Abstract

Unsafe behavior continues to be one of the leading causes of injuries and fatalities in the construction sector, despite the implementation of extensive safety programs and training. This enduring challenge suggests that deeper psychological and family-related factors influencing workers’ behavior remain underexplored. Grounded in Spillover Theory and the Conservation of Resources (COR) Theory, this study investigates how family–work balance influences unsafe behavior among new-generation construction workers in Turkey, while examining the mediating role of hardiness and the moderating effect of mastery climate. Using a cross-sectional survey design with data collected from 692 construction workers across major Turkish cities, the study employs the Hayes PROCESS macro to test direct, indirect, and conditional effects. The findings reveal that family–work balance and hardiness both negatively predict unsafe behavior, while family–work balance positively relates to hardiness. Moreover, hardiness partially mediates the link between family–work balance and unsafe behavior, accounting for approximately two-thirds of the total effect. Additionally, a mastery climate strengthens these negative associations, demonstrating that supportive and learning-oriented environments amplify the safety-enhancing effects of both family–work balance and hardiness. These results extend the theoretical understanding of how personal and contextual resources interact to influence safety outcomes, offering actionable insights for construction firms to promote family-supportive policies, resilience-building initiatives, and mastery-oriented climates that jointly foster safer work practices.

1. Introduction

Safety in the construction industry remains a critical and persistent challenge worldwide, with occupational injury and fatality rates significantly higher than in other sectors [1,2]. Although construction employs only 7% of the global workforce, it accounts for approximately 30–40% of fatal occupational injuries [3,4]. In 2023, the United States alone recorded 1075 construction-related deaths, representing about 20% of all workplace fatalities [5,6]. Comparable figures have been reported in South Korea and China [7,8]. In developing economies such as Türkiye, these risks are even more pronounced due to fragmented safety systems, temporary project structures, and the limited enforcement of occupational health regulations, creating persistent vulnerabilities among frontline workers [9].

Despite extensive safety training programs and compliance systems, unsafe behavior continues to be one of the primary causes of construction accidents. This paradox underscores that knowledge and regulation alone are insufficient to ensure safety performance unless the underlying human and psychological mechanisms are also understood [8,9,10,11]. Unsafe behavior encompasses risk-taking, rule violations, and the neglect of protective equipment, all of which elevate accident risk [12,13]. Traditional safety efforts that emphasize rigid rule compliance are often inadequate in the face of the industry’s dynamic and unpredictable nature, which exposes workers to conditions not covered by formal safety rules [14,15].

While previous studies have explored factors such as leadership [1,9], psychological contract safety [8,16], violent behavior [17], and safety culture [18], research has largely overlooked how personal and family-related factors influence safety outcomes. Construction workers frequently operate under unstable schedules and excessive work hours, which disrupt family life and lead to stress and fatigue [19]. These pressures create conflicts between work and family roles, undermining concentration and decision-making, and may indirectly trigger unsafe behaviors on construction sites [20,21].

Family–work balance (FWB)—the individual’s ability to meet both work and family obligations effectively [22]—has emerged as a significant predictor of psychological well-being and performance. When workers experience balance between work and family domains, they preserve energy, recover from fatigue, and maintain emotional stability, which together reduce the likelihood of engaging in unsafe actions [23,24]. Previous research confirms that family–work balance enhances employee satisfaction and positive job-related attitudes [25,26]. However, limited empirical evidence exists concerning how FWB influences unsafe behavior in the construction industry, a gap this study seeks to address [21].

Although family–work balance has been widely recognized as a critical element of worker well-being in construction, existing studies demonstrate that the industry’s demanding, unstable, and highly stressful environment makes achieving such balance exceptionally difficult [19]. Empirical research shows that construction workers frequently experience long working hours, heavy workloads, and project pressures that interfere with personal life, resulting in diminished well-being and impaired performance [27,28]. Yet, despite the consistent acknowledgement of work–life challenges, construction safety scholarship has mainly emphasized work–family conflict rather than the enabling role of family–work balance in improving safety outcomes. Even recent analyses reveal that while work–family conflict increases exhaustion and contributes to unsafe behavior, the potential of FWB to reduce such risks—particularly among new-generation workers—remains underexplored [21,29]. Moreover, reviews in construction management highlight the absence of research integrating FWB with safety behavior and accident prevention, calling for studies that investigate how family-related resources can enhance workers’ psychological capacity and safety performance [19]. Addressing this gap is essential given the sector’s labor shortages, retention problems, and high turnover, which make supportive work-life practices increasingly important for sustaining a safe and stable workforce.

To explain the underlying psychological mechanism of this relationship, the present study introduces hardiness as a key personal trait. Hardiness reflects a sense of commitment, control, and challenge in facing stressful events and enables individuals to remain focused and resilient under demanding conditions [30,31]. Given the physically strenuous and uncertain environment of construction work, hardiness serves as a coping resource that transforms stress into productive engagement, reducing the probability of unsafe responses to job pressure [32,33,34].

This study is theoretically anchored in the Spillover Theory and the Conservation of Resources (COR) Theory. Spillover Theory explains how positive emotions and resources from one life domain, such as family, transfer to another, such as work, thereby enhancing workplace functioning [35,36,37]. COR Theory complements this perspective by emphasizing that individuals strive to acquire, maintain, and protect valuable psychological resources to manage environmental demands [38,39]. Together, these theories provide a robust framework for explaining how balanced family and work roles contribute to safety behavior through resource conservation and transfer [40,41]. Family–work balance enhances workers’ psychological hardiness, which in turn reduces the risk of unsafe conduct in the workplace.

Beyond personal attributes, organizational context can further strengthen or weaken these relationships. A mastery climate, characterized by shared values that emphasize learning, self-improvement, and cooperation, has been shown to foster positive safety outcomes [42,43]. In firms that promote mastery-oriented environments, the beneficial effects of family–work balance and hardiness on reducing unsafe behavior are expected to intensify, as employees perceive greater support and opportunities for skill development that reinforce their motivation to act safely.

Drawing from these theoretical perspectives, this study develops an integrated model that explores the direct influence of family–work balance on unsafe behavior, the mediating role of hardiness, and the moderating role of mastery climate among new-generation construction workers in Türkiye. This focus is timely, as younger employees entering the workforce often face significant pressure to balance family responsibilities with the demands of an increasingly complex and high-risk work environment. Accordingly, this study provides a multidimensional explanation that links individual well-being, psychological resilience, and contextual support mechanisms to construction safety behavior.

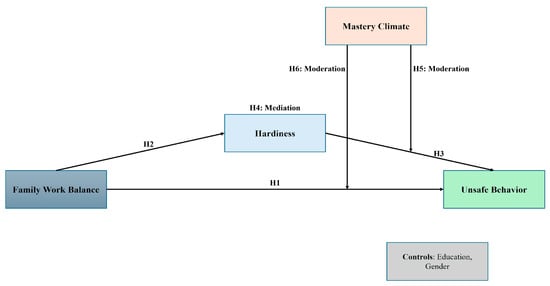

This research advances the literature in three key ways. First, building on Spillover Theory, it elucidates how positive family-related experiences and emotional resources are transferred into safer workplace behaviors. Second, grounded in COR Theory, it identifies hardiness as a pivotal psychological resource that channels the benefits of family–work balance into reduced unsafe acts. Third, it introduces mastery climate as a contextual moderator that enhances this resource-gain process, providing new insights into how organizational environments strengthen the relationship between individual well-being and safety performance. Collectively, these contributions integrate family–work interface research with occupational health psychology and safety management, offering both theoretical enrichment and practical guidance for developing holistic safety strategies in construction. Figure 1 illustrates the proposed conceptual framework of the study.

Figure 1.

Research model.

Based on the theoretical reasoning above, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H1.

Family–work balance is negatively related to construction workers’ unsafe behavior.

H2.

Family–work balance is positively related to hardiness.

H3.

Hardiness is negatively related to unsafe behavior.

H4.

Hardiness mediates the relationship between family–work balance and unsafe behavior.

H5.

For construction firms whose workers experience a high mastery climate, the impact of family–work balance in reducing unsafe behavior is more potent.

H6.

For construction firms whose workers experience a high mastery climate, the impact of hardiness in reducing unsafe behavior is more potent.

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Spillover Theory

The spillover theory provides a robust conceptual foundation for explaining how family–work balance influences unsafe behavior in the construction context. The theory posits that individuals’ emotions, attitudes, and behaviors generated in one life domain—either work or family—can affect experiences in the other [44]. The central assumption of spillover theory is that work and non-work domains are interdependent, such that positive or negative experiences in one domain may extend to the other [35]. In essence, employees do not function in isolated spheres; rather, cognitive and emotional experiences from home are carried into the workplace and vice versa [45].

According to this perspective, family–work balance serves as a conduit for positive spillover, transferring emotional stability, satisfaction, and energy from one domain to another, thereby improving overall performance and reducing maladaptive behaviors such as safety neglect [37,46]. Du et al. [47] demonstrated that individuals possess finite psychological resources—such as attention, energy, and emotional capacity—and that excessive demands in one role can deplete these resources, limiting effective functioning in other domains.

Spillover effects can be either positive or negative and often flow bidirectionally between family and work [48]. Positive spillover refers to the transfer of beneficial values, competencies, and emotional states that enrich the receiving domain [49]. For example, supportive family interactions may generate emotional stability and resilience that extend into the workplace, encouraging safer behavior under stressful conditions. Conversely, negative spillover arises when stress or conflict in one domain spills over into the other, diminishing psychological resources and increasing risk-prone behaviors [50,51].

Although the spillover theory has been widely applied to examine outcomes such as well-being, job satisfaction, and health [52,53,54], its use in construction safety research remains limited. This gap is notable, given that the theory’s acknowledgment of resource transmission between family and work makes it highly relevant for explaining why family–work balance may influence safety compliance and unsafe actions. In the context of construction, where job demands and fatigue are prevalent, understanding how positive resource flow from family life buffers the effects of workplace stress can provide valuable insights into improving workers’ safety behavior.

2.2. Conservation of Resources Theory (COR)

The COR theory offers a complementary explanation to the spillover framework by elucidating how individuals manage and preserve valuable psychological and social resources under stress. It is one of the most comprehensive and frequently used theories in organizational behavior research [39]. The core tenet of COR theory is that individuals strive to obtain, retain, and protect resources—such as energy, optimism, or social support—and that resource loss or the threat of loss is a significant source of stress [55]. In high-risk occupations like construction, the depletion of psychological resources can directly compromise decision-making and self-regulation, increasing the likelihood of unsafe conduct [8,9].

Moreover, individuals with fewer resources are more vulnerable to further losses, creating a downward spiral that intensifies stress and undermines performance [56]. Conversely, the acquisition or replenishment of resources can trigger a positive gain cycle that enhances well-being and safety. Family–work balance represents one such gain mechanism, as it enables workers to accumulate emotional and cognitive resources that protect against the strain of hazardous working conditions [57]. This aligns with arguments that when workers successfully manage both family and work roles, they conserve psychological resources that help prevent fatigue, distraction, and risk-taking—all central antecedents of unsafe behavior in construction settings.

Within this theoretical framework, the inclusion of mastery climate as a contextual factor aligns with COR’s emphasis on resource gain and reinforcement. A mastery climate—characterized by its focus on learning, development, cooperation, and recognition of effort—creates an empowering environment that fosters psychological resilience and resource renewal [42,43]. Such an environment not only replenishes depleted resources but also strengthens employees’ capacity to cope with work stressors, thereby enhancing the positive effects of family–work balance on safe behavior. This theoretical link supports the expectation that contextual factors may amplify or weaken the resource-based processes linking family–work balance, hardiness, and unsafe behavior.

Accordingly, this study integrates Spillover Theory and COR Theory to explain how and under what conditions family–work balance reduces unsafe behavior among construction workers. The two theories together capture both the transfer of positive affect and the preservation of psychological resources, offering a comprehensive explanation for the pathways through which individual and contextual factors jointly influence safety behavior in the construction industry.

3. Hypotheses Development

3.1. Family Work Balance and Unsafe Behavior

Unsafe behavior remains a major cause of accidents in the construction sector, encompassing intentional or unintentional violations of safety procedures, neglect of protective equipment, and deviations from operational protocols that elevate accident risk [58,59]. Despite continuous advancements in safety systems and training, unsafe acts persist across construction sites, underscoring the need to understand the personal and psychosocial factors influencing workers’ decisions beyond traditional managerial controls [60,61,62]. Given the industry’s long working hours, mobile project structure, and irregular schedules, construction workers frequently struggle to balance work and family roles, which may contribute to lapses in concentration and reduced adherence to safety practices.

Existing research indicates that inadequate family–work balance can heighten emotional exhaustion, impair attention, and undermine safety participation [63,64,65,66,67]. In contrast, workers who experience harmony between family and work domains tend to preserve psychological stability and regulate their behavior more effectively during high-risk tasks. The positive affect and emotional resources associated with family–work balance are thus likely to enhance workers’ readiness to engage in safe behavior, whereas unresolved strain may intensify distraction and risk-taking tendencies. This pattern is consistent with the broader view that supportive family experiences help sustain cognitive control and reduce the likelihood of safety violations in demanding occupational settings.

Accordingly, when construction workers experience stronger family–work balance, they are expected to maintain greater focus, manage stress more effectively, and uphold safe conduct on-site. Therefore, it is hypothesized that:

H1.

Family work balance is negatively related to construction workers’ unsafe behavior.

3.2. Family Work Balance and Hardiness

Family–work balance is a significant contributor to employees’ psychological well-being, shaping their ability to manage work demands with stability and confidence [68]. Prior research links balanced family and work roles with greater work engagement, reduced emotional exhaustion, and strengthened resilience [69,70], suggesting that balance may create conditions conducive to the development of hardy attitudes. Hardiness—characterized by commitment, control, and viewing challenges as opportunities for growth—enables workers to cope effectively with stressors common in construction environments, including uncertainty, tight deadlines, and hazardous tasks [30,71]. When individuals experience balance across domains, they are more emotionally replenished and better equipped to interpret job-related difficulties as manageable rather than overwhelming.

Family–work balance also enhances role clarity, emotional stability, and a sense of personal control, all of which support the development of hardy traits [67,72,73]. Workers who feel able to meet both family and occupational expectations are less likely to experience emotional depletion and more likely to cultivate adaptive responses to pressure. Repeated experiences of successfully managing competing demands may reinforce workers’ confidence and perceived competence, strengthening the psychological foundations of hardiness.

In addition, family–work balance has been associated with the accumulation of positive psychological resources such as optimism, self-efficacy, and psychological capital [74,75,76], which contribute to sustained resilience. These resources can operate as a reinforcing cycle, helping workers maintain composure in challenging situations and supporting their ability to remain committed and in control. Accordingly, construction workers who achieve harmony between their family and work roles are more likely to exhibit high levels of hardiness.

Therefore, it is hypothesized that:

H2.

Family–work balance is positively related to hardiness.

3.3. Hardiness and Unsafe Behavior

Hardiness plays a critical role in determining how construction workers interpret and respond to stressful or high-risk site conditions. As a dispositional resource characterized by commitment, control, and challenge, hardiness equips individuals with the psychological stability needed to remain composed under pressure and to avoid maladaptive coping strategies [30,71]. Workers with high levels of hardiness tend to appraise demanding situations as manageable rather than threatening, enabling them to remain attentive, emotionally regulated, and focused on safe task execution. In contrast, individuals with low hardiness may experience heightened strain or loss of control, which can lead to impulsive decisions, reduced vigilance, or a tendency to bypass safety protocols under time pressure [31].

Empirical studies show that hardy individuals demonstrate stronger resilience, greater task engagement, and more consistent adherence to organizational expectations, including safety-related responsibilities [77]. By helping workers sustain concentration and regulate emotional responses, hardiness supports behaviors that prioritize risk awareness and compliance, thereby reducing the likelihood of errors or intentional violations. The commitment dimension of hardiness reinforces identification with organizational norms, promoting a sense of responsibility toward safe performance, while the control dimension strengthens workers’ confidence in their ability to influence outcomes, discouraging unnecessary risk-taking [78,79].

Furthermore, hardiness functions as a protective personal resource that helps workers maintain cognitive and emotional capacity even in fast-paced or unpredictable construction environments. This resource-preserving function reduces the exhaustion and attentional lapses that often precede unsafe behaviors, allowing individuals to uphold safety standards despite demanding work conditions. As a result, hardy employees are more likely to engage in self-regulated, proactive, and compliant safety behaviors.

Therefore, it is hypothesized that:

H3.

Hardiness is negatively related to unsafe behavior.

3.4. The Mediating Role of Hardiness

Construction work often exposes employees to persistent physical, psychological, and environmental stressors that can undermine their capacity to act safely. In such contexts, personality-based coping traits play an essential role in helping individuals regulate emotions and maintain adaptive functioning under pressure [80]. Hardiness—defined by control, commitment, and challenge—enables workers to remain engaged and to interpret difficulties as manageable rather than overwhelming [30,81]. By sustaining emotional stability, frustration tolerance, and cognitive flexibility, hardiness helps individuals navigate demanding situations without resorting to unsafe shortcuts or error-prone decisions [82,83].

Hardiness provides a psychological pathway through which family–work balance influences employees’ safety behavior. When individuals maintain balance across family and work roles, they experience greater emotional stability and resource availability, which enhance their capacity to cope with job demands. This strengthened coping capacity reinforces the hardy characteristics needed to remain attentive and disciplined in hazardous environments. Conversely, when family and work demands conflict, workers are more vulnerable to strain and distraction that may undermine their ability to uphold safe practices [37,50,52]. As a result, hardiness operates as the mechanism that translates balanced role experiences into safer behavioral outcomes.

Prior empirical evidence supports the mediating role of positive psychological resources in shaping safety-related behaviors. Resilience has been shown to buffer the effects of work–family strain on safety performance [84], while individuals characterized by high levels of hardiness exhibit lower engagement in counterproductive or unsafe actions [85]. Similarly, resilient workers demonstrate reduced stress and stronger adherence to safety requirements [86]. These findings collectively indicate that resourceful individuals are better able to maintain concentration and self-regulation, which are essential for preventing unsafe acts.

Within the resource-based logic of COR Theory, family–work balance provides the foundational pool of psychological resources that hardiness then channels toward safety-enhancing behavior. Workers with higher hardiness conserve energy, regulate emotions, and sustain motivation to perform safely even when exposed to intense occupational pressure [81]. Thus, when family–work balance strengthens hardiness, it indirectly reduces unsafe behavior by enabling workers to maintain resilience and focus in demanding environments.

Therefore, it is hypothesized that:

H4.

Hardiness mediates the relationship between family–work balance and unsafe behavior.

3.5. The Moderating Role of Mastery Climate

A mastery climate reflects an organizational environment that prioritizes learning, personal growth, and continuous improvement rather than competition or performance comparison [87]. In such climates, employees are encouraged to enhance their skills, cooperate with colleagues, and pursue challenging goals, which collectively promote constructive work behavior and reduce tendencies to engage in counterproductive or unsafe actions [42,43]. Because safety performance in construction depends heavily on workers’ motivation, communication, and willingness to engage in ongoing learning, mastery-oriented settings provide a supportive context in which safety-enhancing behaviors are more likely to occur [73,88].

Within construction settings—where long hours, shifting work conditions, and uncertainty are common—a mastery climate functions as a contextual resource that stabilizes workers’ psychological states and reduces the likelihood of lapses in safety compliance [8,89]. When organizations emphasize development, cooperation, and shared accountability, workers feel psychologically supported and more willing to identify risks, seek assistance, and discuss safety concerns openly [90,91]. These features create an environment that amplifies the beneficial effects of individual resources, such as those derived from family–work balance and hardiness, on safe behavior. Although previous studies acknowledge the importance of mastery-oriented environments, empirical evidence on how they interact with personal resources to influence safety behavior remains limited [92,93,94].

Building on the resource logic of COR Theory, mastery climate strengthens workers’ capacity to conserve, renew, and utilize psychological resources effectively. Workers who experience strong family–work balance may already possess greater emotional stability and energy, but the presence of a mastery climate provides the social reinforcement and collaborative support needed to translate these resources into safer behavioral choices. Consequently, a high mastery climate is expected to magnify the protective effect of family–work balance on unsafe behavior. Likewise, mastery-oriented environments enhance the effectiveness of hardiness by validating effort, promoting autonomous learning, and encouraging resilient responses under pressure [79,87]. In such settings, hardy workers can more readily apply their coping strengths to maintain disciplined and attentive safety behavior.

Accordingly, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H5.

For construction firms whose workers experience a high mastery climate, the impact of family–work balance in reducing unsafe behavior is more potent.

H6.

For construction firms whose workers experience a high mastery climate, the impact of hardiness in reducing unsafe behavior is more potent.

4. Methods

4.1. Sampling and Data Collection

The measures used in this study were adapted from validated scales widely applied in safety and organizational behavior research to ensure conceptual consistency and measurement reliability. To confirm suitability for the Turkish construction context, a pilot study was conducted following established practices in construction safety research [21,95]. All survey items were reviewed by a panel of six experts—three academics specializing in occupational safety and three senior construction professionals—who evaluated item clarity, translation accuracy, and contextual relevance. Based on their feedback, minor linguistic and formatting adjustments were made to enhance face validity and ensure that the questionnaire was comprehensible for field workers.

This study employed a quantitative, cross-sectional research design and targeted full-time construction employees working for firms registered under the Turkish Contractors Association in Ankara, Istanbul, and Izmir. These metropolitan regions represent Türkiye’s major construction hubs characterized by high project density and substantial workforce mobility, thus improving the representativeness of the sample [8,9]. A convenience sampling strategy was used, a widely accepted approach in construction safety studies due to the difficulty of accessing dispersed and dynamic project sites [96,97,98]. Although this method facilitated access and improved participation rates, its non-probabilistic nature is acknowledged as a limitation with respect to generalizability.

The target population consisted of new-generation construction workers aged 18–35, reflecting the group increasingly associated with evolving work–life expectations, higher technological familiarity, and distinct safety attitudes. This age range aligns with demographic classifications in recent construction labor studies identifying individuals under 35 as “young” or “new-generation” workers whose values, mobility patterns, and safety perceptions markedly differ from older cohorts [21,99]. International labor organizations similarly classify workers aged 15–35 as “young construction labor,” noting their early workforce entry and unique safety vulnerabilities [100]. In Türkiye, many construction employees begin site experience between 17 and 20 years of age, making the operational definition of 18–35 consistent with national employment patterns. To ensure adequate familiarity with safety protocols, inclusion criteria required participants to be full-time workers with at least three years of construction experience and who had worked across multiple project sites—reflecting common mobility trends in Turkish construction employment [19,101].

Data were collected using a two-wave survey design between January and February 2025 to reduce common method bias [102]. In the first wave (Time 1), participants completed measures of family–work balance and hardiness, while the second wave (Time 2), administered one month later, collected data on mastery climate and unsafe behavior. A one-month interval was adopted following methodological guidelines indicating that a 3–6 week separation effectively reduces consistency motifs, memory contamination, and inflated correlations while maintaining construct stability [102,103,104]. This time-lag design is widely applied in organizational behavior and safety research to strengthen temporal separation without causing substantial sample attrition [105,106,107]. Surveys were administered both electronically (via Google Forms) and physically during scheduled site visits. For on-site administration, questionnaires were sealed in envelopes and distributed directly to workers to ensure privacy and minimize social desirability bias. Participants were asked to respond based on their typical workplace experiences over the previous six months, a recall period commonly used in behavioral safety research to capture stable patterns of behavior while minimizing recall error.

All participants were provided with clear information regarding the voluntary nature of the study, confidentiality assurances, and anonymity of responses. They were explicitly informed that participation would not affect their employment status and that all data would be used solely for academic purposes, enhancing transparency and encouraging honest participation [108].

A total of 900 questionnaires were distributed across both waves. After eliminating incomplete or unmatched responses, 692 valid paired surveys were retained, resulting in a robust response rate of 76.88%. Each participant was assigned a unique identifier to ensure accurate matching between the two waves while maintaining confidentiality. As shown in Table 1, the demographic profile of the final sample mirrors the gender imbalance typical of the Turkish construction sector, with male workers comprising 86.99% of respondents. Most participants were aged 26–35 (59.4%) and had six or more years of experience (62.86%), demonstrating a cohort of younger yet experienced workers navigating both modern lifestyle demands and the enduring safety challenges of construction sites.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics.

4.2. Survey Instruments

Because Turkish is the official language of Türkiye, all measurement items were administered in Turkish using Brislin’s [109] back-translation procedure to ensure linguistic and conceptual equivalence between the original English scales and the translated version. Following this procedure, the scales were first translated into Turkish by two bilingual academic experts familiar with occupational safety research. A professional translator and a doctoral scholar specializing in English conducted the back-translation into English, ensuring the conceptual meaning and phrasing of the items were preserved. The two English versions were then compared to identify and reconcile discrepancies. No substantial inconsistencies were found, confirming that the final Turkish version retained the same meaning and clarity as the original scales. This process ensured the translated instrument’s cultural appropriateness, content validity, and semantic accuracy, consistent with established methodological standards for cross-cultural research [110].

Family–work balance was measured using five items adopted from Carlson et al. [111]. This scale assesses individuals’ ability to manage and fulfill their family and work responsibilities effectively. A sample item includes: “I can fulfill my job and family responsibilities at the same time.” Higher scores indicate greater perceived balance between family and work domains.

Hardiness was measured using 15 items developed by Bartone [112], which capture the three key dimensions of commitment, control, and challenge. A representative item is: “Changes in routine are interesting to me.” This scale has been extensively validated across occupational contexts and is recognized for its strong psychometric reliability in measuring psychological resilience and stress tolerance.

Mastery climate was assessed with six items adopted from Nerstad et al. [43], which reflect the degree to which an organization fosters learning, cooperation, and personal growth. A sample item is: “In my firm, one is encouraged to cooperate and exchange thoughts and ideas mutually.” This measure captures an organizational emphasis on effort, development, and continuous improvement—key factors relevant to workplace safety culture.

Unsafe behavior was measured using 12 items adapted from Neal and Griffin [12] and Tucker and Turner [113]. The items capture workers’ self-reported frequency of engaging in actions that violate established safety procedures. A sample item includes: “Sometimes I neglect safety procedures as the construction period is shortened.” Higher scores on this scale indicate greater engagement in unsafe acts, reflecting both intentional violations and unintentional risk-taking behaviors.

All scales were rated on a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). This standardized response format enhances comparability across constructs and facilitates statistical analyses. Each instrument was selected based on its theoretical relevance, prior validation, and demonstrated reliability in occupational safety and work–family interface studies.

4.3. Statistical Approach

Data analysis was performed using SPSS version 27.0 and AMOS version 24.0. Descriptive statistics, normality checks, and reliability analyses were conducted in SPSS to ensure data quality and consistency across variables [114]. AMOS was used to conduct Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) to assess the dimensionality and psychometric validity of the multi-item constructs. Convergent validity was evaluated through factor loadings, composite reliability (CR), and average variance extracted (AVE), while discriminant validity was confirmed when the square root of AVE exceeded the inter-construct correlations. Model fit was assessed using standard indices, including the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR), all of which met recommended thresholds [115].

To examine the hypothesized relationships, Hayes’ PROCESS macro was employed, as it allows simultaneous testing of direct, indirect (mediation), and moderating effects within a single analytical framework. Model 4 of the PROCESS macro was used to assess direct and mediating relationships, while Model 15 was used to evaluate the moderating effects of mastery climate. Bootstrapping with 5000 resamples was performed to generate bias-corrected confidence intervals for all indirect paths, ensuring robustness and reliability of results. Statistical significance was determined when the 95% confidence interval did not include zero [116].

This combination of CFA and conditional process analysis provided a rigorous and comprehensive statistical approach for testing the study’s conceptual model, allowing for the precise estimation of both the strength and direction of hypothesized effects.

5. Analysis Results and Discussion

5.1. Common Method Bias (CMB)

Given the potential for common method bias (CMB) in self-reported, survey-based studies, several procedural and statistical measures were applied to minimize its impact [102]. Procedurally, the independent and dependent variables were collected at different time points to reduce consistency artifacts. Additionally, the sequence of measurement items was randomized to avoid response patterns and speculative answering based on theoretical expectations [117].

Statistically, multiple diagnostic tests confirmed that CMB was not a significant issue. First, Harman’s single-factor test indicated that the first factor accounted for only 27.32% of the total variance, well below the 50% threshold, suggesting that no single latent factor dominated the variance. Second, using Lindell and Whitney’s [118] marker variable technique, a theoretically unrelated construct was included as a marker. The correlations between this marker variable and the main study constructs were less than 0.03, and adjusting for this factor did not alter the structural relationships, confirming the robustness of the results. Finally, the variance inflation factor (VIF) values for all constructs were below 3.3 [119,120], indicating the absence of multicollinearity or common variance issues. Together, these procedural and statistical approaches provide strong evidence that common method bias does not threaten the validity of the study’s findings.

5.2. Assessment of the Measurement Model

Before hypothesis testing, the dataset was evaluated for normality, reliability, and construct validity to ensure its suitability for subsequent analyses. The normality assessment confirmed that the absolute values of skewness (ranging from 0.306 to 1.276) and kurtosis (ranging from 0.031 to 2.937) fell within the acceptable thresholds for a normal distribution [121,122]. To further confirm multivariate normality, Mardia’s coefficient was examined and found to be within the recommended range, providing additional support that the data distribution was appropriate for structural modeling.

Reliability was evaluated through Cronbach’s alpha (α) and Composite Reliability (CR). Consistent with the recommended threshold of 0.70 [123], all α values ranged between 0.857 and 0.962, indicating strong internal consistency across constructs. The CR values also exceeded the 0.70 cut-off, further confirming the measurement stability and reliability of the scales employed in this study.

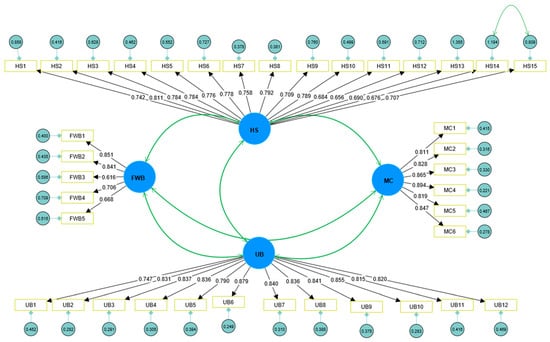

To examine validity, Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was performed, focusing on convergent and discriminant validity. Convergent validity was assessed through standardized factor loadings, composite reliability, and average variance extracted (AVE), with recommended thresholds of 0.60, 0.70, and 0.50, respectively [124]. The results (see Table 2 and Figure 2) indicate that all standardized loadings exceeded 0.60 (ranging from 0.655 to 0.879), CR values were between 0.858 and 0.963, and AVE values ranged between 0.551 and 0.713. These results demonstrate that each construct adequately captures the variance of its measurement indicators, satisfying the criteria for convergent validity [125].

Table 2.

Assessment of reliability and validity.

Figure 2.

Standardized factor loading results.

Discriminant validity was evaluated by comparing the square root of each construct’s AVE with the inter-construct correlations [125]. As shown in Table 3, the square root of AVE for family-work balance (0.745) exceeded its correlation with unsafe behavior (0.503), confirming that the constructs are empirically distinct [126]. All constructs exhibited the same pattern, providing strong evidence that no multicollinearity or conceptual overlap exists among the variables.

Table 3.

Correlation and discriminant validity.

Finally, the goodness-of-fit indices of the CFA model were within the recommended thresholds: χ2/df = 1.997, CFI = 0.937, TLI = 0.945, NFI = 0.937, IFI = 0.948, and RMSEA = 0.048. These results (see Table 4) collectively indicate that the measurement model exhibits excellent psychometric properties and provides a robust foundation for hypothesis testing [125,127,128].

Table 4.

Goodness-of-fit-index.

5.3. Hypothesis Testing for Direct and Mediation Analysis

After confirming the reliability and validity of the measurement model, Model 4 of Hayes’s [116] PROCESS macro (version 4.2) was applied to examine both the direct and mediating relationships among the study variables. The results summarized in Table 5 present a comprehensive overview of the direct and indirect effects, providing empirical support for the proposed model.

Table 5.

Test results for mediation analysis.

The regression findings reveal that family work balance exerts a significant positive effect on hardiness (β = 0.579, p < 0.001), indicating that construction workers who experience a balanced interface between their family and work domains tend to demonstrate greater psychological resilience and coping capacity. Similarly, family work balance is negatively associated with unsafe behavior (β = −0.193, p < 0.001), suggesting that higher harmony between work and family life reduces the likelihood of risk-taking or safety violations at construction sites. Furthermore, hardiness has a significant negative relationship with unsafe behavior (β = −0.659, p < 0.001), implying that resilient workers are more capable of managing work stress and adhering to safety practices. Collectively, these results confirm H1, H2, and H3.

To evaluate the indirect mechanism, bootstrapping with 5000 resamples was employed, a technique that produces robust estimates for mediation testing. The results reveal that the indirect effect of family work balance on unsafe behavior through hardiness is statistically significant (β = −0.381, SE = 0.040, 95% CI [−0.461, −0.107]), confirming the mediating role of hardiness. The total effect of family work balance on unsafe behavior (β = −0.574, 95% CI [−0.672, −0.476]) remained significant after including the mediator, indicating partial mediation. This finding underscores that, while family work balance directly reduces unsafe acts, its effect is largely transmitted through the development of worker hardiness.

Quantitatively, the indirect effect accounted for approximately 66% of the total effect, suggesting that hardiness plays a substantial role in explaining how family work balance translates into safer behavioral outcomes. These results align with contemporary perspectives in occupational safety research [1,8,9], which emphasize the importance of individual psychological resources in reinforcing the positive influence of work–life equilibrium on safety performance. Overall, these findings demonstrate that promoting family work balance fosters workers’ psychological strength, which in turn diminishes unsafe practices and contributes to a safer construction environment.

5.4. Hypothesis Testing for Direct and Moderation Analysis

To test the moderation hypotheses, Model 15 of Hayes’s PROCESS macro (version 4.2) was utilized with 5000 bootstrapped samples. All predictors were mean-centered to minimize multicollinearity, and both experience and education were controlled for as covariates to mitigate potential endogeneity and omitted variable bias [1,130]. These control variables were included because individual differences in experience and education may influence the degree to which workers engage in unsafe behavior. The results of the moderation analyses are summarized in Table 6.

Table 6.

Test results for moderation analysis.

In Model 2, family work balance exhibited a significant negative effect on unsafe behavior (β = −0.182, SE = 0.065, t = −2.801, p < 0.05, 95% CI [−0.310, −0.055]), demonstrating that employees with higher family–work balance are less likely to engage in unsafe acts. More importantly, this relationship was significantly moderated by mastery climate (β = −0.156, SE = 0.051, t = −3.058, p < 0.01, 95% CI [−0.256, −0.056]), confirming that the effect of family–work balance on unsafe behavior depends on the perceived level of mastery climate. These findings support H5.

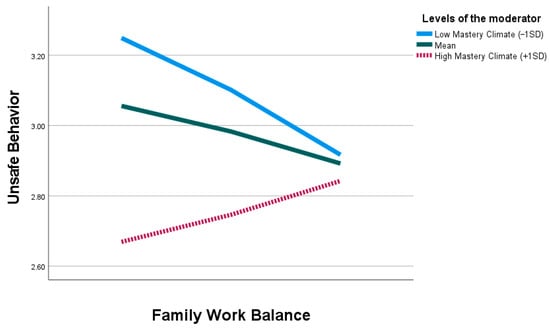

To better understand this interaction, a simple slope analysis following Aiken and West [131] was conducted. The graphical representation in Figure 3 demonstrates that for construction workers perceiving a low mastery climate (−1 SD), the negative relationship between family work balance and unsafe behavior was significantly stronger (β = −0.515, SE = 0.050, t = −10.304, p < 0.001, 95% CI [−0.613, −0.417]). Conversely, for workers perceiving a high mastery climate (+1 SD), the relationship, though still significant, was weaker (β = −0.440, SE = 0.067, t = −6.489, p < 0.001, 95% CI [−0.573, −0.306]). This indicates that in highly cooperative and goal-oriented work environments, the influence of family–work balance on reducing unsafe behavior becomes more consistent and sustainable, rather than dependent on external pressures or situational factors.

Figure 3.

Simple slope analysis for the interaction between family work balance and mastery climate on unsafe behavior.

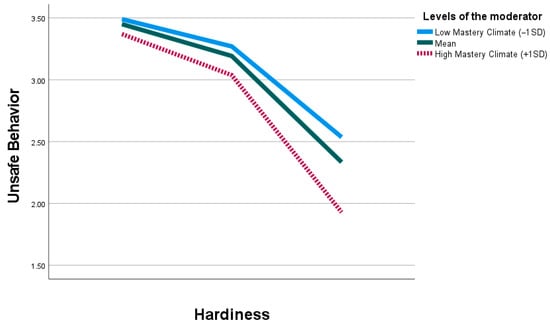

Additionally, hardiness exhibited a significant negative effect on unsafe behavior (β = −0.539, SE = 0.047, t = −11.373, p < 0.001, 95% CI [−0.632, −0.446]), emphasizing that workers with higher psychological resilience tend to display safer work practices. This relationship was also moderated by mastery climate (β = −0.125, SE = 0.052, t = −2.387, p < 0.05, 95% CI [−0.228, −0.022]), providing support for H6. As shown in Figure 4, the simple slope analysis revealed that under conditions of low mastery climate (−1 SD), the negative association between hardiness and unsafe behavior was stronger (β = −0.185, SE = 0.080, t = −2.856, p < 0.001, 95% CI [−0.312, −0.576]), whereas under high mastery climate (+1 SD), the relationship was comparatively weaker (β = −0.119, SE = 0.055, t = −2.200, p < 0.05, 95% CI [−0.185, −0.290]).

Figure 4.

Simple slope analysis for the interaction between hardiness and mastery climate on unsafe behavior.

Overall, these findings indicate that mastery climate functions as a contextual amplifier that reinforces the positive effects of both family work balance and hardiness in mitigating unsafe behavior. When organizations cultivate an environment that emphasizes learning, collaboration, and mutual support, workers become more responsive to psychological and social resources that promote safety compliance. Thus, mastery climate serves as a crucial contextual mechanism that strengthens the influence of individual and family-related factors on safety performance within the construction sector.

5.5. Summary of Key Findings

Grounded in spillover theory and the COR theory, this study explored how family–work balance affects unsafe behavior among new-generation construction workers in Turkey. It further examined the mediating role of hardiness and the moderating influence of mastery climate. By integrating these frameworks, the study offers a nuanced understanding of how personal and contextual resources jointly shape safety-related behavior within a high-risk industry.

The findings reveal a negative relationship between family–work balance and unsafe behavior, supporting H1. This indicates that construction workers who maintain a balanced interface between their family and work domains are less likely to engage in unsafe conduct. This result aligns with previous studies showing that family–work enrichment improves focus, energy, and self-regulation, thereby enhancing safety compliance [21,65]. From the spillover perspective, this implies that positive emotional and cognitive resources accumulated in the family domain are transferred to the work domain, reducing the likelihood of fatigue, distraction, and risky actions [35]. Hence, when workers achieve family–work harmony, they bring psychological stability and clarity that translate into safer performance on-site, reinforcing the argument that resource flows between domains influence occupational safety outcomes.

The study also found that family–work balance positively predicts hardiness, supporting H2. This relationship is consistent with the view that a balanced lifestyle nurtures psychological resilience and adaptive coping [74,132]. Workers who experience equilibrium across personal and professional roles can better regulate stress responses and preserve cognitive resources. According to COR theory, balance in one’s life facilitates the accumulation and preservation of psychological resources, which can later be deployed to manage demanding or uncertain work conditions [39]. This outcome illustrates that positive spillover between life domains strengthens internal coping capacities, fostering a hardy mindset that buffers against the stressors typical in construction environments.

The analysis further demonstrated that hardiness is negatively related to unsafe behavior, aligning with H3. This finding corrects earlier inconsistencies and supports prior evidence that resilient workers are more likely to comply with safety standards and exhibit proactive safety behaviors [77,133]. From the COR perspective, hardiness represents a vital psychological resource that protects individuals from resource depletion by maintaining emotional control and cognitive focus under pressure. Consequently, hardy individuals are less prone to fatigue-induced errors, rule violations, or risky improvisations. This result extends the spillover logic by suggesting that psychological resilience functions as a bridge between internal regulation and observable safety behavior, where emotional stability directly influences behavioral outcomes.

Moreover, the results confirmed that hardiness partially mediates the relationship between family–work balance and unsafe behavior, lending support to H4. Quantitatively, the indirect effect accounted for approximately 66% of the total effect, demonstrating that psychological resilience is a central pathway through which work–family harmony translates into safer conduct. This outcome indicates that workers with a balanced life experience resource gain, which enhances their capacity for self-control and reduces cognitive overload [9,71,133]. In the context of COR theory, family–work balance operates as a resource generator, while hardiness acts as a resource protector that channels these benefits into tangible safety outcomes.

Finally, the moderating effects of mastery climate (H5 and H6) revealed that a supportive and learning-oriented work environment strengthens the beneficial effects of both family–work balance and hardiness on safety behavior. In line with COR theory, a high mastery climate serves as an external contextual resource that stimulates resource caravans—clusters of personal and social resources that reinforce one another [1,8,9]. Workers operating in such climates are more motivated to uphold safety norms and are better equipped to manage stressors collectively. Under strong mastery climates, resource transmission from family–work balance to safety performance becomes more efficient, while the effect of hardiness on safe behavior becomes more sustainable. This demonstrates the pivotal role of supportive environments in magnifying psychological and familial resources to reduce unsafe practices.

In summary, all hypotheses (H1–H6) received empirical support. The findings collectively affirm that the interaction between personal balance, psychological hardiness, and mastery climate forms a comprehensive system of protection against unsafe behavior. Theoretically, the integration of spillover and COR perspectives enriches understanding of how resources move across domains and how contextual factors determine whether these resources translate into safer actions. Practically, these results emphasize that fostering both family–work balance and mastery-oriented environments can jointly enhance safety culture within the construction industry, particularly for younger generations facing multiple role pressures.

6. Implications and Limitations

6.1. Theoretical Implications

This study makes several significant theoretical contributions to the construction safety management literature by expanding the understanding of how family–work balance functions as a cross-domain resource that influences workers’ unsafe behavior [19,21]. First, the study advances both Spillover Theory and the COR theory by revealing that family–work balance—not merely the absence of conflict—plays a pivotal role in shaping safe conduct at work. While previous studies have focused primarily on work–family conflict and its detrimental outcomes [2,134], the present research redirects attention toward the positive resource pathways that arise when balance exists. By demonstrating that balance enables psychological and behavioral resource transfer across life domains, this study extends the theoretical boundaries of spillover effects from conflict-based depletion to balance-based enrichment, thereby providing a new conceptual lens for understanding safety outcomes among construction workers.

Second, this study extends theoretical knowledge by empirically validating the link between family–work balance and hardiness—a relationship that has received little attention in occupational safety research. By situating this association within Spillover Theory, the research reframes family–work balance as not only an antecedent of affective well-being but also a driver of psychological resilience traits such as hardiness [56,91]. This conceptual expansion contributes to both COR and Spillover perspectives by emphasizing that balance serves as a personal resource generator that fosters internal coping strength, enabling workers to preserve and deploy psychological resources under demanding conditions. Hence, this study enriches theoretical discourse by integrating the resource accumulation process (COR theory) with the cross-domain resource transmission mechanism (Spillover theory).

Third, the study introduces hardiness as a mediating mechanism that explains how and why family–work balance influences unsafe behavior. Previous research has primarily examined direct associations between work–family dynamics and safety performance, but this study identifies hardiness as the internal psychological channel through which balance translates into safer work behavior [17,21]. This advancement clarifies that workers who experience family–work harmony are more likely to develop resilience and self-regulation, which in turn decrease the likelihood of safety violations [32]. Consequently, the findings contribute to the growing body of literature that views personal psychological resources as mediating forces linking broader life experiences to occupational safety performance.

Finally, by identifying mastery climate as a boundary condition that amplifies the effects of family–work balance and hardiness, this study extends the application of COR theory to a multilevel perspective. It demonstrates that contextual resources such as supportive and learning-oriented climates interact with individual-level resources to form “resource caravans,” thereby enhancing their combined influence on safety outcomes [87,90,92]. This insight moves beyond traditional safety climate research by introducing motivational climate as a novel contextual moderator that integrates psychological and environmental resource systems. Collectively, these contributions advance theoretical understanding of how family–work balance, psychological hardiness, and mastery climate jointly operate within a resource-based ecosystem that shapes safety behavior in the construction industry.

6.2. Practical Implications

The findings of this study provide several meaningful managerial implications for both construction firms and workers. First, the results highlight that family–work balance is not merely a personal matter but a strategic organizational concern that directly affects safety outcomes. Therefore, construction firms should adopt family-supportive practices that help workers maintain equilibrium between professional and personal responsibilities. Given the rigid timelines and project-based nature of construction work [15,63], traditional family-supportive practices such as flexible working hours may be difficult to implement. However, firms can adopt alternative project-specific strategies—such as providing sufficient rest periods between project phases, offering flexible rotation schedules, and limiting prolonged overtime—to ensure workers can fulfill family responsibilities and recover psychologically before subsequent assignments.

In addition, construction companies should consider introducing family-oriented initiatives such as childcare support, family health benefits, and structured family-leave policies, which have proven effective in improving employee well-being in other industries. These policies, even when modestly adapted to construction settings, can significantly enhance workers’ morale, reduce fatigue, and, consequently, minimize unsafe behavior. When extended beyond compliance-based practices, such initiatives signal organizational care, foster mutual trust, and indirectly reinforce safety engagement [135,136].

Second, the mediation results emphasize that firms aiming to reduce unsafe behavior should invest in developing workers’ hardiness as a psychological resource. Beyond formal policies, managers can introduce training programs focused on resilience building, mindfulness, workload management, and self-determination skills, which have been shown to strengthen coping mechanisms and self-regulation. These interventions not only help workers handle occupational stress but also reinforce their ability to make safer decisions in high-pressure environments [58]. Embedding these practices into safety training curricula can thus bridge the gap between psychological well-being and practical safety compliance.

Third, creating a mastery-oriented climate is critical for sustaining long-term safety culture. The results suggest that while family–work balance independently contributes to safer behavior, its positive influence is amplified within a supportive and learning-focused work environment. Construction firms should therefore cultivate a mastery climate that values continuous learning, cooperative teamwork, and developmental feedback rather than punitive supervision. Such environments motivate workers to share safety knowledge, support peers, and internalize safety values as part of daily routines. This aligns with Amirah et al. [137], who emphasize that effective safety culture emerges not solely from policies but from observable safety behaviors reinforced through organizational climates of trust and mastery.

Collectively, these implications suggest that combining family-supportive initiatives with psychological and environmental reinforcements—such as resilience training and mastery climate—creates a comprehensive framework for sustaining a safety-oriented workforce. By addressing both the personal and contextual dimensions of worker behavior, construction firms can build a culture where well-being and safety mutually reinforce one another, ultimately reducing accidents and enhancing overall project performance.

6.3. Limitations and Research Directions for Future Studies

Although this study offers valuable insights into the mechanisms through which family–work balance reduces unsafe behavior, several limitations warrant acknowledgment. First, the cross-sectional research design restricts the ability to draw causal inferences between family–work balance, hardiness, mastery climate, and unsafe behavior. Future research could adopt longitudinal or time-lagged approaches to observe how these relationships evolve over time and capture the dynamic effects of family and work demands on safety performance. Second, the reliance on self-reported data introduces potential biases such as social desirability and common method variance (CMB), even though procedural and statistical remedies were applied. Future studies are encouraged to employ multi-source data collection methods—combining self-reports with supervisor ratings or behavioral safety records—to enhance validity. Moreover, integrating multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM) frameworks, as suggested by Omidi et al. [138], could assist researchers in systematically prioritizing and evaluating multiple safety determinants beyond self-report measures.

Third, the non-random sample from Turkish construction workers limits generalizability to other industries and cultural settings. Future research should therefore include randomized or stratified samples across different sectors such as manufacturing, oil and gas, and healthcare to examine contextual influences on the proposed relationships. Additionally, hardiness was treated as a single-dimensional construct, whereas it consists of multiple components—commitment, control, and challenge [30]. Future studies should decompose these dimensions to identify which are most influential in mitigating unsafe behaviors. Other personal resources such as coping self-efficacy, mindfulness, and grit could also be tested as mediators or moderators to extend understanding of psychological mechanisms in high-risk work environments. Finally, adopting mixed-method or experimental designs could help uncover how family–work dynamics and organizational climates interact to shape daily safety practices, offering more comprehensive and context-sensitive insights for developing effective interventions.

7. Conclusions

This study contributes to construction-safety research by demonstrating that family–work balance plays a pivotal role in mitigating unsafe behavior among new-generation construction workers. Drawing on Spillover Theory and the COR theory, the findings reveal that a healthy balance between family and work domains promotes psychological stability, which translates into safer conduct on construction sites. Hardiness emerged as a key mediating psychological resource, explaining how balanced workers convert personal resilience into safe behavioral outcomes. Moreover, a strong mastery climate amplifies these positive effects, highlighting the importance of learning-oriented and supportive environments that transform individual resources into collective safety practices. These results emphasize that both personal balance and contextual support are essential to sustaining safety performance in high-risk industries such as construction.

Theoretically, this study extends the understanding of resource transmission between family and work domains, positioning family–work balance as a proactive resource generator rather than merely the absence of conflict. Practically, it suggests that construction organizations can foster safer behavior by promoting family-supportive policies, strengthening resilience-training initiatives, and cultivating mastery-oriented climates that value continuous learning and well-being. Taken together, these insights provide a foundation for future interventions aimed at enhancing occupational safety and enriching workers’ quality of life, offering a pathway toward a more human-centered and sustainable construction industry.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.A.; formal data analysis, K.I.; supervision, B.V.; project administration, B.V. and A.B.A.; Validation, K.I. and A.A.; Writing—original draft, A.A.; Writing—review and editing, A.B.A. and A.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

University of Mediterranean Karpasia’s Institutional Review Board [Approval number 2024-2025 Fall 003-Tuesday, approval date 3 December 2024].

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ayouz, H.; Alzubi, A.; Iyiola, K. Using Benevolent Leadership to Improve Safety Behaviour in the Construction Industry: A Moderated Mediation Model of Safety Knowledge and Safety Training and Education. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Ergon. 2024, 31, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuang, Q.; Shuai, X.; Liang, H.; Bai, J. How Work-Family Conflict Affects Highway Construction Professionals’ Safety Citizenship Behaviors: A Moderated Mediation Model. Saf. Sci. 2025, 191, 106976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Wang, D.; Tong, Z.; Wang, X. Investigation and Analysis of the Safety Risk Factors of Aging Construction Workers. Saf. Sci. 2023, 167, 106281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafindadi, A.D.; Napiah, M.; Othman, I.; Mikić, M.; Haruna, A.; Alarifi, H.; Al-Ashmori, Y.Y. Analysis of the Causes and Preventive Measures of Fatal Fall-Related Accidents in the Construction Industry. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2022, 13, 101712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bureau of Labor Statistics Census of Fatal Occupational Injuries Summary. Available online: https://www.bls.gov/news.release/cfoi.nr0.htm (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Olimat, H.; Alwashah, Z.; Abudayyeh, O.; Liu, H. Data-Driven Analysis of Construction Safety Dynamics: Regulatory Frameworks, Evolutionary Patterns, and Technological Innovations. Buildings 2025, 15, 1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Naser, N.K.; Al-Tabtabai, H. The Impact of Safety Violations on Construction Project Performance: A Case Study of the ADFA Project. J. Eng. Res. 2024, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Iyiola, K.; Alzubi, A.; Aljuhmani, H.Y. Using Safety-Specific Transformational Leadership to Improve Safety Behavior Among Construction Workers: Exploring the Role of Knowledge Sharing and Psychological Safety. Buildings 2025, 15, 3340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slil, E.; Iyiola, K.; Alzubi, A.; Aljuhmani, H.Y. Impact of Safety Leadership and Employee Morale on Safety Performance: The Moderating Role of Harmonious Safety Passion. Buildings 2025, 15, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heng, P.P.; Yusoff, H.M.; Hod, R. Individual Evaluation of Fatigue at Work to Enhance the Safety Performance in the Construction Industry: A Systematic Review. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0287892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, A.P.C.; Guan, J.; Choi, T.N.Y.; Yang, Y.; Wu, G.; Lam, E. Improving Safety Performance of Construction Workers through Learning from Incidents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, A.; Griffin, M.A. A Study of the Lagged Relationships among Safety Climate, Safety Motivation, Safety Behavior, and Accidents at the Individual and Group Levels. J. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 91, 946–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Z.; Fang, D.; Zhang, M. Understanding the Causation of Construction Workers’ Unsafe Behaviors Based on System Dynamics Modeling. J. Manag. Eng. 2015, 31, 04014099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, X.; Zhai, F.; Xia, N.; Hu, X. Protecting the Ego: Anticipated Image Risk as a Psychological Deterrent to Construction Workers’ Safety Citizenship Behavior. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2024, 150, 04023146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Xu, N.; Jiang, H.; Wang, S.; Wang, W.; Wang, J. Psychological Driving Mechanism of Safety Citizenship Behaviors of Construction Workers: Application of the Theory of Planned Behavior and Norm Activation Model. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2020, 146, 04020027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MG, S.P.; KS, A.; Rajendran, S.; Sen, K.N. The Role of Psychological Contract in Enhancing Safety Climate and Safety Behavior in the Construction Industry. J. Eng. Des. Technol. 2024, 23, 1189–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adinyira, E.; Manu, P.; Agyekum, K.; Mahamadu, A.-M.; Olomolaiye, P.O. Violent Behaviour on Construction Sites: Structural Equation Modelling of Its Impact on Unsafe Behaviour Using Partial Least Squares. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2020, 27, 3363–3393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukamani, D.; Wang, J.; Kusi, M. Impact of Safety Worker Behavior and Safety Climate as Mediator and Safety Training as Moderator on Safety Performance in Construction Firms in Nepal. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2021, 25, 1555–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adah, C.A.; Aghimien, D.O.; Oshodi, O. Work–Life Balance in the Construction Industry: A Bibliometric and Narrative Review. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2023, 32, 38–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, Y.; Wenjing, Q.; Jizu, L.; Yong, Y.; Yanyu, G. Work–Family Conflict, Work Engagement and Unsafe Behavior among Miners in China. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Ergon. 2023, 29, 1376–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ni, G.; Fang, Y.; Miao, X.; Qiao, Y.; Wang, W.; Xuan, J. Can Work-Family Balance Reduce the Unsafe Behavior of New Generation of Construction Workers Effectively in China? A Moderated Mediation Model. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2024, 32, 5682–5715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, D.S.; Grzywacz, J.G.; Zivnuska, S. Is Work—Family Balance More than Conflict and Enrichment? Hum. Relat. 2009, 62, 1459–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Xiang, T.; Guo, H.; Ma, L.; Guan, Z.; Fang, Y. Impact of Physical and Mental Fatigue on Construction Workers’ Unsafe Behavior Based on Physiological Measurement. J. Saf. Res. 2023, 85, 457–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, R.; Wang, X.; Wang, L.; Hu, X. A Dual Perspective on Work Stress and Its Effect on Unsafe Behaviors: The Mediating Role of Fatigue and the Moderating Role of Safety Climate. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2022, 165, 929–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Wu, L.-Z.; Lyu, Y.; Liu, X. How to Make the Work-Family Balance a Reality among Frontline Hotel Employees? The Effect of Family Supportive Supervisor Behaviors. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2024, 120, 103746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žnidaršič, J.; Bernik, M. Impact of Work-Family Balance Results on Employee Work Engagement within the Organization: The Case of Slovenia. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0245078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manivannan, J.; Loganathan, S.; Kamalanabhan, T.J.; Kalidindi, S.N. Investigating the Relationship between Occupational Stress and Work-Life Balance among Indian Construction Professionals. Constr. Econ. Build. 2022, 22, 27–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abas, N.H.; Saharan, N.A.; Rahmat, M.H.; Ghing, T.Y.; Abas, N.H.A. Work-Life Balance Practices among Professionals in Malaysian Construction Industry. Malays. Constr. Res. J. 2021, 13, 103–116. [Google Scholar]

- Aghimien, D.; Aigbavboa, C.O.; Thwala, W.D.; Chileshe, N.; Dlamini, B.J. Help, I Am Not Coping with My Job!—A Work-Life Balance Strategy for the Eswatini Construction Industry. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2022, 31, 140–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobasa, S.C.; Maddi, S.R.; Kahn, S. Hardiness and Health: A Prospective Study. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1982, 42, 168–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mund, P.; Mishra, M. Hardiness: A Review and Research Agenda. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2025, 233, 112882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandvik, A.M.; Hansen, A.L.; Hystad, S.W.; Johnsen, B.H.; Bartone, P.T. Psychopathy, Anxiety, and Resiliency—Psychological Hardiness as a Mediator of the Psychopathy–Anxiety Relationship in a Prison Setting. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2015, 72, 30–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delahaij, R.; Gaillard, A.W.K.; van Dam, K. Hardiness and the Response to Stressful Situations: Investigating Mediating Processes. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2010, 49, 386–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eva Dodoo, J.; Surienty, L.; Zahidah, S. Safety Citizenship Behaviour of Miners in Ghana: The Effect of Hardiness Personality Disposition and Psychological Safety. Saf. Sci. 2021, 143, 105404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, D.S.; Thompson, M.J.; Crawford, W.S.; Kacmar, K.M. Spillover and Crossover of Work Resources: A Test of the Positive Flow of Resources through Work–Family Enrichment. J. Organ. Behav. 2019, 40, 709–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolger, N.; DeLongis, A.; Kessler, R.C.; Wethington, E. The Contagion of Stress across Multiple Roles. J. Marriage Fam. 1989, 51, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crouter, A.C. Spillover from Family to Work: The Neglected Side of the Work-Family Interface. Hum. Relat. 1984, 37, 425–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of Resources: A New Attempt at Conceptualizing Stress. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E.; Halbesleben, J.; Neveu, J.-P.; Westman, M. Conservation of Resources in the Organizational Context: The Reality of Resources and Their Consequences. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2018, 5, 103–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M.T. A Two Wave Cross-Lagged Study of Work-Role Conflict, Work-Family Conflict and Emotional Exhaustion. Scand. J. Psychol. 2016, 57, 591–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, M.A.; Imran, M.; Mughal, F.; Mujtaba, B.G. Assessing the Spillover Effect of Despotic Leadership on an Employee’s Personal Life in the Form of Family Incivility: Serial Mediation of Psychological Distress and Emotional Exhaustion. Public Organ. Rev. 2024, 24, 1171–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Shi, J.; Liu, Y. The Impact of Corporate Social Responsibility in Technological Innovation on Sustainable Competitive Performance. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nerstad, C.G.L.; Searle, R.; Černe, M.; Dysvik, A.; Škerlavaj, M.; Scherer, R. Perceived Mastery Climate, Felt Trust, and Knowledge Sharing. J. Organ. Behav. 2018, 39, 429–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J.R.; Rothbard, N.P. Mechanisms Linking Work and Family: Clarifying the Relationship Between Work and Family Constructs. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2000, 25, 178–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akanji, B.; Mordi, C.; Ajonbadi, H.A. The Experiences of Work-Life Balance, Stress, and Coping Lifestyles of Female Professionals: Insights from a Developing Country. Empl. Relat. Int. J. 2020, 42, 999–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, D.S.; Kacmar, K.M.; Wayne, J.H.; Grzywacz, J.G. Measuring the Positive Side of the Work–Family Interface: Development and Validation of a Work–Family Enrichment Scale. J. Vocat. Behav. 2006, 68, 131–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, D.; Derks, D.; Bakker, A.B. Daily Spillover from Family to Work: A Test of the Work–Home Resources Model. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2018, 23, 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, E.J.; Hawkins, A.J.; Ferris, M.; Weitzman, M. Finding an Extra Day a Week: The Positive Influence of Perceived Job Flexibility on Work and Family Life Balance. Fam. Relat. 2001, 50, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, G.C.; Hammer, L.B.; Colton, C.L. Development and Validation of a Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Work-Family Positive Spillover. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2006, 11, 249–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.-W.; Hong, Y.-C.; Seo, H.; Yun, J.-Y.; Nam, S.; Lee, N. Different Influence of Negative and Positive Spillover between Work and Life on Depression in a Longitudinal Study. Saf. Health Work 2021, 12, 377–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.; Oh, M. Work-to-Life Spillover and Organizational Commitment: The Moderating Role of Flextime and Sectoral Differences Between Public and Non-Public Organizations. Public Pers. Manag. 2025, 54, 00910260251319817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzywacz, J.G.; Marks, N.F. Reconceptualizing the Work–Family Interface: An Ecological Perspective on the Correlates of Positive and Negative Spillover between Work and Family. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2000, 5, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunkcu, H.; Koc, K.; Gurgun, A.P. Work–Family Conflict and High-Quality Relationships in Construction Project Management: The Effect of Job and Life Satisfaction. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2024, 32, 3937–3962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratnaningsih, I.Z.; Idris, M.A. Spillover–Crossover Effect of Work–Family Interface: A Systematic Review. Fam. J. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. The Influence of Culture, Community, and the Nested-Self in the Stress Process: Advancing Conservation of Resources Theory. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 50, 337–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.E.; Meier, L.L.; Spector, P.E. The Spillover Effects of Coworker, Supervisor, and Outsider Workplace Incivility on Work-to-Family Conflict: A Weekly Diary Design. J. Organ. Behav. 2019, 40, 1000–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wayne, J.H.; Matthews, R.; Crawford, W.; Casper, W.J. Predictors and Processes of Satisfaction with Work–Family Balance: Examining the Role of Personal, Work, and Family Resources and Conflict and Enrichment. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2020, 59, 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]