1. Introduction

The management of Architecture, Engineering and Construction (AEC) projects is not merely a technical endeavor but a socially embedded process that must reconcile a wide range of stakeholder interests to achieve sustainable and positive societal impacts. Modern projects inevitably operate with a high degree of participation from affected parties and are increasingly leveraged as instruments to spur civil society development. Consequently, understanding and optimizing the collaborative dynamics among diverse stakeholders, including owners, designers, contractors, suppliers, and community representatives, is critical for enhancing project outcomes and their broader social value [

1].

Despite this recognized importance, the inherent complexity of construction projects, characterized by numerous participants, extended lifecycles, and multi-phase processes [

2], poses significant challenges to effective collaboration. Inefficiencies in stakeholder interaction and information exchange often lead to project delays, cost overruns, and quality issues, ultimately diminishing the potential social benefits of construction initiatives [

3].

In recent years, Social Network Analysis (SNA) has emerged as a powerful methodological tool for examining the relational fabric of collaboration within AEC projects [

4]. By modeling stakeholders as nodes and their interactions as links, SNA provides quantitative insights into network structure, key influencers, and information flow [

5]. However, a synthesis of the literature reveals that most existing SNA studies offer static or cross-sectional views, failing to capture the temporal evolution and phase-specific dynamics of collaboration networks [

6], thus limiting their utility in understanding how social structures develop and impact project-based social development. Furthermore, many existing studies lack integration with project work structures, such as the Work Breakdown Structure (WBS), which is crucial for contextualizing collaboration within specific project tasks and phases.

The digital transformation ushered in by Building Information Modeling (BIM) has further reshaped collaboration patterns [

7]. As an integrated platform, BIM streamlines project delivery, provides clarity through visualization, and empowers data-driven decision-making [

8]. It reconfigures traditional information exchange networks by introducing new roles, altering communication pathways, and enabling more transparent workflows [

9]. Despite its recognized potential, empirical research that quantitatively investigates how BIM influences these collaborative networks across different project stages, and thereby affects their social dimensions, remains surprisingly scarce [

6]. Most studies remain at a conceptual or anecdotal level, lacking a methodological framework to systematically trace and measure BIM-induced network changes. With the advancement of BIM technology, models and data are integrated across different stages, laying the foundation for implementing building lifecycle management. By integrating design, construction, and operational data, BIM enhances communication, visualization, and collaboration among stakeholders [

10]. To address these gaps, this study proposes an integrated analytical framework that combines SNA with Cognitive Social Structure (CSS) to trace and quantify the evolution of collaborative relationships across project phases. By incorporating a WBS for task delineation and relationship quantification, the framework captures both the structural and temporal dimensions of collaboration, directly linking project management practices to stakeholder engagement dynamics. A network model is developed to specifically assess BIM-induced changes in information exchange networks. A case study is presented to demonstrate the framework’s application, providing quantitative and qualitative results that validate its utility.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 reviews the theoretical foundations of SNA in AEC research.

Section 3 details the research methodology, including data collection, processing, and the specific steps for network construction and analysis.

Section 4 presents the proposed framework for analyzing collaborative relationships.

Section 5 develops a network model to investigate the impact of BIM on information exchange networks.

Section 6 validates the framework through a case study. Finally,

Section 7 concludes the study.

2. Social Network Analysis (SNA) in Research of Information Exchange Network

SNA is a methodological approach grounded in graph theory, used to model and analyze relationships among interacting entities. In the context of construction projects, SNA represents stakeholders as nodes and their interactions as edges, providing a structural and quantitative means to examine collaboration patterns, information flow, and influence within project networks [

11]. By computing metrics such as density, centrality, and betweenness, SNA offers insights into the overall network configuration, key actors, and the efficiency of communication pathways [

12].

Unlike traditional analytical methods that often focus on individual attributes, SNA emphasizes the relational aspects among entities, thereby bridging micro-level interactions and macro-level network structures. This dual perspective allows researchers to explore how individual behaviors influence the network and, conversely, how network structures constrain or enable individual actions.

SNA can be broadly categorized into two types: single-point (static) and longitudinal (dynamic) SNA. Single-point SNA captures network characteristics at a specific time, offering a snapshot of relational structures. For example, Schröpfer, et al. [

13] developed a stakeholder knowledge network for sustainable construction projects, revealing that tightly knit subgroups facilitate knowledge sharing and innovation. Abdallah, et al. [

14] employed SNA to link BIM functions with problems and quantify the relationships between them. However, such static approaches fail to account for temporal evolution, which is critical in long-term, multi-phase construction projects. This limitation is particularly pronounced when analyzing the social impact of projects, as stakeholder influence and collaboration patterns are not static but evolve with project progression.

To address this limitation, longitudinal SNA incorporates time-series data to track changes in network topology across different project stages. For instance, Abbsaian-Hosseini, et al. [

15] constructed weekly collaboration networks among construction crews and found that centrality metrics correlated with schedule adaptability, suggesting that crews with higher centrality should be prioritized in schedule adjustments to minimize disruptions. Similarly, Pirzadeh and Lingard [

16] mapped communication networks at key design milestones and observed that network density and central roles evolved as stakeholders entered or exited the project, directly impacting design decision-making processes. Despite these advances, a critical synthesis reveals that few longitudinal SNA studies in construction explicitly integrate project work structures to contextualize collaboration within specific, evolving project tasks. This omission limits the ability to explain why network structures change, separating descriptive network visualization from actionable management insights rooted in project execution.

Furthermore, current research remains limited in capturing the phase-specific evolution of collaborative relationships in construction projects. Many studies also overlook the quantitative intensity of collaborations, often reducing relationships to binary existence rather and weighted interactions [

17]. The integration of project phased delivery with stakeholder dynamics and their associated work tasks is underdeveloped, hindering a holistic understanding of how collaboration evolves throughout the project lifecycle and how it can be managed effectively for social benefit.

To overcome these gaps, this study employs longitudinal SNA to construct and analyze collaborative networks across multiple project phases. By quantifying relationship strength through collaboration frequency and integrating a WBS to contextualize tasks, we capture both the structural and temporal dimensions of stakeholder interactions. This approach enables a nuanced analysis of collaboration intensity, stakeholder centrality, and network cohesion across phases, providing project managers with evidence-based insights to enhance collaborative efficiency and project performance.

3. Methodology

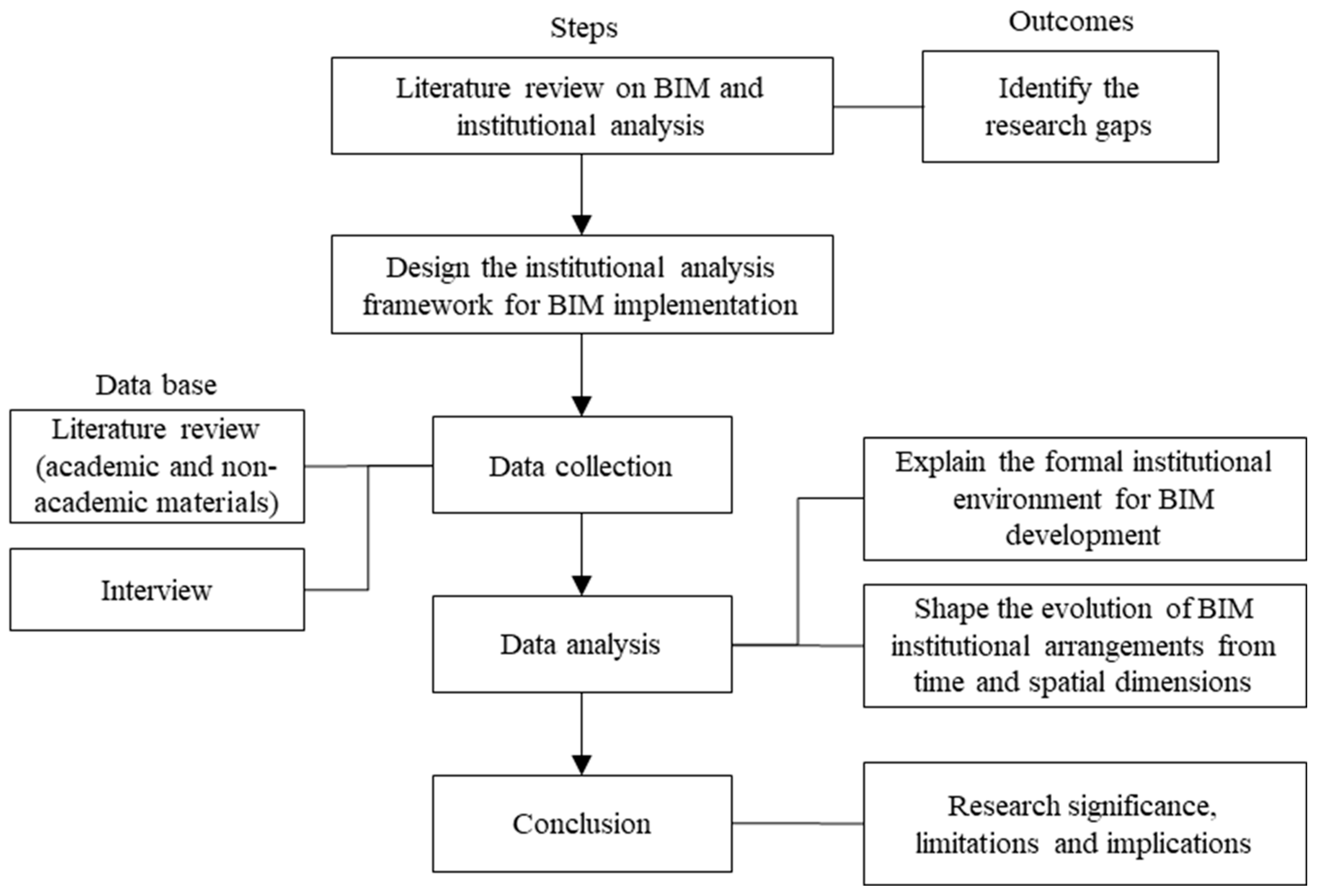

A comprehensive literature review was conducted to establish a theoretical foundation and identify research gaps. Given that the examination of institutional arrangements is highly context-dependent, multiple forms of evidence were utilized. The study began with a targeted literature search to confirm the research problems. A comprehensive data collection and processing were then conducted to investigate the implementation of BIM in China, as well as the institutional environment. The research data included a review of the academic literature, market reports, standards and policy documents, and in-depth interviews. The research flow is shown in

Figure 1.

3.1. Literature Review

A comprehensive literature review was conducted to establish the theoretical foundation for this study and to identify pertinent research gaps. The review focused on several key domains, including stakeholder management in construction projects, the application of SNA within the AEC sector, the influence of BIM on collaborative practices, and the integration of project work structures such as the WBS with relational analyses.

Existing research underscores the critical role of effective stakeholder collaboration in achieving successful project outcomes and positive social impacts. However, the inherent complexity of construction projects, characterized by numerous participants, extended lifecycles, and multi-phase processes, presents significant challenges to seamless collaboration. Inefficiencies in interaction and information exchange often lead to adverse project consequences, thereby diminishing potential societal benefits.

SNA has emerged as a prominent methodological approach for examining the relational fabric of collaboration in AEC projects. By modeling stakeholders as nodes and their interactions as links, SNA provides quantitative insights into network structure, key influencers, and information flow dynamics [

11]. Despite its utility, a critical synthesis of the literature reveals that many SNA applications in construction offer static or cross-sectional views. This limitation hinders the ability to capture the temporal evolution and phase-specific dynamics of collaboration networks throughout the project lifecycle. Furthermore, a notable gap exists in the integration of SNA with foundational project management frameworks like the WBS, which is essential for contextualizing collaboration within specific project tasks and phases.

The digital transformation driven by BIM has reconfigured collaboration frameworks within the construction industry. BIM supports integrated project delivery, enhances visualization, and improves decision-making processes through the restructuring of conventional information-exchange networks. Although its capacity to reshape communication pathways and introduce novel professional roles is widely recognized, empirical studies that examine the impact of BIM on collaborative networks across various project phases remain underexplored. Specifically, there is a lack of studies that systematically link BIM-induced changes in work tasks, as defined by the WBS, to the evolution of stakeholder collaboration networks and their social dimensions.

This literature review confirms the necessity for an analytical framework that can dynamically trace and quantify the evolution of collaborative relationships. Such a framework should integrate longitudinal SNA with project work structures to provide a more holistic understanding of collaboration dynamics. The proposed study aims to address these identified gaps by developing a comprehensive framework that combines SNA, CSS, and WBS, thereby contributing to enhanced collaborative efficiency and socially sustainable construction management practices.

3.2. In-Depth Interviews

In-depth interviews were conducted to provide detailed information about interviewees’ experiences and perceptions. A semi-structured interview schedule was adopted to collect information by personal interviews about the implementation of BIM. The research team prepared in advance, aiming to discover the following in the interviews: (1) the history of the BIM implementation in the construction industry; (2) the barriers, benefits and challenges of the BIM implementation as experienced by the interviewees; (3) interviewees’ perceptions regarding how to promote the BIM implementation in the construction industry; (4) impact of government intervention and institutional arrangements on the BIM implementation; and (5) recommendations for the BIM implementation in the future. Long interview techniques were used to guide the interviews using a series of open-ended questions pertaining to the BIM implementation. Interviews were recorded and transcribed accordingly. The research team conducted formal and informal in-depth interviews (over 30 h), with representatives distributed among seven key stakeholder and end-user groups (as shown in

Table 1): (1) government agency; (2) research institution; (3) property owner; (4) design company; (5) construction company; (6) consulting company; and (7) software company. The interviews were conducted either in person or via VOOV meetings. Finally, based on the interview records and the data collected from the interviewees, the key players, symbiotic relationships, the institutional environment, and the BIM practices are identified and analyzed. According to the interviews, most of the respondents believe that the government agency and the clients are the key players to promote BIM application. Some interviewees believed that some of the BIM standards and guidelines currently in use are not fully tailored to meet the needs of engineering practices in China. Most of the interviewees suggested that the most urgent thing at this stage is to develop and improve BIM standards, laws and regulations, and establish a talent training mechanism, followed by the establishment of an industry regulatory system and incentive policies.

To achieve the research objectives, the study primarily focuses on the following three aspects: (1) Based on the findings from the literature review and addressing current research gaps, this study proposes a methodology and steps for establishing an analytical framework to examine stakeholder collaboration relationships across different phases of construction projects, tailored to the characteristics of such relationships. (2) Constructing a network model of stakeholder collaboration relationships at each phase of construction projects. Building upon the analytical framework, this involves adopting social network thinking and methodologies to develop the network model. (3) Select a case study to analyze stakeholder collaboration within the project, validating the feasibility of applying the framework and model.

In the first phase, based on the results of the literature analysis, we explore the collaborative processes among stakeholders in construction projects, examining the formation and evolution of stakeholder relationships across project phases. Building on this foundation, we utilize the WBS to define tasks for each phase. By decomposing project work hierarchically, we ultimately break down the project into the lowest-level work units (work packages), thereby determining the specific tasks for each phase. Second, through further literature analysis, we examine the stakeholders involved in each phase, their primary responsibilities, and the potential collaborative relationships that may form among them. Finally, SNA is employed to map the collaborative relationship networks for each phase, thereby establishing a framework for analyzing stakeholder collaboration.

In the second phase, based on the collaborative relationship analysis framework, a 2-mode network model for the task-level network and a 1-mode network model for the stakeholder-level network are constructed. Simultaneously, network metrics are selected and their results interpreted. By applying this model to generate and analyze task-level and stakeholder-level networks, we can further explore collaborative relationships among stakeholders across project phases, their collaborative characteristics and patterns, thereby providing insights to enhance stakeholder collaboration and improve collaborative efficiency.

In the third phase, networks are constructed based on actual engineering cases to analyze stakeholder collaboration relationships within these cases, thereby validating the feasibility and effectiveness of the framework and model application. Recommendations are proposed based on network measurement results, providing guidance for adjusting and directing stakeholder collaboration.

4. Framework of Collaborative Relationship Analysis in Construction Projects

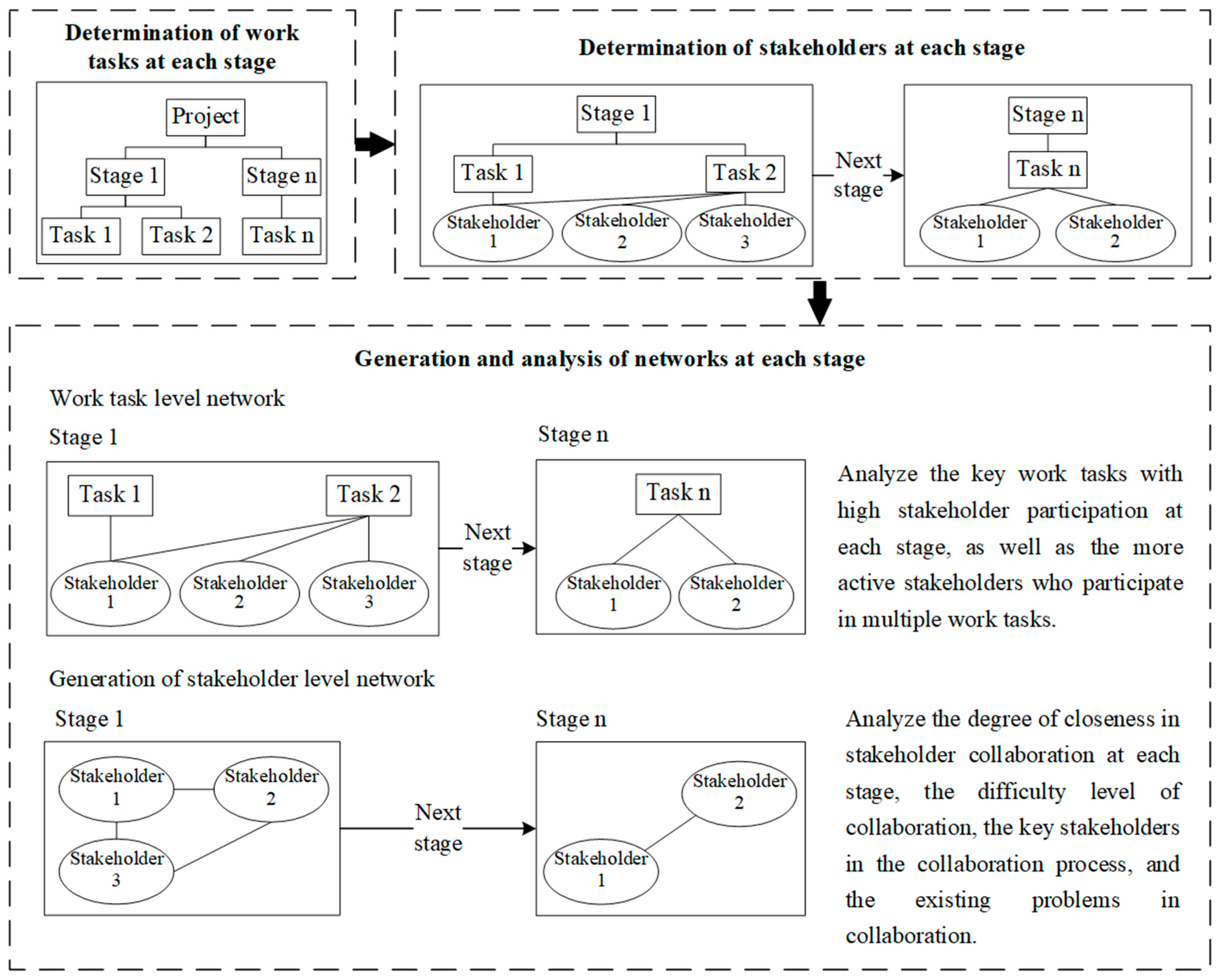

The proposed framework (as shown in

Figure 2) for analyzing stakeholder collaboration in construction projects comprises three main components: (1) Definition of tasks for each phase using WBS; (2) Identification of stakeholders involved in each phase; (3) Generation and analysis of task-level and stakeholder-level networks.

Previous research indicates that decomposing projects into work tasks using WBS, identifying stakeholder-involved tasks, and extracting collaboration information from these tasks holds theoretical feasibility. However, these studies have not addressed changes in stakeholder collaboration relationships across project phases, quantitative methods for collaboration intensity, nor the impact of work tasks on collaboration relationships. Wang, et al. [

18] employed a four-level WBS to identify stakeholder collaboration relationships in railway projects, using collaboration frequency to quantify relationship strength. This study demonstrated the theoretical feasibility of using collaboration frequency for quantification. However, it did not generate or analyze task-level networks, nor did it examine the impact of work tasks on stakeholder collaboration relationships across project phases. This study indicates the necessity of integrating project phases with stakeholder relationship research, but it did not further explore key work tasks at each phase or the impact of work tasks on stakeholder relationships. Building upon the above research, this paper establishes an analytical framework for construction project stakeholder collaboration. It comprehensively considers the influence of factors such as work tasks and stakeholder responsibilities on collaborative relationships, enabling the analysis and exploration of stakeholder collaboration across project phases. Consequently, this framework provides a reference for coordinating construction project stakeholders, aiming to enhance collaborative efficiency among all parties involved.

4.1. Determination of Work Tasks in Each Phase

Based on the preceding analysis of work tasks in various construction project phases, the WBS method is employed to decompose the project and identify specific work tasks for each phase. It is important to note that project decomposition lacks a unified standard or method; the WBS must be tailored to the specific construction project.

Through literature analysis and interviews with personnel from general contracting units, BIM consulting firms, and real estate enterprises, it was found that most construction projects in China adopt a 4-level WBS (including the project level). Different managing entities may develop different WBSs; for example, the owner’s WBS may differ from the general contractor’s. Furthermore, many enterprises with general contracting qualifications develop their own generic project WBS. In practice, the lowest-level work unit often comprises multiple work activities. For instance, the work unit “Construction Drawing Design” can be further decomposed into design activities for different disciplines and inter-disciplinary information exchange activities. Therefore, to objectively identify and quantify collaboration among parties, an activity level is added to the WBS hierarchy based on literature analysis and interview results.

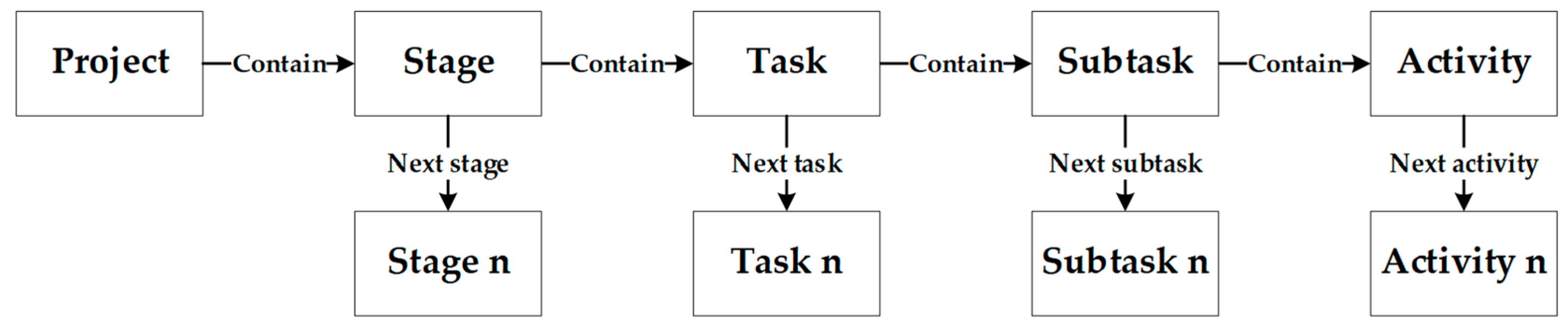

As shown in

Table 2, Level 1 is the Project level. Level 2 is the Phase level, decomposed according to the implementation process. The purpose is to investigate changes in stakeholder collaboration across phase work units; thus, networks are constructed per phase. Level 3 is the Task level; each phase consists of different tasks. From Level 3 onwards, decomposition considers the work characteristics of each phase (e.g., feasibility study stages in decision phase, deliverable-based decomposition in construction phase). Level 4 is the Sub-task level. Level 5 is the Activity level, representing the finest granularity—the specific activities where stakeholders directly participate and collaborate. The logical relationship between WBS levels is shown in

Figure 3. In this 5-level WBS, the lowest-level work unit is the activity.

In summary, when using WBS to determine tasks per phase, the specific project context must be considered to define the lowest-level units and their logical relationships. As work packages often consist of multiple activities, adding the activity level ensures the lowest unit captures direct collaboration. Subsequently, WBS units are coded to finalize the project WBS and define the tasks for each phase.

4.2. Identification of Stakeholders at Each Stage

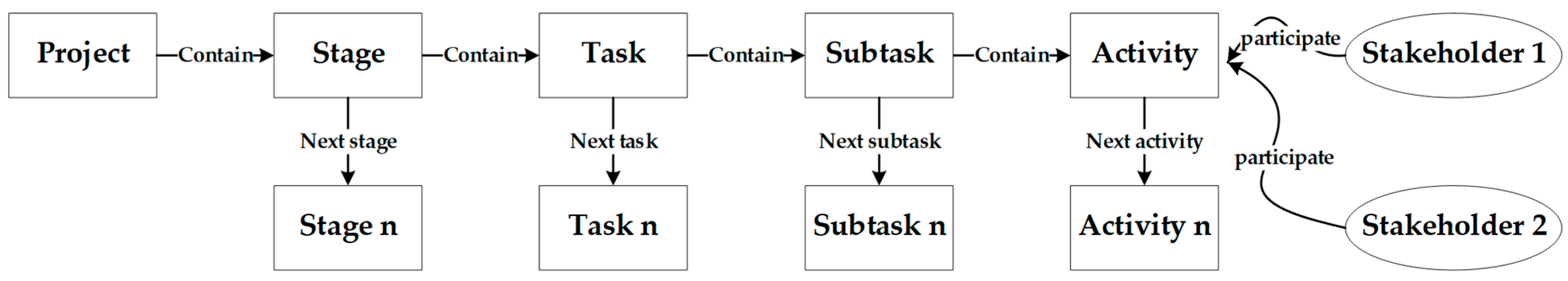

After identifying the lowest-level work units for each phase, proceed to identify the lowest-level work units involving stakeholder participation. As shown in

Figure 4, the lowest-level work unit is an activity unit. Stakeholder 1 and Stakeholder 2 both participated in the same work activity, thereby collaborating within this activity. Consequently, a collaborative relationship formed between Stakeholder 1 and Stakeholder 2 during this phase.

Different parties participate in different work units, and the frequency of collaboration varies. Collaboration involves information exchange, communication, and knowledge sharing. A higher number of collaborative interactions indicates more frequent exchanges and reflects closer relationships among stakeholders. Therefore, the strength of collaborative relationships is influenced by collaboration frequency. Quantitative research must account for this, not only determining the existence of relationships but also measuring their intensity using collaboration frequency as a metric.

In conclusion, after defining the project WBS, the work tasks (lowest-level units) involving stakeholders are identified. Since these units belong to different phases, the number of collaborations between parties per phase can be tallied. Collaboration frequency serves as the metric for relationship strength, laying the groundwork for constructing phased collaborative relationship networks.

4.3. Construction and Analysis of Networks in Each Phase

After identifying stakeholder collaboration within the lowest-level work units (activities) per phase, relationship networks are generated and analyzed for each phase. These are divided into task-level and stakeholder-level networks.

Task-Level Network (2-Mode Network): This is an affiliation network between stakeholders and tasks (activities). As tasks significantly influence stakeholder collaboration, analyzing this network provides insights into which tasks stakeholders participate in and who they collaborate with within those tasks. SNA metrics are used to analyze this network, identifying key tasks (e.g., those involving many stakeholders, requiring focused management coordination).

In the task-level network, nodes represent both tasks (WBS units involving collaboration) and stakeholders. Stakeholders are defined based on PMI (Project Management Institution) [

17], adapted for this study: individuals or groups who actively participate in the construction project, collaborate and coordinate with others based on shared rules, and influence project performance positively or negatively through their work.

Links in the 2-mode network represent affiliation (participation) between a stakeholder and a task. Conditions for links: (1) Any task must have at least two stakeholders linked to it (weight > 0), as solo tasks are excluded from collaboration analysis. (2) Any stakeholder must be linked to at least one task.

Stakeholder-Level Network (1-Mode Network): This network is derived from the 2-mode network. The steps are: (1) Map stakeholders from the 2-mode network to nodes in the 1-mode network. (2) For stakeholders participating in the same task(s) in the 2-mode network, calculate the number of tasks they co-participate in. This co-participation frequency defines the strength of the collaborative relationship between them. (3) Generate the 1-mode network based on these strengths.

In the stakeholder-level network, nodes represent collaborating stakeholders (defined as above). Links represent collaborative relationships, defined as: relationships formed when stakeholders, based on shared rules, work together on project tasks, coordinating, cooperating, and exchanging resources to achieve common goals. Link weights are assigned using collaboration frequency as the measure of relationship strength.

5. A Network Model for Exploring BIM’s Impact on Information Exchange

This study develops a novel network model that integrates whole-network SNA, egocentric SNA, and CSS to investigate the impact of BIM on information exchange networks. As shown in

Figure 5, the egocentric network (individual SNA) and CSS are combined to address data limitations, while indicators from whole network analysis are adopted and adapted to investigate network structure. The model construction involves three steps: (1) Collect data on communication frequency among project participants from scenarios both with and without BIM application; (2) Analyze changes in individual network structure between these two scenarios; (3) Explore the impact of BIM on the information exchange network.

5.1. Motivation for the Model

Many studies have noted that BIM application affects the information exchange networks, but further analysis to identify and quantify this impact is still lacking. For example, Lu, Xu and Söderlund [

6] founded that BIM has the potential to improve communication efficiency; Okakpu, et al. [

19] proposed that BIM could improve the fragmented information exchange and the relationship network density will be increased. Research assumptions are thus proposed: (1) the frequency of information exchange among stakeholders, and the position of stakeholders in the information exchange network are related to the application of BIM; (2) the frequency of information exchange among stakeholders and the positions of stakeholders in the information exchange network may be changed with BIM application. The objectives of the constructed model include: (1) to capture whether there is a relationship between the information exchange frequency of the stakeholders and the BIM application; and (2) to detect whether the positions of the focal actors change before and after the BIM application. To achieve the above objectives, the network type, the network components, and the network metrics will be determined in the model.

5.2. The Selection of Network Types

The network types attempts to integrate the whole network, individual network, and CSS for the following reasons: (1) most network analysis of construction projects rely on random sampling and the limited data makes the results dependent on the social entities who participated in [

20]. Moreover, the individual network of SNA has some limitations in analyzing the structure of the relational network. Thus, CSS is adopted to integrate with the individual network of SNA to supplement the data and explore the changes in the information exchange network before and after BIM application; (2) the whole network of SNA has been widely used to analyze the overall structure of the relationships network. The indicators of the whole network can be introduced into the individual network to analyze the structural changes in the information exchange network before and after the application of BIM.

5.3. Data Collection

Leveraging the advantage of random sampling, the individual network approach is used to collect data from multiple focal actors (egos). CSS is additionally employed to obtain data on information exchange among other actors (alters) as perceived by the ego. This allows gathering data on both the ego’s direct relationships and their perception of the broader network through interviews.

5.4. Network Components

Information exchange activities are mapped within sociograms where actors are nodes and information exchanges are links [

21]. Key nodes and their connections are identified. SNA was introduced to construction research in the 1990s and has grown popular for investigating project participant relationships [

22].

Network nodes: The network nodes in this study represent the stakeholders in the construction projects. Therefore, how to identify the key stakeholders of the construction project is an important issue for the model. Based on the research assumptions, key stakeholders and their positions may change with BIM. Individual network questionnaires can identify key stakeholders (perceived importance), and network node analysis can reveal position changes.

The connections of network nodes: Represent relationships between individuals, specifically information exchange. Tie strength (frequency) is analyzed via edge weights. Information exchange can be unidirectional or bidirectional; in construction projects, it is typically bidirectional. As exchange frequencies vary, a weighted (valued) network is adopted, not a simple binary (exists/does not exist) network.

5.5. Determination of Network Indicator

Several network metrics is utilized to examine structural transformations in information-exchange networks following the implementation of BIM. These indicators offer quantitative measures for evaluating changes in connectivity, actor prominence, and information flow within the network.

Density: Network density is defined as the ratio of the number of actual ties present to the total number of possible ties among all nodes within a network. It serves as a fundamental indicator of overall network cohesion, reflecting the general level of connectedness and the potential intensity of interaction among stakeholders. A higher density value suggests more frequent exchanges and stronger relational integration, whereas a lower density may indicate a more sparse or fragmented communication structure [

23].

Centrality Measures: In this study, centrality measures are calculated specifically for focal actors (egos). To ensure comparability across networks of differing sizes, these indicators are standardized, thereby removing the influence of network scale on the metric values.

Degree centrality: Degree centrality refers to the number of direct connections maintained by a node. It reflects a node’s local connectivity and immediate involvement in the network. Within the context of project information exchange, degree centrality indicates an actor’s direct access to other stakeholders and its capacity for information reception and dissemination [

24].

Betweenness Centrality: Betweenness centrality measures the extent to which a node lies on the shortest paths between other pairs of nodes. Nodes with high betweenness centrality occupy brokerage positions, enabling them to facilitate, control, or constrain information flow between otherwise disconnected segments of the network [

25]. In construction project networks, this metric captures an actor’s role in bridging information across subgroups and influencing communication dynamics.

To ensure comparability across networks of varying sizes, centrality measures are normalized, thereby removing the influence of network scale. This standardization allows for meaningful comparison of structural positions before and after BIM implementation.

The research assumptions can thus be specified using these metrics: (1) examining the relationship between BIM application and the density of the perceived ego-network (reflecting overall alter connectivity) and the ego’s degree centrality (reflecting its connectedness); and (2) detecting changes in these metrics before and after BIM application. Density helps measure the frequency of information exchange among the stakeholders surrounding the ego, and degree centrality measures the ego’s importance within its immediate network.

6. Case Study

To demonstrate the practical application and validity of the proposed analytical framework and network models, a case study was conducted. This section details the project background, data collection and processing, network generation, analysis of results, and the validation procedure employed.

6.1. Project Overview

A Power Plant project, located in Fujian Province of China, was selected for empirical analysis for two primary reasons. First, the project utilized an Engineering, Procurement, and Construction (EPC) contract model, which is widely adopted. Furthermore, the project incorporated numerous BIM applications, fostering intensive stakeholder collaboration, thus providing a robust context for validating the proposed framework and models. Second, the proposed collaboration analysis method necessitates comprehensive data, including the project WBS, detailed work tasks, activities, and participating stakeholders. This required a combination of document analysis, surveys, and interviews, necessitating strong support from the project participants, which was available for this case.

Key BIM applications within the project included 3D model creation (for design and site layout), quantity take-off, 3D visualization (for clash detection and design optimization), process simulation (4D construction sequencing), cost calculation, and data updating.

6.2. Data Collection and Processing

Based on the stakeholder identification method outlined in

Section 4.2, surveys and interviews were designed and administered. The identification process involved preliminary and supplementary stages using document analysis, questionnaires, and interviews. The initial identification yielded 7 primary stakeholder organizations. A subsequent supplementary survey, employing a snowball sampling technique, refined these into 25 distinct stakeholder roles (e.g., Design Manager, BIM Modeler, Procurement Manager) to accurately represent the implementing entities involved in collaboration. The final list of 25 stakeholders, their codes, and primary responsibilities are summarized in

Table 3.

6.3. Network Generation

6.3.1. Task-Level Network (2-Mode Network) Generation

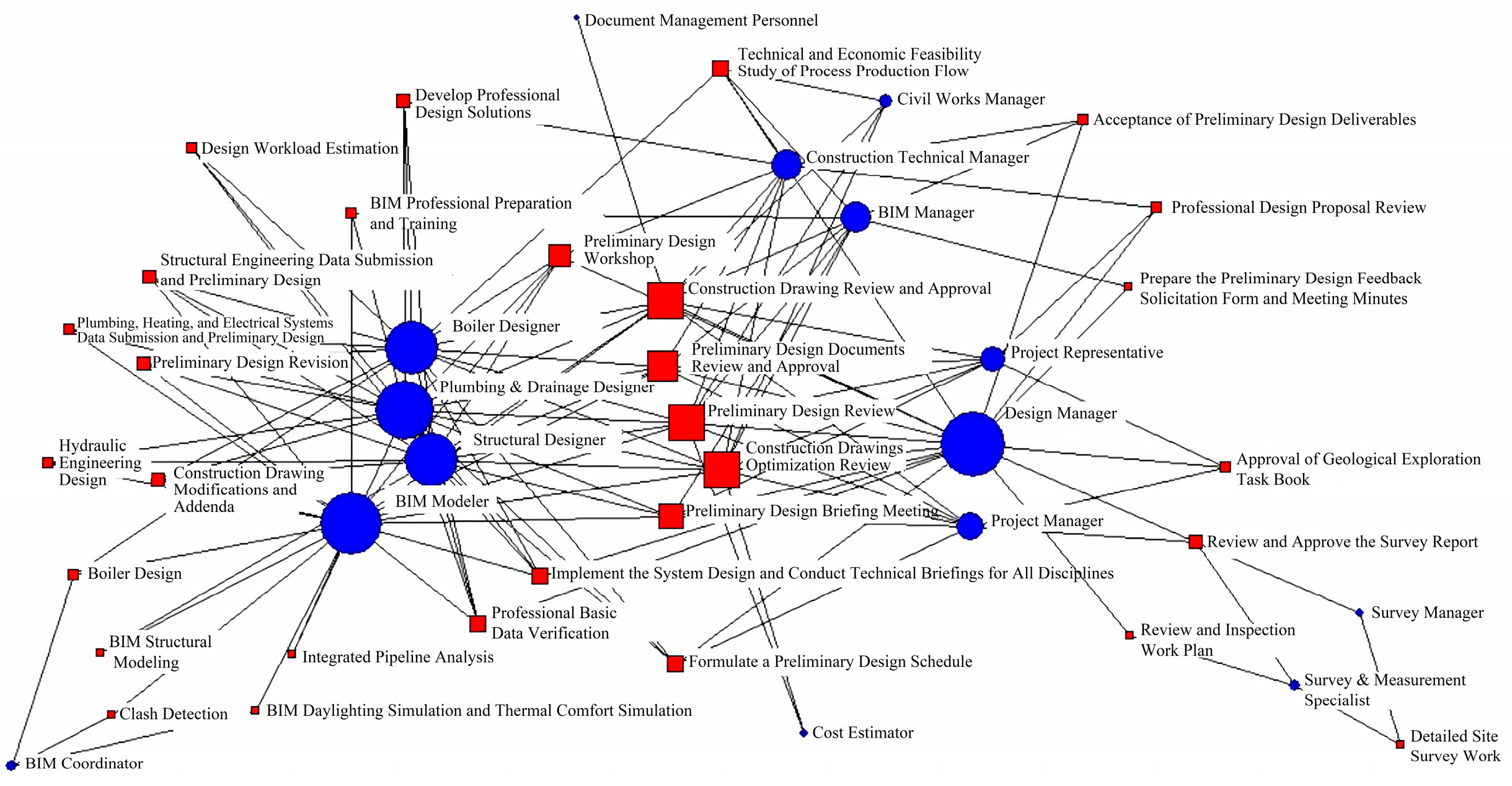

Using UCINET 6 software, the task-level (2-mode) networks for the Design phases were visualized, as shown in

Figure 6. In these visualizations, square nodes represent work activities, circular nodes represent stakeholders, and connecting lines indicate participation. A preliminary visual analysis of the Design Phase network indicated that activities like ‘Preliminary Design Review’ and ‘Construction Drawing Optimization Review’ were central, involving numerous stakeholders. Key stakeholders appeared to be the Design Manager (S4), various professional designers (S5, S6, S7), and BIM Modelers (S16).

6.3.2. Stakeholder-Level Network (1-Mode Network) Generation

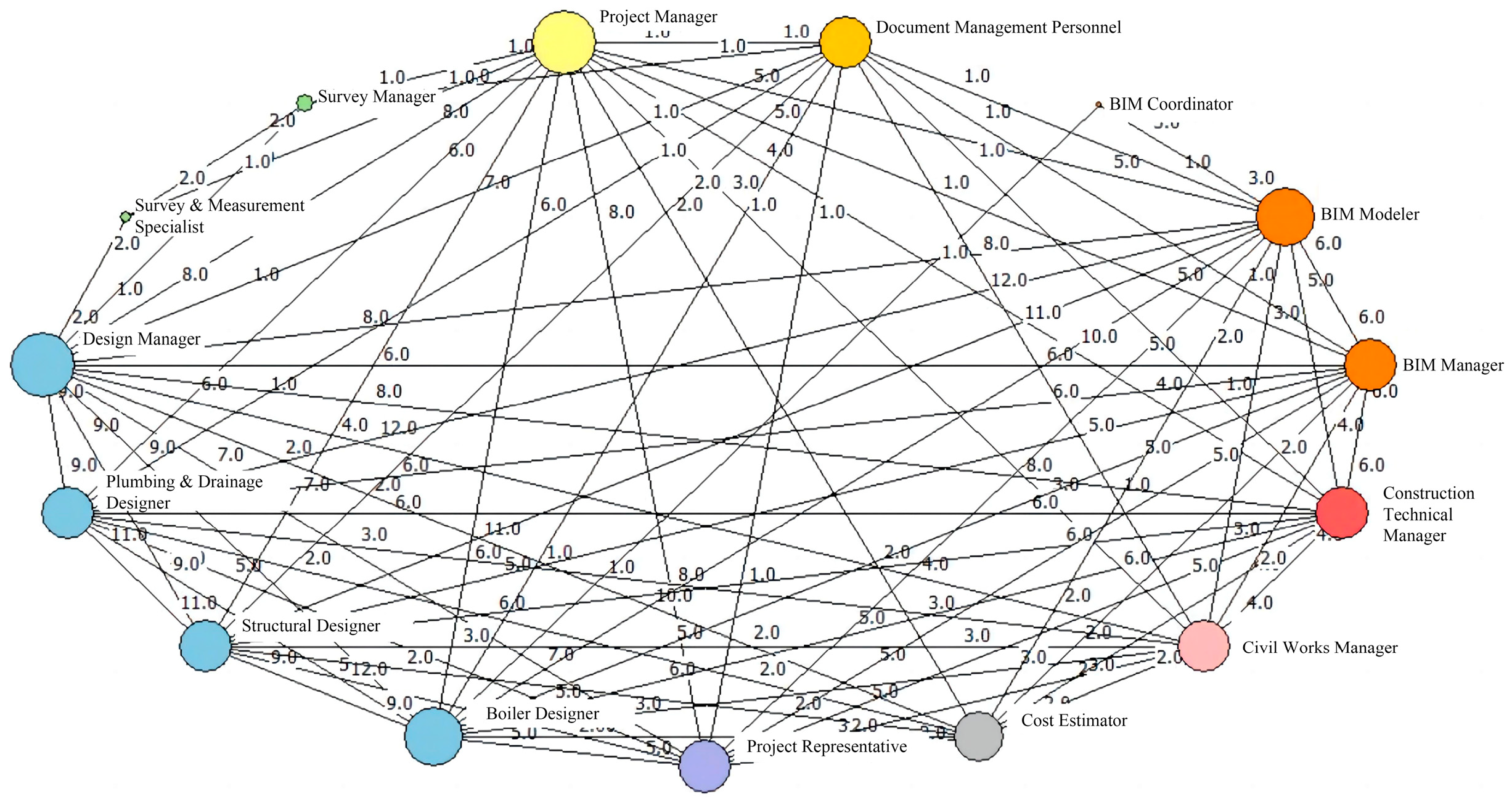

The 1-mode stakeholder collaboration networks were derived by transforming the 2-mode matrices. The collaboration frequency between any two stakeholders was calculated based on their co-participation in the same work activities within a phase. This frequency defined the tie strength (weight) in the 1-mode network. The resulting collaboration matrices were used to generate the stakeholder-level networks, visualized in

Figure 7. Nodes represent stakeholders, lines represent collaborative relationships, and line weights indicate collaboration frequency. Node size again corresponds to degree centrality, and nodes are color-coded by their primary organizational affiliation or role. Visual inspection of the Design Phase network suggested relatively balanced collaboration, with design-related stakeholders being most interconnected.

6.4. Network Analysis and Validation

6.4.1. Whole Network Analysis

UCINET 6 was used to analyze whole-network metrics for the stakeholder-level (1-mode) networks in both phases, as presented in

Table 4.

The changing metrics confirm that stakeholder collaboration structures evolve across project phases. The increase in network size from the Design to Construction Preparation phase reflects the entry of new stakeholders (e.g., site design representatives). The decrease in network density and clustering coefficient, coupled with an increase in average path length and degree centralization, indicates a transition from a tightly knit, collaborative design team to a more dispersed, less cohesive network with a more pronounced hierarchical structure centered around a few key figures like the Civil Works Manager in the later phase.

6.4.2. Key Node Analysis

Centrality metrics (Degree, Betweenness, Closeness) were calculated for all stakeholders in both phases.

Table 5 presents the top 5 stakeholders based on Degree Centrality in each phase.

In the Design Phase, the most central stakeholders were design-related personnel, with the Design Manager acting as a central coordinator. The high centrality of BIM Modelers underscores their integrative role in the design process. In the Construction Preparation Phase, the network center shifted decisively to the Civil Works Manager (S13), reflecting their pivotal role in organizing on-site preparation activities. The centrality of design professionals decreased significantly as their direct involvement lessened.

6.4.3. Validation of Model Application

The validation of the framework and model involved comparing the analytical results against project reality through two primary methods:

Cross-referencing with Project Documentation and Roles: The identification of the Civil Works Manager (S13) and Procurement Manager (S3) as the most central figures in the Construction Preparation Phase was consistent with their formally assigned responsibilities for site preparation and procurement, as outlined in project organizational charts and job descriptions. Similarly, the central role of the Design Manager (S4) and BIM Modeler (S16) during the Design Phase aligned with project expectations.

Expert Feedback: Preliminary findings, including the identified key stakeholders, collaboration bottlenecks (e.g., lower-than-expected collaboration for the BIM Coordinator (S17) in the Design Phase), and phase transitions in network structure, were discussed with the project director (S2) and design manager (S4). They confirmed that the network analysis accurately reflected the actual collaboration patterns and challenges experienced during the project. For instance, the observed isolation of the BIM Coordinator led to a discussion about role clarity, corroborating the model’s utility in pinpointing operational inefficiencies.

This triangulation of quantitative network results with qualitative project data and expert opinion supports the validity of the framework for analyzing real-world stakeholder collaboration.

7. Conclusions and Recommendations for Future Work

Over the past two decades, SNA has become a vital methodology in construction management research, providing profound insights into the relational dynamics among project stakeholders. However, conventional approaches, including whole network and egocentric network analyses, often face limitations in capturing the contextual and temporal nuances of stakeholder collaboration, particularly in projects with significant social implications. Through a comprehensive literature review and theoretical synthesis, this study proposes an integrated analytical framework that synergistically combines whole network SNA, egocentric SNA, and CSS. This integrative approach mitigates the methodological constraints of individual methods while enriching the understanding of how collaborative relationships evolve and influence social outcomes in construction projects.

The adoption of BIM is widely recognized for its potential to transform information exchange and reconfigure communication networks among stakeholders. Nevertheless, empirical studies that quantitatively assess BIM’s impact on these networks and their subsequent social ramifications remain scarce. This study addresses this gap by developing a novel network model that integrates structural insights from whole network analysis, the pragmatic data collection advantages of egocentric networks, and the contextual depth provided by CSS. This model was successfully applied and validated in a case study, demonstrating its ability to capture phase-specific collaboration dynamics, identify key stakeholders and tasks, and provide actionable insights for improving collaborative efficiency.

While the proposed framework and model offer significant insights, several limitations should be noted. First, the relationship strength metric relies solely on collaboration frequency. Future research could explore incorporating task effort or duration. Second, the case study focuses on an EPC project; applicability to other contract models requires further verification. Third, data collection was challenging and relied partially on stakeholder recall and willingness to participate, potentially introducing bias. Finally, the WBS definitions require adaptation to specific project contexts.

Future research should build upon this foundation in the following directions: (1) Empirical Validation in Diverse Contexts: Testing the framework across various project types, scales, and cultural settings; (2) Integration of Institutional Factors: Incorporating variables like contractual models and policy frameworks; (3) Advanced Longitudinal Analysis: Leveraging digital trace data while developing methods to handle data sparsity and inconsistency; (4) Synergy with Emerging Technologies: Exploring IoT and AI for automated data collection and analysis; (5) Policy and Practice-Oriented Guidance: Translating findings into practical toolkits, templates, and step-by-step guides for practitioners and policymakers to enable direct application of the research insights.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.Y.; Methodology, H.X.; Formal analysis, Y.Y. and H.X.; Writing—original draft preparation, Y.Y. and H.X.; Writing—review and editing, Y.Y. and H.X.; Project administration, Z.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 71673240 and 42271179) and the Major National Social Science Programs of China (Grant No. 24&ZD081).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study is primarily a theoretical and methodological contribution, proposing an analytical framework and network model for studying stakeholder collaboration in construction projects. The research does not involve human subjects in a manner that requires ethical approval.

Informed Consent Statement

Participants were verbally informed during the interview.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Bolshakova, V.; Guerriero, A.; Halin, G. Identifying stakeholders’ roles and relevant project documents for 4D-based collaborative decision making. Front. Eng. Manag. 2019, 7, 104–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlish, K.; Sullivan, K. How to measure the benefits of BIM-A case study approach. Autom. Constr. 2012, 24, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Espada, J.M.; Fuentes-Bargues, J.L.; Sánchez-Lite, A.; González-Gaya, C. Complexity Assessment in Projects Using Small-World Networks for Risk Factor Reduction. Buildings 2024, 14, 4065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, M.; Li, Z.; Li, X.; Luo, X. Managing stakeholder-associated risks and their interactions in the life cycle of prefabricated building projects: A social network analysis approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 323, 129102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Cao, J.; Wu, G.; Zhao, X.; Zuo, J. Interenterprise collaboration network in international construction projects: Evidence from chinese construction enterprises. J. Manag. Eng. 2022, 38, 05021018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Xu, J.; Söderlund, J. Exploring the Effects of Building Information Modeling on Projects: Longitudinal Social Network Analysis. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2020, 146, 04020037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Fang, S.; Shi, T.; Wales, N.; Skitmore, M. Enhancing stakeholder engagement and performance evaluation in building design using BIM and VR. Autom. Constr. 2025, 175, 106191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antwi-Afari, M.F.; Li, H.; Pärn, E.A.; Edwards, D.J. Critical success factors for implementing building information modelling (BIM): A longitudinal review. Autom. Constr. 2018, 91, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zech, P.; Hammes, S.; Goldin, E.; Geisler-Moroder, D.; Breu, R.; Pfluger, R. From BIM to digital twin: A transformation process through advanced control modeling and automated commissioning using daylight and artificial lighting as examples. Energy Build. 2025, 329, 115184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tantawy, M.; Kosbar, M.M.; Nour, S.M.; Mansour, N.; Ehab, A. Leveraging BIM for Proactive Dispute Avoidance in Construction Projects. Buildings 2025, 15, 1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Le, Y.; Chan, A.P.C.; Hu, Y.; Li, Y. Review of the application of social network analysis (SNA) in construction project management research. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2016, 34, 1214–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Lu, W.; Papadonikolaki, E. Human-organization-technology fit model for BIM adoption in construction project organizations: Impact factor analysis using SNA and comparative case study. J. Manag. Eng. 2022, 38, 04022004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schröpfer, V.L.M.; Tah, J.; Kurul, E. Mapping the knowledge flow in sustainable construction project teams using social network analysis. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2017, 24, 229–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdallah, A.; Doloi, H.; Holzer, D. Exploring the application of BIM in Tanzanian public sector projects using social network analysis. Built Environ. Proj. Asset Manag. 2023, 13, 552–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbsaian-Hosseini, S.A.; Liu, M.; Hsiang, S.M. Social network analysis for construction crews. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2019, 19, 113–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirzadeh, P.; Lingard, H. Understanding the dynamics of construction decision making and the impact on work health and safety. J. Manag. Eng. 2017, 33, 05017003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mok, K.Y.; Shen, G.Q.; Yang, J. Stakeholder management studies in mega construction projects: A review and future directions. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2015, 33, 446–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.Q.; Thangasamy, V.K.; Hou, Z.Q.; Tiong, R.L.K.; Zhang, L.M. Collaborative relationship discovery in BIM project delivery: A social network analysis approach. Autom. Constr. 2020, 114, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okakpu, A.; GhaffarianHoseini, A.; Tookey, J.; Haar, J.; Hoseini, A.G. An optimisation process to motivate effective adoption of BIM for refurbishment of complex buildings in New Zealand. Front. Archit. Res. 2019, 8, 646–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabani Ardakani, S.; Nik-Bakht, M. Social network analysis of project procurement in Iranian construction mega projects. Asian J. Civ. Eng. 2021, 22, 809–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.N.; Liu, X.; Xie, H.; Zhang, Z. Towards an Integrated Framework for Information Exchange Network of Construction Projects. Buildings 2023, 13, 763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solis, F.; Sinfield, J.V.; Abraham, D.M. Hybrid approach to the study of inter-organization high performance teams. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2013, 139, 379–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.S.; Muhuri, S.; Mishra, S.; Srivastava, D.; Shakya, H.K.; Kumar, N. Social Network Analysis: A Survey on Process, Tools, and Application. ACM Comput. Surv. 2024, 56, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayoub, J.; Lotfi, D.; Hammouch, A. Link prediction using betweenness centrality and graph neural networks. Soc. Netw. Anal. Min. 2023, 13, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.L.; Cheng, M.; Cheng, X.T. Exploring the Project-Based Collaborative Networks Between Owners and Contractors in the Construction Industry: Empirical Study in China. Buildings 2023, 13, 732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |