Abstract

Reducing light pollution and promoting sustainable lighting practices require new tools that integrate environmental, social, and technical considerations in design processes. Urban Digital Twins are emerging as powerful instruments for this purpose, enabling integrated evaluation of lighting impacts on both people and ecosystems. This paper presents an exploratory evaluation of NorDark-DT, a recently developed urban digital twin designed to support the sustainable planning of lighting infrastructure in green urban areas. This exploratory assessment was conducted with master’s students engaged in lighting design practices. Participants performed two task-oriented exercises of planning and comparing lighting configurations after-dark for a site in Uppsala, Sweden. Results show that NorDark-DT effectively facilitates the exploration of alternative lighting solutions within realistic green urban area contexts and encourages reflection on issues such as light pollution, biodiversity, and ecological preservation. Nevertheless, further improvements are required to enhance the user interface, expand analytical capabilities, strengthen integration with professional lighting software, and optimize performance for varying hardware setups. Beyond professional practice, the tool also proved valuable for educational purposes by promoting interdisciplinary collaboration and broadening students’ understanding of sustainability in lighting design. Overall, this study provides an initial step in a usability assessment of NorDark-DT, confirming its potential to support environmentally responsible, socially aware, and well-informed lighting interventions.

1. Introduction

Light infrastructure has become closely intertwined with the development of modern cities, not only serving as a driver of economic growth and urban activity [1,2], but also enhancing safety and comfort [3,4]. However, the rapid expansion of artificial lighting has also resulted in increasing levels of light pollution, which over the past decades has emerged as a major environmental concern [5,6,7]. Changes in natural light conditions have been shown to affect both human health and ecological systems negatively, highlighting the need for more systematic approaches to mitigation [8,9,10,11]. Consequently, there is a growing demand for innovative methods that support the sustainable design of lighting infrastructure, strengthening multidisciplinary collaboration and fostering the education of new professionals capable of integrating ecological, social, and technological perspectives in lighting design. Such approaches should combine technological development and urban planning with participatory and collaborative strategies to balance human needs and environmental protection [11,12,13].

Urban digital twins have emerged as keystone tools in modern city planning and administration, anchoring the evolution of intelligent cities [14,15]. These dynamic and data-rich virtual representations of physical urban environments not only facilitate long-term strategic development but also provide real-time insights that enable adaptive decision-making [14]. More formally, an urban digital twin is defined as “a dynamic high-fidelity representation of real-life entities of city systems and sub-systems that reflects their states and behaviour across their lifecycle and that can be used to securely monitor, analyse, and simulate current and future states using data analytics, data integration, and artificial intelligence aimed at improving the quality of life and well-being of citizens” [14]. Typical applications range from planning to monitoring and optimization of daily operations of urban areas, including, among others, traffic management, road planning, and urban pedestrian analysis [16,17,18,19,20], pollution and waste management [21,22,23], building conservation [24], sustainable city development [25], community engagement [26], and lighting infrastructure design [27,28,29,30].

In parallel with the emergence of urban digital twins, other visualization and simulation technologies have been increasingly explored for lighting design and analysis. Virtual reality (VR), for instance, has proven particularly effective for representing lighting environments and studying perceptual, emotional, and behavioural responses to light [31,32,33,34]. Such immersive tools provide designers and researchers with the ability to evaluate selected human-centered lighting conditions without the need for costly or time-consuming physical prototypes. However, despite their advantages, VR-based approaches have some limitations to simulate real-world lighting; also, they typically lack the dynamic, data-driven capabilities needed to support continuous, real-time analysis and long-term planning within urban contexts [35].

Recent studies have therefore begun to bridge this gap by linking virtual representations with real-world data streams. For example, Tabbah et al. [30] developed a lighting design framework that integrates data exchange between physical and digital environments, demonstrating the potential of digital twin concepts for lighting applications—though still limited to indoor settings. This highlights the need for tools capable of addressing outdoor and ecological dimensions of lighting design.

NorDark-DT builds upon these developments as a specialized urban digital twin designed to visualize natural environments during nighttime and to support the planning and implementation of sustainable outdoor lighting infrastructure. Beyond its technical capabilities, NorDark-DT was conceived to integrate multiple societal and ecological perspectives, reflecting the diverse concerns and interests present within urban environments. By simulating after-dark environmental and human conditions, the tool enables urban planners and designers to craft lighting strategies that promote both nature conservation and human well-being [29]. A distinctive aspect of NorDark-DT is its more-than-human perspective, which allows users from difference domain to visualize nighttime environments and assess the potential impacts of lighting infrastructure not only on humans but also on wildlife. This integrated and transdisciplinary approach positions NorDark-DT as both a collaborative decision-making platform and an educational resource for exploring the intersections of urban design, ecology, and sustainable lighting.

NorDark-DT has been applied in preliminary analyses across several scenarios, including exploratory investigations of how vegetation density affects the illumination of public spaces and can be used to reduce light pollution in natural areas, and walkability index assessments under different lighting configurations [28,29]. These initial applications not only provided promising insights but also demonstrated the potential of the tool as a resource for research, professional practice, and educational purposes in sustainable lighting and urban design.

This paper presents a preliminary, exploratory usability assessment of NorDark-DT, focusing on its application by lighting design graduate students from the KTH Royal Institute of Technology (Sweden). The aspiring lighting designers tested the DT through task-oriented activities involving the analysis of outdoor lighting design problems and the comparison of alternative lighting options. This work aims to explore initial user experiences and perceptions of the tool in order and thus provide early insights to inform future validation studies with educational institutions and professional practitioners, including light designers, urban planners, municipal stakeholders, and real-world projects.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. NorDark-DT

NorDarkDT is an urban digital twin designed to support the development of sustainable lighting infrastructure for urban green spaces [29]. This digital twin has been created as part of the NorDark project, (https://nordark.org/ (as of September 2025)), an interdisciplinary initiative aimed at generating new knowledge for sustainable design in urban environments after dark. The foundation in sustainable design of lighting infrastructure lies in balancing multiple factors, including human well-being and behavioural patterns, and low energy consumption, while also minimizing negative impacts on wildlife.

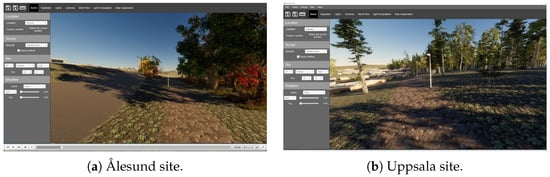

The current version of the digital twin contains 3D environments related to the two study locations of the NorDark research project: one in Ålesund, Norway, and another in Uppsala, Sweden (Figure 1a and Figure 1b, respectively). Field experiments involving modifications to lighting infrastructure and wildlife monitoring were conducted exclusively in Uppsala. Furthermore, the tool was designed with the flexibility to create simulated environments for additional locations beyond the initial sites.

Figure 1.

NorDark-DT screenshots. (a) 3D environment set to the Ålesund site. (b) 3D environment set to the Uppsala site.

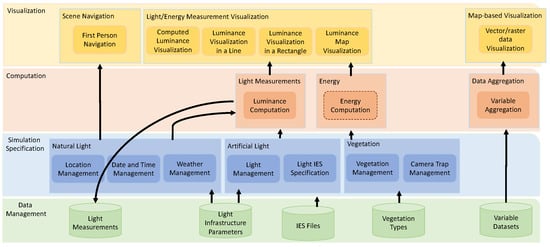

The NorDark-DT architecture comprises four components (see Figure 2): (1) Data Management, which handles data from the twin itself and external sources, focusing on lighting infrastructure configurations and approximative luminance calculations; (2) Parameter Specification, defining parameters for simulating scenarios like sky conditions, weather, and vegetation distribution; (3) Computation, involving luminance score assessment and aggregation of variables (e.g., luminance, slope, speed limit) using weighting-based schemes; and (4) Visualization, enabling analysis through luminance score displays, comparisons, and map-based visualizations of aggregated results. For more details regarding the requirements and features of the Nordark-DT, the reader may refer to [29].

Figure 2.

NorDark-DT arhictecture.

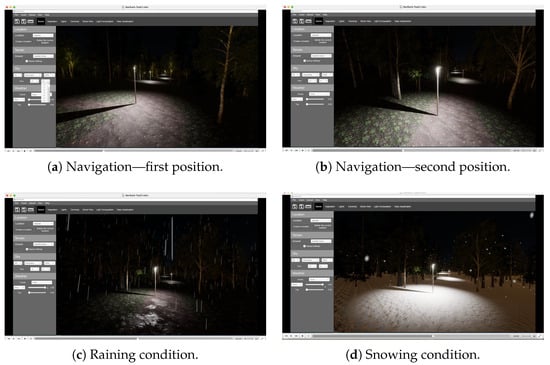

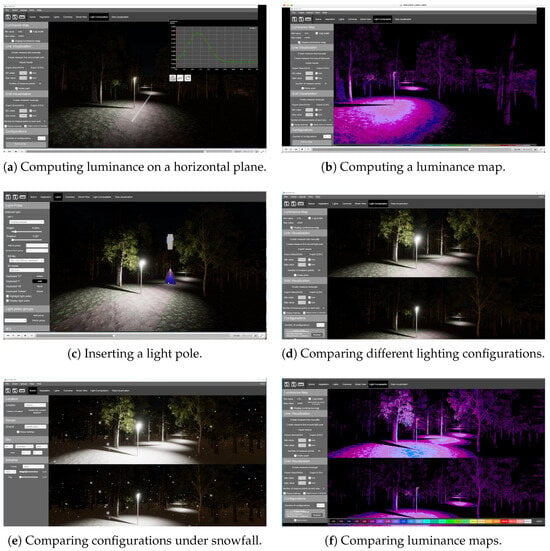

Figure 3 and Figure 4 show screenshots of the digital twin, illustrating some of its main features, including navigation across different positions in the 3D environments (Figure 3a,b), modeling of weather conditions (Figure 3c,d), computation of luminance scores (Figure 4a,b), change in the lighting infrastructure (Figure 4c), and comparison of different lighting intervention alternatives (Figure 4d–f). Enlarged versions of the figures can be found in Supplementary Material S4. NorDark-DT can be downloaded from https://nordark.org/ (As of September 2025).

Figure 3.

NorDark-DT features. (a,b) Navigation from one location to another. (c) Simulation of a rainy condition. (d) Simulation of a snowy condition.

Figure 4.

Screenshots of the NorDark-DT features used to measure luminance, change lighting design infrastructure, and compare light design. (a) Computation of luminance along a line. (b) Computation of a luminance map. (c) Addition of a light pole in a target site. (d) Comparison of two configurations. (e) Comparison of the two configurations under snowy conditions. (f) Comparison of luminance maps computed according to the two selected configurations.

2.2. Evaluation Protocol

This paper introduces an exploratory evaluation of NorDark-DT through a task-oriented activity conducted with master’s students engaged in lighting design practices. To evaluate the functionality and relevance of Nordark-DT in lighting infrastructure design, we carried out a task-oriented assessment involving next-generation professionals—individuals who are typically more receptive to technological innovations. This approach allowed us to explore both the educational and professional dimensions of NorDark-DT, highlighting its potential to support learning outcomes and enhance design processes through task-driven engagement.

Task-oriented assessment in computing and software development is implemented through goal-driven activities that evaluate systems and learning outcomes based on real-world tasks. It is particularly effective for assessing software usability by simulating real-world scenarios that reflect user behaviour [36]. In education, task-based assessments, such as those used in the Bebras initiative, help measure students’ computational thinking through structured problem-solving activities [37,38].

The task-oriented activities implemented focused on three key objectives: Assess participants’ initial familiarity with digital technologies and digital twin (DT) applications in lighting interventions for green urban areas. Evaluate the usability of Nordark-DT, including the accessibility and intuitiveness of its core features. Explore changes in understanding regarding the role and potential of urban digital twins in lighting design after interacting with the tool. In addition to these objectives, we gathered participants’ first impressions of the broader value of urban digital twins in enhancing lighting design for green urban spaces.

2.2.1. Participants

Nineteen students enrolled in the MSc Architectural Lighting Design program at the KTH Royal Institute of Technology in Sweden participated in the assessment of the NorDark-DT tool. This evaluation took place during the HS2008 Light and Space-Outdoor course in the Fall of 2023. The students enrolled in the MSc Architectural Lighting Design program at the KTH Royal Institute of Technology are typically international, multidisciplinary graduate students with academic or professional backgrounds in architecture, interior design, engineering, or other lighting-related design fields.

All participants were asked to sign the Consent Form. The purpose of the Consent Form was to obtain formal agreement from the students to participate in this research. This is a necessary requirement when conducting surveys that may involve the collection of sensitive information. The consent form outlines the objectives of the study, that participation is voluntary and can be stopped at any time, and briefly describes how the collected data will be used (see Supplementary Material S1).

2.2.2. Assessment Procedures

The assessment session began with a brief introduction to the NorDark research project, providing participants with the context and objectives of this research, as well as the purpose of the NorDark-DT tool in supporting the design of sustainable lighting infrastructure.

Subsequently, a presentation on NorDark-DT was delivered, demonstrating its functionality and key features, including the ability to explore different scenes (Uppsala and Ålesund sites), modify weather conditions, modify lighting poles, and add vegetation. A user manual for the digital twin was also provided. Participants were then invited to download and install the tool on their own computers, with compatible versions available for Windows, macOS, and Linux. After installation, participants were invited to develop two tasks (see Supplementary Material S2) and to answer a questionnaire (see Supplementary Material S3).

2.2.3. Task-Oriented Description

The objective was to analyse the lighting conditions along a pathway in a natural area under varying environmental (day and night-time) and weather scenarios (Task-01), and to propose a new lighting design that enhances visibility and safety after dark (Task-02). The selected location was a site in Uppsala, Sweden—chosen because it is the only NorDark study site where both lighting infrastructure modifications and wildlife monitoring have been implemented (refer to [29] for a description of the study areas). To support the task-oriented activities, participants were provided with a detailed guide outlining each step (see Supplementary Material S2).

In Task-01, participants familiarized themselves with the digital tool by following a series of steps to recreate the Uppsala study scenarios. Task-01 began with participants opening the 3D scene of the Uppsala site and adjusting parameters such as date, time, and weather conditions. This allowed them to observe variations in natural light conditions across seasons (summer and winter) and times of day (Figure 1b and Figure 3a). In the next step, participants were instructed to navigate or walk along the path to simulate how a person might perceive different lighting conditions at the after-dark site and under different environmental conditions (Figure 3a–d). Finally, participants generated luminance-based measurements using the computational tools available in the NorDark-DT platform. This was performed by drawing a line between two points in the 3D scene and generating a luminance graph (see Figure 4a).

In Task-02, participants evaluated two different lighting infrastructure designs, which were built upon the results of Task-01 by introducing a new lighting design and comparing the two. Participants were asked to place and relocate light poles within the scene (Figure 4c) and define their specifications using 3D models (object representation) and IES files (light intensity distribution). They then measured the luminance conditions of the new design and saved the results. In the final step, participants compared the initial configuration from Task 01 with the new design from Task-02 by analysing luminance maps and configurations (Figure 4d–f).

2.2.4. Questionnaire

The questionnaire addressed five different aspects. First, it focused on participants’ familiarity and previous experience with digital tools, including digital twins, and their use in planning, lighting interventions, and lighting design within urban green areas. Second, it assessed the usability of NorDark-DT during Tasks-01 and Task-02, evaluating how easy it was to complete these tasks. Third, it collects information on the participants’ perceptions of the tool’s potential for supporting lighting design and evaluating alternative lighting configurations. Fourth, the questionnaire evaluated the improvement in participants’ understanding of digital twin technology following the task-oriented activities. This was achieved by asking the same question before and after using NorDark-DT: “How do you rate your understanding of how digital twins work before/after using the tool?”. Fifth, it gathered qualitative feedback through two open-ended questions: “Do you have any comments or suggestions to improve the digital twin?” and “How useful do you find the digital twin for your professional domain?”

3. Results

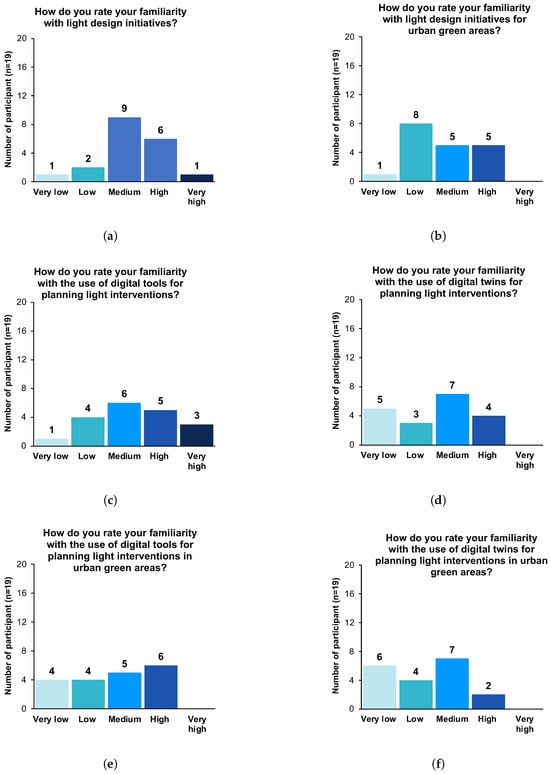

3.1. Participants’ Familiarity with Digital Tools

Figure 5 provides an overview of the participants’ familiarity with digital tools, digital twins, and tasks related to the planning of lighting interventions in urban green areas. Most of the participants expressed a “Medium” to “High” level of familiarity with lighting design processes (Figure 5a). However, their familiarity was lower in the context of urban green areas, where most of the participants experienced a “Low” level (Figure 5b). The participants were lighting design graduate students, most with a background in architecture and other building design professions, and while outdoor lighting is a part of the course curriculum, related coursework had just begun shortly before this study.

Figure 5.

Results of the questionnaire assessing participants’ familiarity with digital twins and urban digital twin tools for lighting interventions in urban green areas. The x-axis represents categories of familiarity, ranging from “Very low” to “Very high.” The y-axis indicates the number of participants. n denotes the total number of participants. (a) Familiarity with design initiatives. (b) Familiarity with light design initiatives for urban green areas. (c) Familiarity with digital tools for light intervention. (d) Familiarity with digital twins for light intervention. (e) Familiarity with digital tools for light intervention in green urban areas. (f) Familiarity with digital twins for light intervention in green urban areas.

In relation to their familiarity with the use of digital tools, most participants indicated “Medium” to “Very high” familiarity (Figure 5a). Concerning the use of urban digital twins for lighting intervention planning (Figure 5d), participants reported varied levels, including lower levels of familiarity, being mostly from “Medium” to “High” and “very low.”

When asked about their familiarity with using digital tools for designing lighting interventions in green urban areas, participants were distributed relatively evenly across the spectrum—from “high” to “very low” familiarity (Figure 5e). However, when specifically asked about the use of urban digital twins in these contexts, participants reported significantly lower familiarity. The majority indicated a “Medium” level of familiarity, followed by “Very Low” and “Low” (Figure 5e).

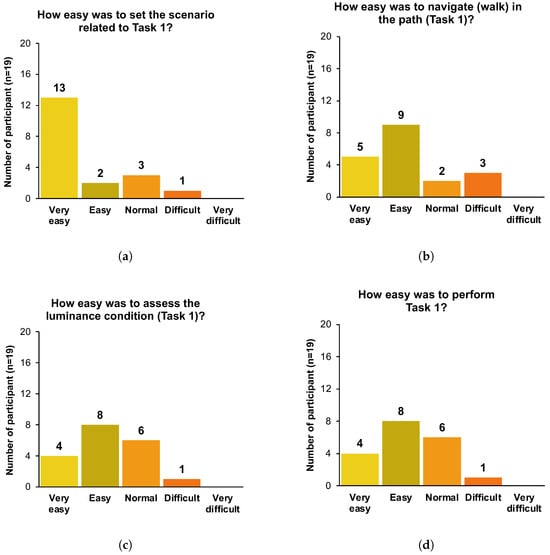

3.2. Evaluation Regarding Task-01

Figure 6 summarizes the results of the evaluation of Task-01. Overall, participants found the task approachable, with most reporting positive experiences across its components. Scenario Setup (Figure 6a): The majority rated this step as “Very Easy” (13), “Easy” (2), or “Normal” (3). Only one participant found it “Difficult,” and none rated it as “Very Difficult.”

Figure 6.

Results of the questionnaire assessing the usability of the software, based on participants’ ratings of the difficulty in completing the activities in Task-01. The x-axis represents difficulty categories, ranging from very easy to very difficult. The y-axis indicates the number of participants. The value of n denotes the total number of participants. (a) Easiness in setting the scenario. (b) Easiness in navigating in the 3D scene. (c) Easiness in assessing the luminance condition. (d) Easiness of Task-01.

3D Scene Navigation, walk in the path (Figure 6b): Five participants rated it “Very Easy,” nine “Easy,” and two “Normal.” Three found it “Difficult,” while none selected “Very Difficult.”

Luminance Condition Assessment (Figure 6c): Ratings were predominantly positive, with four participants selecting “Very Easy,” eight “Easy,” and six “Normal.” Only one participant rated it as “Difficult,” and none as “Very Difficult.”

Overall Task Execution (Figure 6d): Most participants found Task-01 manageable, with four rating it “Very Easy,” eight “Easy,” and six “Normal.” Again, only one participant reported it as “Difficult,” and none as “Very Difficult.”

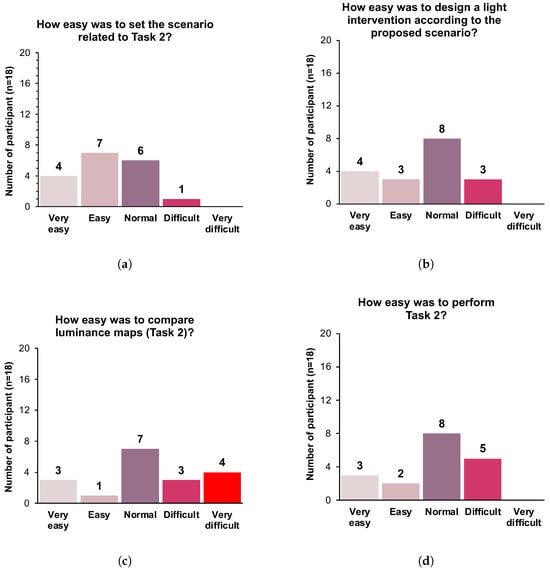

3.3. Evaluation Regarding Task-02

Figure 7 presents the results related to Task-02. Overall, participants showed a mixed but generally moderate level of ease in completing the steps of this task.

Figure 7.

Results of the questionnaire assessing the usability of the software, based on participants’ ratings of the difficulty in completing the activities in Task-02. The x-axis represents difficulty categories, ranging from very easy to very difficult. The y-axis indicates the number of participants. The value of n denotes the total number of participants. (a) Easiness in setting the scenario. (b) Easiness in performing the light intervention. (c) Easiness in comparing luminance maps. (d) Easiness of Task 2.

Scenario Setup (Figure 7a): Most participants found this step manageable; four participants rated it “Very Easy,” seven “Easy,” and six “Normal.” Only one participant considered it “Difficult,” and none rated it as “Very Difficult.”

Lighting Intervention Design (Figure 7a): This activity was most commonly rated as “Normal” with participants, followed by four “Very Easy” and two “Easy.” Three participants found it “Difficult,” and none selected “Very Difficult.”

Luminance Map Comparison (Figure 7c): This was perceived as more challenging. Seven participants rated it as either “Difficult” or "Very Difficult.” Nevertheless, a substantial number rated it “Normal,” while a few found it “Very Easy” (3) or “Easy” (1).

Overall Task Execution (Figure 7d): Most participants assessed Task-02 as “Normal” (8) or “Difficult” (5). Fewer rated it as “Very Easy” (3) or “Easy” (2), and none selected “Very Difficult.”

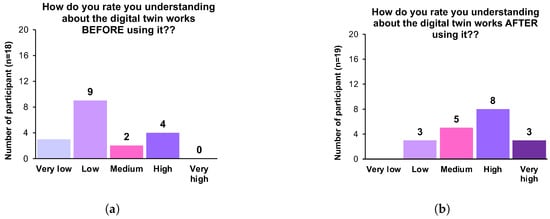

3.4. Understanding of the NorDark-DT Tool

Figure 8 shows the results for the assessment of participants regarding their understanding of the NorDark-DT tool before and after using it. Most of the participants did not have a full understanding of NorDark-DT before performing the assigned tasks. Fifteen out of nineteen of them (Figure 8a) reported “Very Low” (3), “Low” (9), or “Medium” (2) levels of understanding. Only four participants reported “High” and none at “Very High.” The assessment changed considerably after using the tool (Figure 8b). In this case, 16 out of 19 participants reported “Medium” (5), “High” (8), or “Very High” (3) levels. Only three participants reported “Low” understanding and none, “Very Low.”

Figure 8.

Understanding before and after using NorDark-DT. (a) Before. (b) After.

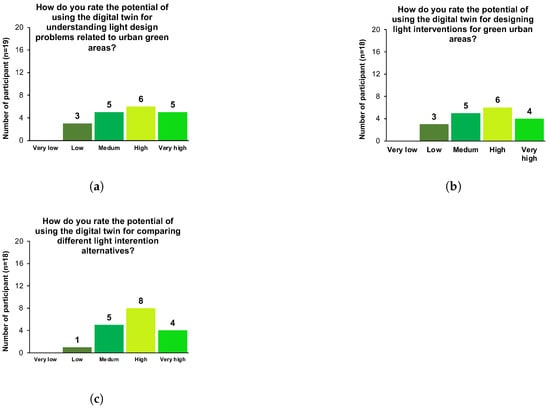

Figure 9 shows the results related to the assessment of the potential of using the tool for understanding (Figure 9a), designing (Figure 9b), and comparing (Figure 9c) light interventions. Most participants acknowledge the tool’s strong potential across tasks, with over 10 rating it as “High” or “Very High.”

Figure 9.

Potential of using the NorDark-DT digital twin. (a) Understanding light design problems. (b) Designing light interventions. (c) Comparing light intervention alternatives.

3.5. Qualitative Assessment

Fourteen participants provided comments and suggestions to improve the digital twin. Many users noted that the software is too heavy and demands high-performance hardware, such as gaming laptops, to function effectively. Some comments provided include “It’s very heavy for a laptop” and “Would be great if the software had lesser graphical demands”.

Interface and usability were also mentioned as relevant aspects to be improved in the NorDark-DT. Elements of the interface were described as not intuitive enough in some situations, requiring users to make additional efforts. One direction of improvement pointed out was borrowing usability principles from Dialux (“I suggest that the environment could be somewhat more similar to Dialux’s way of configuring the light, etc.”), one of the mainstream lighting simulation software that most practitioners and learners in the lighting design field are familiar with.

Improved controls for supporting navigation in the 3D environments were also suggested (“a(n) easy interface to navigate, commands could be clearer, say copy, select, and move”). Some participants reported that some controls were imprecise, giving the impression of “flying” over the scene.

Other feature enhancements that were mentioned included the following: adding more options to control luminaire settings for large areas, providing customizable views to understand results for specific scenarios, and enabling scenario comparisons (e.g., lighting designs for different seasons or weather conditions). Tools to compare graphs across scenarios were also requested, as these additions could make the software more practical and insightful (“…if we could compare graphs in two scenarios, it could be more reasonable”).

Regarding the evaluation of how useful the digital twin is in their domain, 11 participants provided feedback, and all of them indicated that the software is or can be useful or very useful in the urban lighting design domain. The software was seen as a powerful tool for urban analysis and research studies (“I believe it is a powerful tool for urban analysis and research studies”; “I think it is very useful to find the appropriate solution for urban lighting design”), although some users caution that its computer-based results might differ from real-world outcomes. Nonetheless, it is valuable in supporting research efforts before moving to fieldwork. Its potential for educational purposes was also highlighted, especially in teaching sustainability and interventions through small projects, allowing students to better understand and engage with these concepts. One comment on that direction was, “It … also might be good in education with more information or diving deep into the purpose (with a small project?) to understand or educate students on the sustainability or interventions, etc.”.

4. Discussion

Lighting design must balance human needs with environmental protection, which requires tools that enable the integration of knowledge from several fields [11,39]. Such tools should not only support sustainable design practices but also contribute to the education of future professionals by fostering interdisciplinary collaboration, broadening their perspective beyond human-centered needs [40,41]. In this context, educational and professional tools that emphasize sustainability—such as energy efficiency, reducing light pollution, and ecological considerations—are particularly valuable in lighting design and urban planning. Urban digital twins have emerged as promising instruments for advancing sustainable design and facilitating cross-disciplinary collaboration. However, as their application in specific domains remains at an early stage, it is crucial to develop, test, and implement methods to validate their usability. In this paper, we present an exploratory assessment of the urban digital twin NorDark-DT [29], developed to support the sustainable design of green urban lighting infrastructures. The assessment was carried out with MSc students in Architectural Lighting Design through a task-oriented evaluation involving potential users of the tool.

4.1. Overview of the Main Findings

Our results showed that most participants reported moderate to high familiarity with design initiatives, digital tools, and digital twins (Figure 5). Nevertheless, they indicated less experience with the design of interventions for urban green areas, which may represent a limitation to the validity of the conducted assessment. This gap underscores the importance of reinforcing digital tools in education, particularly in architecture and lighting design programs, where exposure to emerging technologies can better prepare students for professional practice and interdisciplinary challenges [40,41]. The digital twin can provide a practical testing environment for evaluating lighting scenarios while also arousing curiosity for obtaining knowledge relevant to urban green areas and more-than-human perspectives in an educational context. Integrating new technological tools into architectural and urban planning education is essential for equipping future professionals with the skills required to address complex urban and environmental challenges [42,43]. Despite participants’ limited experience with certain application domains, their backgrounds in design and planning make this preliminary usability assessment of the NorDark-DT relevant for informing future developments and validations.

Overall, the proposed tasks were perceived as moderate to easy (Figure 6 and Figure 7), with Task-02 considered more complex, likely due to the need to compare luminance maps. This task also required users to save and later reopen a configuration file, making it more demanding. Despite these challenges, participants showed a marked improvement in their understanding of how the digital twin operates as they progressed through the tasks (Figure 8), suggesting that most features become manageable once users gain experience with the tool. To further reduce the learning curve, usability principles and lighting-related terminology from mainstream simulation software, such as Dialux, could be selectively integrated. However, if the long-term aim is to position the digital twin as a tool for broader urban planning applications, reliance on field-specific terms and functions may limit accessibility for non-specialists. In that case, early developments might best focus on intuitive visualization of illuminated environments to support the exploration of future scenarios involving humans, non-humans, and ecological contexts. A balanced incorporation of established lighting principles, while maintaining accessibility for users from diverse professional backgrounds, could strengthen the tool’s utility across both specialized and interdisciplinary domains. In this context, integrating multi-criteria assessment procedures [44] into the digital twin can support participatory and informed decision-making on different lighting scenarios, involving both experts and non-specialists.

Responses to the open-ended questions emphasized that NorDark-DT is particularly valuable for simulating lighting changes before they are implemented in real-world environments. This capability is especially relevant in complex contexts such as outdoor interventions in green spaces, where designers must balance human perception with ecological impacts while evaluating alternative solutions [11,43]. By enabling the visualization of selected light fixtures within realistic environments, the tool offers a practical means to test and refine designs, leading to better-informed decision-making. Its current features, such as importing 3D models and comparing scenarios through luminance maps, further strengthen its utility. However, we acknowledge that luminance is only one photometric parameter, and more nuanced estimations of human visual perception at low light levels, visual comfort, and species-specific responses will require the inclusion of additional metrics in a future, updated version. The current NorDark-DT version functions primarily as an intuitive design tool that integrates standard-relevant calculation features with game engine capabilities; it is a first step toward future capabilities, including identifying and planning of dark corridors and light barriers, simulating spectral characteristics of illumination to evaluate potential influence on humans and other species, and analysing brightness–contrast ratios to assess discomfort glare from various viewpoints. Looking ahead, future developments could enhance the digital twin with more precise and informative visualizations of light effects—such as distribution and colour appearance (and spectral characteristics)—by incorporating additional light source and luminaire data-based metrics and related visual representation.

Overall, the software was widely regarded as a valuable tool, particularly for outdoor lighting projects and for developing a broader understanding of lighting design through visual simulations informed by real-time data from specific testbed sites. It is essential to note that, at this stage, NorDark-DT functioned as a prototype, a “simulated visual representation” rather than a data-driven reflection of reality. Previous studies used a virtual reality tool to assess perceived safety, motivations to visit park environments [45], and subjective visual comfort, combined with fatigue assessment. These studies are evaluated through parameters of illuminance levels and correlated color temperature (CCT) values [45,46]. The results of the studies suggested that various combinations of these parameters could result in different experiences of perceived interest, safety, and exhaustion. The highest light level (10 lx) combined with the warmest (2500 K) and coolest (6500 K) CCTs negatively affected the experience of the study’s participants. The results of the other study indicated that the average illuminance levels defined in the study (2, 6, and 10 lx) were the most important factor in determining physiological fatigue, regardless of CCT (3000, 4300, and 5600 K). However, existing studies examine the various influences of a limited set of lighting parameters in an isolated manner, without taking into account the dynamic, site-specific conditions. The digital twin model could support the implementation of these parameters, along with additional ones relevant for low-light exterior conditions, to facilitate more holistic assessments related to the planning and material conditions of specific exterior sites in the future.

The potential of a digital twin in lighting design practice and education lies in its ability to generate predictive scenarios based on real-time information, illustrating how designed outdoor lighting interacts with various site conditions such as varying weather (e.g., snow cover or rain), sky conditions, and pedestrian or cyclist movement. Previous studies have shown these factors to be relevant in amplifying light pollution under cloud cover [47] while positively affecting human well-being through enhanced natural light exposure from snow cover [48]. Such an interaction would allow planners to analyse, predict, and further implement adaptations while the virtual reality interface remains limited to test a set of conditions in a pre-modelled environment that cannot dynamically reflect the real site circumstances.

Students highlighted that working with an Urban Digital Twin encouraged them to explore aspects of lighting design beyond human perception, such as ecological protection and reduction in light pollution. This broadened perspective not only raised awareness of the environmental implications of design choices but also fostered a more holistic approach to sustainability [41,43]. Furthermore, the collaborative use of the tool in task-oriented exercises was seen as an opportunity to strengthen interdisciplinary skills, as students needed to integrate insights from ecology, technology, and design in their decision-making [40]. However, its closed environment presents challenges for project management and limits integration with mainstream tools commonly used by lighting designers. A further limitation is the requirement for high-performance hardware, which may reduce accessibility for some users. Despite these challenges, participants emphasized the considerable potential of NorDark-DT to enhance lighting design processes and support more sustainable and informed decision-making.

The high level of geometric and visual detail incorporated in the NorDark-DT tool was chosen to more accurately depict a natural forested environment both visually and in terms of simulating the behaviour of light; however, it presents significant challenges in reducing computational demands without compromising visual fidelity.

4.2. Practical Application

The usability evaluation indicates that Nordark-DT is a promising tool for advancing sustainable lighting practices. By integrating environmental, social, and technical considerations, it supports informed assessment of different lighting configurations for urban green outdoor areas. Participants also recognized its value in enhancing understanding of lighting design through visual simulations powered by real-time data from specific testbed sites. In addition, Nordark-DT shows strong potential for use in educational contexts, helping students develop skills in applying sustainability-oriented concepts within their lighting design practices.

4.3. Limitations and Further Developments

The preliminary assessment of NorDark-DT was conducted with students who had limited experience in real-world lighting design for urban green areas, which may have influenced the depth of feedback obtained. Another limitation concerns the absence of a control group, which prevents direct comparison with existing design tools or traditional assessment methods. Future studies should therefore involve professional lighting designers and incorporate controlled, comparative evaluations to more precisely confirm the tool’s effectiveness and generalizability. Expanding evaluations to include participants with mixed levels of expertise and diverse backgrounds could also generate a more comprehensive understanding of digital twin usage, informing both feature refinement and future development directions in educational and professional contexts. For instance, professionals working in outdoor environments may require functions, such as accurate light level calculations or fixture selection aligned with established standards, while educational settings could benefit from the digital twin’s flexibility to experiment with after-dark urban scenarios that move beyond standardized lighting characteristics. Such complementary perspectives highlight the potential of the tool to evolve as both a professional resource and an educational platform, bridging practice and pedagogy in sustainable lighting design.

The usability study was not associated with real-world testing of the lighting interventions explored in the tasks, which limits the ecological validity of the results. Future work could involve evaluating selected lighting alternatives in multiple outdoor sites to better examine their practical implications. This would be particularly beneficial in educational contexts, where hands-on validation of design proposals could further strengthen students’ learning outcomes and contribute to sustainability-focused lighting curricula.

The hardware requirements and their usability implications may impact the practical adoption of the tool in professional and real-world contexts. In its current implementation, the tool employs occlusion culling within Unity 3D to optimize the rendering process by selectively excluding non-visible objects from computation. Further optimization could be achieved through the application of GPU instancing, which enables the rendering of multiple instances of an identical mesh using a single draw call, thereby minimizing CPU overhead. Moreover, the integration of Level of Detail (LoD) components would allow for adaptive mesh complexity based on the viewer’s distance, effectively decreasing vertex processing and enhancing overall rendering performance.

5. Conclusions

New technological developments in urban planning and in the education of future professionals are essential to address emerging societal and environmental challenges. The sustainable design of lighting infrastructure requires balancing human, societal, and economic needs with the preservation of natural ecosystems and biodiversity. In this context, digital tools such as NorDark-DT can play a pivotal role in bridging technology, ecology, and design education. The NorDark-DT prototype used in this study has shown considerable potential as a tool for promoting transdisciplinary skills, enabling students and practitioners to think holistically about the relationships between environment, nature, and human activity when designing lighting interventions. By simulating realistic after-dark urban and natural scenarios, NorDark-DT supports sustainable lighting design while fostering critical reflection on ecological and social impacts.

Although the prototype tool demonstrated clear educational and professional value, future work should include additional parameters relevant to lighting in urban forests as well as broader validation with professionals from diverse disciplines, experience levels, and institutional contexts to further refine its capabilities and ensure its effectiveness in both teaching and real-world urban planning applications.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/buildings15244425/s1, S1: Consent Form; S2: Task Instructions; S3: Questionnaire; S4: NorDark-DT Screenshots.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.V.L.-A., R.d.S.T., A.S. and U.B.; methodology, C.V.L.-A. and R.d.S.T; software, C.V.L.-A., W.N. and A.S.; validation, C.V.L.-A., W.N. and R.d.S.T.; formal analysis, C.V.L.-A. and S.D.; investigation, C.V.L.-A., W.N. and R.d.S.T.; resources, C.V.L.-A., A.S. and R.d.S.T.; data curation, R.d.S.T.; writing—original draft preparation, R.d.S.T. and C.V.L.-A.; writing—review and editing, C.V.L.-A., S.D., W.N. and R.d.S.T.; visualization, C.V.L.-A. and R.d.S.T.; supervision, R.d.S.T and A.S.; project administration, R.d.S.T., A.S. and U.B.; funding acquisition, R.d.S.T. and U.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work has been conducted in the context of the NORDARK project (grant #105116), funded by NordForsk.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Foteini Kyriakidou for granting us the opportunity to conduct this assessment in the context of the HS2008 Light and Space—Outdoor course, at KTH Royal Institute of Technology in Sweden during Fall 2023.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Mansfield, K. Architectural lighting design: A research review over 50 years. Light. Res. Technol. 2018, 50, 80–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isenstadt, S.; Petty, M.M.; Neumann, D. Cities of Light: Two Centuries of Urban Illumination; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K.H.; Hwang, T.; Kim, G. The Role and Criteria of Advanced Street Lighting to Enhance Urban Safety in South Korea. Buildings 2024, 14, 2305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girard, J.; Villa, C.; Brémond, R. Modelling the Probability of Discomfort Due to Glare at All Levels: The Case of Outdoor Lighting. LEUKOS 2023, 19, 368–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jägerbrand, A.K.; Spoelstra, K. Effects of anthropogenic light on species and ecosystems. Science 2023, 380, 1125–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longcore, T.; Rich, C. Ecological light pollution. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2004, 2, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rich, C.; Longcore, T. Ecological Consequences of Artificial Night Lighting; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons, R.; Bhagavathula, R.; Brainard, G.; Hanifin, J.; Warfield, B.; Kassing, A. Investigating the Impacts of Outdoor Lighting; Technical Report; Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University (Virginia Tech): Blacksburg, VA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Lunn, R.M.; Blask, D.E.; Coogan, A.N.; Figueiro, M.G.; Gorman, M.R.; Hall, J.E.; Hansen, J.; Nelson, R.J.; Panda, S.; Smolensky, M.H.; et al. Health consequences of electric lighting practices in the modern world: A report on the National Toxicology Program’s workshop on shift work at night, artificial light at night, and circadian disruption. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 607, 1073–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.; Ryu, S.H.; Lee, B.R.; Kim, K.H.; Lee, E.; Choi, J. Effects of artificial light at night on human health: A literature review of observational and experimental studies applied to exposure assessment. Chronobiol. Int. 2015, 32, 1294–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares, P.; Ingi, D.; Araújo, L.; Pinho, P.; Bhusal, P. Reviewing the Role of Outdoor Lighting in Achieving Sustainable Development Goals. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zielinska-Dabkowska, K.M. Healthier and environmentally responsible sustainable cities and communities. A new design framework and planning approach for urban illumination. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radicchi, A.; Henckel, D. Planning Artificial Light at Night for Pedestrian Visual Diversity in Public Spaces. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afif Supianto, A.; Nasar, W.; Margrethe Aspen, D.; Hasan, A.; Karlsen, A.S.T.; Torres, R.D.S. An Urban Digital Twin Framework for Reference and Planning. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 152444–152465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weil, C.; Bibri, S.E.; Longchamp, R.; Golay, F.; Alahi, A. Urban digital twin challenges: A systematic review and perspectives for sustainable smart cities. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 99, 104862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Major, P.; da Silva Torres, R.; Amundsen, A.; Stadsnes, P.; Mikalsen, E.T. On The Use Of Graphical Digital Twins For Urban Planning Of Mobility Projects: A Case Study From A New District In Åesund, Norway. In Proceedings of the 36th ECMS International Conference on Modelling and Simulation, ECMS 2022, Ålesund, Norway, 30 May–3 June 2022; pp. 236–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musa, A.A.; Malami, S.I.; Alanazi, F.; Ounaies, W.; Alshammari, M.; Haruna, S.I. Sustainable Traffic Management for Smart Cities Using Internet-of-Things-Oriented Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITS): Challenges and Recommendations. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Ma, L.; Broyd, T.; Chen, W.; Luo, H. Digital twin enabled sustainable urban road planning. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 78, 103645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leplat, L.; da Silva Torres, R.; Aspen, D.; Amundsen, A. GENOR: A Generic Platform For Indicator Assessment In City Planning. In Proceedings of the 36th ECMS International Conference on Modelling and Simulation, ECMS 2022, Ålesund, Norway, 30 May–3 June 2022; pp. 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofia, H.; Anas, E.; Faïz, O. Mobile mapping, machine learning and digital twin for road infrastructure monitoring and maintenance: Case study of mohammed VI bridge in Morocco. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference of Moroccan Geomatics (Morgeo), Casablanca, Morocco, 11–13 May 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, B.; Yu, J.; Chen, Z.; Osman, A.I.; Farghali, M.; Ihara, I.; Hamza, E.H.; Rooney, D.W.; Yap, P.S. Artificial intelligence for waste management in smart cities: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2023, 21, 1959–1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasar, W.; Karlsen, A.S.T.; Hameed, I.A. A Conceptual Model Of An IOT-Based Smart And Sustainable Solid Waste Management System: A case Study Of A Norwegian Municipality. In Proceedings of the 34th International ECMS Conference on Modelling and Simulation, ECMS 2020, Wildau, Germany, 9–12 June 2020; Steglich, M., Mueller, C., Neumann, G., Walther, M., Eds.; pp. 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cárdenas-León, I.; Koeva, M.; Nourian, P.; Davey, C. Urban digital twin-based solution using geospatial information for solid waste management. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 115, 105798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosamo, H.; Mazzetto, S. Integrating Knowledge Graphs and Digital Twins for Heritage Building Conservation. Buildings 2025, 15, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barresi, A. Urban Digital Twin and urban planning for sustainable cities. TECHNE-J. Technol. Archit. Environ. 2023, 25, 78–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.; Du, J.; Han, Y.; Newman, G.; Retchless, D.; Zou, L.; Ham, Y.; Cai, Z. Developing human-centered urban digital twins for community infrastructure resilience: A research agenda. J. Plan. Lit. 2023, 38, 187–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.U.; Angelaki, S.; Alfaro, C.V.L.; Major, P.; Styve, A.; Alaliyat, S.A.A.; Hameed, I.A.; Besenecker, U.; da Silva Torres, R. Digital Twins For Lighting Analysis: Literature Review, Challenges, And Research Opportunities. In Proceedings of the 36th ECMS International Conference on Modelling and Simulation, ECMS 2022, Ålesund, Norway, 30 May–3 June 2022; pp. 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; López-Alfaro, C.V.; da Silva Torres, R. Urban Lighting Infrastructure Analysis Using Topology Density Maps. In Proceedings of the 38th ECMS International Conference on Modelling and Simulation, ECMS, Cracow, Poland, 4–7 June 2024; Volume 38, pp. 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leplat, L.; López-Alfaro, C.; Styve, A.; da Silva Torres, R. NorDark-DT: A digital twin for urban lighting infrastructure planning and analysis. Environ. Plan. B Urban Anal. City Sci. 2025, 52, 667–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabbah, A.; Fischl, G.; Aries, M. Evaluating Digital Twin light quantity data exchange between a virtual and physical environment. In Proceedings of the E3S Web of Conferences, BuildSim Nordic 2022. EDP Sciences, Copenhagen, Denmark, 22–23 August 2022; Volume 362, p. 08005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Cui, Z.; Hao, L. Virtual reality in lighting research: Comparing physical and virtual lighting environments. Light. Res. Technol. 2019, 51, 820–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellazzi, A.; Bellia, L.; Chinazzo, G.; Corbisiero, F.; D’Agostino, P.; Devitofrancesco, A.; Fragliasso, F.; Ghellere, M.; Megale, V.; Salamone, F. Virtual reality for assessing visual quality and lighting perception: A systematic review. Build. Environ. 2022, 209, 108674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scorpio, M.; Laffi, R.; Teimoorzadeh, A.; Ciampi, G.; Masullo, M.; Sibilio, S. A calibration methodology for light sources aimed at using immersive virtual reality game engine as a tool for lighting design in buildings. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 48, 103998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Ibáñez, L.; Barneche-Naya, V. Real-Time Lighting Analysis for Design and Education Using a Game Engine. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction, Copenhagen, Denmark, 23–28 July 2023; pp. 70–81. [Google Scholar]

- Scorpio, M.; Carleo, D.; Gargiulo, M.; Navarro, P.C.; Spanodimitriou, Y.; Sabet, P.; Masullo, M.; Ciampi, G. A review of subjective assessments in virtual reality for lighting research. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosson, M.B.; Carroll, J.M. Usability Engineering: Scenario-Based Development of Human-Computer Interaction; Morgan Kaufmann Publishers Inc.: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Dagienė, V.; Sentance, S. It’s Computational Thinking! Bebras Tasks in the Curriculum. In Proceedings of the Informatics in Schools: Improvement of Informatics Knowledge and Perception, Münster, Germany, 13–15 October 2016; Brodnik, A., Tort, F., Eds.; pp. 28–39. [Google Scholar]

- Mäkiö, E.; Mäkiö, J. The Task-Based Approach to Teaching Critical Thinking for Computer Science Students. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loorbach, D. Transition management for sustainable development: A prescriptive, complexity-based governance framework. Governance 2010, 23, 161–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lönngren, J. Wicked Problems in Engineering Education: Preparing Future Engineers to Work for Sustainability. Ph.D. Thesis, Chalmers Tekniska Högskola, Gothenburg, Sweden, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Giaccardi, E.; Redström, J. Technology and more-than-human design. Des. Issues 2020, 36, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salama, A.M. Spatial Design Education: New Directions for Pedagogy in Architecture and Beyond; Ashgate: Surrey, UK; Burlington, VT, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Fieuw, W.; Foth, M.; Caldwell, G.A. Towards a more-than-human approach to smart and sustainable urban development: Designing for multispecies justice. Sustainability 2022, 14, 948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pracki, P.; Skarżyński, K. A Multi-Criteria Assessment Procedure for Outdoor Lighting at the Design Stage. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masullo, M.; Cioffi, F.; Li, J.; Maffei, L.; Scorpio, M.; Iachini, T.; Ruggiero, G.; Malferà, A.; Ruotolo, F. An Investigation of the Influence of the Night Lighting in a Urban Park on Individuals’ Emotions. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarrete-de Galvez, E.; Gago-Calderon, A.; Garcia-Ceballos, L.; Contreras-Lopez, M.A.; Andres-Diaz, J.R. Adjustment of lighting parameters from photopic to mesopic values in outdoor lighting installations strategy and associated evaluation of variation in energy needs. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyba, C.C.M.; Kuester, T.; de Miguel, A.S.; Baugh, K.; Jechow, A.; Hölker, F.; Bennie, J.; Elvidge, C.D.; Gaston, K.J.; Guanter, L. Artificially lit surface of Earth at night increasing in radiance and extent. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, e1701528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lowden, A.; Dincel, S. The Snowball Effect: Snow cover increases light exposure, suppresses melatonin, and improves alertness in an urban population at northern latitudes. Chronobiol. Int. 2025, 42, 1699–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).