Abstract

With the growing trend of incorporating waste and industrial by-products in infrastructure, airport pavements built with sustainable materials are of increasing interest. This research developed six theoretical concrete mixtures for airport pavement and evaluated their financial, social and environmental cost within a stochastic triple bottom line framework. A Monte Carlo simulation was used to capture uncertainty in key parameters, particularly material transport distances, embodied carbon, and cost variability, allowing a probabilistic comparison of conventional and sustainable mixtures. The results showed that mixtures incorporating supplementary cementitious materials, recycled concrete aggregate and geopolymer cement consistently outperformed the ordinary Portland cement benchmark across all triple bottom line dimensions. Geopolymer concrete offered the greatest overall benefit, while the mixture containing blast furnace slag aggregate demonstrated how long haulage distances can significantly erode sustainability gains, highlighting the importance of locally available materials to sustainability. Overall, the findings provide quantitative evidence that substantial triple bottom line cost reductions are achievable within current airport pavement specifications, and even greater benefits are possible if specifications are expanded to include emerging low-carbon technologies such as geopolymer cement. These outcomes reinforce the need for performance-based specifications that permit the use of recycled materials and industrial by-products in pursuit of sustainable airport pavement practice.

1. Introduction

Traditional rigid airport pavement specifications in some regions, including Australia, have historically mandated the use of virgin natural aggregates (NA) and ordinary Portland cement (OPC), limiting the inclusion of recycled materials or industrial by-products [1]. This conservative approach persists despite growing societal expectations for more sustainable infrastructure and an increasing global imperative to reduce the environmental impacts of construction materials [1,2,3]. Conventional concrete manufacture is resource intensive. The extraction and processing of NA contributes to land use change and depletion of high-quality quarry sources [4], while OPC production accounts for an estimated 7–8% of global CO2 emissions [5,6]. These emissions arise both through calcination of raw materials (≈60%) and fossil fuel combustion for clinker production (≈40%) [7,8]. As the world’s most-consumed material after water, concrete therefore poses a substantial sustainability challenge for present and future infrastructure development [7]. International climate commitments, including the Paris Agreement on climate change reduction [9], underscore the urgency of reducing carbon intensity in concrete to limit global warming well below 2 °C [10,11].

In response, research has increasingly focused on integrating sustainable materials and circular economy principles into pavement construction [12,13,14,15]. The circular economy paradigm, first articulated in the 1970s, promotes the recirculation of materials at their highest value, replacing linear “take, make, use, dispose” practices [16]. Policies in jurisdictions including China, Australia, Canada and the European Union now encourage these practices, alongside global efforts to decarbonize concrete production [2,5,17]. Within this context, by-products from iron making and coal-fired power generation, as well as recycled concrete, represent viable constituent materials for pavement concrete [1,18,19]. Incorporating these materials can yield substantial environmental, social and economic benefits, although uptake in airport pavements remains uneven due to prescriptive specifications in some jurisdictions [1].

Rigid concrete pavements form an important part of the movement surface inventory at many airports, used on runways, taxiways and aprons, despite asphalt pavements being the primary airport pavement movement surface in many regions, such as Australia [20]. Rigid pavements are commonly comprised of rectangular slabs of unreinforced Portland cement concrete (PCC), constructed on a high-quality granular or bound subbase over a natural or prepared subgrade [21,22]. Unlike flexible pavements, which rely on cascading reduction of deflection from higher-strength upper pavement layers to underlying lower-strength layers and subgrade [21], rigid airport pavements function as monolithic slabs with high flexural stiffness that enables them to span lower-strength sub-layers and minimize deformation. A characteristic flexural strength of 4.5 MPa to 4.8 MPa is typically specified [23]. Construction and maintenance are similar to that of road pavements [21]. However, airport-specific requirements include slow-moving heavy wheel loads and resistance to fuel and chemicals, where the absence of loose surface particles and high surface flatness support critical aircraft safety. Consequently, construction involves careful control of material quality, slab thickness, joint spacing, slab load transfer systems and curing conditions to ensure long-term structural and functional performance under the complex loading imposed by modern aircraft.

The low tolerance for operational disruption contributes to conservative adoption of innovative materials in airport pavements [1,24]. In fact, Helsel, et al. [25] identified that for the concrete industry more broadly, readily implementable strategies to improve sustainability are not fully deployed due to risk aversion, outdated specifications and regulations that limit innovation, and the risk of deficient long-term performance. Despite this, many road and pavement authorities permit the use of selected industrial by-products and waste materials [1], including supplementary cementitious materials (SCMs), such as fly ash (FA) and ground granulated blast furnace slag (GGBFS), as well as blast furnace slag (BFS) aggregate and recycled concrete aggregate (RCA) [1,13]. These materials reduce embodied carbon, enhance resource efficiency, and support circular economy objectives, and for SCMs, decades of research demonstrate their capacity to improve durability, workability and long-term strength [26,27,28,29,30,31].

Geopolymer cement concrete (GPC) offers a further low-carbon alternative, relying on the polymerization of aluminosilicate precursors rather than OPC hydration [32,33]. Field applications, such as Toowoomba Wellcamp Airport in Queensland, Australia, demonstrate its feasibility, with reported CO2 reductions of up to 80% relative to OPC-based equivalents [34]. However, embodied carbon and cost of GPC can vary due to activator type and mix composition [35,36,37], and no known road or airport pavement specifications currently permit GPC binder. Additionally, research [38] showed that up to 50% RCA can be incorporated into GPC mixtures without significant reductions in mechanical performance.

Recycled aggregates contribute to sustainability by reducing demand for virgin NA and diverting waste from landfill, with the growing volume of construction and demolition waste worldwide a significant issue [39,40]. RCA and BFS aggregates are recognized in some pavement specifications, with airport pavement-sourced RCA offering strong potential as the material previously met specification requirements [41], with economic benefits through reduced haulage [1]. Up to 50% RCA replacement is feasible without compromising mechanical performance when combined with SCM use [42]. BFS aggregates, derived from iron making, preserve the energy already used in iron production and can fully substitute coarse aggregate in some pavement specifications due to desirable mechanical properties [43,44], though limited supply may constrain widespread adoption [19].

The sustainability of airport pavements encompasses environmental, social and economic dimensions [13,15], forming the Triple Bottom Line (TBL), a framework that allows the evaluation of competing sustainability objectives [45]. Environmental performance is typically assessed through a life cycle assessment (LCA), using embodied carbon as the metric, often reported in Environmental Product Declarations (EPDs) [14,46]. EPDs generally cover the cradle-to-gate system boundary, reporting environmental indicators summed over the three stages of A1 (raw material extraction and supply), A2 (transport), and A3 (production). For concrete materials, the most prevalent environmental indicator is greenhouse gas emissions expressed as kilograms of CO2-equivalent per unit, commonly reported in EPDs as total global warming potential (GWP-t) [14]. Social and economic benefits include resource conservation, reduced reliance on virgin materials, and life cycle cost savings [13,47]. Durability is critical [41], as premature deterioration or maintenance erodes potential sustainability gains [13].

Recent research indicates that the quantified TBL cost–benefit potential of sustainable airport pavement mixtures is a gap [1]. Accordingly, this study aims to quantify the TBL cost of concrete mixtures incorporating waste and recycled materials using stochastic methods, and compare them to an OPC-based benchmark, accounting for variability in material composition, embodied carbon, transport distances and financial costs. The objectives of this work were:

- To calculate stochastic social, environmental and financial costs for mixtures containing waste and recycled materials and compare them to a conventional OPC mixture;

- To calculate the theoretical combined TBL cost to identify mixtures most likely to improve overall sustainability under Australian conditions.

By providing quantitative evidence of the benefits of SCMs, RCA, BFS and GPC, this study strengthens the case for sustainable airport pavement practices, supports specification reform, and advances circular economy and low-carbon strategies in rigid airport pavements.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Concrete Mixture Composition and Assessment Boundary Scenario

The reference mixture was a conventional OPC concrete mixture that conforms to typical Australian specifications employed in airport pavement construction. This baseline was contrasted by four alternative mixtures that integrated waste or recycled materials consistent with the limits permitted under current road and airfield rigid pavement specifications [1] or supported by findings in the recent literature. Two of these mixtures were formulated to achieve the maximum allowable SCM content as allowed by FAA Specification P-501 [22], thereby representing the upper threshold of SCM substitution permitted under contemporary specifications for rigid airport pavement. To further explore the potential for enhanced sustainability through material reuse, a sixth mixture was included that comprised a GPC system incorporating 50% coarse RCA. This configuration represents an upper-bound scenario for waste material use, one that is supported by emerging research but not yet reflected in pavement specifications.

Table 1 outlines the composition of each mixture. Each mixture also contains water, admixture and air according to the distributions in Table 2, which also contains other distribution inputs required to calculate the costs of each mixture. OPC binder mass, water-to-binder ratio (w/b), air content and admixture dosage distributions are based on ranges typical of Australian practice. The GPC binder, containing FA and GGBFS precursor and dry alkali activator solids, is characterized based on information available about its use on an Australian airport pavement project completed in 2014 [34], with the resultant mass distribution having slightly higher proportions compared to OPC due to the dry activator included in its cementitious mass.

Table 1.

Concrete mixture compositions.

Table 2.

Input parameters for calculating concrete mixture compositions.

The aggregate portion for each mixture is determined by subtracting the volume of paste from 1 m3, that is, the balance of 1000 L when the volumes of water, binder, admixtures and air have been subtracted. The fine and coarse fractions are then determined as per the proportions in Table 1, with the resultant mass determined by multiplying the volume of each material by its respective density as per Table 3. This simplification of aggregate proportions is suitable for this theoretical model; however, it may not reflect the changes to aggregate proportions required in practice to ensure workability.

Table 3.

Constituent material density (SG or SSD (kg/m3)).

The calculations for this study are based around a realistic scenario: a large concrete pavement project on a major Australian capital city airport, where the batching of concrete is occurring on the airport project site, with the functional unit being 1 m3 of pavement concrete. An LCA-informed modeling approach was adopted to estimate GWP-t and financial cost for comparative purposes, recognizing that the analysis does not constitute an ISO 14040 and ISO 14044-compliant life cycle assessment. The scope covers the cradle-to-gate boundary, as costs beyond the cradle-to-gate boundary, such as those incurred in construction, use, maintenance and disposal, have not been considered assuming all concrete mixtures perform similarly over time. In this context, the A1 stage represents each constituent material cost at its source, the A2 stage represents the transport costs from material source to project site, and A3 represents the concrete batching costs occurring on site. This approach aims to highlight the upfront sustainability cost of constituent material choices. The cradle-to-gate boundary is illustrated by Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Illustration of cradle-to-gate boundary for environmental and financial cost calculation (adapted from [48]).

2.2. Determination of Envrionmental, Financial, Transport and Batching Costs Distributions

For the environmental cost calculation, the impact category chosen to represent environmental cost is GWP-t (kg CO2-eq/m3). A range of Australasian EPDs were primarily used to inform the environmental cost distributions in Table 4, as well as data reported in previous studies [1,49]. The environmental cost distributions for GPC were informed by proprietary product carbon footprint data and estimates of embodied carbon reduction compared to OPC reported in the recent literature [35,50]. A survey of Australian industry suppliers was used to determine the likely range of financial cost rates for materials which informed the distributions, shown in Table 5.

Table 4.

Probability distributions for constituent material environmental cost (kg CO2-eq/kg).

Table 5.

Probability distributions for constituent material financial cost (AUD/kg).

Transport distances for materials were estimated by assessing the distance from material sources to a number of major Australian airports, with these distances informing the resultant distribution for each material in Table 6. Lognormal distributions were used and truncated to ensure relevant minimum and maximum transport distances bounded the distribution for each material. The absence of a transport distance distribution for both water and admixture is explained below.

Table 6.

Probability distributions for constituent material transport distance (km).

Transport costs for both admixtures and water are considered to be zero. Water is assumed to be available at the batching site, attracting no transport cost, and the cost of transport of admixtures is negligible even at distances of 1000 km (less than AUD 0.80), due to admixtures being small in mass relative to other constituent materials.

Inputs for transport and concrete batching financial and environmental cost are in Table 7. Transport environmental cost distributions were informed by the road transport emissions factors for a range of realistic transport vehicles reported by AusLCI [51], and financial cost rates were informed through industry survey. The environmental cost distributions for the batching of 1 m3 concrete were informed by limited sources [52,53], with batching financial cost distributions informed by industry survey.

Table 7.

Probability distributions for transport (A2) cost rates and batching (A3) cost rates.

2.3. Monte Carlo Simulation

The Monte Carlo method is a numerical technique that employs random sampling and probabilistic modeling to obtain solutions to complex problems. The method aims to replicate natural variability through direct simulation, representing potential outcomes using probability distributions that describe uncertain parameters [54]. Therefore, the Monte Carlo method is a practical way of calculating a wide range of outcomes for the cost of a concrete mixture when complexity exists in the variability of both material and process costs and the mixture composition itself. This Monte Carlo simulation method is therefore suitable to assess the range of resultant costs of the concrete mixtures being analyzed, as there is natural variability in the cost of concrete materials due to regional availability of the raw resources, regional processing requirements, fuel types and availability, and transport distances—all factors which impact the resultant embodied emissions and financial cost. This stochastic analysis of sustainable airport concrete mixtures across the cradle to gate has been recognized as a gap in previous research by Newton-Hoare, Jamieson and White [1]. Palde @RISK Version 8.9 in Microsoft Excel [55] was used to create input distributions and run the Monte Carlo simulations to calculate costs for each mixture. Output simulations were run using 10,000 iterations.

2.4. Calculation of Environmental, Social and Financial Costs for Concrete Mixtures

For each mixture, each constituent material mass was multiplied by its respective embodied carbon and financial cost rate and summed to produce a kg CO2-eq/m3 and AUD/m3 value, which represents the environmental and financial cost for that mixture, respectively. Then, the total A1–A3 environmental and financial cost of each mixture was determined by the following equation:

where:

Total mixture cost (AUD/m3 or kg CO2-eq m3) = tA1 + tA2 + A3

- tA1 = ∑ (material mass (kg) × material cost rate (AUD/kg or kg CO2-eq/kg))

- tA2 = ∑ (material mass (kg) × material transport distance (km) × transport cost rate (kg CO2-eq/kg.km or AUD/kg.km))

- A3 = batching cost rate (AUD/m3 or kg CO2-eq/m3)

The social cost for each mixture was determined by firstly calculating the sum of the volume of the recycled or waste materials, namely, GPC, FA, GGBFS, RCA, BFS in each mixture, with the volume of material constituents determined using the specific gravity (SG) or saturated surface dry (SSD) density values in Table 3. The social cost was then determined by subtracting the volume of waste material from 1 m3, to represent the volume of virgin materials consumed per 1 m3.

2.5. Quantifying the TBL Cost

Quantifying the overall TBL cost requires the application of a normalization process to the social, financial and environmental results, as each dimension was measured in different units and therefore cannot be directly compared or aggregated. Normalization is critical to transform heterogeneous data into a common scale [56]. Max-based normalization was applied to the results of each of the social, environmental and financial cost calculations for each mixture using Equation (2).

where:

- x = Mixture cost

- xmax = Maximum mixture cost

Following normalization, a single composite TBL cost was derived by combining the social, environmental and financial costs for each mixture. Several approaches exist for generating a combined TBL score, including the use of weighting factors that reflect specific project or procurement priorities. However, for this study, equal weight was assigned to each component, as illustrated in Equation (3). In this approach, each TBL dimension corresponds to the length of one side of an equilateral triangle, with the resulting TBL score represented by the area of that triangle—an approach adopted in prior airport pavement studies [57,58]. These TBL cost results were then again normalized using Equation (2). As a result of the Monte Carlo simulation to calculate the cost of each mixture, each of the social, environmental and financial cost results were distributions. Therefore, when combined using Equation (3), the resultant TBL cost was also a distribution.

where:

- S = Normalized social cost distribution

- E = Normalized environmental cost distribution

- F = Normalized financial cost distribution

3. Results and Discussion

Based on the methods and assumptions presented above, the results were calculated for each of the social, financial and environmental costs for each mixture, as well as the combined TBL cost, which are discussed further below.

3.1. Financial Costs

Figure 2 shows the relative frequency distribution of financial cost for each mixture against the 90% confidence interval (CI) for the OPC Control mixture. Table 8 shows the minimum, median, mean and maximum financial cost of each mixture, as well as the 90% CI, represented as those values between the 5th percentile (5%) and 95th percentile (95%). The distribution of financial costs between mixtures is relatively consistent for all mixtures except the BFS mixture. With 66% of results falling above the 90% CI for the OPC mixture, the poor and highly variable performance for the BFS mixture compared to the other five mixtures is driven primarily by the wide variation in the transport distance of BFS aggregate (influenced by the transport distance distribution informed by a single source of the material in Australia), enough to overshadow the marginal benefits that the same mixture with NA (FA10 GGBFS45) has compared to the OPC benchmark. This finding is consistent with literature that indicates that transport costs for aggregate sources is often a governing factor in their financial viability [19]. However, the minimum cost of the BFS mixture (AUD 265/m3) indicates that for projects with low or NA-comparable transport distances for BFS aggregate, financial costs can be competitive. The FA25 RCA50 mixture shows the lowest cost, with both the lowest mean cost and the narrowest cost range, indicating lower variability in the material and transport inputs. The FA40 mixture has a very similar cost profile compared to the OPC mixture, with the lower material cost of FA neutralized by higher transport costs due to greater transport distance variability compared to OPC. The FA25 RCA50 mixture also has the lowest maximum cost, but only AUD 1/m3 lower than the GPC mixture. The GPC has slightly higher median and mean, at AUD 385/m3 and AUD 391/m3, respectively, compared to the OPC, FA40, FA10 GGBFS45 and FA25 RCA50 mixtures, which are all tightly clustered; however, the results do not indicate that a significant cost penalty exists. This comparative cost range for GPC is supported by the inclusion of 50% coarse RCA, which has a slightly lower cost distribution profile compared to NA. The results indicate that while financial cost reduction is possible using mixtures that contain waste and recycled materials, financial cost may not be a significant differentiator between mixtures, unless there is a significant difference in the transport distance for the material source, particularly aggregate (of any origin).

Figure 2.

Relative frequency of financial costs of mixtures.

Table 8.

Financial costs of mixtures distribution data (AUD/m3).

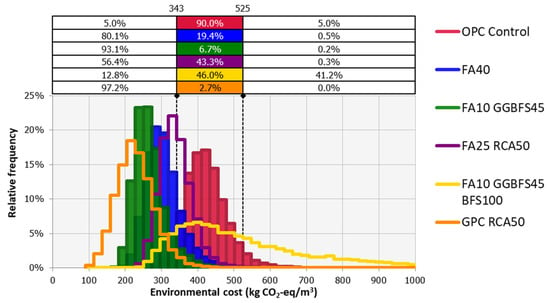

3.2. Environmental Costs

Figure 3 shows the relative frequency distribution of environmental costs for each mixture against the 90% CI for the OPC Control mixture. Table 9 shows the minimum, median, mean and maximum environmental cost as well as the 90% CI for each mixture. The results show clear differentiation between mixture types, with the GPC mixture having the lowest environmental cost distribution with a 90% CI of 150 to 322 kg CO2-eq/m3. The GPC mixture showed 97% of results falling below the 90% CI of the conventional OPC benchmark. The greatest contribution to this saving is the complete replacement of OPC binder with significantly lower carbon GPC binder, with the mean result indicating a 45% reduction in embodied carbon compared to the mean of the OPC benchmark. While the composition of the GPC binder has been simplified in this analysis, it would be interesting future work to evaluate the embodied carbon of all GPC binder systems suitable for airport pavement applications. The next-best-performing mixtures are the high proportion SCM mixtures of FA40 and FA10 GGBFS45, with 80% and 93% of results, respectively, falling below the 90% CI of the OPC mixture. The mean results indicate that the FA40 and FA10 GGBFS45 mixtures can reduce the environmental cost by 28% and 36%, respectively, linked to the reduction in emissions-intensive OPC.

Figure 3.

Relative frequency of environmental costs of mixtures (kg CO2-eq/m3).

Table 9.

Environmental costs of mixtures (kg CO2-eq/m3).

The relatively high financial cost of the BFS mixture, previously discussed, was matched by highly uncertain environmental performance, with the resulting distribution showing the same high mean, median and maximum values of a thick upper tail, driven by the highly variable and large potential maximum transport distance of BFS aggregate. This indicates potential large environmental burdens can be accumulated when the haulage distance for one or more concrete constituent materials, especially aggregate, is large. This highly uncertain environmental performance, indicated by the 90% CI of 305 kg CO2-eq/m3 to 995 kg CO2-eq/m3, is contrasted by the same mixture with NA, the FA10 GGBFS45 mixture, that shows a much tighter range for the 90% CI, of 252 kg CO2-eq/m3 to 356 kg CO2-eq/m3, further indicating that results are highly sensitive to aggregate transport distance. These findings align with studies by DeRousseau et al. [59] and Sabău et al. [60] that found large transport distances of waste-based constituent materials can offset environmental gains.

The OPC mixture is one of the worst-performing mixtures, with the highest minimum (285 kg CO2-eq/m3) and 5th percentile (343 kg CO2-eq/m3) values, and the second-highest mean value (425 kg CO2-eq/m3), reaffirming the high inherent emissions associated with OPC concrete. The FA25 RCA50 mixture, with a mean of 340 kg CO2-eq/m3, offers an around 20% reduction in embodied emissions compared to the OPC baseline mean, and has significantly lower maximum cost (680 kg CO2-eq/m3) compared to all mixtures except the GPC mixture, indicating less uncertainty in its strong environmental performance.

The mean environmental cost of the OPC mixture was similar to that reported by the Australian Life Cycle Assessment Society (ALCAS) for 40 MPa concrete, at 456 kg CO2-eq/m3, but substantially lower than the GWP-t of 50 MPa concrete, at 578 kg CO2-eq/m3 [50], indicating that the model and parameters selected for the OPC mixture could have resulted in an underestimation of GWP-t in the Australian context. This is likely attributed to the mean environmental cost factor for OPC in this analysis being lower than that used by ALCAS.

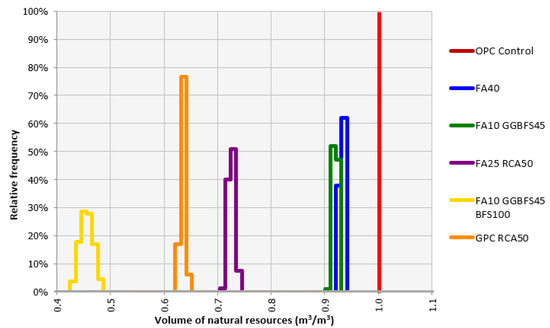

3.3. Social Costs

Figure 4 shows the relative frequency distribution of social costs for each mixture. Table 10 shows the minimum, mean, median, maximum and 90% CI for each mixture. These results show clear differentiation for each mixture, with the OPC mixture relying solely on virgin natural materials and therefore serving as the least-sustainable benchmark. The FA40 and FA10 GGBFS45 mixtures with high SCM substitution provide only marginal reductions in social cost, having 93% and 92% of the mean social cost, respectively, whereas the three mixtures containing recycled aggregates have between 46% to 73% of the mean social cost of the OPC mixture. This reflects the relatively small proportion of volume occupied by the binder compared to the aggregate portion, meaning that a given proportion of NA substitution (i.e., 50% of coarse aggregate) will have a greater social cost reduction compared to the same proportion of OPC being replaced with SCMs (i.e., 50% OPC binder replaced by SCMs). These results confirm that while SCM use contributes to a reduction in social cost, by far the greatest reduction potential is through using recycled aggregates in place of NA.

Figure 4.

Relative frequency of social cost of mixtures (volume natural resources m3/m3).

Table 10.

Social costs of mixtures (volume natural resources %/m3).

The best-performing mixture is the FA10 GGBFS45 BFS100 mixture, with 90% confidence that the mixture will have only 44% to 48% of the social cost of the OPC benchmark. This significant saving represents large volumes of natural resources can be preserved by adopting a mixture with both high proportions of SCM and waste aggregate, that is already supported by contemporary rigid airport pavement specifications. The variability in distribution results across all mixtures is minimal, indicating that there is a high degree of predictability of the social cost of mixtures, based on the proportions of waste material use in each defined mixture design.

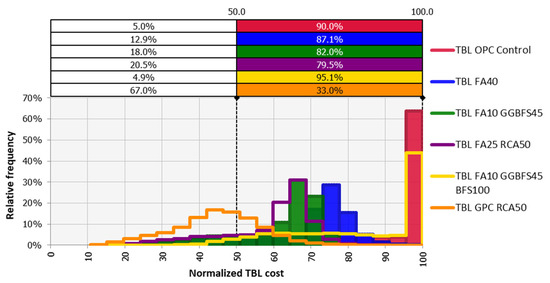

3.4. TBL Costs

Figure 5 shows the distribution of normalized TBL costs across all six mixtures. Table 11 shows the minimum, median, mean and maximum normalized TBL costs, as well as the 90% CI for all mixtures, that corresponds to Figure 4. It is clear that of the six mixtures in the comparison, the GPC RCA50 mixture has the lowest TBL cost, with 67% of results falling below the 90% CI for both the OPC and BFS mixtures. This is driven by strong social and environmental cost performance, despite having the second-highest financial cost profile. The next-best-performing mixtures are FA40, FA10 GGBFS45 and FA25 RCA 50, which are clustered around a mean of 59% to 69% of the TBL cost of the OPC and BFS mixtures, representing significant (30% to 40%) holistic sustainability gains are possible in airport pavement mixtures featuring SCMs and recycled aggregates.

Figure 5.

Relative frequency of normalized TBL cost.

Table 11.

Normalized TBL cost of mixtures.

Interestingly, despite the best social cost performance, the FA10 GGBFS45 BFS100 mixture demonstrates a similar TBL cost profile compared to the OPC benchmark. This again highlights the impact of the highly uncertain financial and environmental cost performance of mixtures containing BFS aggregate in the Australian context, noting the potential for very large transport distances from the single supplier of BFS aggregate to some Australian airports. However, a comparably low minimum TBL cost indicates that competitive performance is possible when using BFS aggregate and further highlights the importance of project-specific TBL analysis to adequately assess the most advantageous constituent material choices available in a given region. More generally, this finding highlights the significance of aggregate transport distance on the overall sustainability of a given concrete mixture.

The normalization method applied (scaling to the maximum) provides a simple and effective basis for comparing the results of this study. However, TBL cost results are inherently contextual because the scale is determined by the maximum of this specific dataset, which itself is influenced by the variability in the distribution inputs for each mixture. Extreme draws in cost during the Monte Carlo simulations can produce high maximum values, which then propagate into the normalized TBL scores and amplify the apparent spread of results. This is highlighted by four of the six mixtures obtaining a maximum TBL cost of 100, indicating scenarios exist where any of these four mixtures could have the highest relative TBL cost. Furthermore, these normalized TBL scores may vary if additional mixtures with different performance profiles or alternative input parameters are introduced. Consequently, the TBL cost outcomes should be interpreted as contextual to this study rather than absolute indicators of sustainability performance for these mixture compositions, with the range reflecting stochastic input variability interacting with the chosen normalization process. As reflected in a recent study by Malefaki, Markatos, Filippatos and Pantelakis [53], the approach used to normalize and aggregate heterogenous sustainability indicators impacts the composite sustainability score, highlighting that different normalization methods or combination techniques used for this study could have resulted in substantially different rankings. Finally, this TBL analysis does not preclude the requirement for robust mixture design and lab trials, a feature of existing specifications, to verify that any mixture made with local materials can reliably meet the strength and durability aspects of the intended design.

4. Conclusions

Based on this theoretical comparison of the TBL cost of various concrete airport pavement mixtures, it was concluded that mixtures allowed by contemporary specifications containing FA, GGBFS and RCA achieved between 30% to 40% mean TBL cost savings compared to the OPC benchmark. The GPC mixture containing RCA showed the strongest overall performance, particularly in reducing embodied emissions (mean reduction 46%) and natural resource conservation (mean reduction 36%), achieving a significant saving of 55% mean TBL cost compared to the OPC benchmark. However, GPC binder systems remain an aspirational option for airport owners, noting GPC binder systems are not yet fully incorporated into standard practice. BFS aggregate can be a sustainable choice, but only if transport distances are comparable to NA, with the findings highlighting the substantial impact aggregate transport distance can have on concrete mixture sustainability, even if low-carbon binders are used. Although normalized TBL costs were sensitive to the input distributions, with resultant rankings highly contextual to this study, the results reaffirm that continued reliance on conservative, OPC-centric pavement specifications may no longer be justified on sustainability grounds. Consequently, this work provides a foundation for jurisdictions still relying on conservative OPC-based specifications to transition toward performance-based rigid pavement specifications that permit carbon reduction and circular economy objectives to be met. The results support a transition toward more progressive and sustainable rigid pavement practice across the aviation sector.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.W.; methodology, G.W.; investigation, L.N.-H.; resources, G.W.; data curation, L.N.-H.; writing—original draft preparation, L.N.-H.; writing—review and editing, G.W.; visualization, L.N.-H.; supervision, G.W.; project administration, G.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT-5 mini for the purposes of grammatical editing. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AUD | Australian Dollars |

| BFS | Blast Furnace Slag |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| CO2 | Carbon Dioxide |

| FA | Fly Ash |

| GGBFS | Ground Granulated Blast Furnace Slag |

| GPC | Geopolymer Cement |

| GWP-t | Total Global Warming Potential |

| LCA | Life Cycle Analysis |

| LCCA | Life Cycle Cost Analysis |

| NA | Natural Aggregate |

| OPC | Ordinary Portland Cement |

| PCC | Portland Cement Concrete |

| RCA | Recycled Concrete Aggregate |

| SCM | Supplementary Cementitious Material |

| SG | Specific Gravity |

| SSD | Saturated Surface Dry |

References

- Newton-Hoare, L.; Jamieson, S.; White, G. Review of the Use of Waste Materials in Rigid Airport Pavements: Opportunities, Benefits and Implementation. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Cement and Concrete Association. Concrete Future-Getting to Net Zero. Available online: https://gccassociation.org/concretefuture/getting-to-net-zero/ (accessed on 7 March 2025).

- Climate Change Authority. Sector Pathways Review; Commonwealth of Australia: Canberra, Australia, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Infrastructure Australia. Infrastructure Market Capacity 2023 Report; Australian Government: Canberra, Ausralia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Global Cement and Concrete Association. Cement Industry Net Zero Progress Report 2024/25; Global Cement and Concrete Association: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- WEF. Sustainable Development: Cement Is a Big Problem for the Environment. Here’s How to Make It More Sustainable. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/stories/2024/09/cement-production-sustainable-concrete-co2-emissions/ (accessed on 18 March 2025).

- Durastanti, C.; Moretti, L. Assessing the climate effects of clinker production: A statistical analysis to reduce its environmental impacts. Clean. Environ. Syst. 2024, 14, 100204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marandi, N.; Shirzad, S. Sustainable cement and concrete technologies: A review of materials and processes for carbon reduction. Innov. Infrastruct. Solut. 2025, 10, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. The Paris Agreement. Available online: https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-paris-agreement (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Barbhuiya, S.; Kanavaris, F.; Das, B.B.; Idrees, M. Decarbonising cement and concrete production: Strategies, challenges and pathways for sustainable development. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 86, 108861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brecha, R.J.; Ganti, G.; Lamboll, R.D.; Nicholls, Z.; Hare, B.; Lewis, J.; Meinshausen, M.; Schaeffer, M.; Smith, C.J.; Gidden, M.J. Institutional decarbonization scenarios evaluated against the Paris Agreement 1.5 °C goal. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 4304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groves, S. Standards to Facilitate the Use of Recycled Material in Road Construction; Standards Australia: Sydney, NSW, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Jamieson, S.; White, G.; Verstraten, L. Principles for Incorporating Recycled Materials into Airport Pavement Construction for More Sustainable Airport Pavements. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, T.; Calmon, J.L.; Vieira, D.; Bravo, A.; Vieira, T. Life Cycle Assessment of Road Pavements That Incorporate Waste Reuse: A Systematic Review and Guidelines Proposal. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dam, T.J.; Harvey, J.; Muench, S.T.; Smith, K.D.; Snyder, M.B.; Al-Qadi, I.L.; Ozer, H.; Meijer, J.; Ram, P.; Roesler, J.R. Towards Sustainable Pavement Systems: A Reference Document; United States Department of Transportation Federal Highway Administration: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Tudor, T.; Dutra, C.J.C. The Routledge Handbook of Waste, Resources and the Circular Economy, 1st ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2020; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Commonwealth of Australia. 2018 National Waste Policy: Less Waste More Resources; Commonwealth of Australia: Canberra, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Jamshidi, A.; Kurumisawa, K.; Nawa, T.; Samali, B.; Igarashi, T. Evaluation of energy requirement and greenhouse gas emission of concrete heavy-duty pavements incorporating high volume of industrial by-products. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 166, 1507–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austroads. Part 4E: Recycled Materials; Austroads Ltd.: Sydney, NSW, Australia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- White, G.; Farelly, J.; Jamieson, S. Estimating the Value and Cost of Australian Aircraft Pavements Assets. In Proceedings of the American Society of Civil Engineers Airfield and Highway Pavements Conference 2021, Virtual Event, 8–10 June 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Airports Association. Airport Pavement Essentials Airport Practice Note 12; Australian Airports Association: Canberra, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- AC 150/5370-10H; Standard Specifications for Construction of Airports. Federal Aviation Administration: Washington, DC, USA, 2018.

- Jamieson, S.; White, G. Defining Australian Rigid Aircraft Pavement Design and Detailing Practice. In Proceedings of the International Airfield and Highway Pavement Conference, Virtual Event, 8–10 June 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Jamieson, S.; Verstraten, L.; White, G. Analysis of the Opportunities, Benefits and Risks Associated with the Use of Recycled Materials in Flexible Aircraft Pavements. Materials 2025, 18, 3036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helsel, M.A.; Rangelov, M.; Montanari, L.; Spragg, R.; Carrion, M. Contextualizing embodied carbon emissions of concrete using mixture design parameters and performance metrics. Struct. Concr. 2023, 24, 1766–1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayasooriya, R. NACOE S67: Future Availability of Fly Ash for Concrete Production in Queensland (2022–24); National Asset Centre Of Excellence (NACOE): Brisbane, QLD, Australia, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, L.H.P.; Nehring, V.; de Paiva, F.F.G.; Tamashiro, J.R.; Galvín, A.P.; López-Uceda, A.; Kinoshita, A. Use of blast furnace slag in cementitious materials for pavements—Systematic literature review and eco-efficiency. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2023, 33, 101030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neville, A.M.; Brooks, J.J. Concrete Technology, 2nd ed.; Prentice Hall: Harlow, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Saha, A.K.; Khan, M.N.N.; Sarker, P.K.; Shaikh, F.A.; Pramanik, A. The ASR mechanism of reactive aggregates in concrete and its mitigation by fly ash: A critical review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 171, 743–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harwalkar, A.B.; Awanti, S.S. Laboratory and Field Investigations on High-Volume Fly Ash Concrete for Rigid Pavement. Transp. Res. Rec. 2014, 2441, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ley, T.M.; Lloyd, Z.; Kang, S.; Cook, D. Concrete Pavement Mixtures with High Supplementary Cementitious Materials Content: Volume 3; Illinois Department of Transportation: Springfield, IL, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, N.B.; Middendorf, B. Geopolymers as an alternative to Portland cement: An overview. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 237, 117455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari Mohd, A.; Shariq, M.; Mahdi, F. Assessment of Geopolymer Concrete for Sustainable Construction: A Scientometric-Aided Review. J. Struct. Des. Constr. Pract. 2025, 30, 03125001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasby, T.; Day, J.; Genrich, R.; Aldred, J. EFC geopolymer concrete aircraft pavements at Brisbane West Wellcamp Airport. In Proceedings of the Concrete Institute of Australia Conference, Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 30 August–2 September 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Tushar, Q.; Bhuiyan, M.A.; Abunada, Z.; Lemckert, C.; Giustozzi, F. Carbon Footprint and Uncertainties of Geopolymer Concrete Production: A Comprehensive Life Cycle Assessment (LCA). C 2025, 11, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, A.; Miller, S.A. Life cycle assessment and production cost of geopolymer concrete: A meta-analysis. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2025, 215, 108018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, M.; Upreti, K.; Vats, P.; Singh, S.; Singh, P.; Dev, N.; Kumar Mishra, D.; Tiwari, B. Experimental Analysis of Geopolymer Concrete: A Sustainable and Economic Concrete Using the Cost Estimation Model. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2022, 2022, 7488254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallah, M.A.; Ghasemzadeh Mousavinejad, S.H. A Comparative Study of Properties of Ambient-Cured Recycled GGBFS Geopolymer Concrete and Recycled Portland Cement Concrete. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2023, 35, 05022002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanijo, E.O.; Kolawole, J.T.; Babafemi, A.J.; Liu, J. A comprehensive review on the use of recycled concrete aggregate for pavement construction: Properties, performance, and sustainability. Clean. Mater. 2023, 9, 100199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alibeigibeni, A.; Stochino, F.; Zucca, M.; Gayarre, F. Enhancing Concrete Sustainability: A Critical Review of the Performance of Recycled Concrete Aggregates (RCAs) in Structural Concrete. Buildings 2025, 15, 1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalline, T.; Snyder, M.; Taylor, P. Use of Recycled Concrete Aggregate in Concret Paving Mixtures; United States Department of Transportation Federal Highway Administration: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Verian, K.; Whiting, N.; Olek, J.; Jain, J.; Snyder, M. Using Recycled Concrete as Aggregate in Concrete Pavements to Reduce Materials Cost; Joint Transportation Research Program, Indiana Department of Transportation and Purdue University: West Lafayette, IN, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piemonti, A.; Conforti, A.; Cominoli, L.; Sorlini, S.; Luciano, A.; Plizzari, G. Use of Iron and Steel Slags in Concrete: State of the Art and Future Perspectives. Sustainability 2021, 13, 556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.D.; Morian, D.A.; Van Dam, T.J. Use of Air-Cooled Blast Furnace Slag as Coarse Aggregate in Concrete Pavements: A Guide to Best Practice; FHA: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Arslan, M.; Kisacik, H. The Corporate Sustainability Solution: Triple Bottom Line. Muhasebe Finans. Derg. 2017, 18–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witte, A.; Garg, N. Quantifying the global warming potential of low carbon concrete mixes: Comparison of existing life cycle analysis tools. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 20, e02832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, A.T.M.; Velenturf, A.P.M.; Bernal, S.A. Circular Economy strategies for concrete: Implementation and integration. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 362, 132486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NSW Government. How to Calculate the Embodied Carbon of a Concrete Mix-Factsheet; NSW Government: Sydney, NSW, Australia, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- EPD Australasia Ltd. Environmental Product Declaration Search. Available online: https://epd-australasia.com/epd-search/ (accessed on 16 May 2025).

- Noller, D.C. Product Carbon Footprint Declaration Wagners EFC Geopolymer Concrete. Available online: https://earthfriendlyconcrete.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/Wagner-EFC-CFD-FINAL-V4.pdf (accessed on 27 May 2025).

- AusLCI. AusLCI Emissions Factors V1.45. Available online: https://www.auslci.com.au/index.php/EmissionFactors (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Vázquez-Calle, K.; Guillén-Mena, V.; Quesada-Molina, F. Analysis of the Embodied Energy and CO2 Emissions of Ready-Mixed Concrete: A Case Study in Cuenca, Ecuador. Materials 2022, 15, 4896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australasian (Iron & Steel) Slag. Blast Furnace Slag Cements & Aggregates: Enhancing Sustainability; Australasian (Iron & Steel) Slag Association: Wollongong, NSW, Australia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bidokhti, P.S. Theory, Application, and Implementation of Monte Carlo Method in Science and Technology; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Palisade Corporation. @RISK 8.9.0 Industrial Edition, version 8.9.0; Palisade Corporation: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Malefaki, S.; Markatos, D.; Filippatos, A.; Pantelakis, S. A Comparative Analysis of Multi-Criteria Decision-Making Methods and Normalization Techniques in Holistic Sustainability Assessment for Engineering Applications. Aerospace 2025, 12, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, G.; Kelly, G.; Fairweather, H.; Jamshidi, A. Theoretical socio-enviro-financial cost analysis of equivalent flexible aircraft pavement structures. In Proceedings of the 99th Annual Meeting of the Transportation Research Board, Washington, DC, USA, 12–16 January 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Van Den Heuvel, D.; White, G. Objective Comparison of Sustainable Asphalt Concrete Solutions for Airport Pavement Surfacing. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Sustainable Infrastructure, Virtual Event, 6–10 December 2021. [Google Scholar]

- DeRousseau, M.A.; Arehart, J.H.; Kasprzyk, J.R.; Srubar, W.V. Statistical variation in the embodied carbon of concrete mixtures. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 275, 123088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabău, M.; Bompa, D.V.; Silva, L.F.O. Comparative carbon emission assessments of recycled and natural aggregate concrete: Environmental influence of cement content. Geosci. Front. 2021, 12, 101235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.