Abstract

In Latin America, informal urbanization on hillsides has given rise to unique forms of occupation that combine constructive precariousness with social creativity. This study analyzes the Los Portales del Mirador settlement in Arequipa, Peru, from the theoretical framework of the social production of space of Lefebvre, examining how technical adaptations become social spaces. The research used methodological triangulation through urban cartography, a structured visual study of 548 lots, non-participatory observation, and 72 semi-structured interviews. The results identify specific settlement patterns and demonstrate how technical elements such as stairs, platforms, and retaining walls, initially designed for stabilization and accessibility, are progressively transformed into semi-communal spaces that facilitate encounters, strengthen neighborhood cohesion, and build collective identity. The study concludes that topography operates simultaneously as a limitation and a catalyst for social creativity, demonstrating how the self-production of space in informal contexts generates specific forms of sociability that challenge traditional dichotomies between public and private space.

1. Introduction

Social interactions are fundamental to shaping informal spaces within urban settlements, a process that finds its most solid theoretical framework in Henri Lefebvre’s theory of the social production of space. Contrary to views that conceive space as a neutral container for social activities, Lefebvre [1] posits that space is a complex social product, the result of the dialectical triad between spatial practices (everyday experience), representations of space (space as conceived by technicians and planners), and spaces of representation (space as experienced and signified by its users). This perspective is particularly relevant for analyzing informal settlements on hillsides, where the apparent ‘lack’ of formal planning does not equate to an absence of spatial production. As Lindón [2] pointed out, these exchanges transform places into spaces for meeting, coexistence and socialisation, a phenomenon that can be interpreted as a form of Lefebvrian ‘right to the city’, where inhabitants actively appropriate their environment. Similarly, Clichevsky’s [3] analysis of the interrelated factors that affect quality of life in urban informality highlights the need to examine how these spaces are configured in difficult contexts, a task that requires understanding them not as deficits, but as the result of specific social production and material struggles for urban existence.

In Latin America, and particularly in Peru, a knowledge gap persists regarding the factors that contribute to the formation of social spaces in informal hillside settlements. The city of Arequipa, located in southern Peru, offers a paradigmatic case: its recent urban expansion has been driven by processes of self-managed housing in these areas, where the technical challenges of stabilization and accessibility coexist with opportunities for social interaction and community life. Several authors have explored the relationship between informality and space. Velarde Hertz [4] and Hernández García [5] analyzed the impact of individual housing interventions, although without examining in depth the detailed processes of creation or their social implications. In this regard, Abramo [6] and Schroeder [7] emphasize that everyday dynamics and specific social practices influence the evolution of spaces situated between the street and the dwelling. In this sense, the central question guiding this work is: how do construction adaptations, initially conceived as technical responses to the challenges of building on steep slopes, transform, through social practices, into semi-community spaces that foster interaction and neighborhood cohesion? Exploring this question from a Lefebvrian framework allows for a better understanding of the social implications of self-production of space in informal urban contexts, illuminating the process by which physical space is appropriated and endowed with collective meaning.

1.1. Community Development in Informal Neighborhoods

In Latin America, self-production of public space is emerging as a collective response to an urban planning model that, conditioned by exclusionary zoning policies, privileges areas with high property values and relegates the periphery to conditions of precariousness and invisibility [8,9]. Informal hillside neighborhoods emerge precisely from the need to access life opportunities, but they face profound inequalities due to the chronic absence of basic infrastructure and adequate services [10]. In this context, institutional interventions, often focused on quantitative indicators rather than the overall quality of the habitat, are not only insufficient but in many cases reinforce the stigmatization of these territories, perceiving them as unsafe or unsuitable for neighborhood life [11,12].

Faced with this reality, communities develop forms of self-production that allow them to progressively consolidate their territories, where social capital stands as a fundamental resource for organizing collective solutions and negotiating demands with the state [13]. Consequently, space in these environments cannot be understood solely in its physical dimension, but evolves as the tangible result of everyday practices, negotiations, and collective learning [14,15]. This dynamic reveals an inseparable relationship between residents and their territory, where daily interactions generate changing meanings and uses, transforming the act of inhabiting into a process of ephemeral and permanent appropriation [16]. In this way, everyday life shapes a distinctive urbanism, where each social practice produces a unique space, transforming these neighborhoods into living organisms whose consolidation is based on continuous learning rooted in experience and necessity [17].

Contextualizing this issue in Peru, the phenomenon acquires specific nuances deeply rooted in its socio-political reality. The historical analysis of Lima’s marginal neighborhoods, Riofrío [18] shows that their growth was not chaotic, but rather a sequence of self-organization to access land and create a viable habitat. However, this capacity for community agency, quantified and characterized by Robert and Sierra [19], develops in a scenario where vulnerability is actively constructed and reinforced by institutional action. Thus, the creation of community spaces on the slopes of Peru reveals itself as an act with a double meaning: it is the materialization of self-organization to address critical shortcomings, evidenced in case studies such as the San Augustin Human Settlement analyzed by Fiori, Riley and Ramírez [20] and, simultaneously, a form of resistance that produces social cohesion in the face of the forces that perpetuate its marginalization.

1.2. Adaptation of Housing in Informal Hillside Settlements

Self-built housing symbolizes both the assertion of family dignity and the right of citizens to a decent space in the absence of an adequate state response. Although provisional and limited, these dwellings mitigate the housing needs of marginalized sectors [21,22]. Self-production allows residents to transform provisional shelters into habitable homes [17]. These houses are managed practically and empirically, adapting to diverse contexts. Despite their limitations, they respond to territorial logics through “bottom-up urbanism,” prioritizing private space (housing) first and public space (infrastructure and open areas) second, evolving in parallel with the individual, neighborhood needs, and the environment [23].

Over time, housing technology improves; although originally constructed with precarious modules, they are eventually consolidated with durable construction materials [17]. According to Castro and Perdomo [24], confined masonry and empirical constructive practices predominate in the Peruvian context. Design and construction are entrusted to neighbors who work in construction. This highlights the self-help logic described by Salas, Salazar, and Peña [17], whereby residents play a central role in building their houses, becoming both designers and builders by using their own resources. Community work and social relationships are crucial, since the development of housing depends on collective learning, community connections, and empirically tested solutions adapted to the territorial context (Figure 1).

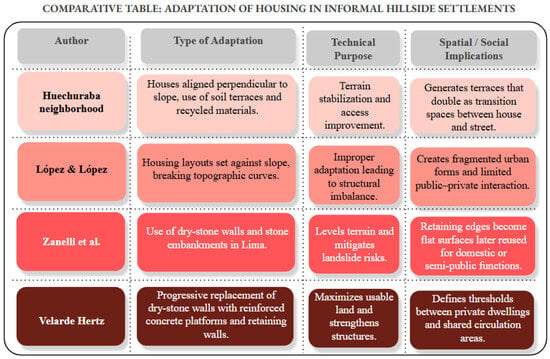

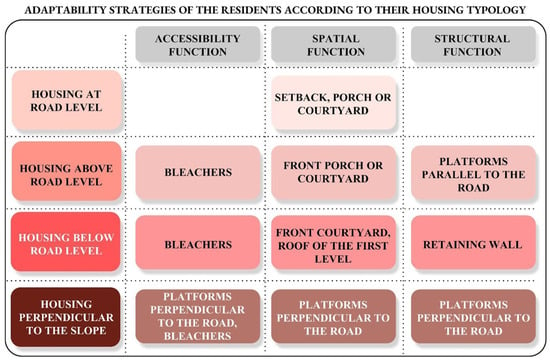

Figure 1.

Comparative table: adaptation of housing in informal hillside settlements [4,25,26,27].

The forms of housing adaptation to informal hillsides are influenced by cultural, economic, and geographic factors. The neighborhood of Huechuraba demonstrates how dwellings adapt to hillside curves, are placed perpendicular to the slope, and use soil terraces or discarded materials to stabilize the terrain [25]. However, López and López [26] highlighted deficiencies in housing layouts, which are often set against the slope, breaking topographic curves and generating imbalances (Figure 1).

In the cited examples, hillside housing consistently seeks to level the ground. In the work of Zanelli et al. [27], the use of dry-stone walls and stone embankments in Lima is emphasized; these elements serve two functions: leveling dwellings and adapting them to hillside risks, although the latter was questioned in their study. Velarde Hertz [4] also noted the use of platforms in housing settlements, observing a pattern in which small modules are initially built on dry-stone walls and, as they consolidate, platforms of reinforced concrete and retaining walls are introduced to maximize available terrain (Figure 1).

In summary, the forms of housing adaptation in informal hillside settlements reveal a process in which the technical and the social are inseparably intertwined. The resources initially arise from the need to level terrain and guarantee habitability; however, the manner in which this adaptation is resolved proves decisive, as it requires establishing a direct connection between houses and streets. This inevitable relationship not only defines the physical configuration of the dwelling but also influences the dynamics of social and community life, given that the street is always present in housing design (Figure 1).

1.3. Semi-Communal Spaces

In its traditional definition, public space refers to collectively owned areas such as parks, squares, or streets, whose access is open to all citizens without discrimination [28]. In this sense, relying solely on the notion of public space is inadequate, since in this context public spaces are often neglected: officially designated areas are minimal, residual, or lack effective use due to overcrowding and topography [26,29].

The absence of public space does not eliminate the need for interaction. On the contrary, it is channeled into places not originally conceived for such purposes—streets, sidewalks, scattered residual areas, and so on [4]. This introduces the concept of social spaces, for as Delgado [30], Hernández García [31], and Lindón [2] argue, what matters is not whether spaces are public or private, but their capacity to foster interactions, encounters, and community cohesion. Such spaces may emerge both within private domains and in unplanned interstices.

At this point, the concept of semi-communal spaces becomes relevant. Semi-communal spaces arise in hillside settlements through the incomplete self-construction of housing and the adaptation of terrain, functioning as hybrid extensions between the private and the collective. Although belonging to the domestic sphere, they sustain community dynamics by becoming points of gathering, observation, and daily coexistence, forming a diffuse network of neighborhood life that replaces or complements the absence of conventional public spaces [4,32].

In urban literature, the concepts of interstitial and intermediate spaces have mainly been approached from a morphological perspective. Solà-Morales [33], in introducing the term terrain vague, characterizes interstices as urban voids, fragments without a defined function. Similarly, Hertzberger [34] developed the notion of “in-between” spaces to describe architectural transition areas such as portals, corridors, or courtyards, which serve as formal articulators between private and public spheres without deepening into their social re-signification.

In contrast, the term semi-communal spaces makes visible the social dimension these places acquire in the context of informal neighborhoods. They originate from the partial non-appropriation of land, leaving thresholds that invite community relations [4].

For these reasons, this article adopts the term semi-communal spaces as its primary category, recognizing that what is essential in these areas is not merely their location “between” the dwelling and the street, but their capacity to become scenarios of community life in contexts of urban informality.

In this sense, semi-communal spaces are not conceived solely as transitional realms between housing and the street, but, as Delgado [35] stresses, they become authentic social spaces which, in the absence of consolidated public infrastructure, highlight that public space is “made” in everyday practice, in the crossings, encounters, and conflicts that occur within it.

Unlike the terrain vague described by Solà-Morales [33], which represent urban voids lacking defined use or meaning, semi-communal spaces do not arise from the absence of function but from an excess of everyday appropriation. In these spaces, daily life reconfigures areas that were initially technical or residual into places of interaction and belonging. Nor do they fully resemble Hertzberger’s [34] in-between spaces, conceived as planned architectural transitions between private and public realms. In informal hillside contexts, semi-communal spaces are not the result of intentional design but of empirical practice: they emerge when the boundaries between house and street become blurred, acquiring meaning through collective use.

From an operational perspective, they are defined as spaces that are:

- (a)

- Physically linked to the dwelling (platforms, stairways, setbacks, or front patios);

- (b)

- Not formally regulated by the state nor professionally designed;

- (c)

- Shared by neighbors for circulation, rest, play, or social encounter;

- (d)

- Collectively maintained or appropriated, showing some degree of personalization or communal care.

These criteria make semi-communal spaces distinguishable from other spatial categories and analytically verifiable in the field, integrating the morphological and social dimensions in the study of informal hillside settlements.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Case Study: Informal Settlement “Los Portales Del Mirador”

In the Peruvian context, informal settlements tend to be located on peripheral hillsides, as urban centralization drives expansion into non-urbanizable edges. Cases such as Nicolás de Piérola in the Quirio ravine, Los Cañaverales on the banks of the Rímac River, or San Gabriel Alto in Villa María del Triunfo demonstrate how improvised construction on rocky or unstable land generates constant risks of landslides and collapses [36,37]. The occupation of these hillsides responds to the lack of safe housing alternatives and to urban models that fail to provide adequate forms of peripheral expansion, thereby increasing the vulnerability of these nuclei [38,39,40].

In the city of Arequipa, in southern Peru, informal urban expansion into hillside zones has led to the formation of true “informal islands”. These areas develop in a fragmented manner because peripheral slopes are isolated from one another, and centrality is broken by ravines, alluvial cones, and topographic voids that reinforce territorial fragmentation and hinder integration with the consolidated city. The Arequipa region is highly seismic, and seasonal rain increases the vulnerability of these settlements, as noted in reports by INDECI [41,42].

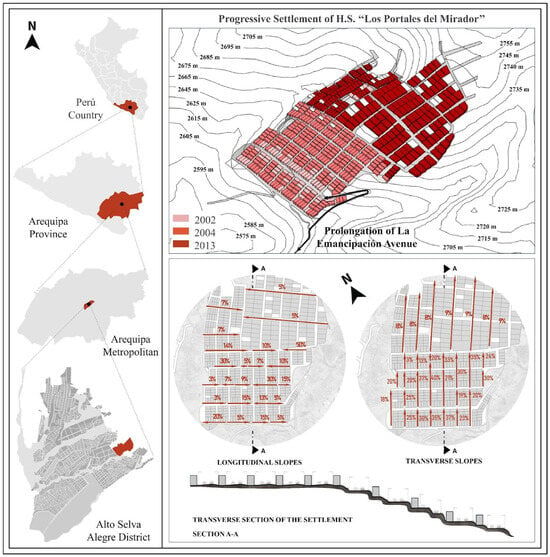

The case study corresponds to the informal settlement Los Portales del Mirador, located in the upper area of the Alto Selva Alegre district, one of the peripheral districts of the province of Arequipa. It is a territory with irregular morphology, steep slopes, and traversed by dry watercourses locally known as torrenteras, which surround the entire neighborhood and accentuate its exposure to natural disasters [43,44].

The settlement occupies approximately 26 hectares, delimited by cliffs, ravines, and the slopes of the Misti volcano (a geographic landmark in the city with strong symbolic meaning in Andean tradition, but also a latent risk due to its proximity to the neighborhood). The neighborhood has a single main access road, Prolongación de la Av. La Emancipación, which conditions its connectivity with the rest of the city.

Founded in 2004 with 41 initial lots that hosted 41 families distributed across 14 blocks, the settlement has grown rapidly, and by 2024 accommodates 548 families in 589 lots and 58 blocks, organized in an orthogonal grid. The topography presents slopes ranging from 7% to 30%, mostly transversal, which conditions both self-construction practices and the creation of transitional spaces between dwellings and streets (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Representation of the location, settlement process, and morphology of Los Portales de Mirador.

The community is notable for its organizational capacity, evidenced by infrastructure works carried out collectively, such as roads and sidewalks, as well as the construction of two community facilities: a communal hall that also functions as a kindergarten, and a popular dining hall. In addition, there are three open spaces designated for recreation: a sports field, a playground, and a multi-use sports court.

Nevertheless, these normative spaces face serious limitations in becoming genuine arenas of social encounter. Their daily use is limited due to peripheral location, lack of maintenance, and minimal physical conditions that prevent adequate community appropriation.

According to the typology proposed by Lozano [45], informal settlements go through three stages of progressive housing consolidation:

- (a)

- An initial phase, characterized by precarious constructions with light materials such as wood, mats, or dry-stone walls;

- (b)

- A transformation phase, in which housing is expanded incrementally through self-management and partial use of confined masonry;

- (c)

- A consolidation phase, in which confined masonry buildings with lightweight slab roofs predominate, allowing the addition of upper floors.

In Los Portales del Mirador, these stages are distributed as follows: 20% of the dwellings are in the initial phase, 62% in transformation, and 18% in consolidation. Additionally, 6.9% of the lots remain undeveloped. Regarding basic services, approximately half of the dwellings (50%) have direct access to water, sewage, and electricity, highlighting an incomplete urbanization process.

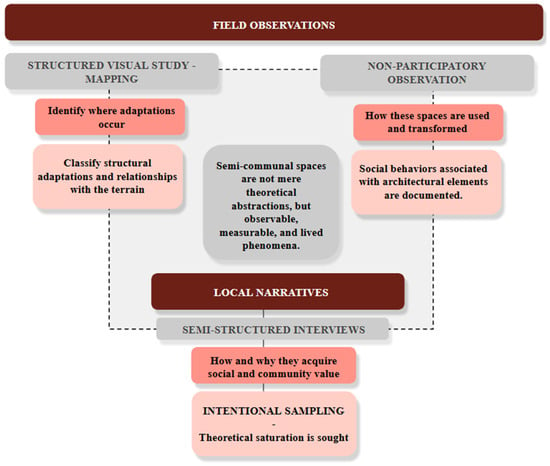

The design incorporated systematic methodological triangulation between quantitative techniques (structured visual study, mapping) and qualitative techniques (observation, interviews). An integrated sequential process allowed findings to be contrasted and validated through the convergence of evidence from multiple sources and methods.

2.2. Structured Visual Study

A physical–spatial analysis was conducted of 548 of the 589 lots in the settlement. A structured visual study was carried out over four months, from March to August 2022. This was complemented by terrestrial photogrammetry for all built houses and vacant lots in the study area. This procedure allowed for defining the dimensions, location, materials, and constructive condition of each dwelling, as well as its immediate context [46].

In parallel, an observation sheet was used to systematically record different relevant aspects of the dwellings [47]. The following were observed for each dwelling.

- Location;

- Nearby slopes;

- Form of hillside adaptation;

- Consolidation stage;

- Number of floors;

- Construction condition;

- Transitional space between the dwelling and the public road.

2.3. Mapping

The information collected in the structured visual study were carried out through mapping, in order to graphically represent deficiencies and potentials of the case study.

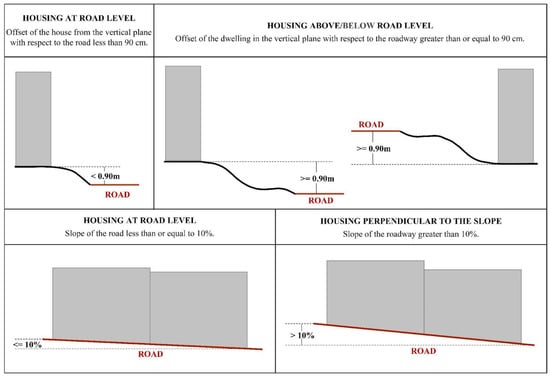

The processing and synthesis of the information collected in the structured visual study were carried out through mapping, in order to graphically represent deficiencies and potentials of the case study [48,49]. The analysis was conducted between September and 10 November 2022. The main objective was to differentiate settlement patterns of dwellings and their position on the horizontal plane, as well as the vertical plane, where a minimum displacement of 0.90 m was considered to define whether a dwelling was located above or below the street. Likewise, a road slope greater than 10% in front of the dwelling was used to identify the typology of dwellings perpendicular to the slope (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Representation of principle used to classify the settlement Types.

2.4. Non-Participatory Observation

After identifying settlement patterns, the characteristics of each were carefully observed. The steep slopes of the settlement allowed for broad visual coverage from upper streets toward the houses below. For each settlement pattern, the following were noted:

- Condition of the surrounding street;

- Location and land occupation percentage of the construction;

- Similarity or difference in organization compared to formal housing;

- Function assigned to a space according to the settlement pattern;

- Hillside dwelling adaptation characteristics;

- Uses of semi-communal spaces.

2.5. Semi-Structured Interviews

To deepen the quantitative and spatial findings, 72 semi-structured interviews were conducted to explore the residents’ narratives, lived experiences, and the social meanings attached to semi-communal spaces. This method was selected for its capacity to combine a consistent thematic guide with the flexibility to probe emergent themes [50,51], thereby enabling a nuanced understanding of the “how” and “why” behind spatial practices. Participants were selected through purposive sampling to capture a diverse range of profiles, including different ages, genders, lengths of residence, and roles. All of whom actively used or possessed a semi-communal space. Sampling continued until theoretical saturation was reached, ensuring a comprehensive and representative dataset.

The interview protocol was designed to directly address the study’s central question regarding the transformation of technical adaptations into social spheres. It investigated the process of building on hillsides, the relational dynamics between dwellings, streets, and neighbors, and the perceived adequacy of formal public spaces. A specific line of questioning focused on the quotidian use of neighborhood spaces by different demographic groups, the activities they hosted, and the relationship between planned and spontaneously emerging social areas. Crucially, interviews meticulously examined the interstitial zones like platforms, stairways, and setbacks, probing their dual function: at a domestic level, how they facilitated access, expansion, and habitability; and at a collective level, how they acquired social value as points of encounter, circulation, and coexistence. This systematic approach allowed for the triangulation of spatial data with resident perceptions, directly illuminating the social production of semi-communal space from the ground up. A methodological summary is presented. (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Methodology summary.

3. Results

3.1. Settlement of Hillside Housing

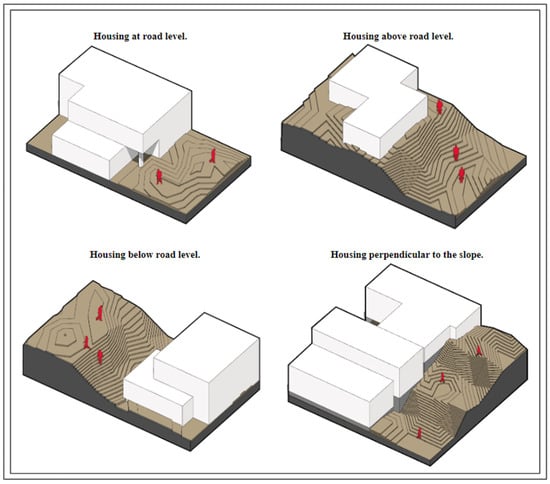

The physical and anthropogenic analyses conducted through non-participatory observation and the structured visual survey identified four types of housing settlement according to the hillside slope, highlighting the specific features that differentiate each form of adaptation to the terrain (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Distribution of settlement types in Los Portales de Mirador.

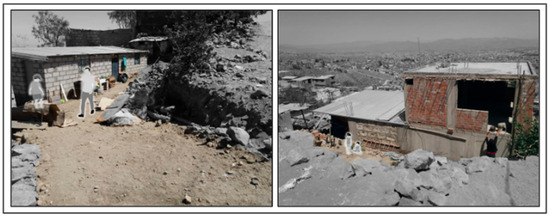

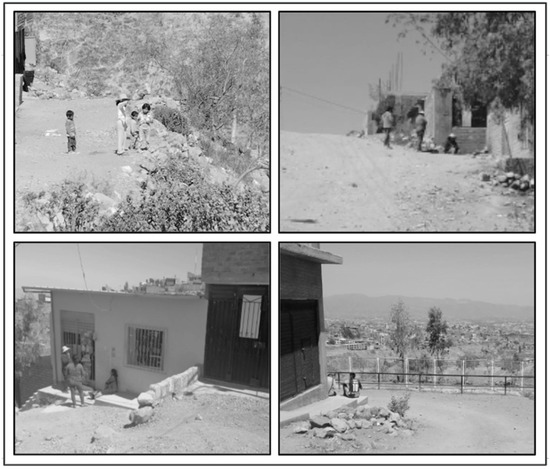

It was observed that residents built their homes according to their own criteria and resources, reflecting both creativity and technical limitations inherent to self-management. Pedestrian circulation is particularly difficult, especially for children and older adults, who suffer from solar radiation and street-level pollution. In this context, improvements in streets or parks were achieved mainly through neighborhood organization and coordination with the community board, while no significant interventions from the municipal government of Alto Selva Alegre were recorded (Figure 5).

This panorama shows that normative public social spaces are practically absent or non-functional, while the streets, far from being meeting places, are perceived as inhospitable and difficult to navigate. This initial condition is key to understanding why, later, semi-communal spaces—although originally conceived with technical purposes—end up acquiring a social role as the most active arenas of neighborhood life (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Streets of the case study of the streets of Los Portales de Mirador.

Figure 7.

Schematic representation of the types of settlement in Los Portales de Mirador.

3.1.1. Housing at Road Level

This type of dwelling is located on land with moderate slopes ranging from 5% to 10%, allowing for an almost direct implantation onto the street plane. These houses are built with both provisional and durable materials, and in some cases reach more than one level. Slight setbacks in building volumes relative to the street alignment generate small front voids that are often used for storing construction materials.

3.1.2. Housing Above Road Level

This type of housing is located above the street level, on slopes between 11% and 30%. Due to limited economic resources to level the ground, most of these houses are built with 50% or more precarious materials, restricting their development to a single level.

The relation to the street is established through a setback of the building volume adapted to the slope. This intermediate space is usually resolved with stepped dry-stone walls functioning as retaining structures. Small porches, stairs, and natural platforms also appear, mediating between the dwelling and the street (Figure 8).

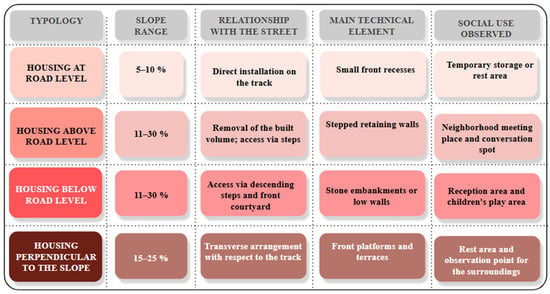

Figure 8.

Summary table of the types of housing observed.

3.1.3. Housing Below Road Level

On slopes ranging from 11% to 30%, houses located below the road level employ stairs and front patios to facilitate access. These elements serve as retaining walls, while also providing light, ventilation, and structural resistance against rain or landslides, and creating a reception space that offers privacy for residents.

3.1.4. Housing Perpendicular to the Slope

These dwellings are positioned perpendicular to both the slope and the roadway. They are built using precarious materials, durable construction materials, or a combination of both. The slope gradients range from 15% to 25%, resulting in one side of the façade being located at a higher elevation than the other. On the horizontal plane, the recessed volume creates a platform that extends toward the public roadway, forming a generous and welcoming entrance space that softens the steep incline. This configuration produces a series of terraces along the slope.

The morphological analysis made it possible to identify four main housing settlement patterns on the hillside. However, beyond their constructive dimension, each pattern defines different relational conditions between the dwelling, the street, and the semi-communal spaces. The slope, type of implantation, and materials used respond not only to technical criteria but also shape the ways in which residents move, interact, and appropriate their immediate surroundings. The following table summarizes the most relevant physical and social characteristics observed in each typology (Figure 8).

3.2. Functions of Physical Elements for Housing Adaptation to the Hillside

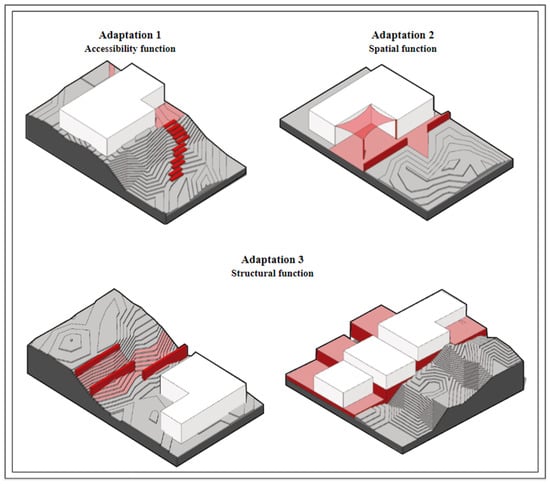

To adapt to the slope, residents developed architectural elements to address geographic challenges. These elements were identified and classified according to their functions in relation to housing (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Schematic representation of adaptation functions in Los Portales de Mirador.

3.2.1. Accessibility Function

This adaptation is resolved through narrow or wide stairways conceived as accessibility elements, allowing residents to move from the street to the dwelling entrance. This provides access even when the dwelling is not aligned with the road. (Figure 9).

3.2.2. Spatial Function

This function appears as a patio or porch at the entrance, serving as a transitional space that places the dwelling on a flatter, more favorable area of the lot. It can be configured by subtracting part of the building volume on the façade or by setting the entire construction back. The front or rear patio is often delimited by a low dry-stone wall, providing porosity and accessibility through its openings. This space is frequently envisioned as a potential extension of the dwelling. (Figure 9).

3.2.3. Structural Function

This element usually consists of stepped platforms or retaining walls that act as structural supports responsible for stabilizing the terrain on which the building stands. (Figure 9).

3.3. Origin of Semi-Communal Spaces: Settlement Forms + Technical Functions of Physical Elements

The way houses are implanted on the hillside and the architectural elements used for slope adaptation give rise to the self-production of semi-communal spaces. Initially conceived as technical supports, platforms, retaining walls, or stairways, they eventually transform into places of socialization and rest (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Double-entry diagram correlating settlement patterns with respect to road level and housing adaptation functions.

At first mere technical solutions, their configuration, proximity, location, and convenience gradually lead to their spontaneous use by homeowners as reception areas, gossip corners, storage zones, or buffer spaces providing privacy. At the same time, these same qualities make them attractive for outsiders, who use them as resting spots, playgrounds, casual meeting points, or waiting areas along the streets.

As Millán et al. [52] argue, these spaces possess intrinsic value, not only because they are organically integrated into the slope but also because they are highly appreciated by residents for the benefits they provide to both housing and community life. In this regard, what occurs in the semi-communal spaces of hillside settlements resembles what Delgado [49] describes for the street: a radical form of social space, which does not exist as a static object but as a site of relations, practices, and gazes in constant movement. Thus, these spaces are not mere technical devices or fixed settings, but living arenas continually updated through everyday use, whether for resting, conversing, playing, or simply passing through. Like the street in urban anthropology, semi-communal spaces are social events, regenerated daily through the appropriation of residents and passersby.

3.3.1. Housing at Road Level

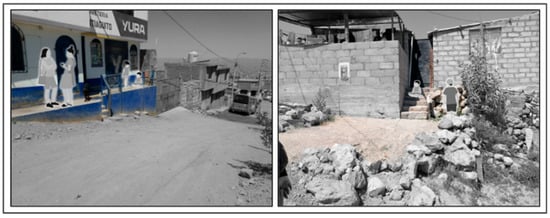

When the building volume is set back from the street alignment, the resulting front yard, usually delimited by a low stone wall, becomes a semi-communal space. Beyond its domestic function, it serves as a node of neighborhood socialization, where passersby find a shaded resting spot within their daily walk. Thus, an architectural resource initially conceived to organize access is transformed into a setting for everyday encounters (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

House at the road level.

3.3.2. Housing Above Road Level

In this adaptation, the dwelling is complemented by stepped stairs and platforms forming an empirical terrace system. These elements, initially designed to resolve the slope technically, acquire unexpected social value: children perceive them as play areas, appropriating them through games. In this way, stairs and platforms are transformed into micro-stages for exploration and recreation, illustrating how hillside adaptations can generate opportunities for neighborhood socialization and learning (Figure 12).

Figure 12.

House above road level.

3.3.3. Housing Below Road Level

In this typology, the dwelling sits below street level, supported by a front patio defined by retaining walls made of blocks and dry stone. The first floor remains partially buried, while the front patio allows for sunlight and natural ventilation. This intermediate space fulfills practical functions but also becomes social: it can serve as a reception area, children’s play space, storage area, or small domestic garden.

At the same time, the proximity of the building to the street allows direct access from the road to the roof of the first floor, functioning as a porch-overlook. This elevated space provides neighborhood views, serves as a resting point, and becomes a privileged site for everyday socialization among residents and passersby. Thus, what began as a technical response to the slope evolves into a multifunctional semi-communal space, articulating the dwelling with street-level social dynamics (Figure 13).

Figure 13.

House below road level.

3.3.4. Housing Perpendicular to the Slope

In this form, dwellings are adapted through platforms placed perpendicularly to the street, allowing access from different terrain levels. When extended from the dwelling entrance, these platforms act as shaded porches mediating between house and street, providing resting areas, receiving guests, or accommodating light domestic activities.

Where the adaptation is resolved with a single platform, access is achieved via stairways perpendicular to the road, creating a pathway that also functions as a site of casual encounters and daily interaction. Thus, a technical adaptation of the terrain becomes a versatile semi-communal space, facilitating both physical connection to the street and the strengthening of neighborhood social ties (Figure 14).

Figure 14.

House perpendicular to the slope.

The results show that the origin of semi-communal spaces does not stem from an initial social intention, but from a technical necessity. Residents, faced with the slope and the lack of institutional support, implement empirical solutions to stabilize the terrain and improve accessibility. This gives rise to retaining walls, platforms, steps, or setbacks, which initially serve structural or access functions.

However, over time, these elements are reconfigured through everyday use. As one neighbor expressed: “At first, we built the steps just to get in, but then the children started playing there, and now we all sit there to talk when the sun goes down.” Another resident noted: “That platform was for placing water buckets, but later we decorated it with flowers because it became a nice spot to watch people pass by.”

These testimonies reveal the transition from technical adaptation to social appropriation. What begins as an empirical response to the physical conditions of the hillside gradually becomes a support for community life. The materiality—stone, concrete, soil—is re-signified by the social practices that inhabit it.

In this process, technique and everyday life intertwine: residents reinterpret the boundaries between home and street, transforming construction margins into spaces of gathering. Thus, semi-communal spaces are the result of a dual production, both physical and symbolic, in which technical creativity enables socialization and neighborhood coexistence.

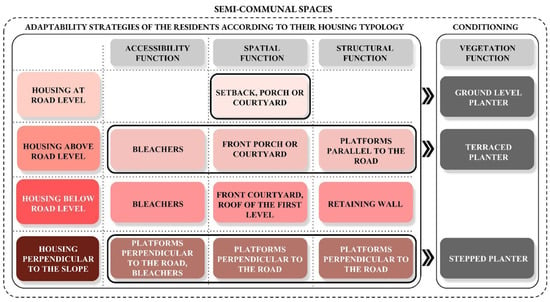

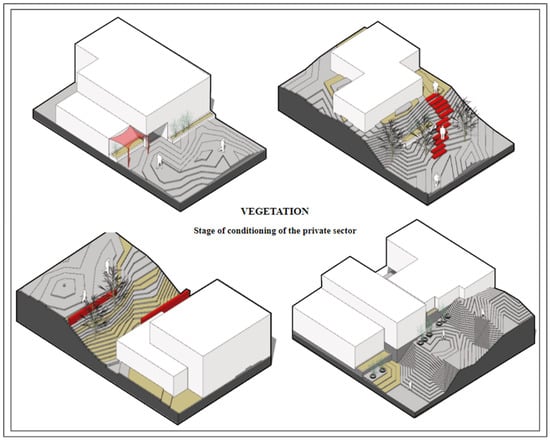

3.4. Conditioning of Semi-Communal Spaces: Evolution Through Vegetation

Over time, semi-communal spaces enter a phase of conditioning, where residents, recognizing their value, embellish and transform them with new meanings. This process is reflected in the introduction of vegetation, potted plants, and small gardens, converting technical areas into vibrant and symbolic spaces. Ground-level vegetation includes trees and shrubs bordered with stones, tires, or recycled materials, while elevated planters with shrubs up to two meters high are installed along façades or platforms. These arrangements provide shade, freshness, and color, enhancing comfort while symbolizing care, pride, and belonging (Figure 15 and Figure 16).

Figure 15.

Double-entry diagram correlating settlement patterns with respect to road level, housing adaptation functions and form of conditioning with vegetation of semi-communal spaces.

Figure 16.

Schematic representation of the vegetation conditioning in semi-communal spaces.

The introduction of vegetation carries broader implications than aesthetic improvement alone. On one hand, these arrangements act as markers of appropriation, demonstrating residents’ commitment to consolidating these spaces as integral to daily life. On the other hand, they contribute to collective well-being, offering pleasant areas for rest, conversation, and play, thereby strengthening neighborhood cohesion. By beautifying these spaces, residents transform what began as a technical resource into a socially valued arena, where both individual aspirations for housing improvement and collective practices of care converge. In this sense, vegetation is not mere ornament but a tangible symbol of urban and community consolidation, reinforcing the settlement’s identity and projecting it as a more livable and dignified environment (Figure 17).

Figure 17.

House and the semi-communal space with vegetation.

The conditioning of semi-communal spaces is mainly evident in the incorporation of vegetation, improvised furniture, and simple construction details. The presence of plants, flowerpots, or small trees does not respond solely to aesthetic criteria, but constitutes a tangible sign of appropriation and collective life. In spaces where residents introduce vegetation, the atmosphere changes: the street becomes more habitable, encounters more frequent, and the space more valued.

This process generates a virtuous socio-environmental cycle. The initial introduction of vegetation, even minimal, transforms the perception of the place, stimulating the desire to stay and share. This increase in social interaction strengthens the sense of belonging, which in turn promotes new care and beautification actions, such as daily watering, adding more flowerpots, or protecting the plants. These practices reinforce neighborhood cohesion and consolidate the semi-communal character of the space, encouraging a continuous cycle of improvement and appropriation.

As some residents recounted: “When we planted the flowers, nobody wanted to litter anymore,” or “Now everyone brings a plant; it has become a kind of tradition.” These expressions reveal how environmental care becomes social care, and how the act of planting translates into a symbolic way of inhabiting and belonging.

From an ecological and psychological perspective, various authors have shown that daily contact with urban vegetation improves subjective well-being, neighborhood identity, and neighborly cooperation [53,54]. In informal contexts, where resources are limited, these micro-actions acquire even greater value: greenery not only beautifies but also activates a positive feedback process between nature, sociability, and community sense.

Thus, vegetation is not merely decoration, but the driver of a cycle that reproduces the social life of the neighborhood. The more greenery appears, the stronger the bond with the place; and the greater the sense of belonging, the more effort is devoted to maintaining it. In this way, the semi-communal space consolidates as a living infrastructure, in permanent collective construction.

3.5. From Constructive Adaptation to the Social Production of Space

Although hillside settlement forms might be understood solely as technical or typological conditions, this study shows they are also significant insofar as they shape and are shaped by neighborhood socialization processes. The disposition of houses relative to the street, whether above, below, at the same level, or perpendicular to the slope, is neither neutral nor autonomous. It acquires meaning as it is appropriated and re-signified by residents through daily practices. (Figure 18).

Figure 18.

Social spaces on the hillside.

The interaction between housing settlement forms and social uses transforms technical solutions into lived semi-communal spaces. Patios, stairs, and porches become playgrounds, resting areas, and meeting points only because residents occupy, maintain, and imbue them with meaning. Thus, the street is understood not merely as a physical product nor solely as a social space, but as the result of continuous feedback between material practices and human activity: between constructive techniques enabling hillside habitation and collective practices that make those interstices genuine spaces of community life.

3.6. Why Normative Spaces Do Not Work but Semi-Communal Ones Do

Some of the residents’ responses to this question were as follows:

- “That sports field looks big, but it is almost never used because it is always full of dirt and nobody takes care of it.”

- “The park is too far away; when my children go there, I cannot supervise them, so I prefer they play near the house.”

- “They built a playground, but never provided shade or benches; the sun is so strong that it cannot be tolerated”.

The comparison between normative and semi-communal spaces clarifies why some remain empty while others consolidate as meeting places. In Los Portales del Mirador, normative public spaces, such as the sports field, playground, and multi-use court—show limited use due to their peripheral location, lack of maintenance, and weak connection with residents’ daily lives.

Far from functioning as meeting points, these places are perceived as alien and exposed to neglect. In contrast, semi-communal spaces operate as genuine social arenas precisely because they are embedded in everyday routines. Closely tied to housing, they are constantly maintained, cleaned, repaired, or decorated by residents, ensuring their durability. Their proximity, immediate accessibility, and visibility from within dwellings turn them into places of rest, play, and conversation that reinforce neighborhood cohesion.

Thus, while normative public spaces fail due to their disconnection from residents’ context and daily life, semi-communal ones thrive as living social spaces, thanks to spontaneous appropriation, continuous care, and integration into neighborhood dynamics.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

4.1. Evolution of Semi-Communal Spaces

The identification of hillside housing settlement patterns is not merely a typological or constructive outcome; rather, it helps explain how each disposition of dwellings in relation to the street generates particular conditions for the emergence of semi-communal spaces. In this sense, adaptation strategies address not only technical challenges of leveling and accessibility but also shape the possibilities for social interaction within the neighborhood.

Initially, technical elements such as retaining walls, platforms, stairs, or patios are conceived exclusively to stabilize the ground and ensure access to the dwelling. Through everyday use, however, these areas are spontaneously appropriated by residents, who transform them into places for resting, play, or occasional encounters. Subsequently, collective recognition occurs, whereby semi-communal spaces begin to be assumed by neighbors as genuine social arenas in the neighborhood. At this stage, a process of conditioning and re-signification unfolds: residents not only maintain these spaces but actively transform them into settings of community life. The introduction of vegetation, improvised furniture, and simple constructive details does not merely embellish the space; it turns it into a symbol of collective care and neighborhood pride. This process grants new social and symbolic value, reinforcing the sense of belonging, projecting neighborhood identity, and consolidating semi-communal spaces as indispensable social infrastructure for daily coexistence.

Finally, the articulation of these semi-communal spaces with the housing adaptations themselves enriches the adjoining streets, offering opportunities for cohesion and new forms of socialization. Thus, what began as an individual technical necessity becomes a collective phenomenon capable of redefining the lived character of the street and reaffirming the capacity of hillside communities to produce the city from below.

4.2. The Symbiosis Between Technique and Social Life in the Production of Space

This analysis builds on the theoretical contributions of Lindón [2], Hernández García [31], and Delgado [30,35], and explicitly frames them within Lefebvre’s [1] concept of the social production of space. Following Lefebvre, space is not merely a physical container but a product of social practices, shaped through the continuous interaction between material conditions and human action. In hillside contexts, these practices are inseparable from technical adaptations: retaining walls, platforms, steps, and other housing modifications provide the necessary support for everyday interactions while responding to the challenges of complex terrain.

Consistent with Lindón, social spaces emerge from daily routines and the meanings residents assign to their surroundings. Hernández García’s emphasis on housing adaptations is complemented here by showing that such interventions extend into semi-communal spaces, blurring the boundaries between private and collective domains. In line with Delgado [55], public and social spaces are produced through relationships and practices, not pre-defined structures. Lefebvre’s framework allows us to interpret these semi-communal spaces as simultaneously technical and social constructions: material supports enable action, and residents’ everyday use re-signifies and socially enlivens these spaces.

Thus, in informal hillside settlements, the production of space is a co-creative process: technical solutions respond to environmental constraints, while social practices transform these interventions into meaningful places. This confirms that material and social dimensions are intertwined, illustrating Lefebvre’s idea that urban space is continuously produced through the dynamic interplay of physical conditions and human agency.

4.3. Between Social Cohesion and Material Vulnerability

The findings should not be interpreted only from a celebratory perspective, since, as Lefebvre [1] reminds us, the production of space is always a political process, where material conditions, everyday practices, and institutional decisions are intertwined. In this regard, semi-communal spaces are both testimonies of community resilience and evidence of the unequal distribution of urban resources and opportunities.

Although they represent manifestations of appropriation and neighborhood cohesion, they also result from unfinished construction processes, often marked by precariousness and the absence of adequate technical planning. Improvised stairs, unreinforced retaining walls, or unprotected platforms can become sources of risk for users, particularly in the context of unstable slopes, seasonal rains, and seismic activity.

Likewise, the comparison with normative public spaces is revealing: while parks or sports courts remain largely unused due to their disconnection from daily life and lack of maintenance, semi-communal spaces thrive precisely because they are linked to housing and cared for by their occupants. For residents, normative spaces appear alien, while semi-communal ones are experienced as their own. This difference explains why the latter sustain everyday interactions, while the former often fall into abandonment.

In this sense, semi-communal spaces are at once arenas of socialization and symptoms of the structural vulnerability of informal settlements. This duality compels reflection on the need to recognize them as urban contributions, while also addressing their limitations and risks, without losing sight of the inequality that underpins their emergence.

Semi-communal spaces, while testifying to community cohesion and creativity, also reveal the structural precariousness and urban inequality characteristic of hillside settlements. In many cases, improvised steps, unreinforced retaining walls, or platforms without railings become risk areas, especially during rainfall or seismic activity. However, these spaces also constitute valuable opportunities to rethink urban intervention strategies from a collaborative perspective.

Rather than replacing or standardizing existing structures, municipalities could recognize and strengthen semi-communal spaces as micro public infrastructures. This would involve integrating neighborhood initiatives into municipal neighborhood improvement programs, combining technical assistance with community participation. Instead of imposing external projects, local authorities could provide technical guidance, basic materials, and training in safe construction, directing neighborhood efforts toward durable, low-cost interventions.

Similarly, institutionalizing participatory maintenance funds would allow communities to continue caring for the spaces they produce, with logistical support and professional supervision. This approach would not only reduce structural risks but also enhance local autonomy, mutual trust, and neighborhood sustainability.

Reframing semi-communal spaces from this perspective implies recognizing them as infrastructures of cohesion, where technical and social dimensions complement rather than oppose each other. Residents’ experiences show that improving the environment does not require large investments but strategies that value self management and collaboration. By acting as facilitators rather than executors, municipalities can transform material vulnerability into an opportunity to redefine community space, promoting inclusive, gradual, and socially vibrant urbanization.

From a broader perspective, the theoretical and methodological framework developed here, which combines morphological analysis, ethnographic observation, and the study of the social production of space, offers an approach applicable to other informal hillside settlements in Latin America. Its value lies in showing how extreme physical conditions, far from being an obstacle, can act as catalysts for social organization, constructive creativity, and the collective production of urban space.

At the political and urban planning level, the results call for recognizing semi-communal spaces within participatory planning instruments, particularly in neighborhood improvement and urban regeneration programs. Incorporating these spaces into municipal management would not only address their structural vulnerability but also leverage their potential as platforms for social cohesion and grassroots civic engagement.

In this sense, recognizing semi-communal spaces as urban assets constitutes an opportunity to rethink the city from its most everyday, self-managed, and resilient forms.

4.4. Transitory Phenomenon or Consolidated Social Infrastructure?

It is crucial to note that geophysical and anthropic conditions have shaped the self-production of both housing and social spaces, reflecting the community dynamics of the settlement. However, the future of semi-communal spaces remains uncertain. Their permanence and transformation depend not only on housing evolution and processes of urban consolidation, but also, decisively, on anthropic perspectives, that is, on how residents value, use, and maintain these spaces in everyday life.

This uncertainty calls for extending research to other self-produced peripheral neighborhoods, both in similar and different contexts, to assess whether the processes identified correspond to a generalized dynamic in hillside settlements or acquire specific forms according to each territory. A comparative approach would allow for evaluating not only the trajectory of semi-communal spaces but also their potential role in the future of the city.

In this sense, an important line of reflection emerges for urban planning: recognizing semi-communal spaces as urban assets that, beyond their technical and empirical origins, contribute to social cohesion and neighborhood identity. Incorporating this dimension into public policies and urban plans could mark the difference between relegating them as marginal phenomena or leveraging them as opportunities to rethink the city from its most everyday and community-based forms.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.S.C.-C. and P.S.M.-C.; methodology, R.S.C.-C., P.S.M.-C. and E.G.M.-H.; formal analysis, R.S.C.-C., P.S.M.-C., E.G.M.-H. and E.A.-S.; investigation, R.S.C.-C. and P.S.M.-C.; data curation, R.S.C.-C., P.S.M.-C., E.G.M.-H. and E.A.-S.; writing—original draft preparation, R.S.C.-C., P.S.M.-C., E.G.M.-H. and E.A.-S.; R.S.C.-C. and P.S.M.-C.; supervision, E.G.M.-H. and E.A.-S.; project administration, E.G.M.-H. and E.A.-S.; funding acquisition, R.S.C.-C. and P.S.M.-C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Universidad Nacional de San Agustín de Arequipa covered by Project “CONJUNTO INTEGRAL HABITACIONAL DE RENOVACIÓN BARRIAL EN LADERA: RECUALIFICACIÓN URBANA DEL ASENTAMIENTO HUMANO “TRES BALCONES DEL MIRADOR” DE SELVA ALEGRE, AREQUIPA”, contract PTTMD-022-2023-UNSA.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical review and approval were not required under Peruvian national regulations, as the research involved only voluntary interviews about everyday experiences, without the collection of sensitive personal data or biological information. According to the Código de Ética en Investigación Científica (CONCYTEC, Chapter II Section 2.3.2) [56], this type of social research does not require Institutional Ethics Committee approval.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Participation was voluntary and anonymous, with no collection of sensitive personal data or information that could directly identify participants.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Additional questions can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the interviewees for their support and availability during the interviews. Special thanks are due to the National University of San Agustín of Arequipa for its financial support of this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviation

The following abbreviation is used in this manuscript:

| INDECI | National Institute of Civil Defense (Instituto Nacional de Defensa Civil) |

References

- Lefebvre, H. La Production de L’Espace; Anthropos: Paris, France, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Lindón, A. The socio-spatial construction of the city: The subject body and the subject feeling. Rev. Larinoamericana Estud. Sobre Cuerpos Emoc. Soc. 2009, 1, 6–20. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/2732/273220612009.pdf (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Clichevsky, N. Algunas reflexiones sobre informalidad y regularización del suelo urbano. Rev. Bitácora Urbano Territ. 2009, 14, 63–88. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/748/74811914005.pdf (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Velarde, H. Public space in the popular city: Life between hillsides. Bull. L’institut Français D’études Andin. 2017, 46, 471–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, J. Espacio público y prácticas sociales en barrios populares de Bogotá. Rev. INVI 2013, 28, 143–178. Available online: https://revistainvi.uchile.cl/index.php/INVI/article/view/62459 (accessed on 13 November 2025). [CrossRef]

- Abramo, P. La ciudad confusa: Mercado y producción de la estructura urbana en las grandes metrópolis latinoamericanas. EURE 2012, 38, 35–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, S. La producción informal de espacios públicos en asentamientos humanos de Piura (Perú). Ciudades 2024, 27, 113–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peresini, N. Las agendas internacionales y el desarrollo urbano local. Una revisión por los modelos de planificación e instrumentos adoptados por la gestión urbana local en Córdoba, Argentina (1983–2019). Rev. Geogr. Norte Gd. 2020, 77, 71–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segura, R. Vivir Afuera. Antropología de la Experiencia Urbana; UNSAM EDITA: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Uribe, H.; Ayala Osorio, G.; Holguín, C.J. Ciudad Desbordada. Asentamientos Informales en Santiago de Cali, Colombia; Universidad Autónoma de Occidente: Cali, Colombia, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, A.B.; Hernández, A. Análisis de la situación actual de la regularización urbana en América Latina: El tema de la seguridad de la tenencia del suelo en tres realidades distintas: Brasil, Colombia y Perú. Rev. INVI 2010, 25, 121–152. Available online: https://www.scielo.cl/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0718-83582010000100005&lng=es&nrm=iso (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Segura, R. La trama relacional de la periferia urbana en la ciudad de La Plata. La figuración establecidos-outsiders revisitada. In Proceedings of the VI Jornadas de Sociología de la UNLP, La Plata, Argentina, 9–10 December 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Rojas, H. La autoproducción del hábitat de un barrio informal en un contexto de ilegalidad y conflicto. Cuad. Vivienda Urban. 2022, 15, 2–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderón, J. Los barrios marginales de Lima 1961–2001. Ciudad. Territ. Estud. Territ. 2003, 35, 375–389. Available online: https://recyt.fecyt.es/index.php/CyTET/article/view/75397 (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Lindón, A.; Hiernaux, D. Los Giros de la Geografía Humana: Desafíos y Horizontes; Anthropos–Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana Iztapalapa: Barcelona, España, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdin, A. La Métropole des Individus; Éditions de l’Aube: Paris, France, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Salas, J.; Salazar, G.; Peña, M. Una propuesta esquemática para el análisis de la autoconstrucción en Latinoamérica como fenómeno masivo y plural. Inf. Construcción 1988, 40, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Riofrio, G. Producir la Ciudad (Popular) de los ‘90: Entre el Mercado y el Estado; Instituto de Estudios Peruanos: Lima, Peru, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Robert, J.; Sierra, A. Mejoramiento físico e integración social en Río de Janeiro: El caso Favela Bairro. Bull. L’institut Français D’études Andin. 2009, 38, 595–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiori, J.; Riley, E.; Ramírez, R. Mejoramiento físico e integración social en Río de Janeiro: El caso Favela Barrio. Cuad. Urbano 2002, 3, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziccardi, A. Pobreza y exclusion social en las ciudades del siglo XXI. In Procesos de Urbanizacion de la Pobreza y Nuevas Formas de Exclusión Social: Los Retos de las Políticas Sociales de las Ciudades Latinoamericanas del Siglo XXI; Colección CLASCO-CROP; CLASCO: Bogotá, Colombia, 2008; Available online: https://biblioteca.clacso.edu.ar/clacso/clacso-crop/20120621115414/02zicca2.pdf (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Moreno, C. ¿A lado del camino? Inventando estrategias de autogestion del habitat en Chile. Rev. INVI 2021, 36, 279–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sáez, E.; Garcia, J.; Roch, F. La ciudad desde la casa: Ciudades espontáneas en Lima. Rev. INVI 2010, 25, 77–116. Available online: https://revistainvi.uchile.cl/index.php/INVI/article/view/62326/65990 (accessed on 13 November 2025). [CrossRef]

- Castro, B.; Perdomo, B. La autoconstrucción en la ciudad de Lima: Hábito poblacional que configura el entorno urbano. Rev. Fac. Arquit. Univ. Autónoma Nuevo León 2024, 18, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, R.; Zúñiga, V. La vivienda informal como estrategia de resistencia cotidiana. El caso de la población Las Canteras, comuna de Huechuraba. Rev. Derecho Pontif. Univ. Catól. Valpso. 2022, 22, 55–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, J.; López, C. El urbanismo de Ladera: Un reto ambiental, tecnologico y del ordenamiento territorial. Rev. Bitácora Urbano Territ. 2004, 1, 94–102. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/748/74800814.pdf (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Zanelli, C.; Santa, S.; Valderrama, N.; Daudon, D. Assessment of Vulnerability Curves of Pircas over Slopes by the Discrete Element Method (DEM)—A Case Study in Carabayllo, Peru. In Proceedings of the Geotechnical Earthquake Engineering and Soil Dynamics, Austin, TX, USA, 10–13 June 2018; pp. 66–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egea, C.; Salamanca, L.; Egea, B. El concepto de “espacio público” en América Latina desde el campo bibliográfico. Cuad. Vivienda Urban. 2021, 14, 1–25. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/journal/6297/629774664014/html/ (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Takano, G.; Tokeshi, J. Espacio Público en la Ciudad Popular: Reflexiones y Experiencias Desde el sur; DESCO: Lima, Peru, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado, M. El Espacio Público Como Ideología; Los libros de la Catarata: Madrid, Spain, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández, M. Procesos Informales del Espacio Publico en el Habitat Popular. Rev. Bitácora Urbano Territ. 2008, 13, 109–116. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=74811925008 (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Giannini, H. La Reflexión Cotidiana: Hacia Una Arqueología de la Experiencia; Editorial Universitaria: Santiago, Chile, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Solà-Morale, I. Terrain Vague; Gustavo Guili: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Hertzberger, H. Lessons for Students in Architecture; 010 Publishers: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado, M. El Animal Público; Anagrama: Barcelona, Spain, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Meza, C.; Nizama, M.; Armas, C.; Peña, A.; Arias, M.; Paucar, M.; Palacios, E.; Manrrique, C.; Nizama, M. Informalidad en la construcción de unidades inmobiliarias en zonas vulnerables de los Asentamientos Humanos Nicolás de Piérola y Los Cañaverales (Chosica, Lima); Ratio Legis: Salamanca, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Cieza, R.; Ortiz, D. Conjunto de viviendas y espacio público en San Gabriel Alto. Estrategias proyectuales para urbanizar la ladera. Limaq 2017, 3, 161–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Municipalidad Distrital De San Juan De Miraflores. Informe de Evaluacion del Riesgo por Movimientos en Masa del Asentamiento Humano Asociacion Vecinal la Planicie; Municipalidad Distrital De San Juan De Miraflores: Lima, Peru, 2020.

- Torres, C. Valoración Del Riesgo En Deslizamientos. Licentiate Thesis, Universidad Ricardo Palma—URP, Lima, Peru, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Zavala, C. Guía Técnica para Reducir el Riesgo de Viviendas en Laderas; PREDES.: Lima, Perú, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- INDECI. Manual de Estimacion de Riesgos Ante Movimientos de Masa en Laderas; Cuaderno Tecnico N°3; INDECI: Lima, Peru, 2011.

- INDECI. Guia Constructiva de Recomendaciones Estructurales; Cuaderno Tecnico N°6; INDECI: Lima, Peru, 2011.

- Universidad Nacional de Ingeniería Facultad de Ingeniería Civil; Centro Peruano Japonés de Investigaciones Sísmicas y Mitigación de Desastres. Estudios de Microzonificación Geotécnica Sísmica y Evaluación del Riesgo en Zonas Ubicadas en Los Distritos de Carabayllo y el Agustino (Provincia y Departamento de Lima); Distrito del Cusco (Provincia y Departamento del CUSCO); y Distrito de alto Selva Alegre (Provincia y Departamento de Arequipa); Universidad Nacional de Ingeniería Facultad de Ingeniería Civil; Centro Peruano Japonés de Investigaciones Sísmicas y Miti-gación de Desastres: Lima, Peru, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- INGEMMET. Evaluación de Peligros Geológicos en el Distrito de Alto Selva Alegre; Instituto Geológico, Minero y Metalúrgico—INGEMMET: Arequipa, Peru, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lozano, M. Gestion de Viviendas Autoconstruidas en Asentamientos Humanos en Lima. Master’s Thesis, Universidad Politecnica de Madrid, Madrid, Spain, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- López, J. Definicion Geometrica y Recostruccion virtual de la Almazara Puente de Tablas. Doctoral Thesis, Universidad de Cordoba, Cordoba, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández, R.; Fernández, C.; Baptista, P. Metodología de la Investigación, 6th ed.; McGraw-Hill: Mexico City, Mexico, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sainz, J. El Plan Estrategico en la Practical; ESIC: Madrid, Spain, 2003.

- Schwartz, M.; Jacobs, J. Qualitative Sociology: A Method to the Madness; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Kvale, S. InterViews: An Introduction to Qualitative Research Interviewing; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Mertens, D. Research and Evaluation in Education and Psychology: Integrating Diversity with Quantitative, Qualitative, and Mixed Methods, 3rd ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Millán, K.; Bedoya, L.; Quintero, K.; Garcia, V. La apropiacion especial en los habitants del asentamiento informal Nueva Jerusalen en el Municipio de Bello Antioquia, Colombia. Rev. Tem. Cient. 2023, 3, 55–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R.; Kaplan, S. The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Kuo, F. The role of arboriculture in a healthy social ecology. J. Arboric. 2003, 29, 148–155. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado, M. Sociedades Movedizas: Pasos Hacia una Antropología de las Calles; Editorial Anagrama: Barcelona, Spain, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Publicación: Código Nacional de Integridad Científica. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12390/3691 (accessed on 13 November 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).