Abstract

This study explores the enhancement of spatial vitality in the Historic Center of Macau from the perspective of museumification theory. This research employs GIS technology to analyze Baidu heatmap data, comparing the differences in spatial vitality between the festive and daily periods. Furthermore, experiential quality questionnaire data were collected from 224 tourists visiting the historical district, constructing a theoretical model of “objective vitality–experience quality”. Through objective analysis, the results indicate that the distribution of vitality in the Historic Center of Macau exhibits a clear core–periphery diffusion pattern. During the festive period, the intensity of spatial vitality significantly increases. Through subjective analysis, this study reveals that experiential quality has a significant impact on spatial vitality. Among the dimensions, education and inspiration, cultural exchange, and entertainment enjoyment have a notably positive effect on spatial vitality. The elements of education and inspiration play a crucial role during festive periods—particularly artistic attractions and educational entertainment—which positively influence vitality. This study innovatively applies museumification theory to the research of vitality in a historical district, providing valuable references for the sustainable cultural tourism development and cultural heritage preservation of the Historic Center of Macau.

1. Introduction

The rapid development of cultural tourism has led to a significant spatial imbalance in vitality distribution within the Historic Center of Macau. According to statistics from the Macau Government Tourism Office, during the International Workers’ Day holiday in 2025, Macau received nearly 177,000 visitors. The Ruins of St. Paul’s and the Holy House of Mercy attracted a large number of tourists due to their uniqueness and high recognition, resulting in a high level of spatial vitality. Meanwhile, other cultural heritage sites remain relatively neglected and receive less attention [1,2,3]. Therefore, how to effectively enhance the spatial vitality of the Historic Center of Macau, support its status as a World Center of Tourism and Leisure, and promote the development of cultural tourism have become urgent issues.

Previous research has primarily focused on the impact of the physical environment on the spatial vitality of historical districts while neglecting the role of cultural vitality as an intrinsic driving force. Musealization is regarded as an effective strategy for enhancing cultural vitality [4,5]. It plays a significant role in the preservation of historical districts and the promotion of cultural tourism [6]. However, there is currently a lack of systematic theoretical construction and empirical analysis methods. Quantitative research on the spatial vitality of historical districts can currently be categorized into two approaches [7]. The first is based on population density data to reflect the dynamics of historical districts. The second employs methods such as surveys to collect subjective experiences of space in historical districts, providing references for improvement suggestions [8]. However, research that combines both approaches is relatively scarce. Given the urgent need for the transformation of the historical and cultural city, there is a pressing requirement to establish a comprehensive vitality assessment method. This would enhance the spatial vitality of historical districts and promote cultural regeneration.

This study attempts to answer the following three questions: (1) How can the Historic Center of Macau be deconstructed based on the theoretical framework of musealization? (2) From the perspective of musealization, what are the characteristics of spatial vitality in the Historic Center of Macau during daily and festive periods? (3) Are there differences in the factors influencing tourists’ subjective perceptual experiences between daily and festive periods? Which elements of subjective perceptual experiences affect the quality of the experience in the historical district?

This study explores the spatial vitality of the Historic Center of Macau based on the “objective vitality–experience quality” model from the perspective of musealization. The research deconstructs the Historic Center of Macau, analyzing it from two temporal dimensions: the daily period (permanent exhibitions) and the festive period (special exhibitions). By collecting Baidu heatmap data for the Historic Center of Macau during both the daily and festive periods and utilizing ArcGIS 10.8 to construct a vitality intensity model, this study investigates the characteristics of spatial vitality in the Historic Center of Macau. Through subjective evaluation methods, it compares the perceived experiences of visitors during the daily and festive periods to reveal the factors influencing the subjective vitality of the Historic Center of Macau.

The innovation of this study is reflected in two aspects. First, at the theoretical level, this research explores the spatial vitality of a historical district from the perspective of musealization, which is beneficial for the transformation and cultural regeneration of historical and cultural cities. Second, at the methodological level, this study combines the physical environment with subjective perception, which helps to more comprehensively investigate the spatial vitality of historical districts. The findings of this study offer valuable insights into the development of cultural tourism in the Historic Center of Macau. At the same time, it provides a theoretical basis and practical path for the transformation and development of other historic districts.

2. The Literature Review

2.1. Musealization of Historical Districts

The concept of “musealization” was first introduced by Czech museologist Zbyněk Stránsky in 1965. The original meaning of “musealization” is to extract “objects” from their real temporal and spatial contexts, transforming them into “museum objects” [9,10]. The process of musealization includes three aspects: (i) “loss of function” or “alteration of function”; (ii) “alteration of context”; (iii) “a new relationship between the subject (viewer) and the object” [11]. In recent years, the rise in cultural tourism has led historical cities to undergo profound transformations. Museum theory is widely applied in the research on the preservation of historic districts [12]. Many historical buildings are repurposed as museums, and cities or archaeological sites are regarded as open-air museums [13]. The boundary between museums and historical districts has disappeared [14,15].

Musealization has become a strategy for cultural regeneration in historical and cultural cities. Studies have shown that museums, art galleries, art centers, and other urban landmarks have become a part of the revitalization strategy for urban cultural regeneration [16]. For example, Frank Gehry designed the Guggenheim Museum. The construction of cultural facilities such as museums has led to the growth of regional economic activities [17]. Similarly, the city of Bath functions as a museum complex, becoming an important tool and means for attracting tourists [18]. The Istanbul Peninsula, along with historical cities such as Rome, has launched a museum city project proposing to view the entire city as a museum area to develop tourism. These studies show that musealization attracts people through the construction of cultural facilities or the organization of cultural activities, thus enhancing space vitality.

In terms of protection methods, musealization can be divided into static protection and dynamic protection. Static protection tends to focus on the preservation of the tangible cultural heritage of historical districts, emphasizing the authentic display of architectural heritage [19]. Dynamic protection emphasizes the dynamism and vitality of historical districts, presenting them in the form of exhibitions that encourage active participation from visitors [20]. Utilizing historical urban relics and festive activities to host special exhibitions can enhance the public’s cultural experience of heritage [21]. Diverse cultural activities (such as festivals, exhibitions, music festivals, etc.) can effectively enhance the spatial vitality of historical districts. Large cultural events serve as a culture-oriented strategy for the regeneration of historical districts. In particular, using traditional festivals for the cultural reproduction of historical districts can significantly enhance their attractiveness [22].

The Historic Center of Macau is a World Cultural Heritage of human settlements. The former director of the Cultural Affairs Bureau of the Macau Special Administrative Region Government, Wu Weiming, proposed the concept of building a Macau City Museum in 2014. Based on the theory of musealization, this study examines the Historic Center of Macau as an open museum. It explores how the intervention of Macau’s architectural heritage and intangible cultural heritage (festive activities) can enhance spatial vitality, thereby promoting cultural regeneration and sustainable development of the historical district.

2.2. Spatial Vitality

The concept of spatial vitality encompasses a wide range of meanings and implications. In 1961, Jane Jacobs proposed the concept of urban vitality in The Death and Life of Great American Cities, emphasizing the diversity of cities [23]. Jane Jacobs proposed that vibrant cities should have a rich array of social activities, well-designed public spaces, and lively street life. Kevin Lynch regards vitality as the primary criterion for assessing the quality of urban spatial form [24]. Jiang Difei proposed that urban vitality includes economic vitality, social vitality, and cultural vitality [25].

Scholarly research on the vitality of historic districts primarily focuses on two aspects. On the one hand, it explores the spatial vitality of historical districts from an objective perspective [26]. On the other hand, it examines the vitality of historic districts based on users’ subjective experiences and perceptions of space. Subjective vitality provides a deeper analysis of the interactions, behavioral patterns, and feelings between individuals and the space, thereby offering a more comprehensive understanding of their vitality [27]. These two research perspectives together contribute to understanding the complexity of historic district vitality and its application in practice.

In the study of the physical spatial attributes of historical districts, researchers quantify the vitality of these areas from various perspectives, including street layout, road network structure, land use, functional mixing and diversity, building density, and accessibility [28,29,30]. With the development of big data technology, many scholars have begun to use multi-source data to analyze the relationship between physical environments and spatial vitality. For example, GPS data, LBS data, mobile phone data, POI data, Baidu heatmap data, and Tencent data are widely used [31,32]. These large datasets contain geographic information and have become important tools for identifying spatial vitality.

In addition, other scholars observe and interpret historical districts from perspectives such as spatial quality, emotional experience, visual perception, and cultural activities to stimulate the spatial vitality of these historical districts. Zhang Yan et al. evaluated historical and cultural districts from a value perspective [33]. Cui Tingting et al. proposed that holiday activities can have an impact on spatial vitality [34]. These studies emphasize the perception and evaluation of spatial vitality from the user’s perspective. Research methods include surveys, interviews, and field observations. Moreover, with the advancement of big data technology, extensive experience evaluation data—such as social media data and street view data—have become effective tools for assessing the vitality of historical districts [35].

The integration of the physical environment and subjective perception will enable a more comprehensive exploration of the spatial vitality of historical districts. However, there is currently a lack of research that integrates both aspects. Therefore, this study combines objective and subjective vitality assessment methods to explore the characteristics of spatial vitality in historical districts. Objective vitality reflects the degree of crowd aggregation in space, while subjective vitality illustrates the interactive relationship between the physical environment and human perception, revealing the deeper mechanisms of spatial vitality.

2.3. Experience Quality

Experiencing cultural heritage is one of the main reasons why people travel [36]. Due to their aesthetic and historical features, cultural heritage sites are often used as stages for people to gather and create exciting and unforgettable experiences [37]. In this context, Pine and Gilmore’s experience economy model is widely applied to the analysis of tourist experiences in cultural heritage museums [38]. The experience economy is divided into four sub-dimensions: entertainment, aesthetics, education, and escapism. The study suggests that today’s museums offer not only traditional learning and educational experiences but also a mix of entertainment, enjoyment, social interaction, and escapism [39,40]. On this basis, an increasing number of empirical studies are applying the experience economy framework to tourist experiences in historical districts, verifying the practicality and empirical operability of these concepts.

In addition, Lee and Smith proposed that heritage tourism experiences include five dimensions based on the characteristics of historical sites and museums: entertainment, cultural identity exploration, education, relationship development, and escapism [41]. Kempiak et al. proposed that the main motivation for visitors to explore archaeological sites is entertainment, and the environmental atmosphere is the most influential factor during the visit [42]. Alexiou indicated that educational experiences (such as participating in festival activities) are highly engaging activities, leading to more active participation from tourists [43]. Xu et al. emphasized the importance of cultural participation in creating experiences, noting that heritage tourism must cater to tourists’ preferences in order to achieve a better experience [44].

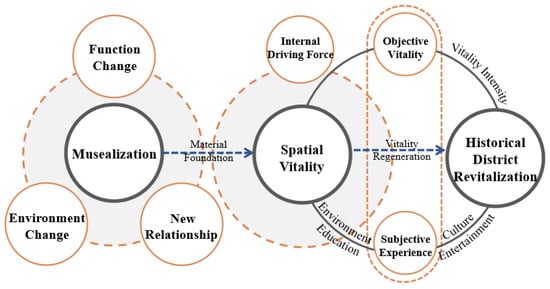

Based on the previous research mentioned above, this study constructs an “objective vitality–experience quality” model that integrates museumization, space vitality, and experience quality. In this model, museumization is regarded as a basic and core theoretical perspective throughout the whole research process. The space vitality is regarded as the representation and internal driving force of the musealization of the historical district. Therefore, from the perspectives of objective vitality and subjective experience, this study deeply explores the characteristics of spatial vitality in the Historic Center of Macau during daily and festival periods and reveals the underlying mechanisms of spatial vitality. The purpose of this study is to promote space vitality through the protection of the museumization of the historic district and to provide a new path for the sustainable development of the historic district (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Area

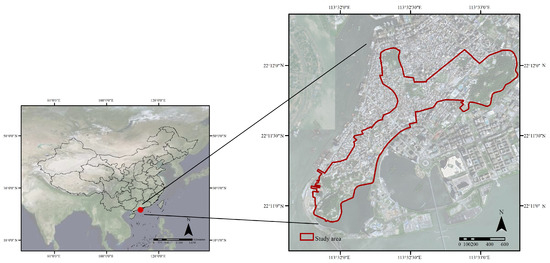

The study area for this research was the Historic Center of Macau. The Historic Center of Macau is a historical district centered around the old town, consisting of twenty-two buildings and eight adjacent squares, all located in the Macau Peninsula. In 2005, the Historic Center of Macau was inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. It is the oldest, largest, best-preserved, and most concentrated architectural ensemble of Eastern and Western styles in China. It preserves a glorious history of over 400 years of cultural exchange between China and the West (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Study area.

3.2. Research Framework

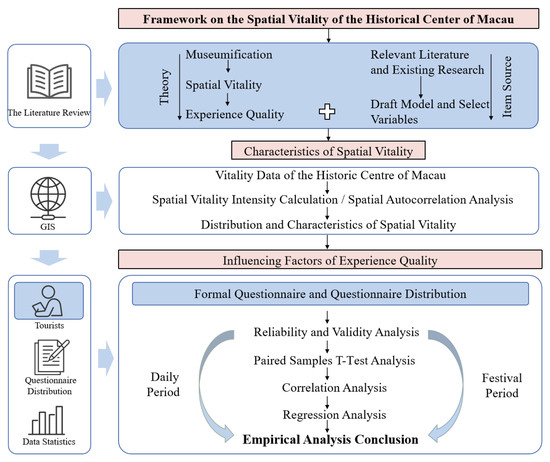

This paper discusses the influencing factors of the spatial vitality of musealization in a historical district. It is based on the theories of musealization and space vitality and combines objective and subjective evaluation methods. The research procedure was as follows (Figure 3):

Figure 3.

Research flowchart.

- (1)

- Musealization Perspective: This study applies a musealization perspective to the analysis of spatial vitality. Based on the theories of musealization, spatial vitality, and experiential quality, it extracts a theoretical framework from the relevant literature and existing research to construct an “objective vitality–experience quality” model.

- (2)

- Objective Evaluation: From an objective perspective, this study compares the spatial vitality intensity of the historical district during daily periods and festive events using a vitality intensity model. This analysis aims to examine the characteristics of spatial vitality intensity and its distribution in the historical district.

- (3)

- Subjective Evaluation: A subjective evaluation method is used to further explore the influencing factors of the spatial vitality of the historical district. By referencing the relevant literature and existing research, this paper evaluates tourists’ experience quality and then analyzes their subjective perception of spatial vitality.

3.3. Objective Analysis: Evaluate the Spatial Vitality of the Historical District

3.3.1. Vitality Data of the Historic Center of Macau

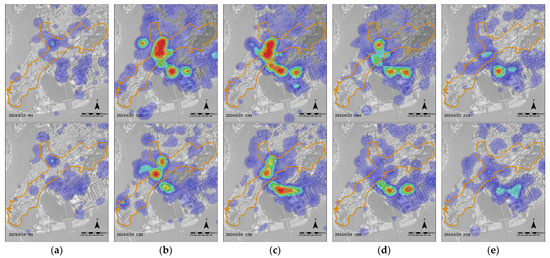

From the perspective of musealization, this study analyzed the spatial vitality of the Historic Center of Macau by comparing the differences in crowd activities between the festival and the daily periods (Figure 4). For this purpose, Baidu heatmap data were collected during a festive period (23 June 2024) and a daily period (24 June 2024). The Baidu heatmap is based on the location information collected from users when they use Baidu products such as Baidu Maps, Baidu Search, and Baidu Music [45]. The Baidu heatmap can be used to calculate the flow of people at different times and across different regions.

Figure 4.

Current situation during festival period and daily period: (a) festival period (23 June 2024); (b) daily period (24 June 2024).

In terms of data collection, data were collected from 9 am to 9 pm during the festival period (23 June 2024) and the daily period (24 June 2024), with data collected every hour, resulting in a total of 26 time points. Each recorded point contains four attributes: longitude, latitude, time, and heat. The experimental date chosen for this study avoids the interference of unexpected factors such as extreme weather. These dates are considered suitable for outdoor activities and are representative of typical conditions (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Baidu heatmap of festival and daily periods: (a) 09:00; (b) 12:00; (c) 15:00; (d) 18:00; (e) 21:00.

The date 23 June 2024 marks the celebration of the Nezha Festival in Macau. The “Na Tcha customs and beliefs” in Macau were inscribed in the fourth batch of the National Representative List of Intangible Cultural Heritage in 2014 and included in the Intangible Cultural Heritage List of Macau in 2017. This festival has a history of over 300 years. During the Feast of Na Tcha every year, various activities are held, including building altars for worship, parades, carrying deities on processions, and lion dance performances. These vibrant events attract both Macau residents and tourists to participate and interact with the space [46,47]. As one of the most representative and influential festive events in Macau, the data collected can effectively reflect the spatial vitality of the historical district during the festival period. Therefore, the data are representative.

In addition, a scientific definition of the research scale is essential for rigorously analyzing the spatial vitality of a historical district. This study selected the boundary of the Historic Center of Macau as the study area and defined the blocks enclosed by streets within the district as the basic research units. The datasets used in this study mainly include basic geographic data and open-source data obtained from the Internet (Table 1). This study used GIS to process relevant data and ultimately established 210 research units, providing a spatial foundation for subsequent analysis.

Table 1.

Data types and sources.

3.3.2. Spatial Vitality Intensity Calculation

This study utilized ArcGIS 10.8 software and applied the vitality intensity model to analyze the spatial distribution characteristics of the vitality intensity of the Historic Center of Macau. This model uses blocks as units and can comprehensively calculate the vitality intensity values of the Historic Center of Macau during both daily and festival periods. The calculation formula is as follows:

where represents the vitality intensity value of the block; denotes different time points and assigns 1 to ; is the vitality value obtained by a certain block unit at time .

Additionally, this study used the natural breaks method to divide the vitality of blocks into six levels: high heat, sub-heat, relatively hot, general, relatively cold, and extremely cold. This classification helps to better understand the distribution characteristics and changing trends in block vitality.

3.3.3. Spatial Autocorrelation

Spatial autocorrelation was used to describe the overall distribution of a phenomenon and determine whether it has clustering in space [48]. This paper used Moran’s I test to examine the spatial autocorrelation of the vitality of the Historic Center of Macau. We focused on the spatial agglomeration characteristics or dispersion trends in spatial vitality during the festival period and daily period. Its specific form is as follows:

where xi and xj represent the values at the i-th and j-th spatial units, respectively; the element wij within the spatial weight matrix W signifies the topological connection between these spatial units. The summation of all elements in the spatial weight matrix W, denoted as S0, quantifies the similarity of attribute values among spatially adjacent or neighboring regional units.

Moran’s I index is commonly regarded as a measure of spatial autocorrelation and typically ranges from −1 to 1. A Moran’s I value exceeding 0 implies significant positive spatial autocorrelation, suggesting that neighboring spatial units tend to exhibit similar data attributes, leading to clustering in areas with either high or low attribute values. Conversely, a Moran’s I value below 0 indicates a significant negative spatial autocorrelation, where adjacent spatial units display dissimilar attributes, resulting in a spatial distribution characterized by alternating high and low values. When Moran’s I index equals 0, it signifies the absence of spatial autocorrelation, indicating that the spatial distribution of data is random and irregular.

3.4. Subjective Analysis: Visitor Experience Quality Questionnaire

3.4.1. Evaluation Index Selection

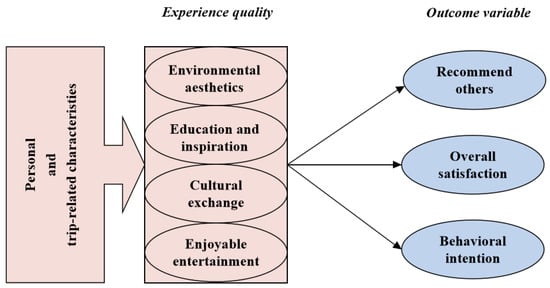

From the perspective of experiential quality, this study adopts Pine and Gilmore’s model. Pine and Gilmore’s model is widely used to measure the tourist experience while visiting historic sites and museums [49]. Pine and Gilmore’s experience economy model was chosen because it offers a comprehensive framework for evaluating the multidimensional aspects of visitors’ experiences, particularly in the context of cultural heritage and historical districts. Based on a comprehensive review of the relevant literature and the objectives of this research, this study constructed a historic district experience quality model. The model includes four main dimensions: environmental aesthetics, education and inspiration, cultural exchange, and enjoyable entertainment (Figure 6). In order to ensure the scientific design of the questionnaire, the final design of the questionnaire was reviewed and approved by two professors in the field.

Figure 6.

Model construction.

3.4.2. Questionnaire Design

This study employs the subjective evaluation method to explore the specific factors influencing the spatial vitality of historical districts. The questionnaire (Supplementary Materials) consists of six parts. The first section focuses on travel motivation and consists of four items adapted from Alrawadieh [50]. This section aims to identify the intrinsic factors influencing tourists’ participation in historical district tourism by assessing their motivations. The second section is an evaluation of the perceived quality of tourist experiences in the historical district, covering four dimensions (environmental aesthetics, education and inspiration, cultural exchange, and enjoyable entertainment), with a total of nineteen items. The questions were adapted from existing research scales on the experience economy [51] (Table 2). These dimensions are essential for a comprehensive assessment of tourists’ perceptions and experiences of a historical district in the context of musealization. The third section evaluates satisfaction. Spatial vitality refers to a space’s ability to meet people’s activity needs, emphasizing users’ subjective experiences and feelings toward a specific environment [52]. This study uses “satisfaction” as a criterion for evaluating the vitality of the Historic Center of Macau, consisting of three items [53,54]. The concept of satisfaction was first proposed by Cardozo in 1965 and is generally regarded as individuals’ subjective evaluation of the purchasing experience [55]. In recent years, satisfaction research has gained extensive attention in the field of heritage tourism evaluation [56,57]. The fourth section examines the demographic characteristics of respondents, including gender, age, educational background, and occupation. This study uses a five-point Likert scale for measurement (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree).

Table 2.

Quality experience questionnaire for historic district.

3.4.3. Questionnaire Distribution

To explore the difference in tourists’ experience perception between the daily and the festival periods in the Historic Center of Macau, this study was divided into two questionnaires. This study invited the same group of tourists to complete both questionnaires simultaneously, ensuring the consistency of respondents’ perceptions.

The questionnaire was collected through the “Wenjuanxing” (Questionnaire Star) platform. The questionnaire survey was conducted using a combination of online and offline methods. Offline questionnaires were randomly distributed by researchers to tourists in the Historic Center of Macau. Tourists were invited to complete the online questionnaires by scanning a QR code to enter the Wenjuanxing platform. This method effectively ensured that all respondents were genuine visitors to the historical district. This approach aimed to directly obtain first-hand data on tourists’ perceived experiences and feelings. For the online survey, researchers invited tourists with experience visiting the Historic Center of Macau through friends or social circles. The questionnaire distribution period was from 12 January 2025 to 30 January 2025. A total of 470 questionnaires were distributed, and 448 valid responses were collected, resulting in an effective response rate of 95.3%. This sample size met the requirement of being five to ten times the number of scale questions, providing a sufficient and reliable sample basis for the research.

3.4.4. Data Analysis

The paired sample t-test was employed to compare tourists’ perceptions of spatial vitality between the daily and festival periods, leveraging the same group of respondents to control for individual differences.

Before conducting the paired sample t-test, the normality of the data distribution was assessed following the recommendations of West [64]. When the absolute value of kurtosis is less than 7 and the absolute value of skewness is less than 2, it can be considered that the data approximately follow the characteristics of a normal distribution. The normality test indicated that the data exhibited good characteristics of normality, thereby providing a reliable foundation for the paired sample t-test.

The paired sample t-test was conducted using the following formula:

where represents the meaning of the differences between paired observations; is the standard deviation of the differences; and is the number of pairs.

In addition to the paired samples t-test, this study also employed multiple linear regression analysis to examine the relationship between various elements of musealization. The model is expressed as follows:

where represents the dependent variable; is the intercept; β1, β2, …, βk are the regression coefficients associated with the independent variables , , …; and ϵ denotes the error term. This approach allows for a comprehensive understanding of how different factors collectively influence the outcome variable.

4. Results

4.1. Spatial Vitality Analysis of the Historic Center of Macau

4.1.1. Distribution and Characteristics of Spatial Vitality

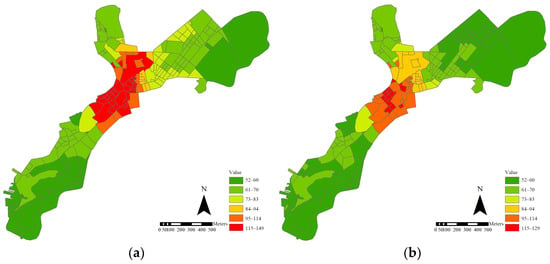

As shown in Figure 7, there are obvious differences in the vitality of the Historic Center of Macau. From the two images, it is visually apparent that the central blocks of the Historic Center of Macau show higher spatial vitality, represented by red and orange on the vitality map. The northeastern and southern districts show lower spatial vitality, depicted as green on the vitality intensity map. This suggests relatively low activity and pedestrian traffic in these areas.

Figure 7.

Vitality intensity map of historic district: (a) vitality intensity map for festival period; (b) vitality intensity map for daily period.

By comparing the average daily vitality intensity of the blocks during festive and daily periods, this study found that during the festive period, the minimum vitality intensity of the blocks is 52.38 and the maximum is 149.46, while during the daily period, the minimum is 52.00 and the maximum is 128.52. Therefore, it can be concluded that the vitality intensity of the blocks during the festival period is significantly higher than during the daily period (Figure 7).

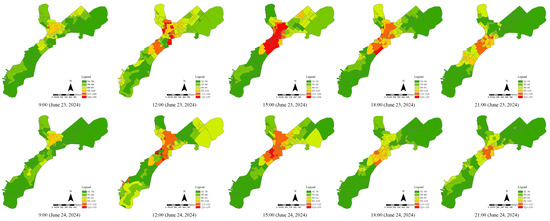

Figure 8 illustrates the diurnal variation in spatial vitality within the historic district, comparing a festive period (23 June) with a daily period (24 June) across five time intervals (9H, 12H, 15H, 18H, and 21H). The results indicate that the vitality during the festive period is higher than that during the daily period across various temporal dimensions. To further ensure the objectivity of the data, the research team conducted field research and observations. During the festival, the flow of people is mainly concentrated in the Na Tcha Temple area around 11 am. As the parade goes on, the flow of people gradually shifts to the Camoes Garden and effectively stimulates the vitality of the surrounding streets. The on-site investigation results are consistent with the Baidu heatmap results.

Figure 8.

Comparison of spatial vitality intensity between festival and daily periods.

4.1.2. Spatial Autocorrelation Analysis

This study utilized ArcGIS 10.8 software for the spatial autocorrelation analysis (Table 3). The analysis revealed that Moran’s I values were consistently positive (>0), with a significance level of 0.00 (<0.05). This indicates that the observed spatial patterns are highly unlikely to have arisen from random processes and have successfully passed the 5% significance test. Consequently, the null hypothesis can be rejected. The results demonstrate that the spatial vitality distribution of the Historic Center of Macau exhibits a significant positive spatial autocorrelation, characterized by distinct “high–high” (HH) and “low–low” (LL) agglomeration patterns. Notably, Moran’s Index value was higher on June 24th, suggesting a stronger spatial clustering effect on this date.

Table 3.

Moran’s I index of spatial vitality in the Historic Center of Macau.

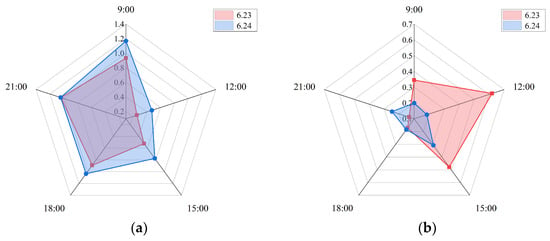

4.1.3. Characteristics of Spatial Vitality in the Time Dimension

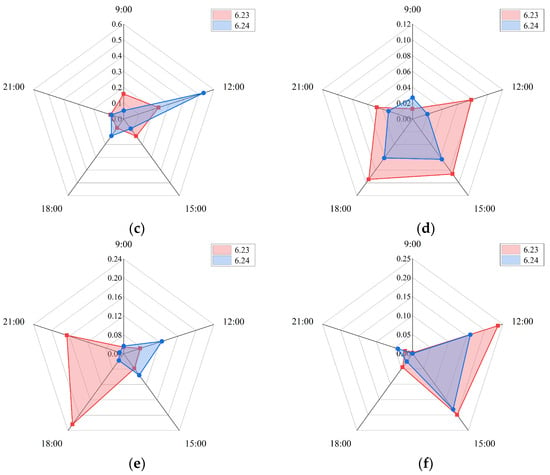

This study used a radar chart in the Origin 2021 software to visualize changes in the vitality intensity of the historical district. Figure 9 shows that the spatial extent of each level of vitality changed over time. In the radar chart of the high-heat area, the historical district reached 0.24 km2 at 12:00 during the festival period (23 June). In the radar chart of the sub-heat area, the area during the festival period (23 June) reached 0.22 km2 at 16:00 and 0.17 km2 at 21:00. The results indicate that the vitality of the historical district during the festival period is higher than during the daily period in the high-heat and sub-heat categories (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Comparison of changes in areas for vitality and heat intensity: (a) extreme cold area; (b) relatively cold area; (c) general area; (d) relatively hot area; (e) sub-heat area; (f) high-heat area.

The results show that festival activities have a significant temporal and spatial impact on the vitality distribution of the Historic Center of Macau, with the effect on the vitality of high-heat and sub-heat areas being particularly prominent. This reflects that festival activities can effectively attract people and enhance the vitality of space. Therefore, there are differences in the spatial vitality of the historical district from the perspective of musealization.

4.2. Questionnaire Results and Analysis

4.2.1. Descriptive Analyses

In terms of gender distribution, 45.5% of the respondents were male and 54.5% were female. A total of 69.6% of the respondents were tourists, including mainland tourists and overseas tourists. In addition, students accounted for 18.3% of these tourists (mainly for short-term travel). This further illustrates the attraction of Macau as an international city and highlights its unique position as a World Center of Tourism and Leisure. The age distribution shows that many respondents (79.0%) were between 19 and 40 years old. As for educational background, 90.6% of the respondents held at least a college or undergraduate degree, indicating a generally high level of education among the participants. In terms of the purpose of visits, leisure travel was predominant, accounting for 50.4%, followed by festival activities (10.7%) and educational tourism (9.8%), reflecting a dual demand for leisure and cultural experiences. The primary communication channels were social media (37.5%) and recommendations from friends (27.7%) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Sample characteristics of 224 respondents.

4.2.2. Paired Samples t-Test Analysis

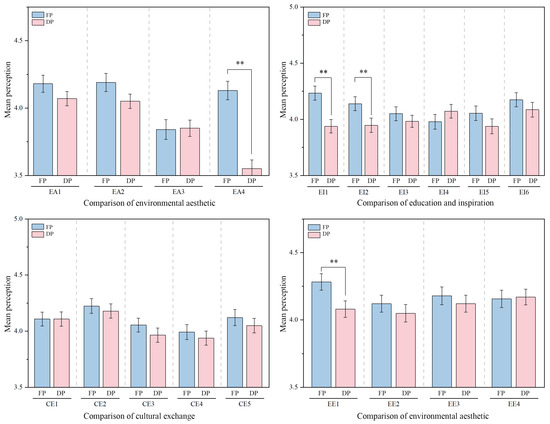

This study employed a paired sample t-test to compare tourists’ perceptions of environmental aesthetics, education and inspiration, cultural exchange, and entertainment enjoyment during the festival and daily periods (Table 5).

Table 5.

Paired samples t-test.

The paired sample t-test revealed significant differences in the dimensions of environmental aesthetics (t = −4.874, p < 0.01) and entertainment enjoyment (t = −2.298, p < 0.05) between the festival and the daily periods. In the dimension of environmental aesthetics, the festival period had a higher mean score (M = 4.26) compared to the daily period (M = 4.00). Similarly, in the dimension of enjoyable entertainment, the festival period scored higher (M = 4.18) than the daily period (M = 4.10). These results show that the festival period was significantly higher in environmental aesthetics.

It is worth noting that although there was no significant difference in the overall level of the education and enlightenment dimension (p = 0.151), there were significant differences among the elements. During the festival period, the artistic attraction element scored (M = 4.23) significantly higher compared to the daily period (M = 3.94). This indicates that festival activities significantly enhance visitors’ artistic immersion through performing arts activities. In the edutainment elements, the mean value during the festival period was 4.14, while during the daily period it was 3.95, with a mean difference of -0.192 (t = −2.742, p = 0.007). This difference may be attributed to the integration of both entertainment and educational activities in festival events. Such activities enhance tourists’ participation and the depth of their experiences (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Paired samples t-test results. (** p < 0.01).

The paired sample t-test revealed that there were differences in tourists’ perceptions of the Historic Center of Macau between the daily and festival periods when viewed from the perspective of musealization.

4.2.3. Correlation Analysis

This study used Pearson’s correlation coefficient to further analyze the quality of tourists’ experience in the Historic Center of Macau during the festival (Table 6).

Table 6.

Correlation analysis.

From Table 6, the following conclusions can be drawn:

- (1)

- The 19 experiential elements show significant correlation with the satisfaction dimension at the 0.01 level, and the correlation coefficients are all positive, indicating a strong positive correlation between these elements and satisfaction. Among them, the correlation coefficients between 18 experience quality evaluation indicators and satisfaction are all between 0.3 and 0.7, confirming the correlation effect of experience elements on vitality perception.

- (2)

- In the evaluation dimensions of experience quality, enjoyable entertainment and cultural exchange have a high correlation with the vitality of the space. In particular, the unique experience (0.604) in the dimension of entertainment enjoyment and multicultural exploration (0.524) in the dimension of cultural exchange have the highest correlation with spatial vitality.

- (3)

- Among the specific influencing factors of experience quality evaluation, the correlation coefficients for unique experience (0.604), pleasant experience (0.542), enjoyable experience (0.542), and artistic attraction (0.536) are relatively high. Therefore, these indicators have a significant positive correlation with spatial vitality.

4.2.4. Multiple Linear Regression Analysis

To further examine the correlation between various elements of tourist experience quality and spatial vitality, this study employs multiple linear regression analysis for validation. The dependent variable is defined as “satisfaction”.

By exploring the relationship between various elements of tourist experience quality in the historical district during the festival period, the results of the multiple linear regression model (Table 7) and the data table (Table 8) were obtained.

Table 7.

Results of the multiple regression model for the festival period.

Table 8.

Regression analysis of the vitality of historical district during the festival period.

The following can be observed from examining Table 6:

- (1)

- The value of F = 15.964 (p = 0.000 < 0.01) demonstrates that the model is statistically significant at the 0.01 significance level. Additionally, the F-test confirms the presence of a linear relationship between the model and the dependent variable, thereby validating the model’s effectiveness.

- (2)

- The adjusted R2 value of the regression model is 0.560, indicating a good model fit. This suggests that 56% of the variation in spatial vitality can be explained by 19 influencing factors. Specifically, 56% of the spatial vitality in Macau’s historic district is attributed to nineteen influencing factors across four dimensions: environmental aesthetics, education and inspiration, cultural exchange, and entertainment enjoyment.

- (3)

- The Durbin–Watson (D-W) value is 1.985, which is close to 2, indicating that the model does not exhibit significant autocorrelation and that the data are independent, thus meeting the fundamental assumptions of regression analysis.

According to the significance and correlation coefficient of the independent variable and the dependent variable, the regression model was obtained, outlined as follows:

Y = 0.651 + 0.078 ∗ X1 + 0.167 ∗ X2 + 0.152 ∗ X3 − 0.106 ∗ X4 − 0.162 ∗ X5 + 0.115 ∗ X6 + 0.106 ∗ X7 + 0.161 ∗ X8 + 0.200 ∗ X9

- (1)

- In the dimension of environmental aesthetics, spatial elements (p = 0.048 < 0.05, b = 0.078) were positively correlated with satisfaction at a 0.05 significance level.

- (2)

- In the dimension of education and inspiration, the four elements of artistic attraction—educational entertainment, inspiring experience, and heritage interaction—significantly influence the visitor experience quality. Specifically, artistic attraction (p = 0.001 < 0.01, B = 0.167) and educational entertainment (p = 0.003 < 0.01, B = 0.152) are positively correlated with vitality at the 0.01 significance level.

- (3)

- However, the correlation coefficients for an inspiring experience (p = 0.042 < 0.05, B = −0.106) and heritage interaction (p = 0.001 < 0.05, B = −0.162) are both less than 0. Therefore, these two factors are negatively correlated with satisfaction and have a relatively small impact.

- (4)

- In the dimension of enjoyable entertainment, an interesting experience (p = 0.033 < 0.05, B = 0.106), a pleasant experience (p = 0.002 < 0.05, B = 0.161), and an enjoyable experience (p = 0.000 < 0.01, B = 0.200) are significantly positively correlated with satisfaction.

The results show that during the festival period, various elements such as environmental aesthetics, education and inspiration, cultural exchange, and entertainment enjoyment have a positive impact on the vitality of space.

5. Discussion

5.1. Distribution Characteristics of Spatial Vitality in the Historical District Under Musealization

The research shows that the spatial distribution of vitality in the Historic Center of Macau is uneven, which is consistent with existing research [65]. Further analysis reveals that the spatial vitality of the Historic Center of Macau is concentrated in the central area, spreading to the surrounding regions. The areas with higher vitality are primarily concentrated in the central blocks of the historical district, especially the tourist areas, commercial areas, and tourist–commercial complexes south of the Avenida de Almeida Ribeiro. These areas are represented in red and orange on the spatial vitality map, indicating a high level of activity. This high vitality mainly relies on the inherent architectural heritage and cultural atmosphere of the region, exemplified by iconic heritage sites such as the Ruins of St. Paul’s and Senado Square.

Based on the theory of musealization, this study further proposes that festive activities significantly enhance the spatial vitality of the historic district. Utilizing a vitality intensity model, this study compares the differences in spatial vitality of the historic district during festive and daily periods from the perspectives of vitality intensity and vitality area. This research finds that intangible cultural heritage festivals, such as the Nezha Festival, successfully guide crowds from the core areas of historical districts to surrounding areas through dynamic exhibition forms such as parades and performances.

5.2. The Relationship Between Experience Quality and Spatial Vitality

Research has found that the quality of experience positively impacts the spatial vitality of the historical district. The results of this study support the conclusions of Jin et al. and Xia et al. that higher evaluations of spatial experience quality by tourists have a significant positive impact on spatial vitality [66,67]. In addition, this study further demonstrates the importance of educational and entertainment experiences in a historical district, especially festival events that play an important role in the perception of educational and entertainment experiences.

In the dimension of education and inspiration, artistic attraction (p = 0.001 < 0.01, B = 0.167) demonstrates that engagement through art can quickly stimulate visitors’ interest. The Baidu heatmap data also reflect this phenomenon, indicating that areas with performances have higher instantaneous foot traffic. This shows that the performing arts are a form of cultural transmission and have a strong appeal. Performing arts can promote the audience’s positive interaction and perception of historical and cultural space, thus improving the vitality of a space. Another core element in the education and inspiration dimension is the interest in educational entertainment (p = 0.003 < 0.01, B = 0.152), suggesting that organizing entertainment and education-related activities can further stimulate tourists’ interest; this aligns with the findings of Pallud et al. [68]. When tourists visit historical districts, they can gain a new type of experience, namely edutainment, allowing them to engage both passively and actively. The findings further reveal that festival activities exhibit the characteristics of “exhibition is experience”. This form breaks the “separation of audience and performance” model in traditional museums and achieves the “integration of audience and performance”. Through immersive experience, it arouses visitors’ emotions and makes them participate more actively, further enhancing the vitality of the historical district.

Therefore, the educational entertainment aspect of the musealization of historical districts is not only a modernization transformation of cultural heritage protection and display but also a deepening and expansion of cultural communication and educational functions, thereby achieving sustainable cultural development.

6. Conclusions

This study uses the Historic Center of Macau as the research object and uses museumization as a strategy to respond to the development of cultural tourism in the historical district. This study establishes an “objective vitality–experience quality” model to explore the influencing factors in the spatial vitality of museumization in the Historic Center of Macau from both objective and subjective perspectives. This study aims to activate the vitality of the historical district and promote the sustainable development of Macau’s tourism industry.

(1) Musealization as a method has evolved beyond the traditional scope of research and works at a broader social level through curation. It has played an important role in the revitalization of the historical district. (2) The results of spatial vitality analysis show that there is a significant difference in spatial vitality between the daily period and the festival period. Festival activities strengthen the perception of the “center–edge” spatial structure of the historical district, indicating that festival cultural activities can attract tourists and enhance the vitality of the space, achieving more diverse and balanced urban development. (3) The results of the subjective evaluation further indicate that the factors influencing spatial vitality are different during daily periods and festival periods. Education and inspiration played a significant role in special exhibitions, with artistic attraction (p = 0.001 < 0.01, b = 0.167) and educational entertainment (p = 0.003 < 0.01, b = 0.152) having a significant impact on visitors’ engagement and depth of experience. This innovative perspective discusses how to realize the educational and communication functions of cultural heritage in contemporary society and then expands the connotation and value of musealization protection.

However, this study also has some limitations. Firstly, it primarily focuses on Na Tcha parade festival activities and does not comprehensively cover other types of cultural activities (such as artistic exhibitions, traditional festival cultural activities, etc.). Future research could consider a more detailed classification and discussion of various types of cultural exhibition activities. Secondly, this study did not distinguish the difference between weekdays and weekends, which may have an impact on the accurate determination of spatial vitality changes. Therefore, future research should supplement and distinguish data on weekdays and weekends to enhance the objectivity and accuracy of data. In addition to festival activities, the construction of landmark buildings and cultural facilities also has an impact on the spatial vitality of the historical district. For example, the cultural, creative, and recreational tourism complex at the Macau Fisherman’s Wharf and cultural facilities such as street art installations can effectively attract tourists and enhance the vitality of the space. This can not only effectively solve the lack of space vitality in some areas but also further promote the innovation and comprehensive development of museumization in practical application and provide reference and enlightenment for the cultural regeneration of other historical districts. This part of the content needs to be further complemented and improved in future research.

To sum up, this study investigated the factors influencing the spatial vitality of the Historic Center of Macau from the perspective of museumization. Future research can be further analyzed based on different time dimensions, types of festival activities, and the distribution of cultural facilities in order to verify research conclusions and expand research depth, providing more innovative solutions for the development of cultural tourism in historical districts.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/buildings15142512/s1.

Author Contributions

Methodology, X.L. and J.Z. (Junyi Zhao); software, J.Z. (Junyi Zhao); validation, X.L.; writing—original draft, X.L.; writing—review and editing, P.W. and J.Z. (Junling Zhou). supervision, P.W.; project administration, P.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

All subjects provided informed consent for inclusion before they participated in this study. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Innovation and Design, City University of Macau (Ref: 202506270939).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in this article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Jia, M.; Feng, J.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, C. Visual Analysis of Social Media Data on Experiences at a World Heritage Tourist Destination: Historic Centre of Macau. Buildings 2024, 14, 2188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.K.P.; Lo, W.S.S.; Eddy-U., M.E. Perceived Constraints and Negotiation Strategies by Elderly Tourists When Visiting Heritage Sites. Leis. Stud. 2022, 41, 703–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Feng, J.; Wu, R.; Jia, M. Tourists’ Perception of Macau’s City Image: Based on the Analysis of User-Generated Content (UGC) Text Data. Buildings 2023, 13, 1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aykaç, P. Absent Presents: Musealisation of the Historic Town of Hasankeyf as a Manifestation of ‘Absent Heritage’. J. Archit. Conserv. 2023, 29, 214–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabri, R.; AlGhareeb, D.; Alkhaja, N. Museums and Museumification in Post-Conflict Contexts: Revisiting the Shaping of Architectural Reconstruction Strategies. Hist. Environ. Policy Pract. 2023, 14, 236–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.; Graburn, N. Curating Pasts: Musealization and Tourism in Chinese Cities. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2024, 10, 509–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Long, Y.; Zhang, L.; Yang, J.; Dong, W. Quantitative Measurement of Urban Spatial Vitality by Integrating Physical Built Environment and Subjective Perception Dimensions. Environ. Plan. B Urban Anal. City Sci. 2025, 52, 131–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Song, J.W.; Teng, S.J.; Guo, X.Q. Typology and Perceptual Quantification of Interface Morphology in Pedestrian Commercial Streets. Planners 2020, 36, 87–92. [Google Scholar]

- Nelle, A.B. Mapping Museality in World Heritage Towns: A Tool to Analyse Conflicts between the Presentation and Utilisation of Heritage. Pract. Asp. Cult. Herit. 2006, 1, 85–94. [Google Scholar]

- Stransky, Z.Z. Museology as a Science. Museologia 1980, 15, 33–40. [Google Scholar]

- Nelle, A.B. Museality in the Urban Context: An Investigation of Museality and Musealisation Processes in Three Spanish-Colonial World Heritage Towns. Urban Des. Int. 2009, 14, 152–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, D. Newly Constructed Ancient Towns in China: Creating ‘Heritage’ in Theme Parks. J. Tour. Cult. Change 2023, 21, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronchini, C. Cultural Paradigm Inertia and Urban Tourism. In The Future of Tourism: Innovation and Sustainability; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 179–194. [Google Scholar]

- Aykaç, P. Musealization as an Urban Process: The Transformation of the Sultanahmet District in Istanbul’s Historic Peninsula. J. Urban Hist. 2019, 45, 1246–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aykaç, P. Contesting the Byzantine Past: Four Hagia Sophias as Ideological Battlegrounds of Architectural Conservation in Turkey. Herit. Soc. 2018, 11, 151–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grodach, C.; Loukaitou-Sideris, A. Cultural Development Strategies and Urban Revitalization: A Survey of US Cities. Int. J. Cult. Policy 2007, 13, 349–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franklin, A. Journeys to the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao: Towards a Revised Bilbao Effect. Ann. Tour. Res. 2016, 59, 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haley, A.J.; Snaith, T.; Miller, G. The Social Impacts of Tourism a Case Study of Bath, UK. Ann. Tour. Res. 2005, 32, 647–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirina, A. Processes of museumification of historical cultural heritage: In the interpretation of authenticity, intangible and tangible heritage. IMRAS 2024, 7, 85–90. [Google Scholar]

- Kassem, A.; Awad, J.; Eldanaf, T. From Museumification to Performativization. A Performative Approach to Heritage Reuse. Cases from the United Arab Emirates. Future Cities Environ. 2024, 10, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, B.S.; Busenhart, I. Special Exhibitions and Festivals: Culture’s Booming Path to Glory. Contrib. Econ. Anal. 1996, 237, 275–302. [Google Scholar]

- Pourzakarya, M.; Bahramjerdi, S.F.N. Towards Developing a Cultural and Creative Quarter: Culture-Led Regeneration of the Historical District of Rasht Great Bazaar, Iran. Land Use Policy 2019, 89, 104218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, J. Dark Age Ahead: Author of the Death and Life of Great American Cities; Vintage Canada: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, K. The Image of the City; The MIT Press: Cambridge, UK, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, D.F. Urban Morphology and Vitality Theory; Southeast University Press: Cape Girardeau, MO, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Ta, N.; Zeng, Y.; Zhu, Q.; Wu, J. Analysis of the Relationship between Built Environment and Urban Vitality in Central Shanghai Based on Big Data. Sci. Geogr. Sin 2020, 40, 60–68. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, B.; Sun, J.; Wang, Z.; Jin, S. Influencing Factors of Street Vitality in Historic Districts Based on Multisource Data: Evidence from China. ISPRS Int. J. Geo Inf. 2024, 13, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Li, J.; Yu, F.; He, H.; Zhen, F. Space, Function, and Vitality in Historic Areas: The Tourismification Process and Spatial Order of Shichahai in Beijing. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2018, 20, 335–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Ye, R.; Hong, X.; Tao, Y.; Li, Z. What Factors Revitalize the Street Vitality of Old Cities? A Case Study in Nanjing, China. ISPRS Int. J. Geo Inf. 2024, 13, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Jiang, X.; Tan, L.; Chen, C.; Yang, S.; You, W. Analysis of Spatial Vitality Characteristics and Influencing Factors of Old Neighborhoods: A Case Study of Ya’an Xicheng Neighborhood. Buildings 2024, 14, 3348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Luo, L.; Shen, X.; Xu, Y. Influence of Built Environment and User Experience on the Waterfront Vitality of Historical Urban Areas: A Case Study of the Qinhuai River in Nanjing, China. Front. Archit. Res. 2023, 12, 820–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Lai, S.-Q.; Liu, C.; Jiang, L. What Influenced the Vitality of the Waterfront Open Space? A Case Study of Huangpu River in Shanghai, China. Cities 2021, 114, 103197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Han, Y. Vitality Evaluation of Historical and Cultural Districts Based on the Values Dimension: Districts in Beijing City, China. Herit. Sci. 2022, 10, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, T.; Ye, Y.; Zhuang, Y.; Lin, Q.; Yan, M.; Zhang, L.; Zhu, L. A Study of the Changing Characteristics and Influencing Factors of Holiday Visitor Vitality in Urban Parks: The Case of Fuzhou, China. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0311546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Li, X.; Guo, Y. Research on the Influencing Factors of Spatial Vitality of Night Parks Based on AHP–Entropy Weights. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timothy, D.J.; Boyd, S.W. Heritage Tourism in the 21st Century: Valued Traditions and New Perspectives. J. Herit. Tour. 2006, 1, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorentzen, A.; Larsen, K.T.; Schrøder, L. Spatial Dynamics in the Experience Economy; Routledge: London, UK, 2015; pp. 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Radder, L.; Han, X. An Examination of the Museum Experience Based on Pine and Gilmore’s Experience Economy Realms. J. Appl. Bus. Res. 2015, 31, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, A.; Ma, D.; Pan, Y.; Qian, H. Enhancing Museum Visiting Experience: Investigating the Relationships between Augmented Reality Quality, Immersion, and TAM Using PLS-SEM. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2024, 40, 4521–4532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J.-H.; Lee, K.-H. The Physical Environment in Museums and Its Effects on Visitors’ Satisfaction. Build. Environ. 2006, 41, 963–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.M.; Smith, S.L. A Visitor Experience Scale: Historic Sites and Museums. J. China Tour. Res. 2015, 11, 255–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kempiak, J.; Hollywood, L.; Bolan, P.; McMahon-Beattie, U. The Heritage Tourist: An Understanding of the Visitor Experience at Heritage Attractions. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2017, 23, 375–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexiou, M.-V. Experience Economy and Co-Creation in a Cultural Heritage Festival: Consumers’ Views. J. Herit. Tour. 2020, 15, 200–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Zhang, J.; Nie, Z. Role of Cultural Tendency and Involvement in Heritage Tourism Experience: Developing a Cultural Tourism Tendency–Involvement–Experience (TIE) Model. Land 2022, 11, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Zhang, X. Towards More Reliable Measures for “Perceived Urban Diversity” Using Point of Interest (POI) and Geo-Tagged Photos. ISPRS Int. J. Geo Inf. 2025, 14, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z. Visualizing Experiencescape–from the Art of Intangible Cultural Heritage. Curr. Issues Tour. 2022, 25, 559–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; King, B.; Suntikul, W. Co-Creation of Value for Cultural Festivals: Behind the Scenes in Macau. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2020, 45, 430–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. New Approaches for Calculating Moran’s Index of Spatial Autocorrelation. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e68336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmetoglu, M.; Engen, M. Pine and Gilmore’s Concept of Experience Economy and Its Dimensions: An Empirical Examination in Tourism. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2011, 12, 237–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrawadieh, Z.; Prayag, G.; Alrawadieh, Z. A Cognitive Appraisal Perspective of Emotional Accessibility at Heritage Sites: Empirical Evidence from the UNESCO World Heritage Site of Petra. J. Herit. Tour. 2023, 18, 145–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Liu, X.; Li, Z.; Tan, Z. Multi-Experiences in the Art Performance Tourism: Integrating Experience Economy Model with Flow Theory. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2021, 38, 491–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiaohua, W. Influencing Mechanism and Evaluation of Public Space Vitality in Hangzhou Characteristic Towns. Ph.D. Thesis, Central South University of Forestry and Technology, Changsha, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- De Rojas, C.; Camarero, C. Visitors’ Experience, Mood and Satisfaction in a Heritage Context: Evidence from an Interpretation Center. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 525–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altunel, M.C.; Koçak, Ö.E. The Roles of Subjective Vitality, Involvement, Experience Quality, and Satisfaction in Tourists’ Behavioral Intentions. Eur. J. Tour. Res. 2017, 16, 233–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardozo, R.N. An Experimental Study of Customer Effort, Expectation, and Satisfaction. J. Mark. Res. 1965, 2, 244–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.T.; Liu, F.; Soutar, G.N. Experiences, Post-Trip Destination Image, Satisfaction and Loyalty: A Study in an Ecotourism Context. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2021, 19, 100547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, D.N.; Nguyen, N.A.N.; Nguyen, Q.N.T.; Tran, T.P. The Link between Travel Motivation and Satisfaction towards a Heritage Destination: The Role of Visitor Engagement, Visitor Experience and Heritage Destination Image. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 34, 100634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrest, R. Museum Atmospherics: The Role of the Exhibition Environment in the Visitor Experience. Visit. Stud. 2013, 16, 201–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirghadr, L.; Torabi Farsani, N.; Shafiei, Z.; Hekmat, M. Identification of Key Components of Visitor Education in a Museum. Mus. Manag. Curatorsh. 2018, 33, 223–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Liang, H. Factors Influencing Learning Effectiveness of Educational Travel: A Case Study in China. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 42, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Luo, J.M. An Empirical Study on Cultural Identity Measurement and Its Influence Mechanism Among Heritage Tourists. Front. Psychol. 2023, 13, 1032672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.; Lyu, C.; Li, J. Unpacking Generation Z Tourists’ Motivation for Intangible Cultural Heritage Tourism. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2024, 49, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komarac, T.; Ozretic-Dosen, D.; Skare, V. Managing Edutainment and Perceived Authenticity of Museum Visitor Experience: Insights from Qualitative Study. Mus. Manag. Curatorsh. 2020, 35, 160–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, C.; Wu, S.; Li, E.; Li, H.; Liu, X. Identification of Urban Functional Zones in Macau Peninsula Based on POI Data and Remote Information Sensors Technology for Sustainable Development. Phys. Chem. Earth Parts A/B/C 2023, 131, 103447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, A.; Ge, Y.; Zhang, S. Spatial Characteristics of Multidimensional Urban Vitality and Its Impact Mechanisms by the Built Environment. Land 2024, 13, 991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Rao, T. The Spatial Pattern and Influence Mechanism of Urban Vitality: A Case Study of Changsha, China. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 942577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallud, J. Impact of Interactive Technologies on Stimulating Learning Experiences in a Museum. Inf. Manag. 2017, 54, 465–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).