Abstract

This article explores the use and adaptation of the iconographic motif of the waiting servant, known primarily from late Roman wall paintings, mosaics, and other media, within the sphere of Late Antique furnishing textiles. Taking as a case study a fifth- to sixth-century CE hanging in the Art Institute of Chicago’s collection, the first section argues that the addition of elaborate, multihued architectural settings and floral motifs in this hanging and several comparable examples built upon the existing waiting-servant iconography offer an enhanced message of “the good life” within the household. Such compositional elements were rooted in earlier Greek and Roman artistic traditions, namely architectural polychromy and the visual interplay between artifice and reality. However, they also exemplify the Late Antique “jeweled style”, an aesthetic characterized by dazzling visual and polychromatic effects and an interest in artistic mimicry of other media. Striking visual parallels between the waiting-servant hangings and contemporary painted interiors suggest that textiles were considered on par with permanent media and operated in a system of cross-media artistic exchange. The article concludes with a consideration of the materiality of the Chicago hanging and its potential functions within a Late Antique residence, exploring how its portability as a woven object encouraged its flexible use within the home and allowed it to convey and even amplify particular messages through its juxtaposition with other objects, architecture, or people.

Keywords:

Late Antique art; late Roman art; textiles; iconography; materiality; servant; banquet; domestic space; jeweled style; Egypt 1. Introduction

Among the Art Institute of Chicago’s encyclopedic holdings, one of the lesser known areas of the collection is its corpus of Late Antique textiles from Egypt.1 Comprising over 150 fragmentary works dated from approximately the third to seventh centuries CE,2 textiles such as these were originally fabricated either as interior furnishings or decorative elements on garments and are preserved today due to their burial in Egypt’s dry climate.3 The largest and best-preserved example in the Art Institute’s corpus is a fragment of a hanging (Figure 1), currently dated to the fifth to sixth century CE, which was likely used as a furnishing textile in a Late Antique home.4 Remarkable for its large scale, brilliant color, and visually striking composition, it depicts a nearly complete image of a male figure standing in a colorful architectural setting. To date, the hanging has not been the subject of a comprehensive art historical examination, but the current study is intended to rectify this gap. The figure, which was previously identified as a warrior,5 has more recently been interpreted as an example of the iconographic motif of the waiting servant.6 This motif, which is associated with the representation of standing attendants bearing offerings at the banquets of the wealthy, is found initially in a number of wall paintings, mosaics, funerary monuments, and luxury objects dated primarily to the third and fourth centuries CE. Broadly, such images were intended to communicate messages about the patron’s wealth, social standing, and prestige, as well as the hospitality and abundance of the household.7 However, the motif is also attested in a small number of artworks of a later date, particularly furnishing textiles.

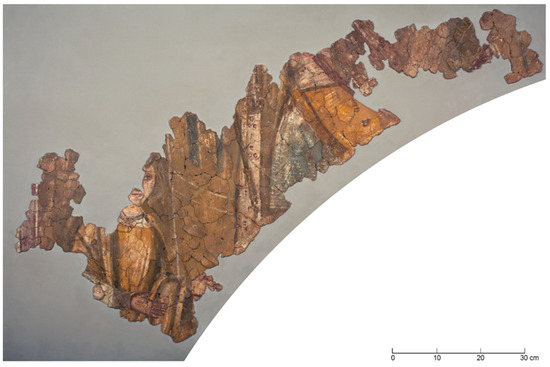

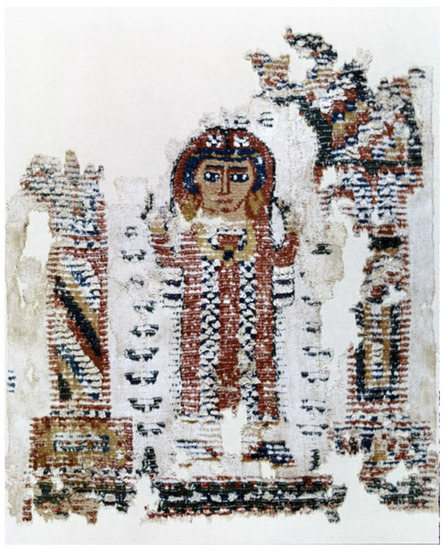

Figure 1.

Fragment of a Hanging, 5th–6th century CE. Byzantine; Egypt. Linen and wool, plain weave with weft uncut pile and embroidered linen pile formed by variations in back and stem stitches; 136.5 × 88.3 cm (53 3/4 × 34 3/4 in.). The Art Institute of Chicago, Grace R. Smith Textile Endowment, 1982.1578.

This article explores the use and adaptation of the motif of the waiting servant in Late Antique furnishing textiles, using the Chicago hanging as a case study through which to consider issues pertaining to its iconography, visuality, and materiality. I begin with an overview of this iconography in the later Roman world and explore its deployment in Late Antique furnishing textiles thought to have been used in domestic contexts. While the primary features of the waiting-servant motif were retained, additional iconographic elements, namely an elaborate architectural setting framing the figure and a series of floral motifs in the background, helped to present an enhanced message of “the good life” within the household. I then address how these additional elements are rooted in earlier Greek and Roman artistic traditions, specifically the polychromy of ancient architecture, as well as the longstanding interest in the visual interplay between the real and the fictive in different artistic media. I then explore how the composition of the Chicago hanging exemplifies a new Late Antique aesthetic system, known as the jeweled style, which is grounded in these earlier traditions and is characterized by an emphasis on variety in color, light, materials, and motifs as well as the transgression of boundaries across media. Works reflecting the jeweled style typically produced magnificent, opulent effects that would imitate and even exceed the experience of the natural world. I conclude by considering the relationship between the materiality (medium, materials, and spatiality) of the Chicago hanging and its potential function within a Late Antique domestic context, exploring how its portability as a pliable, woven object encouraged its flexible use within the home, enabling it to serve a variety of functional and iconographic purposes, through which it could convey and even amplify particular messages through its juxtaposition with other artworks.

2. Overview of the Chicago Hanging

2.1. Physical and Technical Description

The Art Institute’s hanging is the largest and best-preserved object in its corpus of Late Antique textiles.8 Exemplifying many of the characteristics associated with Late Antique art, including frontality, abstraction, and a tendency toward flatness, the hanging depicts a male figure, represented at roughly 1/3 life-size scale, who stands within a colorful architectural setting. He stands frontally with his head turned sharply to his right, with his eyes glancing in the same direction. His expression, rendered in contours, is solemn, if not severe. He has a pale complexion with smooth cheeks, suggesting that he is either a clean-shaven adult or an unbearded youth. From a distance his dark hair seems to be closely cropped, but upon closer inspection it extends below his shoulders, a feature that supports the likelihood that he falls into the latter group.9

The figure wears a brightly colored costume, the most outstanding part of which is his green, knee-length tunic. It is cinched at the waist with a red belt and adorned with a number of yellow decorative elements characteristic of the clothing of the period, including orbiculi (roundels) at the shoulders, clavi (narrow vertical bands running down from the shoulders), paired cuffbands at the wrist, and tabulae (squares) at the bottom edge.10 Beneath his tunic he wears yellow tights as well as blue shoes, the tops of which are brown. The figure stands with his arms raised to chest height and extended outward, and the absence of his now-missing hands prevents the clear identification of the objects or attributes he may have been shown holding.

The composition also includes an elaborate, polychromatic architectural setting rendered in different hues of red, yellow, orange, and green. It comprises two red columns, each with a narrow, vertical green band at the interior. Each column is encircled with three golden (yellow) bands that are embellished with rectangular motifs, nearly all of which are green and likely represent gemstones.11 The columns stand on similarly golden bases, beneath which is a ground line of crenelated rectangles in alternating colors. Atop the columns is a delicate, rainbow-colored arch, the width of which does not fully extend from column to column, leading to the question of the form that its capitals once took. Framed by this elaborate structure, the male figure stands within a nearly empty field, save for the alternating motifs that populate the background. These include rainbow-striped, heart-shaped, floral motifs and small rectangular motifs in red and green, the latter of which echo the forms of the presumed gemstones of the architecture. Although the figure seems to float in this fictive space, he is more likely intended to be set back from the arch, with his reduced scale suggesting his distance from the viewer.

The hanging is woven of linen and wool, materials that are indigenous to Egypt (Mayer Thurman 1984, p. 54; 1992, p. 11). Because parts of both selvages (the finishing edges at the right and left sides of the textile) are preserved, it is clear that it represents a complete loom width, and thus the maximum width of the textile. The design was created using discontinuous supplementary wool wefts, which were incorporated during the weaving process as loops of yarn that project from the plain weave foundation to form tufts or pile, which was left uncut.12 The design appeared in weft-loop pile only on the front, making this the primary viewing side, although the associated wool wefts would presumably also have been visible on the back but not in loop form, creating a sort of flattened effect of the same design.13 Supplementary weft-loop pile was frequently used in furnishing textiles in Egyptian households because it added softness and warmth, yet from an artistic standpoint it could also be used to introduce color gradations that could create impressionistic and perspectival effects (Krody 2019, pp. 86–87).14

Despite the flatness of the composition as a whole, the weaver achieved a notable sense of three-dimensionality in the depiction of certain elements by employing lighter and darker shades of certain colors of yarn to suggest shading and depth.15 This is apparent in the modeling of the figure’s hair and face, with a brownish-purple used in the hair crowning his head and brown in the longer hair in back, as well as pink and red used to highlight the contours of his nose and jawline. It is seen more clearly in his clothing: contrasts between light and dark green in the lower part of the tunic as well as light and dark yellow in the tights suggest the three-dimensionality of his body.16 Such contrasts would seem to indicate that he stands near a light source located at the center or just to the viewer’s right of center. Similar approaches to shading are seen in the red columns, which gradually shift to a lighter red as they reach the interior, as well as in the golden bands encircling the columns, which transition from yellow to orange from top to bottom, suggesting shadows on their undersides. While this masterful use of color creates an illusion of three-dimensionality, the weft-loop pile itself further enhances this impression, as it quite literally stands out in low relief from the plain weave ground. In this way, its materials and medium contribute to the overall illusionistic effect.17

2.2. Function and Context

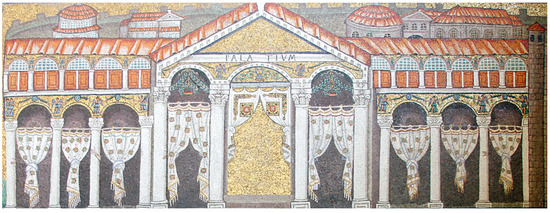

Historically, the Chicago textile was identified in neutral terms as a hanging (Mayer Thurman 1992, p. 11),18 a function that is supported by its large size and the scale of its motifs.19 It might have been displayed against a wall in a stationary manner, serving as both insulation and decoration. However, it more likely hung in a doorway or colonnade, where it was fully opened in order to display its imagery. Such an arrangement in a doorway or colonnade would have allowed the textile to serve as a temporary wall, screen, or barrier, an issue to which I return below.20 In this way, its function likely differed from that of other types of furnishing textiles that could be tied back, functioning comparably to what would be described today as a curtain. An example of this arrangement is seen in the curtains represented in a mosaic depicting the Palace of Theodoric from the Church of Sant’Apollinare Nuovo in Ravenna (Figure 2). In this mosaic, nearly all of the curtains include repeated, decorative designs that would not be obscured when knotted or pulled to the side.21 A similar arrangement is seen in a hanging in Boston depicting an ostiarius (doorkeeper) (Figure 3), who pulls a curtain back from an elaborately adorned arcade. Here the folds of the curtain are indicated by its accordion-like, alternating light and dark vertical stripes as well as the zigzag pattern of its red horizontal bands.22

Figure 2.

Wall mosaic depicting the Palace of Theodoric, c. 526 CE. Byzantine; Basilica of Sant’Apollinare Nuovo, Ravenna. © José Luiz Bernardes Ribeiro. Digital image available under Creative Commons license CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Theodoric%27s_Palace_-_Sant%27Apollinare_Nuovo_-_Ravenna_2016_(crop).jpg; downloaded 7 September 2021).

Figure 3.

Fragment of a hanging: Ostiarius Drawing a Curtain, probably 5th century CE. Eastern Mediterranean, probably Egyptian, late Roman. Linen; tapestry-woven; linen and wool yarns; 188 × 93.5 cm (73 × 36 13/16 in.). Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Charles Potter Kling Fund, 57.180. Photograph © [2022] Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, MA, USA.

While the Chicago textile’s scale and technique of manufacture provide some clue to its basic function as a hanging, its iconography, specifically the depiction of a waiting servant, is thought to suggest its original display context, that of the domestic sphere. To be sure, despite the fact that nearly 1000 Late Antique residences have been excavated throughout the Mediterranean world (Bowes 2010, p. 11), furnishing textiles are not usually found in situ and intact in such domestic contexts (Thomas 2002, p. 42).23 Rather, the majority of extant furnishing textiles (and also dress textiles) can be traced to the cemeteries of ancient Egypt, where they were preserved due to their secondary use as grave goods, often as burial shrouds (Stephenson 2014, p. 12; Bühl 2019, pp. 15–16).24 Such textiles were long described as “Coptic” due to their Egyptian manufacture and presumed Christian associations; this term has since fallen out of scholarly favor when used specifically in reference to Late Antique textiles.25 Such textiles came to light primarily through excavations carried out in Egypt in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, many of which were conducted by amateur archaeologists who did not adequately document the burial contexts. This resulted in the loss of invaluable information pertaining the textiles’ dating as well as their relationships to specific sites, patrons, and other objects (Trilling 1982, p. 14; Thomas 1990, p. 1; 2007, pp. 137–45). Thousands of such examples, many of which lack precise information pertaining to their archaeological provenience, flooded the art market and entered private and museum collections worldwide.26 The Art Institute’s hanging was similarly purchased on the art market, and its precise findspot remains unknown.27 Nevertheless, the comprehensive consideration of its iconography, style, and materials can potentially reveal the ways it in which it was understood and used in its original, Late Antique domestic context.

3. The Waiting-Servant Motif

The male figure in this hanging was recently identified as an example of the iconographic motif of the “waiting servant”. This motif, which was extensively addressed by Katherine Dunbabin in her pioneering study on the topic (Dunbabin 2003b), is associated with the representation of the household attendants, or more accurately, the presumed domestic slaves, who served at the convivia (banquets) of the Roman elite.28

For the purposes of this article, I follow Dunbabin in the use of the term “servant” or “attendant” as opposed to “slave”, as my focus is primarily on the function of the figures represented in the works, rather than their legal status (Dunbabin 2003b, p. 443, n. 1). However, it is important to recognize that slaves were possessions, not unlike the contents of the houses in which they served (Joshel and Petersen 2014, pp. 9, 27). Viewed as an instrumentum vocale (“speaking tool”), the ancient slave was, “at the most basic level…regarded as an object whose very body could be employed by the master to accomplish tasks” (Lenski 2013, p. 130).29 Wealthy owners could count slaves numbering in the dozens, if not hundreds among their property, all of which enhanced the image of their economic standing and prestige (D’Arms 1991, p. 171; Joshel and Petersen 2014, p. 27). Patrons had direct control over the actions of their slaves, and as such they assigned both their servile duties and the locations in which their work took place. Owners also attempted to control aspects of their slaves’ behavior, from their performance of specific tasks to the timing of their movements and gestures, even limiting their ability to speak, laugh, or sneeze.30 They could also determine the physical appearances of slaves, dressing them in specialized clothing, requiring them to don distinctive hairstyles, and expecting them to groom themselves in certain ways.31

Images of household servants offer visual evidence of the cultivated appearances, tasks, and potential gestures and poses of actual slaves. Typically shown well-dressed, elegantly groomed, and bearing wine, food, and other offerings or attributes, these figures obediently stand mute and motionless, perpetually awaiting a command from their patron.32 While images of both male and female servants are attested,33 there is a particular emphasis on youthful male figures who are richly dressed, physically attractive, often shown with long hair and smooth cheeks, both of which are suggestive of their age, and tasked with serving wine (D’Arms 1991, 173; Dunbabin 2003a, p. 151; 2003b, p. 454–58). The actual individuals on which such images were based were described by contemporary authors as pueri delicati, a term used for attractive, often androgynous, youthful male slaves (Pollini 1999, p. 34; 2002, p. 55; Rooijakkers 2018, p. 49).34 In the artistic record, they have been identified specifically as an iconographic type of luxury servants (Fless 1995, pp. 38–45, 56–63).35 Regardless of the specifics of their physical appearance, such images of household servants were often isolated within simple rectangular panels or frames, a compositional element that Dunbabin suggested provides the figures a more ceremonious and honorific effect characteristic of the period.36

The waiting-servant motif initially appeared almost exclusively in Roman literary sources of the early imperial period that focused on the banquets of the wealthy (D’Arms 1991). It was not until the third and fourth centuries CE that the motif became more commonly represented, at which time it was employed in variety of media, including wall paintings, mosaics, funerary sculptures, and luxury objects. Such artworks were found in a range of contexts both in Rome and the provinces (Dunbabin 2003b). Broadly, images of waiting servants were intended to communicate messages about the patron’s wealth, social standing, and prestige, as well as the hospitality of the household, conveying an overall image of “the good life”.37 In the case of images of banquet servants in particular, they evoked the presence of actual attendants, who “were no less essential for the successful achievement of even a small dinner than the variety of the food served, the fineness of the wines, and the elaborateness and richness of the drinking and serving vessels” (Dunbabin 2003b, p. 444).38 In this way, it is likely that waiting-servant imagery went hand in hand with the longstanding tradition of representing not only the abundant food and produce available within one’s home and on one’s estate, but also the prepared meals and fine dinnerware that were critical to a lavish meal. This theme was particularly apparent in mosaics incorporating xenia motifs, as seen in a group of eight mosaic panels in Chicago (Figure 4), which feature depictions of food and objects associated with dining, such as an almond cake, a fish on a golden or bronze platter, and a bound rooster about to be prepared for a meal. The group also includes two representations of personified seasons, alluding to the cyclical nature of time and agricultural regeneration, which resulted in the bounty of nature that was enjoyed at the Roman table.39

Figure 4.

Eight Fragments from a Mosaic Pavement, 2nd century CE. Roman; Rome. Stone, glass, and mortar. Starting from top left: Mosaic Floor Panel Depicting a Fish on a Platter, 28.9 × 36.8 × 6 cm (11 3/8 × 14 1/2 × 2 3/8 in.), 159.2012; Mosaic Floor Panel Depicting a Bound Rooster, 28.6 × 37.5 × 6.4 cm (11 1/4 × 14 3/4 × 2 1/2 in.), 160.2012; Mosaic Floor Panel Depicting an Almond Cake, 27 × 27 × 6.4 cm (10 5/8 × 10 5/8 × 2 1/2 in.), 164.2012; Mosaic Floor Panel Depicting a Loaf of Bread or a Platter, 29.5 × 34.9 × 6 cm (11 5/8 × 13 3/4 × 2 3/8 in.), 166.2012; Mosaic Floor Panel Depicting a Brazier, 27.9 × 27.9 × 5.1 cm (11 × 11 × 2 in.), 165.2012; Mosaic Floor Panel Depicting a Sack, 27.9 × 27.9 × 5.1 cm (11 × 11 × 2 in.), 163.2012; Mosaic Floor Panel Depicting a Personification of a Season, 28.9 × 28.9 × 7 cm (11 3/8 × 11 3/8 × 2 3/4 in.), 161.2012; and Mosaic Floor Panel Depicting a Personification of a Season, 28.9 × 28.9 × 5.1 cm (11 3/8 × 11 3/8 × 2 in.), 162.2012. The Art Institute of Chicago, promised gift of Lynn Hauser and Neil Ross.

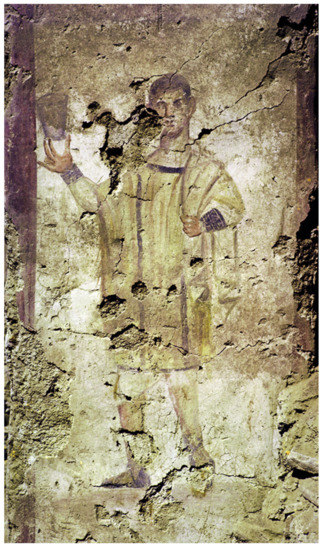

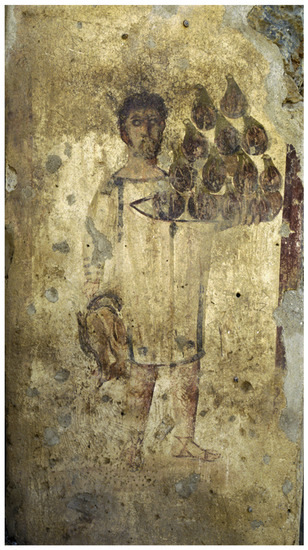

Not surprisingly, images of the waiting servant have been found in a number of domestic contexts, a setting where their subject matter would have been entirely appropriate.40 For example, the wall paintings in the Odeion Terrace House at Ephesos, which are dated to the first half of the fourth century CE, include images of two well-dressed male servants, each of whom is set within an individual panel.41 The first servant, an unbearded, youthful male (Figure 5), holds a glass beaker in one hand and a towel in the other, indicating his role as a wine servant. The second attendant (Figure 6), a bearded, mature male, holds a large plate of figs and a slaughtered fowl, perhaps suggesting his role in the preparation of food.42 Standing frontally and directing their gazes at the viewer, these painted servants were placed strategically to greet the actual guests who were entering the adjacent, well-appointed room, presumably in a direct allusion to the dining festivities that likely occurred within the home (Dunbabin 2003b, p. 449; Zimmermann and Ladstätter 2011, p. 168).43

Figure 5.

Wall painting depicting a servant with a glass beaker and a towel, 4th century CE. Ephesos, Odeion Terrace House. Efes Müzesi Selçuk. Photo: OeAW-OeAI/Norbert Zimmermann.

Figure 6.

Wall painting depicting a servant holding a plate of figs and a slaughtered fowl, 4th century CE. Ephesos, Odeion Terrace House. Photo: OeAW-OeAI/Norbert Zimmermann.

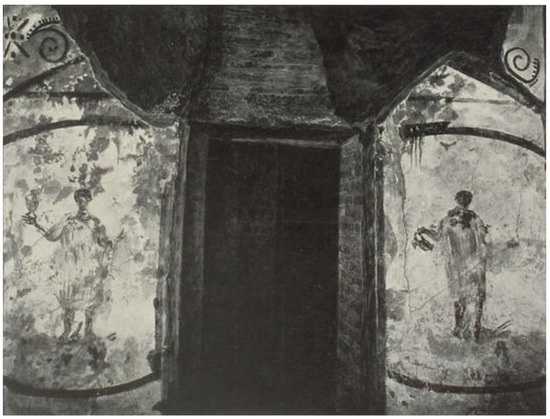

Such images also appear in funerary contexts, not only on sarcophagi and other funerary monuments but also in tomb paintings, both pagan and Christian.44 The paintings in cubiculum 10 of the Christian catacomb of Peter and Marcellinus in Rome (Figure 7), which are dated to the second half of the third century CE, include two figures identified as servants. They hold a jug and a cup, respectively, and are set within individual panels. Here, however, they appear to serve not the viewer but rather the deceased, who is likely the subject of an adjacent image of a reclining woman with a drinking vessel, beneath which are two smaller figures of individuals with their arms raised in the orans (praying) pose.45 Such images reflect the multivalency of banqueting iconography through its associations with this life and the next, as well as the continued use of the waiting-servant motif in Christian contexts.46

Figure 7.

Wall painting depicting servants, second half of 3rd century CE. Rome, Catacombs of Peter and Marcellinus, cubiculum 10, entrance wall. Photo: Wilpert (1903), p. 107.3. Public domain (https://doi.org/10.11588/diglit.1339#0109; downloaded 10 September 2021).

Finally, the waiting-servant motif was used outside of banqueting contexts to display more general ideas about wealth, status, and luxury, as for example on The Projecta Casket in the British Museum (Figure 8), a lavish object created around 380 CE to transport an elite female patron’s bathing apparatus to the public baths.47 On the body of the casket is a procession of elegantly dressed male and female servants who carry offerings and various toilet articles to their female patron, the seated figure at the center of the casket’s front side. Similar to the framed images of servants in domestic and funerary wall paintings, these servants are shown in an isolated, compartmentalized fashion: each one stands within a single bay of the larger architectural setting, which is composed of columns that support alternating arches and gables. The use of architectural elements to frame each servant, isolating them individually while simultaneously displaying them within a larger group, would appear to foreshadow a critical element of later depictions of the waiting-servant motif in textiles, as is addressed below.

Figure 8.

The Projecta Casket, c. 380 CE. Late Roman; Rome. Silver, gold; 28.6 × 56 × 48.8 cm (11 1/4 × 22 × 19 1/4 in.). The British Museum, 1866,1229.1. © The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) license.

While the aforementioned examples are largely assigned to the date range of the third and fourth centuries CE noted by Dunbabin, later examples of the motif are known in secular and sacred contexts but are far less numerous.48 At least one painted example from a domestic context can be added to this corpus: a fragmentary painting identified as an image of a draped female figure,49 perhaps a servant, from the MMS/S residence at Sardis, which was constructed around 400 CE (Figure 9).50 The female figure, which is dated both stylistically and archaeologically to the late fifth to early sixth century CE, was found in space E, which was identified as both an entrance and organizing court for the home (Greenewalt et al. 1995, p. 482).51 Here the figure was displayed on the west side of the room, on the south springing of the lower east face of a brick arch. She holds what appears to be a towel over her arm, perhaps suggesting a role as a wine servant and alluding to the dining that occurred in the adjacent triclinium (room D) similar to the painted images of servants at Ephesos discussed above. She gestures with raised hands to the viewer’s right, seemingly directing their gaze toward what may be images of patterned, multicolored curtains as well as the adjacent arch.52 The late fifth to early sixth century CE dating of the painting and its association with a domestic setting are significant as they suggest the continued use and relevance of waiting-servant imagery in residences well into Late Antiquity. While the Sardis figure is to this author’s knowledge the only late example of this motif in a wall painting from a domestic context, additional examples are found in the more flexible and portable medium of textiles.

Figure 9.

Painting of a female servant, late 5th to early 6th century CE. Excavated in MMS/S residence, Sardis, west wall. Sardis inv. WP21.003. © Archaeological Exploration of Sardis/President and Fellows of Harvard College.

4. The Waiting-Servant Motif in Late Antique Furnishing Textiles: Enhanced Iconography of “The Good Life”

Although not included in Dunbabin’s previous studies, the Chicago hanging and several other closely related examples of Late Antique textiles clearly incorporate the iconographic motif of the waiting servant and its associations with wealth, status, and hospitality, as well as additional elements that support its overarching message of “the good life”. Comparative examples belong to the collections of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston (Figure 10),53 the Musée du Louvre in Paris (Figure 11),54 and (formerly) the Skulpturensammlung und Museum für Byzantinische Kunst of the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin (Figure 12).55 All four hangings have generally been dated within the range of the fourth to sixth century CE,56 and they bear striking similarities in terms of their iconography, scale, materials, and method of manufacture.57 Additionally, all four textiles are generally thought to have been discovered in Egypt.58 While there are undoubtedly some minor variations among the textiles, their clear formal, stylistic, and technical similarities raise the question of whether they might have been produced in the same workshop, albeit perhaps by different weavers.59 Indeed, it is possible that large hangings such as these were purchased and hung in sets, rather than as individual pieces (Stauffer 1995, p. 10). While this is not to suggest that the four textiles considered here were intentionally created as a discrete group, I would argue that they might have belonged to assemblages similar to this in their original display contexts, in which the number of hangings likely varied depending on the needs of the intended space as well as the patron’s preferences and financial means.

Figure 10.

Fragment of a curtain, 4th–6th century CE. Late Roman. Linen plain weave with polychromy wool weft pile loops; 97.5 × 131 cm (38 3/8 × 51 9/16 in.). Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Charles Potter Kling Fund, 49.313. Photograph © [2022] Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Figure 11.

Hanging, 420–570 CE. Byzantine; Egypt. Loop weaving in wool and linen; 75 × 69 cm (29 1/2 × 27 1/8 in.). Musée du Louvre, E 10530. Photo: Thierry Ollivier. © RMN-Grand Palais/Art Resource, NY.

Figure 12.

Curtain, 5th–6th century CE. Byzantine; Egypt. Weft-loop pile in wool on plain-weave linen ground; 85 × 88 cm (33 1/2 × 34 5/8 in.). Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Skulpturensammlung und Museum für Byzantinische Kunst (formerly in the Kaiser-Friedrich-Museum, lost in World War II), 9223 (after Wulff and Volbach 1926, p. 2). © Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Skulpturensammlung und Museum für Byzantinische Kunst.

4.1. Woven Images of Waiting Servants

From an iconographic standpoint, many of the features characteristic of the waiting-servant motif outlined by Dunbabin are also seen in the male figures represented in these four textiles: each is depicted with long hair and smooth cheeks, wearing a colorful, embellished tunic, and standing in a largely frontal pose.60 With their heads turned, all seem to guide the viewer within the space, perhaps to a door or another point of interest.61 Alternatively, one wonders whether they may intentionally avert their gazes from the viewer, suggesting their direct engagement only when called upon, given their roles as “human props” at a banquet.62 With the exception of the Chicago figure, who is missing his hands and any potential accompanying attributes, the figures from the other three textiles retain the objects associated with their particular occupation: a ladle and a wine bowl for the Boston figure, and candlesticks for the Paris and Berlin figures. The latter may provide a clue to what the Chicago figure held, as he is shown with similarly outstretched arms.63 With their well-groomed appearances and servile attributes, all four figures clearly evoke the iconographic type of the luxury household servant and its associated messages, as discussed above.

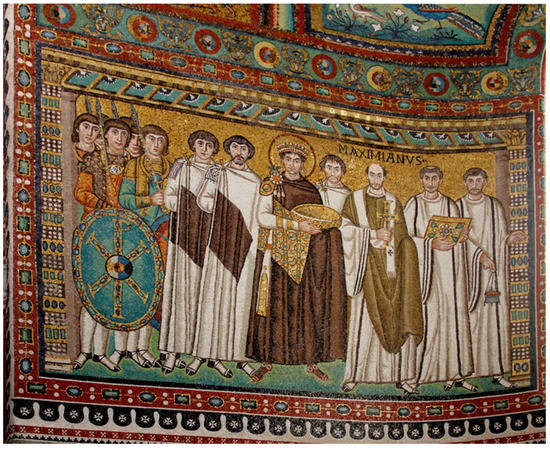

In the case of the Chicago figure, his servile status also appears to be supported by the color of his tunic. Comparable costumes involving green tunics and yellow decorative elements are employed in other contemporary images of servants, as illustrated in the ostiarius hanging in Boston noted above (See Figure 3 above).64 This male servant, who stands adjacent to an arcade as he pulls back the furnishing textile hung within it, wears an even more elaborate variation on the costume of the Chicago figure, complete with a jeweled belt, long yellow clavi, yellow orbiculi with interlocking geometric motifs, and red tights (Salmon 1969, pp. 146–47; Kondoleon 2016, p. 88). The green-and-yellow tunic is also seen in a mosaic dated to the sixth century CE in the Basilica of San Vitale at Ravenna, where a member of Emperor Justinian’s retinue, the third figure to the left of the emperor, wears a similar garment that also includes yellow cuffbands at the wrists (Figure 13).65 The wearing of the green tunic by household servants also finds some earlier literary support. In Petronius’s Satyricon (Petronius, Satyricon 28), the narrator, Encolpius, briefly makes note of a porter wearing a green tunic and a cherry-colored belt, who stands near the doorway while shelling peas into a silver dish.66 Such visual and literary references to the trope of a servant in a green tunic, standing near or within a doorway, help to bolster the likelihood that the Chicago figure can be identified as a luxury household attendant. Beyond this small number of examples that connect green tunics with servile status, it is unclear whether the color was chosen to carry a more specific meaning depending on the patron and the context.67

Figure 13.

Mosaic depicting Emperor Justinian and his attendants, 6th century CE. Byzantine; Basilica of San Vitale, Ravenna. © José Luiz Bernardes Ribeiro. Digital image available under Creative Commons license CC BY-SA 4.0. (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Mosaic_of_Justinian_I_-_San_Vitale_-_Ravenna_2016.jpg; downloaded 13 September 2021).

4.2. Additional Elements: The Architectural Setting and Floral Motifs

While the figure of the waiting servant appears to retain its earlier iconographic significance in these later textiles, additional elements that appear in each composition, namely, the lavish architectural setting and the floral motifs dispersed through the background, undoubtedly enhanced the figure’s message of wealth, status, prestige, and hospitality.

Among the four hangings, the architectural features are preserved to varying degrees, but each includes boldly colored columns encircled with golden bands, some of which are bejeweled.68 Additional opulent elements appearing among one or more textiles include the golden column bases, multihued capitals, and a crowning element in the form of either an open gable or an arch.69 On a formal level, such architectural settings can be seen as a more elaborate version of the simple rectangular panels that framed individual figures of waiting servants in earlier paintings.70 Here, however, they undoubtedly perform a more meaningful role than that of simple framing devices. More specifically, their depictions of colorful, extravagant architecture, complete with golden and jeweled embellishments, may evoke actual architectural elements found in elite homes.71 Such depictions of magnificent architecture may have reinforced the iconographic message of the wealth and abundance of the household already suggested by the motif of the servant. As noted by Thelma K. Thomas, “real and fictive (simulated) architectural features, often depicted in textiles as gilded and decorated with jewels, framed these subjects as explicit (and aspirational) references to luxury and other aspects of “the good life” of the household” (Thomas 2016b, p. 22).72

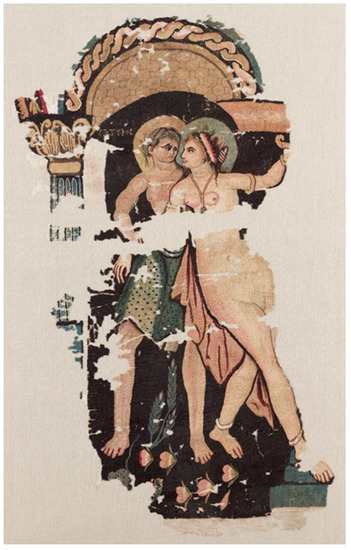

This iconographic theme is further emphasized through the addition of floral elements in the background in the form of the rainbow-hued, heart-shaped motifs.73 These elements, which are found in all four textiles, can be identified as abstracted depictions of roses.74 Their placement in the background appears to allude to the practice of scattering rose petals on the ground during a banquet, a tradition associated with the concept of hospitality.75 Similar images of roses can be seen in a textile dated to the fourth century CE in the Cleveland Museum of Art (Figure 14), which depicts a satyr and a maenad reveling during Dionysiac festivities, reinforcing the flowers’ association with convivial gatherings.76 In the Cleveland hanging, the leaves and stems are also represented, making the identification of such heart-shaped motifs as flowers explicit. Comparable floral motifs are also seen in contemporary Late Antique and early Byzantine mosaics, where the motif’s identification as a representation of petals strewn on the floor is more immediately apparent, as seen in a fragment of a mosaic pavement depicting a giraffe and handler in the Art Institute’s collection (Figure 15).77

Figure 14.

Fragment with Satyr and Maenad, 4th century CE. Byzantine; Egypt. Undyed linen and dyed wool; plain weave ground with tapestry weave; overall: 139 × 86.4 cm (54 3/4 × 34 in.); mounted: 153.6 × 100.4 × 3.9 cm (60 1/2 × 39 1/2 × 1 9/16 in.). The Cleveland Museum of Art, Purchase from the J. H. Wade Fund, 1975.6. Digital image available under Creative Commons license CC0 1.0.

Figure 15.

Mosaic Fragment with Man Leading a Giraffe, 5th century CE. Byzantine; Syria or Lebanon. Stone in mortar; 170.8 × 167 × 6.35 cm (67 1/4 × 65 3/4 × 2 1/2 in.). The Art Institute of Chicago, Gift of Mrs. Robert B. Mayer, 1993.345.

Building upon late Roman images that focused on the servant itself, I would argue that the combination of motifs appearing in the waiting-servant hangings, figural, architectural, and floral, conveyed an enhanced message of the wealth, status, and prestige of the patron as well as the hospitality and abundance within the home. Moreover, the more complex imagery of the hangings may have even been intended to offer a closer approximation of some of the visual aspects of the experience of attending a banquet: one can imagine the viewer observing the attendants silently waiting in the wings for their patron’s command, or marveling at the lavish architectural setting of the host’s residence, or even glancing down upon the rose petals strewn about the floor while taking in the overall spectacle of the event.

4.3. Formal Parallels: Personifications of Abundance and Orant Figures

The basic composition featured in the waiting-servant hangings, with a single figure set within a distinctive architectural setting, does not appear to have been unique to the type. Rather, it is frequently used in textiles and other media of the period to represent other subjects. In some instances, the figures are allegorical in nature and convey a message similar to that of the waiting servant through their associations with the themes of abundance, prosperity, and “the good life”.78 For example, a hanging in the collection of Dumbarton Oaks in Washington, DC (Figure 16) depicts two elegantly dressed, haloed male figures standing within a bejeweled arcade who bear gifts that potentially identify them as personifications of the seasons or the months of the year.79 On the left is a man in Persian-style dress, who holds an elongated flask and a bowl resembling that in the Boston waiting-servant hanging. On the right is a man carrying a large fish and pomegranates, who wears a mantle over a belted tunic embellished with the standard decorative elements.80 They stand within gem-encrusted arcades against a background incorporating vegetal motifs. Of particular interest are the schematic leaves surrounding the figure on the right, which resemble the abstracted rose petals found in the waiting-servant hangings. Similar imagery is found in a number of comparable hangings in other museum collections, which may have been produced within the same workshop.81

Figure 16.

Fragment of a Hanging with Two Figures in Arcades, 6th century CE. Byzantine; Egypt. Tapestry weave in polychrome wool; H. (warp) 42.0 cm × W. (weft) 63.2 cm (16 9/16 × 24 7/8 in.). Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, Washington, DC, BZ.1970.43. © Dumbarton Oaks, Byzantine Collection, Washington, DC, USA.

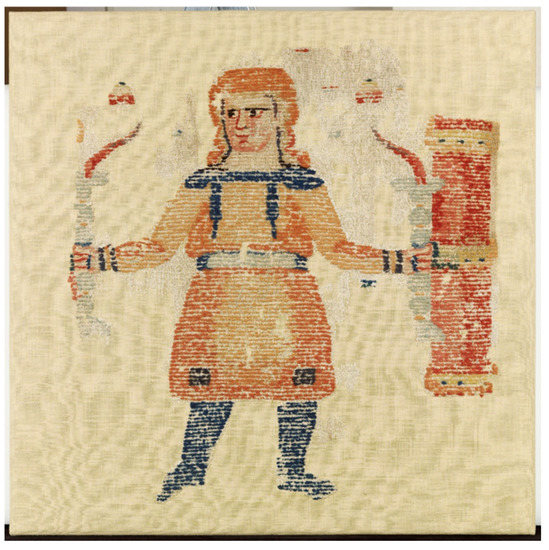

Other examples employ similar design schemes but incorporate Christian iconography, specifically that of the orant (praying figure). This imagery appears in other weft-loop pile textiles of the period, such as a curtain panel in Detroit, which depicts a young girl, identified as such by her earrings and the bulla around her neck, standing in the prayer pose (Figure 17).82 Although the Detroit textile is much smaller in scale than the waiting-servant hangings, perhaps indicating that it once belonged to a larger textile, its subject also stands frontally with her arms raised and is framed by a patterned, multi-hued arcade.

Figure 17.

Curtain Panel, possibly 5th century CE. Coptic; Egyptian. Linen and wool; 69.9 × 63.5 × 50.2 cm (27 1/2 × 25 × 19 3/4 in.). Detroit Institute of Arts, Founders Society Purchase, Octavia W. Bates Fund, 46.75.

A larger-scale example showing the repetition of the orant motif within an elaborate architectural setting can be found in the fourth-century CE wall paintings from the Roman villa at Lullingstone, Kent, England (Figure 18), which adorned a house church set within the residence (Meates 1987).83 On the west wall is a scene depicting six figures with their arms raised in the position of prayer, each of which is individually framed within a polychromatic arcade embellished with different patterns.84 The Lullingstone figures’ poses seem to resemble those of the figures on the Chicago and Paris hangings, who stand with their arms above the waist and extended outward. In the Paris hanging, however, the candlesticks in the figure’s hands make his identification as a servant explicit. Beneath this main zone of the west wall at Lullingstone is a dado zone with paintings that have been identified as images of colorful open roses set against an imitation marble background (Meates 1987, p. 33). One wonders if this dado level was, comparable to the background of the waiting-servant hangings, intended to represent a floor covered with rose petals. If so, perhaps the multivalency of this image allowed it to convey a similarly broad message of hospitality and celebration but with a focus on otherworldly pleasures rather than those of the terrestrial realm, given the function of the space as a house church.85

Figure 18.

Wall painting from Villa at Lullingstone, Kent, England, 4th century CE. Romano-British. Length: 420 cm (165 3/8 in.). The British Museum, 1967,0407.1.b © The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) license.

At a minimum, there appears to be a basic, formal relationship between these figural motifs, the waiting servant, allegorical figures evoking “the good life”, and the orant—, which to this author’s knowledge has yet to be fully explored in the scholarly literature, particularly with regard to their use in different social, cultural, and religious contexts.86 Nevertheless, it seems reasonable to suggest that one of their compositional similarities, the use of an elaborate architectural setting as a framing device, can be attributed to their participation in a broader, Late Antique aesthetic system.

5. Earlier Traditions of Artifice and Reality and the Late Antique Jeweled Style

Turning back to the waiting-servant textiles, it is important to recognize that their architectural elements and floral motifs perform more than simply reinforce the iconographic message of wealth, status, and hospitality; they also situate these hangings firmly within well-established traditions in Greek and Roman art and architecture. First, the depiction of boldly colored columns in the hangings reflects the longstanding practice of integrating color into architecture and architectural decoration. Frequently, this architectural polychromy was achieved through the use of paint,87 as seen in the rich tradition of wall painting as well as in the remains of stuccoed and painted columns found in a number of houses at Pompeii and Herculaneum.88 The taste for color in architecture gained further popularity in the Roman imperial period and was enhanced through the addition of mosaic tesserae, colored stones, and other materials.89

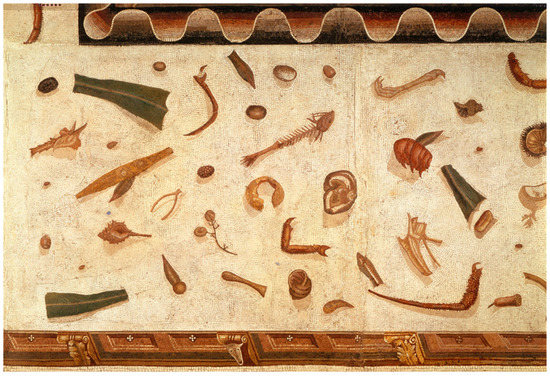

Second, the architectural settings and floral motifs seen in the waiting-servant hangings also reflect the enduring taste for illusionistic effects that can trick the eye and delight the viewer, albeit in a more stylized, abstracted manner characteristic of Late Antiquity. Such effects can be traced back in part to the Hellenistic conceit of the ‘unswept floor’ (asàrotos òikos) mosaic, which depicted the detritus covering the floor after a luxurious banquet, a type also attested in the Roman empire (Figure 19).90 This interest in the visual interplay between artifice and reality found particular favor among Roman audiences, and such visual games were played especially in the medium of wall painting.91 This tradition began with the first Pompeian masonry style, in which paint was used to mimic costly colored marbles, and it flourished in the second Pompeian architectural style, with its focus on the creation of elaborate, colorful architecture that framed illusionistic and often fantastical vistas. This painterly play between real and pictorial space is exemplified in the first-century BCE wall paintings from Room M (the cubiculum) of the Villa of Publius Fannius Synistor at Boscoreale (Figure 20), where painted pilasters frame perspectival views of townscapes, colonnaded buildings, and sacred precincts enlivened with statuary and rich vegetation, creating a fictive expanse that extended beyond the wall itself.92 This Roman visual delight in artistic mimicry, trompe l’oeil effects, and toying with the boundaries between the natural and created worlds carried on throughout the Roman period to varying degrees and in different ways.93

Figure 19.

Signed by Heraklitos, detail of mosaic depicting ‘unswept floor’ (asàrotos òikos), 2nd century CE. Musei Vaticani, Museo Gregoriano Profano, 10132. Photo Credit: Scala/Art Resource, NY.

Figure 20.

Cubiculum M, Villa of Publius Fannius Synistor, Boscoreale, view of west wall, c. 50–40 BCE. Roman. Fresco; room dimensions: 8 ft. 8 1/2 in. × 10 ft. 11 1/2 in. × 19 ft. 1 7/8 in. (265.4 × 334 × 583.9 cm). Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund, 03.14.13a–g. Digital image available under Creative Commons license CC0 1.0.

By Late Antiquity, these longstanding artistic traditions laid the groundwork for a new aesthetic system characterized primarily by an emphasis on variety, color, contrast, and opulence, now described as the “jeweled style” (Roberts 1989). In his 1989 publication, The Jeweled Style: Poetry and Poetics in Late Antiquity, Michael Roberts first described this aesthetic, identifying it primarily within period literary sources but also finding parallels in the visual arts, particularly in mosaics, architectural sculpture, sarcophagi, ivories, and manuscripts. Such artworks could dazzle the viewer with their brilliant, polychromatic effects and variety of motifs, patterns, colors, and materials.94 Additional characteristics of the style included an emphasis on abstraction, repetition, and a tendency to break a composition into “self-contained, highly elaborated panels or registers [that allow the viewer]…to admire the play of brilliance and color between compositional units” (Roberts 1989, p. 112).

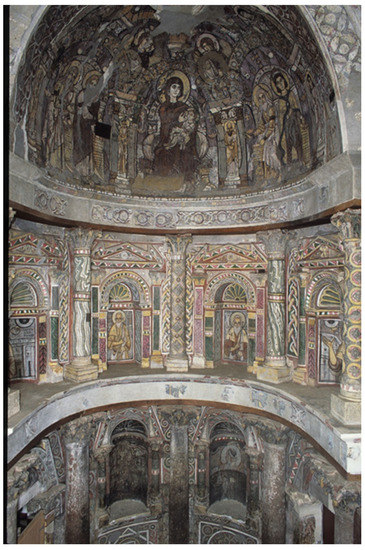

A particularly illustrative example of the Late Antique jeweled style can be found in the sixth-century CE paintings in the Red Monastery church at Sohag in Egypt (Figure 21). In the trilobed eastern end of the church, or triconch, are two stories of architectural sculpture comprising curved and square niches with decorative gables that are framed by pilasters, half-columns, and columns. The interior largely retains its paintings comprising vegetal and geometric motifs, also described as “ornamental” paintings, which are generally dated to its second phase of painted architectural decoration.95 These paintings appear in a riotous array of colors and patterns, which densely populate both the two-dimensional surfaces of the walls and the three-dimensional surfaces of the architectural elements. Many of the niches also include figural paintings depicting Christian subjects, which are attributed to the slightly later, third phase of painting (c. sixth century CE).96 Hearkening to earlier illusionistic tendencies, many of the vegetal and geometric paintings used trompe l’oeil effects to mimic textiles, mosaics, molded stucco, and colored marbles. Moreover, the organization of the interior into registers comprising individual, richly painted niches exemplifies Roberts’ emphasis on separating the elements of a composition into discrete units to enhance the visual effect of color and brilliance.97

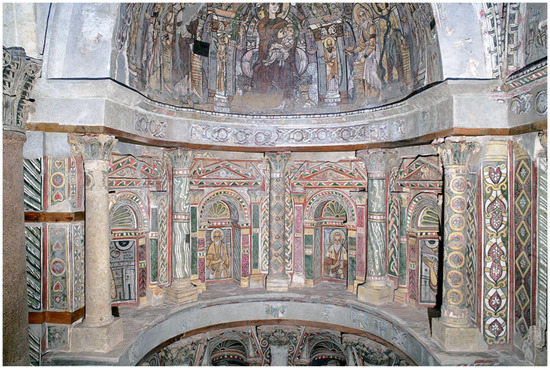

Figure 21.

Interior of the Red Monastery Church, Sohag, Egypt, northern lobe of the triconch, paintings dated c. 6th century CE. Reproduced by permission of the American Research Center in Egypt, Inc. (ARCE). This project was funded by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). Photo: Patrick Godeau.

In her extensive studies of the Red Monastery church’s architectural polychromy, Elizabeth Bolman expanded upon the concept of the jeweled style first outlined by Roberts to explore the aesthetic principles behind its opulent decoration, considering how authors from the Justinianic period emphasized the importance of variety as a driving principle when evaluating architectural interiors, specifically in terms of their diversity of color, light, decorative patterns, and materials (Bolman 2006, 2010, 2016c).98 In particular, different patterns and motifs embellished all surfaces, reflecting a horror vacui aesthetic that diverged from Roman wall paintings of the preceding periods, which typically included some fields of solid color.99 Such variety was valued not only for its extravagance but also for its playfulness.

Woven fabrics produced in Late Antiquity also strongly reflect the qualities associated with the jeweled style. Thelma K. Thomas emphasized how the materials and techniques used in textiles created dazzling visual and polychromatic effects and even allowed them to expertly imitate other media. These qualities were acknowledged in contemporary literary sources describing public and private contexts as well as religious and secular spaces, reflecting the omnipresence of this aesthetic in Late Antiquity (Thomas 2002). More recently, Elizabeth Dospěl Williams argued for the need to recast the jeweled style as an aesthetic system concerned not only with visual effects but also with artistic processes and materiality (making, medium, and spatiality). In particular, Williams suggested that Late Antique audiences valued textiles both for their “artistic bravura, as artists pushed against the limits of their materials and superseded them” and the resulting visual qualities (Dospěl Williams 2018, p. 37).

Applying these concepts to the waiting-servant hangings, it is apparent that they exemplify the main characteristics of the Late Antique jeweled style. For example, the Chicago hanging clearly reflects the principle of variety in its use of rich colors, which in turn are modulated to convey different qualities of light shining on the figure and the architectural setting. Moreover, the design itself covers the majority of the plain weave ground, reinforcing a “more is more” aesthetic by leaving no major sections of the textile unadorned. Such an effect was undoubtedly intentional, as the elements rendered with supplementary wefts were not critical to the structure of the textile.

Finally, the Chicago hanging’s materials illusionistically and playfully subvert the boundaries with other media by mimicking a variety of different materials. For example, the dyed wool of the loop pile imitates more costly, lavish materials, including colored stone (perhaps porphyry) in the red columns, as well as gold and gemstones in the bands that encircle them. It also simulates more fragile, organic materials, such as colorful rose petals. Even the depiction of a delicate rainbow arch above the columns participates in this visual game in evocation of an ephemeral, atmospheric event, which was transformed into a solid architectural element.100 More broadly, it was suggested that the use of the weft-loop pile technique, which allows for the creation of rich, coloristic effects through the deliberate juxtaposition of blocks of specific colors side by side, intentionally resembles the impressionistic appearance of polychrome mosaics.101 The other three textiles of the group, although not identical to the Chicago hanging, clearly participate in the same aesthetic system. Collectively, such varied and colorful elements would have created an impressive visual spectacle, in which the aesthetic effect of the entire composition outweighed that of any single motif. In this way, its visual impact was, similar to its iconographic message, enhanced and amplified by the combination of its different components.

Based on this brief overview of the vegetal and geometric paintings from the Red Monastery church at Sohag and the corpus of waiting-servant hangings, one cannot help but notice that they bear striking stylistic similarities to one another. To provide just one comparison, certain aspects of the Chicago hanging seem to mirror features of one particular niche at the Red Monastery church, specifically the niche located second from the left on the second register of the northern lobe (Figure 22). This niche, which depicts the monastic father Shenoute in a bust-length portrait (Bolman and Szymańska 2016, p. 165), similarly incorporates a colorful architectural setting: it comprises illusionistically painted red columns encircled with golden bands, which are embellished with green rectangular motifs suggesting gemstones. Both columns sit atop yellow column bases. On the interior sides of the niche are tall, rectangular panels that were painted to resemble cipollino verde.102 Turning back to the Chicago hanging, one wonders whether the narrow green bands that sit just inside of the red columns can in fact represent such panels, albeit in an abstracted, reduced form. Alternatively, they may instead depict shading at the interior of the columns. Moreover, while the niche at the Red Monastery church incorporates a colorful painted braid in its arch rather than a rainbow as in the Chicago hanging, neither of these features are capable of functioning in reality as structural elements in actual architecture. Consequently, their use in these instances allows them to destabilize their viewers’ perception of the spaces in which they were displayed (Bolman 2016c, p. 127).

Figure 22.

Interior of the Red Monastery Church, Sohag, Egypt, northern lobe of the triconch, detail of second register, paintings dated c. 6th century CE. This project was funded by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). Photo: Arnaldo Vescovo.

Given the remarkable visual similarities between the waiting-servant hangings and the Red Monastery church’s architectural polychromy, along with their roughly comparable date ranges and Egyptian provenience, it is tantalizing to consider the possibility that the artists who produced these works were operating within a system of cross-media artistic exchange. To be sure, it is important to recognize that such exchange did not always occur unidirectionally from “major” genres such as wall paintings and mosaics to the so-called “minor” arts such as textiles. Rather, iconographic exchange was multidirectional and nonlinear, and the portability of textiles allowed them to function as important intermediaries in this process (Dospěl Williams 2018, p. 36).103 While the precise relationship between the Red Monastery church paintings and the textiles, if any, will never be known, their striking visual similarities support the argument that the textiles can and should be viewed as on par with more permanent media.104 They reflect the same aesthetic preferences of the period and their artists’ mastery over their respective media, and they were similarly appreciated in their own right for their unique material properties.105 Moreover, it is important to recognize that textiles were undoubtedly integral to the adornment of interior settings of this period, both sacred and secular, public and private, complementing and augmenting the messages conveyed by paintings, mosaics, and other media displayed in a given space.

6. Conclusions: Function and Materiality in the Domestic Context

In the concluding section, I address issues pertaining to the function and materiality (medium, materials, and spatiality) of Late Antique furnishing textiles in order to consider how the Chicago hanging was likely used and understood in its domestic context. In particular, I explore how its portability as a pliable woven object was critical to its flexible use within the home, allowing it to serve different functions while also helping to convey or even amplify particular iconographic messages through its potential juxtaposition with other objects, architecture, or even people.

As noted above, there is an unfortunate dearth of textiles from excavated Late Antique domestic contexts, leading to considerable challenges in understanding precisely how such furnishings functioned. However, it is clear from written sources and pictorial representations of textiles in other media that they served a critical role in Late Antique domestic space (Stephenson 2014). Recent exhibitions on Late Antique furnishing textiles, including Designing Identity: The Power of Textiles in Late Antiquity at the Institute for the Study of the Ancient World at New York University in 2016 (Thomas 2016a) and Woven Interiors: Furnishing Early Medieval Egypt at the Textile Museum at George Washington University in 2019 (Bühl et al. 2019), along with a number of other recent scholarly publications, have rightfully called attention to the numerous roles, both functional and iconographic, that furnishing textiles performed within the home.106 These pathbreaking studies have paved the way for a more holistic approach that views textiles as equal to wall paintings, mosaics, and sculpture in their ability to convey messages about the patron and the household through their imagery, in addition to their use in structuring social relations within the Late Antique home.107

Beyond their iconographic meaning, furnishing textiles served many physical and environmental functions within the home: they buffered climate, light, and sound; they added color, texture, and warmth to the hard surfaces of architecture and furniture; and they transformed the appearance of an interior spatial shell by covering walls and other surfaces.108 By virtue of their materiality, furnishing textiles undoubtedly enhanced the sensorial experience of the domestic space in which they were displayed and used. For example, as tactile objects, furnishing textiles likely created an environment that encouraged touch, in turn promoting a haptic experience.109 Textiles also could have altered the auditory experience of a space by absorbing sound or reducing noises. From an olfactory standpoint, images such as the roses in the Chicago hanging and its counterparts could have invited the viewer to imagine oneself taking in the flowers’ sweet fragrance. In the case of the Boston hanging, even the depiction of a servant with a ladle and bowl brimming with wine could also have inspired the viewer’s gustatory senses.110

In addition to elevating the sensorial experience of a space, furnishing textiles also regulated movement by creating temporary walls and doors, closing passageways, and subdividing rooms.111 The use of textiles to control movement and access within the home may be related in part to an increasing emphasis in Late Antiquity with distinctions in social hierarchies, as well as a growing preoccupation with privacy and visibility and the practices of concealing and revealing, as reflected in both domestic and religious contexts.112

Perhaps unsurprisingly, many Late Antique furnishing textiles prominently feature architectural elements, including arcades and columns (Figure 23).113 Such designs blurred the line between real and fictive architecture by transforming a space both physically and pictorially. For example, woven architectural elements, which served no structural purpose (unlike the actual architecture), could be used to visually enlarge a small space, or to make a large room feel more private and intimate. In this way, textiles “offered flexible, movable units that could expand or contract space and also carry meaningful imagery” (Kondoleon 2016, p. 93). However, unlike wall paintings and mosaics that remained static in the spaces in which they were displayed, textiles could be shifted among the different spaces of the house depending on the needs of the patron or the occasion.114 Moreover, their materials and medium as woven fabrics undoubtedly facilitated a subtle form of movement by the textiles themselves, as light winds or perhaps even the movement of passersby would have created enough of a breeze to gently shift or sway the textile, creating a dynamic yet fleeting effect.115 Such spatial and material considerations are critical to a more comprehensive approach to textiles that views them not simply as carriers of imagery and meaning but rather as objects that were valued by contemporary viewers both for their multi-functionality and flexibility as woven, three-dimensional objects.116

Figure 23.

Hanging with Polychrome Columns, 5th–6th century CE. Found Egypt, near Damietta. Linen, wool; tapestry weave; overall: H. 90 1/2 in. (229.9 cm), W. 61 1/2 in. (156.2 cm). Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Arthur S. Vernay Inc., 22.124.3. Digital image available under Creative Commons license CC0 1.0.

The Chicago hanging, similar to other Late Antique furnishing textiles from Egypt, might have served different functions within the home. If it hung on a wall, the hanging itself might have been more stationary in its arrangement, and the colorful architectural setting in which the figure stands would have visually expanded the room beyond the wall itself. Alternatively, if it were hung in a doorway, arcade, or peristyle, its woven architectural elements undoubtedly would have enlivened the appearance of the actual architectural elements with its bold color and fictive jeweled adornments. In this way, it might have created a sort of layering or nesting effect resembling that of the architectural polychromy at Sohag (see Figure 21 and Figure 22 above). Moreover, the hanging’s medium and materials would have further enhanced its three-dimensional appearance. Specifically, and as noted earlier, the use of a thick, weft-loop pile in the creation of the design would have allowed it to stand out from the plain weave ground, creating an illusionistic effect that could potentially trick the viewer’s eye into temporarily reading the woven elements as actual architecture, depending on the viewing conditions.117

Given the prominence of the waiting-servant motif in the Chicago hanging, which has long been associated with the institution of the banquet, it seems reasonable that it would have been displayed in a space that could have been used for dining and entertaining (Thomas 2016b, p. 34). It is clear that the Roman practice of banqueting continued into Late Antiquity,118 at which patrons would host their friends and clients in the lavishly adorned settings of their homes in a literal feast for the senses. Such events provided opportunities for educated and engaging conversation among attendees, which drew on their command of paideia (classical education and culture),119 and they also incorporated diverse forms of entertainment.120 More important, they featured elaborate meals presented on costly tableware,121 which were served by elegantly dressed and well-groomed attendants, the physical appearances of which might have resembled those of the figures in the waiting-servant hangings.

Numerous forms of evidence reveal aspects of Late Antique dining practices. This includes contemporary literary sources, artworks depicting convivial feasts, and the survival of actual furnishings employed at such events, including silver and glass tableware, dining couches, tables, and other equipment and accoutrements.122 The archaeological evidence of Late Antique houses throughout the Mediterranean also reflects the continuation of banqueting practices. To be sure, Late Antique houses appear to have followed the model of earlier Roman residences, in which spaces were used multifunctionally. More specifically, banqueting practices might not have been limited to the spaces identified by contemporary scholars as dining or reception spaces based on their form, scale, location, and adornment.123 That said, many Late Antique houses incorporated one or more apses, a feature that could accommodate the placement of a type of semicircular dining couch, known as a stibadium or sigma, the popularity of which overtook that of the traditional triclinium with its three rectangular couches by the late empire (Dunbabin 1991). In many houses with multiple apses, such as those with three apses arranged in the form of a triconch, the banqueters seated on stibadia would frequently overlook a central space used both by entertainers as well as servants attending to the diners’ needs.124 This type of layout placed the visual spectacle of the banquet front and center before the guests, in turn making a clear allusion to the patron’s access to all of the trappings of a successful event.125

If the Chicago hanging was indeed used in a dining room as part of the functional and iconographic apparatus of the banquet, one can imagine that additional factors might have contributed to the viewer’s overall experience of its imagery and materiality. For example, the time of day and weather conditions undoubtedly had an effect on its reception, particularly in the evening hours when viewed under the dim light of an oil lamp. Similarly, reflections of lamplight and other furnishings off the highly polished silver tableware in the banquet setting might have contributed to the overall dazzling effect. Even the room’s location within the house could have impacted the viewing experience, as its proximity to a courtyard or other outdoor-adjacent space could have promoted the hanging’s movement in the breeze. This type of placement might even have enhanced the trompe l’oeil effect of the design itself by providing the figure and the flowers in the background with a sense of subtle and playful movement.126 There is also the likelihood that the viewer, as a guest at a banquet, was consuming wine (and potentially copious amounts of it). For an inebriated guest, the boundaries between artifice and reality might have been blurred even further, particularly with regard to the presence of actual servants and their woven counterparts. While the former might have obediently and silently stood motionless between tasks, the latter were permanently fixed in this form, providing a visual model of servile ideals for the actual servants (Lenski 2013, p. 147).

As noted above, it was suggested that large furnishing textiles such as the Chicago hanging were purchased and hung not as individual pieces, but rather in sets (Stauffer 1995, p. 10). The Chicago hanging could very well have functioned as one of a group of comparable hangings displayed within an elite dining setting. If this were the case, it seems reasonable that there were some intentional differences in the figures’ appearances, dress, attributes, and architectural settings. Such a grouping would not only have reinforced the jeweled-style emphasis on visual variety, but it also might have created the illusion that the patron had a large crowd of attendants serving diverse occupations at their disposal, further enhancing the presentation of their wealth and prestige among their peers, clients, and guests.127

As Thelma K. Thomas suggests, the physical impossibility of compositions such as these “teasingly opens an imaginative realm, inviting the viewer to envision herself there” (Thomas 2016b, p. 22). In the case of the Chicago hanging, and its counterparts in the other hangings, the presence of the figures who emphatically turn their heads in either direction would seem to direct the viewer’s eye into this fictional expanse, and perhaps also within the room itself, a task undoubtedly undertaken by the servants operating within the space. When combined with the actual servants in a residence, and perhaps even in conjunction with additional images in wall paintings or floor mosaics depicting servants or other allegorical figures, this multiplication of attendants of different types (both real and fictive) would surely have had a rhetorical, amplifying effect, enhancing the display of the patron’s wealth, status, and prestige, as well as the message of the abundance, hospitality, and “the good life” experienced within the household.128

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the staff at the Art Institute of Chicago for their kind assistance and support of my research on this topic, particularly the departments of the Arts of the Ancient Mediterranean and Byzantium, Textiles, Conservation and Science, and Imaging. I would also like to thank the organizers of the Ancient Painting and Decorative Media Interest Group workshop at the 2021 Annual Meeting of the Archaeological Institute of America for accepting the paper on which this article was based. Special thanks are due to Elizabeth Dospěl Williams for very generously sharing her knowledge and insight into the broader topic of Late Antique furnishing textiles. Finally, I am grateful to the volume editors for their support of this article as well as the two anonymous peer reviewers for their critical comments and helpful suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | To date, the Art Institute of Chicago’s holdings in Late Antique textiles from Egypt, which are housed in the museum’s Textiles Department, remain largely unpublished and relatively unknown in the scholarly community. Brief references to the collection are made in (Mayer Thurman 1984, p. 54) and (Mayer Thurman 1992, pp. 11–13). However, parts of the collection were included in the “Census of Byzantine Textiles in North America”, a subproject of the “Byzantine Object Census” started in 1938 and largely concluded by 1943, which is currently held in the Image and Field Work Archives of Dumbarton Oaks in Washington, DC. Special thanks to Elizabeth Dospěl Williams and Stephanie Caruso for informing me of this resource. |

| 2 | Generally, the period identified as “Late Antiquity”, which covers both the later Roman empire and the early Byzantine empire, is defined as extending from the third to seventh century CE. See (Weitzmann 1979; Stauffer 1995, pp. 6–7; Thomas 2016a, p. 11). Some scholars suggest that the period had a shorter duration; for example, for a range of c. 200–500 CE, see (Stephenson 2014, p. 3); for a range of 300–500 CE, see (Elsner 2004, p. 271). However, others suggest it covers a broader timeframe; see (Bowersock et al. 1999, p. ix) for a range of 250–800 CE. For a succinct summary of the degree of overlap between the terms Late Antique, late Roman, and early Byzantine as well as the implications of such terminology, see (Trilling 1982, pp. 11–13). On the arbitrary nature of such terminology, see (Cameron 1993, pp. 7–8). |

| 3 | On the discovery of Late Antique clothing and furnishing textiles in burials in Egypt, see (Thompson 1971, p. 1; Thomas 1990, pp. 1–2; Bühl 2019, p. 15). |

| 4 | Fragment of a Hanging, 5th–6th century CE. Byzantine; Egypt. Linen and wool, plain weave with weft uncut pile and embroidered linen pile formed by variations in back and stem stitches; 136.5 × 88.3 cm (53 3/4 × 34 3/4 in.). The Art Institute of Chicago, Grace R. Smith Textile Endowment, 1982.1578. |

| 5 | See (Art Institute of Chicago 1983, p. 18; 2009, p. 318; Mayer Thurman 1984, p. 54; 1992, p. 11; Hali Magazine 1985). In recent years, the figure has no longer been identified explicitly as a warrior. See Manchester for a more general identification of the figure as a “man” (Manchester 2012, p. 102). |

| 6 | To the current author’s knowledge, the first reference to the Chicago figure as an image of a servant appears in (Dospěl Williams 2015, pp. 14–15). See also (Thomas 2016b, pp. 22, 24, 34; Rooijakkers 2018, p. 47; Dospěl Williams 2019b, pp. 38, 60, cat. 23). Rutschowscaya identifies a similar figure in a textile in the Musée du Louvre as a “person (a priest?)”; see (Rutschowscaya 1990, p. 52). See also Section 4 below for further discussion of the hanging in the Louvre. |

| 7 | For Dunbabin’s pioneering article on the motif of the waiting servant, see (Dunbabin 2003b). For a brief summary of the issues addressed in this article, see (Dunbabin 2003a, pp. 150–56). |

| 8 | The hanging was purchased on the art market in 1982 from the Merrin Gallery (then known as the Edward H. Merrin Gallery) in New York. Curatorial object file, Textiles Department, Art Institute of Chicago. |

| 9 | For further discussion, see Section 3 below. |

| 10 | For the suggestion that the weaver very carefully depicted the details of the male figure’s tunic, see (Dospěl Williams 2019b, p. 60). For a useful diagram illustrating the placement of the different types of decorative elements on the basic Late Antique tunic, see (Thomas 2016b, p. 44, Figure 1–1.3). |

| 11 | Upon close observation of the textile, the topmost band of each column does not fully encircle the column itself, as it ends abruptly upon reaching the vertical green band at the interior. Additionally, on the right column, the lowermost ring has a green rectangle on the left and a blue rectangle on the right. The reasoning behind these design decisions is unclear, but it does not appear to be related to any technical considerations associated with its construction. In the case of the blue rectangle in particular, one wonders whether the weaver intentionally introduced an element of variety with the use of a different colored yarn or if this was instead due to practical matters, e.g., a lack of green yarn to complete the composition. Rare examples of gilded bronze appliques incorporating gemstones, which likely served as architectural attachments, were found in the Horti Lamiani in Rome. See (Zink 2019, Figure 26). |

| 12 | On the construction of the hanging, see (Mayer Thurman 1984, p. 54; 1992, p. 11). |

| 13 | The hanging is permanently stitched to fabric that wraps around a wood stretcher, meaning it is not possible to view the back. Special thanks to Melinda Watt for her insight into the construction of the hanging and the likely appearance of the back, which she suggests would have resembled a “worn-down rug”. |

| 14 | On the uses of weft-loop pile in both furnishings and clothing, see (Colburn 2019). |

| 15 | On the difficulty of achieving this three-dimensional effect in weaving, see (Mayer Thurman 1984, p. 54; 1992, p. 11). |

| 16 | One also wonders whether the brown upper part of each of the blue shoes was intended to represent a light source shining on the tops of the figure’s feet, or if the brown elements should instead be identified as part of his footwear. |

| 17 | On the use of the weft-loop pile technique to create three-dimensional effects, see (Kondoleon 2016, p. 88). |

| 18 | For the identification of the Chicago textile as a curtain or a hanging, see (Mayer Thurman 1984, p. 54). There is considerable scholarly debate about the proper nomenclature to use when identifying furnishing textiles (Schrenk 2009; Stephenson 2014, pp. 12–18). See also (Schrenk 2004, pp. 23–145) for the identification of various types of furnishing textiles in the collection of the Abegg-Stiftung, Riggisberg, based on technical and iconographic analyses. On the ancient vocabulary used to describe furnishing textiles, see (Clarysse and Geens 2009, pp. 39–41). |

| 19 | On the role of the scale (both in terms of the textile itself as well as that of its motifs) in helping distinguish between garments and furnishings, see (Dospěl Williams 2018, p. 33). |

| 20 | See Section 6 below. |

| 21 | On the depiction of curtains in this mosaic, see (De Moor and Fluck 2009, p. 9; Stephenson 2014, p. 21). |

| 22 | On this hanging, see (Salmon 1969, p. 146; Maguire 1999, p. 244; De Moor and Fluck 2009, p. 11; Kondoleon 2016, p. 88; Bühl 2019, p. 20). |

| 23 | The remains of fittings to hang furnishing textiles including rods, hooks, and hoops, have been found in earlier Roman and Late Antique domestic contexts as well as in sacred spaces, for example in Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome and Hagia Sophia in Istanbul. See (Stephenson 2014, especially pp. 12–13, 18–21; Bühl 2019, p. 16). |

| 24 | It is important to recognize that textiles found in Egypt were not necessarily fabricated there (Trilling 1982, p. 17) as examples of Roman and Late Antique textiles have also been discovered in Syria, the Middle East, and the coastal area of the Black Sea; see (Stauffer 1995, pp. 7–8). Textiles found in Egypt and elsewhere may also have been imported, as reflected in their materials, weaving techniques, ornamentation, or in the case of garments, the style of clothing. See especially (Thomas 2017). |

| 25 | Most recently, see (Bühl et al. 2019, p. 11). |

| 26 | For recent perspectives on the collecting of Late Antique textiles from Egypt in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, with a particular focus on major collections in the United States, see the essays in Part 2 of (Thomas 2016a). See also (Thomas 2007, pp. 137–45). |

| 27 | See n. 8 above for provenance information. |

| 28 | For an overview of the occupations, responsibilities, and treatment of slaves at Roman banquets, see (D’Arms 1991). |

| 29 | In De Re Rustica (1.17.1), Varro identifies slaves as “speaking tools” in the context of discussing the three types of instruments necessary for the management of the Roman estate: alii [dividunt] in tres partes, instrumenti genus vocale et semivocale et mutum, vocale, in quo sunt servi, semivocale, in quo sunt boves, mutum, in quo sunt plaustra (“Others divide them into three categories: the articulate sort of tool, the inarticulate, and the mute; the articulate includes slaves, the inarticulate cattle, and the mute wagons”), as translated in (Lenski 2013, p. 148, n. 5). |

| 30 | On this restriction of movement as a “geography of containment”, one aspects of which is the “choreography of slave movement”, see (Joshel and Petersen 2014, pp. 8–13). |

| 31 | For references to specific literary passages, see (Joshel and Petersen 2014, p. 9, n. 33). |