Abstract

This paper presents the results of a research that was carried out in a castle in Prószków, a town near Opole, Poland. The investigations were based on the conducted architectural research, including iconographic studies and the analysis of the technology, building materials, and architectural details. The conducted research demonstrated that the Renaissance structure in question was built by Baron Jerzy Prószkowski as a palazzo in fortezza, most likely in the years 1563–1571. The residence is planned around a rectangular courtyard with four bastion towers. The scope of the architectural transformations of the complex during the baroque period and the 19th century was also presented. In the summary, it was highlighted that the castle is one of the first buildings located north of the Alps that refers to the designs of Villa Farnese in Caprarolli, which was designed by Giacomo Barozzi da Vignioli. It is in the style of palazzo in Fortezza, similar to residences in Czechia, Silesia, and Poland. Here, we emphasized the uniqueness of the complex, which stands out from other residences in Silesia and areas of the former Republic of Poland due its original form and innovative solutions.

1. Introduction

The purpose of this research was to identify the architectural structure of a castle in Prószków and to determine the ground floor plan of this palazzo in fortezza from the Renaissance. Based on our research, it was possible to understand the influence of the original form of the castle on the development of architecture in Silesia and Poland from the second half of the 16th century until the end of the 17th century. It was also possible to identify the palazzo in fortezza trend in the residence by comparing it to an original palace in Caprarola that was built by Giacomo Barozzi da Vignola. The research is important with regards to learning about the development of Renaissance architecture in East-Central Europe.

Authors who have published papers about the castle have only vaguely discussed its concept. They did not attempt to determine the extent or form of this Renaissance residence, which was erected between 1563 and 1571 by Baron Jerzy Prószkowski. The findings they presented described the Renaissance residence very imprecisely, indicating the scope of the 1677–1683 alterations made in a baroque style to only a small extent. Their findings also omitted the new-style transformations that were introduced around 1881. Therefore, more in-depth architectural research needed to be carried out and each of the construction phases needed to be identified in order to be recognized as a Renaissance residence of the palazzo in fortezza-type. Additional research was also necessary to precisely identify the transformations applied to the residence. The transformation history is based on the analyses of construction technology, building materials, mortars, and architectural detail, as well as source references and archival iconography. The results of the work enabled the authors to polemicize with the theses that have so far been presented. They also form the grounds for a detailed discussion of the castle’s residence history and transformations.

The town of Prószków is situated 10 km south of Opole, in the southern part of Poland. The castle is located in the southern part of the town, near a road that starts in the southeast corner of the market square. The residence was built on a plateau that is now surrounded by a dry moat and a park arranged around the moat. There is currently a long-term care center in the residence (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Poland and the location of Prószków, created by authors.

The first reference to Prószków can be found in a document dated 17 November 1297 (Heyne 1860, pp. 832–33). In light of the document drafted in Duke Bolko II’s office in Opole on 28 April 1336, the village of Prószków was conferred upon Knight Boldo and his heirs (Wutke et al. 1923, No. 5628). The castle was erected by Baron Jerzy Prószkowski in 1563 (the date is on the inscription board above the entrance (Figure 2)). However, the residence was damaged by Swedish troops in 1644 during the Thirty Years’ War. Its reconstruction, according to Jan Seregno’s design, was completed by Baron Jerzy Krzysztof II Prószkowski in 1677 (Königer 1938, p. 65; Kalinowski 1974, p. 34, note 46). On the 24th of November 1783, King Frederick II acquired the residence for a sum of 1,000,000 thalers. Between 1845 and 1847, the residence was used by the Royal Agricultural Academy (Settegast 1856, p. 7), and in the years 1880–1887 by the Catholic Teachers College (Heinrich and Pawełczyk 2000, p. 70). In 1930, a hospital was established in the castle (Heinrich and Pawełczyk 2000, p. 26). The restoration work in 1934 resulted in the discovery of relicts of figural sgraffito décor on the west bastion elevations (Königer 1938, p. 65).

Figure 2.

Prószków castle: the inscription board is above the entrance; photo by the authors.

The first brief description of the castle with regards to the Royal Agricultural Academy (which was then located there) and to the agricultural industry in Prószków was published in 1856 by Hermann Settegast (Settegast 1856, p. 7). A concise description of the castle’s residence history was given by Maximilian Hartmann in a monograph issued in 1893 to mark the centenary of the evangelical parish (Hartmann 1893, p. 6). The aforementioned information was repeated by Hans Lutsch in his Silesian vintage sites catalogue (Lutsch 1894, p. 243). Among post-war publications, much more information about the residence was given in a paper by Ernst Königer (Königer 1938, p. 65). The author discussed the reconstruction of the castle in the second half of the 17th century and came to the conclusion that the work had not changed the appearance of the structure significantly. He also mentioned some work that had been done inside the castle in the 19th century. He was the first to present photos and very detailed descriptions of the discovered sgraffito décor (Königer 1938, p. 65).

The castle was thrice mentioned by Tadeusz Chrzanowski. The author described it for the first time in his paper concerning manor houses and castles in the Opolian region (Chrzanowski 1965, pp. 277–84). According to him, this Italian Renaissance residence was built in 1563 with rich sgraffito décor and bastion fortifications, used in Silesia for the first time. He also stated that the inner courtyard had been surrounded by cloisters, which were later bricked up. In their vintage sites catalogue for the town and county of Opole, Chrzanowski and Marian Kornecki described the architecture and transformations of the residence in detail (Chrzanowski and Kornecki 1968, pp. 109–13). The authors highlighted the Renaissance details that had survived: window trims on the side and rear elevations, and portals inside the building. They paid attention to the fortifications, the moat, and the southwest fortified tower, the construction of which was dated by the authors to 1563 when the residence itself was built. They associated the bastion outline with the reconstruction of the complex in 1677, and its levelling with the activities conducted in the 19th-century. Both of the authors resumed the subject of the Prószkowskis’ residence in their work on the art of Silesia in the region of Opole (Chrzanowski and Koniecki 1974, pp. 154–58). They counted this residence, and Brzeg Castle, among Silesia’s most significant castles, paying attention to its advanced bastion fortifications, which were more modern than both the tower and the fortified tower-based solutions of the day. They noticed that the solutions had preceded other structures of that type—not only in the region of Opole but probably in Silesia as well. They indicated that the bastion system that was mostly used for fortifying towns and residential sites at that time had been integrated with the castle in question. Moreover, they stated that Prószków Castle was one of the first buildings where cloistered courtyards without sculpture décor had been built, and where geometric and figural sgraffito had been applied to elevations. The authors were not sure what the building’s original appearance had been, especially with regards to what the roofs may have looked like. They also did not know when the pair of the towers in the east wing had been built.

The 1677-1686 alterations made by Baron Jerzy Krzysztof II Prószkowski were considered by Konstanty Kalinowski in a wider context of baroque art movement in Silesia (Kalinowski 1974, pp. 34–35; Kalinowski 1977, p. 35). The author was of the opinion that the towers and the belvedere that was situated between them had been added by Jan Seregni, and that the projection of four wings and an elongated inner courtyard, as well as front avant-corps bays, refer to a Renaissance-type of building. He also stated that the layout of the interiors, which have a single longitudinal section, had not been subjected to major modifications when the alterations were made, and that a new stucco décor had been applied to only some of the rooms. In turn, there were changes in the arrangement of the courtyard walls—the pillared cloisters had been bricked over, the pillars in the basement along the longer walls had been replaced with Tuscan pillars and flattened arcading, and the open galleries on the higher storys had been removed.

The findings of Chrzanowski and Kornecki are quoted by Bohdan Guerquin (Guerquin 1984, p. 261) and Józef Pilch (Pilch 2006, pp. 164–66). The history of the castle and town, based on archival materials and references, was published by Erhard Heinrich and Andrzej Pawełczyk (Heinrich and Pawełczyk 2000, pp. 16–24, 45–47). The sgraffito décor of the elevation was discussed by Marzanna Jagiełło-Kołaczyk (Jagiełło-Kołaczyk 2003, p. 247).

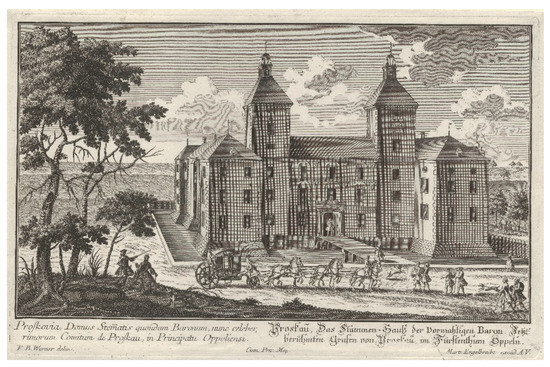

The considerations of the castle’s architecture are supported by iconographic images, with the oldest view being drawn by Valenty Saebisch, dated to the beginning of the 17th century (BN sygn. WAF.44,R.4575-4621). A second drawing, which is dated to approximately 1735, shows the structure from the façade side (ÖNb sygn. KAR051249). It presents the castle, which has wings covered with a high gable or hipped roofs, and two towers that emphasize the central axis and the portal. The 19th-century and early 20th-century views, postcards, and photographs, which are available on websites (at polska-org.pl, accessed on 5 March 2020; fotopolska.eu, accessed on 5 March 2020) and books (Lakwa and Lakwa 2010), showed that the residence’s shape was similar to that of the present (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Prószków castle: view from the southeast from approximately 1735, drawn by Friedrich B. Werner; the lithography prepared by Martin Engelbrecht, source: © Österreichischen Nationalbibliothek, signature: KAR0512490, used with permission.

2. Results

The castle has a 45 m wide and 58 m long elongated rectangular plan. In each of the four corners lies a bastion. There are four wings around its inner courtyard. The bastions are built as low towers in order to emphasize their shape. The east pair of the bastions has a square-like plan, and the pair of west bastions has a deltoid plan. The castle is a three-story structure, part of which has cellars. It has a brick plinth and is surrounded by a dry moat. Two of the castle’s towers are capped with baroque cupolas with a single roof lantern, each accentuated with a flat-roofed front wing. The other wings are covered with tiled gable roofs (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Prószków castle: east elevation; photo by the authors.

The building’s facade faces east and has 11 window axes. It is flanked with two low and three-axis bastion towers. There is a gateway in the middle of the façade, along the facade’s axis. The gate is framed with a rusticated portal, the segmental capping of which rests on pilasters. It is accessible via a three-span bridge which crosses the moat. Above the first-floor windows, there is a cartouche showing the coat of arms of Baron Jerzy Prószkowski, which is inscribed with the year 1563 (denoting the year the castle’s construction began). The appearance of the south elevation is similar to that of the façade, but the two towers have two window axes each. The north elevation has 13 window axes and a varying number of openings. In the west tower, the axes vary between two and four per window. The west elevation has eight window axes, except for the ground floor where there are seven axes. The architectural ornaments of the windows are also diversified; in the south elevation (excluding the east avant-corps) and in both of the west avant-corpses. These windows are framed with stone, Renaissance fascias, while in the other elevations they are surrounded by plastered, shaped trims with open pediments and keystones in the baroque style. The windows located in the plinth area are not trimmed and have segmental arches in the window heads (Figure 4 and Figure 5a,b).

Figure 5.

(a) Prószków castle, west elevation—north corner photo by the authors; (b) Prószków castle, west elevation—south corner photo by the authors.

The courtyard has a 23.0 m long and 14.7 m wide rectangular plan; its longer sides face south and north. Both of the elevations have three storys and eight window axes. The shorter sides have six window axes (in the east-facing elevation) or five window axes (in the west-facing elevation). Arcades supported by pillars can be seen on the ground-floor elevations of the longer building sides. On the west elevation, there are relicts of a loggia, which consisted of three story-high arcades supported by columns or semicolumns. Today, the arcades are bricked up. The gate opening in the basement of the opposite elevation is decorated with a semicircular arch and is preceded by a vaulted hall (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Prószków castle, courtyard, view from the south–east; photo by the authors.

3. The Results of the Research

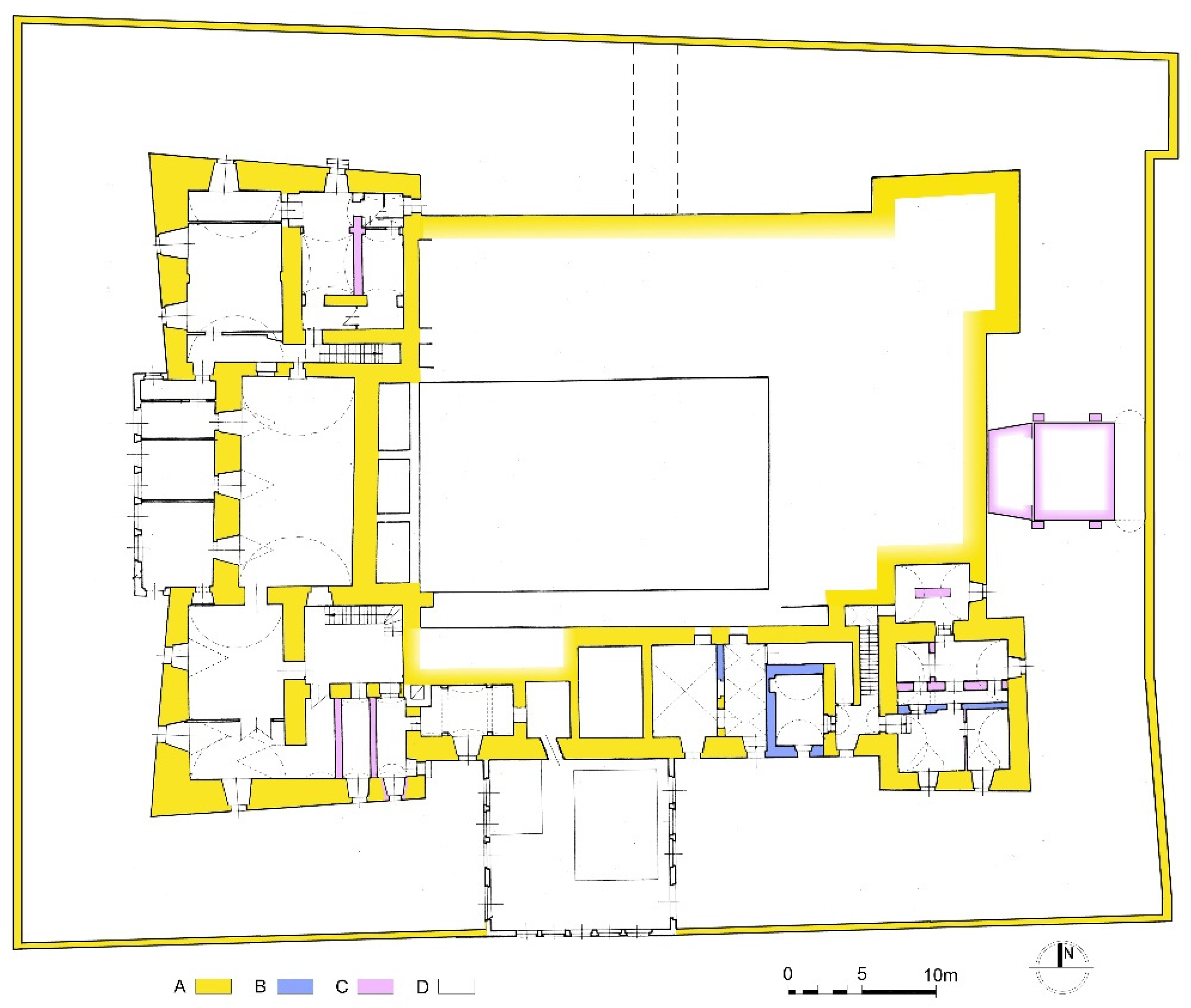

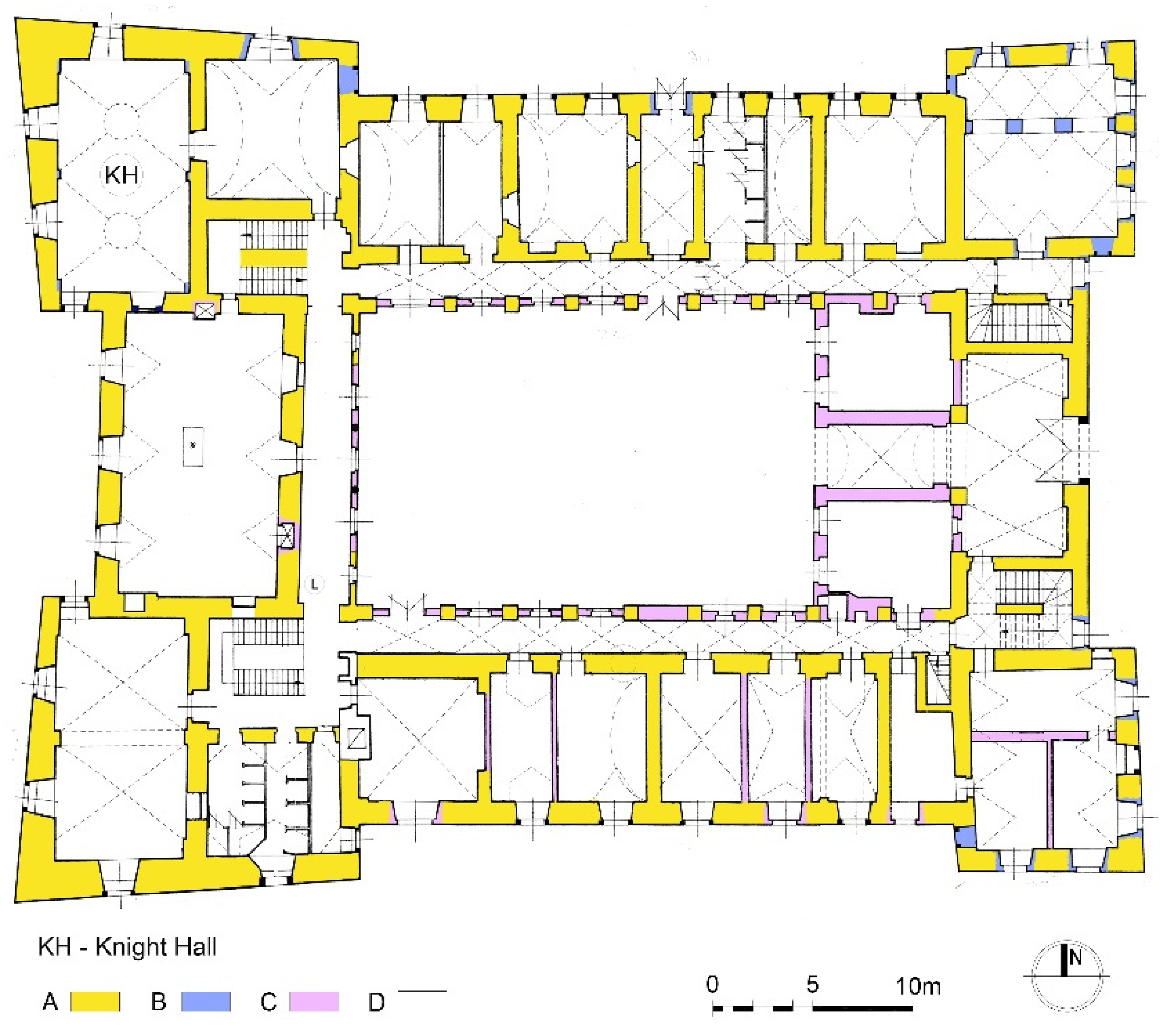

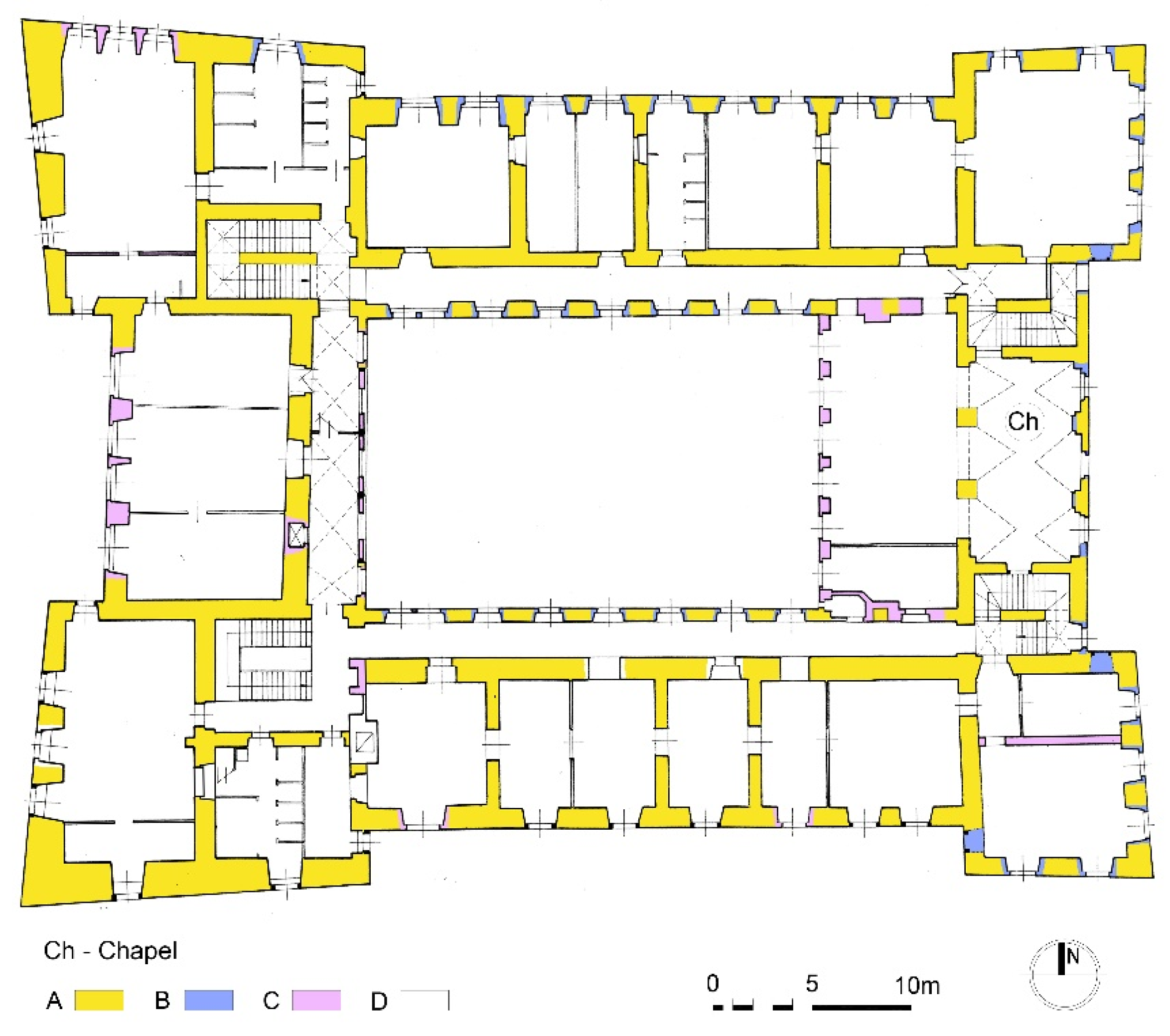

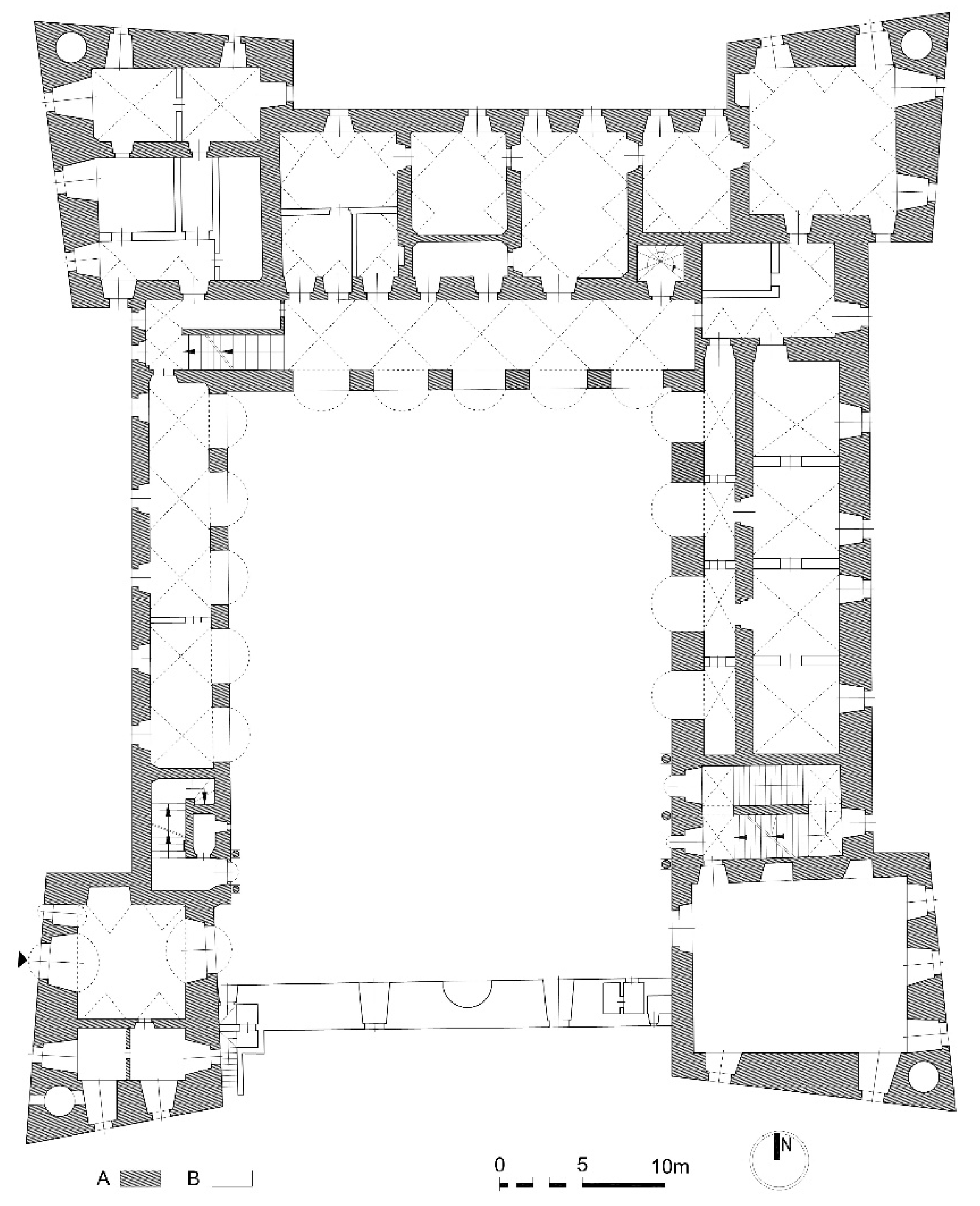

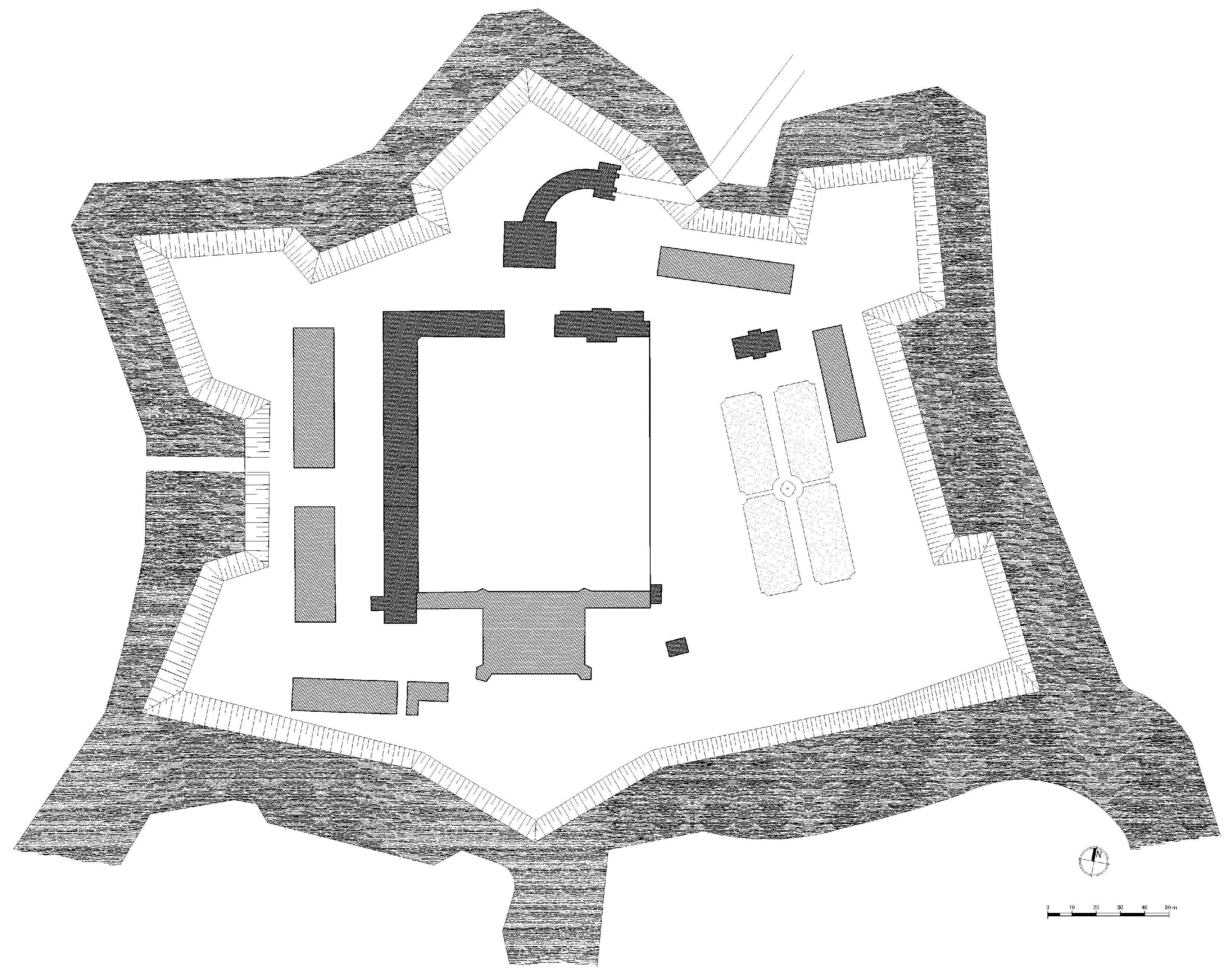

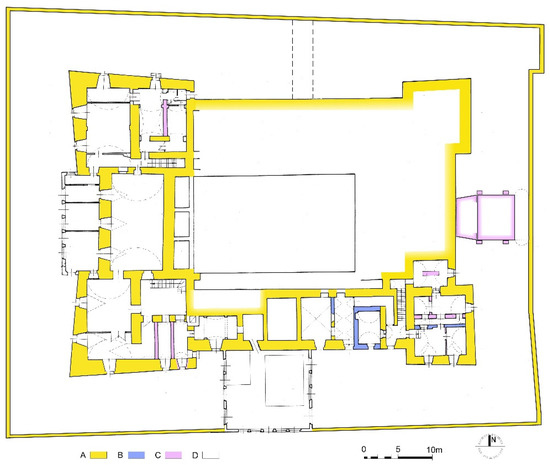

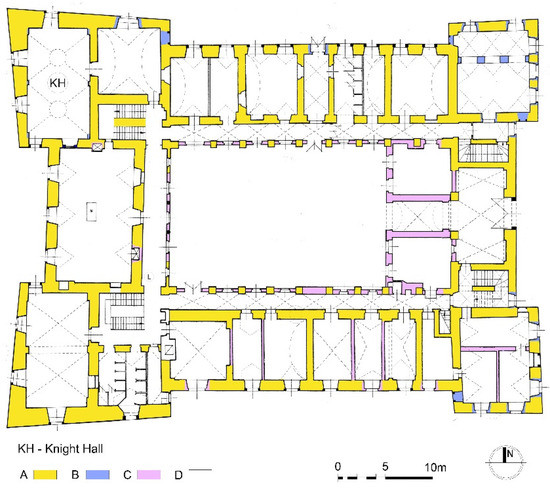

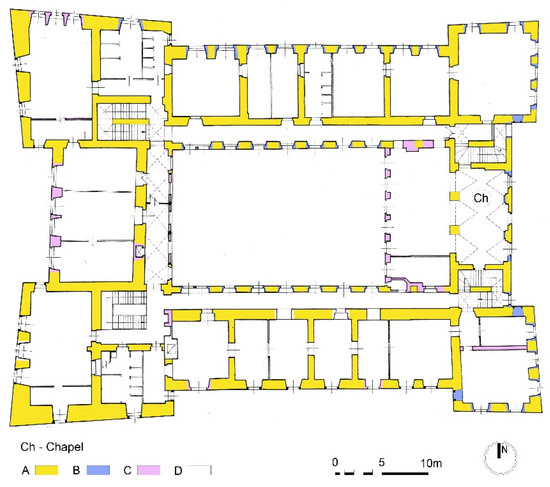

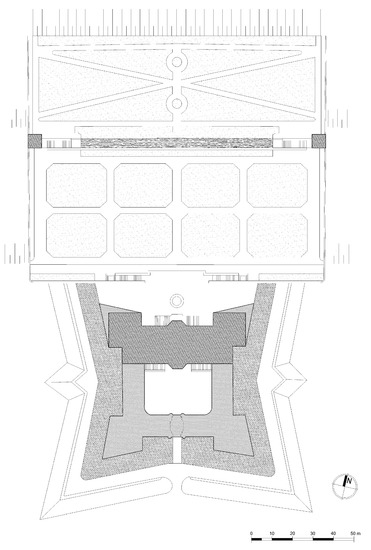

The original Castle in Prószków was built by Baron Jerzy Prószkowski, probably in the period from 1563 to about 1571. The time of erection of the Renaissance residence is confirmed by the date on the inscription board over the entrance gate. The chronology of transformations was confirmed by the results of stratigraphic and laboratory studies (Skarbek 2009, pp. 2–12; Wanat 2010, pp. 2–21). It was erected as a classic palazzo in fortezza from the foundations, in cruda radice, and its plan overlapped almost entirely with the present one. The site was on a plateau at the highest point of a small hill. The building was outlined with a deep dry moat. The castle had an elongated rectangular plan with outer dimensions of about 45 × 58 m, and its corners were strengthened with low towers on bastion plans. The pair of the east towers had square-like plans, and the pair of the west towers had deltoid plans and well defined corners. The entire residence was probably surrounded by an additional line of fortifications, of which a semicircular fortified tower on the southern side has survived (Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9 and Figure 10).

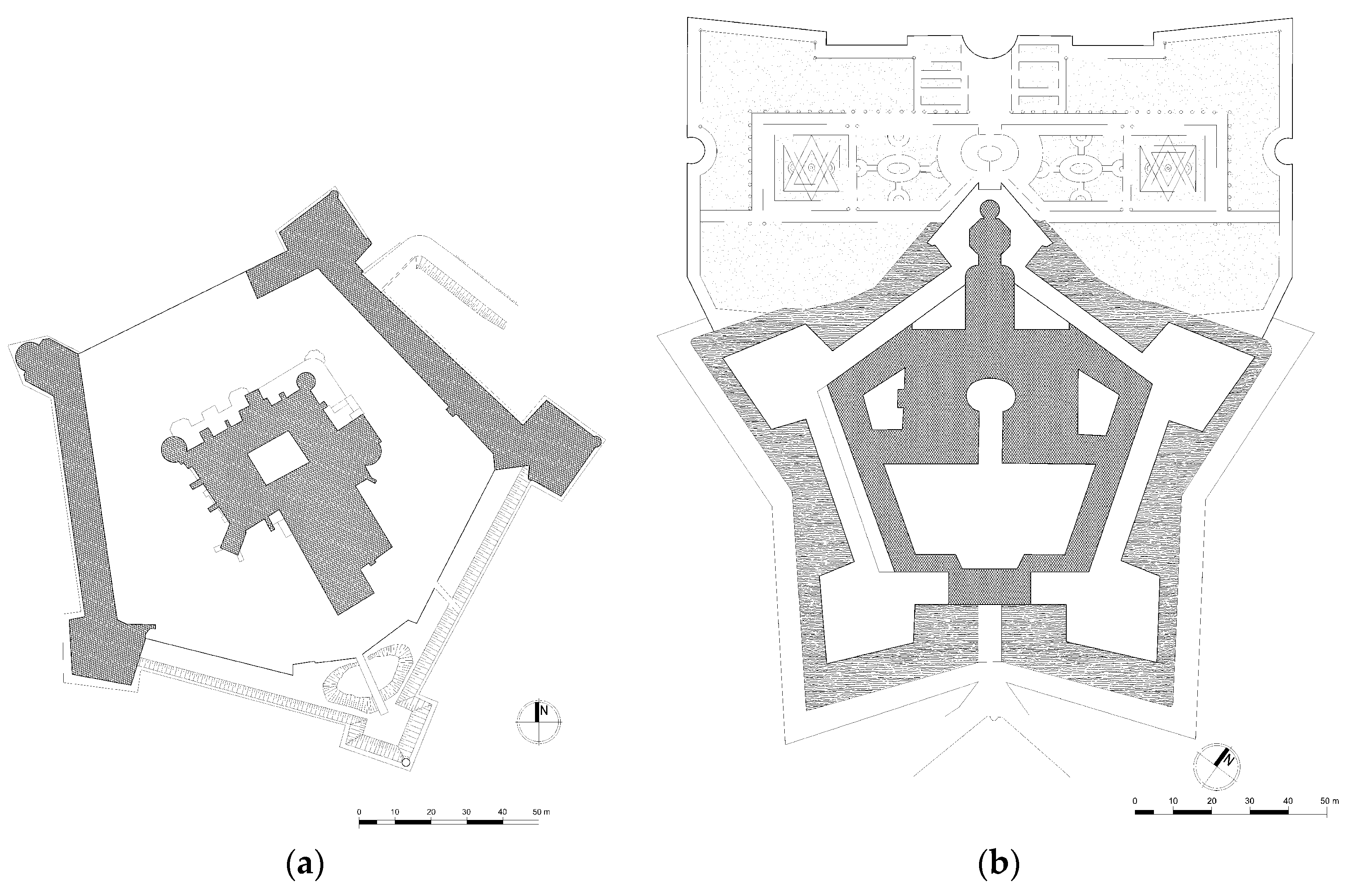

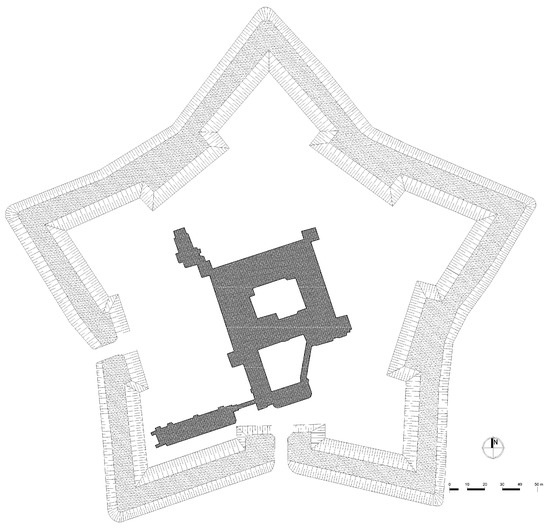

Figure 7.

Prószków castle: cellar floor plan with chronological stratification of the walls. Legend: A—Renaissance (approximately 1563); B—Baroque (1667–86); C—1881; D—walls unknown and from the 20th century, created by authors.

Figure 8.

Prószków castle: ground floor plan with chronological stratification of the walls. Legend: A—Renaissance (approximately 1563); B—Baroque (1667–86); C—1881; D—walls unknown and from the 20th century, created by authors.

Figure 9.

Prószków castle: first floor plan with chronological stratification of the walls. Legend: A—Renaissance (approximately 1563); B—Baroque (1667–86); C—1881; D—walls unknown and from the 20th century, created by authors.

Figure 10.

Prószków castle: second floor plan with chronological stratification of the walls. Legend: A—Renaissance (approximately 1563); B—Baroque (1667–1686); C—1881; D—walls unknown and from the 20th century, created by authors.

The residence was designed as a three-story building; the cellars, as another story, were built in the south and west wings only. The elevation was built on a rusticated plinth that was probably rendered and separated from the wall with a shaped cornice. Above the plinth, the flat elevations were accented with avant-corpses in the corners and regularly spaced window axes. The longer south and north elevations might have had 11 window axes each. On the shorter east and west elevations, there might have been seven window axes. In the towers, there were two outermost window axes and additional windows in the side walls. The openings were trimmed with stone fascias in Gothic styled forms with interpenetrating molded shapes in the upper corners. The entrance to the castle was situated on the base of the east wall and was preceded by a wooden bridge, the last span of which could be pulled up. Traces of lifting elements have survived above the cube portal that framed the gate opening. Above the portal was a cast iron plaque with an inscription stating that the castle had been funded by Baron Jerzy Prószkowski, a treasurer and counsel of Emperor Rudolf II. The inscription carved on the plaque reads: “DEO OPT: AVSPICIE: CVM SERENISSIMUS ROM: REX MAXIMILIANVS INTRA VNIVS ANNI SPACIVM TRIBVS TRIVM REGNORVM CORONIS INSIQVIRETVR GEORGIVS PROSCOVIVS A PROSCAV BARO MAIESTATI ILLIVS A CVBICVLIS QVI HIC OMNIBVS CELEBRITATIBVS INTERFVIT AB AVLICA VITA AD OTIVM SESSE REFERENS HASCE AEDES EXTRVERE COEPIT ANNO CHRISTI MDLXIII” (which can be translated as: With God (In God), the best and most powerful protector (protection). Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian, with three crowns in his power, hereby makes Jerzy Prószkowski of Prószków, who built this castle in AD 1563, a baron), cf. (Heinrich and Pawełczyk 2000, p. 100).

The castle was covered with gable roofs, the ridges of which were parallel to the longer walls. The bastion towers were probably covered with separate, short-ridged hip roofs. A mono-pitched roof was probably applied to the loggia that was built in the west wing.

The relicts that have survived on the elevations of the northwest bastion tower indicate that the walls were abundantly decorated with sgraffito, as was probably the case with the other external walls (Figure 11a). The sgraffito is thought to have consisted of five strips separated from each other with illusive cornices aligned with the windowsills and headers. Unfortunately, its condition makes the full interpretation of each of the scenes impossible. The lowest strip, which forms the basis for the composition, consisted of rectangular rusticated blocks. The higher strips contained figural scenes which presented allegories, Biblical scenes, or battle–related events. The lowest of the figural décor strips on the west elevation probably presents seven mythological muses dancing on flagstone flooring. The supposition that the presented figures are muses is likely based on the surviving fragment of the rightmost figure, which holds a book and a stylus in her hand (Calliope (probably)). Above her, there is a person on a horse and also a king in a sitting position holding an apple in his hand. The lower part shows an unidentified battle, a scene of a besieging army. Conical tents are presented on the north elevation. Another strip, the second from the top on the west elevation, shows a fragment of a scene in which there are three men. The first man, likely representing wisdom, is an elderly scholar in a sitting position and with an astrolabe in his hand. The second is a richly dressed dignitary kneeling and showing a position of faith. The third fragment has the hand of a third man who is holding a whip, the use of which on himself might bring humility (?). The corners of the avant-corps are emphasized with rusticated rectangular quarters that break along the edges and have square patches with candelabrum ornaments. Interestingly, over 40 ornaments have survived and not one is repeated. On the north elevation, the second-floor window trims have also survived (Figure 11b). They imitate the architectural décor that consists of a sill aligned with sgraffito cornices, which separates the figural décor strips from each other. A pair of pilasters decorated with grotesque ornaments is set on the sill. The pilasters support an illusively shaped, flat pediment. It seems probable that the other windows were framed similarly. The shaped stone framing was pained iron oxide red. The finial below the main cornice was filled with a frieze decorated with arabesque (a dense acanthus ornament) and grotesque (putti and unicorns) (Jagiełło-Kołaczyk 2003, pp. 247–51) (Figure 5a).

Figure 11.

(a) Prószków castle: west elevation of north bastion, part with sgraffito, scene with mythological muses, upper king and person on a horse, photo by the authors. (b) Prószków castle: north elevation of north bastion, sgraffito decoration, photo by the authors.

The architecture of the 30.0 m long and 14.7 m wide courtyard was designed differently. There were arcaded cloisters in the south and north wings and a loggia in the west wing. In the basement of the east wing, there was a three-span hall that faced west through three arcades. Above the arcades, there were probably three windows that lit the chapel. Rainwater from the cobbled courtyard was probably disposed to the moat via two gutters, the stone gargoyles of which were placed on both sides of the bridge.

The eastern facade of the west wing, on the axis of the gateway, is decorated with a three-story, three-span loggia. The middle arcades were supported by two marble columns, and the outermost arcades were built on pillars (on the ground floor) and on marble semicolumns. A burgundy stone with white veining was used for making architectural elements. The elevations were neatly rendered and the top layer received a high-quality finish. The color scheme applied to the courtyard walls differed from that applied to the external elevations, which were all painted ochre. The details were painted with a slightly darker hue.

The castle’s layout had a 1.5-longitudinal section in the south, west and north wings, and had cloisters from the courtyard side for accessibility. The east wing was arranged as a single longitudinal section that housed a chapel. The chapel was covered with a barrel vault and three pairs of lunettes, and had its north and south-facing entrances trimmed with fascias (Figure 6).

Four two-flight staircases were built in the courtyard corners; the pair of east staircases was accessible from the entrance hall. The rooms in the south and north wings were designed as an enfilade. Secular, ceremonial rooms were probably situated in the west wing and in the flanking bastion towers. One of them, the room in the northwest tower, was covered with a barrel vault and two pairs of lunettes, and the edges at the intersection of the vaults were decorated with triangular patches. The entrance to the room was trimmed with stone fascias that were shaped similarly to those in the window framing.

Soon after it had been completed, the sgraffito décor was probably destroyed or seriously damaged on the southwest bastion tower (in the late 16th century). A small relict of that décor is presented on the south elevation; it follows the original pattern to a significant extent. The corners of the avant-corps were decorated with rusticated rectangular quarters, but no patches with candelabrum ornaments were introduced. The horizontal divisions were strongly emphasized with an arabesque frieze made of acanthus ornaments and putti, which were located in the line of the pediments.

Probably at the beginning of the 17th century, due to the poor condition of the west and south elevations, the third decoration was made using the sgraffito technique. It was much more simple than the previous ones. No figural decorations or ornamental friezes were applied. The rusticated blocks were separated with stripes of illusive cornices in the line of the windowsills and pediment lines, and the corners were decorated with quarters. Below the cornice, there was a frieze in the form of illusive entablature and brackets (Figure 5b). The castle was partly damaged by Swedish troops during the Thirty Years’ War, probably in 1644. Restoration of the residence was almost certainly started in 1677 by Count Jerzy Krzysztof II Prószkowski, Emperor Ferdinand’s counsel and treasurer. The design for the re-building was developed by Jan Seregno, an architect and stucco mason from Milan, Italy (Königer 1938, pp. 32–33).

The transformations of the structure, in a baroque style, included the introduction of a pair of towers to emphasize the east façade. The towers were two storys higher than the roof eaves. They were topped with onion-like cupolas, each with a single lantern level and a finial. A terrace was most likely introduced between the towers. The terrace might have been accessible from a lower story in the tower. The door framing offers access to the terrace to this day. However, the flat roof was changed to a pointed one in 1856 (Figure 5a).

The elevations were decorated in a new but still Renaissance style. The sgraffito décor was replaced with smooth rendering, and the corners were rusticated prominently. The window openings were trimmed with rendered, shaped elements with prominent keystones and springers on the upper storys, and with pediments with bell decorations and sills on the ground story. The rendered Renaissance framing in the south wing, the west bastion towers, and on the ground story remained unchanged. The new windows in the east wing on both the north and west elevations were trimmed with avant-corpses. A cartouche with the coats of arms of Count Jerzy Krzysztof II Prószkowski and his wife, Countess Maria Rosally von Thurn-Valensin, was put along the façade axis above the entrance. The escutcheons and the plaque beneath the cartouche were surrounded by cartilage decoration supported by two putti. A similar cartouche, containing only the coat of arms of Count Jerzy Krzysztof and an empty patch, was put above the north elevation portal. The rectangular opening was trimmed by a shaped arc with a keystone and rusticated framing that supported a simple pediment, above which were the two above-mentioned escutcheons and two putti. The third cartouche was put on the north tower elevation above the lower window trim. A slightly different color scheme was applied to the external walls—the brick, in a red color of the architectural detail, remained, but the background was painted in light salmon to lighten up the detail.

The existing wooden bridge was rebuilt. New bricked spans were built in place of the two existing spans. The east one was supported by an arcade. The last span near the castle remained liftable.

The courtyard was also subjected to alterations. However, the east elevation remained almost unchanged except for an elliptic recess along its axis. The Renaissance loggia with open arcades on the west elevation remained in place. Two baroque portals with stylish framing and pilasters that supported a segmental pediment were added on the second story. They flanked the rectangular window that was built along the axis and which was decorated with baroque stylish trimming and bell decor. The upper and lower framings had decorative keystones and the side framings were decorated with springers.

The largest scope of transformations covered the southern and northern facades of the courtyard. The arcaded cloisters on the upper storys were demolished, leaving only the pillars. The cloisters were replaced with rectangular windows trimmed with bell decorations and shaped elements in a baroque style, and finished with a keystone at the top. In turn, the basement arcades were finished with shaped archivolts with prismatic patches above the framing. The changes to the interior design resulted in the introduction of a new color scheme. The uniform composition was emphasized by detailed decorations in a dark ochre color, and a background that was probably in a lighter uniform color (Figure 5a and Figure 6).

Alterations were also introduced to the interiors of two ceremonial rooms, the so-called “Knights Hall” and the chapel. Attention should be paid to the fact that the baroque interference in the interior decoration was limited to the redecoration of the rooms in an epoch-specific style. The Knights Hall was situated on the ground floor of the avant-corps at the northwest bastion tower. It received a barrel vault and two pairs of lunettes. A rich architectural detail was applied to the bowls: it consisted of stucco decoration—a variety of plafond decorated with ogees and bunches of fruit, which draped around the heads of the pillars situated in the corners and in the middle of the longer walls. In addition, niches with shell-like vaults were built in the south and north walls and in the reveals of one of the windows. They were framed with shaped elements, which had the same color as the cornices at the base of the archivolts, and which were finished with keystones decorated with mascarons or bunches of fruit. Allegorical figures were put into five niches (Figure 12).

Figure 12.

Prószków castle: interior of the ceremonial room called the “Knights Hall”; photo by the authors.

As mentioned above, the castle chapel was situated in the east wing above the entrance hall, and was decorated like the Knights Hall. The chapel was probably lit through at least five window openings, of which three faced the courtyard and at least two faced east. The altar might have been between these two windows. The vault was richly decorated with motives like those in the “Knights Hall”. The decoration consisted of plafond in fancy shapes, surrounded by ogees and floral motives.

The residence was adapted by the Agricultural Academy in 1856. The terrace between the towers was demolished and replaced with a flat roof. Square clock faces were installed just beneath the cupolas along the elevation axes. Similar flat roofs were also built on top of the east bastion towers. The construction of a wooden structure above the hall in the west wing was a significant change to the interior decoration. The interiors in the southeast corner of the tower, as well as in the rooms of the ground floor and the second floor in the south wing, were partitioned.

Serious construction work was carried out in the castle to convert the rooms to hospital wards in around 1881. During these works, the eastern wing was enlarged at the expense of the courtyard by introducing a three-story six-axis building with a flat roof. The west elevation was decorated with architectural detail in a baroque style. The existing entrance hall in the basement remained, but its outermost arcades were bricked up. A two-span hallway was built along the main entrance axis to connect the entrance hall with the courtyard. The extended east wing interiors were linked to the existing communication routes. Three arcades were made in place of the former west-facing windows in the chapel on the first floor. The new room was covered with a flat ceiling, which diverged from the rich baroque decoration of the chapel’s vault. The new building obscured the upper part of the elevation with an elliptic recess, which became a part of the room situated above the chapel.

In the courtyard, the baroque arcades in the north and south basements were bricked up in order to build walls and windows, the framing of which resembled baroque decorations. The loggia in the west wall was also bricked up, with rectangular windows being built in each of the spans in the bricked up area.

The extent of the work in the west wing was slightly smaller. The south staircase was altered. The window openings on the first and second storys of the bastion avant-corps elevations were re-arranged. New window openings were added, or the existing ones were enlarged on the south elevation and in both of the west avant-corpses. Wattle and daub partitions were built in the rooms on the ground floor in the southeast tower, on the ground floor in the south wing, in the northwest tower, and also on the second floor in the south and north wings. The existing bridge in front of the façade was rebuilt and the liftable span was replaced with a fixed span. A few east- and south-facing cellar windows were bricked up.

Relicts of sgraffito décor were discovered on the external elevations of the pair of west bastion towers during the repair work that was carried out in 1934. The exposed décor was then subjected to conservation and partial reconstruction. In particular, repeatable elements (rusticated cut stones, cornices) were conserved, and Renaissance stone window trims were displayed.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

After studying the source references and analyzing the architecture in detail, the authors were able to determine the extent and layout of the original palazzo in fortezza that was erected by Baron Jerzy Prószkowski between 1563 and 1572. During the Thirty Years’ War, the residence was likely damaged. The conversion that followed in the years 1677–1686 gave the castle a baroque appearance. However, it did not significantly change the castle’s layout, and instead caused the castle to maintain its structure and some of its Renaissance details. The 19th-century adaptation of the castle by the Royal Agricultural Academy, and then its adaptation to a hospital, caused a decrease in size of the courtyard area and an increase in the size of the chapel. The conservation work performed in about 1934 resulted in the discovery and conservation of relicts of the figural sgraffito décor on the west elevations.

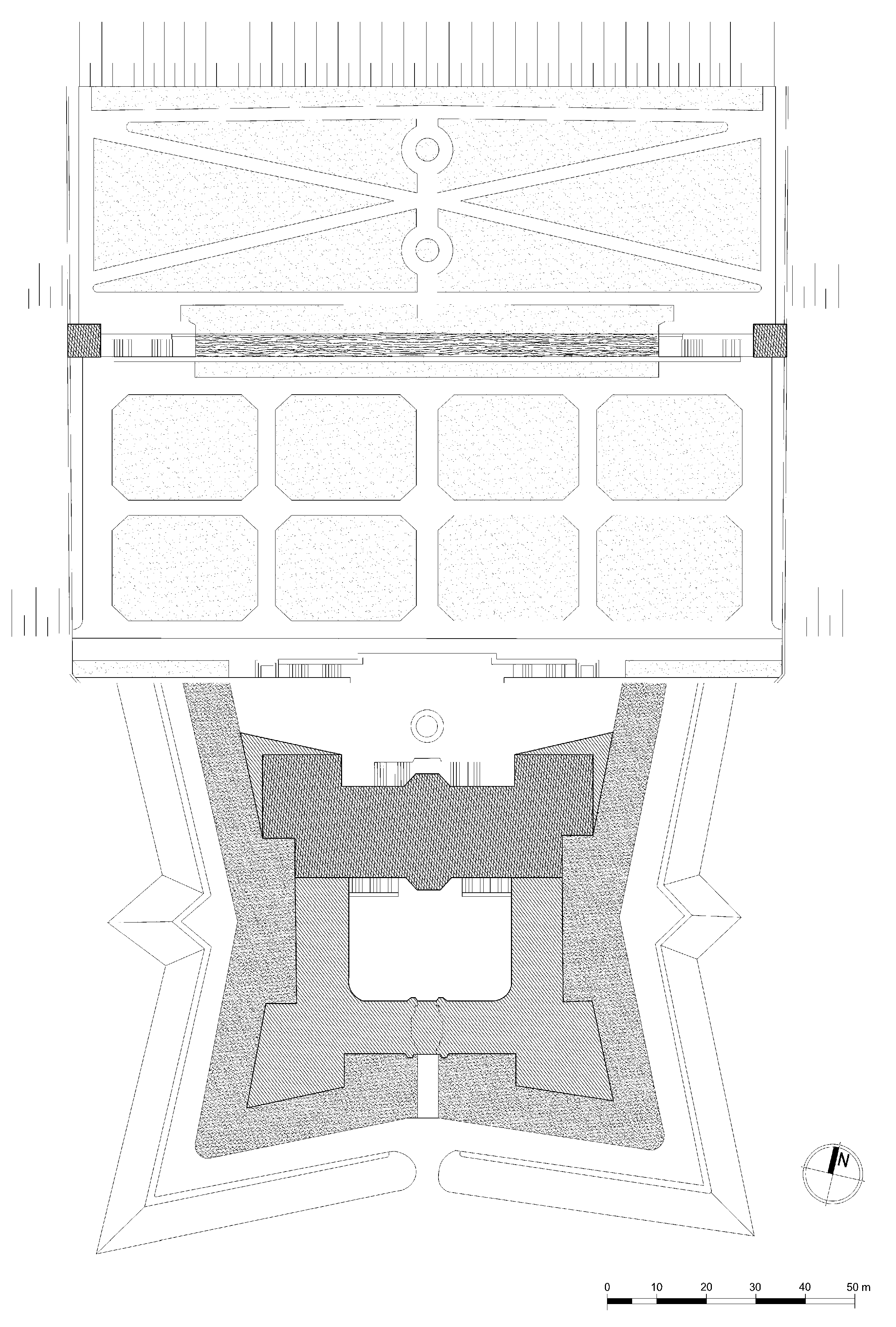

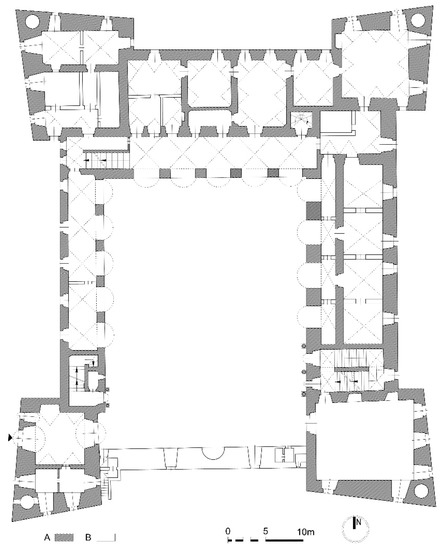

The conclusions drawn from the results of the research and from the analysis of the source references enabled the architecture of Prószków castle, when compared to other residential structures in Bohemia, Silesia, Pomeriania and former Poland, including Poland’s Eastern Borderlands, to be discussed by the authors (Wąs 2007, pp. 123–207; Gołębiewski 2020). The unique layout solutions and its very regular plan gives the authors grounds for perceiving the castle as an innovative structure. The construction of the castle followed the trend towards the palazzo in fortezza-type of residences in Bohemia in about the middle of the 16th century under the rule of King Ferdinand I. The King’s advisor, Florián Gryspek of Gryspach, erected two structures between 1540 and 1563. Florián Gryspek built the castle together with two corner bastion towers in Kacelově. Between 1553 and 1588 he engaged the royal architect Bonifaz Wohlmuth to build the castle with four bastion towers in Nelahozeves (Vlček 1998, pp. 39–40; Malý and Masaryk 1908, pp. 276–78). The latter structure, due to its plan and shape, might have been a model for the Prószków residence. Baron Jerzy Prószkowski commenced building in 1564, which is confirmed by the results of the research and the study of the inscription on the cartouche over the entrance portal. The date of completion of the construction works, and also probably the elevation works, is determined by the fact that he purchased the castle at Stare Hrady in Bohemia. Baron Prószkowski had been involved in the conversion and extension of Stare Hrady castle since 1572 (Heinrich and Pawełczyk 2000, pp. 52–54). The scale and pace of work on the two structures not only reflected the funder’s wealth but also his good knowledge of art trends developed in the Praha court circle in the second half of the 16th century (Figure 13).

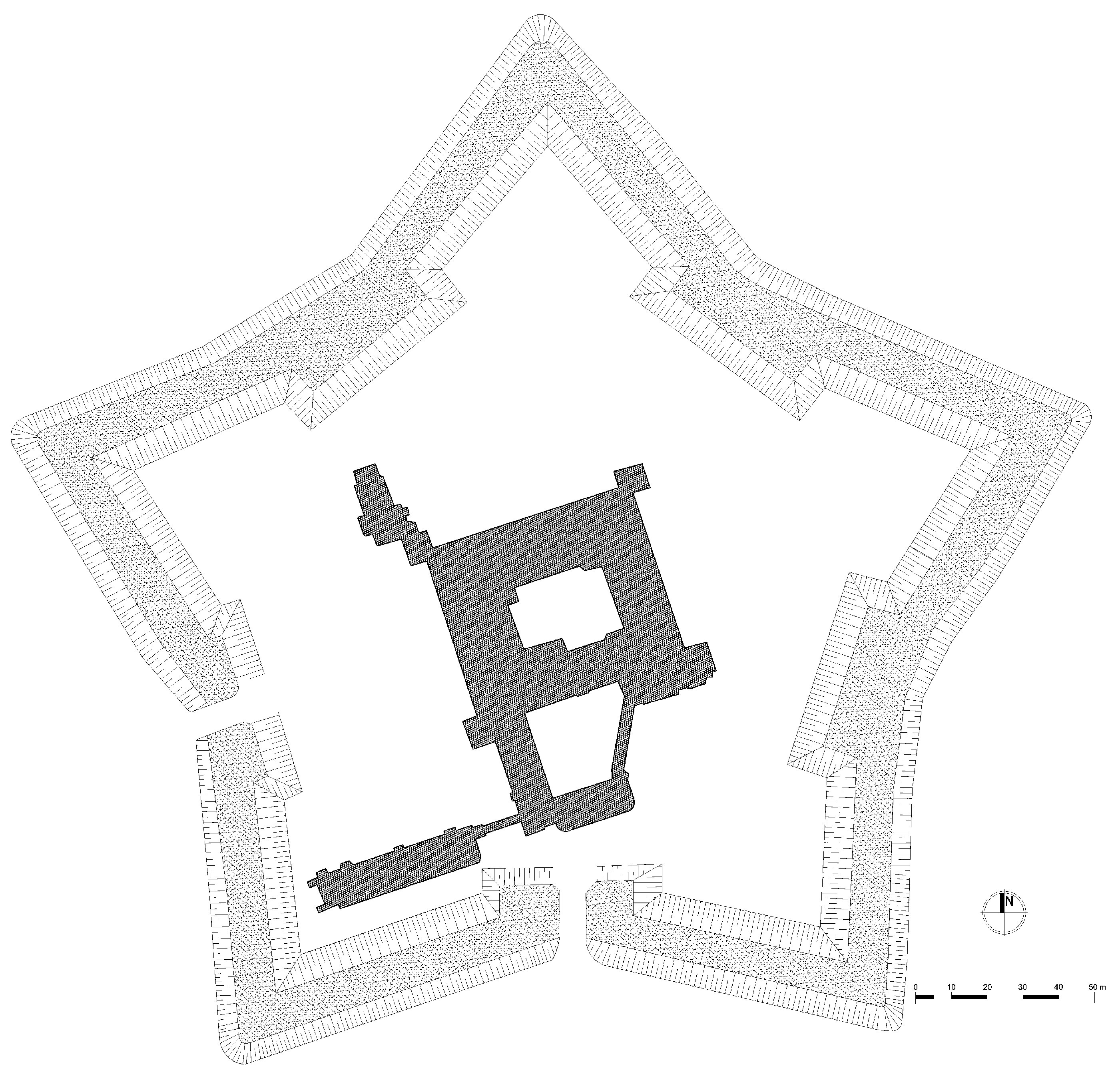

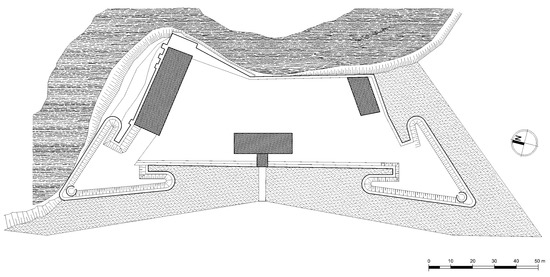

Figure 13.

Nalahozeves castle: ground floor plan; created by authors.

The use of innovative elements in the castle in Prószków includes its regular plan of the palazzo in fortezza type, and also the arcaded courtyard. These two aspects should be discussed in the context of other structures built in the 16th and 17th centuries in Silesia and Poland.

The plans for the Prószków residence were probably conceived by an unknown architect who was well acquainted with the works of Renaissance theoreticians and who was also active in the Praha court– for example: the castle of Nelahozeves was designed by architect Bonifaz Wohlmuth who was involved in the construction of royal residences (Vlček 1998, pp. 39–40). The architect designed a castle with a very regular plan and layout that was typical of 16th-century Renaissance residential premises, and which strongly referred to Italian architecture. Due to the introduction of the bastion towers to the corners of the rectangular plan, Prószków castle became part of the so called palazzo in fortezza trend. Such a solution of residences of wealthy families was very common in Silesia. It needs to be mentioned that in the 1st half of the 16th century there were also older (even Gothic) structures surrounded by modern fortifications with a regular plan and circular fortified towers. Such an example is the palace of the family of von Stoschs in Witostowice near Henryków (Pilch 2004, pp. 396–97). However, the solutions proposed in Prószków, e.g., the arrangement of the bastions and the location of windows in the short walls, were avant-garde. With the present state of knowledge, when analyzing other structures of the palazzo in fortezza type in Silesia, it can be seen that they were definitely built later than the castle in question, and that their fortifications only form the framing of a multi-winged complex that is built around an inner courtyard. The three-winged palace built by Judge Andreas von Jerin in Siestrzechowice near Nysa in about 1594 can serve as an example of this type of structure. The palace had a rectangle-like plan and was surrounded by a rectangular rise with four earth-filled bastions (Legendziewicz 2019, pp. 17–29). No such solution was applied to the two most important residences of Silesia’s dukes—the castles in Legnica and Brzeg. The former was surrounded by fortifications and fortified towers between 1529 and 1533 by Frederick II, Duke of Brzeg (Eysymontt and Goliński 2009, p. 39). The latter was subjected to a staged conversion between 1544 and 1560, which excluded the construction of fortifications. Such fortifications were not built around the castle and the city until the late 17th century (Kozakiewicz and Kozakiewicz 1976, pp. 144–49; Zlat 2010, pp. 167–70; Kajzer et al. 2001, pp. 113–16, 262–65).

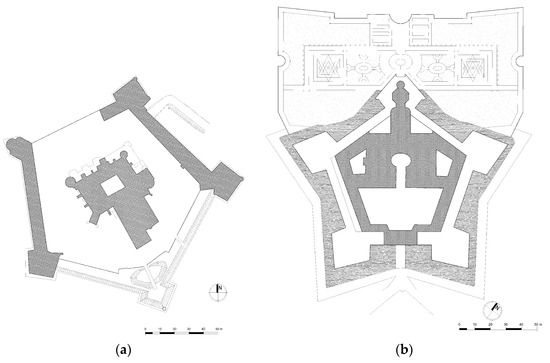

One of the oldest palazzo in fortezza in Italy is the castello di Alviano from 1520 (Mosca 2018), and also Villa Farnese, which was built by Vignola in 1534 in Caprarola (Bussagli 2018, pp. 365–67; Frommel 2007, p. 187–89; Lotz 1977, p. 154). The palazzo in fortezza idea was quickly adopted in the area of Central Europe, Czechia, and Silesia. In Poland, palazzo in fortezza structures definitely appeared much later than in Silesia. The castle in Baranów Sandomierski built for Andrzej Leszczyński, probably by Santi Gucci over the period from 1591 to 1606 (Maciąga 1981, pp. 257–73; Żabicki 2013, pp. 232–33), can be considered the oldest. It is a simple palace built on a rectangular plan with circular towers in the corners, and surrounded by bastion fortifications. Stanisław Lubomirski’s castle in Nowy Wiśnicz looks similar (Figure 14a). Its original layout was gradually extended and its pentagonal bastion rise was designed by Maciej Trapola and built in the years 1615–1621 (Miłobędzki 1980, pp. 92, 162–64, 170, 173). The Krzyżtopór castle in Ujazd is the most outstanding example of palace and military architecture. It alludes to Palazzo Farnese in Caprarola, designed by Giacomo Barozzi da Vignoli (Le Bas 1815), and was probably erected by the governor of the Sandomierz region between 1627 and 1644 (Mossakowski 2002, pp. 23–55; Lasek 2008, pp. 143–45, 147; Miłobędzki 1980, pp. 207–9). The fortification must have been constructed under the direction of Wawrzyniec Senes. It had a regular pentagonal plan, within which the palace building was inscribed. The building had a gate tower along its axis and an elliptical courtyard (Figure 14b). The castle in Łańcut represents a style similar to the one described above. It was built on a U-like plan between 1610 and 1620 and had four pentagonal alcove towers in its corners (Miłobędzki 1980, pp. 173–74, 349). The structure was subjected to a profound conversion in the period between 1629 and 1641. It was designed by Maciej Trapola and was funded by Stanisław Lubomirski. The building was surrounded by a pentagonal rise of bastion fortifications and was accessible through a west-facing gate. The above presented examples of Polish palazzo in fortezza structures date back to the late 16th century or the 1st half of the next century, and were built in a spirit of Mannerism for example Ćmielów, Danków, Krzepice and Pilica (Kajzer et al. 2001, pp. 148–51, 255–56, 382) (Figure 15).

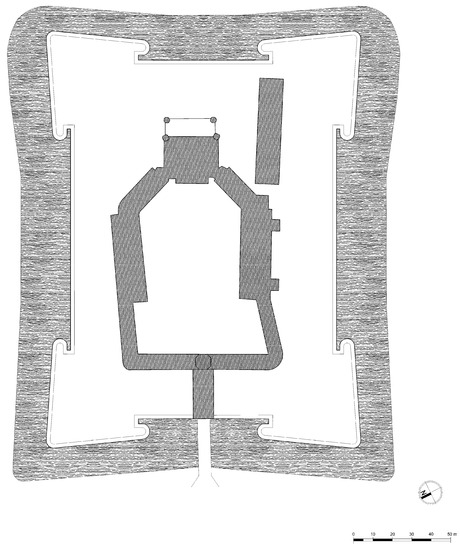

Figure 14.

(a) Nowy Wiśnicz: Lubomirscy’s residence—palace plan with fortifications; created by authors; (b) Ujazd: Krzyżtopór, Ossolińscy’s residence—palace plan with fortifications; created by authors.

Figure 15.

Łańcut: Lubomirscy‘s residence—palace plan with fortifications; created by authors.

Other structures of this type were erected as the capitals of Latifundia in the Kingdom of Poland’s Eastern Borderlands. They were mostly funded by wealthy magnate families, namely the Koniecpolskis, who built Brody between 1630 and 1635 (Bevz and Okonchenko 2015); the Zbaraskis, who built Zbaraż between 1627 and 1631 (Miłobędzki 1956, pp. 371–80; Miłobędzki 1980, pp. 198–99); the Sobieskis, who built Złoczów in 1634 (Miłobędzki 1980, p. 322); the Zasławskis, who built Dubno in about 1630 (Miłobędzki 1980, pp. 92, 322) (Figure 16); the Lubomirskis, who built Rzeszów in about 1667 (Kajzer et al. 2001, pp. 443–45); or the Radziwiłłs, who built their castles in Nieśwież between 1582 and 1604 (Bernatowicz 1998, pp. 9–17) (Figure 17), in Birża in the late 16th century, and then between 1636 and 1640 (Wasilewski 1988, pp. 263–72), in Ołka in about 1640 (Bernatowicz 2018), and in Biała Podlaska (Radziwiłłowska) in the 1630s (Łopaciński 1957, pp. 27–28; Baranowski 1967, pp. 39–57; Bernatowicz 2005, pp. 499–504) (Figure 18). The military features of the castles were discussed by Leszek Kajzer (Kajzer 2011, pp. 64–75), Stanisław Mossakowski, (Mossakowski 2005, pp. 137–62) and Piotr Lasek (Lasek 2008, pp. 141–47). The residence of Grand Hetman of the Polish Crown Stanisław Koniecpolski in Podhorce is an outstanding example of 17th-century palazzo in fortezza. It was probably built between 1637 and 1645. The palace was inscribed within one of the sides of a four-sided bastion rise (Bania 1981, pp. 102–3; Lasek 2008, pp. 143–44, 147) (Figure 19).

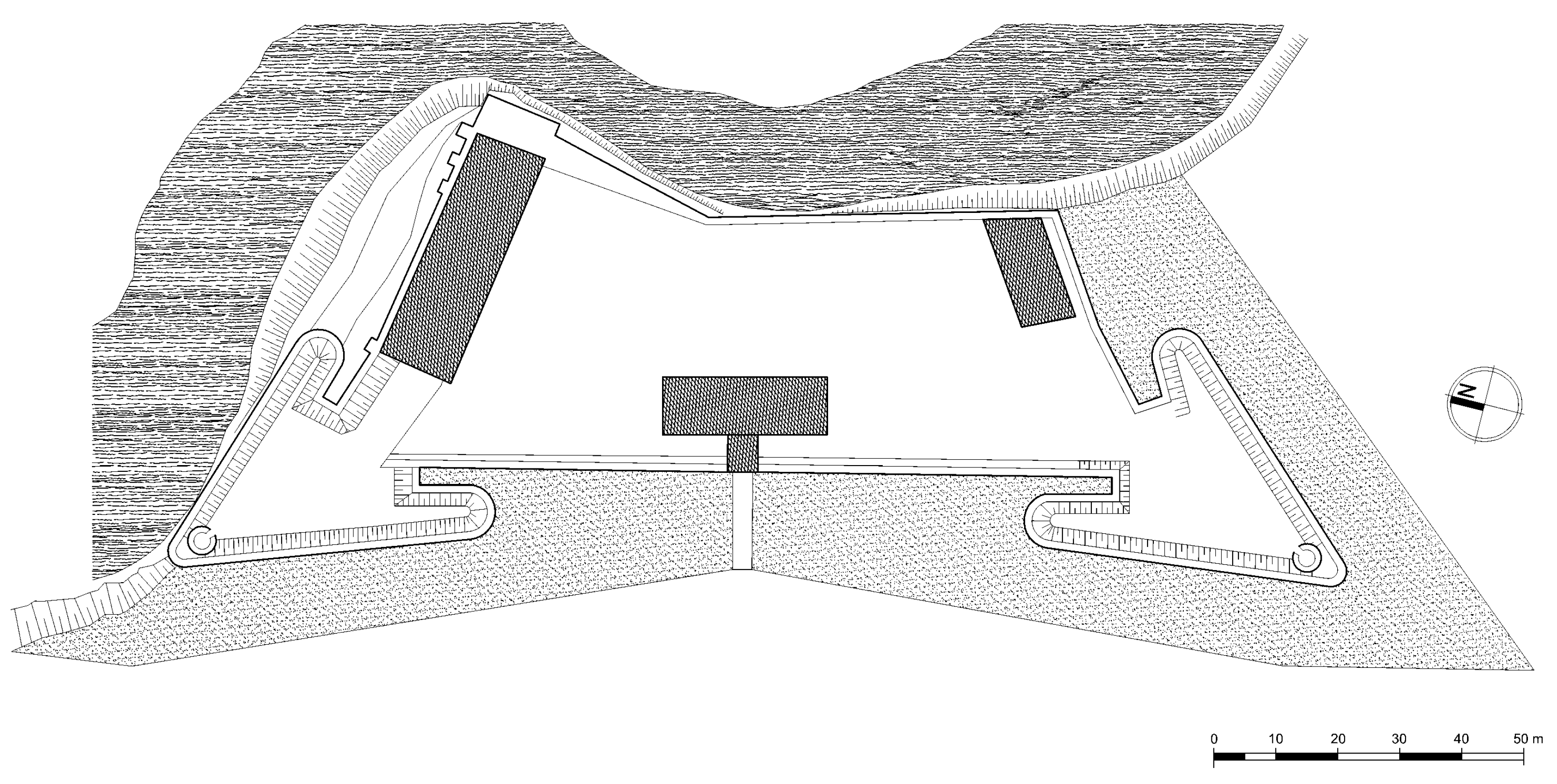

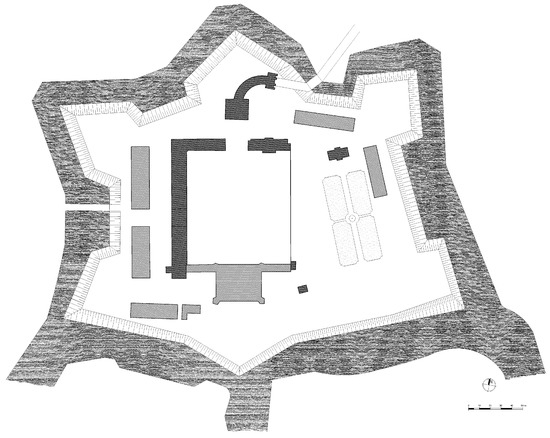

Figure 16.

Dubno: Lubomirscy’s residence—palace plan with fortifications; created by authors.

Figure 17.

Nieśwież: Radziwiłł’s residence—palace plan with fortifications; created by authors.

Figure 18.

Biała Podlaska: Radziwiłł’s residence—palace plan with fortifications; created by authors.

Figure 19.

Podhorce: Koniecpolscy’s residence—palace plan with fortifications; created by authors.

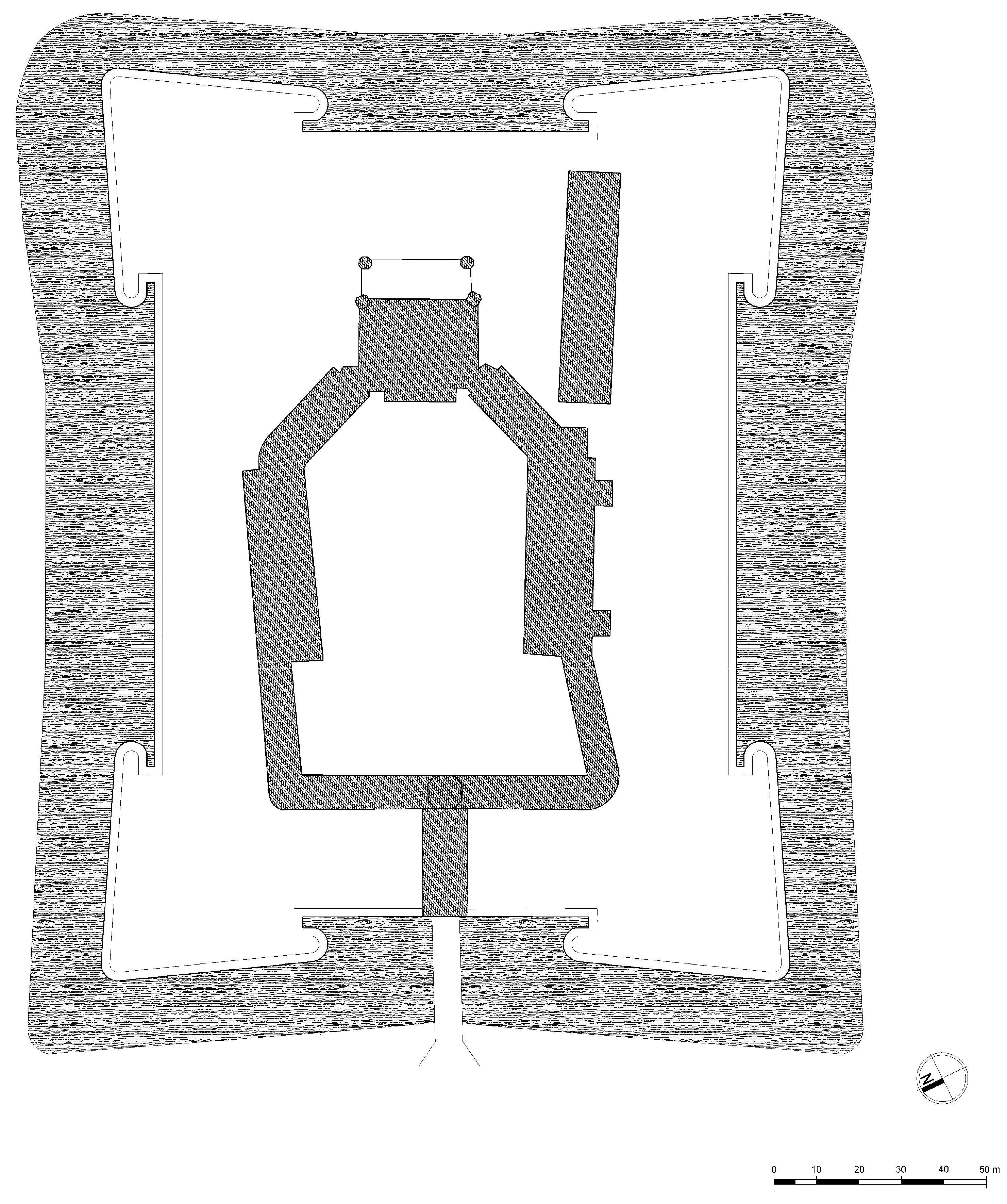

The arcades built around the inner courtyard are the second innovative element of Prószków castle. The conversion of the castle to a baroque style between 1677 and 1686 makes the reconstruction of the Renaissance decorations on the longer (south and north) elevations difficult. The only exception is the ground floor, where the plan of the arcades was identified during the research work. On the west elevation, there was a logia, which consisted of three arcades and which was supported by marble columns, semicolumns, and masonry pillars (Figure 20a). A similar solution might have been adopted to the non-retained parts of the castle. Therefore, the castle could be considered as a complex with a form and detail that were equal to Duke Jerzy II’s residence in Brzeg from the years 1544–1560. In Brzeg, Jakub Parr, while adapting the medieval assumptions, introduced cloisters around the trapezoidal courtyard, the decorations of which were carved in sandstone (Kozakiewicz and Kozakiewicz 1976, pp. 144–49; Zlat 2010, pp. 167–70) (Figure 20b). A similar solution was adopted to the courtyard of Niemodlin castle, which was subjected to alterations between 1589 and 1619, and which was funded by the Puckners family (Kajzer et al. 2001, pp. 113–16, 323–25). When analyzing the Renaissance residences in Silesia, it can be noted that such a way of shaping the inner elevations must have been very popular. It can not only be encountered in palaces or mansions, e.g., in Siestrzechowice (1592–94) (Legendziewicz 2019, pp. 17–29) or Żyrowa (1631–44) (Legendziewicz and Marcinów 2020) and in municipal buildings such as the Alderman’s Office in Głuchołazy, dated to the early 17th century (Legendziewicz 2010).

Figure 20.

(a) Prószków castle: courtyard, loggia; photo by the authors; (b) Brzeg castle: courtyard, open gallery; photo by the authors.

Arcaded courtyards first appeared in Poland with the arrival of Italian architects, who were brought in by King Sigismund I the Old in order to convert the Wawel castle between 1502 and 1536 (Zlat 2010, pp. 15–26). They were further adopted to many royal residences (e.g., in Niepołomice between 1506 and 1550) (Kozakiewicz and Kozakiewicz 1976, pp. 127–29; Zlat 2010, pp. 109–10) or magnate residences (e.g., in Baranów Sandomierski between 1591 and 1606) (Żabicki 2013, pp. 232–33). This trend in Polish architecture was followed until the middle of the 17th century (Kajzer et al. 2001, pp. 325–26). It also influenced architecture in Pomeranian Duchy, especially the residence of Griffin Dynasty (Gołębiewski 2020).

The conducted research enabled the original Renaissance form of the palazzo in fortezza in Prószków, which was created in the years 1563–1571, to be recognized. The precursor construction of the seat of the Prószkowski family is therefore one of the oldest examples of this type of palazzo in fortezza in the Czech Republic, Silesia, and present-day Poland. Unfortunately, knowledge concerning modern residences in Silesia does not enable the trend to be analyzed on a wider scale. Apart from the above mentioned examples—i.e., the palace in Siestrzechowice (Legendziewicz 2019, pp. 17–29) or the palace in Żyrowa, which was built at the slightly later time between 1631 and 1644 (Legendziewicz and Marcinów2020)—it is difficult to highlight other structures of a similar form or program that might allude so strongly to the Italian model. The topic is illustrated slightly differently with examples of palaces that were built in Poland, in which the application of the examined solutions was the domain of magnate families. The combination of residential and military architecture, due to the risk of Cossack, Tatar or Turkish invasions, was mainly applied to Poland’s Eastern Borderlands.

The introduction of arcaded courtyards and loggias to modern residential structures was typical for Renaissance or Mannerist architecture in Silesia and Poland. The non-application of such a solution to the residences of magnates in the 17th century is probably due to stylistic and climatic reasons, especially in the Eastern Borderlands.

The analysis of the Renaissance architecture of the Prószków castle seems to confirm the contribution of an Italian architect and Italian craftsmen during its implementation. This can be seen in the very rich sgraffito décor and in the unusual plan of the building, which refers to the patterns from the Apennine Peninsula. The Gothicizing stone detail applied to the window and door frames indicates that local stonemasons were also involved. This fact, however, has no impact on the opinion that Prószków castle is Silesia’s and Poland’s avant-garde, and that it is in many aspects almost a pioneering structure. It is probably due to its too innovative solutions that it did not find followers in Silesia. Therefore, the opinion of Chrzanowski and Kornecki that this castle is one of the best-preserved examples of Silesian palace architecture with a rich form and program, which was unfortunately almost forgotten or treated marginally with regards to Poland’s Renaissance art, remains accurate (Chrzanowski and Koniecki 1974, pp. 154–58).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.L. and A.M.; methodology, A.L., A.M.; formal analysis A.L. and A.M.; investigation and resources A.L. and A.M.; writing, reviewing, and editing, A.L. and A.M. Both authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

Figure 3 is used with permission of Österreichische Nationalbibliothek in Vienna.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Archival Sources

BN (Biblioteka Narodowa). 3 Plans militaires et fortifications anciennes. 1r Cahier, sygn WAF.44 (R.4575-4621).Legendziewicz, Andrzej. 2010. Wyniki badań architektonicznych oraz wnioski konserwatorskie do remontu części południowego skrzydła dawnego Wójtostwa w Głuchołazach. Wrocław: Typescript in Opolskie Regional Monument’’s Protection Office.ÖNb (Österreichische Nationalbibliothek). Proskovia castle, view from the southeast approximately 1735. by Friedrich B. Werner prepared the lithography Martin Engelbrecht, signature: KAR051249.Skarbek, Jerzy. 2009. Badania stratygraficzne elewacji wraz zdetalem architektonicznym zamku w Prószkowie przy ul. Zamkowej 8. Opole, Brzeg: Typesript in Opolskie Regional Monument’’s Protection Office.Wanat, Piotr. 2010. Dokumentacja konserwatorska. program prac konserwatorskich elementówwystroju elewacji i wnętrz zamku w Prószkowie. Opole, Wrocław: Typesript in Opolskie Regional Monument’’s Protection Office.Published Suorces

- Bania, Zbigniew. 1981. Pałac w Podhorcach. Rocznik Historii Sztuki 13: 97–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranowski, Jerzy. 1967. Pałac w Białej Podlaskiej. Próba rekonstrukcji stanu z XVII w. Biuletyn Historii Sztuki 29: 39–57. [Google Scholar]

- Bernatowicz, Tadeusz. 1998. “Monumenta variis Radivillorum”. Wyposażenie zamku nieświeskiego w świetle źródeł archiwalnych. Część I: XVI-XVII wieku. Poznań: Bogucki Wydawnictwo Naukowe. [Google Scholar]

- Bernatowicz, Tadeusz. 2005. Niezrealizowana „królewska” rezydencja w Białej Podlaskiej. In Artyści włoscy w Polsce XV–XVIII w. Edited by Renata Sulewska and Michał Wardzyński. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo DIG, pp. 499–512. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/33781156 (accessed on 14 March 2020).

- Bernatowicz, Tadeusz. 2018. Fanchonbourg i Na Turczynie. Kształtowanie się zespołu rezydencjonalnego wokół zamku Ołyckiego w XVIII w. w świetle nieznanych planów. In Oликa тa Paдзивiлли в icтopiї Укpaїни, Пoльщi й Бiлopyci. Edited by Лapиca Aнaтoлiївнa Kapлiнa Oкcaнa Mикoлaївнa and Швaб Aнaтoлiй Гeopriйoвич. Лyцьк: Beжa-Дpyк, pp. 88–99. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/38466688 (accessed on 14 March 2020).

- Bevz, Mykoła, and Olga Okonchenko. 2015. Zamek w Brodach: Fazy rozwojowe fortyfikacji. Budownictwo i Architektura 14: 5–18. Available online: https://docplayer.pl/69139747-Zamek-w-brodach-fazy-rozwojowe-fortyfikacji.html (accessed on 14 March 2020). [CrossRef]

- Bussagli, Marco. 2018. Italians Renaissance Architecture. Paris: Konemann. [Google Scholar]

- Chrzanowski, Tadeusz. 1965. Architektura zamków i dworów z XVI i XVII wieku na terenie województwa opolskiego. Biuletyn Historii Sztuki 27: 277–84. [Google Scholar]

- Chrzanowski, Tadeusz, and Marian Koniecki. 1974. Sztuka Śląska Opolskiego. Kraków: Wydawnictwo Literackie. [Google Scholar]

- Chrzanowski, Tadeusz, and Marian Kornecki. 1968. Katalog Zabytków Sztuki w Polsce, woj. Opolskie, powiat i miasto Opole. part 11. VII vols. Warszawa: Instytut Sztuki PAN. [Google Scholar]

- Eysymontt, Rafał, and Mateusz Goliński. 2009. Atlas Historyczny Miast Polskich. Śląsk vol. IV, Legnica part 9. Wrocław: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Wrocławskiego. [Google Scholar]

- Frommel, Christopher. 2007. Architecture of the Italian Renaissance. London: Thames & Hudson Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Gołębiewski, Jakub Ignacy. 2020. The Influence of Political Factors on the Architecture of Ducal Castles Owned by the Griffin Dynasty. Arts 9: 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerquin, Bohdan. 1984. Zamki w Polsce. Warszawa: Arkady. [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann, Maximilian. 1893. Die evangelische Gemeinde Proskau. Festschrift anlässlich des 100 jährigen Bestehens der Gemeinde. Oppeln: Druck von Joseph Wolff. [Google Scholar]

- Heinrich, Erhard, and Andrzej Pawełczyk. 2000. Zarys dziejów Prószkowa. Prószków: Parafia p.w. Św. Jerzego w Prószkowie. [Google Scholar]

- Heyne, Johann. 1860. Dokumentirte Geschichte des Bisthums und Hochstiftes Breslau: Aus Urkunden. Altenstücken, älteren Chronisten und neueren Geschichtschreibern. vol. I, Breslau: Verlag von Wilh. Gottl. Korn. [Google Scholar]

- Jagiełło-Kołaczyk, Marzanna. 2003. Sgraffita na Śląsku 1540–650. Wrocław: Oficyna Wydawnicza Politechniki Wrocławskiej. [Google Scholar]

- Kajzer, Leszek. 2011. Z problematyki badań założeń typu palazzo in fortezza w Polsce. In Architektura znaczeń. Studia ofiarowane prof. Zbigniewowi Bani w 65. rocznicę urodzin i w 40-lecie pracy dydaktycznej. Edited by Anna Sylwia Czyż, Janusz Nowiński and Marta Wiraszka. Warszawa: Instytut Historii Sztuki UKSW, pp. 64–75. Available online: http://www.ihs.uksw.edu.pl/sites/default/files/architektura_znaczen/ksiega_zbigniew_bania_10.pdf (accessed on 14 March 2020).

- Kajzer, Leszek, Stanisław Kołodziejski, and Jan Salm. 2001. Leksykon zamków Polsce. Warszawa: Arkady. [Google Scholar]

- Kalinowski, Konstanty. 1974. Architektura barokowa na Śląsku w drugiej połowie XVII wieku. Wrocław-Warszawa-Kraków-Gdańsk: Ossolineum. [Google Scholar]

- Kalinowski, Konstanty. 1977. Architektura doby baroku na Śląsku. Warszawa: Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe. [Google Scholar]

- Königer, Ernst. 1938. Kunst in Oberschlesien. Breslau: Verlag Priebatschs Buchhandlung. [Google Scholar]

- Kozakiewicz, Helena, and Stefan Kozakiewicz. 1976. Renesans w Polsce. Warszawa: Arkady. [Google Scholar]

- Lakwa, Klaudia, and Henryk Lakwa. 2010. Prószków—miasteczko z nutą nostalgii. Prószków: Wydawnictwo MS. [Google Scholar]

- Lasek, Piotr. 2008. Realna wartość obronna założeń w typie palazzo in fortezza z terenów Rzeczpospolitej w świetle zasad sztuki fortyfikacyjnej XVII wieku. Zeszyty Archeologiczne i Humanistyczne Warszawskie, voI. 1. Podhorce i Wilanów. Interdyscyplinarne badania założeń rezydencjonalnych. pp. 141–47. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/6579928 (accessed on 14 March 2020).

- Le Bas, Hippolyte. 1815. Oeuvres completes de Jacques Barozzi de Vignole 1507–73; François Debret, 1777–850. Paris: P. Didot l’aîné. Available online: https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/100912623 (accessed on 14 March 2020).

- Legendziewicz, Andrzej. 2019. Architectural transformations to the Siestrzechowice palace from the 16 th century to the end of the 20 th century. Wiadomości Konserwatorskie–Journal of Heritage Conservation 57: 17–29. Available online: https://repozytorium.biblos.pk.edu.pl/resources/41975 (accessed on 15 March 2020). [CrossRef]

- Legendziewicz, Andrzej, and Aleksandra Marcinów. 2020. Palace at Żyrowa. Transformations from the 15th to the early 20th centuries. Architecture Civil Engineering Environment 13: 41–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotz, Wolfgang. 1977. Studies in Italian Renaissance Architecture. Cambridge and London: The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lutsch, Hans. 1894. Verzeichnis der Kunstdenkmäler der Provinz Schlesien. Vol. IV. Der Reg.-Bezirk Oppeln. Breslau: Verlag von Wilh. Gottl. Korn. [Google Scholar]

- Łopaciński, Euzebiusz. 1957. Zamek w Białej Podlaskiej. Materiały archiwalne. Biuletyn Historii Sztuki 19: 27–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciąga, Mirosław. 1981. Obwarowania podzamcza w Baranowie Sandomierskim na podstawie inwentarza zamku. Kwartalnik Architektury i Urbanistyki: Teoria i historia 26: 159–73. [Google Scholar]

- Malý, Jakub, and Tomáš Masaryk, eds. 1908. Ottův slovník naučný. Díl 27: Vůz–Żyżkowski. Praha: J. Otto. [Google Scholar]

- Miłobędzki, Adam. 1956. Tajemnica zamku w Zbarażu. Kwartalnik Architektury i Urbanistyki 1: 371–80. [Google Scholar]

- Miłobędzki, Adam. 1980. Architektura Polska XVII Wieku. vol. 1, Warszawa: PWN. [Google Scholar]

- Mosca, Giuliana. 2018. “Un palazzo fatto in modo di fortezza”. II castello di Alviano tra XV e XVI secolo. In “IMPAZIENTE DELLA QUIETE”. Bartolomeo d’Alviano, un condottiero nell’Italia del Rinascimento (1455–515). Edited by Erminia Irace. Bologna: Il Mulino, pp. 181–97. [Google Scholar]

- Mossakowski, Stanisław. 2002. Orbis Polonus: Studia z Historii Sztuki XVII-XVIII wieku. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo DiG. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mossakowski, Stanisław. 2005. I “Palazzi in fortezza” all’italiana nella Polonia del ‘600. Barocco. Storia Letteratura Arte. Numero Speciale 1: 137–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilch, Józef. 2004. Leksykon zabytków architektury Dolnego Śląska. Warszawa: Arkady. [Google Scholar]

- Pilch, Józef. 2006. Leksykon zabytków architektury Górnego Śląska. Warszawa: Arkady. [Google Scholar]

- Settegast, Hermann. 1856. Der Betrieb der Landwirthschaft in Proskau und die höhere landwirthschaftliche Lehranstalt daselbst. Berlin: Verlag von Gustaw Bosselmann. [Google Scholar]

- Vlček, Pavel. 1998. Encyklopedie českých zámků. Praha: Libri. [Google Scholar]

- Wasilewski, Tadeusz. 1988. Budowa zamku i rezydencji Radziwiłłów w Birżach w latach 1586–654. In Podług nieba i zwyczaju polskiego. Studia z historii architektury, sztuki i kultury ofiarowane Adamowi Miłobędzkiemu. Edited by Zbigniew Bania. Warszawa: PWN, pp. 263–72. [Google Scholar]

- Wąs, Gabriela. 2007. Dzieje Śląska od 1526 do 1806 roku. In Historia Śląska. Edited by Marek Czapliński. Wrocław: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Wrocławskiego, pp. 122–275. Available online: https://docer.pl/doc/n51xs (accessed on 23 March 2020).

- Wutke, Konrad, Erich Randt, and Hans Bellée. 1923. Codex diplomaticus Silesiae, Regesten zur Schlesischen Geschichte 1334–1337. XXIX vols. Breslau: Ferdinand Hirt. [Google Scholar]

- Zlat, Mieczysław. 2010. Sztuka polska. Tom 3. Renesans i manieryzm. Warszawa: Arkady. [Google Scholar]

- Żabicki, Jacek. 2013. Leksykon zabytków architektury Lubelszczyzny i Podkarpacia. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Arkady. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).