Abstract

As a unit, housing is one of the most important elements affected by social, economic, and cultural changes in every period of human history. In all ages, from ancient times to the present, housing has not only met the need for shelter, but also reflected people’s lifestyles and values and the technological developments of the period. Housing architecture emerges as a type of structure that has been continuously evolving in every period and is affected by the changes experienced by societies. In this study, the idea that houses are not only structural products, but the structures that have become homes for humans, is approached and discussed through concepts such as spatial organization, relationality, accessibility, visibility, density of use, depth, privacy, and belonging. The Yenişehir district in Karabük province, which is thought to have been transformed into design by considering these concepts, also constitutes the focus area of the study idea in this sense. The houses located in the Yenişehir district, which was selected because it contains concrete examples of the modernization efforts of the Early Republican Period of Türkiye and is an example of industrial housing production, have been numerically evaluated within the scope of this study with the data obtained from the space syntax analysis and the depthMapX program (v0.8.0). In this way, it raises the question of whether it is possible to create housing settlements for people in the transition from agricultural society to industrial society without disrupting the socio-cultural structure of society. As a result, it has been seen that the houses in Yenişehir are designed functionally and human-oriented, and they also consider the dynamics of society.

1. Introduction

Karabük is a province located in the western part of Türkiye’s Black Sea Region, notable for its establishment and development within the context of architectural history (Figure 1). Administratively, it comprises a total of 6 districts, 80 neighborhoods, and 277 villages (Table 1) []. In the 1930s, Karabük emerged as one of the significant centers of Türkiye’s industrialization efforts. During the Early Republican Period, as part of national goals to expand industrial enterprises, the foundations of the Demir Çelik İşletmeleri (DÇİ, Iron and Steel Enterprises) were laid, accelerating the city’s development. At that time, Karabük was a small village named Öğlebeli, subordinate to the Safranbolu district. The establishment of DÇİ brought about population growth and economic vitality, transforming the region’s status. Karabük became a township of Safranbolu in 1941 and gained district status on 3 March 1953, through Law No. 6068, with 53 villages annexed to it []. On 6 June 1995, Karabük was declared Türkiye’s 78th province under Law No. 22305 [].

Figure 1.

The location of Karabük on the political map of Türkiye and a map showing its districts (Saraçoğlu Gezer).

Table 1.

The number of districts, neighborhoods, and villages in Karabük province [].

In the Early Republican Period (the first 25 years of the Republic), importance was given to industrialization in Türkiye, and important milestones for industrial initiatives were immediately implemented. As the first step in this context, the Economic Congress (İzmir, 1923) was organized, and the First Five-Year Industrial Plan was implemented. In order to support initiatives to be carried out by the state or individually, the Industrial and Mining Bank was established in 1925, and the rights of entrepreneurs were further strengthened with the Industrial Encouragement Law (Teşvik-i Sanayi Kanunu) in 1927 []. However, as a result of the Great Depression in 1929, the Industrial and Mining Bank had to be dissolved, and as a result, two separate banks were established in 1933, Sümerbank to support industry and Etibank to support mining []. In order to implement the industrial initiatives that needed to be made on behalf of the state, Sümerbank determined seven separate regions that were not yet urbanized but were open to development and started to implement industrial initiatives. (Among the factories of Sümerbank that became the symbolic buildings of the republic are Kayseri Cloth Factory (1935), İzmit Paper Factory (1936), Ereğli Cloth Factory (1937), Nazilli Cloth Factory (1937), Bursa Merinos Factory (1938), Gemlik Artificial Silk Factory (1938), Karabük Iron and Steel Factory (1939), and Malatya Cloth Factory (1939).) The study area, Karabük, is the region determined for heavy industry development among these seven regions, and the housing modernization movements of the newly established state were examined within this scope.

With the Republic’s industrialization drive, Karabük embarked on an urban planning process in which Sümerbank’s urbanization policies played a significant role []. Yenişehir Neighborhood became a turning point in Karabük’s and Türkiye’s history of modern urbanization. The city, shaped by the presence of DÇİ, remains a notable example of planned urbanization, preserving its original planning features to this day (Figure 2a). The Republic’s modern urban planning vision included the construction of housing for workers during the establishment of DÇİ. In 1938, housing became a pressing issue for approximately 400 brick workers from Artvin and Erzurum as well as for British engineers involved in the factory construction. Temporary solutions were devised, such as accommodating workers in nearby villages and lodging engineers in newly built hotels in Safranbolu’s Kıranköy area. However, this highlighted the need for a long-term settlement policy [].

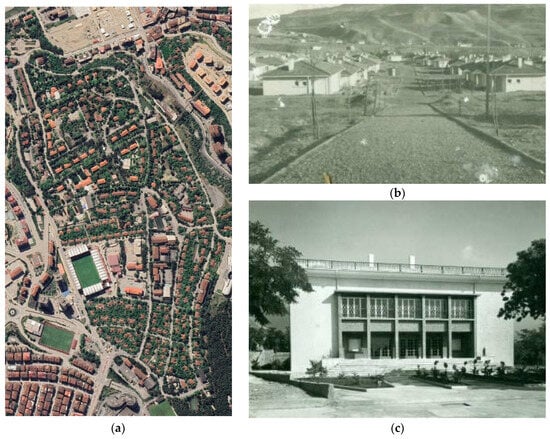

Figure 2.

(a) Aerial photograph of the Yenişehir district. (b) View of workers’ houses in 1940. (c) Yenişehir cinema in 1964.

To address the housing need, renowned urban planner and architect Henri Prost was commissioned, and in 1938, plans for the Yenişehir neighborhood were prepared. (Due to disasters such as fire and flooding in the archives, there is no original plan prepared by Henri Prost today. There is an official letter about the money paid to him by the prime minister of the time for the plan’s drawing.) With the development of this planned settlement, Yenişehir marked the beginning of Karabük’s modern urbanization journey (Figure 2b). Sümerbank not only focused on housing but also addressed the social and cultural needs of workers and their families through comprehensive planning []. Various facilities and services were established to improve workers’ living standards, enhance productivity, and foster loyalty to the institution (Figure 2c). These included healthcare and educational, cultural, and religious facilities such as hospitals, nurseries, schools, a public house, a cinema, clubs, a guesthouse, a hotel, and a mosque. Additionally, the neighborhood featured sports fields, playgrounds, parks, a garden with a pool, public baths, and marketplaces.

In addition to these amenities, the residential structures in Yenişehir embraced the modern architectural style of the time. Sümerbank organized housing according to social class, creating a hierarchy from workers’ pavilions to managers’ residences. The houses were planned to meet the needs of their occupants and provide a comfortable living environment. At the neighborhood entrance were houses designated for the general manager and guests, followed by residences for managers, engineers, and skilled workers. Dormitories for single workers were built near social facilities but away from family housing. The homes’ design aimed to enhance workers’ comfort and social lives, with gardens allowing families to engage in agricultural activities and adapt to urban life [,,,].

The construction activities in Karabük began in 1936 with 6 cubic-style apartment buildings and a 150-bed dormitory for single workers. These efforts accelerated between 1939 and 1948 with the construction of 920 residences. Sümerbank’s urban planning extended beyond housing to include infrastructure, green spaces, sewage systems, and water facilities. For example, Yenişehir adopted a central heating system, a significant innovation for the period.

Today, Yenişehir neighborhood retains its importance as a modern residential area. In 1996, the High Council of Monuments designated it as a protected urban and natural site. (Karabük province, Central district, Yenişehir Neighborhood Natural Protected Area was registered as a “Natural Protected Area—Sustainable Protection and Controlled Use Area” with the Approval of the Ministry dated 21 October 2019 and numbered 246753). Located north of the factory area and at the foothills of Karabük Urban Forest, Yenişehir continues to serve as a social, cultural, and economic center. It also has the distinction of being the region that still exists and has been used for years with its original function among the seven regions determined by Sümerbank.

Despite wars and economic crises, the Early Republican Period prioritized decisions valuing society and individuals. Through industrialization efforts, modern residential plans were implemented in various regions of the country, with settlements that surpassed contemporary standards. This study focuses on Karabük Yenişehir’s housing production, emphasizing the principles that guided its development. By analyzing and quantifying these historical, architectural, sociological, and cultural values, the study aims to encourage further research into Yenişehir. Meanwhile, the study analyzes whether the residential settlements produced in the transition from agricultural society to industrial society were planned in accordance with the socio-cultural structure of the society. Finally, unlike previous studies, it also includes archive studies for plan types and presents study findings with numerical values.

2. The Concept of Housing and Its Development in Türkiye

Examples of vernacular architecture hold significant value, as they illuminate both the design principles and the way of life of their respective periods. The concept of housing is an interdisciplinary subject that continues to be explored across various fields. Understanding and improving the quality of life in urban areas necessitates considering user demands, which, in turn, sheds light on the underlying reasons for ongoing transformations. Through this approach, it becomes possible to examine how factors such as the demand for change, adaptation to transformation, or being forced into change evolve at both the city-wide and regional scales.

For humans, the primary source of motivation is the fulfillment of the physiological needs essential for survival. According to Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, the group of basic necessities—including eating, drinking, and resting—is followed by the need for safety, which encompasses the requirement for shelter []. Since the earliest periods, humans, inherently vulnerable to natural conditions, have sought to address this need by constructing shelters. However, in contemporary society, the production of housing—broadly categorized as shelter—is no longer solely aimed at fulfilling this basic necessity. While shelter remains a fundamental need, a dysfunctional dwelling fails to contribute to the well-being and happiness of its inhabitants.

The theme of the fourth meeting of the International Congress of Modern Architecture (CIAM), held in Athens in 1933 [], was designated as “The Functional City”. As a result of the determinations made regarding residential areas in urban planning, several principles influencing housing design were outlined. Among the suggested principles, which were mainly related to physical factors, a technological dimension was also emphasized. The importance of land conditions such as topography, climate, and sunlight were emphasized when planning residential areas.

As an architectural historian, Sibel Bozdoğan [] defines architecture as a “carrier of civilization” when evaluating it in the context of housing and life. In making this definition, Bozdoğan includes not only public buildings but also private homes, which are described as the “most intimate family space”. This perspective suggests that all changes in family life can be interpreted as internal cultural transformations. Preferences in rooms, furniture, colors, and patterns within homes continuously evolve over time.

Professor Nazan Kırcı [] defines architecture as the “art of compromise” and emphasizes that the contradictions resulting from changing human demands stem from the differences between the past and the present. He argues that the resolution to this contradiction lies in architectural history. However, this does not imply a mere repetition of the past; rather, it underscores the importance of acknowledging experiences, identity, and collective memory. Understanding these factors provides insights into how individuals shape their living environments based on their chosen lifestyles.

Philosopher–writer Yörükan [] also adds the concept of “natural conditions” to urban development discussions. He argues that with the growth of urbanization, nature has increasingly been disregarded. As a result of uncontrolled expansion, cities experience not only physical deterioration but also psychological strain on their inhabitants. Urban dwellers, having severed their connection with nature, experience alienation from their authentic selves, lose sensitivity to the allure of the city, and may begin to view their private living spaces—originally intended as shelters—as status symbols.

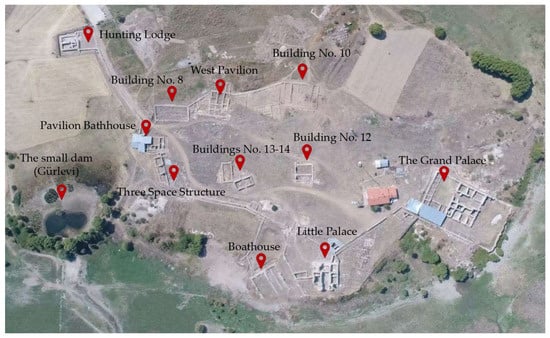

Throughout history, the selection of settlement sites has been influenced by factors such as proximity to water resources, food availability, suitability for settlement, and security. Prehistoric settlements and housing developments identified in Anatolia reflect these basic factors. The first known settlement structure in Anatolia is found in Çayönü (Diyarbakır), while the oldest known settlement is Çatalhöyük (Konya), and the oldest known religious center is Göbeklitepe (Şanlıurfa). Before settling in Anatolia, Turkish tribes adopted a nomadic and semi-nomadic lifestyle, which led to significant advances in woodworking. When they migrated from Central Asia, they combined their accumulated knowledge and experience with the architectural traditions they encountered in Anatolia and became familiar with stone as a material. The Kubadabad Palace (Figure 3) in Beyşehir, Konya, an example of civil architecture, has an important place in the architectural literature. The name “Kubadabad” means “the place revived and developed by Keykubad”, and its complex structure reflects the architectural advances of the period [].

Figure 3.

Kubadabad palace complex (The author has placed bookmarks on the existing image), Konya/Türkiye [].

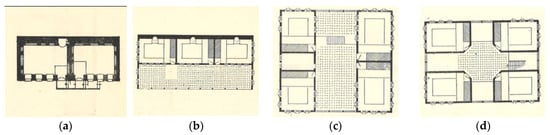

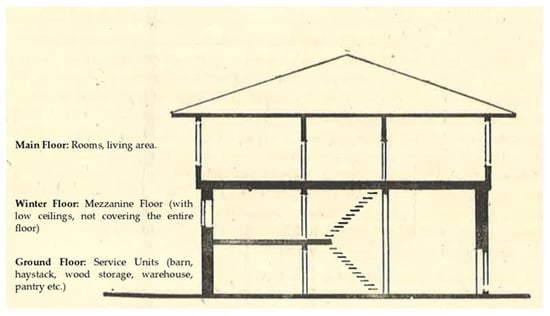

Numerous examples of civil architecture from this period have survived to the present day, and the “Turkish House” plan type was implemented not only in the Anatolian region but also in various locations across Asia and Europe, where the empire extended its borders. The first systematic study on the Turkish house, which is also referenced in contemporary research, is Sedad Hakkı Eldem’s book titled Türk Evi Plan Tipleri (Turkish House Plan Types), published in 1954 []. In this book, Eldem discusses the general characteristics, distinctive features, production processes, and deterioration causes of the Turkish house. Based on approximately 1500 measured drawings, he categorizes Turkish houses into four plan types (Figure 4) according to their spatial organization. He notes that the Turkish house is typically a single-story structure, while in multi-story examples, each floor is allocated based on its functional role within the dwelling (Figure 5). Accordingly, the ground floor is in direct connection with the garden and accommodates service units. This level does not serve as a living space, and the facades facing public areas remain solid and windowless. Between the ground floor and the main living floor, there is an intermediate level, which is lower in height than the primary floor and is also referred to as the “winter floor”. The main floor, where the rooms are located, serves as the primary living area and defines the house’s plan type.

Figure 4.

Sedad Hakkı Eldem’s Turkish house plan type examples (Reprinted from Ref. []). (a) Plan type without sofa. (b) Plan type with outer sofa. (c) Plan type with inner sofa. (d) Plan type with middle sofa.

Figure 5.

Sedad Hakkı Eldem’s Turkish house section (Adapted with Ref. []).

Until this period, individual efforts and employer–master relations were seen in housing production as architecture without architects. In the Republican Era, various housing policies were introduced to regulate residential production. This period emphasized the stylistic features inherent to Turkish architecture. However, as this movement did not have a long-lasting impact, modernization efforts emerged in various aspects of society alongside industrialization. During the modernist architectural period, geometric forms were predominantly preferred, functionality became a key design principle, and the technological advancements of the era were effectively utilized [].

The rapid population growth of the 1960s led to an urgent need for housing solutions, prompting the development of mass housing projects. These projects, initially carried out by the state or through housing cooperatives, later evolved into large residential complexes. Particularly from the 2000s onward, gated communities have become increasingly prevalent. These settlements, protected by security measures and restricting access to outsiders, function as self-contained urban environments, often incorporating education, healthcare, sports, business, and shopping facilities, as seen in the so-called “space city” developments [].

After briefly reviewing the history of housing in Anatolia, this section of the study focuses on the Yenişehir district in Karabük, an area of significant importance in the city’s housing production history during the Early Republican Period. Yenişehir serves as an exemplary case of modernization through industrial housing production. This evaluation of Yenişehir is expected to provide insights into the changes introduced in housing during the Republican Era and the evolving perspective on human living conditions. By considering the notion that living spaces reflect the socio-cultural characteristics of their respective periods, this study aims to analyze the housing movements of the era from a contemporary perspective.

3. Analysis of Residences in Yenişehir District Using the Space Syntax Method

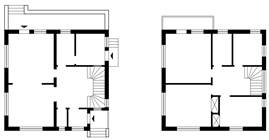

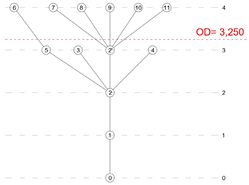

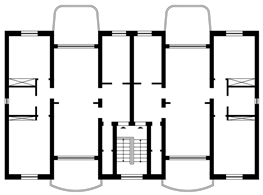

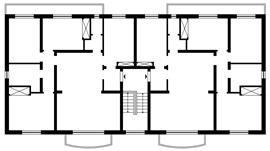

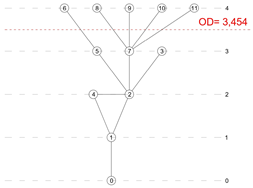

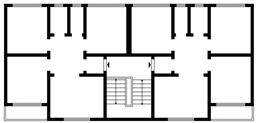

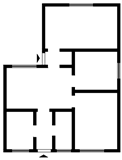

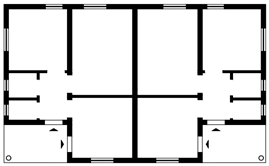

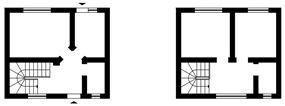

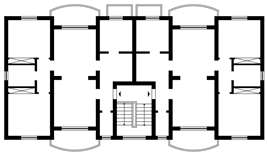

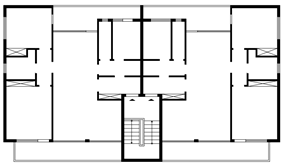

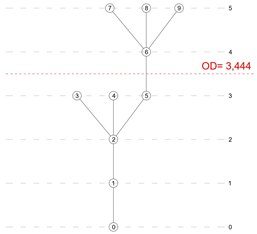

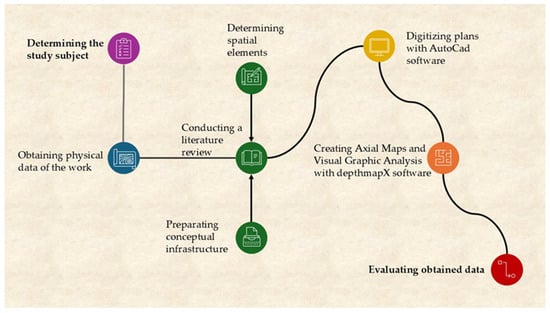

Within the scope of the research method (Figure 6), the plans of the houses in the Yenişehir district in the archive were obtained, and fifteen existing plans were identified. Since it was seen that some plans were derived from each other, three main headings were determined in order to scan the plans with similar features: the number of floors of the building, the number of flats, and the number of entrances to the flat. The number of floors and flats of the building can be used to understand whether it is a detached or an apartment building, and the number of entrances to the flat can give an idea about the interaction between the exterior and interior spaces of the flat. In this context, nine typologies emerged. There are also differences in the number of rooms and square meters among these types, and these details are presented in Table 2. Four of the typified structures are detached houses and five are apartments. Two of the detached houses are single-story, and two are duplex structures.

Figure 6.

Flow chart for the implementation of the research method.

Table 2.

Features of selected buildings from Yenişehir.

In this study, it was decided to use the space syntax method for analysis. The determined study area has been the subject of many studies, but no study has conducted a study on space analysis. This selected method analyzes how spaces are organized, their effects on people, and how they direct social interaction. While functions such as living, eating, and sleeping were carried out in the same room with portable changes before the Republic, specialization (such as living area, bedroom, dining room, study room) is seen in rooms with the Republic. This allows for the analysis of houses not only in terms of structure but also by including the human factor, which is the main purpose of the study.

This method was first developed and used by Bill Hillier and Julienne Hanson in the 1970s based on human movement and visual perception []. This method attracts the attention of architects because it can be used both at urban and building scales [,,]. As did Saraçoğlu Gezer and Sultan Qurraie, we had previously chosen to use this method in our study of the square experience in Karabük province []. This method, which has been preferred for many urban studies in a similar form, is preferred in all studies requiring graphical network analysis because it can be worked on an urban scale and because it is a virtual brain that can test the relationships between each of the elements in the city [,,]. It is a method that can be used at the residential scale [,,], public building scale [,,], and even landscape planning [,,], in addition to the urban scale.

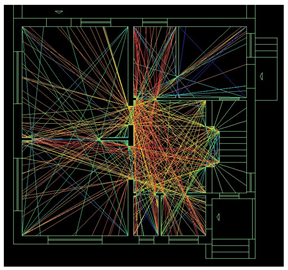

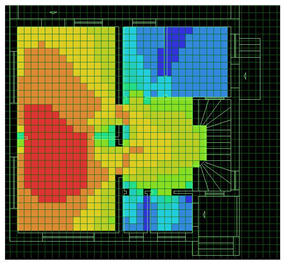

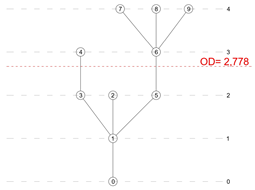

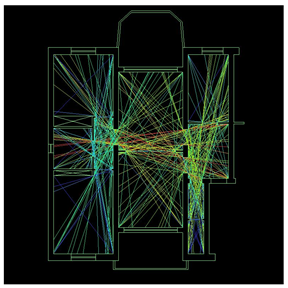

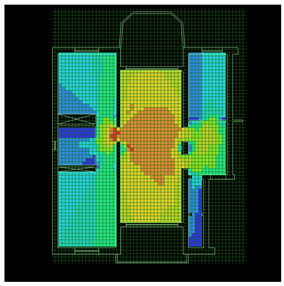

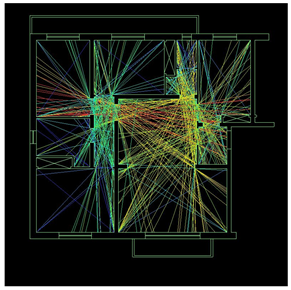

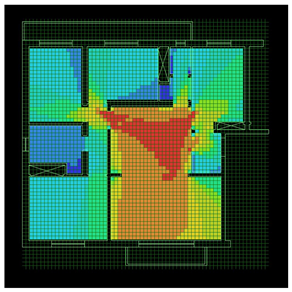

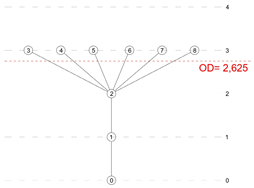

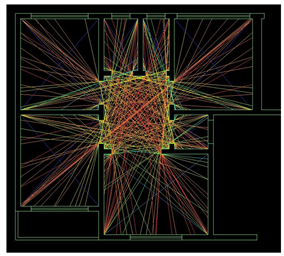

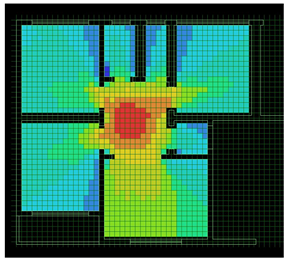

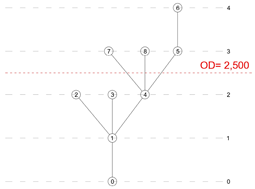

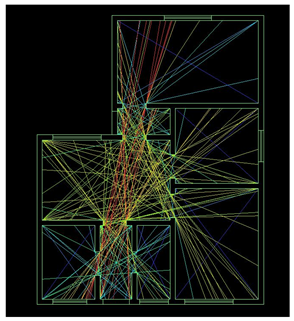

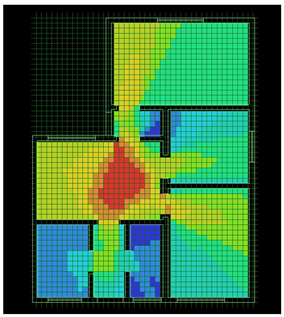

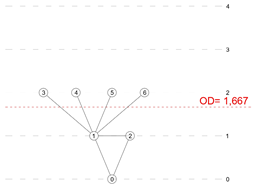

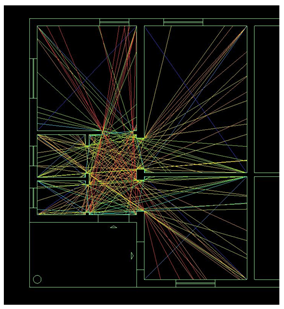

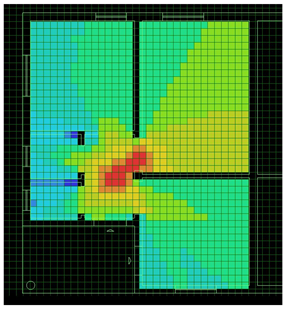

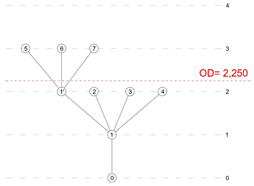

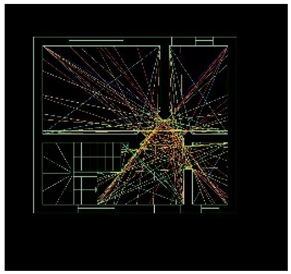

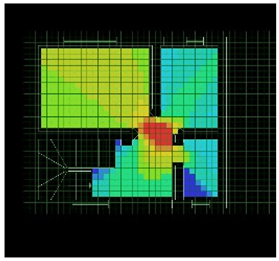

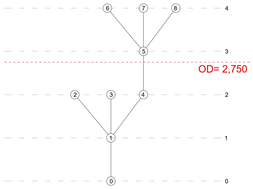

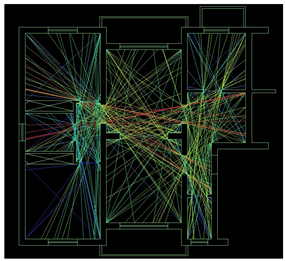

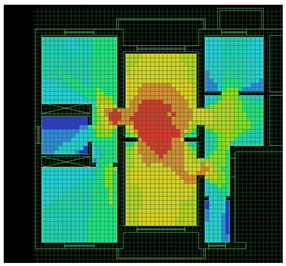

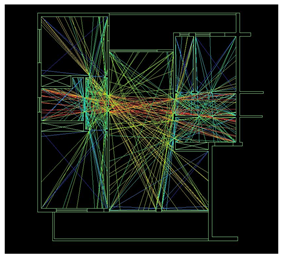

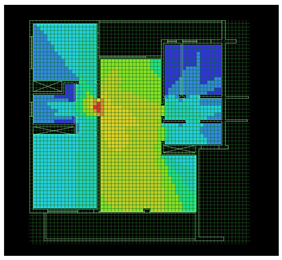

Space syntax is a method used to analyze spatial configurations and how they affect human movement, social interactions, and accessibility. Two key measures in space syntax analysis are connectivity and integration, both of which provide insight into the spatial properties of a given environment []. In this study, space syntax analysis was utilized to examine the spatial configuration of residential buildings. This analysis allows for the mapping of spatial transitions and depth while also enabling the calculation of integration values []. Furthermore, as a continuation of the space syntax analysis, connectivity and visual graph analyses were conducted using the depthMapX software (Table 3).

Table 3.

Plans and analyses of the selected buildings from Yenişehir.

Connectivity analysis, which is used to measure how many connections an area has to adjacent areas, is used to calculate the number of neighboring areas that can be accessed from a given location. The resulting values are evaluated to determine the local accessibility of an area [,]. Here, high connectivity indicates that an area is easily accessible and has multiple entry points, while low connectivity values indicate that an area is more isolated or closed. In the case of housing, spaces with a high level of connectivity can be said to have multiple doors opening to different rooms and a central gathering area, while spaces with a low level of connectivity can be said to have only one entrance and have limited access.

The integration value is a general measure that shows the degree to which a space in a system can be reached from all other spaces. It calculates the spatial hierarchy as a whole by the average number of steps required to reach a certain space from all other spaces in the system [,]. Here, high integration values indicate that an area is frequently accessible and more central, while low integration values indicate that an area is rarely accessible and isolated. In the case of housing, it can be said that spaces with a high level of integration value are centrally located and efficiently connected to more than one room, while spaces with a low level of integration value are more private and less accessible.

In all these housing units built in Yenişehir as part of industrial-based residential production, engineers, civil servants, and workers employed at various levels in the factory reside. Although some housing groups have been demolished due to structural safety concerns, many of them continue to function as residences. The data obtained through digitization and analysis reveal that these housing units feature timeless and modern layouts capable of adapting to changing living conditions (Table 4). It has been observed that in all housing types—including single-story detached houses, two-story detached houses, two-story apartment buildings, and four-story apartment buildings—garden use is prioritized, parking spaces are allocated for vehicle owners, basement storage areas are included in apartment-type structures, and while individual housing arrangements are generally preferred, examples of row houses and twin houses can also be found.

Table 4.

Connectivity and integration data related to the identified structures.

4. Results

Within the scope of architectural history, civil architecture holds as much significance as public buildings, as it provides insights into both the design approach of a given period and the lifestyle it reflects. Just as human history extends far into the past, the history of housing follows a similarly long trajectory. Throughout historical processes, every social transformation has led to changes in societal thought and ways of living, which have, in turn, directly influenced the design and organization of private residential spaces.

Although the primary function of housing is to provide shelter, in contemporary society, it has also become a symbol of social status. Understanding how this transformation is perceived by users and measuring their level of participation in urbanization processes should be planned by local governments. Neighborhoods that differentiate themselves through housing production should be identified as key elements shaping urbanization. Rather than introducing new concepts in housing studies, it is essential to prioritize the accurate use of existing terminologies. Since concepts serve as tools of communication, their correct application is directly linked to a proper understanding of society.

Based on this perspective, the Yenişehir district in the central province of Karabük was selected as the study area due to its construction in line with the industrialization policies of the Early Republican Period, its role as a pioneer in the modernization movements of the Republic, and its significance in housing production related to industrial development. All necessary plans for the analysis of the area were digitized using archival resources from Karabük Iron and Steel Industry and Trade Inc. (KARDEMİR). In addition, the houses identified and included in the study were observed on site, and the use of the houses was examined with the permission of the people living in the houses.

An examination of these housing types reveals that living spaces are more prominently positioned, while bedrooms are located in more secluded areas. In Type A and Type B, a separate night corridor provides access to the bedrooms. During the initial design phase, the separation of living rooms and sitting rooms was a deliberate choice, but in contemporary usage, these two functions have merged into a single living area, eliminating the need for an additional sitting room. The spatial organization of houses varies according to different user needs. In cases where an additional bedroom is required, a room originally designated as a sitting room may be converted into a child’s bedroom, while spaces originally intended for work or guest accommodations may be repurposed as additional sleeping areas. In Type C, bedrooms have been moved entirely to the upper floor, ensuring maximum privacy, while shared spaces such as the living room, kitchen, and bathroom are concentrated on the ground floor.

The conducted analyses demonstrate that the highest connectivity and visibility values in residential floor plans are found in living spaces, confirming that these areas have been strategically positioned for optimal functionality and spatial relationships. The placement of bedrooms in single-floor residences accessible through a separate corridor, and their relocation to upper floors in two-story residences, aligns with privacy needs while also enhancing security within the home.

5. Conclusions and Discussion

This study examines residential buildings in one of the seven regions where industrial housing production was carried out in the Early Republican Period of Türkiye. This region, located in Karabük province and called Yenişehir (Turkish meaning ‘new city’), is the only surviving residential area that continues to be used with the same function as the day it was built. Sümerbank, which carried out the construction process, determined criteria such as suitability for climate, topography, and easy access to building materials for all regions. The aim of the housing settlements planned in the seven different regions was to integrate a society that made a living from agriculture into industry and to have modern living standards. While doing this, no one was suddenly separated from the land. It planned houses with gardens in accordance with horizontal architecture suitable for human scale.

The changing social structure with the declaration of the Republic brought modernization in housing. With the advancement of technology, sanitary and heating installations can also be seen in these structures built in the 1930s. The examination of these structures, which were pioneers in their time, is important for understanding the development of housing history. The study examines the residential structures in the area and shows how changing residential demands are reflected spatially and how users respond to these transformations.

Research also reveals that despite the changes experienced with modernization, attention is paid to the importance given to living spaces culturally. In analyses based on human movements, the spaces most intensively used and most related to all other units are always in living spaces. Living spaces are a socializing space for family members returning from work and school to get together in the evenings and spend time with relatives and friends on weekends. It is an important notion for individuals and families in socio-cultural terms.

In this context, it is very important to integrate user perspectives into urban planning decisions. Therefore, user demands should be taken seriously. It is recommended to conduct survey studies to evaluate the extent to which residential areas fulfill their goals in line with the developing urbanization dynamics.

Author Contributions

A.M.S.G.: Conceptualization, methodology, software, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, writing—original draft preparation, visualization. A.E.B.E.: Conceptualization, validation, writing—review and editing, supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

This study was prepared by Ayşe Merve Saraçoğlu Gezer within the scope of her doctoral thesis, which is being prepared at Karabük University Graduate Education Institute, under the supervision of Ayşen Esra Bölükbaşı Ertürk. We would like to thank KARDEMİR (Karabük Iron and Steel Works Factory), Industry and Research Project Manager Zeren KARASLAN, and institution employees Mehmet Gökhan KARABACAK, Beyazıt ERER, Elif IŞIK ULUÇAY, and Şaban ATEŞOĞLU for their interest in the archive studies and the value they added to the work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Adress Based Population Registration System, Turkish Statistical Institute (Adrese Dayalı Nüfus Kayıt Sistemi, Türkiye İstatistik Kurumu). Available online: https://biruni.tuik.gov.tr/medas/?kn=95&locale=tr (accessed on 25 December 2024).

- Türkiye—Legal Gazette, (T.C. Resmi Gazete). Yeniden 22 Kaza Kurulması Hakkında Kanun, No: 8349, 3 March 1953. Available online: https://www.resmigazete.gov.tr/arsiv/8349.pdf (accessed on 23 January 2025).

- Türkiye—Legal Gazette, (T.C. Resmi Gazete). Sekiz İlçe ve Üç İl Kurulması ve 190 Sayılı Kanun Hükmünde Kararnamenin Eki Cetvellerde Değişiklik Yapılması Hakkında Kanun Hükmünde Kararname, No: 22305, 6 June 1995. Available online: https://www.resmigazete.gov.tr/arsiv/22305.pdf (accessed on 23 January 2025).

- Türkiye—Legal Gazette, (T.C. Resmi Gazete). Teşvik-i Sanayi Kanunu, No: 608, 15 June 1927. Available online: https://www.resmigazete.gov.tr/arsiv/608.pdf (accessed on 23 January 2025).

- Türkiye—Legal Gazette, (T.C. Resmi Gazete). Sümerbank Kanunu, No: 2424, 11 June 1933. Available online: https://www.resmigazete.gov.tr/arsiv/2424.pdf (accessed on 23 January 2025).

- Sümerbank Construction Technical Committee. Sümer Bank Amele Evleri ve Mahalleleri, Arkitekt, 1944, No: 1944-01-02, pp. 9–13. Available online: http://dergi.mo.org.tr/dergiler/2/118/1344.pdf (accessed on 30 December 2024).

- Kütükçüoğlu, M. Türkiye’nin İlk Ağır Sanayi Kenti Karabük; Karabük Governorship Publications: Karabük, Türkiye, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Çabuk, S.; Demir, K.; Gökyer, E. Cumhuriyet’in Yeni Kenti Karabük’ün 1937–1988 Dönemi Mekansal Gelişimi ve Şehir Planları, Karabuk University. J. Inst. Soc. Sci. 2016, 2, 20–39. Available online: https://dergipark.org.tr/tr/pub/joiss/issue/30788/323557 (accessed on 14 February 2025).

- Öktem, S. Türkiye Cumhuriyeti’nde Modernleşme Hareketi; Karabük Demir Çelik Fabrikaları Yerleşim Örneği; İstanbul Technical University Institute of Science: İstanbul, Türkiye, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kaya, S. İdeoloji, Gündelik Yaşam Pratikleri ve Mekan Etkileşiminde Karabük Demir Çelik Fabrikaları Yerleşiminden Öğrendiklerimiz. Master’s Thesis, Gazi University Institute of Science, Ankara, Türkiye, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Onur, B. Endüstri Kenti Karabük’ün Modern Mahallesi Yenişehir’de Konut Tipolojileri. Eur. J. Sci. Technol. 2021, 23, 666–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslow, A. A Theory of Human Motivation; Sublime Books: Floyd, VA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Mumford, E. CIAM urbanism after the Athens charter. Plan. Perspect. 1992, 7, 391–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozdoğan, S. Modernism and Nation Building: Turkish Architectural Culture in the Early Republic; University of Washington Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Kırcı, N. Mimarlıkta Deja Vu. Online J. Art Des. 2018, 6/1, 29–38. [Google Scholar]

- Yörükan, T. İnsanca Yaşamak İçin Şehir ve Konut; Babil Publishing: Ankara, Türkiye, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Head of Excavations at Kubadabad Palace Complex. Available online: https://www.kubadabad.com/kazi-calismalari (accessed on 4 December 2024).

- Eldem, S.H. Türk Evi Plan Tipleri; Istanbul Technical University Faculty of Architecture Publications: İstanbul, Türkiye, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Kuran, A. Çağdaş Mimaride Madde ve Ruh: XX. Yüzyılda Batı Mimarisiyle Türk Mimarisinin Gelişmesi Hususunda Mukayeseli Bir Çalışma, Selçuklular’dan Cumhuriyet’e Türkiye’de Mimarlık; Türkiye İş Bankası Kültür Yayınları: İstanbul, Türkiye, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Erginöz, M.A. İlk Çağdan Günümüze Mimarlık ve Şehircilik Tarihi; Arion Publishing: İstanbul, Türkiye, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hillier, B.; Handson, J. Social Logic of Space; Cambridge Unıversity Press: London, UK, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Yamu, C.; van Nes, A.; Garau, C. Bill Hillier’s Legacy: Space Syntax—A Synopsis of Basic Concepts, Measures, and Empirical Application. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.; Claramunt, C. Integration of Space Syntax into GIS: New Perspectives for Urban Morphology. Trans. GIS 2002, 6, 295–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penn, A.; Turner, A. Space Syntax Based Agent Simulation. In Pedestrian and Evacuation Dynamics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Gezer, M.S.; Qurraie, B.S. Karabük Kent Meydanı’ndaki “Meydan” Deneyimini Mekan Dizimi Yöntemi ile Değerlendirme. Uluslararası Doğu Anadolu Fen Mühendislik Ve Tasarım Dergisi 2021, 3, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askarizad, R.; Lamíquiz Daudén, P.J.; Garau, C. The Application of Space Syntax to Enhance Sociability in Public Urban Spaces: A Systematic Review. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2024, 13, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughan, L. The Spatial Syntax of Urban Segregation. Prog. Plan. 2007, 67, 199–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Nes, A.; Yamu, C.; Van Nes, A.; Yamu, C. Space syntax applied in urban practice. In Introduction to Space Syntax in Urban Studies; Springer: Cham, Germany, 2021; pp. 213–237. [Google Scholar]

- Hillier, B.; Hanson, J.; Graham, H. Ideas Are in Things: An Application of the Space Syntax Method to Discovering House Genotypes. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 1987, 14, 363–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, P.C. Space Syntax Analysis of Central Inuit Snow Houses. J. Anthropol. Archaeol. 2002, 21, 464–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandyopadhyay, A.; Merchant, A.N. Space Syntax Analysis of Colonial Houses in India. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 2006, 33, 923–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, F.A.; Rafeeq, D.A. Assessment of Elementary School Buildings in Erbil City Using Space Syntax Analysis and School Teachers′ Feedback. Alex. Eng. J. 2019, 58, 1039–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Huang, J.; Yang, L. From Functional Space to Experience Space: Applying Space Syntax Analysis to a Museum in China. Int. Rev. Spat. Plan. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 8, 86–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Qi, Y.; Wang, C. An Analysis of the Spatial Characteristics of Jin Ancestral Temple Based on Space Syntax. Buildings 2024, 15, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, A.H.; Omar, R.H. Planting Design for Urban Parks: Space Syntax as a Landscape Design Assessment Tool. Front. Archit. Res. 2015, 4, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascensão, A.; Costa, L.; Fernandes, C.; Morais, F.; Ruivo, C. 3D Space Syntax Analysis: Attributes to be Applied in Landscape Architecture Projects. Urban Sci. 2019, 3, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pafka, E.; Dovey, K.; Aschwanden, G.D. Limits of Space Syntax for Urban Design: Axiality, Scale and Sinuosity. Environ. Plan. B Urban Anal. City Sci. 2020, 47, 508–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariza-Villaverde, A.B.; Jimenez-Hornero, F.J.; Gutierrez de Rave, E. Multifractal analysis of axial maps applied to the study of urban morphology. J. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2013, 38, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, A. DepthMap: A Program to Perform Visibility Graph Analysis. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Symposium on Space Syntax, Georgia Institute of Technology, Atlanta, GA, USA, 7–11 May 2001; Available online: https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=d940499fc935708b6d5f069c36a8b6a2069894c7 (accessed on 25 February 2025).

- Dettlaff, W. Space Syntax Analysis–Methodology of Understanding the Space. PhD Interdiscip. J. 2014, 1, 283–291. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/45350775/Space_syntax_analysis_methodology_of_understanding_the_space (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- Can, I.; Heath, T. In-Between Spaces and Social Interaction: A Morphological Analysis of Izmir Using Space Syntax. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2016, 31, 31–49. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/43907366 (accessed on 30 January 2025). [CrossRef]

- Teklenburg, J.A.F.; Timmermans, H.J.P.; Van Wagenberg, A.F. Space Syntax: Standardised Integration Measures and Some Simulations. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 1993, 20, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.; Claramunt, C.; Klarqvist, B. Integration of Space Syntax into GIS for Modelling Urban Spaces. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2000, 2, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).