Abstract

With the acceleration of urbanization, the surge in urban population led to disorder in urban characteristics and appearance, triggering a conflict between Xiangchou and rapid urbanization. This study selected Xiaoyaojin Park in Hefei as a case study and, based on Kevin Lynch’s “Image of the City” theory, divided urban spatial elements into five categories: Paths, Edges, Districts, Nodes, and Landmarks. By using eye-tracking technology, this study compared and analyzed the visual preferences of local students in Hefei (Xiangchou) and non-local students (non-Xiangchou) for urban elements, and explored the elements that carried Xiangchou through semi-structured interviews. This research found that there were significant differences in visual behavior between the two groups, with the non-Xiangchou group spending more time looking at edge elements, while the Xiangchou group showed more pronounced visual differences concerning Landmarks and Nodes. Nevertheless, Landmarks served as an important carrier of Xiangchou for both groups. The findings provide a new perspective on urban renewal and transformation, emphasizing the need to start from the emotions of residents, and to embed or preserve urban memory points, in order to enhance urban recognizability.

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

With the progress of globalization and rapid urbanization, the faces of cities have undergone earth-shaking changes. Xiangchou emotions, as an emotional bond connecting the past with the present, have gradually become an important issue that cannot be ignored in urban studies. When people discuss Xiangchou, they often think of the countryside, which is probably related to China’s long-standing rural social attributes. However, according to the “Statistical Bulletin of the People’s Republic of China on National Economic and Social Development in 2023” released by the National Bureau of Statistics, by the end of 2023, the urbanization rate of the permanent population nationwide was 66.16% [1]. Nowadays, people’s hometowns are more often in cities rather than in the countryside. However, due to the large scales and dense populations of cities, the frequent changes in residents’ places of residence often make it difficult for residents to establish a strong sense of belonging in cities. In addition, the planning patterns of urban residential areas often hinder effective communication between neighbors, further intensifying the emotional deficiency of residents.

After the founding of the People’s Republic of China, Hefei experienced rapid urban development. The urban area expanded from 5 square kilometers in 1949 to 1339 square kilometers in 2024, and the population surged from 50,000 to 10 million. In just 70 years, both space and population increased by a factor of 100. Similarly, Chicago in the United States underwent rapid urbanization from the 19th to the 20th century, with its population also increasing by a factor of 100. Chicago places a strong emphasis on the preservation of historical buildings and neighborhoods, such as Millennium Park and Willis Tower. These Landmarks not only carry profound historical and cultural significance but also serve as important emotional anchors for the city’s residents.

Kevin Lynch, in his classic work “The Image of the City”, proposed the theory of the five elements of the city based on his research into how urban residents perceive and understand urban spaces. The theory suggests that the complexity of urban spaces can be simplified and understood through five basic elements: “Edges”, “Districts”, “Nodes”, “Landmarks”, and “Paths”. These elements help people construct a cognitive map of the city. In light of this, this study selected part of Hefei’s iconic landscape, Xiaoyaojin Park, as a research sample and meticulously categorized its spatial elements according to the theory of the five elements of the city.

Xiangchou emotions, as a universal human experience, have a complex interplay with the visual perception of urban elements. Eye-tracking technology provides scientific methodological support for exploring people’s visual preferences and emotional responses; existing research has preliminarily revealed the impact mechanism of Xiangchou emotions on urban landscape preferences, but it is mostly concentrated on macro-level theoretical analysis and lacks in-depth studies between specific urban elements and micro-level individual perceptions. Currently, there is a lack of research that combines eye-tracking technology with Xiangchou emotions to deeply explore their role in the perception of visual preferences for urban elements. Therefore, this study attempts to discuss Xiangchou in cities within the framework of the five elements of urban imagery, selecting people with different backgrounds of Xiangchou emotions as research subjects and capturing their visual preference data when viewing images of the five urban elements through eye-tracking technology.

The purpose of this study is to explore the relationship between urban structure and Xiangchou emotions and to clarify the elements that can carry Xiangchou by comparing the visual differences between groups with and without Xiangchou feelings, thereby providing new ideas for urban renewal and protection from the emotional perspective of residents. To this end, first, eye-tracking methods are used to record the visual behavior characteristics of two groups of subjects with different emotional backgrounds, and then semi-structured interviews are conducted to evaluate the ability of urban elements to serve as carriers of Xiangchou, helping to interpret the objective physiological perception data from eye-tracking, with mutual verification between the two.

This study not only helps to reveal the specific manifestations of Xiangchou emotions at the visual level and their impact mechanisms on the perception of urban elements, but also provides new perspectives and theoretical support for urban design and planning. By optimizing the layout of urban elements, we can enhance the function of urban spaces to carry Xiangchou emotions, promote the inheritance and development of urban culture, and make cities livable places that are modern yet retain cultural depth.

1.2. Research on Urban Xiangchou

The Western psychological concept of “nostalgia” originates from the Greek words “nostos” (returning home) and “algos” (pain), and traditionally refers to a sentimental longing for the past [2], emphasizing temporality [3]. Similar to this is the term “topophilia” in the field of cultural geography [4], which denotes an emotional attachment to the physical environment, emphasizing spatiality. The “Xiangchou” discussed in this paper is distinct from both “nostalgia” and “topophilia”. Compared to “nostalgia”, “Xiangchou” focuses more on one’s place of residence and the associated era. Compared to “topophilia”, the geographical space of “Xiangchou” is more unique. “Xiangchou” possesses subjectivity, temporality, and spatiality; it is a nostalgic emotion based on a specific geographical space, or a topophilia based on a particular period, and it is imbued with a strong sense of traditional Chinese culture. The “Xiangchou” expressed in this paper refers to the longing of urban natives for urban spaces that have disappeared or become alienated in the context of urban renewal, and it has a critical dimension.

Lynch’s five elements of urban imagery—Paths, Edges, Districts, Nodes, and Landmarks—constitute the basic framework of urban space and are also important carriers of Xiangchou [5]. These elements not only provide spatial orientation for residents but also carry rich emotions and memories, becoming triggers for Xiangchou. Paths connect spaces with residents’ daily lives and historical memories [6]; Edges and Districts define urban characteristics, shaping residents’ sense of identity and belonging [7]; Nodes, as intersections of social and cultural activities, play a role in the emotional aggregation of Xiangchou [8]; Landmarks, with their uniqueness and recognizability, strengthen residents’ memories and identification with the city [9].

The material carriers of urban Xiangchou, such as architectural Landmarks, historical streets, and public spaces, serve as tangible links to the past [6], providing visual and spatial frameworks that evoke associated memories and emotions [9]. Intangible carriers, such as local traditions, community activities, and personal narratives, are crucial for maintaining community identity but often require physical places to be fully experienced [10]. Effective carriers of Xiangchou also include everyday spaces that promote social interaction and personal attachment [11], providing continuity and a sense of belonging, which are fundamental components of Xiangchou [12].

Applying Xiangchou in urban design can enhance the emotional connection between residents and their environment [13], especially material carriers, which are more effective due to their enduring presence and ability to serve as physical reminders of the past [14]. Therefore, urban design should prioritize the protection and integration of these elements to foster a sense of place and historical continuity.

1.3. Research on Eye-Tracking Technology

1.3.1. Eye-Tracking Technology Research in the Field of Visual Attention

Eye-tracking technology, as an objective tool for recording visual attention and cognitive processes, plays a significant role in the study of the visual perception of urban spatial elements. This technology has been widely applied to assess the visual quality of building facades [15], street landscapes [16], and public spaces [17], effectively capturing individuals’ visual attention allocation to urban spaces [18].

In urban environments, eye-tracking technology is used to evaluate the visual prominence of various spatial elements, including buildings, green spaces, and public art [19], revealing the correlation between visual preferences and environmental characteristics [20]. Studies have shown that unique architectural features and vibrant public spaces can attract and maintain attention for longer periods, indicating a strong correlation between visual attention and environmental preferences [21]. Additionally, the technology is used to assess the visual quality of environments, understand wayfinding behaviors, and evaluate the impact of urban design elements on visual attention [22,23]. Research reveals that urban elements such as Landmarks and points of interest more effectively capture visual attention, thereby influencing the perception and experience of urban spaces.

Recent studies have further expanded the application of eye-tracking technology, beginning to explore the emotional dimensions of urban spaces. Amati et al. [24] found that, under stress, participants looked at trees and shrubs for longer periods, demonstrating the differences in healing benefits and spatial composition of natural environment elements. This is consistent with the view that visual perception is not only a matter of cognitive processing but also deeply intertwined with emotional experiences [25].

In the context of Xiangchou, eye-tracking studies have also begun to explore how visual cues in urban environments evoke memories and emotional responses. Dupont et al. [26] used eye tracking to analyze the visual perception of landscape photographs, finding that landscape features such as water bodies and green spaces were associated with a higher restorative value and positive emotional responses. This suggests that urban design elements capable of triggering positive memories and emotions can significantly enhance the overall experience of urban spaces.

1.3.2. Eye-Tracking Technology in the Field of Affective Computing Research

Eye-tracking technology in the fields of architecture and urban space research has demonstrated its ability to accurately capture the allocation of individual visual attention, thereby reflecting psychological states and emotional responses [27]. This technology is not only used to analyze people’s visual preferences for urban environments but also delves into emotional experiences. Studies have shown that, by analyzing eye movement data parameters such as fixation points, areas of interest, and heatmaps, it is possible to reveal individuals’ emotional tendencies towards specific urban spaces [28]. For instance, Tian Shaoxu and colleagues’ research, through eye-tracking tests, discovered basic patterns of color emotion among Chinese people, further confirming the close link between visual perception and emotional experience.

Furthermore, eye-tracking technology is widely applied to assess users’ emotional responses to urban design. Researchers use eye-tracking data to identify urban space features that can elicit strong emotional reactions [29], which not only deepens the understanding of residents’ visual perception but also reveals their deep emotional attitudes towards urban spaces. In the field of affective computing, the application of eye-tracking technology is not limited to the recognition of single emotional states but can also distinguish complex emotional differences [30], providing a scientific basis for urban planning and design.

Hou Jian [31] pointed out that the application of eye-tracking technology in emotional research has proven the close relationship between visual perception and psychological feelings, offering a new perspective for assessing and optimizing urban space design. With this technology, designers can make more precise and humanized adjustments to urban spaces based on residents’ emotional feedback, thereby enhancing the overall experience of urban spaces.

1.4. Studies on Application of Five Elements of Cities to Small-Scale Space

The concept of urban imagery first originated in the 1960s when Kevin Lynch introduced the concept of imagery from psychology into the study of urban space [32]. It refers to the spatial perception of the city that residents form through direct or indirect experiences, which is the “subjective environment” in their minds [33].

In the past, image space research mainly focused on the urban scale, but now the attention has shifted to smaller-scale spaces. Dai Juncheng took the China University of Geosciences (Wuhan) as a research area and used cognitive mapping to verify the applicability of Lynch’s five urban elements in small-scale spaces. He also revealed the inverse relationship between Nodes and Districts, providing a theoretical and practical basis for “user-centered” campus planning [34]. Liu Yifei et al. took the waterside space of Shichahai in the old city of Beijing as their research object. Based on Kevin Lynch’s theory of the five urban elements, they categorized the elements of the waterside space into five types. Using wearable GoPro cameras to collect visual perception data (videos and images) and employing GIS spatial analysis methods, they studied the perception intensity and spatial structure of the urban image in historical areas. The study revealed that the characteristic image structure was dominated by Landmarks and provided data support and planning guidance for the overall style creation and construction of a panoramic landscape system in the protection of historical areas [35]. Starting from people’s subjective feelings, Zhu Chunyan applied Kevin Lynch’s concept of urban image to the planning and design of urban park landscapes. She explored the five major elements that constitute the urban image—Paths, Edges, Districts, Nodes, and Landmarks—and analyzed the specific application scope of each element in the planning and design of urban parks [36].

In summary, although Kevin Lynch’s theory of the five urban elements was originally proposed at the urban scale, subsequent empirical studies have shown that the framework of these five elements can be extended to smaller-scale spaces, such as historic and cultural blocks, campuses, parks, and settlements. The universality of this theory stems from the alignment of the element definitions with the laws of human perception, rather than being restricted solely by spatial scale.

2. Research Methodology and Experimental Design

This study utilized a combination of quantitative and qualitative approaches, selecting local students in Hefei with Xiangchou and non-local students studying in Hefei without Xiangchou as comparative groups. Eye-tracking technology was used to quantitatively capture the subjects’ eye movement characteristics when viewing images that could potentially act as Xiangchou carriers, translating the subjects’ subjective feelings into data and making them visualizable. In addition, semi-structured interviews were conducted to qualitatively guide participants in describing their subjective imagery regarding Xiangchou carriers. From the perspective of emotional differences, the study examined urban elements that might function as carriers of Xiangchou.

2.1. Case Site Selection

This study selected Xiaoyaojin Park, which is steeped in history and rich in culture, as the case study object (Figure 1). Originally a renowned battlefield during the Three Kingdoms period, Xiaoyaojin Park became a private garden for bureaucrats and nobility during the Ming and Qing dynasties. After the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, the government transformed it into a public park. The park underwent successive expansions from the 1950s to the 1980s and underwent its first comprehensive and systematic renovation in 2021, aimed at highlighting its profound historical and cultural significance.

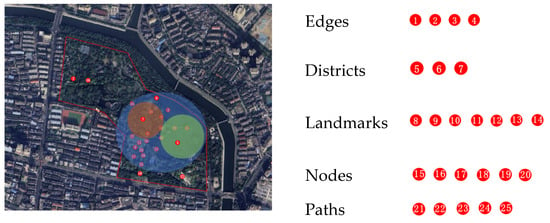

Figure 1.

Map of sample sites in Xiaoyaojin Park.

The historical trajectory of Xiaoyaojin Park spans a millennium, witnessing the historical changes in Hefei and serving as a transmitter of Hefei’s culture. As one of the important ancient battlefield relics of the confrontation between the states of Wu and Wei during the Three Kingdoms period, it is a Landmark of Hefei city and an important public leisure space. It is also a historical education base for primary and middle school students and a must-visit place for spring outings. In addition, it is linked with the surrounding commercial areas to jointly promote the economic development of the old urban area of Hefei. Located in the old urban area of Hefei, Xiaoyaojin Park has been an indispensable urban public space in Hefei since the 1950s. For those who have lived in Hefei, it is undoubtedly a place of great symbolic significance. It not only carries the deep memories and emotions of the people of Hefei, but also occupies an irreplaceable and special position in the hearts of its citizens.

2.2. Sample Selection

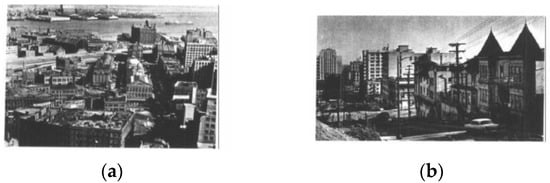

The eye-tracking experiment used photographs of Xiaoyaojin Park, collected on-site, as static stimulus materials. All images were captured between 25 and 26 April 2024 (overcast, 18 °C to 28 °C, southwest wind at level 2) from 6:00 a.m. to 8:00 a.m. Except for the regional elements, the other four types of element images were photographed at a height of 1.6 m (5.25 feet) with a field of view of 120°. The regional element images were taken from a drone’s aerial perspective, with efforts made to avoid crowds during the shooting. The use of an aerial perspective to represent regional elements primarily drew from Kevin Lynch’s study of Boston, where he employed photographs to test locals’ perception of urban space. For the regional element, he utilized aerial photographs (Figure 2). A region is a space that can be entered, and the other four types of elements can appear within a region. Therefore, the authors hoped that their photographs could also cover these four elements. We also considered whether the aerial perspective might be unrecognizable to local people. However, in the subsequent semi-structured interviews, we found that local people could indeed identify these regions. A total of 270 pictures were captured and, after subsequent screening, as well as considering experimental time control issues, a total of 25 pictures were selected to encompass the elements of the corresponding categories as much as possible, ensuring that there was no difference between the elements presented, to avoid the prominence of a particular element or elements, and that the position of each element in the picture and the figure occupied a comparable proportion (Table 1). A total of 270 photos of Xiaoyaojin Park were taken. After manual selection, 25 photos were chosen. The criteria for selection were as follows: First, the prominence of elements was considered to ensure that the types of elements displayed in the photos were clear. Second, interferences from irrelevant elements in the photo frames were excluded (such as the presence of people, changes in sunlight, etc.). Finally, it was ensured that the elements in each photo were centered and occupied a roughly equal proportion of the image area (Table 1).

Figure 2.

Kevin Lynch’s Boston urban district elements ((a). Market District (b). Beacon Hill District).

Table 1.

Pictures of samples selected for eye movement experiment.

2.3. Subject Selection

This study categorized participants based on their familiarity with the site: local students from Hefei who had visited Xiaoyao Jin Park were considered the Xiangchou group, while non-local students studying in Hefei who had not visited Xiaoyao Jin Park were considered the non-Xiangchou group. Many scholars successfully have conducted assessment studies with college students as respondents. These studies have demonstrated that, to a considerable extent, the aesthetic preferences of college students coincide with those of the general public [37,38]. Therefore, 69 students from Hefei University of Technology were randomly selected as participants, with 37 in the Xiangchou group and 32 in the non-Xiangchou group. It must be acknowledged that the choice of college students as the experimental population in this study was somewhat limited. A survey on Xiangchou cognition conducted by Shaoming Lu’s research team, which distributed 2000 questionnaires, found that individuals aged 40 and above had a higher degree of homesickness than those under 40. The frequency of experiencing homesickness increases among people who have been away from their hometown for more than two years. The longer the time away, the stronger the feelings of Xiangchou. Therefore, the intensity of Xiangchou emotions experienced by college student participants is far less than that of individuals aged 40 and above. Subjects were informed of the procedure and purpose of the experiment, and verbal consent was obtained from all subjects before it took place. The formal experiment was conducted between 26 and 28 June 2024, during which subjects were asked to have normal vision and hearing and to abstain from ingesting alcohol or drugs in the 24 h preceding the experiment. After excluding 4 students’ datasets due to external interference (one set due to frequent blinking that led to unreliable data, one set where the thick lenses of glasses prevented the eye tracker from capturing the gaze, and two sets where participants were distracted), 65 groups of valid data were ultimately obtained (Table 2).

Table 2.

Subject attributes.

2.4. Experimental Design

2.4.1. Eye Movement Experiment and Data Processing

- (1)

- Experimental process

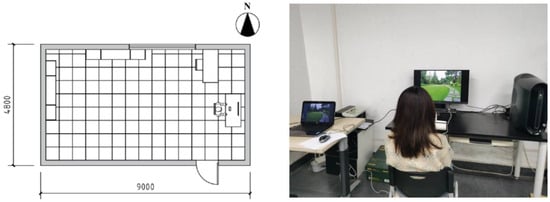

This study utilized a Tobii-Studio-2.2 eye tracker to conduct eye movement measurements, recording the eye movement data. The experiment was conducted in the Human Factors Laboratory at the School of Architecture and Art at Hefei University of Technology. To control the interference of irrelevant factors, the temperature was controlled around 23 degrees Celsius, and the indoor illumination was maintained at approximately 300 lx (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Laboratory environment.

During the experiment, after the subjects were seated, the instructions for the experiment were displayed, and then 25 sample pictures were randomly played; each picture was played for 8 s with a 3 s gray screen interval and the playback process lasted for 5 min.

- (2)

- Experimental data processing

Areas of interest (AOIs) in the sample were identified based on the type of core elements expressed in the pictures, and the AOIs of the pictures were delineated using the Tobii StudioV2.2 software, which delineated the portions of Paths, Edges, Districts, Nodes, and Landmarks in the sample. Six eye movement indexes were selected to study the visual differences in the subjects, which were Total Fixation Duration, Average Fixation Duration, Total Visit Duration, Average Visit Duration, Time to First Fixation, and First Fixation Duration (Table 3). The eye movement heatmap of each subject was obtained by the gaze point mapping function of the software.

Table 3.

Basic significance of eye movement indicators.

2.4.2. Semi-Structured Interviews and Data Processing

- (1)

- Experimental process

After completing the eye movement experiment, talk with the subjects through the interview outline, guide them to describe the image of the carrier of homesickness around “which photo in the eye movement experiment just now will make you recall”, and record the interview content.

- (2)

- Experimental data processing

The interview data were imported into the ROST-CM6 V5.8.0.603 software for word segmentation, and the word frequencies were counted. The synonyms were merged after manual checking, and the words in the top 50% of word frequency in each category were ultimately retained to construct the high-frequency word list. On this basis, social network and semantic network analyses were performed, and the co-occurrence matrix was imported into Gephi V0.10.1 software to generate the co-occurrence network diagram of high-frequency words after merging the synonyms.

3. Results and Analysis

3.1. Analysis of Eye Movement Indicators

This study applied SPSS software (version 24.0, IBM Corporation, New York, NY, USA) to conduct a series of analyses, including independent samples t-tests, one-way ANOVA, and Bonferroni-corrected multiple comparisons, to explore the differences in eye movement behavioral characteristics among subjects with Xiangchou affective differences.

3.1.1. Analysis of Differences Between Groups

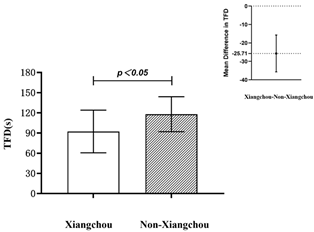

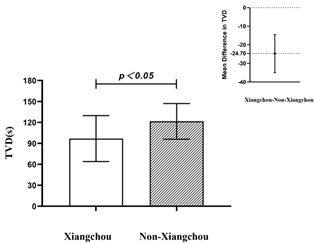

Through independent samples t-tests, it was found that there were significant differences in TFD (p = 0.014) and TVD (p = 0.020) between the subjects from different groups. Subjects without Xiangchou spent more time observing the image samples than those with Xiangchou, suggesting that the cognitive load for subjects without Xiangchou was greater, and they explored more diligently (Table 4). Analyzing the data, the reason for this phenomenon might have been that subjects with Xiangchou had a stronger emotional connection to Xiaoyaojin Park, with stronger memories of the park’s Landmarks, Edges, and Nodes, making it easier for them to extract key information from the overall impression without the need for prolonged careful observation.

Table 4.

The independent samples t-test analysis of eye movement behavior between the two groups of subjects.

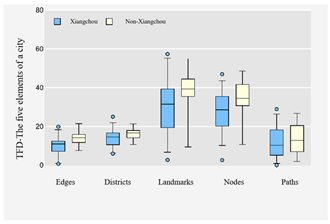

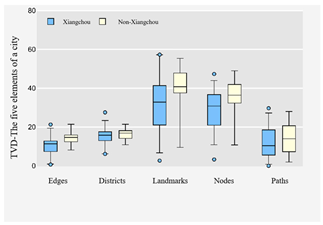

In the premise of satisfying the test for the homogeneity of variances, a one-way ANOVA was conducted, and it was found that the differences in TFD between the two groups of subjects on the elements of Xiaoyaojin Park were primarily on Edges (p = 0.009), Landmarks (p = 0.034), and Nodes (p = 0.032); the differences in TVD were mainly on Edges (p = 0.013) and Landmarks (p = 0.037) (Table 5).

Table 5.

The one-way ANOVA for differences in eye movements between the two groups of subjects.

The data analysis results indicate that there were significant differences in visual attention between the two groups of subjects on the elements of Edges, Landmarks, and Nodes, with the differences in Edges being the most pronounced. This can be analyzed in several aspects. Firstly, subjects in the Xiangchou group may have had deeper emotional connections and memory traces associated with the Edges elements of Xiaoyaojin Park. Environmental psychology indicates that behavior begins at the boundaries. These Edges in Xiaoyaojin Park often serve as the dividing lines between roads and lakes, and they repeatedly appear during walking, with their insurmountability and landscape features continuously reinforcing their impressions on people. Therefore, when they saw these elements, they might have quickly triggered profound emotional responses, leading to a rapid “identification–confirmation” process visually, rather than lingering or repeatedly viewing them. In contrast, subjects in the non-Xiangchou group may have lacked this immediate emotional resonance, thus spending more time observing and exploring. Secondly, the cognitive schema theory (the way in which the human brain organizes and structures knowledge based on past experiences) in environmental psychology points out that people construct cognitive frameworks for the environment based on existing knowledge and experience. Subjects with Xiangchou may have already formed specific cognitive schemas for particular urban elements, especially Edges, which enabled them to quickly identify and understand these elements, thereby reducing their visual exploration time. Conversely, subjects without Xiangchou may have lacked such schemas or had schemas that did not match the presented urban elements, thus requiring longer fixation and revisit time to build or adjust their cognitive frameworks. Landmarks and Nodes often have high visual salience, such as unique shapes, colors, or positions, which may have attracted attention from both groups of subjects during fixation.

3.1.2. Within-Group Differential Visual Preference Analysis

In response to the five types of elements delineated by the experiment, within-group difference analyses were conducted for the two groups of subjects to explore the visual behavior characteristics of the same group of subjects when exposed to images of different element types. The study employed a one-way ANOVA to compare eye-tracking data within the groups. The results, as shown in Table 6, indicate that subjects in the Xiangchou group exhibited significant differences in AFD, AVD, TFF, and FFD across different types of elements. The non-Xiangchou group showed significant differences in AVD and TFF. To investigate which specific elements accounted for these significant differences, the study utilized Bonferroni correction in SPSS for multiple comparisons of the TFF and AVD. The results of these tests are presented in Table 7.

Table 6.

The one-way ANOVA for within-group eye movement differences between the two groups of subjects.

Table 7.

Bonferroni-corrected multiple comparisons of within-group eye movement differences between two groups of subjects.

The differences in AVD between the two groups of subjects were specifically manifested in Landmarks, Nodes, Edges, Districts, and Paths. For subjects in the Xiangchou group, there was also a significant difference between Landmarks and Nodes, with the AVD for Landmarks being less than that for Nodes. This indicated that subjects in the Xiangchou group paid deeper attention to and repeatedly scrutinized the Landmark elements, further proving the important role of Landmarks in evoking Xiangchou emotions, recalling memories, and eliciting emotional experiences; subjects in the non-Xiangchou group could not distinguish between Landmarks and Nodes, which might suggest that these elements lack specific emotional connections for them, being perceived more as objective urban elements, and thus not showing significant preference differences in visual processing. Additionally, Node elements also possess a certain degree of visual salience, similarly to Landmark elements.

In terms of TFF, subjects in the Xiangchou group had the shortest TFF on Landmark elements, which further confirmed that Landmarks, as triggers of Xiangchou emotions, could quickly attract and lock attention during the visual search process. This may have been closely related to the historical memories, cultural significance, or personal experiences carried by the Landmarks, enabling subjects to quickly identify and generate an emotional response upon first glance; whereas subjects in the non-Xiangchou group had the shortest TFF on Node elements, which may have reflected their preference for starting visual exploration from broader or more structural spatial elements, and Nodes, as key points connecting different areas, may have more intuitively drawn their attention.

The experimental results clearly demonstrated how Xiangchou affects individuals’ visual preferences and perception patterns towards urban elements. Subjects in the Xiangchou group, due to their emotional connections, exhibited preferences for specific elements and the ability to quickly identify them, while subjects in the non-Xiangchou group tended to process visuals based on spatial logic and functionality.

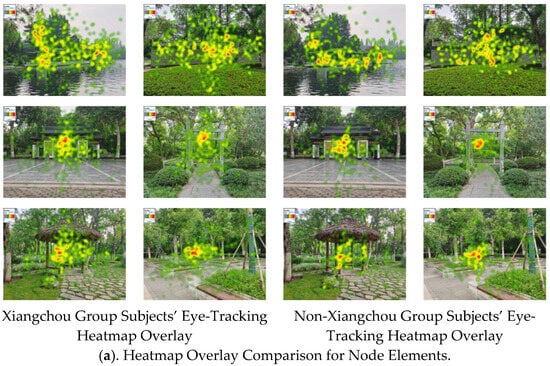

3.2. Visualization and Analysis

To visually analyze where the significant differences between the two groups of subjects on Edges, Nodes, and Landmarks were specifically manifested, this study referred to eye-tracking heatmaps and gaze plots for visual analysis.

The eye movement heatmaps effectively reveal the districts of attention as well as the degree of attention of the subjects when viewing the pictures of the city elements. The degree of attention is differentiated by color, and there are a total of three colors, which are red, yellow, and green; the redder the color, the longer the attention paid, followed by yellow, with green indicating the least. For the Edges, subjects in the Xiangchou group had scattered fixation points, with their gaze mainly wandering along the water’s edge, and they paid attention to observing the junction line between the sky and the trees. In contrast, subjects in the non-Xiangchou group had more focused gazes, with their vision primarily falling on the middle of the picture’s junction line (Figure 4). The subjects in the Xiangchou group and those in the non-Xiangchou group showed little difference in the concentration of fixation points when observing Nodes, but there were differences in the elements they visually focused on. Subjects in the Xiangchou group paid more attention to the structure of buildings, roofs, and the antique building obscured by trees in the background. In contrast, subjects in the non-Xiangchou group were more easily attracted to the boundaries near the water, such as the waterside pavilions (Figure 5). For the Landmark elements, subjects in the Xiangchou group had scattered fixation points across the Xiaoyao Pavilion, with gazes ranging from the base to the roof, and some attention concentrated on the distant Three Kingdoms warships. Subjects in the non-Xiangchou group, on the other hand, primarily focused their gazes at the junction where the two cantilevered eaves met on the first floor of the Xiaoyao Pavilion, where the structure was the most complex (Figure 6).

Figure 4.

Eye movement heatmaps and gaze point maps of Edge elements (a,b).

Figure 5.

Eye movement heatmaps and gaze point maps of Node elements (a,b).

Figure 6.

Eye movement heatmaps and gaze point maps of Landmark elements (a,b).

Gaze plots record the specific locations and time sequences of the subjects’ eye fixations during the viewing process, detailing the trajectory and pattern of visual search. Unlike the eye-tracking heatmaps, the gaze plots selected a time range of 0–0.5 s based on the actual eye movement data of all the subjects for statistical analysis, allowing for a clearer and more accurate observation of the gaze trajectories in each scene [39]. Initially, the gazes of both groups of subjects mostly fell on the center of the image, which is closely related to eye movement, and then shifted to other areas [40]. The second and third fixations of the Xiangchou group diverged towards the surroundings, landing on some landscape elements. In contrast, the gazes of the non-Xiangchou group focused on the structure itself.

3.3. Results of Semi-Structured Interviews

After conducting semi-structured interviews with the two groups, the main results showed clear differences in tendencies: specifically, the Xiangchou group tended to focus on concrete elements, while the non-Xiangchou group was more inclined to pay attention to abstract elements (Table 8).

Table 8.

Semi-structured interview high-frequency glossary.

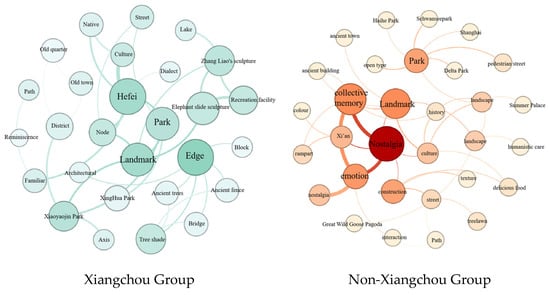

As shown in Figure 7 and the analysis of the evaluation dimensions, it was known that the evaluations of the subjects in the Xiangchou group mainly revolved around concrete material elements such as Landmarks and Edges, with most of the evaluation dimensions related to urban elements in Hefei. In contrast, the evaluations of the subjects in the non-Xiangchou group mainly revolved around abstract non-material elements, including collective memory, history, and culture, with the evaluation dimensions being more divergent. Among them, Landmark elements were mentioned multiple times in the evaluations of both groups regarding the city elements that are carriers of Xiangchou. The subjects in the Xiangchou group tended to regard material elements as the bearers of Xiangchou, while the subjects in the non-Xiangchou group were more inclined to consider non-material elements as the carriers of Xiangchou, advocating that the material carriers of urban Xiangchou should be established under the integration of intangible cultural elements to be meaningful.

Figure 7.

Co-occurrence network diagrams of high-frequency words in evaluation of urban elements as carriers of Xiangchou by two groups of subjects.

The reasons for these results can be explained via the following aspects: Firstly, from the perspective of emotional background, there were differences in regional identity between the two groups of subjects. The Xiangchou group likely represented a demographic with a direct emotional connection to specific regions, such as Hefei, and their evaluations focused more on concrete material elements because these elements were directly linked to their daily lives and memories of growth. The non-Xiangchou group, on the other hand, might have included a broader social demographic whose urban perceptions were not limited to a single region, and, thus, they were more inclined to understand and evaluate from a wider range of historical and cultural aspects. Secondly, from the perspective of cognitive schema and emotional projection, the concrete evaluations of the Xiangchou group may have been closely related to the cognitive schemas they had already established within their minds, which included their unique memories and emotional projections of the city of Hefei. When confronted with urban elements, these schemas were activated, prompting them to rapidly associate emotions with specific material Landmarks. The non-Xiangchou group, on the other hand, may have lacked such direct emotional connections, and, therefore, were more inclined to express their feelings in a more abstract and general manner. Finally, according to Maslow’s hierarchy of needs (which describes the various stages of human motivation and psychological development, organizing human needs into a five-level pyramid with basic physiological needs at the bottom and higher-order self-actualization needs at the top), after fulfilling basic physiological and safety needs, humans pursue higher-level spiritual satisfactions, such as a sense of belonging, respect, and self-actualization. The Xiangchou group may have focused more on satisfying the need for a sense of belonging, using concrete material elements to affirm their identity and cultural affiliation, whereas the non-Xiangchou group might have been at a higher level of psychological needs, enriching their spiritual world by exploring abstract cultural values and maintaining a psychological connection with the past and the future.

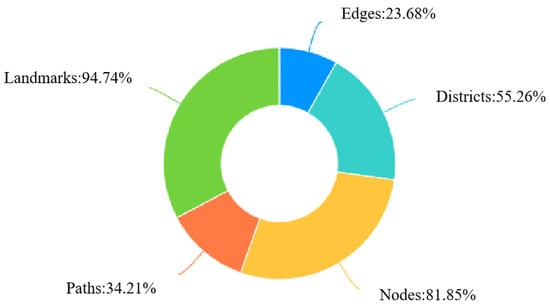

In the voting selection on whether the five urban elements could serve as carriers of urban Xiangchou (Figure 8), it was observed that Landmarks and Nodes received the highest voting proportions, which coincided with the results of the eye-tracking experiments and semi-structured interviews, fully indicating that point elements in the city can be quickly and effectively identified. However, the Edges received the lowest voting proportion, which contradicted the results of the eye-tracking experiments. Based on the results of the semi-structured interviews, when participants were asked the core question, “Which element do you think is most likely to evoke your Xiangchou? What comes to your mind?”, they mentioned Edge elements such as city walls, lakesides, and green spaces (Figure 7). However, when further probed with the question, “Can Edge elements serve as carriers of your Xiangchou memories?”, the vast majority of participants denied this notion. Only a few participants from Xi’an mentioned the ancient city wall. This may be because subjects could not correctly understand the meaning of boundary elements, equating boundaries with fences and railings that divide spaces; secondly, it may be due to the inconspicuous continuity and directional nature of boundary elements, which often act as the background in figure–ground relationships (the perceptual process by which the human visual system differentiates between the primary subject (figure) and the surrounding background (ground) in a visual scene), leading to lower attention being paid to them in daily life. Yet, in reality, boundaries mark the beginning of behavior and subtly infiltrate people’s memories during their movement through cities.

Figure 8.

Percentage of votes for five urban elements as vehicles of Xiangchou.

4. Discussion

Firstly, this study utilizes eye-tracking experiments to delve into the perception of urban element visual preferences based on differences in Xiangchou emotions. The results of the eye-tracking experiments indicate that, among the subjects with Xiangchou emotions, two point elements (i.e., Landmarks and Nodes) and one linear element (edge) of the five urban elements can be rapidly identified, whereas the other two elements—the linear element Paths and surface element Districts—did not receive significant attention.

Specifically, point elements (such as Landmarks and Nodes), due to their distinct visual characteristics, can quickly capture people’s attention and become their visual focus. These elements are not only the visual centers of the city but also nodes of memory, often containing rich historical and cultural connotations, thus easily triggering people’s Xiangchou emotions. Linear elements possess continuity and directionality, playing a role in connecting and organizing urban spaces, guiding people’s gaze and movement trajectories. Edges, as the dividing lines of urban spaces, often become the focus of Xiangchou emotions due to their unique shapes and materials; however, roads, as the main channels of urban traffic, are often designed with a focus on traffic efficiency and safety, with less consideration for emotional needs. Surface elements in urban spaces typically manifest as Districts, plots, and other elements with large areas and scopes. Although Districts have a large spatial range, their internal diversity and complexity may make it difficult for them to form a unified visual image and strong emotional resonance. This phenomenon can also be explained by the figure–ground relationship theory: surface elements, such as Districts, tend to act as the “ground”, while point elements (like Landmarks and Nodes) are more likely to become the “figure”. As for linear elements, depending on their prominence, some are easily recognized due to their clear continuity and directionality while others are difficult to perceive due to their ambiguous shapes and orientations.

Secondly, the differences in semi-structured interview results between the Xiangchou group and the non-Xiangchou group corroborate the eye-tracking experiment results, both revealing the profound impact of differences in Xiangchou emotions on the perception of urban element visual preferences. Firstly, the Xiangchou group’s focused discussion on concrete physical elements (such as Landmarks and Edges) in the interviews coincides with their shorter fixation and refixation times on these elements in the eye-tracking experiments. This suggests that for subjects with Xiangchou emotions, these physical elements, due to their close connection with personal experiences and emotional memories, can be identified and processed in a short time, thus requiring less fixation or refixation. They can quickly extract Xiangchou-related information from these elements, leading to deeper emotional resonance. Secondly, the non-Xiangchou group tends to discuss abstract non-material elements in the interviews, such as collective memory, history, and culture, which to some extent explains why they observed concrete elements like Edges, Landmarks, and Nodes for a longer time in the eye-tracking experiments. Since these elements do not directly touch their emotional resonance points, they may need more time and attention to understand and analyze the meanings and values behind these elements. At the same time, their inability to quickly distinguish Landmarks from Nodes like the Xiangchou group, also reflects a more complex and time-consuming cognitive processing of these concrete elements.

It can be seen that, in urban elements, both objective visual behavior characteristics and subjective interview results indicate the importance of Landmarks as carriers of Xiangchou, followed by Nodes and Edge elements.

5. Conclusions

This study employs eye-tracking technology and semi-structured interviews to compare the physiological and psychological perceptions of urban elements between two groups of people with different Xiangchou emotional backgrounds, thereby exploring the visual differences between the two groups. The following conclusions were drawn:

- (1)

- Xiangchou emotions significantly influence the visual preference perception of urban elements: This study found, through eye-tracking experiments, that Xiangchou emotions are a key factor leading to visual preference differences among different groups for urban elements such as boundaries, Landmarks, and Nodes. Specifically, the subjects with Xiangchou emotions had significantly shorter fixation and refixation times on these elements compared to those without Xiangchou emotions, indicating that Xiangchou emotions facilitate rapid identification and emotional connection with specific urban elements for subjects with Xiangchou.

- (2)

- Landmarks as important carriers of Xiangchou emotions: Both the differences in fixation times from the eye-tracking experiments and the frequent mentions in the semi-structured interviews emphasize the central role of Landmarks in Xiangchou emotions. The rapid fixation and shorter refixation times of the subjects with Xiangchou on Landmarks, as well as both groups considering them as important carriers of Xiangchou emotions, reveal the unique role of Landmarks in constructing and conveying Xiangchou feelings.

- (3)

- Differences in visual attention patterns reflect the depth of emotional connections: The visual analysis results show that subjects with Xiangchou have more dispersed gazes, being able to notice information in the non-main parts of images, indicating a more delicate and in-depth overall perception of the urban environment, which may be related to their strong emotional connection with the city. In contrast, subjects without Xiangchou focused more on the visually salient areas in the sample images, demonstrating a more objective and superficial pattern of visual attention.

Therefore, we should focus on the construction of point elements in urban construction, which should be integrated with urban history, culture, and collective memory. Specifically, we can refer to the following strategies:

- (1)

- In urban planning and design, the impact of differences in Xiangchou on residents’ visual preferences should be fully considered. For residents with Xiangchou, we can focus on optimizing the design of markers and boundaries to attract their attention and stimulate emotional resonance, while moderately reducing the complexity of Nodes to avoid excessive visual interference. For residents without Xiangchou, we can strengthen the regional characteristics and road guidance to direct their attention to a wider range of urban elements, and at the same time incorporate more abstract cultural and historical elements to enrich their visual experience and emotional connection.

- (2)

- In addition, Landmarks should be fully utilized as a bridge of emotional resonance, and Landmarks with regional characteristics and historical connotations should be carefully crafted, regardless of the type of inhabitants, in order to enhance the city’s overall recognition and sense of belonging.

This study primarily focuses on the visual perception aspect, investigating Xiangchou through static images. However, in addition to vision, smell, sound, and movement are also important factors in evoking Xiangchou. The limitation of static images is that they cannot encompass these dynamic influencing factors. Therefore, future research could leverage virtual reality technology to perceive Xiangchou during dynamic walking.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.S. and Z.X.; data curation, R.S.; writing—original draft preparation, R.S. and Z.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Biomedical Ethics Committee of Hefei University of Technology (Protocol code: HFUT20240624001, Date: 24 June 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- National Bureau of Statistics of China. Statistical Bulletin of National Economic and Social Development in 2023; National Bureau of Statistics of China: Beijing, China, 2024.

- Cheung, W.-Y.; Wildschut, T.; Sedikides, C.; Hepper, E.G.; Arndt, J.; Vingerhoets, A.J.J.M. Back to the future: Nostalgia increases optimism. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2013, 39, 1484–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, K.A.; Ellis, R.; Loftus, E.F. Make my memory: How advertising can change our memories of the past. Psychol. Mark. 2002, 19, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J.; Erskine, K. Tropophilia: A Study of People, Place and Lifestyle Travel. Mobilities 2014, 9, 130–145. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, K. The Image of the City; The M.I.T. Press: Cambridge, MA, USA; London, UK, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, C.J.; Relph, E. Place and Placelessness. Geogr. Rev. 1976, 68, 116. [Google Scholar]

- Carmona, M.; Heath, T.; Oc, T.; Tiesdell, S. Public Places-Urban Spaces: The Dimensions of Urban Design; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ley, D.; Samuels, M. Humanistic Geography: Prospects and Problems; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Tuan, Y.F. Space and Place: Humanistic Perspective; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Wildschut, T.; Sedikides, C.; Arndt, J.; Routledge, C. Nostalgia: Content, triggers, functions. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2006, 91, 975–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cauchi-Santoro, R. Mapping community identity: Safeguarding the memories of a city’s downtown core. City Cult. Soc. 2016, 7, 43–54. [Google Scholar]

- Davalos, S.; Merchant, A.; Rose, G.M.; Lessley, B.J.; Teredesai, A.M. ‘The good old days’: An examination of nostalgia in Facebook posts. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 2015, 83, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holak, S.L.; Havlena, W.J. Feelings, Fantasies, and Memories: An Examination of the Emotional Components of Nostalgia. J. Bus. Res. 1998, 42, 217–226. [Google Scholar]

- Orth, U.R.; Bourrain, A. The influence of nostalgic memories on consumer exploratory tendencies: Echoes from scents past. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2008, 15, 277–287. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.; Wu, M.; Ma, Y.; Qu, H. A Review of Eye Tracking Researches in Landscape Architecture Field. J. Hum. Settl. West China 2021, 36, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Wang, H.; Wang, C. Visual Quality Evaluation and Distance Change Analysis of Urban Forest Landscape Based on Eye Movement. J. Chin. Urban For. 2020, 18, 6–12. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Li, Y.; Ren, Y.P.; Anne, L. Research on the Urban Spatial Visual Quality Based on Subjective Evaluation Method and Eye Tracking Analysis. Archit. J. 2020, 190–196. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Chen, Z.; Du, M. Designing Attention—Research on Landscape Experience Through Eye Tracking in Nanjing Road Pedestrian Mall (Street) in Shanghai. Landsc. Archit. Front. 2022, 10, 52–70. [Google Scholar]

- Franek, M.; Sefara, D.; Petruzalek, J.; Cabal, J.; Myska, K. Differences in eye movements while viewing images with various levels of restorativeness. J. Environ. Psychol. 2018, 57, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Y.; Sun, M.; Zhang, J.; Lu, Y. Research Progress on the Application of Eye Tracking Technology in Landscape Architecture. Landsc. Archit. 2024, 31, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R.; Kaplan, S. The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Noland, R.B.; Weiner, M.D.; Gao, D.; Cook, M.P.; Nelessen, A. Eye-tracking technology, visual preference surveys, and urban design: Preliminary evidence of an effective methodology. J. Urban. Int. Res. Placemaking Urban Sustain. 2017, 10, 98–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, J.; Thwaites, K.; Freeth, M. Understanding Visual Engagement with Urban Street Edges along Non-Pedestrianised and Pedestrianised Streets Using Mobile Eye-Tracking. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amati, M.; Sita, J.; Parmehr, E.; Mccarthy, C. How eye-catching are natural features when walking through a park? Eye-tracking responses to videos of walks. Urban For. Urban Green. 2018, 31, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, R.S.; Simons, R.F.; Losito, B.D.; Fiorito, E.; Miles, M.A.; Zelson, M. Stress recovery during exposure to natural and urban environments. J. Environ. Psychol. 1991, 11, 201–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupont, L.; Antrop, M.; Eetvelde, V.V. Eye-tracking Analysis in Landscape Perception Research: Influence of Photograph Properties and Landscape Characteristics. Landsc. Res. 2014, 39, 417–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.Z.; Mountstephens, J.; Teo, J. Emotion Recognition Using Eye-Tracking: Taxonomy, Review and Current Challenges. Sensors 2020, 20, 2384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, S.; Shen, P.; Guo, Y. Color emotion research based on eye tracking technology. J. Commun. Univ. China 2015, 37, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuman, Z.; Weijie, P.; Jian, L.; Nianli, F.; Yu, Z. Survey of Visualization Techniques Based on Eye Tracking Method. Softw. Eng. Appl. 2021, 10, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Ibanez, A.; Urrestarazu, E.; Viteri, C. Recognition of facial emotions and identity in patients with mesial temporal lobe and idiopathic generalized epilepsy: An eye-tracking study. Seizure-Eur. J. Epilepsy 2014, 23, 892–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, H. Design and implementation of a wearable eye tracking system for affective computing. Master’s Thesis, Lanzhou University, Lanzhou, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, C.L.; Song, G.C. Urban lmage Space and Main Factors in Beijing. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2001, 56, 64–74. [Google Scholar]

- Jian, F. Spatial Cognition and the lmage Space of Beijing’s Residents. Geogr. Sci. 2005, 25, 142–154. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, J.-P. On Image Space of Campus:a Case Study of China University of Geosciences in Wuhan. World Reg. Stud. 2009, 18, 141–150. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Mu, T.; Zhen, H.; Sun, P.; Li, C. An Urban lmage Study of Historic Area Based on Visual Perception Data: Shichahai Waterfront, Beijing. Planners 2019, 35, 51–56. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, C.Y. Landscape Planning and Design of Urban Parks from the Perspective of City lmage. J. Anhui Agric. Sci. 2009, 37, 13327–13328+13353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulut, Z.; Yilmaz, H. Determination of waterscape beauties through visual quality assessment method. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2009, 154, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arriaza, M.; Cañas-Ortega, J.F.; Cañas-Madueño, J.A.; Ruiz-Aviles, P. Assessing the visual quality of rural landscapes. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2004, 69, 115–125. [Google Scholar]

- Blascheck, T.; Kurzhals, K.; Raschke, M.; Burch, M.; Weiskopf, D.; Ertl, T. Visualization of Eye Tracking Data: A Taxonomy and Survey. Comput. Graph. Forum 2017, 36, 260–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasco, M. Visual attention: The past 25 years. Vis. Res. 2011, 51, 1484–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).