Abstract

Strength and the permeability coefficient are recognized as the two main design parameters for permeable concrete. Although adding an appropriate amount of nano-silica (NS) can enhance the slurry strength and enhance the bond between the aggregate and cementitious material, research on the combined effects of porosity and NS on the behavior of permeable concrete is limited. An experimental program was carried out to demonstrate the impact of NS on the permeability (K) and strength (fc) of permeable concrete. The tested variables included the NS content (0, 0.5, 1.0, 1.5, 2.0, and 2.5%) and the porosity (p = 15, 20, and 25%), following the identification of an optimal water-to-binder (w/b) ratio of 0.3. It was found that the addition of NS alters the failure mechanism by transferring the critical failure location from the cementitious matrix to aggregate particles. An additive of 1% NS shows the most significant enhancement in the concrete strength, with improvement efficacy increasing substantially with the porosity. Specifically, the 28-day strength of permeable concrete modified with 1% NS increased by 6.4%, 16.1%, and 38.5% for mixes with 15%, 20%, and 25% porosity, respectively. Meanwhile, NS improves the permeability with 0.5% dosage, providing the most effective enhancement. Finally, an empirical expression between permeability and porosity was developed based on the test results, which allows engineers to calculate the required porosity (e.g., p ≈ 17% for K = 1.0 cm/s) to meet specific permeability in pavement applications.

1. Introduction

Urban expansion has progressively replaced natural permeable landscapes with impermeable surfaces such as conventional concrete and asphalt, used extensively in roads, parking lots, and sidewalks [1,2]. This shift has triggered a range of hydrological and environmental issues, including intensified stormwater runoff that exceeds drainage capacity and elevates flood risks. Moreover, these surfaces impede heat and moisture exchange with the atmosphere, leading to the urban heat island effect that raises energy demands for cooling, increases CO2 emissions, and exacerbates the greenhouse effect [3,4]. Additional repercussions include reduced tire-pavement friction, compromising traffic safety, hindered groundwater recharge due to limited stormwater infiltration, impaired vegetation growth from insufficient soil moisture, and regulatory challenges linked to stormwater management requirements [5]. Accordingly, permeable concrete (PC) has emerged as a sustainable paving alternative aimed at mitigating these adverse urbanization impacts.

PC consists of single-sized or open-graded coarse aggregates bonded by a thin cementitious matrix with minimal fine aggregates, exhibiting high water permeability that mitigates urban flooding and heat island effects while reducing noise pollution [6,7,8,9,10]. However, its high porosity leads to inferior mechanical strength compared to conventional concrete, restricting broader structural application. The behavior of permeable concrete is intrinsically governed by its microstructure. Load transfer occurs predominantly through the points of contact between coarse aggregates, facilitated by the strength and integrity of the Interfacial Transition Zone (ITZ) and the cement paste bridges that bind them [11,12]. The ITZ, often the weakest phase in conventional concrete, becomes critically more influential in permeable concrete due to the minimal paste volume. A porous or mechanically deficient ITZ, coupled with the inherent stress concentrations at aggregate contact points, makes the material highly susceptible to failure under load [13]. Traditional strategies to enhance strength often involve compromising its permeability. For instance, incorporating fine aggregates or using smaller, graded coarse aggregates can increase the bonding area and density, thereby improving strength, but this inevitably reduces the pore space and connectivity, diminishing permeability [14,15]. Therefore, the central challenge in advancing permeable concrete technology lies in enhancing its mechanical properties without adversely affecting its vital porosity and permeability characteristics. The most promising pathway to achieving this is not by altering the pore structure itself, but by fundamentally strengthening the constituents that form the skeletal matrix—specifically, by reinforcing the cement paste and the ITZ.

Nanotechnology offers groundbreaking potential, with nano-silica (NS) standing out as a particularly effective modifier. NS particles, typically with diameters ranging from 5 to 100 nanometers, impart a dual mechanism of enhancement in cementitious systems [16,17,18,19]. First, due to its remarkable pozzolanic activity, NS quickly consumes the calcium hydroxide (CH) produced as a low-strength residue in cement hydration. This process yields additional calcium silicate hydrate (C-S-H) gel, the primary phase that imparts strength to the cement matrix. Second, its ultrafine particles act as a potent nano-filler, densifying the microstructure of both the cement paste and the critical ITZ by occupying nanoscale voids that would otherwise remain as pores. This synergetic effect leads to a denser, stronger, and more durable binder phase.

A growing body of literature confirms the benefits of NS in permeable concrete, where many studies have reported significant improvements in compressive and flexural strength. For instance, Shirgir et al. [19] observed a 48% increase in compressive strength with a 7% NS dosage, while Zhong and Wille [20] further highlighted a critical practical consideration, noting that permeable concrete mixtures incorporating pozzolanic materials like FA exhibit significant sensitivity to molding pressure during compaction. Mohammed et al. [21] indicated that a 3% NS addition with FA boosted concrete strength without altering the void ratio or permeability [21], whereas the void ratio and permeability remained unchanged. Furthermore, NS contributed to environmentally functional properties in such composites. The application of NS also extends to environmental functionality. Alighardashi et al. [22] tested PC for nitrate removal, finding that a mix with 6% NS and 20% fine aggregates achieved over 70% nitrate elimination while also improving mechanical properties. Other researchers, including Hosseini [23], Debnath et al. [24] and Rahul et al. [25], have further validated that optimal NS dosages (typically between 1 and 4%) can yield an excellent balance between strength development and permeability retention in various mix designs.

While numerous studies have established that the advantage of NS in strength enhancement, many have focused on a single and fixed porosity or a narrow range, often without systematically considering the coupling effects of porosity and NS content. The interplay between these two parameters, i.e., one a macro-structural design choice (porosity) and the other a nano-scale reinforcement strategy (NS), is not yet fully quantified. As recently reported by Liu et al. [26], porosity experienced a dominant impact on both strength and permeability. Increasing the porosity resulted in a substantial growth rate in the permeability coefficient while the compressive strength shows a notable reduction efficiency. While Sun et al. [27] reported that NS addition typically reduced permeability due to its pore-filling effect and densification of the matrix, its influence on fresh-state properties, especially paste cohesiveness and aggregate-coating ability, may yield a different outcome in highly porous systems. In permeable concrete, a common issue is the downward migration of cement paste under gravity during placement, which can clog interconnected pores at the bottom and reduce effective permeability. We hypothesize that by enhancing the viscosity and adhesion of the fresh paste, an optimal dosage of NS can promote more uniform coating of aggregates, minimize paste drainage, and thereby better preserve the designed pore connectivity. Therefore, this study investigates whether, under carefully controlled mix proportions and placement conditions, NS can concurrently enhance both strength and permeability. This can be an interesting discovery that has not been fully explored in previous work focusing on fixed or limited porosity ranges. There remains a lack of a comprehensive experimental framework that first identifies the optimal w/b ratio and then systematically investigates how the efficacy of NS varies across a wide and practical spectrum of design porosities. Furthermore, while the negative correlation between porosity and strength is well-documented, a quantitative model linking design target porosity to the resulting permeability for NS-modified permeable concrete is scarcely available in the literature. Establishing such a predictive relationship would enable a performance-based design approach where engineers can first determine the required porosity based on hydrological demands and then confidently select the optimal NS content to meet the concomitant strength requirements.

To determine the synergistic effect of NS content and porosity on the performance of permeable concrete, this paper presents a laboratory experimental evaluation regarding the strength and permeability improvement of NS-modified permeable concrete. The primary objectives are threefold: (i) to determine the optimal w/b ratio that provides the best balance of workability and hardened properties, serving as a baseline for subsequent modifications; (ii) to investigate the effect of NS content (0% to 2.5%) on the strength and permeability coefficient through a systematic experimental program; and (iii) to develop an empirical equation, based on data for mixtures containing 1% NS and porosities ranging from 15% to 25%, that describes the relationship between porosity and permeability for NS-modified permeable concrete. By elucidating the synergistic effects of porosity and NS, the findings are expected to provide a scientific and practical framework for the design of high-performance permeable concrete.

2. Research Significance

Permeability and mechanical strength are the two most critical properties governing the practical application of permeable concrete. While the incorporation of NS is recognized as an effective method for enhancing the typically low strength of such materials, excessive porosity may counteract this benefit. Although the performance of conventional permeable concrete has been widely studied, systematic research on how NS content and porosity influence the performance of NS-modified permeable concrete remains limited. This study therefore aims to bridge this gap. Its primary contributions are twofold: first, to quantitatively evaluate the combined effects of NS dosage and design porosity on the 7d and 28d compressive strength and permeability coefficient; second, to identify an optimal NS content and establish a practical porosity versus permeability relationship for designing NS-modified permeable concrete that meets specific hydrological and structural requirements.

3. Experimental Program

This experiment focuses on the performance of permeable concrete modified with NS additive, targeting three porosity levels ranging from 15 to 25% and six NS contents (0%, 0.5%, 1.0%, 1.5%, 2.0%, and 2.5% by weight of cement). The primary objective of this section is to quantitatively investigate the interplay between porosity and NS content on the performance of permeable concrete, aiming to identify the optimal NS dosage that achieves the desired balance between strength and permeability. In all mixtures, 10% of the cement by mass was consistently replaced with FA. This replacement level was selected based on common practices in permeable concrete mix design, as it is known to improve particle packing, enhance workability, and contribute to long-term pozzolanic reactivity without significantly compromising the open pore structure essential for permeability [20].

3.1. Raw Materials

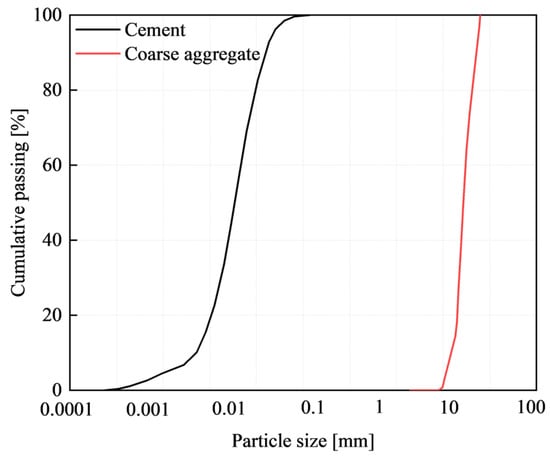

The primary materials utilized in this investigation included P.·O. 42.5 grade ordinary Portland cement (supplied by Jilin Yatai Cement Co., Ltd., Changchun, China), NS (obtained from Gongyi City PuRui Refractory Materials Co., Ltd., Zhengzhou, China), and fly ash (FA) (provided by Gongyi City PuRui Refractory Materials Co., Ltd., Zhengzhou, China). In addition, a water-reducing agent (supplied by Hangzhou Wanjing New Materials Co., Ltd., Hangzhou, China was employed. The properties of cement are detailed in Table 1 and Table 2, respectively. The properties of FA and NS are summarized in Table 3 and Table 4, respectively. For coarse aggregates, single-sized gravel with a particle size range of 10~20 mm was used. The particle distribution curve is shown in Figure 1. The properties included an apparent density of 2870 kg/m3, a clay content of 0.4%, a needle and flake particle content of 2.2%, a compacted bulk porosity of 46%, and a crush value of 6.4%.

Table 1.

Properties of the employed cement.

Table 2.

Chemical properties of cement.

Table 3.

Physicochemical properties of FA.

Table 4.

Properties of NS.

Figure 1.

Particle size gradation curve.

3.2. Mix Proportion

Two distinct series of mixtures were designed for this study. The first series, plain permeable concrete (PPC), was employed to estimate the optimal w/b ratio. The mixing procedure adopted the method established by Liu et al. [26], with the modification that 10% of the cement by mass was consistently replaced with FA in all mixtures. A second series, designated as PCNS, was prepared by further augmenting the mixtures with NS at dosages of 0.5%, 1.0%, 1.5%, 2.0%, and 2.5% by mass of cement. In both the PPC and nano-silica modified (PCNS) series, FA was incorporated as a fixed component, replacing 10% of the cement by mass in all mixes. This consistent FA content serves as a background binder that moderates paste rheology and supports hydration, allowing the effects of NS dosage and porosity to be evaluated against a stable and practically relevant baseline.

An experimental program was first conducted on the PPC series. Mixtures were prepared with w/b ratios of 0.25, 0.28, 0.30, 0.33, and 0.35. The porosity-based mix design was based on the volume method, which centers on precisely calculating the volume relationship between cement paste and aggregates to control the porosity. The procedure involved the following steps [26]: (i) the porosity was set based on the intended application and required permeability performance; (ii) the volume fraction of the aggregates within the concrete was calculated according to their size and gradation; (iii) the volume of the cement paste (comprising cement and water) was determined as the volume required to fill the voids between the aggregates, ensuring the final porosity met the design target. and (iv) The specific masses of cement and water were calculated based on the paste volume and the selected w/b ratio, which significantly affects the mechanical performance. This method allows for a balanced consideration of both strength and permeability. Table 5 details the mix proportions for the PPC series, designed to identify the optimal w/b ratio. All mixes incorporate a constant 10% FA replacement of cement and a water reducer dosage of 0.9%. Specimens are labeled as S-X-Y, where X denotes the porosity (%) and Y the w/b ratio (e.g., S-15-0.28 corresponds to 15% porosity and a w/b of 0.28).

Table 5.

Mix proportion of PPC to determine the optimal w/b ratio.

3.3. Experimental Methods

The PPC mixtures were prepared using a rotating drum mixer. The procedure began by mixing the coarse aggregates with approximately 10% of the total mixing water for about 30 s. The cement was incorporated into the mixture, after which the remaining water was incrementally introduced to achieve a homogeneous blend. Superplasticizer was then added, followed by a final 5 min mixing period. For the PCNS mixture, the procedure was adapted: NS was first dispersed in a portion of the mixing water using a mortar mixer for approximately 5 min. This NS suspension was gradually fed into the concrete mixer prior to the addition of the remaining water. Notably, despite a higher SP dosage in the PCNS compared to the PPC, the resulting consistency differed, with the PCNS mix appearing less workable and lacking surface gloss. The SP content was not raised beyond the specified range of 0.5% to 2.5%. Specimens were cast in the following two forms: 100 mm cubes for compression tests and cylinders (Ø100 mm × 100 mm) for permeability evaluation. The cubes were demolded after 24 h, then labeled and weighed. All samples were subsequently cured in a controlled environment at 23 ± 2 °C until the designated test ages. Figure 2 illustrates the cube specimen preparation sequence.

Figure 2.

Specimen preparation.

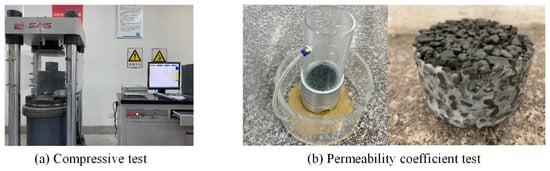

The compressive strength of PPC and PCNS specimens was determined as per GB/T 50081-2019 [28] using a Model SYE-2000BS hydraulic universal testing machine produced by Guangzhou Boshun Experimental Instruments Co., Ltd., Guangzhou, China. The loading rate was 0.5 mm/min. Prior to testing, specimen ends were capped to ensure uniform load distribution. Sulfur capping is more appropriate for permeable concrete and therefore is employed herein. This method was employed for all specimens in the present study to ensure consistent and reliable results. The compressive strength test setup is illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Tests of PPC and PCNS: (a) compressive test; and (b) permeability coefficient test.

The permeability of PPC and PCNS is expressed as the permeability coefficient in centimeters per second (cm/s). Due to its highly interconnected pore structure, the standard permeability test methods for conventional dense concrete are not applicable. Therefore, this study adopted the testing procedure specified in CJJ/T 135-2009 [29]. Following 28 days of curing, the cylindrical specimens were circumferentially sealed with petroleum jelly to inhibit lateral water leakage. After placing the sealed specimen into the permeameter to confirm seal integrity, the entire assembly was submerged in a water tank. Water was then slowly supplied from the top, establishing a constant head of 20 cm. The test commenced once a steady outflow was observed at the overflow outlet. The volume of water (Q) discharged over a 5 min interval was collected and measured using a graduated cylinder; this measurement was triplicated to obtain an average. The water head (H) was measured with 1.0 mm accuracy, and the water temperature (T) in the overflow tank was recorded via a thermometer with a precision of 0.5 °C. The permeability coefficient was subsequently determined using Equation (1), based on the average results from three replicate specimens.

where = permeability coefficient, (cm3) represents the amount of water infiltrated in t seconds, (cm) = specimen height, and (cm2) = upper surface area. In Equation (1), KT represents the permeability coefficient corrected to the standard temperature of 20 °C. The raw flow data were adjusted for water viscosity variation with temperature according to the procedure specified in CJJ/T 135-2009 [29]. Briefly, the measured discharge Q at the test temperature T was converted to its equivalent value at 20 °C before calculating KT. This ensures that the reported coefficients are comparable across different testing conditions.

The effective (open) porosity was measured at 28 days, following a standardized volumetric procedure. This property represents the percentage of the total volume that consists of interconnected pores capable of holding water. The tests involved oven-drying the specimen at 110 °C before achieving a constant mass, followed by cooling to room temperature. The total volume (VT) of the dried specimen was determined through dimensional measurement. The specimen was then fully submerged in water for 24 h. After removal, the water volume replaced by solid matrix (VC) was measured by refilling the container to its initial water level. The mass of the added water, equivalent to its volume (assuming a density of 1 g/cm3), was recorded. The porosity (P) was calculated using Equation (2):

3.4. Determination of Optimal W/B Ratio

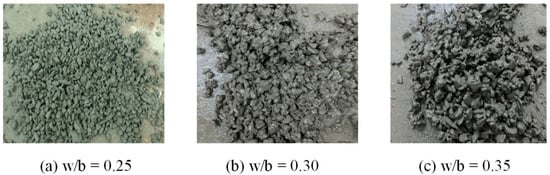

A preliminary assessment of mixture workability was conducted through trial mixing and cement paste jump table tests to identify a feasible w/b range for further quantitative evaluation. The final determination of the optimal w/b ratio, however, was based on the measured compressive strength and permeability coefficient, as presented subsequently. To ensure that the permeable concrete with different w/b ratios experience good and consistent workability, this paper conducted trial mixing tests and cement paste jump table tests. The mixture with the best working condition was determined, and its cement paste flowability was measured. Subsequently, by adding a water-reducing agent, the flowability of cement paste with other w/b ratios was adjusted to be close to the flowability under the best condition, thereby estimating the approximate content of water-reducing agent for permeable concrete with different w/b ratios. Three w/b ratios (0.25, 0.30, and 0.35) were investigated in the trial mixing test, with a fixed porosity of 20%. Figure 4 shows the observed mixture states for different w/b ratios, where the dispersion occurred when w/b = 0.25 and 0.30 and diminished when w/b increases to 0.35 with excellent adhesion.

Figure 4.

Mixture states for different w/b ratios of (a) 0.25; (b) 0.30; and (c) 0.35.

The workability with different w/b ratios was roughly evaluated through manual handling. When w/b = 0.25, the cement paste exhibited poor cohesion, causing the mixture to crumble when hand-squeezed. When w/b = 0.30, the cohesiveness of the paste improved significantly, and the mixture remained intact after squeezing. When w/b = 0.35, although the mixture also remained consolidated after squeezing, the fluidity increased while its cohesion relatively weakened, resulting in noticeable paste bleeding. To provide a quantitative indicator of paste workability, the flow diameter of the cement paste was measured using a flow table for the three w/b ratios (0.25, 0.30, and 0.35). By adjusting the superplasticizer dosage, comparable consistencies were achieved, with measured flow diameters of approximately 169 mm, 180 mm, and 168 mm for w/b ratios of 0.25, 0.30, and 0.35, respectively. The paste with w/b = 0.30 exhibited a balanced fluidity suitable for uniformly coating aggregates. Based on these observations, the mixture with w/b = 0.30 demonstrated optimal cohesion and a desirable metallic sheen (indicating a uniform dense paste coating) on the aggregate surfaces, indicating a clearly superior state compared to the other two ratios. Therefore, the mixture performance at this w/b ratio of 0.30 is recommended as a reference for proportioning.

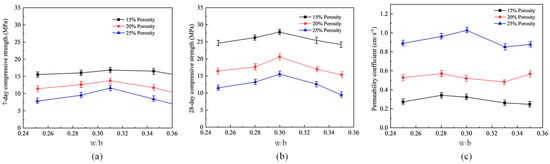

To identify the optimal w/b ratio, the synergistic effect of w/b ratio and the incorporated 10% FA on the strength and permeability was evaluated across various porosity levels. As depicted in Figure 5, both 7-day and 28-day compressive strengths exhibit a consistent trend regardless of porosity as they initially increase with w/b ratio (peak at 0.30) and subsequently decrease. Specifically, Peak strengths at w/b = 0.30 were 17.8 MPa (7-day) and 28.4 MPa (28-day) for 15% porosity, 14.5 MPa and 21.3 MPa for 20% porosity, and 12.1 MPa and 16.2 MPa for 25% porosity. This trend is governed by the synergistic interplay between w/b ratio and FA reactivity. At a low w/b ratio (0.25), the insufficient effective water limits the complete hydration of cement and the pozzolanic reaction of FA, resulting in a weaker matrix. Notably, specimens with w/b = 0.30 provide optimal moisture for both cement hydration and FA activation, maximizing paste density and strength. However, at higher ratios (0.35), despite full cement hydration, excess water increases capillary porosity in the paste, while the contribution of FA cannot compensate for this inherent weakening, leading to reduced strength.

Figure 5.

Effect of w/b ratio on (a) 7d strength; (b) 28d strength; and (c) permeability coefficient.

Figure 5c illustrates the influence of w/b ratio on the permeability coefficient at various porosities. Unlike the trend observed for compressive strength, the impact of w/b ratio on permeability has been found to be highly dependent on porosity. Specifically, the peak permeability coefficient was observed when w/b = 0.28 for 15% porosity, 0.30 for 20% porosity, and 0.35 for 25% porosity. The w/b ratio yielding the maximum permeability coefficient varied with porosity (0.28 for 15%, 0.30 for 20%, 0.35 for 25%). This variation is mainly attributed to the interplay between the w/b ratio and the FA content. Its presence modifies the rheology and water demand of the paste, thereby altering the balance between paste fluidity and pore connectivity, which dictates the permeability trend for each porosity level. In the case of greater paste fluidities (typically with higher w/b ratios), the mixture tends to migrate downwards under gravity, potentially occluding pores at the bottom and disrupting the connectivity of the void network, which in turn reduces the permeability. Conversely, a paste with lower fluidity adheres more effectively to the aggregate surfaces. This coating action minimizes blockage of the pore throats, preserving a more continuous and interconnected void structure and resulting in a higher permeability coefficient. The compressive strength and permeability results presented in Figure 5 provide the definitive criteria for selecting the optimal w/b ratio. As shown in Figure 5a,b, the compressive strength at both 7 and 28 days peaked consistently at w/b = 0.30 for all three target porosities (15%, 20%, and 25%). While the permeability coefficient (Figure 5c) reached its maximum at slightly different w/b ratios depending on porosity, the values achieved at w/b = 0.30 were statistically equivalent to these peak values in all cases. Therefore, w/b = 0.30 is identified as the optimal ratio for this study, as it reliably delivers the highest mechanical strength while maintaining permeability performance that is not significantly different from the maximum achievable within the tested range. It is noted that this optimal w/b ratio of 0.30 was determined for the specific material system (with 10% FA) and laboratory compaction method used in this study.

3.5. Mix Proportions of PCNS

After determining the w/b ratio of 0.3, the mix proportions of PCNS were presented to evaluate the combined effects of porosity and nano-silica (NS). In the PCNS experiment, the designed target porosity values were 15%, 20%, and 25% with a water-cement ratio of 0.30. NS was added externally at incorporation rates of 0%, 0.5%, 1.0%, 1.5%, 2.0%, and 2.5% by weight of cement. For all mixtures, the superplasticizer dosage was held constant at 0.8% by weight of cement. Table 6 lists the eighteen PCNS mixtures prepared in this study. Each mixture is labeled as “NS-X-Y”, where X denotes the design porosity (in %) and Y indicates the NS content (in %). For each mixture, a set of three-cylinder specimens was cast. After 28 days of standard water curing, their compressive strength and permeability were determined. The testing methods employed for the PCNS series were in accordance with those used for the control (PPC) series, as detailed in Section 3.3.

Table 6.

Mix proportions of PCNS with the optimal w/b ratio of 0.3.

4. Results and Discussion

Table 7 presents the compressive strength and permeability coefficients of PCNS with various nano-silica dosages at the three target porosities, where the results were presented in terms of the average value and the standard deviation. It should be noted that the performance reported herein reflects the combined system of NS within an FA-modified cementitious matrix. Consequently, the trends observed in strength and permeability are interpreted as the incremental influence of NS dosage and porosity within this stabilized system.

Table 7.

Test results of PCNS.

Alongside the target porosity, the table also includes the measured open porosity for each mixture, determined at 28 days using the volumetric method described in Section 3.3. This allows for a direct comparison between the designed and actual pore volumes, and is crucial for distinguishing the effects of NS on pore structure from those on total porosity. It can be observed that the NS additive exhibited a significant influence on the performance of PCNS regardless of porosity. In the subsequent sections, the impact of NS on the behavior of PCNS will be discussed in detail to determine the optimal content of NS.

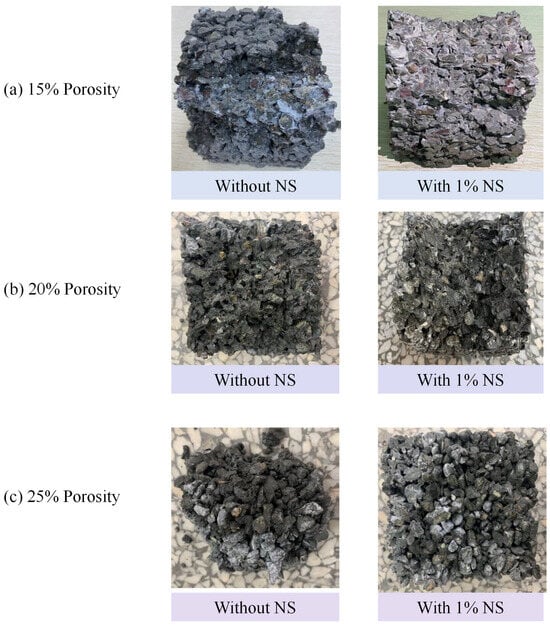

4.1. Effect of NS Content on the Failure Mode

Figure 6 illustrates the impact of NS content on the failure modes considering different porosities. In this study, microstructural verification (SEM, etc.) of this mechanism was not performed, but the inference was made observationally. The failure modes of the tested specimens were analyzed through visual inspection of the fracture surfaces. To provide a systematic assessment, the observations were categorized based on the dominant feature covering more than approximately 70% of the fracture area. The trends described below were consistent across all replicates within each mixture group. The failure mode of permeable concrete is predominantly governed by its target porosity. For specimens with 15% target porosity and without NS, the fracture surface was dominated by fractured aggregates, which constituted the majority of the visible area. This indicates that the failure was primarily controlled by the strength of the aggregate particles at this low-porosity and high-paste-volume condition. In contrast, for specimens with 25% target porosity and without NS, the fracture surface predominantly exhibited debonding at the interfacial transition zone (ITZ) and cracking through the thin paste bridges, with very few fractured aggregates. This confirms that the cementitious matrix constitutes the weakest link in high-porosity systems.

Figure 6.

Effect of NS on failure mode of permeable concrete for porosity of (a) 15%; (b) 20%; and (c) 25%.

The incorporation of NS systematically altered these failure patterns. With the addition of NS, particularly in medium- and high-porosity specimens, the proportion of aggregate fracture on the failure surface increased significantly. This indicates a shift in the weak link of the system, transitioning partially from the cementitious matrix to the inherent strength of the aggregates. Comparative analysis of failure surfaces without NS and with 1% NS across different porosities reveals that at 15% porosity, the increase in aggregate fracture with NS addition was slight; at 20% porosity, aggregate fracture became markedly more frequent; and at 25% porosity, the failure mode varied from “bulk spalling” (cement paste failure) without NS to a predominantly “fragmented” pattern featuring extensive aggregate fracture with NS.

This transition in failure mechanism stems from the synergistic effect of NS and porosity on the weak points. Porosity determines the initial weak point of the system: at low porosity, the thick paste layer results in stress concentration at aggregate contact points dominating failure. Nevertheless, at high porosity, the thin paste layer becomes the mechanical bottleneck. In fact, NS modifies the relative strength of this weak point by strengthening the matrix strength and the interfacial bonding strength. The pozzolanic reaction and micro-filling effect of NS significantly improve the density and properties of the matrix and the ITZ. Thus, in high-porosity specimens where the cementitious system is originally the weak link, the reinforcing effect of NS is particularly pronounced. This enhancement makes the aggregate strength the new limiting factor, causing aggregates to fracture before the strengthened paste fails, eventually altering the failure path and mode.

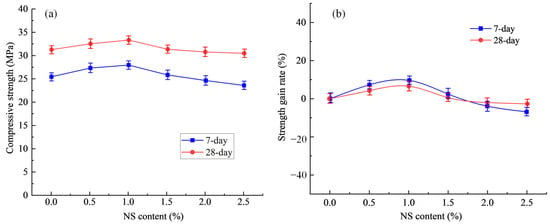

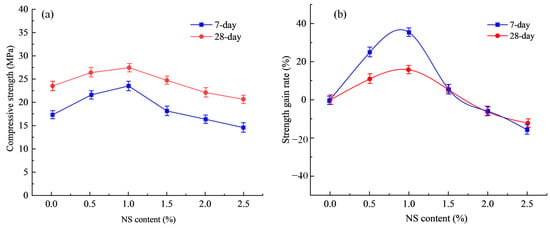

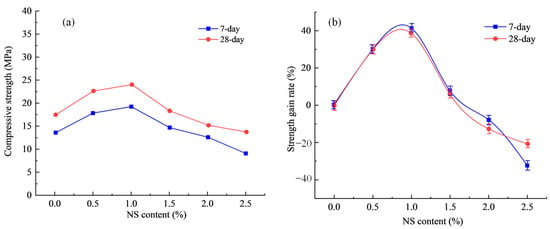

4.2. Effect of NS Content on the Compressive Strength

Figure 7, Figure 8 and Figure 9 present the effect of NS content on the 7d and 28d compressive strength and the corresponding increase rate of permeable concrete subjected to 15%, 20%, and 25% porosity. It can be observed that the incorporation of NS significantly enhances the strength across all porosity levels; however, the efficiency of this enhancement follows a systematic pattern dependent on both the NS content and the target porosity. For any given porosity, the compressive strength initially increases with the NS content, reaching a peak at 1.0% NS content before declining. Furthermore, the improvement in early-age strength (7 days) is generally more pronounced than that in later-age strength (28 days).

Figure 7.

Influence of NS on compressive strength for porosity of 15%. (a) absolute strength; and (b) gain rate.

Figure 8.

Influence of NS on compressive strength for porosity of 20%. (a) absolute strength; and (b) gain rate.

Figure 9.

Influence of NS on compressive strength for porosity of 25%. (a) absolute strength; and (b) gain rate.

Taking 28-day compressive strength as an example, the reference strengths (without NS) for specimens with 15%, 20%, and 25% porosity were 31.3 MPa, 23.6 MPa, and 17.4 MPa, respectively. With the addition of 1% NS, these strengths increased to 33.3 MPa, 27.4 MPa, and 24.1 MPa. The corresponding strength increase rates were 6.4%, 16.1%, and 38.5%, respectively. This confirms that the NS effectiveness in enhancing the strength increases dramatically with higher target porosity. In terms of absolute strength gain, the 25% porosity specimen exhibited an increase of 6.7 MPa, substantially greater than the 2.0 MPa gain observed in the 15% porosity specimen.

The strengthening mechanism of NS primarily stems from its pozzolanic reactivity and micro-filling effect, which synergistically contribute to a denser cement paste microstructure and a reinforced interfacial transition zone. Porosity plays a leveraging role in this process. In low-porosity systems, the abundant cement paste already possesses high intrinsic strength, and failure is predominantly controlled by aggregate strength, thereby limiting the relative impact of NS. In contrast, in high-porosity systems, the scarce cement pastes and thin bonding layers constitute the mechanical weakest link of the composite. Here, the strengthening effect of NS on this vulnerable phase is greatly amplified, enabling more effective load transfer to the aggregates and resulting in a substantial improvement in overall compressive strength. This interplay demonstrates a synergistic short-board reinforcement mechanism.

The dramatic increase in the efficacy of NS with higher porosity (6.4% strength gain at 15% porosity vs. 38.5% at 25% porosity) can be logically explained by the shift in failure mode documented in Section 4.1. At 15% porosity, the failure is already due to the aggregate, then the strength is limited by the aggregate, and further strengthening of the NS matrix is ineffective. Conversely, at 25% porosity, the sparse paste and thin ITZ form the mechanically limiting phase. NS reinforcement directly targets this weakest component, resulting in a pronounced strength increase and a shift in the failure path toward the aggregates, which then become the new governing factor.

Conclusively, the test results identify 1% as the optimal NS content with respect to strength. At this dosage, permeable concrete across all three porosity levels reached their peak strengths regardless of curing age. Beyond 1%, the enhancement effect diminishes, and strength may even decrease, attributable to increased risks of NS agglomeration and potential adverse effects on the hydration environment due to excessive specific surface area.

4.3. Effect of NS Content on the Permeability Coefficient

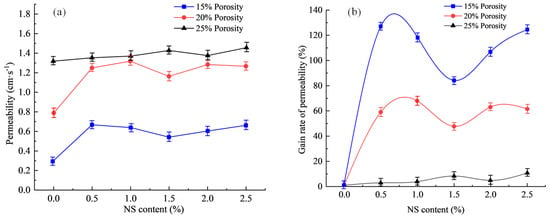

Figure 10 illustrates the impact of NS on the permeability coefficient and its increase rate, considering different porosities. As expected, the incorporation of NS exerts a beneficial effect on the permeability. This improvement can be primarily attributed to the optimized workability of the fresh paste, which enables a more uniform coating of aggregates and reduces the tendency for the paste to flow down and block the interconnected pores at the bottom. A significant jump in the permeability coefficient is observed once the NS content reaches 0.5%. For specimens with 15%, 20%, and 25% porosity, the permeability coefficient increased from the reference values (without NS) of 0.291, 0.784, and 1.313 to 0.661, 1.245, and 1.347 cm/s, respectively. The corresponding permeability increase rates are 127.1%, 58.8%, and 2.6%. Notably, when the NS content exceeds 0.5%, the permeability coefficient has reached a plateau, showing no significant further increase with higher dosages.

Figure 10.

Influence of NS on (a) permeability coefficient; and (b) gain rate.

The mechanism by which NS improves the permeability lies in its ability to enhance the cohesiveness and coating capability of the cement paste. This optimizes the vertical distribution of the paste, thereby preserving the continuity and interconnectivity of pore structures. The combined effect of NS and porosity exhibits a characteristic of diminishing marginal returns. In low-porosity (15%) specimens, the high paste content leads to narrow pore channels that are prone to blockage. Consequently, the improvement in paste fluidity afforded by NS makes a substantial contribution to maintaining pore connectivity, leading to dramatic variations in the permeability coefficient. Conversely, in high-porosity (25%) specimens, the inherent abundance of large, interconnected pores presents a low initial risk of paste blockage. Thus, while the addition of NS remains beneficial, the relative improvement in permeability is markedly limited.

Analysis of the measured open porosity shown in Table 7 reveals that the addition of NS did not systematically alter the total pore volume. The measured values for each target porosity group (e.g., ~14–16% for the 15% group, ~18–22% for the 20% group, ~23–26% for the 25% group) cluster around their respective target values, with deviations falling within the typical range of variability for this permeable concrete design method. This confirms that the significant enhancements in the permeability coefficient (K) are primarily attributable to improvements in pore connectivity and paste distribution, which stem from better aggregate coating, rather than to an increase in total porosity.

From the perspective of maximizing permeability performance while considering cost-effectiveness, an NS content of 0.5% is sufficient to achieve significant optimization of the permeability coefficient. Further increasing the NS content to 1%, while optimal for the compressive strength, provides no substantial additional benefit for permeability. Therefore, for practical applications where enhancing permeability is the primary objective, a dosage of 0.5% NS is recommended. If seeking an optimal balance between comprehensive properties (strength and permeability), a content of 1% NS is advised. Notably, the reported enhancements in strength and permeability of permeable concrete result from the combined system of NS within a cementitious matrix containing a fixed 10% FA replacement. FA may enhance the overall system performance through its own physical filling and pozzolanic properties, potentially creating a synergistic effect with the nano-filling and high pozzolanic activity of NS to produce a more refined microstructure.

4.4. Porosity Versus Permeability Relationship of 1% NS Modified Permeable Concrete

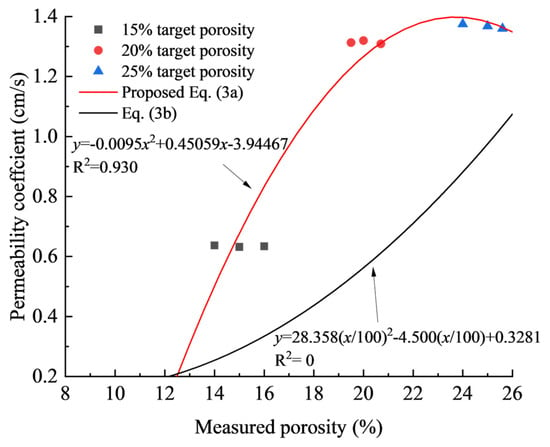

This section aims to establish a robust quantitative porosity-permeability relationship based on the measured open porosity for permeable concrete modified with 1% NS. The collective results summarized in Figure 11 reveal a strong positive correlation between the measured porosity and the permeability coefficient (K). This trend is physically explained by the fact that higher porosity not only increases the total void volume but also enhances the connectivity and effective size of the pore channels, drastically reducing hydraulic resistance.

Figure 11.

A comparison between experimental data and model predictions for the porosity versus permeability coefficient, using the proposed Equation (3a) and Equation (3b) from Ref. [30].

Cui et al. [30] and Liu et al. [26] carried out an experimental study to evaluate the relation between porosity and permeability of permeable concrete without any additives. The results demonstrated that the porosity and permeability coefficient are positively correlated: The permeability coefficient increases when the porosity increases, and the rate increases. This section aims to establish a robust quantitative porosity versus permeability relationship of 1% NS modified permeable concrete. The collective results summarized in Figure 11 reveal a strong positive porosity (P) versus permeability (K) correlation. To derive a unified predictive model for the permeability of 1% NS-modified permeable concrete. The experimental data across different w/b ratios are excellently fitted by the following second-order polynomial equation:

To visually and quantitatively compare the predictive capability of the proposed model for NS-modified concrete with that of existing models for conventional concrete, the fitted curve of Equation (3a) and the curve representing the model by Cui et al. [30] for normal permeable concrete [Equation (3b)] are compared with the experimental data for mixes containing 1% NS. It is found that the proposed Equation (3a) exhibits an excellent fit to the test data for 1% NS-modified permeable concrete, with a coefficient of determination (R2) of 0.93 and a low root-mean-square error of 0.08 cm/s. In contrast, the model by Cui et al. [30] shows a systematic deviation from the experimental data, significantly underestimating the permeability at porosities ranging from 15% to 25%. This confirms that the porosity–permeability relationship is fundamentally altered by the inclusion of 1% NS, primarily due to its effect on paste rheology and pore connectivity as discussed earlier. Therefore, the model by Cui et al. [30] is not suitable for predicting the permeability of NS-modified permeable concrete, justifying the need for and the superiority of the proposed Equation (3a) for 1% NS-modified permeable concrete.

From a practical perspective, the proposed equation enables the precise determination of the required target porosity to achieve a specific permeability performance. For instance, if a project specification mandates K of 1.0 cm/s, the model can be solved to find the necessary porosity:

Solving this equation yields a target porosity of approximately 17.2%. This value can then be directly used as the key input parameter in the volume-based mix proportion method to calculate the exact values of aggregate, cement, and water in designing permeable concrete structures. This prediction is also consistent with the measured data trends. As shown in Table 7, PCNS mixtures with a measured porosity (Pm) close to 17% (e.g., NS-20 mixtures with Pm ≈ 18–22%) exhibit permeability coefficients ranging from approximately 1.16 to 1.35 cm/s. Therefore, to achieve a slightly lower K of 1.0 cm/s, a design porosity slightly below this range as predicted by the model is logically consistent. Therefore, it is reasonably expected that the model can provide a reliable guide for selecting design porosity based on a target permeability. It is noted that the proposed porosity-permeability relationship is specifically validated for 1% NS content and within the investigated porosity range of 15–25%.

4.5. Limitations and Future Work

While this study systematically investigates the influence of target porosity and NS on the macroscopic properties of permeable concrete, it is necessary to acknowledge there are two main limitations. First, the evaluation of mechanical properties primarily focused on compressive strength. For permeable concrete used in pavement applications, however, key parameters such as flexural strength, tensile strength, and fracture toughness are equally critical for assessing crack resistance and long-term durability. More experiments need to be conducted to offer a comprehensive understanding of PCNS. Second, the experimental findings are predominantly with macro-scale performance tests. To gain deeper insight into the reinforcement of NS, such as its specific effects on hydration products, microstructural morphology, and the characteristics of the ITZ, future work is currently underway to incorporate advanced micro-scale techniques, such as scanning electron microscopy (SEM), X-ray diffraction (XRD), etc. Despite these limitations, the findings offer clear practical value and provide direct theoretical and practical guidance for future work regarding targeted design of permeable concrete:

- (1)

- In scenarios such as sidewalks, parking lots, and plazas where high permeability is prioritized and loading demands are moderate, incorporating 1% NS proves to be an effective strategy as it significantly enhances the compressive strength of high-porosity mixtures without compromising (sometimes even improving) their permeability.

- (2)

- For high-strength applications of permeable concrete subject to higher loads, enhancing aggregate properties is paramount. For instance, using high-strength aggregates (e.g., steel slag [26]) as a volumetric replacement for ordinary crushed stone may be an effective method for boosting the strength of low-porosity (e.g., 15%) permeable concrete.

- (3)

- This research identifies a w/b ratio of 0.30 as optimal. In future studies, designers can first determine the porosity based on required permeability (e.g., ≥0.5 cm/s) and strength (e.g., ≥C20) thresholds. NS can then be employed to specifically compensate for the associated strength deficit, enabling the precise design and optimization of PCNS.

- (4)

- Although FA is incorporated into the mix design, its individual contribution and synergistic interactions with nano-silica (NS) on the performance and failure mechanisms of the resulting permeable concrete warrant further investigation.

5. Conclusions

This paper experimentally evaluated the strength and permeability of NS-modified permeable concrete (PCNS) considering various porosities. Based on the results obtained, the main conclusions can be drawn as follows.

- (1)

- The incorporation of NS in permeable concrete alters the failure mode by shifting the weak link. For high-porosity (25%) concrete, the failure mode transitions from cohesive failure at the cement paste to aggregate fracture. This shift is due to the NS-induced enhancement of the cement paste matrix and the ITZ.

- (2)

- A 1% NS dosage optimally enhances the compressive strength across all porosity levels, with the improvement efficacy increasing with porosity. The 28-day strength increased by 6.4%, 16.1%, and 38.5% for porosities of 15%, 20%, and 25%, respectively, as the NS additive reinforces weak high-porosity zones via pozzolanic and filling effects.

- (3)

- The addition of NS significantly improves the permeability coefficient, primarily by enhancing the cohesiveness and coating capability of the fresh paste. A dosage of 0.5% NS causes a substantial improvement in the permeability coefficient by 127.1%, 58.8%, and 2.6% for 15%, 20%, and 25% porosity mixes, respectively.

- (4)

- An empirical expression between porosity and the permeability coefficient was developed for 1% NS-modified permeable concrete. Compared to existing formulas proposed for permeable concrete without NS, the proposed model can be more effectively used to capture the porosity versus permeability relationship. The practicability of the model lies in its ability to determine the required porosity (e.g., p ≈ 17% for K = 1.0 cm/s) to meet specific hydrological requirements, thereby facilitating a mix design of PCNS in practical applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.F. and M.S.; Methodology, L.J.; Software, L.J. and M.S.; Validation, L.J. and D.Y.; Formal analysis, M.Y. and D.Y.; Investigation, M.Y.; Data curation, M.Y., D.Y. and M.S.; Writing—original draft, J.F.; Writing—review & editing, Y.W.; Visualization, Y.W.; Supervision, M.S. and Y.W.; Project administration, J.F. and Y.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Science and Technology Research Project of Jiangxi Provincial Department of Education (No. GJJ2404914, No. GJJ2404907), the Scientific Research Foundation of Jiangxi Polytechnic University (No. JZBK25-2-5), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 52308165). Yan-Jie Wang thanks for the financial support from the China Scholarship Council (No. 202208130081) for his visit to the University of Western Australia.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Su, X.; Shao, W.; Liu, J.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, J.; Yang, Z.; Wang, N. How does sponge city construction affect carbon emission from integrated urban drainage system? J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 363, 132595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Ren, J.; Xu, J.; Zheng, T.; Cheng, W.; Qiao, J.; Huang, J.; Li, G. Prediction of life cycle carbon emissions of sponge city projects: A case study in Shanghai, China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoro, K.O.; Daramola, M.O. CO2 emission sources, greenhouse gases, and the global warming effect. In Advances in Carbon Capture; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2020; pp. 3–28. [Google Scholar]

- Filonchyk, M.; Peterson, M.P.; Zhang, L.; Hurynovich, V.; He, Y. Greenhouse gases emissions and global climate change: Examining the influence of CO2, CH4, and N2O. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 935, 173359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Versini, P.-A.; Kotelnikova, N.; Poulhes, A.; Tchiguirinskaia, I.; Schertzer, D.; Leurent, F. A distributed modelling approach to assess the use of Blue and Green Infrastructures to fulfil stormwater management requirements. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2018, 173, 60–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Jiang, G. Experimental study on properties of permeable concrete pavement materials. Cem. Concr. Res. 2003, 33, 381–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrappa, A.K.; Biligiri, K.P. Permeable concrete as a sustainable pavement material–Research findings and future prospects: A state-of-the-art review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 111, 262–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Wu, H.; Shu, X.; Burdette, E.G. Laboratory evaluation of permeability and strength of polymer-modified permeable concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2010, 24, 818–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chindaprasirt, P.; Hatanaka, S.; Chareerat, T.; Mishima, N.; Yuasa, Y. Cement paste characteristics and porous concrete properties. Constr. Build. Mater. 2008, 22, 894–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, R.; Wille, K. Linking pore system characteristics to the compressive behavior of permeable concrete. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2016, 70, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putman, B.J.; Neptune, A.I. Comparison of test specimen preparation techniques for pervious concrete pavements. Constr. Build. Mater. 2011, 25, 3480–3485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Liu, J.; Li, H.; Ren, Q. Performance and ITZ of permeable concrete modified by vinyl acetate and ethylene copolymer dispersible powder. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 235, 117532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wang, G.; Dong, Q.; Zhao, X.; Wang, Y. Microscopic characterizations of permeable concrete using recycled Steel Slag Aggregate. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 254, 120149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Chen, X.; Dong, Q.; Yuan, J.; Hong, Q. Mechanical performance study of permeable concrete using steel slag aggregate through laboratory tests and numerical simulation. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 262, 121208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, T.; Ma, W.; Yang, Y.; Yu, J.; Liu, J.; Jiang, C.; Gu, C. Interface reinforcement and a new characterization method for pore structure of permeable concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 267, 121052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, B.S.; Liew, M.S.; Alaloul, W.S.; Khed, V.C.; Hoong, C.Y.; Adamu, M. Properties of nano-silica modified permeable concrete. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2018, 8, 409–422. [Google Scholar]

- AlShareedah, O.; Nassiri, S. Pervious concrete mixture optimization, physical, and mechanical properties and pavement design: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 288, 125095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, J.D.; Kosteski, L.E.; Marangon, E.; Vantadori, S. Strength analysis of nano-silica modified pervious concrete: A promising cement-based composite–Experimental and numerical investigation. Compos. Struct. 2025, 372, 119547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirgir, B.; Hassani, A.; Khodadadi, A. Experimental study on permeability and mechanical properties of nanomodified porous concrete. Transp. Res. Rec. 2011, 2240, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khankhaje, E.; Kim, T.; Jang, H.; Kim, C.-S.; Kim, J.; Rafieizonooz, M. Properties of pervious concrete incorporating fly ash as partial replacement of cement: A review. Dev. Built Environ. 2023, 14, 100130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, B.S.; Nuruddin, M.F.; Dayalan, Y. High permeable concrete incorporating pozzolanic materials-An experimental investigation. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE Business Engineering and Industrial Applications Colloquium (BEIAC), Langkawi, Malaysia, 7–9 April 2013; pp. 657–661. [Google Scholar]

- Alighardashi, A.; Mehrani, M.J.; Ramezanianpour, A.M. Permeable concrete reactive barrier containing nano-silica for nitrate removal from contaminated water. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 29481–29492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S.A.; Toghroli, A. Effect of mixing Nano-silica and Perlite with permeable concrete for nitrate removal from the contaminated water. Adv. Concr. Constr. 2021, 11, 531–544. [Google Scholar]

- Debnath, B.; Sarkar, P.P. Application of nano SiO2 in permeable concrete pavement using waste bricks as coarse aggregate. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2022, 47, 12649–12669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahul, R.; Kumar, M.S.R. Influence of nano-silica and shredded plastics in permeable concrete. Matéria 2024, 29, e20240127. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, F.; Li, Z.; Liu, B.; Yu, Z.; Li, Z.; Zhu, M.; Wang, Y.; Ding, X. Experimental and Numerical Investigations on the Influences of Target Porosity and w/b Ratio on Strength and Permeability of Permeable concrete. Materials 2025, 18, 3951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Sun, M.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, L. Evaluation of High-Performance Permeable concrete Mixed with Nano-Silica and Carbon Fiber. Buildings 2025, 15, 2407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 50081-2019; Standard for Test Methods of Concrete Physical and Mechanica Properties. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2017.

- CJJ/T 135-2009; Technical Specification for Pervious Cement Concrete Pavement. China 802 Construction Industry Press: Beijing, China, 2009. (In Chinese)

- Cui, X.; Zhang, J.; Huang, D.; Liu, Z.; Hou, F.; Cui, S.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Z. Experimental study on the relationship between permeability and strength of pervious concrete. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. ASCE 2017, 29, 04017217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.