Abstract

This paper presents a PRISMA-ScR scoping review of 20 digital maturity assessment tools in the architecture, engineering, and construction (AEC) sector and wider business domains. The objective is to compare key features including assessment matrices, maturity dimensions, completion time, accessibility, and platform availability. The review follows predefined eligibility criteria and a structured screening process to identify and analyse tool frameworks in terms of scope, metrics, platform type, usability, and focus areas. Most tools primarily target the AEC sector, while some address broader organisational digital transformation. Common maturity areas include technology, organisation, data management, and processes. The analysis highlights limitations such as underemphasis on people, strategy, policy, skills development, standards, and financial resources, as well as the fragmented integration of maturity components. A combined bottom-up (scoring) and top-down (dimension structuring) approach is recommended for future tool development. The review provides insights for practitioners when selecting tools and proposes guidelines for creating more comprehensive and integrated maturity models.

1. Introduction

Digital transformation (DT) is essential for businesses of all sizes, allowing a rapid evaluation of the processes, competencies, tools and practices [1], to address the increasing demands of partners, employees and customers [2]. This transformation is enabled by integrating digital technologies such as cloud computing, big data, social media, and mobile internet [3], driving industries to innovate and create new business models [4] and involves a transition by integrating new technologies into current business models. Digitalisation has accelerated industry advancement by enhancing connectivity, speed and manageability, simplifying access to critical data and essential information [5]. Organisations embracing digitalisation can significantly enhance their competitiveness, while those delaying adoption often find maintaining profitability to be challenging [6,7].

A major challenge in today’s global economy is fostering innovation and implementing digital initiatives within businesses [8]. It is essential to acknowledge the critical role of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in this context [9]. According to Akinsola [10], drawing on World Bank Group data, SMEs generate “more than half of all formal jobs worldwide and offer effective solutions to crucial development challenges”. SMEs play an important role in the global economy and have the potential to contribute substantially to global economic growth through digital endeavours. It would be prudent for organisations to evaluate their existing capabilities and anticipated needs to ascertain their digital maturity prior to initiating novel digital ventures, including services, tools, and processes [11]. Digitalisation has played a transformative role in the construction industry, evolving it from a traditionally fragmented ecosystem into a more integrated and collaborative environment [11]. A key enabler of this shift is building information modelling (BIM), which facilitates streamlined and structured information exchanges among diverse stakeholders throughout a project lifecycle. Rather than merely improving data access, BIM supports real-time collaboration, clash detection, lifecycle asset management, and decision-making processes, functions that are critical in the context of digital maturity [12,13]. As such, BIM maturity is often used as a proxy indicator for overall digital maturity in construction firms. However, despite its importance, many digital maturity assessment tools either inadequately address BIM-specific capabilities or incorporate them only superficially [14,15]. This highlights a crucial gap in existing evaluation frameworks, particularly in aligning digital maturity with BIM implementation readiness and effectiveness. This emphasis on BIM reflects the broader evolution of digitalisation in the construction industry from isolated applications to IT-driven, collaborative frameworks that require organisation-wide adoption [16]. Consequently, the challenges of BIM implementation have also evolved, shifting from purely technical issues to continuous process integration and change management [17,18,19]. In this context, evaluating an organisation’s digital maturity becomes critical for digital transformation leaders and industry stakeholders to identify appropriate improvement pathways [20].

Despite the increasing number of digital maturity assessment tools available to construction organisations, the landscape remains highly fragmented: tools differ in scope, maturity dimensions, assessment criteria, granularity, and evidence requirements [21]. Prior reviews of digital maturity tools across various sectors report promising progress [22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30], yet the knowledge remains dispersed and difficult for practitioners to apply. The construction sector in particular lacks a consolidated understanding of how existing tools cover critical dimensions such as people, processes, culture, policy, data governance, and training. These gaps create challenges for industry stakeholders who must select an appropriate tool, interpret scores, and translate results into actionable improvement plans. Accordingly, this study addresses a clear industry and research need by systematically evaluating 20 digital maturity assessment tools—developed by academia and industry and which are government-backed—to determine their suitability for the AEC sector. The review analyses each tool against multiple criteria, including maturity dimensions, evaluation matrices, assessment questions, accessibility, and platform type, offering a structured comparison that clarifies current strengths, limitations, and areas requiring enhancement. To guide this investigation, the study addresses the following research questions:

RQ1:

How comprehensively do existing digital maturity assessment tools cover the technological, organisational, people-centric, cultural, and governance dimensions relevant to AEC digitalisation?

RQ2:

What limitations and gaps exist within current tools, and how can these insights inform the development of an improved, industry-appropriate digital maturity framework for the AEC sector?

By answering these questions, the study provides a theoretically grounded and practice-oriented foundation that assists organisations in selecting suitable tools, interpreting maturity results, and planning structured digital transformation pathways tailored to construction sector priorities.

2. Background

DT has redefined how organisations design processes, develop competencies, and make strategic decisions, moving far beyond the adoption of discrete technologies. Foundational reviews define DT as a multilevel organisational change process in which digital technologies reshape structures, workflows, and performance outcomes [1], while large-scale management studies emphasize that leadership, strategy, and organisational agility, not technology alone, are decisive determinants of digital maturity [31]. In parallel, general maturity model theory provides important scaffolding. Early models such as the capability maturity model (CMM) conceptualized maturity as staged organisational progression, linking process formalization to predictable performance outcomes [32]. More contemporary digital transformation and information systems maturity frameworks, such as the state-of-the-art synthesis of maturity models for information systems by Proença and Borbinha [33] and Teece’s dynamic capabilities perspective [34], highlight that digital maturity emerges from a combination of technology, organisational capabilities, learning capacity, governance, culture, and strategic alignment. These wider theories reinforce the idea that digitalisation cannot be evaluated solely through technical indicators but must incorporate people, processes, culture, and governance.

In the construction industry, these cross-sector principles are complicated by structural fragmentation, multi-stakeholder coordination needs, and lifecycle information flows. As a result, assessing an organisation’s “digital maturity” becomes a practical prerequisite for structured improvement. Within the AEC sector, BIM has become a central mechanism of digitalisation because it operates on information management across design, delivery, and asset operations. BIM literature demonstrates how common data environments, model-based coordination, and standardised information exchanges generate measurable gains in collaboration, efficiency, and downstream asset performance [12].

Consequently, many organisations use BIM capability or maturity as a leading proxy for broader digital readiness. However, existing BIM tools vary widely: some emphasize the technological implementation or model quality, whereas people-centred, cultural, and governance aspects remain underdeveloped. Cross-industry research reinforces these observations. A comprehensive systematic scoping review spanning manufacturing, IT, public administration, and AEC sectors [35] shows that maturity frameworks consistently converge around multidimensional constructs encompassing technology, processes, people, culture, leadership, strategy, and data governance. This cross-sector evidence positions digital maturity as an organisational capability system rather than a technology-centric phenomenon, strengthening the rationale for balanced assessment structures that extend beyond BIM implementation alone. Building on these broader insights, seminal BIM-focused work introduced maturity constructs and matrix linking stages, competency sets, and organisational scales, establishing a research tradition for measuring progress and planning capability development [16,36]. Complementary frameworks emphasize role-specific competencies, professional development, and organisational learning [20], while enterprise-level digitalisation studies now incorporate dimensions validated in construction firms to assess digital transformation progress beyond BIM alone [37].

Despite these advances, comparative evaluations highlight substantial variation in scope, granularity, and evidence requirements. Tools range from rapid scans and checklists to comprehensive, multi-layered matrices with detailed subdimensions and staged descriptors [22,38]. These discrepancies mirror patterns observed in other industries, where maturity assessments increasingly incorporate multidimensional perspectives technology, processes, organisation, culture, and governance to prevent overemphasis on technological factors while underrepresenting people, leadership, and strategy. For the AEC specifically, recent reviews point to persistent gaps in standards alignment [39], coverage of lifecycle stages beyond design and construction, and explicit treatment of data governance, security, interoperability/compliance checking, and financial or procurement considerations. These limitations motivate more integrated assessment designs that combine bottom-up scoring (granular, auditable indicators) with top-down structuring anchored in recognised information management standards, strategic objectives, and organisational capability theory. The comparative analysis in our review reflects these trends, revealing uneven coverage across technology, organisation/management, data and processes, and, especially, the limited treatment of culture, skills/training, policy, governance, and finance, all of which are essential for sustained and scalable digital adoption.

Against this backdrop, using BIM maturity as a conceptual foundation becomes justified not because BIM alone defines digital transformation, but because BIM acts as the information backbone of AEC digitalisation. BIM-based workflows require integration across technology, people, processes, standards, and governance, therefore offering a practical entry point for operationalizing broader DT principles. This study further strengthens the theoretical base by grounding its maturity structure in (i) cross-industry DT frameworks, (ii) dynamic capabilities and organisational learning theory, (iii) established capability/maturity model logic, and (iv) ISO 19650-oriented information management principles [40]. The 11-dimension structure adopted in this research emerges from a systematic synthesis of existing BIM and DT maturity tools (20 tools reviewed), mapping overlaps and gaps, clustering recurring organisational themes, and integrating constructs drawn from digital capability literature. This process provides the theoretical derivation logic that underpins the dimensions used in the proposed toolkit. The dimensions were subsequently confirmed and refined through alpha and beta testing activities reported later in this paper.

Accordingly, this study positions digital maturity assessment as both a diagnostic mechanism and a planning instrument. By triangulating insights from BIM maturity research, organisational capability theory, and cross-industry DT frameworks, the study advances evaluation criteria that (i) reflect staged improvement pathways; (ii) incorporate auditable and role-aware indicators; (iii) expand coverage into people, culture, governance, and finance; and (iv) align with standards-based lifecycle information management. This integrative positioning situates the study at the intersection of general digital transformation theory and construction-specific digital practice, providing a theoretically anchored and practically applicable foundation for developing a comprehensive BIM-enabled digital maturity toolkit that addresses long-standing gaps in existing models [1,22,31].

3. Methodology

3.1. Methodology for Tools Selection

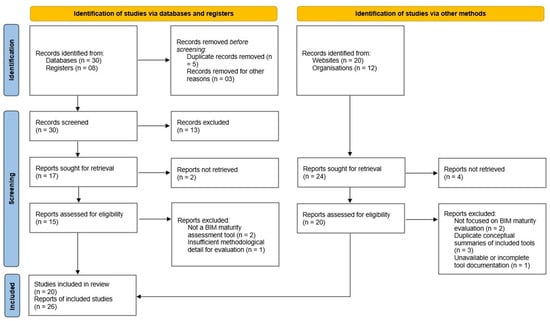

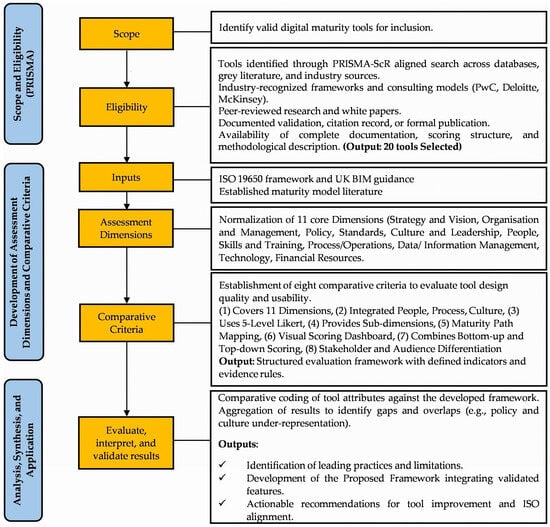

This review is reported with reference to the PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR) as a reporting framework. An internal protocol document was compiled to document the objectives, eligibility criteria, search strategy, and coding procedures and to ensure transparent reporting aligned with PRISMA-ScR. As the database searches and initial screening had already been completed when the protocol was drafted, it was not prospectively registered and should be interpreted as a retrospective documentation of the methods applied, rather than a preregistered protocol or pre-analysis plan. A completed PRISMA-ScR checklist is provided in Supplementary Material S1. The identification, screening, and eligibility stages are summarized in the PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1), while the three-phase methodological framework (Figure 2) operationalizes this protocol, with Phase 1 corresponding to these stages. As the protocol was developed retrospectively, this review should be interpreted as PRISMA-ScR-aligned reporting of the selection process rather than evidence of prospective protocol registration. Data screening, coding, and descriptive analyses were performed using Microsoft Excel 365 (Version 2511).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram for study selection.

Figure 2.

Three-phased methodological framework for tools (PRISMA) and criteria selection.

3.1.1. Information Sources and Search Dates

Information sources included both academic databases and grey literature repositories. Peer-reviewed publications were identified through Scopus, Web of Science and Google Scholar, complemented by targeted searches of publisher platforms (Elsevier, ASCE, Taylor and Francis, IEEE Xplore). Grey literature and industry tools were located via the websites of international consultancies and professional bodies (e.g., Boston Consulting Group, Deloitte, McKinsey, TM Forum, European Commission, NIBS, CIFE Stanford) and via general web searches.

The database searches covered material published from 2007 to 2022, reflecting the period during which most BIM and digital maturity tools emerged, as explained in Section 5.3. Only documents available in English were included. The final search and screening update was completed in August 2023.

3.1.2. Search Strategy

Search strings combined three concept blocks: (1) digital maturity and capability models, (2) BIM/construction/AEC, and (3) assessment or evaluation tools. Typical database queries were in the following form:

“Digital maturity” OR “digital transformation” OR “maturity model” OR “maturity assessment”.

AND “BIM” OR “building information modelling” OR “construction” OR “AEC” OR “built environment”.

AND “assessment” OR “framework” OR “scorecard” OR “index” OR “tool”.

Boolean operators and field limits were adapted to each database. For web and organisational searches, similar keyword combinations were applied (e.g., “digital maturity index construction”, “BIM maturity assessment tool”), and backward/forward citation chasing was used on key publications to identify additional tools. All identified records were exported to a reference manager and spreadsheet for de-duplication and screening.

3.1.3. Inclusion Exclusion (Eligibility) Criteria

Inclusion Criteria

The research initially identifies the digital maturity assessment tools to be analysed by applying selection criteria to identify a representative sample of leading tools. A representative sample of tools was selected using five screening criteria derived from previous studies [14,15] and industry best practices such as PwC, Deloitte, and McKinsey. These criteria ensured that the selected tools were relevant, well documented, and had demonstrable impact:

- Industry Recognition: A tool qualified if at least one of the following held:

- Official release or sponsorship by a public authority/standards body (e.g., the European Commission’s Maturity Scan; NIBS’s NBIMS-CMM).

- Documented deployments/validation in practice (e.g., Stanford CIFE’s VDC BIM Scorecard used and validated on real projects; BIM Compass used for national benchmarking); or

- Commercial roll-out by a tier-1 consultancy with client deployments (e.g., BCG’s Digital Acceleration Index; McKinsey’s Digital Quotient).

- Availability of Detailed Literature: Each included tool had at least one primary source (peer-reviewed article, standards/technical document, or an official white paper/user guide) that discloses scope, structure, and scoring so methods are auditable (e.g., BIM-CAREM in Computers in Industry 2019/2023; BIM-MM in IGI Global 2010; BIM Cloud Score in ASCE J. Constr. Eng. Manage.; VDC BIM Scorecard in the CIFE technical report; TM Forum/Deloitte DMM in TMF documentation; BCG DAI and McKinsey DQ on official portals). Tools lacking primary source were excluded.

- Reputable Development and Support: Tools developed by universities, international consultants, or government bodies were selected to ensure legitimacy, methodological rigor, and continued maintenance.

- Distinctive Features: Tools had to demonstrate a unique approach such as multi-dimensional assessment, BIM integration, or benchmarking capability that justified their inclusion in a comparative review.

- Citation and Recognition: Preference was given to tools that had been cited in academic literature or professional reports, indicating impact and acceptance by the research and practitioner communities.

Exclusion Criteria

- Conceptual articles on digital transformation that did not provide a maturity tool or scoring method.

- Studies focused solely on technology adoption, predictive modelling or standard project performance metrics without a maturity construct.

- General digital readiness or IT governance models with no clear application to AEC or BIM.

- Marketing leaflets or webpages lacking methodological detail on dimensions, scales or scoring.

- Non-English sources or tools for which full documentation was unavailable or inaccessible.

These criteria were applied through a structured screening process to ensure a balanced mix of tools across geographic regions, development origins (academic, industry, government), and application scopes. As a result, 20 tools were selected that reflect both diversity and methodological robustness, forming a sound basis for comparative analysis. The detailed characteristics and supporting references for each tool are presented in Appendix A.1.

Moreover, the study selection process is reported using the PRISMA-ScR flow structure summarized in Figure 1. Database and register searches yielded 38 records (30 from databases and 8 from registers). After removing duplicates (n = 5) and records excluded for other reasons (n = 3), 30 records were screened by title and abstract, of which 13 were excluded as not meeting the basic maturity tool criteria. Full texts were sought for 17 records, of which two could not be retrieved, leaving 15 reports assessed for eligibility. Of these, three were excluded (two were not BIM/digital maturity tools, one lacked sufficient methodological detail), resulting in twelve tools from academic and formal sources.

Searches via websites and other organisational sources identified an additional 32 records (20 from general websites and 12 from organisational portals). Full-text retrieval was attempted for 24 records, of which 4 could not be retrieved. The remaining 20 reports were assessed for eligibility, of which 6 were excluded (2 were not focused on BIM/digital maturity evaluation, 3 were duplicate conceptual summaries of tools already included, 1 with incomplete documentation). This process yielded eight additional tools. In total, 20 distinct digital maturity tools and 26 supporting reports were included in the review, consistent with the counts reported in the PRISMA diagram (Figure 1). A detailed breakdown of the search operations, including per-database query strings, date limits, hit counts, and exported records, is provided in Supplementary Table S2.

3.1.4. Screening Reliability and Data Extraction

To enhance the reliability, screening was conducted using the same application of eligibility criteria across both stages. Any uncertainties were addressed through discussion within the research team and by consulting the underlying tool documentation when needed. Formal kappa statistics were not calculated; however, consensus was reached for all included and excluded records, and any uncertainties were documented in the screening log. This independent review process reduces the risk of selection bias relative to a single-coder approach, although the absence of formal inter-rater coefficients is acknowledged as a limitation [41].

For each included tool, data were extracted into a structured spreadsheet capturing tool provenance and audience, underlying documentation, dimensional coverage, scoring method, scale type, visualisation features, and evidence of validation or deployment. These data formed the basis for the subsequent coding procedures described in Section 3.2.2 and Section 3.2.3, informed the coverage analysis presented in Section 5.5, and supported the comparative criteria discussed in Section 6.3. For transparency and reproducibility, the complete coding dataset (tool-by-dimension and tool-by-criteria matrices) is provided in Supplementary Material S3 (coding data), with the associated codebook definitions in S4 (codebook definitions) and the tools inventory with source links in S5 (tools inventory).

3.2. Methodology for Criteria Selection

The criteria framework was developed into two layers. First, a set of coverage dimensions was assembled to characterise the scope of each digital maturity tool (Section 5.5, Appendix A.2). Second, a set of comparative features was defined to evaluate design and usability across tools (Section 6.3). Both layers were derived through evidence mapping of peer-reviewed BIM maturity research, digital transformation scholarship, and information management standards, followed by normalization and a conservative coding protocol.

3.2.1. Development of Assessment Dimensions

Primary dimensions were collected from the following:

- Foundational BIM maturity work that specifies stages, competency sets, and hierarchical scales, establishing the need for balanced, multi-domain assessment [36] and the BIM Maturity Matrix articulation of levels and granularity [16].

- Digital transformation literature emphasising strategy, leadership, culture, and organisational capabilities beyond technology [1].

- BIM information management standards and role definitions that anchor governance, responsibilities, and lifecycle information flows [39,40].

- Competency frameworks translating maturity into role-level capabilities for owners and delivery organisations [20].

Concepts extracted from these sources were clustered and de-duplicated to a stable set of 11 dimensions reflecting socio-technical views such as strategy and vision; organisation and management, policy; standards, culture and leadership; people, skills and training; process/operations; data and information management technology; and financial resources. The integration of policies and standards is based on the ISO 19650 framework, which outlines roles, responsibilities, and information requirements [31]. Emphasis on people, process, culture, and skills follows BIM adoption studies that identify collaboration, learning, and organisational readiness as persistent determinants of success [42]. These need to consider finance/resources in alignment with digital transformation reviews that highlight investment capacity and resource orchestration as maturity constraints [1].

3.2.2. Coding Framework and Criteria for Identifying Maturity Dimensions

To ensure a consistent and transparent evaluation of the selected tools, a structured coding framework was applied to determine whether each maturity dimension was genuinely assessed within a tool. This framework standardised interpretation across diverse tool formats, including questionnaires, maturity matrices, narrative models and benchmarking scorecards.

A dimension qualified as present when both of the following conditions were met:

- Visible structural definition of the dimension, such as a named domain, an equivalent thematic cluster, or at least three distinct indicators that explicitly mapped to that domain; and

- Explicit measurement, demonstrated through scored questions, maturity level descriptors, structured rubrics or documented weighting schemes. Unscored mentions or general statements were treated as contextual background rather than evidence of assessment.

Moreover, a dimension was marked as present only when the primary source explicitly defined indicators or evaluation content that mapped unambiguously to the normalized definitions (e.g., role-bound information requirements → “Standards”; competency/skills rubrics → “Skills and Training”). Ambiguity was resolved by cross-checking at least one additional primary or standards source, while absence of clear evidence resulted in a blank. To maintain reliability, comparable thresholds were applied across all domains. For example, the ‘People’ domain required measurement across at least two human-centred subthemes (e.g., user engagement, cultural readiness, digital skills, leadership support), supported by a minimum of three scored items or equivalent maturity descriptors. Similarly, ‘Policy and Governance’ required evidence of assessment across areas such as standards compliance, legal or contractual arrangements, information security or procurement alignment. ‘Technology’ required structured evaluation of infrastructure readiness, interoperability or integration, platform capability or innovation readiness, while ‘Process/Operations’ require defined workflows, process control or standardisation. ‘Data and Information Management’ required explicit assessment of data quality, metadata structures or lifecycle information flow. ‘Strategy, culture’ and ‘Skills and Finance’ were coded only when domain-specific descriptors or multiple scored items were present. Different tool formats were coded using parallel logic: for questionnaire-based tools, item counts referred to scored questions, while for narrative frameworks, a domain was recognised only if maturity descriptors were present across multiple levels or if explicit weighting was applied. Composite questions spanning multiple domains were disaggregated only when the scoring allowed clear attribution. This coding framework ensured consistency across the review and enabled fair comparison between tools with varied structures and levels of detail. It also addressed ambiguity by verifying each coding decision against at least one additional primary source to minimise misinterpretation. This approach provided a robust empirical basis for the comparative analysis presented in later sections.

3.2.3. Development of Comparative Evaluation Criteria

The comparative evaluation criteria were established to ensure that the selected digital maturity assessment tools could be compared not only with their technical coverage but also with their design robustness, interpretability, and practical usability. The purpose was to identify structural and functional qualities that differentiate comprehensive, evidence-based tools from those limited to descriptive assessments. For this purpose, the criteria were synthesized from maturity model design theory, which defines a tool’s value in terms of clarity of progression, measurement transparency, and actionable insight, which are core characteristics of credible benchmarking tools [1,43]. Comparative attributes were therefore chosen to capture both measurement structure and user-oriented functionality. This dual focus aligns with established evaluation practices in BIM and digital maturity reviews [18,37]. The rationale for selection of the eight criteria is explained below.

- Eleven Dimensions: To ensure methodological consistency and representativeness, a detailed content analysis of existing BIM and digital maturity frameworks was undertaken prior to defining this criterion. The analysis compared recurrent constructs across international standards (ISO 19650) and benchmark models such as the Maturity Scan, BIM Maturity Matrix, BIM Quick Scan, and VDC Scorecard. Through iterative synthesis, overlapping themes were consolidated to avoid redundancy, resulting in a stable set of eleven key maturity dimensions. This number reflects a balanced and comprehensive structure that captures all critical socio-technical aspects spanning strategy, organisation, technology, people, process, and governance without unnecessary fragmentation. The inclusion of eleven dimensions aligns with findings from established maturity matrix research, which emphasizes complete yet manageable domain coverage to ensure meaningful benchmarking [39,40]. The complete list and criteria for selecting these dimensions are explained in Section 5.5.

- Integrated Assessment of People, Process and Culture: Inclusion of this triad acknowledges the centrality of behavioural and cultural transformation within digital adoption, emphasized by leadership-driven models [31].

- Uses five-level Likert Scale: A five-point Likert scale is widely used in maturity models for its statistical stability and interpretive consistency [44].

- Subdimensions: Explicit subdimensions allow transparent traceability between qualitative indicators and quantitative scores, ensuring the model’s auditability and internal validity.

- Maturity Path Mapping: The presence of a staged or roadmap-like structure that makes improvement trajectories explicit. The construction is consistent with staged capability models (e.g., CMMI) and BIM-specific maturity matrices that articulate levels and pathways [36,45]. Tools were credited only when stages/levels were explicitly defined and linked to progress guidance.

- Visual Scoring Dashboard: Availability of a results interface (e.g., scorecards, radar charts, dashboards) that communicates scores to different audiences. Justification derives from visual management research in construction showing dashboards improve transparency and decision-making [46] and recent reviews on visual dashboards for performance monitoring [47].

- Combines Bottom-up and Top-down Scoring: Evidence that granular indicator scores (bottom-up) are aggregated to higher-level dimensions or strategic objectives (top-down) using an explicit schema. The logic follows hierarchical evaluation in maturity and multi-criteria decision frameworks where local measures roll up to composite judgments [48] and staged/continuous capability representations [45].

- Stakeholder and Audience Differentiation: Support for role-specific views, responsibilities, or outputs (e.g., owners, project teams, managers), aligned with role delineation in ISO 19650-based information management [39,40] and competency-based framing for different organisational actors [20].

A criterion was marked pass (✓) only when the feature was (i) explicitly stated in the tool’s primary documentation or peer-reviewed description, or (ii) operationally demonstrated in a method paper (e.g., a published scorecard, staged roadmap, or role-aware output). Where evidence was indirect or anecdotal, the attribute remained unmarked to maintain methodological rigor. This ensured that the comparative analysis reflects substantiated design features rather than interpretive assumptions.

The three-phased methodological framework is illustrated in Figure 2. This framework illustrates the systematic process adopted for identifying, evaluating, and synthesizing digital maturity assessment tools. In Phase 1 (tool identification and eligibility), the review followed the PRISMA guidelines to ensure transparency, reproducibility, and rigor. In this phase, candidate tools were screened using five predefined inclusion filters: industry recognition, authoritative publication source, availability of supporting literature, distinct feature set, and documented validation or citation record, as described in Section 3.1. The PRISMA-aligned screening process resulted in a curated selection of 20 tools drawn from consultancy models, peer-reviewed studies, and institutional frameworks. Phase 2 (development of assessment dimensions and comparative criteria) established the analytical foundation for comparison. Guided by ISO 19650 principles, UK BIM Framework guidance, and established maturity model literature [1,16], this phase normalized 11 core dimensions and formulated eight comparative criteria encompassing both design quality and usability factors, such as the use of five-point Likert scales, maturity path mapping, visual dashboards, and stakeholder differentiation, as explained in Section 6.3. The outcome was a structured evaluation matrix that enabled consistent cross-tool analysis. Phase 3 (analysis, synthesis, and application) focused on comparative evaluation and integration, identifying thematic gaps (e.g., underrepresentation of people, process, culture, and policy dimensions) and synthesizing the findings into a unified digital maturity evaluation framework aligned with ISO 19650. Iterative feedback loops ensured that findings from Phase 2 refined tool inclusion decisions, while Phase 3 outputs informed further validation, maintaining end-to-end traceability from evidence to recommendations.

4. Characteristics and Classification of Existing Digital Maturity Assessment Tools

Various tools have been developed to assess and improve the digital maturity of organisations. These tools are customised to the construction environment, leading to the use of distinct criteria and frameworks. The identified tools define assessment metrics such as key performance indicators (KPIs), critical success factors, criteria, fields, dimensions, subdimensions, evaluation aspects/areas, categories, and divisions. Robin and Yahya [49] identified five key dimensions for assessing an organisation’s digital maturity in the AEC sector such as technology, process, policy, people, and organisation. These dimensions are ranked in terms of their importance, with process and people rated as highly significant, whereas technology, policy, and organisation are considered moderately important. These dimensions can be further subdivided to capture specific aspects of digital transformation across AEC organisations.

Following the screening described in Section 3, the 20 selected tools were profiled using descriptive attributes such as source, developer, year, target sector, platform, accessibility and time required for completion. The consolidated profiles are provided in Appendix A. The selected tools span from 2007 to 2022 and reflect contributions from both academic institutions (e.g., Stanford, Cambridge, Hong Kong University) and industry stakeholders (e.g., McKinsey, BDO, Deloitte). The majority (65%) are designed specifically for the AEC sector, while others support broader industry applications. In terms of accessibility, tools range from freely available online platforms to proprietary or research-based systems requiring direct author contact. Some tools offer quick self-assessments that take 5–15 min, while others involve extensive evaluations requiring hours or even months. This diversity highlights varying levels of maturity evaluation complexity, technological integration, and stakeholder orientation, providing valuable insight into how digital readiness is measured across contexts. These tools form the basis for the comparative analysis as attached in Appendix A.2, which explores the maturity dimensions most frequently addressed across the reviewed frameworks. Section 5 presents a detailed discussion of these aspects to support stakeholders in selecting, implementing, and developing digital maturity tools that are aligned with industry needs.

5. Overall Analysis of the Selected Tools

This section presents an in-depth analysis of the 20 digital maturity assessment tools and their key characteristics. A summary of these tools, including their development year, source, platform, accessibility, and completion time, is provided in Appendix A.1. The comparative evaluation of maturity dimensions addressed by these tools is presented in Appendix A.2 and the linkage of these eleven maturity dimensions to the relevant ISO 19650 clauses are presented in Appendix A.3.

5.1. Origins of Tools

Both academic institutions and private organisations have facilitated the global dissemination of digital maturity assessment tools. Notably, the European Commission’s Maturity Scan [26] exemplifies this trend. Furthermore, prestigious universities, such as Cambridge, Stanford, and Carnegie Mellon have made valuable academic contributions by developing similar tools to enhance scholarly discourse. Consulting firms such as Boston Consulting Group and McKinsey facilitate collaboration between academia and industry. Tools such as BIM Compass [22], the European Commission’s Digital Maturity Assessment for Construction SMEs, BIM-MM [26,36], I-CMM [30] and VDC BIM Scorecard [50] are leading examples of digital maturity assessment tools for the AEC sector. The widespread global adoption of these tools highlights their international significance in enhancing standards and digital maturity across various sectors.

5.2. Target Sector

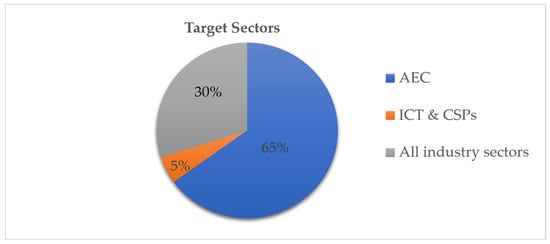

Figure 3 provides a visual overview of the target sectors with a subset of tools specifically designed for the AEC sector, by tailoring their criteria and structures to address industry-specific needs. These AEC specific tools aim to evaluate and enhance digital maturity in the context of construction projects. Most of the tools target the AEC sector (65%), with some addressing general business transformation across all industry sectors (30%), while a smaller proportion related to the information communication and technology (ICT) and communication service provider (CS) sectors (5%).

Figure 3.

Target sectors of the selected digital maturity assessment tools.

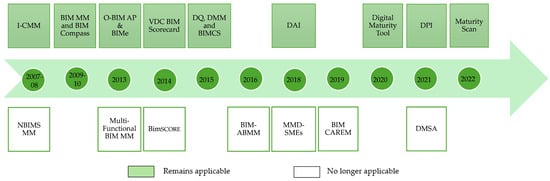

5.3. Evolution of the Tools (2007–2022)

Figure 4 presents a chronological timeline for the development of the reviewed tools. Thirteen out of twenty were developed before the publication of ISO 19650 in 2018, which is now widely recognised for guiding information management in BIM-enabled environments. Including the pre-2018 tools remain important for two reasons. First, several of them established the core constructs that still underpin digital maturity thinking in the AEC sector and they continue to be used or adapted in practice and academia. Examples include NBIMS-CMM, BIMe and BIM Compass. Second, these tools document the discipline’s shift from isolated capability checklists to integrated, lifecycle-oriented assessments. Reading them alongside post-2018 tools clarify how methods have matured over time and where legacy approaches need light recalibration to meet current expectations.

Figure 4.

Timeline of the development of selected digital maturity assessment tools.

A brief clarification of standards helps explain this continuity. ISO 19650 was developed from the UK BS/PAS 1192 series and internationalized its information management approach. The two families share the same conceptual backbone. Both emphasize clear information requirements across the asset and project lifecycle, the use of a common data environment for controlled information exchange, defined roles and responsibilities for producing and checking information, and the progressive development of models and documentation. The differences are mainly in scope and terminology rather than intent. ISO 19650 provides globally harmonized terms, a clearer split of responsibilities between the appointing party and appointed parties, updated process clauses that reflect collaborative delivery across borders, and extensions that reference contemporary concerns such as security-minded information management. In practice, BS/PAS-era concepts map cleanly to ISO 19650 language, so earlier maturity tools can be interpreted and, where needed, updated rather than discarded.

Between 2013 and 2016 there was a pronounced surge in the release of new frameworks, with nine introduced during this period. This reflects a period of rapid consolidation in the field, during which maturity models increasingly embedded structured principles from the BS/PAS 1192 series and expanded beyond technology- focused capability checks. Tools developed in this phase introduced more refined constructs such as information exchange quality, decision support mechanisms, data governance themes and competency-based assessments. This period therefore marks a transition from early, checklist-driven tools toward more holistic and methodologically robust frameworks.

Momentum continued after 2018 with the appearance of tools such as the Maturity Scan, the Digital Performance Indicator and the Digital Maturity Self-Assessment, which show a more explicit alignment with ISO 19650. Many of these newer tools incorporate cloud-based assessments, collaborative features, dashboard reporting and strategy-oriented outputs that reflect modern information management practices. Further growth followed 2020 with the release of several ISO aligned web platforms. These developments indicate a broader trend toward standardisation, digital delivery, and deeper organisational integration moving beyond BIM capability alone to encompass culture, leadership, governance and strategic readiness.

As shown, Figure 4 captures this fifteen-year progression and shows the increasing complexity of assessment, broader platform accessibility and stronger integration with BIM workflows. As standards and practices evolve, earlier tools remain useful baselines but may require contextual updates to terminology and evidence requirements so that evaluations remain fully effective. The mapping of earlier tools to ISO 19650 principles is further reflected in the framework proposed in Section 4 and Section 5.

5.4. Platform and Accessibility

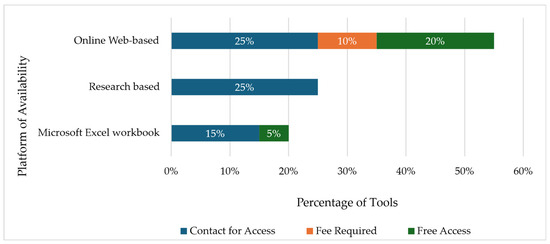

Figure 5 presents an integrated view of both the platform types and accessibility modes of the selected tools. The results show that 20% of the tools including OBAP [15,51], I-CMM [30], NBIMS-CMM [52] and BIM CAREM [53,54] are available as Microsoft Excel workbooks, reflecting the use of widely adopted spreadsheet environments for conducting digital maturity assessments. A further 25% of the tools, such as the Maturity Model of Digitisation for SMEs [24], Multifunctional BIM MM [28], BIM Action-Based Maturity Model [55], BIMCS [21], and VDC BIM Scorecard [50], are research-based, generally developed in academic contexts or specialist studies, often requiring domain expertise for implementation. The majority, accounting for 55%, are web-based tools, including Maturity Scan [26], Digital Performance Indicator [23], Digital Maturity Self-Assessment [55], Digital Maturity Tool [25,56], BimSCORE [57], DMM [58,59], Digital Acceleration Index [60], Digital Quotient [27], BIM Compass [22] BIMe [61] and BIM-MM [16,35], thereby reflecting the increasing trend to easy accessibility, collaboration, and real-time data management.

Figure 5.

Distribution of platform types and accessibility modes among selected digital maturity assessment tools.

In terms of accessibility, the figure shows that 65% of the tools require users to contact the developer for access, indicating that controlled or semi-restricted distribution remains the prevailing practice. Such restricted access suggests that much of the digital maturity landscape is shaped by proprietary mechanisms, customized consultancy models, and service-based ecosystems. While this approach enables developers to maintain quality oversight and ensure intended application, it also limits openness, hinders independent benchmarking, and reduces the potential for sector-wide standardisation. An additional 10% of tools require a fee, reflecting subscription-based or commercially licensed assessment models. However, a notable 25% of tools are freely accessible, removing financial and administrative barriers and enabling broader adoption across varied organisational contexts.

Taken together, the distribution of platform types and accessibility conditions underscores the technological diversity of existing maturity tools and the differing levels of openness that shape their uptake within the AEC sector. The predominance of web-based platforms, coupled with the restricted-access nature of most tools, highlights ongoing tensions between proprietary control and the need for wider, more standardized digital maturity benchmarking.

5.5. Dimensions

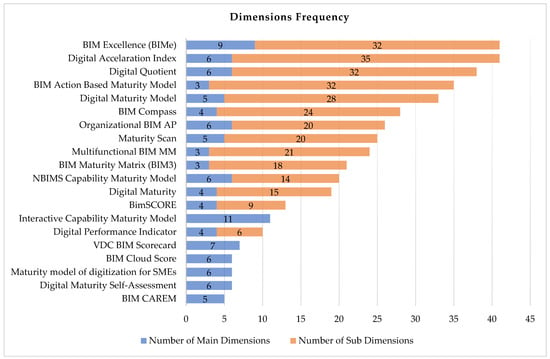

The dimensions or tiers signify key maturity areas [24]. Table 1 and Figure 6 analyse the dimensions assessed by various digital maturity tools across different organisational types, with particular emphasis on those applied within the AEC sector. Table 1 provides a simplified overview of the five most comprehensive tools, highlighting their dimensional coverage strengths and key gaps, while Figure 6 illustrates the total number of dimensions and subdimensions considered by each tool and presents a comparative analysis of the structural frameworks of various tools. This focuses on the number of main dimensions (blue bars) and subdimensions (orange bars). Tools, such as BIMe, Digital Acceleration Index and Digital Quotient, exhibit a more comprehensive structure, characterized by a significantly higher number of subdimensions. This indicates their capacity to provide detailed and granular insights by addressing specific and diverse aspects of digital maturity. Conversely, tools like BIM CAREM, Digital Maturity Self- Assessment and the Maturity Model of Digitisation for SMEs adopt a simpler framework, with fewer main dimensions and subdimensions, suggesting that they are designed for more practical assessments or less complex organisational requirements. The lack of correspondence between the number of main and subdimensions in most tools is noteworthy. For instance, while BIMe and the Digital Acceleration Index have a broader focus, they prioritize detailed exploration within their subdimensions, emphasizing depth over breadth. In contrast, tools like ICMM maintain a more balanced perspective, which is potentially impactful for individuals seeking a more equitable assessment framework. This variation underscores the diversity of assessment strategies, with some tools aiming for extensive coverage across multiple layers of evaluation, while others provide focused insights with limited parameters. This comparison highlights the significance of selecting a tool based on the required depth, breadth and application context.

Table 1.

Evaluation of coverage and gaps in five leading comprehensive digital maturity tools.

Figure 6.

Comparison of selected tools for main dimensions and sub dimensions.

Table 1 presents the five most comprehensive digital maturity assessment tools, highlighting coverage across 11 dimensions, areas of greatest strength, and key gaps. This provides comparative insight into how leading tools operationalize maturity across technological, organisational, and socio-technical domains. The table shows where the construction sector places emphasis and where blind spots persist, particularly in human, governance, and resource-related dimensions. Based on the application of criteria mentioned in Section 3.2.2, the most frequently addressed maturity areas are technology (90%), organisation and management (70%), data and information management (55%) and process and operations (55%). These dimensions are crucial for evaluating an organisation’s digital maturity. Culture and leadership (45%), strategy and vision (45%), standards (45%), and people (40%) received moderate attention, whereas skills training (20%), policy (20%) and financial resources (15%) were rarely considered. The importance of technological readiness contrasts with the limited focus on skills training, policy and financial resource allocation (15%). These findings underline the importance of each dimension in assessing digital maturity in AEC organisations, while also highlighting the industry’s continued prioritization of infrastructural and operational readiness. Full dimensional coverage for all 20 tools, including presence/absence mapping used to calculate these percentages, is provided in Appendix A.2. Furthermore, the linkage of the eleven maturity dimensions with the relevant ISO 19650 clauses and guiding principles is explicitly presented in Appendix A.3.

Beyond the numerical distribution, these frequencies reveal deeper patterns about how digital maturity is conceptualized across the AEC sector. The consistent dominance of ‘Technology’, ‘Organisation and Management’, and ‘Data and Information Management’ reflects the sector’s historical emphases on infrastructure readiness, system integration, governance structures and procedural efficiency areas traditionally reinforced by BIM standards and information management frameworks. Their prominence suggests that most tools continue to prioritize structural and technical capabilities as the primary determinants of maturity. By contrast, the relatively low representation of ‘People’, ‘Skills and Training’, and ‘Policy and Financial Resources’ indicate the persistent under- recognition of human-centred, regulatory and investment-related factors, despite their well-documented influence on digital transformation outcomes. This imbalance highlights a methodological tendency to focus on operational readiness while underestimating socio-technical and resource-based enablers, potentially limiting the ability of tools to capture organisational readiness in a holistic manner. The observed variation therefore underscores both strengths and gaps within current assessment approaches, signalling the need for future tools to better integrate behavioural, cultural and financial dimensions to support a more balanced evaluation of digital maturity. Overall, the most crucial aspect in digital transformation remains technology, followed by organisation and management, data and information handling, and process and operations. These key areas reflect their critical roles in driving digital change, evaluating readiness, emphasizing strong leadership and organisational alignment, recognising data-informed decision-making, optimising workflows, and acknowledging the impact of culture and leadership in fostering innovation. Strategy, vision, standards and people were accorded moderate attention, indicating their significance in shaping overall digital maturity, while the reduced focus on skill development, policy and financial resources points to persistent shortcomings in current assessment methodologies. By considering all these dimensions, AEC organisations can develop more effective strategies for digital transformation, ensuring that every critical aspect is adequately addressed.

A simple co-occurrence review of the dimensions further reinforces these patterns. Tools that include ‘Technology’ almost always include ‘Organisation and Management’, with 80% of technology-focused tools also assessing managerial structures, indicating that digital infrastructure and organisational capability are viewed as jointly influential in determining maturity. Similarly, ‘Data and Information Management’ frequently appears alongside ‘Process and Operations’ (over 70% co-occurrence), suggesting that information workflows are commonly evaluated in relation to broader operational practices. By contrast, low-frequency dimensions such as ‘Policy’ or ‘Finance and Skills’ rarely appear together or in combination with high-frequency domains, demonstrating their peripheral treatment across existing tools. These quantitative patterns highlight a structural imbalance in how maturity is conceptualized, reinforcing the need for future frameworks to more evenly integrate human, regulatory and resource-based dimensions.

5.6. Evaluation Matrix

5.6.1. Assessment Matrix

The assessment matrix of the tools considered in this study varies across different sectors, each focusing on specific dimensions and subdimensions. Several digital maturity assessment tools exist across various sectors, each with unique evaluation areas and dimensions, as described in Section 5.5. The Maturity Scan provides Quick Scan and In-depth Scan options, with the former taking approximately five minutes assessment to complete while the latter thoroughly evaluates an organisation’s digital maturity and takes 15 to 20 min, considering both technical and non-technical aspects of maturity. The Digital Maturity Self-Assessment and Digital Maturity Model provide a comprehensive report covering scores, strengths, weaknesses, and recommendations for improvement. The Digital Maturity Tool [56] encompasses four dimensions and fifteen subdimensions, providing a comprehensive evaluation of digital maturity across multiple aspects of an organisation. The BIM Action-based Maturity Model targets sequential stages to enhance productivity and competitiveness in the Brazilian and Portuguese construction sectors, whereas the BIM Cloud Score assesses BIM performance by analysing user data. The BIM Capability Assessment Reference Model improves facility management in the AEC industry across life cycle phases, while BimSCORE evaluates project BIM maturity by comparing current performance with industry benchmarks and proposing improvements. The VDC BIM Scorecard covers four areas and ten subdivisions, providing a detailed evaluation of virtual design and construction and BIM implementation, comparing project outcomes with industry benchmarks using a weighted sum of measures on a five-level ratio scale. The Organisational BIM Assessment tool focuses on six main elements and twenty sub- elements, to evaluate an organisation’s digital capabilities. The ultimate level of maturity is determined by combining the weighted scores of all component elements, resulting in an aggregate score and a visual representation using a spider web diagram. The Multifunctional BIM Maturity Model assesses three domains and twenty-one subdomains, offering a comprehensive assessment of BIM maturity across multiple functional areas within an organisation.

BIM Excellence (BIMe) uses various methods to evaluate BIM compliance, readiness, capability and maturity, delivering customised scores and reports. BIMe assessments use Likert-scale, multiple-choice, and free-text questions designed for the specific aspects under review. Competency items are rated on a 2-, 5-, or 10-point scale and converted to percentages. The scores cover 56 competency topics and 8 sets according to the scoping phase profile, with 100% indicating complete satisfaction and 0% indicating no satisfaction. The BIM Compass assesses the BIM maturity of organisations through an online questionnaire followed by paid consultation, plotting scores on the Bew–Richards BIM maturity scale. The BIM Maturity Matrix considers five factors evaluated across competencies, capability stages, and organisational scales, offering a multi-dimensional approach to assess digital maturity. The Interactive Capability Maturity Model assesses individual competencies, organisational capabilities, and project performance by providing a quantifiable framework for evaluating BIM implementation, converting subjective views into measurable stages. NBIMS-CMM and I-CMM evaluate project performance in 11 areas using a weighted sum on a 10-level maturity scale through a static, tabular, and multitab interactive Microsoft Excel file. These tools offer varying levels of detail and complexity in their assessments, ranging from quick scans to in-depth evaluations covering multiple dimensions and subdimensions. The choice of tool depends on the specific needs of the organisation, the sector in which it operates and the desired level of granularity in the assessment. While some tools provide free assessments with comprehensive reports, others may require paid consultations or more extensive data inputs for a thorough evaluation of digital maturity.

5.6.2. Measuring Scale and Maturity Levels

Various scaling methods are employed to measure digital maturity and capability assessment. These include the Likert scale for subjective assessments, the ratio scale for quantitative measurements, and the ordinal scale for ranking items. The selected tools employ various scoring and weighting methods. The NBIMS-CMM and I-CMM (10 maturity levels through an ordinal scale) use a weighted sum system to calculate overall maturity scores. BIMe uses 2-, 5-, or 10-point scales to rate competency items on various scales converted to percentages for consistency. The BIM Maturity Matrix (ordinal scale), BIM Compass (Bew–Richard scale) VDC BIM Scorecard (five-level ratio scale) and BIM Cloud Score analyse user data to assess performance, providing a data-driven approach to maturity evaluation. The key features of these maturity scales include the following:

- Consistent progression patterns across different tools, despite variations in terminology

- Association with scoring systems (e.g., percentages or 0–4 or 1–5 ratings)

- Ability to assess various aspects of digital maturity within an organisation

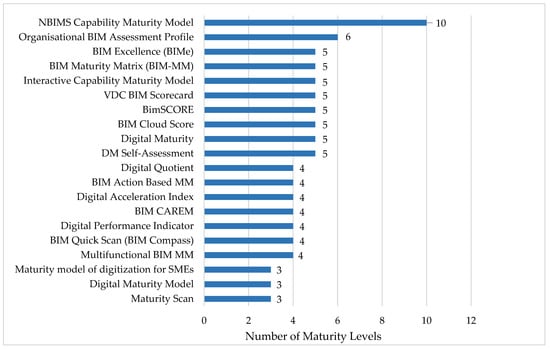

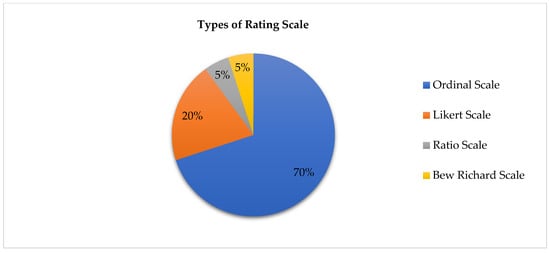

This maturity scale approach provides a comprehensive overview of an organisation’s capabilities while maintaining a manageable number of distinct levels for evaluation. Figure 7 illustrates that the majority of tools assess digital maturity across three to six distinct maturity levels, allowing for a detailed evaluation of an organisation’s progress. The NBIMS CMM is an exception, providing a more granular assessment across ten maturity levels. The distribution of rating scale types employed in the selected tools is shown in Figure 8. The ordinal scale is the most prevalent, accounting for 70% of the total, demonstrating its extensive use in evaluations based on ranking or order. The Likert scale, which is frequently used to assess attitudes or perceptions, represents 20% of the scale. The ratio scale and the Bew–Richard scale are less commonly used, each constituting only 5% of the total, suggesting their limited application within the reviewed tools. The five-level digital maturity level is considered the optimal scale for assessing digital maturity. It offers sufficient detail to capture meaningful differences in maturity levels without becoming overly complex. This scale typically includes initial/ad hoc, planned, defined, managed, and optimised/innovative scales. This progression allows organisations to benchmark their current state and provide a roadmap for improvement. By using such a scale, organisations can effectively evaluate their current digital maturity status and identify areas for improvement to reach higher maturity levels. This structured approach enables organisations to develop targeted strategies to enhance their digital capabilities and overall performance.

Figure 7.

Number of maturity levels in selected digital maturity assessment tools.

Figure 8.

Types of rating scales included in selected digital maturity assessment tools.

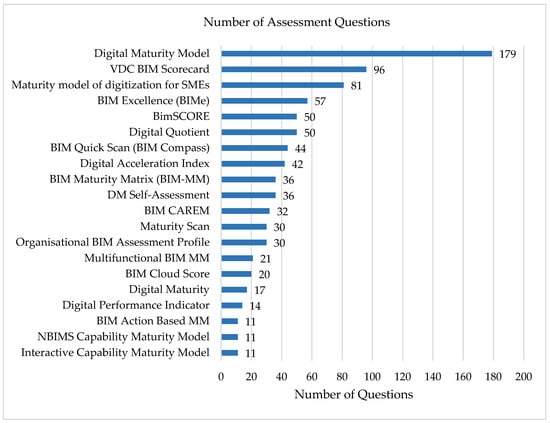

5.6.3. Number and Types of Assessment Questions

The number of questions in these assessment tools varies significantly, with the minimum number of questions being 11 and the maximum being 179, as shown in Figure 9. This range allows for different levels of detail and depth in the assessment process, serving various organisational needs and time constraints. The graphical representation compares the number of assessment questions across various digital maturity assessment tools, highlighting significant variations in their depth and comprehensiveness. The Digital Maturity Model has the highest number of questions, indicating its detailed and extensive approach for evaluating digital maturity. This level of detail may make it suitable for organisations requiring thorough analysis but is potentially less practical for organisations seeking quick assessment. The VDC BIM Scorecard and the Maturity Model of Digitisation for SMEs also include a substantial number of questions, showcasing their focus on offering a well-rounded evaluation framework tailored to specific needs. In contrast, tools such as the Interactive Capability Maturity Model and the NBIMS Capability Maturity Model feature far fewer questions, reflecting a more concise and focused methodology. These tools may appeal to users with time constraints or those looking for a preliminary evaluation rather than an in-depth analysis. Other tools, such as BIM Excellence and BimSCORE, occupy the middle ground, providing a balance between comprehensive insights and assessment efficiency.

Figure 9.

Number of assessment questions in selected digital maturity assessment tools.

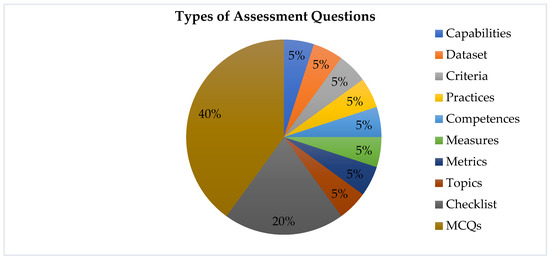

The disparities in question count suggest that these tools are designed with varying complexity and target sectors. Some prioritize exhaustive frameworks for detailed assessments, while others aim for simplicity, emphasising alignment with organisational goals and resources. This variation underscores each tool’s individual assessment scope. The distribution of question types across tools is illustrated in Figure 10, showing notable differences in usage. Multiple-choice questions (MCQs) comprise 40% of the total, reflecting their broad application in structured evaluations and result interpretation. Checklists followed at 20%, demonstrating their value in task verification and compliance checks. The remaining categories, including capabilities, datasets, criteria, practices, competences, measures, and metrics, each represent 5% of the total, indicating their specialized functions in offering varied evaluation approaches within these tools. This distribution highlights the incorporation of question types designed for diverse assessment requirements.

Figure 10.

Types of assessment questions included in selected tools.

The key characteristics of the evaluation approaches adopted in the selected tools are presented in Table 2, including the types of assessment questions, measurement scales, and points on the scale. This analysis provides an insight into the methodologies and evaluation levels for assessing the organisational digital maturity of various sectors. Most of the selected tools employ a five-point ordinal scale or Likert scale, while BIM Compass and VDC BIM Scorecard are notable exceptions, using the Bew–Richard and ratio scales, respectively.

Table 2.

Evaluation matrix of selected digital maturity assessment tools.

5.7. Comparative Analysis of Digital Maturity Assessment Tools

A comparative analysis of digital maturity assessment tools in the AEC sector reveals a diverse landscape of approaches, key features, and focus areas. These tools vary in their frameworks, scopes of assessment, evaluation metrics, strengths, and limitations. Framework diversity is evident, with tools ranging from Microsoft Excel-based options such as OBAP, ICMM and NBIMS-CMM to software as a system (SaaS)-based platforms such as BIMCS and online assessments, which include Maturity Scan, DAI, DPI and BIMe etc. The assessment scope differs among tools, with some focusing on internal capability (ICMM), while others enable cross-organisational comparisons (NBIMS-CMM, BIMCS) or assess multiple levels including individual, team and organisations (BIM MM, BIMe). Evaluation metrics also vary, with tools employing capability maturity scales (NBIMS-CMM), compliance quantification (VDC BIM Scorecard), and dimensional assessments (Organisational BIM assessment profile). Each tool has unique strengths, such as real-time collaboration capabilities (BIMCS), comprehensive coverage (VDC BIM Scorecard) and alignment with industry standards. However, limitations also exist, including subjectivity issues (NBIMS-CMM), reliance on self-reporting (BIMe), and lack of practical use documentation (Organisational BIM Assessment Profile). Despite the differences, prioritized dimensions across the tools include technology, organisational management, data, information management and process and operations. Notably, some areas appear to have lower priority across the tools, including people, leadership, culture, policy, strategy, vision, skills training, standards, and financial resources. These findings suggest that current tools may overlook critical human and strategic elements in favour of more technical aspects. This imbalance could potentially lead to incomplete or skewed evaluations of an organisation’s true digital readiness. Future iterations of these tools may benefit from incorporating a more holistic approach that gives appropriate weight to both technological and human-centric factors when assessing digital maturity. This comparison highlights the complexity and diversity of digital maturity assessment in the AEC sector while also identifying areas for potential improvement and standardisation in future tool development.

The diversity of assessment tools reflects the complicated nature of digital maturity in the AEC sector, underscoring the necessity for comprehensive evaluation approaches. Future tool development could benefit from addressing the highlighted areas for less prioritized areas to provide a more holistic assessment of digital maturity. Standardisation efforts in digital maturity assessment could potentially yield more consistent and comparable results across industries, thereby facilitating benchmarking and targeted improvement strategies.

Based on this analysis, the development of a novel tool for the AEC sector could facilitate further digital transformation. The new tool, which can take various forms, such as Microsoft Excel spreadsheets, web-based applications, research platforms, or static tabular formats as observed in the reviewed tools, can be selected for immediate, free access to support AEC organisations in conducting digital maturity assessments to facilitate their digital transformation journey. Such a tool should incorporate the following key features.

- A five-level maturity scale (ranging from initial/ad-hoc, planned, defined and managed to optimised) associated with a five-point Likert rating scale.

- Integrating key components such as maturity assessment levels, dimensions, sub dimensions, and a path to maturity.

- The tool should align with ISO 19650 maturity stages and clearly identify gaps in evaluating the organisation’s digital maturity.

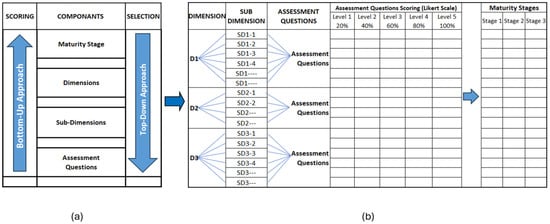

The choice between top-down or bottom-up approaches in developing a maturity assessment tool is a common dilemma for developers [61]. The top-down approach defines maturity stages first and then selects dimensions and subdimensions, whereas the bottom-up approach begins with requirements and measures and then defines stages. De Bruin et al., [43] provides a clear answer to this question, where a top-down approach is considered ideal for emerging dimensions without maturity evidence, whereas a bottom-up approach fits established dimensions focused on maturity assessment. Conversely, Solli and Gottschalk [62] recommended a step-by-step method for developing a maturity tool, irrespective of the maturity of the dimension. Consequently, there are no definitive guidelines for the selection of a suitable methodology. It is essential to rely on established research and to empirically validate the dimensions and constructs of the tool. Through the careful selection and implementation of an appropriate assessment tool, organisations in the AEC sector can effectively evaluate their digital maturity and establish a trajectory for successful digital transformation.

5.8. Gaps in Current Tools and Future Recommendations

This study highlights emerging trends and opportunities in digital maturity assessment tools, with a focus on identifying gaps in the selected tools, thereby highlighting the need for a potential new tool to provide a comprehensive assessment approach for evaluating digital maturity in the AEC sector. The recommended framework for such a tool is as follows:

5.8.1. Gaps in Dimensions Assessment

A thorough evaluation of the 20 reviewed digital maturity assessment tools (Section 4 and Section 5) reveals that there is a lack of a holistic assessment approach in the selected tools to address the 11 key maturity areas cited in the literature [14,15,16,63,64,65,66]. Furthermore, these tools do not simultaneously assess the critical dimensions of processes, people, culture, technology, skills training, financial resources, and policy and governance, which are essential for comprehensive assessment. To bridge this gap, the development of a new and comprehensive digital maturity assessment tool would facilitate parallel evaluation of the identified areas in terms of associated dimensions.

Lack of Integrated Assessment Approach in Process, People and Culture

The reviewed tools assess critical maturity dimensions such as processes, people and culture, either individually or partially. However, consistently evaluating dimensions, including business processes, organisational structure, employee skills and cultural attitudes towards technology, is crucial for assessing an organisation’s digital maturity and successful digital transformation. An integrated assessment approach of culture, leadership, people, processes, and operations would offer a comprehensive evaluation of how these dimensions interact and influence each other.

Lack of Technology Integration

In acknowledging the key role of technology in digital maturity assessment presented in Table 1, a new tool should evaluate the organisation’s technology infrastructure, including software for model optimisation, collaboration, data sharing, asset information integration, site planning, scheduling, cost estimation, facility management, clash detection, visualisation and access to fully licensed software. This comprehensive assessment would address the technological foundation essential for effective digital transformation in the AEC sector from the perspectives of clients, consultants, contractors, and asset management teams.

Lack of Policy and Governance Alignment

The third dimension focuses on integrating policy and governance into digital maturity assessment. This includes evaluating the adherence to industry standards and protocols, BIM policy, strategy and vision, legal and contractual aspects, data management, integration with existing processes and cybersecurity protocols. Evaluating organisational alignment with these policies provides valuable insights into their commitment to compliance, quality assurance and ethical considerations.

Collective Assessment Approach

Most maturity assessment tools evaluate strategy, vision, process, and technology individually, often neglecting people, culture, policy, skill training, and financial resources. However, the interrelated nature of these areas in terms of assessing process, people, and culture alongside technology and policy and governance would provide a holistic assessment approach and a more clear and comprehensive understanding of an organisation’s digital maturity.

Based on the identified limitations in current toolkits and gaps in maturity domain coverage, this study proposes a tailored digital maturity evaluation framework. This is presented in detail in the following section.

6. Proposed Digital Maturity Evaluation Framework

This section presents a thorough digital maturity evaluation framework developed to address the critical gaps identified across existing assessment tools. As discussed in earlier sections, many tools within the construction industry disproportionately emphasize technological readiness while neglecting equally important dimensions such as policy, leadership, skills development, and financial capacity. The proposed framework is designed to offer a balanced, multi-dimensional, and construction-specific structure that aligns with contemporary industry needs, ISO 19650 principles, and digital transformation goals.

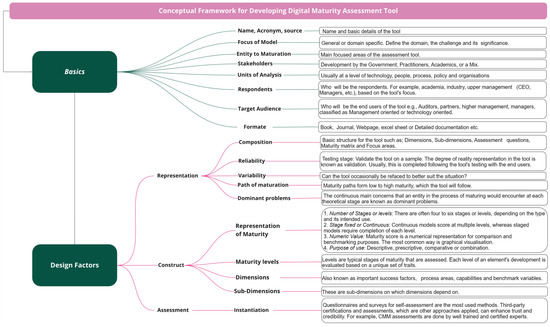

6.1. Framework Structure and Components

The conceptual foundation of the proposed framework is illustrated in Figure 11, which outlines key design considerations such as target audience, stakeholder involvement, unit of analysis, and representation challenges [67]. These factors were synthesized from literature and tool analysis to ensure the framework fits diverse organisational contexts in the AEC sector. It integrates theoretical underpinnings and practical realities, serving as a blueprint for developing a digital maturity assessment tool.

Figure 11.

Guideline for the proposed conceptual framework for a digital maturity assessment tool.

Figure 11 has two main clusters: “Basics” and “Design Factors”. This structure separates contextual prerequisites from assessment mechanics. “Basics” covers conditions determining tool fitness for each organisation, including audience, stakeholders, unit of analysis, assessment targets and reporting form. These elements govern applicability and intended use. “Design Factors” covers the tool’s construction—dimensions, maturity levels, scoring, representation, variability handling, reliability and instantiation—as these elements govern methodological rigor and auditability. This split addresses gaps identified in the review, where tools report scores but under-document their context of use or measurement logic. This aligns with recognised guidance on maturity model development, where scoping and stakeholder design choices precede tool development, testing and representation [43,67]. By making the context layer explicit (“Basics”) and formalizing the measurement layer (“Design Factors”), Figure 11 provides a blueprint that is usable across diverse AEC settings and transparent enough to be replicated, audited and improved. It fills critical gaps in tool design strategy and provides a replicable guide for new maturity evaluation tools in the AEC industry.

The framework comprises five integrated components guiding the maturity evaluation process. The first component is the maturity level structure, using a five-point Likert scale common in digital maturity models. The framework categorises development into five levels: initial, defined, integrated, managed, and optimised, enabling benchmarking and gap analysis. The second component involves eleven maturity dimensions, identified through cross-tool comparative analysis. These include technology, process and operations, organisation and management, people, data and information management, policy, standards, culture and leadership, strategy and vision, skills and training, and financial resources. Each dimension is decomposed into subdimensions to provide granular insight into organisational capabilities. The third component is composed of assessment questions aligned with each subdimension, serving as the basis for evaluating organisational performance. The fourth component is maturity path mapping, which charts current state against desired future state across dimensions. This gap analysis supports prioritisation of interventions and planning. The fifth component is a visual scoring model for the intuitive interpretation of results, presented in matrix or radar chart format. The complete scoring structure and evaluation model is shown in Figure 12b.

Figure 12.

Top-down and bottom-Up approach and proposed framework: (a) Top-down and bottom-up approaches for component selection and scoring criteria, (b) proposed framework for the digital maturity assessment tool.

For illustration, the “Process, People and Culture” dimension is operationalized through six subdimensions: BIM training and education, BIM awareness, BIM competency, BIM change management and adaptability, BIM leadership and support, and collaborative culture. Each subdimension is measured through 3–6 behaviour-anchored questions scored on a five-point Likert scale that is aligned with the five maturity levels in Figure 11. For example, for “BIM Training and Education”, Level 1 represents no structured training and only ad hoc awareness, Level 3 reflects regular role-specific training embedded within organisational procedures, and Level 5 denotes a continuous learning culture with advanced, accredited programs and systematic knowledge-sharing across projects. Respondents select the statement that best reflects their current practice and item scores are averaged to obtain a subdimension score and mapped to the nearest maturity level (1–5). Subdimension scores are then aggregated (equal weighting) to produce an overall maturity score for “Process, People and Culture”, which is displayed alongside technology and policy and governance in the dashboard. This example demonstrates how the proposed framework translates abstract dimensions into concrete questions, level descriptors, and scores that can be used to benchmark organisations and identify targeted improvement actions, particularly for people- and culture-related aspects of digital maturity.

6.2. Framework Development Approach