Abstract

Improving the energy efficiency of Australia’s ageing housing stock is critical to achieving national decarbonisation and climate resilience goals. Although houses built prior to the introduction of national energy efficiency regulations in the 1990s are commonly assumed to be thermally inefficient, empirical evidence for their performance under Australian climatic conditions remains limited, particularly for prevalent pre-war construction typologies. This study addresses this gap by examining the thermal comfort and energy demand of a representative double-brick house built in the 1930s in Adelaide, Australia. A combined methodology was adopted, integrating long-term environmental monitoring, occupant responses, and building performance simulations conducted in two stages. The first stage evaluated the existing building’s thermal and energy performance to establish a calibrated baseline, while the second stage applied parametric optimisation analysis to assess potential retrofit strategies. Baseline results indicate that the case-study dwelling exhibits strong passive cooling performance in summer, challenging the prevailing assumption that older Australian houses are inherently thermally inefficient. Building on this calibrated baseline, parametric optimisation of 467 retrofit configurations was undertaken and benchmarked against the Australian Nationwide House Energy Rating Scheme (NatHERS). The results show that a combined strategy of increased insulation, reduced infiltration, upgraded glazing, and optimised external shading can reduce total heating and cooling loads by up to 78% compared to the original condition, achieving energy ratings of up to 8.5 NatHERS Stars. The findings demonstrate a transferable workflow that links empirical performance assessment with simulation-based optimisation for evaluating retrofit options in older housing typologies. For pre-war double-brick houses in warm-temperate climates, the results indicate that prioritising airtightness and glazing upgrades offers an effective and feasible retrofit pathway, supporting informed decision-making for designers, owners, and policymakers.

1. Introduction

Improving the energy efficiency of older houses in Australia is crucial to address climate change challenges. The building sector accounts for 39% of global energy-related carbon emissions [1]. In Australia, buildings contribute to one-fifth of total emissions and housing contributes almost half of this share [2,3,4]. Enhancing performance of the existing housing stock is therefore not only an environmental imperative but also a technical and policy challenge to achieving the national net-zero target by 2050.

The Australian Nationwide House Energy Rating Scheme (NatHERS) was introduced in 1993 and adopted nationwide in 2004, as a critical framework for assessing the energy performance of new housing in Australia [5]. NatHERS calculates the potential total heating and cooling load per unit of floor area within a house’s conditioned zones and compares it with the star band criteria that vary based on the building’s location [6]. To comply with Building Codes, new buildings must achieve a NatHERS star rating of 7 or higher, with separate limits for heating and cooling loads [7].

A large proportion of Australia’s housing stock is ageing. Over 95% of residential buildings were constructed before the introduction of energy efficiency regulations, and more than 71% were built before 1990 [8]. Rajagopalan et al. [9] estimate that most of the approximately 10 million existing homes across Australia demonstrate poor energy performance. The majority of these houses with an average NatHERS rating of only 2.2 stars [10], and in South Australia specifically, older houses have an average NatHERS rating of just 1.8 stars [11]. Several studies reported that indoor thermal conditions in such buildings were frequently inadequate, especially during summer and winter extremes [12,13,14], and are associated with adverse health outcomes [15,16,17]. Thus, improving the energy performance of existing housing stock represents a critical opportunity for improving thermal comfort, reducing emissions, and enhancing resilience. Retrofitting has emerged as a key strategy for enhancing the energy efficiency of existing buildings, reducing greenhouse gas emissions, and achieving decarbonisation [18,19]. Internationally, numerous studies have assessed retrofit measures across diverse climates and building types, ranging from historic dwellings in Europe to contemporary houses in North America and the Middle East [20,21,22,23,24,25,26]. While these studies demonstrate the potential of passive and active strategies, their direct transferability to Australia is limited by differences in building typologies, construction practices, and regulatory frameworks.

Building performance simulation has become a widely adopted method to evaluate retrofit strategies and assess energy and comfort outcomes under different scenarios. Recent advances in parametric and optimisation modelling further enhance this capability by allowing efficient exploration of multiple design alternatives, identifying trade-offs, and tailoring solutions to specific housing typologies [27,28,29,30,31,32,33]. However, despite these methodological developments, there remains a significant gap in applying such approaches to Australia’s interwar residential housing, that is, more specifically a common typology of double-brick housing in warm-temperate climates. Moreover, the environmental design logic embedded in these pre-war houses, such as passive cooling, cross-ventilation and thermal mass utilisation, has received limited scholarly attention despite its potential to inform sustainable retrofitting today. This gap limits understanding of retrofit opportunities for one of Australia’s most common and energy inefficient housing types.

From a methodological perspective, recent studies have highlighted the limitations of relying solely on steady-state thermal indicators when assessing the performance of building envelopes. For example, Guattari et al. [34] demonstrated that the dynamic thermal behaviour of walls cannot be adequately characterised by thermal resistance alone, emphasising the importance of non-steady-state modelling approaches for capturing thermal inertia effects in existing buildings. Similarly, Cusenza et al. [35] integrated dynamic building energy simulation within broader performance assessment frameworks, reinforcing the value of calibrated, simulation-based methodologies for evaluating operational energy demand. Together, these studies provide methodological support for the dynamic, calibrated simulation-based approach adopted in the present study.

This study evaluates the thermal and energy performance of a representative pre-war double-brick house in Adelaide, South Australia, and investigates retrofit strategies that enhance thermal comfort while reducing operational heating and cooling loads. A dynamic simulation model of the 1930s dwelling was developed and validated using field monitoring and calibration. Parametric and optimisation analyses were then applied to test retrofit strategies, including airtightness, insulation, and window upgrades, and to compare outcomes against NatHERS. The objective is to generate practical retrofit pathways that are not only energy efficient but also technically feasible within the local construction context. By establishing a performance-based retrofit priority hierarchy grounded in local construction practices and climatic conditions, this study provides actionable retrofit pathways and contributes new insights into the sustainable transformation of Australia’s ageing housing stock.

To guide this investigation, the following research questions are addressed:

- How does a representative pre-war double-brick house in South Australia perform in terms of thermal comfort and heating and cooling energy demand under current climatic conditions?

- To what extent can a calibrated building performance simulation reproduce the observed thermal behaviour of the case-study dwelling and support systematic evaluation of retrofit options?

- Which combinations of envelope-related retrofit measures are most effective in reducing heating and cooling loads while achieving higher NatHERS ratings for pre-war double-brick houses in warm-temperate climates in Australia?

2. Methods

This study was conducted in three phases (as shown in Figure 1). In the first phase, general data of the study house, including building measurements and construction characteristics were collected. Environmental variables, including indoor dry-bulb temperature and relative humidity, were measured through a 24-month indoor environmental monitoring study, and occupancy patterns were documented based on occupant responses to interviews, later translated into simulation operation schedules. In situ testing (e.g., blower door tests, infrared thermography, or U-value measurements) was not feasible in the tenanted dwelling due to access limitations and the intrusive nature of such measurements, which would require disruption to occupants and partial disassembly of existing building elements. Envelope properties and infiltration rates were therefore initially constrained to credible ranges for comparable housing typologies and later refined during model calibration.

Figure 1.

Overview of the methodological workflow.

In the second phase, building performance simulations were carried out using a digital model developed in DesignBuilder (version 7.0.2.006) and EnergyPlus (version 22.2.0). Indoor dry-bulb temperature data obtained from the 24-month indoor environmental monitoring study were used to calibrate the model. Subsequent simulations assessed indoor temperatures under free-running conditions, as well as estimated annual heating and cooling loads when HVAC (Heating, Ventilation and Air Conditioning) was enabled.

When HVAC was enabled, space heating and cooling were modelled using an idealised system in DesignBuilder (version 7.0.2.006), having unlimited capacity to allow it to meet any heating or cooling demand. Heating and cooling systems were assumed to use electricity only, serve the main living area and the main bedroom, and represent a reverse-cycle split air-conditioning system (without fresh air intake), reflecting typical conditioned spaces in South Australian residential dwellings. This HVAC configuration was applied consistently across all simulation scenarios to ensure comparability of results.

In the final phase, a parametric analysis was conducted to evaluate the effectiveness of individual retrofit strategies in reducing heating and cooling loads, with parameter ranges selected to span Australian National Construction Code (NCC) Climate Zone 5 minima and commonly specified upgrade levels. Subsequently, a genetic algorithm optimisation analysis was performed to explore multi-variable combinations and identify Pareto-optimal designs that jointly minimise heating and cooling loads. The results were also compared against NatHERS. An economic evaluation was not undertaken in this study as installed costs vary with heritage constraints and contractor rates.

2.1. Base Model Characteristics

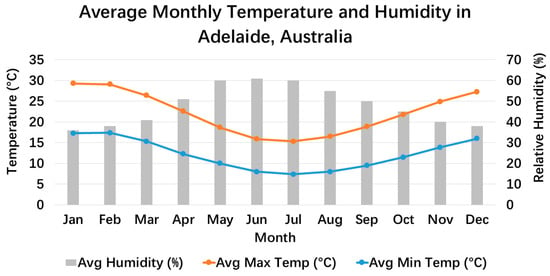

The study house is located in Prospect, in the Adelaide Metropolitan Area in the State of South Australia (as shown in Figure 2). The location has a warm-temperate climate [36], classified as Köppen–Geiger Csa, with four distinct seasons. January and February are typically the hottest months, with average maximum temperatures ranging from 29 °C to 35 °C, and they are often accompanied by heatwaves extending into March, occasionally reaching temperatures exceeding 40 °C. In contrast, June, July and August bring cooler temperatures, with average maximum temperatures ranging from 15 °C to 16 °C, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 2.

Building location in Prospect, South Australia [37]. The red arrow indicates the location of the selected case study house within the Adelaide metropolitan area.

Figure 3.

Average monthly temperature and relative humidity in Adelaide, Australia, based on data from the Australian Bureau of Meteorology (BoM) Kent Town weather station [38].

The selected building in this paper is a single-storey semi-detached house constructed in the 1930s. It features double-brick external walls with a sandstone faced front, a corrugated galvanised iron roof, timber sash windows and pine floorboards. This dwelling typology (single-storey, semi-detached, double-brick with timber frame sliding sash windows, all features that typify Adelaide’s early suburban housing stock) was particularly popular in the early 1930s in Adelaide [39], and dwellings of this type remain relatively common today. Importantly, the house is situated within the City of Prospect’s Suburban Neighbourhood 2 Character Area (PrC2) [40], which has been formally designated in local planning policy as representing late 19th and early 20th century residential character. This provides official recognition that the selected house is representative of a broader and historically significant archetype. More broadly, semi-detached houses accounted for 100,639 dwellings across South Australia in the 2021 Census [41], indicating that the building examined here represents one strand within a housing form that continues to be present in the residential landscape. Accordingly, the selected building represents a prevalent archetype in the area today.

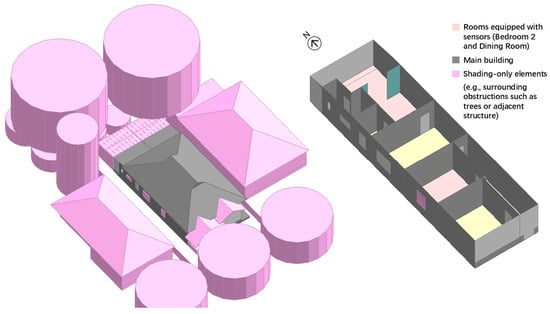

The house sits on a narrow suburban block with a front garden and consists of a sequential layout running south to north, with two bedrooms, a living room, a kitchen, and a dining area, as shown in Figure 4. The kitchen accommodates most appliances in the house. The rear dining room and outdoor terrace were incorporated into the house later. Although the ceiling had been retrofitted prior to this study, key envelope elements (solid double-brick walls, timber windows, and an uninsulated suspended floor) has maintained its original state. The base case, therefore, was considered to still reflect the typical fabric conditions of houses from this era. Key characteristics such as building orientation, layout, dimensions, openings, shading devices, and building construction details were transferred into the DesignBuilder 3D model, as shown in Figure 5. Surrounding vegetation and adjacent buildings were explicitly modelled as shading-only objects in DesignBuilder 3D model. Thus, their influence on solar gains was accounted for during calibration and scenario analyses. The specifications for the base model characteristics are detailed in Table 1. Where in situ measurements were unavailable, thermal properties were initialised from the DesignBuilder/ASHRAE libraries and cross-checked against published values for similar constructions, providing literature-based anchors for the estimated parameter ranges. The building construction materials and their corresponding U-values W/(m2K) and R-values (m2K)/W were obtained from DesignBuilder’s material database, which is based on ASHRAE and international material standards.

Figure 4.

Building front view (left) and floor plan (right).

Figure 5.

DesignBuilder 3D model of the selected building.

Table 1.

Building construction materials and corresponding U-values W/(m2K) and R-values (m2K)/W.

2.2. Indoor Environmental Monitoring

Data collection occurred between January 2021 and December 2022. Data loggers, which recorded indoor dry-bulb temperature and relative humidity every 2 h, were installed in the main living area (where the household occupants spent most of their time during the day) and in the main sleeping area (where the occupants slept most nights). Data loggers were positioned to allow a single measurement point, at approximately 1.0 m above the floor, away from direct solar radiation and away from heating sources such as light bulbs, or other electronic equipment [42]. Data collection met the requirements of a Class-II field study and the requirements of ASHRAE Standard 55–2020 [43]. The recorded indoor temperature data were subsequently used to calibrate the digital model developed in DesignBuilder (version 7.0.2.006). Indoor air temperature and relative humidity were monitored using Monnit ALTA wireless sensors. Details of the monitoring equipment, sensor types, accuracy, and measurement ranges are summarised in Table 2.

Table 2.

Indoor environmental monitoring equipment and specifications.

2.3. Occupancy Schedule and Heating and Cooling Temperature Set Points

Occupancy patterns were documented through occupant responses to an interview. For the study period, the house was occupied by two adults (one male and one female, both in their 40 s). Temperature set points for heating and cooling varied throughout the monitoring study and were not monitored. To ensure transparent and policy relevant comparisons across scenarios, therefore, in this study, a cooling set point assumption of 28 °C was calculated using the adaptive comfort model from ASHRAE 55-2020 [43] based on the prevailing outdoor temperature of 24.3 °C (the average temperature in February, the hottest month in Prospect/Adelaide). A heating set point of 18 °C was implemented according to NatHERS [44], which is widely used as a convention in Australia. Table 3 shows the occupancy schedules and temperature set points inputs for the monitored rooms. Occupancy schedules, temperature set points, and assumptions about equipment and appliances were maintained constant between the base model and the various simulation scenarios to enable consistency when comparing results.

Table 3.

Simulation occupancy schedules and temperature set points.

2.4. Calibration

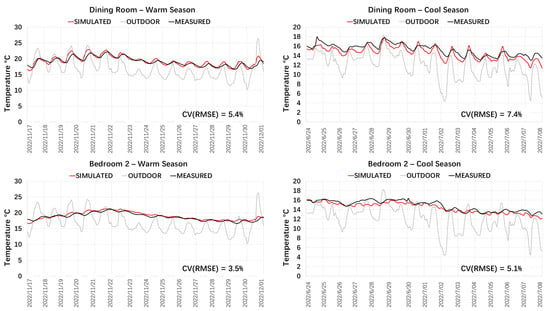

After the initial DesignBuilder model was developed (as shown in Figure 5), the model underwent a calibration process to ensure that the simulated indoor temperatures, calculated using the EnergyPlus (version 22.2.0) dynamic simulation engine, without heating and cooling, closely matched the actual indoor temperatures recorded over at least 14 consecutive days in both warm and cool months. The periods of 24 June to 8 July 2022 and 17 November to 1 December 2022 were identified as having no active air conditioning or heating in the study house.

For the calibration process, the simulated indoor temperatures of Bedroom 2 and the Dining Room were compared with the measured data. This comparison was undertaken as both these rooms serve as essential spaces, with Bedroom 2 representing the main sleeping area and the Dining Room representing the main living area, highlighted in red in Figure 4 and Figure 5. Weather data for the year of 2022 were acquired from the nearby Australian Bureau of Meteorology weather station.

Three types of input parameters were considered during calibration. Inputs were grouped as ‘basic’ (from house survey), ‘measured’ (from environmental monitoring and occupant responses) and ‘estimated’ (parameters only determined by estimation, namely the thickness of envelope material layers, the materials’ thermal properties, and the building infiltration rates). ‘Basic’ and ‘measured’ inputs were fixed and only ‘estimated’ parameters were varied within plausible bounds, following common practice for temperature-based calibration [45].

To assess the simulation model’s accuracy, the difference between the measured and simulated data was calculated using the coefficient of variation (CV) of the Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE). A CV (RMSE) value of less than 10% was considered an acceptable result for calibrating the digital model [46,47]. Using an iterative process of adjusting input variables (i.e., construction materials thermal properties, air infiltration rates and shading and neighbouring elements) in the model, following the manual methodology by Možina et al. [48], the final calibrated model showed a CV (RMSE) of 5.1% for Bedroom 2 and 7.4% for the Dining Room during the cool season, and a CV (RMSE) of 3.5% for Bedroom 2 and 5.4% for the Dining Room during the warm season, as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Calibration results for warm season (left) and cold season (right), for dining room and bedroom 2.

2.5. Parametric Optimisation Simulation

To achieve the study’s objectives, the parametric and optimisation modules in DesignBuilder were used. The parametric analysis feature allowed the researchers to run multiple simulations, creating design curves that show how changes in building configurations affect energy performance. For instance, heating and cooling loads were analysed across a range of infiltration rates, to assess their impact on energy demand. To further reduce heating and cooling loads, the optimisation module used Genetic Algorithms (GAs) [49] to systematically explore various combinations of retrofit strategies.

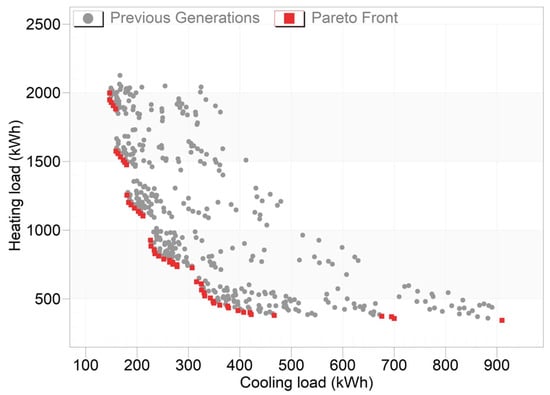

The optimisation analysis focused on two main objectives: (1) reducing heating and cooling loads, and (2) minimising operational carbon emissions throughout the year. Operational CO2 emissions were calculated based on the simulated annual heating and cooling energy demand for each optimisation scenario. Annual energy consumption was converted to CO2 emissions using a grid-based electricity emission factor representative of the South Australian electricity supply. The analysis considered operational emissions associated with space conditioning only and excluded embodied carbon related to construction materials or retrofit implementation. CO2 emissions are reported in kg CO2/year. By testing different combinations of design variables, the model identified the most effective retrofit combinations. The results were plotted on a graph that displayed heating loads on one axis and cooling loads on the other. Optimal designs were identified along the “Pareto front” at the bottom-left edge of the data point cloud, representing configurations that achieved the best balance of minimised heating and cooling loads, as later shown in Figure 7 in Section 2.5.

Figure 7.

Optimisation analysis results, minimise cooling and heating load.

2.6. Retrofit Strategies and Design Variables Tested

The energy efficiency of older houses varies widely depending on factors such as climate, building materials, construction techniques, and occupant behaviour. However, in many cases, older houses suffer from poor insulation, air leakage, outdated windows, and inefficient heating and cooling systems, all of which lead to higher energy use [50]. In Australia, older houses are especially impacted by poor insulation, which has a major impact on their thermal performance and energy consumption. According to a report on energy efficiency retrofits in Victoria, most Australian houses built before 1990 lack proper insulation in their external wall cavities, making external walls a major source of heat loss during winter and heat gain on hot summer days, significantly affecting energy efficiency and indoor comfort [51].

The selected building analysed in this study, for example, did not meet the thermal resistance requirements set by the National Construction Code (NCC) standards for Climate Zone 5 (Adelaide, South Australia) [36]. The external wall, constructed with two layers of brick (without cavity) and a 10 mm thick plasterboard layer, has a total R-value of 0.468 (m2K)/W, far below the NCC minimum requirement of R-2.8. Here, R-values (e.g., R-2.8) denote insulation levels, expressed as the letter R followed by the thermal resistance in (m2K)/W, where higher R-values indicate higher resistance to heat flow through the material. Notably, brick construction dominates Australia’s residential landscape, with an estimated 71% of dwellings in 1999 constructed using either double brick or brick veneer walls [52]. Brick construction was particularly common in Victorian and Federation-era homes, which continue to define the architectural fabric of many inner suburbs in cities such as Adelaide, Melbourne, and Sydney. Similarly, the internal floor, comprising a 25 mm thick hardboard layer, has a total R-value of 0.462 (m2K)/W, failing to meet the NCC minimum requirement of R-2.0. However, the ceiling, already recently upgraded with a 160 mm glass-fibre slab insulation, meets NCC standards. Generally, wall and floor insulation are installed during the construction phase, while ceiling insulation is more commonly retrofitted in South Australia. Consequently, the ceiling option was excluded from further analysis in this study due to its limited potential for further retrofitting and since it is more common to be already retrofitted.

Five retrofit variables to improve the thermal performance and energy efficiency of older Australian houses are investigated in this study. These strategies were considered realistic to be applied in existing homes and are frequently suggested in academic studies, by service providers and government entities as equally relevant [27,29,51,53,54,55]. The strategies, detailed in Table 4, include increasing the total R-value of external walls and internal floors, reducing infiltration rates to improve airtightness, upgrading window performance, and optimising external shading devices over windows. The above strategies were prioritised in lieu of implementing costly building modifications (such as rebuilding the entire space or house), to illustrate possible improvements through manageable alternatives. Window-to-wall ratio (WWR) or orientation variations were not tested, as they were considered unlikely in the case of existing buildings.

Table 4.

Retrofit variables and values tested.

As shown in Table 4, the five variables tested cover:

- (1)

- Total R-Value of external wall

Three insulation materials were chosen with 2 thick options, 100 mm and 200 mm. This accounts for a total of six external wall alternatives, with total external wall R-values ranging from 2.794 (m2K)/W to 7.611 (m2K)/W. The double brick and plasterboard layers remained the same in all alternatives. The lower bounds approximate NCC minimum fabric requirements for Climate Zone 5, whereas the upper bounds represent deep-retrofit levels commonly available in the local market.

- (2)

- Total R-Value of internal floor

Internal floor was evaluated using the same six configurations, varying the insulation without modifying the hardboard layer, with total internal floor R-values ranging from 2.788 (m2K)/W to 7.605 (m2K)/W. The lower bounds approximate NCC minimum fabric requirements for Climate Zone 5, whereas the upper bounds represent deep-retrofit levels commonly available in the local market.

- (3)

- Infiltration rate

Infiltration rates, in air changes per hour at 50 Pa (ACH50), were simulated using 5 alternatives: 25, 20, 15, 10, and 5. The five ACH50 levels span typical leakage measured in existing Australian housing through to ambitious but achievable retrofit targets.

- (4)

- Window glazing

In addition to the single-glazed clear glass window with a 3 mm thickness and timber frame (U-value = 5.894 W/(m2K)) used in the base model, the study evaluated the impact of using double-glazed clear glass with a 3 mm thickness, a 13 mm air gap, and a timber frame (U-value = 2.716 W/(m2K)), as well as triple-glazed clear glass with a 3 mm thickness, a 13 mm air gap, and a timber frame (U-value = 1.757 W/(m2K)). These window options represent a stepwise improvement from the original single glazing to commonly adopted double and triple glazing configurations in Australian residential retrofit practice. While higher-performance insulating glass units (IGUs), such as low-emissivity coatings with argon-filled cavities, can achieve substantially lower U-values and are commercially available in Australia, they were not adopted in this case study. This reflects prevailing retrofit practices in the mild South Australian climate, where such solutions remain less commonly implemented due to cost considerations and market uptake.

In addition to U-values, the Solar Heat Gain Coefficient (SHGC) was also considered to characterise solar heat transmission through glazing and its contribution to indoor heat gains, as shown in Table 4.

- (5)

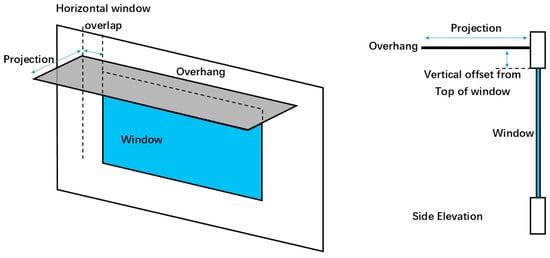

- External shading (projections as shown in Figure 8)

Figure 8. Local shading, external overhang diagram.

Figure 8. Local shading, external overhang diagram.

Five window shading configurations were tested on all windows: 0.00 m overhang (no shading), 0.25 m overhang, 0.50 m overhang, 0.75 m overhang, and 1.00 m overhang. Overhang depths bracket typical residential eave dimensions. These ranges allow regulatory compliance checks and practical feasibility to be assessed concurrently.

3. Results

3.1. Simulated Temperature Results for Base Case Model

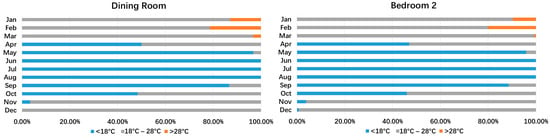

Table 5 illustrates the predicted percentage of time per year within, above and below the 18 °C to 28 °C range for Bedroom 2 and the Dining Room, where heating and cooling systems were not in use, in the base case model. The data shows a significant portion of the year with temperatures below 18 °C in both Bedroom 2 (48.49%) and the Dining Room (49.04%). The thermally comfortable range of 18–28 °C accounts for slightly less than half of the year in both spaces, with Bedroom 2 at 49.32% and the Dining Room at 47.95%. High temperatures above 28 °C are rare, occurring only 2.19% of the time in Bedroom 2 and 3.01% in the Dining Room.

Table 5.

Percentage of time within each temperature range, annually, in each room in the base case model.

Figure 9 provides a monthly breakdown of the percentage of time spent within each temperature range. During the winter months (June, July, and August), temperatures consistently remain below 18 °C, accounting for nearly all the time in both spaces. In spring (April and May) and autumn (September and October), a significant portion of time is also spent below 18 °C, although the percentage of time within the thermally comfortable range (18–28 °C) begins to increase. Summer months (December, January, and February) are predominantly characterised by temperatures within the thermally comfortable range, with rare instances of excessive heat, mainly observed in January and February, above 28 °C.

Figure 9.

Percentage of time (%) is within, below and above the 18 °C and 28 °C temperature range, monthly, in each room in the base case model.

3.2. Simulated Heating and Cooling Results for Base Case Model

Table 6 presents the simulated annual heating and cooling energy loads of the base case model. The heating demand is 3600.77 kWh (108.04 MJ/m2), significantly higher than the cooling demand of 165.59 kWh (4.97 MJ/m2). The combined total annual energy load for heating and cooling is 3766.36 kWh (113.00 MJ/m2). As shown in Table 7, under NCC standards [56], the heating load of 108.04 MJ/m2 exceeds the maximum permitted load of 67.0 MJ/m2. In contrast, the cooling load of 4.97 MJ/m2 remains well below the maximum permitted value of 52.0 MJ/m2.

Table 6.

Annual heating and cooling loads of the base case model in kWh.

Table 7.

Comparison between NCC (Part 3.12.0.1—Heating and Cooling Loads) [56] and the base case model heating and cooling loads in MJ per m2.

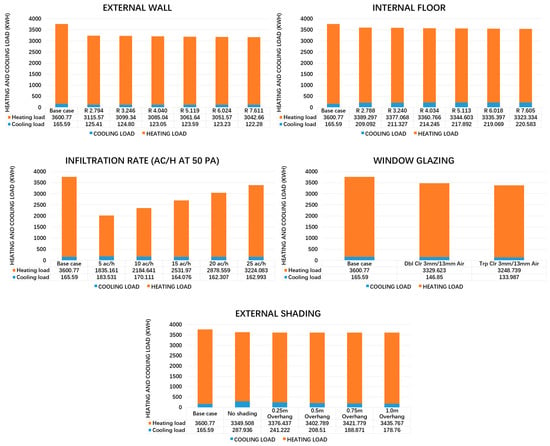

3.3. Parametric Analysis Results

Figure 10 summarises the results of the parametric analysis of the impact of the retrofitting strategies on the annual heating and cooling loads of the house.

Figure 10.

Parametric analysis heating and cooling loads results.

- (1)

- External wall

Six configurations of external walls were tested, with total R-values ranging from 2.794 (m2K)/W to 7.611 (m2K)/W. The simulation results indicate that improved thermal resistance of the external walls significantly reduces both heating and cooling loads across all scenarios. For cooling loads, a general decline is observed as total external wall R-values increase, with the greatest reduction (i.e., 26%) achieved in the total R value 7.611 (m2K)/W of external wall configuration. For heating loads, a steady and substantial reduction is evident as R-values increase. The total R value 7.611 (m2K)/W of external wall configuration achieved the greatest heating load reduction (i.e., 15%).

- (2)

- Internal floor

Internal floor insulation was assessed using the same six configurations, with total R-values ranging from 2.788 (m2K)/W to 7.605 (m2K)/W. The results indicate that adding internal floor insulation reduces heating loads while simultaneously increasing cooling loads. Heating loads decreased from 3389.30 kWh at the total R value 2.788 (m2K)/W of internal floor to 3323.33 kWh at the total R value 7.605 (m2K)/W of internal floor, while cooling loads increased from 209.09 kWh at the total R value 2.788 (m2K)/W of internal floor to 220.58 kWh at the total R value 7.605 (m2K)/W of internal floor. Compared to the base case, 3600.77 kWh heating and 165.59 kWh cooling, all tested configurations showed a reduction in heating loads but an increase in cooling loads. Despite this trade-off, total energy demand declined overall, ranging from 3598.39 kWh at the total R value 2.788 (m2K)/W of internal floor to 3543.92 kWh at the total R value 7.605 (m2K)/W of internal floor.

- (3)

- Infiltration rate

The impact of infiltration rates ranging from 5 air changes per hour at 50 Pa (ACH50) to 25 air changes per hour at 50 Pa (ACH50) was evaluated. Improved airtightness significantly reduced heating loads, while cooling loads displayed mixed behaviour. When 25 air changes per hour at 50 Pa (ACH50), cooling loads decreased from 165.59 kWh in the base case to 162.99 kWh, and heating loads dropped from 3600.77 kWh to 3224.08 kWh. Similarly, when 20 air changes per hour at 50 Pa (ACH50), cooling loads further decreased to 162.31 kWh, and heating loads were reduced to 2878.56 kWh. At a moderate infiltration rate of 15 air changes per hour at 50 Pa (ACH50), cooling loads increased slightly to 164.08 kWh but still lower than the base case, heating loads experienced a significant reduction, dropping to 2531.97 kWh. At lower infiltration rates, cooling loads begin to rise. At 10 air changes per hour at 50 Pa (ACH50), cooling loads increased to 170.11 kWh, while heating loads dropped to 2184.64 kWh. The lowest infiltration rate of 5 ach resulted in the highest cooling load, 183.53 kWh, but achieved the lowest heating load, 1835.16 kWh. Overall, total energy loads decreased significantly with reduced infiltration.

- (4)

- Window glazing

The comparison between double-clear and triple-clear glazing shows improved energy performance for both options compared to the original single-glazing. Cooling loads decreased from 165.59 kWh in the base case to 146.85 kWh with double-clear glazing and further to 133.99 kWh with triple-clear glazing. Similarly, heating loads were reduced from 3600.77 kWh to 3329.62 kWh for double-clear glazing and to 3248.74 kWh for triple-clear glazing.

- (5)

- External shading

Shading devices, specifically overhangs of varying sizes, were analysed. The analysis revealed a clear trade-off between cooling and heating loads as overhang length increases. Cooling demand rose significantly without shading, reaching 287.94 kWh, but progressively decreased as shading improved, dropping to 178.76 kWh with the largest overhang (1.0 m). Among the shading scenarios, the 1.0 m overhang achieved the lowest cooling load; however, it still fell short of the base case cooling load of 165.59 kWh. Conversely, heating demand increased with longer overhangs. Heating loads increased from 3349.51 kWh with no shading to 3435.77 kWh with a 1.0 m overhang. Despite this increase, all shading options resulted in lower heating loads compared to the base case scenario.

3.4. Optimisation Analysis Results

An optimisation analysis was used to explore the performance impacts and trade-offs of the retrofit variables defined in the methodology section, rather than to select variables. The results therefore illustrate how different combinations of these predefined parameters influence heating and cooling loads.

The optimisation converged at the 31st generation, at which point no further improvements in heating and cooling loads were identified. A total of 467 configurations were evaluated, as shown in Figure 7. The Pareto front (highlighted in red) identifies 51 optimal designs that simultaneously minimise both heating and cooling energy demands, while grey points represent solutions from earlier optimisation iterations.

Clear trade-offs between heating and cooling performance are observed across the Pareto-optimal solution set. Configurations with the lowest heating loads (approximately 200–400 kWh) are generally associated with higher cooling loads (approximately 400–900 kWh), whereas configurations with the lowest cooling loads (approximately 100–200 kWh) exhibit substantially higher heating demands (approximately 1000–2000 kWh). These results indicate that single-objective optimisation tends to shift energy demand between seasons rather than reducing total energy use.

Across the 51 Pareto-optimal designs, total annual heating and cooling loads range from 2367 kWh (approximately 71 MJ/m2) to 809 kWh (approximately 24 MJ/m2), representing reductions of 37% to 78% relative to the base case. These performance improvements correspond to NatHERS energy ratings between 6.5 and 8.5 stars, as defined by the Adelaide star band criteria, as shown in Table 8. The configuration with the lowest total energy demand achieves an annual load of 809 kWh, equivalent to a NatHERS rating of 8.5 stars. To support comparative interpretation, representative optimisation scenarios associated with minimum heating demand, minimum cooling demand, minimum operational CO2 emissions, and minimum total energy demand are summarised in Table 9.

Table 8.

Star band criteria for Adelaide. Reproduction from NatHERS [6].

Table 9.

Optimal designs—combinations of retrofit strategies.

4. Discussion

4.1. Insights on Simulated Temperature and Heating and Cooling Results for the Base Case

The simulated temperature results indicate that the current house faces significant challenges in achieving thermal comfort during winter, with nearly half of the time spent below 18 °C. These results support findings by Daniel et al. [57] that many older Australian households experience winter temperatures below recommended comfort thresholds, leading to dissatisfaction. The inadequacies in the building envelope, particularly poor insulation and air leakage, are key contributors to this discomfort. Previous studies have also shown that older houses in Australia, especially those built before 1990, often lack adequate insulation in external walls or rely on wall sarking, resulting in high heat loss during winter [51]. This study reinforces these findings, demonstrating a critical issue in older Australian houses.

In contrast, during summer, the house demonstrates strong passive cooling performance, with indoor temperatures exceeding 28 °C on less than 4% of occasions. This performance in summer can be attributed to good shading from surrounding trees as well as the house’s original design features, such as high ceilings, large shaded windows, and large room volumes, which enhance natural ventilation and shading, effectively combating extreme heat [58].

The selected house also demonstrated that heating accounted for most energy use, with a heating load that is significantly higher than the maximum permitted by NatHERS standards for new buildings. By contrast, cooling demand was minimal even compared to standards for new buildings, underscoring the effectiveness of passive cooling features in summer conditions. These results confirm that retrofitting older houses in South Australia should prioritise heating performance improvements rather than cooling interventions.

4.2. Insights on Parametric and Optimisation Retrofitting Analyses

The parametric and optimisation analyses highlight the relative effectiveness and practicality of different retrofit strategies for pre-war double-brick houses in South Australia. Improving airtightness proved to be the most effective retrofit measure for reducing energy loads in the selected house. Reducing infiltration rates to 5 air changes per hour at 50 Pa (ACH50) resulted in substantial energy savings, specifically a 46% reduction in the total energy load, highlighting the importance of airtightness in enhancing thermal performance. However, this level of airtightness is rarely achieved in Australian construction practice and may create risks of overheating and poor indoor air quality if not paired with mechanical ventilation. By contrast, reducing infiltration to 10 air changes per hour at 50 Pa (ACH50) provides a practical and achievable target, consistent with best-performing local benchmarks, while still delivering substantial energy savings. Notably, previous studies indicate that the average air change rate for newly constructed Australian buildings is around 15 air changes per hour at 50 Pa (ACH50), with 10 air changes per hour at 50 Pa (ACH50) representing a very well-sealed envelope [59]. Based on these, achieving an infiltration rate of 10 air changes per hour at 50 Pa (ACH50) offers a highly practical and efficient balance between thermal comfort and implementation feasibility [55].

External wall insulation also delivered significant reductions in both heating and cooling loads, delivering approximately a 16% reduction with a total R-value of 7.611 (m2K)/W. These results support findings by Bojić et al. [60] in Serbia, Morelli et al. [61] in Denmark, Walker et al. [62] in Ireland, Wang et al. [63] in China, and Felimban et al. [64] in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA), which demonstrated that upgrading wall insulation significantly enhances thermal performance and reduces energy consumption across diverse climatic conditions. In this study the total external wall R-value of 7.611 (m2K)/W was achieved using a 200 mm thick insulation material; however, the associated construction challenges, condensation risks, and summer overheating potential limit its widespread application. From a practical standpoint, insulation thicknesses of around 100 mm offer a more balanced solution, improving performance while remaining feasible to install.

Window upgrades demonstrated significant improvements as well, achieving up to a 10% reduction in total heating and cooling loads with the application of triple glazing, and 8% of double glazing. Similar results were found in studies by Dong et al. [27,28,29] and Simko et al. [65] in Australia, Amaral et al. [66] in Portugal and Giuffrida et al. [67] in Italy. While reducing window sizes could enhance thermal performance further, this approach was avoided to preserve occupant visual comfort and satisfaction and maintain access to natural light. On the other hand, double glazing performed nearly as well as triple glazing but with lower cost and complexity, making it a preferable retrofit pathway in this case. Importantly, highly insulated glazing, when combined with very low infiltration rates, may increase the risk of summer overheating under certain conditions, highlighting the importance of integrating natural ventilation strategies alongside improvements to envelope performance [66].

Other measures, such as internal floor insulation and external shading devices, had comparatively minor impacts. Floor insulation primarily improved heating loads but offered limited overall benefits, while shading devices reduced cooling demand but at the expense of higher winter heating requirements. Given South Australia’s heating-dominated climate, these measures should be considered supplementary rather than primary interventions.

The optimisation results reveal that the total heating and cooling loads for the 51 optimal designs achieved reductions ranging from 37% to 78% compared to the base case. Retrofitting older houses offers a valuable opportunity to enhance energy efficiency and reduce carbon emissions, but not all retrofitting strategies contribute equally to energy performance improvements. Positioning the Pareto-optimal designs against NCC 2022/NatHERS 7-star targets clarifies compliance pathways, as several configurations exceeded 7 stars in Climate Zone 5, indicating code-aligned retrofit routes for this typology. The findings show that improved airtightness combined with double or triple glazing consistently delivers significant energy efficiency gains across various configurations of other design variables. For 1930s double-brick houses, prioritising airtightness and glazing upgrades is particularly effective, offering substantial energy savings at a relatively low cost and with minimal construction complexity, making them suitable for wider adoption. While more complex options, such as wall or floor insulation retrofits, can provide additional benefits, they often involve higher financial costs and greater construction challenges. This study contributes to the existing body of research on cost-effective retrofit measures [53,68].

4.3. Future Research

Future research should develop climate-specific retrofitting strategies across Australia’s diverse climate zones, as this study focuses solely on the warm temperate conditions of South Australia. Broader regional investigations would help enhance the applicability of retrofit recommendations nationwide. Another critical area is the interaction between retrofitting strategies and occupant behaviour, as this plays a crucial role in the effectiveness of energy-saving measures. There are many studies available on the role of occupant behaviours in influencing thermal performance [69,70,71]. Understanding occupant preferences and habits, such as their comfort levels with temperature ranges, thermostat settings, and ventilation practices, can inform the development of more adaptable and effective retrofitting solutions. Optimising these behavioural factors is essential to maximise the benefits of retrofitting, reducing energy waste while improving occupant comfort.

Additionally, future research should incorporate an economic assessment alongside the simulation results. For each retrofit strategy, it is recommended to estimate capital and maintenance costs, compute simple payback and discounted life-cycle cost over an appropriate horizon, and test sensitivity to energy tariffs, discount rates and measure lifetimes. Annotating the optimisation results with cost bands will reveal a techno-economic Pareto front, improving the practical relevance of the findings for policy and industry. Incorporating cost assessment into optimisation will generate techno-economic retrofit pathways directly applicable to policy and industry practice.

Moreover, future climate scenarios could be considered. For instance, using weather data for 2030 or 2050 could assess how rising global temperatures might influence the thermal performance of older houses. These studies would help identify whether retrofitting strategies like enhanced insulation or glazing might become less critical over time due to changing external conditions, or whether additional measures, such as advanced ventilation systems or dynamic shading, will be required to maintain indoor comfort.

5. Limitations

This study has several limitations. One key limitation is the difficulty of isolating the impact of the building’s design and retrofitting strategies from external environmental factors, such as the surrounding landscape. The case study house is in an area with significant tree cover and natural features that provide shading, reduce heat gain, and improve cooling in summer, but could also worsen energy efficiency in winter by limiting solar heat gain. These factors may independently influence the building’s thermal performance and energy efficiency, making it challenging to determine whether the improvements observed are due solely to the design or retrofitting measures, or if the surrounding landscape also plays a significant role.

Second, occupancy schedules were derived from occupant interviews rather than in situ monitoring. This approach may introduce biases or omit short-term behavioural variations that influence energy use, such as thermostat adjustments, window operation, or appliance usage. Third, while the simulation model was calibrated with measured indoor temperature data, in situ diagnostic testing (e.g., blower door tests, U-value measurement) could not be undertaken due to tenancy constraints. As a result, envelope and infiltration parameters were initially based on literature values and later refined through calibration, which may limit the precision of model inputs.

Fourth, the optimisation analysis focused on thermal and energy performance, without incorporating cost, constructability, or heritage constraints. Consequently, while the results identify technically effective strategies, their economic viability and implementation feasibility remain untested.

Despite these limitations, this study provides valuable insights into the retrofit performance of older double-brick houses and offers practical recommendations for improving energy efficiency and thermal comfort in similar housing typologies. The findings are particularly relevant for South Australia and other regions with comparable warm-temperate climates, but further research should integrate site variability, occupant behaviour, and economic considerations to strengthen applicability for policy and practice.

6. Conclusions

This paper combines environmental monitoring, occupant responses, and building performance simulations supported by parametric optimisation analysis to examine envelope-focused retrofit pathways for a pre-war house built in the 1930s in Adelaide, Australia. The approach provides a transferable workflow for engineers, architects, and policymakers seeking to improve the energy performance of similar housing typologies in warm-temperate climates and demonstrates how evidence-based retrofit decision-making can be grounded in measured data and optimisation modelling.

Key insights emerged from the analysis:

- Baseline performance: The assumption that older houses are inherently inefficient has been challenged. Results show that original passive design features, such as generous internal volume, shaded openings, and cross-ventilation deliver excellent passive cooling performance in summer. However, inadequate winter comfort remains the dominant challenge, framing a clear seasonal priority for retrofit.

- Performance gains: Targeted envelope measures lowered heating and cooling demands by up to 78% and raised NatHERS ratings to 8.5 stars in best cases, demonstrating that code-compliant performance is achievable even for pre-war housing. Additional reductions are possible coupled with efficient HVAC options and rooftop photovoltaic (PV) systems.

- Retrofit priorities: Airtightness and glazing upgrades consistently offered the highest impact at relatively low cost and construction complexity, making them practical first steps for retrofitting older houses.

- Trade-offs: Wall and floor insulation and fixed shading delivered further gains but involved clear heating and cooling trade-offs. No single solution was optimal across all conditions, highlighting the importance of staged, context-specific retrofit strategies tailored to building typology, climate, and heritage constraints.

Future research should extend this framework to Australia’s diverse climate zones, integrate occupant behaviour and active systems with envelope measures, and incorporate economic assessment including payback and life-cycle costs. Developing techno-economic Pareto fronts will translate technical optima into retrofit packages that are technically effective, economically viable, and implementable within existing construction and heritage constraints.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.C. and D.K.; Methodology, E.C. and D.K.; Software, E.C. and L.A.M.; Validation, E.C. and L.A.M.; Formal analysis, E.C.; Investigation, E.C.; Resources, E.C., D.K. and L.A.M.; Data curation, E.C., D.K. and L.A.M.; Writing—original draft, E.C.; Writing—review & editing, E.C., D.K. and L.A.M.; Visualization, E.C.; Supervision, D.K. and L.A.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Verbal informed consent was obtained from the two household occupants prior to data collection. Participation involved only non-identifiable behavioural information and posed minimal risk. All occupancy data used in this research remain anonymised.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in figshare at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30948467, accessed on 21 December 2025.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to the occupants of the 1930s house studied in this research for their valuable contributions. This work would not have been possible without their generous support and understanding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| ASHRAE | American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers |

| CV | Coefficient of variation |

| HVAC | Heating, ventilation and air conditioning |

| NatHERS | Nationwide House Energy Rating Scheme (Australia) |

| NCC | National Construction Code (Australia) |

| PV | Photovoltaic |

| RMSE | Root Mean Squared Error |

| R-value | A measure of a material’s ability to resist heat flow (m2K/W) |

| U-value | A measure of the material’s ability to conduct heat (W/m2K) |

References

- World Green Building Council. Embodied Carbon. Available online: https://worldgbc.org/advancing-net-zero/embodied-carbon/ (accessed on 23 October 2024).

- Razzhigaeva, N. Net Zero for Australia’s Built Environment is Possible by 2040, UNSW Sites. Available online: https://www.unsw.edu.au/newsroom/news/2023/02/net-zero-for-australia-s-built-environment-is-possible-by-2040 (accessed on 21 September 2025).

- Seo, S.; Foliente, G. Carbon Footprint Reduction through Residential Building Stock Retrofit: A Metro Melbourne Suburb Case Study. Energies 2021, 14, 6550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifhashemi, M.; Capra, B.R.; Milller, W.; Bell, J. The potential for cool roofs to improve the energy efficiency of single storey warehouse-type retail buildings in Australia: A simulation case study. Energy Build. 2018, 158, 1393–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Building Codes Board. National Construction Code 2019 Volume 1. 2019. Available online: https://www.abcb.gov.au/sites/default/files/resources/2022/Handbook-energy-efficiency-NCC-Volume-One-2019.pdf (accessed on 11 July 2024).

- NatHERS. Star Band Criteria. 2022. Available online: https://www.nathers.gov.au/sites/default/files/2019-10/NatHERS%20Star%20bands.pdf (accessed on 11 July 2024).

- Australian Building Codes Board. National Construction Code 2022 Volume 2. 2023. Available online: https://ncc.abcb.gov.au/system/files/ncc/ncc2022-volumetwo-20230501b.pdf (accessed on 11 July 2024).

- ClimateWorks Australia. Defining Zero Carbon Homes for a Climate Resilient Future; ClimateWorks Australia: Docklands, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Rajagopalan, P.; Chen, D.; Ambrose, M. Investigating envelope retrofitting potential and resilience of Australian residential buildings—A stock modelling approach. Energy Build. 2024, 325, 114990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, S.; Foliente, G.; Ren, Z. Energy and GHG reductions considering embodied impacts of retrofitting existing dwelling stock in Greater Melbourne. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 170, 1288–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CSIRO. It’s in the Stars! How Scientists Figure Out Your Home’s Energy Rating. Available online: https://www.csiro.au/en/news/All/Articles/2021/September/its-in-the-stars-how-scientists-figure-out-your-homes-energy-rating (accessed on 5 September 2024).

- Xu, X.; Sunindijo, R.Y.; Mussi, E. Comparing user satisfaction of older and newer on-campus accommodation buildings in Australia. Facilities 2021, 39, 389–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicol, F. Temperature and adaptive comfort in heated, cooled and free-running dwellings. Build. Res. Inf. 2017, 45, 730–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baird, G. Did that building feel good for you? Or—Isn’t it just as important to assess and benchmark users’ perceptions of buildings as it is to audit their energy efficiency? Intell. Build. Int. 2011, 3, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, A.; Williamson, T.; Pisaniello, D.; Bennetts, H.; van Hoof, J.; Arakawa Martins, L.; Visvanathan, R.; Zuo, J.; Soebarto, V. The Thermal Environment of Housing and Its Implications for the Health of Older People in South Australia: A Mixed-Methods Study. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soebarto, V.; Bennetts, H.; Hansen, A.; Zuo, J.; Williamson, T.; Pisaniello, D.; Van Hoof, J.; Visvanathan, R. Living environment, heating-cooling behaviours and well-being: Survey of older South Australians. Build. Environ. 2019, 157, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loughnan, M.; Carroll, M.; Tapper, N.J. The relationship between housing and heat wave resilience in older people. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2015, 59, 1291–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Molina, A.; Tort-Ausina, I.; Cho, S.; Vivancos, J.-L. Energy efficiency and thermal comfort in historic buildings: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 61, 70–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, G.; Verde, L.; Olofsson, T. A Review on Technical Challenges and Possibilities on Energy Efficient Retrofit Measures in Heritage Buildings. Energies 2022, 15, 7472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciulla, G.; Galatioto, A.; Ricciu, R. Energy and economic analysis and feasibility of retrofit actions in Italian residential historical buildings. Energy Build. 2016, 128, 649–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menconi, M.; Painting, N.; Piroozfar, P. Simulated Results of a Passive Energy Retrofit Approach for Traditional Listed Dwellings in the UK. Energies 2025, 18, 850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, F.; Blight, T.; Natarajan, S.; Shea, A. The use of Passive House Planning Package to reduce energy use and CO2 emissions in historic dwellings. Energy Build. 2014, 75, 216–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisello, A.L.; Petrozzi, A.; Castaldo, V.L.; Cotana, F. Energy Refurbishment of Historical Buildings with Public Function: Pilot Case Study. Energy Procedia 2014, 61, 660–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez Gálvez, F.; Rubio de Hita, P.; Ordóñez Martín, M.; Morales Conde, M.J.; Rodríguez Liñán, C. Sustainable restoration of traditional building systems in the historical centre of Sevilla (Spain). Energy Build. 2013, 62, 648–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şahin, C.D.; Arsan, Z.D.; Tunçoku, S.S.; Broström, T.; Akkurt, G.G. A transdisciplinary approach on the energy efficient retrofitting of a historic building in the Aegean Region of Turkey. Energy Build. 2015, 96, 128–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timur, B.A.; Başaran, T.; İpekoğlu, B. Thermal retrofitting for sustainable use of traditional dwellings in Mediterranean climate of southwestern Anatolia. Energy Build. 2022, 256, 111712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Soebarto, V.; Griffith, M. Strategies for reducing heating and cooling loads of uninsulated rammed earth wall houses. Energy Build. 2014, 77, 323–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Soebarto, V.; Griffith, M. Achieving thermal comfort in naturally ventilated rammed earth houses. Build. Environ. 2014, 82, 588–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Soebarto, V.; Griffith, M. Design optimization of insulated cavity rammed earth walls for houses in Australia. Energy Build. 2015, 86, 852–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakiyama, N.R.M.; Carlo, J.C.; Mazzaferro, L.; Garrecht, H. Building Optimization through a Parametric Design Platform: Using Sensitivity Analysis to Improve a Radial-Based Algorithm Performance. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, T.; Zhang, D.; AlGhamdi, A.S.; Ullah, F.; Alshamrani, S.S. Design parametric analysis of low-energy residential buildings on the way to a defined cost-optimal capacity point. Alex. Eng. J. 2022, 61, 8297–8313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, M.; van den Dobbelsteen, A.; Voskuilen, P. A Parametric Modelling Approach for Energy Retrofitting Heritage Buildings: The Case of Amsterdam City Centre. Energies 2024, 17, 994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manfren, M.; Aste, N.; Leonforte, F.; Del Pero, C.; Buzzetti, M.; Adhikari, R.S.; Zhixing, L. Parametric energy performance analysis and monitoring of buildings—HEART project platform case study. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 61, 102296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guattari, C.; Cristo, E.D.; Evangelisti, L.; Gori, P.; Cureau, R.J.; Fabiani, C.; Pisello, A.L. Thermal characterization of building walls using an equivalent modeling approach. Energy Build. 2025, 329, 115226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cusenza, M.A.; Guarino, F.; Longo, S.; Cellura, M. An integrated energy simulation and life cycle assessment to measure the operational and embodied energy of a Mediterranean net zero energy building. Energy Build. 2022, 254, 111558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Bureau of Meteorology. Climate Classification Maps, Bureau of Meteorology. Available online: http://www.bom.gov.au/climate/maps/averages/climate-classification/ (accessed on 2 May 2025).

- Google Maps. Prospect, SA. Available online: https://www.google.com/maps/place/Prospect,+SA/@-34.8846484,138.5798172,5590m/data=!3m2!1e3!4b1!4m6!3m5!1s0x6ab0c901968fb601:0x1b538e1662e6942e!8m2!3d-34.8828879!4d138.5937955!16zL20vMDZsM2I3?entry=ttu&g_ep=EgoyMDI1MDgxOC4wIKXMDSoASAFQAw%3D%3D (accessed on 21 August 2025).

- Australian Bureau of Meteorology. Climate Statistics for Australian Locations (Monthly Climate Statistics—Adelaide (Kent Town)). Available online: https://www.bom.gov.au/climate/averages/tables/cw_023090.shtml (accessed on 21 August 2025).

- Persse, J.N. House Styles in Adelaide: A Pictorial History; Australian Institute of Valuers: Belrose, Australia, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Government of South Australia. Historic Area Statements and Character Area Statements. 2020. Available online: https://plan.sa.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/613299/Historic_Area_Statements_and_Character_Area_Statements_-_Phase_3.pdf (accessed on 6 September 2025).

- ABS. 2021 South Australia, Census All persons QuickStats|Australian Bureau of Statistics. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/census/find-census-data/quickstats/2021/4?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Pathan, A.; Mavrogianni, A.; Summerfield, A.; Oreszczyn, T.; Davies, M. Monitoring summer indoor overheating in the London housing stock. Energy Build. 2017, 141, 361–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASHRAE. ASHRAE 55-2020|ASHRAE Store. Available online: https://store.accuristech.com/ashrae/standards/ashrae-55-2020?product_id=2207271 (accessed on 7 November 2024).

- NatHERS. Internal Heat Loads|Nationwide House Energy Rating Scheme (NatHERS). Available online: https://www.nathers.gov.au/nathers-accredited-software/internal-heat-loads (accessed on 7 November 2024).

- Soebarto, V. Calibration of hourly energy simulations using hourly monitored data and monthly utility records for two case study buildings. In Proceedings of the International IBPSA Building Simulation Conference and Exhibition, Prague, Czech Republic, 8–10 September 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Chai, T.; Draxler, R.R. Root mean square error (RMSE) or mean absolute error (MAE)?—Arguments against avoiding RMSE in the literature. Geosci. Model Dev. 2014, 7, 1247–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, L.A.; Williamson, T.; Bennetts, H.; Soebarto, V. The use of building performance simulation and personas for the development of thermal comfort guidelines for older people in South Australia. J. Build. Perform. Simul. 2022, 15, 149–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Možina, M.; Pajek, L.; Nadarajah, P.D.; Singh, M.K.; Košir, M. Defining the calibration process for building thermal performance simulation during the warm season: A case study of a single-family log house. Adv. Build. Energy Res. 2024, 18, 180–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DesignBuilder Software Ltd. Optimisation. Available online: https://designbuilder.co.uk/helpv7.0/Content/Optimisation.htm (accessed on 13 November 2024).

- Whitehouse, M.; Osmond, P.; Daly, D.; Kokogiannakis, G.; Jones, D.; Picard-Bromilow, A.; Cooper, P. Guide to Low Carbon Residential Buildings—Retrofit; CRC for Low Carbon Living: Sydney, Australia, 2019; Available online: https://apo.org.au/node/235556 (accessed on 7 November 2024).

- Sustainability Victoria. Comprehensive Energy Efficiency Retrofits to Existing Victorian Houses. 2019. Available online: https://www.sustainability.vic.gov.au/research-data-and-insights/research/research-reports/household-retrofit-trials (accessed on 19 August 2024).

- ABS. 4182.0 Australian Housing Survey—Housing Characteristics, Costs and Conditions (1999); Australian Bureau of Statistics: Canberra, Australia, 2000.

- Whaley, D.M.; O’Leary, T.; Al-Saedi, B. Cost Benefit Analysis of Simulated Thermal Energy Improvements Made to Existing Older South Australian Houses. Procedia Eng. 2017, 180, 272–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sustainability Victoria. Draught Sealing Retrofit Trial; Sustainability Victoria: Melbourne, Australia, 2016.

- Omrany, H.; Soebarto, V.; Ghaffarianhoseini, A. Rethinking the concept of building energy rating system in Australia: A pathway to life-cycle net-zero energy building design. Archit. Sci. Rev. 2022, 65, 42–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Building Codes Board. National Construction Code 2019 Volume 2; Australian Building Codes Board: Canberra, Australia, 2019.

- Daniel, L.; Baker, E.; Williamson, T. Cold housing in mild-climate countries: A study of indoor environmental quality and comfort preferences in homes, Adelaide, Australia. Build. Environ. 2019, 151, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pikusa, S. The Adelaide House, 1836 to 1901: The Evolution of Principal Dwelling Types; Wakefield Press: South Australia, Australia, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Ambrose, M.; Syme, M. Air Tightness of New Australian Residential Buildings. Procedia Eng. 2017, 180, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojić, M.; Djordjević, S.; Stefanović, A.; Miletić, M.; Cvetković, D. Decreasing energy consumption in thermally non-insulated old house via refurbishment. Energy Build. 2012, 54, 503–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morelli, M.; Rønby, L.; Mikkelsen, S.E.; Minzari, M.G.; Kildemoes, T.; Tommerup, H.M. Energy retrofitting of a typical old Danish multi-family building to a “nearly-zero” energy building based on experiences from a test apartment. Energy Build. 2012, 54, 395–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, R.; Pavía, S. Thermal performance of a selection of insulation materials suitable for historic buildings. Build. Environ. 2015, 94, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, C.; Jiang, X.; Li, B. Adaptive building envelope combining variable transparency shape-stabilized PCM and reflective film: Parameter and energy performance optimization in different climate conditions. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 299, 117907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felimban, A.; Knaack, U.; Konstantinou, T. Evaluating Savings Potentials Using Energy Retrofitting Measures for a Residential Building in Jeddah, KSA. Buildings 2023, 13, 1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simko, T.; Moore, T. Optimal window designs for Australian houses. Energy Build. 2021, 250, 111300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaral, A.R.; Rodrigues, E.; Gaspar, A.R.; Gomes, Á. A thermal performance parametric study of window type, orientation, size and shadowing effect. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2016, 26, 456–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuffrida, G.; Detommaso, M.; Nocera, F.; Caponetto, R. Design Optimisation Strategies for Solid Rammed Earth Walls in Mediterranean Climates. Energies 2021, 14, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belusko, M.; O’Leary, T. Cost Analyses of Measures to Improve Residential Energy Ratings to 6 Stars—Playford North Development, South Australia. Constr. Econ. Build. 2010, 10, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, G.; Newborough, M. Dynamic energy-consumption indicators for domestic appliances: Environment, behaviour and design. Energy Build. 2003, 35, 821–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra Santin, O.; Itard, L.; Visscher, H. The effect of occupancy and building characteristics on energy use for space and water heating in Dutch residential stock. Energy Build. 2009, 41, 1223–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, L.; Soebarto, V.; Williamson, T. House energy rating schemes and low energy dwellings: The impact of occupant behaviours in Australia. Energy Build. 2015, 88, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.