Abstract

A comfortable and livable living environment can be created through the design of patios in traditional southern rural Chinese dwellings. By connecting indoor and outdoor spaces, patios enable the comprehensive functions of ventilation and shading. To investigate the effects of patios on the building environment and energy conservation, the field parameters of the Wu Family Mansion in Cuijiao Village, Fujian Province, southern China, were measured in August 2016. The results indicate that patios located at the center of dwellings can effectively mitigate the impact of outdoor climate on the indoor environment. Furthermore, a reasonable depth-to-width ratio of the patio is conducive to natural ventilation and energy utilization. Through discussions and simulations using CFD and EcoTECT, it is determined that the reasonable depth-to-width ratio should not be less than 0.06, and a depth of 1.6 m is the most appropriate for patio design to achieve adequate ventilation and illumination. With the Adaptive Predicted Mean Vote (APMV) value ranging from 0 to 1.41, the indoor environment of this rural building falls within the adaptive comfort zone. Compared with air-conditioned rooms, the energy-saving rate achieved by natural ventilation is approximately 26.2%.

1. Introduction

1.1. Current Research Status at Home and Abroad

The patio holds a significant position in traditional Chinese architectural design and serves as a typical carrier of the organic integration of traditional culture and architectural design. Rational application of patios in courtyard architectural design is a key path to achieving the harmonious coexistence of humans, buildings, and nature. In “The Essence of Tradition” [1], Professor Miao takes the overall perception of the traditional architectural environment as the original research topic, emphasizing that the essence of architecture is a “spatial system providing perceptual experiences for humans” rather than an isolated set of structures. Therefore, the design method of guiding the utilization of natural energy such as solar and wind energy through patio design has become a crucial design tool for creating a comfortable and livable environment in traditional buildings [2].

Existing literature confirms that patio designs should adopt differentiated approaches based on local climatic conditions to achieve different functional effects [3,4]. Firstly, in hot and arid regions, Al-Hemiddi [5] analyzed the impact of inner courtyard designs on the thermal performance of residential buildings in hot and arid areas, and results show that courtyards are highly effective in providing cool indoor air through cross-ventilation. Soflaei [6] focused on the impact of courtyard design variations on shading performance in traditional courtyard residences in the hot and arid climate zones of Iran, taking geometric characteristics and orientation as key factors and proposing optimal courtyard design schemes. In the hot and arid climate zone of northern Iraq, polygonal courtyards (pentagonal, hexagonal) have larger shading areas and better shading performance than rectangular courtyards, with the core goal of reducing indoor temperature by minimizing solar radiation [7]. Akbari et al. [8] selected 30 historical residential courtyards in Isfahan, Iran, located in a hot and arid climate as their research objects. They analyzed the geometric characteristics (e.g., aspect ratio and height-length ratio) and natural element characteristics (e.g., water surface and vegetation ratios) of these courtyards, derived relevant linear equations and correlation coefficients, providing a reference for courtyard design in hot regions. For temperate regions, Martinelli et al. [9] proposed that Italian courtyards should adopt a “stabilized aspect ratio” design with an aspect ratio of 1.2 to 1.5 to balance winter heat gain and summer ventilation; El Bat et al. [10] further verified that in temperate climates, medium-depth courtyards with a depth of less than four meters can optimize the balance of building heating and cooling energy consumption. Wang Guohua et al. [11] took the traditional residential courtyards in Xiaoyi Ancient City, Shanxi Province, China, as the research object. They systematically explored the climate adaptability characteristics of traditional cold-region courtyards in terms of spatial layout, architectural form, and material application, focused on analyzing their core logic for coping with severe winter cold while balancing thermal insulation and ventilation, and proposed targeted optimization strategies to further enhance the climate adaptability and modern livability of such courtyards. Warm and hot regions have significant climatic differences from cold and hot regions, thus possessing research value.

One of the main functions of patio design is to achieve passive cooling through natural ventilation and shading. Firstly, numerous scholars have conducted research on the wind velocity field of courtyards with patios. Sun Qianqian et al. [12] studied the natural ventilation modes of patio spaces in residential buildings along the Maritime Silk Road in the South China Sea, proving that patios can cool buildings, dehumidify, and enhance natural ventilation. Sun, Qianqian et al. [13] focused on humid and hot regions in China, exploring the impact of spatial attributes of enclosed patios, such as aspect ratio, orientation, and window/door opening forms on temperature, wind velocity, thermal comfort, etc., aiming to provide a basis for the thermal performance optimization design of enclosed patios in this region. Wieser and Martin [14] took the cross-ventilation between the courtyards of the traditional Riva-Aguero house in Lima as the research object and analyzed the impact of courtyard layout and climatic conditions on ventilation through field observations and data collection. The results showed that using the special relative positions layout between two courtyards can activate cross-ventilation between them, helping to maintain indoor temperatures within a reasonable range. Zheng, Wenheng et al. [15] took the traditional Hakka Tulou, China (a world heritage site) as the research object, analyzed their microclimatic characteristics through investigations, and concluded that the patio structure has the climate adaptability advantages of being warm in winter and cool in summer, dehumidifying, and moisture-proofing. Additionally, patios can improve courtyard lighting, but the lighting of inner rooms is weaker than that of outer rooms. Rajapaksha and Nagai [16] conducted a survey on passive cooling courtyards in single-story large-volume buildings in hot and humid climates, pointing out that internal patios in architectural design help optimize natural ventilation, thereby minimizing indoor overheating. Meng [17] used Fluent software to simulate the wind velocities of different layout forms, and analyzed the advantages and disadvantages of existing courtyard wind environments combined with wind velocity ratio evaluation standards. Researchers studied the ventilation performance of scaled four-sided wind towers connected to living rooms and courtyards under different wind incidence angles by combining numerical simulations and experiments. Jiang, Jinlin et al. [18] took the architectural culture of Shanggantang Village in southern Hunan as a case, conducted field measurements and numerical simulation analysis of the light environment of local traditional residential buildings with patios, explored the key factors affecting indoor lighting by patios, and proposed optimization strategies. Gao, Rui et al. [19] extracted key design parameters affecting lighting, such as windowsill height, window width, and patio length and width, through field investigations and literature analysis. They carried out multi-factor orthogonal experiments and single-factor quantitative comparative analysis with the help of Honey Bee software 1.5 in Grasshopper, and clarified the degree of influence of each parameter on indoor lighting. The research results showed that reducing the height of the window edge can improve the lighting effect near the window, while increasing the window width and patio width can enhance the overall lighting quality of the room. Muhaisen [20] also examined the shading performance of polygonal patio structures with pentagonal, hexagonal, heptagonal, and octagonal planes. Acosta [21] proposed a fast and accurate method based on the variable geometric shapes and reflectivity of internal surfaces to determine the daylight factor at different points in the central space of rectangular patios or atriums.

Another important function of patios is to improve indoor occupant comfort, reduce building energy consumption, and extend the building life cycle. Fuertes, Pere et al. [22], based on a survey of 565 buildings in Barcelona, proposed that patios can be regarded as a “structural invariant”: they possess core characteristics such as spatial organization, circulation arrangement, and enhancing indoor livability, can be continuously retained during function changes and adaptive reuse, and are crucial for reducing the impact of renovations on the original building structure and extending the building’s life cycle. Wang, Jie et al. [23] used Design Builder (v7.0.2.006) simulation software to analyze the impact of 10 selected courtyard renovation measures on thermal comfort and energy consumption, and adopted the entropy weight method to comprehensively evaluate the indicators of improving thermal comfort and reducing energy consumption. The results proved that courtyards are effective in improving indoor thermal comfort and reducing building energy consumption, and different forms of buildings require different optimal schemes. Li, Meiling et al. [24] focused on roof-covered enclosed courtyards in China’s cold region IIA, and studied the dynamic performance of this type of courtyard as well as the microclimate regulation and energy consumption performance of the Controllable Solar Air Ventilation Roof (CsAVR) through on-site measurements, model construction and verification, and comparative experiments. The results showed that the CsAVR can reduce temperature, extend comfortable periods, and save energy. Overall, buildings with open patios exhibit better energy consumption performance in low-rise buildings [25,26]. A study analyzed the impact of transition spaces on the energy consumption performance and indoor thermal comfort of low-rise residential buildings in the Netherlands, finding that converting courtyards into atriums reduces heating demand but increases the number of uncomfortable hours [27].

Therefore, the aforementioned literature has explored the impacts of a single courtyard or patio on the wind environment, light environment, thermal comfort, and energy consumption of residential spaces, respectively, proving that patio design is an excellent approach to adapting to the natural environment and achieving sustainable building development. However, few studies have explored the comprehensive effect of multiple patio designs on the microenvironment of architectural spaces. This paper takes traditional multi-patio buildings as the research object, analyzes the indoor and outdoor thermal environment conditions of multi-patio buildings, discusses the reasonable depth-to-width ratio of patios, and determines the adaptive comfort level and energy-saving potential of multi-patio designs.

1.2. Study Object

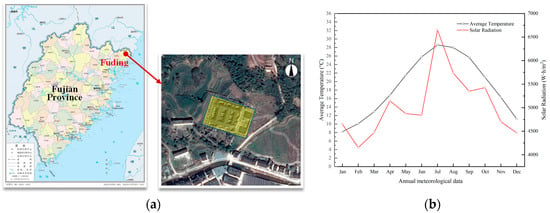

The Wu Family Mansion was built in 1815 during the Qianlong period and is located in Cuijiao village, Bailin town, Fuding city, Fujian province. It is one of the best-preserved quadrangle dwellings in China at present. The geographical location, climate zone conditions and annual meteorological parameters outside this house are shown in Figure 1. Fuding is located on the southeast coast and has a subtropical maritime monsoon climate. The climate is mild, with moderate rainfall. There is no severe cold in winter and no intense heat in summer. Rainfall and heat occur concurrently in spring and summer. Autumn and winter are characterized by sufficient sunlight, abundant heat, abundant rainfall, and a distinct maritime monsoon climate. The annual average temperature is 19.2 degrees Celsius, the annual average rainfall is 1720.0 mm, and the annual sunshine duration is 1634.9 h.

Figure 1.

Building Basic Information. (a) Climate region and house location. (b) Annual meteorological parameters.

It can be seen that the Wu Family Mansion is located in the hot summer and warm winter region of China, with an orientation of 30 degrees east of south. Behind this mansion, there are green woodlands and hills. The height difference between the front and back side is about 24.6 m. The left side of the mansion is surrounded by mountains, while the right side is adjacent to streams and roads, with a height difference of about 24.4 m between the left and right sides. This design took into account the natural environment and topography surrounding the mansion, reflecting the harmonious information of local geographical features.

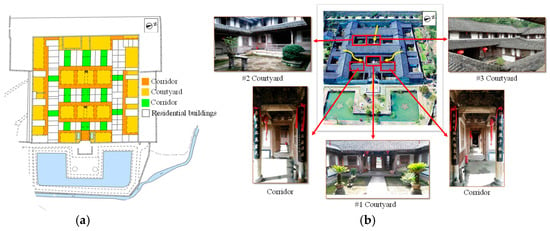

As shown in Figure 2, the Wu Family Mansion is square, regular, and of an antique style. Patios are designed with distinct landscapes, and houses are assigned different functions. Several patios are enclosed by two-story and single-story houses. The Wu Family Mansion is composed of patios, courtyards, and dwellings. There are three parallel rows of patios, which integrate the courtyards into the building environment. These patios facilitate people’s interaction with nature through gentle air flow. Indoor and outdoor spaces are interdependent, complementary, and interconnected. Architectural space and natural space are alternate, cleverly interspersed, and integrated. The patios can capture sunlight, rain, and natural ventilation.

Figure 2.

Architectural design of Wu family messuage (a) Spatial layout; (b) Composition.

2. Methods and Materials

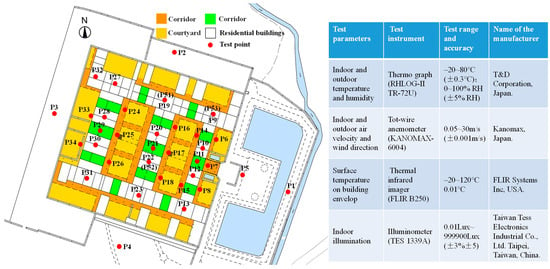

2.1. Equipment and Test Points

To analyze the variations of micro environmental parameters inside and outside the Wu Family Mansion, it was necessary to measure air temperature, relative humidity, and air velocity using different testing instruments. In addition, the arrangement of test points is shown in Figure 3. The tests were conducted from 9 August to 11 August 2016, with a recording interval of 10 min. The data used for the simulation covers the period from 9 August to 11 August. It includes the measured CO2 concentration, wind flow paths, wind speeds, temperatures, and humidity at each measurement point, as well as outdoor meteorological parameters and illuminance.

Figure 3.

Test points and instruments.

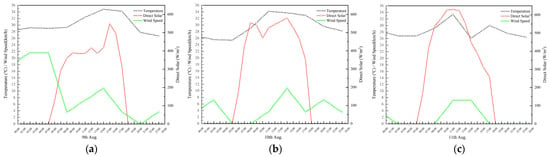

2.2. Outside Meteorological Parameters

The meteorological parameters outside this house from 9 to 11 August are shown in Figure 4. The outside air temperature varied between 25 °C and 34 °C. The max value of direct solar radiation was 650 W/m2. The wind speed was between 0 and 22 km/h (6.1 m/s).

Figure 4.

Outside meteorological parameters (a) Data on 9 August. (b) Data on 10 August. (c) Data on 11 August.

2.3. Errors for Measured Values

In the above measurements, the measurement errors of the testing instruments and the calculation errors were comprehensively analyzed based on Reference [28]. The synthesis method was used to address the systematic error, and the t-distribution method with a 95% confidence level was used to address the random error.

The systematic error is formulated as:

where, Ba,sys is the systematic error, LC is the instrumental error, and FS is the range of the measuring instruments.

Random error is given by:

where Ba,ran is random error, σ’ is sampling variance, N is the sample size, t is the critical value of the t-distribution method, which can be determined by the sample size and measurement confidence level, Yj is an individual measured value, and Yave is the average measured value.

Based on Formulas (1) and (2), the total measurement error of direct measurements (Ba) could be determined as follows:

However, based on the principle of uncertainty propagation calculation, the total measurement error of indirect measurements (BF) can be confirmed as follows:

where Ba is the total measurement error of direct measurements, BF is the total measurement error of indirect measurements, F represents the functional relationship, and a1, a2, …, aN represent the direct measurement parameters.

Based on the above calculation methods, the errors of the measured values are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Error analysis for measured values.

3. Results and Discussions

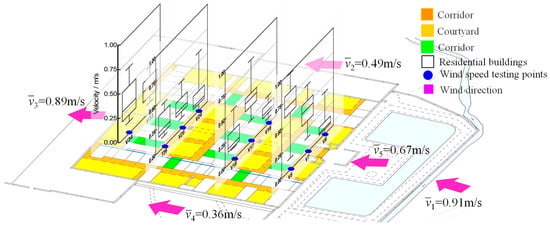

3.1. Ventilation Effect

The indoor and outdoor microclimate of this mansion can be regulated by natural ventilation. As shown in Figure 5, the southeast wind is the dominant wind direction. When the air velocity at the gate reaches a maximum of 1 m/s, the air velocity inside the mansion ranges from 0.25 m/s to 0.75 m/s, which falls within the comfortable living range. Based on the variations in air velocity, the air velocity on the east side of the mansion is more stable than that on the west side. This shows that patio design can effectively reduce the interference of outdoor air velocity on indoor air velocity.

Figure 5.

The variation of air velocity of the horizontal plane.

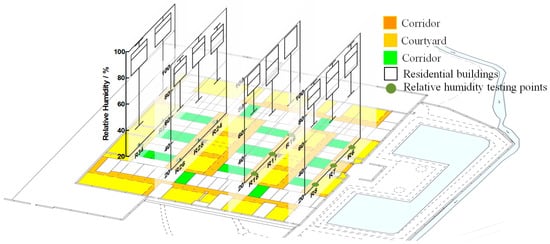

3.2. Thermal Environment

Due to the height difference of approximately 1.6 m between the back side and the front side of the Wu Family Mansion, rainwater can flow into the pool in front of the mansion through outfalls and drains. As shown in Figure 6, because of the transpiration effect of the drainage water system, the relative humidity on the front side of this mansion is 20% higher than that on the back side.

Figure 6.

Relative humidity variation.

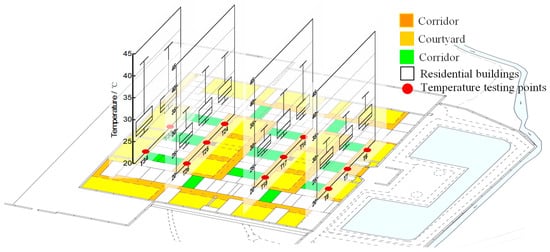

As shown in Figure 7, the average temperature is about 26.7 °C. The average air temperature of the corridor in the first row is 1 °C lower than that in the third row, because the cooling effect can be achieved by natural ventilation flowing from the water pool to the front of this courtyard house.

Figure 7.

Temperature variation.

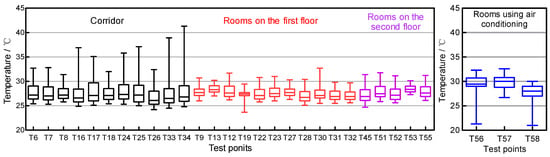

The corridor functions as a buffer space, connecting indoor and outdoor environments. As shown in the air temperature comparisons in Figure 8, the temperature difference between outdoor and indoor air is about 5.4 °C, due to the shading effect of the building and the transpiration effect of the water system in the patios. Meanwhile, the thermal properties of the building materials used in the quadrangle houses (such as blue bricks, grey tiles, rammed earth, wood, etc.) are highly compatible with the seasonal climate, effectively preventing excessive indoor heat in summer. The indoor air temperature of a modern house using an air conditioner is as low as 21 °C. However, the average indoor air temperature in a room without air conditioning is nearly 30 °C, which is 3.7 °C higher than that in natural ventilated rooms of traditional houses. This illustrates that natural ventilation contributes to building energy conservation.

Figure 8.

Temperature variation in rooms and corridors.

3.3. Shading and Lighting

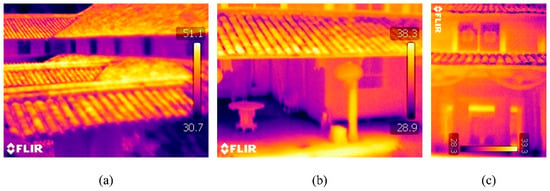

As shown in the comparison in Figure 9, the surface temperature on the roof is about 51.1 °C, which is 13 °C higher than the surface temperature in the room, due to the shading effect of the building. Furthermore, the temperature in the ground room is about 28.9 °C. This indicates that a raised floor design on the first floor can effectively prevent cold energy from being transferred into the room.

Figure 9.

Infrared thermographic images; (a) Second floor; (b) First floor; (c) Both floors.

3.4. Adaptive Comfort and Energy Saving Ratio

The results of the adaptive comfort zone are calculated based on the above environmental parameters measured inside and outside the house. According to the “Standard for Evaluation of Indoor Thermal and Humid Environmental Conditions in Civil Buildings (GB/T 50785-2012)” [29], the APMV is calculated as follows:

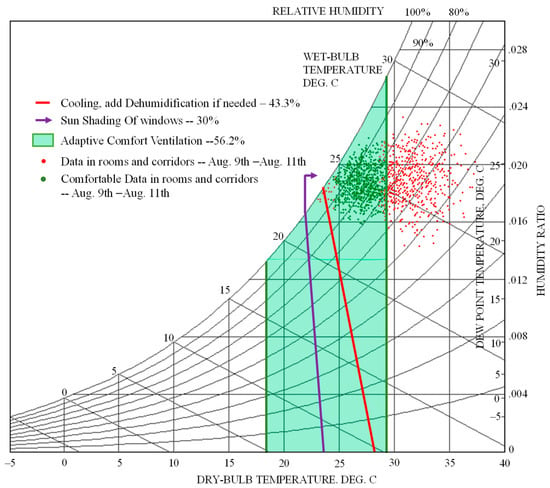

where APMV is expected Adaptive Predicted Mean Vote, λ is the adaptive coefficient of residential buildings in hot summer and warm winter areas (when PMV ≥ 0 in summer, λ takes 0.21), and PMV is the estimated average thermal sensation index, as in [30]. Through calculation, APMV ranges from 0 to 1.41 and PPD ranges from 0.40 to 0.50. This illustrates that 50~60% of people can accept this residential environment, and feel comfortable.

A rational patio design can effectively reduce the direct influence of outdoor climate on the microclimate and indoor environment. As shown in Figure 10, achieving adaptive comfort through natural ventilation instead of air conditioning not only saves energy but also reduces heat emission to the outside. Compared with using a 3.85 kW air-conditioner, the energy-saving ratios of sun shading and ventilation are approximately 20% and 26.2% respectively.

Figure 10.

Adaptive comfort analysis.

3.5. Ratio of Depth to Width of a Patio

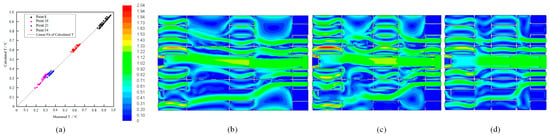

According to the physical model described above, the simulation model is selected from reference [31], which can calculate air velocity fields under conditions of different patio depths. The materials and physical parameters of this house are given above. The building envelope of the house is wood with a thickness of 0.2 m, density is 750 kg/m3, and coefficient of thermal conductivity is 0.4 W/(m·K). Furthermore, the subdomain method of structured triangle mesh is used for meshing the geometric space. The grid size is set to 0.01 m for a suitable computational grid; thus, the meshing number is set to 249,600 for calculation. The boundary condition takes into consideration the heat transfer between air and building envelopes. The initial conditions include: Tain = 308 K; Taou = 303 K; Tbe = 305 K; and vav,air = 0.1 m/s. The air velocities were calculated by the classic SIMPLE uncoupled solution method. The original text intends to convey that the SIMPLE method in CFD (Computational Fluid Dynamics) is used to solve problems under the non-coupled condition, which is the classic SIMPLE solution method. By comparing the simulated results with the measured results, the average relative error of the mathematical model is 8.9%, which is lower than 10%. This model can be used for wind field analysis. The software version employed in this study is ANSYS 17.0, and all boundary conditions for the simulation are based on field measurement data. As shown in Figure 11, when the depth-to-width ratio decreases from 0.30 to 0.06, the average air velocity of the building plane is reduced from 0.70 m/s to 0.5 m/s, with the wind direction being 30 degrees east of south. This illustrates that patio design with reasonable depth is conducive to cooling. For the Wu Family Mansion, the depth-to-width ratio of the patio should be no less than 0.06.

Figure 11.

Air velocity field under different ratios of depth to width of the patio (a) Measured and calculated results; (b) Ratio is 0.30; (c) Ratio is 0.15; (d) Ratio is 0.06.

Figure 11a presents a comparison between the simulated and measured temperatures. The simulated values at measurement points 8, 16, 25, and 34 are approximately distributed along the 1:1 line relative to the measured values. This indicates that the temperature calculation results of the CFD model exhibit minimal deviation from the actual measured data, confirming the model’s reliability for engineering analysis. Figure 11b–d illustrate the temperature contour maps of the courtyard area. The central region of the courtyard is predominantly yellowish-green, corresponding to a temperature range of 12–15 °C, whereas the edge regions enclosed by buildings are mainly blue, with temperatures ranging from 0–10 °C. This forms a gradient distribution characterized by a “warm central zone and cool peripheral zones”. Notably, no local hot spots are observed in the temperature field, which implies that airflow has achieved uniform heat diffusion within the courtyard space. This thermal performance is consistent with the spatial functional orientation of “moderate airflow and natural thermal exchange”. The alternating layout of three parallel rows of parallel courtyards and buildings creates natural airflow channels, which effectively eliminates ventilation dead zones and ensures a uniform thermal environment throughout the space.

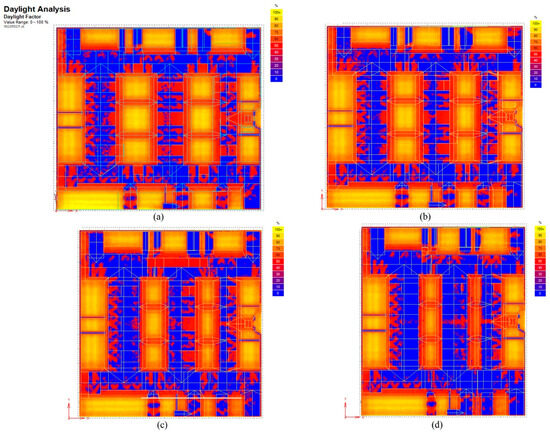

When the ratio of depth to width of the Wu Family Mansion is reduced to 0.30, 0.15, and 0.06, respectively, the daylight factors were simulated by EcoTECT and the results are shown in Figure 12. When the structure remains unchanged, the relative error of the daylight factors is less than 10%. Figure 12b shows that the daylight area on the first floor is reduced by 8% when the ratio of depth to width of the patio is reduced to 0.30. Figure 12c shows that the daylight areas on the first floor are reduced by 15% as the ratio was reduced to 0.15. Figure 12d shows that the daylight areas on the first floor are reduced by 30%, as the ratio was reduced to 0.06. However, the daylight factors of the rooms in the middle row are nearly zero. This illustrates that patio depth directly affects daylight in rooms. The ratio of depth to width of the patio should be no less than 0.06.

Figure 12.

Daylight factors at the height of 0.8 m on the first floor under different ratio of depth to width of the patio; (a) No change; (b) Ratio is 0.30; (c) Ratio is 0.15; (d) Ratio is 0.06.

Areas with high light intensity are mainly concentrated in the open spaces of the courtyard and the unenclosed sections of the building envelope, including the courtyard center, building entrances, and patios. These areas are unobstructed by surrounding structures and thus receive direct natural light. Medium-light areas are distributed at the transitional interfaces between the courtyard and buildings, such as building eaves and courtyard edges; these zones are partially blocked by structures but still capture scattered natural light. This spatial arrangement creates a gradient transition of light intensity across the courtyard–building system. Low-light areas are concentrated in enclosed spaces such as the building’s internal corridors and shaded courtyard corners, where light penetration is impeded by multiple layers of architectural obstruction. Consequently, these areas experience significant structural shading and weak natural light transmittance.

As an open spatial element, the courtyard functions as a natural light introduction node, indirectly channeling light into medium-light areas and reducing the building’s reliance on artificial lighting. The partial shading provided by the building envelope not only mitigates glare caused by excessive direct sunlight but also maintains baseline daylight availability through the permeability of the courtyard–building interface. This design thus achieves a balance between creating a comfortable luminous environment and maximizing natural light utilization. Furthermore, the layout of three parallel courtyards distributes high-illuminance zones evenly across the entire mansion. This configuration prevents the formation of localized “lighting dead zones” and ensures that natural light is accessible to most internal and semi-internal spaces.

4. Conclusions

Through measurement and simulation research on traditional houses integrating patios in Fuding Village of Southern China, several important conclusions are drawn, as follows:

- (1)

- In summer, when the air velocity at the gate entrance reaches up to 1 m/s, the air velocity in this courtyard varies from 0.25 m/s to 0.75 m/s, which is comfortable for living. This indicates that patio design can effectively reduce the interference of outdoor air velocity on indoor air velocity.

- (2)

- When the outdoor ambient temperature reaches as high as 34.5 °C, the average temperature in the patios is 27 °C and the indoor air temperature is 26.7 °C. A cooling effect can be achieved through natural ventilation via the water pool at the front of the courtyard. Furthermore, the energy-saving rate of ventilation is 26.2%.

- (3)

- Considering natural ventilation and daylight effects comprehensively, the depth-to-width ratio of the patio should be no less than 0.06.

- (4)

- Calculated by the adaptive comfort model, the APMV varies from 0 to 1.41. The essential elements for the ecological environment, such as sunlight, air, greenery, and water are equipped with corresponding architectural system designs. These designs can be applied to modern building design and cam promote the application of courtyards with strong regulatory functions suitable for the climatic conditions of a specific region.

Based on the limitations of this study and the requirements of field development, future research can be conducted in two dimensions for in-depth exploration. First, expand the research time dimension and climate adaptability: the current research only covers the summer season. It is necessary to supplement measurements and simulations for winter and transitional seasons, analyze the functional switching of courtyards in different seasons (such as using sunlight for thermal insulation in winter and enhancing ventilation in transitional seasons), establish an “annual dynamic adjustment model of courtyard parameters”, and improve the seasonal applicability of the conclusions. Second, promote the modernization translation of tradition technologies: explore the integration of the “courtyard regulation” principle of Wu’s quadrangle courtyard with modern architectural technologies. For example, develop new intelligent control systems adapted to courtyard ventilation, and low-energy evaporation cooling equipment based on traditional water pools for cooling, so as to realize the integration and innovation of traditional wisdom and modern technology, and provide a new path for the development of the “localization” theory in the field of architecture.

Author Contributions

X.Z.: Methodology, Investigation, Data Curation, Writing—Original Draft. K.W.: Formal Analysis, Visualization, Writing—Review & Editing. B.C.: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing—Review & Editing. J.Z.: Investigation, Data Curation, Writing—Original Draft. S.W.: Investigation, Data Curation. X.S.: Investigation, Data Curation. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The work was supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (No. DUT25Z2523), Nature Science Foundation of Liaoning Province (2025-MSLH-163), National Nature Science Foundation of China (No. 52078098, No. 51608092, No. 51578103), and Key Projects in the National Science & Technology Pillar Program during the Thirteenth Five-year Plan Period (No. 2018YFD1100701-02) of China.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Jiayi Zhao was employed by the company The Second Branch of Beijing Gas Group Co., Ltd. Author Shibo Wang was employed by the company China Southwest Architecture Design and Research Institute Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Lu, Y. Chinese Residential Architecture; South China University of Technology Press: Guangzhou, China, 2004. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Soflaei, F.; Shokouhian, M.; Zhu, W. Socio-environmental sustainability in traditional courtyard houses of Iran and China. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 69, 1147–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamani, Z.; Heidari, S.; Hanachi, P. Reviewing the thermal and microclimatic function of courtyards. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 93, 580–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulkareem, H.A. Thermal Comfort through the Microclimates of the Courtyard. A Critical Review of the Middle-eastern Courtyard House as a Climatic Response. Procedia—Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 216, 662–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hemiddi, N.A.; Al-Saud, K.A.M. The effect of a ventilated interior courtyard on the thermal performance of a house in a hot-arid region. Renew. Energy 2001, 24, 581–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soflaei, F.; Shokouhian, M.; Abraveshdar, H.; Alipour, A. The impact of courtyard design variants on shading performance in hot-arid climates of Iran. Energy Build. 2017, 143, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, F.A.; Ali, L.A. Common architectural characteristics of traditional courtyard houses in Erbil city. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2024, 15, 103003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbari, H.; Joonaghani, N.N.M. Analysis of the geometric and natural properties of courtyards in historical houses of Isfahan (Iran). J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2022, 21, 1879–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinelli, L.; Matzarakis, A. Influence of height/width proportions on the thermal comfort of courtyard typology for Italian climate zones. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2017, 29, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Bat, A.M.; Romani, Z.; Bozonnet, E.; Draoui, A.; Allard, F. Optimizing urban courtyard form through the coupling of outdoor zonal approach and building energy modeling. Energy 2023, 264, 126176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Cui, X.; Song, W.; Hao, Y. Spatial Climate Adaptation Characteristics and Optimization Strategies of Traditional Residential Courtyards in Cold Locations: A Case Study of Xiaoyi Ancient City in Shanxi Province, China. Buildings 2025, 15, 1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.Q.; Luo, Z.X.; Chen, J. Study on natural ventilation modes of patio spaces in residential buildings along the Maritime Silk Road in the South China Sea: A case study of Hainan. Tradit. Chin. Archit. Gard. Technol. 2023, 94–98. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Q.; Fan, Z.; Bai, L. Influence of space properties of enclosed patio on thermal performance in hot-humid areas of China. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2024, 15, 102370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieser, M.; Scaletti, A.; Montoya, T.; Villanueva, N.; Cisneros, S. Convection-based ventilation between courtyards in traditional houses in the city of Lima. The Riva-Aguero house. Inf. Constr. 2022, 74, e454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Li, B.; Cai, J.; Li, Y.; Qian, L. Microclimate characteristics in the famous dwellings: A case study of the Hakka Tulou in Hezhou, China. Urban Clim. 2021, 37, 100824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajapaksha, I.; Nagai, H.; Okumiya, M. A ventilated courtyard as a passive cooling strategy in the warm humid tropics. Renew. Energy 2003, 28, 1755–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, H.; Jiao, W.; Hong, J.; Anna, L. Analysis on Wind Environment in Winter of Different Rural Courtyard Layout in the Northeast. Procedia Eng. 2016, 146, 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Tang, C.; Wang, Y.; Liang, L. Measurement and Simulation Optimization of the Light Environment of Traditional Residential Houses in the Patio Style: A Case Study of the Architectural Culture of Shanggantang Village, Xiangnan, China. Buildings 2025, 15, 1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, R.; Liu, J.; Shi, Z.; Zhang, G.; Yang, W. Patio Design Optimization for Huizhou Traditional Dwellings Aimed at Daylighting Performance Improvements. Buildings 2023, 13, 583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhaisen, A.S.; Gadi, M.B. Shading performance of polygonal courtyard forms. Build. Environ. 2006, 41, 1050–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta, I.; Varela, C.; Molina, J.F.; Navarro, J.; Sendra, J.J. Energy efficiency and lighting design in courtyards and atriums: A predictive method for daylight factors. Appl. Energy 2018, 211, 1216–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuertes, P.; Sauquet, R.; Salvado, N. Patio as a structural invariant: Buildings with patio facing adaptive reuse in Barcelona. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Structural Analysis of Historical Constructions (SAHC 2021), Online, 29 September–1 October 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Han, W.; Xia, Y.; Xuan, J.; Chen, M.; Zhang, H.; Li, S.; Wang, K. Research on the Optimization of Selecting Traditional Dwellings Patio Renovation Measures in Hot Summer and Cold Winter Zone Based on Thermal Comfort and Energy Consumption. Buildings 2025, 15, 3412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Jin, Y.; Guo, J. Dynamic characteristics and adaptive design methods of enclosed courtyard: A case study of a single-story courtyard dwelling in China. Build. Environ. 2022, 223, 109445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldawoud, A.; Clark, R. Comparative analysis of energy performance between courtyard and atrium in buildings. Energy Build. 2008, 40, 209–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldawoud, A. Thermal performance of courtyard buildings. Energy Build. 2008, 40, 906–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taleghani, M.; Tenpierik, M.; den Dobbelsteen, A. Energy performance and thermal comfort of courtyard/atrium dwellings in the Netherlands in the light of climate change. Renew. Energy 2014, 63, 486–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.M. Measuring Technology on Building Environment; China Building Industry Press: Beijing, China, 2002. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- GB/T 50785-2012; Evaluation Standard for Indoor Thermal Environment in Civil Buildings. China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2012.

- Zhu, Y. Built Environment, 4th ed.; China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2017. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, X.; Chen, B.; Zhao, J.R.; Sang, Y. Numerical Simulation of Heat Transfer Process inside the Raised Floor Heating System Integrated with a Burning Cave. Renew. Energy 2019, 132, 1104–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.