Abstract

Talent attrition significantly undermines the stable functioning and long-term development of firms in the Architecture, Engineering, and Construction (AEC) industry. Turnover intention is an effective predictor of turnover behavior. Understanding the formation mechanism of turnover intention can help companies maintain the stability of their workforce. However, most of the existing research focuses on the impact of individual factors on turnover intention, lacking an in-depth exploration of the combined effects of multiple factors. This study aims to investigate the underlying mechanisms of employee turnover intention by considering the interplay of various factors. Through an extensive literature review, thirteen hypotheses related to turnover intention are proposed, and a comprehensive theoretical model is developed. Using questionnaire data collected from the AEC industry, the turnover intention model is validated through Structural Equation Modeling (SEM). The validated model shows that turnover intention is directly influenced by working hours (β = 0.127), family-supportive leadership behavior (β = −0.211), and work values (β = 0.356). Meanwhile, turnover intention is indirectly affected by job autonomy (β = −0.089), job demands (β = 0.055) and working hours (β = 0.023), with work interference with family as the mediator, and indirectly affected by family stress (β = 0.037), with work–family interference with work as the mediator. It is worth noting that the impact of family-supportive leadership behavior and job autonomy on turnover intention is negative. This study not only enriches the body knowledge of turnover intention, particularly within the AEC industry, but also provides practical implications for organizations to keep the stability of human resource.

1. Introduction

The Architecture, Engineering, and Construction (AEC) industry plays a key role in the economic development of all countries, and of China in particular. As noted in the China Labor Statistical Yearbook, over the previous decade, the construction sector’s value consistently accounted for above 6.7% of China’s GDP. Additionally, the sector provides enormous employment prospects, with the workforce peaking at 55.63 million in 2018. However, the trend has continued to fall over 2019–2022, showing diminished confidence in the sector’s future due to economic slowdown and the deceleration of real estate development. While 2023 witnessed a 2.17% rise in employment compared to 2022, significant employee turnover continued to impair organizational stability and operational effectiveness. As a labor-intensive sector, the success and sustainability of construction enterprises heavily depend on the stability and quality of their human resources []. Presently, the industry faces severe talent attrition, which disrupts operations, increases costs, and undermines long-term developmental strategies. High turnover rates in the AEC industry cause significant disruptions, including project delays, decreased productivity and compromised quality. These issues are exacerbated by high-pressure environments and unique job characteristics, such as long working hours, frequent relocations, and demanding deadlines. These factors make it challenging for enterprises to maintain a stable workforce [].

To achieve long-term and sustainable development, construction enterprises must build and maintain a stable workforce. Employee retention is crucial for ensuring consistent project execution and fostering organizational growth. However, persistently high turnover rates pose a significant challenge to enterprises striving for high-quality development. Understanding the underlying mechanisms of turnover intention is essential for implementing effective strategies that reduce turnover and enhance workforce stability. By clarifying the formation mechanism of turnover intention in the AEC industry, this study seeks to provide a solid theoretical foundation for enterprises to formulate targeted measures that mitigate turnover risks and support long-term strategic development.

Employee turnover refers to the process by which individuals leave their current employment and depart the organization. This includes both voluntary and involuntary turnover []. Voluntary turnover not only causes direct economic losses to enterprises but also disrupts the normal operation of the organization and affects organizational performance []. The increased workload for remaining employees can adversely impact their mental state, eroding the normal functioning of the organization []. Historically, researchers have focused on voluntary turnover issues.

Additionally, turnover intention, as an effective predictor of turnover behavior, negatively affects employees’ work attitudes and behaviors, such as reducing job satisfaction [] and increasing deviant behaviors []. Research on employee turnover has extensively explored its antecedents and impacts across various industries. Studies have highlighted factors such as job characteristics, work–life balance, and organizational culture as key determinants of turnover intention []. However, existing research has emphasized the manufacturing and service industries, with relatively limited attention having been paid to the AEC sector. In this industry, employees often encounter unique challenges, including demanding work schedules, high-pressure environments, and a heightened necessity to balance professional and personal responsibilities []. Within the context of the AEC industry, these challenges are exacerbated by rapid economic shifts, a competitive labor market, and evolving workforce expectations. While prior studies have examined turnover intentions, few have comprehensively investigated the mechanism of this phenomenon through a systematic framework such as Structural Equation Modeling (SEM). Furthermore, the interplay between job characteristics, family stress, work values, and work–family interference remains neglected. Addressing these gaps is fundamental to developing targeted strategies able to address employee retention and organizational stability.

This study aims to bridge these gaps by employing SEM to explore the formation mechanism of turnover intention of employee in the AEC industry. By examining the direct and indirect effects of job autonomy, working hours, job demands, family-supportive leadership behaviors, family stress, and work values on work–family balance, and turnover intentions, this research provides valuable insights in regard to theoretical advancement and practical applications. The findings are expected to enrich the understanding of turnover intentions in the AEC context and offer actionable recommendations for construction enterprises aimed at mitigating employee attrition, while strengthening workforce stability, and competitive advantage.

To address the research questions, this paper is organized into six main sections. The paper begins with a comprehensive literature review to development of a theoretical model of turnover intention in Section 2, followed by a detailed explanation of the research methodology including the data collection and analysis methodology in Section 3. The results of empirical analysis are presented in Section 4. Finally, the findings are discussed in Section 5, followed by the conclusion and implications for both theory and practice in Section 6.

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

The concept of “employee turnover intention” refers to the propensity of employees to voluntarily terminate their employment with their current organization. Previous studies have established significant relationships between various workplace factors and turnover intentions. Specifically, Lee et al. [] and Zhu et al. [] have demonstrated that positive interpersonal relationships among colleagues and high levels of workplace satisfaction significantly enhance job satisfaction. Conversely, Yin-Fah et al. [] have identified a positive correlation between job stress and employees’ intention to leave their positions. However, existing research in this domain has predominantly focused on examining individual factors in isolation, rather than investigating the complex interplay of multiple variables that collectively influence turnover intentions. This study seeks to address this research gap by developing a comprehensive conceptual framework that incorporates multiple influential factors. Specifically, the research aims to examine the hypothesized relationships among several key variables, including job characteristics, family stress, work–family interference, and work values, with the objective of providing a more holistic understanding of turnover intentions within the Architecture, Engineering, and Construction (AEC) industry.

2.1. Job Characteristics

The theory of job characteristics, rooted in the study of job design and management practices, seeks to elucidate how job attributes influence employee behavior and psychological states. Turner and Lawrence introduced the Required Task Attribute Theory (RTA) in 1965, which delineates six dimensions—job variety, autonomy, required knowledge and skills, responsibility, and necessary as well as casual interactions—as indicators of job complexity. Building on this foundation, Hackman [] developed the Job Characteristics Model (JCM), which identifies five core dimensions: skill variety, task identity, task significance, autonomy, and feedback, to explain how job characteristics affect employee motivation and performance. Concurrently, Karasek Jr [] proposed the Job Demand–Control–Support (JDCS) model, which emphasizes three dimensions—job demands, job control, and social support—offering a novel perspective on the relationship between job characteristics and employee health and performance. Research by Marzuki et al. [] further highlights that perceptions of job facets and levels of job satisfaction vary across occupational groups and managerial positions. Given the practical context and research objectives, this study adopts the JDCS model, categorizing job characteristics in the Architecture, Engineering, and Construction (AEC) industry into work time and demands (job requirement dimension), work autonomy (job control dimension), and family-supportive leadership behaviors (social support dimension).

According to job characteristics theory, higher workplace autonomy is associated with improved employee work attitudes and behavioral outcomes, thereby reducing work–family interference and turnover intention. Cattell et al. [] found that job autonomy negatively correlates with work–family conflict in the South African construction industry. Similarly, Price-Mueller’s turnover model posits a negative relationship between job autonomy and turnover intention []. Based on these findings, the following hypotheses are proposed:

- H1: Job autonomy exhibits a significant negative correlation with work–family interference among AEC industry employees.

- H2: Job autonomy exhibits a significant negative correlation with turnover intention among AEC industry employees.

The allocation of work time to one task often encroaches on time available for other roles, leading to time-based conflicts and work–family interference, which exacerbates work–life imbalance []. Research consistently demonstrates that work time [] and overtime [] are positively associated with higher levels of work–family interference []. Given the finite nature of time and energy, studies on Chinese employees confirm that working hours positively correlate with work–family interference [,]. While extended working hours may boost short-term income, they can also lead to excessive fatigue, adversely affecting health and limiting time and energy for family roles []. Consequently, the following hypotheses are proposed:

- H3: Working hours exhibit a significant positive correlation with work–family interference among AEC industry employees.

- H4: Working hours exhibit a significant positive correlation with turnover intention among AEC industry employees.

Frone et al. [] argue that high job demands compel employees to allocate more personal resources to their work, thereby reducing resources available for family roles and intensifying work–family interference. Employees facing high work and emotional demands are particularly susceptible to work–family conflicts []. Empirical studies consistently link job demands with elevated levels of work–family interference [,]. The JDCS model further suggests that job demands positively influence turnover intentions, as employees who cannot work with peace of mind are more likely to consider leaving their jobs []. Thus, the following hypotheses are proposed:

- H5: Job demands exhibit a significant positive correlation with work–family interference among AEC industry employees.

- H6: Job demands exhibit a significant positive correlation with turnover intention among AEC industry employees.

Social support in the workplace is a multifaceted concept. Kossek et al. [] categorize social support into supervisor support, coworker support, and organizational support. Family-supportive leadership behaviors, a specific manifestation of supervisor support in work–family research [], reflect leaders’ recognition and positive attitudes toward employees’ efforts to balance work and family life []. Such behaviors not only mitigate work–family interference but also enhance job satisfaction []. When employees perceive supervisory support for work–family issues, their sense of work–family interference diminishes. Therefore, the following hypotheses are proposed:

- H7: Family-supportive leadership behaviors exhibit a significant negative correlation with work–family interference among AEC industry employees;

- H8: Family-supportive leadership behaviors exhibit a significant negative correlation with turnover intention among AEC industry employees.

2.2. Family Stress

Family stress theory examines the dynamics of family crises, resource scarcity, and the psychological responses of family members to these challenges. Central to this theory is the notion that family stress arises primarily from a lack of resources necessary to address crises []. Pulsation theory further explores the tensions and psychological reactions of family members when influenced by both internal and external family dynamics []. The ABC-X model conceptualizes family crises as a function of stressors, available resources, and family members’ perceptions, while the dual ABC-X model, introduced by McCubbin et al. [], incorporates a temporal dimension, emphasizing the cumulative effects of stress and the potential for resource regeneration. This model provides a robust theoretical framework for understanding the evolving nature of family stress over time.

Recent research by Masarik and Conger [] highlights that contemporary studies on family stress often focus on specific demographic groups, such as left-behind women, migrant workers, adolescents, and college students. Key family resources, including cohesion, flexibility, social support, and shared family values, play a critical role in mitigating family stress []. Notably, larger family structures tend to experience greater levels of family stress, which in turn exacerbates family interference with work. This interference arises as high family stress demands more time and emotional energy from employees, reducing their capacity to fulfill work responsibilities effectively. Based on these insights, the following hypotheses are proposed:

- H9: Family stress exhibits a significant positive correlation with family interference with work among employees in the AEC industry;

- H10: Family stress exhibits a significant negative correlation with turnover intention among employees in the AEC industry.

2.3. Work–Family Interference

Research on work–family interference has expanded significantly over the past few decades, with a growing emphasis on the conflict between work and family domains and its implications for individual health []. Early studies, such as those by Rotondo et al. [], initially conceptualized work–family interference as a one-dimensional construct. However, as the field evolved, researchers recognized that work–family interference operates bidirectionally, encompassing work interference with family (WIF) and family interference with work (FIW) []. Key factors influencing work–family interference include role expectations, role stress, role commitment, social support, and job characteristics []. Work–family interference has been shown to significantly affect outcome variables in both the work domain (e.g., job satisfaction, burnout, and turnover intention) and the family domain (e.g., family satisfaction and life satisfaction).

Recent studies, such as Wang et al. [], have demonstrated that work–family interference is a significant predictor of turnover intention. This is particularly relevant in the Architecture, Engineering, and Construction (AEC) industry, where employees often face long working hours, irregular vacations, and prolonged separation from their families. These conditions can hinder employees’ ability to fulfill their family roles, thereby increasing turnover intentions. Conversely, family-related stressors, such as high family demands, can interfere with employees’ ability to meet work expectations, leading to family interference with work (FIW) and further exacerbating turnover intentions. Given these dynamics, the following hypotheses are proposed:

- H11: Work interference with family (WIF) exhibits a significant positive correlation with turnover intention among employees in the AEC industry;

- H12: Family interference with work (FIW) exhibits a significant positive correlation with turnover intention among employees in the AEC industry.

2.4. Work Values

Super [] conceptualized work values as intrinsic traits derived from individuals’ personal needs and their aspirations for career development. From a needs-based perspective, work values are defined as the needs employees hold in the workplace [] and the work-related goals and rewards they expect to attain through their employment []. From a cognitive standpoint, work values represent individuals’ perceptions or beliefs about work [], shaping their attitudes, behaviors, and goals by influencing how they evaluate the importance of work and the outcomes it produces. Additionally, from the perspective of value judgment criteria, work values are seen as a framework for evaluating work behaviors and results [].

Work values are recognized as a critical antecedent variable in organizational behavior. Research by Hansen et al. [] highlights that the new generation of employees places greater emphasis on working conditions, safety, coworker relationships, and compensation. George and Jones [] further demonstrated that the relationship between job satisfaction and turnover intention is strongest when employees perceive their work as failing to align with their ultimate values or provide positive emotional experiences. Conversely, this relationship weakens when employees feel their work helps them achieve their core values and fosters positive emotions. Building on these insights, the following hypothesis is proposed:

- H13: Work values exhibit a significant positive correlation with turnover intention among employees in the AEC industry.

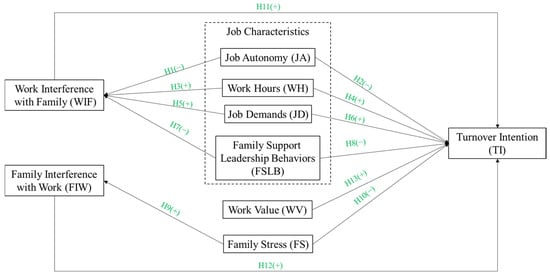

Based on the hypotheses presented above, a conceptual framework reflecting the formation mechanism of the turnover intention was constructed, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Proposal of theoretical model.

3. Research Methodology

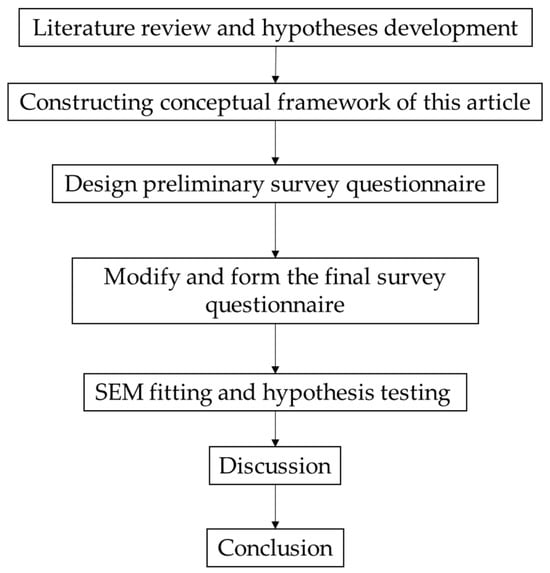

To explore the turnover intention of employees in AEC companies, the research process is conducted in several steps, as shown in Figure 2. Questionnaires are a systematic and widely used method for collecting respondents’ opinions, views, and facts [], and many studies have adopted this method for empirical analysis [,,,]. Since this study aims to investigate the factors influencing turnover intention and the potential relationships between them, a questionnaire survey is suitable for data collection.

Figure 2.

Research process.

3.1. Questionnaire Design

On the basis of the above proposed theoretical model and research hypotheses, a questionnaire was developed in two parts. The first part collected the demographic information of the respondents, including basic personal information that contains gender, age, marital status, and nature of the organization. The second part was the measurement of the observed variables of the proposed theoretical model.

All scales (except working hours) were scored on a 5-point Likert rating scale with positive scores from 1 to 5. The measurement of job autonomy was mainly based on four question items, such as, “How much autonomy do you have over the content of your work tasks schedule?” []. Measurement of average weekly working hours, measured in hours, was used from the study by Ng and Feldman []. In measuring job demands, the main reference was Karasek et al.‘s scale, which contains a total of five question items []. In assessing family-supportive leadership behaviors, the scale of Hammer et al. [] was primarily drawn upon and contained four measurement items. The family stress scale was primarily referenced from Parkerson Jr. et al. []. The family stress scale in this study contains three question items. For example, “Your family has greater pressure to pay a mortgage or car loan.”. The work value scale was mainly referred to eight question items, for example, “The job was in line with your interests [].” In the study of work–family interference, which covers two important dimensions, work interference with family (WIF) and family interference with work (FIW), each of these dimensions contains five question items []. The turnover intention consists of four statements, for example, “I often want to quit my current job []”.

3.2. Data Collection

The survey of this study is divided into two steps. The first step is a small sample pre-test in August 2023, and the second step is the formal research stage and questionnaire collation, which took place from September 2023 to October 2023.

The pre-testing stage took the form of offline collection of questionnaire data, and the semantic ambiguities and irrational questionnaire structure design in the questionnaire were revised and adjusted based on the feedback from the respondents. Based on the feedback of the data from the small sample test, the content of the scale was adjusted in a targeted manner. It was ensured that the Cronbach’s alpha value of all items exceeded 0.7, the KMO value was greater than 0.6, and Bartlett’s sphere test statistic value showed significance in statistical significance. In addition, the factor loadings for each scale item exceeded 0.5. Adjustments were made to determine the final research questionnaire.

The formal research questionnaire of this study adopts online collection of questionnaire data, and the scope of the research involves all provinces in China. At the same time, the type of organizations to which the research object belongs covers owner, construction company, design company and consultant company. Ensure that the research data are representative. After collecting the questionnaire data, 422 valid questionnaires were screened by eliminating the questionnaires with obvious random filling and logical confusion.

3.3. Data Analysis Methods

In this study, the reliability of the data was tested using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, and the validity of the data was tested using Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA). After the reliability and validity tests, Pearson’s correlation coefficient was used to clarify the significance of variable relationships. Finally, CB-SEM structural equation modeling was used because the sample size was more than five times the size of the variables []. The method integrates the direct and indirect effects between variables and the error factor. In path analysis, direct relationships between variables are quantified by estimating path coefficients. And indirect relationships through mediating variables are quantified by the Bootstrap sampling method. The path coefficients reflect the strength and direction of the effects between variables, which helps to identify key variables and paths and reveal the complex network of relationships between variables. SPSS 25.0 and AMOS 24.0 software were used in this study for data processing, analysis, and model fitting.

4. Results

4.1. Characteristics of Samples

The research lasted 3 months, with 451 electronic questionnaires collected, of which 422 valid questionnaires were identified, generating validity rate of 93.6%. Of the 422 valid responses, a summary of the descriptive characteristics of the respondents is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of recovered samples.

4.2. Reliability and Validity Tests

For the reliability test of the questionnaire as a whole and each variable, since the value of Corrected Item-Total Correlation (CITC) for WA2 and WV1 questions is less than 0.5, and the reliability of each variable is significantly improved after deleting these questions, these two measurement items were deleted. The reliability coefficients for the scales of job autonomy, job demands, family supportive leadership behavior, family stress, work values, work–family interference, and turnover intention are all greater than 0.7, thus indicating that the scales used in this study satisfy the requirements of internal consistency.

CFA was used to test the validity of the questionnaire data. According to the theory of Kyriazos [], two items were deleted (WV6, WV7), and the optimized measurement model fits well. The results show that the factor load of each item is greater than 0.6. The content validity, structure validity, Convergent validity and discriminant validity of the questionnaire data all pass the validity test.

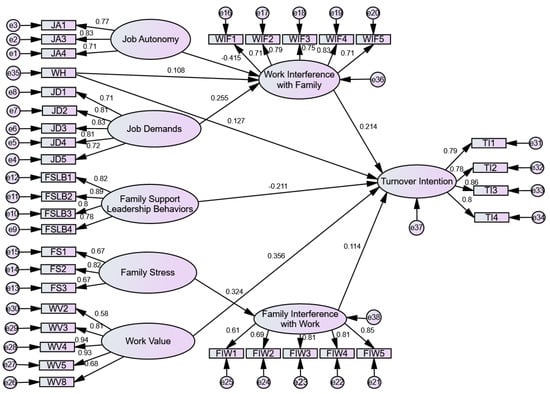

4.3. SEM Fitting and Hypothesis Testing

AMOS 24.0 was used to fit the proposed theoretical model (Figure 1) and to test the theoretical hypotheses. According to the results of the model fit test for each scale, CMIN/DF = 2.524, which is in the excellent range of 1–3, and RMSEA = 0.060, which is in the good range of less than 0.08. Except for TLI, which is close to 0.9, the test results of IFI and CFI are all greater than 0.9. Therefore, the results of the model fit indexes of each scale can be synthesized, and it can be seen that the model of this study has a good fit. The final model is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Validated theoretical model.

The path relationships are determined after the empirical analysis, and the proposed hypotheses are validated, as shown in Table 2. Job autonomy negatively and significantly affects construction employees’ work–family interference (β = −0.415, p < 0.001), working hours and job demands all have a significant positive effect on work–family interference among construction employees (β = 0.108, p < 0.05; β = 0.255, p < 0.001), and family-supportive leadership behaviors are not significant predictors of AEC industry employees’ work–family interference is not significantly predictive (β = −0.050, p > 0.05). Therefore, hypotheses H1, H3, and H5 are valid, and hypothesis H7 is not valid.

Table 2.

Total, direct, and indirect effects.

Family stress positively and significantly affects AEC industry employees’ family interference with work (β = 0.324, p < 0.001), hypothesis H9 is valid. Work interference with family positively and significantly affects AEC industry employees’ family interference with work (β = 0.488, p < 0.001). Job autonomy is not a significant direct predictor of turnover intention of employees in AEC industry (β = −0.083, p > 0.05), WH (working hours) has a significant positive direct effect on turnover intention of employees in AEC industry (β = 0.127, p < 0.01). Job demands cannot significantly and directly affect turnover intention of employees in AEC industry (β = −0.001, p> 0.05), family-supportive leadership behavior has a significant negative direct effect on the turnover intention of employees in AEC industry (β = −0.211, p < 0.001), work values have a significant positive direct effect on the turnover intention of employees in AEC industry (β = 0.356, p < 0.001), and there is a significant positive effect (β = 0.356, p < 0.001) of work interference with family and family interference with work on the turnover intention of employees in AEC industry (β = 0.214, p < 0.01; β = 0.114, p < 0.05). Thus, hypotheses H4, H8, H11, H12, H13 are established, and hypotheses H2, H6, H10 are not established.

A bootstrap sampling method was used to test the mediation effect of work interference with family and family interference with work. The Bias-corrected 95% confidence intervals of the mediating paths JA→WIF→TI (β = –0.089), WH→WIF→TI (β = –0.023), JD→WIF→TI (β = 0.055), and FS→FIW→TI (β = 0.037) do not include 0, and the significance coefficients are all less than 0.05, indicating that the mediating effects of work interference with family and family interference with work in the above paths have significant impacts. At the same time, based on the results of the path analysis, it can be seen that work interference with family plays a fully mediating role between job autonomy and turnover intention, as well as between work demands and turnover intention, while it plays a partially mediating role between work hours and turnover intention. Family interference with work plays a fully mediating role between family stress and turnover intention.

A combination of the path analysis results to obtain the direct effects, indirect effects, and total effects of each variable is shown in Table 2.

According to Table 3, among the test results of the 19 proposed research hypotheses, 14 are supported and 5 are not supported.

Table 3.

The results of the path relationship test.

5. Discussion

5.1. Job Characteristics

As it turns out, job autonomy does not have a significant direct effect on turnover intentions in the AEC industry. This result supports the opinion of Wang []. But it does have a significant negative effect on work–family interference. The possible reason for this is that China’s AEC industry has developed rapidly over the past few decades, with the cultural expectation that people working in the construction industry should adapt to the project demands. However, in view of the correlation coefficient between job autonomy and work–family interference, there is a significant high correlation between the two (β = −0.415, p < 0.001). When the level of job autonomy in the work environment is high, employees’ work interference with family and intention to leave are lower [].

Working hours have a significant positive effect on work–family interference and turnover intention. The results of the study show that the average weekly working hours of employees in construction enterprises exceed the 44 h stipulated by the labor law, but are less than the 49.3 h reported for construction workers in 2022 in the 2023 ‘China Labor Statistical Yearbook’. This is a positive trend, but far from satisfactory. Employees of the AEC industry generally need to travel as a project demands, and consequently change workplace and living place. When stationed on a project for a long period, the boundaries between work and life are not clearly delineated and become blurred, leaving employees prone to mental nervousness and other psychological issues []. At the same time, as emergencies arise in projects, staff may need to work overtime, again leading to personal life and family time being reduced []. However, according to the correlation coefficients between the variables, the correlation between working hours and work–family interference and the turnover intention are of low degree (β = 0.108, p < 0.05; β = 0.127, p < 0.01), and the increase in working hours only impacts turnover intentions once reaching a high level.

Job demand has a significant positive effect on work–family interference while it has no significant direct effect on turnover intentions in the AEC industry. This is because high job demands require employees to devote more time to their work and less to their family. According to role conflict theory, it is known that the higher the work demands of employees in the AEC industry, the lower the possibility that other demands can be satisfied. This result is consistent with previous findings []. The significant low degree of correlation between job demands and work–family interference (β = 0.108, p < 0.05) may be attributed to the fact that most roles in the construction industry require high commitments at the front line of projects. Indeed, employees working in the construction industry recognize the reality of the higher job demands of the industry, and the relatively poor living conditions and working environment that come with the job. As a result, this may explain the lesser impact on work–family interference when job demands are only slightly higher, with no significant direct effect on turnover intentions. In addition, job demands require a significant amount of work resources to prevent work family interference [].

Family-supportive leadership behaviors do not have a significant effect on work–family interference but exert a significant direct influence on turnover intentions. The lack of impact on work–family interference may stem from the suboptimal regulations and systems related to family support in construction enterprises, as well as the limited implementation of family-supportive behaviors in practice. However, family-supportive leadership behaviors have a significant negative effect on turnover intention (β = −0.211, p < 0.001), indicating that employees who perceive stronger family-supportive leadership are less likely to consider leaving their jobs []. A study on the turnover intention of nurses in Chinese public hospitals further supports this finding, suggesting that when employees in the AEC industry feel their leaders’ support in family-related matters, they experience greater freedom to handle personal obligations without fear of professional repercussions. Strengthening employee trust in organizational support for family responsibilities may, therefore, serve as an effective strategy to reduce turnover intentions [].

5.2. Family Stress

The results of the empirical analysis of this paper show that family stress has a significant positive effect on the family–work interference of employees in construction enterprises (β = 0.324, p < 0.001). That is, the family stress of employees in construction enterprises will significantly exacerbate the conflict between family and work. However, this stress will not directly nor significantly affect turnover intention. Relevant research indicates that family stress not only directly leads to work–family conflict but may also indirectly affect job performance through emotional exhaustion []. For construction company employees, individual family stress largely determines the magnitude of family–work interference. Low family financial pressure and low burden of family tasks will appropriately reduce family–work interference of employees. By contrast, where employee family stress is high, and where family economic pressure is high, the employee will consider the opportunity cost of leaving their job. When the family task burden is heavy, employees will consider whether the task burden can be resolved by other means of compensation, such as hiring a nanny to take care of the elderly or children, or hiring a housekeeper to deal with household chores. When family stress due to economic pressure or task burdens can be relieved or solved, the family–work interference of employees in construction enterprises will be reduced accordingly.

5.3. Work Values

The results of this paper show that work values have a significant positive effect on the turnover intentions of employees in construction enterprises (β = 0.356, p < 0.001). That is, the higher the level of work values of employees, the higher the standard of value judgment in all aspects of the job. As Chinese society evolves with the times, employees pay more attention to the development of their firm, as well as their own development, the working environment, and interpersonal relationships. Construction enterprise employees need to be stationed at the project site for a long time, and spend more time with their managers and colleagues, to the degree that the equality and harmony of the work team becomes critical to making employees feel relaxed and comfortable, which again is conducive to reducing turnover intentions. Work values play a decisive role in shaping the career expectations, orientation and goal selection of employees, which also affects their attitudes, motivations and ways of working, and work effectiveness []. Therefore, corporate managers should guide employees to form positive and healthy work values in daily management in order to optimize their work mindset, enhance their motivation, initiative and sense of responsibility, and thus improve the overall work effectiveness and organizational performance of the enterprise. At the same time, there are differences in employees’ work values across different industries []. Therefore, companies should guide employees to form positive and healthy work values based on industry characteristics in their daily management. This will optimize employees’ work attitudes, enhance their work enthusiasm, initiative, and sense of responsibility, thereby improving the overall work efficiency and organizational performance of the company.

5.4. Work–Family Interference

In exploring the correlation between the variables, it was found that both work–family interference and family–work interference have a significant positive effect on the turnover intentions in the AEC industry. The correlation coefficient between work–family interference and turnover intentions (r = 0.214) is slightly higher than the correlation coefficient between family–work interference and turnover intentions (r = 0.114) This suggests that work–family interference has a greater impact on turnover intentions [].

At present in China, most families have been transformed into dual-income families, with employees not only needing to take on work duties but also corresponding family duties. At the same time, employee mindsets are changing, with family life and personal life gradually being elevated in importance. When family members need to be attended to by employees, the extra time and energy that needs to be redirected to domestic concerns may cause employees to consider whether they need to change job or occupation to one more family friendly []. This shows that family factors are increasingly emphasized by employees, and have a significant impact on the formation of both family–work interference and the turnover intentions.

5.5. Limitation

This study had some limitations. First, the research primarily focuses on employees within China’s AEC industry, which may introduce regional bias and limit the generalizability of the findings to other contexts. Second, the reliance on self-reported data may lead to overestimations of employees’ abilities or contributions. Future studies should incorporate more objective data collection methods to improve accuracy. Third, the study examines only three key factors—job characteristics, family stress, and work values—while other potentially influential variables remain unexplored. Expanding the research scope to include additional factors could provide a more comprehensive understanding of turnover intentions. Finally, the varying effects of different types of family stress on turnover intentions warrant further investigation to clarify their distinct impacts.

6. Conclusions

The AEC industry is currently facing a significant talent drain, as skilled professionals increasingly opt to leave the sector. This study employs Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) to comprehensively explore the mechanisms underlying turnover intentions within the AEC industry, focusing on work characteristics, work values, family stress, and work–family interference. Building on existing theories and prior research, a conceptual model was developed and tested using a sample of 422 employees from the AEC industry. The study yields the following key findings:

(1) Work interference with family fully mediates the relationship between work autonomy and turnover intention (β = –0.089), indicating that enhancing employees’ autonomy over their work content, pace, and intensity during work hours increases their rest and family time, thereby reducing work–family interference and ultimately lowering employees’ turnover intention; (2) Work interference with family plays a partially mediating role between work hours and turnover intention (β = –0.023). Longer working hours intensify work–family interference and increase turnover intentions (β = 0.127); (3) High job demands exacerbate work–family interference and elevate turnover intentions (β = 0.055); (4) Family-supportive leadership behaviors negatively influence turnover intentions (β = −0.211); (5) Family interference with work plays a fully mediating role between family stress and turnover intention (β = 0.037). Increased family stress amplifies work–family interference; (6) Employees with higher work values exhibit stronger turnover intentions (β = 0.356), as those with elevated expectations are more likely to seek alternative opportunities.

Compared to existing research, this paper categorizes the causes of turnover intention into two levels and multiple dimensions. It employs structural equation modeling and path analysis to determine the interrelationships among multiple factors, work interference with family, family interference with work, and turnover intention. The study integrates the findings of previous research and speculates on the reasons for the formation paths based on the characteristics of construction industry employees.

In organizational management practice, employees facing low job autonomy and sustained high-intensity work demands often experience adverse stress responses on both psychological and physiological levels. Psychologically, they may suffer from job burnout, emotional distress, and emotional exhaustion, while physiologically, they may encounter reduced sleep quality and deteriorating physical health. In recent years, workplace incidents of premature death due to overwork have become increasingly common, intensifying employees’ desire for a better work–life balance. However, achieving the ideal state of “balancing work and family” remains an elusive goal for many employees. Organizations must deeply reflect on the fact that excessive working hours and high work intensity make it difficult for employees to find equilibrium between their professional and personal lives, leading to heightened work–family conflicts. Family-supportive leadership behaviors can help mitigate employees’ turnover intentions. Therefore, organizations should recognize and promote such supervisory support behaviors to facilitate a harmonious balance between employees’ work and personal lives. Excessive family stress can contribute to work–family conflict, negatively impacting employees’ work performance and efficiency in construction enterprises, which in turn affects organizational performance and development. Consequently, human resource management policies should take into account employees’ family responsibilities while aligning with their career development and the enterprise’s transformation and upgrading strategies. This study constructs a multi-factor turnover intention model based on work–family conflict, contributing to the theoretical understanding of turnover intention formation. The findings provide a theoretical foundation for enterprises to retain talent and achieve stable development.

Future research could extend this study by examining turnover intentions among expatriate employees in international construction projects, increasing sample size, and expanding the sample scope across different cultural and organizational settings. These efforts would enhance the generalizability of findings and provide deeper insights into workforce retention strategies in the AEC industry.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft, X.Z.; Writing—review & editing, G.L., G.Z., I.M. and D.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 72271246) and Research Centre for Systems Science & Enterprise Development, Key Research of Social Sciences Base of Sichuan Province (Grant No. Xq24B04). The APC was funded by Chengdu University of Technology.

Institutional Review Board Statement

All subjects gave their informed consent for inclusion before they participated in the study. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, with due regard for ethical standards, and the protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Construction Management Department of Chengdu University of Technology (CDUT-EC202307016) on 12 July 2023.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Azeem, M.; Ullah, F.; Thaheem, M.J.; Qayyum, S. Competitiveness in the Construction Industry: A Contractor’s Perspective on Barriers to Improving the Construction Industry Performance. J. Constr. Eng. 2020, 3, 193–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lingard, H.; Francis, V. The Work-life Experiences of Office and Site-based Employees in the Australian Construction Industry. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2004, 22, 991–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodanwala, T.C.; Santoso, D.S. The Mediating Role of Job Stress on the Relationship between Job Satisfaction Facets and Turnover Intention of the Construction Professionals. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2022, 29, 1777–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieper, J.R.; Maltarich, M.A.; Nyberg, A.J.; Reilly, G.; Ray, C. Collective Turnover Response over Time to a Unit-Level Shock. J. Appl. Psychol. 2023, 108, 1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hancock, J.I.; Allen, D.G.; Soelberg, C. Collective Turnover: An Expanded Meta-Analytic Exploration and Comparison. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2017, 27, 61–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiedermann, C.J.; Barbieri, V.; Engl, A.; Piccoliori, G. Impact of Relational Coordination on Job Satisfaction and Willingness to Stay: A Cross-Sectional Survey of Healthcare Professionals in South Tyrol, Italy. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hom, P.W.; Lee, T.W.; Shaw, J.D.; Hausknecht, J.P. One Hundred Years of Employee Turnover Theory and Research. J. Appl. Psychol. 2017, 102, 530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, D.G.; Vardaman, J.M. Global Talent Retention: Understanding Employee Turnover around the World. In Global Talent Retention: Understanding Employee Turnover Around the World; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bentley, UK, 2021; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, J.; Liu, C.; Zhou, Y.; Duan, K. Work-to-Family Conflict, Job Burnout, and Project Success among Construction Professionals: The Moderating Role of Affective Commitment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.-C.; Huang, S.-H.; Zhao, C.-Y. A Study on Factors Affecting Turnover Intention of Hotel Empolyees. Asian Econ. Financ. Rev. 2012, 2, 866. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, W.; Zeng, R.; Li, X.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, Z. Managerial Drivers of Chinese Labour Loyalty in International Construction Projects. J. Civ. Eng. Manag. 2017, 23, 1109–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin-Fah, B.C.; Foon, Y.S.; Chee-Leong, L.; Osman, S. An Exploratory Study on Turnover Intention among Private Sector Employees. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2010, 5, 57. [Google Scholar]

- Hackman, J.R. Work Redesign; ReadingAddison-Wesley: Boston, MA, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Karasek, R.A., Jr. Job Demands, Job Decision Latitude, and Mental Strain: Implications for Job Redesign. Adm. Sci. Q. 1979, 24, 285–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzuki, P.F.; Permadi, H.; Sunaryo, I. Factors Affecting Job Satisfaction of Workers in Indonesian Construction Companies. J. Civ. Eng. Manag. 2012, 18, 299–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattell, K.; Bowen, P.; Edwards, P. Stress among South African Construction Professionals: A Job Demand-Control-Support Survey. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2016, 34, 700–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, C.W.; Price, J.L. Economic, Psychological, and Sociological Determinants of Voluntary Turnover. J. Behav. Econ. 1990, 19, 321–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adkins, C.L.; Premeaux, S.F. Spending Time: The Impact of Hours Worked on Work–Family Conflict. J. Vocat. Behav. 2012, 80, 380–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzywacz, J.G.; Marks, N.F. Reconceptualizing the Work–Family Interface: An Ecological Perspective on the Correlates of Positive and Negative Spillover between Work and Family. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2000, 5, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hooff, M.L.M.; Geurts, S.A.E.; Kompier, M.A.J.; Taris, T.W. Work–Home Interference: How Does It Manifest Itself from Day to Day? Work Stress 2006, 20, 145–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiRenzo, M.S.; Greenhaus, J.H.; Weer, C.H. Job Level, Demands, and Resources as Antecedents of Work–Family Conflict. J. Vocat. Behav. 2011, 78, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, E.L.; Parkes, K.R. Work Hours and Well-Being: The Roles of Work-Time Control and Work–Family Interference. Work Stress 2007, 21, 264–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, J.I.; Allen, S.; Hill, E.J.; Mead, N.L.; Ferris, M. Work Interference with Dinnertime as a Mediator and Moderator Between Work Hours and Work and Family Outcomes. Fam. Consum. Sci. Res. J. 2008, 36, 310–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golden, L.; Wiens-Tuers, B. To Your Happiness? Extra Hours of Labor Supply and Worker Well-Being. J. Socio-Econ. 2006, 35, 382–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frone, M.R.; Yardley, J.K.; Markel, K.S. Developing and Testing an Integrative Model of the Work–Family Interface. J. Vocat. Behav. 1997, 50, 145–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, A.B.; Grzywacz, J.G.; Bass, B.L.; Linney, K.D. Extending the Demands-control Model: A Daily Diary Study of Job Characteristics, Work-family Conflict and Work-family Facilitation. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2005, 78, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Major, V.S.; Klein, K.J.; Ehrhart, M.G. Work Time, Work Interference with Family, and Psychological Distress. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beehr, T.A.; Glaser, K.M.; Canali, K.G.; Wallwey, D.A. Back to Basics: Re-Examination of Demand-Control Theory of Occupational Stress. Work Stress 2001, 15, 115–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kossek, E.E.; Pichler, S.; Bodner, T.; Hammer, L.B. Workplace Social Support And Work–Family Conflict: A Meta-Analysis Clarifying the Influence of General And Work–Family-Specific Supervisor and Organizational Support. Pers. Psychol. 2011, 64, 289–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, L.B.; Kossek, E.E.; Yragui, N.L.; Bodner, T.E.; Hanson, G.C. Development and Validation of a Multidimensional Measure of Family Supportive Supervisor Behaviors (FSSB). J. Manag. 2009, 35, 837–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, L.T.; Ganster, D.C. Impact of Family-Supportive Work Variables on Work-Family Conflict and Strain: A Control Perspective. J. Appl. Psychol. 1995, 80, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, L.B.; Ernst Kossek, E.; Bodner, T.; Crain, T. Measurement Development and Validation of the Family Supportive Supervisor Behavior Short-Form (FSSB-SF). J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2013, 18, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCubbin, H.I.; Joy, C.B.; Cauble, A.E.; Comeau, J.K.; Patterson, J.M.; Needle, R.H. Family Stress and Coping: A Decade Review. J. Marriage Fam. 1980, 42, 855–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boss, P.; Bryant, C.M.; Mancini, J.A. Family Stress Management: A Contextual Approach; Sage Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Masarik, A.S.; Conger, R.D. Stress and Child Development: A Review of the Family Stress Model. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2017, 13, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hobfoll, S.E.; Spielberger, C.D. Family Stress: Integrating Theory and Measurement. J. Fam. Psychol. 1992, 6, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eby, L.T.; Casper, W.J.; Lockwood, A.; Bordeaux, C.; Brinley, A. Work and Family Research in IO/OB: Content Analysis and Review of the Literature (1980–2002). J. Vocat. Behav. 2005, 66, 124–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotondo, D.M.; Carlson, D.S.; Kincaid, J.F. Coping with Multiple Dimensions of Work-Family Conflict. Pers. Rev. 2003, 32, 275–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, T.D.; Martin, A. The Work-Family Interface: A Retrospective Look at 20 Years of Research in JOHP. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2017, 22, 259–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xia, Q.; Yue, H.; Teng, W. Chinese Rural Kindergarten Teachers’ Work–Family Conflict and Their Turnover Intention: The Role of Emotional Exhaustion and Professional Identity. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Super, D.E. The Work Values Inventory; U. Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Kalleberg, A.L. Work Values and Job Rewards: A Theory of Job Satisfaction. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1977, 42, 124–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H. A Theory of Cultural Values and Some Implications for Work. Appl. Psychol. Int. Rev. 1999, 48, 23–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberson, B. The Colonel Blotto Game. Econ. Theory 2006, 29, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elizur, D. Facets of Work Values: A Structural Analysis of Work Outcomes. J. Appl. Psychol. 1984, 69, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, J.-I.C.; Leuty, M.E. Work Values Across Generations. J. Career Assess. 2012, 20, 34–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, J.M.; Jones, G.R. The Experience of Work and Turnover Intentions: Interactive Effects of Value Attainment, Job Satisfaction, and Positive Mood. J. Appl. Psychol. 1996, 81, 318–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fellows, R.F.; Liu, A.M. Research Methods for Construction; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Carayon, P.; Schoepke, J.; Hoonakker, P.L.T.; Haims, M.C.; Brunette, M. Evaluating Causes and Consequences of Turnover Intention among IT Workers: The Development of a Questionnaire Survey. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2006, 25, 381–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delobelle, P.; Rawlinson, J.L.; Ntuli, S.; Malatsi, I.; Decock, R.; Depoorter, A.M. Job Satisfaction and Turnover Intent of Primary Healthcare Nurses in Rural South Africa: A Questionnaire Survey: Job Satisfaction and Turnover Intent of PHC Nurses in Rural South Africa. J. Adv. Nurs. 2011, 67, 371–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, N. Factors Affecting Overall Job Satisfaction and Turnover Intention. J. Manag. Sci. 2008, 2, 239–252. [Google Scholar]

- Heyns, M.; Rothmann, S. Volitional Trust, Autonomy Satisfaction, and Engagement at Work. Psychol. Rep. 2018, 121, 112–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, T.W.H.; Feldman, D.C. Long Work Hours: A Social Identity Perspective on Meta-analysis Data. J. Organ. Behav. 2008, 29, 853–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkerson, G.R., Jr.; Michener, J.L.; Wu, L.R.; Finch, J.N.; Muhlbaier, L.H.; Magruder-Habib, K.; Kertesz, J.W.; Clapp-Channing, N.; Morrow, D.S.; Chen, A.L.-T. Associations among Family Support, Family Stress, and Personal Functional Health Status. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 1989, 42, 217–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.P.; Irving, P.G.; Allen, N.J. Examination of the Combined Effects of Work Values and Early Work Experiences on Organizational Commitment. J. Organ. Behav. 1998, 19, 29–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bothma, C.F.C.; Roodt, G. The Validation of the Turnover Intention Scale. SA J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2013, 11, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Matthews, L.M.; Matthews, R.L.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM or CB-SEM: Updated Guidelines on Which Method to Use. Int. J. Multivar. Data Anal. 2017, 1, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriazos, T.A. Applied Psychometrics: Sample Size and Sample Power Considerations in Factor Analysis (EFA, CFA) and SEM in General. Psychology 2018, 9, 2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, E.; Jiang, W.; Mao, S. Job Autonomy and Turnover Intention among Social Workers in China: Roles of Work-to-Family Enrichment, Job Satisfaction and Type of Sector. J. Soc. Serv. Res. 2020, 46, 862–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, S.; Ayman, R. Work Flexibility as a Mediator of the Relationship between Work–Family Conflict and Intention to Quit. J. Manag. Organ. 2010, 16, 411–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannai, A.; Tamakoshi, A. The Association between Long Working Hours and Health: A Systematic Review of Epidemiological Evidence. Scand. J. Work. Environ. Health 2014, 40, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samad, A.; Reaburn, P.; Di Milia, L. The Contribution of Job Strain, Social Support and Working Hours in Explaining Work–Family Conflict. Asia Pac. J. Hum. Resour. 2015, 53, 281–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Woerkom, M.; Bakker, A.B.; Nishii, L.H. Accumulative Job Demands and Support for Strength Use: Fine-Tuning the Job Demands-Resources Model Using Conservation of Resources Theory. J. Appl. Psychol. 2016, 101, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Carlo, A.; Girardi, D.; Falco, A.; Dal Corso, L.; Di Sipio, A. When Does Work Interfere with Teachers’ Private Life? An Application of the Job Demands-Resources Model. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, R.T.; Matthews, R.A.; Walsh, B.M. The Emergence of Family-Specific Support Constructs: Cross-Level Effects of Family-Supportive Supervision and Family-Supportive Organization Perceptions on Individual Outcomes: Cross-Level Effects of FSS & FSOP. Stress Health 2016, 32, 472–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Jin, T.; Jiang, H. The Mediating Role of Career Calling in the Relationship between Family-Supportive Supervisor Behaviors and Turnover Intention among Public Hospital Nurses in China. Asian Nurs. Res. 2020, 14, 306–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Busque-Carrier, M.; Ratelle, C.F.; Le Corff, Y. Work Values and Job Satisfaction: The Mediating Role of Basic Psychological Needs at Work. J. Career Dev. 2022, 49, 1386–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rueff-Lopes, R.; Velasco, F.; Sayeras, J.; Junça-Silva, A. Understanding Turnover of Generation Y Early-Career Workers: The Influence of Values and Field of Study. Pers. Rev. 2024, 54, 762–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, C.X.; Li, J.C. Work-Family Conflict, Burnout, and Turnover Intention among Chinese Social Workers: The Moderating Role of Work Support. J. Soc. Serv. Res. 2022, 48, 12–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, E.L.; Moen, P.; Oakes, J.M.; Fan, W.; Okechukwu, C.; Davis, K.D.; Hammer, L.B.; Kossek, E.E.; King, R.B.; Hanson, G.C.; et al. Changing Work and Work-Family Conflict: Evidence from the Work, Family, and Health Network. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2014, 79, 485–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).