Abstract

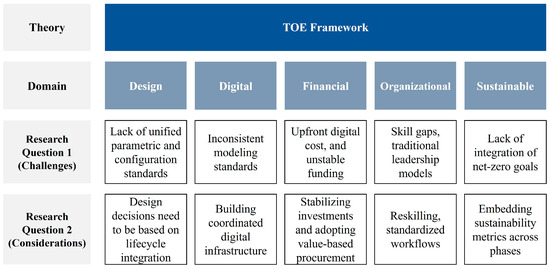

The persistent fragmentation of the architecture, engineering, and construction (AEC) industry drives the pursuit of advanced and unified construction solutions. This study investigated the limited understanding and adoption of one of these solutions, the platform approach to design for manufacturing and assembly (P-DfMA) within the AEC industry. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 14 design professionals from China and the UK to understand how they utilize this approach. Governmental policy documents were also analyzed to examine how they hinder or facilitate the adoption of P-DfMA. The results were mapped using the technology–organization–environment (TOE) framework. Challenges and adoption considerations were identified by a thematic analysis, supported by text-mining results from Voyant Tools, with the most frequent keywords visualized in charts. The findings indicate that P-DfMA adoption is conceptually fragmented within the AEC industry, with a gap between theory and practice. Technical limitations in organizational structuring and environmental misalignment hinder adoption. Challenges and considerations span five domains: design, digital, financial and procurement, organizational, and sustainability. This research offers novel insights gained by integrating multi-layered analyses of construction practice interviews and policy perspectives within the TOE framework, along with timely insights into the socio-technical dynamics shaping the future of the industry.

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

The architecture, engineering, and construction (AEC) industry faces systemic fragmentation that contributes to inefficiencies in project delivery [1]. Persistent barriers include limited collaboration across disciplines [2] and inconsistent digital integration [3,4]. Industrialized construction approaches—particularly the platform approach to design for manufacturing and assembly (P-DfMA)—are attracting increasing attention to address these challenges [5,6]. Borrowing concepts from the automotive and consumer goods industries [7,8], P-DfMA involves the systematic delivery of scalable, repeatable design processes that enhance efficiency using standardization, customization, and cross-project learning [9]. This approach, which emphasizes the use of early collaboration and digital tools such as building information modeling (BIM), is a departure from traditional bespoke workflows in building design and construction [10].

However, despite its potential, P-DfMA implementation remains largely experimental, often confined to pilot projects and limited organizational initiatives [11,12]. Its adoption has been fragmented and inconsistent across firms, regions, and disciplines [13,14]. A better understanding of how P-DfMA is interpreted and applied in practice is necessary, particularly from the perspectives of design professionals [15] and governmental policies [5].

1.2. TOE Framework

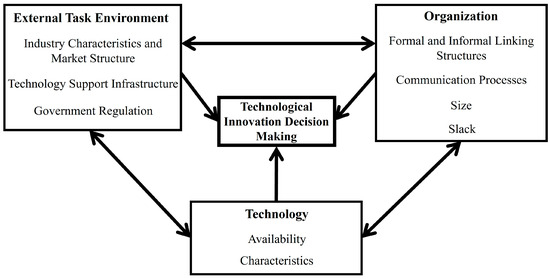

This study applied the technology–organization–environment (TOE) framework to analyze stakeholder experiences and policy documents, linking theoretical constructs to practical innovation adoption in the AEC industry. The TOE framework explains how a firm’s technological, organizational, and environmental contexts shape innovation adoption decisions [16]. Figure 1 illustrates the dimensions of the TOE framework and their components. In a technological context, factors such as the characteristics and availability of digital tools, system standardization, and compatibility with existing workflows influence how design professionals engage with P-DfMA [16,17]. Organizational factors including firm size, intra-firm communication, and collaborative structures mediate how teams negotiate trade-offs between standardization and creative autonomy [18]. Environmental factors such as the market structure and external pressures further shape adoption outcomes by enabling or constraining the implementation of innovation [16].

Figure 1.

Technology–organization–environment framework [16].

These dimensions interact dynamically. For example, strong organizational collaboration mitigates external pressures for cost efficiency, enabling greater creative engagement with technology [18]. By mapping these dimensions, the TOE framework provides an explanatory lens for understanding why adoption outcomes vary across firms, projects, and digital environments [17], as well as how design professionals navigate challenges and considerations in P-DfMA adoption [18,19].

1.3. Gaps in Previous Research

Architects often perceive P-DfMA’s standardized frameworks as limiting their creativity, which traditionally emphasizes uniqueness and site-specific solutions [20,21,22]. From an innovation perspective, this tension reflects the clash between efficiency-driven standardization and creativity-driven exploration. The TOE framework helps explain how firms can manage them by balancing these two logics through dimensions. Acceptance or resistance to P-DfMA varies with the context, such as firm culture and project types [23,24].

Implementing P-DfMA requires early-stage decisions that establish standardized frameworks, thereby shaping downstream design possibilities [25]. This contrasts with architects’ traditional focus on form and spatial organization [26]. In P-DfMA, the shift toward system selection and manufacturability [27] marginalizes architectural roles and reduces design diversity. Nonetheless, such outcomes depend on the project scale, organizational culture, and the use of digital tools, which represent the TOE framework’s dimensions. Under supportive conditions, these factors enable horizontal, collaborative engagement across disciplines [28,29].

Digital tools increasingly empower design professionals to engage with P-DfMA by supporting creativity within complex component systems and aligning designs with manufacturing constraints [28]. BIM facilitates early coordination and integrates performance data to ensure technical quality throughout the design process [29]. These technological and procedural shifts suggest that the outcomes of P-DfMA on creativity, collaboration, and professional identity depend on a set of interacting conditions, including digital competency, organizational culture, early engagement, and system flexibility [30,31,32].

The literature frames P-DfMA as a transformative approach in the AEC industry, positioning designers as co-creators of configurable systems [33]. However, several explanatory mechanisms remain underexplored. First, the dominance of engineering and manufacturing perspectives [32,34] often leaves architects feeling marginalized in platform-based design. Second, limited attention to technology engagement overlooks how digital tools either enable or constrain creative contributions in practice [23]. Third, unresolved tensions between standardization and creativity account for the divergent ways designers interpret P-DfMA, as either a driver of innovation or a threat to professional identity [27]. Identifying these mechanisms provides a theoretical basis for understanding why P-DfMA adoption produces different outcomes across contexts, professions, and projects.

Despite growing interest in P-DfMA practices, recent studies [34,35,36,37,38,39] emphasize technological innovation and production efficiency while devoting limited attention to the organizational and policy conditions that enable P-DfMA adoption across different project and firm contexts [5,36]. Furthermore, few studies [35,38] have analyzed practitioner perspectives or policy-level evidence to explain how contextual factors shape P-DfMA adoption decisions. These gaps underscore the need for research that connects micro-level design practices to macro-level policy frameworks, revealing the technological, organizational, and environmental conditions that influence P-DfMA adoption in the AEC industry.

It is necessary to address these gaps to advance the industry’s theoretical understanding and practical implementation of P-DfMA. A clear picture of how design professionals interpret and adapt P-DfMA principles would inform policy directions and organizational strategies that support innovation. Therefore, this study sought to bridge the divide between theory and practice by integrating practitioner insights and policy analysis within a unified TOE framework.

1.4. Research Approach

This study aimed to examine how design professionals engage with and adapt P-DfMA practices across different organizational and policy contexts. By combining practitioner interviews and policy document analysis, this study aimed to identify the technological, organizational, and environmental dimensions that shape P-DfMA adoption in the AEC industry and provide actionable insights on how to integrate platform thinking into AEC design processes. To guide this investigation, the following research questions were developed:

- What are the challenges faced in adopting P-DfMA in the AEC industry?

- What considerations should design professionals keep in mind to adapt P-DfMA successfully in the AEC industry?

This study employed a mixed-methods approach, combining qualitative data collection from semi-structured interviews with quantitative data collection from policy documents, to identify challenges to and opportunities for P-DfMA adoption and map them to the technological, organizational, and environmental dimensions of the TOE framework. These methods enabled an exploration of how practitioners understand P-DfMA and move beyond abstract models to apply P-DfMA in real-world design contexts. Although P-DfMA is gaining attention in the AEC industry due to its potential to promote standardization and efficiency, practice-based insights are lacking integration with policy analysis from the perspectives of design professionals. This study addressed this gap in the literature by seeking insights into how architects, design managers, BIM coordinators, and technical consultants interpret and adapt P-DfMA in practice. Furthermore, it sought to analyze policy documents to understand the conditions that influence P-DfMA adoption in the AEC industry.

While previous studies [5,21,35] on P-DfMA have predominantly focused on technological or project-level implementation, how organizational and environmental contexts shape its adoption has received limited attention [36,37]. To address this gap, this study linked practice-based insights with policy-level considerations within a unified analytical structure.

Theoretically, this study extends the TOE framework by demonstrating how the technological, organizational, and environmental dimensions interact in practice during P-DfMA adoption and how design professionals address related challenges and considerations. Practically, it highlights how policies and collaborative workflows align to support professionals’ roles and improve implementation. Given that the AEC industry increasingly seeks digital, organizational, and environmental integration to enhance productivity, it is essential to understand how policies and professional practices can evolve to enable successful P-DfMA adoption.

In this article, the term ‘P-DfMA’ refers to the application of platform principles, such as modularity, standard interfaces, and configurable components, within the AEC industry. The term ‘platform approach’ describes the strategic integration of these principles at an organizational or project-delivery level, where design, production, and supply chains are aligned through shared digital and physical assets. The term ‘platform thinking’ refers to the mindset and conceptual logic that underpin such integration, emphasizing reusability, scalability, and cross-project learning. ‘Industrialized construction’ refers to the broader industrial context in which P-DfMA and platform approaches operate, encompassing off-site manufacturing, digital fabrication, and process automation. Thus, P-DfMA is a subset or operational mechanism within the wider shift toward industrialized construction.

Following this introduction, Section 2 outlines the research methodology, before Section 3 presents the interview results. Section 4 presents the policy document analysis results, after which Section 5 provides a cross-analysis of the interviews and policy documents. Section 6 discusses the results, and finally Section 7 concludes with an assessment of the study’s implications.

2. Materials and Methods

A qualitative multi-method approach combining semi-structured interviews with policy document analysis was adopted to address the research questions. This approach enabled triangulation of data sources to capture practitioner perspectives and institutional policy directives regarding the adoption of P-DfMA in the AEC industry. This section describes the materials and methods employed in the data collection and analysis.

2.1. Data Collection

The influence of P-DfMA adoption on design stakeholders’ practices was investigated using two approaches. First, qualitative semi-structured interviews were conducted to capture participants’ experiences, enabling case-specific insights [39,40] and revealing perspectives that extend beyond what is typically addressed in the literature [41].

Fourteen design professionals participated in the study, including architects, design managers, BIM coordinators, and technical consultants. This diverse sampling was intended to reflect various perspectives on collaboration, technology, and workflow adaptation within P-DfMA environments, as shown in Table 1. Participants were drawn from China and the UK to examine the contrasting industrial landscapes of these two countries. China is characterized by a government-led push toward industrialized construction [42], while the UK is recognized as a pioneer in platform-based approaches [34].

Table 1.

Profile of interview participants.

Interviews were discontinued upon reaching thematic saturation, defined as the point at which no novel codes or themes were identified [43]. Saturation was observed after approximately 14 interviews, with subsequent interviews largely confirming the previously identified themes. This stopping criterion ensured that the data adequately captured the range of challenges and considerations relevant to P-DfMA adoption in the AEC industry.

The sampling strategy employed ensured the inclusion of professionals directly involved in design decision-making on P-DfMA construction projects. The selection criteria emphasized diversity in organizational roles (architects, managers, coordinators, and consultants) and firm types (architecture/design firms, engineering consultants, and factories). This process ensured that the data represented multiple organizational perspectives relevant to P-DfMA integration.

The sample size determination followed recommended guidelines [42,43]. All participants had a minimum of three years of AEC experience and direct involvement in modular and P-DfMA-related projects. Practitioners without platform-based design experience were excluded to ensure data relevance and depth of insight.

Open-ended interview questions were asked to facilitate flexible yet focused conversations that enabled deeper exploration of design professionals’ experiences with P-DfMA [44]. The open-ended format supported a comprehensive investigation of how P-DfMA influences practitioners’ perceptions, workflows, and decision-making [45,46]. The interview protocol was designed to encourage reflection on both the conceptual understanding and practical implementation of P-DfMA [41]. The guiding questions included the following:

- Based on your AEC experience, how do you define P-DfMA?

- What does P-DfMA mean to you in practice?

- How does it differ from traditional methods?

- What are the main challenges you faced while implementing P-DfMA?

- What types of challenges impacted your work most?

- What concerns did others on the project raise?

- What considerations are crucial for adapting P-DfMA?

- What lessons should others know?

- Are there specific skills or roles that have made a difference?

The interviews were conducted remotely using Zoom (Version 5.17.0, Zoom Video Communications Inc., San Jose, CA, USA) and Tencent (Version 3.27.0, Tencent Holdings Ltd., Shenzhen, China) platforms between September 2024 and May 2025. The sessions lasted approximately 35 min on average. All interviews followed a consistent semi-structured guide and were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim, and returned to participants for validation to ensure data credibility.

The quantitative analysis of policy documents examined governmental reports, strategy papers, consultation documents, and technical guidelines published since 2013, as shown in Table S1 in the Supplementary Materials. These documents provide institutional perspectives that complement the practitioner viewpoints captured in the interviews. The policy document analysis focused on the UK context due to the absence of P-DfMA policy documents in other contexts [35].

The criterion-based sampling strategy for the documents was based on (1) direct reference to P-DfMA approaches in the AEC industry, (2) publication by official government departments or affiliated agencies, and (3) the provision of either strategic vision or practical implementation guidelines. Targeted searches were conducted on official government portals and repositories of professional organizations, and documents that did not meet these criteria were excluded. This sampling strategy ensured that only policy documents influencing industry-level decision-making were included.

2.2. Data Analysis

Thematic analysis was employed to identify explicit and implicit patterns in the interview data and policy documents, guided by the research questions and informed by gaps identified in the literature [44,47]. The analysis followed the six-phase framework [45], which provides structured guidance for generating and refining themes [43]. This framework includes familiarization with the data and documents, generation of initial codes, grouping of codes into preliminary themes, review and refinement of themes, definition and naming of themes, and writing the final analysis.

To complement the thematic findings and enhance analytical transparency, this study incorporated digital text-mining techniques using Voyant Tools (Version 2.6.19, Stéfan Sinclair and Geoffrey Rockwell, Montreal, QC, Canada), an open-source platform that facilitates the validation of results, triangulation, and mitigation of interpretive bias. The tool was used to analyze large textual datasets, identifying term frequency patterns [46,47] and highlighting variations in terminology based on stakeholder roles or themes [47,48]. The objectives were to identify frequently co-occurring terms and verify the consistency of themes emphasized in the interviews and policy documents. The interview transcripts were compiled into a single document, and the thematic analysis of the policy documents was summarized in another. Both were uploaded to Voyant Tools for text mining analysis, including keyword frequency and collocation examination. The most frequently repeated keywords were then extracted and visually represented through charts created in Microsoft Word (Microsoft Office Professional Plus 2021, Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). This quantitative analysis corroborated the qualitative findings and reduced the risk of researcher interpretation bias.

The TOE framework [16] was selected because it provides a robust analytical structure for examining the contextual factors influencing organizational innovation adoption. The criteria-based justification is based on (1) conceptual comprehensiveness, capturing the multi-level interactions among technological capabilities, organizational readiness, and environmental pressures that collectively shape innovation diffusion; (2) contextual relevance, as the framework aligns with the P-DfMA concept, which operates across digital technologies, organizational processes, and external conditions such as regulations; and (3) empirical precedent, as it has been applied successfully to similar innovation adoption studies in manufacturing and digital construction [17,18]. Thus, the TOE framework offers both theoretical grounding and practical relevance for structuring the analysis of P-DfMA adoption in the AEC industry.

To establish a systematic link between empirical findings and the TOE framework, each theme emerging from the interviews and policy analysis was categorized according to its dominant contextual dimension: technological, organizational, or environmental [16]. The technology dimension encompasses themes related to digital interoperability, standardization tools, and automation barriers, the organizational dimension relates to leadership readiness, inter-departmental collaboration, and resource allocation, and the environmental dimension concerns policy support, client demand, and supply chain maturity [16]. This mapping process was conducted manually through thematic analysis, following the identification of key themes from the interviews and policy document analysis. Each theme was reviewed and categorized according to its dominant contextual relevance within the TOE framework. This mapping followed a theory-driven thematic logic [46,47] in which the TOE framework served as an analytical lens for organizing and interpreting the data. Cross-checking between interview and policy results ensured consistency and reinforced the analytical validity of the categorization.

Several procedures embedded in the qualitative design reinforced methodological reliability and validity. Triangulation was achieved by comparing and integrating data from the interviews and policy document analysis, thereby minimizing single-perspective bias. The researchers also maintained a detailed coding protocol documenting how themes were derived from the data, ensuring transparency and consistency throughout the manual thematic analysis process. Peer debriefing with two academic colleagues familiar with P-DfMA research functioned as an informal inter-coder check, reviewing the coding structure and thematic interpretation.

Reflexivity was maintained via a research diary in which decisions and interpretations were recorded and reviewed continuously to mitigate subjective bias. In addition, participants were provided with summary findings to review, ensuring that the researchers’ interpretations accurately reflected their professional perspectives.

To further strengthen the methodological rigor of this study, particular attention was devoted to ensuring qualitative trustworthiness in terms of credibility, dependability, and confirmability. Credibility was reinforced through the triangulation of data sources and the validation of interpretations by participants, ensuring that the findings authentically represented diverse professional perspectives. Dependability was achieved through the systematic application of a transparent coding protocol and maintaining an explicit audit trail, which facilitated consistency and replicability in the analytical process. Confirmability was established through reflexive documentation and peer debriefing, minimizing potential researcher bias and ensuring that interpretations remained grounded in the empirical evidence. Thus, these procedures complemented the study’s triangulation and reflexivity strategies, enhancing methodological rigor and reinforcing the overall reliability of the research outcomes.

Combining thematic analysis with text-mining analysis and applying the TOE framework to the interviews and policy documents deepened the insights obtained, enhanced the rigor of the analyses, and produced a novel multi-layered understanding of stakeholder perspectives and policy documents concerning P-DfMA adoption.

3. Interview Results

The challenges and considerations related to each of the domain factors influencing the adoption of P-DfMA in the AEC industry were identified and examined within the context of the TOE framework. The results indicate that platform is an evolving practice marked by digital integration, implementation complexity, and redefinition of design workflows in the AEC industry.

3.1. P-DfMA Definition

Interviewees described P-DfMA as a strategic approach that centralizes core assets, such as shared design logic and component libraries, while decentralizing innovation by allowing flexibility within standardized frameworks. This approach enables the use of repeatable kit-of-parts systems to enhance efficiency and consistency. P-DfMA is a system-oriented design methodology that supports scalable collaboration and coordinated delivery, as Interviewee I1 explained:

“P-DfMA as a foundational approach centralizes expertise and decentralizes innovation; it simplifies the complexity based on what it enables and manages.”

The results of the interviews indicate that architects predominantly described P-DfMA as a design-led approach that structures early-stage decisions and repeatable solutions. Interviewees—particularly those in technical or managerial roles—characterized P-DfMA as a digital service model that supports agile development, supplier collaboration, and the embedding of project-specific knowledge to manage uncertainty in outcomes. This framing reflects a more operational and process-driven interpretation of P-DfMA, emphasizing its potential to structure stakeholder interactions and define service roles throughout the project lifecycle. Interviewee I11 noted:

“… P-DfMA as a service defines the stakeholders, roles, and functions for the project delivery.”

In contrast to traditional bespoke workflows, in which each building is designed as a one-off, context-specific solution, P-DfMA promotes cross-project thinking by reusing design logic, components, and data assets. P-DfMA treats projects as part of a broader product ecosystem, allowing for increased scalability and continuity. This shift fundamentally alters professional roles and responsibilities, such as architects operating within constraint-driven, configurable systems rather than starting from scratch, and design managers focusing on governance rules that guide system implementation. BIM coordinators oversee parametric logic to ensure consistency across components. Technical consultants work through predefined standards and interfaces to integrate specialized systems. These role-based changes reflect a broader redefinition of how projects are conceived and delivered, as Interviewee I2 noted:

“Platform-based work emphasizes validated solution catalogs and configurable typologies, collaboratively chosen for different projects.”

3.2. Design Factors

3.2.1. Design Challenges

The interviews revealed that design challenges in P-DfMA are rooted in balancing standardization with flexibility. P-DfMA requires parametric modeling and integration with manufacturing processes, and many designers lack the expertise and tools to handle this complexity. Additionally, the absence of unified design and configuration standards for modular design, component classification, and digital protocols hinders the reuse of components across projects. Interviewee I3 noted:

“Working within P-DfMA is different, because you are configuring the design within a grid, not from a concept.”

Other design challenges include outdated design rules for building codes and regulations, which widely vary across regions and prioritize traditional construction methods, resulting in misalignment between P-DfMA practices and regulatory frameworks. Moreover, the limited availability of materials requires logistics networks and on-site assembly capacity. Interviewee I4 explained:

“There are very limited design guideline rules for P-DfMA adoption. Thus, we are figuring it out as we design.”

Within the TOE framework, the technological dimension includes limited material libraries, immature digital tools, and the absence of standardized design guidelines. The organizational dimension reflects teams’ struggles with misaligned expectations and resistance to modular constraints. The environmental dimension highlights the lack of comprehensive regulatory standards for environmental applications and industry-wide design references, which increases uncertainty. This notion suggests that design challenges are interconnected, as technological immaturity, organizational misalignment, and environmental uncertainty collectively slow down adoption. Overcoming these requires integrated interventions—technical standardization, organizational capacity-building, and policy frameworks—that reconcile modular efficiency with creative flexibility.

3.2.2. Design Considerations

The interviews reveal that design considerations in P-DfMA depend on how effectively design processes incorporate manufacturing logic from the outset. Accordingly, operations develop because P-DfMA thrives when design decisions anticipate not only construction but also operation and maintenance over the building lifecycle. In addition, material standardization is a cornerstone of P-DfMA, supported by robust design management to embed the concept throughout the delivery process. It ensures that design choices are validated against manufacturing tolerances, supply chain constraints, and on-site assembly requirements. Interviewee I5 noted:

“Our P-DfMA adoption accelerated by designing with operations, materials, and integration in mind. Standardizing materials and coordinating with manufacturers ensured buildable, scalable designs, while strong management and early contractor involvement reduced clashes and sped approvals.”

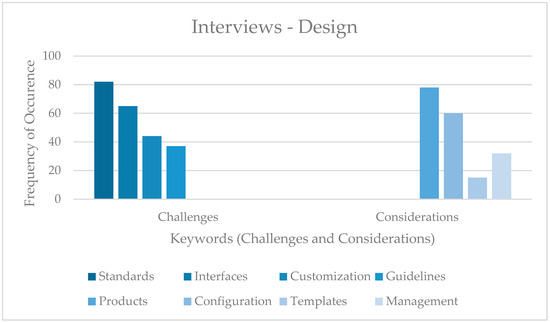

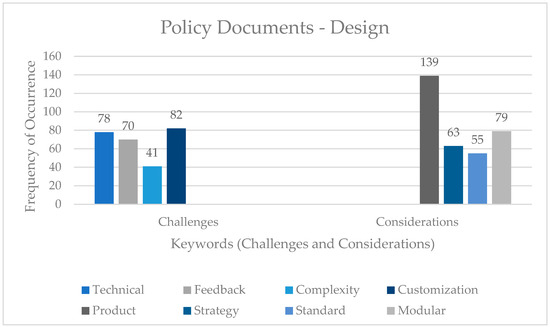

Figure 2 illustrates the most frequently repeated keywords related to the challenges and considerations of this factor. The participants identified insufficient design standards and interfaces as the main barriers. Design professionals emphasized the lack of customization and predefined design guidelines. The considerations’ results show that productization and configuration were the primary focus of all interviewees. Design management and design templates create feedback loops between design and delivery. These mechanisms ensure that design outputs remain manufacturable, repeatable, and scalable.

Figure 2.

Frequency of the most commonly used keywords by interviewees for design factors.

Within the TOE framework, the technological dimension includes reliance on standardized components and parametric rules. The organizational dimension reflects design management structures, including protocols, role clarity, and quality control. The environmental dimension includes supply chain and material availability constraints that shape the design process externally. Therefore, design considerations are not isolated technical concerns but rather multi-layered enablers of platform adoption.

The interview findings reveal that design standardization depends on early coordination with respect to digital, financial, and organizational factors. Strong design management and validated design choices enhance supply chain integration, aligning with the technological and organizational dimensions of the TOE framework. This connection emphasizes how design maturity underpins effective P-DfMA development in practice.

3.3. Digital Factors

3.3.1. Digital Challenges

The interviews highlight that digital challenges significantly constrain P-DfMA adoption due to incompatible software, inconsistent modeling standards, and a lack of common data protocols, which disrupt workflows and increase rework. P-DfMA relies on accurate, interoperable, and real-time data across disciplines, as well as cloud-based collaboration. The use of different digital tools, naming conventions, or information protocols leads to misaligned models and expectations, resulting in clashes between design intent and manufacturing feasibility due to the lack of harmonized standards across regions and firms. In addition, cloud platforms and shared data environments expose projects to data breaches, intellectual property theft, and contractual disputes over liability. Interviewee I7 explained:

“We spend more time fixing file compatibility than designing, because other engineers use different software. In addition, every stakeholder labels things differently, even when it’s standardized. It is because they evaluate and work differently from each other.”

Within the TOE framework, the technological dimension shows misalignment of software, inconsistent BIM standards, and unreliable component libraries. The organizational dimension reflects that teams require leadership, training, and clear responsibilities to manage complex digital workflows. The environmental dimension encompasses suppliers, manufacturers, and clients that operate with varying digital capabilities and standards, often lacking environmental guidance and standards. This notion suggests that digital and data management challenges are systemic. Addressing these challenges requires coordinated technological investment, organizational capability-building, and alignment with environmental requirements to enable the secure and interoperable adoption of P-DfMA.

3.3.2. Digital Considerations

The interviews reveal that digital considerations in P-DfMA extend beyond tool selection to coordinated digital infrastructures, standards, and adaptability to software, because P-DfMA depends on seamless information flow between stakeholders. Coordinated infrastructures improve information transfer and ensure that design choices align with manufacturing and assembly requirements. Industry-wide digital standards, along with a wide array of software and rigid platforms, create interoperability across software and organizations, making digital assets reusable and comparable across projects. This enables the P-DfMA logic of repeatability, as Interviewee I12 explained:

“What really made a difference in our P-DfMA projects was having a coordinated digital environment and clear standards. Once everyone was working from the same cloud platform and following the same data conventions, collaboration became much smoother.”

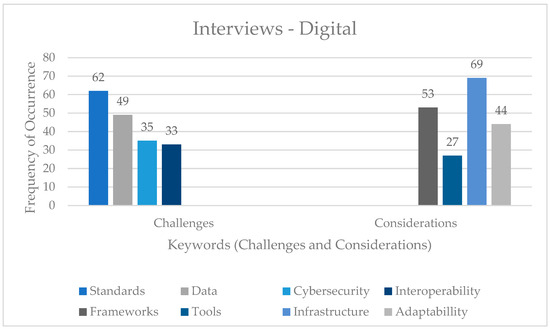

Figure 3 illustrates the focus of each interviewee regarding digital challenges and considerations. Concerns regarding poor digital standards, data management, cybersecurity, and inadequate digital interoperability were prevalent across the interviews. Interviewees agreed on the need for digital frameworks and infrastructure to maintain design responsiveness. Architects emphasized the need for digital tools and technological adaptability, while BIM coordinators and consultants focused on software development and standardization to minimize errors and rework. This finding suggests that digital systems need to strike a balance between rigidity for interoperability and flexibility for creativity and project variation.

Figure 3.

Frequency of the most commonly used keywords by interviewees for digital factors.

Within the TOE framework, the technological dimension encompasses digital adoption, which hinges on interoperable standards and resilient cloud-based infrastructure. The organizational dimension reflects trust in shared environments within organizations, with clear governance over data ownership, version control, and access rights. The environmental dimension refers to industry-wide BIM standards, client requirements, and regulatory endorsement of interoperable formats supporting adoption. Accordingly, digital considerations are not simply technical upgrades but rather are interconnected with organizational trust and environmental alignment. For P-DfMA to scale, it is necessary to institutionalize digital standards through governance and reinforce them with external frameworks that mandate interoperability across projects and supply chains.

The interviews highlight how fragmented digital standards and interoperability issues directly affect design, financial, and organizational performance. Coordinated infrastructures and adaptable software are central to technological capability-building under the TOE framework. Thus, digital maturity serves as a technological enabler, supporting collaboration across various domains.

3.4. Financial and Procurement Factors

3.4.1. Financial and Procurement Challenges

The interviews revealed that financial and procurement factors significantly constrain P-DfMA adoption. Such factors include both direct and indirect costs and fees, as well as savings, procurement structures, contracts, and material specifications.

The high upfront costs for digital tools, custom libraries, and workforce training lack alignment with the market structure and industry characteristics, hindering their effective implementation. Therefore, a misalignment exists between initial costs and perceived market benefits, especially in single-project delivery models. Moreover, there is an inability to quantify long-term savings, which complicates the justification for investment. This notion reflects the integration of technological and environmental challenges within the TOE framework. Interviewee I8 noted:

“We need to invest heavily before the client even agrees to the approach. We also can’t promise savings when the benefits only appear on later projects, not the first one.”

Beyond direct costs, P-DfMA implementation requires investments in workflow redesign, early-stage collaboration, and coordination across multiple stakeholders, generating hidden costs that are often overlooked in conventional fee structures. These challenges reflect the combination of technological and organizational dimensions of the TOE framework. Therefore, smaller practices face heightened challenges due to limited funding, which restricts experimentation with new tools and workflows. Interviewee I9 noted:

“Implementing the P-DfMA approach adds hours of coordination, but we are still working within fixed fee agreements that do not account for it. Thus, we stick to what we know because there is no budget to test anything new.”

P-DfMA procurement structures further exacerbate adoption and contract challenges because P-DfMA requires early collaboration, rather than relying solely on the lowest-cost tendering and siloed responsibilities. Procurement rarely rewards risk-taking in investments in digital tools, material and component specifications, and prefabrication facilities because it requires integrated procurement, such as design–manufacture partnerships, which create barriers to sharing knowledge and joint decision-making. Accordingly, integrations exist between technological, organizational, and environmental challenges in the TOE framework for procurement adoption. Interviewee I6 explained:

“By the time the manufacturer is involved, it is too late to change the configuration of the project. In addition, everyone protects their own scope. As a result, there is no incentive to align.”

The results show that financial and procurement challenges are not merely cost issues but reflect systemic interdependencies. Addressing them requires simultaneous technological investment, organizational change, and alignment with environmental and policy contexts to ensure P-DfMA is financially viable and operationally implementable.

3.4.2. Financial and Procurement Considerations

Business models, cost guidelines, and standardized specifications can improve the financial aspects of P-DfMA adoption. Repeatable systems shift the focus toward research and development (R&D) and tooling costs across multiple projects to define lifecycle cost savings, as well as shifting evaluation from the lowest bid to value-based procurement based on more transparent financial decision-making. This approach reduces financial uncertainty, aligning with the TOE framework through digital standard specifications for system interoperability, business model alignment with stakeholders’ incentives, and cost guidelines that shape procurement policies and client expectations. Interviewee I6 noted:

“We reused 80% of the model from the last projects. This helps us to shift the focus toward standard specifications, model development, and guidelines.”

Governance guidelines and policies can facilitate contract reform, integrated cross-disciplinary training, and coordinated workflows among stakeholders. They support long-term supplier relationships, enabling early contractor and manufacturer involvement in the design and alignment of incentives across stakeholders to achieve greater lifecycle value rather than simply lower initial costs. This approach ensures that architects understand manufacturing tolerances, engineers understand modular constraints, and contractors understand logistics, thereby reducing misalignment and fostering a shared language for the effective use of digital tools. Standardized workflows and BIM integration, along with training and shared competencies, are applied to integrate the TOE framework. Additionally, policy-driven contract reform and procurement frameworks are utilized. Interviewee I13 noted:

“Our contracts still reward the cheapest upfront price, which makes long-term collaboration almost impossible. If the government introduced standard frameworks or policies that supported integrated contracts, manufacturers could actually invest in capacity.”

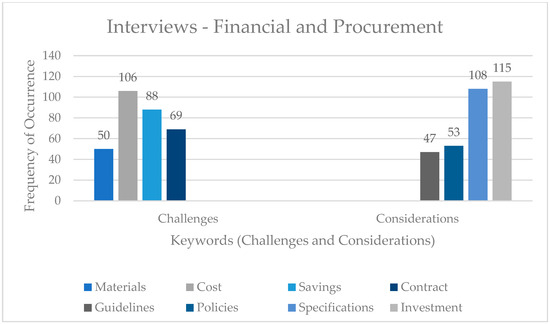

Figure 4 illustrates the focus of interviewees in different roles for financial and procurement in challenges and considerations. Interviewees emphasized the challenges of high upfront costs and limited savings, as well as poor material specifications for financial and procurement contracts when adapting P-DfMA in the AEC industry. Thus, architects, design managers, and BIM coordinators emphasized the need for design guidelines and policies, while technical consultants stressed the need for technical specifications and investments for pilot projects. This finding indicates not only revised cost models but also industry-wide standards for role definition, transparency, and enforcement.

Figure 4.

Frequency of the most commonly used keywords by interviewees for financial and procurement factors.

The interview findings reveal that financial challenges, including upfront digital costs and misaligned value perceptions, are closely tied to design, digital, and organizational domain factors. Aligning procurement with research and innovation enhances both organizational and environmental capacities within the TOE framework, supporting sustainable investment in P-DfMA adoption.

3.5. Organizational Factors

3.5.1. Organizational Challenges

The interview findings revealed that organizational barriers significantly constrain P-DfMA adoption, stemming from skills gaps, fragmented communication and collaboration, and misaligned leadership expectations. P-DfMA requires a combination of digital skills and systems thinking. Many AEC professionals are trained in traditional design and construction methods, reflecting a mismatch between available skills and the new technical capabilities needed. Moreover, the absence of P-DfMA literacy leads to dependency on external specialists, which slows the adoption. Additionally, P-DfMA necessitates early-stage cross-disciplinary collaboration, as design decisions significantly influence manufacturing feasibility and supply chain integration. Miscommunication and poor collaboration lead to duplication of efforts and difficulties in aligning design with manufacturing and assembly constraints. Another cause is conflicting priorities, with some leaders focusing on short-term project delivery and cost minimization, and others pushing innovation without clear implementation strategies. These conflicts arise because P-DfMA requires long-term investment, cultural change, and a commitment to standardized processes. Interviewee I10 explained:

“Our team is not trained for implementing P-DfMA; it is a whole new skill set we are missing and learning by ourselves. Thus, team members assumed that P-DfMA is about software, but it is a whole way of working.”

With respect to the TOE framework, this challenge shows that technological investments fail to yield efficiency without integrated organizational training, standardized workflows, and early manufacturer involvement. Siloed project structures and limited coordination highlight how external conditions and internal capabilities intersect to hinder adoption.

3.5.2. Organizational Considerations

The interviews indicate that organizational considerations in P-DfMA adoption extend far beyond individual skills or tools. Participants emphasized the importance of responsibilities, reskilling, knowledge transfer, and collaboration in enhancing the organizational aspects of P-DfMA adoption. P-DfMA requires integrated workflows, where design, manufacturing, and assembly decisions are interdependent. If responsibilities are clear, accountability gaps disappear. Clarifying decision-making authority helps in this respect, preventing the duplication of effort and creating accountability for both risks and outcomes. P-DfMA also demands skills and knowledge of modular systems, digital tools, and manufacturing logic. Accordingly, structured training programs, upskilling in digital technologies, knowledge management systems, and exposure to manufacturing practices are crucial for building a workforce capable of translating P-DfMA strategies into operational efficiency. Interviewee I14 noted:

“One of the biggest developments we are working on is how our teams are organized by defining who is responsible for coordinating with manufacturers, and many do not have the skills to use the digital tools effectively. Thus, we had to invest in reskilling and clarify roles to make the process smoother and more efficient.”

Figure 5 illustrates the perspectives of interviewees regarding the organizational challenges and considerations. Interviewees emphasized the limited training, the need for leadership to overcome misunderstandings, and poor coordination as barriers to P-DfMA adoption. Design professionals defined the need for knowledge-sharing mechanisms and collaboration, while technical consultants explained the importance of clear responsibilities and technical reskilling. Therefore, a broader need exists for coherent organizational infrastructures that support continuous learning.

Figure 5.

Frequency of the most commonly used keywords by interviewees for organizational factors.

According to the TOE framework, the findings reveal that organizational considerations for P-DfMA hinge on three interconnected factors: leadership-driven institutional alignment, redefined roles and digital training linked to cross-disciplinary workflows, and formal knowledge management systems.

The interviews suggest that gaps in skills, collaboration, and leadership hinder digital implementation and design coordination. Addressing these gaps through reskilling and effective communication aligns with the design, digital, and financial factors, as well as the TOE framework, and supports technological readiness for P-DfMA application.

The interview results reflect practitioners’ perspectives on how to define P-DfMA and the challenges facing its adoption in the AEC industry, addressing the first research question. Additionally, they highlight key considerations and the TOE framework for implementation, addressing the second research question. In addition, these factors are interrelated. These findings deepen understanding of the factors influencing P-DfMA adoption in practice.

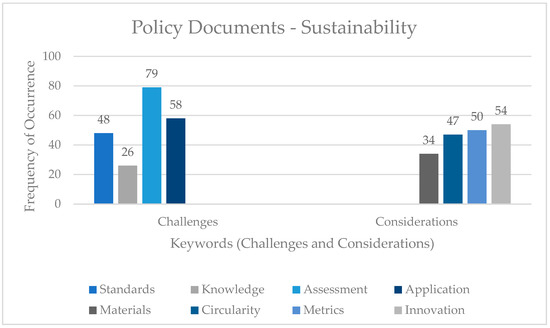

4. Policy Document Analysis Results

This section presents the results of analyzing policy documents with respect to five interrelated domains: design, technology, finance, organization, and sustainability. The challenges and key considerations related to each dimension are identified, addressing the first and second research questions, respectively. The challenges and considerations associated with each domain are also discussed in the context of the TOE framework.

4.1. Design Aspects

4.1.1. Limitations of Design Adoption

Design challenges in P-DfMA largely stem from complexity, fragmentation, and misalignment across design, supply chains, and industry practices. These issues constrain adoption, reduce efficiency, and limit the demonstrable benefits of platform strategies because complex, multi-tiered supply chains make precise planning difficult. Delays or variability at any point in the supply chain can disrupt sequencing, affect costs, and reduce the reliability of pre-assembled components. Furthermore, the absence of established product architectures and elemental product breakdown structures exacerbates these challenges. Uniclass or similar classification systems list components but fail to define relationships, making it difficult to identify cost- or time-driving elements. Iteration cycles are complex, and the concept of product architecture is not widely understood in the construction sector, limiting consistency and repeatability. Thus, without standardized, agreed-upon metrics, assessing design performance and platform benefits is difficult. Variability in measurement approaches undermines confidence in productivity gains, lifecycle performance, and design efficiency. Limited continuous improvement mechanisms and minimum data capture frameworks prevent the validation of platform benefits.

Existing methodologies [49] for cost breakdowns remain trade-based rather than product-focused, creating misalignment with modern methods of construction (MMC) approaches. Therefore, shifting from project- to product- and portfolio-level thinking is necessary because large clients with diverse pipelines are poorly aligned with broad product platforms. In addition, pilot schemes exist but lack scale, formalized methodology, and consolidated outputs to provide authoritative guidance or management toolkits.

Platform adoption fails to deliver measurable improvements in productivity, functionality, performance, or aesthetics because operational stoppages, ad-hoc quality, and technical dependencies—such as superstructure effects, tolerances, and embodied carbon—reduce perceived and actual value. In addition, low productivity growth in the construction sector, coupled with error-related costs (approximately 20% of spend), limits the ability to demonstrate platform advantages [49]. Thus, without formalized performance metrics and centralized data environments, claims of efficiency or quality remain unverified, and continuous improvement is hampered.

There is no widely accepted approach to quantify benefits from off-site construction or P-DfMA methods. Accordingly, building standards, including fire safety, require simplification to align with platform thinking, while industry perceptions that standardized components are of lower quality create resistance.

Terminology related to P-DfMA is inconsistently understood across the industry. Inadequate guidance exists for ensuring the effective adoption of associated processes, including planning, building control, and insurance, which lag behind technological and methodological advances, creating procedural barriers to implementing platform-based solutions.

Within the TOE framework, design challenges require interoperable technological systems and seamless data exchange across design software. The design process demands manufacture-led workflows, cross-disciplinary collaboration, and continuous feedback. Environmental integration embeds performance standards and certifications that reflect platform benefits. Interoperability across policies, regulations, and procurement frameworks is essential. Without alignment, organizations encounter inconsistent requirements, hindering adoption, scaling, and the effective implementation of standardized design processes.

4.1.2. Enablers of Design Adoption

Design considerations in P-DfMA emphasize repeatability, modularity, standardization, and the strategic integration of manufacturing and assembly processes. This notion highlights the importance of manufactured components in reducing dependence on complex, project-specific design information by delivering pre-tested, plug-and-play solutions. Components should be designed for ease of production, assembly, and testing, with standardized quality assurance procedures. The use of repeatable prototypes and modular assemblies, such as Bryden Wood’s external wall insulation system (EWIS) cladding or standardized brackets, enables predictable outcomes, reduces errors, and supports self-reinforcing system development [34,50]. Thus, dividing work into temporary and permanent components, planning assembly processes, and analyzing equipment requirements ensures that P-DfMA maximizes efficiency. In addition, manufacturing and assembly analyses—including part count reduction, complexity assessment, tolerance analysis, and assembly sequencing—provide systematic methods for optimizing processes, linking operator training with facility capacity, and enabling informed iterations before production runs.

Precise planning using P-DfMA minimizes operational stoppages and supports continuous workflow. Strategic tools, such as the value toolkit for building product platforms, define client needs, evaluate concept options, guide detailed design, manage procurement, and oversee operations.

Elements are classified as captive, boundary, or system elements [51,52], depending on their spatial interaction. Developing industry-wide standards establishes a level playing field, clarifying compliance expectations, reducing uncertainty for all stakeholders, and ensuring that design data are clear, consistent, and actionable.

Platforms enable rationalization of space types by defining repeatable, configurable elements. Accordingly, the design focus shifts from individual buildings to functional spaces, allowing replication across assets, improving efficiency, and supporting flexible use of government or commercial properties. Thus, defining space sizes and characteristics informs platform parameters, reducing complexity while retaining adaptability.

Platform strategies guide standardized dimensions, functional and support spaces, and mechanical, electrical, and plumbing (MEP) integration, enabling repeatable, scalable, and cost-effective solutions. Thus, types of platforms [50]—including organizational, product, ecosystem, or market intermediaries—distinguish between stable cores, variable peripheries, and interfaces to maximize flexibility and value capture.

Within the TOE framework, design considerations emphasize technological enablers for integration and interoperability, ensuring a consistent data flow between design, manufacturing, and on-site assembly to facilitate interoperability across disciplines and systems. Organizational integration reflects the shift from project-centric design to platform thinking. Implementing repeatable elements and front-loaded design requires cross-disciplinary coordination, structured workflows, and new roles for designers, engineers, and manufacturers. The environmental domain reflects design considerations that emphasize technical standards, quality assurance, and performance metrics validated by stakeholders. Embedding resilience, climate adaptation, and lifecycle performance into design practices makes environmental interoperability a central principle of P-DfMA adoption.

Figure 6 shows the most frequently used keywords in the policy documents for design challenges and considerations. Technical applications, design and customization complexities, and poor feedback loops are the major challenges for adapting P-DfMA in the AEC industry. Most policy documents focused on product configuration solutions through standardized kit-of-parts and repeatable modules, while other documents highlighted the importance of design strategies to guide the process. Therefore, policymakers believe that making designs more standardized and modular will make projects easier, faster, and more consistent, highlighting a shift toward strategic planning.

Figure 6.

Frequency of the most commonly used keywords in policy documents for design aspects.

The policy documents indicate that repeatability and integration of manufacturing with design processes require digital interoperability and financial stability. These policies align with the technological and sustainable aspects and dimensions of the TOE framework, reinforcing how design strategies relate to digital infrastructure and investment mechanisms to support systematic P-DfMA adoption.

4.2. Technology Aspects

4.2.1. Technological Barriers

A persistent technological barrier is the absence of reliable benchmark data for new systems, materials, and digital tools. Firms are reluctant to take on risk, and knowledge remains fragmented across projects and organizations. The limited transfer of lessons learned and inconsistent access to design information—particularly in BIM environments—reduce the sector’s ability to compare solutions, scale successful practices, and drive standardization. Therefore, confidence in adopting platform-based methods is undermined, perpetuating the reliance on bespoke, project-specific approaches.

The highly fragmented nature of the AEC industry makes it difficult to scale digital adoption across supply chains, even when configurators and digital tools are available. Misaligned standards, poor integration between platforms, and limited interoperability create silos rather than shared value. For instance, the National Metrics Library (NML) [53] suffers from low adoption due to limited integration with other platforms, a lack of sustained sponsorship, and competition from parallel initiatives. These dynamics dilute the impact of collective efforts and prevent the industry from building critical mass around shared digital infrastructures.

Even where digital tools exist, their design and governance limit adoption due to complex submission processes, barriers to metric review, perceived duplication with other initiatives, and the absence of clear thematic frameworks, which reduces user engagement. Therefore, a misalignment exists between design tools and industry practices, limiting usability, transparency, and practical incentives.

Certain digital and manufacturing capabilities are acquired through practice-based training, which requires a greater involvement of non-academic providers, such as vocational institutes, industry associations, and manufacturers. The current skills ecosystem remains overly dependent on academic curricula, which do not fully reflect the applied competencies needed for P-DfMA. Thus, investment in practical training allows firms to build the necessary workforce capacity to deploy digital tools and processes at scale.

Within the TOE framework, challenges such as fragmented, non-standardized digital systems, misaligned governance, limited workforce training, risk-averse clients, and regulatory uncertainty create a cautious environment that discourages experimentation.

4.2.2. Technological Enablers

Delivering high-quality digital infrastructure is foundational to scaling P-DfMA. It encompasses not only hardware and connectivity but also digital design and manufacturing platforms—such as BIM, digital twins, configurators, virtual marketplaces, and point cloud surveys—that enable accurate modeling, coordination, and prototyping. Unified classification systems (e.g., Uniclass 2015 [54]) and common data environments (CDEs) ensure consistent language and interoperability across tools, enabling actors to collaborate effectively by ensuring that product data is structured, validated, and comparable.

Digitalization enables the systematic collection, interpretation, and use of data to drive productivity, sustainability, and innovation. This notion reflects the growing adoption of BIM, which embeds frameworks for information management, data governance, and visualization. Advanced BIM and digital twins enable the simulation of stresses, sequencing, and safety checks, while automated workflows reduce repetitive tasks, allowing designers to focus on value creation. Open-source platforms and digital marketplaces democratize access, creating more inclusive supply chains.

By defining digital interfaces, parts count, and coding systems, digitalization extends directly into fabrication and construction logistics. Accordingly, the seamless transfer of requirements from design libraries into manufacturing databases is enabled, reducing errors and enhancing predictability. Linking modeling tools to manufacturing processes supports mass customization and just-in-time logistics, while digital walls and dashboards help monitor deliveries, progress, and performance trends.

Sustained investment in artificial intelligence (AI), robotics, and advanced manufacturing methods is essential to unlock the potential of P-DfMA. Prototyping and shared learning platforms accelerate the testing of new technologies. Initiatives such as the Construction Innovation Hub [55,56] provide structured frameworks for adoption. At the same time, innovation strategies remain flexible and methodology-agnostic to avoid technological lock-in. R&D ensures that platforms remain adaptive and competitive in the face of evolving materials, techniques, and environmental pressures.

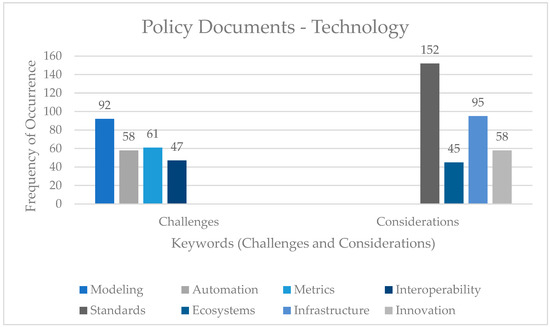

Figure 7 shows the distribution of the most frequently used keywords related to technological challenges and considerations in the policy documents. The policy documents identified digital modeling, insufficient automation application, poor digital metrics for evaluation, and limited digital interoperability as significant challenges for adapting P-DfMA in the AEC industry. Most policy documents emphasized defining ecosystems for innovation and standards for application, while others focused on software and technological infrastructure for adoption. This finding suggests that there is no single technological priority, but rather an understanding that innovation, standardization, and infrastructure investment all play key roles in advancing digital design capabilities.

Figure 7.

Frequency of the most commonly used keywords in policy documents for technological aspects.

Within the TOE framework, robust digital infrastructure underpins integration through standardized data structures and unified classification in the technological dimension. The organizational dimension is crucial for scaling technological tools through workforce skills, governance, and leadership. The environmental context shapes technological and organizational decisions, emphasizing sustainability, compliance, and market pressures. Digital tools facilitate decarbonization, lifecycle analysis, and efficiency, while modular construction enhances supply chain resilience.

The policy analysis results show that digital transformation depends on systematic data governance and integration with organizational workflows. This insight connects the digital domain aspect with financial and design processes, illustrating how policy consistency strengthens technological and organizational enablers in the TOE framework for P-DfMA expansion.

4.3. Financial and Procurement Aspects

4.3.1. Barriers to Financial and Procurement Adoption

The financial dimension reveals a persistent misalignment between the industry’s investment needs for innovation and its capacity to meet them. Despite recognition that productivity gains depend on capital investment, firms report that such investments have not translated into measurable efficiency improvements. Consequently, reluctance has emerged among private investors, who perceive the sector as high-risk and characterized by poor predictability, frequent delays, and cost overruns. The absence of stable, long-term funding mechanisms amplifies the problem, preventing companies from planning strategically for platform adoption or sustained R&D. Companies hesitate to invest in P-DfMA because they cannot guarantee a return on investment. Thus, they prefer to focus on short-term benefits that depend on public or alternative funding.

For small and medium-sized firms, access to financing is restricted, and high upfront costs for factory setup and training create prohibitive barriers to entry. These conditions reinforce dependence on short-term contracts and narrow profit margins, leaving little room for experimentation.

In the TOE framework, financial challenges reduce incentives for leaders to prioritize platform adoption, sustainable public funding, and coherent investment programs for digital P-DfMA adoption.

Procurement processes remain significant barriers to P-DfMA adoption because current P-DfMA models [57] are fragmented, relying on late tendering, incomplete documentation, and misaligned contractual structures. These conditions increase risk premiums, encourage power imbalance, and perpetuate siloed project delivery.

Despite the potential of government procurement [58] to shape the market, it has not provided a mature, consistent pipeline or unified strategy. Uncertain, disrupted supply chain integration, weak business models for P-DfMA solutions, a lack of robust selection criteria, and misalignment between policy ambitions and procurement practices have further hindered innovation uptake.

Procurement protocols [59] tend to prioritize lowest-cost delivery rather than whole-life performance, which undermines the benefits of manufacturing-led approaches. Smaller suppliers face high upfront costs and risks, which can lead to production being pushed offshore and a threat to local supply chain resilience. Without procurement reform, the opportunity to link payment mechanisms to long-term asset performance remains underexploited.

From a TOE perspective, these challenges illustrate how technological integration (digital applications), organizational processes (procurement practices), and environmental conditions (government policy and market dynamics) interact to block the scaling of P-DfMA. Even when technological readiness exists, procurement misalignment constrains implementation, creating a systemic barrier to innovation.

4.3.2. Financial and Procurement Enablers

A central financial consideration is the need to stabilize and progressively increase investment in ways that avoid the traditional boom-and-bust cycles of the construction sector. Mechanisms such as the industry stabilization plans [60] are intended to co-invest with private actors, reduce volatility, and provide firms with long-term funding certainty. These measures suggest a shift in industry behavior away from short-term project financing and toward strategic investments in innovation, training, and supply chain resilience.

Ensuring that funding is transparent, accessible, and consistent is also vital. Simplifying access to loans, bonds, and insurance products lowers the barriers faced by small and medium-sized firms, while reforms to targeted funds for building safety create opportunities to align financial flows with wider policy objectives. Framing investment not solely around cost reduction but around whole-life value, reducing rework, waste, and defects, allows financial models to support the broader productivity and sustainability goals of P-DfMA.

Within the TOE framework, these financial considerations influence firms’ ability to adopt long-term technological plans, invest in skills, and manage cash flow sustainably. These financial considerations also reflect regulatory certainty, state co-investment, and macroeconomic instruments.

Reforming procurement is recognized as a cornerstone for enabling P-DfMA delivery because it aligns contractual terms with long-term value creation rather than short-term cost minimization. Approaches such as alliancing [60] and digital procurement platforms [61] are positioned to reduce fragmentation and promote competition.

Embedding value-based procurement [62] is particularly significant, as it moves beyond lowest-price tendering toward evaluation frameworks based on whole-life cost, performance, and social value, directly supporting the systemic benefits of P-DfMA. It supports early supplier engagement and portfolio-level procurement to reduce program timescales, stabilize pipelines, and encourage suppliers to invest in capacity, innovation, and digital tools.

As the industry’s largest client, the government plays a decisive role by establishing standards, frameworks, and incentives that promote the mass adoption of product platforms, harmonize technical requirements, and provide clear performance benchmarks. This top-down consistency enables the industry to plan around predictable demand while driving integration across the supply chain.

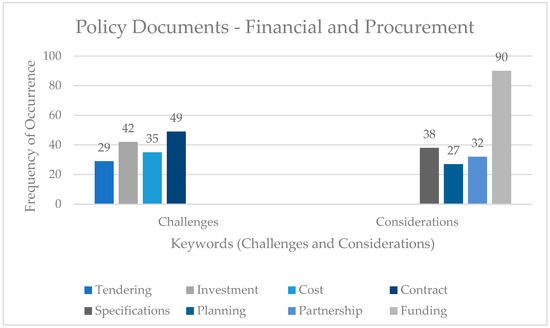

Figure 8 shows the most frequently used keywords in the policy documents related to financial challenges and considerations. Most policy documents emphasized the importance of the governmental role in defining the policies, strategic guidelines, and funding R&D to establish standards and specifications for materials, components, processes, and applications. Other documents emphasized the importance of detailed planning processes and roadmaps for implementing P-DfMA, helping to overcome the defined issues of poor tendering and contracts, limited investment, and high upfront costs. Accordingly, governmental support is crucial for adopting and advancing P-DfMA. Governmental financial backing and structured planning are viewed as key enablers for large-scale adoption of P-DfMA in the AEC industry.

Figure 8.

Frequency of the most commonly used keywords in policy documents for financial aspects.

Within the TOE framework, these procurement considerations are reflected both technologically and organizationally through new contracting models, early collaboration, and risk-sharing arrangements, as well as environmentally through government-led policies, regulatory reforms, and pipeline visibility. Therefore, procurement is not merely an administrative process but rather a strategic enabler of systemic transformation in the AEC industry.

The policy documents reveal that stable, transparent funding mechanisms and coherent long-term investment programs are crucial for advancing digital and design integration. These financial considerations encompass the technological, organizational, and environmental aspects and dimensions of the TOE framework, ensuring that policy-driven stability supports technological growth and resilience in the AEC industry.

4.4. Organizational Aspects

4.4.1. Organizational Constraints

Organizational aspects of P-DfMA adoption face a series of systemic challenges that hinder effective transformation. These challenges are interlinked, with workforce capacity, client engagement, and industry culture all affecting efficiency, quality, and long-term sustainability. This notion is attributed to labor shortages, particularly the reliance on an aging population and the limited inflow of younger, skilled labor. At the same time, the industry faces difficulties in retraining workers for emerging practices such as off-site construction and digital methods. Risks extend beyond capacity, as construction consistently records high fatality rates and poor well-being outcomes, with suicide rates double those of other occupations [49]. Thus, the challenge is therefore not simply to fill labor gaps but also to reshape the work environment to attract, retain, and adapt the workforce to new roles and tools. There is a shortage of digital talent because skilled professionals often avoid the industry, perceiving it as less technologically advanced than others. This results in insufficient expertise to validate data-driven metrics, manage digital twins, and ensure interoperability across platforms. This lack of capacity manifests in poor productivity, operational stoppages, and increased rework.

Suppliers struggle with self-checking mechanisms before submission, while clients often encounter inefficiencies in verifying compliance, leading to delays, cost escalations, and dissatisfaction. Client-side variations and weak approval processes exacerbate the problem, leading to perceptions of poor investment and underperformance. As a broader systemic issue, there is an absence of robust governance frameworks and quality assurance mechanisms that ensure consistency across multiple project stages.

Cultural challenges persist, reinforcing inefficiency and undermining transformation. The industry continues to undervalue digital and manufacturing skills, clinging instead to transactional and short-term practices. Low pay, insecurity, and a lack of diversity further reduce the attractiveness of careers, while resistance to methodological change slows the adoption of automation and sustainability measures. This cultural inertia prevents the shift toward collaborative, innovation-driven practices that are necessary for long-term competitiveness.

Education and training systems are not evolving sufficiently quickly to keep pace with the rapid growth of digitalization and P-DfMA adoption. Apprenticeships and professional development remain underdeveloped, and training is inconsistently delivered across disciplines. New competencies such as P-DfMA and MMC require digital literacy, logistics, transformational leadership, and business analysis. However, the current implementation is patchy, and the lack of skills gap analysis at scale means the sector risks entering a cycle of fragmented adoption, knowledge silos, and a workforce that is unprepared.

Partnerships are patchy, with professional networks fragmented and often localized, making it difficult to scale adoption and ensure consistency. Due to poor collaboration, knowledge transfer is poorly managed, resulting in valuable insights often being lost after project completion. A lack of systematic lifecycle guidance and interdependent treatment of data and process lifecycles further undermines efficiency.

Viewed from the perspective of the TOE framework, technological shortcomings drive organizational challenges through limited integration of digital tools, workforce shortages, misaligned training, and cultural resistance, which create bottlenecks. The environmental dimension places organizational challenges within broader systemic contexts. Policy requirements, sustainability mandates, and labor market dynamics influence operations, while limited academic collaboration and fragmented knowledge transfer hinder innovation.

4.4.2. Opportunities for Organizational Adoption

Addressing the organizational aspects of transformation for P-DfMA adoption requires a forward-looking strategy that strengthens capabilities, improves collaboration, and embeds knowledge-sharing as part of everyday practice. A fundamental consideration is the need for a step change in organizational capability and leadership. Therefore, sustained investment in vocational, professional, and digital training is necessary, alongside leadership development. Moreover, stronger direct employment models are needed to sustain apprenticeships, reduce precarity, and enable systematic upskilling. Leadership commitment—from estates teams to senior management—is also essential to drive culture change, foster accountability, and embed platform thinking into organizational practice.

The AEC industry needs to increase digital literacy and strengthen collaborative working practices, improving the skills base and simplifying the skills system through coordinated structures. Employers must play an active role in addressing gaps and creating long-term pipelines, supported by workforce strategies tailored to industries facing persistent labor shortages.

Education and outreach initiatives remain central to sustaining momentum. Programs and partnerships with higher education institutions, industry, and employers, as well as initiatives promoting inclusivity and access [63], demonstrate the importance of early engagement in reshaping the perception of construction careers. Modernizing training and qualifications ensures their fitness for purpose, while new delivery modes such as distance learning extend accessibility. In addition, continuous professional learning must extend across all levels from senior managers to project supervisors, enabling multi-skilling and ensuring that training translates directly into quality outcomes. The value derived from platforms is partly realized through the reduction of learning curves, meaning that training creates value in terms of efficiency and improved performance.

Closer collaboration between academia and industry is a key enabler of innovation and skills development. Joint initiatives are essential for advancing training in digital, manufacturing, and off-site methods. Open-source platforms for sharing lessons learned and best practices can ensure the diffusion of knowledge across firms and disciplines. Site-based training records, environmental surveys, and live access to project data are leveraged for educational purposes, bridging the gap between research and practice. By embedding a platform mindset into education, clarifying roles, responsibilities, and collaborative approaches, the industry can create more resilient knowledge systems.

Fostering innovation requires long-term, trust-based partnerships among clients, project teams, and suppliers, facilitated through collaboration, performance measurement, and sustained relationships, to strengthen regional clusters and partnerships.

Clients play a pivotal role in shaping organizational outcomes by developing the capability to understand the scope of buildings that can be served by a product platform, the elements that most influence value, and the opportunities for commonality that generate efficiency. Pre-commencement engagement and structured onboarding of client groups ensure that expectations are aligned. Direction from major clients can balance the pursuit of better value with fair and sustainable profit margins for suppliers.

Knowledge transfer is a core organizational priority. Accordingly, central leadership and coordinated effort are necessary to reduce learning curves and embed platform principles in everyday operations through collegiate forums, open-source knowledge tools, and collaboration with industry leaders to accelerate adoption.

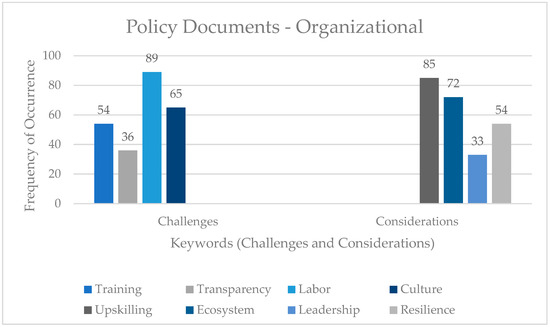

Figure 9 shows the most frequently used keywords in the policy documents related to organizational challenges and considerations. Most policy documents highlighted labor upskilling and organizational ecosystems across sectors to improve knowledge-sharing transparency and overcome the limited labor skills and training. Others emphasized the need for partnerships between the governmental, academic, and private sectors to advance leadership and resilience in overcoming the resistance to adopting P-DfMA. Policymakers view skilling and cooperation as key organizational factors for successful P-DfMA adoption, as they are essential enablers for advancing P-DfMA.

Figure 9.