism in Poland: Then and now. Ecozon@, European Journal of Literature, Culture& Enviroment 11: 34–41. [Google Scholar]

- Miłobędzka, Krystyna. 1970. Pokrewne. (Related). Warszawa: Czytelnik. [Google Scholar]

- Miłobędzka, Krystyna. 1975. Dom, Pokarmy. (Home, Foods). Wrocław: Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich. [Google Scholar]

- Miłobędzka, Krystyna. 1984. Wykaz treści (Register of Contents). Warszawa: Czytelnik. [Google Scholar]

- Miłobędzka, Krystyna. 1990. Teatr Jana Dormana (Jan Dorman’s Theater). Poznań: Ogólnopolski Ośrodek Sztuki dla Dzieci i Młodzieży. [Google Scholar]

- Miłobędzka, Krystyna. 1992. Pamiętam. Zapisy Stanu Wojennego. (I remember. Martial Law Notes). Wrocław: Wydawnicwto A. [Google Scholar]

- Miłobędzka, Krystyna. 1994. Przed wierszem. Zapisy dawne i nowe. (Before the Poem. Old and New Notes). Kraków and Warszawa: “Fundacja Brulionu”. [Google Scholar]

- Miłobędzka, Krystyna. 1995. Siała baba mak. Gry słowne dla teatru (Old Woman Sowed the Poppy. Word Games for the Theater). Wrocław: Wydawnictwo A. [Google Scholar]

- Miłobędzka, Krystyna. 1999. Poezje—Poetry. In Collaboration with E. Sułkowska-Bierezin, “2B”, nr 14. Translated by Kujawinski F.. [Google Scholar]

- Miłobędzka, Krystyna. 2000a. Imiesłowy (Partcipels). Wrocław: Wydawnictwo Dolnośląskie. [Google Scholar]

- Miłobędzka, Krystyna. 2000b. wszystkowiersze (omnipoems). Legnica: Biuro Literackie. [Google Scholar]

- Miłobędzka, Krystyna. 2003. Przesuwanka. Legnica: Biuro Literackie. [Google Scholar]

- Miłobędzka, Krystyna. 2004. Po krzyku. (After Shout). Wrocław: Biuro Literackie. [Google Scholar]

- Miłobędzka, Krystyna. 2006. Zbierane (1960–2005). (Gathered 1960–2005). Wrocław: Biuro Literackie. [Google Scholar]

- Miłobędzka, Krystyna. 2008a. Gubione (Lost). Wrocław: Biuro Literackie. [Google Scholar]

- Miłobędzka, Krystyna. 2008b. W widnokręgu Odmieńca. Teatr, dziecko, kosmogonia. (In the Horizon of Different. Theater, Child, Cosmogonia). Wrocław: Biuro Literackie. [Google Scholar]

- Miłobędzka, Krystyna. 2010a. zbierane, gubione (1960–2010). (gathered, lost 1960–2010). Wrocław: Biuro Literackie. [Google Scholar]

- Miłobędzka, Krystyna. 2010b. znikam, jestem. (I disappear, I am). Wrocław: Biuro Literackie. [Google Scholar]

- Miłobędzka, Krystyna. 2012. dwanaście wierszy w kolorze (Twelve Poems in Color). Wrocław: Biuro Literackie. [Google Scholar]

- Miłobędzka, Krystyna. 2013a. Nothing More. Translated by Elżbieta Wójcik-Leese. Todmorden: Arc Publication. [Google Scholar]

- Miłobędzka, Krystyna. 2013b. Inc. drzewo tak drzewo (the tree yes the three). In Nothing More. Translated by Elżbieta Wójcik-Leese. Todmorden: Arc Publication. [Google Scholar]

- Miłobędzka, Krystyna. 2013c. Inc. pisz, pisz… (write, write…). In Nothing More. Translated by Elżbieta Wójcik-Leese. Todmorden: Arc Publication. [Google Scholar]

- Miłobędzka, Krystyna. 2013d. Inc. dróżki w ogrodzie (paths in garden). In Nothing More. Translated by Elżbieta Wójcik-Leese. Todmorden: Arc Publication. [Google Scholar]

- Miłobędzka, Krystyna. 2019. Anaglify (Anaglyphs). In Eadem, Spis z natury (Inventory of Nature). 1. Anaglify (Anaglyphs); 2. Małe mity (Little Mythes); 3. Jesteś samo śpiewa (You are self singing). Lusowo: Wydawnictwo Wolno. First published 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Miłobędzka, Krystyna. 2020. jest/jestem. Wiersze Wybrane 1960/2020, (Is/I Am). Lusowo: Wydawnictwo Wolno, pp. 256–57. [Google Scholar]

- Miłobędzka, Krystyna. 2020a. Inc. Na szybie pokrytej… (Draw two circles…). In Eadem, Anaglify. Lusowo: Wydawnictwo Wolno. First published 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Miłobędzka, Krystyna. 2020b. Co ja robię, patrzę w jest… (What I do, I look in is). In Eadem, Imiesłowy. Lusowo: Wydawnictwo Wolno. First published 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Miłobędzka, Krystyna. 2020c. Inc. Oczy nie widzą głęboko… (Eyes don’t see deeply). In Eadem, Pokrewne. Lusowo: Wydawnictwo Wolno. First published 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Miłobędzka, Krystyna. 2020d. Jestem że widzę że widzę że mijam (I am that I see that I see that I pass). In Eadem, Dom, Pokarmy. Lusowo: Wydawnictwo Wolno. First published 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Miłobędzka, Krystyna. 2020e. Inc. pisz, pisz … (Write, write…). In Eadem, Po krzyku. Lusowo: Wydawnictwo Wolno. First published 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Miłobędzka, Krystyna. 2020f. Inc. Kolory w dzieciństwie… (In childhood colors…). In Eadem, Anaglify. Lusowo: Wydawnictwo Wolno. First published 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Miłobędzka, Krystyna. 2020g. Inc. Ta butelka z sokiem pormarańczowym… (This bottle with orange juce). In Eadem, Anaglify. Lusowo: Wydawnictwo Wolno. First published 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Miłobędzka, Krystyna. 2020h. Roślinne (Vegetal). In Eadem, Pokrewne. Lusowo: Wydawnictwo Wolno. First published 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Miłobędzka, Krystyna. 2020i. Chlorofil (Chlorophyll). In Eadem, Pokrewne. Lusowo: Wydawnictwo Wolno. First published 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Miłobędzka, Krystyna. 2020j. Ogród (Garden). In Eadem, Pokrewne. Lusowo: Wydawnictwo Wolno. First published 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Miłobędzka, Krystyna. 2020k. Narodzenie z oczu (Birth from the Eyes). In Eadem, Pokrewne. Lusowo: Wydawnictwo Wolno. First published 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Miłobędzka, Krystyna. 2020l. Inc. jeszcze do wnuka (still to the grandchild). In Eadem, Imiesłowy. Lusowo: Wydawnictwo Wolno. First published 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Miłobędzka, Krystyna. 2020m. Inc. mówiące mnie drzewo (tree speaking me). In Eadem, dwanaście wierszy w kolorze. Lusowo: Wydawnictwo Wolno. First published 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Miłobędzka, Krystyna. 2020n. Co nie widzi oko gęboko…? (What does not eye see deeply?). In Eadem, dwanaście wierszy w kolorze. Lusowo: Wydawnictwo Wolno. First published 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Miłobędzka, Krystyna. 2020o. Inc. tylko bądź… (Be only). In Eadem, dwanaście wierszy w kolorze. Lusowo: Wydawnictwo Wolno. First published 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Miłobędzka, Krystyna. 2020p. wiersz róża (poem rose). In Eadem, wszystkowiersze. Lusowo: Wydawnictwo Wolno. First published 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Miłobędzka, Krystyna. 2020q. Inc. Mam. Mnie nie ma… (I have. I am not). In Eadem, dwanaście wierszy w kolorze. Lusowo: Wydawnictwo Wolno. First published 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Miłobędzka, Krystyna. 2020r. Inc. wiersz zamknięty (closed poem). In Eadem, wszystkowiersze. Lusowo: Wydawnictwo Wolno. First published 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Miłobędzka Krystyna, Falkiewicz Andrzej, Karpowicz Tymoteusz, and Karpowicz Maria. 2021a. Blisko z daleka. Listy (1970–2003). Wrocław: Ossolineum. [Google Scholar]

- Miłobędzka Krystyna, Falkiewicz Andrzej, Karpowicz Tymoteusz, and Karpowicz Maria. 2021b. Letter nr 132 by Tymoteusz Karpowicz to Andrzej Falkiewicz. (Oak Park, 8 April 1998). 738–39. [Google Scholar]

- Miłobędzka, Krystyna, and Iwona Chmielewska. 2014. Na Wysokiej Górze. (On the High Mountain). Poznań: Wydawnictwo Miejskie Posnania. [Google Scholar]

- Nyczek, Tadeusz. 2008. Mikromakro. In Miłobędzka wielokrotnie. Edited by Piotr Śliwiński. Poznań: WBPiCAK, pp. 175–78. [Google Scholar]

- Orska, Joanna. 2018. Ciało z klocków. Słowo na scenie w twórczości Krystyny Miłobędzkiej. In Nauka chodzenia. Teksty programowe późnej awangardy. Edited by Wojciech Browarny, Paweł Mackiewicz and Joanna Orska. Kraków: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego, vol. 1, pp. 255–85. [Google Scholar]

- Piaget, Jean. 1923. Le Langage et la pensée chez l’enfant. Paris: Delachaux et Niestlé. [Google Scholar]

- Piaget, Jean. 2003. La Représentation du monde chez l’enfant. Paris: Quadrige. First published 1926. [Google Scholar]

- Peiper, Tadeusz. 1972. Nowe usta. Kraków: Wydawnictwo Literackie. First published 1926. [Google Scholar]

- Potocki, Wacław. 1907. Ogród fraszek. Lviv: Towarzystwo Popierania Nauki Polskiej, vols. 1–3. First published 1648. [Google Scholar]

- Prévert, Jacques. 1949. Je suis comme je suis. In Idem, Paroles. Paris: Gallimard. First published 1946. [Google Scholar]

- Rymkiewicz, Jarosław Marek. 1968. Myśli różne o ogrodach. Dzieje jednego toposu. Warszawa: Czytelnik. [Google Scholar]

- Salwa, Mateusz. 2020. Antyogród w ogrodzie. Aspiracje 112: 59–60. [Google Scholar]

- Skurtys, Jakub. 2017. Zamiast Szymborskiej? Krystyna Miłobędzka i źródła współczesnej ekopoezji w Polsce. Teorie przestrzeni 28: 203–19. [Google Scholar]

- Suszek, Ewelina. 2020. Figuracje braku i nieobecności. Miłobędzka—Białoszewski—Kozioł. Kraków: Universitas. [Google Scholar]

- Szafrańska, Małgorzata, ed. 1998. Ogród. Forma. Symbol. Marzenie. Warszawa: Ars Regia—Zamek Królewski w Warszawie. [Google Scholar]

- Szymborska, Wisława. 1986. Jarmark cudów. In Eadem, Ludzie na moście. Warszawa: Czytelnik. [Google Scholar]

- von Goethe, Johann Wolfgang. 1789. Heidenröeselin in: Goethe’s Schriften. Leipzig: Georg Joachim Göschen, vol. 8, pp. 105–6. [Google Scholar]

- Wittgenstein, Ludwig. 1977. Remarks on Colour. Translated by Linda L. McAlister, and Margarete Schättle. Oxford: C.G.E Anscombe. [Google Scholar]

- Wójcik-Leese, Elżbieta. 2006. Poland. Poetry Wales 42: 40–44. [Google Scholar]

- Żurek, Łukasz. 2022. Two Commas and a Hyphen by Krystyna Miłobędzka. Forum Poetyki/Forum of Poetics 27. First published 2017. Available online: http://fp.amu.edu.pl/two-commas-and-a-hyphen-by-krystyna-milobedzka/ (accessed on 8 September 2022).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).