Abstract

Construction progress monitoring remains predominantly manual, labor-intensive, and reliant on subjective human interpretation. Human dependence often leads to redundant or unreliable information, resulting in scheduling delays and increased costs. Advances in drones, point cloud generation, and multisensor data acquisition have expanded access to high-resolution as-built data. However, transforming data into reliable automated indicators of progress poses a challenge. A limitation is the lack of robust material-level segmentation, particularly for structural materials such as concrete and steel. Concrete and steel are crucial for verifying progress, ensuring quality, and facilitating construction management. Most studies in point cloud segmentation focus on object- or scene-level classification and primarily use geometric features, which limit their ability to distinguish materials with similar geometries but differing physical properties. A consolidated and systematic understanding of the performance of multispectral and multimodal segmentation methods for material-specific classification in construction environments remains unavailable. The systematic review addresses the existing gap by synthesizing and analyzing literature published from 2020 to 2025. The review focuses on segmentation methodologies, multispectral and multimodal data sources, performance metrics, dataset limitations, and documented challenges. Additionally, the review identifies research directions to facilitate automated progress monitoring of construction and to enhance digital twin frameworks. The review indicates strong quantitative performance, with multispectral and multimodal segmentation approaches achieving accuracies of 93–97% when integrating spectral information into point cloud or image-based pipelines. Large-scale environments benefit from combined LiDAR and high-resolution imagery approaches, which achieve classification quality metrics of 85–90%, thereby demonstrating robustness under complex acquisition conditions. Automated inspection workflows reduce inspection time from 24 h to less than 2 h and yield cost reductions of more than 50% compared to conventional methods. Additionally, deep-learning-based defect detection achieves inference times of 5–6 s per structural element, with reported accuracies of around 97%. The findings confirm productivity gains for construction monitoring.

1. Introduction

Traditionally, the construction industry has been characterized by heavy reliance on manual labor and conventional supervision methods, leading to results prone to error. However, technological advances are driving changes across several processes. Employing aerial vehicles (UAVs), also known as drones and point clouds, and conducting remote monitoring [1,2,3] facilitates early detection of cracks in building walls [4,5] and enables monitoring of civil infrastructure systems via cameras [6,7,8].

Using cameras for inspection or monitoring has become common in the construction industry, and drones offer significant advantages [9,10,11]. Flexibility and the capability to capture images from various angles improve project comprehension and decision-making. Drones facilitate rapid data collection from inaccessible areas and enhance safety by reducing worker exposure to hazards [12,13]. Also, provide high-quality data for detailed analysis, making tracking construction progress cost-effective [14] and efficient, thereby reducing inspection costs [2,13]. Drones can aid several key construction activities, such as:

- Site Surveys and Mapping:

- Conducting detailed aerial surveys to create accurate topographic maps, digital terrain models (DTMs), and orthomosaic images [11,12,13].

- Generating 3D models of construction sites for planning and design purposes [14,15].

- Progress Monitoring:

- Collecting high-resolution aerial images and videos to monitor the progress of construction and compare it against the project timelines [11].

- Providing updates to stakeholders and project managers [12].

- Safety Inspections:

- Inspecting construction sites for safety hazards and compliance with safety regulations [16].

- Monitoring high-risk areas and providing real-time data to improve worker safety [17].

- Volume Calculations:

- Measuring stockpile volumes and earthwork quantities accurately using 3D models generated by UAV [12,15].

- Optimizing material management and reducing waste [14].

- Infrastructure Inspections:

- Inspecting bridges, buildings, and other infrastructure components for structural integrity and maintenance needs [10,13,18].

- Performing detailed inspections of hard-to-reach-areas without the need for scaffolding or cranes [13].

- Building Information Modeling (BIM) Integration:

- Integrating UAV-captured data with the BIM system for improved project planning, design, and management [13,19].

- Using 3D models generated from UAV data to improve accuracy and visualization in BIM [12,13,14].

Point clouds are collections of spatial data points acquired using laser scanning technologies such as Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR), terrestrial laser scanning (TLS), and photogrammetry. These technologies, including LiDAR-equipped drones, enable the generation of accurate three-dimensional digital representations of construction sites. As illustrated in Figure 1, the image on the left shows a stadium during its construction phase, while the image on the right presents a point-cloud reconstruction of the same structure. Despite being derived from different data sources, both representations capture the same geometric and spatial information, demonstrating how point clouds can faithfully reproduce real-world conditions. The digital reconstruction allows stakeholders to visually inspect the site, perform measurements, and assess progress remotely, reducing the need for physical site visits while improving the objectivity and reliability of inspections.

Figure 1.

(Left) A stadium under construction. (Right) Point-cloud reconstruction of the same structure. The close visual correspondence illustrates how point clouds enable remote inspection and progress assessment without requiring on-site visits.

In this context, Building Information Modeling (BIM) enhances point cloud technology by combining precise geometric data with details on construction elements, enabling as-built comparisons and facilitating monitoring and quality checks. BIM serves to identify discrepancies between plans and reality, a crucial aspect of Construction 4.0. Integrating point clouds with BIM enhances visualization, geometry, planning, and management by clearly illustrating the construction process. Moreover, TLS tools capture building exteriors accurately, facilitating digitalization and structural health monitoring, thus reducing errors and time/resource wastage [20,21,22,23].

Recent advancements in 3D point-cloud analysis have enhanced object recognition and scene interpretation. However, accurately identifying structural elements such as columns and beams, as well as materials such as concrete and steel, remains challenging in construction. Challenges such as data noise, occlusions, and varying lighting conditions require advanced processing techniques. Within this shift, geometry point cloud segmentation often struggles to distinguish materials that are geometrically similar [24,25].

Studies using multispectral and multimodal sensing, such as SE-PointNet++ [24] and FR-GCNet [26], demonstrate consistent improvements in overall accuracy (OA) and mean intersection over unit (mIoU) compared to baseline geometry methods [24,25]. Additionally, polarimetric multispectral LiDAR achieves nearly perfect material classification under controlled conditions [27].

Findings underscore the potential of integrating multispectral data fusion techniques for precise, timely segmentation of materials at construction sites. Applying this method can improve site monitoring and resource management. Field robustness must still be demonstrated because evaluating the model on domain shift data, such as fog, rain, snow, sensor, or camera site shifts, resulted in a decrease in mIoU. Compared with evaluation on the train-domain test set [28,29], this reveals that the dataset limitations limit the generalization of the proposed approach to construction site applications. Common benchmarks for indoor/outdoor models like S3DIS, SemanticKTTI, Semantic3D, and SensatUrban [17,28,30,31] have label schemes focused on functional objects, such as walls and vehicles, rather than material-specific categories like concrete or steel, thus restricting their applicability in construction [17,24,31].

Limitations highlight a significant gap in contemporary research. Current datasets and segmentation methods do not effectively support accurate material identification in construction settings. Section 1 outlines the objective of the systematic review. It seeks to fill the gap by analyzing existing approaches, assessing their effectiveness, and pinpointing opportunities for future advancements in material-level point cloud segmentation.

Objective of the Systematic Review

The systematic review identifies, compares, and analyzes various algorithms that use data-fusion segmentation, focusing on their effectiveness in segmenting construction materials such as concrete and steel. The review aims to demonstrate how combining multispectral and multimodal point cloud techniques with multiwavelength LiDAR data significantly enhances the accuracy of material distinction. Furthermore, the review examines the role of attention mechanisms and fusion-based network designs in enhancing segmentation performance and assesses their potential for material-level classification beyond construction. Included are their significance in environmental monitoring, infrastructure evaluation, and construction planning. Three research questions were formulated using the Setting, Perspective, Intervention, Comparison, and Evaluation (SPICE) methodology to meet the objectives of the review and to establish a transparent analysis framework. The investigation was systematically organized to focus on data fusion techniques and to compare various segmentation models for material classification.

SPICE provides a structured approach for describing a study’s context, goals, and assessment criteria. The Setting defines the study’s location, which includes two scenarios: (I) a construction site, representing physical space, and (II) a point cloud, symbolizing digital space. The Perspective outlines two key study elements: the point cloud database used for data generation and the segmentation algorithms examined from previous research. The Intervention details the actions taken, including the application of segmentation algorithms and the use of multispectral images.

The comparison section entails evaluating how current research aligns with existing studies. A consistent methodology will be applied in both scenarios, focusing on comparisons of established methods. In the Evaluation, the expected outcomes center on accuracy and efficiency metrics, particularly related to constructing and processing the point cloud.

Based on the input criteria established in Table 1 and following the SPICE framework, three key research questions were formulated. The three questions were designed to guide the systematic review process, focusing on identifying recent advances, methodologies, and challenges in real-time material level segmentation.

- To what extent do point-cloud segmentation algorithms that incorporate multispectral imagery exceed traditional geometry-based methods or single-sensor techniques in classifying concrete and steel within complex construction environments, particularly in terms of their reliability and performance metrics?

- How can multispectral point cloud segmentation algorithms facilitate real-time differentiation of structural materials while supporting construction progress tracking and quality control processes in geometric representations of dynamic construction site environments?

- What are the limitations of existing public geometric datasets for training and evaluating multispectral point cloud segmentation models in construction?

Table 1.

SPICE method used to formulate the research question.

Table 1.

SPICE method used to formulate the research question.

| SPICE Element | Input | Scenario 1 | Scenario 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| S—Setting | Where does the study take place? | Construction sites | Point cloud environments |

| P—Perspective | Who or what is being studied? | Point cloud datasets derived from multispectral imagery | Segmentation algorithms |

| I—Intervention | What is being done? | Implementation of a segmentation algorithm | Use of multispectral image data |

| C—Comparison | What are you comparing it to? | Existing segmentation methods | Existing baseline models |

| E—Evaluation | What are the expected outcomes? | Accuracy and computational efficiency | Accuracy and computational efficiency |

The main contributions of the paper are as follows.

- We identify and review available datasets used in segmentation studies and highlight the lack of construction-specific training data for deep learning models.

- We compare segmentation methods and metrics to evaluate the effectiveness of data fusion techniques over geometry-only baselines.

- We provide key challenges and future directions, including the need for domain-adaptive models and real-site datasets to improve material classification performance in construction environments.

2. Methods

We employ the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA)-guided systematic review approach to ensure transparency, reproducibility, and methodological rigor in identifying, screening, and selecting relevant literature. The PRISMA framework was chosen for its standardized and auditable process for systematic reviews. Using PRISMA Checklist shown in Supplementary Material, we synthesized heterogeneous research across the fields of computer vision, remote sensing, and construction engineering. The formulation of research questions used the SPICE framework, encompassing Setting, Perspective, Intervention, Comparison, and Evaluation. The Patient, Intervention, Comparison, and Outcome (PICO) framework was deemed inappropriate for studies focused on engineering and technology. The SPICE framework facilitates a structured analysis of technical systems, making it well-suited for research on material-level point cloud segmentation in construction environments.

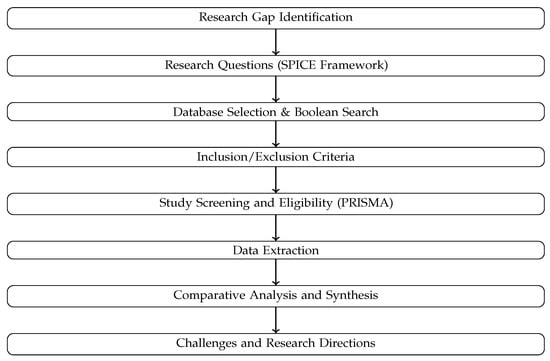

A comparative analytical framework was adopted to synthesize the selected studies. The framework enables systematic comparison of various segmentation algorithms, data modalities, datasets, evaluation metrics, and reported limitations. The execution of a meta-analysis was deemed unfeasible due to the heterogeneity identified among the reviewed studies. Variability in sensing configurations, dataset composition, segmentation granularity, and evaluation protocols would hinder the aggregation of results to a level that is statistically meaningful. Consequently, a qualitative and quantitative comparative synthesis was employed to identify trends in methodology, performance ranges, challenges, and research gaps. The overall methodological scheme of this study is illustrated in Figure 2, which summarizes the workflow from research gap identification and question formulation to data extraction, synthesis, and interpretation.

Figure 2.

Methodological framework of the systematic review, illustrating the PRISMA-guided workflow combined with the SPICE analytical framework and comparative synthesis approach.

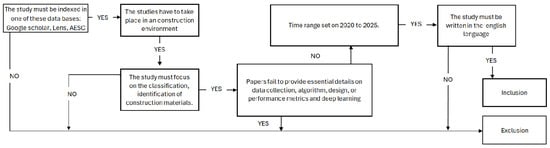

2.1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The inclusion and exclusion criteria for paper selection are depicted in Figure 3. The process establishes the parameters that decide a study’s appropriateness for this review. The criteria include the main databases in which the articles should be indexed, namely Google Scholar, The Lens, and the ASCE Library.

Figure 3.

Inclusion and Exclusion criteria.

The studies need to be conducted in an external setting, such as a construction site, with particular attention to classifying or identifying construction materials.

In addition, the chosen studies must include information on data collection methods, algorithms utilized, design or performance metrics, and the implementation of deep learning techniques. Articles should be published within the period from 2020 to 2025, and all studies must be composed in English.

2.2. Search Engine Strategy

After defining the research questions, a query string was formulated using the key investigation terms and the Boolean operators AND and OR, as presented in Table 2. The main keywords used included construction, materials, point cloud, multispectral imaging, classifications, algorithm, and reliability. Consequently, a Boolean formula was derived from these variations to form the comprehensive search query for the databases used in the study.

Table 2.

Search dimensions and Boolean query structure used for the literature review.

Conducting the query involves using three primary databases: Google Scholar, The Lens, and ASCE (American Society of Civil Engineers). Google Scholar was used as a multidisciplinary search engine to access academic publications, including articles on point cloud processing, material classification, and computer vision in construction.

The lens database was chosen for its wide-ranging coverage of scientific publications across multiple disciplines. Its thorough indexing is crucial for monitoring developments in point-cloud segmentation and multispectral imaging within the construction sector. By providing structured metadata and citation analysis, the platform helps identify research trends and key contributors, enabling a systematic assessment of developments in multisensor data fusion relevant to Construction 4.0.

ASCE Library was selected for its focused, specialized content in civil engineering, highlighting several significant papers on topics such as construction site monitoring, material analysis, and the integration of innovative technologies, including point cloud segmentation.

Data fusion is the process of combining information from multiple sensing sources—for example, different types of remote sensing data—to improve the accuracy of object recognition and segmentation. Its use has grown rapidly as modern sensors have made data collection much easier. As a result, combining data from various sources is now common in fields like computer vision and remote sensing, where it plays an important role in tasks such as object segmentation and identification.

2.3. Selection and Data Collection Process

The original data set included 123 entries. Titles and abstracts were reviewed to generate summaries that outline the problem context, data type, and intended task.

We evaluated whether the research focused on point cloud segmentation rather than related areas such as detection or 2D image analysis. We evaluated whether the goal was to identify construction materials in detail, distinguishing between concrete and steel rather than merely classifying generic categories. Studies that met these criteria were advanced for further evaluation on available performance metrics.

After identifying the candidate metrics, we assessed the consistency of their definitions and units across different articles to ensure a responsible comparison of the results. The process included verifying that widely used indicators, such as overall precision, mean intersection-over-union, or per-class F1/IoU, were calculated using similar protocols and labeling schemas, or that the authors provided sufficient detail to allow translation between similar formulations.

Research manuscripts were excluded from the review process if they did not provide sufficient detail in their explanations or if the definitions of their metrics were not easily comparable with those of other studies. Rigorous criteria ensure that only well-defined and adequately described research is considered for inclusion.

Following the detailed alignment process, 30 studies were identified as meeting all the specified criteria. Each of these studies was thoroughly examined, and relevant data on their methodologies, datasets used, training configurations, baseline comparisons, and results were extracted.

A thorough evaluation enabled us to pinpoint ongoing and persistent challenges frequently encountered in the research field. In addition, it allowed us to outline specific directions for future investigation.

2.4. Synthesis Methods

During full-text screening, each eligible paper was classified along eight dimensions to aid integration into the synthesis and highlight challenges in the field. Dimensions included sensing modality, task granularity, setting, comparators, domain shift, runtime/computer reporting, dataset characteristics, and reporting quality.

Studies were included if they focused on classifying concrete or steel using multispectral or multimodal segmentation techniques and required a baseline using geometry alone or a single sensor evaluated with consistent data protocols.

Performance comparisons were based on metrics like Overall Accuracy (OA), Mean Intersection over Union (mIoU), and per-class F1 or IoU scores to assess model effectiveness. Robustness evaluations compared model performance under standard versus modified conditions, including fog, rain, and night, to assess generalization beyond the training environment.

Synthesis for Research Question 2 focused on boundary and class imbalance, assessing studies that used boundary-aware metrics to improve segmentation precision at material interfaces and examining performance across specific classes, particularly those with underrepresented materials. The methodology highlighted class disparities and demonstrated how architectures could mitigate reductions in accuracy for infrequent elements.

Research Question 3 assessed the reporting and reproducibility of the dataset in studies, emphasizing the importance of datasets with clear annotations and comprehensive segmentation methods. Studies noted limitations in transferability across sensors, locations, or environments, revealing deficiencies in standardized datasets for material-aware segmentation and the need for transparent reporting to enhance reproducibility and comparisons between studies.

A structured extraction matrix was developed to standardize the reporting and allow valid cross-study comparisons. Each study included bibliographic details such as study identification number, publication year, and location. The extraction also recorded the study scope, including the site type and targeted materials, as well as the sensing configuration, detailed modalities, spectral bands, and resolution.

The risk of bias was evaluated using qualitative methods, focusing on the sufficiency of credible details in each publication to support its claims. For individual studies, documented results were reviewed to ensure availability at the material level, with explicit, consistent metric definitions and a transparent assessment protocol. This process required verifying the data partitioning methodology, distinguishing between the tuning and testing phases, and executing external or cross-site validation procedures.

3. Research Results

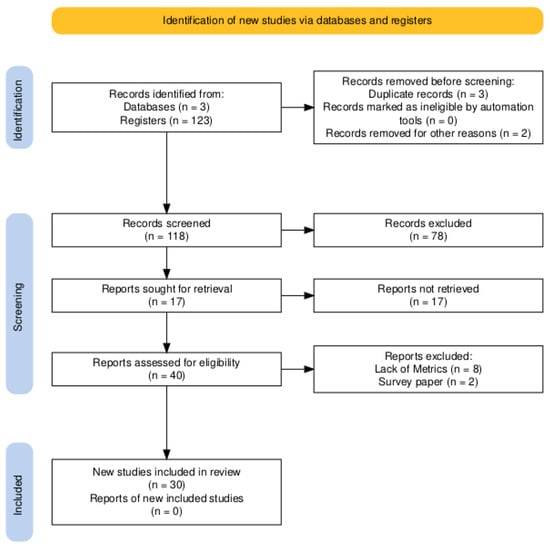

As shown in Figure 4, once the inclusion and exclusion criteria were established, we compiled a total of 123 records: 82 from Google Scholar, 33 from The Lens, and 8 from AESC. During the screening phase, we removed duplicate records and any entries that did not meet our criteria. Next, we excluded articles that did not focus on point cloud segmentation or classification. Finally, we identified 17 papers for which the full text was unavailable. Despite retrieval efforts, these 17 documents could not be obtained.

Figure 4.

PRISMA Workflow.

Studies examine limitations of ground segmentation models and propose a ‘patchwork’ strategy with adaptive parameter tuning to mitigate partial under-segmentation. They present new modeling concepts and improved performance in ground extraction. However, the lack of ground-only scores and material-specific metrics limits the comparability with our results.

We retained 40 documents after grouping by metrics, methodologies, and research types, excluding 10 articles: eight used specific metrics, and two were relevant reviews. These reviews focused on applications of point cloud data in specific domains rather than on surveys of point cloud-based deep learning segmentation. Then, 30 documents were employed for comparative analysis of methodologies, challenges, and opportunities. The excluded articles focus on shape reconstructions, object recognition, and BIM integration.

We present the results of our research methodology and compare the selected articles in terms of their approaches, findings, challenges, and identified opportunities. Table 3 provides a comparative analysis of state-of-the-art multisensor, multispectral point cloud segmentation methods. Although much progress has been made in the use of multimodal data, there are significantly fewer methods capable of classifying construction materials such as concrete or steel.

Table 3.

Comparison of segmentation and classification models for multispectral and point cloud datasets.

Our analysis demonstrates the role of multispectral features, particularly those obtained with multiwavelength LiDAR, in enhancing segmentation performance. Consistent with the findings of SE-PointNET++ [24] and FR-GCNet [26], the results indicate that incorporating spectral data significantly enhances the ability to distinguish between objects with similar geometric characteristics. This underscores the constraints of geometry-based approaches in construction environments and emphasizes the need to use spectral information to classify materials.

Domain adaptation and minority class recognition pose major challenges. The research from [28] shows that the model struggles with difficult datasets that feature fog, rain, and snow. Steel often represents only a small portion of the materials visible to the camera, leading to the omission or misclassification of other classes, which hampers effective class balancing at the prediction level and boundary refinement.

The review emphasizes the lack of domain-specific datasets, noting that publicly available ones primarily focus on urban transportation. Crucial material-level labels are missing for tracking construction site materials, underscoring the need for a dataset that supports domain generalization in object detection methods and the scarcity of material-level annotation datasets.

3.1. Data Fusion-Review

Data fusion integrates information from multiple sensing sources, including remote sensing technologies, to enhance object recognition and segmentation performance. The increasing adoption of data fusion approaches is linked to advances in sensing technologies, which facilitate the efficient acquisition of heterogeneous data. The combination of various data sources has become a common practice in computer vision and remote sensing, yielding significant improvements in the accuracy of object segmentation and identification tasks.

Urban and outdoor environments particularly benefit from data fusion, given that individual sensing modalities have inherent limitations. LiDAR provides detailed geometric information along with intensity and echo attributes, whereas High Spatial Resolution Imagery (HSRI) offers rich spectral characteristics but faces challenges from occlusions and illumination effects. The integration of these complementary data sources addresses these limitations, leading to enhanced building extraction, increased automation, and improved classification workflow robustness. Table 4 summarizes and classifies the data fusion strategies identified in the reviewed studies, categorizing them by fusion level and type.

Table 4.

Classification of data fusion levels and fusion types across the reviewed studies.

Multi-source remote sensing data fusion can be categorized into three distinct groups based on the stage or abstraction level at which the fusion occurs. Early fusion occurs at the pixel level during the raw data stage, before any processing. Early-stage fusion operates on multiple raw inputs, such as various images of the same region or different spectral bands, which are merged directly into a unified dataset to improve data quality. Intermediate fusion occurs at the feature level, where features are extracted but the final decision-making has not yet occurred. For intermediate fusion, each sensor’s data is processed independently to extract features, including texture, shape, point-cloud geometry, and spectral signatures. The extracted features are then merged into a unified representation that balances the richness of raw data with computational efficiency, making it suitable for deep learning architectures. Late fusion involves conducting separate analyses for each data source before consolidating their results. Each dataset generates a distinct classification, detection, or segmentation, and a final decision rule integrates these outputs to form a single, consensus result. The late fusion approach offers significant flexibility and performs effectively when the sensors exhibit varying properties or resolutions.

3.2. Types of Data Fusion-Review

Table 4 outlines the types of data, sensor modalities, and feature representations that are integrated in the reviewed documents. The objective of the table is to elucidate the significance of data fusion. Multiple multispectral LiDAR wavelengths and raw point cloud attributes, such as XYZ coordinates, intensity, and echo information, are among the primary data types being fused. Each wavelength interacts uniquely with materials, and combining this data enhances the point cloud with spectral cues, thereby improving material discrimination. This data integration exemplifies an early type of data fusion. Another instance of data fusion involves combining LiDAR data with optical imagery, such as RGB, NIR, and HIS. The LiDAR point cloud provides coordinates through geo-registration, resulting in a point cloud augmented with spectral and color information. This enrichment contributes to defining the shape and appearance cues of the model, thereby aiding tasks such as building extraction, material recognition, and land cover classification. Depending on the specific workflow employed, this integration can occur at either a mid-level fusion or an early-stage fusion.

3.3. Why Fusion Helps Distinguish Materials

The fusion of data significantly enhances the detection and segmentation of materials, owing to the robustness afforded by the multi-dimensional feature vector. Image-based methods encounter challenges related to geometric ambiguities and shadow occlusions when relying exclusively on a single dataset. Data sets that contain only LiDAR information are limited by the absence of essential spectral cues, which complicates accurate classification of areas where objects exhibit similar geometric characteristics but differ in spectral content.

The process of data fusion mitigates the limitations inherent in each data set by merging accurate height and geometry from LiDAR with detailed spectral reflectance from imagery. The literature indicates that the polarimetric multispectral LiDAR system is among the most effective fusion methods for material recognition. The polarimetric multispectral LiDAR effectively disentangles the influences of material composition and surface roughness on reflectance measurements, thereby facilitating precise material identification.

Features derived from the unpolarized reflectance spectrum generated through polarimetric multispectral fusion serve as an efficient tool for material classification, as they are independent of surface roughness and rely solely on volume scattering, which is contingent on the material properties themselves. Experimental investigations of construction-related materials, such as plastics and various types of stone, demonstrate that the unpolarized reflectance spectrum achieves 100% cross-validation accuracy for material classification with higher-resolution configurations.

The fusion of multispectral LiDAR features with geometric information proves particularly effective in urban and construction-oriented environments where materials such as concrete, asphalt, and impervious surfaces exhibit comparable geometric characteristics. The integration of spectral data with elevation-derived products, such as digital surface models (DSMs), combined with vegetation indices like the normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI), has yielded impressive classification performance, achieving an overall accuracy of 93.82% using three-channel multispectral LiDAR intensities, DSM, and NDVI features.

The utilization of polarimetric fusion data is particularly advantageous for differentiating between visually or geometrically similar objects. For example, concrete surfaces and asphalt roads have analogous height profiles, while buildings may structurally resemble vegetation. The addition of spectral or material-specific attributes, whether obtained directly from multispectral LiDAR or indirectly from registered imagery, allows segmentation frameworks to achieve enhanced discrimination among these objects. The incorporation of material properties into the three-dimensional representation bolsters classification robustness, especially in environments where geometry alone leads to ambiguity.

3.4. Model Architectures and Techniques

The analysis conducted reveals trends in the evolution of segmentation model architectures. Notably, point-based deep learning models such as SE-PointNet++ [24] and FRGCNet [26] remain prominent in the literature. The methods generally incorporate attention mechanisms (e.g., squeeze-and-excitation (SE) blocks, feature reasoning module) into the model design to improve the model’s material sensitivity to the underlying point cloud.

Recent sparse voxel-based architectures, including Geometry-Aware Sparse Networks [47] (GASN) and EyeNet [30], aim to reduce memory and computational costs when processing large-scale point clouds.

In addition, recent works also propose hybrid feature fusion by aggregating spectral, geometric, and contextual features, as indicated in the multimodal fusion work in [38], which produces significantly better results than others for materials with highly correlated geometric features.

3.4.1. Point-Based Models and Attention Mechanisms

Point-based deep learning approaches function by independently processing each point, rather than converting the point cloud into image or voxel formats. SE-PointNet++ and FR-GCNet represent two significant models that utilize attention mechanisms. Attention mechanisms within these models enhance the network’s capacity to highlight prominent spectral and geometric features, which leads to improved classification accuracy for multispectral LiDAR data.

3.4.2. SE-PointNet++

The SE-PointNet++ architecture is an enhanced version of PointNet++ tailored for the classification of multispectral LiDAR point clouds. The architecture incorporates a Squeeze-and-Excitation Block, which facilitates channel-wise attention. During the squeeze phase, the network produces a global statistical descriptor for each feature channel. The excitation phase uses this descriptor to identify informative channels, then assigns them higher weights. The subsequent recalibration stage amplifies the notable feature channels while diminishing the impact of irrelevant or noisy channels. This methodology improves feature saliency, strengthens the distinction among materials with closely spaced spectral characteristics, and mitigates the influence of redundant or noisy channels commonly found in multispectral LiDAR datasets.

3.4.3. FR-GCNet

The FR-GCNet is a graph-based neural architecture that integrates local and global reasoning to enhance multispectral LiDAR classification. The Local Reasoning Unit, implemented via edge attention, operates within the framework of graph theory by focusing on the immediate vicinity of each data point. This unit constructs a local graph using k-nearest neighbors and learns edge features encoding the relationships between pairs of points. An attention mechanism applies higher weights to edges that effectively highlight significant local structures. The primary objective of this unit is to capture detailed shapes and surface variations that are essential for distinguishing materials with overlapping spectral characteristics.

The global reasoning module analyzes large-scale structural relationships across the entire point cloud, using spatial coordinates to model global context and interrelations among distant regions. This approach differentiates large objects or materials that share similar local geometries but differ in spatial configuration. Its goal is to provide high-level contextual information that complements the local attention unit.

Both SE-PointNet++ and FR-GCNet demonstrate how attention mechanisms can make point-based segmentation models material-aware by suppressing irrelevant spectral channels while highlighting spatial structures useful for classification through the fusion of geometric and multispectral cues—something traditional PointNet-style models cannot do effectively. These methods also show a clear trend: attention mechanisms are becoming more critical in multispectral LiDAR material classification, as they help steer the model toward the most informative signals.

3.4.4. Sparse Voxel Architectures

Recent three-dimensional segmentation models employ sparse voxel architectures to decrease computational and memory demands while preserving geometric fidelity. The models GASN and EyeNet exemplify this approach, demonstrating that efficiency can be attained without compromising accuracy.

3.4.5. Geometry-Aware Sparse Networks (GASN)

Geometry-Aware Sparse Networks (GASN) provide an innovative method for efficient point cloud processing by leveraging the sparsity of large-scale 3D datasets. GASN avoids the reliance on dense voxel grids or computationally intensive point-based operations. Instead, GASN operates directly on a single sparse voxel representation, resulting in a significant reduction in computational requirements while preserving detailed geometric information.

The architecture includes a Sparse Feature Encoder (SFE) that implements sparse convolutions only at locations where points are present. A Sparse Geometry Feature Enhancement (SGFE) module supplements GASN by enriching feature extraction through the combination of multi-scale sparse projections and an attentive scale selection strategy. GASN also integrates Deep Sparse Supervision (DSS), which improves training efficiency by directly supervising intermediate layers with minimal memory usage. The collective functionality of these components enables GASN to achieve state-of-the-art performance with significantly lower memory consumption and faster processing times compared to most point-based or dense voxel-based techniques. GASN demonstrates its effectiveness in handling large and unstructured outdoor environments.

3.4.6. EyeNet

EyeNet is a point cloud segmentation network inspired by the human visual system that incorporates both foveal and peripheral vision. The multi-scale input strategy employed by EyeNet specifically addresses the complexities of dense, expansive outdoor point clouds. This strategy incorporates a high point density at the center of the scene while maintaining a lower density in the periphery. The configuration of this input strategy facilitates the model’s ability to focus on local details while incorporating global context, without excessive GPU memory consumption.

Consequently, EyeNet processes a significantly reduced data volume, utilizing nearly 60% fewer points than fixed-number sampling methods, such as RandLA-Net, while still achieving comparable segmentation accuracy. The efficient memory usage and scalability of EyeNet make it well-suited to real-world applications requiring extensive spatial coverage and constrained resources, such as mapping with UAVs or conducting long-range LiDAR surveys.

The development of contemporary 3D segmentation frameworks demonstrates a notable shift toward designs focused on efficiency while effectively addressing the significant scale and irregular structure of real-world point clouds. Models such as GASN and EyeNet illustrate the effectiveness of leveraging sparsity, multi-scale reasoning, and specific attention mechanisms to markedly reduce computational requirements without sacrificing accuracy. The avoidance of unnecessary dense processing, paired with an emphasis on meaningful geometric or contextual information, enables these architectures to achieve faster runtimes, lower memory consumption, and improved scalability in comparison to traditional point-based methods.

The ability of these models to operate efficiently with fewer points or sparse voxel representations makes them particularly suitable for large outdoor environments such as construction sites, where the volumes of UAV and LiDAR data are exceptionally high. These strategies collectively highlight advances in the field toward practical and efficient solutions that maintain robustness in complex, unstructured environments.

3.4.7. Hybrid and Multimodal Feature Fusion

Segmentation approaches currently rely heavily on integrating multiple forms of information, including spectral, geometric, and contextual data, to generate more detailed and precise object representations. The combination of multiple modalities or feature domains is especially effective when materials share similar shapes or geometries, making classification based solely on geometric cues difficult.

3.4.8. Geometric and Contextual Feature Fusion

Recent advancements in segmentation models incorporate geometric and contextual features to improve the understanding of complex point cloud environments. FR-GCNet exemplifies this approach by integrating local structural information acquired through Edge Convolution with global contextual features that explicitly describe relationships across the entire scene. The dual reasoning strategy implemented in FR-GCNet enables the model to better comprehend fine-grained geometry and large-scale spatial organization.

LDE-Net also contributes to this field by introducing a Local–Global Feature Extraction (LGFE) module, which aggregates detailed local features and higher-level contextual cues using distance metrics derived from spatial coordinates, color values, and learned feature representations. Furthermore, LDE-Net includes a Local Feature Aggregation Classifier (LFAC) to enhance classification performance by refining object boundaries using information from neighboring points. The findings from these methods suggest that integrating geometric structure and contextual understanding can significantly improve segmentation accuracy when materials or objects share similar shapes or occupy overlapping spatial patterns.

3.4.9. Spectral and Multimodal Aggregation

Spectral and multimodal aggregation represents a powerful methodology for classifying point clouds, particularly when geometric information alone is insufficient for materials with similar shapes. Recent studies have demonstrated the usefulness of integrating multi-wavelength spectral information with three-dimensional spatial information, particularly for urban and natural scenes. In multispectral LiDAR research, the combination of geometric features, such as height or spatial coordinates, with spectral measurements, including RGB, near-infrared (NIR), raw LiDAR intensities, and vegetation indices such as the normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI), is common. This integration enables models to exploit material-specific patterns of spectral reflectance and structural properties, thereby providing a comprehensive representation of each object. Even a basic multi-layer perceptron (MLP) network utilizing this multimodal feature set achieves over 97% overall accuracy in urban mapping tasks, highlighting the efficacy of spectral fusion. Multimodal aggregation enhances the model’s ability to express the diversity of material characteristics, resulting in more robust and discriminative classification than can be achieved using only geometric or spectral information.

3.4.10. Material Sensitivity Through Multistream Fusion

Material sensitivity is significantly enhanced by multistream fusion techniques, which combine hyperspectral, RGB, and 3D point cloud data to identify subtle variations often missed by single-modality approaches. These multistream models utilize distinct processing pathways for each data modality, which enables the extraction of complementary information: geometric structure is derived from the point cloud, color and texture are extracted from RGB imagery, and fine-grained spectral signatures are captured from hyperspectral data. The incorporation of channel attention modules is a critical aspect of this methodology, often implemented using 3D CNNs or EdgeConv within the hyperspectral branch, enabling the network to prioritize the most informative wavelengths while mitigating irrelevant spectral noise. The focus on salient spectral features within multistream architectures leads to a marked improvement in the ability to differentiate materials that share similar geometric shapes or visual properties but display unique reflectance characteristics. This capability is especially crucial in applications such as mineral or material classification, where nuanced spectral signals are vital for distinguishing between closely related categories. Consequently, multistream fusion establishes a robust framework for achieving high material sensitivity, effectively addressing the constraints imposed by monochromatic LiDAR or solely geometric methods.

The three primary fusion strategies consist of geometric and contextual integration, spectral and multimodal aggregation, and material-sensitive multistream architectures. These strategies collectively indicate a clear trend in contemporary point cloud segmentation research: effective classification increasingly requires integrating diverse and complementary feature domains. Geometric-contextual fusion significantly improves spatial understanding by integrating precise local structures with broader scene-level relationships, thereby enhancing boundary clarity and structural coherence. Spectral and multimodal aggregation further enriches representational depth by incorporating wavelength-dependent reflectance patterns and multisensor cues that geometry alone cannot capture, thereby enabling models to handle materials that share similar shapes but exhibit different spectral signatures. Multistream fusion architectures subsequently enhance material sensitivity by allowing each modality—hyperspectral cubes, RGB images, and 3D point clouds—to contribute specialized information via dedicated processing paths and attention mechanisms. These three approaches collectively emphasize that no single modality or feature type can suffice on its own; instead, the most robust and accurate segmentation results emerge from merging geometric, spectral, and contextual information into a unified, holistic representation of the scene. This understanding increasingly supports the use of hybrid and multimodal methods to ensure dependable performance in complex real-world settings, particularly in material-level classification, infrastructure monitoring, and construction site analysis.

3.5. Multispectral and Multimodal Data

One of the findings in the reviewed studies is the role of multispectral and multimodal data in improving material-level segmentation:

- SE-PointNet++ [24] demonstrated that incorporating Titan airborne multispectral LiDAR (532 nm, 1064 nm, 1550 nm) data improved overall precision from about 88% to 91.16% and significantly enhanced material discrimination.

- FR-GCNet [26] further reinforced this finding by achieving an mIoU of 65.78% in multispectral datasets, outperforming traditional geometry-only networks.

- The study [27] demonstrated that, using multispectral polarimetric LiDAR features (specifically Runpol and Rpol reflectance indices), a material classification accuracy of almost 100% could be achieved in controlled laboratory experiments, suggesting the powerful role of polarization information in distinguishing between concrete and steel.

Evidence indicates that employing multispectral and multimodal data substantially improves material-level segmentation performance. Combining spectral and polarimetric data allows improved differentiation between materials with similar geometries, such as concrete and steel. Methods incorporating spectral diversity and polarization outperformed geometry-only models, underscoring their importance for achieving greater accuracy in classifying construction materials.

3.6. Challenges Identified in Current Methods

Technical challenges identified in the reviewed literature are outlined in Table 5. Each issue is supported by evidence from systematic analysis, demonstrating ongoing problems that hinder the development of robust, material-specific segmentation models for construction site environments.

Table 5.

Challenges identified in current methods.

Advances in multispectral and multimodal point-cloud segmentation face persistent challenges in construction settings. Issues such as domain shift-induced performance decline, data sparsity, noise, and imprecise boundary delineation hinder reliability.

Although models such as SE-PointNet++ and FR-GCNet improve robustness to spectral data, they struggle to adapt in real time to changes in data quality. Imbalance in minority classes, particularly for materials such as steel and rebar, affects accuracy, underscoring the need for balanced training and adaptive loss functions.

Additionally, data sets such as SemanticKITTI and Semantic3D lack material-specific annotations, thereby limiting reproducibility. Domain-adaptive architectures and enhanced dataset design play a crucial role in ensuring consistent material recognition within construction environments.

3.7. Dataset Coverage and Gaps

The datasets employed for training and testing are inadequate for the segmentation of construction-specific materials. Indoor data sets such as S3DIS and ScanNet have high point density and include surface segmentation of walls, floors, and furniture. However, they often lack exposed structural elements, such as bare concrete and steel, which are vital for accurate construction segmentation and assessment.

Outdoor LiDAR benchmarks such as SemanticKITTI, Semantic3D, and SensatUrban face challenges in large open environments and varied ecological conditions, including occlusions and changes in illumination. However, these datasets often lack detailed annotations, as their labeling schemes prioritize general categories (e.g., building, ground, vehicle) without specifying details, limiting their use for material classification tasks such as differentiating concrete slabs from steel frames.

A limited number of datasets, such as the Titan MSLiDAR Urban dataset, include multispectral LiDAR intensity data (532, 1064, and 1550 nm) that help to distinguish materials by their spectral properties. However, these datasets lack material-level ground-truth annotations and cannot differentiate between concrete, steel, asphalt, and other categories. This results in a shortage of publicly available domain-labeled datasets needed to develop and evaluate material-aware segmentation models in the construction sector. In addition, they do not provide sufficient diversity in natural light, weather, sensor types, and construction site contexts.

4. Discussion

The analysis examines the findings of our systematic review, highlighting study-level metrics and their implications for construction sites. Consistent patterns are observed: effective spectral–geometric fusion, reduced robustness amid domain shifts, strong boundary performance in traditional architectures, deep learning minority effects, and the influence of methodological designs on overfitting.

Enhanced comparability is due to thorough reporting practices. Limitations in the existing literature include a focus on overall accuracy, variable intersection-over-union thresholds, inadequate material-specific metrics, and insufficient evaluation of domain shift, which affect the strength and clarity of the evidence in construction contexts.

In alignment with the discussion, Table 6 synthesizes and contrasts the segmentation approaches analyzed in this study. Also, underscores the relative performance, robustness, and practical applicability of each approach within construction environments. The trends identified in the Results section and the preceding architectural and data-related considerations inform the systematic distinctions among geometry-only methods, multispectral methods, multimodal approaches, and hybrid techniques. The comparative perspective provided by this table clarifies that integrating spectral information with multimodal data consistently enhances material-level discrimination, particularly for concrete and steel. This enhancement, however, reveals trade-offs related to dataset availability, sensitivity to domain shifts, and deployment complexity.

Table 6.

Comparison of representative approaches for material segmentation and classification in construction-related 3D data.

4.1. Performance and Architectural Trends

Spectral and geometric fusion techniques outperform alternative methods in the material-level segmentation of construction point clouds.

Multi-wavelength returns are particularly useful for distinguishing between concrete and steel when geometries are similar or texture information is lacking.

An advantage becomes evident in analyses that focus on per-class performance metrics (F1/IoU scores) for concrete and steel, rather than overall accuracy.

Effective segmentation networks primarily use point-based approaches and integrate attention or feature-reasoning modules, such as squeeze-and-excitation or mid/late-fusion transformers, which allow for adaptive reweighting of spectral-geometric features and improved boundary detection.

Additionally, hybrid multi-stage fusion methods—combining early and mid/late fusion—often surpass single-stage methods in resilience to sparse or noisy point clouds, which is crucial for accurately identifying thin steel components and object contacts, where under-segmentation can occur due to coarse segmentation granularity.

4.2. Robustness, Evaluation Practice, and Dataset Constraints

Advantages of fusion depend on the context, and performance frequently diminishes due to acquisition changes such as time of day, weather, location, or sensor alterations.

Achieving robustness requires strategies such as data blending, pretraining methods, and external validation rather than being effortless.

Comparisons can be biased, often relying on overall accuracy or on inconsistent definitions of Intersection over Union (IoU), complicating accurate assessment of minority classes such as steel.

Although standardized reporting shows that fused methodologies outperform geometry-based baselines in material classification, steel identification remains less effective than concrete identification, as it lacks measures to mitigate boundary effects and rebalance.

Datasets have prioritized functional over material labels, limiting the training signal and robustness evaluation. Fair comparisons and clearer insights would be enabled by a dataset that addresses domain shifts, focuses on material labels, and includes challenging conditions.

4.3. Deployment Implications

Conventional evaluation metrics may prove insufficient for on-site applications, such as tracking project progress and ensuring quality assurance/quality control (QA/QC). Techniques that demonstrate strong effectiveness yet reach a performance ceiling in terms of high mean Intersection over Union (mIoU) within reasonable inference budgets are considered appropriate. There is broad agreement on the parameters that should be established to guide pivotal decisions, underscoring the importance of publicly fixing dataset splits or mandating the execution of code or weights that achieve favorable balances between effort and accuracy based on less visible configurations.

Experiments based on nonpublic validation datasets and using a best-of-N methodology, with reported averages and standard deviations, often lack relevance and appeal and fail to yield definitive results. The examination reveals that spectral-geometric fusion is a reliable approach for material-level segmentation due to its practicality. However, attaining high mIoU figures can sometimes be misleading. Crucial factors include maintaining robust performance under specific conditions, ensuring reproducibility through accessible code, weights, and datasets with predetermined splits, minimizing overfitting, and preventing intermixing of dataset views. This journey begins with a setup featuring closed-sea boundaries and concludes with closed-sea line reporting. The procedure is completed with the implementation of transitions away from obsolescence, the establishment of standardized viewing protocols, and the sharing of computational resources, all accompanied by reporting modest yet dependable research efforts that avoid misleading improvements in mIoU.

4.4. Classification Difficulties

The reviewed literature indicates a consistent pattern in which specific classes exhibit analogous geometric properties, spectral signatures, or sparse spatial representations, particularly when semantic segmentation accuracy decreases. Roads and grass or buildings and trees frequently exhibit confusion due to similar elevation profiles, nearly identical spatial distributions, or spectral clutter. Objects that present overlapping geometric forms, such as boards and doors or tables and chairs, pose challenges for differentiation when relying exclusively on spatial coordinates or limited RGB data.

Boundary regions become significant sources of error due to points between classes that display mixed features, resulting in considerably lower mean Intersection over Union (mIoU) values compared to inner object regions. The misclassification of minority classes and thin linear structures, including vehicles, traffic signs, cables, and power lines, arises from class imbalance, sparsity, and insufficient geometric distinctiveness. This specific issue is notably common with metallic structural elements, which often appear as slender features that may be misidentified as nearby vegetation or other structural components. In contrast, large planar elements typically associated with concrete consistently achieve high segmentation accuracy.

4.5. Summary of Techniques to Overcome the Challenges

Recent research has increasingly utilized hybrid and multimodal fusion strategies that integrate geometric, spectral, and contextual information to address classification challenges. Researchers have developed spectral augmentation techniques that incorporate RGB, NIR, NDVI, or two-dimensional material classification maps, providing essential material cues that complement geometric features and help distinguish classes with similar shapes. Multi-stream architectures have been designed to process various modalities—such as XYZ, RGB, hyperspectral, or intensity data—independently before fusion, thereby preserving the distinct characteristics of each feature space and preventing early feature dilution.

Attention mechanisms, such as Squeeze-and-Excitation blocks, combined with data augmentation and class-weighted loss functions, address class imbalance, thereby enhancing robustness for thin or sparse structures. Boundary-focused approaches, including Contrastive Boundary Learning and Local Feature Aggregation, enhance discrimination at object edges, where misclassification is frequent. Additional geometric refinements, including concave–convex analysis in supervoxel segmentation, further improve boundary accuracy by correcting artificial cross-boundary errors. Collectively, these methods illustrate that achieving reliable segmentation performance—especially for challenging materials or slender metallic structures—necessitates integrating rich multimodal representations and leveraging both global context and precise local structure.

5. Conclusions and Recommendations for Future Research

The examination concludes that integrating multimodal and multispectral data with geometric information provides a reliable strategy for segmenting materials at the granular level in point clouds derived from construction sites. Advanced models exhibit marked improvements in robustness when differentiating between similar materials, such as concrete and steel. This enhanced accuracy is especially evident in regions where distinctive textures are minimal or where dense architectures predominate, in contrast to traditional methods that rely primarily on geometric data.

The performance evaluation of these models requires the application of material-specific metrics, including the per-class F1 score and per-class Intersection over Union (IoU). Sole reliance on Overall Accuracy (OA) risks inaccurately representing the performance of geometry-only methods. Minor performance enhancements often correlate with a decrease in robustness under real-world conditions. Typical failures arise in challenging scenarios across various sites and sensors, and such issues remain largely unaddressed unless explicitly included in design and evaluation considerations.

Recent architectural advancements that combine point-based frameworks with attention mechanisms and feature reasoning, as well as multi-stage fusion techniques, demonstrate potential to improve boundary delineation and reduce under-segmentation for minor classes. However, reported performance metrics are often sensitive to the data augmentation strategies employed during training, potentially affecting their relevance under unforeseen evaluation conditions. Therefore, point-based frameworks, attention mechanisms, multi-stage fusion, and feature reasoning components are supplemented by models incorporating alternative components.

The inherent difficulty of making comparisons across studies underscores the challenges of establishing high levels of confidence. Inadequate reporting practices, a lack of standardized metric definitions, and insufficient comprehensive evaluations addressing domain variations further complicate this situation. The emphasis should not rest on achieving high reproducibility rates; rather, the focus must be on the precise application of evidence relevant to actual construction contexts. Key factors that contribute to reproducibility include the accessibility of model weights and executable code, thorough curation of benchmark datasets, and clearly defined training and test splits. Although contemporary technologies, such as cloud-based execution of weights and code, automated methods for generating reproducible datasets, and secure subsets for benchmarking, present opportunities to produce irrefutable evidence, they do not alter the fundamental principles underlying reproducibility.

The first conclusion indicates that integrating multispectral and multimodal data with geometric point-cloud representations consistently yields a superior framework for material-level segmentation compared to geometry-only approaches. Spectral–geometric fusion significantly enhances the ability to discriminate between materials with similar geometries, such as concrete and steel, particularly in environments deficient in texture cues.

The second conclusion highlights the sensitivity of segmentation performance to evaluation design. Metrics like overall accuracy may obscure inadequate material-level performance, particularly for minority classes such as steel. The reliance on per-class metrics, including per-class IoU and F1 scores, is crucial for scientifically valid comparisons and for accurately assessing material segmentation capabilities.

The third conclusion emphasizes that current publicly available point-cloud datasets fall short in advancing material-aware segmentation within construction contexts. The lack of construction-specific, material-labeled datasets and standardized evaluation protocols hinders reproducibility, generalization, and comparability across studies, thereby exposing a significant research gap.

The fourth conclusion states that, from an engineering perspective, multispectral and multimodal segmentation methods possess strong potential to improve construction progress monitoring and quality assurance workflows by facilitating remote, geometry-preserving inspections of construction sites. These methodologies minimize the necessity for manual site visits and subjective assessments.

The fifth conclusion notes that, despite their promise, existing models exhibit reduced robustness in real-world conditions, due to domain shifts caused by weather, sensor variations, and site heterogeneity. For effective practical deployment, engineering solutions should prioritize robustness, computational efficiency, and consistency across operational conditions, rather than merely achieving peak performance on controlled benchmarks.

The sixth conclusion suggests that future applications in construction engineering stand to benefit from domain-adaptive segmentation frameworks, standardized material-level datasets, and reproducible evaluation practices. Such advancements are essential for transitioning multispectral segmentation methods from experimental studies to dependable tools for real-time progress monitoring and digital-twin-driven construction management.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/buildings16010140/s1, PRISMA 2020 Checklist. Reference [54] is cited in the Supplementary Materials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.M.L.G., O.O.V.V. and V.G.C.S.; methodology, E.M.L.G., O.O.V.V., V.G.C.S., H.d.J.O.D. and J.H.S.A.; validation, E.M.L.G., O.O.V.V., V.G.C.S. and H.d.J.O.D.; formal analysis, J.H.S.A.; investigation, E.M.L.G.; writing—original draft preparation, E.M.L.G., J.H.S.A., O.O.V.V. and V.G.C.S.; writing—review and editing, O.O.V.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by SECIHTI.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

Enrique Luna wants to thank SECIHTI for the scholarship support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sawhney, A.; Irizarry, J. A Proposed Framework for Construction 4.0 Based on a Review of Literature. EPiC Ser. Built Environ. 2020, 1, 301–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusof, H.; Ahmad, A.; Abdullah, T.; Mohammed, A. Historical Building Inspection Using the Unmanned Aerial Vehicle. Int. J. Sustain. Constr. Eng. Technol. 2020, 11, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mader, D.; Blaskow, R.; Weller, C. Potential of UAV-Based laser scanner and multispectral camera data in building inspection. Int. Arch. Photogramm. 2016, XLI-B1, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, T.; Li, Y.; Ren, M.; Li, J. Pixel-level crack segmentation and quantification enabled by multi-modality cross-fusion of RGB and depth images. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 487, 141961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Z.; Li, Y.; Fu, H.; Tian, J.; Zhou, Y.; Chin, C.L.; Chau Khun, M. Research on Concrete Crack and Depression Detection Method Based on Multi-Level Defect Fusion Segmentation Network. Buildings 2025, 15, 1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ham, Y.; Han, K.; Lin, J.; Golparvar-Fard, M. Visual monitoring of civil infraestructure systems via camera-equipped Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs): A review of related works. Vis. Eng. 2016, 4, 2–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, N.; Izhar, M.A.; Najam, F.A. Construction Monitoring and reporting using drones and unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs). In Proceedings of the Tenth International Conference on Construction, New Orleans, LA, USA, 2–4 April 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Stalowska, P.; Suchocki, C.; Rutkowska, M. Crack detection in building walls based on geometric radiometric point cloud information. Autom. Constr. 2021, 134, 104065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Jennesse, M.; Holley, P. Utilizing Light Unmanned Aerial Vehicles for the Inspection of Curtain Walls: A Case Study. In Proceedings of the Construction Research Congres 2016, San Juan, PR, USA, 31 May–2 June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Jalinoos, F.; Amjadian, M.; Angrawal, K.; Brooks, C.; Banach, D. Experimental Evaluation of Unmanned Aerial System for Measuring Bridge Movement. Bridge Eng. 2019, 25, 3390–3416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- d’Oleire Oltmanns, S.; Marzoff, I.; Peter, K.D.; Ries, J.B. Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) for Monitoring Soil Erosion in Morocco. Remote Sens. 2012, 4, 3390–3416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwood, W.; Lynch, P.; Zekkos, D. Applications of UAVs in Civil Infrastructure. J. Infrastruct. Syst. 2019, 25, 04019002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nooralishahi, P.; Ibarra-Castanedo, C.; Deane, S.; Lopez, F.; Pant, S.; Genest, M.; Avdelidis, N.; Maldague, X. Drone-Based Non-Destructive Inspection of Industrial Sites: A Review and Case Studies. Adv. Civ. Appl. Unmanned Aircr. Syst. 2021, 5, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janet, X.; Livesey, P.; Wang, J.; Huang, S.; He, X.; Zhang, C. Deconstruction waste management through 3d reconstruction and bim: A case study. Vis. Eng. 2017, 5, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sieber, S.; Teizer, J. Mobile 3D mapping for surveying earthwork projects using an Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) System. Autom. Constr. 2014, 41, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, M.I.; Melo, R.R.; Costa, D.B. Contribution of UAS Monitoring to Safety Planning and Control. In Proceedings of the 29th Annual Conference of the International Group for Lean Construction, Lima, Peru, 14–17 July 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Teizer, J.; Pradhananga, N.; Eastman, C. Workforce location tracking to model visualize and analyze workspace requirements in building information models for construction safety planning. Autom. Constr. 2015, 60, 74–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, E.; Seo, J.; Wacker, J. UAV-aided bridge inspection protocol through machine learning with improved visibility images. Autom. Constr. 2022, 197, 116791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daif, H.; Marzouk, M. Point cloud classification and part segmentation of steel structure elements. Neural Comput. Appl. 2024, 37, 4387–4407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauch, L.; Braml, T. Semantic Point Cloud Segmentation with Deep-Learning-Based Approaches for the Construction Industry: A Survey. Artif. Intell. Appl. Civ. Eng. 2023, 13, 9146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Justo, A.; Lamas, D.; Sánchez, A.; Soilán, M.; Riveiro, B. Generating IFC-compliant models and structural graphs of truss bridges from dense point clouds. Ind. Inf. Integr. 2023, 35, 100483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaei, K.; Arashpour, M.; Asadi, E.; Feng, H.; Reza, S.; Bazli, M. Automatic compliance inspection and monitoring of building structural members using multi-temporal point clouds. Build. Eng. 2023, 72, 106570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Lali, Y.; Chen, X.; Lou, Y.; Wang, C.; Yang, H.; Gao, X.; Han, H. Towards big data driven construction industry. Autom. Constr. 2023, 149, 104786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, Z.; Guan, H.; Zhao, P.; Li, D.; Yu, Y.; Zang, Y.; Wang, H.; Li, J. Multispectral LiDAR Point Cloud Classification Using SE-PointNet++. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 2516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, D.; Lan, R.; Wang, L.; Ren, X. Pyramid Architecture for Multi-Scale Processing in Point Cloud Segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 19–20 June 2022; pp. 17263–17273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.; Guan, H.; Li, D.; Yu, Y.; Wang, H.; Gao, K.; Junior, J.M.; Li, J. Airborne multispectral LiDAR point cloud classification with a feature Reasoning-based graph convolution network. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2021, 105, 102634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Salido-Monzú, D.; Wieser, A. Classification of material and surface roughness using polarimetric multispectral LiDAR. Opt. Eng. 2023, 62, 114104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, A.; Huang, J.; Xuan, W.; Ren, R.; Liu, K.; Guan, D.; El Saddik, A.; Lu, S.; Xing, E. 3D Semantic Segmentation in the Wild: Learning Generalized Models for Adverse-Condition Point Clouds. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 9382–9392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Zhang, J.; Chen, Z.; Zhao, S.; Tao, D. UniMix: Towards Domain Adaptive and Generalizable LiDAR Semantic Segmentation in Adverse Weather. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.05145. [Google Scholar]

- Yoo, S.; Jeong, Y.; Jameela, M.; Sohn, G. Human Vision Based 3D Point Cloud Semantic Segmentation of Large-Scale Outdoor Scenes. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 6577–6586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandio, J.; Riveiro, B.; Soilán, M.; Arias, P. Point cloud semantic segmentation of complex railway environments using deep learning. Autom. Constr. 2022, 141, 104425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichler, M.; Taher, J.; Manninen, P.; Kaartinen, H.; Hyyppä, J.; Kukko, A. Semantic segmentation of raw multispectral laser scanning data from urban environments with deep neural networks. ISPRS Open J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2024, 12, 100061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Gu, Y.; Li, X.; Zhang, X.; Liu, B. A Normalized Spatial–Spectral Supervoxel Segmentation Method for Multispectral Point Cloud Data. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 5704311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; An, Y.; Cui, Y.; Dong, H. Semantic Segmentation of 3D Point Clouds in Outdoor Environments Based on Local Dual-Enhancement. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Zhan, Y.; Chen, Z.; Yu, B.; Tao, D. Contrastive Boundary Learning for Point Cloud Segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 19–20 June 2022; pp. 8479–8489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Yang, B.; Wang, B.; Li, B. GrowSP: Unsupervised Semantic Segmentation of 3D Point Clouds. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 17619–17629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oinonen, O.; Ruoppa, L.; Taher, J.; Lehtomäki, M.; Matikainen, L.; Karila, K.; Hakala, T.; Kukko, A.; Kaartinen, H.; Hyyppä, J. Unsupervised semantic segmentation of urban high-density multispectral point clouds. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.18520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizaldy, A.; Afifi, A.; Ghamisi, P.; Gloaguen, R. Improving Mineral Classification Using Multimodal Hyperspectral Point Cloud Data and Multi-Stream Neural Network. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 2336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahiri, Z.; Laefer, D.F.; Kurz, T.; Buckley, S.; Gowen, A. A comparison of ground-based hyperspectral imaging and red-edge multispectral imaging for façade material classification. Autom. Constr. 2022, 136, 104164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, P.; Ma, Z.; Fei, M.; Liu, W.; Guo, G.; Wang, M. A Multiscale Multi-Feature Deep Learning Model for Airborne Point-Cloud Semantic Segmentation. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 11801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.; Kim, S.; Kim, S. Automatic detection and classification process for concrete defects in deteriorating buildings based on image data. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2024, 24, 2773–2787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, W.; Zhu, C.; Wang, D.; Chen, Z. Reverse Bim Mapping of Spatial Geometric Envelope Anomalies Based on Infrared Point Clouds. SSRN. 2024. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4928594 (accessed on 24 December 2025).

- Guo, M.; Zhao, Y.; Tang, X.; Guo, K.; Shi, Y.; H, L. Intelligent Extraction of Surface Cracks on LNG Outer Tanks Based on Close-Range Image Point Clouds and Infrared Imagery. J. Nondestruct. Eval. 2023, 43, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Yang, F.; Feng, X.; Dong, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Min, G.; Li, J. Multiview Learning for Impervious Surface Mapping Using High-Resolution Multispectral Imagery and LiDAR Data. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2023, 16, 7866–7881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, B.; Yang, J.; Song, S.; Shi, S.; Gong, W.; Wang, A.; Du, L. Target Classification of Similar Spatial Characteristics in Complex Urban Areas by Using Multispectral LiDAR. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.; Sun, G.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, A.; Ren, J.; Jia, X.; Li, F. Three-dimensional singular spectrum analysis for precise land cover classification from UAV-borne hyperspectral benchmark datasets. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2023, 203, 115–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, M.; Wan, R.; Xu, S.; Cao, T.; Chen, Q. Efficient Point Cloud Segmentation with Geometry-Aware Sparse Networks. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2022, Tel Aviv, Israel, 23–27 October 2022; pp. 196–212. [Google Scholar]

- Abumosallam, Y.M.G.M. Multispectral LiDAR-Imagery Data Fusion and Multilevel Classification of LiDAR Point Clouds for Urban Features Extraction. Ph.D. Thesis, Ryerson University, Toronto, ON, Canada, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Savino, P.; Tondolo, F. Civil infrastructure defect assessment using pixel-wise segmentation based on deep learning. J. Civ. Struct. Health Monit. 2023, 13, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]