Residential Satisfaction in Urban Regeneration Areas: A Multilevel Approach to Individual- and Neighborhood-Level Factors

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Individual-Level Factors and Residential Satisfaction

2.2. Neighborhood Built Environment Factors and Residential Satisfaction

2.3. The Conceptual Linkage Between Individual- and Neighborhood-Level Factors and Residential Satisfaction

3. Materials and Methods

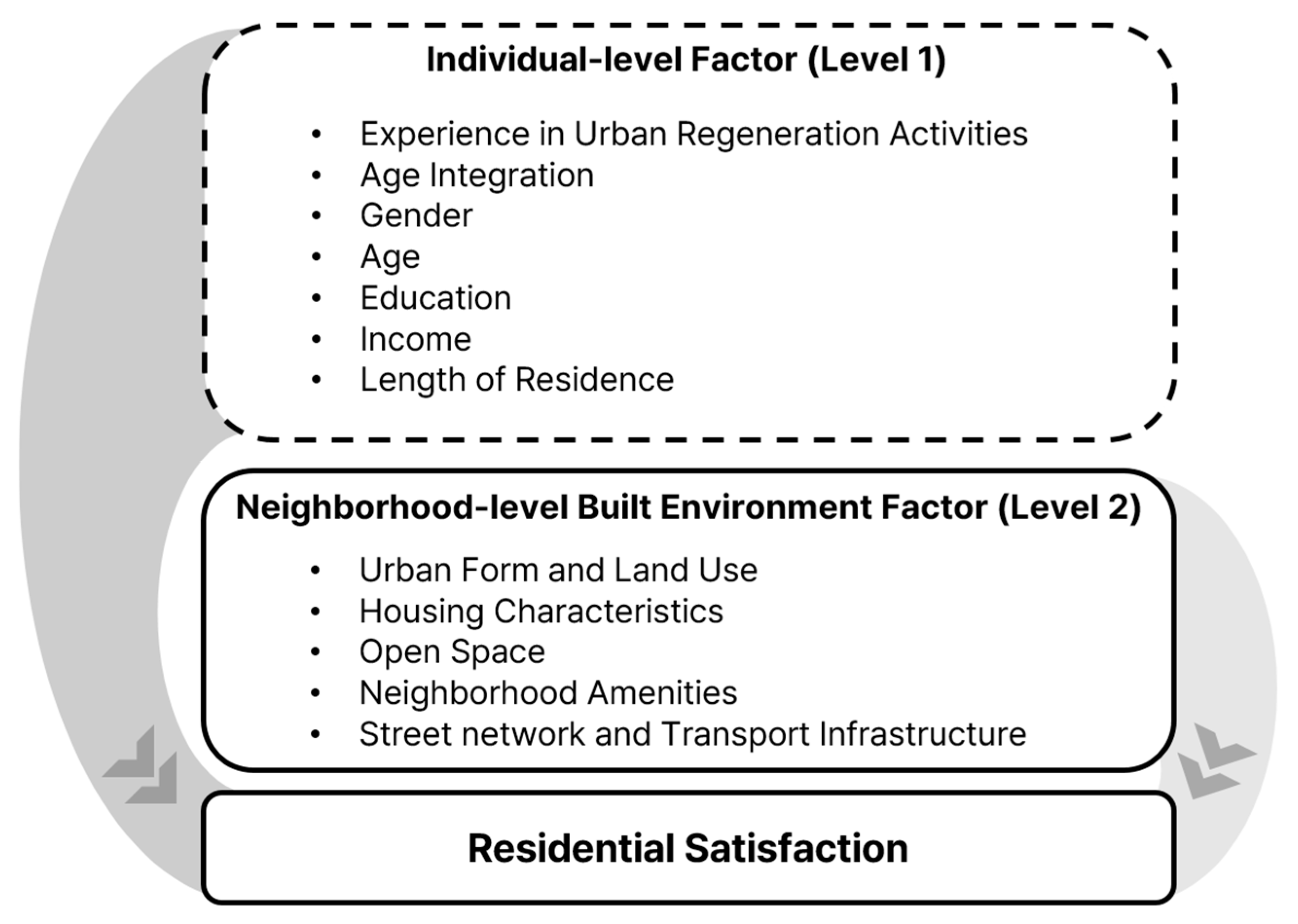

3.1. Research Design and Hypotheses

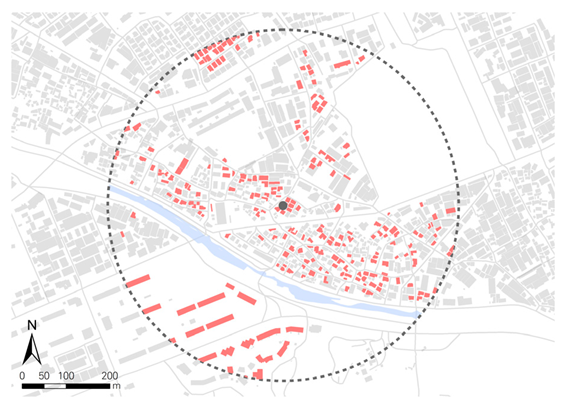

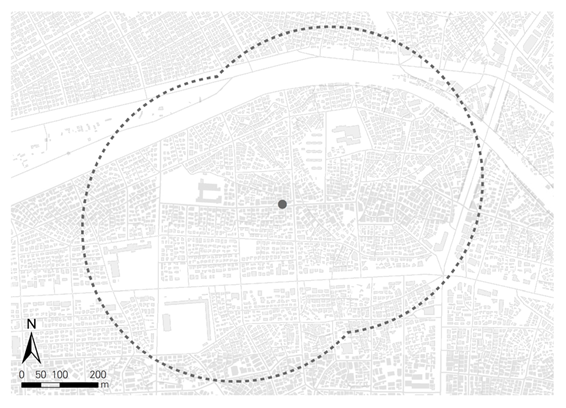

3.2. Study Area and Data

3.3. Measure

3.3.1. Residential Satisfaction

3.3.2. Individual-Level Variables (Level 1)

3.3.3. Neighborhood-Level Built Environment Variables (Level 2)

3.4. Analysis Method

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics of Variables

4.2. Multilevel Associations of Individual- and Neighborhood-Level Factors with Residential Satisfaction

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Variable | Questionnaire Items |

|---|---|

| Residential Satisfaction | I am overall satisfied with the area where I live. |

| I want to continue living in my current residential area. | |

| I feel a sense of belonging to the area where I live. | |

| I would recommend my residential area to others. | |

| Age Integration | There are leisure activity programs that allow different generations to enjoy time together. |

| There are cultural contents that can be enjoyed jointly by people of different generations. | |

| Mass media offer programs featuring older adults as main characters or primary audiences. | |

| Clubs or social groups include members of diverse age groups, from young children to older adults. | |

| Universities provide various learning opportunities and courses for middle-aged and older adults. | |

| Older adults and younger people understand each other and socialize together. | |

| People of different ages study together in the same classroom. | |

| Older and younger generations make efforts to understand each other’s values. | |

| Promotion opportunities are offered based on individual ability rather than age. | |

| Individuals can enter the labor market at any time if they wish, regardless of age. | |

| Employers make hiring decisions based on applicants’ competence or experience, not their age. | |

| Knowledge, skills, and experience are shared between younger and older workers in the workplace. | |

| Both younger and older adults receive income security from the state on an equal basis. |

References

- Afacan, Y. Resident satisfaction for sustainable urban regeneration. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. Municipal Eng. 2015, 168, 220–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amérigo, M.a.; Aragones, J.I. A theoretical and methodological approach to the study of residential satisfaction. J. Environ. Psychol. 1997, 17, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, B.; Sultana, Z.; Priovashini, C.; Ahsan, M.N.; Mallick, B. The emergence of residential satisfaction studies in social research: A bibliometric analysis. Habitat Int. 2021, 109, 102336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Pellegrini, P.; Xu, Y.; Ma, G.; Wang, H.; An, Y.; Shi, Y.; Feng, X. Evaluating residents’ satisfaction before and after regeneration. The case of a high-density resettlement neighbourhood in Suzhou, China. Campbell Syst. Rev. 2022, 8, 2144137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Kamp, I.; Leidelmeijer, K.; Marsman, G.; De Hollander, A. Urban environmental quality and human well-being: Towards a conceptual framework and demarcation of concepts; a literature study. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2003, 65, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouratidis, K. Neighborhood characteristics, neighborhood satisfaction, and well-being: The links with neighborhood deprivation. Land Use Policy 2020, 99, 104886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Permentier, M.; Bolt, G.; Van Ham, M. Determinants of neighbourhood satisfaction and perception of neighbourhood reputation. Urban Stud. 2011, 48, 977–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Liu, N.; Chen, J.; Guo, S. The relationship between urban renewal and the built environment: A systematic review and bibliometric analysis. J. Plann. Lit. 2022, 37, 293–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Yan, Y.; Zhang, X.; Chen, J. A study on the impact of built environment elements on satisfaction with residency whilst considering spatial heterogeneity. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohit, M.A.; Ibrahim, M.; Rashid, Y.R. Assessment of residential satisfaction in newly designed public low-cost housing in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Habitat Int. 2010, 34, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouratidis, K.; Yiannakou, A. What makes cities livable? Determinants of neighborhood satisfaction and neighborhood happiness in different contexts. Land Use Policy 2022, 112, 105855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Dong, G.; Yun, Y. Contextualized effects of Park access and usage on residential satisfaction: A spatial approach. Land Use Policy 2020, 94, 104532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olfindo, R. Transport accessibility, residential satisfaction, and moving intention in a context of limited travel mode choice. Transp. Res. A Policy Pract. 2021, 145, 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.J.; Wang, D. Environmental correlates of residential satisfaction: An exploration of mismatched neighborhood characteristics in the Twin Cities. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2016, 150, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojo Perez, F.; Fernandez-Mayoralas Fernandez, G.; Pozo Rivera, E.; Manuel Rojo Abuin, J. Ageing in place: Predictors of the residential satisfaction of elderly. Soc. Indic. Res. 2001, 54, 173–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balestra, C.; Sultan, J. Home Sweet Home: The Determinants of Residential Satisfaction and Its Relation with Well-Being; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development: Paris, France, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.-J.; Bo, T. A Study on Housing Situation and Residential Satisfaction of Foreigners in Korea-Focusing on Seoul and Kyonggi Province. J. Korea Contents Assoc. 2019, 19, 574–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Türkoğlu, H.; Terzi, F.; Salihoğlu, T.; Bölen, F.; Okumuş, G. Residential satisfaction in formal and informal neighborhoods: The case of Istanbul, Turkey. Archnet-ijar Int. J. Archit. Res. 2019, 13, 112–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Wang, T.; Gu, S. A study of resident satisfaction and factors that influence old community renewal based on community governance in Hangzhou: An empirical analysis. Land 2022, 11, 1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohe, W.M.; Basolo, V. Long-term effects of homeownership on the self-perceptions and social interaction of low-income persons. Environ. Behav. 1997, 29, 793–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talen, E. Sense of community and neighbourhood form: An assessment of the social doctrine of new urbanism. Urban Stud. 1999, 36, 1361–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, T.; Zeng, N.; Huang, Y.; Vejre, H. Relationship between the dynamics of social capital and the dynamics of residential satisfaction under the impact of urban renewal. Cities 2020, 107, 102933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzo, L.C.; Perkins, D.D. Finding common ground: The importance of place attachment to community participation and planning. J. Plan. Lit. 2006, 20, 335–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, Y.; Joo, H. Determinants of Resident Satisfaction with Urban Renewal Projects Focusing on South Gyeongsang Province in South Korea. Int. Rev. Spat. Plan. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 9, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- In, S.H. A Study on the Effect of Resident Perception of Urban Regeneration Project on Local Identity and Resident Satisfaction. Korea Real Estate Acad. Rev. 2022, 8, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, E.; Lee, W.; Kim, D. Does resident participation in an urban regeneration project improve neighborhood satisfaction: A case study of “Amichojang” in Busan, South Korea. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, N. Analysis of Factors Affecting Life Satisfaction of Local Residents in Urban Regeneration Projects: Focused on General Type of Neighborhood Regeneration in Seoul. J. Econ. Geogr. Soc. Korea 2021, 24, 425–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varjakoski, H.; Koponen, S.; Kouvo, A.; Tiilikainen, E. Age diversity in neighborhoods—A mixed-methods approach examining older residents and community wellbeing. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Siu, K.W.M.; Zhang, L. Intergenerational integration in community building to improve the mental health of residents—A case study of public space. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moorman, S.M.; Stokes, J.E.; Morelock, J.C. Mechanisms linking neighborhood age composition to health. Gerontologist 2017, 57, 667–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whear, R.; Campbell, F.; Rogers, M.; Sutton, A.; Robinson-Carter, E.; Sharpe, R.; Cohen, S.; Fergy, R.; Garside, R.; Kneale, D. What is the effect of intergenerational activities on the wellbeing and mental health of older people?: A systematic review. Campbell Syst. Rev. 2023, 19, e1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.Y.; Kim, E.J. Effects of Community and Life Satisfaction on Awareness of Age Integration: Targeting Local Residents of Urban Regeneration Projects. Korea Spat. Plan. Rev. 2025, 126, 165–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirgy, M.J.; Cornwell, T. How neighborhood features affect quality of life. Soc. Indic. Res. 2002, 59, 79–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; He, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, D. Impact of building environment on residential satisfaction: A case study of Ningbo. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, M.; Nasar, J.L.; Chun, B. Neighborhood satisfaction, physical and perceived naturalness and openness. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezazadeh, R.; Latifi Oskouei, L. The Role of Neighborhood Walk Ability on Residential Satisfaction, Case Study: Chizar Neighborhood. Allg. Arbeiter Union Dtschl. 2015, 7, 321–331. [Google Scholar]

- Vichiensan, V.; Nakamura, K. Walkability perception in Asian cities: A comparative study in Bangkok and Nagoya. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabah, F.Y. Assessment of residential satisfaction with internationally funded housing projects in Gaza Strip, Palestine. Front. Built Environ. 2023, 9, 1289707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shareck, M.; Aubé, E.; Sersli, S. Neighborhood physical and social environments and social inequalities in health in older adolescents and young adults: A scoping review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Feng, T.; Timmermans, H.; Li, H. A gap-theoretical path model of residential satisfaction and intention to move house applied to renovated historical blocks in two Chinese cities. Cities 2017, 71, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, D.; Ning, X.; Sun, J.; Du, H. Residential satisfaction among resettled tenants in public rental housing in Wuhan, China. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2019, 34, 1125–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buffel, T.; Phillipson, C.; Scharf, T. Ageing in urban environments: Developing ‘age-friendly’cities. Crit. Soc. Policy 2012, 32, 597–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiles, J.L.; Leibing, A.; Guberman, N.; Reeve, J.; Allen, R.E. The meaning of “aging in place” to older people. Gerontologist 2012, 52, 357–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekker, K.; De Vos, S.; Musterd, S.; Van Kempen, R. Residential satisfaction in housing estates in European cities: A multi-level research approach. Hous. Stud. 2011, 26, 479–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto-Flores, M.-E.; Fernandez-Mayoralas, G.; Forjaz, M.J.; Rojo-Perez, F.; Martinez-Martin, P. Residential satisfaction, sense of belonging and loneliness among older adults living in the community and in care facilities. Health Place 2011, 17, 1183–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KOSIS. Available online: https://kosis.kr/ (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Special Act on the Promotion and Support for Urban Regeneration; Act No. 11965; Government of the Republic of Korea: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2013.

- Zhang, Z.; Wei, Q. Residential Satisfaction and Sense of Belonging Under the ‘Moving-Merging’ Resettlement Strategy in Shanghai. Herd-health Environ. Res. Des. J. 2025, 18, 146–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.; Luo, X.; Guo, S.; Xie, M.; Zhou, J.; Huang, R.; Zhang, Z. Validation of the abbreviated indicators of perceived residential environment quality and neighborhood attachment in China. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 925651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, S.; Lim, J.-s. Validation of Short Form Age Integration Scale and Relationships between Socio-Demographic Characteristics and Age Integration: A Comparison of Age Groups. J. Korean Gerontol. Soc. 2020, 40, 73–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormack, G.R.; Koohsari, M.J.; Vena, J.E.; Oka, K.; Nakaya, T.; Chapman, J.; Martinson, R.; Matsalla, G. Associations between neighborhood walkability and walking following residential relocation: Findings from Alberta’s Tomorrow Project. Front. Public Health 2023, 10, 1116691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Tan, P.Y. Associations between urban green spaces and health are dependent on the analytical scale and how urban green spaces are measured. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aarts, E.; Verhage, M.; Veenvliet, J.V.; Dolan, C.V.; Van Der Sluis, S. A solution to dependency: Using multilevel analysis to accommodate nested data. Nat. Neurosci. 2014, 17, 491–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hox, J.; Moerbeek, M.; Van de Schoot, R. Multilevel Analysis: Techniques and Applications, 3rd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Snijders, T.A.; Bosker, R. Multilevel Analysis: An Introduction to Basic and Advanced Multilevel Modeling, 2nd ed.; Sage: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Maas, C.J.; Hox, J.J. Robustness issues in multilevel regression analysis. Stat. Neerl. 2004, 58, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gascon, M.; Zijlema, W.; Vert, C.; White, M.P.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M.J. Outdoor blue spaces, human health and well-being: A systematic review of quantitative studies. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. 2017, 220, 1207–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mygind, L.; Kjeldsted, E.; Hartmeyer, R.; Mygind, E.; Stevenson, M.P.; Quintana, D.S.; Bentsen, P. Effects of public green space on acute psychophysiological stress response: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the experimental and quasi-experimental evidence. Environ. Behav. 2021, 53, 184–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twohig-Bennett, C.; Jones, A. The health benefits of the great outdoors: A systematic review and meta-analysis of greenspace exposure and health outcomes. Environ. Res. 2018, 166, 628–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, M.P.; Elliott, L.R.; Gascon, M.; Roberts, B.; Fleming, L.E. Blue space, health and well-being: A narrative overview and synthesis of potential benefits. Environ. Res. 2020, 191, 110169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, I.; Seo, S.; Sim, H. Diagnosis of Current Issues and Future Tasks of Regeneration Policy in Local Small and Medium-Sized Cities; AURI: Sejong, Republic of Korea, 2024. [Google Scholar]

| URCF | Selection Year | Project Period | Opening Date | Major Facilities (Key Spaces; Inventory) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dalseong | 2019 | Jan. 2019–Dec. 2024 | Jun. 2024 | Café; learning room; shared community room; fitness/training room; club/activity room |

| Hyomok | 2017 | Aug. 2018–Dec. 2022 | Dec. 2023 | Youth center; daycare room; multipurpose meeting room; café/community lounge |

| Wongogae | 2015 | Jan. 2016–Dec. 2021 | Apr. 2021 | Multipurpose rooms; laundry facility; shared kitchen; youth space |

| Indongchon | 2018 | Jan. 2019–Dec. 2024 | Mar. 2023 | Senior center; shared kitchen; lecture/class rooms; computer room; calligraphy room; fitness/training room; auditorium; meeting rooms |

| Chimsan | 2017 | Aug. 2018–Dec. 2022 | Oct. 2023 | Café; senior center; mental-health welfare center; cooperative office; workshop/maker space; community gym |

| Cheukbaekhyang | 2015 | Jan. 2016–Jun. 2021 | Apr. 2021 | Local-food store; convenience store; café |

| Variable | Measurement | Data Source | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Residential Satisfaction | 5-point scale | Survey | |

| Individual-level variables (Level 1) | |||

| Experience in Urban Regeneration Activities | 1 = Yes, 0 = No | Survey | |

| Age Integration Gender | 5-point scale | ||

| 1 = Female, 0 = Male | |||

| Age | 1 = 18–29, 2 = 30–39, 3 = 40–49, 4 = 50–59, 5 = 60–69, 6 = 70 or older | ||

| Education | 1 = Elementary school or lower, 2 = Middle school graduate, 3 = High school graduate, 4 = College graduate or higher | ||

| Income | 1 = Less than 1 million KRW, 2 = 1–2 million KRW, 3 = 2–3 million KRW, 4 = 3–4 million KRW, 5 = 4–5 million KRW, 6 = More than 5 million KRW | ||

| Length of Residence | 1 = Less than 1 year, 2 = 1–3, 3 = 3–5, 4 = 5–10, 5 = More than 10 years | ||

| Neighborhood-level Built Environment variables (Level 2) | |||

| Urban Form and Land Use | Mean Slope | Mean slope (°) | National Spatial Data |

| Land Use Mix (LUM) | Land Use Mix Index (0–1) | Environmental Space Information Service | |

| Housing Characteristics | Proportion of Old Housing | Percentage of Old Housing (%) | National Spatial Data |

| Proportion of Multi-Family Housing | Percentage of Multi-Family Housing (%) | ||

| Open Space | Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) | Mean NDVI (−1–1) | United States Geological Survey (USGS) |

| Proportion of Water Area | Percentage of Water Area (%) | Road Name Address | |

| Neighborhood Amenities | Hospital density | Number of Hospitals (count/km2) | Local Data |

| Pharmacy density | Number of Pharmacies (count/km2) | ||

| Retail Shop density | Number of Retail Shops (count/km2) | ||

| Senior Center density | Number of Senior Centers (count/km2) | ||

| Street network and Transport Infrastructure | Intersection density | Number of Intersections (count/km2) | Road Name Address |

| Bus Stop density | Number of Bus Stops (count/km2) | National Spatial Data | |

| Distance to Subway Station | Distance to the Nearest Subway Station Entrance (m) | ||

| Variable | Measurement | Dalseong URCF | Hyomok URCF | Wongogae URCF | Indongchon URCF | Chimsan URCF | Cheukbaek Hyang URCF | URCF Mean (All Sites) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 59 | 28 | 48 | 66 | 61 | 19 | 281 | ||

| Mean (SD) | |||||||||

| Residential Satisfaction | 5-point scale | 3.77 (0.68) | 3.45 (0.77) | 3.31 (0.82) | 3.39 (0.98) | 3.44 (0.78) | 3.61 (1.01) | 3.49 (0.85) | |

| Individual-level variables (Level 1) | |||||||||

| Age Integration | 5-point scale | 2.85 (0.57) | 2.76 (0.57) | 3.03 (0.58) | 3.20 (0.75) | 2.76 (0.54) | 2.32 (0.66) | 2.90 (0.66) | |

| Count (%) | |||||||||

| Experience in Urban Regeneration Activities | Yes | 24 (40.7) | 9 (32.1) | 21 (43.8) | 9 (13.6) | 20 (32.8) | 3 (15.8) | 86 (30.6) | |

| No | 35 (59.3) | 19 (67.9) | 27 (56.3) | 57 (86.4) | 41 (67.2) | 16 (84.2) | 195 (69.4) | ||

| Gender | Male | 21 (35.6) | 11 (39.3) | 11 (22.9) | 24 (36.4) | 24 (39.3) | 8 (42.1) | 99 (35.2) | |

| Female | 38 (64.4) | 17 (60.7) | 37 (77.1) | 42 (63.6) | 37 (60.7) | 11 (57.9) | 182 (64.8) | ||

| Age | 18–29 | 1 (1.7) | 6 (21.4) | 16 (33.3) | 1 (1.5) | 7 (11.5) | 3 (15.8) | 34 (12.1) | |

| 30–39 | 1 (1.7) | 7 (25.0) | 2 (4.2) | 3 (4.5) | 17 (27.9) | 7 (36.8) | 37 (13.2) | ||

| 40–49 | 6 (10.2) | 3 (10.7) | 5 (10.4) | 4 (6.1) | 10 (16.4) | 0 (0.0) | 28 (10.0) | ||

| 50–59 | 13 (22) | 4 (14.3) | 18 (37.5) | 8 (12.1) | 7 (11.5) | 6 (31.6) | 56 (19.9) | ||

| 60–69 | 29 (49.2) | 7 (25) | 4 (8.3) | 15 (22.7) | 13 (21.3) | 2 (10.5) | 70 (24.9) | ||

| 70 or older | 9 (15.3) | 1 (3.6) | 3 (6.3) | 35 (53.0) | 7 (11.5) | 1 (5.3) | 56 (19.9) | ||

| Education | Elementary school or lower | 3 (5.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.1) | 22 (33.3) | 2 (3.3) | 1 (5.3) | 29 (10.3) | |

| Middle school graduate | 7 (11.9) | 1 (3.6) | 3 (6.3) | 12 (18.2) | 8 (13.1) | 0 (0.0) | 31 (11.0) | ||

| High school graduate | 21 (35.6) | 6 (21.4) | 27 (56.3) | 20 (30.3) | 25 (41.0) | 4 (21.1) | 103 (36.7) | ||

| College graduate or higher | 28 (47.5) | 21 (75.0) | 17 (35.4) | 12 (18.2) | 26 (42.6) | 14 (73.7) | 118 (42.0) | ||

| Income | Less than 1 million KRW | 14 (23.7) | 6 (21.4) | 18 (37.5) | 43 (65.2) | 13 (21.3) | 1 (5.3) | 95 (33.8) | |

| 1–2 million KRW | 8 (13.6) | 4 (14.3) | 18 (37.5) | 12 (18.2) | 10 (16.4) | 2 (10.5) | 54 (19.2) | ||

| 2–3 million KRW | 13 (22.0) | 9 (32.1) | 6 (12.5) | 5 (7.6) | 12 (19.7) | 9 (47.4) | 54 (19.2) | ||

| 3–4 million KRW | 8 (13.6) | 5 (17.9) | 6 (12.5) | 4 (6.1) | 13 (21.3) | 4 (21.1) | 40 (14.2) | ||

| 4–5 million KRW | 12 (20.3) | 2 (7.1) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (3) | 5 (8.2) | 0 (0.0) | 21 (7.5) | ||

| More than 5 million KRW | 4 (6.8) | 2 (7.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0) | 8 (13.1) | 3 (15.8) | 17 (6.0) | ||

| Length of Residence | Less than 1 year | 0 (0) | 1 (3.6) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 5 (8.2) | 0 (0) | 6 (2.1) | |

| 1–3 | 4 (6.8) | 1 (3.6) | 1 (2.1) | 3 (4.5) | 6 (9.8) | 1 (5.3) | 16 (5.7) | ||

| 3–5 | 5 (8.5) | 3 (10.7) | 1 (2.1) | 2 (3.0) | 5 (8.2) | 4 (21.1) | 20 (7.1) | ||

| 5–10 | 5 (8.5) | 6 (21.4) | 4 (8.3) | 7 (10.6) | 5 (8.2) | 1 (5.3) | 28 (10.0) | ||

| More than 10 years | 45 (76.3) | 17 (60.7) | 42 (87.5) | 54 (81.8) | 40 (65.6) | 13 (68.4) | 211 (75.1) | ||

| Neighborhood-level Built Environment variables (Level 2) | Unit | ||||||||

| Urban Form and Land Use | Mean Slope | ° | 1.2 | 1.4 | 1.2 | 0.9 | 2.5 | 3.9 | 1.9 |

| LUM | - | 0.771 | 0.822 | 0.442 | 0.557 | 0.809 | 0.417 | 0.636 | |

| Housing Characteristics | Proportion of Old Housing | % | 75.9 | 96.3 | 98.2 | 93.5 | 93.8 | 81.9 | 89.9 |

| Proportion of Multi-Family Housing | 10.2 | 6.5 | 9.0 | 8.9 | 12.1 | 0.0 | 7.8 | ||

| Open Space | NDVI | - | 0.182 | 0.133 | 0.106 | 0.104 | 0.174 | 0.331 | 0.172 |

| Proportion of Water Area | % | 2.63 | 0.01 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6.75 | 1.57 | |

| Neighborhood Amenities | Hospital density | count/km2 | 54 | 70 | 11 | 44 | 6 | 0 | 31 |

| Pharmacy density | 18 | 28 | 6 | 20 | 6 | 0 | 13 | ||

| Retail Shop density | 26 | 54 | 84 | 90 | 40 | 4 | 50 | ||

| Senior Center density | 14 | 4 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 2 | 9 | ||

| Street network and Transport Infrastructure | Intersection density | 916 | 1185 | 1805 | 1358 | 759 | 327 | 1058 | |

| Bus Stop density | 145 | 75 | 394 | 168 | 737 | 8 | 255 | ||

| Distance to Subway Station | m | 360.9 | 1378.8 | 1456.4 | 930.4 | 865.4 | 4590.4 | 1597.1 | |

| Variable | β | SE | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual-level variables (Level 1) | (Intercept) | 3.57 | 0.07 | 52.18 | 0.02 |

| Experience in Urban Regeneration Activities (Yes = 1) | 0.06 * | 0.04 | 1.73 | 0.08 | |

| Age Integration | 0.25 *** | 0.04 | 6.83 | <0.001 | |

| Gender (Female = 1) | −0.02 | 0.04 | −0.49 | 0.63 | |

| Age | 0.63 *** | 0.05 | 12.60 | <0.001 | |

| Education | −0.05 | 0.04 | −1.20 | 0.23 | |

| Income | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.93 | 0.35 | |

| Length of Residence | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.85 | 0.40 | |

| Neighborhood-level Built Environment variables (Level 2) | Proportion of Old Housing | −0.38 * | 0.32 | −1.18 | 0.06 |

| NDVI | 0.26 * | 0.26 | 1.01 | 0.07 | |

| Proportion of Water Area | 0.20 ** | 0.15 | 1.30 | 0.03 | |

| Bus Stop Density | −0.09 | 0.11 | −0.84 | 0.14 | |

| N | 281 | ||||

| ICC | 0.121 | ||||

| R2 | 0.433 | ||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.501 | ||||

| (1) Dalseong URCF | (2) Hyomok URCF | (3) Wongogae URCF | (4) Indongchon URCF | (5) Chimsan URCF | (6) Cheukbaekhyang URCF | Bar Chart |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proportion of Old Housing | ||||||

|  |  |  |  |  |  |

| 75.9% | 96.3% | 98.2% | 93.5% | 93.8% | 81.9% | |

| NDVI | ||||||

|  |  |  |  |  |  |

| 0.182 | 0.133 | 0.106 | 0.104 | 0.174 | 0.331 | |

| Proportion of Water Area | ||||||

|  |  |  |  |  |  |

| 2.6% | 0.01% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 6.75% | |

| Residential Satisfaction | ||||||

| 3.77 | 3.45 | 3.31 | 3.39 | 3.44 | 3.61 | |

| ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kim, E.J.; Sim, H. Residential Satisfaction in Urban Regeneration Areas: A Multilevel Approach to Individual- and Neighborhood-Level Factors. Buildings 2026, 16, 213. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010213

Kim EJ, Sim H. Residential Satisfaction in Urban Regeneration Areas: A Multilevel Approach to Individual- and Neighborhood-Level Factors. Buildings. 2026; 16(1):213. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010213

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Eun Jung, and Hyemin Sim. 2026. "Residential Satisfaction in Urban Regeneration Areas: A Multilevel Approach to Individual- and Neighborhood-Level Factors" Buildings 16, no. 1: 213. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010213

APA StyleKim, E. J., & Sim, H. (2026). Residential Satisfaction in Urban Regeneration Areas: A Multilevel Approach to Individual- and Neighborhood-Level Factors. Buildings, 16(1), 213. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings16010213