Abstract

Since its publication in 1964, Australians have used the title of Donald Horne’s book, The Lucky Country, as a term of self-reflective endearment to express the social and economic benefits afforded to the population by the country’s wealth of geographical and environmental advantages. These same advantages, combined with strict border closures, have proven invaluable in protecting Australia from the ravages of the global COVID-19 pandemic, in comparison to many other countries. However, elements of Australia’s arts sector have not been so fortunate. The financial damage of pandemic-driven closures of exhibitions, art events, museums, and art businesses has been compounded by complex government stimulus packages that have excluded many contracted arts workers. Contrarily, a booming fine art auction market and commercial gallery sector driven by stay-at-home local collectors demonstrated remarkable resilience considering the extraordinary circumstances. Nonetheless, this resilience must be contextualised against a decade of underperformance in the Australian art market, fed by the negative impact of national taxation policies and a dearth of Federal government support for the visual arts sector. This paper examines the complex and contradictory landscape of the art market in Australia during the global pandemic, including the extension of pre-pandemic trends towards digitalisation and internationalisation. Drawing on qualitative and quantitative analysis, the paper concludes that Australia is indeed a ‘lucky country’, and that whilst lockdowns have driven stay-at-home collectors to kick-start the local art market, an overdue digital pivot also offers future opportunities in the aftermath of the pandemic for national and international growth.

1. Introduction

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, Australia’s second most populous city, Melbourne, was awarded the title of ‘World’s most liveable city’ on seven consecutive occasions. By mid-October 2021, it became internationally renowned as the ‘most locked down city in the world’ due to multiple government lockdown mandates totalling 262 days across nineteen months. Taking advantage of the country’s natural geographic defence as an island, the Australian government closed the border of the country, prohibiting incoming travel and preventing citizens from departing. Moreover, internal borders quickly slammed shut as well, as local governments juggled political and economic concerns with health implications for their citizens. Whilst Melbourne’s ignominious change of title goes some way to explain the enormous social and financial impact of the Federal and State governments’ COVID-19 pandemic response on the nation’s broader arts economy, the same mandates counterintuitively played an integral role in encouraging a boom in Australia’s art market. Overall, the ability to close Australia to the rest of the world resulted in far fewer deaths from COVID-19, compared to other developed countries around the world, particularly in western Europe and the USA, once again reinforcing the nation’s reference to itself as a ‘Lucky Country’ (Horne 1964). However, as this paper will reveal, closer inspection of Australia’s art market reveals a landscape where some art market participants have been ‘luckier’ than others.

2. Literature and Methodology

This paper extends scholarly research on the art market in Australia, building on articles examining the state of the market subsequent to the global financial crisis (Archer and Challis 2019), and the initial impact of the COVID-19 pandemic (Archer and Challis 2020). It explores the local, Australian response to the COVID-19 pandemic from early 2020 to early 2022 and juxtaposes that experience against a global context. This paper builds on scholarly examinations of global art markets through its consideration of the recent history and current status of market development in Australia, and by focussing on two key aspects of global art market development: digitalisation and internationalisation.

In order to situate the Australian experience in a global context, this paper draws on qualitative and quantitative analysis, including parliamentary enquiry documentation, government statistical analysis, art market data, and stakeholder interviews with fifteen art market professionals from across the industry, so as to document industry experiences and identify key emerging themes.1

The notion of a ‘global art market’ is contested. Whilst the convenience of this terminology permits examinations of market mechanisms and institutions that operate across the globe (such as art fairs, biennales, mega-galleries, and multinational auction houses) (Shnayerson 2020; Niemojewski 2021; Gerlis 2021)2, scholars such as Quemin and Graw propose that the notion of a truly global art market is an illusion. Whilst Graw (2009, p. 20) concedes that local art scenes have networked to evolve a global reach, Quemin and Van Hest (2015, p. 180) maintain that the international art world is territorialised with the ‘national context’ being predominant. Belting (2013, p. 184) draws these perspectives together by describing the global art world as ‘polycentric’ and ‘polyphonic’, whilst Smith (2013, p. 186) refers to ‘the multiscalar perspective of worlds-within-the-world’. In this scholarly context, this paper adds a southern-hemisphere, developed-market perspective to a global picture. Moreover, by using primary research, this paper adds qualitative and quantitative data to global art market report analyses, which are predominantly northern-hemisphere, Euro-American focussed. In particular, this paper provides evidence to support Arora and Vermeylen’s (2013, p. 328) observations that digitalisation is driving the market from a supply-side orientation to a consumer-driven market. Overall, through its contextualisation of the Australian art market within, and in juxtaposition to, Australia’s creative arts and financial sectors, this paper concurs with Zarobell’s (2017, p. 8) argument that ‘the arts are not insulated from larger economic processes’.

3. Impact and Policy Response in the Broader Australian Arts Economy

The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in February 2020 found core aspects of the Australian arts economy in an already precarious condition. In part, this was the result of a clear pattern of reduced funding for the arts sector that has emerged at the Federal government level in the last decade (Pacella et al. 2021, Appendix 1 and page 4). Perhaps more damaging has been the decades long drift away from the focused national cultural policies that were developed and implemented in the late twentieth century (Throsby 2001, pp. 548–61). These actions have increasingly been out of kilter with Australia’s international peers, who have taken a more supportive stance in relation to these industries. When compared to the 34 countries in the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), Australia ranks 23 out of 34 in terms of overall government assistance for cultural industries (A New Approach 2022, p. 17). The art market in Australia represents only a small part of the overall arts economy. Demand for fine art has traditionally been strongly focused on domestic art production, and sales volumes have been largely stagnant since the Global Financial Crisis and a number of adverse Federal legislative changes in the early 2010s. Art sales in Australia amount to less than one per cent of global sales, despite Australia’s gross domestic product placing the country in the top fifteen economies in the world (McAndrew 2021, p. 36).

When Federal and State governments responded to the threat of the growing pandemic with restrictions on mobility and crowd sizes in early 2020, the already-vulnerable arts economy was immediately and severely impacted. Professional artists were prevented from earning direct income from commercial art exhibitions and live performances because these were some of the first events to be postponed or cancelled. The closure of all museums, festivals, and other cultural activities quickly compounded losses across arts-related businesses in both the public and private sectors. When the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) started measuring the impact of COVID-19 restrictions on the economy in June 2020, they found that the Arts and Recreation Services sector was second only to the Accommodation and Food Services sector in terms of lost revenue and employment (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2020). As the pandemic and the related restrictions continued throughout 2021, the ABS found that businesses in the Arts and Recreation Services sector were the most likely to report that they were having difficulty meeting their financial commitments (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2020).

The complex nature of employment arrangements in the arts economy also complicated the effectiveness of government stimulus policies enacted during the pandemic (Throsby and Petetskaya 2017). Of the total AUD 4.32 billion of government payments to the sector in the 2019–2020 financial year, 70 per cent, or AUD 3.06 billion, was from the JobKeeper program, a program that reimbursed businesses for retaining furloughed employees (A New Approach 2022, pp. 13–14).3 However, many workers in the arts economy were excluded from the benefits of this program because they were either on short-term contracts, had not worked for their current employer for more than twelve months, or did not meet the definition of ‘sole trader’ (Pacella et al. 2021, pp. 7–9). These workers were forced onto the lower and less-stable JobSeeker payments, a rebadging of the previous unemployment benefit scheme. A total of fifteen additional funding packages worth AUD 1093 million were also directed toward the arts sector by the federal government (Commonwealth of Australia 2021, Appendix E). Unfortunately, these funding initiatives were not always well-designed and directed. Several of the packages were criticised for favouring large arts organisations over individual arts workers, as well as being cumbersome to access and slow to activate (Pacella et al. 2021, pp. 8–12).4 At the time of writing, pandemic-related restrictions have largely been lifted in Australia, but the long-term damage caused to many businesses in the broader arts economy has yet to be properly estimated and documented.

4. Art Market Paradox

As a sub-industry of the broader arts economy, the Australian art market was also impacted by the advent of the COVID-19 pandemic in early 2020. Many commercial art galleries reported a dramatic drop in sales in the first and second quarters of 2020, with several being forced to face the possibility of permanent closure (Interviews 2 and 4). Auction houses were similarly disrupted when major auctions were postponed or cancelled during this period (Interview 9). For these businesses, the JobKeeper initiative and the availability of government-underwritten small-business overdrafts were critical for keeping staff employed and riding out the loss of revenue brought about by the pandemic and related restrictions (Interviews 2, 4, and 9).

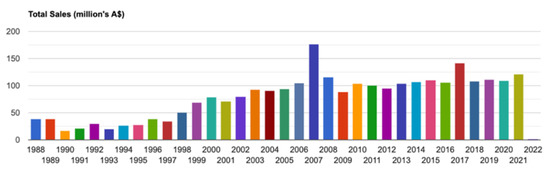

However, in contrast to the broader arts economy, the Australian art market recovered remarkably quickly from the initial economic shock of the pandemic. This can most clearly be seen in the publicly available art auction sales numbers aggregated by John Furphy in the Australian Art Sales Digest database (Figure 1). These records show that, other than 2017, the 2021 year was the most successful year for auction sales volumes in Australia since the previous peak of 2007. The AUD 121 million of sales in 2021 was the third-highest total in the thirty-three years for which records have been kept (Furphy 2022). Even the 2020 year, at AUD 108 million of sales, was remarkably robust given the reduced mobility of art collectors, border closures, restrictions on people gathering, and the postponement or cancellation of several major auctions.

Figure 1.

Annual Australian art auction sales. Source: John Furphy, Australian Art Sales Digest database, accessed on 18 February 2022. https://www-aasd-com-au.eu1.proxy.openathens.net/index.cfm/annual-auction-totals/.

Behind these headline auction sales numbers, three key trends can be identified:

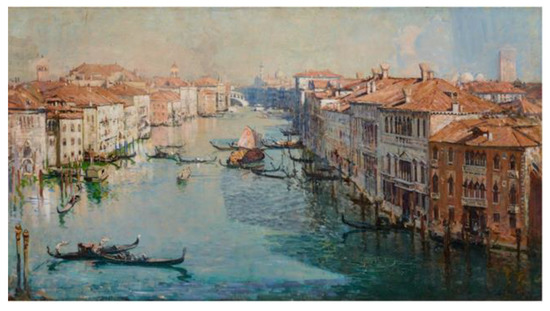

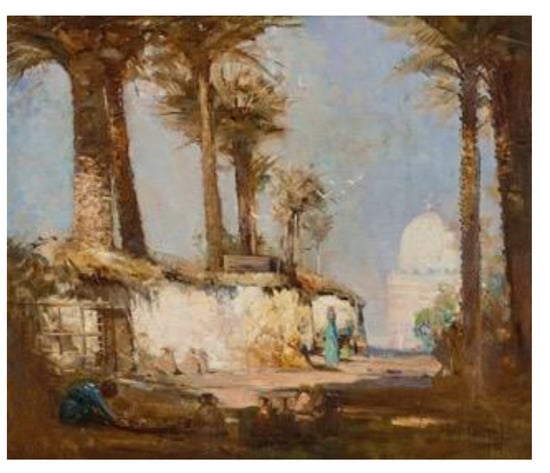

- Art collectors were particularly keen to purchase high-quality paintings by artists that were already well-established in the Australian art canon. Prices paid for well-known Australian Impressionists, such as Arthur Streeton, were significantly higher than in previous years. On 21 April 2021, Deutscher and Hackett set a new record price for a painting by Streeton when they sold The Grand Canal for AUD 3,068,182 (Figure 2) (Furphy 2022). This record was followed seven months later by the sale of the Streeton painting Cairo (Figure 3) by Smith and Singer on 16 November 2021 for AUD 705,682. This was a staggering 380% increase on the previous AUD 146,400 sale price for the same painting only fifteen months earlier, on 27 August 2019 (Furphy 2022);

Figure 2. Arthur Streeton, The Grand Canal, 1908, oil on canvas, 92 × 168.5 cm.

Figure 2. Arthur Streeton, The Grand Canal, 1908, oil on canvas, 92 × 168.5 cm. Figure 3. Arthur Streeton, Cairo, 1897, oil on canvas, 50.6 × 61.3 cm.

Figure 3. Arthur Streeton, Cairo, 1897, oil on canvas, 50.6 × 61.3 cm. - The emergence of substantial demand for female Australian artists. Record prices were paid for the artwork of numerous historical and contemporary female artists, with momentum continuing to build toward the end of the year. Clarice Beckett, Bessie Davidson, and Kathryn Del Barton were just some of the artists that particularly benefited from this shift toward the overdue recognition of female Australian artists (Furphy 2022);

- Finally, artworks by important Indigenous artists continued to draw the attention of international collectors from as far afield as Britain, Switzerland, America, France, and Germany (Interview 9). This recognition has spilled over to domestic collectors with some paintings by female Indigenous artists, such as Sally Gabori, benefiting from more than one of the emerging trends (Furphy 2022).

Trading conditions for commercial art galleries and art fairs appear to have been more mixed over the COVID-19 pandemic period. A wide range of themes and observations on how the COVID-19 pandemic has affected this sector of the art market in Australia became apparent from the interviews conducted with gallery owners and art fair directors. Most established commercial galleries with loyal collectors and a stable of well-known artists experienced an unexpected surge in sales over the 2020–2021 period (Interviews 5, 7, and 10).5 For one gallery, this period represented their best years in the business’s twenty-eight-year history (Interview 10). On the other hand, younger commercial galleries found the pandemic environment extremely difficult and financially challenging (Interviews 5 and 6). This was compounded in some cases by losing artists within their stable to bigger galleries that were able to offer better prospects of making sales (Interview 5). One gallery director went so far as to say that emerging artists, who are often represented by younger galleries, had their careers put on hold in the 2020–2021 period as collectors remained loyal to established artists and galleries (Interview 5).

Galleries with a less-established clientele also suffered from being more reliant on art fairs, which were unable to operate as usual and were instead forced to move their business models online (Interviews 4 and 5). In some cases, this pivot was conducted successfully, with reports of the Darwin Aboriginal Art Fair achieving record sales of AUD 3.12 million in 2021 (Fairley 2021). The Sydney Contemporary Art Fair reported selling double the volume of artwork in 2021 compared to their 2020 online experience (Interview 11). However, a number of gallery owners reported an element of ‘digital fatigue’ as the pandemic wore on and were looking forward to returning to the networking opportunities presented by attending physical art fairs and dealing with collectors in real life (Interview 11). In all cases, commercial galleries reported having to quickly pivot to more nimble business models than they had previously employed. Development of their online capabilities, social media, monthly magazines, alliances with interstate and international galleries, and offering insightful artist-led webinars were all seen as ways to make their business models more robust (Interviews 1, 2, and 10).

One overriding trend was the emergence of increased demand from Australia-based art collectors during the COVID-19 pandemic period. All operators of auction houses, commercial galleries, and art fairs reported an increase in the number of collectors interested in acquiring new artwork, in some cases by as much fifty per cent. In nearly all cases, the rationale for the increased interest was related to the restrictions on mobility. As Australian collectors were forced to postpone or cancel all international travel, the money not spent on airfares, accommodation, and overseas spending swelled their discretionary savings. As more time was being spent in their homes, people naturally turned their minds to improving their built environment. This has fuelled a wave of home renovations, furniture purchases, and a desire to acquire fine art (Interview 10). One gallery owner gave an example of a show for an established Sydney-based artist, where ninety per cent of the paintings offered were quickly sold. More than half of the buyers explicitly stated they were buying artwork in lieu of travelling internationally (Interview 10).

And yet, the depth of buying interest suggests something deeper than simply pecuniary motivations. A number of gallery owners detected a strong sense of willingness to support the local Australian art scene in the face of devastating circumstances for artists and arts-related businesses. By buying domestically produced artworks, collectors were able to express a deeper sense of loyalty to their local communities, and perhaps even a sense of latent nationalism (Interview 7). There were also reports that stay-at-home collectors were finding time to re-engage with cultural interests that had otherwise taken a back-seat to busy work schedules and international travel. For wealthy Australians, the slower pace of the pandemic meant they had more time available to research and purchase artworks they had been inclined to buy but were simply too busy or distracted to act on (Interview 9).

One final factor fuelling the demand for Australian artwork over the COVID-19 pandemic period sits more obviously within traditional art market mechanisms. It was not a simple coincidence that significant exhibitions at major public art institutions preceded the recent art market demand for artists such Arthur Streeton, Clarice Beckett, Bessie Davidson, and Sally Gabori.6 The added status bestowed on an artist through the celebration of their work in public art institutions has always translated to increased symbolic value and cultural capital. From that point, it is only a short step to increased economic values, as collectors compete to own artworks that have been canonised by institutions, curators, and art historians. One art market professional described how the Arthur Streeton exhibition at the Art Gallery of New South Wales in late 2020 and early 2021 had the effect of not only reminding older collectors of the outstanding quality of his work, but also introduced many younger collectors to his important place in the history of Australian art (Interview 9).

5. Australian Art Market in a Global Context

When thinking about the strong performance of the Australian art market over the COVID-19 pandemic period, it is important to properly contextualise this performance in relation to the global art market. According to the Art Market Report 2021 prepared by Clare McAndrew, the global art market suffered a significant decline from early 2020 to early 2021. Global sales of fine art and antiques were valued at USD 50,065 million in 2020, which represented a 22 per cent decline since 2019 and a 27 per cent decline since 2018 (McAndrew 2021, pp. 30–31). The Australian art market does not produce an equivalent total sales number to that used in Clare McAndrew’s report; however, the annual auction sales values given above and the anecdotal feedback from the commercial gallery sector clearly show that the Australian art market’s experience of the COVID-19 pandemic was one of growth rather than decline.

A significantly different story emerges when the respective numbers are considered in the context of the last decade. At the lowest point of the recession induced by the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) in 2009, the global art market recorded USD 39,511 million of sales. Between 2009 and 2018, global sales increased to USD 67,653 million, equating to a 71 per cent increase (McAndrew 2021, p. 31). The equivalent increase in the sales values recorded in the Australian auction market was a far more tepid 21 per cent increase, with total auction sales increasing from USD 88 million in 2009 to USD 107 million in 2018 (Furphy 2022). As can be seen in Figure 1, auction sales numbers in Australia have essentially been stuck in the AUD 100 million region since the end of the GFC. In light of this comparison, the COVID-19 pandemic period of increased sales in the Australian art market is more correctly seen as catching up to growth already seen in the global market, rather than a period of isolated outperformance.

Understanding this anomaly in the performance of the Australian art market versus the global art market requires a deeper dive into a number of structural differences between the two markets. The global art market was immediately buoyed in the aftermath of the GFC by booming sales in the newly emergent Chinese market and a rapid rebound of sales in the United States (McAndrew 2021, pp. 31–33). This sales growth was underpinned by rapidly rising prices for marque artists, particularly in the Post-War and Contemporary market sector (McAndrew 2021, pp. 132–42). The decline in global sales over the last two years is in large part explained by the inability to sell these types of artworks in the optimal manner during the pandemic period. Collectors were reluctant to consign major artworks for sale without the lavish exhibitions and in-person auctions that are likely to optimise their value, but that were made impossible by the pandemic-related restrictions (Interview 9). The Australian art market does not share in this geographic diversification or in the predominance of big-ticket sales for star artists. Instead, the Australian art market was muted by a number of structural changes that occurred shortly after the GFC recession subsided.

In 2009, the Resale Royalty Right for Visual Artists Act 2009 was passed in the Federal parliament. This act required a royalty payment of 5 per cent of the sale price to be paid to the originating artist or their estate for all secondary sales of artwork valued at more than AUD 1000 (Commonwealth of Australia 2009). This legislation immediately introduced a one-off price increase to all art sold in the secondary market in Australia and has been blamed by some commentators for a lull in collecting activity at that time (Fairley 2020a).

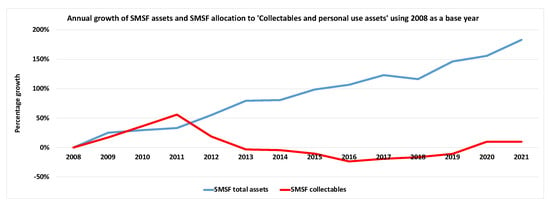

Probably of greater significance to the overall art market in Australia were the 2011 amendments made to the Superannuation Industry (Supervision) Act 1993 (SIS act). In summary, these amendments disincentivised self-managed super funds (SMSFs) from owning collectables and personal-use assets (such as artworks) by prohibiting fund owners from storing and displaying such assets in their personal residence (Challis 2020).7 Using data recorded by the Australian Tax Office, it is very straightforward to see the impact these changes have had in the last decade (Figure 4). While SMSF balances have experienced a 112 per cent growth between 2011 and 2021, the value of collectables and personal-use assets owned by SMSFs has decreased by 30 per cent in the same period (Australian Tax Office 2021). This represents a rapid decline in the pro rata allocation of SMSF assets to the collectables and personal use asset class amounting to a loss of AUD 848 million of investible funds over the last ten years. For the Australian art market, this represented an unfortunate and unnecessary loss of a large portion of the local demand for fine art. A strong argument can even be made that fine artwork should not have been included in the 2011 amendments to the SIS act in the first place. Looking at a painting does not diminish its value in the same way that drinking a bottle of vintage wine does. This non-rivalrous aspect of fine art’s intrinsic nature makes it a far more suitable SMSF investment than other collectable assets (Challis 2020, pp. 7–9).

Figure 4.

Annual growth of SMSF assets and SMSF allocation to ‘Collectables and personal use assets’. Source: Author, using data from the Australian Taxation Office. https://www.ato.gov.au/About-ATO/Research-and-statistics/In-detail/Super-statistics/SMSF/Self-managed-super-fund-quarterly-statistical-report---September-2021/ (accessed on 18 February 2022).

Much of the difference in the performance of the Australian art market relative to the global art market in the 2009 to 2018 period can be explained by these two legislative changes. However, to a large extent, these factors have now been overtaken by the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on stay-at-home art collectors and the emergence of other important themes, such as the digital pivot, which has irrevocably changed the landscape of the art market in Australia.

6. The Digital Pivot

The digital pivot driven by COVID-19 lockdowns has been a significant factor in the recalibration of the global art market. In contrast to the stuttering performance of the overall global market, online art sales trebled in the first eighteen months of the pandemic compared to 2019 totals (Hiscox & Art Tactic 2021, p. 1). Globally, both the primary and secondary markets had been digitising their operations since the turn of the millennium, with digital images and PDFs being standard mechanisms for illustrating artworks and generating catalogues and price lists (Israel 2021, p. 226). In the decade prior to the pandemic, the digitalisation of art market systems increased through the formats of online auctions for brick-and-mortar auction houses and online viewing rooms (OVRs) for commercial galleries.8

The impact of the pandemic-driven digital turn was amplified in the Australian art market due to a rapid shift in consumer behaviour more broadly. Prior to the pandemic, Australians were already considered to be laggards in their participation in online shopping compared to their peers in Europe and the USA. However, the extensive limitation on the mobility of the population through lockdowns, which were both widespread and localised, forced consumers to turn to online options (Fairley 2020b). This meant that art market growth via digital technology was exacerbated in Australia, as collectors rapidly adapted to and adopted this new mode of engagement (Child et al. 2020). Although there is no specific data, all of the interviewees reported the paramount importance of technology during the pandemic to sustain, and then in many cases to grow, their businesses.

The success of the digital pivot for Australian commercial galleries has aligned closely to the prior digital competence of the gallery, as well as the financial and human resources to exploit the multiple digital opportunities. Only a very few of the galleries had interacted with OVRs prior to the pandemic, and this had predominantly been facilitated by international art fair activity. Many turned to third-party software to create online viewing room experiences that replicated the in-room appearance of exhibitions. Indeed, many gallery interviewees noted the importance of the ‘phygital’, the real or virtual appearance of a physical art-viewing experience (Interviews 1, 2, 7, 10, and 12). One gallerist noted the important intersection of the virtual gallery presence on their website and the physical opportunity of exhibiting in their shop window, where collectors could view the actual artworks within their lockdown-designated travel boundary (Interview 10). Another gallerist noted their use of government pandemic funding to invest in equipment (such as high-resolution video cameras) to improve the quality of the digital presence (Interview 7). Overall, the majority of galleries who had a successful experience with their online exhibitions have confirmed that these will be an ongoing feature of their gallery presentations post-pandemic.

Social media was also cited as an important element of digital success for galleries. This was across multiple platforms, although Instagram was credited most highly as being a successful tool to attract the attention of collectors. Several galleries suggested that social media generated by their represented artists was also an important aspect of collector awareness and generating sales traffic to the gallery (Interviews 1, 2, 4, and 7). Additionally, many galleries suggested the need to do more than simply present artworks in a digital format to their captive audiences (Interviews 1, 2, 4, and 7): online content needed to be dynamic and contextual. Again, the intersection with the physical was highlighted, such as a gallery that innovated an online magazine and printed a short run of glossy hard copies to be delivered exclusively to their VIP clients (Interview 2).

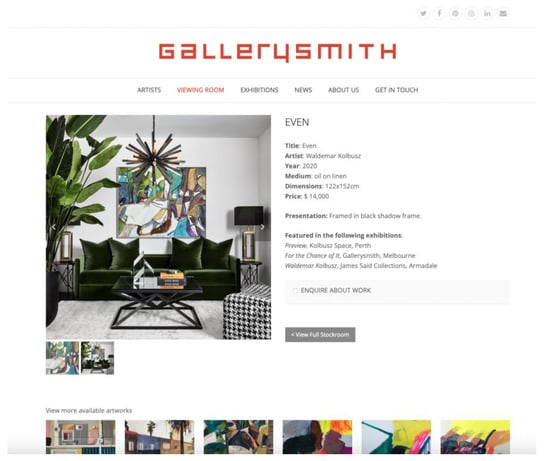

The most transformative element of the digitalisation of the Australian commercial gallery sector has been the publication of prices. In the words of one gallerist, this has been ‘a game changer’ (Interview 2). Prior to the pandemic, the publication of prices either online or in the gallery was minimal, as gallerists believed that it was important to talk directly to collectors in order to determine their level of interest and drive a sale. By contrast, the publication of prices in the OVRs encouraged a higher level of engagement by collectors more broadly, and generally resulted in more enquiries leading to actual sales (Interview 2). Many galleries proposed that they will continue this practice in the future, thereby demonstrating a significant systemic shift in Australian commercial gallery operations as a result of the pandemic (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Gallerysmith, Melbourne. Online viewing room embedded in website. Image courtesy of Gallerysmith.

It is important to note that some Australian galleries did not find success with their digital interactions. However, closer inspection reveals that this often aligned with the overall structure of the gallery business. For example, one gallerist whose business model is entirely based on the pop-up exhibition model found that the OVR format did not replicate the collector excitement driven by the ‘pop-up’, and perhaps this suggests the importance of the physicality of exhibiting space and artwork for collector confidence (Interview 5). Similarly, those gallerists who had limited human capital or were newer to the marketplace struggled to generate sufficient digital engagement with collectors to make a meaningful impact on their businesses during this time. For some newer galleries, this resulted in their closure entirely (Interview 8). Overall, the best outcomes for galleries and artists were where the collectors had an established relationship, and the digital environment became the transactional facilitator.

Australian art auction houses experienced a boom during the COVID-19 pandemic, as did many auction houses globally (Boland 2021). Most of the houses attributed this to digital engagement. Predominantly, the fine art auction houses in Australia had begun to experiment with online auctions at the lowest value end of the market in the early 2010s. Consequently, they all either had the technology, or had access to it via an intermediary platform (particularly Invaluable, which is by far the most commonly used online auction platform in Australia).9 As one auction house specialist proposed, the auction houses were ahead of the curve on the technological front and they were waiting for collectors to catch up (Interview 3). This is a little disingenuous: whilst the auction houses were technologically prepared and were, thus, waiting for Australian collectors to feel more comfortable using the technology, the online offerings by Australian auction houses were usually of lower value and quality, thereby restricting this option to a specific collector demographic.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, auction houses were permitted to continue operating but without audiences. Consequently, all collectors had to engage with auction houses digitally, and the ‘stigma’ of online auctions, in terms of quality and value, was removed (Interview 3). Thus, the growth in business for auction houses was across the board: increased buyer registration as more collectors embraced the concept of online shopping; increased volume of lots once vendors realised the growing number of potential buyers; increased value of lots as the stigma of online activity diminished; and increased sales results as multiple bidders competed over each lot (Boland 2021; Coslovich 2021).

Like the commercial galleries, the auction houses also emphasised the importance of the ‘phygital’. Some were able to offer viewings by appointment, and most of the major auctions were not entirely online but were conducted through livestreaming an auctioneer in the auction room taking bids from online platforms and telephones. Indeed, a completely novel format arose from the benefit of a captive audience with digital capabilities: the single-lot auction, often badged as a ‘masterpiece’ opportunity.10

Moving forward, all of the Australian auction houses believe that the online aspect of their businesses will continue to grow; however, most also suggested that ‘some auctions’ need to remain being held in the room as collectors are motivated by the theatrical experience and sense of community engendered by a live sale (Interviews 3, 9, and 12).

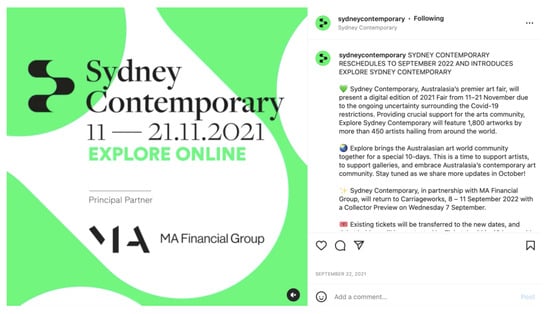

The element of the Australian art market that has been most impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic has been the art fair. The Australian art fair landscape was already problematic prior to the pandemic, and the strict lockdowns and interstate border closures resulted in the two main fairs—Melbourne Art Fair and Sydney Contemporary—having to close their physical iterations for two years (Figure 6). Melbourne Art Fair (MAF), a biennial event dating back to 1988, was struggling before the pandemic due to the arrival of a strong competitor, Sydney Contemporary, and its complicated governance structure run by a not-for-profit foundation (Wilson-Anastasios 2016). Scheduled to run in mid-2020, MAF aligned itself with the online platform Ocula to run its 2020 iteration. It then abandoned a 2021 offering, preferring to wait for the opportunity to run a live event. The annual Sydney Contemporary, on the other hand, opted for the OVR format in both years of the pandemic and developed their own software programme (Interview 11). Response to the success of Sydney Contemporary from commercial galleries was mixed, and again this appeared to align with the overall digital success of each commercial gallery, with art fair participation forming one element of a broader digital sales strategy (Interviews 1, 2, 4, and 11).

Figure 6.

Sydney Contemporary Instagram post, announcing rescheduling of physical edition to 2022, and launch of 2021 digital edition, 22 September 2021. Image courtesy of Sydney Contemporary.

Overall, both the primary and secondary Australian art market sectors noted particular shifts in digital engagement across the duration of the COVID-19 pandemic, usually in alignment with the rhythm of lockdowns and openings. Digital engagement has been particularly important to overcome the tyranny of distance in a large country and the multitude of changing interstate border rules across the years of the pandemic. Chronologically, it appears that 2020 represented a rush to digital engagement by previously reticent Australian consumers, alongside a digitally native younger generation who embraced digital mediums to become engaged with art for the first time. The year 2021 demonstrated a consolidation of online trading as the ‘new normal’, whilst requiring more effort on behalf of art market operators to keep collectors interested and engaged. Reports in early 2022 have suggested a level of digital fatigue; however, the shift of governments and the community from a pandemic mode to an endemic approach has meant that in-person activities can now resume in Australia, which should inject renewed vigour in a sector that thrives on sociability and mobility.

Perhaps the most notable difference between the Australian and the global art markets in relation to digitalisation during the COVID-19 pandemic is the absence of interest to date in non-fungible tokens (NFTs). One might claim that the notorious sale by Christie’s auction house of Beeple’s digital artwork Everydays—The First 5000 Days as an NFT on 11 March 2021 for USD 69.34 million represents a watermark in global art market history (Reyburn 2021). It signified the moment of intersection of digital art as a genre, cryptocurrency as an investment boom, and the activities of auction houses as primary market operators.

In Australia, to date, there has been only very isolated engagement by either artists or the art market with this aspect of digital technology in a commercial sense (Bueti 2021). That being said, the Australian visual art sector has a strong presence in the global history of digital art and its exhibition.11 Furthermore, the Federal government arts funding body, Australia Council, has recognised the importance of this sector in its report In Real Life—Mapping digital cultural engagement in the first decades of the 21st Century, published in July 2021, and has pledged to increase funding and support for innovation and experimentation in this field in the future (Australia Council for the Arts 2021a). These developments would therefore suggest that whilst Australia lags in this sector at the moment, there will be greater expansion in the near future.

A potential extension of this phenomenon is the growth of the ‘informal economy’ of artists transacting works directly to collectors. The disintermediated marketplace afforded by digital platforms offers economic opportunities to artists to bypass traditional financial structures of the ‘formal’ art market. Whilst it is currently difficult to quantify and measure the value of this activity, there can be no doubt that the ‘digital pivot’ presents systemic change to both global and local markets and warrants further research.

Overall, it appears that the Australian art market has benefitted greatly from the digital pivot driven by the COVID-19 pandemic. With initial support from government funding, both the primary and secondary markets have been propelled into the digitalisation of their systems and have consequently experienced economic growth through expanded digital engagement. Moving forward, it appears that a ‘phygital’ approach—blending physical and digital aspects of their businesses—will continue to strengthen the operations of Australian auction houses, galleries, and art fairs into the future.

7. Domestic vs. International

The closure of Australia’s international borders on 20 March 2020 demonstrated the advantage of being an island that is relatively isolated from adjacent continents. In comparison to other nations, the rapid lockdown of the country protected the Australian population from widespread coronavirus infection (Haseltine 2021). International border closures also prevented Australian citizens from leaving the country without special government permission for two years (Jefferies and McAdam 2021). The impact on the Australian art market was swift and deep, as Australians rapidly became inward-facing.

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, Australia’s art market was predominantly domestically focussed, notwithstanding a strong historical connection between Australia and New Zealand. However, primary market operators have endeavoured to increase the country’s international engagement over the past two decades. Australia has had a presence at the prestigious Venice Biennale since 1954, with its first Giardini della Biennale pavilion created in 1988, and a new structure completed in 2015. This event has long featured as a focus of the Australia Council’s international strategy for the visual arts sector (Gardner 2021). The primary market has shifted in recent years to engage regionally with Asia, particularly through initiatives led by government-funded institutions, including the Department for Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT), Asialink, and the Australia Council. According to their International Arts Strategy 2015–2020 Impact Report, the Australia Council increased its investment in Asia to 25% of its total investment in international engagement (Australia Council for the Arts 2021b, p. 12). International art fairs have played an important role in exposing Australian artists, galleries, and collectors to a broader market, with Art Basel Hong Kong, KIAF, and Art Stage Singapore being of particular relevance and interest (Fairley 2015).12 Simultaneously, a small number of international artists have been represented by Australian commercial galleries, whilst a few international galleries have participated in the local art fairs, although very few on a prolonged basis. More recently, the high costs and high risk of featuring in international art fairs has become a burden for some Australian galleries, and participation had begun to wane prior to the COVID-19 pandemic and the border closures (Interview 5).

The domestic nature of the secondary market has grown even deeper over the last two decades subsequent to the withdrawal of both Christie’s and Sotheby’s auction houses from the Australian market in 2006 and 2009, respectively.13 The second-tier, British-based auction house Bonhams has moved in and out of the Australian market over several decades and is currently present in both Sydney and Melbourne. However, the company’s focus has rarely been on the domestic market. Instead, Bonhams’ strategy in Australia is to target arbitrage opportunities for moving material in and out of the country via its global network of offices to locales best suited to produce the optimum sale result (Interview 12). All of the other major Australian fine art auction houses are locally owned and cater predominantly to a local audience with local content. A recent trend has been the presentation of international modern and contemporary art at auction in Australia, such as the work of Fernando Botero and Henry Moore, coming out of older Australian collections (Interview 9). These works have driven European collector interest through online auction platforms with collectors seeking bargains in remote markets.

The predominant consequence of the closed international border has been to focus the attention of Australian collectors on Australian galleries and artists (Price 2020). Almost all of the gallerists interviewed proposed that this was a major factor in their financial success during the pandemic. For those galleries who normally participated in the international art fair circuit, the restriction in mobility was cited as a positive impact through giving staff and artists a break from the pressures of travelling (Interviews 2, 4, and 7). Any loss of engagement through lack of physical participation in the fairs has been balanced by digital communications, as well as an increase in support from local collectors. Whilst several galleries appreciated the opportunity to focus on the domestic market, others expressed concern about the possibility of a ‘further disconnection’ of Australia’s art market from the international community (Interview 6). In particular, several interviewees cited that Australian artists wanted their galleries to be more internationally involved (Interviews 1, 2, and 7).

Indeed, internationalisation is an important consideration for the Australian art market. The market is relatively small (in line with Australia’s small population of just under 26 million people in 2020) and international development will be essential for the market to grow (Interview 11). A key area for potential growth and success in the international arena is Australian Indigenous art (Archer 2020, pp. 9–14). The market for this genre of art has been developing since the 1980s, with waves of popularity domestically and internationally, particularly through genre-specific galleries and auctions (Coslovich 2020b). Its market has distinct characteristics and a separate infrastructure that has been investigated by scholars in depth, most recently by Chow (2021), Akbar and Sharp (2020), Archer (2020), Myers (2020), and Fry (2020). After a lull for the last decade, Australian Indigenous art was experiencing a boom of international interest prior to the pandemic, driven by the exhibition of artworks by leading Indigenous artists at the mega-gallery Gagosian in New York. With subsequent iterations planned for Gagosian Hong Kong and Gagosian Paris, the pandemic lockdowns forced the down-scaling and rescheduling of these exhibitions (Coslovich 2020a). The impact of these exhibitions remains to be seen. In the meantime, the domestic market for Indigenous art has grown rapidly, with many of Australia’s contemporary galleries incorporating First Nations artists into their stables.

Perhaps the biggest challenge for the internationalisation of Australian contemporary art, including Indigenous art, is the comparative value of artworks. Dealers in Indigenous art report that their international collectors consider this genre to be very low-priced, compared to international contemporary art. Indeed, when a major American collection of Australian Indigenous art was sold by private treaty in December 2020, Henry F. Skerrit (curator of the Indigenous Arts of Australia at the University of Virginia) noted that “You can’t buy a decent American modernist painting for $10 million so the idea that you can pick the 250 best works from the largest collection of Indigenous art for $10 million, that seems like a bargain” (Coslovich 2020b). One gallerist specialising in Indigenous art said that international collectors often associated value with price, and they questioned the merit of Australian Indigenous art because ‘it was too cheap’ (Interview 13). This is a vital consideration for the Australian market that merits further research. How can this inequity in pricing be resolved? Can Australian commercial galleries successfully recalibrate prices to be equitable to international levels, or might artists be forced to relocate to representation overseas in order to take advantage of international collector interest?

Another concern for Australian contemporary galleries on a global front is the shifting art fair landscape that has occurred during the pandemic (Interview 2). As some fairs have consolidated, others have disappeared, and some are impacted by changing geo-political issues. This is particularly relevant in a regional context, especially in the hubs of Hong Kong and Singapore. Australian gallerists are uncertain about the strategy of committing to these international events, particularly whilst the domestic market remains strong and reliable (Interviews 2, 4, and 7). Conversely, international galleries remain reluctant to participate in the Australian market due to hesitancy around long-term planning (Interview 11).

In summary, there is a general recognition within the Australian art market that internationalisation is both desirable and important to expand the current ecosystem. Whilst the secondary market in Australia has always been strongly domestic, the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated a developing trend of domestic focus for the primary market as well. Digital interactions are currently maintaining international connections, engagement, and sales. However, whilst the domestic market remains buoyant and reliable, it is unlikely that there will be a rush to drive international expansion once the borders are reopened. That being said, the systemic pivot to digitalisation in Australia may be the key mechanism that facilitates this growth (such as international collectors engaging with Indigenous art by bidding online). Overall, it does appear that, once again, Australia is a ‘Lucky Country’. Its art market has benefitted from its experience of the COVID-19 pandemic: through short-term domestic growth as the country has become more inward looking, but with much greater international opportunity in the future through its expanded digital capacity and competence.

8. Conclusions

Australia greatly benefited from being an island continent in its efforts to contain and eliminate the COVID-19 pandemic. This geographic advantage, combined with severe government restrictions on public mobility and gatherings, resulted in significantly fewer deaths and hospitalisations in Australia than in many other countries. But these same factors also produced a complex and contradictory business landscape for the Australian art market during the COVID-19 pandemic period. On the one hand, stay-at-home collectors became a major force in the Australian art market and contributed to a robust sales performance that contradicted the significant contraction experienced in the broader arts economy. This was in many ways facilitated by an overdue digital pivot in Australia that allowed auction houses, commercial galleries, and even art fairs to not only stay in touch with the growing body of art collectors, but also more easily monetise their demand for high-quality Australian artworks. On the other hand, Australia’s geographic isolation and a renewed sense of needing to support the local arts industry intensified the already introspective nature of Australia’s art market. Ambitions to expand the market for Australian art to international art collectors were necessarily put on hold as restrictions on the physical mobility of people and goods became too onerous. Overall, this paper has revealed a systemic shift in the Australian art market driven by the COVID-19 pandemic—from an investment-driven boom pre-GFC, to a decade of stagnation, to revitalised growth driven by stay-at-home collectors and increased digital engagement. The extent of this digital pivot perhaps offers new hope for breaking down the tyranny of distance and parochialism that has, to date, limited the marketability of Australian art outside its domestic borders, and thereby might facilitate for this ‘Lucky Country’ a deeper and enduring intersection with the global art market.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.A. and D.M.C.; Formal analysis, A.A.; Investigation, A.A. and D.M.C.; Methodology, A.A. and D.M.C.; Project administration, A.A.; Writing—original draft, A.A. and D.M.C.; Writing—review & editing, A.A. and D.M.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Interviewees comprised nine gallerists, three auction specialists, two art fair directors, and an art financier. All interviews were confidential; the names of the interviewees are withheld by mutual agreement. The interviews were conducted in person and by phone with the authors in February 2022: Interview 1 with gallerist, 2 February; Interview 2 with gallerist, 2 February; Interview 3 with auction house specialist, 2 February; Interview 4 with gallerist, 3 February; Interview 5 with gallerist, 4 February; Interview 6 with gallerist, 4 February; Interview 7 with gallerist, 3 February; Interview 8 with art financer, 7 February; Interview 9 with auction house specialist, 7 February; Interview 10 with gallerist, 9 February; Interview 11 with art fair director, 9 February; Interview 12 with auction house specialist, 10 February; Interview 13 with gallerist, 11 February; Interview 14 with art fair director, 17 February; and, Interview 15 with gallerist, 18 February. The artists’ perspectives, particularly by NAVA (National Association for the Visual Arts) and the Australia Council for the Arts, can be found on their websites. This is the first analysis to date that specifically focuses on the experience and perspective of Australia’s art market professionals. It thereby focuses on the ‘formal economy’ for art in Australia. The authors recognise the significance of the ‘informal economy’ both globally and locally (Zarobell 2017, pp. 243–53) and propose that this is an area that is beyond the parameters of this article but is significant for further research and analysis. |

| 2 | Adding to earlier scholarship on these elements of the art market, multiple recent publications, including many written by art market insiders, focus on these specific areas. |

| 3 | A full discussion of the JobKeeper and JobSeeker programs is given in Ben Phillips, Matthew Gray, and Nicholas Biddle, COVID-19 JobKeeper and JobSeeker impacts on poverty and housing stress under current and alternative economic and policy scenarios, Australian National University, August 2020. |

| 4 | The headline dollar value of other packages, such as the RISE Fund, were also inflated to some extent by concessional loan facilities that were always intended to be repaid, as opposed to acting as outright stimulus payments. In many cases, State governments were required to provide additional funding to support arts workers left in precarious economic circumstances. The headline dollar value of other packages, such as the RISE Fund, were also inflated to some extent by concessional loan facilities that were always intended to be repaid as opposed to acting as outright stimulus payments. |

| 5 | Note that Interview 4 indicates that this was not entirely the case for established galleries. This gallery had two-thirds of their planned exhibitions cancelled in 2020. |

| 6 | Art Gallery of New South Wales, Streeton, 7 November 2020–14 February 2021, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Clarice Beckett: The Present Moment, 27 February 2021–23 May 2021, National Gallery of Australia, Know my Name: Australian Women Artists 1900 to Now, 14 November 2020–9 May 2021. |

| 7 | The intention behind these amendments was to ensure SMSF investments were made for the sole purpose of building fund balances, as opposed to any current-day benefit for the fund trustees. Investments in collectables and personal-use assets were seen as potentially contrary to this purpose. There was also a sense that art investments were too speculative and not suitable for SMSF investment strategies, although other risky asset classes, such as speculative stocks, currencies, or venture capital investments, did not attract the same attention. Specifically, the amendments prohibited SMSFs from leasing collectables and personal-use assets to a related party; prohibited such items from being stored in the private residence of a related party; required decisions relating to the storage of such items to be documented; required such items to be insured under the SMSF’s name; prohibited such items from being used by a related party, and required any transfers of such items to a related party to be independently valued. |

| 8 | The concept of online viewing rooms dates back to 2007, with formats offered by Art Logic and the David Zwirner Gallery. Refer to Matthew Israel, The Rise of the OVR. |

| 9 | The Boston-based online auction platform company Invaluable is used by all the major art auction houses in Australia, including Bonhams (to a limited extent), Deutscher and Hackett, Lawsons, Leonard Joel, Menzies Brands, Shapiro, and Smith & Singer. |

| 10 | Initiated by Smith & Singer Auction House with the offering of Cressida Campbell Night Interior on 5 May 2020, this format was followed shortly thereafter by Deutscher and Hackett offering Del Kathryn Barton’s Hugo on 3 June 2020. Several ‘masterpiece’ solo artwork auctions have taken place throughout the pandemic period. |

| 11 | ‘Scanlines’ is an online resource collating information about new media art in Australia since the 1960s. http://scanlines.net (accessed on 25 January 2022). |

| 12 | In 2015, eight Australian galleries participated in the prestigious Art Basel Hong Kong. |

| 13 | In 2009, Sotheby’s International withdrew from Australia, and sold a 10-year license to operate under its name to two local operators, former curator Geoffrey Smith and former city mayor Gary Singer. In 2020, the license was not renewed. |

References

- A New Approach. 2022. Public Expenditure on Artistic, Cultural and Creative activity in Australia in 2007–2008 to 2019–2020. Canberra: OECD National Accounts Statistics, Available online: https://data.oecd.org/chart/6wsj (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- Akbar, Skye, and Anne Sharp. 2020. Strengths and Challenges of Aboriginal Art Centre Marketing. Australian Aboriginal Studies 1: 66–83. [Google Scholar]

- Archer, Anita, and David Challis. 2019. Friday Essay: The Australian art market has flatlined. What can be done to revive it? The Conversation. September 27. Available online: https://theconversation.com/friday-essay-the-australian-art-market-has-flatlined-what-can-be-done-to-revive-it-122932 (accessed on 24 January 2022).

- Archer, Anita, and David Challis. 2020. Travel bans and event cancellations: How the market is suffering from coronavirus. The Conversation. March 11. Available online: https://theconversation.com/travel-bans-and-event-cancellations-how-the-art-market-is-suffering-from-coronavirus-133161 (accessed on 24 January 2022).

- Archer, Anita. 2020. Materialising Markets: The Agency of Auctions in Emergent Art Genres in the Global South. Arts 9: 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, Payal, and Filip Vermeylen. 2013. Art Markets. In Handbook on the Digital Creative Economy. Edited by Ruth Towse and Christian Handke. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar. [Google Scholar]

- Australia Council for the Arts. 2021a. In Real Life—Mapping Digital Cultural Engagement in the First Decades of the 21st Century; Canberra: Australia Council for the Arts, Released July 2021.

- Australia Council for the Arts. 2021b. International Arts Strategy 2015–2020 Impact Report; Canberra: Australia Council for the Arts, Released September 2021.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2020. Business Indicators, Business Impacts of COVID-19; December 2020 and June 2021. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/economy/business-indicators/business-conditions-and-sentiments/jun-2020; https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/economy/business-indicators/business-conditions-and-sentiments/dec-2020; https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/economy/business-indicators/business-conditions-and-sentiments/jun-2021. (accessed on 10 March 2022).

- Australian Tax Office. 2021. Self-managed super fund quarterly statistical report—September 2021. Available online: https://www.ato.gov.au/About-ATO/Research-and-statistics/In-detail/Super-statistics/SMSF/Self-managed-super-fund-quarterly-statistical-report---September-2021/ (accessed on 20 February 2022).

- Belting, Hans. 2013. From World Art to Global Art: View on a New Panorama. In The Global Contemporary and the Rise of New Art Worlds. Edited by Andrea Buddensieg, Hans Belting and Peter Weibel. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Boland, Michaela. 2021. Business is booming as barriers fall away for cashed up art lovers. Sydney Morning Herald. June 20. Available online: https://www.smh.com.au/culture/art-and-design/business-is-booming-as-barriers-fall-away-for-cashed-up-art-lovers-20210618-p58276.html (accessed on 10 March 2022).

- Bueti, Giselle. 2021. Australian art world buys into NFTs. Artshub. June 2. Available online: https://www.artshub.com.au/news/news/australian-art-world-buys-into-nfts-262714-2371178/ (accessed on 1 February 2022).

- Challis, David M. 2020. Policy, Precarity and Stimulus in the Visual Arts Economy. In NGV Triennial 2020. Melbourne: National Gallery of Victoria. [Google Scholar]

- Child, Jenny, Rod Farmer, Thomas Rudiger Smith, and Joseph Tesvic. 2020. As physical doors close, new digital doors open. McKinsey & Co. May 21. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/retail/our-insights/as-physical-doors-close-new-digital-doors-swing-open (accessed on 2 February 2022).

- Chow, Ai Ming. 2021. Reimagining the Indigenous Art Market: Site of Decolonisation and Reassertion of Indigenous Cultures. Ph.D. thesis, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Commonwealth of Australia. 2009. Resale Royalty Right for Visual Artists Act 2009. Available online: https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/C2009A00125#:~:text=Resale%20royalty%20is%20payable%20at,commercial%20resale%20of%20an%20artwork.&text=Resale%20royalty%20on%20the%20commercial,to%20pay%20the%20resale%20royalty (accessed on 10 March 2022).

- Commonwealth of Australia. 2021. Inquiry into Australia’s creative and cultural industries and institutions. In Sculpting a National Cultural Plan: Igniting a Post-COVID Economy for the Arts. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Coslovich, Gabriella. 2020a. Gagosian opens $5m Indigenous art exhibition in HK. Australian Financial Review. September 30. Available online: https://www.afr.com/life-and-luxury/arts-and-culture/gagosian-opens-5m-indigenous-art-exhibition-in-hk-20200929-p560ef (accessed on 20 February 2022).

- Coslovich, Gabriella. 2020b. Indigenous art is rising and this time it’s part of a global trend. Australian Financial Review. December 29. Available online: https://www.afr.com/life-and-luxury/arts-and-culture/indigenous-art-is-rising-and-this-time-it-s-part-of-a-global-trend-20201220-p56p2a (accessed on 5 February 2022).

- Coslovich, Gabriella. 2021. ‘There is enormous appetite’: Art market revels as more records fall. Australian Financial Review. April 28. Available online: https://www.afr.com/life-and-luxury/arts-and-culture/there-is-enormous-appetite-art-market-revels-as-more-records-fall-20210428-p57n1o (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- Fairley, Gina. 2015. Australian galleries killing it at Art Basel HK. Artshub. March 15. Available online: https://www.artshub.com.au/news/news/australian-galleries-killing-it-at-art-basel-hk-247423-2347643/ (accessed on 2 March 2022).

- Fairley, Gina. 2020a. Review of Resale Royalty Scheme Outdated and Opaque. Artshub. January 3. Available online: https://www.artshub.com.au/news/opinions-analysis/review-of-resale-royalty-scheme-outdated-and-opaque-259498-2365796/ (accessed on 18 February 2022).

- Fairley, Gina. 2020b. Isolation is changing the face of arts e-commerce. Artshub. May 5. Available online: https://www.artshub.com.au/news/features/isolation-is-changing-the-face-of-arts-e-commerce-260306-2367229/ (accessed on 24 January 2022).

- Fairley, Gina. 2021. The Big List—the visual arts in 2021. Artshub. December 17. Available online: https://www.artshub.com.au/news/aggregations/the-big-list-the-visual-arts-in-2021-2520441/ (accessed on 18 February 2022).

- Fry, Tim R. L. 2020. Heterogeneity in Auction Price Distributions for Australian Indigenous Artists. Economic Record 96: 177–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furphy, John. 2022. Australian Art Sales Digest Database. Available online: https://www-aasd-com-au.eu1.proxy.openathens.net/index.cfm/annual-auction-totals/ (accessed on 18 February 2022).

- Gardner, Kerry. 2021. Australia at the Venice Biennale. Melbourne: The Miegunyah Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gerlis, Melanie. 2021. The Art Fair Story: A Rollercoaster Ride. London: Lund Humphries. [Google Scholar]

- Graw, Isabelle. 2009. High Price. Art between the Market and Celebrity Culture. Cologne: Sternberg Press. [Google Scholar]

- Haseltine, William A. 2021. What can we learn from Australia’s COVID-19 response? Forbes. March 24. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/williamhaseltine/2021/03/24/what-can-we-learn-from-australias-covid-19-response/?sh=1756c0c93a01 (accessed on 1 February 2022).

- Hiscox & Art Tactic. 2021. Hiscox Online Art Trade Report 2021. York: Hiscox & Art Tactic, Available online: https://www.hiscox.co.uk/online-art-trade-report (accessed on 1 February 2022).

- Horne, Donald. 1964. The Lucky Country. Melbourne: Penguin Books. [Google Scholar]

- Israel, Matthew. 2021. The Rise of the OVR. In Clare McAndrew. In The Art Market 2021. An Art Basel & UBS Report. Basel: Art Basel and UBS. [Google Scholar]

- Jefferies, Regina, and Jane McAdam. 2021. Who’s being allowed to leave Australia during COVID? FOI data show it is murky and arbitrary. The Conversation. July 1. Available online: https://theconversation.com/whos-being-allowed-to-leave-australia-during-covid-foi-data-show-it-is-murky-and-arbitrary-163725 (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- McAndrew, Clare. 2021. The Art Market 2021. An Art Basel & UBS Report. Basel: Art Basel and UBS. [Google Scholar]

- Myers, Fred. 2020. The Work of Art. Hope, Disenchantment, and Indigenous Art in Australia. In The Australian Art Field: Practices, Policies, Institutions. Edited by Tony Bennett, Deborah Stevenson, Fred Myers and Tamara Winikoff. New York: Routledge, pp. 211–23. [Google Scholar]

- Niemojewski, Rafal. 2021. Biennials: The Exhibitions We Love to Hate. London: Lund Humphries. [Google Scholar]

- Pacella, Jessica, Susan Luckman, and Justin O’Connor. 2021. Keeping Creative: Assessing the Impact of the COVID-19 Emergency on the Art and Cultural Sector & Responses to it by Governments. Adelaide: Cultural Agencies and the Sector, University of South Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Price, Jenna. 2020. Local galleries booming as art fiends open wallets in lockdown. Sydney Morning Herald. August 16. Available online: https://www.smh.com.au/culture/art-and-design/local-galleries-booming-as-art-fiends-open-wallets-in-lockdown-20200814-p55lym.html (accessed on 25 January 2022).

- Quemin, Alain, and Femke Van Hest. 2015. The Impact of Nationality and Territory on Fame and Success in the Visual Arts Sector: Artists, Experts and the Market. In Cosmopolitan Canvases. The Globalisation of Markets for Contemporary Art. Edited by Olav Velthuis and Stefano Baia Cuironi. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Reyburn, Scott. 2021. JPG File sells for $69 Million, as’NFT Mania’ Gathers Pace. New York Times. March 11. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2021/03/11/arts/design/nft-auction-christies-beeple.html (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- Shnayerson, Michael. 2020. Boom: Mad Money, Mega Dealers, and the Rise of Contemporary Art. New York: Public Affairs. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Terry. 2013. Contemporary Art: World Currents in Transition beyond Globalisation. In The Global Contemporary and the Rise of New Art Worlds. Edited by Andrea Buddensieg, Hans Belting and Peter Weibel. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Throsby, David, and Katya Petetskaya. 2017. An Economic Study of Professional Artists in Australia. Sydney: Australia Council for the Arts. [Google Scholar]

- Throsby, David. 2001. Public Funding of the Arts in Australia–1900 to 2000. Year Book Australia 2001: 548–61. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson-Anastasios, Meaghan. 2016. What went wrong at the Melbourne Art Fair? The Conversation. February 25. Available online: https://theconversation.com/what-went-wrong-at-the-melbourne-art-fair-55295 (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- Zarobell, John. 2017. Art and the Global Economy. Oakland: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).