Abstract

Reducing energy demand and carbon emissions in residential buildings requires more than technological upgrades; it demands a nuanced understanding of occupant behaviour. Residential energy use is shaped by both physical design and human actions, yet behavioural factors remain underexplored, contributing to the energy performance gap. This study addresses this issue by developing and validating a behavioural framework grounded in the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) to examine how attitudes, social norms, perceived control, and environmental awareness influence energy-related decisions. Data were collected through an online survey of 310 households in metropolitan Sydney and analysed using Stata v17 software employing principal component analysis and regression modelling. Results reveal that environmental awareness is the most significant predictor of pro-environmental intention, which strongly correlates with actual behavioural outcomes. While attitudes and perceived control were generally positive, subjective norms and awareness remained moderate, limiting behavioural change. The proposed framework demonstrates strong validity and reliability, offering a practical tool for policymakers, designers, and educators to integrate behavioural insights into sustainable building strategies. By prioritising awareness campaigns and normative interventions, stakeholders can complement technical retrofits with behavioural measures, accelerating progress towards low-carbon housing and benefiting both households and the broader community.

1. Introduction

The residential building sector in Australia exerts a considerable influence on national energy demand and carbon emissions, making it a focal point for sustainability initiatives [1]. Energy use within buildings is shaped not only by physical characteristics such as envelope design and mechanical systems but also by occupant behaviour, which can exert an impact equal to or greater than technological measures [2,3]. Empirical evidence demonstrates that user actions—such as thermostat settings, ventilation habits, and appliance operation—directly affect thermal comfort and energy performance [4,5]. A study conducted at Cambridge University estimated that behavioural interventions could increase energy savings by up to 200%, surpassing gains achieved through technological retrofits alone [6]. This finding underscores the necessity of integrating behavioural considerations into energy efficiency strategies. Building-level and programme-level studies further indicate that behavioural factors must be considered alongside retrofit measures to achieve durable, real-world energy savings [6,7,8,9,10].

Residential buildings account for a significant share of Australia’s carbon emissions, making carbon reduction a central objective of national sustainability policies. The Australian Government has introduced energy efficiency provisions under the National Construction Code (NCC) and complementary initiatives such as the Nationwide House Energy Rating Scheme (NatHERS) to reduce emissions and improve thermal performance. Despite these measures, the residential sector continues to face challenges in meeting carbon reduction targets due to behavioural variability among occupants. This study focuses on residential properties in metropolitan Sydney, including freestanding houses, semi-detached dwellings, and apartments, which collectively represent the dominant housing typologies in urban Australia. These dwellings are subject to NCC climate zones 5 and 6, influencing heating and cooling demands. By examining behavioural determinants within this context, the research aims to complement existing policy frameworks with strategies that address the human dimension of energy use, thereby bridging the gap between technical compliance and actual carbon reduction outcomes [8,9,10].

Despite this, current design and modelling practices often rely on unrealistic assumptions about occupant behaviour, resulting in inaccuracies and widening the energy performance gap [11]. Each individual occupant has the potential to significantly influence overall building energy consumption, introducing variability that complicates predictive modelling [12,13]. While technological upgrades remain essential, they cannot deliver optimal outcomes without complementary behavioural measures [7]. Research consistently highlights that focusing exclusively on physical improvements neglects the substantial potential for energy savings through behavioural change [8,9]. Studies have shown that incorporating behavioural factors into building development processes is as critical as improving the quality of the building envelope and equipment [14]. Recent work by Far et al. [10] reinforces this argument, demonstrating that occupant behaviour significantly contributes to the energy performance gap in residential buildings. While technological upgrades remain essential, multiple studies show that these cannot deliver optimal outcomes without complementary behavioural measures; incorporating behavioural factors into building development and retrofit processes is therefore as critical as improving the quality of the building envelope and equipment [3,7,8,9,10,11]. In practice, interventions that combine technical improvements with behaviour-oriented components have been associated with stronger and more persistent reductions in energy use [8,9,10,11].

The literature identifies a persistent gap in understanding the social norms, priorities, and decision-making processes that shape household energy practices [15,16]. These behavioural dimensions are deeply intertwined with sustainability outcomes, necessitating targeted interventions informed by robust empirical evidence [17]. However, research addressing the multifaceted nature of occupant behaviour remains limited, and calls for comprehensive data collection have intensified [18,19]. Behavioural uncertainty continues to undermine energy efficiency initiatives, making it one of the most significant sources of variability in determining actual energy consumption [20]. The need for systematic investigation into occupant behaviour and its relationship with thermal energy use has been repeatedly emphasised in recent studies [21,22]. Far and Far [23] further highlight that effective thermal retrofitting strategies must be complemented by behavioural change to achieve meaningful reductions in energy use. Beyond norms and awareness, two well-documented phenomena from the efficiency literature help explain why predicted savings can diverge from outcomes in residential contexts: the rebound effect (where improved efficiency can lead to increased usage of energy services, offsetting some savings) and the prebound effect (where baseline consumption is already lower than modelled predictions due to existing conservation behaviours). Recognising these effects is essential for realistic goal setting and for designing behavioural components that preserve, rather than erode, efficiency gains [8,9,10].

To address these challenges, this research adopts the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) as its conceptual foundation [24]. TPB provides a structured approach to examining how attitudes, subjective norms, perceived behavioural control, and environmental awareness influence behavioural intentions and actions. By operationalising these constructs within a residential context, the study aims to develop and validate a behavioural framework capable of predicting and promoting pro-environmental practices. This framework seeks to bridge the gap between theoretical modelling and practical application, enabling policymakers, designers, and educators to integrate behavioural insights into sustainability strategies. By operationalising these constructs within a residential context and explicitly incorporating environmental awareness as a salient antecedent, the study develops and validates a behavioural framework capable of predicting and promoting pro-environmental practices; prior TPB-based applications support the relevance of these constructs for shaping energy-related decisions in educational and workplace settings [10,25]. Accordingly, the remainder of the paper focuses on identifying the behavioural levers most likely to accelerate residential decarbonisation, quantifying their effects on intention and behaviour, and outlining implementation pathways that complement technological retrofits. The overarching research question is: how do attitudes, subjective norms, behavioural control, and environmental awareness influence occupant behaviour leading to an intention to modify thermal comfort to reduce energy use?

The research philosophy underpinning this study is positivism, which is considered the most appropriate approach for quantitative investigations of behavioural constructs [25]. Yet complementary studies on structural systems also provide valuable insights for achieving long-term sustainability [26,27,28,29,30]. These works collectively emphasise that effective frameworks for reducing energy use and emissions must account for both behavioural dynamics and the physical characteristics of buildings. By aligning behavioural interventions with innovative design practices, the potential to close the energy performance gap and enhance resilience across residential environments becomes significantly greater. Unlike constructivism and pragmatism, which rely heavily on qualitative methods and social interaction, positivism emphasises objective measurement and statistical analysis. This philosophy aligns with the study’s aim to generate numerical data through closed-ended questions and apply established statistical techniques to test hypotheses. The research design operationalises TPB by identifying relevant variables, formulating hypotheses, and employing quantitative methods to examine relationships among constructs. Data were collected via an online survey targeting households in metropolitan Sydney, capturing information on attitudes, subjective norms, perceived behavioural control, environmental awareness, intention to act, and pro-environmental behaviour. Statistical procedures, including principal component analysis and regression modelling, were applied to validate the conceptual framework and assess its predictive capability. The overarching research question guiding this investigation is: How do attitudes, subjective norms, behavioural control, and environmental awareness influence occupant behaviour leading to an intention to modify thermal comfort to reduce energy use? Addressing this question will contribute to closing the energy performance gap and advancing the integration of behavioural strategies into sustainable building design.

2. Research Methodology

2.1. Research Philosophy and Design

The research adopts a positivist philosophy, which is widely recognised as suitable for studies requiring objective measurement and statistical validation [31]. Positivism assumes that reality exists independently of the researcher and can be observed and quantified without bias. This approach aligns with the study’s aim to generate numerical data through structured instruments and apply inferential statistics to test hypotheses [32]. Unlike constructivist or pragmatic paradigms, which rely heavily on qualitative interpretation and social interaction, positivism emphasises empirical observation and deductive reasoning [33]. Consequently, the research design prioritised closed-ended questions, pre-established constructs, and minimal researcher–participant interaction, ensuring objectivity and reproducibility [34].

Why TPB? The Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) was selected because it is one of the most widely validated behavioural models for predicting intention and action across diverse contexts, including energy-related behaviours [20,35,36,37]. TPB integrates attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioural control, which are critical determinants of household energy decisions. Alternative frameworks such as Norm Activation Theory (NAT) and Value-Belief-Norm (VBN) Theory were considered; however, NAT focuses primarily on altruistic norms, and VBN emphasises value orientations, making them less suited for modelling intention-behaviour pathways in residential energy use. TPB offers a more comprehensive structure for linking cognitive, normative, and control factors to intention and behaviour, and its predictive validity has been demonstrated in sustainability research [26,27,28,29,30].

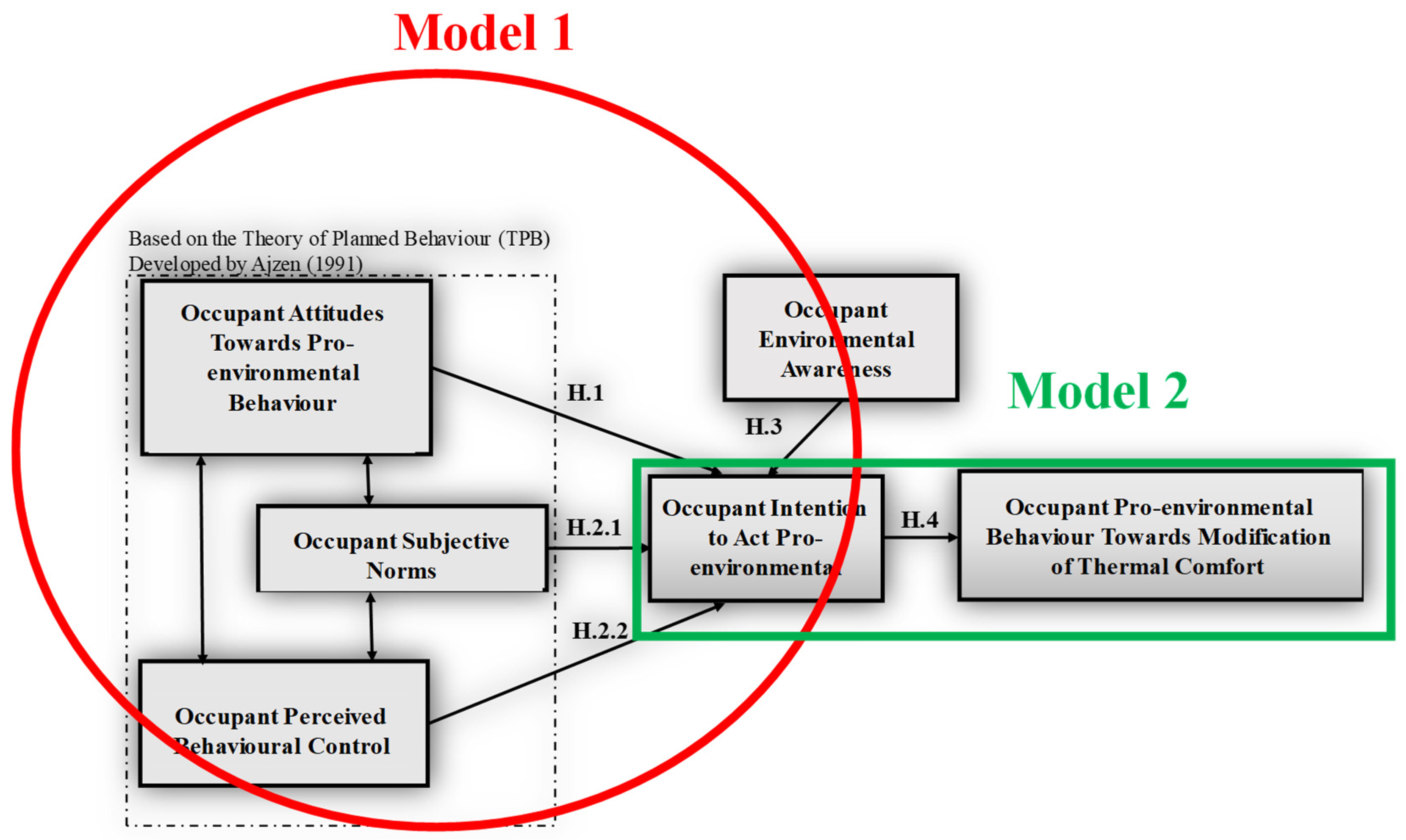

The theoretical foundation of this study is the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB), a well-established model for predicting behavioural intentions and actions [20]. TPB posits that attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioural control collectively influence behavioural intention, which subsequently determines actual behaviour [35]. To contextualise TPB within residential energy use, the framework incorporates additional constructs—environmental awareness and pro-environmental behaviour—reflecting the complexity of household decision-making in thermal comfort management [36]. The conceptual framework hypothesises direct and indirect relationships among six constructs: occupant attitudes (OA), occupant subjective norms (OSN), occupant perceived behavioural control (OPBC), occupant environmental awareness (OEA), occupant intention to act (OITA), and occupant pro-environmental behaviour (OPB). The hypotheses underpinning the framework are as follows: positive attitudes towards energy conservation enhance intention to act pro-environmentally; subjective norms and perceived behavioural control exert a constructive influence on intention to act; higher environmental awareness strengthens intention to act pro-environmentally; and intention to act positively predicts pro-environmental behaviour related to thermal comfort modification.

2.2. Data Collection

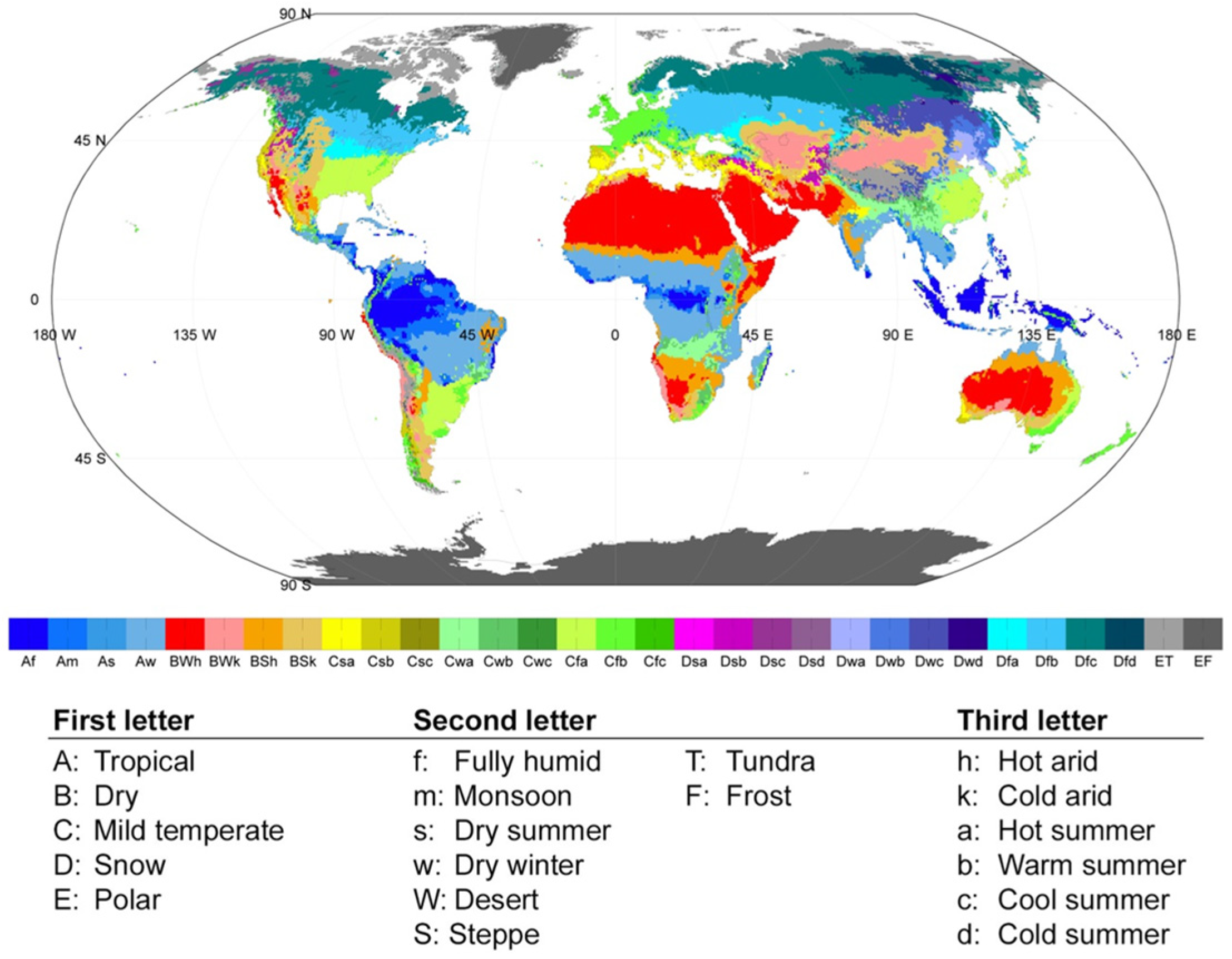

The study focuses on the Sydney Metropolitan Area, which falls under the Mediterranean climate category in Köppen’s classification (Figure 1) and corresponds to Climate Zones 5 and 6 under the National Construction Code (Figure 2). These zones influence heating and cooling demands, making them critical for analysing energy use and carbon reduction strategies. By targeting this climate type, the research provides insights applicable to regions with similar thermal profiles globally. The behavioural factors examined—attitudes, subjective norms, perceived behavioural control, environmental awareness, intention to act, and pro-environmental behaviour—are hypothesised to affect household energy practices, which in turn impact carbon emissions. Findings from this study inform strategies that complement technical retrofits with behavioural interventions, thereby reducing energy demand and associated emissions. Figure 1 and Figure 2 are connected by illustrating how international climate classification aligns with national regulatory zones, providing a framework for linking behavioural insights to policy-driven energy efficiency measures.

Figure 1.

Köppen World’s Climate Classification for Sydney Metropolitan Area.

Figure 2.

Sydney Metropolitan Area Climate Zones under NCC provisions.

A quantitative research design was employed to operationalise the conceptual framework and test the hypotheses. This design facilitates statistical analysis of relationships among constructs and ensures generalisability of findings [38]. Data were collected via an online survey, chosen for its efficiency, cost-effectiveness, and ability to reach a geographically dispersed population during pandemic-related restrictions [39]. Data were collected by the lead author between July and December 2021 using SurveyMonkey software. Flyers containing the survey link were distributed in Sydney CBD, Parramatta, and Hornsby to invite participation. Ethical approval was obtained from the University Human Research Ethics Committee (Approval No. H-2021-0148), and informed consent was secured from all respondents. The survey targeted households in three densely populated suburbs of the Sydney Metropolitan Area—Sydney CBD, Parramatta, and Hornsby—representing diverse socio-demographic profiles [40]. These suburbs fall within Köppen’s Mediterranean climate classification (Figure 1) and National Construction Code Climate Zones 5 and 6 (Figure 2), which influence heating and cooling demands and occupant behaviour [40].

The questionnaire comprised two sections: Part A captured demographic and background information such as age, gender, education, and dwelling type, while Part B measured the six constructs of the conceptual framework using a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree). Survey items were adapted from validated instruments in prior TPB-based studies [37] and refined to reflect residential energy contexts. Ethical approval was obtained from the University Human Research Ethics Committee (Approval No. H-2021-0148), and informed consent was secured from all participants.

To address potential response bias associated with self-reported Likert-scale data, the survey design incorporated measures to minimise non-response and participation bias. Non-response bias occurs when individuals who do not participate differ significantly from those who do, often due to factors influencing willingness or ability to respond. To mitigate this, the questionnaire was carefully constructed with clear, concise items and distributed online to ensure accessibility. The survey was fully anonymised: identities and exact addresses were not collected, only postcodes were requested. These steps encouraged honest participation and reduced reluctance to respond. While objective energy-use metrics were beyond the scope of this behavioural study, the validated framework and reliability checks (Cronbach’s alpha > 0.70, PCA, and regression analysis) strengthen confidence in the findings. Future research will integrate behavioural metrics with real-world energy consumption data to further validate outcomes.

2.3. Sampling and Representativeness

Representativeness was ensured by targeting three densely populated suburbs with diverse socio-demographic profiles [40]. The sample size was calculated using Dillman’s formula [41,42] for a 95% confidence level and 5% margin of error, resulting in a minimum of 270 responses. We achieved 310 valid responses, exceeding this threshold. Demographic analysis confirmed balanced gender distribution (≈55% female, 45% male), age diversity across five brackets, and varied dwelling types (apartments, freestanding houses, and semi-detached homes), reducing non-response bias [43].

Data analysis was conducted using Stata v17, employing two principal techniques. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was used to assess scale reliability through Cronbach’s alpha and to confirm discriminant validity among constructs [44]. Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression was applied to test the significance of hypothesised relationships and evaluate the predictive capability of the framework [45]. The overall model fit was examined using F-tests, while multicollinearity was assessed through Variance Inflation Factors (VIF), with all values below the threshold of 10, indicating no collinearity issues [46]. Interpretation of mean scores followed Pimentel’s qualitative criteria for Likert-scale data [47].

The scope of this study is limited to residential buildings within the Sydney Metropolitan Area, which constrains generalisability to other climatic regions. Behavioural data were self-reported, introducing potential response bias; however, anonymity and ethical safeguards were implemented to minimise this risk [48]. Despite these limitations, the research provides a robust empirical basis for integrating behavioural insights into energy efficiency strategies.

2.4. Conceptual Framework and Hypotheses

To improve clarity and presentation, the methodology is now structured around the conceptual framework illustrated in Figure 3. This framework operationalises TPB by integrating six constructs: Occupant Attitudes (OA), Subjective Norms (OSN), Perceived Behavioural Control (OPBC), Environmental Awareness (OEA), Intention to Act (OITA), and Pro-environmental Behaviour (OPB). Hypotheses specify direct and indirect relationships among these constructs, forming the basis for statistical testing.

Figure 3.

Proposed Conceptual Framework for Occupant Pro-environmental Behaviour and Interconnecting Hypotheses.

Before presenting the statistical results, it is essential to revisit the theoretical structure guiding this analysis. Figure 3 illustrates the proposed conceptual framework for occupant pro-environmental behaviour and the interconnecting hypotheses. This framework operationalises the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) within a residential energy context by integrating six constructs: Occupant Attitudes (OA), Subjective Norms (OSN), Perceived Behavioural Control (OPBC), Environmental Awareness (OEA), Intention to Act (OITA), and Pro-environmental Behaviour (OPB).

The diagram depicts directional relationships hypothesised between constructs. Attitudes, subjective norms, perceived behavioural control, and environmental awareness are posited as antecedents of behavioural intention, which in turn predicts actual pro-environmental behaviour. This structure reflects TPB’s core principle that intention mediates the effect of cognitive and normative factors on behaviour, while introducing environmental awareness as an additional determinant to capture sustainability-specific influences. The framework served as the basis for hypothesis testing through regression modelling.

2.5. Limitations of Data Analysis

While the adopted statistical techniques provide robust insights, the analysis is limited by its cross-sectional design and reliance on self-reported data, which may introduce social desirability bias and restrict causal inference. Additionally, behavioural constructs were measured using Likert scales, which, although widely accepted, may not capture nuanced behavioural variability.

2.6. Justification for Likert Data and Central Tendency

Likert-scale data were treated as approximately interval-level for parametric analysis because aggregated scores across multiple items tend to approximate normal distribution and meet central tendency assumptions. This approach is supported by behavioural research and psychometric literature, which validates the use of means and regression for multi-item Likert constructs.

2.7. Sampling Adequacy and Validity Checks

Sampling adequacy was ensured by exceeding the minimum sample size calculated using Dillman’s formula (n ≥ 270; achieved n = 310). Inter-item correlations and construct validity were confirmed through Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Cronbach’s alpha (all constructs ≥ 0.70). Homogeneity of variances was assessed via residual plots and variance inflation factors (VIF < 10), indicating no multicollinearity issues.

2.8. Post Hoc Tests

Post hoc diagnostics included correlation matrix checks for discriminant validity and variance inflation factor analysis for multicollinearity. No additional post hoc group comparisons were required, as the study focused on predictive modelling rather than experimental treatment effects.

3. Results and Data Analysis

The empirical analysis was conducted on a dataset comprising 310 valid responses collected from households in Sydney CBD, Parramatta, and Hornsby. This sample size exceeded the minimum threshold of 270 calculated using Dillman’s formula, ensuring statistical robustness and representativeness. The demographic composition was diverse and balanced, mitigating non-response bias and reinforcing the reliability of subsequent behavioural modelling.

3.1. Demographic Profile

The demographic characteristics of respondents provide essential context for interpreting behavioural data. As tabulated in Table 1, gender distribution was approximately 55% female and 45% male, consistent with prior sustainability-focused surveys that report marginally higher female engagement. Age segmentation revealed a dominant cohort within the 29–39 bracket (26.45%), followed by younger adults aged 18–28 (20.32%) and middle-aged participants (40–50 years, 20%). Senior groups (51–60 and 61–75 years) collectively accounted for one-third of the sample, ensuring generational diversity.

Table 1.

Age Distribution of Respondents.

Educational attainment was notably high, as shown in Table 2, with nearly half of respondents holding a university degree and a small proportion possessing doctoral qualifications. This suggests a population predisposed to informed decision-making regarding energy practices.

Table 2.

Education Levels of Respondents.

Dwelling types mirrored metropolitan density trends (Table 3), with apartments comprising 43.55% of dwellings, freestanding houses 33.23%, and semi-detached or townhouse configurations 23.23%.

Table 3.

Type of Residence.

3.2. Descriptive Statistics

Mean scores for each construct were calculated and interpreted using Pimentel’s qualitative criteria for Likert-scale data (Table 4). Occupant Attitudes (mean = 3.76) and Perceived Behavioural Control (mean = 3.56) were categorised as “positive,” while Subjective Norms (mean = 2.65) and Environmental Awareness (mean = 2.67) were rated “neutral.” Intention to Act (mean = 2.74) and Pro-environmental Behaviour (mean = 2.96) similarly fell within the neutral range.

Table 4.

Mean Values and Standard Deviations.

3.3. Regression Analysis

OLS regression tested the hypothesised relationships. Model 1 examined predictors of intention (OITA), while Model 2 assessed the effect of intention on behaviour (OPB). Table 5 summarises Model 1 outputs, where Environmental Awareness (β = 0.656, p < 0.001) was the strongest predictor, followed by Subjective Norms (β = 0.128, p = 0.10). Attitudes and Perceived Control were non-significant.

Table 5.

Regression Results for Model 1.

Model 2 (Table 6) demonstrated a strong positive effect of intention on behaviour (β = 0.4963, p < 0.001), validating Hypothesis 4.

Table 6.

Regression Results for Model 2.

Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) analysis confirmed no multicollinearity, with all values below 10. The conceptual framework shown in Figure 3 is pivotal for understanding the behavioural dynamics underlying residential energy use. Its hierarchical structure emphasises that intention acts as the proximal driver of behaviour, consistent with TPB literature. However, the inclusion of environmental awareness as a direct predictor of intention reflects empirical evidence that knowledge of environmental consequences significantly amplifies motivation to act. The regression results corroborate this theoretical proposition: environmental awareness emerged as the strongest predictor of intention (β = 0.656, p < 0.001), overshadowing attitudes and perceived control. This finding validates the framework’s extension beyond classical TPB and underscores the necessity of awareness-based interventions to close the energy performance gap.

3.4. Interpretive Synthesis

The empirical evidence delineates a behavioural paradox: while respondents exhibit strong attitudinal endorsement and perceived agency, these attributes fail to catalyse consistent pro-environmental action in the absence of normative support and heightened ecological awareness. The salience of awareness as a predictor underscores the imperative for targeted educational interventions, while the robust intention–behaviour linkage signals the efficacy of strategies that operationalise motivational constructs into actionable routines. These insights furnish a compelling rationale for integrating behavioural levers into policy and retrofit programmes, thereby bridging the persistent gap between theoretical efficiency and realised performance.

4. Discussion of Findings

The empirical evidence derived from the survey analysis provides critical insights into the behavioural determinants of energy-related practices in residential buildings. The validated conceptual framework (Figure 3) offers a coherent representation of the interdependencies among cognitive, normative, and informational constructs, confirming that pro-environmental behaviour is shaped by a multidimensional structure rather than a single attitudinal driver. The regression outputs demonstrate unequivocally that environmental awareness exerts the most substantial influence on behavioural intention, with a coefficient of 0.656 (p < 0.001), far surpassing the predictive strength of attitudes and perceived behavioural control. This finding challenges the conventional assumption that favourable attitudes alone are sufficient to catalyse behavioural change, revealing that knowledge of environmental consequences is the most decisive factor in motivating households to adopt energy-saving practices.

The relatively modest effect of subjective norms (β = 0.128, p ≈ 0.10) underscores the limited role of social reinforcement within the studied population. This suggests that normative pressures—whether from family, peers, or community networks—are not sufficiently mobilised to influence energy-related decisions. Such a trend is consistent with prior international comparisons, which indicate that Australian households exhibit weaker collective norms around sustainability than their European counterparts. Conversely, perceived behavioural control, often theorised as a critical enabler, was statistically non-significant in this study, implying that respondents do not perceive structural or resource constraints as major barriers. This may reflect the relative affordability and simplicity of behavioural adjustments compared to capital-intensive retrofits, reinforcing the argument that informational deficits, rather than capability limitations, constitute the primary obstacle to behavioural change.

The second regression model elucidates the mediating role of intention, which accounts for 31% of the variance in actual behaviour (β = 0.496, p < 0.001). This confirms the theoretical proposition that intention is the proximal antecedent of action, yet the neutral mean scores for intention (2.74) and behaviour (2.96) reveal a persistent intention–behaviour gap. Such divergence is symptomatic of cognitive dissonance, where pro-environmental aspirations fail to materialise into consistent practices due to competing priorities, habitual inertia, or insufficient behavioural cues. The neutral mean scores for intention and behaviour indicate a persistent gap between motivation and action. This divergence can be attributed to context-specific barriers such as competing household priorities, habitual routines, and the absence of real-time energy feedback, which limit the translation of intention into practice. While this study focused on quantitative modelling, future research will incorporate qualitative insights through interviews and observational studies to capture these contextual dynamics. Furthermore, testing moderating variables—such as age, education level, and dwelling type—in extended regression models could reveal sub-group differences and inform targeted interventions. These refinements will help identify actionable levers for bridging the intention–behaviour gap and enhancing the effectiveness of behavioural strategies. Bridging this gap requires interventions that not only inform but also embed sustainability prompts within daily routines, leveraging mechanisms such as real-time feedback systems, social benchmarking, and incentive structures that convert intention into habitual practice.

When benchmarked against studies in high-income industrialised nations, the Australian cohort exhibits comparable attitudinal strength (mean OA = 3.76) and perceived control (mean OPBC = 3.56) but markedly lower environmental awareness (mean OEA = 2.67) and subjective norms (mean OSN = 2.65). This asymmetry positions Australia at a disadvantage in terms of normative and informational drivers, which are pivotal for accelerating behavioural transitions. The implications are profound: without elevating awareness and fostering normative consensus, policy instruments predicated on voluntary action may underperform, perpetuating the energy performance gap and undermining national emissions reduction targets.

The reliability diagnostics (Cronbach’s α > 0.70 for all constructs) and discriminant validity tests affirm the structural integrity of the framework, while the F-statistics for both models (52.30 and 136.38, respectively) confirm its explanatory adequacy. The absence of multicollinearity (VIF < 10) further strengthens confidence in the robustness of the estimates. Collectively, these metrics validate the framework as a functional tool for modelling occupant behaviour and inform the design of targeted interventions.

Strategically, the empirical hierarchy of determinants—awareness > norms > attitudes/control—necessitates a recalibration of behavioural strategies. Priority should be accorded to awareness amplification through multi-channel educational campaigns, integration of sustainability literacy into formal curricula, and dissemination of context-specific information that links energy-saving actions to tangible environmental benefits. Concurrently, normative reinforcement via community-based programmes and peer-comparison feedback can augment social pressure for compliance. While attitudes and perceived control exhibit favourable baselines, their latent potential must be activated through contextual nudges and incentive structures that translate intention into habitual practice. Ultimately, the findings underscore that technological retrofits alone cannot deliver optimal energy outcomes; behavioural interventions grounded in psychological theory and empirical evidence are indispensable for bridging the performance gap and achieving long-term sustainability objectives.

The findings are broadly consistent with previous research that emphasises the importance of environmental awareness and normative influences in shaping pro-environmental behaviour [2,11,14]. Similarly to studies applying the Theory of Planned Behaviour, attitudes and perceived behavioural control were positive but did not significantly predict intention without strong awareness cues [20,35,36,37]. This supports evidence that intention mediates behaviour and highlights the role of informational interventions. However, the relatively modest effect of subjective norms observed in this study contrasts with findings from European contexts, where social norms exert stronger influence on household energy practices [14]. This difference may reflect cultural variations in collective environmental expectations and suggests that normative reinforcement strategies may be particularly necessary in Australian settings.

International comparisons reveal that the modest effect of subjective norms observed in this study aligns with findings from European research, where normative pressures are generally stronger and more influential in shaping pro-environmental behaviour. For example, studies in the Netherlands and Germany report higher OSN scores, attributed to well-established sustainability norms and community-driven initiatives. In contrast, Australian households exhibit weaker collective norms, which may explain the limited predictive power of OSN in our model. Sub-group analysis within our sample indicates that younger respondents (18–28 years) and apartment dwellers show slightly higher sensitivity to normative cues compared to older cohorts and those in freestanding houses. These insights suggest that normative interventions—such as peer-comparison feedback and community engagement programs—should be tailored to specific demographic segments to maximise impact.

The proportion of respondents with university degrees (approximately 50%) aligns with the socio-economic profile of Sydney’s metropolitan areas, which typically exhibit higher education levels compared to national averages [40]. This demographic characteristic may explain the generally positive attitudes and perceived behavioural control observed, consistent with literature linking education to sustainability awareness [37].

Overall, while the results corroborate global evidence on the primacy of awareness and intention, they reveal context-specific gaps in normative influence and highlight the need for tailored interventions in Australian residential contexts.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that achieving meaningful reductions in energy demand and carbon emissions within the residential sector requires a paradigm shift from technology-centric approaches to integrated behavioural frameworks. The empirical evidence confirms that occupant behaviour is not a residual variable but a primary determinant of energy performance, exerting influence comparable to, and often exceeding, that of physical building attributes. By operationalising the Theory of Planned Behaviour and extending it through the inclusion of environmental awareness, this study provides a validated and reliable model capable of predicting and explaining pro-environmental actions in domestic settings.

The statistical analysis reveals a pronounced hierarchy among behavioural constructs. Environmental awareness emerged as the most significant predictor of intention, with a coefficient magnitude that decisively outstripped attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioural control. This finding underscores the inadequacy of interventions that rely solely on attitudinal change or technical retrofits, highlighting the necessity of strategies that elevate ecological literacy and embed sustainability norms within social structures. The strong correlation between intention and actual behaviour validates the mediating role of intention, yet the persistence of an intention–behaviour gap indicates that motivational alignment alone is insufficient to guarantee behavioural execution. Bridging this gap demands systemic mechanisms—such as real-time feedback, social benchmarking, and incentive frameworks—that convert cognitive predispositions into habitual practices.

From a policy and design perspective, these insights call for a recalibration of energy governance strategies. Prescriptive building codes and technological upgrades must be complemented by behavioural interventions that prioritise awareness amplification and normative reinforcement. Educational campaigns, community engagement programs, and digital platforms delivering personalised energy feedback represent practical avenues for operationalising these behavioural levers. Such measures are integral—not optional—for closing the energy performance gap and accelerating progress toward national and global decarbonisation targets.

The validated framework offers a practical tool for predictive modelling and prescriptive planning, enabling stakeholders to quantify behavioural impacts and design interventions with precision. Future research should explore longitudinal and experimental studies to assess the durability of behavioural change and its interaction with technological retrofits under diverse socio-economic and climatic conditions. Integrating behavioural metrics into building performance simulation models will further enhance predictive accuracy and inform holistic design strategies.

In conclusion, this study advances the discourse on sustainable housing by demonstrating that behavioural determinants are neither peripheral nor immutable but constitute actionable levers for systemic transformation. By embedding behavioural science within the architecture of energy policy and building design, the residential sector can transition from incremental improvements to transformative change, delivering measurable reductions in energy consumption and carbon emissions while safeguarding thermal comfort and occupant well-being.

Author Contributions

Methodology, C.F. and H.F.; Software, C.F.; Validation, C.F. and H.F.; Formal analysis, C.F.; Investigation, C.F. and H.F.; Resources, C.F.; Data curation, C.F. and H.F.; Writing—original draft, C.F.; Writing—review & editing, C.F. and H.F.; Visualisation, C.F.; Supervision, H.F.; Project administration, C.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- ASBEC. Low Carbon, High Performance: How Buildings Can Make a Major Contribution to Australia’s Emissions and Productivity Goals; Australian Sustainable Built Environment Council: Sydney, Australia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen, R.K. The influence of occupant behaviour on energy consumption investigated in 290 identical dwellings and in 35 apartments. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Healthy Buildings, Brisbane, Australia, 8–12 July 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, N.; Standeven, M. A behavioural approach to thermal comfort assessment. Int. J. Sol. Energy 1997, 19, 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belafi, Z.; Reith, A. Interdisciplinary survey to investigate energy related occupant behaviour in offices—The Hungarian case. Int. J. Eng. Inf. Sci. 2018, 13, 41–52. [Google Scholar]

- Albatici, R.; Gadotti, A.; Baldessari, C.; Chiogna, M. A Decision Making Tool for a Comprehensive Evaluation of Building Retrofitting Actions at the Regional Scale. Sustainability 2016, 8, 990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahren, C.; Griffiths, P.; Michael, M. State of the Irish Housing Stock—Modelling the Heat Losses of Ireland’s Existing Detached Rural Housing Stock & Estimating the Benefit of Thermal Retrofit Measures on This Stock. Energy Policy 2013, 55, 139–151. [Google Scholar]

- Ahn, B.; Kim, J.; Jang, C.; Leigh, S.; Jeong, H. Window Retrofit Strategy for Energy Saving in Existing Residences with Different Thermal Characteristics and Window Sizes. Build. Serv. Eng. Res. Technol. 2016, 37, 18–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertone, E.; Stewart, R.; Sahin, O.; Alam, M.; Zou, P.; Buntine, C.; Marshall, C. Guidelines, barriers and strategies for energy and water retrofits of public buildings. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 174, 1064–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertone, E.; Sahin, O.; Stewart, R.; Zou, P.; Alam, M.; Blaire, E. State-of-the-Art Review Revealing a Roadmap for Public Building Water and Energy Efficiency Retrofit Projects. Int. J. Sustain. Built Environ. 2016, 5, 526–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Far, C.; Far, H. Improving energy efficiency of existing residential buildings using effective thermal retrofit of building envelope. Indoor Built Environ. 2019, 28, 744–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Far, C.; Ahmed, I.; MacKee, J. Significance of Occupant Behaviour on the Energy Performance Gap in Residential Buildings. Architecture 2022, 2, 424–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alev, U.; Eskola, L.; Arumagi, E.; Jokisalo, J.; Donarelli, A.; Siren, K.; Brostrom, T.; Kalamees, T. Renovation Alternatives to Improve Energy Performance of Historic Rural Houses in the Baltic Sea Region. Energy Build. 2014, 77, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.; Sanjayan, J.; Zou, B.; Ramakishnan, S.; Wilson, J. A Comparative Study on the Effectiveness of Passive and Free Cooling Application Methods of Phase Change Materials for Energy Efficient Retrofitting in Residential Buildings. In Proceedings of the International High-Performance Built Environment Conference, Hong Kong, China, 5–7 June 2017; pp. 993–1002. [Google Scholar]

- Bicchieri, C. The Grammar of Society: The Nature and Dynamics of Social Norms; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, S.; Castano, E.; Allen, D. Conservatism and concern for the environment. Q. J. Ideol. 2007, 30, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. The prediction of behavioural intentions in a choice situation. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1969, 5, 400–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. Attitudinal vs. normative messages: An investigation of the differential effects of persuasive communications on behaviours. Sociometry 1971, 34, 263–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I.; Madden, J. Prediction of goal-directed behaviour: Attitudes, intentions, and perceived behavioural control. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 22, 45–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. Attitudes, Personality, and Behaviours; Open University Press: Milton Keynes, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behaviour. Organ. Behav. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. The influence of attitudes on behavior. In The Handbook of Attitudes; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers: Mahwah, USA, 2005; pp. 173–221. [Google Scholar]

- Far, H.; Far, C. Experimental investigation on creep behaviour of composite sandwich panels constructed from polystyrene/cement-mixed cores and thin cement sheet facings. Aust. J. Struct. Eng. 2019, 20, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Far, H.; Far, C. Timber Portal Frames vs. Timber Truss-Based Systems for Residential Buildings. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2019, 2019, 9047679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I.; Timko, C. Correspondence between health attitudes and behaviour. J. Basic Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 7, 25–276. [Google Scholar]

- Crowther, D.; Lancaster, G. Research Methods: A Concise Introduction to Research in Management and Business Consultancy; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Far, H. Flexural Behavior of Cold-Formed Steel-Timber Composite Flooring Systems. J. Struct. Eng. 2020, 146, 06020003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Far, H. Seismic behaviour of high-rise frame-core tube structures considering dynamic soil–structure interaction. Bull. Earthq. Eng. 2022, 20, 5073–5105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karki, D.; Al-Hunaity, S.; Far, H.; Saleh, A. Composite connections between CFS beams and plywood panels for flooring systems: Testing and analysis. Structures 2022, 40, 771–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobhi, P.; Far, H. Impact of structural pounding on structural behaviour of adjacent buildings considering dynamic soil-structure interaction. Bull. Earthq. Eng. 2022, 20, 3515–3547. [Google Scholar]

- Haydar, H.; Far, H.; Saleh, A. Portal steel trusses vs. portal steel frames for long-span industrial buildings. Steel Constr. 2018, 11, 205–217. [Google Scholar]

- Tharenou, P.; Donohue, R.; Cooper, B. Management Research Methods; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, H. Creative Research: The Theory and Practice of Research for the Creative Industries; AVA Publications: West Sussex, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, J. Essentials of Business Research: A Guide to Doing Your Research Project; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Andrew, P.S.; Pedersen, P.M.; McEvoy, C.D. Research Methods and Designs in Sport Management; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behaviour: An Introduction to Theory and Research; Addison-Wesley: Boston, MA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Blok, V.; Wesselink, R.; Studynka, O.; Kemp, R. Encouraging sustainability in the workplace: A survey on the pro-environmental behaviour of university employees. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 52, 960–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leeuw, A.; Valois, P.; Ajzen, I.; Schmidt, P. Using the theory of planned behaviour to identify key beliefs underlying pro-environmental behaviour in high-school students. J. Environ. Psychol. 2015, 42, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidsen, A.S. Phenomenological approaches in psychology and health sciences. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2013, 10, 318–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dillman, D.A.; Smyth, J.D.; Christian, L.M. Internet, Mail and Mixed-Mode Surveys: The Tailored Design Method; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). Census QuickStats—Australia. 2020. Available online: https://abs.gov.au/census/find-census-data/quickstats/2021/POA2020 (accessed on 16 December 2025).

- Barlett, J.E.; Kotrlik, J.W.; Higgins, C.C. Organizational research: Determining appropriate sample size in survey research. Inf. Technol. Learn. Perform. J. 2001, 19, 43–50. [Google Scholar]

- Fleiss, J.L.; Levin, B.; Paik, M.C. Statistical Methods for Rates and Proportions; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Fowler, F.J. Survey Research Methods; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Holland, S.M. Principal Component Analysis; University of Georgia: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis-Beck, M.S. Applied Regression: An Introduction; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Anderson, R.; Tatham, R.L.; Black, W.C. Multivariate Data Analysis; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Pimentel, J.L. A note on the usage of Likert scaling for research data analysis. USM RD J. 2010, 18, 109–112. [Google Scholar]

- Hodson, G. Construct Jangle or Construct Mangle? Thinking Straight about Psychological Constructs. J. Theor. Soc. Psychol. 2021, 5, 576–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.