Study on the Dynamic Mechanical Properties of Polypropylene Fiber-Reinforced Concrete Based on a 3D Microscopic Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Establishment of the PFRC Microscopic Model

2.1. Preparation of Test Specimens

2.2. Generation and Placement of Polyhedral Aggregate

2.3. Grid Recognition

2.4. Fiber Generation

2.5. Determination of Material Parameters

2.6. Model Validity Verification

3. Analysis of Simulation Results

3.1. Characteristics of Stress–Strain Curves

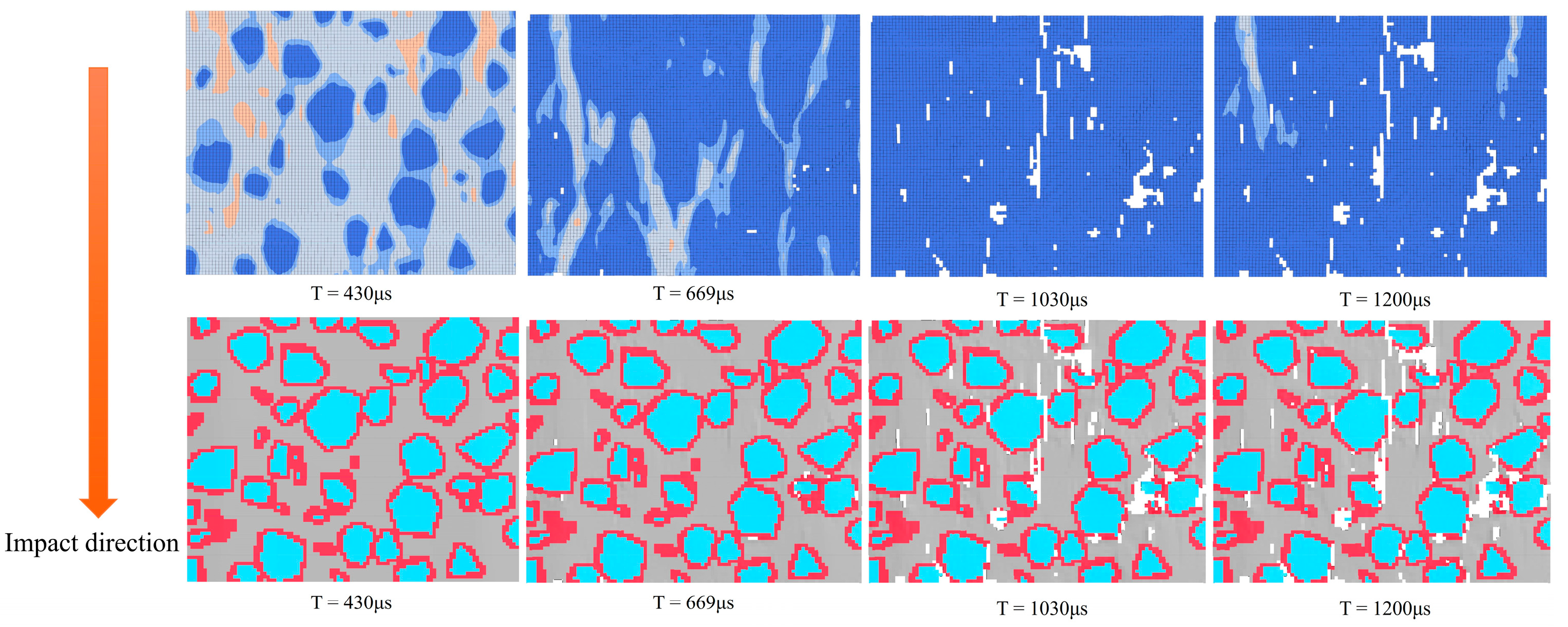

3.2. Destructive Characteristics

3.3. Energy Characteristics

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- The simulated results exhibit close agreement with the experimental data in terms of peak stress, peak strain, and failure characteristics.

- (2)

- The incorporation of 0.1% polypropylene fibers significantly enhanced the dynamic compressive strength of the specimen by 24.45%, with a mere 2.10% deviation from the experimental measurement. When the impact velocity was increased to 8 m/s and 10 m/s, the peak stress showed increases of 6.14% and 22.62%, respectively, while the peak strain increased by 11.72% and 23.32%.

- (3)

- As the impact velocity increased, the aggregates exhibited limited damage. Cracking primarily initiated and propagated through the mortar and the ITZ. Concurrently, the stress sustained by the polypropylene fibers also increased with the higher impact velocity.

- (4)

- The polypropylene fibers improved the dynamic mechanical performance by dissipating energy through both fiber fracture and pull-out mechanisms. Furthermore, as the impact velocity increased, the fibers absorbed more energy, leading to a progressive increase in their own damage.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xu, Z.; Wu, C.; Yu, M.; Ran, Q.; Liu, L. Dynamic compressive behavior and energy absorption of SFRC. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 106, 112554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Cai, Y.; Chen, X.; Liang, J.; Xu, Z. Study on high temperature dynamic characteristics and mesoscopic simulation of HFRC under dynamic and static combined loading. Structures 2024, 60, 105824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.; Hamoda, A.; Yehia, S.A.; Shahin, R.I.; Abadel, A.A.; Chen, W.; Zhang, X. Flexural performance of rubberized fiber-reinforced concrete beams incorporating macro synthetic fibers. Structures 2025, 82, 110566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Wang, J.; Shen, Q.; Li, B.; Liu, Y. Mechanical analysis of eccentrically loaded SFRC columns reinforced by high-strength rebars: Testing and FE modelling. Eng. Struct. 2025, 343, 121042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, S.; Chen, W.; Gao, Y.; Meng, F.; Hou, J.; Li, Q.; Dou, Y. Dual tannic acid-based modification strategy for enhanced mechanical properties of basalt fiber/epoxy composites. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2026, 200, 109345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, D.; Pleesudjai, C.; Bui, V.; Pridemore, P.; Schaef, S.; Mobasher, B. Mechanical response of precast tunnel segments with steel and synthetic macro-fibers. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2023, 144, 105303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, W.; Qian, C. Atomic-level insights into the mechanism by which synthetic organic fibers enhance the tensile strength of concrete. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 75, 106891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Liu, C.; Zhang, G.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, Z.; Li, N. Strain-rate-dependent performances of polypropylene-basalt hybrid fibers reinforced concrete under dynamic splitting tension. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 96, 110654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Xukun, M.; Chulei, F.; Na, L.; Wei, T.; Fuyong, C.; Ping, J.; Guoxiong, M. Mechanical characteristics and microscopic mechanism of polypropylene fiber modified recycled road solid waste fine aggregate mortar. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 97, 110798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, X.; Shi, Y.; Lu, H.; Hao, R.; Zhang, H.; Chen, W.; Liu, Y. Research on the Impact Performance of Polypropylene Fiber-Reinforced Concrete Composite Wall Panels. Buildings 2025, 15, 3983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Huang, B.; Li, B.; Chi, Y.; Li, C.; Shi, Y. Study on the stress-strain relation of polypropylene fiber reinforced concrete under cyclic compression. China Civ. Eng. J. 2019, 52, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, Y.; Song, H.; Liu, Q.; Bai, Y.; Zhang, P. Experimental study on blending ratio and mechanical properties of high toughness polypropylene fiber concrete. Mater. Rep. 2024, 38, 657–661. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, J.; Wang, L.; Li, Z.; Zhang, J.; Chi, J. Toughness of polypropylene fiber-reinforced coral concrete. J. Build. Mater. 2024, 27, 913–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Ke, W.; Liang, N.; Miao, Q.; Yang, P.; Guo, Z. Study on the dynamic mechanical properties of concrete multi size polypropylene fiber based on SHPB Test. Mater. Rep. 2018, 32, 484–489. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Zhu, C.; Chen, X.; Guo, J.; Jiao, H. Dynamic mechanical behavior of polypropylene fiber-reinforced shotcrete: Experimental analysis, microstructural observation, and numerical simulation. Results Eng. 2025, 27, 106363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseinzadehfard, E.; Mobaraki, B. Corrosion performance and strain behavior of reinforced concrete: Effect of natural pozzolan as partial substitute for microsilica in concrete mixtures. Structures 2025, 79, 109397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrabhan, S.; Pramod Kumar, G. Biaxial behaviour of concrete and its failure mechanics under quasi-static and dynamic loading: A numerical study. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2024, 300, 109931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, C.; Gupta, P.K. Numerical analysis of failure mechanics of concrete under true dynamic triaxial loading using a four-phase meso-model. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 450, 138661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, L.; Yu, W.; Du, X. Effect of the sudden increase of strain rate on concrete dynamic tensile failure based on 3D meso-scale simulation. J. Vib. Shock 2021, 40, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, R.; Ren, H.; Zhang, L.; Long, Z.; Wu, X.; Li, Z. Simulation for SHPB tests based on a mesoscopic concrete aggregate model. J. Vib. Shock 2019, 38, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, R.; Ren, H.; Zhang, L.; Long, Z.; Jiang, X.; Wu, X.; Wang, H. Direct dynamic tensile study of concrete materials based on mesoscale model. Int. J. Impact Eng. 2020, 143, 103598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Yang, F.; Li, X. Simulation of Dynamic Mechanical Properties of Sustainable Lightweight Aggregate Concrete with Mesoscopic Model. Infrastructures 2024, 9, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Cheng, Y.; Wu, H. Analysis on dynamic compressive behavior of concrete based on a 3D mesoscale model. Explos. Shock. Waves 2024, 44, 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, T.; Wen, J.; Tan, Y. Dynamic damage mechanism of basic magnesium sulfate cement composites: Experiments and 3D mesoscopic modeling study. Mech. Mater. 2024, 194, 105011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Guo, Y.; Shao, Z.; Qiao, R.; Zhou, H. Study on mesoscopic modeling method and mechanical properties of steel fiber reinforced concrete. Chin. J. Appl. Mech. 2024, 41, 868–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JGJ 55-2011; Specification for Mix Proportion Design of Ordinary Concrete. China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2011.

- Ma, W.; Gao, D.; Chen, C.; Guo, Y.; Yang, L.; Fang, D. Preparation and durability of hydrophobically modified nanocellulose/epoxy vinyl resin composites: Multi-scale analysis in simulated pore solution of seawater sand concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 498, 143997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebedev, V.; Miroshnichenko, D.; Vytrykush, N.; Pyshyev, S.; Masikevych, A.; Filenko, O.; Tsereniuk, O.; Lysenko, L. Novel biodegradable polymers modified by humic acids. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2024, 313, 128778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Z.; Zhou, M. Mesoscopic modeling method of concrete aggregates with arbitrary shapes based on mesh generation. Chin. J. Comput. Mech. 2017, 34, 591–596. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Li, Z.; Li, H.; He, M.; Gao, W.; Zhou, J.; Xu, Z. Dynamic response of concrete materials at high strain rates: Experimental and numerical studies. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2025, 330, 111606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Yu, H.; Ma, H. 3D mesoscopic investigation of the specimen aspect-ratio effect on the compressive behavior of coral aggregate concrete. Compos. Part B Eng. 2020, 198, 108025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, L.; Jia, L.; Zhang, R.; Yu, W.; Du, X. Mechanical behavior of steel fiber reinforced concrete at cryogenic temperatures: Characterization with 3D meso-scale modelling. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2024, 219, 104110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Wu, C.; Yu, M.; Liu, C.; Qi, W.; Liu, L. Static Mechanical properties of rock–concrete composite specimens after high-temperature treatment. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2025; early access. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, J.; Xu, Y.; Xiao, J.; Jian, Y. Multiscale damage evolution and crack propagation mechanisms in recycled concrete under static and dynamic loading: A cohesive zone model approach. Compos. Struct. 2026, 375, 119771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alessio, C.; Salvatore, V.; Luciano, O.; Aiello, M.A. Carbon Fabric Reinforced Cementitious Mortar confinement of concrete cylinders: The matrix effect for multi-ply wrapping. Compos. Struct. 2024, 332, 117919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Density (g/cm3) | Length (mm) | Diameter (mm) | Tensile Strength (MPa) | Elastic Modulus (GPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.9 | 12 | 0.02 | 556 | 8.8 |

| Cement | Water | Sand | Crushed Stone | Fly Ash | Water-Reducing Admixture | PF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 463 | 185 | 541 | 1261 | 93 | 2.3 | 1.0 |

| Basic Parameters | Density (kg/m3) | Compressive Strength (MPa) | Poisson’s Ratio | B1 | B2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mortar | 2300 | 31.5 | 0.25 | 1.60 | 1.35 |

| ITZ | 2300 | 25.2 | 0.25 | 1.40 | 1.20 |

| EOS Parameters | Modulus 1 (N/m3) | Modulus 2 (N/m3) | Modulus 3 (N/m3) | Modulus 4 (N/m3) | Modulus 5 (N/m3) |

| mortar | 1.43 | 1.43 | 1.45 | 1.52 | 1.81 |

| ITZ | 1.28 | 1.28 | 1.29 | 1.36 | 1.61 |

| Parameter | A | B | N | K1 (GPa) | K2 (GPa) | K3 (GPa) | (MPa) | (GPa) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| value | 0.9 | 2.0 | 0.65 | 14 | 20 | 25 | 53 | 0.0012 | 0.8 | 0.01 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, S.; Du, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; Dong, Z. Study on the Dynamic Mechanical Properties of Polypropylene Fiber-Reinforced Concrete Based on a 3D Microscopic Model. Buildings 2025, 15, 4427. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244427

Liu S, Du Z, Wang Y, Wang J, Dong Z. Study on the Dynamic Mechanical Properties of Polypropylene Fiber-Reinforced Concrete Based on a 3D Microscopic Model. Buildings. 2025; 15(24):4427. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244427

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Shiliang, Zhimin Du, Yanan Wang, Jiawei Wang, and Zhibo Dong. 2025. "Study on the Dynamic Mechanical Properties of Polypropylene Fiber-Reinforced Concrete Based on a 3D Microscopic Model" Buildings 15, no. 24: 4427. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244427

APA StyleLiu, S., Du, Z., Wang, Y., Wang, J., & Dong, Z. (2025). Study on the Dynamic Mechanical Properties of Polypropylene Fiber-Reinforced Concrete Based on a 3D Microscopic Model. Buildings, 15(24), 4427. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15244427